Abstract

Transcription factors (TFs) regulate the expression of genes at the transcriptional level. Modification of TF activity dynamically alters the transcriptome, which leads to metabolic and phenotypic changes. Thus, functional analysis of TFs using ‘omics-based’ methodologies is one of the most important areas of the post-genome era. In this mini-review, we present an overview of Arabidopsis TFs and introduce strategies for the functional analysis of plant TFs, which include both traditional and recently developed technologies. These strategies can be assigned to five categories: bioinformatic analysis; analysis of molecular function; expression analysis; phenotype analysis; and network analysis for the description of entire transcriptional regulatory networks.

Keywords: Arabidopsis, Bioinformatics, Functional analysis, Methodology, Transcription factor

Introduction

It is evident that transcriptional regulation plays a pivotal role in the control of gene expression in plants. Intensive studies of plant mutants have revealed that informative phenotypes are often caused by mutations in genes for transcription factors (TFs), and a number of TFs have been identified that act as key regulators of various plant functions. TFs, which regulate the first step of gene expression, are usually defined as proteins containing a DNA-binding domain (DBD) that recognize a specific DNA sequence. In addition, proteins without a DBD, which interact with a DNA-binding protein to form a transcriptional complex, are often categorized as TFs. Although some metabolic enzymes have been suggested to regulate gene expression directly in yeast (Hall et al. 2004), we do not focus on such multifunctional proteins in this review. In 2000, the entire genome sequence of Arabidopsis thaliana was determined and the genome was predicted to contain 25,498 protein-coding genes (Arabidopsis Genome Initiative 2000). Based on sequence conservation with known DBDs, Riechmann et al. (2000) reported that around 1,500 of these genes encode TFs, and more recent analyses have recognized >2,000 TF genes in the Arabidopsis genome (Davuluri et al. 2003, Guo et al. 2005, Iida et al. 2005, Riano-Pachon et al. 2007).

In contrast to Arabidopsis, the number of TF genes found in Drosophila melanogaster and Caenorhabditis elegans, which have similar sized genomes to that of Arabidopsis, is around 600, which is significantly less than that in Arabidopsis (Riechmann et al. 2000). The ratio of TF genes to the total number of genes in Arabidopsis is 5–10% depending on databases, which is higher than that of D. melanogaster (4.7%) and of C. elegans (3.6%) (Riechmann et al. 2000), although it is comparable with that of human (6.0%) (Venter et al. 2001). In addition to the larger number of TF genes in Arabidopsis, there is a greater variety of TFs, with a greater diversity of DNA binding specificities, compared with D. melanogaster or C. elegans (see later for more details). These characteristic features of Arabidopsis TFs suggest that transcriptional regulation plays more important roles in plants than in animals. Because transcriptional regulation is the first step of gene expression and could affect various ‘omes’, namely the proteome, metabolome and phenome, the functional analysis of TFs is important and necessary for omics studies and for the elucidation of whole functional networks in plants. Although much effort has been made to identify the function of TFs, most of their functions remain to be clarified. In this mini-review, we present an overview of Arabidopsis TFs and describe strategies for the functional analysis of plant TFs, which include both traditional and recently developed technologies.

Overview of Arabidopsis transcription factors

According to The Arabidopsis Information Resources (TAIR, http://www.arabidopsis.org), there are 27,235 protein-coding genes in the Arabidopsis genome (ftp://ftp.arabi-dopsis.org/home/tair/Genes/TAIR8_genome_release/README). Four independent reports have recently shown that approximately 2,000 genes encode TFs (Table 1). These four representative databases of Arabidopsis TFs are: RARTF (http://rarge.gsc.riken.jp/rartf/) (Iida et al. 2005), AGRIS (http://arabidopsis.med.ohio-state.edu/AtTFDB/) (Davuluri et al. 2003), DATF (http://datf.cbi.pku.edu.cn/) (Guo et al. 2005) and PlnTFDB (http://plntfdb.bio.uni-potsdam.de/v2.0/index.php?sp_id=ATH) (Riano-Pachon et al. 2007). Each database classified TFs into families based on their own classification criteria, and the number of loci in each family is different among the four databases. A total of 51, 51, 64 and 67 families (72 families in total) and 1,965, 1,837, 1,914 and 1,949 loci (2,620 loci in total), respectively, were identified. A total of 1,318 loci are recognized by all four databases (Table 1 and Supplementary Table S1). These differences are mainly due to the different definition of a TF in each database. For example, the AGRIS database does not include AUX/IAA proteins as TFs as they do not directly bind to DNA but repress auxin-mediated gene transcription by interacting with ARF transcription factors (Ouellet et al. 2001), whereas the other three databases classifies them as being TFs (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison of plant TF databases

