Abstract

Disturbances in emotional functioning are a major cause of persistent functional disability in schizophrenia. However, it is not clear what specific aspects of emotional functioning are impaired. Some studies have indicated diminished experience of positive affect in individuals with schizophrenia, while others have not. The current study assessed emotional responses by 34 individuals with schizophrenia and 35 demographically matched healthy participants to 131 images sampling a wide range of emotional arousal and valence levels. Ratings of affective response elicited by individual images were highly correlated across the groups (r’s > .90), indicating similar emotional experiences at the moment of stimulus exposure. However, the data did not indicate strong relationships between ratings of the emotional impact of the images and most measures of day-to-day emotional processing. These results demonstrate that individuals with schizophrenia report “normal” emotional responses to emotional stimuli, and thus suggests that deficits in emotional functioning associated with the disorder are likely to occur further downstream, and involve the effective integration of emotion and cognition for adaptive functioning in areas such as goal-setting, motivation, and memory.

Keywords: Emotional experience, schizophrenia, emotional processing, anhedonia

1. Introduction

Disturbances in emotional processing in individuals with schizophrenia are related to persistent functional disability (cf. Blanchard, Mueser & Bellack, 1998; Herbener & Harrow, 2004; Hooker & Park, 2002), and may underlie negative and deficit symptoms such as avolition and anhedonia. However “emotional processing” is a broad term, encompassing multiple aspects of emotion that may or may not be impaired. Many studies of emotion processing in schizophrenia have focused on abnormalities in facial emotion perception (Kohler, Bilker, Hagendoorn, Gur, and Gur, 2000; Mueser, Penn, Blanchard and Bellack, 1997) or affective expression (Aghevli, Blanchard and Horan, 2003; Berenbaum & Oltmanns, 1992; Herbener and Harrow, 2004; Kring & Neale, 1996). Findings generally indicate impairment in both aspects of emotional functioning, although data on their relationship is inconsistent.

Data is less clear on whether individuals with schizophrenia experience abnormalities in immediate emotional experience, as past studies have provided inconsistent results (Blanchard, Bellack & Mueser, 1994; Curtis, Lebow, Lake, Katsanis & Iacono, 1999; Hempel, Tulen, van Beveren, van Steenis, Mulder & Hengeveld, 2005; Kring & Neale, 1996; Paradiso, Andreasen, Crespo-Facorro, O’Leary, Watkins, Poles Ponto, & Hichwa, 2003; Schlenker, Cohen & Hopmann, 1995; Takahashi, Koeda, Oda, Matsuda, Matsushima, Asai, & Okubo, 2004; Taylor, Phan, Britton, & Liberzon, 2005). Several studies that assessed affective responses to emotional images “in the moment” found no differences in ratings of personal emotional experience between schizophrenia and healthy samples (Hempel, et al, 2005; Schlenker et al, 1995; Takahashi et al, 2004). However, other studies using the same types of stimuli have found that subjects with schizophrenia report less positive emotional responses to positively valenced images (Paradiso et al, 2003; Taylor et al, 2005). This inconsistency could be due to a number of different aspects of the studies (methods differences, subject differences). Alternatively, individuals with schizophrenia may have difficulties in experiencing certain intensities of emotion, but not others, and thus differences in the characteristics of the stimuli used to elicit emotions across studies could account for the disparity in previous findings.

The current study tested whether individuals with schizophrenia differ from healthy individuals in their emotional responses to stimuli across a wide range of valence and arousal. This approach makes it possible to determine whether there are specific levels of valence or arousal that might be differentially affected by illness status (e.g., individuals with schizophrenia might be particularly unresponsive to very positive emotional stimuli, or to positive more than negative stimuli). A second aim of this study was to examine the relationship between reports of immediate emotional experience while viewing emotional images with self-reported level of anhedonia and other aspects of emotional functioning (e.g., emotional face perception, emotional expression). Differences between self-report of emotional experience “in the moment” and reports on aspects of past positive emotional experiences are particularly of interest given the inconsistencies found in past studies (cf. Aghevli et al, 2003; Berenbaum & Oltmanns, 1992; Berenbaum, Snowhite & Oltmanns, 1987; Kring & Neale, 1996; Schlenker, Cohen & Hopmann, 1995).

