Abstract

Background and objectives: Long-term outcome of patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) correlates with adequacy of predialysis care. This is best provided in a multidisciplinary clinic that integrates the services of a nephrologist with other staff. There is limited data about such clinics in children. The Children's Hospital of Michigan established a Chronic Renal Insufficiency (CRI) clinic in 2002 to provide comprehensive care to children with CKD. These children receive care from a nephrologist, nurse clinician, transplant coordinator, dietician, social worker, and psychologist. The objective of the study was to compare outcome variables between patients from the CRI clinic and a general nephrology clinic.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements: This was a retrospective chart review of 44 patients with CKD stages 2 to 4, who were managed in the general nephrology clinic (1996–2001, n = 20) or the CRI clinic (2002–2007, n = 24) for 1 yr before starting renal replacement therapy (RRT). Laboratory parameters, growth, and dialysis access type at time of RRT were compared between the two cohorts.

Results: At RRT, patients from the CRI clinic had better hemoglobin, lower parathyroid hormone and calcium phosphorus product than patients followed in the general nephrology clinic. More patients from the general nephrology clinic had an unplanned initiation of dialysis compared with patients from the CRI clinic (50% versus 10.5%, P < 0.05).

Conclusions: This indicates that children followed in a multidisciplinary clinic have better outcome variables and are more likely to achieve K/DOQI targets at initiation of dialysis. They are better prepared for dialysis with electively planned catheter insertion or functioning arteriovenous grafts/fistulae.

The incidence of chronic kidney disease (CKD) in children is not well defined and is usually extrapolated from the data available from end-stage renal disease (ESRD) registries. According to the United States Renal Data Service Annual Data Report 2007, the prevalence of CKD in the United States is 13.8% to 15.8% of the adult population (1). Pediatric ESRD patients constitute less than 2% of the total ESRD population (1). In adults, the prevalence of CKD stages 1 to 4 has increased from 10.0% in 1988–1994 to 13.1% in 1999–2004 (2). A part of this increase in prevalence is attributed to a higher prevalence of diabetes, hypertension, and obesity. Because of its high morbidity and mortality, CKD is now recognized as a major public health problem. In a longitudinal study from a large managed care organization, Keith et al. noted that the mortality risk over a mean follow-up period of 3 yr for CKD stages 3 and 4 was 24.3% and 45.7%, respectively, compared with 10.2% in patients without CKD (3). Although mortality rates are significantly lower in pediatric patients with ESRD as compared with adults, the age-specific mortality rate is still 30 to 150 times higher than in children without kidney disease (4). Early evaluation of patients with CKD by nephrologists helps prevent or slow the progression of renal disease, allows timely treatment of renal and extrarenal complications, and facilitates preparation for renal replacement therapy or pre-emptive renal transplant in those approaching ESRD (5,6). In addition to expert medical care by a nephrologist, patients with progressive moderate to severe CKD need dietary, social, and psychological support to ensure optimum growth and development (7–10).

The National Kidney Foundation Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (NKF-K/DOQI) has developed comprehensive guidelines for care of CKD patients (11–13). However, despite these efforts, the morbidity associated with ESRD remains high. One of the reasons could be that most such patients, adults as well as children, are seen in general nephrology clinics that do not offer the comprehensive care required by patients with progressive moderate to severe CKD. The objective of this study was to examine the clinical outcomes in children with moderate to severe CKD who were followed in the multidisciplinary Chronic Renal Insufficiency (CRI) clinic, which we started at the Children's Hospital of Michigan in 2002. These patients were compared with a cohort of our CKD patients followed in a general nephrology clinic before the establishment of the CRI clinic. We evaluated outcome variables in these two cohorts of patients, including laboratory parameters, growth, and dialysis modality and access type at initiation of chronic dialysis.

Materials and Methods

Patient Population

This retrospective study involved 44 consecutive children with CKD, of whom 20 were followed in general nephrology clinic (1996 to 2001) and 24 were followed in the newly established CRI clinic (2002 to 2007) at the Children's Hospital of Michigan. The study inclusion criteria were age less than 18 yr, CKD stages 2 to 4 at study entry, and patient progression to CKD 5 and need for renal replacement therapy (RRT) at the end of a 1-yr follow up. Patients with previous history of RRT in the form of dialysis or renal transplant were excluded from the study because of multiple confounding variables. The GFR was estimated using the Schwartz formula (14) and K/DOQI criteria were used for defining CKD (15). The Wayne State University Institutional Review Board approved the study.