| RARTF | AGRIS | DATF | PlnTFDB | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family | Loci | Family | Loci | Family | Loci | Family | Loci | |

| 1. | ABI3/VP1 | 51 | ABI3VP1 | 11 | ABI3-VP1 | 60 | ABI3VP1 | 56 |

| REM | 21 | |||||||

| 2. | Alfin-like | 47 | Alfin-like | 7 | Alfin | 7 | Alfin-like | 7 |

| 3. | AP2/EREBP | 93 | AP2-EREBP | 136 | AP2-EREBP | 146 | AP2-EREBP | 146 |

| ERF | 19 | |||||||

| Pti4 | 5 | |||||||

| Pti5 | 5 | |||||||

| Pti6 | 18 | |||||||

| 4. | ARF | 71 | ARF | 22 | ARF | 23 | ARF | 23 |

| RAV | 11 | |||||||

| 5. | ARID | 6 | ARID | 7 | ARID | 10 | ARID | 10 |

| 6. | AT-hook | 31 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 7. | – | – | – | – | AS2 | 42 | – | – |

| 8. | Aux/IAA | 21 | – | – | AUX-IAA | 28 | AUX/IAA | 27 |

| 9. | – | – | BBR/BPC | 7 | BBR-BPC | 7 | BBR/BPC | 7 |

| 10. | – | – | BZR | 6 | BES1 | 8 | BES1 | 8 |

| 11. | bHLH | 157 | bHLH | 162 | bHLH | 127 | bHLH | 134 |

| 12. | – | – | – | – | – | – | bHSH | 1 |

| 13. | bZIP | 56 | bZIP | 73 | bZIP | 72 | bZIP | 71 |

| TGA3 | 27 | |||||||

| 14. | C2C2(Zn)-CO-like | 51 | C2C2-CO-like | 30 | C2C2-CO-like | 37 | C2C2-CO-like | 17 |

| Pseudo ARR-B | 5 | |||||||

| 15. | C2C2(Zn)-Dof | 33 | C2C2-Dof | 36 | C2C2-Dof | 36 | C2C2-Dof | 36 |

| 16. | C2C2(Zn)-GATA | 37 | C2C2-Gata | 30 | C2C2-GATA | 26 | C2C2-GATA | 29 |

| 17. | C2C2(Zn)-YABBY | 5 | C2C2-YABBY | 6 | C2C2-YABBY | 5 | C2C2-YABBY | 6 |

| 18. | C2H2(Zn) | 177 | C2H2 | 211 | C2H2 | 134 | C2H2 | 96 |

| 19. | C3H-type 1(Zn) | 37 | C3H | 165 | C3H | 59 | C3H | 67 |

| 20. | – | – | CAMTA | 6 | CAMTA | 6 | CAMTA | 6 |

| 21. | CBF5 | 2 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 22. | CCAAT | 37 | CCAAT-DR1 | 2 | CCAAT-Dr1 | 2 | CCAAT | 43 |