2. Methods

2.1 Subjects

Thirty-four participants meeting DSM-IV criteria for schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder and 35 healthy participants were recruited into this study. Potential participants were excluded if they reported histories of head trauma with loss of consciousness for more than 15 minutes, substance dependence within the past 6 months, or neurological or systemic illness that might influence cognitive functioning. Diagnoses for all participants were established using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV diagnosis (First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 1997). There were no significant differences between healthy and schizophrenia participants on age, education, parental socioeconomic status, estimated premorbid intelligence (as assessed with the Reading subtest of the Wide Range Achievement Test 3rd Edition, Wilkinson, 1993) race, or sex (Table 1). Schizophrenia participants were tested as clinically stable outpatients. Most were taking second generation antipsychotic medications (n=28), three were taking first generation antipsychotic medications, and three were unmedicated. The work in this article was carried out in accordance with The Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki) for experiments involving humans.

Table 1.

Comparison of Demographic Characteristics for Schizophrenia and Healthy Participants

| Variable | Schizophrenia | Healthy | Significance Test |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 38.71 (9.24) | 42.00 (9.19) | t(67) = 1.49, NS1 |

| Estimated Premorbid Intelligence2 | 97.91 (13.24) | 99.57 (9.98) | t(67) = 0.59, NS |

| Years of Education | 14.79 (4.26) | 13.90 (2.29) | t(50.32) = 1.08, NS |

| Parental Socioeconomic Status | 2.79 (1.29) | 3.18 (1.17) | t(60) = 1.25, NS |

| Sex (M/F) | 18/16 | 19/16 | Chi-square = 0.13, NS |

| Race (Caucasian/African-American/Asian/Latino/Other) | 10/18/2/3/1 | 9/24/0/1/1 | Chi-square = 3.90, NS |

NS = non-significant;

Wide Range Achievement Test, Third Edition

2.2 Measures

2.2.1 Emotional Responses to Visual Stimuli

One hundred and thirty one images tapping a wide range of positive and negative valence, associated with calm to highly aroused responses in normative studies, were selected from the International Affective Picture System (IAPS; Lang, Bradley & Cuthbert, 2001) library for use in this study. Images with content that could be considered offensive (sexually explicit images; mutilation and burn images) were excluded, as responses to such images would not easily generalize to most daily life experiences. Less controversial images that elicited similar emotional responses, based on normative data, were used instead.

Participants were provided written as well as verbal instructions indicating that they should rate each picture in terms of how it made them feel. Subjects provided ratings of their emotional response to the images using the Self-Assessment Manikin (SAM, Bradley & Lang, 1994) which was used in the original IAPS validation study; valence was rated on a 1–9 scale (with 1 extremely negative and 9 extremely positive) and arousal was rated on a 1–9 scale (1 indicating calming, quiet and 9 as exciting, agitating).

