Abstract

To determine whether TNF and TRAIL death receptors (DR), and decoy receptors (DcR), play a role in oligodendrocyte depletion in the lesions of chronic multiple sclerosis (MS), we investigated the presence and functionality of these molecules on oligodendrocytes in MS and non-MS brain tissue and on human oligodendrocytes in vitro. For this, we performed immunocytochemistry, Western blotting, TUNEL and FACS analysis for the presence of DR and apoptosis in sections of fresh frozen CNS tissue from cases of chronic MS, other neurologic diseases and normals, and in fetal human oligodendrocytes in vitro. The results showed that although oligodendrocytes demonstrated both DR and DcR, particularly in vitro, there was no predilection of the phenomenon for MS and apoptosis of oligodendrocytes, common in cultures after ligation with TRAIL, was negligible in CNS tissue in situ. Thus, death of oligodendrocytes by apoptosis was an infrequent event in all human CNS samples examined. We postulate that while oligodendrocyte apoptosis might prevail during the initial stages of MS, from our findings other mechanisms probably account for their loss in the established lesion and decoy receptors may play a protective role in oligodendrocyte survival.

Keywords: TRAIL, oligodendrocytes, cell death

1. Introduction

While it is well recognized that the pathogenesis of the inflammatory demyelinating lesion in multiple sclerosis (MS) is complex and possibly heterogeneic, there is consensus that initiating events have an immunologic, perhaps autoimmune, basis (Frohman et al., 2006). In support of this are numerous studies showing that the course of MS can be beneficially altered by a number of anti-inflammatory or immune-modulating therapies (Frohman et al., 2006; Noseworthy et al., 2005), many of which act on the pro-inflammatory cytokine profile to down-regulate inflammation. At the level of CNS pathology in MS, a major unresolved issue relates to the fate of the myelinating cell, the oligodendrocyte, during the evolution of the lesion. In the established lesion, total depletion of oligodendrocytes is common (Prineas and McDonald, 1997; Raine, 1997), but whether they die by classic apoptosis or a cytotoxic mechanism (necrosis), remains a question. Since patterns of oligodendrocyte death have been used to determine lesion type and/or stages in MS (Lucchinetti et al., 2000; Lucchinetti et al., 1996), clarification of this issue might have considerable pathogenetic import. One cytokine frequently implicated in lesion growth in MS is tumor necrosis factor (TNF), a proinflammatory molecule linked to oligodendrocyte injury and death (D’Souza et al., 1996; Jurewicz et al., 2005; Selmaj and Raine, 1988).

The TNF family of cytokines and their receptors (TNFR), are well known to play critical roles in immune regulation and inflammation and have important functions in cell death mechanisms in all tissues. Some members of the TNFR family of homologous transmembrane proteins bear an intracellular death domain and are able to mediate apoptosis directly. The death receptors (DR), TNF-R1 (DR1), and Fas (DR2), are well-characterized members of the group and have been studied previously in MS (Bonetti and Raine, 1997; Dowling et al., 1996; D’Souza et al., 1996). DR3 is preferentially expressed by lymphocytes and is induced after T-cell activation (Bodmer et al., 1997). DR4 and DR5 (TRAIL-R1 and TRAIL-R2), are two of five cloned receptors of the TNF-related apoptosis–inducing ligand, TRAIL (Pan et al., 1997; Sheridan et al., 1997; Walczak et al., 1997; Wiley et al., 1995). Two other receptors of TRAIL – DcR1 and DcR2 (TRAIL-R3 and TRAIL-R4), are thought to be protective and to act as decoy receptors (Degli-Esposti et al., 1997a; Degli-Esposti et al., 1997b). TRAIL and its receptors are constitutively expressed in a variety of normal tissues and tumor cells (Pan et al., 1997; Schneider et al., 1997; Wiley et al., 1995). More recent studies have shown TRAIL and its receptors in human brain tissue (Dorr et al., 2002; Frank et al., 1999; Nakamura et al., 2000). DR6, one of the newer members of the DR family, is widely expressed in human tissues (Pan et al., 1998). RT-PCR data indicate that DR6 is abundant in normal human CNS (Harrison et al., 2000).

Since the receptors DR3 – DR6; DcR1 and DcR2, and TRAIL ligand have not been examined in MS, the present study was undertaken to investigate these molecules in chronic lesions and whether expression was related to ongoing disease and oligodendrocyte pathology. To investigate possible functional implications of DR, human fetal oligodendrocytes were grown in vitro, exposed to TRAIL, and apoptosis measured by the TUNEL technique for DNA fragmentation.

2. Materials and Methods

Tissue samples

All tissues used in this study came from a brain bank maintained in this laboratory and the tissue was collected with appropriate approval from an institutional IRB. Cryostat sections from OCT-embedded blocks from 10 cases of MS displaying chronic active and chronic silent lesions, 5 cases of other neurologic diseases (OND), one each, amyotropic lateral sclerosis, olivopontocerebellar degeneration, and stroke, and 2 Alzheimer’s, and CNS tissue from 4 normal cases, were used in this study (see Table 1). For neuropathology, sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin, and Luxol fast blue for myelin. For Western blotting, tissue was stored as fresh frozen slices until needed.

TABLE 1.

Clinical summary of case studied

| Patient # | Diagnosis | Gender/Age | Disease Duration (yrs.) | Cause of Death | PMI (hrs) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | PPMS | F/31 | 8 | Resp. failure | 3 |