| CCAAT-HAP2 | 10 | CCAAT-HAP2 | 10 | |||||

| CCAAT-HAP3 | 10 | CCAAT-HAP3 | 11 | |||||

| CCAAT-HAP5 | 13 | CCAAT-HAP5 | 13 | |||||

| 23. | CPP(ZN) | 8 | CPP | 8 | CPP | 8 | CPP | 8 |

| 24. | – | – | – | – | – | – | CSD | 4 |

| 25. | – | – | – | – | – | – | DBP | 4 |

| 26. | – | – | – | – | – | – | DDT | 4 |

| 27. | E2F/DP | 8 | E2F-DP | 8 | E2F-DP | 8 | E2F-DP | 7 |

| 28. | EIL | 6 | EIL | 6 | EIL | 6 | EIL | 6 |

| 29. | – | – | – | – | FHA | 16 | FHA | 17 |

| 30. | GARP | 51 | G2-like | 40 | GARP-G2-like | 42 | G2-like | 39 |

| ARR-B | 15 | GARP-ARR-B | 10 | ARR-B | 13 | |||

| 31. | – | – | GeBP | 16 | GeBP | 21 | GeBP | 20 |

| 32. | – | – | – | – | GIF | 3 | – | – |

| 33. | GRAS | 32 | GRAS | 31 | GRAS | 33 | GRAS | 33 |

| 34. | – | – | GRF | 9 | GRF | 9 | GRF | 9 |

| 35. | HB | 97 | Homeobox | 91 | HB | 87 | HB | 91 |

| PAIRED(w/o HB) | 2 | |||||||

| 36. | HMG-box | 11 | – | – | HMG | 11 | HMG | 11 |

| 37. | – | – | HRT | 3 | HRT-like | 2 | HRT | 2 |

| 38. | HSF | 27 | HSF | 21 | HSF | 23 | HSF | 23 |

| 39. | C3H-type 2(Zn) | 10 | JUMONJI | 5 | JUMONJI | 17 | Jumonji | 17 |

| JUMONJI | 13 | |||||||

| 40. | LFY | 3 | LFY | 1 | LFY | 1 | LFY | 1 |

| 41. | LIM-domain | 6 | – | – | LIM | 13 | LIM | 6 |

| 42. | – | – | – | – | LUG | 2 | LUG | 2 |

| 43. | MADS | 106 | MADS | 109 | MADS | 102 | MADS | 102 |

| 44. | – | – | – | – | MBF1 | 3 | MBF1 | 3 |

| 45. | MYB superfamily | 189 | MYB | 130 | MYB | 149 | MYB | 145 |

| MYB-related | 67 | MYB-related | 49 | MYB-related | 64 | |||

| 46. | NAC | 106 | NAC | 94 | NAC | 105 | NAC | 101 |

| 47. | Nin-like | 14 | NLP | 9 | Nin-like | 14 | RWP-RK | 14 |

| AtRKD | 5 | |||||||

| 48. | – | – | – | – | NZZ | 1 | NOZZLE | 1 |

| 49. | PcG; E(z) class | 32 | PcG | 34 | SET | 33 | ||

| PcG; Esc class | 3 | |||||||

| 50. | PHD-fi nger | 9 | PHD | 11 | PHD | 55 | PHD | 43 |

| 51. | – | – | – | – | PLATZ | 10 | PLATZ | 11 |

| 52. | – | – | – | – | – | – | RB | 1 |

| 53. | – | – | – | – | S1Fa-like | 3 | S1Fa-like | 3 |

| 54. | – | – | – | – | SAP | 1 | SAP | 1 |

| 55. | SBP | 17 | SBP | 16 | SBP | 16 | SBP | 16 |

| 56. | Sir2 | 2 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 57. | – | – | – | – | – | – | Sigma70-like | 6 |

| 58. | – | – | – | – | SRS | 10 | SRS | 10 |

| 59. | – | – | – | – | – | – | SNF2 | 38 |

| 60. | SW13 | 6 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 61. | Swi4/Swi6 | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 62. | – | – | – | – | TAZ | 9 | TAZ | 8 |

| 63. | TCP | 24 | TCP | 26 | TCP | 23 | TCP | 24 |

| 64. | Trihelix | 31 | Trihelix | 29 | Trihelix | 26 | Trihelix | 23 |

| 65. | TUB | 11 | TUB | 10 | TLP | 11 | TUB | 10 |

| 66. | – | – | – | – | ULT | 2 | ULT | 2 |

| 67. | – | – | VOZ | 2 | VOZ | 2 | VOZ | 2 |

| 68. | VIP3 | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 69. | – | – | Whirly | 3 | Whirly | 2 | PBF-2-like | 3 |

| 70. | WRKY(Zn) | 72 | WRKY | 72 | WRKY | 72 | WRKY | 72 |

| 71. | – | – | ZF-HD | 15 | ZF-HD | 16 | zf-HD | 17 |

| 72. | – | – | ZIM | 2 | ZIM | 18 | ZIM | 15 |

| Other | 81 | Other | 1 | Other | 69 | |||

| Total | 1965 | Total | 1837 | 1837 Total | 1914 | Total | 1949 | |

The number of loci in each database is shown. ‘–’ indicates that no corresponding TF family is defined in the database.

Arabidopsis TFs are characterized by a large number of genes and by the variety of gene families when compared with those of D. melanogaster or C. elegans. For example, zinc-finger TFs represent more than half of all TFs in D. melanogaster or C. elegans, whereas those in Arabidopsis represent around 20% (Riechmann et al. 2000). Around half of Arabidopsis TFs are plant specific and possess DBDs found only in plants (Riechmann et al. 2000 and Table 1). AP2-ERF, NAC, Dof, YABBY, WRKY, GARP, TCP, SBP, ABI3-VP1 (B3), EIL and LFY are plant-specific TFs. The three-dimensional structures of several plant-specific DBDs, i.e. NAC, WRKY, SBP, EIL, B3 and AP2-ERF, have been determined (Allen et al. 1998, Ernst et al. 2004, Yamasaki et al. 2004a, Yamasaki et al. 2004b, Yamasaki et al. 2005a, Yamasaki et al. 2005b). Most Arabidopsis TFs form large families, which share similar DBD structures. For example, AP2-ERF and NAC domain families contain >100 loci each (Table 1). MYB, MADS box, bHLH (basic helix–loop helix), bZIP and HB, which are not plant-specific families, also form large families. These families, such as the MADS box family, which includes a number of ABC floral homeotic genes (Riechmann et al. 1996), play important roles in the control of plant growth and development.