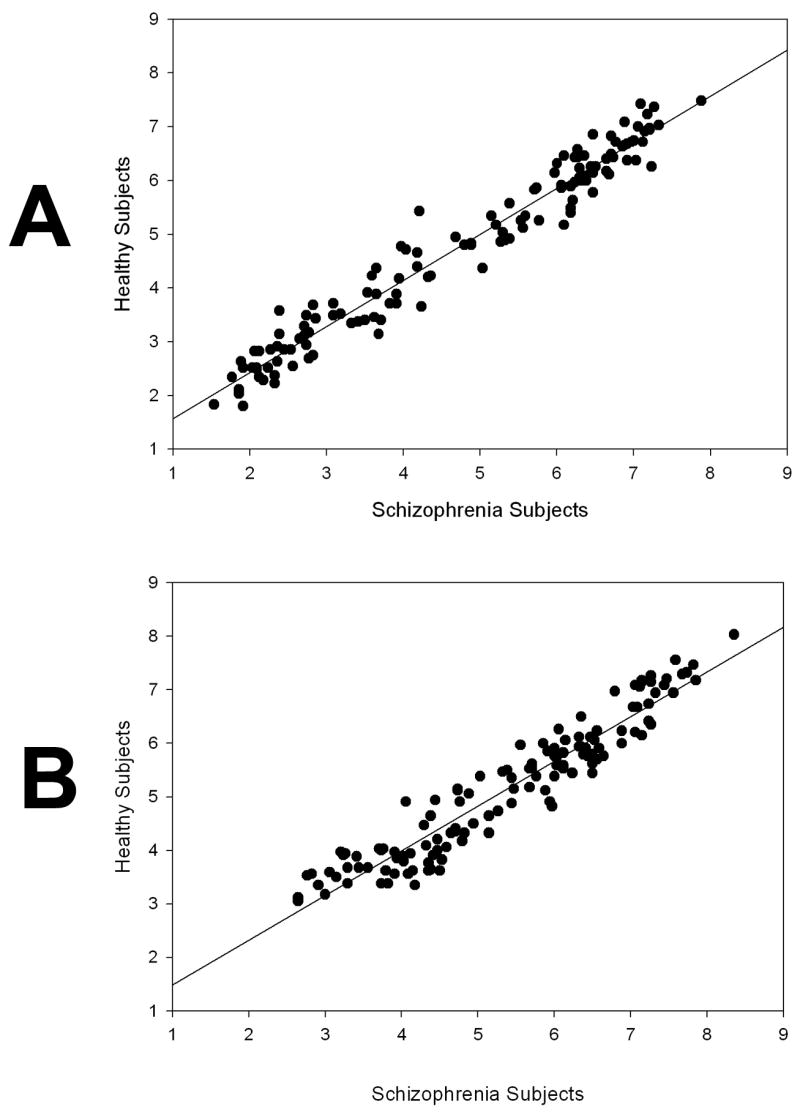

Indices of similarity of image ratings by schizophrenia and healthy subjects were created, first, by correlating the average rating by the two groups for each of the 131 stimuli (as shown in Figure 1). Second, the average ratings by the two subject groups for categories of stimuli at different levels of valence and arousal were obtained (e.g., with images grouped according to high to low valence, and high to low arousal). Stimuli were split into five groups by valence level, and separately into five groups by arousal level, according to their ratings in normative studies (Lang, Bradley & Cuthbert, 2001). This second approach was used to test for group differences in reactivity to specific levels of the valence and arousal dimensions.

Figure 1.

A: Correlation between Schizophrenia and Healthy Participant Valence Ratings of 131 IAPS stimuli

B: Correlation between Schizophrenia and Healthy Participant Arousal Ratings of 131 IAPS stimuli

2.2.2 Clinical Assessments

Severity of schizophrenia-related symptoms was rated using the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) (Kay, Fiszbein, & Opler, 1987). All schizophrenia subjects were also rated on the Heinrichs-Carpenter Quality of Life Scale (H-C QOL; Heinrichs, Hanlon, & Carpenter, 1984), which assesses functioning in four domains: social activity (Interpersonal Scale), productive activity either in the workplace or at home (Instrumental Scale), use of objects and participation in common activities (Common Scale), and intrapsychic functioning as indicated by motivation, anhedonia, curiosity, and empathy.

2.2.3 Perception/Accurate Identification of Facial Emotional Stimuli

All subjects completed computerized emotion perception tasks from the Penn battery, which assess the accuracy of ratings of happy, sad, and neutral emotional expressions (Penn Emotion Acuity Test), (Erwin, Gur, Gur, Skolnick, Mawhinney-Hee, & Smailis, 1992) and the ability to discriminate between faces varying in intensity of happy, sad, and neutral emotional expression (Penn Emotion Differentiation Task) (Kohler et al, 2000).