| 2 | PPMS | F/32 | 3 | Bronchopneum. | 8 |

| 3 | PPMS | F/37 | 17 | Resp. failure | 6 |

| 4 | SPMS | F/38 | 11 | Bronchopneum. | 8 |

| 5 | SPMS | M/46 | 15 | Cardiac arrest | 8 |

| 6 | SPMS | F/59 | 35 | Bronchopneum. | 8 |

| 7 | SPMS | F/56 | 21 | Cardiac arrest | 2 |

| 8 | SPMS | F/55 | 20 | Sepsis | 6 |

| 9 | SPMS | F/49 | 15 | Bronchopneum | 8 |

| 10 | SPMS | M/60 | 16 | Bronchopneum | 9 |

| 11 | Stroke | F/80 | 12 hrs. | Stroke | 5 |

| 12 | ALS | F/49 | 5 | Bronchopneum. | 8 |

| 13 | OPCD | M/31 | 4 | Bronchopneum. | 4 |

| 14 | Alzheimer’s | F/73 | n/a | Cardiac arrest | 5 |

| 15 | Alzheimer’s | M/68 | n/a | pneumonia | 7 |

| 16 | Normal | F/84 | n/a | Pulmonary embollus | 8 |

| 17 | Normal | M/62 | n/a | Cardiac arrest | 6 |

| 18 | Normal | F/88 | n/a | Cardiac arrest | 7.5 |

| 19 | Normal | M/72 | n/a | Cardiac arrest | 9 |

With regard to lesion staging, chronic active MS lesions display a sharp edge, perivascular cuffs of infiltrating cells, lipid-laden macrophages, hypertrophic astrocytes, some degenerating axons and ongoing demyelination. At the lesion margin, an increased number of oligodendrocytes and some remyelination may be seen. The demyelinated lesion center is usually hypocellular, containing naked axons embedded in a matrix of scarring (fibrous) astrocytes, lipid-laden macrophages, a few infiltrating leukocytes, and virtually no oligodendrocytes. Chronic silent lesions are defined by sharply demarcated, gliotic, chronically demyelinated, hypocellular areas of white matter lacking inflammatory activity, with variable degrees of axonal loss and severe depletion of oligodendrocytes.

Immunocytochemistry

Frozen sections were processed as previously described (Cannella and Raine, 2004), and incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies against the following: mouse anti-TRAIL (R&D, Minneapolis, MN); polyclonal goat anti-DR4/Trail-R1 (R&D); polyclonal goat anti-DR5/TRAIL-R2, anti -TRAIL-R3/DcR1 (Alexis Corp., Lausen, Switzerland), and TRAIL-R4/DcR2 (R&D); mouse anti-DR3 (Biolegend, San Diego, CA), and polyclonal rabbit anti-DR6 (Alexis Corp). For phenotypic controls, mAbs were used against: CD68 (Dako Corp., Carpinteria, CA), CNPase (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), GFAP-Alexa 488 (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR), and CD45 (Dako), for the staining of microglia, oligodendrocytes, astrocytes and leukocytes, respectively. Secondary biotinylated antibodies were applied for 1h at room temperature followed by the avidin-biotin-horseradish peroxidase complex (ABC) reagent (Vector Labs., Burlingame, CA), for another 1h. The chromogen used was 3,3′ diaminobenzidine (DAB). In addition to the above immunoperoxidase staining, double-label immunofluorescence was used to confirm the identity of positive cells, using anti-mouse IgG-Cy2 (Jackson Immunoresearch, West Grove, PA), with the phenotypic monoclonal antibodies and anti-rabbit IgG-Alexa 568 and anti-goat IgG-Alexa 568 (Molecular Probes), with the polyclonal receptor antibodies. Negative controls consisted of omission of primary antibodies and were performed to exclude non-specific staining. Immunoreactivity was scored in a blinded fashion by two observers on a scale from 0 to 4+, as reported previously (Cannella and Raine, 1995).

Western blots

Freshly thawed samples of human white matter were processed as described previously (Cannella and Raine, 2004). Immunodetection for DR was performed by overnight incubation at 4°C with primary antibody and as a standard, anti-tubulin antibody (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Blots were incubated with horseradish peroxidase-labeled secondary Ab (Southern Biotechnology), for 1h and then washed and developed with an ECL kit (Amersham, Piscataway, NJ). The bands were quantitated by scanning densitometry and expressed as a ratio over the standard to correct for protein loading.

TUNEL

To investigate the degree and localization of apoptosis in vivo and in vitro, the terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT)-mediated deoxyuridine triphosphate nick-end labeling (TUNEL) technique was applied to frozen sections of MS, OND and normal CNS tissue, according to the manufacturer’s instructions (R&D). Immunohistochemistry was performed to characterize cell phenotype. Sections were post-fixed with a formaldehyde reagent – BD Cytofix/Cytoperm (Becton Dickinson Biosciences Pharmingen, San Diego, CA), for 15 min, washed and incubated with the labeling reaction mixture for 60 min at 37°C. For negative control purposes, TdT enzyme was omitted from the reaction mixture. As a positive control, sections were treated with nuclease which produced staining of all nuclei. Cell phenotype (oligodendrocyte and infiltrating cells), was visualized using horseradish peroxidase with DAB as substrate, and the TUNEL reaction with streptavidin-alkaline phosphotase and neofuchsin as substrate. The number of apoptotic cells was quantitated by counting TUNEL- positive cells per 40× field (approximately 200 fields), and reported as the number of positive cells per mm2. Statistical significance was determined using the Student’s t test.

Cell culture

Human oligodendrocytes were isolated from spinal cords of electively-aborted fetuses, obtained from the Einstein Human Fetal Tissue Repository (New York, NY), in accordance with approved Internal Review Board protocols. Primary cultures were established from 18–22 week gestation fetal spinal cords, as described previously (Omari et al., 2005). Oligodendrocyte cultures were maintained in N2B3 medium alone, or supplemented with 10 ng/ml PDGF-AA (Sigma), and media was replenished every other day. In initial experiments, cells were exposed to doses of 10, 100 and 1000 ng/ml of TRAIL. The optimal dose was determined to be 100 ng/ml. Since cyclohexamide has been shown by others to be necessary for increasing TRAIL activity (Li et al., 2003; Matysiak et al., 2002), it was added to the cells before TRAIL treatment and simultaneously with TRAIL to determine the best method of treatment. It was found that pre-treatment was no more effective and in all further experiments, it was added simultaneously with TRAIL. The optimal time of exposure to TRAIL was then determined by exposing the cells for two different timepoints: 6h and 16 h. The shorter time period was found to be better. After 5 days in vitro, duplicate cultures were treated for 6h with 100 ng/ml SuperKillerTrail (Alexis) alone, or in combination with cyclohexamide (5 μg/ml, Sigma), to investigate the role of TRAIL receptors on oligodendrocytes. Cells maintained in N2B3 media alone served as negative controls. Experiments were repeated 4–5 times.