Patient Management

CKD patients who were followed in the general nephrology clinic (1996 to 2001) received somewhat fragmented care, although they were seen predominantly by the same nephrologists every 3 to 6 mo and had access to a dietician and social worker as needed. Patients in the CRI clinic (2002 to 2007) received an organized, multidisciplinary care involving a pediatric nephrologist, nurse clinician, dietician, social worker, and psychologist. The GFR was estimated using the Schwartz formula (14). When the estimated GFR (eGFR) approached close to 30 ml/min/1.73 m2, pre-emptive transplant and the available dialysis modalities were discussed with the patients. At this point, they were also seen by the pretransplant coordinator. If hemodialysis was chosen as the preferred modality for ESRD care, efforts were made to ensure placement of a permanent vascular access before the initiation of dialysis. For those opting for peritoneal dialysis, an elective catheter insertion was scheduled on the basis of blood chemistry, to avoid emergency dialysis secondary to uremic complications. Patients were generally seen in the CRI clinic every 6 mo if the eGFR was 60 to 75 ml/min/1.73 m2, every 3 mo if the eGFR was 30 to 60 ml/min/1.73 m2, and monthly if the eGFR was < 30 ml/min/1.73 m2.

Data Collection

All data were obtained from patient records. This included demographic characteristics, laboratory measurements, medications prescribed, and the number of unplanned hospitalizations. Laboratory data collected for the study included hemoglobin, transferrin saturation, serum calcium (Ca), phosphorus (P), and intact parathyroid hormone (iPTH) at the onset of dialysis or preemptive transplantation. To assess the growth, we calculated the height SDS (standard deviation scores) both at the onset of study period and at the end of 1 yr. The use of erythropoietin, use of growth hormone, presence of gastrostomy tubes, number of unplanned hospitalizations, patient preparedness for dialysis, and modality of dialysis were also assessed. The GFR was estimated at the onset of dialysis and at 1 yr before this using the Schwartz formula.

Statistical Analyses

Categorical data were summarized using counts and percentages. Continuous data were presented with means and SD. The differences in age at start of dialysis, eGFR, serum calcium, calcium-phosphate product, albumin, hemoglobin, and number of hospitalizations between the groups were compared using t test, as the data were normally distributed. The differences in serum phosphorus, PTH, and transferrin saturation between the two groups were compared using the Mann-Whitney U test (two-tailed), as the data were not symmetrically distributed. The onset of dialysis (unscheduled or elective), modality of dialysis, and types of vascular access in the two groups were compared using the chi square test. Hospitalization during 12 mo of clinic exposure was recorded as the number of unplanned hospital admissions per patient per year and the duration of hospital stay. All tests were two-sided, with statistical significance defined as P < 0.05. All analyses were performed using SPSS software for Windows version 15.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

Patient Characteristics

The demographic characteristics of the patients in relation to the clinic in which they were followed (general nephrology versus CRI) are summarized in Table 1. Overall, there were 31(70.5%) male and 13 (29.5%) female patients. Thirty patients (68.3%) were African American, 11 (25%) were Caucasian, 2 (4.5%) were Asian, and 1 (2.2%) was Hispanic. The primary pathology was obstructive uropathy in 15 patients (34.1%), cystic/dysplastic kidneys in 11 patients (25%), focal segmental glomerulosclerosis in seven patients (15.9%) and reflux nephropathy in four patients (9.1%). Two patients had cortical necrosis, and one each had Bartter syndrome, congenital nephrotic syndrome, cystinosis, chronic interstitial nephritis, and IgA nephropathy. The age, gender, and race distribution as well as the underlying causes for CKD were comparable between the two groups of patients.

