Abstract

Our recent study has shown that βA3-crystallin along with βB1- and βB2-crystallins were part of high molecular weight complex obtained from young, old, and cataractous lenses suggesting potential interactions between α- and β-crystallins (Srivastava, O. P., Srivastava, K., and Chaves, J. M. (2008) Mol. Vis. 14, 1872–1885). To investigate this further, this study was carried out to determine the interaction sites of βA3-crystallin with αA- and αB-crystallins. The study employed a mammalian two-hybrid method, an in vivo assay to determine the regions of βA3-crystallin that interact with αA- and αB-crystallins. Five regional truncated mutants of βA3-crystallin were generated using specific primers with deletions of N-terminal extension (NT) (named βA3-NT), N-terminal extension plus motif I (named βA3-NT + I), N-terminal extension plus motifs I and II (named βA3-NT + I + II), motif III plus IV (named βA3-III + IV), and motif IV (named βA3-IV). The mammalian two-hybrid studies were complemented with fluorescence resonance energy transfer acceptor photobleaching studies using the above described mutant proteins, fused with DsRed (Red) and AcGFP fluorescent proteins. The results showed that the motifs III and IV of βA3-crystallin were interactive with αA-crystallin, and motifs II and III of βA3-crystallin primarily interacted with αB-crystallin.

The structural proteins (crystallins) of the vertebrate lens belong to two families, i.e. α-crystallin and β-γ crystallins superfamily. Although α-crystallin is made of two primary gene products of αA and αB-crystallins, the β-γ superfamily is constituted by four acidic (βA1, βA2, βA3, and βA4) and three basic (βB1, βB2, and βB3) β-crystallins and six γ-crystallins (γA, γB, γC, γD, γE, and γF) (1, 2). High concentrations of these crystallins and their interactions provide refractive power to the lens for focusing light on to the retina. Both αA- and αB-crystallins also function as molecular chaperons and prevent aberrant protein interactions and protein unfolding. The β- and γ-crystallins have only structural properties (2–4), except that our results showed that βA3 crystallin contains proteinase activity (5, 6). The expressions of the crystallins are both developmentally and spatially regulated (1), and their interactions lead to the transparency of the lens because of short range order of the crystallin matrix (7, 8).

Previous reports have shown that the α-crystallin interacts with other crystallins and intermediate filaments (2). An interaction of α-crystallin with βL-crystallin produced filament-like structures, and similar interactions between βL-crystallin with αA-crystallin (isolated from UV-A-irradiated lenses) showed even more pronounced filament formation (9). A similar study of interaction between α-crystallin and βL-crystallin at 60 °C produced soluble complexes with mean radius of gyration ∼14 nm, mean molecular mass of ∼4 × 106 Da, and maximum size of 40 nm (10). Recently, we dissociated a fraction containing βA3-, βB1-, and βB2-crystallins from the α-crystallin fraction of human lenses by detergent treatment, which suggested the existence of a complex of these crystallins in the soluble protein fraction (6). Together, the above studies suggest potential interactions between α- and β-crystallins in vivo.

Delaye and Tardieu proposed in 1983 (7) that the short range order of crystallin proteins accounts for the lens transparency. It is primarily dependent on high crystallin concentrations, interactions among crystallins, and on organization of cytoskeletal and membrane constituents (3, 8). Numerous studies have been done to understand the heterogeneous interactions among α-, β-, and γ-crystallins, yet such interactions remain unclear because of their complex nature. Several investigators have utilized a variety of techniques to study the dynamics involved in crystallin-crystallin interactions and analyze factors that could affect the short range order of crystallins. These techniques included fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET)2 (11), cross-linking studies (12), spectroscopy (13), protein pin arrays (14), micro-equilibrium dialysis (15), and surface plasmon resonance (16). These studies determined interactions among various crystallins in vitro utilizing either wild-type or mutated crystallins to understand their roles in crystallin-crystallin interactions during normal conditions and cataract development. A study using surface plasmon resonance method showed that the self-association among subunits of α-crystallin was mainly driven by αA-crystallin, and among the two, αB subunit had relatively stronger binding affinity to β- and γ-crystallins (16). However, the in vitro experiments have several drawbacks. These include a need to purify proteins, a cumbersome process that might alter their conformation during multiple steps of purification, and the results provide indirect evidence that is nonphysiological.

To better understand the crystallin-crystallin interactions that affect protein solubility and therefore lens transparency, in vivo methods such as confocal microscopy with FRET acceptor photobleaching and mammalian two-hybrid assay approaches have recently been used (17–22). For instance, the study of crystallin interactions by the two-hybrid system showed significant interactions between α- and β/γ-crystallins (23). Also, the two-hybrid assay exhibited that mutations in αA-, αB-, and γ-crystallins during congenital cataracts altered protein-protein interactions (24), which might contribute to decreased protein solubility and cataract development. Because the two-hybrid system is more sensitive to determine protein-protein interactions than in vitro measurements, it can detect weak as well as transient interactions among crystallins. Moreover, the advantage of the two-hybrid system is that it allows detection of biologically significant interactions among crystallins in a physiological environment of living cells. Confocal FRET microscopy (FRET acceptor photobleaching) is yet even a more powerful approach compared with the two-hybrid system as it circumvents the need of a expressed protein to move to nucleus for transcriptional activation of the reporter gene, and it also provides direct visual assessment of crystallin-crystallin interaction in a physiological environment of living cells (19–21).

During aging and cataract development, post-translational modifications (PTM) of crystallins can disrupt short range order of crystallins, and therefore, PTMs play a crucial role in aggregation, cross-linking, and insolubilization of crystallins (2). Our recent studies (25–27) and those of others (28, 29) showed the presence of covalent multimers of crystallins in human lenses increased with aging. One of the major findings from our studies was the presence of fragments of β-crystallins, mainly of βA3-crystallin along with α-crystallin in water-soluble high molecular weight and water-insoluble protein fractions of aging and cataractous human lenses (26, 27). Also, recent genetic studies clearly demonstrated that the association of human inherited autosomal dominant, congenital zonular, or nuclear sutural cataracts with misfolded proteins or premature termination of crystallins was the consequence of truncation at the translational level (30–32). Therefore, truncations of crystallins could occur as a result of PTMs, splice mutation, point mutations, or non-sense mutations and might lead to their altered solubility, oligomerization, and supramolecular assembly (33, 34). These aberrations are believed to be averted by virtue of chaperone function of α-crystallin that involves its binding to damaged species of β/γ-crystallins in vivo (2).

Besides the chaperone functions, another function of α-crystallin is the inhibition of proteinases. Numerous studies have shown that both human and bovine α-crystallins exhibited inhibitor activity toward trypsin, elastase (35, 36), caspase-3 (37, 38), and an endogenous lens proteinase (39). In addition, our studies have shown that the βA3-proteinase existed in an inactive state in the α-crystallin fraction and gets activated with detergents (5, 6), suggesting that α-crystallin regulates βA3-proteinase as an inhibitor (6).3 However, the increasing proportion of the α-crystallin-associated trypsin/elastase inhibitor activity shifted from the water-soluble proteins to the water-insoluble protein fraction with aging (40, 41), which suggests that PTMs during aging might disrupt α-crystallin assembly in the water-soluble protein fraction and affect its chaperone ability to prevent aggregation and precipitation of crystallins. Thus, it appears that α-crystallin has dual functions in vivo to provide stability to lens crystallins by preventing their unwanted proteolysis and aggregation/denaturation and eventually keeping the lens transparent.

