Abstract

Alternative splicing yields functionally distinctive gene products, and their balance plays critical roles in cell differentiation and development. We have previously shown that tumor-associated enhancer loss in coactivator gene CoAA leads to its altered alternative splicing. Here we identified two intergenic splicing variants, a zinc finger-containing coactivator CoAZ and a non-coding transcript ncCoAZ, between CoAA and its downstream corepressor gene RBM4. During stem/progenitor cell neural differentiation, we found that the switched alternative splicing and trans-splicing between CoAA and RBM4 transcripts result in lineage-specific expression of wild type CoAA, RBM4, and their variants. Stable expression of CoAA, RBM4, or their variants prevents the switch and disrupts the embryoid body formation. In addition, CoAA and RBM4 counter-regulate the target gene Tau at exon 10, and their splicing activities are subjected to the control by each splice variant. Further phylogenetic analysis showed that mammalian CoAA and RBM4 genes share common ancestry with the Drosophila melanogaster gene Lark, which is known to regulate early development and circadian rhythms. Thus, the trans-splicing between CoAA and RBM4 transcripts may represent a required regulation preserved during evolution. Our results demonstrate that a linked splicing control of transcriptional coactivator and corepressor is involved in stem/progenitor cell differentiation. The alternative splicing imbalance of CoAA and RBM4, because of loss of their common enhancer in cancer, may deregulate stem/progenitor cell differentiation.

From the initial discovery of RNA splicing (1, 2) to recent advanced genomic studies (3), a large body of evidence suggests that alternative splicing as an integral part of gene regulation profoundly impacts biological and pathological functions (4). In the human genome, although ∼20,000 protein-coding genes exist, more than 90% of multi-exon genes are alternatively spliced (3, 5, 6). Thus, alternative pre-mRNA splicing contributes greatly to proteome diversity without increasing the number of genes (7, 8). Alternative splicing can be cell- and tissue-specific, which is particularly important at the early developmental stages (9). The wild type and variant proteins often exert overlapping but distinct functions whose balance is controlled by the choice of alternative splicing. Aberrant splicing patterns may disrupt the normal functional balance of isoforms, which in turn impairs cell differentiation and induces disease or cancer (10, 11).

Pre-mRNA splicing is a process of joining exons and splicing out introns. In addition to constitutive splicing events, exons can be alternatively spliced. This includes exon skipping, alternative 5′ and 3′ splicing, mutually exclusive exons, intron retention, and alternative transcription start or stop sites (12). The cis-splicing mechanism involves splicing within one pre-mRNA molecule. In contrast, significant evidence supports that trans-splicing can occur at a much lower frequency by joining exons from two independent pre-mRNA molecules through the usage of canonical splicing sites in the absence of DNA recombination (13). Many examples of trans-splicing have been described (14). However, the biological functions of a large amount of trans-splicing events remain to be characterized. Among the products of some alternative splicing and trans-splicing are non-coding RNAs (15, 16). Although non-coding RNAs do not encode a protein product, many of them play important regulatory roles at multiple levels of RNA metabolism. Evidence has also suggested that the majority of the mammalian genome is transcribed into non-coding RNAs, many of which are alternatively spliced products.

Altered splicing patterns are prevalent in diseases and cancers. It has been shown that germ-line sequence variations at splice sites are present in cancer genes such as BRCA1 and APC (17–19). Differentially expressed alternative splice variants are associated with severe clinical outcome in cancer patients (20). Faulty alternative splicing signals impair apoptosis pathways. The high relevance between alternative splicing and cancer is a reflection of the fundamental role of alternative splicing in controlling stem cell or progenitor cell differentiation, as cancer is considered a stem cell disease. Recent studies on human embryonic stem cells and neural progenitor cells indicate that a large amount of alternative splicing events normally occur (21). In addition, splicing of a number of exons has been shown to be reprogrammed due to the switch of alternative splicing regulators during neural development (22). Thus, alternative splicing control may play a key role in stem cell and progenitor cell differentiation.

Alternative splicing is coupled with transcriptional regulation which is in part regulated by transcriptional coactivators and corepressors (23, 24). We have previously characterized coactivator CoAA2 (gene symbol RBM14) in regulating transcription-coupled pre-mRNA alternative splicing (23, 25, 26). The CoAA pre-mRNA is alternatively spliced to yield several alternative splicing variants, one of which is a functional dominant negative variant termed CoAM. In stem cells, CoAA and CoAM regulate early stem cell differentiation through a switch of their alternative splicing at the stage of embryoid body cavitation (27). In human cancers the CoAA gene is amplified with the recurrent deletion of its 5′ upstream regulatory sequence (28). We have shown that deletion of this regulatory sequence leads to defective switching between CoAA and CoAM (27).

In this study we describe the trans-splicing events between CoAA and its downstream RBM4 genes, both of which encode transcription and alternative splicing coregulators that participate in neural stem cell or progenitor cell differentiation. The human RBM4 gene is ∼10 kilobases distal to CoAA at chromosome 11q13. RBM4 protein has been previously shown to regulate alternative splicing of the microtubule-associated protein Tau at its exon 10 (29) and to antagonize polypyrimidine tract-binding protein alternative splicing activities (30, 31). RBM4 is a mammalian ortholog of the Drosophila melanogaster Lark, which is critical for viability, fertility, development, and circadian rhythms output (32–34). We found that RBM4 represses nuclear receptor-mediated transcription. The CoAA and RBM4 gene transcripts are trans-spliced to produce a novel zinc finger-containing coactivator CoAZ and a non-coding splice variant ncCoAZ. CoAZ and ncCoAZ are derived by 5′ competitive alternative splicing and display switched expression patterns during neural stem cell differentiation. Both CoAZ and ncCoAZ activate transcription and balance coactivator CoAA and corepressor RBM4 splicing activities. In particular, CoAA and CoAZ promote the skipping of Tau exon 10, and RBM4 and ncCoAZ promote the inclusion of Tau exon 10. The imbalance of Tau alternative splicing at its exon 10 is known to be involved in neurodegenerative diseases (35). Thus, the regulation of coactivator CoAA and corepressor RBM4 through alternative trans-splicing variants may have functional importance in normal cell differentiation as well as disease.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cloning of CoAZ and ncCoAZ

Total RNA from HeLa cells was isolated using Trizol reagent, treated with DNase I, and converted to cDNA using first-strand cDNA synthesis kit (Invitrogen). The presence of CoAZ and ncCoAZ was initially detected by RT-PCR followed by sequence analysis. Full-length cDNAs were subsequently obtained by 3′ and 5′-RACE (Invitrogen). As controls, the absence of CoAA transcript in 5′-RACE and the absence of RBM4 transcript in 3′-RACE were confirmed using CoAA or RBM4-specific primers. Primers crossing splicing junctions were used in RACE to ensure specificity. The 5′ and 3′ ends of CoAZ and ncCoAZ transcripts were subjected to sequence analysis. The primers for 5′-RACE were: CoAZ primers, GSP1, tctatcggacactctttg; GSP2, acgtgcattcgtttgcctttca; GSP3, tgtgcacgaaggcgaactgtt; ncCoAZ-specific, ttgcaactctgtgttatc; The primers for 3′-RACE primers were: CoAZ primers, GSP1, gattcagaattcaagatattcgtgggcaa; GSP2, tgacgtggtga-aaggcaa; GSP3, ctggtccaaagagtgtccgataga; ncCoAZ-specific, gataacacagagttgcaa. Identified cDNAs sequences have been deposited in GenBank with accession numbers as follows: human CoAZ, EU287938; human ncCoAZ, EU287939; mouse CoAZ, EU287940; mouse ncCoAZ, EU287941.