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants by type of clinic attended

| General Nephrology Clinic (1996-2001) | CRI Clinic (2002-2007) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 10.2 ± 4.9a | 9.7 ± 5.1a |

| Number of patients | 20 | 24 |

| Sex | ||

| male | 14 | 17 |

| female | 6 | 7 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| African American | 15 | 15 |

| Caucasian | 4 | 7 |

| Arabic | 1 | 1 |

| Hispanic | 0 | 1 |

| Underlying cause | ||

| cystic/dysplastic kidneys | 6 | 5 |

| obstructive uropathy | 8 | 7 |

| reflux nephropathy | 2 | 2 |

| FSGS | 3 | 4 |

| other | 1 | 6 |

Age is expressed as mean (SD). Sex, race and underlying cause distribution expressed as number of patients.

P = not significant

Laboratory Parameters

Table 2 presents laboratory parameters at study entry, 1 yr before requirement of RRT. There was no significant difference in the eGFR, serum calcium, phosphorus, iPTH, hemoglobin, and height SDS between the two groups of patients. Table 3 compares the same laboratory parameters after 1 yr, at the end of the study and immediately before initiation of dialysis or a preemptive transplant. At initiation of RRT, patients from the general nephrology clinic had higher serum phosphorus (5.91 ± 1.06 mg/dl versus 5.13 ± 0.71; P = 0.004) and iPTH (385.9 ± 289.6 versus 182.5 ± 138.9 pg/dl; P = 0.008) levels as compared with those from the CRI clinic. The calcium phosphate product was also significantly higher (57.0 ± 9.03 versus 48.43 ± 6.1 mg2/dl2; P = 0.001). The patients seen in the general nephrology clinic had significantly lower hemoglobin concentrations (9.5 ± 1.38 g/dl versus 11.36 ± 1.35; P < 0.001) than patients followed in the CRI clinic. A lower percentage of patients from the general nephrology clinic were receiving erythropoietin therapy (50% versus 62.5%), although this was not statistically significant. Similarly, a lower proportion of patients from the general nephrology clinic had a gastrostomy tube for supplemental feedings (20% versus 41.7%; P = 0.21).

Table 2.

Comparison of laboratory parameters between patients followed in the general nephrology clinic and CRI clinic at study entry

| Parameter | General Nephrology Clinic (1996-2001; n = 20) | CRI Clinic (2002-2007; n = 24) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glomerular filtration rate, ml/min/1.73 m2 | 29.47 ± 22.57 | 27.53 ± 9.67 | 0.13 |

| Calcium, mg/dl | 9.45 ± 0.78 | 9.70 ± 1.38 | 0.44 |

| Phosphorus, mg/dl | 5.35 ± 0.94 | 4.78 ± 0.81 | 0.08 |

| Calcium-phosphorus product, mg2/dL2 | 52.02 ± 12.32 | 45.42 ± 8.89 | 0.08 |

| Parathyroid hormone, pg/ml | 221.50 ± 167.47 | 199.58 ± 171.38 | 0.73 |

| Transferrin saturation, % | 24.80 + 10.56 | 23.81 ± 10.9 | 0.99 |

| Albumin, g/dl | 3.71 ± 0.66 | 3.77 ± 0.71 | 0.79 |

| Hemoglobin, g/dl | 10.66 ± 2.44 | 11.14 ± 1.33 | 0.54 |

All values are expressed as mean ± SD. P <0.05 considered statistically significant.

Table 3.

Comparison of laboratory parameters between patients followed in the general nephrology clinic and CRI clinic at study conclusion (before starting renal replacement therapy, dialysis or pre-emptive transplantation)

| Parameter | General Nephrology Clinic | CRI Clinic | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glomerular filtration rate, ml/min/1.73 m2 | 10.33 ± 2.08 | 13.1 ± 2.72 | 0.001 |

| Calcium, mg/dl | 9.71 ± 0.87 | 9.47 ± 0.59 | 0.27 |

| Phosphorus, mg/dl | 5.91 ± 1.06 | 5.13 ± 0.71 | 0.004 |

| Calcium-phosphorus product, mg2/dl2 | 57.0 ± 9.03 | 48.43 ± 6.15 | 0.001 |

| Parathormone, pg/ml | 385.9 ± 285.9 | 184.7 ± 133.1 | 0.008 |

| Transferrin saturation, % | 24.50 + 12.64 | 27.12 ± 12.24 | 0.45 |

| Albumin, g/dl | 3.69 ± 0.74 | 3.85 ± 0.70 | 0.47 |

| Hemoglobin, g/dl | 9.56 ± 1.34 | 11.36 ± 1.35 | 0.00 |

| Change in GFR over 1 yr, ml/min/1.73m2 | −19.67 ± 20.42 | −13.98 ± 10.09 | 0.23 |

| Unplanned admissions, number per patient per year | 1.3 ± 1.65 | 0.54 ± 0.8 | 0.041 |

All values are expressed as mean ± SD. P <0.05 considered statistically significant.