TFs act as transcriptional activators or repressors. In common with other eukaryotes, TFs containing domains rich in the acidic amino acids glutamine or proline, such as TOC1, DREBs, ARFs and GBF1, are transcriptional activators (Schindler et al. 1992, Ulmasov et al. 1999, Strayer et al. 2000, Sakuma et al. 2002). In addition, the AHA motif, which has a characteristic pattern of aromatic and large hydrophobic amino acid residues embedded in an acidic context, was shown to act as an activation domain (AD) in plant heat shock factors (Döring et al. 2000).

On the other hand, transcriptional repressors in plants were not elucidated until the ERF-associated amphiphilic repression (EAR) motif was identified in tobacco ETHYLENE RESPONSIVE ELEMENT BINDING FACTOR 3 (EREBP3) (Ohta et al. 2000). Transcriptional repressors are roughly categorized into passive or active repressors. Passive repressors have neither an AD nor a repression domain (RD). Some repress transcription by binding to the promoter of the target gene, thereby competing with an activator that interacts with the same cis-element. Maize Dof2 is known to be a passive repressor (Yanagisawa and Sheen 1998). Arabidopsis CAPRICE (CPC), TRIPTYCHON (TRY), ENHANCER OF TRY AND CPC1 (ETC1), ETC2 and ETC3, which are all small MYB proteins with a single R3-MYB domain, are negative regulators involved in the development of epidermal cells (reviewed in Simon et al. 2007) and are likely to act as passive repressors. They compete with other R2-R3 MYB proteins such as GLABRA1 (GL1) and WEREWOLF (WER) that positively regulate epidermal cell development for interaction with bHLH proteins (Esch et al. 2004, Simon et al. 2007, Tominaga et al. 2007). The active repressors possess distinct RDs that confer repressive activity to the TF. The EAR motif is a plant-specific repression domain. The minimum unit of the EAR-motif RD is only six amino acids, which comprise an amphiphilic feature composed of leucine and acidic amino acids (Hiratsu et al. 2004). Because fusion of the EAR motif RD can convert a transcriptional activator into a strong repressor (Hiratsu et al. 2003), TFs that contain this motif are assumed to be transcriptional repressors, although experimental validation is required. Database analysis revealed that the EAR motif RD is found in 404 loci among 2,620 putative TFs (Supplementary Table S1). Interestingly, RDs are over-represented in the C2H2 zinc finger (68/136), AUX-IAA (28/29) and HB (32/93) families (Supplementary Table S1). Most RDs are conserved in various plants, including dicots and monocots, but are not obviously over-represented in TFs of other organisms, such as yeast (N. Mitsuda et al. unpublished results). These suggest that the EAR motif RD and its mechanism of action is plant specific. Recently, novel RDs that could not be categorized according to the EAR motif (Hiratsu et al. 2004) were identified in AtMYBL2 and B3 DBD TFs (Matsui et al. 2008, Ikeda and Ohme-Takagi 2009). This suggests that unidentified transcriptional repressors with novel RDs may be encoded in plant genomes. Activators and repressors act antagonistically to control the fine-tuning of gene expression. The molecular mechanism of transcriptional repression via the EAR motif RD remains to be clarified. Chromatin remodeling may be involved because the EAR motif interacts with TOPLESS (TPL), and mutations in HISTONE ACETYLTRANSFERASE GNAT SUPERFAMILY 1 suppress the tpl-1 phenotype (Long et al. 2006, Szemenyei et al. 2008). In animals, bifunctional TFs have been reported, which can act as transcriptional activators or repressors, depending on the environment or target genes (Adkins et al. 2006). In plants, WRKY53 has been shown to act as either a transcriptional activator or repressor depending on the sequence surrounding the W-box (Miao et al. 2004).

The activities of most TFs are controlled at the transcriptional level by other TFs, while several TFs are regulated post-transcriptionally, such as EIN3 (Yanagisawa et al. 2003). Small RNAs that target TF genes are also important regulators of gene expression (see Table 3 and Bioinformatic analysis). TFs that are regulated at the post-transcriptional level may be regulators that act at early stages of transcriptional cascades.

Table 3.

