Abstract

Purpose: Making choices about everyday activities is a normal event for many adults. However, when an adult moves into an assisted living (AL) community, making choices becomes complicated by perceived needs and community practices. This study examines the relationship between choice and need in the context of practices, using medication administration practices as the case in point. Design and Methods: A 5-year ethnographic study collected information from 6 AL settings in Maryland. Ethnographic interviews (n = 323) and field notes comprise the data described in this article. Results: AL organizations used practice rationales based on state regulations, professional responsibility, safety concerns, and social model values to describe and explain their setting-specific practices. The result was varying levels of congruence between the setting's practices and individual resident's needs and choices. That is, in some cases, the resident's needs were lost to the organization's practices, and in other cases, organizations adapted to resident need and choices. These findings suggest that individuals and organizations adapt to each other, resulting in practices that are not bound by state requirement or other practice rationales. Implications: AL residences vary due to both internal and external forces, not just the public policies that define them. State regulations need to be responsive to both the needs and the choices of individual residents and to the people who work in an AL.

Keywords: Needs, Congruence, Choices, Assisted living facilities, Ethnography, Grounded theory

Contemporary U.S. society values the right of the individual to make choices about daily life. This strongly held cultural norm, and related values such as autonomy, independence, and self-determination, is founded on evidence that choice results in greater satisfaction (Schwartz, 2004). As adults and consumers, we make choices about any number of goods and services and about where and how we live. The assisted living (AL) industry has capitalized on this ethos of choice and described itself as consumer driven (Carder & Hernandez, 2004). However, the residents that AL serves have needs for supportive care, and so in the case of AL, choice is complicated by need. It is further complicated by the fact that AL serves many residents with different combinations of needs and choices. Thus, AL must respond not only to the inherent tensions between an individual resident's needs and choices but also to needs and choices of all other residents. Through their practices and policies, AL settings demonstrate whether an individual's needs trump that person's choices, and the attention given to any one individual in the context of the larger group. Through practices, policies, and their daily interactions with residents, AL organizations reveal whether an individual's needs, choices, or neither take precedence.

An excellent context in which to examine the intersection between individual needs and choices and organizational practices is the case of medication management in AL. Medication management is provided by virtually all AL communities, and once an individual becomes an AL resident, responsibility for medication management typically shifts from an individual concern to an organizational concern. This article will examine choice, need, and organizational response in the context of residents who do and do not self-administer their medications. Variability in organizational response is expected because at least some AL settings attempt to provide traditional long-term care services in a “social model” climate of individual choice and privacy (Kane & Wilson, 2001). An individual resident's needs and choices regarding medication use, then, might not fit with the approach employed at his/her residence.

Theories of Organizations and Individuals

This analysis uses theories of organizational behavior (Scott, 1992) and person–environment fit (Lawton & Nahemow, 1973) to examine the relationship between AL residents’ needs and choices and organizational practices.

Organizational theories explain the behaviors of members and the organization as part of larger institutions or systems (Scott, 1992). Of most relevance to this article are theories of adaptation that describe how organizations adjust to various pressures (Dill, 1993, 1994) and theories of rationalization that explain how organizations define and defend their actions (Dill, 1994; Lopez, 2007; Scott). Studies of service work (Levinson, 2005; Sallaz, 2002) are also especially relevant because they emphasize how social service organizations implement ideals such as consumer independence, choice, and individuality. For example, a study of group homes for adults with intellectual disability found that practical dilemmas resulted from “the inherent conflicts between a climate of regulation and accountability—which demands the bureaucratic rationalization of services—and an ideology of care, which emphasizes the autonomy and individuality of clients” (Levinson, pp. 58–59).

The Lawton and Nahemow (1973) press–competence model considers the individual's competence to adapt to specific forms of environmental press and uses the term “fit” to describe a good match (balance) between individual capacity and environmental press. Adaptation, or the individuals’ ability to adapt to aspects of their environment, is a central feature of this model. From these concepts, we can ask how, for example, residents adapt to organizational policies and practices (Moos & Lemke, 1994). One contribution of this article is that it extends the application of this model that has lagged behind contemporary reality by focusing primarily on individual needs defined by standard measures of physical or cognitive capacity, rather than on individual choice, a more culturally laden concept. Yet, choice is an important construct not only in AL settings but also in other home- and community-based services.

Medication Management in AL

Problems managing medications have been identified as a major reason that older persons move into AL (Lieto & Schmidt, 2005) and as a major policy and practice topic for the industry (Assisted Living Workgroup, 2003; Maybin, 2008). AL residents take an average of 6.2 different medications, and 25% take nine or more (Armstrong, Rhoads, & Meiling, 2001; Crutchfield, Kirkpatrick, Lasak, Tobias, & Williams, 1999). Considering that as many as 80%–90% of AL residents have some degree of cognitive impairment (Leroi et al., 2007; Zimmerman et al., 2007), the need for support in medication management is obvious.

