Abstract

Although structural changes of the basal ganglia are widely implicated in schizophrenia, prior findings in chronically medicated patients show that these changes relate to particular antipsychotic treatments. In unmedicated schizophrenia, local alterations in morphological parameters and their relationships with clinical measures remain unknown.

Novel surface-based anatomical modelling methods were applied to magnetic resonance imaging data to examine regional changes in the shape and volume of the caudate, the putamen and the nucleus accumbens in 21 patients (19 males/2 females; mean age=30.7±7.3) who were either antipsychotic-naïve or antipsychotic-free for at least 1 year and 21 healthy comparison subjects (19 males/2 females; mean age=31.1±8.2). Clinical relationships of striatal morphology were based on exploratory analyses.

Left and right global putamen volumes were significantly smaller in patients than controls; no significant global volume effects were observed for the caudate and the nucleus accumbens. However, surface deformation mapping results showed localized volume changes prominent bilaterally in medial/lateral anterior regions of the caudate, as well as in anterior and midposterior regions of the putamen, pronounced on the medial surface. A significant positive correlation was observed between right anterior putamen surface contractions and affective flattening, a core negative symptom of schizophrenia.

The diagnostic effects of local surface deformations mostly pronounced in the associative striatum, as well as the correlation between anterior putamen morphology and affective flattening in unmedicated schizophrenia suggest disease-specific neuroanatomical abnormalities and distinct cortical-striatal dysconnectivity patterns relevant to altered executive control, motor planning, along with abnormalities of emotional processing.

Keywords: basal ganglia, non-medicated schizophrenia, surface mapping, putamen, affective flattening

1. Introduction

Basal ganglia structures form critical nodes for multiple circuits that are implicated in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia. Involuntary movements, affective disturbances and catatonia in schizophrenia are phenotypically similar to symptoms found in basal ganglia-related disorders, such as Huntington’s disease and Parkinson’s disease, implying the possibility of basal ganglia pathology in schizophrenia. Findings of basal ganglia abnormalities in schizophrenia are mixed. Most structural magnetic resonance imaging studies (MRI) found volume increases of distinct basal ganglia structures (Breier et al., 1992; Glenthoj et al., 2007; Mamah et al., 2007), although normal (Gunduz et al., 2002) and decreased volumes (Corson et al., 1999; Glenthoj et al., 2007; Keshavan et al., 1998) were also reported. Basal ganglia enlargement has been interpreted as being due to typical antipsychotic medications (Scherk and Falkai, 2006).

The principal anatomical component of the basal ganglia is the striatum, which is differentiated into the caudate, the putamen and the nucleus accumbens. The striatum receives afferent inputs from the cortex, and sends projections back to the cortex via thalamus. Different parts of the striatum receive input from different cortical regions, which serves as the basis of the functional division of the striatum into associative (anterior), sensorimotor (posterior), and limbic (ventral) parts (Lehéricy et al., 2004), with each part being involved in specific functions, including executive control, motor planning and emotional processing (Guillin et al., 2007).

Novel computational image analysis methods have several advantages over traditional volumetric approaches. They can isolate local, as well as global, differences in brain morphology, thus providing additional and complementary information about local structural alterations meaningful in the context of functional neuroanatomy. One study using first-generation computerized approach found shape alterations indexing local decreases in the lateral regions of the right caudate in never-medicated patients compared to controls (Shihabuddin et al., 1998), whereas another study suggested local volume loss in anterior and posterior regions of the caudate and anterior-lateral regions of the putamen, even in the presence of significant global volume increases, in patients treated chronically with antipsychotics (Mamah et al., 2007). However, in unmedicated patients, the question of regional specificity of volume changes in the striatum remains to be clarified.

Furthermore, the relationship between local alterations in striatal morphology and clinical variables of unmedicated schizophrenia remains to be elucidated. Functional imaging studies using fMRI (Juckel et al., 2006; Takahashi et al., 2005), PET (Crespo-Facorro et al., 2001; Piailly et al., 2006) and SPECT (Heinz et al., 1998) methods have implicated striatal dysfunction in negative symptoms, such as affective flattening and anhedonia. With regard to structural imaging, one study in treated patients found an inverse correlation between nucleus accumbens volume and delusions (Mamah et al., 2007), whereas another showed increases in caudate and putamen volumes associated with positive symptom reduction following antipsychotic treatment (Taylor et al., 2005). However, no study that we are aware of has investigated links between structural abnormalities of the striatum and clinical manifestations in unmedicated patients with schizophrenia.

Together, based on these observations, the aim of our study was to use a region-of-interest technique and a 3-dimensional (3D) radial mapping approach to (1) assess subregional structural deformations, and (2) explore relationships between the neuroanatomical measures and clinical measures in unmedicated patients with schizophrenia, who were either drug-naïve or drug-free for at least 1 year and with overall minimal lifetime exposure to antipsychotics.

