Abstract

Transcervical sterilization has moved female sterilization from a minimally invasive laparoscopic technique, which requires entry into the abdominal cavity, to a less invasive hysteroscopic procedure. Along with the decreased potential for complications, its ease of performance with minimal anesthesia has facilitated a move from the operating room to the office. This review compares the available data on transcervical sterilization procedures to better understand the strengths and weakness of each system.

Key words: Transcervical sterilization, Transcervical tubal occlusion, Permanent contraception procedures

In November 2002, Essure® Permanent Birth Control System (Conceptus Inc., San Carlos, CA) was the first method of transcervical sterilization approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use in the United States. Since its introduction, transcervical sterilization has moved female sterilization from a minimally invasive laparoscopic technique, which requires entry into the abdominal cavity, to a less invasive hysteroscopic procedure. Along with the decreased potential for complications, its ease of performance with minimal anesthesia has facilitated a move from the operating room to the office. Now, a second method of transcervical sterilization, Adiana® Permanent Contraception System (Hologic, Inc., Bedford, MA) seems poised for FDA approval and introduction into the US market; Adiana received Conformite Europeenne (CE) marking approval in January 2009. This approval allows the Adiana system to be marketed in the 27 countries of the European Union (EU) and 3 of the 4 member states of the European Free Trade Association (EFTA). With this exciting development on the horizon, this review compares the available data on these transcervical sterilization procedures to better understand the strengths and weakness of each system.