Although the chaperone activity of α-crystallin has been extensively investigated, the interactions of α-crystallin (as an inhibitor) and βA3 (as a proteinase) have yet to be explored. Also, as stated above, the protein-protein interactions play a major role in maintaining lens transparency. Few studies have investigated the interaction among acidic and basic human β-crystallins; however, a detailed study of the region(s) of βA3-crystallin that interact with human αA- and αB-crystallins is unknown. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to determine interacting regions of human βA3-crystallin with human αA- and αB-crystallins. Mammalian two-hybrid assay and FRET acceptor photobleaching methods were used to identify and directly visualize these sites.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

The mammalian Matchmaker two-hybrid assay kit, obtained from Clontech, was used to generate desired plasmid constructs. The pDsRed-Monomer-N and pAcGFP1-N In-Fusion ready vectors were obtained from Clontech to generate fluorescent-tagged fusion proteins. HeLa cells were a kind gift from Dr. L. Chow of the University of Alabama at Birmingham. Cell culture reagents were purchased from Invitrogen, Thermoscientific HyClone (Logan, UT), or Fisher. The restriction endonucleases, the molecular weight protein markers, and DNA markers were purchased from GE Healthcare and Promega (Madison, WI), respectively. T7 promoter, T7 terminator, and other primers used in the study were obtained from Invitrogen. The site-specific polyclonal antibodies were raised against αA- and βA3-crystallins in our laboratory as described previously (42), and the monoclonal anti-αB antibody was obtained from StressGen (Ann Arbor, MI). Molecular biology-grade chemicals were purchased from Sigma unless stated otherwise.

Analyses of Heteromers of αA Plus βA3 or αB Plus βA3 by Size-exclusion HPLC and Dynamic Light Scattering Method

Recombinant His-tagged WT βA3-, WT αA-, and WT αB-crystallins were expressed in Escherichia coli and purified using Ni2+-affinity chromatography as described earlier (43, 44). Equal amounts (0.3–0.4 mg/ml) of purified αA- or αB-crystallins were mixed with βA3-crystallin in 0.05 m phosphate buffer, pH 7.5, and incubated at room temperature for 1 h. The heteromers (WT αA plus WT βA3 or WT αB plus WT βA3) were analyzed by size-exclusion HPLC using a TSK G-3000 PWXL column. The individual crystallin homomer preparations (WT αA, WT αB, and WT βA3) were also fractionated through the same size-exclusion HPLC column for their comparative elution with the heteromers.

To determine the molecular mass of the heteromers of WT αA plus WT βA3 and WT αB plus WT βA3, the specific column fractions representing heteromer complexes in the above size-exclusion chromatography were analyzed by a multiangle dynamic light scattering method as described previously (44). A multiangle laser light scattering instrument (Wyatt Technology, Santa Barbara, CA), coupled to HPLC, was used to determine the absolute molar mass of homomers of WT αA, WT αB, and WT βA3 and the heteromers of WT αA plus WT βA3 and WT αB plus WT βA3. Briefly, protein preparations in 50 mm sodium phosphate, pH 7.4, were filtered through a 0.22-μm filter prior to their analysis. Results used 18 different angles, and the angles were normalized with the 90° detector.

Immunofluorescence Microscopy to Determine Expression and Co-localization of αA- or αB-crystallins with βA3-crystallin

HeLa cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (1× with glucose and l-glutamine without sodium pyruvate), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, penicillin (100 units/ml), and streptomycin (100 g/ml) at 37 °C with 5% CO2. One day prior to transfection, cells were seeded at 2 × 105 cells per well in 500 μl of medium in 6-well plates. Transfections were performed with the Lipofectamine (Invitrogen) using the manufacturer's protocol. Transfected cells were examined for the distribution of expressed fusion proteins. Briefly, cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized in 0.2% Triton X-100, and blocked with 3% fetal bovine serum in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) followed by incubation with monoclonal antibodies to WT αB-crystallin (at a dilution of 1:1000) and polyclonal antibodies (at a dilution of 1:500) to WT αA- or WT βA3-crystallins. The cells were then washed and incubated for 1 h in the dark with red/green fluorescein-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG or goat anti-mouse IgG secondary antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) at 1:200 dilutions. The cells were viewed with a fluorescence microscope (Zeiss Axio Plan 2) equipped with a high performance C-imaging system (Compix, Tualatin, OR).

Mammalian Two-hybrid Assay to Determine Interaction of αA- and αB-crystallins with βA3-crystallin

Cloning of WT αA-, WT αB-, and WT βA3-crystallins and Truncated Mutants of βA3-crystallin

Two sets of constructs were generated from the two vectors as follows: (a) pM vector, a vector for the DNA-binding domain of the GAL4, and (b) pVP16 vector, a vector for the transcriptional activation domain of VP16. The WT αA-, WT αB-, and WT βA3-crystallin genes were subcloned from previously prepared plasmids, pDIRECT and pCRT7/CT TOPO, respectively, into the pM and pVP16 vectors. PCR was performed for each gene using the specific primers (Table 1). All the primers were incorporated with EcoRI and XbaI restriction sites. The five deletion mutants of βA3-crystallin were generated starting with deletion of N-terminal (NT) extension (named βA3-NT), NT plus motif I (named βA3-NT + I), NT plus motifs I and II (named βA3-NT + I + II), motif III + IV (named βA3-III + IV), and motif IV (named βA3-IV) using specific primers (Table 1) and pM βA3- and pVP16 βA3-plasmid DNA as templates. The PCR products were digested by the restriction enzymes and subcloned into pM and pVP16 vectors to yield different plasmid constructs (i.e. pM-WT αA or WT αB or WT βA3, pVP16-WT αA, or WT αB or WT βA3, and all the five mutants of βA3 in pM and pVP16 vectors, respectively). All constructs were verified by DNA sequencing at the DNA core facility of the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotide primers used for generating wild-type crystallins and deletion mutants of βA3 using PCR-based mutagenesis for mammalian two-hybrid assay

| Constructs | Primers (5′–3′) |

|---|---|

| WT αA | |

| Forward | CGGATTCATGGACGTGACCATCCAGCAC |

| Reverse | GCTCTAGATTAGGACGAGGGAGCCGAGGTGGGG |

| WT αB | |

| Forward | CGGATTCATGGACATCGCCATCCACCACCCC |

| Reverse | GGCTCTAGACTATTTCTTGGGGGCTGCGGTG |

| WT βA3 | |

| Forward | CGGAATTCATGGAGACCCAGGCTGAGCAG |

| Reverse | GGCTCTAGACTACTGTTGGATTCGGCGAATC |

| βA3-(N) | |

| Forward | GGAATTCTGGAAGATAACCATCTATGATCAG |

| Reverse | GGCTCTAGACTACTGTTGGATTCGGCGAATC |

| βA3-(N + I) | |

| Forward | GGAATTCGGCGCCTGGATTGGTTATGAGCAT |

| Reverse | GGCTCTAGACTACTGTTGGATTCGGCGAATC |

| βA3-(N + I + II) | |

| Forward | GGAATTCGCTAATCATAAGGAGTCTAAGATG |

| Reverse | CTACTGTTGGATTCGGCGAATCGATTG |

| βA3-(III + IV) | |

| Forward | CGGAATTCATGGAGACCCAGGCTGAGCAG |

| Reverse | GCTCTAGACTACTCCTTATGATTAGCTGA |

| βA3-(IV) | |

| Forward | CGGAATTCATGGAGACCCAGGCTGAGCAG |

| Reverse | GCTCTAGACTATTGTATCTTCATGGAGCC |

Tissue Culture and Transfections

HeLa cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium and transfected as described above. For mammalian two-hybrid assay, all three plasmids, pM-X (0.3 μg), pVP16-Y (0.3 μg), and pG5SEAP reporter vector (0.3 μg) were co-transfected into HeLa cells. The cells were allowed to grow at 37 °C in 5% CO2. After 52 h of transfection, the secreted alkaline phosphatase (SEAP) activity was detected using the BD Great EscAPe SEAP fluorescence detection kit (Clontech). Each experiment was done in duplicate, and three independent transfections were performed. The inclusion of X and Y controls was to ensure that X or Y protein did not function autonomously as a transcriptional activator. Basal control (pM and pVP16), X-control (pM and pVP16-X), and Y-control (pM and pVIP-Y) were included. The data for basal controls were used for the conversion of SEAP activity to fold activation.