2. Experimental methods

2.1. Participants

Subjects included 21 patients with schizophrenia (19m/2f) and 21 comparison subjects (19m/2f), similar in age (patients: 30.7±1.6 mean±SD in years; controls: 31±1.8 mean±SD in years) (Table 1). Patients fulfilled DSM-IV and ICD-10 criteria for schizophrenia and had no other psychiatric axis I disorders (SCID interview) (First et al., 2001) and no current drug abuse or past history of drug dependence. Of these participants, 13 were drug naïve, 3 had been drug free for at least two years (2 had been treated with olanzapine 10mg for 12 weeks and 1 with quetiapine 300mg for 3 weeks), and 5 had been drug free for at least 1 year (1 had been treated with amisulpride 800mg for 6 weeks, 1 with 6mg risperidone for 12 weeks; 1 with olanzapine 10mg for 3 weeks; 1 with clozapine 200mg for 16 weeks; 1 with aripiprazole 20mg for 8 weeks). Psychopathology was assessed using the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) (Kay et al., 1987) (Table 1). Patients were recruited at the Charité University Medical Center’s Department of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy (Campus Charité Mitte).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical data of patients with schizophrenia and healthy controls

| Comparison subjects N=21 |

Subjects with schizophrenia (n=21) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean ± SD; range) |

31.1 ± 8.2; 18 – 47 |

30.7 ± 7.3; 19 – 48 |

||

| Sex (male/female) | 19/2 | 19/2 | ||

| Number of psychotic episodes | n/a | 0.48 ± 0.68 | ||

| PANSS total (mean ± SD) |

n/a | 93.5 ± 24.0 | ||

| PANSS positive (mean ± SD) |

n/a | 25.5 ± 7.2 | ||

| PANSS negative (mean ± SD) |

n/a | 24.5 ± 7.3 | ||

| Blunted affect (mean ± SD) |

n/a | 3.5 ± 1.1 | ||

| Medication | n/a | 13 drug naïve 3 drug-free for at least 2 years 5 drug-free for at least 1 year |

||

| ANCOVA (age, sex and TBV as covariates) |

||||

| F(1, 37) | p | |||

| Right caudate volumes | 3568 ± 131 | 3533 ± 120 | 0.001 | 0.984 |

| Left caudate volumes | 3533 ± 130 | 3504 ± 137 | 0.004 | 0.952 |

| Right putamen volumes | 3789 ± 145 | 3372 ± 119 | 7.744 | 0.008 |

| Left putamen volumes | 3778 ± 138 | 3355 ± 109 | 7.806 | 0.008 |

| Right nucleus accumbens volumes | 759± 39 | 678± 40 | 1.931 | 0.173 |

| Left nucleus accumbens volumes | 762 ± 40 | 675 ± 37 | 2.008 | 0.165 |

Mean striatal volumes are expressed in mm3. TBV = Total brain volume

Healthy comparison subjects were recruited through local newspaper advertisements and community word of mouth. Healthy controls had no history of psychiatric or medical illness as determined by clinical interview using the SCID I and II criteria for DSM-IV (First et al., 2001). Exclusion criteria for all subjects included head trauma, serious neurological or endocrine disorders, any medical condition or treatment known to affect the brain, or meeting DSM-IV criteria for mental retardation. The study was performed according to the Declaration of Helsinki. The local ethics committee approved the study, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants after the procedures had been fully explained.

2.2. Image data acquisition and analysis

Image acquisition and preprocessing

High-resolution 3D MPRAGE (Magnetization Prepared Rapid Gradient Echo) image data were obtained on a 1.5-T scanner (Magneton VISION Siemens®) with the following parameters: TR=9.7 ms; TE=4 ms; flip angle 12°; matrix 256 × 256; voxel size 1mm × 1 mm × 1mm). Each brain volume was corrected for radiofrequency field inhomogeneities (Sled et al., 1998) and placed into the standard coordinate system of the ICBM-305 average brain volume using a three-translation and three-rotation rigid-body transformation (Woods et al., 1998). This procedure corrects for differences in head alignment between subjects to assure that region of interest measurements are not influenced by different brain orientations between subjects (Woods et al., 1998).

Regions of interest delineation

The three components of the striatum were manually outlined on contiguous coronal slices following a detailed protocol. Caudate and putamen segmentation was similar to the protocol of Hwang et al. (2006), nucleus accumbens segmentation followed a protocol previously published by our group (Ballmaier et al., 2004). The rules applied in detail for each structure are described in Supplementary Information. Basal ganglia contours were outlined in all brains by a single investigator (C.H.) blind to group status. High intrarater and interrater reliability (two raters: C.H. and M.B.) was established (intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) > 0.90 for all three structures) by independent blinded measurements of 10 training scans.

Surface-deformation methods

We have described the methods for image analysis in detail elsewhere (Apostolova et al., 2006; Ballmaier et al., 2008; Narr et al., 2004) and will briefly summarize them here. Manually derived contours of each structure of the striatum were transformed into 3D parametric surface mesh models with normalized spatial frequency of the surface points within and across brain slices. Each structure was made into a parametric grid containing 100×150 grid points or surface nodes. This step ensures precise comparison of anatomy between subjects and groups at each surface point of the structure. A 3D medial curve was computed along the long axis for the surface model of each structure and radial distance measures (i.e., distance from the medial core to the surface) were estimated and recorded at each corresponding surface point. These values were used to generate individual distance maps for each structure that were combined to produce group average distance maps allowing for comparison of surface morphology between groups.