Mechanisms of Action

Essure

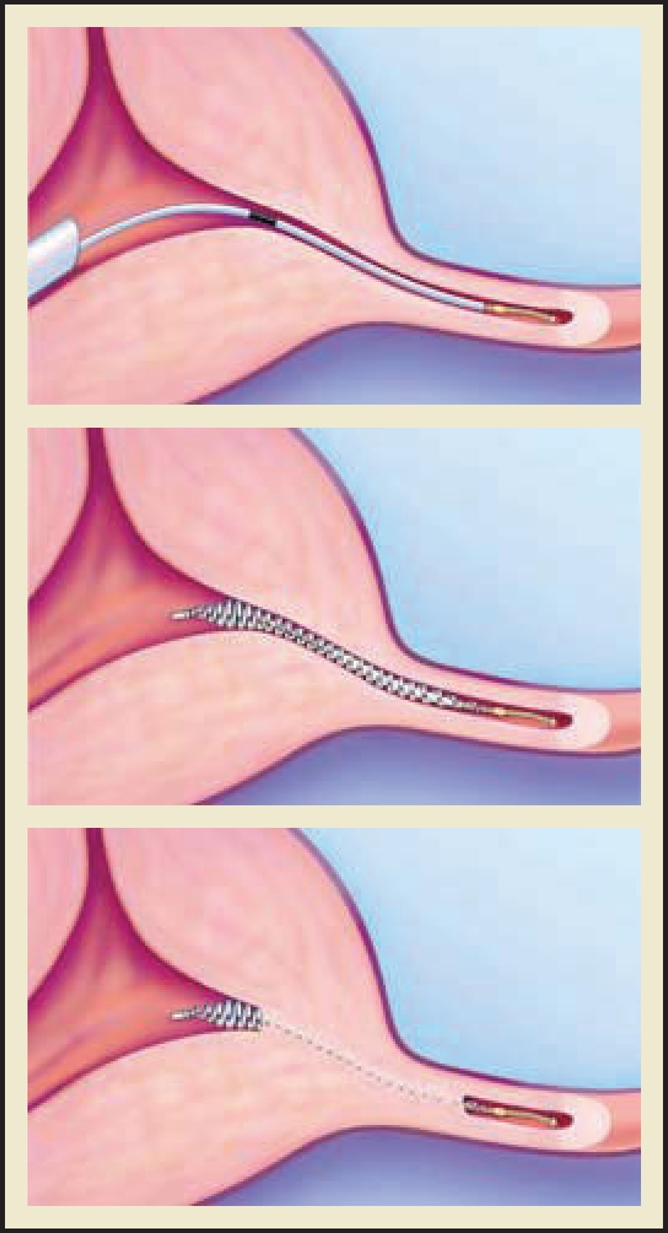

In the Essure procedure, a microinsert is placed into the interstitial portion of each fallopian tube under hysteroscopic guidance. The insert is packaged as a single-use delivery system and consists of an inner coil of stainless steel and polyethylene terephthalate (PET) fibers and an outer coil of nickel-titanium (nitinol). PET fibers were chosen because of their known success in causing tissue ingrowth into medical devices in other procedures, such as arterial grafts. For patients with known nickel sensitivity by skin testing, placement of the device is contraindicated. The device is placed in the proximal fallopian tube in the wound down state and then deployed to an expanded state that anchors the insert along a 3-cm segment of the tube1 (Figure 1). After placement, the PET fibers stimulate a benign tissue response that elicits the invasion of macrophages, fibroblasts, foreign body giant cells, and plasma cells. Within several weeks, the fibrotic ingrowth around the device results in complete tubal occlusion.2 In the United States, tubal occlusion and proper positioning must be confirmed 12 weeks following microinsert placement by hysterosalpingogram (HSG) (Figure 2). Outside the United States, a pelvic x-ray is required at 12 weeks postprocedure to confirm microinsert placement. Backup contraception must be used until proper position and bilateral tubal occlusion are confirmed by HSG. Outside the United States, a pelvic x-ray is required at 12 weeks postprocedure to confirm microinsert placement. Backup contraception must be used until proper position and bilateral tubal occlusion are confirmed by HSG.

Figure 1.

The Essure® Permanent Birth Control System (Conceptus, Inc., Mountain View, CA) procedure for permanent birth control. Copyright 2006 Conceptus Incorporated. All rights reserved.

Figure 2.

Tubal occlusion is confirmed 12 weeks following Essure® Permanent Birth Control System (Conceptus, Inc., Mountain View, CA) microinsert placement by hysterosalpingogram. Copyright Conceptus Incorporated. All rights reserved.

Adiana

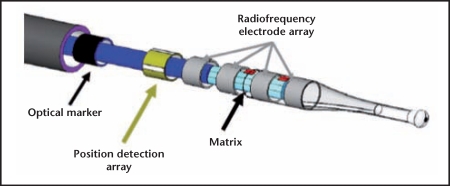

The Adiana sterilization method is a combination of controlled thermal damage to the lining of the fallopian tube followed by insertion of a non-absorbable biocompatible silicone elastomer matrix within the tubal lumen (Figure 3). Under hysteroscopic guidance, a delivery catheter is introduced into the tubal ostium. Once placement inside the intramural section of the fallopian tube is confirmed, the distal tip of the catheter delivers radiofrequency (RF) energy for a period of 1 minute, causing a 5-mm lesion within the fallopian tube. Following thermal injury, the 3.5-mm silicone matrix is deployed within the lesion and the catheter and hysteroscope are removed. Over the next few weeks, occlusion is achieved by fibroblast ingrowth into the matrix, which serves as permanent scaffolding and allows for “space-filling.”3 Occlusion of tubes must be assessed by HSG 3 months after device placement in both the United States and Europe. Although visible via ultrasound, the Adiana matrix is not visible via x-ray or HSG.

Figure 3.

Adiana® Permanent Contraception System (Hologic, Inc., Bedford, MA). Photo courtesy of Hologic, Inc.

Bilateral Placement Rates

Essure

During placement of the Essure coils, the physician is guided by a black band on the Essure delivery catheter. Deployment of the coil when the marker band is aligned with the ostia will typically yield a placement with 3 to 8 coils visible at each ostium. Although 3 to 8 coils are the goal, Essure labeling allows up to 18 coils to be visible at each ostium for an acceptable placement. The number of coils in the uterus can be easily verified hysteroscopically and should be documented at the time of the procedure.

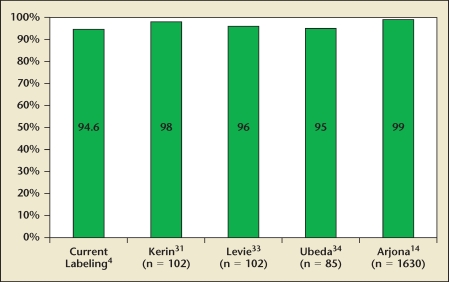

In the current package labeling, Essure’s bilateral placement rate is 94.6%.4 The initial labeling, which was based on the first-generation device and the experience of the pivotal trial investigators, Essure’s reported placement rate was only 86%.5 The 94.6% rate is based on the Essure 205 second-generation model that was commercially available from 2003 through 2007. More recent studies have suggested even higher bilateral placement rates (Figure 4). The main reason for unsuccessful placement was anatomic, with almost half attributable to blocked or stenotic fallopian tubes. The use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents prior to the procedure was associated with increased success rates. Obesity and a history of abdominal surgery were not associated with lower placement rates.1 In late 2007, the company gained approval for the 305 design, which eliminated the need to rotate the device to deploy the matrix. Placement data for the improved 305 design is not yet available.