SEAP Assay

The level of SEAP activity was detected in cell culture medium after 52 h of transfection using the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, the cell culture medium was collected and centrifuged to remove any detached cells present in the cell medium. The fluorescence compound, 4-methylumbelliferyl phosphate, was used as a substrate, and its fluorescence was determined by excitation at 360 nm and emission at 449 nm. A standard linear curve was obtained using the positive placental alkaline phosphatase.

Confocal FRET Microscopy to Determine Interactions of WT αA/WT αB-crystallins with βA3-crystallin and Its Truncated Mutants

Cloning of GFP and Red Constructs with WT αA, WT αB, WT βA3, and βA3 Mutant Genes

The pDsRed-Monomer-N (designated as Red) and pAcGFP1-N (designated as GFP) In-Fusion ready vectors were obtained from Clontech to generate the desired constructs. The above mentioned vectors are linearized mammalian expression vectors that encode DsRed-Monomer, a monomeric mutant derived from the tetrametric Discosoma sp. red fluorescent protein (λex/λem = 557/585 nm) and green fluorescent protein from Aequorea coerulescens (λex/λem = 475/505 nm), respectively. The WT αA, WT αB, and WT βA3-crystallin genes and those of the above described βA3 mutants were subcloned in either Red and/or GFP vectors by following the manufacturer's instructions (Clontech). The primers were designed containing 15 nucleotide sequences (Table 2), which were homologous to the cut ends of the linearized vector at 5′ ends of sense and antisense. Briefly, PCR was performed to amplify the DNA insert using the following conditions: initial denaturation at 95 °C followed by 30 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 30 s, annealing at 60–62 °C (depending on Tm of primers) for 45 s, extension at 72 °C for 1 min, and final extension at 72 °C for 7 min. If necessary, the PCR products were purified and then ligated to the required vectors in a dry-down reaction tube containing In-Fusion enzyme (Clontech). The reaction was carried out at 37 °C for 15 min followed by incubation at 50 °C for 15 min. The reaction mixture was diluted four times and transformed to Fusion-Blue Competent cells (Clontech) using standard transformation procedure. The recombinant bacteria were selected using kanamycin (50 μg/ml). Five random colonies were picked from each of the constructs; their plasmid DNAs were isolated, and the presence of inserts was analyzed by restriction digestion using SphI and EcoRI. All the constructs were expressed as a fusion protein to the N terminus of Red and/or GFP vectors. The resulting constructs were designated as Red-WT αA, Red-WT αB, GFP-WT αB, GFP-WT βA3 and mutants of βA3 (βA3-NT), NT plus motif I (βA3-NT + I), NT plus motif I and II (βA3-NT + I + II), and motif III + IV (βA3-III + IV), motif IV (βA3-IV) as GFP-βA3-NT, GFP-βA3- (NT + I), GFP-βA3-(NT + I + II), GFP-βA3-(III + IV), and GFP-βA3-(IV), respectively. For positive control, a construct of GFP-Red fusion protein was also prepared by subcloning GFP cDNA to pAcGFP-C1 using homologous 15-nucleotide sequence. For negative control, the unlinked GFP and Red vectors were used. All constructs were verified by DNA sequencing at the DNA Sequencing Core Facility of the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

TABLE 2.

Oligonucleotide primers used for generating wild-type crystallins and deletion mutants of βA3 using PCR-based mutagenesis for FRET acceptor photobleaching

| Constructs | Primers (5′–3′) |

|---|---|

| WT αA | |

| Forward | AAGGCCTCTGTCGACATGGACGTGACCATCCAGCAC |

| Reverse | AGAATTCGCAAGCTTGGACGAGGGAGCCGAGGTG |

| WT αB | |

| Forward | AAGGCCTCTGTCGACATGGACATCGCCATCCACCAC |

| Reverse | AGAATTCGCAAGCTTTTTCTTGGGGGCTGCGGTGAC |

| WT βA3 | |

| Forward | AAGGCCTCTGTCGACATG GAGACCCAGGCTGAGCAG |

| Reverse | AGAATTCGCAAGCTTCTGTTGGATTCGGCGAATCGATTG |

| βA3-(N) | |

| Forward | AAGGCCTCTGTCGACATGTGGAAGATAACCATCTATGATCAG |

| Reverse | AGAATTCGCAAGCTTCTGTTGGATTCGGCGAATCGATTG |

| βA3-(N + I) | |

| Forward | AAGGCCTCTGTCGACATGGGCGCCTGGATTGGTTATGAG |

| Reverse | AGAATTCGCAAGCTTCTGTTGGATTCGGCGAATCGATTG |

| βA3-(N + I + II) | |

| Forward | AAGGCCTCTGTCGACATGGCTAATCATAAGGAGTCTAAG |

| Reverse | AGAATTCGCAAGCTTCTGTTGGATTCGGCGAATCGATTG |

| βA3-(III + IV) | |

| Forward | AAGGCCTCTGTCGACATGGAGACCCAGGCTGAGCAG |

| Reverse | AGAATTCGCAAGCTTCTCCTTATGATTAGCTGAACAGAT |

| βA3-(IV) | |

| Forward | AAGGCCTCTGTCGACATGGAGACCCAGGCTGAGCAG |

| Reverse | AGAATTCGCAAGCTTACTTTGTATCTTCATGGAGCC |

Tissue Culture and Transfections

HeLa cells were cultured using the protocol as described above. For the in vivo FRET, Red-WT αA/WT αB with GFP-βA3 or mutants of βA3 were co-transfected, and after incubation for 48 h, cell images in the green and red channels were acquired using a Leica SP2 confocal system outfitted to a Leica DMRXE microscope.

FRET Acceptor Photobleaching

Direct visual proof of FRET in labeled cells can be obtained by bleaching a region of the acceptor and imaging the corresponding increase in fluorescence of the donor in that region. This occurs because the energy of the donor is no longer transferred in the place where the acceptor has been effectively destroyed. Prior to FRET imaging, samples were fixed with 2% formaldehyde in PBS for 15 min, rinsed in PBS, mounted in 9:1 (v/v) glycerol/PBS containing 0.2% n-propyl gallate, and stored at −20 °C until ready for imaging. HeLa cells expressing GFP/Red fusion proteins were used to perform FRET by high intensity bleaching of a small region of the acceptor to ∼30% of the original fluorescence signal and imaging the corresponding increase in fluorescence of the donor in that region. Leica SP2 confocal system outfitted to a Leica DMRXE microscope with laser lines, dichroic mirrors, and software module, ideally designed for FRET acceptor photobleaching, was used to acquire the images with a 100× oil-immersion objective lens. GFP was excited by a 488 nm line of argon laser and the Red by a 561 nm line of helium solid state laser. Analysis of FRET data were based on the percentage increase of post-bleach donor intensity with respect to pre-bleach donor intensity. Photobleaching of Red was performed with four sequential illuminations (four frames, 1024 × 1024 resolution, line average 1) of a selected cell. Assessment of the expected nominal change in donor intensity corresponding to the nonbleached region of the acceptor provided a measure of background FRET or signal noise. FRET efficiency (designated as E) was calculated from the ratio of the GFP fluorescence evaluated before (GFPpre) and after (GFPpost) photobleaching, using Leica software and Equation 1,

where Dpre and Dpost are GFP emission before and after regional photobleaching, respectively.

RESULTS

In Vitro Interaction of WT αA- and WT αB-crystallins with WT βA3-crystallin

Interaction of WT αA- or WT αB-crystallins with WT βA3-crystallin was determined by incubating them at room temperature for 1 h followed by size-exclusion HPLC analysis to determine the appearance of heteromer peaks (i.e. WT αA plus WT βA3 and WT αB plus WT βA3) relative to homomers (WT αA, WT αB, or WT βA3 alone) (Fig. 1, A and B). The multiangle light scattering analysis of the fractions representing the heteromers peaks showed greater molecular weights than the homomers of WT αA, WT αB, and WT βA3, i.e. heteromer of WT αA + WT βA3, 1.12 × 106 Da and WT αB + WT βA3, 3.3 × 106 Da, whereas homomers of WT αA, 5 × 105 Da, WT αB, 4 × 105 Da, and WT βA3, 7.5 × 104 Da, respectively. Together, the results suggested interaction between WT αA and WT βA3 crystallins and between WT αB and WT βA3 crystallins produced heteromers.