FACS Analysis

For fluorescence microscopy of cultured cells and FACS analysis, cells were stained in a manner similar to the above-described procedures with CNPase and visualized with secondary antibodies directly conjugated to Alexa568, and TUNEL-positive cells were visualized with Streptavidin-Alexa488. For FACS analysis, cells were trypsinized and analyzed at 2×105 cells on a FACScan flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, Sunnyvale, CA), with the use of software WINMD12.8 (Trotter). Negative controls omitting primary antibodies were run in parallel. FACS analysis was repeated 3 times.

3. Results

Death receptors in CNS tissue

The results of the immunocytochemical analysis are summarized in Table 2, which shows average levels of selected TNFR death receptors, decoy receptors and the ligand, TRAIL, in CNS tissue from active and silent MS lesions, OND and normal cases. Reactivity for DR varied among microglia, astrocytes, oligodendrocytes and infiltrating cells, and in some cases, the same molecule was expressed by several cell types.

TABLE 2.

TNF and TRAIL receptor expression in human CNS tissue

| DR3 | DR4 (TRAIL-R1) | DR5 (TRAIL-R2) | DR6 | DcR1 (TRAIL-R3) | DcR2 (TRAIL-R4) | TRAIL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACTIVE MS | + OL | ± OL | ± OL | ||||

| ± M | + M | ± M | + M | ++ M | |||

| n=4 | + A | + A | ± A | ± A | |||

| + INF | + INF | + INF | + INF | + INF | + INF | + INF | |

|

| |||||||

| SILENT MS | ± OL | + OL | + OL | ± OL | |||

| ± M | ± M | ++ M | ++ M | + M | |||

| n=5 | ± A | ± A | ± A | ± A | |||

|

| |||||||

| OND | + OL | ++ OL | ± OL | ||||

| ± M | ± M | + M | + M | ||||

| n=2 | ± A | ||||||

|

| |||||||

| NORMAL | ± OL | ++ OL | ± OL | ||||

| n=4 | ± M | ± M | ± M | ||||

| + A | ± A | ||||||

Scored on a 0 to 4 scale based on extent and degree of immunoreactivity.

OL = oligodendrocyte

A = astrocyte

M = microglia

INF = infiltrating cells

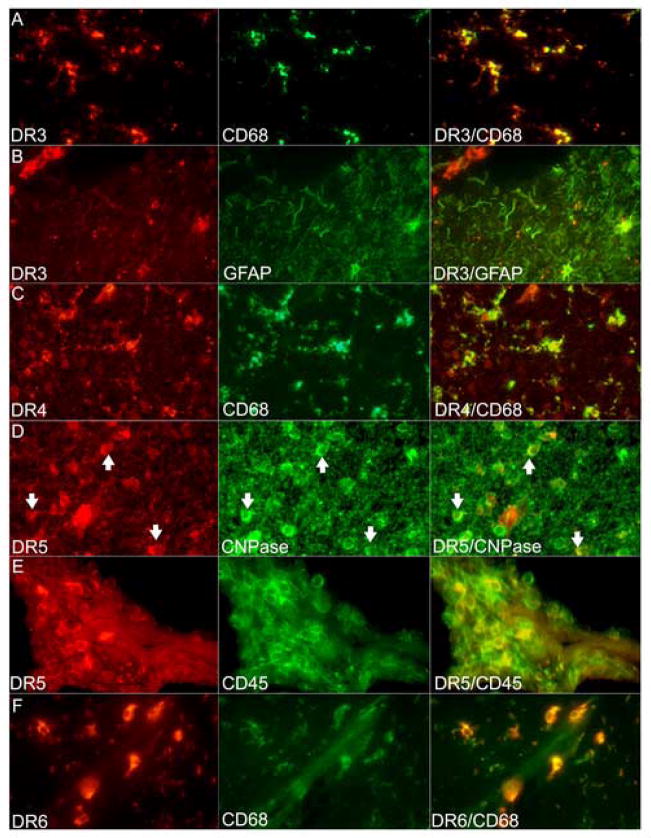

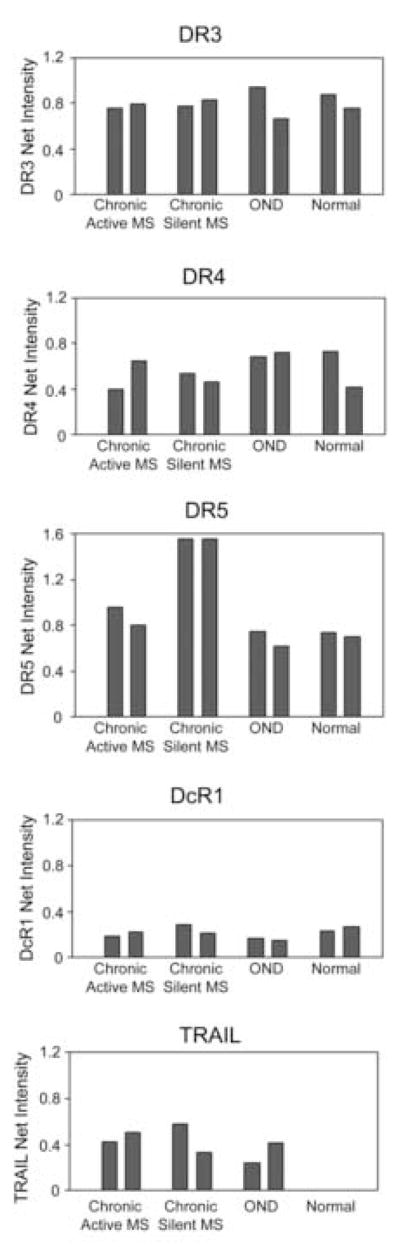

DR3 reactivity was seen at moderate levels on astrocytes, and at low levels on microglia and perivascular macrophages (Figure 1A). Chronic active MS lesions showed DR3 on inflammatory cells in perivascular cuffs and on astrocytes (Figure 1B). In chronic silent lesions, DR3 was seen at low levels on all cell types (Table 2). However, Western blots failed to show any quantitative differences between groups (Figure 3). Immunoreactivity for DR4 was found at low levels on microglia and infiltrating cells (Figure 1C), and at similar levels on astrocytes in silent lesions and normal CNS. In active lesions, DR4 expression was higher on astrocytes. Western blots showed differences in expression between cases within the same group, e.g. chronic active MS and normal CNS, rendering conclusions on quantitative differences between MS and normal CNS difficult. DR5 was seen consistently on oligodendrocytes in all cases (Table 2; Figure 1D), with higher levels in MS and OND, compared to constitutive levels in normal brain tissue. In active lesions, DR5 was also seen on microglia and infiltrating cells (Figure 1E), and in silent lesions, on astrocytes at low levels. In grey matter, DR5 immunoreactivity was seen on neurons. Western blotting showed an increase in DR5 expression in chronic silent lesions compared to other groups (Figure 3). DR6 was expressed on microglia in all groups (Table 2; Figure 1F), with up-regulation in active and silent lesions. Astrocytes and inflammatory cells also showed low-level reactivity in active MS lesions.