Figure 4.

Essure® Permanent Birth Control System (Conceptus Inc., San Carlos, CA) bilateral placement rates.

Adiana

Proper deployment of the Adiana matrix is identified by a black marker at the tubal ostia and through a position detection array (PDA). The PDA is a series of 4 sensors that are designed to monitor uniform tissue contact throughout the ablation portion of the procedure. When the catheter is withdrawn after ablation and matrix deployment, no material is left protruding from the ostia into the uterus.

Of the 645 women in the pivotal Evaluation of the Adiana System for Sterilization Using Electrothermal Energy (EASE) trial who had attempted treatment with the Adiana system, 604 (94%) had successful placement bilaterally. After a second procedure, 611 (95%) achieved bilateral placement. Of the remaining 34 women who did not have successful placements, it was felt that the majority of these failures were secondary to distorted patient anatomy (eg, tubal blockage, lateral tubal ostia, uterine adhesions).6,7 No information is available regarding body mass indices or surgical histories of study participants. Placement rates may be unaffected by these factors, as with Essure, but these data are not yet available.7

Efficacy

Essure

Combined data from the phase II and pivotal trials demonstrate no pregnancies in 643 study participants who contributed 29,357 women-months of follow-up, with an average surveillance time of 52.9 and 42.5 months, respectively.1,8,9 Although no pregnancies have been reported following documented bilateral tubal occlusion in these trials, Kerin10 analyzed 37 pregnancies reported to the manufacturer, worldwide, from 1997 through 2004. Six (16%) of these women were pregnant prior to device placement; 7 (19%) were secondary to misinterpreted HSGs, and the majority, 21 (57%), were attributable to inadequate post-procedure follow-up. It was concluded that most pregnancies can be avoided by performing the procedure in the proliferative phase; using reliable contraception until tubal occlusion can be confirmed by HSG; and adhering to the HSG protocol with accurate reporting of the HSGs.9 Levy and colleagues10 subsequently reviewed 64 pregnancies out of an estimated 50,000 procedures that were reported to the device manufacturer through December 2005. Most occurred in patients without appropriate follow-up; other causes included misread HSGs, undetected preprocedure pregnancies, and failure to follow product-labeling guidelines. A breakdown of these pregnancies is detailed in Table 1. Almost half of all cases were related to patient or physician noncompliance issues. A comparison of these data to the US Collaborative Review of Sterilization (CREST) study shows that transcervical tubal occlusion is second only to unipolar tubal ligation in terms of effectiveness (Table 2).11 Furthermore, when all reported pregnancies with a confirmatory HSG are analyzed,13 hysteroscopic tubal occlusion with Essure represents the most effective of all female or male sterilization techniques at the observed follow-up times. No pregnancies were due to method failure.

Table 1.

Causes of Reported Pregnancies

| Reason Pregnancy Occurred | N | % of Total |

| Patient or physician noncompliance | 30 | 47 |

| Misread radiograph or HSG | 18 | 28 |

| Pregnant at time of placement | 8 | 12.5 |

| Prior device design | 1 | 1.5 |

| Other | 7 | 11 |

| Total | 64 |

HSG, hysterosalpingogram.

Reprinted from Journal of Minimally Invasive Gynecology, Vol. 14, Levy B et al, A summary of reported pregnancies after hysteroscopic sterilization, pp. 271–274, Copyright 2007, with permission from Elsevier.10

Table 2.