FIGURE 1.

Size-exclusion HPLC of heteromers containing WT αA-WT βA3 (A) and WT αB-WT βA3 (B). The heteromers were generated by incubation of equal quantities of purified recombinant proteins (between 0.3 and 0.4 mg/ml) at room temperature for 1 h and subjected to size-exclusion HPLC using a TSK G-3000PWXL column. The individual protein preparations of recombinant WT αA, WT αB, and WT βA3 were also fractionated by HPLC through the same column for comparison. Peak shift in elution time of heteromers of WT αA-WT βA3 (A) and WT αB-WT βA3 (B) suggested an interaction between the two crystallins. The heteromer peaks are identified by arrows.

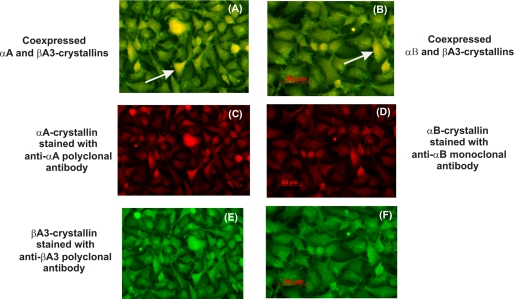

In Vivo Expression and Co-localization of αA- and αB-crystallins with βA3-crystallin

The expression of fusion proteins (αA-, αβ-, and βA3-crystallins) was verified by immunostaining (Fig. 2, C–F). The interactions between WT αA- and WT αB-crystallins with βA3-crystallin were further confirmed by dual immunolabeling of transfected HeLa cells as shown in Fig. 2, A and B, respectively. Co-localization of αA (red fluorescein (AlexaFluor 594) conjugated with goat anti-rabbit IgG) and WT βA3 (green fluorescein (AlexaFluor 488) conjugated with goat anti-rabbit IgG) was observed (Fig. 2A). Similarly, co-localization of αB- and βA3-crystallins was also observed (Fig. 2B). Together, the results suggested possible interactions of WT βA3 with WT αA- and WT αB-crystallins.

FIGURE 2.

Detection of αA-, αB-, and βA3-crystallins by immunofluorescence method in HeLa cells. HeLa cells were co-transfected with pM-WT αA/pAD-WT βA3 and pM-WT αB/pAD-WT βA3 constructs and were examined for the distribution of expressed fusion proteins. Briefly, cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and, after blocking with 1% fetal bovine serum incubated with monoclonal antibodies to αB-crystallin and polyclonal antibodies to αA- or βA3-crystallins. After extensive washing of cells with PBS, cells were incubated for 1 h with green/red fluorescein-conjugated secondary antibodies at 1:200 dilutions. The cells were viewed with a fluorescence microscope. Co-localization of WT αA-WT βA3 (A) and WT αB-WT βA3-crystallins (B) was observed suggesting possible interaction of WT βA3-crystallin with WT αA- and WT αB-crystallins. C, localization of WT αA; D, localization of WT αB; E and F, localization of WT βA3.

Analysis of Interactions between WT βA3 and WT αA/WT αB by Mammalian Two-hybrid System

Heterogeneous Interactions between WT βA3 and WT αA or WT αB

To further investigate the observed in vitro interactions of αA- and αB-crystallins with βA3-crystallin on incubation, the mammalian two-hybrid assay was used to identify specific interacting regions of βA3-crystallin. In this method, HeLa cells were transfected with WT αA or WT αB and WT βA3 or the truncated mutants of βA3 (Table 1), and their interactions were determined using the SEAP assay as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Because the assay was performed in mammalian cells, and the crystallins encoded by mammalian cDNAs were close to their native conformation including their post-translational modifications, the experimental results were relevant to in vivo physiological conditions of the crystallins.

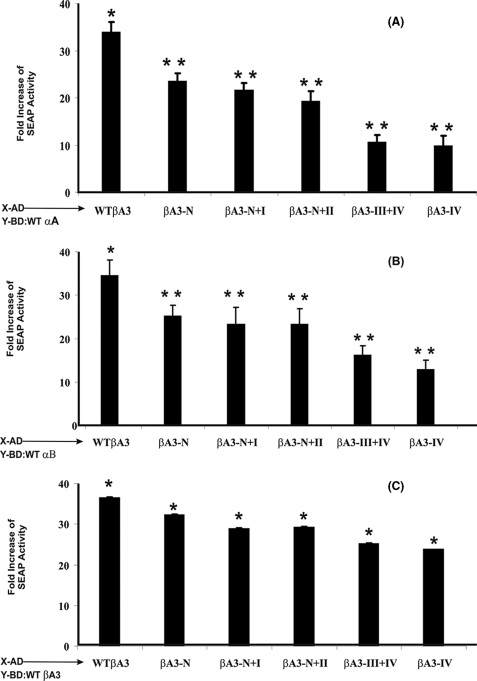

The SEAP activity was determined 52 h following transfection. The SEAP reporter gene encodes a truncated form of the placental enzyme without the membrane anchoring domain. As a result, the protein is secreted from the transfected cells into the culture medium. Therefore, the level of SEAP activity is a direct measure of protein-protein interaction because it is directly proportional to changes in intracellular concentration of SEAP mRNA and proteins. The SEAP activity was detected by 4-methylumbelliferyl phosphate fluorescence at 360 nm, and the readings were subtracted with the background and normalized with the reading of the controls (cotransfection of pM and pVP16). There was greater than 20-fold increase in SEAP activity (Fig. 3, A and B) for WT crystallins (i.e. WT αA-, WT αB-, and WT βA3-crystallins) compared with negative controls. The overall interaction between WT αA and WT βA3 (Fig. 3A) was slightly higher than between WT αB and WT βA3 (Fig. 3B). The same level of interaction was also observed when the two protein pairs were cloned in reverse order, i.e. WT βA3 and WT αA or WT βA3 and WT αB (data not shown). The results suggested that the interactions were not vector-specific.

FIGURE 3.

Protein-protein interactions between WT βA3 and its truncated mutants with WT αA- and WT αB-crystallins as expressed by the fold increase of SEAP activity during mammalian two-hybrid assay. The WT αA/WT αB- and WT βA3-crystallins or βA3 truncated mutants (fused into pM containing DNA binding domain and pVP16 vector containing activating domain) along with pG5SEAP reporter vector were co-transfected into HeLa cells. The SEAP activity was determined in the culture medium using 4-methylumbelliferyl phosphate as substrate. The values reported are averages from three independent transfections (± S.D.). Statistical significance was calculated by the paired t test. Significant decrease were observed for the mutants (**, p < 0.005) from WT (*, p < 0.05). A, heterogeneous interactions between WT βA3 and its truncated mutants with WT αA-crystallin. Mutants lacking motif III and IV (βA3-III + IV mutant), and motif IV alone (βA3-IV mutant) showed significant decrease in interaction with WT αA compared with interaction between WT αA and WT βA3, suggesting that the interaction sites in βA3 with αA were mostly localized in motifs III and IV. B, heterogeneous interactions between WT βA3 and its truncated mutants with WT αB-crystallin. Compared with activity with WT αB and WT βA3, the SEAP activity showed relatively greater decrease irrespective of the regions that were deleted in the βA3-crystallin. This suggested that multiple sites of βA3-crystallin were involved in interaction with WT αB-crystallin. C, homogeneous interactions between WT βA3-crystallin and its truncated mutants. The SEAP activity showed relatively strong interactions between WT βA3 and its truncated mutant proteins compared with interactions of WT αA- or WT αB-crystallins with the truncated mutants of βA3-crystallin. The results suggested that among βA3-crystallin species, the intrasubunit interaction sites might be different from the intersubunit interaction sites.