On the organizational level, medication management includes the many tasks involved in accessing, storing, administering, and documenting the use of prescribed medications. The practices implemented within each AL in regard to these activities reflect regulations, professional standards, unique resident needs, and, ultimately, how regulations and standards are interpreted by the staff working at each setting. Organizational practices may not reflect residents’ choices or needs.

The present findings are based on an ethnographic study of six AL residences in Maryland. The settings took unique approaches to managing medications that can be understood based on practice-based rationales that result in varying levels of fit (or congruence) between individual resident's needs and preferences.

Methods

This study is one of a series conducted under the auspices of the Collaborative Studies of Long Term Care (CS-LTC; Zimmerman, Sloane, & Eckert, 2001). The present article is based on a multiyear (2001–2007) ethnographic study financed by the National Institute on Aging (J. Kevin Eckert, principal investigator) designed to explore local social and cultural understandings of decline that result in resident transitions from AL. Sequential ethnographies of 7–10 months were conducted at each of six licensed AL residences in Maryland, as described in more detail in the following. A major aim was to document “explanatory models” used by residents, family, and staff to describe the health and medical needs of AL residents. That is, how did different individuals and groups explain why, for example, a specific resident needed to be transferred to a nursing home? Although medication management was not the primary focus of the study, this topic arose repeatedly throughout the months of fieldwork. Not only was it a subject of discussion during interviews, it was an event that we often observed in practice.

Sample and Settings

Six AL residences participated in this study: two smaller sites, two traditional sites (reminiscent of board-and-care–type AL), and two new model settings (apartment-like units). This number was large enough to allow for diversity among people and places but few enough to permit several months of fieldwork in each setting. One is rural and the rest are suburban; all but the two new-model settings accept Medicaid clients, but both of those offer a private fund for long-term residents whose financial resources were depleted. In each setting, the majority of the residents are elders, and the residents and staff reflect the racial and ethnic diversity of the state. Table 1 provides selected characteristics of these settings (pseudonyms are used for both residents and facilities throughout this article). Five of the settings are stand alone; Middlebury Manor was affiliated with a skilled nursing facility located on the same property. All but one (the Chesapeake) is owner operated. Although three of the larger settings have designated dementia care units, the majority of residents in the two smallest settings had dementia. All but two settings are licensed to provide the highest level of care (e.g., to meet the needs of the most impaired persons).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Participating Assisted Living Residences

| Pseudonym | Licensed capacity | Type | Dementia care unit | Setting |

| Valley Glen Home | 6 | Small | No | Suburban |

| Franciscan House | 8 | Small | No | Suburban |

| Huntington Inn | 35 | Traditional | Yes | Rural |

| Middlebury Manor | 42 | Traditional | No | Suburban |

| The Chesapeake | 100 | New model | Yes | Suburban |

| Laurel Ridge | 112 | New model | No | Suburban |

Note: The owners of Middlebury Manor added a dementia care unit toward the end of our fieldwork there.

In total, we interviewed 323 individuals, including 152 AL residents, 81 family members, 80 staff members (e.g., direct care, administrators, nurses), and 10 other individuals such as case managers and doctors. More detail about the study design and sample has been published elsewhere (Carder, 2008; Eckert, Carder, Morgan, Frankowski, & Roth, in press; Morgan, Eckert, Piggee, & Frankowski, 2006).

Data Collection

Interviews.—

One goal of the ethnographic interviews was to learn how individuals describe their personal experiences using their own words. An interview guide included open-ended questions about reasons the individual moved into AL, life experiences (e.g., school, family, work), daily life in AL, and health care use. Some individuals were interviewed multiple times and others only once, resulting in 379 interviews. In each case, we used a reflexive approach to listen and encourage participants to expand on topics that they wanted to discuss. For instance, some individuals talked at great length about their health, others spoke more about their families. We used participant observation as the impetus for conversations about the daily activities of both staff and residents, including questions about medication use. The majority of interviews were audiotape recorded and all were transcribed.

Participant Observation.—

On average, we conducted 8 months of unstructured observations at each setting; most visits took place during weekdays but also include evening and weekend hours. Each visit ranged from 2 to 10 hr for an average of 5 hr per visit. These observations were organic rather than prescriptive. That is, fieldwork was driven by the people and events specific to each place so that in the small settings we spent most of our time in the main living room and in larger settings we moved between public areas and residents’ individual apartments or rooms. Although we did not specifically shadow staff as they administered medications, we observed both staff as they “passed meds” to residents and some residents as they took their own medications. At each setting, medications were routinely administered during congregate meal times and thus represented a rather public activity that we documented along with other daily events.