2.3. Statistical Analyses

Global region of interest volumes were compared between groups using the General Linear Model, with age, sex and total brain volume as covariates. Statistical analyses were also performed with only males. Post-hoc analyses were performed between patient subgroups, as well as between controls and subjects who were drug-naïve and between controls and those who had some prior medication exposure to ensure no significant residual effects of prior medication for previously treated subjects. Bonferroni corrections were used to control for the potentially inflated Type I error associated with performing tests for the three components of the striatum (right and left hemisphere). Therefore, the new threshold of significance was set at P <.009.

To evaluate regional differences in each basal ganglia volume as indexed by 15.000 measures of radial distance, the same statistical model was used at equivalent surface locations of each structure in 3D. For each structure, uncorrected two-tailed probability values were mapped onto the averaged surface models of the entire group and displayed in 3D. These statistical maps were adjusted for multiple comparisons using permutation methods with a threshold of p<0.05. Permutation testing as performed in the present paper has been validated (Anderson and Ter Braak, 2003; Anderson and Legendre, 1999) and used extensively by us and others (Ballmaier et al., 2008; Narr et al., 2004; Thompson et al., 2003). With permutation testing, the number of points that are significant in the true comparison are compared to the number of points observed by chance by performing 100,000 random assignments. These measures provide an overall significance value, that is, a P-value, for the whole map corrected for multiple comparisons.

In addition, linear regression analyses were performed to assess relationships between clinical measures and regional changes in striatal surface morphology within patients. Due to the lack of data regarding striatal structural changes and their clinical correlates in unmedicated schizophrenia, all correlation analyses were considered exploratory in nature. In these analyses, the total score of the Positive Syndrome Scale, the total score of the Negative Syndrome Scale, as well as the total score of the PANSS overall were used. In addition, correlations for scores from each of the seven items on the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale were examined separately. Permutation testing as described above was used to correct for multiple comparisons and to assess the overall significance of the surface map generated from the correlation analysis between radial distance and each clinical measure.

3. Results

Patients showed smaller total brain volumes than controls, which were at trend-level significant (total brain volume patients=1481±29 cm3; total brain volume controls=1562±29 cm3, P=0.056). Patients with or without any prior medications did not differ significantly and results were similar when each subgroup was compared with controls separately. Results of diagnostic group effects without females are provided in Figure 1 and Table 1 of Supplementary Information.

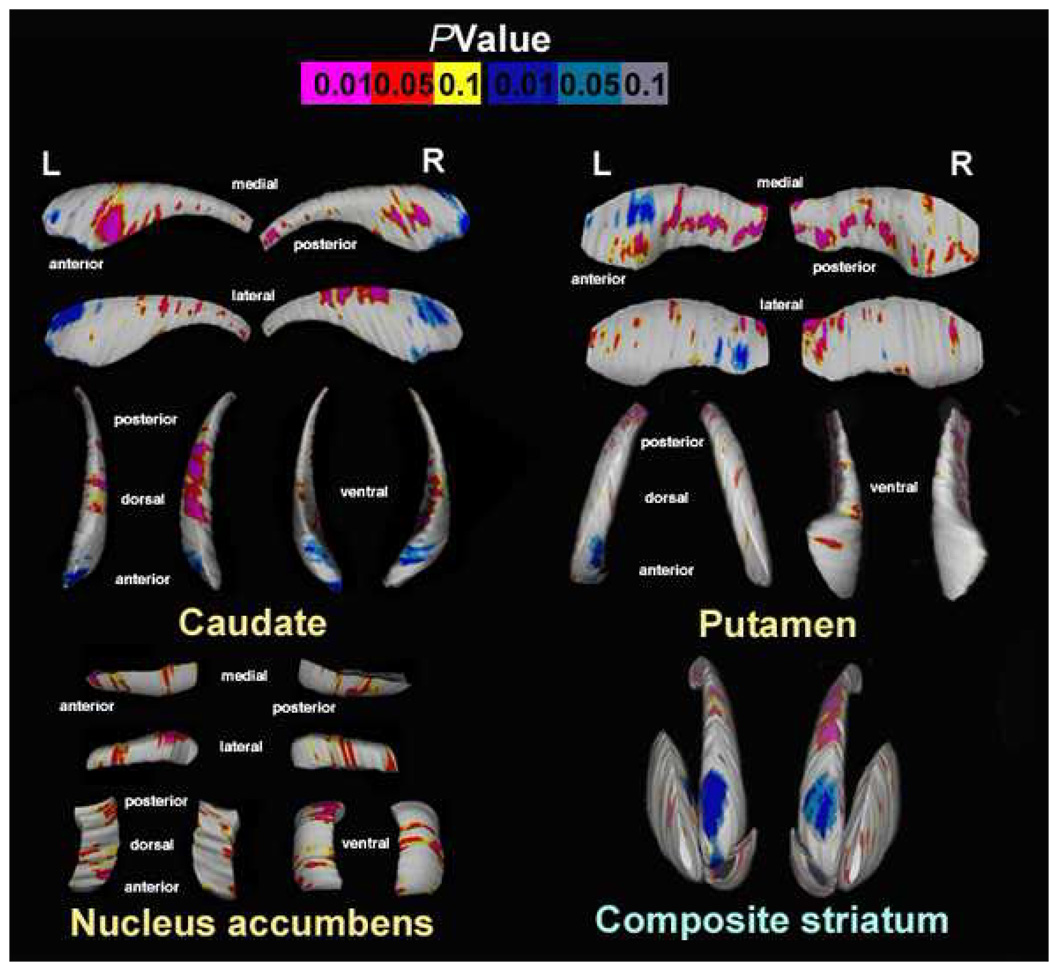

FIGURE 1.