Growth

A lower proportion of children from the general nephrology clinic were prescribed growth hormone therapy (30% versus 50%; P = 0.18). The mean height SDS at the onset of study period was similar for patients from general nephrology and the CRI clinic (−0.85 compared with −1.33, respectively; P = 0.31). The mean height of patients from the general nephrology clinic after 1 yr follow-up and at the onset of renal replacement therapy was −1.50 as compared with −1.13 for patients from the CRI clinic (P = 0.39). However, over the 1-yr follow up in the CRI clinic, the height SDS changed by 0.19 as compared with a change of −0.27 for patients from the general nephrology clinic (P = 0.08).

RRT

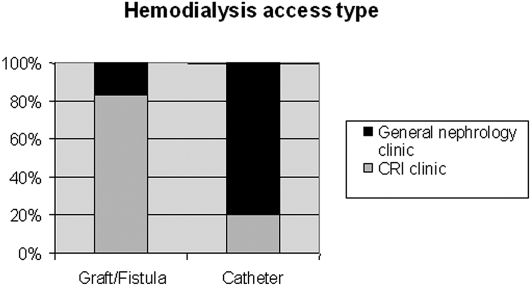

Twenty-four patients were started on peritoneal dialysis and 11 on hemodialysis (13 and six, respectively from CRI clinic). There was no significant difference in the modality of dialysis chosen between the two groups. However, a greater proportion of patients from the general nephrology clinic had an unscheduled first dialysis compared with patients from the CRI clinic (50% versus 10.5%; P = 0.01). A higher percentage of patients in the CRI clinic had a functioning permanent vascular access (arteriovenous fistula or arteriovenous graft) in place at the start of hemodialysis compared with patients from the general nephrology clinic (85.7 versus 20%, P = 0.02; Figure 1). Five patients from the CRI clinic and four from general nephrology underwent a preemptive transplant.

Figure 1.

Vascular access types for hemodialysis for patients from the two clinics. Patients in the chronic renal insufficiency (CRI) clinic had a higher percentage of permanent access compared with those in the general nephrology clinic (85.7 versus 20%, P < 0.05).

Change in GFR

The mean GFR at the start of dialysis in patients from the general nephrology clinic was 10.33 ± 2.08 ml/min/1.73 m2 as compared with 13.1 ± 2.72 ml/min/1.73 m2 for patients from the CRI clinic (P = 0.001). Over a period of 1 yr follow-up, the change in GFR for patients from the general nephrology clinic was −19.67 ± 20.42 ml/min/1.73 m2 as compared with −13.98 ± 10.09 ml/min/1.73 m2 for patients from the CRI clinic. Although this was not statistically significant (P = 0.28), there was a trend toward slower progression to ESRD in patients from the multidisciplinary clinic.

Unplanned Hospitalization

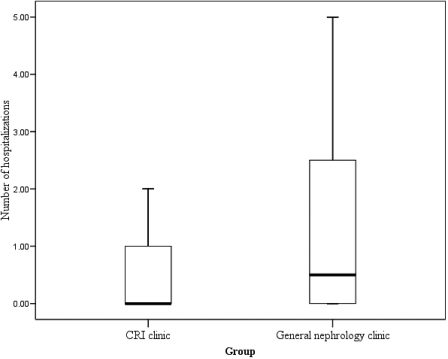

One or more unplanned hospitalizations was noted in eight (33.3%) and 10 (50%) patients followed in the CRI and general nephrology clinics, respectively (P = 0.26). However, the number of hospitalizations for the patients who had been followed in the general nephrology clinic was significantly larger than for those followed in the CRI clinic (0.54 versus 1.3 hospital admissions per patient per year; P = 0.04; Figure 2). Patients from the general nephrology clinic spent a mean of 8.9 d in the hospital as compared with 2.3 d spent by patients from the CRI clinic (P = 0.01).