Figure 1.

Double immunofluorescence confirms the phenotype of cells immunoreactive for DR around MS lesions. All figures 400×. (A–B) DR3 positivity seen on CD68+ microglia and on GFAP+ astrocytes. Note the DR3+ inflammatory cells in the upper left corner in (B). (C) DR4+ cells were identified in a chronic active MS lesion to be microglia shown in the merged image on the right. (D) DR5+ cells were CNPase+ oligodendrocytes (arrows). (E) Active MS lesion showed DR5 reactivity also in perivascular inflammatory cells (CD45+). (F) DR6 reactivity was predominantly microglial as verified by colocalization with CD68 in the merged image to the right.

Figure 3.

Western blots (upper horizontal panel in each figure), show immunoreactivity for DR in white matter from chronic active and chronic silent MS lesions, other neurological diseases (OND), and normal subjects (n=2 for each group). Densitometric analysis (histograms) of blots suggests up-regulation of DR5 protein levels in chronic silent MS lesions. DR3, DR4 and DcR1 showed no differences among the groups. Levels of the ligand, TRAIL, were increased in MS and OND compared to normal CNS, where it was barely detectable.

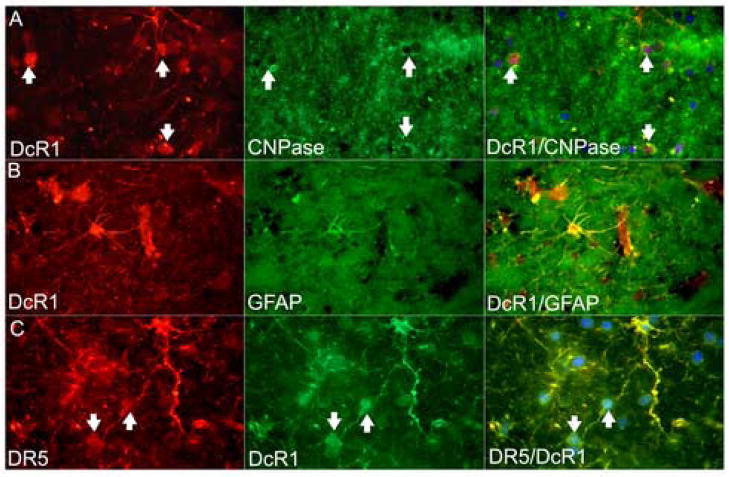

Decoy receptors in CNS tissue

The decoy receptor, DcR1 (TRAIL-R3), was found constitutively at moderately high levels on oligodendrocytes in normals and OND, and at lower levels in MS (Figure 2A). In chronic active lesions, it was also expressed by microglia and infiltrating cells and in silent lesions and OND, by astrocytes at low levels (Figure 2B). Double-labeling for DcR1 and DR5 showed colocalization on cell bodies with the phenotype of oligodendrocytes as well as on astrocytes and their processes (Figure 2C). Neuronal positivity for DcR1 was seen in grey matter. Western blots showed no significant differences in levels between the groups. DcR2 (TRAIL-R4), occurred almost exclusively on microglia (Table 2), higher in MS and lower in normals.

Figure 2.

(A) Oligodendrocyte immunoreactivity for DcR1 at the edge of a chronic active MS lesion was confirmed by colocalization with CNPase (arrows). (B) Astrocytes were also positive for DcR1, shown here by double-staining with GFAP. (C) Colocalization of DR5 (TRAIL-R2) and DcR1 (TRAIL-R3) on oligodendrocytes (arrows), and astrocytes.

TRAIL in CNS tissue

Low level expression of TRAIL ligand was found on oligodendrocytes in all cases, with some reactivity on microglia in silent lesions and perivascular infiltrating cells in active lesions (Table 2). Interestingly, TRAIL levels were higher in established MS lesions and lower in normals and OND. Western blotting revealed an increase in TRAIL in MS and OND compared to barely detectable levels in normals.