Four field ethnographers, all with graduate-level training in qualitative methods, conducted the interviews and wrote detailed field notes to document their observations and activities. They also described their fieldwork to the other members of the study team, including the principal investigator and three coinvestigators, at bimonthly meetings for 5 years.

Analysis

We used a grounded theory approach to coding, as described by Morgan and colleagues (2006). The data and codes were managed with Atlas.ti software (Muhr, 2007). The topic of the present article, medication management, came to light as we reviewed sections of data coded as “medical talk.” Using the Atlas.ti “autocode” technique, text specific to medications (e.g., pills, drugs, prescription, medicine) were coded; this newly created medication code ranked 21st of a total of 53 codes linked to more than 1,100 sections of text (Carder, 2008). Nearly half of the respondents (157 of 323) and 40% of all field notes addressed medications. After coding for medications, we identified organizational- and individual-level themes and sorted them into staff-specific talk and resident-specific talk. Topics within the first category concerned issues such as staff responsibility for administering medications, safety, resident capacity, where and how to store and administer medications, and the role of doctors and families. Resident-specific talk included topics such as symptom management, access to medications, and satisfaction and dissatisfaction with facility policies. This process of organizing data into categories and topics resulted in the major themes described next.

This ethnographic study was designed to produce sound, credible, and valid findings. The specific techniques used to meet these goals include long-term immersion in the field, multiple informant types (e.g., residents, families, staff, policymakers), multiple data collection methods (e.g., interview and observation), bimonthly research team meetings, team-based coding, pattern saturation and negative case assessment (Strauss & Corbin, 1990), literature review, and systematic data analysis with the aid of a data management system.

Results

Cases provide one way of summarizing ethnographic data, as they can illustrate similarities and differences between people within the same organization, and how the same organization does or does not comport itself to individual preferences. Here, we briefly present two cases, each a resident who was interviewed multiple times, to provide context for understanding the intersection of individual needs and choices and organization practices. Following these cases, we provide an analysis based on these and other individuals who were interviewed for this study.

Case 1

Marge Zdenick.—

A former nurse who never married, Marge expected to live out her years in a mobile home that she purchased for her retirement. However, a serious illness and complications from knee surgery meant that a trip to the hospital ended with a move into Huntington Inn AL. She attempted to replicate her prior home in the one-bedroom apartment, such that from a large recliner, she watched television, phoned in orders to a shopping network, and kept up with local and world news by reading the newspaper and watching televised news. Marge was confined to a wheelchair because surgery caused her left knee to “fuse.” Despite this physical impairment, she was largely independent, although staff members came into her room to bring her medications. Marge would have preferred to keep her medications in her room, but the administrator's policy prohibited residents from keeping medications of any kind in their rooms. Marge said,

Everything [medications] has to be administered. And I find that very disconcerting. Because it's like, before you came in here, you had a brain, and you left your brain at the door when you arrived. And now your brain no longer functions. So that takes away independence on my part, you know, it makes me more dependent.

Case 2

Dr. Catherine.—

Dr. Catherine moved into the Chesapeake after she fell in her home and was not found for 2–3 days. Although she was not seriously injured, her children insisted that it was time to move because Dr. Catherine's memory had been failing and her drinking was getting out of hand; it was the apparent reason for her fall. She resisted moving into AL but finally consented when her daughter found a place that allowed her to bring her dog. The Chesapeake felt right to Dr. Catherine. Most of the other residents were, like her, educated, White, and relatively wealthy. In addition, the Chesapeake had a dementia unit, and both she and her daughter expected that one day Dr. Catherine likely would move there; her doctor said that she had an irreversible and progressive dementia. Dr. Catherine was accustomed to being independent and although she appreciated many of the freedoms permitted by life at the Chesapeake, she resented several community rules, including that she was not permitted to leave the grounds alone, that her cigarettes were kept at the front desk, and that she was not permitted to keep over-the-counter (OTC) medications. She told us about a time when she returned from a facility-organized grocery shopping trip, and an employee saw a box of acetaminophen through the transparent plastic shopping bag.

Do you know that she (referring to an AL employee) saw me? I bought an extra thing of Tylenol at the grocery store—and she said, “You have to put that in the nurses’ office.” And I said, “I don’t choose to do that.”

These two cases set the stage for the following discussion of medication management policies and practices and congruence between residents’ preferences and needs.