Figure 2.

Box plot of difference in the number of hospitalizations between the general nephrology and CRI clinic groups. The mean number of admissions was significantly higher in the patients from the general nephrology clinic (P < 0.05). The center line in the box indicates the median; the top and bottom of the box, quartile boundaries; vertical bars, minimum and maximum values within 1.5 times the interquartile range of the quartile boundary.

Discussion

In 1993, a National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference on Morbidity and Mortality of Dialysis recommended that patients be referred to a renal team before the start of dialysis and that attempts be made to initiate timely access placement to avoid acute dialysis onset (16). The consensus panel concluded that continued involvement of a multidisciplinary renal team would improve the quality of life by ensuring social and psychological welfare and appropriate management of malnutrition, as well as addressing other comorbidities.

Optimal management of CKD patients requires a multidisciplinary approach, with the involvement of physicians, dietician, social worker, psychologist, dialysis nurses, and pretransplant coordinator. Recent studies in adults with CKD have shown that patients who are followed in a dedicated multidisciplinary CKD clinic have better outcome variables at the initiation of dialysis (7–9).

In an observational study, Curtis et al. showed an association between exposure to formal multidisciplinary care and survival benefit in patients starting dialysis (10). The patients followed in such a clinic had higher levels of serum hemoglobin, albumin, and calcium at dialysis start than those followed with standard nephrology care. Their study suggested that multidisciplinary care affected these parameters independent of GFR. They also demonstrated a survival advantage after initiation of dialysis.

The National Kidney Foundation's K/DOQI published guidelines in 2002 to improve the detection and management of CKD (15). Subsequently, Hogg et al. established clinical practice guidelines for pediatric CKD (11). The guidelines recommended that the treatment of CKD in children should include evaluation and management of comorbid conditions, as well as prevention and treatment of cardiovascular disease and complications like hypertension, anemia, acidosis, and growth failure. It also emphasized the need to slow the loss of kidney function, and patient preparation for RRT.

The CRI clinic at the Children's Hospital of Michigan was established in 2002 to provide comprehensive, multidisciplinary care to children with GFR < 75 ml/min/1.73 m2. Currently the clinic follows about 70 children with CKD stages 2 to 4. At each clinic visit, a nephrologist, nurse clinician, dietician, social worker, psychologist, and pretransplant coordinator evaluate the patient. These children are generally managed according to the NKF-K/DOQI guidelines.

There is significant morbidity associated with CKD and ESRD. Anemia, hyperphosphatemia, and hypoalbuminemia are widely prevalent in patients with CKD. According to the 2007 Annual Data Report of the United States Renal Data System, in 2005, 39% patients received erythropoietin before initiation of dialysis (1). Although this is an improvement over the previous years, it is not sufficient, as reflected in mean hemoglobin of 9.6 g/dl at initiation. The mean hemoglobin at the initiation of dialysis is less than 10 g/dl, with fewer than 40% receiving erythropoietin (1). As a result of inadequate pre-ESRD care, children are also malnourished at the start of dialysis, and more than half of them have a serum albumin lower than the recommended limit. The 2007 report of the North American Pediatric Renal Trials and Collaborative Studies (NAPRTCS)reported that pediatric patients with a baseline albumin < 4 g/dl, inorganic phosphorous > 5.5 mg/dl, or hematocrit < 33% have a significantly higher risk of reaching ESRD (17). Studies in adults have shown that a hemoglobin of < 8.8 g/dl and hypoalbuminemia at the initiation of dialysis are predictive of morbidity and mortality (18). Mitsnefes et al. showed that anemia was one of the risk factors predicting an interval increase in left ventricular mass in children (19). Hyperphosphatemia also acts as a risk factor for cardiovascular morbidity in patients with CKD by increasing the incidence of coronary artery calcification. The PREPARE study showed that high plasma phosphate is an independent risk factor for a faster decline in renal function and a higher mortality rate during the predialysis phase (20).