List of TF genes targeted by miRNA

| miRNA family | miRNA locus | Target family | Target locus | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| miR156/miR157 | AT2G25095 (miR156A) | SBP | AT5G43270 | (SPL2) |

| AT4G30972 (miR156B) | AT2G33810 | (SPL3) | ||

| AT4G31877 (miR156C) | AT1G53160 | (SPL4) | ||

| AT5G10945 (miR156D) | AT3G15270 | (SPL5) | ||

| AT5G11977 (miR156E) | AT1G69170 | (SPL6) | ||

| AT5G26147 (miR156F) | AT2G42200 | (SPL9) | ||

| AT2G19425 (miR156G) | AT1G27370 | (SPL10) | ||

| AT5G55835 (miR156H) | AT1G27360 | (SPL11) | ||

| AT1G66783 (miR157A) | AT5G50570 | (SPL13) | ||

| AT1G66795 (miR157B) | AT3G57920 | (SPL15) | ||

| AT3G18217 (miR157C) | ||||

| AT1G48742 (miR157D) | ||||

| miR159/miR319 | AT1G73687 (miR159A) | MYB | AT5G06100 | (ATMYB33) |

| AT1G18075 (miR159B) | AT3G11440 | (ATMYB65) | ||

| AT2G46255 (miR159C) | AT4G26930 | (ATMYB97) | ||

| AT4G23713 (miR319A) | AT2G32460 | (ATMYB101) | ||

| AT5G41663 (miR319B) | AT2G26950 | (ATMYB104) | ||

| AT2G40805 (miR319C) | AT5G55020 | (ATMYB120) | ||

| AT3G60460 | (DUO1) | |||

| TCP | AT4G18390 | (TCP2) | ||

| AT1G53230 | (TCP3) | |||

| AT3G15030 | (TCP4) | |||

| AT2G31070 | (TCP10) | |||

| AT1G30210 | (TCP24) | |||

| miR160 | AT2G39175 (miR160A) | ARF | AT2G28350 | (ARF10) |

| AT4G17788 (miR160B) | AT4G30080 | (ARF16) | ||

| AT5G46845 (miR160C) | AT1G77850 | (ARF17) | ||

| miR164 | AT2G47585 (miR164A) | NAC | AT3G15170 | (CUC1) |

| AT5G01747 (miR164B) | AT5G53950 | (CUC2) | ||

| AT5G27807 (miR164C) | AT5G07680 | (ATNAC4) | ||

| AT5G61430 | (ATNAC5) | |||

| AT1G56010 | (NAC1) | |||

| AT5G39610 | (ORE1) | |||

| AT3G12977 | ||||

| miR165/miR166 | AT1G01183 (miR165A) | HB | AT2G34710 | (PHB) |

| AT4G00885 (miR165B) | AT1G30490 | (PHV) | ||

| AT2G46685 (miR166A) | AT1G52150 | (CAN) | ||

| AT3G61897 (miR166B) | AT5G60690 | (REV) | ||

| AT5G08712 (miR166C) | AT4G32880 | (ATHB8) | ||

| AT5G08717 (miR166D) | ||||

| AT5G41905 (miR166E) | ||||

| AT5G43603 (miR166F) | ||||

| AT5G63715 (miR166G) | ||||

| AT3G22886 (miR167A) | ARF | AT1G30330 | (ARF6) | |

| AT3G63375 (miR167B) | AT1G37020 | (ARF8) | ||

| AT3G04765 (miR167C) | ||||

| AT1G31173 (miR167D) | ||||

| miR169 | AT3G13405 (miR169A) | CCAAT | AT5G06510 | (NF-YA10) |

| AT5G24825 (miR169B) | AT1G72830 | (HAP2C) | ||

| AT5G39635 (miR169C) | AT1G17590 | (NF-YA8) | ||

| AT1G53683 (miR169D) | AT1G54160 | (NF-YA5) | ||

| AT1G53687 (miR169E) | AT5G12840 | (HAP2A) | ||

| AT3G14385 (miR169F) | AT3G20910 | (NF-YA9) | ||

| AT4G21595 (miR169G) | AT3G05690 | (HAP2B) | ||

| AT1G19371 (miR169H) | ||||

| AT3G26812 (miR169I) | ||||

| AT3G26813 (miR169J) | ||||

| AT3G26815 (miR169K) | ||||

| AT3G26816 (miR169L) | ||||

| AT3G26818 (miR169M) | ||||

| AT3G26819 (miR169N) | ||||

| miR170/miR171 | AT5G66045 (miR170) | GRAS | AT2G45160 | |

| AT3G51375 (miR171A) | AT3G60630 | |||

| AT1G11735 (miR171B) | AT4G00150 | (SCL6) | ||

| AT1G62035 (miR171C) | ||||

| miR172 | AT2G28056 (miR172A) | AP2-EREBP | AT2G28550 | (TOE1) |

| AT5G04275 (miR172B) | AT5G60120 | (TOE2) | ||

| AT3G11435 (miR172C) | AT5G67180 | (TOE3) | ||

| AT3G55512 (miR172D) | AT4G36920 | (AP2) | ||

| AT5G59505 (miR172E) | AT2G39250 | (SNZ) | ||

| AT3G54990 | (SMZ) | |||

| miR393 | AT2G39885 (miR393A) | bHLH | AT3G23690 | (bHLH077) |

| AT3G55734 (miR393B) | ||||

| miR396 | AT2G10606 (miR396A) | GRF | AT2G22840 | (ATGRF1) |

| AT5G35407 (miR396B) | AT4G37740 | (ATGRF2) | ||

| AT2G36400 | (ATGRF3) | |||

| AT3G52910 | (ATGRF4) | |||

| AT5G53660 | (ATGRF7) | |||

| AT4G24150 | (ATGRF8) | |||

| AT2G45480 | (ATGRF9) | |||

| miR778 | AT2G41616 (miR778A) | SET | AT2G35160 | (SGD9) |

| AT2G22740 | (SDG23) | |||

| miR824 | AT4G24415 (miR824A) | MADS | AT3G57230 | (AGL16) |

| miR828 | AT4G27765 (miR828A) | MYB | AT1G66370 | (ATMYB113) |

| miR858 | AT1G71002 (miR858A) | MYB | AT2G47460 | (ATMYB12) |

| AT3G08500 | (ATMYB83) |