Construction of RBM4 Minigenes and trans-Splicing Assays

The CoAA minigenes with alternative splicing capacity have been previously described (27). To facilitate trans-splicing analysis, RBM4 minigenes were constructed under the control of CMV or its native RBM4 promoter (from −1113 to +1) as diagrammed in Fig. 2A. The RBM4 minigenes contain four intact exons, nucleotides 1–71, 1019–1442, 4769–5459, and 7346–7787. Deletions were introduced to the first intron (519–813), the second intron (1623–4558), and the third intron (5728–7065). A minimum 160-bp intronic sequence around each splicing site was left intact to preserve necessary binding sites for splicing factors. A SpeI restriction enzyme recognition site was introduced into the third exon of RBM4 (5125–5131) to distinguish minigene transcripts from the endogenous. The splicing capacity of RBM4 minigene cassettes was evaluated by RT-PCR. The spliced transcripts were gel-purified (Qiagen) and SpeI-digested (New England Biolabs). In trans-splicing assays, 293 cells were cotransfected with both CoAA and RBM4 minigenes using vector as controls. RT-PCR analyses using primers spanning the CoAA first exon and the RBM4 third exon were performed. Primers used gattcagaattcaagatattcgtgggcaa and ctcaagctttaaaaggctgagtacc. PCR products corresponding to the correct size of CoAZ and ncCoAZ were gel-purified and SpeI-digested before gel analysis.

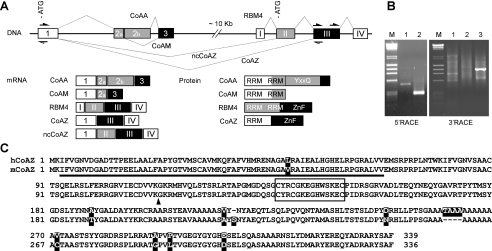

FIGURE 2.

CoAZ and ncCoAZ are trans-splicing products of CoAA and RBM4 genes. A, CoAA and RBM4 minigenes with shortened intron sequences were constructed in individual plasmids under the control of either CMV or their native promoter. A SpeI restriction site was inserted into the third exon of RBM4 to distinguish minigene products from the endogenous transcripts. Digested PCR fragments and introns are depicted as lines with the number of base pairs indicated. B, 293 cells were transfected with vector alone or RBM4 minigenes (200 ng) with either CMV or RBM4 promoter as indicated. The RBM4 minigenes were analyzed for individual intron splicing capacity by RT-PCR. Gel-purified spliced transcripts (open arrow) were SpeI digested (filled arrows). Unspliced intron-containing transcripts are indicated by asterisks. Numbers indicate nucleotide base pairs. Each PCR reaction labeled by circled numbers was depicted in A. C, 293 cells were cotransfected with CoAA (100 ng) and RBM4 (100 ng) minigenes with either CMV or their native promoters as indicated. RT-PCR analyses depicted in A were followed by SpeI digestion using gel-purified PCR products for both CoAZ and ncCoAZ. The presence of digested fragments (filled arrows) indicates the trans-splicing events of the minigenes. Non-digestible fragments (open arrows) were derived from endogenous transcripts.

RT-PCR and Quantitative Real-time PCR Analyses

Endogenous CoAZ, ncCoAZ, and RBM4 mRNA expression patterns were analyzed using first-strand cDNAs from multiple normal human tissues and cancer cell lines (MTCTM panels, Clontech). For P19 cells, total RNA was isolated at each differentiation stage using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen), treated with DNase I, and normalized for their concentrations before use. RNA was reverse-transcribed to cDNA using SuperScript III first-strand synthesis system (Invitrogen). Real-time PCR (iCycler, Bio-Rad) was performed using SYBR Green dye in duplicate in a 25-μl reaction. The results were normalized to GAPDH. Primer pairs used were as follows: primers common to endogenous CoAA and CoAM, atgaagatttttgtgggcaa, ctaaacgccggtcg-gaacc; CoAM-specific, tctcaaccaagggtatggtt, ctac-atgcggcgctggta; ncCoAZ, atcgagtgtgacgtggtaaaag, aagctttgctcttattcttgctg; CoAZ, tgacgtggtaaaaggcaa, atctattggacactctttggac; RBM4, gccattttagcgttttgtc-ag, atctattggacactctttggac; total Tau, ccaccaaaatccggagaacgaa, gcttgtgatggatgttccctaa; Tau exon 10, gtgcagataattaataagaagctg, gcttgtgatggatgttccctaa; Nanog, agggtctgctactgagatgctctg, caaccactggtttttctgccaccg; MAP2, ggacatcagcctcactcacaga, gcagcatgttcaaagtcttcacc; Sox6, cagcggatggagaggaagcaatg, ctttttctgttcatcatgggctgc; glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), gaatgactcctccactccctgc, cgctgtgaggtctggcttggc; GAPDH, accacagtccatgccatcac, tccaccaccctgttgctgta.

Preparation of Polyclonal Anti-CoAZ Antibody and Immunoblotting

Polyclonal anti-CoAZ (anti-ZnF) antibody was generated by immunizing rabbits with GST-CoAZ fusion protein (113–339 amino acids) (Covance). The antibody titer of each bleed was monitored by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. His-tagged CoAZ as antigen was cross-linked to the Affi-gel 10 resin and was used for affinity purification according to the manufacturer's protocol (Bio-Rad). Endogenous or overexpressed CoAA, CoAZ, and RBM4 were detected by immunoblotting using nuclear extracts from overexpressed 293 cells or from P19 stem cells or using whole cell extracts from rat cortical cell culture. Immunoblots were probed with anti-CoAA, anti-RRM, anti-ZnF, and anti-FLAG (Sigma) at a dilution of 1:200, 1:400, 1:400, and 1:10000, respectively. The blots were detected with the ECL system (Amersham Biosciences).

Immunohistochemistry and Immunofluorescence Staining

Polyclonal anti-CoAA (CoAA-specific, against 307–545 aa of CoAA) and anti-RRM antibody (against 1–156 amino acids of CoAM and recognizes CoAA, CoAM, and CoAZ) were previously prepared and affinity-purified (27). Anti-ZnF is against 113–339 amino acids of CoAZ and recognizes CoAZ and RBM4. The ES-derived embryoid bodies were paraffin-embedded, and the sections were stained with purified anti-CoAA, anti-RRM, anti-ZnF, and anti-active caspase-3 antibodies (United States Biological, C2087-16A). Sagittal sections of mouse embryonic tissue at E12.5 and E15.5 were stained with affinity-purified anti-ZnF at a dilution of 1:200. Antibody binding was detected using biotinylated anti-rabbit or anti-mouse IgG F(ab)2 secondary antibody followed by detecting reagents (DAKO). Sections were counterstained with hematoxylin. Immunofluorescence double staining was carried out using rabbit polyclonal anti-CoAA, anti-RRM, and anti-ZnF and counter-stained with mouse monoclonal anti-Nestin, anti-GFAP, and anti-MAP-2 antibodies. Cy3- and fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated secondary antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) were applied at a dilution of 1:200.

P19 and ES Cell Culture and Primary Neural Cell Culture

Mouse embryonal carcinoma P19 cells were maintained in α-modified minimum essential medium supplemented with 7.5% bovine calf serum and 2.5% fetal bovine serum, 100 units/ml penicillin, and 0.1 μg/μl streptomycin. Cells were incubated in 5% CO2 at 37 °C. Undifferentiated P19 cells (EC) were induced to differentiate by 500 nm all-trans retinoic acid (Sigma) up to 4 days in suspension culture to form embryoid bodies (EB2–4). The EBs were trypsinized and further differentiated (D3–15) for an additional 15 days in the absence of retinoic acid. Stably transfected P19 cells were selected using 400 μg/ml G418 for 3 weeks. Positive clones were identified by the presence of plasmid DNA and Western blot analysis. More than two stable clones for each transfection were identified and analyzed. For ES-derived embryoid bodies, pre-implantation blastocyst-derived ES cells J-1 were grown on γ-irradiated feeder fibroblasts, and neural differentiation was induced by serum deprivation of embryoid bodies as previously described (36, 37). To generate neural progenitors, embryoid bodies were trypsinized and plated on polyornithine/laminin-coated dishes to further culture 3 (NP3) or 5 (NP5) days. Cells were grown in DMEM/F-12 with N2 supplement and fibroblast growth facto-2. Cortical neural cells from embryonic rat brain at E18.5 were isolated and cultured in vitro for 7 days as previously described (38). For astrocytes, neural cells from P3 neonates were dissected, filtered with a 40 λm filter and cultured for 7 days. The culture was shaken overnight in the incubator at 180–220 rpm to remove contaminating cell types and retain astrocyte populations (39).