Organizational Medication Management Practices

At the time of this research, Maryland administrative rules provided AL operators leeway in their medication management practices. The rules permitted unlicensed workers to administer prescribed medications after completing a 16-hr medication management course. AL settings were not required to hire licensed nurses, although they did have to consult with a licensed nurse who reviewed resident records (including medications) at least every 45 days. Residents were allowed to administer their own medications after their physician signed a form indicating that they were capable of doing so.

Despite Maryland's regulatory requirements that apply to all settings, and regardless of licensed capacity or resident payment source, we observed that these settings implemented practices exceeding the requirements. For example, only a small number of residents managed their own medications, even in settings with a stated self-administration policy. Table 2 summarizes the observed medication management policies and practices.

Table 2.

Medication Management Policies and Practices in Six Assisted Living Residences

| Facilities |

||||||

| Policies and practices | VGH | FH | HI | MM | TC | LR |

| Type of staff who administer meds | ||||||

| Med aides | X | X | X | X | X | |

| CNA or LPN only | X | |||||

| Availability of RN | ||||||

| 45-day review or as needed | X | X | X | X | ||

| On-site | X | X | ||||

| Manager's policy for location of med administration | ||||||

| Resident's room | X | X | X | X | ||

| Dining room | X | X | X | |||

| Med room (or similar) | X | X | ||||

| Actual location of med administration | ||||||

| Resident's room | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Dining room | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Med room (or similar) | X | X | X | X | ||

| Permit residents to self-administer | X | Xa | X | |||

| Number of residents who self-administer | 1 | 7 | 3 | |||

| Separate fee charged for med administration | X | X | ||||

Notes: VGH = Valley Glen Home; FH = Franciscan House; HI = Huntington Inn; MM = Middlebury Manor; TC = the Chesapeake; LR = Laurel Ridge; med = medication, RN = registered nurse; CNA = certified nursing assistants; LPN = licensed practical nurses.

The administrator and RN disagreed about whether residents should be permitted to self-administer medications.

Two distinct themes summarize what we learned about how AL organizations respond to individual residents. First, AL organizations use practice-related rationales based on state regulations, professional responsibility, safety concerns, and social model values to describe and defend their setting-specific practices. Second, there is varying congruence between the setting's practices and individual resident's needs and choices. The two themes overlap; for example, a specific practice-related rationale might be the reason for high or low congruence.

Practice-Related Rationales.—

This theme emphasizes that AL settings are organizations that rely on standard bureaucratic procedures such as regulations, professional norms, and safety concerns. The AL setting is a licensed organization held accountable by an external agency and standards of practice; some of the staff are licensed as well (e.g., registered nurses). Although the state rules governing AL permit residents to manage their own medications, the AL operator is ultimately responsible for each resident's health and well-being. Explaining his rationale for not permitting residents such as Marge to manage their own medication at Huntington Inn, Mark Hill (administrator) said, “We could let people manage medications themselves, but if they make a mistake, we get blamed … they [the state agency] want us to be responsible.” Although Mr. Hill was well aware that the state rules permitted capable residents to self-administer their own medications, he let his employees and residents believe that he was required by state rule to manage all medications.

In other cases, the AL managers had difficulty understanding or complying with the state rules for medication management. Valley Glen Home was cited by the county oversight agency for leaving a medicated ointment in one resident's room; the manager explained to us that it was better for this ointment to be located near the particular resident who needed to apply it on a regular basis to manage persistent and painful shingles. As a result of the citation, this manager began storing the ointment in the central medication storage area. In this case, not only were individual preferences not considered but resident need (and possibly well-being) also was ultimately relegated to lesser importance.

Residents interpret organizational practices and try, at times, to subvert them. During one interview, Marge said, “I’m not even supposed to have Vicks or Camphophenic [pointing toward these two products on the shelf next to her chair], but the label came off the Camphophenic bottle so I’m hopin’ the inspectors don’t see that! [laughing] And my Vicks is right there. No, that's a health department rule, or it's a state rule somehow for AL and nursing homes that residents aren’t allowed to have anything.”

Across these settings, residents and their families referred to “state rules” and to organization-specific policies. The daughter of a Middlebury Manor resident described what happened when the staff found a tube of OTC ointment in her mother's room: “That's state policy they said. State policy is residents can have nothing on their own. Everything has to be dispensed from them or the pharmacy.” The tube was confiscated by the staff. When the interviewer asked a new resident of Middlebury Manor if she had known about the policy against residents keeping their own medications, she said, “No, I didn’t know—I knew that they had a nurse here—but I didn’t know that you couldn’t have any medicine.” She went on, “If I want something I’ve got to go to the nurse. In fact everybody does. You can’t just give yourself medication. I guess that's for their protection.” Interviewer, “Their protection?” Resident, “Because you might overdose or something.”