Uncorrected surface maps depicting striatal shape differences in schizophrenia subjects (N=21) and healthy comparison subjects (N=21). Pink-to-red shadings indicate regions of contractions of the striatal surfaces (caudate, putamen, nucleus accumbens) in schizophrenia patients versus controls. Blue-to-light-blue shadings display regions of expansion of the surfaces. For all statistical maps, the color bar encodes the probability values associated with the F (1, 37)=4,11, p<.05 and F(1, 37)=7.38, p<.01. Corrected p-values after permutation testing for the whole map: Caudate: right, P=0.026; left, P=0.010; Putamen: right, P=0.043; left, P=0.006; Nucleus accumbens: right, P=0.076; left, P=0.056. R=Right; L=Left.

3.1. Caudate volume and surface mapping

For traditional volumetric analyses, the effect of diagnosis on left and right caudate volumes was not significant (Table 1). However, 3D surface statistics showed regional volume reductions in the right hemisphere mostly pronounced in medial anterior and dorsal body regions, and local decreases in the left hemisphere mostly pronounced in medial anterior regions in patients compared to controls. Local surface expansions were observed in the anterior poles of the caudate bilaterally in patients relative to controls (Figure 1). Permutation testing confirmed the overall significance of these regional results (corrected p-values: right, P=0.026; left, P=0.010).

3.2. Putamen volume and surface mapping

The diagnostic group effect on global volume differences was significant for both hemispheres (Table 1) with patients exhibiting smaller volumes compared to controls. Surface maps revealed local contractions in the right hemisphere in anterior and midposterior regions mostly pronounced on the medial surface in patients compared to controls (Figure 1). Similar patterns of local volume deficits were observed in the left hemisphere (Figure 1). Patients showed focal surface expansions in the medial anterior and lateral posterior region of the left hemisphere. Permutation testing confirmed the overall significance of these surface changes (corrected p-values: right, P=0.043; left, P=0.006).

3.3. Nucleus accumbens volume and surface mapping

No significant differences between groups were observed for global nucleus accumbens volumes. Surface mapping showed regional decreases in the left hemisphere in anterior dorsoventral and posteroventral regions, and local volume deficits in the right hemisphere in anterior dorsomedial and midventral regions in patients compared to controls. However, permutation testing revealed only a trend-level significance of these regional results (corrected p-values: right, P=0.076; left, P=0.056). Significant surface expansions were not observed.

3.4. Clinical relationships

The total score of the Positive Syndrome Scale and the Negative Syndrome Scale, as well as the PANSS subscale scores for positive symptoms were not significantly correlated with volumes or surface morphology of any striatal structure.