2.2.4 Self-Reports of Past Emotional Experiences: Anhedonia

Physical and social anhedonia self-report scales (Chapman, Chapman & Raulin, 1976) were completed by all subjects. The physical anhedonia scale assesses the degree to which individuals report that they have found physical sensations to be pleasurable; the social anhedonia scale assesses the degree to which individuals report that they have found social engagement to be pleasurable.

3. Results

3.1 Differences between Diagnostic Groups on Rankings of Response to Emotional Stimuli during initial exposure

Self-reported responses to emotional stimuli were highly similar in schizophrenia and healthy participants across the full spectrum of valence and arousal levels. As shown in Figure 1, rankings of both valence and arousal in response to the 131 images by the two groups were highly correlated (r = 0.98 for valence ratings; r = 0.95 for arousal ratings).

3.2 Differences between Groups in Ratings of Stimuli

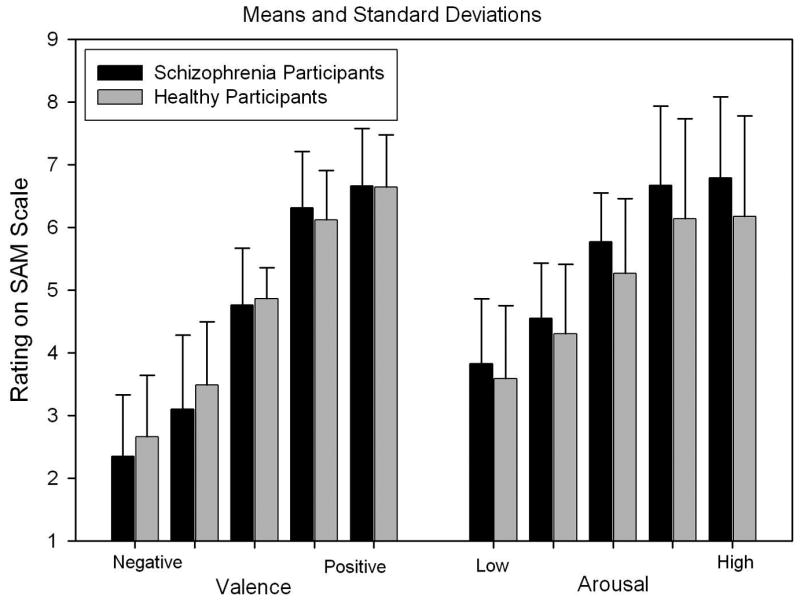

Repeated measures analyses were used to test for group differences (between-group factor) in ratings of the five valence levels and for the five arousal levels (within-group factors). There was a main effect of valence level on subjects’ ratings of their emotional response to the stimuli (F(4,268) = 332.15, p < .001), but there was no significant group difference (F(1,67) = 0.09, p > .20) or group by image valence interaction (F(4,268) = 1.17, p > .20) (Figure 2). In the analyses of arousal ratings, again, there was a large effect of normative image arousal level classification (F(4,244) = 148.09, p < .001) (Figure 2), but, as with valence effects, there was no significant group difference (F(1,61) = 0.43, p > .20), or group by image arousal level interaction (F(4,244) = 0.23, p > .20). Overall the data indicate that both healthy and schizophrenia patients report very similar emotional valence and elicited arousal when viewing IAPS images.

Figure 2.

Average ratings of valence and arousal categories of IAPS images by schizophrenia and healthy participants

3.3 Differences between Diagnostic Groups on Other Measures of Emotional Functioning

Multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was used to assess group differences on the three measures of facial emotion perception (Emotion Acuity Test; Emotion Differentiation Test – Sad condition; Emotion Differentiation Test – Happy condition), and on the two measures of anhedonia. In these analyses, premorbid IQ was included as a covariate, as premorbid IQ measures showed some statistically significant relationships with anhedonia self-reports and performance on the emotion perception measures. There was no significant difference between groups in performance on the Penn facial emotion perception tests (F(3,62) = 2.01, p > .10.). However, there was a significant group difference for self-reported anhedonia (F(2,65) = 3.79, p < .05), with schizophrenia subjects reporting higher levels of both physical and social anhedonia than healthy subjects (Physical Anhedonia schizophrenia Mean (SD) = 16.38 (8.11); Healthy 11.91 (6.44); Social Anhedonia Schizophrenia mean 12.65 (7.04); Healthy = 8.91 (5.06)).