Luciferase Assay

CV-1 cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 units/ml penicillin, and 0.1 μg/μl streptomycin and incubated in 5% CO2 at 37 °C. Cells were cultured in 24-well plates and transfected with MMTV luciferase reporter and various amounts of glucocorticoid receptor, pcDNA3 vector, CoAA, CoAM, CoAZ, ncCoAZ, and RBM4 using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). Cells were incubated with the ligand dexamethasone (100 nm) to induce the MMTV-luciferase reporter, when applicable, for 16 h before harvest. Total amounts of DNA for each well were balanced by adding vector DNA. Relative luciferase activities were measured by a Dynex luminometer. Data are shown as the means of triplicate transfections ± S.D.

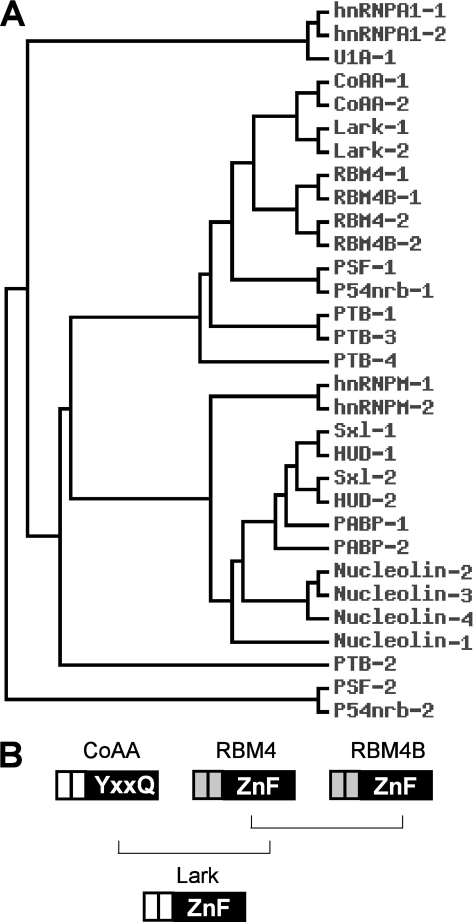

Phylogenetic Analysis

Protein sequences of the RNA recognition motif (RRM) domains were aligned with ClustalW 2.0.10 at EMBL European Bioinformatics Institute. The amino acid sequences within conserved RRMs containing four anti-parallel β-strands, and two α-helices were used to build the phylogenetic tree. The Cluster algorithm using matrix Blosum62 was performed at GeneBee Molecular Biology Server. The bootstrap analysis was carried out with 100 replicates.

RESULTS

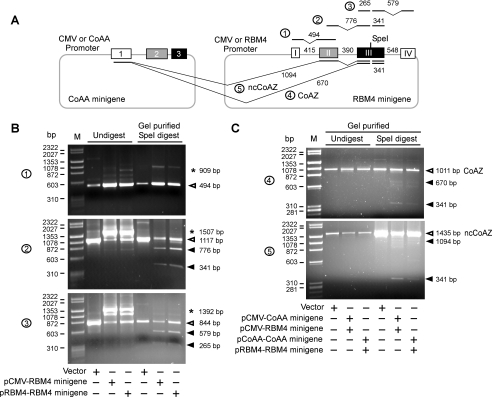

Identification of CoAZ and ncCoAZ as trans-Splicing Variants of CoAA and RBM4

We have previously reported that gene amplification and its associated genetic alterations in oncogene CoAA deregulate CoAA pre-mRNA alternative splicing and potentially impact stem cell differentiation (27, 28). At the 5′ boundary of all identified amplicons, CoAA (RBM14), RBM4, and RBM4B coregulator genes are consecutively aligned and are conserved in mammals. Supported by the NCBI EST data base (supplemental Fig. 1) as well as a genome-wide study (14), there are trans-splicing events between CoAA and its downstream RBM4 gene, which is ∼10 kilobases distal to CoAA. To identify these trans-splicing variants, total RNA from HeLa cells was extracted. RT-PCR analysis spanning both CoAA and RBM4 followed by sequencing analysis confirmed the presence of two trans-splicing events. As shown in Fig. 1A, CoAA contains three exons, and RBM4 contains four exons. In addition to the alternatively spliced transcripts corresponding to the CoAA and CoAM transcripts we previously reported (25, 27), we identified two additional transcripts, joining the CoAA first exon and the RBM4 second or third exons. Further 5′-RACE and 3′-RACE analyses were performed, and the two full-length trans-spliced cDNAs were cloned and designated as CoAZ (coactivator with zinc finger) and ncCoAZ (non-coding CoAZ). Both CoAZ and ncCoAZ share identical transcripts with CoAA at the 5′-untranslated region. The 3′-untranslated region of CoAZ and ncCoAZ is identical to that of the RBM4 transcript, indicating that they utilize the same polyadenylation signals. RACE analyses specific to ncCoAZ utilized primers in the RBM4 second exon (not shown). RACE analyses specific to CoAZ utilized splicing junction primers to enhance specificity (Fig. 1B). The results suggested that CoAZ is an in-frame fusion transcript that encodes a protein of 339 amino acids containing the first RRM domain of CoAA and a CCHC retroviral type zinc finger-containing C terminus of RBM4 (Fig. 1C). In contrast, the ncCoAZ transcript encodes a premature stop codon by joining the CoAA first exon and the RBM4 s exon. Thus, ncCoAZ does not yield a protein product that was confirmed by further analysis. In addition to their identification in human cells including HeLa and 293 cells, CoAZ and ncCoAZ were also identified in the mouse P19 stem cells we used in this study. Human and mouse CoAZ have significant identity in their primary sequences including a highly homologous RRM domain and an identical CCHC zinc finger (Fig. 1C). These results suggested that CoAZ and ncCoAZ were trans-splicing products of the CoAA and RBM4 genes with potentially conserved protein function in CoAZ.

FIGURE 1.

Identification of CoAZ and ncCoAZ as trans-splicing variants of CoAA and RBM4. A, schematic representation of CoAA and RBM4 genes in which introns are shown as lines and exons are boxes with splicing events depicted (not to scale). CoAA exons are numbered as 1–3 and RBM4 exons as I-IV. Translation start sites are indicated with ATG. The position of primers for 5′- and 3′-RACE of CoAZ are shown as open and filled arrows, respectively. The mRNA transcripts of CoAA and RBM4 and their corresponding protein products are shown with each region correlated with open, shaded, and filled boxes. RRM, CoAA activation domain (YXXQ), and RBM4 zinc finger-containing C terminus (ZnF) are indicated. Deposited accession numbers at NCBI GenBankTM are human CoAZ, EU287938; human ncCoAZ, EU287939; mouse CoAZ, EU287940; and mouse ncCoAZ, EU287941. B, 5′- and 3′-RACE analyses of CoAZ. Number indicates sequential PCR steps. C, aligned primary sequences of human and mouse CoAZ. The RRM domain is underlined, and the zinc finger is boxed. Non-identical amino acids between human and mouse are shaded. The arrow indicates the trans-splicing in-frame fusion site.

CoAZ and ncCoAZ Are Derived from trans-Splicing of Two Separated mRNAs

The donor and acceptor sites for the trans-splicing events in CoAZ and ncCoAZ are separated by ∼20 kilobases of sequence in both human and mouse. The possibility that CoAZ and ncCoAZ are produced by trans-splicing events from two independent transcripts rather than by cis-splicing events of a single long transcript is supported by the RT-PCR analyses using primers on different exons of CoAA and RBM4 (supplemental Fig. 2). To further confirm the trans-splicing events, we constructed the minigenes of CoAA and RBM4 and tested them in cells. As shown in Fig. 2A, each minigene contained shortened intron regions to facilitate the subsequent transfection. Both CoAA and RBM4 minigenes were driven by either a CMV promoter or their native promoter sequences. Our rationale was that trans-splicing events would be detected in cells between two independent minigenes if the wild type genes were naturally trans-spliced. Without trans-splicing events, PCR products will not be detected as the DNA templates are on two separated plasmids. The CoAA minigenes were previously described to retain alternative splicing capacities (27). Accordingly, RBM4 minigenes with either the native promoter or CMV promoter were similarly constructed. A SpeI restriction site was introduced into the RBM4 third exon to distinguish the minigene transcripts from the endogenous transcripts by restriction digestion. The RBM4 minigenes were first evaluated for their splicing capacities using RT-PCR after transfection of 293 cells. The size of PCR products indicated that all three RBM4 introns were correctly spliced out, although intron 1 splicing (494 bp) was more efficient (Fig. 2B). The splicing events of RBM4 intron 2 (1117 bp) and intron 3 (884 bp) were present but less efficient, leaving most of the products unspliced. The PCR products in the vector control represented the endogenous spliced transcripts. The gel-purified spliced transcripts were further digested by SpeI restriction enzyme. Our data clearly indicated the presence of digested fragments with the expected sizes that could only be derived from the minigenes (Fig. 2B and supplemental Fig. 3). The endogenous transcripts were not digestible. Because the minigenes retained splicing capacity, we then tested the trans-splicing events by co-transfection of both CoAA and RBM4 minigenes. RT-PCR analyses using primers at the CoAA first exon and RBM4 third exon were performed. The results demonstrated the presence of both CoAZ and ncCoAZ transcripts with digestible products in expected size (Fig. 2C). Our results did not rule out the possibility for trans-splicing between endogenous and minigene transcripts. However, the data nonetheless supported that CoAZ and ncCoAZ can be naturally produced by trans-splicing from two independently transcribed CoAA and RBM4 mRNAs.