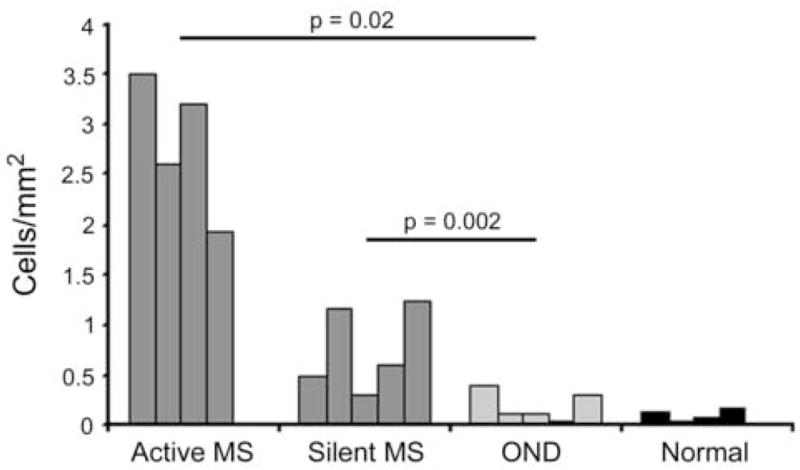

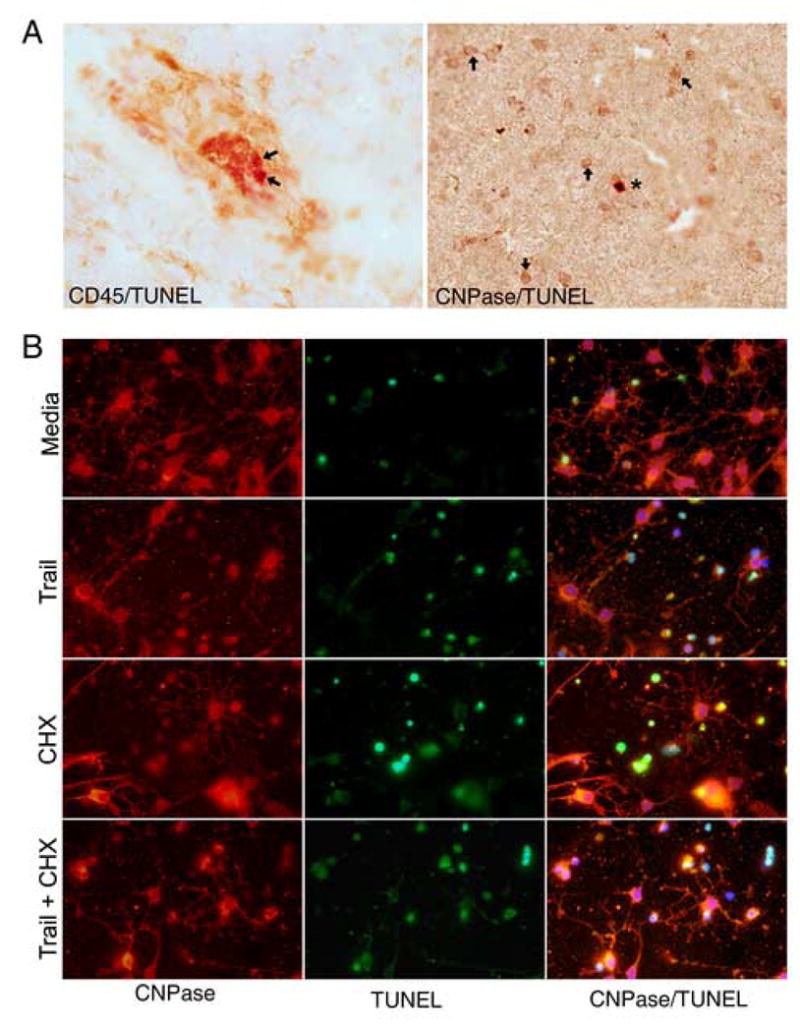

Quantitation of apoptosis in situ

Chronic active lesions (n=4), showed the highest levels of apoptosis (mean, 2.8±0.7cells/mm2 – Figure 4), due primarily to TUNEL-positive infiltrating cells in perivascular cuffs that were also CD45+ (Figure 5A). Silent lesions (n=5), showed lower levels of apoptosis (mean, 0.8±0.4 cells/mm2 –Figure 4), related to decreased inflammatory activity. The degree of apoptosis observed in CNS tissue from 5 cases of OND and 4 normals, was negligible (mean, 0.2±0.15 and 0.1±0.07cells/mm2, respectively - Figure 4). The difference in the levels of TUNEL-positive cells was found to be statistically significant between that seen in chronic active MS and OND (p = 0.02), and between chronic silent MS and OND (p =0.002), using the t-test. In general, there was minimal apoptosis in parenchymal cells in CNS tissue from all groups. Occasionally, an apoptotic oligodendrocyte was seen around an active MS lesion, but this was infrequent (Figure 5A). Thus, although oligodendrocytes showed expression of DR5 (Figure 1D), apoptotic oligodendrocytes in chronic lesions were rare. The latter may have been related to the protective effect of DcR1 on the same cell type (Figs. 2A & C), see above. The negligible levels of oligodendrocyte apoptosis in normals and OND may have been a reflection of the higher levels of DcR1 on oligodendrocytes (Table 2).

Figure 4.

This histogram illustrates the average number of TUNEL positive cells per square millimeter in the CNS of MS (chronic active, n = 4; chronic silent, n = 5), OND (n = 5) and normal cases (n = 4). Levels of TUNEL-positive cells were significantly different between those seen in active MS and OND (p = 0.02), and between silent MS and OND (p =0.002), using the Student’s t-test.

Figure 5.

(A) Representative fields showing, on the left, two apoptotic (red), CD45+ inflammatory cells (arrows), in a perivascular cuff around a vessel with a collapsed lumen in an active MS lesion. On the right, a rare TUNEL-positive red oligodendrocyte (asterisk), is seen among the numerous healthy (CNPase +) oligodendrocytes (arrows). (B) Treatment with TRAIL induces apoptosis of oligodendrocyte in vitro. Morphologic assessment revealed that treatment with TRAIL alone (second row), increased the number of apoptotic cells over control (media), baseline levels (first row), as did treatment with cyclohexamide alone (third row). TRAIL and cyclohexamide combined (below), appeared to have an additive effect.