3.4 Relationship between anhedonia ratings and emotional response reports

There were significant correlations between anhedonia levels and valence ratings of the stimuli in both healthy and schizophrenia groups, with these relationships strongest at the more extreme positive and negative valence levels (correlation between physical anhedonia and rating of the most positive stimuli = −0.35, p < .05 for healthy subjects, r = − 0.49, p < .01 for schizophrenia subjects; correlation between physical anhedonia and rating of most negative stimuli = 0.39, p< .03 for healthy subjects, r = 0.41, p < .02 for schizophrenia subjects) (Figure 3). Thus, although anhedonia ratings were significantly higher in the schizophrenia patients, the healthy and schizophrenia groups demonstrated similar relationships between anhedonia ratings and valence ratings of immediate affective response to IAPS images.

3.5 Relationship between Emotional Experience and Measures of Other Aspects of Emotional Functioning

Partial correlations between performance on emotional response, anhedonia self-report, emotion perception, negative symptoms, and quality of life measures, controlling for estimated premorbid intellectual functioning are shown in Table 2. Premorbid intellectual functioning level was included as a covariate because it was found to correlate significantly with several of the measures in both groups. Given the number of correlations computed, only those which were significant at the p < .01 level are discussed. An initial review of Table 2 indicates that there are many more nonsignificant than significant relationships in this table – indicating that there are multiple, independent dysfunctions in emotional processing in schizophrenia, rather than a single “emotional processing” deficit. The majority of correlations significant at the p < .01 are from approaches using a common methodology, and thus these significant correlations may be artifactually elevated by shared methods variance. Partial correlations significant at the p < .01 level using different measures were 1) higher physical anhedonia scores and more negative ratings of positively valenced IAPS stimuli; 2) higher social anhedonia and higher levels of negative symptoms and poorer performance on the Heinrichs-Carpenter Interpersonal Scale; 3) higher levels of negative symptoms and poorer performance on the Heinrichs-Carpenter Interpersonal and Heinrichs-Carpenter Intrapsychic Scales.

Table 2.

Partial Correlations between Performance on Tasks Assessing Emotional Experience, Emotion Perception, Self-Reported Anhedonia, Negative Symptoms, and Quality Of Life Scales in Participants with Schizophrenia controlling for Premorbid Intellectual Functioning

| Emotional Experience Ratings |

Emotion Perception |

Self-Reported Anhedonia |

Clinical Rating |

Quality of Life: Heinrichs-Carpenter scale |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive Valence |

Negative Valence |

High Arousal |

Low Arousal |

Emo Acuity |

ED- Happy |

ED- Sad |

Physical Anhedonia |

Social Anhedonia |

Negative Symptoms |

Inter- personal |

Instrumental | Intra- psychic |

|

| Negative Valence | −0.46** | ||||||||||||

| High Arousal | 0.20 | −0.51** | |||||||||||

| Low Arousal | −0.16 | 0.14 | 0.41* | ||||||||||

| Emotion Acuity | 0.17 | −0.22 | 0.38* | −.16 | |||||||||

| Emo Diff Happy | −0.42* | 0.23 | −0.17 | 0.10 | −0.21 | ||||||||

| Emo Diff Sad | −0.11 | 0.00 | −.04 | −0.21 | −0.11 | 0.59*** | |||||||

| Physical Anhedonia | −0.58** | 0.41* | −0.11 | 0.20 | −0.28* | 0.17 | −0.08 | ||||||

| Social Anhedonia | −0.31 | 0.26 | −0.20 | 0.02 | −0.17* | 0.11 | 0.01 | 0.58*** | |||||