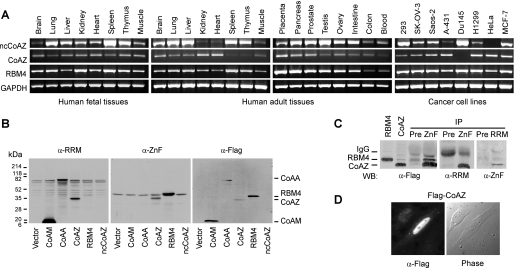

CoAZ and ncCoAZ Are Expressed in Normal Human Tissues

To confirm that the trans-splicing products CoAZ and ncCoAZ are not restricted to cancer cell lines we used for cloning but are also present in normal tissues, we investigated the endogenous mRNA distribution of CoAZ and ncCoAZ in multiple human fetal and adult tissues (Fig. 3A). The results suggested that both CoAZ and ncCoAZ mRNAs were widely expressed in normal tissues. The expression of CoAA in these tissues was previously reported (27); RBM4 was also widely expressed. In general, CoAA, RBM4, and ncCoAZ mRNAs are relatively more abundant than CoAZ. In the HeLa cell line, the expression of ncCoAZ was very low but, indeed present, as we cloned the two trans-splicing variants from HeLa cells. Together, CoAA, RBM4, and their splicing variants CoAZ and ncCoAZ are present in normal tissues.

FIGURE 3.

Expression of CoAZ, ncCoAZ, and RBM4. A, endogenous mRNA expression of CoAZ, ncCoAZ, and RBM4 was analyzed by PCR using normalized first strand cDNA panels from human adult and fetal tissues as well as cancer cell lines (Clontech). GAPDH was a control. B, Western blot analyses of CoAZ, ncCoAZ, and RBM4. 293 cells were transfected with FLAG-tagged CoAA, CoAM, CoAZ, RBM4, and ncCoAZ. Nuclear extracts were immunoblotted with anti-RRM, which recognizes the RRM domains of CoAA, CoAM, and CoAZ, with anti-ZnF, which recognizes the zinc-finger domain of RBM4 and CoAZ, and with anti-FLAG. ncCoAZ did not yield protein product. C, co-immunoprecipitation (IP) using overexpressed CoAZ and RBM4 in 293 cells. Individually expressed CoAZ or RBM4 were used as position markers. Preimmune sera were used as controls in co-immunoprecipitation. WB, Western blot. D, nuclear localization of FLAG-tagged CoAZ detected in transfected cells by immunofluorescence staining using anti-FLAG antibody.

CoAZ Contains RRM and Zinc Finger Domains, and ncCoAZ Does Not Encode a Protein Product

Although trans-splicing phenomena within closely linked genes have been reported, few of the studies detected the presence of a functional chimeric protein (40). To determine whether CoAZ and ncCoAZ transcripts encode protein products in cells, we generated a polyclonal antibody against amino acids 113–339 of CoAZ (α-ZnF) that also recognizes the RBM4 zinc finger-containing C terminus. The antibody recognizing the CoAZ RRM domain (α-RRM) can also detect CoAA and its splicing variant CoAM, which was previously described (28). Full-length expression plasmids of each clone with an N-terminal FLAG tag were transfected into 293 cells. The same nuclear extracts from each transfection were concurrently analyzed by Western blots probed with three antibodies against CoAA RRM (α-RRM), RBM4 C terminus (α-ZnF), and FLAG tag (α-FLAG). The results suggested that the CoAZ transcript produced a protein of the predicted size with a CoAA RRM domain and a RBM4 zinc finger-containing C terminus (Fig. 3B). In 293 cells the endogenous CoAZ was at a much lower level than the endogenous CoAA and RBM4 (Fig. 3B) even though the CoAZ mRNA was detectable (Fig. 3A). Coimmunoprecipitation studies further confirmed that CoAZ protein can be precipitated by both anti-RRM and anti-ZnF antibodies (Fig. 3C). To specifically detect the localization of CoAZ but not RBM4, FLAG-tagged CoAZ was transfected and analyzed by immunofluorescence using anti-FLAG. CoAZ protein was predominantly nuclear in localization (Fig. 3D). In contrast, ncCoAZ did not yield any detectable protein product, which was shown by anti-FLAG Western blot (Fig. 3B). These findings are consistent with our sequence analyses described above that ncCoAZ carries a premature stop codon. Although the ncCoAZ transcript contains a complete coding region of RBM4 whose translation start codon ATG is at the very N terminus of the RBM4 second exon (Fig. 1A), the different sequence in ncCoAZ immediately upstream of the RBM4 start codon may prevent RBM4 protein translation. In this regard, the expression of the ncCoAZ transcript may compete with the expression of RBM4 protein, thus providing a linked control of individual splicing forms through the control of trans-splicing. Therefore, the non-coding transcript ncCoAZ would equally have functional importance as the coding transcript CoAZ.

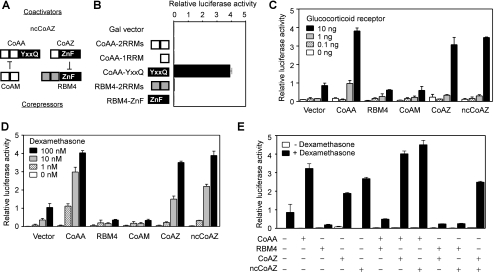

CoAZ and ncCoAZ Stimulates Nuclear Receptor-mediated Transcription

Because CoAA is a nuclear receptor coactivator, we then investigated the transcriptional activities of CoAZ and ncCoAZ. Each protein domain from CoAA and RBM4 was fused to the Gal4 DNA binding domain and tested on a Gal4-luciferase reporter. Neither the RRM domains nor the zinc finger-containing C-terminal region of RBM4 showed any transcriptional activity when compared with the CoAA activation domain (Fig. 4, A and B). These data indicated that RBM4 and CoAZ do not contain an intrinsic activation domain responsible for stimulation of transcription. We further studied the transcriptional activities of full-length clones in a glucocorticoid receptor-mediated transcription assay using MMTV-luciferase as a reporter and dexamethasone as a hormone ligand. This system was chosen for its high sensitivity and specificity in measuring transcriptional coregulator activities, although other transcriptional reporter systems could be used to yield similar results. Although CoAA stimulated transcription, RBM4 strongly inhibited transcription. Both CoAZ and ncCoAZ stimulated transcription in a hormone and receptor-dependent manner (Fig. 4, C and D). Their combined effects using cotransfection assays also confirmed that RBM4 potently repressed CoAZ- or ncCoAZ-induced transcriptional activation (Fig. 4E). CoAA contains an activation domain with YXXQ repeats (25). RBM4 lacks an activation domain and possesses a suppressive zinc finger C terminus. Therefore, the transcriptional stimulatory effect of CoAZ may be indirect, through competing corepressor RBM4 with the identical zinc finger in the absence of N-terminal double RRMs of RBM4 (Fig. 4A). On the other hand, ncCoAZ potently stimulates transcription in the absence of a protein product. This is potentially because of the inhibition of endogenous RBM4 expression as they share splicing sites. Thus, both coactivator variants could inhibit corepressor RBM4 via alternative trans-splicing.

FIGURE 4.