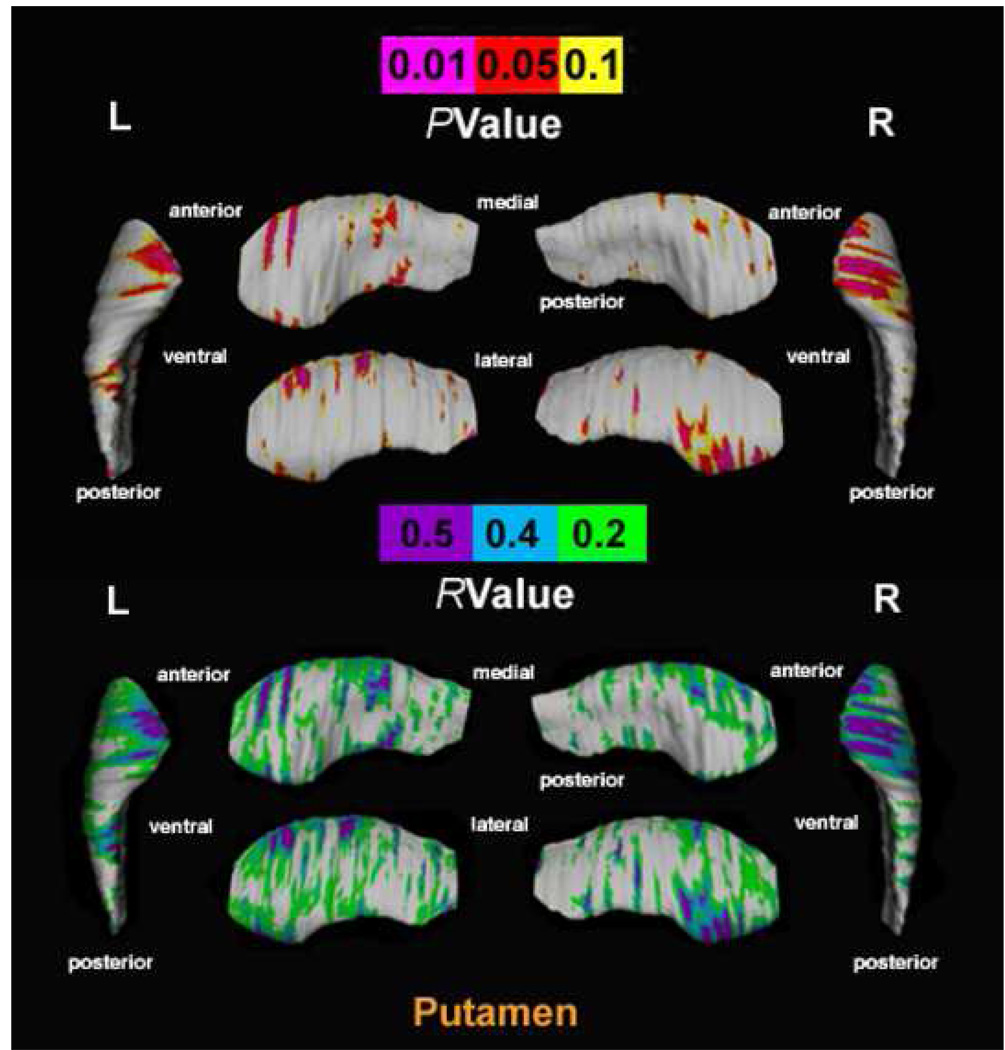

A significant positive correlation, confirmed by permutation tests, was observed between “blunted affect” scores (item 1 on the subscale for negative symptoms) and putamen surface contractions in the right hemisphere (corrected p-values: right, P=0.041). Trend-level significance was reached in the left hemisphere (corrected p-values: left, P=0.072). The correlation was mostly seen for the anterior poles (Figure 2). No significant relationship between blunted affect scores and surface morphology was found for the caudate and nucleus accumbens.

FIGURE 2.

Top: Uncorrected surface maps show relationships between the blunted affect score on the scale of negative symptoms of the PANSS and regional deformations of putamen surface indicated as pink-to-red shadings within unmedicated patients with schizophrenia (N=21). For all statistical maps, the color bar encodes the probability values for the observed effects. Regions of surface expansions were not observed in the above analysis. Corrected p-values after permutation testing for the whole map: right, P=0.041; left, P=0.072. Bottom: R-values are plotted onto the surface at each point of the putamen using a color code (purple/light-blue/light-green shadings) to produce an r-map, which displays the significance of the relationship corresponding to the probability values of the surface map (Top). R=Right; L=Left

In addition, we observed no significant relationship between volumes or surface morphology and any other clinical variable.

4. Discussion

In this report, our main significant findings are regional volume changes in medial/lateral aspects of the anterior caudate and in anterior and midposterior regions of the putamen pronounced on the medial surface, along with decreases of global putamen volume. Exploratory analyses suggest positive relationships between localized volume decreases in the anterior pole of the putamen and severity of blunted affect.

4.1. Caudate

Evidence in the literature on never-medicated subjects indicates both smaller caudate volumes (Chua et al., 2007; Corson et al., 1999; Keshavan et al., 1998) along with no volume changes (Gunduz et al., 2002), the latter being consistent with our results of no global caudate volume reductions. However, surface mapping enabled us to detect significant subtle anatomical differences in the caudate. One previous study using first-generation computerized methods in antipsychotic-naïve patients with schizophrenia reported shape differences in the anterior dorsolateral region of the right caudate (Shihabuddin et al., 1998), whereas another in medicated patients found bilateral local caudate volume loss in the anterior pole and anterior deflection of the tail, even in the presence of global volume increases (Mamah et al., 2007). Our findings of local volume decreases in medial/lateral anterior and dorsal body regions, as well as regional volume increases in the anterior poles of the caudate may add value to those previous investigations.

Indeed, the group by Mamah et al. (2007) almost exclusively investigated medicated subjects, which makes it difficult to disentangle which effects are due to antipsychotic medication and which are due to illness. Therefore, the anatomical distinctions observed here may more likely reflect changes related to the basic disease processes of schizophrenia. Projections to and from prefrontal and limbic cortices appear to occur in a gradient concentrated in anterior caudate regions (Lehéricy et al., 2004). Functional imaging data in primates and healthy humans further suggest the functional segregation of anterior and posterior caudate regions with respect to distinct working memory tasks (Levy et al., 1997). Notably, functional imaging work in schizophrenia reported aberrant activation of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and the head of the caudate during working memory performance (Manoach et al., 2000; Morey et al., 2005). Identifying regional abnormalities in caudate structure may thus help elucidate the underlying pathophysiological mechanisms associated with the disorder and also point to which functional systems are selectively disturbed in schizophrenia.

4.2. Putamen

Diagnostic effects in the putamen showed decreases in global volume as well as diffuse local surface contractions along with localized surface expansions. Although previous studies in antipsychotic-naïve patients have not found differences in putamen volumes compared to controls (Keshavan et al., 1998; Shihabuddin et al., 1998), studies on patients with first-episode psychosis and neurological soft signs or never-treated subjects with schizotypal personality disorder have described a reduction in putamen volume relative to healthy controls (Dazzan et al., 2004; Shihabuddin et al., 2001). Our findings of global volume deficits may be the structural correlate of putamen hypometabolism in schizophrenia. Previous data showing decreases of glucose metabolism in neuroleptic-naïve patients and patients after suspension of antipsychotic treatment (Holcomb et al., 1996; Shihabuddin et al., 1998) might indeed reflect reduced synaptic activity in glutamatergic corticostriatal neurons, leading to lower striatal size through reduction of trophic effects on the striatum (Grace, 2000).