| Negative Symptoms | −0.37* | 0.37* | −0.18 | 0.13 | 0.05 | 0.15 | −0.12 | 0.41* | 0.42** | ||||

| H-C Interpersonal | 0.28 | −0.33 | 0.39* | −0.04 | 0.14 | −0.06 | 0.12 | −0.23 | −0.45** | −0.63*** | |||

| H-C Instrumental | 0.03 | 0.21 | 0.16 | 0.19 | 0.18 | 0.15 | 0.06 | 0.10 | −0.23 | −0.26 | 0.40* | ||

| H-C Intrapsychic | 0.32 | −0.08 | −0.02 | −0.12 | −0.09 | 0.17 | 0.19 | −0.21 | −0.31 | −0.57*** | 0.63*** | 0.41* | |

| H-C Common | 0.17 | −0.02 | 0.39 | 0.27 | −0.15 | 0.11 | −0.08 | −0.07 | −0.26 | −0.35 | 0.43* | 0.57** | 0.55** |

ED-H = Emotion Differentiation Task, Happy condition; ED-S = Emotion Differentiation, Sad Condition; H-C = Heinrichs-Carpenter

p < .05,

p< .01,

p < .001

4. Discussion

The current data provide compelling evidence that schizophrenia patients and healthy individuals do not significantly differ in their immediate response to emotional stimuli, either in terms of intensity of perceived emotional valence or in the arousal that they elicit. These data, consistent with past reports indicating normative emotional experiences “in the moment” for individuals with schizophrenia, provide new evidence that this similarity in emotional experience is seen across a wide range of valence and arousal levels.

4.1 Immediate Emotional Responses and Anhedonia

In both healthy and schizophrenia groups, there was evidence of a significant relationship between self-reported anhedonia and emotional response to affective stimuli. This occurs in the context of no group differences in immediate affective responses and robust group differences in anhedonia. Anhedonia was significantly associated with more moderate emotional responsivity to both positive and negative stimuli in both schizophrenia and healthy groups. Group differences in anhedonia ratings are due to a mean shift of anhedonia scores upward in the schizophrenia sample in comparison to the healthy sample. Thus, in both healthy and schizophrenia patients, there are relationships between trait-like individual differences in hedonic experiences and immediate emotional responses to the emotional IAPS images. At the same time, the significantly higher mean levels of anhedonia between groups is consistent with many past studies (cf. Burbridge and Barch, 2007; Horan, Green, Kring & Nuecheterlein, 2006). Further, the anhedonia scores, along with negative symptom ratings, were the only emotional processing assessments that were significantly related to long-term social functioning, indicating their importance in adaptive functioning.

4.2 Relationships between Different Aspects of Emotional Functioning

The current data indicate that immediate emotional experience in response to affective stimuli is not atypical in schizophrenia across a wide range of valence and arousal levels. Thus abnormal immediate emotional responses do not appear to be responsible for abnormalities found in other aspects of emotional processing seen in the disorder. This observation is consistent with a recent study of emotional modulation of memory which found significant similarity between schizophrenia and healthy subjects in intensity ratings of emotional stimuli during an encoding period, yet memory for the emotional stimuli after a 24 hour delay (involving long term episodic memory processes) was significantly impaired specifically for positive stimuli (Herbener et al, 2007). Similarly, Waltz, Frank, Robinson and Gold (2007) report significant abnormalities in integration of reward information, but not punishment information, in learning that is the basis of decision-making in individuals with schizophrenia.

Multiple research strategies across diverse domains of function suggest that while initial emotional experiences are intact in form and intensity, they fail to organize and guide adaptive cognitive, motivational and social function. It will be important to continue to discern how emotional information is integrated with cognitive information to influence higher-level processes such as goal-setting and decision-making, abilities which are particularly impaired in individuals with schizophrenia.