Bioinformatic analysis

The functional analysis of TFs using bioinformatic techniques has become an important and effective strategy. Databases concerned with the functional analysis of TFs are listed in Table 2. Initially, amino acid sequence analysis should be performed to find evolutionarily conserved domains (CDs), including DBDs. Some TFs possess two DBDs. For example, RAV1 (At1g13260) group members have both AP2-ERF and B3 DBDs (Kagaya et al. 1999). Normally, a TF has a DBD and a transcriptional AD or RD. TFs having only a DBD are likely to be passive repressors, as reported for CPC and TRY, which interfere with the activity of the transcriptional activator (complex) (Simon et al. 2007). CD searches against known motifs can be performed using many web-based programs. One of the most useful services is InterProScane provided by the European Bioinformatics Institute (EBI) (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/InterProScan/) (Quevillon et al. 2005). This search is comprehensively performed against various CD databases and provides sophisticated graphical output. Finding known or unknown CDs among a set of proteins can be performed by MEME (http://meme.sdsc.edu/meme/intro.html) (Bailey et al. 2006). The SALAD database, which was developed specifically for plant proteins, also provides MEME-based CD searching with various other useful tools (http://salad.dna.affrc.go.jp/salad/en/).

Table 2.

List of useful databases for the functional analysis of TFs

| Category/database name | URL | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| Plant (Arabidopsis) transcription factors | ||

| RARTF | http://rarge.gsc.riken.jp/rartf/ | |

| AGRIS | http://arabidopsis.med.ohio-state.edu/AtTFDB/ | |

| DATF | http://datf.cbi.pku.edu.cn/ | A part of a plant transcription factor database |

| PlnTFDB | http://plntfdb.bio.uni-potsdam.de/v2.0/index.php?sp_id=ATH | Data of other plants are also stored |

| Conserved domain search | ||

| InterProScan | http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/InterProScan/ | For known motifs |

| MEME | http://meme.sdsc.edu/meme/intro.html | For discovering unknown motifs |

| SALAD database | http://salad.dna.affrc.go.jp/salad/en/ | For known and unknown motifs |

| Homology search | ||

| TAIR BLAST | http://www.arabidopsis.org/Blast/index.jsp | For Arabidopsis only |

| NCBI BLAST | http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi | For multispecies search |

| Prediction of subcellular localization | ||

| SUBAII | http://www.plantenergy.uwa.edu.au/suba2/ | Experimental data are also stored |

| Protein–protein interaction | ||

| Arabidopsis predicted interactome | http://www.arabidopsis.org/portals/proteome/proteinInteract.jsp | |

| EBI IntAct | http://www.ebi.ac.uk/intact/site/index.jsf | For all organisms |

| AtPID | http://atpid.biosino.org/index.php | |

| Small RNAs | ||

| ASRP | http://asrp.cgrb.oregonstate.edu/db/ | Includes data of miRNA, siRNA and ta-siRNA |

| Repository of microarray data | ||

| NCBI GEO | http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/ | |

| EBI ArrayExpress | http://www.ebi.ac.uk/microarray-as/ae/ | |

| NASCArrays | http://affymetrix.arabidopsis.info/narrays/experimentbrowse.pl | |

| Browsing microarray data and co-expression analysis | ||

| ATTED-II | http://atted.jp/ | |

| Genevestigator | https://www.genevestigator.com/gv/index.jsp | |

| BAR eFP browser | http://bbc.botany.utoronto.ca/efp/cgi-bin/efpWeb.cgi | |

| Finding novel cis-elements | ||

| TAIR motif analysis | http://www.arabidopsis.org/tools/bulk/motiffinder/index.jsp | |

| Database of known cis-elements | ||

| PLACE | http://www.dna.affrc.go.jp/PLACE/ | No longer updated after 2007 |

| AGRIS ATCISDB | http://arabidopsis.med.ohio-state.edu/AtcisDB/ | |

| GO categorization | ||

| TAIR GO annotation search | http://www.arabidopsis.org/tools/bulk/go/index.jsp | |