CoAZ and ncCoAZ stimulate transcription and promote CoAA activity. A, domain structures of CoAA, CoAM, CoAZ, and RBM4 proteins are depicted with open boxes as RRMs and filled boxes as the YXXQ or the ZnF domain. CoAM inhibits CoAA via RRMs, and CoAZ inhibits RBM4 via zinc finger domain. B, each depicted CoAA and RBM4 domain was fused to a Gal4 DNA binding domain for testing transcriptional activity. CV-1 cells were transiently transfected with Gal4-fusion proteins and a luciferase reporter containing five Gal4-binding sites. C, full-length CoAA, CoAM, RBM4, CoAZ, or ncCoAZ was tested for transcriptional activity using a MMTV-luciferase reporter in CV-1 cells. Each clone (200 ng) was cotransfected with a MMTV-luciferase reporter (100 ng) and an increasing amount of glucocorticoid receptor (0, 0.1, 1, 10 ng) which binds to the MMTV promoter. Cells were induced by glucocorticoid receptor ligand dexamethasone (100 nm) overnight, and the luciferase activity was measured by Dynex luminometer. D, similar transfections as in C except using 10 ng of glucocorticoid receptor and an increasing amount of dexamethasone (0, 1, 10, 100 nm). E, cells were cotransfected as indicated in the presence or the absence of dexamethasone (100 nm). Luciferase activities shown are the means of triplicate transfections ± S.D.

Endogenous Expression of CoAA, RBM4, and Their Variants during Neural Differentiation

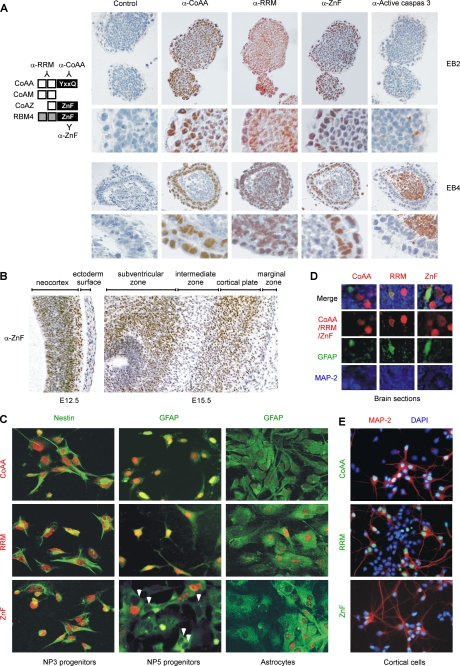

To study the biological importance of CoAA, RBM4, and their variants, we examined their endogenous expression using immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence in several physiological contexts. Mouse embryonic stem cells can be induced to form non-adhering cell aggregates called embryoid bodies (EB) that resemble the inner cell mass of embryos. The embryoid bodies reflect an early stage of neural differentiation. Further differentiation yields a mixture of cell types including neurons and glial cells as well as partially differentiated progenitors. At 2 days of embryoid body formation (EB2), both CoAA and RBM4 were highly expressed (Fig. 5A). Although anti-ZnF antibody recognized both RBM4 and CoAZ, RBM4 was far more abundant than CoAZ at this stage (see below). At 4 days of differentiation (EB4), the embryoid bodies formed cavities where apoptotic cells were positive for active caspase-3. The expression of CoAA and RBM4 were reduced in the cavities but were significant in the two primitive ectodermal and endodermal layers which undergo further differentiation (Fig. 5A). At this stage, CoAM, recognized by anti-RRM, was known to be in the embryoid body cavity, and its expression was cytoplasmic (27). Supporting this observation, embryonic mouse brain at gestational stages of E12.5 and E15.5 had high levels of protein expression recognized by anti-ZnF antibody (Fig. 5B). This pattern largely overlapped but was not identical to the CoAA expression pattern we analyzed previously (27). However, both expression levels were high at the stage of E15.5 in the cortical plate, which gives rise to the cerebral cortex. Neurogenesis is at its peak in this stage. The data suggested that CoAA and RBM4 or CoAZ may be differentially involved in neuronal cell differentiation. Further immunofluorescence studies showed that these proteins were indeed expressed in ES cell-derived early stage neural progenitors after 3 days (NP3) and 5 days (NP5) of culture (Fig. 5C), and differential expression was seen in certain subpopulations of the progenitors (white arrows in Fig. 5C indicate negative cells). When isolated astrocytes were analyzed, CoAA was absent in astrocytes (Fig. 5C). Proteins recognized by anti-ZnF appeared to be restricted in subpopulations of astrocytes. Consistent with the above, GFAP were not colocalized with CoAA but with proteins recognized by anti-ZnF in mouse brain, suggesting the presence of CoAZ or RBM4 in astrocytes (Fig. 5D). Furthermore, in cortical neural cells isolated from rat embryonic brain cortex at E18.5 followed by in vitro culture for 7 days (38), CoAA was restricted in microtubule-associated protein-2 (MAP-2) positive neurons but not in other neural cell types such as astrocytes (Fig. 5E). RBM4 or CoAZ was present in both neurons and astrocytes. The precise location of each protein variant needs to be further studied. These data nonetheless suggest that the expression of CoAA, RBM4, and their variants is correlated to different cell lineages and may be physiologically relevant to neural differentiation of stem/progenitor cells.

FIGURE 5.

Endogenous expression of CoAA, RBM4, and CoAZ during neural differentiation. A, the diagram at the left indicates antibodies recognizing each variant. ES cell-derived embryoid bodies at 2 days (EB2) and 4 days (EB4) of differentiation stage were paraffin-embedded, sectioned, and stained with affinity-purified anti-CoAA (CoAA only), anti-RRM (CoAA, CoAM, and CoAZ), anti-ZnF (RBM4 and CoAZ), and anti-active caspase-3 (cleaved caspase-3) antibodies and counterstained with hematoxylin. Enlarged views are shown below. B, immunohistochemistry analyses of mouse embryonic brain at gestation stages of E12.5 and E15.5. The sagittal sections were stained with anti-ZnF antibody (1:200). C, immunofluorescence staining of ES cell-derived neural progenitors after 3 days (NP3) or 5 days (NP5) of culture using anti-CoAA, anti-RRM, and anti-ZnF antibodies co-stained with the neural progenitor marker nestin or astrocyte cell marker GFAP (left and middle panels). White arrows indicate negatively stained cells. Double staining of isolated astrocytes from brain of P3 neonates using GAFP (right panel). D, mouse brain sections from P3 neonates were stained with anti-CoAA, anti-RRM, and anti-ZnF antibodies and co-stained with GFAP and MAP-2. E, double staining in MAP-2 positive neurons or MAP-2 negative astrocytes from isolated rat brain cortical cells at E18.5 after 6 days of culture in vitro. Slides are counter-stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole.

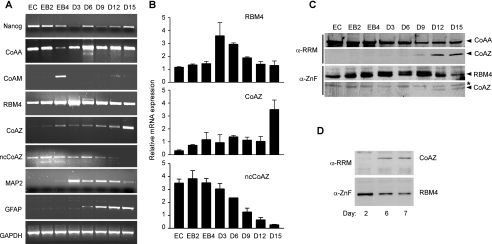

Switched Expression of CoAZ and ncCoAZ mRNAs during Stem/Progenitor Cell Differentiation

We have demonstrated in a previous study the presence of switched expression of CoAA and its splice variant CoAM during P19 cell differentiation. We then analyzed the expression patterns of RBM4, CoAZ, and ncCoAZ using this system. P19 is a teratocarcinoma-derived pluripotent stem cell line that can give rise to all three germ layers in mice (41). Retinoic acid induces undifferentiated P19 cells (EC) to form embryoid bodies (EB2-EB4) which continue to differentiate into multiple neural lineages (D3–15). Total RNA was isolated at each time point during differentiation followed by RT-PCR analysis of CoAA, RBM4, and their variants. These PCR products were sequenced to confirm the identities of each variant. Consistent with our previous findings for the switched expression of CoAA and CoAM, the expression of CoAZ gradually increased, whereas the expression of ncCoAZ decreased at a much later differentiation stage (Fig. 6A), which was confirmed by real-time PCR quantitation (Fig. 6B). The data indicated that a switch of CoAZ and ncCoAZ expression has occurred as both utilize the same 5′ alternative splicing site. The expression of RBM4 increased during initial differentiation and decreased at a later stage. Other markers were concurrently analyzed as controls during differentiation. Nanog is known to be decreased during initial stem cell differentiation (42). MAP-2 and GFAP are neuronal and glial cell markers, respectively (Fig. 6A). Of note, there were potential correlations between CoAZ and GFAP, which is an astrocyte marker at the later stages of differentiation. In addition, changed levels of CoAZ and RBM4 detected by Western blot were consistent with their mRNA levels (Fig. 6C). A 35-kDa band corresponding to CoAZ was detected by both antibodies. Furthermore, the increase of CoAZ and the decrease of RBM4 were also detected by Western blotting in primary cortical cells of rat brain, which reflects a later stage of neural differentiation (Fig. 6D) (38). These data together suggested that the alternative splicing including trans-splicing events between the CoAA and RBM4 genes are switched during stem cell differentiation, resulting in differential expression of each form in different cell lineages.