Heterogeneous Interactions between WT αA-crystallin and Truncated Mutants of βA3-crystallin

The SEAP activities for heterogeneous crystallin systems that included WT αA co-transfected with WT βA3 showed significant interactions between them.

The SEAP activity showed that the interactions between the WT αA-crystallin and the five βA3 truncated mutants gradually decreased as the motifs of the βA3-crystallin were sequentially deleted (βA3-NT, 74%;, βA3-NT + I, 59%; βA3-NT + I + II, 50%; βA3-III + IV, 26%; and βA3-IV, 24%) (Fig. 3A). This suggested that each of the motifs of βA3 plays a role in interaction with αA-crystallin. Compared with WT βA3, the truncation of the N-terminal arm in the crystallin did not significantly affect the interaction between the αA- and βA3-crystallins. However, the deletion of motif IV resulted in significant loss of interaction as suggested by the SEAP activity. In addition, compared with the truncation of N-terminal domain (i.e. N-terminal extension plus motifs I and II), the truncation of C-terminal domain (i.e. motifs III and IV) in βA3-crystallin resulted in a significant loss in its interaction with αA-crystallin. Together, the results suggested that the regions of motifs III and IV of βA3 interact with αA-crystallin. However, the conformations of βA3-crystallin also play a role in such protein-protein interaction.

Heterogeneous Interactions of WT αB with WT βA3 and Truncated Mutants of βA3

Unlike interaction between WT αA- and WT βA3-crystallins, the SEAP activity data of interactions of WT αB and βA3 showed almost equivalent and significant loss irrespective of the regions of N-terminal arm or motifs that were deleted in βA3-crystallin (Fig. 3B). The following levels of SEAP activity were observed: βA3-NT, 62%; βA3-NT + I, 65%; βA3-NT + I + II, 60%; βA3-III + IV, 36%; and βA3-IV, 34%. Together, the results suggested that multiple sites of βA3-crystallin were involved in interaction with WT αB-crystallin.

Homogeneous Interaction between WT βA3 and Its Truncated Mutants

The SEAP assay showed relatively strong interactions between WT βA3 and its truncated mutant proteins compared with interactions of WT βA3 with WT αA- or WT αB-crystallins (Fig. 3C). The truncation of N-terminal arm in βA3 did not significantly change (SEAP activity 83%) the level of its interaction with WT βA3. However, the truncation of either the N-terminal domain (SEAP activity 78%) or the C-terminal domain (SEAP activity 60%) of βA3 resulted in loss of interactions with WT crystallin, but the loss in the SEAP activity was lower than those observed between WT βA3 and WT αA or WT αB-crystallins (Fig. 3, A and B). Together, these results suggested that the intrasubunit interactions in the homomers of WT βA3 and its truncated species also occur, and these interaction sites might be different from those observed during intersubunit interactions in heteromers (i.e. WT βA3 and its truncated species and αA- or αB-crystallins).

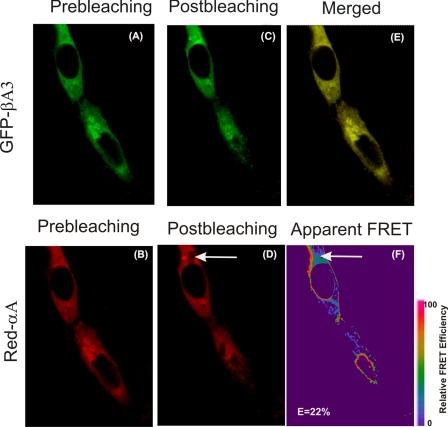

Determination of Interaction between WT αA- or WT αB-crystallins with WT βA3 and Its Truncated Mutants by FRET Acceptor Photobleaching Method

To further confirm the above observed interaction results between WT αA- or WT αB-crystallins with WT βA3 and its truncated mutant proteins, the in vivo FRET acceptor photobleaching method was used. This method involves distance-dependent (20–60 Å) interaction between excited fluorescence dye molecules from a donor molecule to an acceptor molecule without exciting photons. As a positive control, a GFP-Red fusion protein separated by 10 amino acid linkers was used. The region of interest in cells expressing fusion proteins was photobleached to 30% of original intensity. GFP and Red images were recorded before and after acceptor photobleaching. The cells transfected with the positive control showed a FRET efficiency (represented by E) with an average of ∼15% after photobleaching (data not shown) compared with the negative control. In the negative control, cells transfected with unlinked GFP and Red constructs were used, which did not show any change in GFP fluorescence after regional bleaching with an E value of <1%.

Figs. 4–7 show images acquired before and after regional photobleaching when different combinations of WT βA3 or its mutants were co-transfected with WT αA- or WT αB-crystallins. In each set of images in Figs. 4–7, panel D identified the bleached area by an arrow and panel F identified the apparent FRET (identified by an arrow). Significant increase in GFP fluorescence after selective photobleaching between αA/βA3 and αB/βA3 crystallins was observed suggesting FRET occurrence (Figs. 4 and 6). Cells transfected with WT crystallin pairs (WT αA/WT βA3 and WT αB/WT βA3) showed an average of ∼9% E value but as high as 22–25% were observed in transfected cells compared with negative control.

FIGURE 4.

In vivo detection of interaction between WT αA- and WT βA3-crystallins by FRET acceptor photobleaching microscopic method. HeLa cells, co-expressing Red-WT αA and GFP-WT βA3 crystallins, were analyzed by a confocal microscope. A shows GFP channel image of HeLa cells co-transfected with pairs of GFP and Red fusion crystallins. B shows Red channel images of cells co-transfected with pairs of GFP and Red fusion crystallins. Images were acquired before (A and B) and after photobleaching (C and D). A nonbleached region (B) and a corresponding bleached region (D, shown by an arrow) were used in the data analysis compared with unbleached region of the cell as negative control. FRET efficiencies (percentage) for the interaction between two crystallin partners were calculated as described under “Experimental Procedures,” and the FRET intensity (F, shown by an arrow) is shown in pseudo color. The FRET intensity as percent represents the fraction of interacting donor molecules. E showed the co-localization of Red- and GFP-labeled constructs transfected into HeLa cells. Results suggested significant interaction between WT αA and WT βA3-crystallins.

FIGURE 5.

In vivo detection of interactions of WT βA3 and its mutants with WT αA by FRET acceptor photobleaching confocal microscopic method. Representative confocal microscopic images of HeLa cells are shown that were co-transfected with Red-WT αA and GFP-WT βA3 or its truncated mutants. Photobleaching FRET was performed as described in the legend to Fig. 4. A, GFP channel image of cells co-transfected with pairs of GFP and Red fusion crystallins. B, red channel images of cells co-transfected with pairs of GFP and Red fusion crystallins. Images were acquired before (A and B) and after photobleaching (C and D). A nonbleached region (B) and a corresponding bleached region (D, identified by arrows) were used in the data analysis. FRET efficiencies (percentage) for the interaction between crystallins were calculated as described under “Experimental Procedures.” F, FRET intensity is shown by an arrow in pseudo color. E, co-localization of Red- and GFP-labeled constructs transfected into HeLa cells. Results suggested that the motifs III and IV of βA3-crystallin showed maximum interaction with αA-crystallin.

FIGURE 6.

In vivo detection of interactions between WT αB- and WT βA3-crystallins by FRET acceptor photobleaching confocal microscopic method. HeLa cells, co-transfected with Red-WT αB and GFP-WT βA3 crystallins, were analyzed by a confocal microscope. Photobleaching FRET was performed as described in the legend to Fig. 4. A, GFP channel image of cells co-transfected with a pair of GFP and Red fusion crystallins. B, red channel images of cells co-transfected with a pair of GFP and Red fusion crystallins. Images were acquired before (A and B) and after photobleaching (C and D). A nonbleached region (B) and a corresponding bleached region (D, identified by an arrow) were used for the data analysis compared with unbleached region of the cell as negative control. FRET efficiencies (percentage represented as E) for the interaction between crystallins were calculated as described under “Experimental Procedures.” F, FRET intensity (shown by an arrow) is in pseudo color. The FRET intensity as percentage represents the fraction of interacting donor molecules. E, co-localization of Red- and GFP-labeled constructs transfected into HeLa cells. Results suggested significant interaction between WT αB and WT βA3-crystallins.