The state regulations emphasize professional norms, another aspect of practice-related rationales. For example, according to Maryland's AL regulations, a physician must sign off on a form that indicates a specific resident's ability to self-administer medications. A medication aide at the Chesapeake explained,

The doctor has to fill out some paper work for us and on that physician's report, it says, “Is your patient able to self administer medications?” If it says “no,” no questions asked … they have to have their medications administered by us.

In addition, AL settings are required to, at a minimum, consult with a licensed nurse to assess each resident's health conditions and medication regimens. Thus, rules that define the organization's responsibility and professional standards serve as a legitimate rationale for setting-specific practices.

Another rationale for specific medication management practices was grounded in safety guidelines, especially concerns related to cognitive impairment. The managers of the two small homes in this study, where nearly every resident had some degree of cognitive impairment, managed all aspects of their resident's medications. Dr. Catherine's case indicates some of the complexity presented by cognitive impairment. Her dementia diagnosis meant that she was placed on the medication management program. Still, Dr. Catherine wanted to keep an OTC pain medication in her apartment and when she described the staff's attempt to remove such medication from her control, she said, “that kind of thing makes me feel belittled.” When asked if she “hid” the medicine in her apartment, she said, “I haven’t hidden it. It's in my medicine cabinet. But if they would try to take it away I would say, ‘You are taking something that belongs to me.’”

Dementia provides a rationale for organizational practices that do not permit any resident, regardless of cognitive status, to self-administer medications. For example, an employee trained as a geriatric nurse assistant at Middlebury Manor said that although “bedside orders” were possible for medications such as creams and sprays, “We try not to encourage that here … because you might have a patient that has dementia.” When asked by the interviewer whether she expected the residence to change its policy after a new locked dementia care unit was completed, she said, “No, I wouldn’t encourage it.”

The aforementioned rationales fit with standard operating procedures of bureaucratic organizations (Scott, 1992). The final aspect of practice-related rationales we observed better fits organizational studies of service work (Levinson, 2005; Sallaz, 2002) because that literature describes how service-based agencies attempt to implement ideals such as consumer independence, choice, and individuality. For example, although the administrator of Middlebury Manor personally preferred a more medical approach, he also described the link between residents’ self-administration of medications and independence, “… certainly if someone is capable of doing anything, we want them to do it. Because the more independent they are, that means actually the more active they are going to be because they are doing these things for themselves.” Referring to the one resident (of 42 total residents) who managed his own medications, this administrator said, “For him to take his own medications he, every day has to read what they are, double check, make sure he's doing these things. So that in itself is an activity and it's keeping him independent and active, so that's a good thing.”

The medication management practices at the Chesapeake differed markedly from the other five settings. Here, capable residents were encouraged to manage their own medications, and their apartments had doors that locked as well as lockable cabinets designed for safely storing medications. An additional fee was charged for medication assistance—a service that residents could choose or not based on some combination of need and preference.

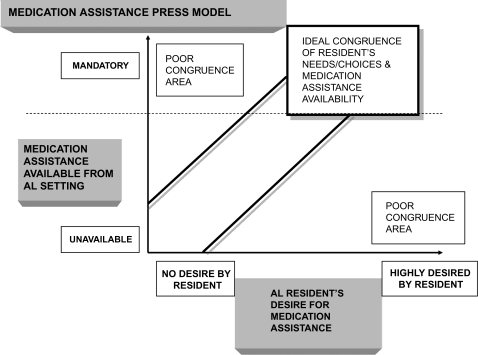

Congruence Between Individual Needs and Choices and Organizational Practices.—

The aforementioned sections indicate that AL settings have different rationales for the specific medication management practices that they employ. These practices affect how residents experience medication management and, more specifically, the congruence between residents’ needs and choices and the practices in force at each setting. Figure 1 provides a graphic representation, based on the Lawton and Nahemow (1973) model, of this process.

Figure 1.

Congruence between resident preference and assisted living (AL) setting policies and practices.

High congruence.

For many, if not most residents at these six settings, receiving medication assistance was a relief. Dr. Smith, initially bitter that his son arranged for him and his wife to move into the Chesapeake, conceded that he needed help managing his medications. He said,

I was taking these medicines in a haphazard way at home. I appreciate the routine of the medication schedule and the routine of three square meals a day. Sometimes at home I would forget to take my pills for a few days. My wife would ask, “Aren’t you supposed to be taking your pills?” and then I’d remember. Having the medications gal is a Godsend in many ways.

At Middlebury Manor, when asked by the interviewer why she was taking a specific medication, Stella said,

I don’t know, she said it's for pain or whatever. I guess in case you want to feel better. [laughs] I don’t know what they give you them for … I asked her [the medication aide] what they were and she tells me, but I forget.