4.3 Implications for Affective Neuroscience Research

These data provide support for the utilization of IAPS images in psychophysiology and functional imaging studies aiming to elicit emotional responses in individuals with schizophrenia, in that they can be reasonably expected to elicit similar responses to those of healthy individuals. This issue is particularly important as research in affective neuroscience increases, and given the fact that other typically-used emotion-inducing stimuli (e.g., faces, words) may be problematic to use in schizophrenia given documented deficits in accurate recognition of emotional facial expressions (Mueser et al, 1997; Salem, Kring & Kerr, 1996), and of unusual emotional associations to word stimuli (Spitzer, Braun, Hermle & Maier, 1993).

It is not yet clear how to think about emotion deficits in schizophrenia – whether there might be some general emotional processing deficit (similar to the generalized deficit in cognitive processing), whether there are deficits only in specific domains, and how impairments in the integration of emotional information into specific cognitive networks or processes specifically influence multiple cognitive and behavioral outcomes. Findings from the current study suggest that individuals with schizophrenia have some areas of emotional functioning that are intact, such as in the immediate experience of emotional responses, but that some other aspects of emotional functioning, such as self-reported anhedonia, do appear abnormal. While the current sample is relatively small, and it will be important to independently replicate these results, these data do support the importance of developing a complex model of emotional processing that can explain more subtle and differentiated difficulties in different areas of emotional functioning. We need to develop models of emotional processing in schizophrenia that can explain how intact emotional responses fail to organize adaptive behavior, how positive more than negative aspects of experience appear to lose influence on behavior, and how such abnormalities in emotional processing impact day to day function, and ultimately comprise a major cause of functional disability in the illness.

5. Conclusion

The current data demonstrate that individuals with schizophrenia have similar emotional responses to visual emotional stimuli as healthy individuals, and that this similarity extends over a wide range of emotional stimuli. In addition to confirming the normal emotional experience of individuals with schizophrenia at the moment of exposure to stimuli, the present finding shows that clinical evidence of emotional dysfunction is apparently unrelated to any disturbance in immediate emotional experience of events. An important practical implication of our findings is that IAPS visual emotional stimuli seem suitable to elicit emotional reactions in psychophysiological or functional imaging studies of the neural substrate for emotional experience in schizophrenia, since the initial psychological responses to the stimuli appear unimpaired.