Percentage of US Women Experiencing an Unintended Pregnancy During the First Year of Typical Use and the First Year of Perfect Use of Contraception and the Percentage Continuing Use at the End of the First Year

| Women Experiencing an Unintended Pregnancy Within the First Year of Use (%) | |||

| Method | Typical Use | Perfect Use | Women Continuing Use at 1 Year (%) |

| No method | 85 | 85 | |

| Spermicides | 29 | 18 | 42 |

| Withdrawal | 27 | 4 | 43 |

| Periodic abstinence | 25 | 51 | |

| Calendar | 9 | ||

| Ovulation method | 3 | ||

| Symptothermal | 2 | ||

| Postovulation | 1 | ||

| Cap | |||

| Parous women | 32 | 26 | 46 |

| Nulliparous women | 16 | 9 | 57 |

| Sponge | |||

| Parous women | 32 | 20 | 46 |

| Nulliparous women | 16 | 9 | 57 |

| Diaphragm | 16 | 6 | 57 |

| Condom | |||

| Female (Reality) | 21 | 5 | 49 |

| Male | 15 | 2 | 53 |

| Combined pill and minipill | 8 | 0.3 | 68 |

| Ortho Evra® patch | 8 | 0.3 | 68 |

| NuvaRing® | 8 | 0.3 | 68 |

| Depo-Provera® | 3 | 0.3 | 56 |

| Lunelle™ | 3 | 0.05 | 56 |

| IUD | |||

| ParaGard® (copper T) | 0.8 | 0.6 | 78 |

| Mirena® (levonorgesterel-releasing intrauterine system) | 0.1 | 0.1 | 81 |

| Norplant® and Norplant-2® | 0.05 | 0.05 | 84 |

| Female sterilization | 0.5 | 0.5 | 100 |

| Male sterilization | 0.15 | 0.10 | 100 |

Reality, Female Health Company, UK; Ortho Evra, Ortho-McNeil-Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Raritan, NJ; NuvaRing, Organon USA Inc., Roseland, NJ; Depo-Provera, Pfizer Inc, New York, NY; Lunelle, Pharmacia Corporation, Peapack, NJ; ParaGard, Duramed Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Pomona, NY; Mirena, Bayer Healthcare Pharmaceuticals, Montville, NJ; Norplant and Norplant-2, Wyeth Pharmaceuticals Inc., Philadelphia, PA.

Reprinted from Contraception, Vol. 70, Trussel J, Contraceptive failure in the United States, pp. 89–96, Copyright 2004, with permission from Elsevier.

Adiana

Data from the EASE trial were presented to the Obstetrics and Gynecology Devices Panel of the Medical Devices Advisory Committee for the FDA in December 2007.3 In this study, the primary endpoint was to demonstrate the effectiveness of the Adiana system. In this trial, 570 women had documented tubal occlusion by HSG. During the first year of follow-up, 6 pregnancies were reported, with half attributed to true method failure and the remainder from physician error (misinterpretation of HSG results). The second year yielded 3 additional pregnancies believed to be the result of method failure. There were no pregnancies reported in the third year and 1 additional pregnancy reported in a patient at 42 months postplacement. The cumulative failure rates were 1.08% at 1 year and 1.82% at 2 years.6 These effectiveness data are within the range of all sterilization methods evaluated by the CREST study at similar time intervals; however, the Adiana failure rate is higher than all methods evaluated in the study, except for the spring clip application.12

Procedural Discomfort and Patient Satisfaction

Essure

Compared with laparoscopic tubal ligation (LTL), significant patient advantages can be achieved when the Essure procedure is performed in the office with local anesthesia rather than in the operating room. In addition to the convenience of this setting and the elimination of the recovery time from the anesthetic agents, several authors have reported favorable pain profiles and satisfaction data with this technique. In a study from Spain on 1615 patients undergoing placement of Essure with only oral ibuprofen and an oral benzodiazepine, Arjona and colleagues14 reported that “1,398 (86.5%) of the 1,615 women with Essure microinserts inserted considered it excellent or very good, 10.2% (166) felt pain similar to normal menstruation (good), and only 3.1% felt more pain than with menstruation (fair or poor).” These data were underscored by a French study of 1032 women undergoing the Essure procedure in which 90% reported a return to their everyday life within 24 hours and 80% of the local anesthesia patients reported returning to work the next day.15 Finally, in a direct comparison against LTL in a prospective cohort trial of 89 women, Duffy and colleagues showed that 82% of the Essure patients considered their tolerance of the procedure to be “excellent to good” as opposed to only 41% of the LTL patients. At 90 days, 100% of the Essure patients were satisfied with recovery as compared with only 80% of the LTL subjects.16

Adiana

In the EASE clinical trial, 53% of patients underwent the procedure without IV sedation. Based on the data from the EASE trial, 98% of the 645 subjects who underwent the Adiana procedure reported that they tolerated it “well” to “excellent.” Vancallie and colleagues6 reported that 40.2% of patients reported little or no discomfort associated with the procedure and 9.2% described it as “very uncomfortable.” Cramping was reported by 25% of participants during the procedure, but only 2% complained of postprocedural pain. The majority of patients were able to resume normal activity within a day of the procedure and, after 1 week, over 99% described their comfort as “good” to “excellent.”17 No studies have yet been published specifically on Adiana in the office setting with local anesthesia.