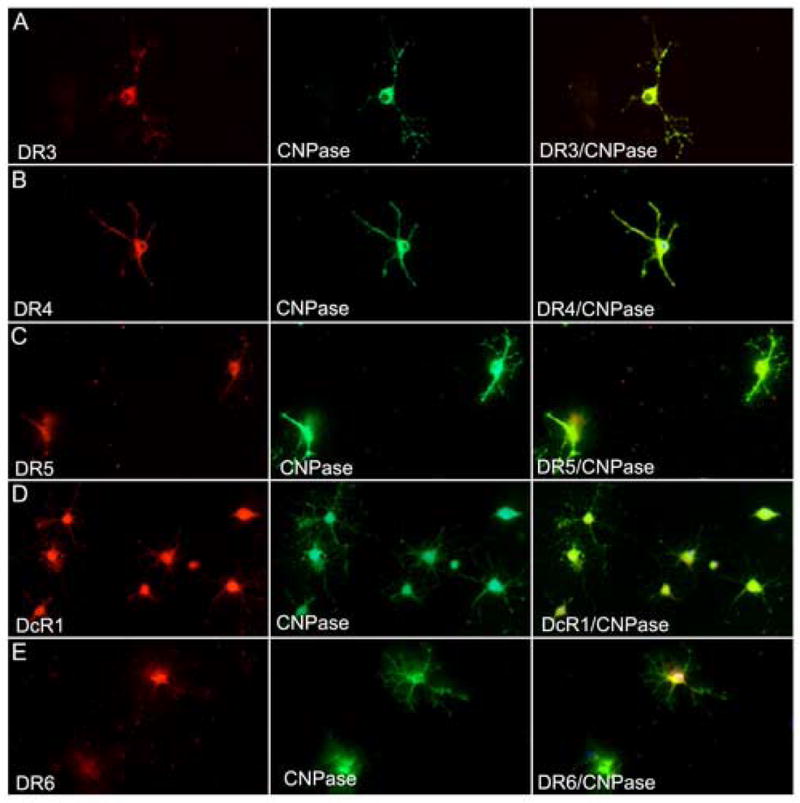

DR on oligodendrocytes in vitro

Oligodendrocyte cultures were established from human fetal spinal cord and the cells analyzed for DR in vitro. Immunocytochemistry revealed expression of DR3, DR4, DR5, DR6, as well as the decoy receptors, DcR1 and DcR2 (Figure 6). The findings were somewhat different from adult CNS tissue in situ where DR4 and DR6 were not observed on oligodendrocytes. Widespread oligodendrocyte reactivity for DR in vitro was probably a combination of developmental and tissue culture-related phenomena.

Figure 6.

Human fetal oligodendrocytes show surface expression of DR in vitro. In A–E, mature CNPase-positive oligodendrocytes show double-staining for DR3 (A), DR4 (B), DR5 (C), DcR1 (D) and DR6 (E).

Treatment of oligodendrocytes with TRAIL in vitro

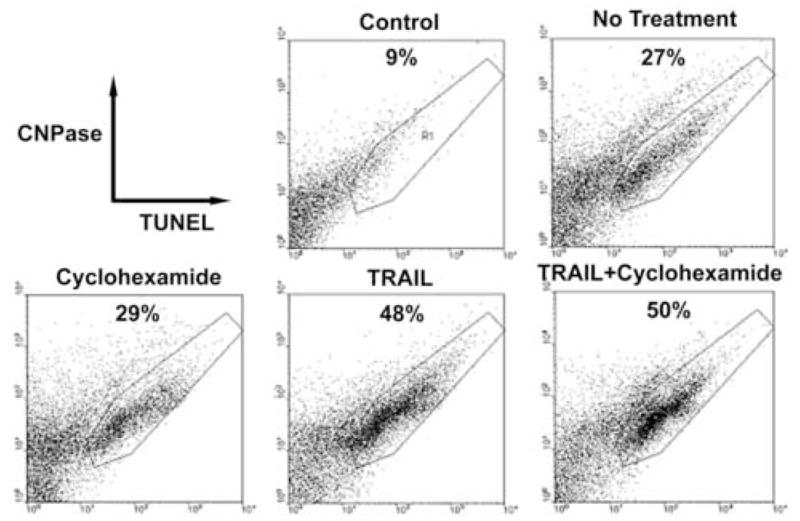

To examine whether TRAIL receptors on oligodendrocytes were functional, human fetal oligodendrocyte cultures were treated with TRAIL then examined for evidence of apoptosis. Morphologic assessment revealed TUNEL-positive, CNPase-positive cells (Figure 5B). Process-bearing, differentiated CNPase+ cells undergoing apoptosis were rare compared to rounded-up apoptotic CNPase+ cells. Treatment with TRAIL alone increased the number of apoptotic cells over baseline levels, as did treatment with cyclohexamide alone. TRAIL and cyclohexamide combined appeared to have an additive effect (see Figure 5B).

To quantitate the effect of TRAIL on oligodendrocyte apoptosis, cultures were analyzed by FACS. The results showed that treatment with TRAIL increased the percentage of CNPase+ TUNEL+ cells from a baseline level of 27% (no treatment), to 48% (Figure 7). Cyclohexamide alone had a minor effect (29%), and combined with TRAIL, this increased to 50%.

Figure 7.

FACS analysis of TRAIL-induced apoptosis in oligodendrocyte cultures. 2 × 105 cells were analyzed by two color immuno-flow cytometry. Representative plot from one of 3 experiments is shown. The panels indicate different treatments of human oligodendrocytes in vitro. The values indicate the percentages of TUNEL-positive cells.

4. Discussion

In the present study, we examined MS and non-MS CNS tissue for a novel group of DR known to be involved in apoptosis (DR3, 4, 5 and 6). Having determined their presence in CNS tissue in situ, we then tested TRAIL DR functionally on oligodendrocytes in vitro. Finally, we investigated and quantitated classical apoptosis in situ by DNA fragmentation. With different MS lesion types plus control CNS tissue, our findings have failed to support a significant role for apoptosis in the loss of oligodendrocytes from the established MS lesion, both active and silent. Expression of DR proved to be a constitutive property and a common feature in CNS tissue from all groups. However, while the incidence of apoptosis, as assessed by TUNEL staining, was greatest in MS, this was found to involve CD45+ infiltrating cells, not parenchymal cells. Furthermore, there was no overt difference in expression of DR between MS and controls although shifts in expression towards microglia occurred in MS and OND. Astrocytes and microglia were the main cells showing DR, except for DR5 which displayed a predilection for oligodendrocytes. Quantitatively, westerns showed higher levels of DR5 in chronic silent MS lesions. Westerns also showed up-regulation of TRAIL in MS and OND, indicating that this was not MS-specific.

Although observed herein but not a focus of the present study, neuronal TRAIL DR and DcR expression has been extensively studied. One study reported TRAIL induction of apoptosis in human brain slices (Nitsch et al., 2000), a second examined TRAIL ligand/receptors in brain tissue obtained from individuals with epilepsy (Dorr et al., 2002), and a third reported TRAIL-related neuronal death in a mouse model of MS (Aktas et al., 2005). There are no reports analyzing DR in MS tissue. While similarities between the present study and that of Dorr et al.(2002), were seen in DR4 and DR5, the DcR1 and DcR2 patterns were somewhat different with oligodendrocytes and neurons being the main cells expressing DcR1 in this study [versus neurons only (Dorr et al., 2002)], and microglia here showing DcR2 [versus oligodendrocytes and neurons (Dorr et al., 2002)]. In addition, the latter authors were unable to find TRAIL in human CNS. To what extent these differences may have been related to the source of the CNS tissue tested and antibodies used, remains to be seen. These differences notwithstanding, it is interesting from our work that regardless of condition (MS, OND, normal), one decoy receptor (DcR1), was preferentially expressed by oligodendrocytes, while the other (DcR2), was prominent on microglia. Considering that both microglia and oligodendrocytes also expressed different TRAIL DR (DR4 and DR5, respectively), this may indicate that the relative ratio of the respective death versus decoy receptor expression on these two cell types may be a determining factor in their survival. Furthermore, it would appear that different cell types may be protected by different receptors, a more efficient system biologically.