FIGURE 7.

In vivo detection of interactions of WT βA3 and its mutants with WT αB by FRET acceptor photobleaching confocal microscopic method. Representative confocal microscopic images of HeLa cells are shown that were co-transfected with Red-WT αB and GFP-WT βA3 or its truncated mutants. Photobleaching FRET was performed as described in the legend to Fig. 4. A, GFP channel image of cells co-transfected with pairs of GFP and Red fusion crystallins. B, red channel images of cells co-transfected with pairs of GFP and Red fusion crystallins. Images were acquired before (A and B) and after photobleaching (C and D). A nonbleached region (B) and a region similar to the bleached region (D, shown by arrows) were used in the data analysis. FRET efficiencies (percentage) for the interaction between crystallins were calculated as described under “Experimental Procedures.” F, FRET intensity (identified by an arrow) is shown in pseudo color. The FRET intensity (E) as percent represents the fraction of interacting donor molecules. E, co-localization of Red- and GFP-labeled constructs, transfected into HeLa cells, and visualized. Results suggested that motifs II and III of βA3-crystallin were critical for the interaction with αB-crystallin.

Heterogeneous Interactions between WT αA-crystallin and WT βA3 and Its Truncated Mutants

Fig. 5 shows FRET results when the cells were co-transfected with WT αA-crystallin and WT βA3 or its truncated mutant proteins. The following E values were observed (Fig. 5): N-terminal arm (NT) truncation, E = 23%; NT plus motif I, E = 24%; NT plus motifs I and II, E = 13%; motifs III plus IV, E = 0.7%; and motif IV, E = 0.1%. Together, the results showed that the deletions of N-terminal extension or N-terminal extension plus motif I of βA3 showed no significant effect on its interaction with WT αA crystallins as the E values (E ∼22–24%) were at almost the same levels as between WT crystallin pairs (i.e. WT αA and WT βA3). However, about a 50% decrease in E value (13%) compared with WT βA3 (E = 22%) was observed if the motif II was also deleted along with the N-terminal extension plus motif I. This suggested a significant conformation change resulting in decrease in protein-protein interaction on such a deletion. Most dramatic decrease in E values was observed on truncation of motifs III plus IV (E = 0.7%) or the motif IV (E = 1%), suggesting a lack of interaction between these truncated βA3 mutants and WT αA-crystallin. Furthermore, the truncation onwards after motif II in βA3-crystallin resulted in expression of the fusion proteins in both nucleus and cytoplasm, suggesting that either these fusion proteins were able to enter the nucleus or the freshly expressed crystallins were in monomeric state. Together, the FRET results suggested that mainly regions of motifs III and IV of βA3-crystallin participate in interaction with αA-crystallin.

Heterogeneous Interactions of WT αB with WT βA3 and Truncated Mutants of βA3

The in vivo FRET results of interaction between WT αB-crystallin and WT βA3-crystallin or its mutant proteins are shown in Figs. 6 and 7. On photobleaching between WT αB- and WT βA3-crystallins, an E value of 17% was observed (Fig. 6), whereas the following E values were observed between WT αB and βA3 mutants (Fig. 7): NT truncation, E = 7%; NT plus motif I, E = 12%; NT plus motifs I and II, E = 1%; motifs III plus IV, E = 0.2%; and motif IV, E = 4%. Compared with the interaction of WT αB with WT βA3 (E = 17%), the truncation of either NT or NT plus motif I resulted in greater than 50% loss (E = 7%) and 30% loss (E = 12%), respectively (Fig. 7). However, the truncation of N-terminal extension plus motifs I and II in βA3 resulted in negligible FRET (E = 1%) with WT αB, suggesting that the presence of motif II of the N-terminal domain of the βA3 is critical for its interaction with αB-crystallin. Similarly, the truncation of motifs III and IV in βA3 also exhibited negligible FRET (E = 0.2%) after selective photobleaching, and also resulted in the expression of fusion proteins in both nucleus and cytoplasm (Fig. 7), Although the truncation of motif IV alone in βA3 showed co-expression with WT αB in cytoplasm, it showed reduced FRET (E = 4%) compared with the FRET value of 17% between WT βA3 and WT αB-crystallins. Together, the results suggest that the major interaction regions of βA3-crystallin with αB are localized in motifs II and III, whereas the minor interaction regions in the N-terminal extension and motifs I and IV.

DISCUSSION

Human lens transparency is maintained by short range order of crystallins that includes specific crystallin-crystallin interactions (3–4). However, the molecular nature of these short range homologous and/or heterologous interactions among α-, β-, and γ-crystallins in the human lens is still not well understood. Analyses of aging and cataractous lenses have identified PTMs that result in loss of transparency (2). Truncation, which is a major PTM and can be the consequence of either genetic aberration (29–31) or activation of proteases (45), is believed to alter these short range interactions that in turn influence lens protein solubility and increase in light scattering, eventually causing lens opacification (2, 46).

The present literature suggests that β-crystallin interacts with αA/αB-crystallins (6, 9–10) and forms supramolecular assembly that plays a critical role in the maintenance of lens transparency through an unknown mechanism. Previous studies have shown interactions between acidic and basic β-crystallins and its role in keeping the hetero-oligomers soluble (47). The focus of our study was to identify the regions of βA3-crystallin that interact with αA- and αB-crystallins. The rationale of the study was as follows: (a) β-crystallins form hetero-oligomers with αA/αB that seems to exist in vivo (6); (b) βA3-crystallin proteinase activity seems to be regulated in vivo by αA- and αB-crystallins as inhibitors, and the enzyme existed in an inactive state in the α-crystallin fraction (6); and (c) our preliminary results suggest that the enzyme active site in βA3 might be localized in the motifs III and IV. Therefore, establishing interaction sites between βA3-crystallin and αA/αB-crystallins would provide an insight in understanding the super-molecular assembly of crystallins in maintaining the lens transparency.

In this study, we used recombinant WT crystallins and different truncated βA3 mutants, along with two advanced techniques (i.e. mammalian two-hybrid and confocal FRET microscopic methods) to assess crystallin-crystallin interactions in living cells. The availability of five deletion mutants of βA3-crystallin greatly facilitated the identification of the region(s) of the βA3 crystallin that interact with αA- and αB-crystallins. Nevertheless, truncated βA3-crystallin mutants will have altered folding compared with the native β-crystallin; however, our previous study (42) showed that none of the truncations in the crystallin resulted in “random-coiled” structure. Because the purpose of the study was to identify regions of βA3-crystallin that interact with αA/αB crystallins, the approach in this study was to delete different regions of βA3 and to determine interaction of the resulting mutants with αA- and αB-crystallins. The crystal structures of human truncated βB1 and WT βB2 are known, which showed intramolecular pairing of domains in former and swapping in the latter. Thus, N- and C- terminal domains of βA3 (which shares 45–60% sequence identity of βB1-crystallin) containing two greek key motifs upon deletion are expected to interact with other greek key motifs in a different manner than the native state. Also, in our recent publication, we have shown the molecular model of βA3 (42) using the coordinates from the Protein Data Bank entry of truncated βB1-crystallin. Based on the proposed structure, it was suggested that truncation of motif IV would not only disrupt the noncovalent interactions with the N-terminal domain but also destabilize the C-terminal domain to some extent. Additionally, in this study, protein-protein interactions were determined in HeLa cells, and the cellular environment would allow expression as well as proper folding of βA3 mutant proteins. Furthermore, none of the mutant proteins exhibited aggregation/precipitation as has been reported for certain mutant crystallins by other investigators using similar FRET analysis (17–20). This further rationalized our above experimental approach. The major expected outcome of the study was to localize the binding site of αA and αB to βA3, and also to elucidate the potential importance of truncations in βA3 during its interaction with αA- and αB-crystallins in the diseased state. For example, the autosomal dominant lamellar (32) and zonular (31) cataracts are because of deletion of 3 bp in tyrosine corner and the deletion of motifs II and III in βA3, respectively. Additionally, truncations in βA3-crystallin have been shown to occur in vivo as genetic defects associated with human inherited cataract (31–32). It is believed that these in vivo truncations in βA3-crystallin lead to structural changes that disrupt its heterogeneous interactions with other β-crystallins causing protein aggregation and cross-linking and finally lens opacity. Because our previous report (42) showed that the C-terminal domain (motifs III and IV) was essential for a proper folding and stability of the N-terminal domain (motifs I and II) of βA3-crystallin, and might be involved in stabilizing the crystallin structure, a mutant lacking connecting peptide was not included in this present study.