Stella's inability to recall what medications she takes provides an example of why medication management is a necessary and important service.

Reflecting a consumer perspective, Mrs. Roettger, a resident of the Chesapeake, said, “I have permission to self medicate, which I am extremely glad about because it's a whole lot cheaper. That way I can take it when I feel I need it. Like to wake up at 2:00 a.m. and need a couple Tylenol and not be able to get it right away so you can go back to sleep, would complicate life.”

Low congruence.

Marge Zdenick's case exemplifies the other dimension of congruence between resident needs and choices and the setting's practices. A retired nurse, she could have managed her own medications but was not permitted to do so; she once observed that, “Here everybody is put in the same tub, it doesn’t make any difference what is best for me.”

At Laurel Ridge, medicines are administered from a small “library” that offers only limited seating for residents who arrive to receive their medications. Some complained that they had to stand in line for a long stretch of time until the medication aide was yet ready for them. During a resident council meeting. we heard one woman argue that, “We have a right … not to stand in line or wander back and forth between our rooms and the lounge.” A similar situation arose at Middlebury Manor when the manager began requiring residents to come to a centralized location for their medications rather than having staff deliver them directly to resident's rooms, a time-consuming affair. This new policy resulted in a large number of complaints from residents and their families and because it was difficult to enforce when residents refused to comply, the manager soon discontinued this practice. This is an example of an organizational practice surrendering to individual preferences.

Low congruence sometimes resulted in other types of conflict between residents and staff. We frequently heard about instances of residents or their families acquiring OTC medications to treat pain, cold symptoms, skin irritations, or digestive problems. Some residents resorted to hiding such medications, but the staff learned to be on the lookout, as in the case of Dr. Catherine's Tylenol mentioned earlier. At Middlebury Manor, Mrs. Fitzsimmons had multiple encounters with the nurse, Carol, over medications. It began when Carol saw a bottle of antidiarrheal medication on Mrs. Fitzsimmons’ window ledge and then asked to see the contents of her locked cabinet drawer. She confiscated a tube of ointment that Mrs. Fitzsimmons’ doctor had recommended to prevent skin irritation due to incontinence. Mrs. Fitzsimmons said, “It wasn’t the last time Carol looked in there” [referring to her cabinet] and then she described a debate they had over the use of Vicks. Carol told Mrs. Fitzsimmons, “no, no, no, no, no, you can’t keep that in here” and proceeded to take the jar to which Mrs. Fitzsimmons said, “My God, Carol, I’ve used Vicks all my life and I’m almost 90 years old. You mean to tell me that's going to hurt me now!” Carol responded, “If the Health Department comes in here and sees them in your drawer, we’d get in trouble. You’re not allowed to have those things.” A week later Carol reversed her position, telling Mrs. Fitzsimmons that she could keep the ointment, Vicks, and antidiarrheal in her room, but that she should only take one dose of the latter. Mrs. Fitzsimmons told us, however, that “I thought, sister, if I need the second dose, I’m taking it.” Again, we have an example of an organizational policy surrendering to resident preferences, but as in the first example, it occurred only after a visible controversy.

Similar events occurred at other settings including Huntington Inn, where Francis argued with Mr. Hill when he told her that she could not keep sinus medication in her room. She described an exchange she once had with him,

I used to have mine in my room right here until Mr. Hill said “You can’t have it in your room.” I said why? I paid for it. But he said, “If the state would come in—I would lose my license.”

One reason that some residents chose to hide OTCs used to treat common maladies was that this strategy was preferable to asking staff for medications needed only occasionally. Francis expressed a sentiment that we heard from other residents both at Huntington Inn and at other settings when she said, “I hate to even go to the office and say ‘Could I have a Tylenol?’ Because they [staff] … are so busy.”

Discussion

Traditional descriptions of consumer choice conceive of individuals as rational actors who make choices that best match their tastes (Schwartz, 2004). However, life is more complicated than this basic model suggests, in part, because choice is restricted by need and by the context of the organization within which the negotiation occurs. Organizational theories and environmental gerontology provide concepts for understanding the outcomes of these interactions.

This study indicates that “need” is variously defined by professionals (e.g., a physician who assesses the individual's ability to self-manage medications), by families, by AL staff, and by the individual resident. Residents’ needs and choices in the context of a regulatory environment concerned with safety resulted in a variety of practice-based rationales for the medication management practices we observed. Not only residents but also the AL staff made adaptations in this dynamic environment. AL operators adapt by revising practices to respond to individual residents and to external factors such as regulatory changes, corporate expectations, and market forces. When residents hide medications in their room, staff might resort to monitoring the personal space of these residents by searching for contraband items or, alternately, a standard practice might be changed to meet the demands of one or more residents.