Examination of human fetal oligodendrocytes in culture showed both presence and functionality of DR following ligation with TRAIL. Previous studies using adult human oligodendrocytes (Matysiak et al., 2002), came to similar conclusions and went on to show that DR4 was the receptor responsible for apoptosis. These studies in vitro appear to support a role for DR in oligodendrocyte death, an observation not supported by our parallel studies of CNS tissue in situ. Whether this reflects in vitro/in vivo differences or non-apoptotic functions of DR, as proposed previously (Wajant, 2003), are possibilities.

Oligodendrocyte depletion in MS and its association with apoptosis has been the subject of many studies, some claiming apoptosis not to be prominent (Bonetti and Raine, 1997; D’Souza et al., 1996), and others claiming it to be a significant mechanism (Barnett and Prineas, 2004; Dowling et al., 1996; Lucchinetti et al., 1996). However, considerable uncertainty as to the fate of oligodendrocytes in MS still exists due in some part to the fact that the criteria for apoptosis differ among studies (Barnett and Prineas, 2004; Lucchinetti et al., 2000). More recently, the distinction between the different classical death pathways has become less clear (Jaattela and Tschopp, 2003). This may be a contributing factor to differences of opinion between investigators examining oligodendrocyte death processes in MS. Given that oligodendrocyte apoptosis was a rare event in this study on established MS lesions, one has to reconcile the findings with how and when depletion of this cell type occurs in MS. Major oligodendrocyte loss is almost certainly an early event of short duration occurring during the initial acute stages, and the window of opportunity for its detection is probably very narrow. Unfortunately, the chances of obtaining autopsy tissue containing the earliest lesions, are slim since this stage has been proposed to last for a few hours only (Barnett et al., 2006). Since the course of MS evolves over several decades and chronic lesions are known to continue to expand during the relapsing-remitting phase, the same mechanism of oligodendroglial cell death may or may not prevail. However, not to be excluded is that oligodendrocyte apoptosis occurring at an exceedingly low rate may still be the cause of oligodendrocyte depletion in MS. Although ample evidence of apoptotic infiltrating cells was consistently found in chronic active lesions, oligodendrocytes were only rarely TUNEL-positive. These results are not in accord with previous work (Dowling et al., 1996; Lucchinetti et al., 1996), which depicted an abundance of DNA fragmentation in oligodendrocytes along the borders of chronic active lesions. Whether these discrepancies relate to the use of differently processed material remains a possibility.

Taken in concert, we have documented for the first time, the widespread expression of DR in MS and non-MS CNS tissue. The same DR were tested on human oligodendrocytes in vitro and were shown to be effective in inducing apoptosis after TRAIL ligation. The incidence of expression of DR in situ failed to correlate with the low degree of apoptosis observed. Whether this indicated a lack of receptor activation, blockade of downstream signaling, or the protective effect of simultaneously expressed decoy receptors, provides subjects for future investigation. Nevertheless, the presence of DR and DcR expression within the CNS supports the existence of innate mechanisms operative during development and disease which influence cell fate. These pathways may play more of a role in the elimination of infiltrating cells (shown here in active MS lesions), rather than the death/survival of parenchymal cells, at least during the chronic stages of this devastating disease.

Acknowledgments

We thank Vina Cruz for assistance with Western blotting; Dr. B. Poulos of the Einstein Tissue Repository, for human fetal CNS tissue; M. Pakingan for technical assistance; and P. Cobban-Bond for administrative support. Dr. C. Petito, University of Miami Brain Bank (HD 83284), and Dr. S. Morgello, Manhattan HIV Brain Bank (MH 59724) provided normal CNS samples.