Safety

Essure

There were no major adverse events (death, bowel injury, or major vascular injury) reported in the phase II and pivotal trial data obtained from 745 women undergoing placement of Essure between 1998 and 2001, although perforation was noted in 2.8% of the patients.11 Similarly, Chern and Siow did not encounter any significant safety concerns in their review of 80 patients who underwent the Essure procedure in Singapore.18 A review of the FDA’s MAUDE database from the introduction of Essure in 2002 to April 2009 also did not reveal any major adverse events, but there were 3 reports of devices embedding into abdominal structures and requiring removal after procedures complicated by uterine perforation.19 Although extremely rare, unrelieved postprocedure pain has also been reported even with correct placement of the devices, with improvement in symptoms following removal.20 Successful laparoscopic and hysteroscopic removal of Essure microinserts have been reported as a minimally invasive approach to managing such complications, although it should be emphasized that the technique is considered irreversible.20–22

Connor published a comprehensive review of Essure using data collected from the MAUDE database from January 2004 through January 2009.23 Five pregnancies, including 4 ectopic pregnancies, were reported, all within 1 year of placement. Within the ectopic pregnancy group, 1 patient conceived within 3 months without back-up contraception. Two pregnancies occurred 1 year after the procedure. Review of the HSG in one of these patients showed incorrect proximal placement, whereas there was no information on the other HSG. The fourth patient did not comply with the HSG requirement and had an ectopic pregnancy 4 months after the procedure.

There are no adverse events related to the use of magnetic resonance imaging.24 Finally, for women with significant medical problems (such as severe cardiac disease) who require permanent contraception but might otherwise carry considerable surgical risks, Essure has been shown to be a safe alternative to tubal ligation.25

Adiana

The Adiana system has a good safety profile based on the 12-month data from the EASE trial. Of the 645 procedures performed in this study, the only notable significant complication on the day of the procedure was a case of hyponatremia, which was treated with a single dose of a diuretic without further sequelae. Although the details of this case are not explained, the presumed cause is excessive absorption of the glycine that was used as the distention medium. The mean volume of glycine absorbed during the study was 182 mL, but the volume absorbed in the subject with hyponatremia was not reported. Given the minimal average absorption and lack of open venous channels created during the procedure, it is not expected that hyponatremia should be a significant risk. However, as more data emerge, the safety of the Adiana system should be further clarified, especially with respect to the use of glycine.

Two ectopic pregnancies were reported and treated with methotrexate. There were no reports of uterine or tubal perforations or adverse events related to application of RF energy or matrix placement. There were no reports of persistent postprocedural pain requiring surgical management.26 There are no known contraindications based on allergies to components of the Adiana system.

Cost and Equipment

Essure

The outpatient office-based nature of transcervical female sterilization with Essure gives this method a very favorable cost profile as compared with other methods. In a 2005 study of female sterilization techniques, Levie and Chudnoff demonstrated significant cost savings with transcervical female sterilization when compared with LTL as long as the transcervical procedure was performed in the office setting, despite the relatively high cost of the device.27 Similarly, Hopkins and colleagues demonstrated a significant cost savings of $180 per patient when in-office hysteroscopic sterilization was compared with tubal ligation with electrosurgery.28 Echoing these finding, Thiel and Carson also demonstrated significant cost savings with Essure as compared with LTL and added, “[c]arrying out the Essure procedure in an ambulatory setting frees space in the operating room for other types of cases, improving access to care for more patients.”29

Adiana

The costs associated with Adiana are as yet unknown. Although there will be costs associated with the device itself, the RF generator, a reusable connector cable, and possibly a fluid management system, the presumed in-office location of the procedure should yield a favorable cost profile relative to LTL. Taking into consideration the cost related to the initial purchase and upkeep of the required equipment, it appears that Adiana will be similarly or slightly less economically efficient than Essure.

Patient Counseling and Follow-Up

The effectiveness data previously discussed for both technologies are based on proper placement and confirmation of tubal occlusion. These endpoints should be evaluated in 3 stages: (1) confirming proper device placement during the procedure, (2) confirming tubal occlusion at 90 days, and (3) understanding the risk of pregnancy for women who do not follow-up.