Acknowledgments

We thank Lindsay Termini, who has assisted with data collection in this study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aghevli MA, Blanchard JJ, Horan WP. The expression and experience of emotion in schizophrenia: A study of social interactions. Psychiatry Res. 2003;119:261–70. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(03)00133-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berenbaum H, Oltmanns TF. Emotional experience and expression in schizophrenia and depression. J Abnorm Psychol. 1992;101:37–44. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.101.1.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berenbaum H, Snowhite R, Oltmanns TF. Anhedonia and emotional responses to affect evoking stimuli. Psychol Med. 1987;17(3):677–684. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700025915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard JJ, Bellack AS, Mueser KT. Affective and social-behavioral correlates of physical and social anhedonia in schizophrenia. J Abnorm Psychol. 1994;103:719–728. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.103.4.719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard JJ, Mueser KT, Bellack AS. Anhedonia, positive and negative affect, and social functioning in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1998;24:413–24. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley MM, Lang PJ. Measuring emotion: The Self-Assessment Manikin and the Semantic Differential. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 1994;25:49–59. doi: 10.1016/0005-7916(94)90063-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burbridge JA, Barch DM. Anhedonia and the experience of emotion in individuals with schizophrenia. J Abnorm Psychol. 2007;116(1):30–42. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.116.1.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman LJ, Chapman JP, Raulin ML. Scales for physical and social anhedonia. J Abnorm Psychol. 1976;85:374–382. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.85.4.374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis CE, Lebow B, Lake DS, Katsanis J, Iacono WG. Acoustic startle reflex in schizophrenia patients and their first-degree relatives: Evidence of normal emotional modulation. Psychophysiology. 1999;36:469–475. doi: 10.1017/s0048577299980757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erwin RJ, Gur RC, Gur RE, Skolnick B, Mawhinney-Hee M, Smailis J. Facial emotion discrimination: I. Task construction and behavioral findings in normal subjects. Psychiatry Res. 1992;42:231–240. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(92)90115-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders. American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc; Arlington VA: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Heinrichs DW, Hanlong TE, Carpenter WT., Jr The Quality of Life Scale: An instrument for rating the schizophrenic deficit syndrome. Schizophr Bull. 1984;10:388–398. doi: 10.1093/schbul/10.3.388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hempel RJ, Tulen JHM, van Beveren NJM, van Steenis HG, Mulder PGH, Hengeveld MW. Physiological responsivity to emotional pictures in schizophrenia. J Psychiatr Res. 2005;39:509–518. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2004.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbener ES, Harrow M. Are negative symptoms associated with functioning deficits in both schizophrenia and nonschizophrenia patients? A 10-year longitudinal analysis. Schizophr Bull. 2004;30:813–825. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a007134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbener ES, Rosen C, Khine T, Sweeney JA. Failure of positive but not negative emotional valence to enhance memory in schizophrenia. J Abnorm Psychol. 2007;166(1):43–55. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.116.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooker C, Park S. Emotion processing and its relationship to social functioning in schizophrenia patients. Psychiatry Res. 2002;112:41–50. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(02)00177-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horan WP, Green MF, Kring AM, Nuechterlein KH. Does anhedonia in schizophrenia reflect faulty memory for subjectively experienced emotions? J Abnorm Psychol. 2006;115(3):496–508. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.115.3.496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizoph Bull. 1987;13:261–76. doi: 10.1093/schbul/13.2.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohler CG, Bilker W, Hagendoorn M, Gur RE, Gur RC. Emotion recognition deficit in schizophrenia: Association with symptomatology and cognition. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;48:127–136. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(00)00847-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kring AM, Neale JM. Do schizophrenic patients show a disjunctive relationship among expressive, experiential, and psychophysiological components of emotion? J Abnorm Psychol. 1996;105:249–57. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.105.2.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang PJ, Bradley MM, Cuthbert BN. International affective picture system (IAPS): Digitized photographs, instruction manual and affective ratings. Technical Report A-6. University of Florida; Gainesville, FL: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Mueser KT, Penn DL, Blanchard JJ, Bellack AS. Affect recognition in schizophrenia: A synthesis of findings across three studies. Psychiatry. 1997;60:301–8. doi: 10.1080/00332747.1997.11024808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paradiso S, Andreasen NC, Crespo-Facorro B, O’Leary DS, Watkins GL, Boles Ponto LL, Hichwa RC. Emotions in unmedicated patients with schizophrenia during evaluation with positron emission tomography. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:1775–1783. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.10.1775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salem JE, Kring AM, Kerr SL. More evidence for generalized poor performance in facial emotion perception in schizophrenia. J Abnorm Psychol. 1996;105:480–483. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.105.3.480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlenker R, Cohen R, Hopmann G. Affective modulation of the startle reflex in schizophrenic patients. Eur Arch of Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1995;245:309–318. doi: 10.1007/BF02191873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer M, Braun U, Hermle L, Maier S. Associative semantic network dysfunction in thought-disordered schizophrenic patients: direct evidence from indirect semantic priming. Biol Psychiatry. 1993;34:864–77. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(93)90054-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi H, Koeda M, Oda K, Matsuda T, Matsushima E, Matsuura M, Asai K, Okubo Y. An fMRI study of differential neural response to affective pictures in schizophrenia. Neuroimage. 2004;22:1247–1254. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SF, Phan KL, Britton JC, Liberzon I. Neural response to emotional salience in schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005;30:984–995. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waltz JA, Frank MJ, Robinson BM, Gold JM. Selective reinforcement learning deficits in schizophrenia support predictions from computational models of striatal- cortical dysfunction. Biol Psychiatry. 2007 Feb 12; doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.09.042. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson GS. Wide Range Achievement Test. 3. Austin TX: Pro- Ed Inc; 1993. [Google Scholar]