Supported in part by USPHS grants NS 08952, NS 11920 and NS 07098; NMSS grant RG 1001-K-11; the MS Foundation; and the Wollowick Family Foundation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aktas O, Smorodchenko A, Brocke S, Infante-Duarte C, Topphoff US, Vogt J, Prozorovski T, Meier S, Osmanova V, Pohl E, Bechmann I, Nitsch R, Zipp F. Neuronal damage in autoimmune neuroinflammation mediated by the death ligand TRAIL. Neuron. 2005;46:421–432. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett MH, Henderson AP, Prineas JW. The macrophage in MS: just a scavenger after all? Pathology and pathogenesis of the acute MS lesion. Mult Scler. 2006;12:121–132. doi: 10.1191/135248506ms1304rr. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett MH, Prineas JW. Relapsing and remitting multiple sclerosis: pathology of the newly forming lesion. Ann Neurol. 2004;55:458–468. doi: 10.1002/ana.20016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodmer JL, Burns K, Schneider P, Hofmann K, Steiner V, Thome M, Bornand T, Hahne M, Schroter M, Becker K, Wilson A, French LE, Browning JL, MacDonald HR, Tschopp J. TRAMP, a novel apoptosis-mediating receptor with sequence homology to tumor necrosis factor receptor 1 and Fas(Apo-1/CD95) Immunity. 1997;6:79–88. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80244-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonetti B, Raine CS. Multiple sclerosis: oligodendrocytes display cell death-related molecules in situ but do not undergo apoptosis. Ann Neurol. 1997;42:74–84. doi: 10.1002/ana.410420113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannella B, Raine CS. The adhesion molecule and cytokine profile of multiple sclerosis lesions. Ann Neurol. 1995;37:424–435. doi: 10.1002/ana.410370404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannella B, Raine CS. Multiple sclerosis: cytokine receptors on oligodendrocytes predict innate regulation. Ann Neurol. 2004;55:46–57. doi: 10.1002/ana.10764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degli-Esposti MA, Dougall WC, Smolak PJ, Waugh JY, Smith CA, Goodwin RG. The novel receptor TRAIL-R4 induces NF-kappaB and protects against TRAIL-mediated apoptosis, yet retains an incomplete death domain. Immunity. 1997a;7:813–820. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80399-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degli-Esposti MA, Smolak PJ, Walczak H, Waugh J, Huang CP, DuBose RF, Goodwin RG, Smith CA. Cloning and characterization of TRAIL-R3, a novel member of the emerging TRAIL receptor family. J Exp Med. 1997b;186:1165–1170. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.7.1165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorr J, Bechmann I, Waiczies S, Aktas O, Walczak H, Krammer PH, Nitsch R, Zipp F. Lack of tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand but presence of its receptors in the human brain. J Neurosci. 2002;22(RC209):1–5. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-04-j0001.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowling P, Shang G, Raval S, Menonna J, Cook S, Husar W. Involvement of the CD95 (APO-1/Fas) receptor/ligand system in multiple sclerosis brain. J Exp Med. 1996;184:1513–1518. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.4.1513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Souza SD, Bonetti B, Balasingam V, Cashman NR, Barker PA, Troutt AB, Raine CS, Antel JP. Multiple sclerosis: Fas signaling in oligodendrocyte cell death. J Exp Med. 1996;184:2361–2370. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.6.2361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank S, Kohler U, Schackert G, Schackert HK. Expression of TRAIL and its receptors in human brain tumors. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;257:454–459. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frohman EM, Racke MK, Raine CS. Multiple sclerosis--the plaque and its pathogenesis. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:942–955. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra052130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison DC, Roberts J, Campbell CA, Crook B, Davis R, Deen K, Meakin J, Michalovich D, Price J, Stammers M, Maycox PR. TR3 death receptor expression in the normal and ischaemic brain. Neuroscience. 2000;96:147–160. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(99)00502-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaattela M, Tschopp J. Caspase-independent cell death in T lymphocytes. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:416–423. doi: 10.1038/ni0503-416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurewicz A, Matysiak M, Tybor K, Kilianek L, Raine CS, Selmaj K. Tumour necrosis factor-induced death of adult human oligodendrocytes is mediated by apoptosis inducing factor. Brain. 2005;128:2675–2688. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li JH, Kirkiles-Smith NC, McNiff JM, Pober JS. TRAIL induces apoptosis and inflammatory gene expression in human endothelial cells. J Immunol. 2003;171:1526–1533. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.3.1526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucchinetti C, Bruck W, Parisi J, Scheithauer B, Rodriguez M, Lassmann H. Heterogeneity of multiple sclerosis lesions: implications for the pathogenesis of demyelination. Ann Neurol. 2000;47:707–717. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(200006)47:6<707::aid-ana3>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucchinetti CF, Bruck W, Rodriguez M, Lassmann H. Distinct patterns of multiple sclerosis pathology indicates heterogeneity on pathogenesis. Brain Pathol. 1996;6:259–274. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.1996.tb00854.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matysiak M, Jurewicz A, Jaskolski D, Selmaj K. TRAIL induces death of human oligodendrocytes isolated from adult brain. Brain. 2002;125:2469–2480. doi: 10.1093/brain/awf254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura M, Rieger J, Weller M, Kim J, Kleihues P, Ohgaki H. APO2L/TRAIL expression in human brain tumors. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 2000;99:1–6. doi: 10.1007/pl00007399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nitsch R, Bechmann I, Deisz RA, Haas D, Lehmann TN, Wendling U, Zipp F. Human brain-cell death induced by tumour-necrosis-factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) Lancet. 2000;356:827–828. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02659-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noseworthy J, Miller D, Compston A. Disease-modifying treatments in multiple sclerosis. In: Compston A, editor. McAlpines’s Multiple Sclerosis. Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; Philadelphia, PA: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Omari KM, John GR, Sealfon SC, Raine CS. CXC chemokine receptors on human oligodendrocytes: implications for multiple sclerosis. Brain. 2005;128:1003–1015. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan G, Bauer JH, Haridas V, Wang S, Liu D, Yu G, Vincenz C, Aggarwal BB, Ni J, Dixit VM. Identification and functional characterization of DR6, a novel death domain-containing TNF receptor. FEBS Lett. 1998;431:351–356. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)00791-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan G, O’Rourke K, Chinnaiyan AM, Gentz R, Ebner R, Ni J, Dixit VM. The receptor for the cytotoxic ligand TRAIL. Science. 1997;276:111–113. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5309.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prineas JW, McDonald WI. Demyelinating Diseases. In: Graham DI, Lantos PL, editors. Greenfield’s Neuropathology. I. Arnold; London: 1997. pp. 813–896. [Google Scholar]

- Raine CS. The neuropathology of multiple sclerosis. In: Raine CS, McFarland HF, Tourtellotte WW, editors. Multiple Sclerosis Clinical and pathogenetic basis. Chapman & Hall Medical; London: 1997. pp. 151–171. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider P, Bodmer JL, Thome M, Hofmann K, Holler N, Tschopp J. Characterization of two receptors for TRAIL. FEBS Lett. 1997;416:329–334. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)01231-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selmaj KW, Raine CS. Tumor necrosis factor mediates myelin and oligodendrocyte damage in vitro. Ann Neurol. 1988;23:339–346. doi: 10.1002/ana.410230405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheridan JP, Marsters SA, Pitti RM, Gurney A, Skubatch M, Baldwin D, Ramakrishnan L, Gray CL, Baker K, Wood WI, Goddard AD, Godowski P, Ashkenazi A. Control of TRAIL-induced apoptosis by a family of signaling and decoy receptors. Science. 1997;277:818–821. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5327.818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wajant H. Death receptors. Essays Biochem. 2003;39:53–71. doi: 10.1042/bse0390053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walczak H, Degli-Esposti MA, Johnson RS, Smolak PJ, Waugh JY, Boiani N, Timour MS, Gerhart MJ, Schooley KA, Smith CA, Goodwin RG, Rauch CT. TRAIL-R2: a novel apoptosis-mediating receptor for TRAIL. Embo J. 1997;16:5386–5397. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.17.5386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiley SR, Schooley K, Smolak PJ, Din WS, Huang CP, Nicholl JK, Sutherland GR, Smith TD, Rauch C, Smith CA, et al. Identification and characterization of a new member of the TNF family that induces apoptosis. Immunity. 1995;3:673–682. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90057-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]