Adaptation is a central concept in environmental gerontology, asking us to assess how people adapt, in this case, to AL medication management policies and practices. The case is such that in actuality, residents, staff, and ALs as organizations adapt to various environmental pressures: residents to the AL setting's policies and practices, and the AL setting to their licensing body and the demands of unique residents. Poor fit for residents was at times the outcome of one-size-fits-all policies such as prohibiting all residents from managing their own medications, spatial arrangements such as inadequate storage or centralized medication administration locations, and beliefs among some staff that older people cannot or should not manage medications. A resident's own advocacy was able to improve the fit and increase congruence, but the fact that such advocacy was necessary indicates that at least in the settings included in this study, AL might be less a consumer-directed model of care than originally envisioned. The individual can become lost in the organizational setting due to safety concerns expressed as organizational rationales.

AL is, by and large, a fee for service business. Reflective of the diversity in the larger arena of AL, these six settings took different approaches to setting fees for services, including medication management. As indicated in Table 2, two settings charged a separate fee for this service. Laurel Ridge set fees based on a package of services, including medication management. Some residents, such as Mrs. Roettger at the Chesapeake aforementioned, expressed gratitude that they could save money by managing their own medications, whereas there were other residents, and their relatives, who appreciated that trained staff took care of this task (Carder, Schumacher, Zimmerman, & Sloane, 2007). The extent to which the practice of charging a fee for medication management affects either resident satisfaction or quality of care cannot be answered by these data.

For residents, poor congruence that was not improved by advocacy resulted in seemingly deceptive practices among some who hid or disguised medications they wanted to be able to easily access. We observed this to be true for OTC medications used to treat common maladies such as colds, digestive upset, and pain. Residents who resort to hiding medications in their rooms reflect a negative adaptation to facility policies and practices that do not fit their needs or choice. Further, such poor adaptation establishes antipathy between residents and those who are entrusted to provide their care, and also could result in adverse outcomes such as missed diagnoses or duplication of medications. This point highlights the fact that there is liability inherent in the matter of an organization not recognizing and respecting individual preferences and autonomy. To date, we have considered such a matter to be a “social” right, but this article underscores that it may have medical consequences as well.

Of course, some residents adapt to practices, and in so doing, they might not only relinquish their own rights but also may abdicate other basic responsibilities for self-care. As a case in point, when describing their medications, some residents stated that they did not know what they took or for what conditions they were taking them. Although there are many likely explanations for residents lacking this information, one potential reason raised by this study is that they have adapted to centralized control of medications by relinquishing self-responsibility, including personal health knowledge. In this case, the organizational press was insufficient to maintain or maximize function, which is a consideration one step removed, but no less important, than individual preferences.

Before concluding, a few limitations of this study should be noted. First, it was not designed to study medication management practices. However, the data indicate that some residents prefer to maintain control over some, or all, of their medical treatments and that AL staff attempt to establish medication management policies that respond to both the needs and the choices of residents. Although not expected to be the case, it could be that the specific settings we studied are unique in ways that limit the application of these findings. Further, it might be tempting to consider whether poor fit results in a specific outcome such as a medication-related error or a resident's decision to move. How or whether practices such as additional fees for medication management versus all-inclusive fees affect resident choices to, for example, manage their own medications, remains uncertain. This study cannot address such questions because it was not designed to look at specific resident outcomes.

This article has identified several organizational practices and resident outcomes that deserve further study. In providing a firsthand account of the intersection of individual needs and choices and organizational practices related to medication management in AL, it illuminates tensions that have implications for other areas of care in this and other group settings that serve older adults. As human service–based organizations, ALs must follow regulatory mandates, but they also espouse ideological goals such as consumer choice and autonomy. In AL settings, tensions between these two organizational mandates have implications for how work gets done and how residents experience the services. Some ALs adopt a standardized approach to care, whereas others provide more individualized services. Although not addressed in this article, we know that some settings required each resident to receive assistance from staff to take a shower, whereas others did not. This raises questions about whether an organization uses similar or different rationales to describe the delivery of other personal care services. This study suggests that the concept of “fit” between people and place should be expanded to include not only fit between residents and setting but also between the people who work at the setting and the residents.

This article and findings from future research have policy implications. It is notable that several of these settings exceeded the state rules for medication management by not allowing residents to self-administer medications. Are policies lagging behind practice or are these organizations uncertain about how to implement the policies? In either case, policies need to be responsive to both the needs and choices of individual residents and the people who work in AL. Future research on medication management or other personal care services provided in AL must examine the local context of these settings. The range of practices observed in even a small number of settings in one state indicates that studies of either policy or practice must look beyond state regulations as a basis for research questions and sampling decisions because that approach might miss the variety in policy and practice that result from adaptation between individuals and organizations over time.