Homology searches, for example performed by BLAST, are also important for the bioinformatic study of TFs. Proteins which share high homology not only in their DBDs but also in other regions are likely to be functionally redundant, at least in tissues where they are co-expressed. However, it is frequently observed that proteins with high homology only in the DBD also function redundantly. For example, although CUP-SHAPED COTYLEDON1 (CUC1) and CUC3 are known to function redundantly, there is no significant sequence similarity outside the DBD (Vroemen et al. 2003, Hibara et al. 2006). BLAST searches against Arabidopsis can be performed through TAIR (http://www.arabidopsis.org/Blast/index.jsp). BLAST searches against multiple species, such as Arabidopsis and rice, can also be informative to assess functional redundancy. If three Arabidopsis proteins correspond to one rice protein, these three proteins might function redundantly. BLAST searches against a favorite combination of species can be performed through the NCBI website (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi).

Analysis of the subcellular localization of putative TFs is important because TFs cannot function outside the nucleus. Some NAC domain TFs possess a transmembrane motif at the C-terminus and are liberated by proteolytic cleavage to move into the nucleus (Kim et al. 2006, Kim et al. 2008). Subcellular localization of proteins can be predicted by computer programs such as SubLoc (Hua and Sun 2001), TargetP (Emanuelsson et al. 2000) and WoLF PSORT (Horton et al. 2007). Predictions of subcellular localization using 10 different computer programs and also from experimental evidence can be retrieved from the SUBAII database (http://www.plantenergy.uwa.edu.au/suba2/) (Heazlewood et al. 2007). This database also provides hydropathy plots of all Arabidopsis proteins.

The investigation of proteins that interact with TFs is also of great importance. Many TFs are known to form functional complexes. For example, some NAC TFs and MADS TFs form homo- or hetero-dimeric or tetrameric complexes (Honma and Goto 2001, Ernst et al. 2004, Heazlewood et al. 2007). MYB TFs and bHLH TFs often form complexes (Zimmermann et al. 2004a). A number of TFs are known to interact with kinases, resulting in TF phosphorylation (He et al. 2002, Furihata et al. 2006, Robertson et al. 2008). Predicted or experimentally validated protein–protein interactions (PPIs) among Arabidopsis proteins can be retrieved from the TAIR, EBI and AtPID databases. The ‘Arabidopsis predicted interactome’, stored at TAIR, provides a set of >20,000 PPIs based on ortholog matching (http://www.arabidopsis.org/portals/proteome/proteinInteract.jsp) (Geisler-Lee et al. 2007). EBI provides the IntAct database, which stores continu-ously updated PPI information of all organisms based on literature curation (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/intact/site/index.jsf) (Kerrien et al. 2007). The Arabidopsis thaliana Protein Interactome Database (AtPID) provides a search facility with graphical output against a predicted and literature-curated Arabidopsis PPI data set (http://atpid.biosino.org/index.php) (Cui et al. 2008).

microRNA (miRNA) is also an important regulator of TF activity. According to the Arabidopsis small RNA Project (ASRP) (http://asrp.cgrb.oregonstate.edu/db/) (Gustafson et al. 2005, Backman et al. 2008), 200 genes are predicted to be targets of known miRNAs. Interestingly, 69 of these genes (35%) encode putative TFs (Table 3 and Supplementary Table S1), despite TFs representing only 5–10% of all genes. For example, miRNAs that target TCP, NAC and SBP TFs are known to play very important roles in the control of plant growth and development (Palatnik et al. 2003, Wu and Poethig 2006, Ori et al. 2007, Schommer et al. 2008, Kim et al. 2009, Larue et al. 2009). ASRP also provides non-coding small RNA information (reviewed in Ramachandran and Chen 2008), such as for small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) and trans-acting siRNAs (ta-siRNAs), in addition to that for miRNAs. Six TF genes are listed as targets of ta-siRNAs in ASRP.