In the present study, patients followed in the CRI clinic had better hemoglobin levels with higher percentage of erythropoietin usage at the initiation of dialysis compared with patients followed in the general nephrology clinic. Markers of bone metabolism in CKD, including mean phosphorus, iPTH levels, and the calcium-phosphorus product, were better controlled and were within the K/DOQI target ranges. CRI clinic patients also showed a trend toward better growth parameters. The patients followed in the CRI clinic started dialysis at a higher eGFR as compared with patients from the general nephrology clinic. This may have a bearing on the difference in the biochemical parameters seen in the two groups at the onset of dialysis. However, we believe that closer monitoring of patients in the CRI clinic allowed us to prepare them better for elective rather than emergency dialysis initiation, as was the case with most patients seen in general nephrology clinic. Children undergoing dialysis have approximately two hospitalizations per year and spend nearly 15 d in the hospital annually, with infections being responsible for more than half of that time (1). Among children with CKD, 18.8% children are hospitalized in the first 6 mo of being diagnosed, and 36.4% of these are secondary to infections (17). In our study, the children who received care in the comprehensive CRI clinic had fewer unplanned hospitalizations and spent fewer days in the hospital compared with those followed in the general nephrology clinic.

Children have higher rates of catheter use for dialysis as compared with adults, despite evidence that catheters are a major source of morbidity and mortality. In the long term, the catheters are also associated with more infectious complications and stenoses of central veins. According to the NAPRTCS data on hemodialysis access methods, 77.3% are percutaneous catheters, with arteriovenous fistulae and grafts composing a small minority (12.5% and 7.6%, respectively; 17). In this study, in patients who started hemodialysis, a permanent access was more commonly present in the CRI clinic group. The significantly higher percentage of arteriovenous fistula placement in our center is perhaps the result of an increasing awareness about the Fistula First National Vascular Access Improvement Initiative, which emphasizes the increasing use of arteriovenous fistulae and reduced usage of central venous catheters (21). The NKF/K-DOQI guidelines recommend a 50% arteriovenous fistula rate in all incident HD patients and a 40% prevalent rate in adult hemodialysis patients (22). There are currently no child-specific guidelines in this regard.

This is the first pediatric study comparing the quality outcomes of CKD care in patients followed in a comprehensive multidisciplinary clinic with those in patients followed in a general nephrology clinic. The CRI clinic was found to be superior for all outcome variables.

The study has some limitations. It is a retrospective chart review with a small sample size. Although the study shows the favorable effects of multidisciplinary clinic on morbidity of patients with CKD stages 3 to 4, it does not give us any insight on patients with CKD stages 1 to 2; our study subjects were evaluated retrospectively when they were already on dialysis or had undergone transplantation. There has also been some change in the management practices of pediatric CKD over time. Whereas the recommended target hematocrit has remained similar over the two time periods (23,24), there has been a change in the recommended target PTH levels. Whereas previously it was recommended that PTH be maintained between 2 to 4 times the upper limit of normal, the current guidelines recommend a PTH level of 150 to 300 ng/ml for CKD stage 5. However our data shows that children from the CRI clinic were closer to the recommended PTH targets than those from the general nephrology clinic.

In conclusion, our data show that children who were followed in a comprehensive CRI clinic had better hemoglobin, phosphorus, and PTH at the onset of dialysis. The CRI clinic patients were better prepared for initiation of dialysis with electively planned catheter insertion or functioning arterovenous grafts/fistulae. Unplanned hospitalizations were lower during the 12 mo preceding the onset of dialysis in patients who had been followed in the CRI clinic. More studies need to be done in a prospective manner with a larger cohort of patients to conclusively demonstrate the benefits of multidisciplinary team management in delaying the onset of ESRD, increasing the use of arteriovenous fistulae, and decreasing the acute presentation of ESRD with its associated morbidity and hospitalization.