FIGURE 6.

Alternative splicing switch between CoAZ and ncCoAZ during P19 embryonal carcinoma cell differentiation. A, undifferentiated P19 cells (EC) were induced by 500 nm retinoic acid in suspension culture up to 4 days to form embryoid bodies (EB2–EB4). Cells were further differentiated for an additional 15 days in the absence of retinoic acid (D3–D15). Total RNA was isolated and normalized at each stage and analyzed using gene-specific primers by RT-PCR as indicated. GAPDH was control. B, quantitative real-time PCR analysis of RBM4, CoAZ, and ncCoAZ at each stage using clone-specific primers. C, immunoblot analyses of CoAZ and RBM4 using anti-RRM and anti-ZnF antibodies during P19 cell differentiation. The asterisk indicates a nonspecific band. D, immunoblot analyses of CoAZ and RBM4 in isolated primary rat brain cortical cells after 2, 6, and 7 days of in vitro culture as indicated.

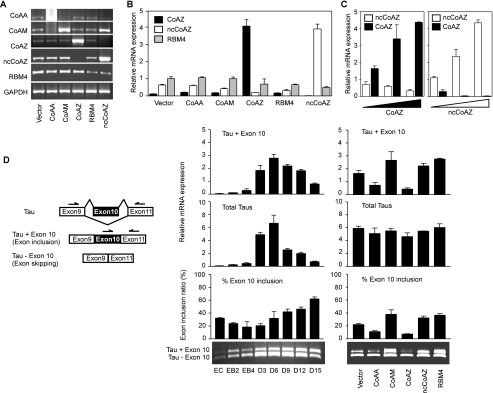

CoAA, RBM4, and Their Variants Regulate Alternative Splicing of Tau Exon 10

Alternative splicing control of CoAA and RBM4 genes leads to linked expression of functionally related variants. We then overexpressed each clone in 293 cells and analyzed the mRNA levels of neighboring variants. The results suggested that at the mRNA expression level, CoAA inhibits CoAM and CoAZ inhibits ncCoAZ and vice versa (Fig. 7, A and B). Quantitative PCR analysis confirmed that CoAZ and ncCoAZ had a reciprocal relationship in their expression (Fig. 7C). In addition, ncCoAZ was able to repress endogenous RBM4 expression and to alter the balance of CoAA and CoAM (Fig. 7A). To avoid overlapping with ncCoAZ, RBM4 was analyzed only for its endogenous mRNA. These expression patterns can be clearly explained by their shared alternative splicing sites and potential feedback regulation (Fig. 1A). Theses results indicated that the expression of CoAA, RBM4, and their variants are linked through alternative splicing and trans-splicing. CoAA is a dominant coactivator, and RBM4 is a dominant corepressor. Each can be competed by its cell-specific splicing variant CoAM or CoAZ, respectively, through shared functional domains (Fig. 4A). Their overall expression levels and alternative splicing balance are further subjected to regulation by yet another non-coding variant, ncCoAZ, which is efficiently produced by trans-splicing.

FIGURE 7.

CoAA, RBM4, and their variants regulate alternative splicing of Tau exon 10. A, 293 cells were transfected with pcDNA3 vector, CoAA, CoAM, CoAZ, RBM4, or ncCoAZ followed by RT-PCR analyses using gene-specific primers of each transcript as indicated. The detected signals represent both endogenous and overexpressed transcripts except for RBM4. The RBM4 transcript overlaps with the ncCoAZ transcript, and only endogenous RBM4 was analyzed. B, quantitative PCR analysis of mRNA levels of RBM4, CoAZ, and ncCoAZ (200 ng) transfected 293 cells. C, an increasing amount of CoAZ or ncCoAZ (50, 200, 400 ng) was transfected before quantitative PCR. D, the diagram at the left illustrates alternative splicing of Tau exon 10. Primers on exons 9 and 11 detect total Tau mRNA, and primers on exons 10 and 11 detect Tau exon 10 inclusion isoform only. Middle panel, data are shown as real-time PCR quantification of endogenous expression levels of Tau exon 10 inclusion (Tau + Exon 10), total Tau, and their ratio. RT-PCR gel is shown below. The mRNA samples of P19 cell differentiation in this assay were the same preparation as in Fig. 6A. Right panel, Tau alternative splicing analysis in undifferentiated P19 stem cells (EC) overexpressed with CoAA, RBM4, and their variants as indicated. RT-PCR gel is shown below the PCR quantification.

To test this model on a physiological target gene, we chose to analyze Tau, as RBM4 has been previously identified by another group through a library screen that binds to Tau mRNA and promotes Tau exon 10 inclusion (29). The microtubule-associated protein Tau is important for neuronal function. Exon 10 inclusion or skipping of Tau produces spliced isoforms whose imbalance is associated with multiple neurodegenerative diseases collectively called “tauopathies” (35). We then tested if CoAA and the variants also regulate Tau exon 10. PCR primers were designed on exon 9 and 11 for total Tau mRNA expression and on exon 10 and 11 for exon inclusion only (Fig. 7D). Consistent with the previous findings that the fetus has more exon skipping and the adult has more exon inclusion (43), RT-PCR and real-time quantification showed that the endogenous Tau exon 10 inclusion gradually decreased and then increased during P19 cell differentiation (Fig. 7D, left panel). The total amount of Tau expression peaked in parallel with MAP-2 (Fig. 6A), suggesting that Tau may be involved in neuronal functions. We then overexpressed CoAA, RBM4, and their variants CoAM, CoAZ, and ncCoAZ in undifferentiated P19 stem cells. The vector was a control representing the endogenous Tau levels. The results indicated that CoAA and CoAZ promoted exon 10 skipping. RBM4, CoAM, and ncCoAZ promoted exon 10 inclusion (Fig. 7D, right panel). In neurons, balanced Tau splicing may be maintained by both CoAA and RBM4, which are present in the cortical plate (Fig. 5B). During gliogenesis, the absence of CoAA and the presence of RBM4 in subpopulations of astrocytes (Fig. 5F) may explain the increased Tau exon 10 inclusion at the late stage of P19 cell differentiation. The data together suggested that CoAA and RBM4 counter-regulate Tau exon 10 splicing. The differential expression of CoAA, RBM4, and their variants potentially contribute to cell-specific expression of Tau isoforms.