Funding

This research was funded by an award from the National Institute on Aging (NIA AG19345) to J. Kevin Eckert.

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff, residents, and family members who participate in the Collaborative Studies of Long-Term Care for their time and commitment to learning more about and improving the quality of life in residential care/AL communities. We also acknowledge the contributions of the other members of the research team who conducted the study described here, especially Leanne Clark, Ann Christine Frankowski, Lynn Keimig, Leslie A. Morgan, Erin Roth, Robert L. Rubinstein, and Tommy Piggee, Sr.

References

- Armstrong EP, Rhoads M, Meiling F. Medication usage patterns in assisted living facilities. Consulting Pharmacist. 2001;6:65–69. [Google Scholar]

- Assisted Living Workgroup. Assuring quality in assisted living: Guidelines for federal and state policy, state regulation, and operations. A report to the U.S. senate special committee on aging. Washington, DC: 2003. American Association of Homes and Services for the Aging. [Google Scholar]

- Carder PC. Managing medication management in assisted living: A situational analysis. Journal of Ethnographic and Qualitative Research. 2008;3:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Carder PC, Hernandez M. Consumer discourse in assisted living. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2004;59:S58–S67. doi: 10.1093/geronb/59.2.s58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carder PC, Schumacher JG, Zimmerman S, Sloane PD. Medication management: Integrating the social and medical models. Assisted Living Consult. 2007;3(2):18–22. [Google Scholar]

- Crutchfield DB, Kirkpatrick MA, Lasak ME, Tobias EE, Williams D. Assisted living facilities: A resource manual for pharmacists. Alexandria, VA: American Society of Consultant Pharmacists; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Dill A. Defining needs, defining systems: A critical analysis. The Gerontologist. 1993;33:453. doi: 10.1093/geront/33.4.453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dill A. Institutional environments and organizational responses to AIDS. Journal of Health & Social Behavior. 1994;35:349–369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckert JK, Carder PC, Morgan LA, Frankowski AC, Roth EG. Inside assisted living: The search for home. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Kane RA, Wilson KB. Assisted living at the crossroads: Principles for its future. Portland, OR: Jessie F. Richardson Foundation; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Lawton MP, Nahemow L. Ecology and the aging process. In: Eisdorfer C, Lawton MP, editors. Psychology of adult development and aging. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1973. pp. 619–674. [Google Scholar]

- Leroi I, Samus QM, Rosenblatt A, Onyike CU, Brandt J, Baker AS, et al. A comparison of small and large assisted living facilities for the diagnosis and care of dementia: The Maryland assisted living study. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2007;22:224–232. doi: 10.1002/gps.1665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levinson J. The group home workplace and the work of know-how. Human Studies. 2005;28:57–85. [Google Scholar]

- Lieto JM, Schmidt KS. Reduced ability to self-administer medication is associated with assisted living placement in a continuing care retirement community. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2005;6:246–249. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2005.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez S. Efficiency and the fix revisited: Informal relations and mock routinization in a nonprofit nursing home. Qualitative Sociology. 2007;30:225–247. [Google Scholar]

- Maybin J. Report from an expert symposium on medication management in assisted living. Assisted Living Consult. 2008;4(4):20–28. [Google Scholar]

- Moos R, Lemke S. Group residences for older people: Physical features, policies, and social climate. New York: Oxford University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan LA, Eckert JK, Piggee T, Frankowski AC. Two lives in transition: Agency and context for assisted living residents. Journal of Aging Studies. 2006;20:123–132. [Google Scholar]

- Muhr T. Atlas.ti version 5.2.11. Berlin, Germany: Scientific Software Development; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Sallaz JJ. The house rules. Work & Occupations. 2002;29:394. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz B. The paradox of choice: Why more is less. New York: Ecco; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Scott WR. Organizations: Rational, natural, and open systems. 3rd ed. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss A, Corbin J. The basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman S, Sloane PD, Eckert JK, editors. Assisted living: needs, practices and policies in residential care for the elderly. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2001. An overview of the collaborative studies of long-term care. In S. Zimmerman, P. D. Sloane, & J. K. Eckert (Eds.) [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman S, Sloane PD, Williams CS, Dobbs D, Ellajosyula R, Braaten A, et al. Residential care/assisted living staff may detect undiagnosed dementia using the minimum data set cognition scale. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2007;55:1349–1355. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01289.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]