Essure

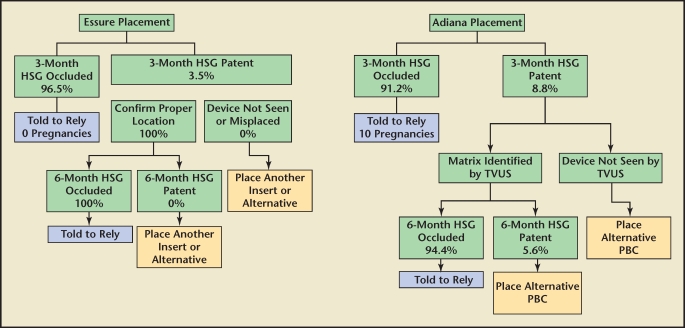

Several studies have reported patient follow-up rates for Essure between 13% and 95%.30,31 This wide variability appears to be due to both patient demographics and level of physician diligence when counseling the patient on the importance of the confirmation test (HSG). The patient should be extensively counseled that this confirmatory test is required at 90 days postprocedure to document both device location and bilateral tubal occlusion before the product is used as the primary method of contraception. Identifying the location of the device is important because it mitigates the risk of temporary occlusion from tubal spasm during the HSG, which can be as high as 30%,32 and provides a clear treatment protocol in the rare case of persistent tubal patency. In the Essure clinical trials, 96% of patients had bilateral occlusion at 3 months.5 The 3.5% of patients with a patent tube with the Essure device in place were told to wait an additional 3 months for a subsequent confirmation test. All patients in this group had bilateral occlusion at 6 months. The reliance rate for Essure is 96.8% (percentage of patients with bilateral placement that are able to rely on the device for birth control). Visualizing the device on HSG is an important component of the treatment algorithm because of the possibility of device misplacement or expulsion with subsequent tubal patency necessitating placement of a second device (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Comparison of treatment algorithms: Essure® Permanent Birth Control System (Conceptus Inc., San Carlos, CA) and Adiana® Permanent Contraception System (Hologic, Inc., Bedford, MA). Percentages based on US Food and Drug Administration pivotal trials. HSG, hysterosalpingogram; PBC, permanent birth control; TVUS, transvaginal ultrasound.

Adiana

During the EASE trial, an HSG was required after 3 months. Because the matrix is not radiopaque, only tubal occlusion can be verified. If both tubes appear occluded by HSG, patients are told to rely on this method for contraception. In the EASE trial, 8.8% of patients had 1 or more patent tubes at 3 months and 6 pregnancies (including 1 ectopic) occurred in the first 12-month evaluation of the device following a HSG documenting bilateral tubal occlusion. Fifty percent of these pregnancies were determined to be caused by HSG misinterpretation.3

In the 11 patients with a patent tube in the EASE trial, the recommended protocol was to perform a transvaginal ultrasound to identify the device location. If it appeared to be in the proper place, the patient was told to wait another 3 months for a subsequent HSG. Of those patients, only 36% of tubes became occluded. After 6 months, 94.4% of patients with confirmed placement had bilateral tubal occlusion.3 The overall reliance rate for Adiana in the EASE trial was 93.2% (percentage of women with bilateral placement that were able to rely on the device for birth control).

Procedural success with the Adiana device will be determined by the clinician’s ability to adhere to the proper technique during the ablation, matrix deployment, and the follow-up HSG. The need for strict patient compliance with the follow-up HSG will need to be reinforced, and the HSG will need to be accurately interpreted.

Summary

Transcervical tubal sterilization has expanded the repertoire of permanent contraceptive options for women. In addition, as compared with incisional methods of sterilization, the risks are markedly reduced. The Essure procedure has been offered to women in the United States for 7 years and has proved to be well tolerated, safe, and effective. To date, there are approximately 200 publications in the literature on the Essure system, thus adding to the body of knowledge regarding this technique. The experience with the Adiana system is limited, with only 12-month data on the device. However, the data from the pivotal trial provide important clinical information. As with Essure, the Adiana system appears to be well tolerated with low rates of adverse events, although more data is clearly needed. The overall bilateral placement rates for both systems are about the same (94%–95%) and the rates of tubal occlusion after HSG are comparable. The most important difference between the systems to date appears to be their efficacy based on clinical studies. There have been no reported pregnancies after Essure from the phase II and pivotal trials. Data from the EASE study suggests that, although the Adiana system is over 98% effective, the 2-year cumulative failure rate is 1.82%, which is higher than for all forms of sterilization reported in the CREST study, except for the spring clip application (2.38%), for the same time interval.6

Main Points.