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgments

This study was presented as an abstract at the Pediatric Academic Societies 2008 Annual Meeting in Honolulu, HI

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

References

- 1.U.S. Renal Data System: Atlas of chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease in the United States, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. In: USRDS 2007 Annual Data Report, Bethesda MD, 2007, 007

- 2.Coresh J, Selvin E, Stevens LA, Manzi J, Kusek JW, Eggers P, Van Lente F, Levey AS: Prevalence of chronic kidney disease in the United States. JAMA 298: 2038–2047, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Keith DS, Nichols GA, Gullion CM, Brown JB, Smith DH: Longitudinal follow-up and outcomes among a population with chronic kidney disease in a large managed care organization. Arch Intern Med 164: 659–663, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chadha V, Warady BA: Epidemiology of pediatric chronic kidney disease. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 12: 343–352, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jungers P, Massy ZA, Nguyen-Khoa T, Choukroun G, Robino C, Fakhouri F, Touam M, Nguyen AT, Grunfeld JP: Longer duration of predialysis nephrological care is associated with improved long-term survival of dialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 16: 2357–2364, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mendelssohn DC: Coping with the CKD epidemic: The promise of multidisciplinary team-based care. Nephrol Dial Transplant 20: 10–12, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ghossein C, Serrano A, Rammohan M, Batlle D: The role of comprehensive renal clinic in chronic kidney disease stabilization and management: The Northwestern experience. Semin Nephrol 22: 526–532, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goldstein M, Yassa T, Dacouris N, McFarlane P: Multidisciplinary predialysis care and morbidity and mortality of patients on dialysis. Am J Kidney Dis 44: 706–714, 2004 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee W, Campoy S, Smits G, Vu Tran Z, Chonchol M: Effectiveness of a chronic kidney disease clinic in achieving K/DOQI guideline targets at initiation of dialysis–A single-centre experience. Nephrol Dial Transplant 22: 833–838, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Curtis BM, Ravani P, Malberti F, Kennett F, Taylor PA, Djurdjev O, Levin A: The short- and long-term impact of multi-disciplinary clinics in addition to standard nephrology care on patient outcomes. Nephrol Dial Transplant 20: 147–154, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hogg RJ, Furth S, Lemley KV, Portman R, Schwartz GJ, Coresh J, Balk E, Lau J, Levin A, Kausz AT, Eknoyan G, Levey AS: National Kidney Foundation's Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease in children and adolescents: Evaluation, classification, and stratification. Pediatrics 111: 1416–1421, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Kidney Foundation: K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for bone metabolism and disease in children with chronic kidney disease. Am J Kidney Dis 46: S1–S121, 2005 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Kidney Foundation: NKF-K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for anemia of chronic kidney disease: Update 2000. Am J Kidney Dis 37: S182–S238, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schwartz GJ, Haycock GB, Edelmann CM, Jr., Spitzer A: A simple estimate of glomerular filtration rate in children derived from body length and plasma creatinine. Pediatrics 58: 259–263, 1976 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Kidney Foundation: K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: Evaluation, classification, and stratification. Am J Kidney Dis 39: S1–S266, 2002 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morbidity and mortality of renal dialysis: An NIH consensus conference statement. Consensus Development Conference Panel. Ann Intern Med 121: 62–70, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.North American Pediatric Renal Trials and Collaborative Studies (NAPRTCS) 2007. Annual Report. Available at www.naprtcs.org. Accessed July 12, 2008.

- 18.Kopple JD: Effect of nutrition on morbidity and mortality in maintenance dialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis 24: 1002–1009, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mitsnefes MM, Daniels SR, Schwartz SM, Meyer RA, Khoury P, Strife CF: Severe left ventricular hypertrophy in pediatric dialysis: Prevalence and predictors. Pediatr Nephrol 14: 898–902, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Voormolen N, Noordzij M, Grootendorst DC, Beetz I, Sijpkens YW, van Manen JG, Boeschoten EW, Huisman RM, Krediet RT, Dekker FW: High plasma phosphate as a risk factor for decline in renal function and mortality in pre-dialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 22: 2909–2916, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tonnessen BH, Money SR: Embracing the Fistula First national vascular access improvement initiative. J Vasc Surg 42: 585–586, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.National Kidney Foundation: NKF-K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for vascular access: Update 2000. Am J Kidney Dis 37: S137–S181, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.National Kidney Foundation: NKF-DOQI clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of anemia of chronic renal failure. Am J Kidney Dis 30 Suppl: 193–240, 1997 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.National Kidney Foundation: National Kidney Foundation K/DOQI Clinical practice recommendations for anemia in chronic kidney disease in children. Am J Kidney Dis 47: S86–S108, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]