As stated above, the interactions among crystallins in aging and cataractous human lenses have been mainly studied by using in vitro techniques (11–17). However, the advent of recent advances in imaging techniques allowed us to determine the molecular interaction between different regions of crystallins in live cells. The results of mammalian two-hybrid and FRET methods in this study provide direct visual evidence regarding the regions of βA3 that interact with αA- and αB-crystallins.

Initially, the in vitro interaction between WT βA3 and WT αA/WT αB-crystallins was determined by a size-exclusion HPLC method. The protein elution profiles showed that the heteromers of WT βA3 plus WT αA and WT βA3 plus WT αB eluted as separate peaks compared with the homomers of WT βA3-, WT αA-, or WT αB-crystallins (Fig. 1, A and B). These peak fractions of heteromers on the multiangle light scattering analysis showed higher molecular mass than those of homomers of WT βA3-, WT αA-, or WT αB-crystallins, which suggested interaction between WT βA3 and WT αA/WT αB on incubation. Analysis of co-localization of WT βA3 crystallin with WT αA- or WT αB-crystallins (using specific antibodies) in HeLa cells further suggested possible interactions between the crystallins (Fig. 2, A and B). Next, we used mammalian two-hybrid and acceptor photo-bleaching FRET analyses to specifically determine such interactions under in vivo physiological conditions in living cells. Both the methods eliminated the need to purify proteins, which sometimes changes protein conformations. However, the FRET assay is superior to the two-hybrid assay method because neither reporter gene assay nor cell lysis is required and therefore provides direct and relatively accurate interaction results. Indeed, this was found to be true in the results described above.

This study demonstrates for the first time that in vivo heteromers containing WT αA/WT αB and WT βA3 or its truncated mutants showed differential distribution in live cells. Furthermore, the specific interactions among these crystallins in both homogeneous and heterogeneous states were shown. Although co-transfection of WT αA/WT αB mediated the cytoplasmic expression of WT βA3 and its mutants that lacked the N-terminal arm, motifs I and II (Figs. 5 and 7), and significant protein-protein interactions between them, the loss of motifs III and IV showed mixed expression even in the presence of WT αA/WT αB (Figs. 5 and 7). One interesting finding was that βA3-NT + I + II mutant showed both nuclear and cytoplasmic expression and the E value of 13% when co-transfected with WT αA (Fig. 5), and only cytoplasmic expression with minimal interaction (E = 1%) when co-transfected with WT αB (Fig. 7). Truncation of motifs III and IV in βA3 also showed similar expression irrespective of presence of WT αA or WT αB (Figs. 5 and 7). This suggests that co-localization of two proteins observed in a living cell using conventional fluorescence microscopy might not be close (within 20–60 Å) and thus cannot interact directly. This limitation could be very well overcome by FRET acceptor photobleaching whose resolution is within 1–10 nm (a distance generally shown for intermolecular interaction).

The two-hybrid and FRET assays showed strong interactions of WT αA/WT αB with WT βA3 compared with WT αA/WT αB and the mutants of βA3. An earlier report has also studied interactions between α-, β-, and γ-crystallin; however, interaction with βA3 crystallin was not included (23). Both SEAP activity in mammalian two-hybrid and the FRET assays showed that relative to truncation of N-terminal domain (N-terminal extension plus motifs I and II), the truncation of C-terminal domain (comprising of motifs III and IV) in βA3-crystallin resulted in a significant loss in its interaction with αA-crystallin. However, FRET data showed negligible interaction upon truncation of C-terminal domain than truncation of N-terminal domain compared with the mammalian two-hybrid assay. The most likely explanation could be that the mammalian two-hybrid assay represents the cumulative interactions in cell culture medium and cannot differentiate between a transient and weak interaction; thus, a higher measure of interaction can be observed. Also, FRET demonstrates direct intermolecular interaction and is dependent on fluorophore orientation. Therefore, reduced FRET could be due to either no direct interaction or some transient modeling of this mutant protein occurred, which altered protein orientation. Since the FRET results of WT αA with βA3 mutants with truncation of either N-terminal arm motifs I and II did not show significant decrease in interaction, it suggests that the conformational changes because of deletions of these specific regions did not significantly influence the protein-protein interaction. On interaction of βA3 with deletions of motifs III and IV with WT αA, both two-hybrid and FRET assays showed drastic decrease in interaction values (i.e. SEAP or E values). This suggested that the interaction region in βA3 was mostly localized in motifs III and IV (residues 124–215). Our previous report on characterization of these mutants also showed that the truncation of motifs III and IV in human lens βA3-crystallin destabilized its structure, and the N-terminal domain was relatively more stable than the C-terminal domain (42). Therefore, this previous finding and the one in this study suggest that αA-crystallin stabilizes βA3-crystallin by interacting with the four β-strands in motifs III and IV. Also, it appears that loss of eight β-strands in the C-terminal domain of βA3 (based on sequence identity between acidic and basic β-crystallins), which were shown to be important in dimerization of βB2-crystallin (48), is also critical in interaction with αΑ/αB-crystallins. This further explains the preferential cleavage of only the N-terminal regions in the βA3-crystallin early in life (49) and during aging (50). However, at present we do not know whether the interaction between βA3- and αA-crystallins begins in the lens of a newborn.

The results from two-hybrid assay of interactions between WT αB and WT βA3 and its truncated mutant proteins showed relatively greater loss in their interaction irrespective of the regions that were truncated in βA3-crystallin, (i.e. NT deletion, 62%; N-terminal domain deletion, 60%; and C-terminal domain deletion, 36%) compared with WT αA (i.e. NT deletion, 74%; N-terminal domain deletion, 50%; and C-terminal domain deletion, 26%). The protein-protein interaction between WT αB and different mutants of βA3 seen in FRET studies was consistent with two-hybrid assay results, except for the mutant protein lacking NT, motifs I and II, which showed only a 1% interaction (FRET studies) compared with the 40% interaction (in two-hybrid assay) with WT αB (Fig. 3B). Because the FRET microscopy is a distance-dependent detection method, any change in transient conformation leading to a greater distance between the two interacting proteins will influence FRET. This could explain a decrease in FRET efficiency in this mutant compared with SEAP activity. Also, our data suggest that the presence of motif III in βA3 is critical for interaction with WT αB, as mutants lacking motifs III and IV showed negligible interaction (E = 0.2%) compared with 4% interaction with mutants lacking only motif IV. Therefore, most likely the interaction sites between βA3 and αB involve motif II and III. This shows that the interacting regions in βA3-crystallin for αA- and αB-crystallins are different. Additionally, the FRET results suggested that the minor interaction sites exist in the regions of NT and motifs I and IV of βA3-crystallin for αB-crystallin.

Compared with heterogeneous interaction between WT βA3 and WT αA/WT αB, homogeneous interactions between WT βA3 and its truncated mutants were relatively stronger. This could be due to intersubunit domain interactions. It is believed that for dimerization or oligomerization of β-crystallins, the interaction sites are mostly β-sheets formed by two or more β-sheets as shown in βB2 structure by x-ray diffraction studies (48). Because 16 β-strands are distributed equally in four greek key motifs, the truncation of each motif in our study is expected to influence the crystallin-crystallin interactions. However, the final protein conformation and orientation acquired in natural environment regulate the protein-protein interaction.