Interestingly, our study revealed local volume changes in anterior and midposterior regions mostly pronounced on the medial surface. Pre-supplementary motor area projections are mainly directed to the anterior part of the putamen, whereas supplementary motor area projections predominate in the caudal tier of the putamen and premotor area projections in the medial putamen (Lehéricy et al., 2004). Impaired motor coordination is common in schizophrenia, and functional imaging studies using various motor tasks have described reduced sensorimotor cortex and posterior putamen activation, suggesting altered sensorimotor integration (Menon et al., 2001). Moreover, following the connectivity patterns of the anterior (associative) striatum with the frontal lobes, the anterior putamen is involved in cognitive processing, such as working memory related to motor planning (Lehéricy et al., 2004). In addition, functional imaging studies aimed at measuring synaptic activity in striatal dopamine afferents suggest that pharmacological models of psychosis and schizophrenia present with increased dopamine release in the associative striatum (Guillin et al., 2007; Heinz et al., 2002). Taken together, our findings may suggest disturbances in the network subserving functions associated with motor planning and executive control.

4.3. Nucleus accumbens

In our study, the nucleus accumbens did not show significant differences in volume, in accordance with previous studies in unmedicated (Gunduz et al., 2002) and medicated schizophrenia (Ballmaier et al., 2004; Mamah et al., 2007). However, trend-level significant local volume reductions were observed in patients. Notably, the nucleus accumbens appears to be specifically implicated in the attentional and cognitive deficits, and the dysfunction of reward processing in schizophrenia (Grace, 2000). Indeed, nucleus accumbens morphometry has been associated with thought disorder (Ballmaier et al., 2004) and functional imaging work found a link between negative symptom severity and reduced activation of the ventral striatum (Juckel et al., 2006), indicating that further research is needed in this area.

4.4. Surface mapping and clinical relationships

In our exploratory analysis of correlations between striatal morphology and clinical measures, patients exhibited a significant relationship between regional putamen surface contractions and affective flattening in the right hemisphere. The putamen may play a role in emotional processing, as suggested by functional imaging studies in depressed patients implicating the putamen in affective flattening (Bragulat et al., 2007) and anhedonia (Dunn et al., 2002). Studies on healthy subjects found putamen involvement in emotional distress (Sinha et al., 2004), motivational drives (Sewards and Sewards, 2003), and the expression of fear and anxiety (Hasler et al., 2007).

So far, studies in schizophrenia have relied on medicated subjects, with one study linking functional abnormalities of the putamen with olfactory disturbances and anhedonia (Piailly et al., 2006), whereas another ascribed interactions between alterations of putamen metabolism and emotional impairment to the effects of antipsychotics (Prince et al., 2000). In our previous work, relationships between reduced striatal dopamine receptor availability and affective flattening and avolition were also examined in the context of antipsychotic-induced effects (Heinz et al., 1998).

The present exploratory analysis in unmedicated patients describes a positive relationship between severity of affective flattening and local volume reductions in the anterior putamen suggesting a disruption of connectivity with the frontal lobes. Given the postulated importance of the prefrontal cortex in the regulation of emotional behavior, our data may imply that affective flattening involves abnormal connectivity in a distinct cortical-striatal circuit with the anterior putamen as a critical node.

4.5. Caveats

Limitations of the study should be noted. The overall group size was small. Future studies with a larger sample size and a proportionate number of females are warranted to confirm the regional alterations in striatal morphology and may also help clarify how these may be influenced by gender. When females were excluded from the analysis, trend-level significant surface contractions in nucleus accumbens morphology became not significant and differences in global putamen volumes, albeit significant, did not survive Bonferroni correction, suggesting perhaps that in particular alterations in accumbens morphology are less pronounced in schizophrenic males. However, the current sample size including only two females within each group, clearly does not have the statistical power to adequately investigate gender-related effects. In light of multiple testing on clinical measures, our observed positive relationship between regional putamen volume reduction and affective flattening in the right hemisphere should be considered as strictly explorative. Future research may investigate laterality effects, although our findings may reflect that power is lacking and not necessarily that laterality effects are present. Finally, although no differences emerged between subgroups, a larger sample size only including antipsychotic-naïve patients may validate our results.

4.6. Summary

Detailed spatial mapping of the striatum in unmedicated schizophrenia allowed us to detect regional volume changes in patients, prominent bilaterally in medial/lateral anterior regions of the caudate, as well as in anterior and midposterior regions of the putamen mostly pronounced on the medial surface. Exploratory analyses showed that localized volume reductions in the anterior putamen correlate with affective flattening.