Transcervical sterilization has moved female sterilization from a minimally invasive laparoscopic technique, which requires entry into the abdominal cavity, to a less invasive hysteroscopic procedure. Along with the decreased potential for complications, its ease of performance with minimal anesthesia has facilitated a move from the operating room to the office.

In the Essure procedure, a microinsert is placed into the interstitial portion of each fallopian tube under hysteroscopic guidance. Benign tissue ingrowth around the device results in complete tubal occlusion. The Adiana sterilization method is a combination of controlled thermal damage to the lining of the fallopian tube followed by insertion of a nonabsorbable biocompatible silicone elastomer matrix within the tubal lumen. Occlusion is achieved by fibroblast ingrowth into the matrix.

Essure’s bilateral placement rate is 94.6%. Adiana’s bilateral placement rate is 94%; after a second procedure 95% achieve bilateral placement.

Hysteroscopic tubal occlusion with Essure represents the most effective of all female or male sterilization techniques, whereas the Adiana failure rate is higher than all methods except for spring clip ligation.

Both Essure and Adiana reduced procedural discomfort and increased patient satisfaction when compared with laparoscopic tubal ligation.

The outpatient office-based nature of transcervical female sterilization with Essure gives this method a very favorable cost profile as compared with other methods. Taking into consideration the cost related to the initial purchase and upkeep of the required equipment, it appears that Adiana will be similarly or slightly less economically efficient than Essure.

Both systems are well tolerated with low rates of adverse events.

The effectiveness data for both technologies are based on proper placement and confirmation of tubal occlusion. These endpoints should be evaluated in 3 stages: (1) confirming proper device placement during the procedure, (2) confirming tubal occlusion at 90 days, and (3) understanding the risk of pregnancy for women who do not follow-up.

References

- 1.Cooper JM, Carignan CS, Cher D, et al. Microinsert nonincisional hysteroscopic sterilization. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102:59–67. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(03)00373-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Valle RF, Carigan CS, Wright TC, et al. Tissue response to the STOP microcoil transcervical permanent contraceptive device: results from a prehysterectomy study. Fertil Steril. 2001;76:974–980. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(01)02858-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. [Accessed July 29, 2008];Adiana Transcervical Sterilization System PMA P070022 Panel Package. :13–15. US Food and Drug Administration Obstetrics and Gynecology Devices Panel Web site. http://www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/ac/07/briefing/2007-4334b1-00-index.html. Updated December 11, 2007.

- 4.Essure [package insert] San Carlos, CA: Conceptus Incorporated; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kerin JF, Carignan CS, Cher D. The safety and effectiveness of a new hysteroscopic method for permanent birth control: results of the first Essure pbc clinical study. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2001;41:364–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828x.2001.tb01311.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vancaillie TG, Anderson TL, Johns DA. A 12-month prospective evaluation of transcervical sterilization using implantable polymer matrices. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112:1270–1277. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31818d8bda. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kerin JF. Hysteroscopic sterilization: long-term safety and efficacy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2005;12(suppl):40. Abstract 98. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kerin JF, Cooper JM, Price T, et al. Hysteroscopic sterilization using a micro-insert device: results of a multicentre phase II study. Hum Reprod. 2003;18:1223–1230. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deg256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kerin JF. Pregnancies in women who have the Essure hysteroscopic sterilization procedure: a summary of 37 cases. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2005;12(suppl):28. Abstract 67. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Levy B, Levie MD, Childers ME. A summary of reported pregnancies after hysteroscopic sterilization. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2007;14:271–274. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2006.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peterson HB, Xia Z, Hughes JM, et al. The risk of pregnancy after tubal sterilization: findings from the U.S. Collaborative Review of Sterilization. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;174:1161–1170. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(96)70658-0. discussion 1168–1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ory EM, Hines RS, Cleland WH, Rehberg JF. Pregnancy after microinsert sterilization with tubal occlusion confirmed by hysterosalpingogram. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111:508–510. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000296487.36158.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. [Accessed July 29, 2008];Adiana Transcervical Sterilization System PMA P070022 Panel Package. :47–48. US Food and Drug Administration Obstetrics and Gynecology Devices Panel Web site. http://www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/ac/07/briefing/2007-4334b1-00-index.html. Updated December 11, 2007.