As stated above, the importance of the N-terminal domain, motif I to IV in the structural stability of the βA3-crystallin, was identified in our recent study (42). This earlier study showed that the loss of 21 and 22 N-terminal amino acids and the N-terminal extension resulted in oligomerization (aggregates with masses of 259–267 kDa) but no changes in secondary structure; however, the loss of motifs III and IV resulted in significant changes in solubility properties, β-sheet structural content, and tertiary and quaternary structures. This is parallel with our present findings where interaction between αA/αB and βA3 is not lost upon N-terminal arm truncation. The deletion of motif IV in βA3 in our previous study resulted in recovery of an insoluble protein, but the mutant with deleted motifs III and IV was partially soluble, suggesting that motif IV apparently plays a critical role in keeping the protein properly folded via interaction with the N-terminal domain (motifs I and II) (42). The reduced or negligible interaction between αA/αB with the mutant lacking motifs III and IV in this study correlates to the biophysical properties of these mutants observed previously. Together, our studies clearly identified the importance of motif III and IV in its structural stability and their role in interaction with WT αA/WT αB.

Acknowledgments

We thank Martha Robbins for expert help in preparation of the manuscript.

This work was supported in whole, or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants EY06400, P30 EY0303, and P50 AT00477 (to C. Weaver). This work was also supported by a faculty development grant from the University of Alabama at Birmingham and the EyeSight Foundation of Alabama.

3 O. P. Srivastava, unpublished results.

- FRET

- fluorescence resonance energy transfer

- WT

- wild type

- GFP

- green fluorescent protein

- HPLC

- high pressure liquid chromatography

- PBS

- phosphate-buffered saline

- NT

- N-terminal

- PTM

- post-translational modification

- SEAP

- secreted alkaline phosphatase.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andley U. P. ( 2007) Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 26, 78– 98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bloemendal H., de Jong W., Jaenicke R., Lubsen N. H., Slingsby C., Tardieu A. ( 2004) Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 86, 407– 485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ponce A., Sorensen C., Takemoto L. ( 2006) Mol. Vis. 12, 879– 884 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhat S. P. ( 2004) Exp. Eye Res. 79, 809– 816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Srivastava O. P., Srivastava K. ( 1999) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1434, 331– 346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Srivastava O. P., Srivastava K., Chaves J. M. ( 2008) Mol. Vis. 14, 1872– 1885 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Delaye M., Tardieu A. ( 1983) Nature 302, 415– 417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xia J. Z., Wang Q., Tatarkova S., Aerts T., Clauwaert J. ( 1996) Biophys. J. 71, 2815– 2822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weinreb O., van Rijk A. F., Dovrat A., Bloemendal H. ( 2000) Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 41, 3893– 3897 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krivandin A. V., Muranov K. O., Ostrovsky M. A. ( 2004) Dokl. Biochem. Biophys. 394, 1– 4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liang J. J., Liu B. F. ( 2006) Protein Sci. 15, 1619– 1627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sreelakshmi Y., Sharma K. K. ( 2006) Mol. Vis. 12, 581– 587 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carver J. A., Lindner R. A., Lyon C., Canet D., Hernandez H., Dobson C. M., Redfield C. ( 2002) J. Mol. Biol. 318, 815– 827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ghosh J. G., Clark J. I. ( 2005) Protein Sci. 14, 684– 695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ponce A., Takemoto L. ( 2005) Mol. Vis. 11, 752– 757 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kamei A., Matsuura N. ( 2002) Biol. Pharm. Bull. 25, 611– 615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Song S., Hanson M. J., Liu B. F., Chylack L. T., Liang J. J. ( 2008) Mol. Vis. 14, 1282– 1287 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu B. F., Liang J. J. ( 2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 2624– 2630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu B. F., Liang J. J. ( 2005) Mol. Vis. 11, 321– 327 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu B. F., Anbarasu K., Liang J. J. ( 2007) Mol. Vis. 13, 854– 861 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu B. F., Liang J. J. ( 2007) FEBS Lett. 581, 3936– 3942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu B. F., Liang J. J. ( 2008) J. Cell Biochem. 104, 51– 58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fu L., Liang J. J. ( 2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 4255– 4260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fu L., Liang J. J. ( 2003) Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 44, 1155– 1159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Srivastava O. P., Kirk M. C., Srivastava K. ( 2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 10901– 10909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harrington V., McCall S., Huynh S., Srivastava K., Srivastava O. P. ( 2004) Mol. Vis. 10, 476– 489 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harrington V., Srivastava O. P., Kirk M. ( 2007) Mol. Vis. 13, 1680– 1694 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang Z., Smith D. L., Smith J. B. ( 2003) Exp. Eye Res. 77, 259– 272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ma Z., Hanson S. R., Lampi K. J., David L. L., Smith D. L., Smith J. B. ( 1998) Exp. Eye Res. 67, 21– 30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lu S., Zhao C., Jiao H., Kere J., Tang X., Zhao F., Zhang X., Zhao K., Larsson C. ( 2007) Mol. Vis. 13, 1154– 1160 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cohen D., Bar-Yosef U., Levy J., Gradstein L., Belfair N., Ofir R., Joshua S., Lifshitz T., Carmi R., Birk O. S. ( 2007) Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 48, 2208– 2213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ferrini W., Schorderet D. F., Othenin-Girard P., Uffer S., Héon E., Munier F. L. ( 2004) Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 45, 1436– 1441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rajan S., Chandrashekar R., Aziz A., Abraham E. C. ( 2006) Biochemistry 45, 15684– 15691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Feil I. K., Malfois M., Hendle J., van Der Zandt H., Svergun D. I. ( 2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 12024– 12029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ortwerth B. J., Olesen P. R. ( 1992) Exp. Eye Res. 54, 103– 111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sharma K. K., Olesen P. R., Ortwerth B. J. ( 1987) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 915, 284– 291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kamradt M. C., Lu M., Werner M. E., Kwan T., Chen F., Strohecker A., Oshita S., Wilkinson J. C., Yu C., Oliver P. G., Duckett C. S., Buchsbaum D. J., LoBuglio A. F., Jordan V. C., Cryns V. L. ( 2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 11059– 11066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kamradt M. C., Chen F., Sam S., Cryns V. L. ( 2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 38731– 38736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Srivastava O. P., Ortwerth B. J. ( 1983) Exp. Eye Res. 36, 363– 379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Srivastava O. P., Ortwerth B. J. ( 1989) Exp. Eye Res. 48, 25– 36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ortwerth B. J., Sharma K. K., Olesen P. R. ( 1992) Exp. Eye Res. 54, 573– 581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gupta R., Srivastava K., Srivastava O. P. ( 2006) Biochemistry 45, 9964– 9978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Srivastava O. P., Srivastava K. ( 2003) Mol. Vis. 9, 644– 656 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gupta R., Srivastava O. P. ( 2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 44258– 44269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Robertson L. J., David L. L., Riviere M. A., Wilmarth P. A., Muir M. S., Morton J. D. ( 2008) Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 49, 1016– 1022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Takemoto L., Sorensen C. M. ( 2008) Exp. Eye Res. 87, 496– 501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Marín-Vinader L., Onnekink C., van Genesen S. T., Slingsby C., Lubsen N. H. ( 2006) FEBS J. 273, 3172– 3182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bax B., Lapatto R., Nalini V., Driessen H., Lindley P. F., Mahadevan D., Blundell T. L., Slingsby C. ( 1990) Nature 347, 776– 780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lampi K. J., Ma Z., Shih M., Shearer T. R., Smith J. B., Smith D. L., David L. L. ( 1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 2268– 2275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Srivastava O. P., Srivastava K., Harrington V. ( 1999) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 258, 632– 638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]