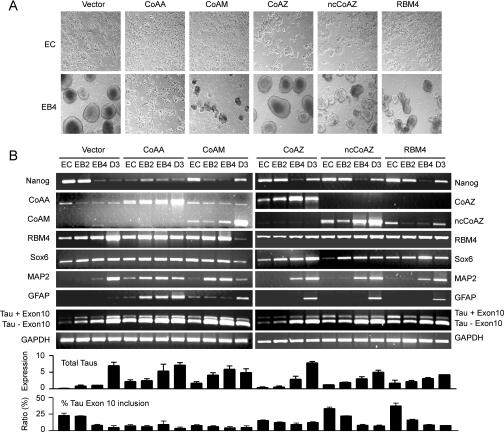

Using stably transfected stem cells, we further investigated CoAA, RBM4, and their variants in embryoid body formation. The choice of stable overexpression rather than small interfering RNA (siRNA) knockdown was made because of the lack of sequence specificity for small interfering RNA siRNA in overlapped variants. The constant overexpression by the CMV promoter would disrupt the switched expression patterns required for embryoid body formation. Compared with the vector control, the stable CoAA, CoAM, RBM4, and ncCoAZ cells had defects in formation of embryoid bodies (Fig. 8A). Stable CoAZ cells did not significantly affect the formation of embryoid bodies possibly because of the requirement of CoAZ in a later stage of differentiation. The results for each transfected stable cell were consistently seen in more than two selected stable clones. The vector control showed no detectable difference from untransfected cells in the aspects of embryoid body formation or marker gene expression (not shown). When marker gene expression was analyzed by PCR, the results showed the altered expression levels in both neural lineage markers MAP-2, GFAP, and Tau as well as non-neural lineage markers Nanog and Sox6 (Fig. 8B). In particular, the expression of Tau was elevated before retinoic acid induction in CoAA CoAM, ncCoAZ, and RBM4 stable cells. The exon 10 inclusion of Tau was increased in ncCoAZ and RBM4 stable cells. The data were confirmed by quantitative PCR analysis (Fig. 8B). Although the stable expression did not reflect physiological conditions, the data implicated that the balance of CoAA and RBM4 and their variants is involved in controlling stem/progenitor cell differentiation. Because CoAA and RBM4 are coregulators in multiple tissues, their target genes may include neural lineage genes such as Tau but may not be limited to neural lineage. The imbalance of CoAA and RBM4 activities through the control of their variants can disrupt normal differentiation program.

FIGURE 8.

Stable expression of CoAA and RBM4 in P19 cells disrupts embryoid body cavitation. A, light microscopy images of P19 stable cells expressing CoAA, CoAM, CoAZ, ncCoAZ, and RBM4 under the CMV promoter. The uninduced P19 stable cells (EC) and in retinoic acid-induced embryoid bodies at EB4 stages are shown (×400). Vector pcDNA3 was a control. B, RT-PCR analyses of Tau isoforms with (Tau + Exon 10) or without (Tau − Exon 10) exon 10 inclusion in stable P19 cells at differentiation stages of EC, EB2, EB4, and D3. The marker genes used include Nanog, Sox6, MAP-2, and GFAP. GAPDH was a control. Quantitative PCR analysis of total Tau and percentage of Tau exon 10 inclusion are shown below.

DISCUSSION

In this study we have identified trans-splicing events between the CoAA and RBM4 genes, which yield a novel zinc finger-containing coactivator CoAZ and a non-coding splice variant ncCoAZ. Based on the collective evidence, we propose a model in which the C-terminal activation domain of CoAA stimulates transcription and the C-terminal zinc finger domain of RBM4 represses transcription. RBM4 competes with CoAA through highly homologous double RRM domains at their N termini, which might be responsible for the pre-mRNA interaction during transcription-coupled alternative splicing. CoAM, an alternative splice variant containing only the double RRMs of CoAA, has been previously shown to repress CoAA activity. CoAZ contains an intact RBM4 zinc finger but defective double RRMs and, thus, competes with RBM4 to indirectly facilitate the CoAA activity. ncCoAZ, although producing no protein product, regulates both CoAA and RBM4 expression via competitive splicing or by participates in potentially unidentified downstream RNA metabolism that impacts both CoAA and RBM4 transcripts. Thus, coactivator CoAA, corepressor RBM4, and their splice variants CoAM, CoAZ, and ncCoAZ have established a linked control because of the presence of alternative splicing and trans-splicing. When they are specifically expressed in different cell lineages, alternative splicing or trans-splicing would constitute a mechanism in regulating the coregulator balance in each cell lineage.

The phenomenon of trans-splicing has been found in a variety of organisms including trypanosomes (44), Caenorhabditis elegans (45), euglenoids (46), flatworms (47), Drosophila (48), and mammals (49). It is frequently found within a cluster of genes using canonical splice sites and generating translatable mRNA (40). In mammals, the consecutive arrangement of the three genes CoAA (RBM14), RBM4, and RBM4B is highly conserved. All three genes encode RRM-containing proteins and function as alternative splicing regulators. Our study on trans-splicing between CoAA and RBM4 implies that these genes are associated as a gene cluster and share a common enhancer sequence. Expressed sequence tag evidence also supports the presence of splicing events between RBM4 and RBM4B, although at a lower frequency (supplemental Fig. 1). The RBM4B gene encodes an RBM4 isoform (30), and both proteins are mammalian orthologs of the Drosophila protein Lark (32), which was originally identified in Drosophila circadian rhythm regulation and early development (34). We performed a phylogenetic analysis using 31 well studied human and Drosophila RRM domains including those from CoAA, RBM4, RBM4B, and Lark and found that the two RRM domains in Drosophila Lark are most closely related to the two RRM domains in human CoAA (Fig. 9A). Human RBM4 and RBM4B are also closely related to each other. Thus, the Lark gene possibly shares common ancestry with the entire mammalian gene cluster including CoAA, RBM4, and RBM4B (Fig. 9B). CoAA is a coactivator and alternative splicing regulator (23, 25) involved in embryoid body differentiation (27). RBM4 is a corepressor and has been previously identified as alternative splicing regulator that shares nuclear import pathways with SR proteins (30) and antagonizes polypyrimidine tract-binding protein splicing activities (31). The RRM domain of Drosophila Lark is involved in maternal function, flight behavior, and developmental control (33). The zinc finger domain of Lark impacts wing morphology and flight behavior. CoAA and RBM4 function in stem or progenitor cells reflects Lark in development. Their functional similarity underscores alternative splicing controls in differentiation and development and further supports that the trans-splicing of CoAA and RBM4 is functionally necessary and, therefore, preserved during evolution.

FIGURE 9.

Human CoAA, RBM4 and BM4B share common ancestry with Drosophila Lark. A, phylogenetic tree displaying the selected well characterized RRM-containing proteins. The tree was constructed using primary sequences within each RRM domain. Lark and Sxl are Drosophila proteins, and the rest are human proteins. The number indicates the RRM domain within each molecule. B, a hypothetic diagram of the evolutionary relationship among human CoAA, RBM4, and RBM4B and Drosophila Lark.

The CoAA gene may have evolved at a relatively early stage of evolution, whereas RBM4 and RBM4B were derived by gene duplication at a later stage. This prediction is intriguingly consistent with a proposed theory from the studies of the tumor necrosis factor receptor type 2 gene (p75TNFR) and many other similar cases, in which alternative splicing is required during gene evolution (12). The theory suggests that newly evolved exons are first introduced by Alu repeat-containing transposable elements. Alternative splicing has subsequently evolved to neutralize the potential impact of the creation of a new exon. Gene duplication is further introduced at a later stage of evolution to release the internal constraint caused by alternative splicing (12). In the case of the CoAA gene cluster, there are six Alu repeat elements within the CoAA first intron. The activation domain encoded by the CoAA second exon is likely a new exon, as it is absent in Drosophila and lower eukaryotes. If the coactivator CoAA gene were recently created, resulting in activities that impact the corepressor RBM4, the alternative trans-splicing we now identified may have evolved to neutralize the impact of the creation of CoAA gene. The RBM4B gene could have been derived later because of a gene duplication to escape the regulation or constraint by CoAA alternative trans-splicing, when a complex cell-specific splicing activity is required in higher species. The RBM4B isoform possibly has cell-specific expression distinguishable from RBM4 (53). The evolution of the CoAA gene cluster reflects the increasing complexity of splicing regulation because of the increasing cell- and tissue-specificity.

As coregulators, CoAA and RBM4 would have a number of target genes that remain to be identified. Tau has previously been identified as a RBM4 target gene (29), and this study indicates that both CoAA and RBM4 cooperatively regulate Tau alternative splicing. Tau is involved in the intracellular filamentous deposits that define multiple neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer disease, progressive supranuclear palsy, corticobasal degeneration, Pick disease, and the inherited frontotemporal dementia and parkinsonism linked to chromosome 17, collectively known as tauopathies (50, 51). Tau exon 10 encodes a microtubule binding repeat whose inclusion or exclusion yields Tau isoforms with a different number of repeats. The delicately balanced Tau isoforms are critical for neuronal function in learning and memory (52), and splicing mutations of Tau have been found in neurodegenerative diseases (35). The splicing activities provided by the CoAA gene cluster will balance Tau isoforms and are important for neurodegenerative disease. Supporting the notion that alternative splicing contributes to both disease and cancer, we have previously found that the human CoAA gene cluster is amplified with recurrent loss of the 5′ regulatory enhancer in many common solid tumors (28). The enhancer loss associated with gene amplification prevents a complete alternative splicing switch from CoAA to CoAM at the stage of embryoid body cavitation during normal stem cell differentiation (27). Our current study suggests the presence of complex alternative splicing and trans-splicing patterns within the CoAA gene cluster encoding transcriptional coregulators. When differentially expressed, these coregulator variants will facilitate lineage-specific gene expression during cell differentiation and development. A defective control of alternative splicing in the CoAA gene cluster potentially leads to disease and cancer.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Lori Redmond, Yu-chih Lin, and Nahid F. Mivechi for valuable help. We thank Doris B. Cawley for immunohistochemistry analysis.