- 14.Arjona JE, Miño M, Cordón J, et al. Satisfaction and tolerance with office hysteroscopic tubal sterilization. Fertil Steril. 2008;90:1182–1186. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scarabin C, Dhainaut C. The ESTHYME study. Women’s satisfaction after hysteroscopic sterilization (Essure micro-insert). A retrospective multicenter survey [in French] Gynecol Obstet Fertil. 2007;35:1123–1128. doi: 10.1016/j.gyobfe.2007.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Duffy S, Marsh F, Rogerson L, et al. Female sterilisation: a cohort controlled comparative study of ESSURE versus laparoscopic sterilisation. BJOG. 2005;112:1522–1528. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2005.00726.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. [Accessed July 29, 2008];Adiana Transcervical Sterilization System PMA P070022 Panel Package. US Food and Drug Administration Obstetrics and Gynecology Devices Panel Web site. http://www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/ac/07/briefing/2007-4334b1-00-index.html. Updated December 11, 2007.

- 18.Chern B, Siow A. Initial Asian experience in hysteroscopic sterilisation using the Essure permanent birth control device. BJOG. 2005;112:1322–1327. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2005.00436.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. [Accessed April 22, 2009];MAUDE Database. US Food and Drug Administration Center for Devices and Radiological Health Web site. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfMAUDE/search.CFM.

- 20.Hur HC, Mansuria SM, Chen BA, Lee TT. Laparoscopic management of hysteroscopic Essure sterilization complications: report of 3 cases. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2008;15:362–365. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2007.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang LC. Successful laparoscopic removal of Essure micro-inserts for persistent post-procedureal pain. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2007;14(suppl):S154. Abstract 465. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lannon BM, Lee SY. Techniques for removal of the Essure hysteroscopic tubal occlusion device. Fertil Steril. 2007;88:e13–e14. 497. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.11.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Connor VF. Essure: a review six years later. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2009;16:282–290. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2009.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. [Accessed May 6, 2009];Frequently asked questions. Essure Permanent Birth Control Web site. http://www.essuremd.com/Home/bTheEssureProcedureb/bFAQsb/tabid/59/Default.aspx.

- 25.Famuyide AO, Hopkins MR, El-Nashar SA, et al. Hysteroscopic sterilization in women with severe cardiac disease: experience at a tertiary center. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83:431–438. doi: 10.4065/83.4.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. [Accessed April 22, 2009];Adiana Transcervical Sterilization System PMA P070022 Panel Package. :47–51. US Food and Drug Administration Obstetrics and Gynecology Devices Panel Web site. http://www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/ac/07/briefing/2007-4334b1-00-index.html. Updated December 11, 2007.

- 27.Levie MD, Chudnoff SG. Office hysteroscopic sterilization compared with laparoscopic sterilization: a critical cost analysis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2005;12:318–322. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2005.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hopkins MR, Creedon DJ, Wagie AE, et al. Retrospective cost analysis comparing Essure hysteroscopic sterilization and laparoscopic bilateral tubal coagulation. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2007;14:97–102. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2006.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thiel JA, Carson GD. Cost-effectiveness analysis comparing the Essure tubal sterilization procedure and laparoscopic tubal sterilization. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2008;30:581–585. doi: 10.1016/S1701-2163(16)32891-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shavell VI, Abdallah ME, Diamond MP, et al. Post-Essure hysterosalpingography compliance in a clinic population. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2008;15:431–434. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2008.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kerin JF, Munday DN, Ritossa MG, et al. Essure hysteroscopic sterilization: results based on utilizing a new coil catheter delivery system. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2004;11:388–393. doi: 10.1016/s1074-3804(05)60056-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Anandakumar C, Rauff M, Wong E, et al. Hysterosalpingography: 1. The incidence of tubal spasm during hysterosalpingography. Asia Oceania J Obstet Gynaecol. 1985;11:209–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.1985.tb00735.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Levie MD, Chudnoff SG. Prospective analysis of office-based hysteroscopic sterilization. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2006;13:98–101. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2005.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ubeda A, Labastida R, Dexeus S. Essure: a new device for hysteroscopic tubal sterilization in an outpatient setting. Fertil Steril. 2004;82:196–199. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2003.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]