Overall, the diagnostic effects appear more pronounced in the associative striatum and may provide valuable insight into the proposed abnormal connectivity of the corticostriatal loop in schizophrenia without the possible confounding effects of antipsychotic treatment. Moreover, the exploratory relationship between anterior putamen surface contractions and flattening affect may contribute to elucidate neural circuit dysfunctions implicated in disturbances of emotion processing.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Anderson MJ, Legendre P. An empirical comparison of permutation methods for tests of partial regression coefficients in a linear model. J. Statist. Comput. and Simul. 1999;62:271–303. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson MJ, Ter Braak CJF. Permutation tests for multi-factorial analysis of variance. J. Statist. Comput. and Simul. 2003;73:85–113. [Google Scholar]

- Apostolova LG, Dutton RA, Dinov ID, Hayashi KM, Toga AW, Cummings JL, Thompson PM. Conversion of mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer disease predicted by hippocampal atrophy maps. Arch. Neurol. 2006;63:693–699. doi: 10.1001/archneur.63.5.693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballmaier M, Toga AW, Siddarth P, Blanton RE, Levitt JG, Lee M, Caplan R. Thought disorder and nucleus accumbens in childhood: a structural MRI study. Psychiatry Res. 2004;130:43–55. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballmaier M, Narr KL, Toga AW, Elderkin-Thompson V, Thompson PM, Hamilton L, Haroon E, Pham D, Heinz A, Kumar A. Hippocampal morphology and distinguishing late-onset from early-onset elderly depression. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2008;165:229–237. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07030506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bragulat V, Paillère-Martinot M, Artiges E, Frouin V, Poline J, Martinot J. Dopaminergic function in depressed patients with affective flattening or with impulsivity: [18F]Fluoro-L-dopa positron emission tomography study with voxel-based analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2007;154:115–124. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2006.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breier A, Buchanan RW, Elkashef A, Munson RC, Kirkpatrick B, Gellad F. Brain morphology in schizophrenia: A magnetic resonance imaging study of limbic, prefrontal cortex, and caudate structures. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1992;49:921–926. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820120009003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chua SE, Cheung C, Cheung V, Tsang JTK, Chen EYH, Wong JCH, Cheung JPY, Yip L, Tai K, Suckling J, McAlonan GM. Cerebral grey, white matter and csf in never-medicated, first-episode schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 2007;89:12–21. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corson PW, Nopoulos P, Andreasen NC, Heckel D, Arndt S. Caudate size in first-episode neuroleptic-naïve schizophrenic patients measured using an artificial neural network. Biol. Psychiatry. 1999;46:712–720. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00079-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crespo-Facorro B, Paradiso S, Andreasen NC, O’Leary DS, Watkins GL, Ponto LL, Hichwa RD. Neural mechanisms of anhedonia in schizophrenia: a PET study of response to unpleasant and unpleasant odors. JAMA. 2001;286:427–435. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.4.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dazzan P, Morgan KD, Orr KG, Hutchinson G, Chitnis X, Suckling J, Fearon P, McGuire PK, Mallet RM, Jones PB, Leff J, Murray RM. The structural brain correlates of neurological soft signs in AESOP first-episode psychoses study. Brain. 2004;127:143–153. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn RT, Kimbrell TA, Ketter TA, Frye MA, Willis MW, Luckenbaugh DA, Post RM. Principal components of the Beck Depression Inventory and regional cerebral metabolism in unipolar and bipolar depression. Biol. Psychiatry. 2002;51:387–399. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01244-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbo M, Williams J. Structural clinical interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Patient Edition with psychotic screen, SCID-I/P W/PSY SCREEN. New York: New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Glenthoj A, Glenthoj BY, Mackeprang T, Pagsberg AK, Hemmingsen RP, Hernigan TL, Baaré WFC. Basal ganglia volumes in drug-naïve first-episode schizophrenia patients before and after short-term treatment with either a typical or an atypical antipsychotic drug. Psychiatry Res. 2007;154:199–208. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2006.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grace AA. Gating of the information flow within the limbic system and the pathophysiology of schizophrenia. Brain Res. Rev. 2000;31:330–341. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(99)00049-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillin O, Abi-Dargham A, Laruelle M. Neurobiology of dopamine in schizophrenia. Int. Rev. Neurobiol. 2007;78:1–39. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7742(06)78001-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunduz H, Wu H, Ashtari M, Bogerts B, Crandall D, Robinson DG, Alvir J, Lieberman J, Kane J, Bilder W. Basal ganglia volumes in first-episode schizophrenia and healthy comparison subjects. Biol. Psychiatry. 2002;51:801–818. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01345-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasler G, Fromm S, Alvarez RP, Luckenbaugh DA, Drevets WC, Grillon C. Cerebral blood flow in immediate and sustained anxiety. J. Neurosci. 2007;27:6313–6319. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5369-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinz A, Knable MB, Coppola R, Gorey JG, Jones DW, Lee KS, Weinberger DW. Psychomotor slowing, negative symptoms and dopamine receptor availability: an IBZM SPECT study in neuroleptic-treated and drug-free schizophrenic patients. Schizophr. Res. 1998;31:19–26. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(98)00003-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinz A. Dopaminergic dysfunction in alcoholism and schizophrenia: psychopathological and behavioral correlates. Eur. Psychiatry. 2002;17:9–16. doi: 10.1016/s0924-9338(02)00628-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holcomb HH, Cascella NG, Thaker GK, Medoff DR, Dannals RF, Tamminga CA. Functional sites of PET/FDG studies with and without haloperidol. Am. J. Psychiatry. 1996;153:41–49. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang J, Lyoo IK, Dager SR, Friedman SD, Oh JS, Lee JY, Kim SJ, Dunner DL, Renshaw PF. Basal ganglia shape alterations in bipolar disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2006;163:276–285. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.2.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juckel G, Schlagenhauf F, Koslowski M, Wüstenberg T, Villringer A, Knutson B, Wrase J, Heinz A. Dysfunction of ventral striatal reward prediction in schizophrenia. NeuroImage. 2006;29:409–416. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.07.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The positive and negative syndrome scale, PANNS for schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 1987;13:261–276. doi: 10.1093/schbul/13.2.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keshavan MS, Rosenberg D, Sweeney JA, Pettegrew JW. Decreased caudate volume in neuroleptic-naïve psychotic patients. Am. J. Psychiatry. 1998;155:774–778. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.6.774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehéricy S, Ducros M, Van De Moortele PF, Francois C, Thivard L, Poupon C, Swindale N, Ugurbil K, Kim SA. Diffusion tensor fiber tracking shows distinct corticostriatal circuits in humans. Ann. Neurol. 2004;55:522–529. doi: 10.1002/ana.20030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy R, Friedman HR, Davachi L, Goldman-Rakic PS. Differential activation of the caudate nucleus in primates performing spatial and nonspatial working memory tasks. J. Neuroscience. 1997;17:3870–3882. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-10-03870.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mamah D, Wang L, Barch D, de Erausquin GA, Gado M, Csernansky JG. Structural analysis of the basal ganglia in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Res. 2007;89:59–71. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.08.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manoach DS, Gollub RL, Benson ES, Searly MM, Goff DC, Halpern E, Saper CB, Rauch SL. Schizophrenic subjects show aberrant fMRI activation of dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and basal ganglia during working memory performance. Biol. Psychiatry. 2000;48:99–109. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(00)00227-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menon MF, Anagnoson RT, Glover GH, Pfefferbaum A. Functional magnetic resonance imaging evidence for disrupted basal ganglia function in schizophrenia. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2001;158:646–649. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.4.646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morey RA, Inan S, Mitchell TV, Perkins DO, Lieberman JA, Belge A. Imaging frontostriatal functions in ultra-high-risk, early- and chronic schizophrenia during executive processing. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2005;62:254–262. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.3.254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narr KL, Thompson PM, Szeszko P, Robinson D, Jang S, Woods RP, Kim S, Hayashi KM, Asunction D, Toga AW, Bilder RM. Regional specificity of hippocampal volume reductions in first-episode schizophrenia. Neuroimage. 2004;21:1563–1575. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2003.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pially J, d’Amato T, Saoud M, Royet JP. Left temporo-limbic and orbital dysfunction in schizophrenia during odor familiarity and hedonicity judgments. Neuroimage. 2006;29:302–313. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.06.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prince JA, Harro J, Blennow K, Gottfries CG, Oreland L. Putamen mitochondrial energy metabolism is highly correlated to emotional and intellectual impairment in schizophrenics. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2000;22:284–292. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(99)00111-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherk H, Falkai P. Effects of antipsychotics on brain structure. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry. 2006;19:145–150. doi: 10.1097/01.yco.0000214339.06507.d8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sewards TV, Sewards MA. Representations of motivational drives in mesial cortex, medial thalamus, hypothalamus and midbrain. Brain Res. Bull. 2003;61:25–49. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(03)00069-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shihabuddin L, Buchsbaum MS, Hazlett EA, Mehmet Haznedar M, Harvey PD, Newmann A, Schnur DB, Spiegel-Cohen J, Wei T, Machac J, Knesaurek K, Vallabhajosula S, Biren MA, Ciaravolo TM, Luu-Hsia C. Dorsal striatal size, shape, and metabolic rate in never-medicated and previously medicated schizophrenics performing a verbal learning task. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1998;55:235–243. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.3.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shihabuddin L, Buchsbaum MS, Hazlett EA, Silverman J, New A, Brickman AM, Mitropoulou V, Nunn M, Fleischman MB, Tang C, Siever LJ. Striatal size and relative glucose metabolic rate in schizotypal personality disorder and schizophrenia. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2001;58:877–884. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.9.877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha R, Lacadie C, Skudlarski P, Wexler BE. Neural circuits underlying emotional distress in humans. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2004;1032:254–257. doi: 10.1196/annals.1314.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sled JG, Pike GB. Standing-wave and RF penetration artifacts caused by elliptic geometry: an electrodynamic analysis of MRI. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging. 1998;17:653–662. doi: 10.1109/42.730409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi H, Koeda M, Oda K, Matsuda T, Matsushima E, Matsurra M, Asai K, Okubo Y. An fMRI study of differential neural response to affective pictures in schizophrenia. Neuroimage. 2005;22:1247–1254. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor S, Christensen JD, Holcomb JM, Garver DL. Volume increases in striatum associated with positive symptom reduction in schizophrenia: a preliminary observation. Psychiatry Res. 2005;140:85–89. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2005.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson PM, Hayashi KM, de Zubicaray G, Janke AL, Rose SE, Semple J, Herman D, Hong MS, Dittmer SS, Doddrell DM, Toga AW. Dynamics of gray matter loss in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurosci. 2003;23:994–1005. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-03-00994.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods RP, Grafton ST, Watson JD, Sicotte NL, Mazziotta JC. Automated image registration: II. Intersubject validation of linear and nonlinear models. J. Comput. Assist. Tomogr. 1998;22:153–165. doi: 10.1097/00004728-199801000-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.