This work was supported by a Georgia Cancer Coalition Distinguished Cancer Scholar Award (to L. K.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. 1–3.

- CoAA

- coactivator activator

- CoAM

- coactivator modulator

- CoAZ

- coactivator with zinc finger

- ncCoAZ

- non-coding CoAZ

- RBM4

- RNA binding motif protein 4

- ES

- embryonic stem

- EC

- embryonic carcinoma

- EB

- embryoid body

- RRM

- RNA recognition motif

- GFAP

- glial fibrillary acidic protein

- RT

- reverse transcription

- RACE

- rapid amplification of cDNA ends

- CMV

- cytomegalovirus

- GAPDH

- glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- MMTV

- murine mammary tumor virus

- MAP-2

- microtubule-associated protein-2.

REFERENCES

- 1.Berget S. M., Moore C., Sharp P. A. ( 1977) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 74, 3171– 3175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chow L. T., Gelinas R. E., Broker T. R., Roberts R. J. ( 1977) Cell 12, 1– 8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Modrek B., Lee C. ( 2002) Nat. Genet. 30, 13– 19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sanford J. R., Caceres J. F. ( 2004) J. Cell Sci. 117, 6261– 6263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pan Q., Shai O., Lee L. J., Frey B. J., Blencowe B. J. ( 2008) Nat. Genet. 40, 1413– 1415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang E. T., Sandberg R., Luo S., Khrebtukova I., Zhang L., Mayr C., Kingsmore S. F., Schroth G. P., Burge C. B. ( 2008) Nature 456, 470– 476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stetefeld J., Ruegg M. A. ( 2005) Trends Biochem. Sci. 30, 515– 521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stamm S., Ben-Ari S., Rafalska I., Tang Y., Zhang Z., Toiber D., Thanaraj T. A., Soreq H. ( 2005) Gene 344, 1– 20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith C. W., Patton J. G., Nadal-Ginard B. ( 1989) Annu. Rev. Genet. 23, 527– 577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kalnina Z., Zayakin P., Silina K., Linē A. ( 2005) Genes Chromosomes Cancer 42, 342– 357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Venables J. P. ( 2006) BioEssays 28, 378– 386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xing Y., Lee C. ( 2006) Nat. Rev. Genet. 7, 499– 509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mayer M. G., Floeter-Winter L. M. ( 2005) Mem. Inst. Oswaldo. Cruz 100, 501– 513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Akiva P., Toporik A., Edelheit S., Peretz Y., Diber A., Shemesh R., Novik A., Sorek R. ( 2006) Genome Res. 16, 30– 36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eddy S. R. ( 2001) Nat. Rev. Genet. 2, 919– 929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mattick J. S., Makunin I. V. ( 2006) Hum. Mol. Genet. 15, R17– 29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brose M. S., Volpe P., Paul K., Stopfer J. E., Colligon T. A., Calzone K. A., Weber B. L. ( 2004) Genet. Test 8, 133– 138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neklason D. W., Solomon C. H., Dalton A. L., Kuwada S. K., Burt R. W. ( 2004) Fam. Cancer 3, 35– 40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ozcelik H., Nedelcu R., Chan V. W., Shi X. H., Murphy J., Rosen B., Andrulis I. L. ( 1999) Hum. Mutat. 14, 540– 541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Adamia S., Reiman T., Crainie M., Mant M. J., Belch A. R., Pilarski L. M. ( 2005) Blood 105, 4836– 4844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yeo G. W., Xu X., Liang T. Y., Muotri A. R., Carson C. T., Coufal N. G., Gage F. H. ( 2007) PLoS Comput. Biol. 3, 1951– 1967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boutz P. L., Stoilov P., Li Q., Lin C. H., Chawla G., Ostrow K., Shiue L., Ares M., Jr., Black D. L. ( 2007) Genes Dev. 21, 1636– 1652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Auboeuf D., Dowhan D. H., Li X., Larkin K., Ko L., Berget S. M., O'Malley B. W. ( 2004) Mol. Cell. Biol. 24, 442– 453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kornblihtt A. R. ( 2005) Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 17, 262– 268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Iwasaki T., Chin W. W., Ko L. ( 2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 33375– 33383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kang Y. K., Schiff R., Ko L., Wang T., Tsai S. Y., Tsai M. J., O'Malley B. W. ( 2008) Cancer Res. 68, 7887– 7896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang Z., Sui Y., Xiong S., Liour S. S., Phillips A. C., Ko L. ( 2007) Nucleic Acids Res. 35, 1919– 1932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sui Y., Yang Z., Xiong S., Zhang L., Blanchard K. L., Peiper S. C., Dynan W. S., Tuan D., Ko L. ( 2007) Oncogene 26, 822– 835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kar A., Havlioglu N., Tarn W. Y., Wu J. Y. ( 2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 24479– 24488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lai M. C., Kuo H. W., Chang W. C., Tarn W. Y. ( 2003) EMBO J. 22, 1359– 1369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lin J. C., Tarn W. Y. ( 2005) Mol. Cell. Biol. 25, 10111– 10121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jackson F. R., Banfi S., Guffanti A., Rossi E. ( 1997) Genomics 41, 444– 452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McNeil G. P., Schroeder A. J., Roberts M. A., Jackson F. R. ( 2001) Genetics 159, 229– 240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McNeil G. P., Zhang X., Genova G., Jackson F. R. ( 1998) Neuron 20, 297– 303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pittman A. M., Fung H. C., de Silva R. ( 2006) Hum. Mol. Genet. 15, R188– 195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bieberich E., MacKinnon S., Silva J., Noggle S., Condie B. G. ( 2003) J. Cell Biol. 162, 469– 479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang G., Silva J., Krishnamurthy K., Tran E., Condie B. G., Bieberich E. ( 2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 26415– 26424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Redmond L., Kashani A. H., Ghosh A. ( 2002) Neuron 34, 999– 1010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schwartz J. P., Wilson D. J. ( 1992) Glia 5, 75– 80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Finta C., Zaphiropoulos P. G. ( 2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 5882– 5890 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.van der Heyden M. A., Defize L. H. ( 2003) Cardiovasc. Res. 58, 292– 302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cavaleri F., Schöler H. R. ( 2003) Cell 113, 551– 552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dehmelt L., Halpain S. ( 2005) Genome Biol. 6, 204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Parsons M., Nelson R. G., Watkins K. P., Agabian N. ( 1984) Cell 38, 309– 316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Krause M., Hirsh D. ( 1987) Cell 49, 753– 761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tessier L. H., Keller M., Chan R. L., Fournier R., Weil J. H., Imbault P. ( 1991) EMBO J. 10, 2621– 2625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rajkovic A., Davis R. E., Simonsen J. N., Rottman F. M. ( 1990) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 87, 8879– 8883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dorn R., Reuter G., Loewendorf A. ( 2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 9724– 9729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Eul J., Graessmann M., Graessmann A. ( 1995) EMBO J. 14, 3226– 3235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.D'Souza I., Schellenberg G. D. ( 2005) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1739, 104– 115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Goedert M. ( 2005) Mov. Disord. 20, Suppl. 12, S45– 52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liu F., Gong C. X. ( 2008) Mol. Neurodegener. 3, 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pfuhl T., Mamiani A., Dürr M., Welter S., Stieber J., Ankara J., Liss M., Dobner T., Schmitt A., Falkai P., Kremmer E., Jung V., Barth S., Grässer F. A. ( 2008) Neurosci. Lett. 444, 11– 15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.