The spatial and temporal expression profile of a gene and the expression in response to varying conditions is fundamental to its biological function. Development of microarray technologies and public data repositories, such as NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) (Barrett et al. 2007), EBI ArrayExpress (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/microarray-as/ae/) (Parkinson et al. 2009) and NASCArrays (http://affymetrix.arabidopsis.info/narrays/experimentbrowse.pl) (Craigon et al. 2004), enables us to access many kinds of microarray data easily. The expression profile of a gene of interest can also be easily accessed on many web sites, such as ATTED-II (http://atted.jp/) (Obayashi et al. 2009), Genevestigator (https://www.genevestigator.com/gv/index.jsp) (Zimmermann et al. 2004b, Grennan 2006) and BAR eFP browser (http://bbc.botany.utoronto.ca/efp/cgi-bin/efpWeb.cgi) (Winter et al. 2007). These web sites also provide information regarding co-expression analysis. They provide lists of genes whose expression profiles are positively or negatively correlated with the query gene (Zimmermann et al. 2004b, Toufighi et al. 2005, Grennan 2006, Obayashi et al. 2009). Co-expression analysis is particularly important for the functional analysis of TFs because co-expressed genes might encode proteins that are functionally related and/or are putative interacting proteins. They might also be downstream and/or upstream genes in the context of a transcriptional cascade. Hirai et al. (2007) identified MYB TFs as the key regulators of aliphatic glucosinolate biosynthesis by co-expression analysis. From promoter regions of co-expressed genes, short sequences that are statistically over-represented and may represent TF-binding sites can be identified using TAIR Motif Analysis (http://www.arabidopsis.org/tools/bulk/motiffinder/index.jsp). It is valuable to compare these sequences with known cis-elements stored in cis-element databases, such as PLACE (http://www.dna.affrc.go.jp/PLACE/) (Higo et al. 1999) and AGRIS ATCISDB (http://arabidopsis.med.ohio-state.edu/AtcisDB/). Furthermore, functional characteristics of these genes can be analyzed using the TAIR Gene Ontology (GO) annotation search (http://www.arabidopsis.org/tools/bulk/go/index.jsp). A set of favorite genes can be categorized based on a limited GO term (Ashburner et al. 2000) and shown as a graphical pie chart. In addition, we can compare these data with the results of functional categorization of all Arabidopsis proteins. These analyses help us to speculate on the biological processes in which the set of genes and the query TF are involved.

Molecular analysis

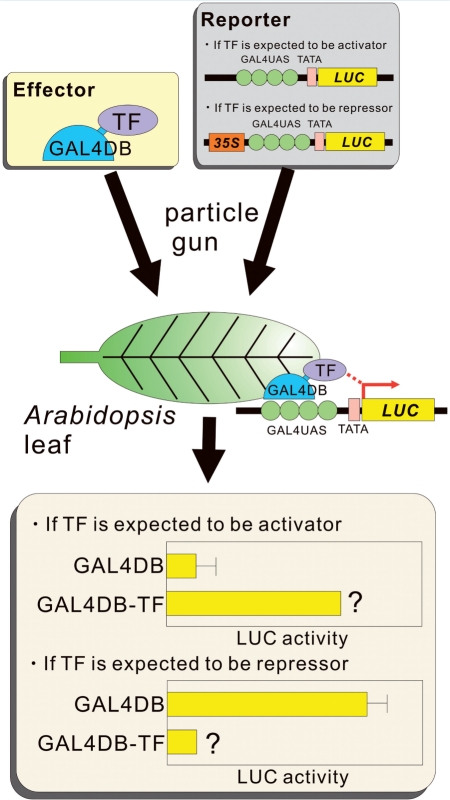

The molecular analysis of TFs involves the characterization of their activation or repression activities. To this end, analysis using reporter and effector genes is often employed (Ohta et al. 2001; Fig. 1). A commonly used effector gene consists of a chimeric construct, in which a TF-coding sequence is fused to that of a heterogeneous DBD, such as the GAL4 DNA-binding domain (GAL4DB) from yeast, and which is driven by a strong promoter, such as cauliflower mosaic virus (CaMV) 35S. The reporter gene is usually the firefly luciferase (LUC) or Escherichia coli β-glucuronidase (GUS) gene, which is driven by a minimal promoter with upstream repeated cis-elements, such as the binding sequence of the GAL4DB. Another reporter construct, containing a constitutively expressed reporter, such as sea pansy LUC, is used as an internal control (reference). These reporter, effector and reference constructs are transiently co-expressed by particle bombardment of leaf tissues or by polyethylene glycol-mediated transformation of leaf protoplasts or cultured cells. By assaying the activity of the reporter gene following co-expression of the effector gene, the activation activity of a TF can be examined. A transient expression assay using particle bombardment into leaf tissue is simple and reproducible and has several advantages for analyzing the molecular function of TFs (Ueki et al. 2009). Once a TF is identified as a transcriptional activator, the AD can be determined by investigating the activities of truncated TF proteins. Activation activity of TFs can also be assessed in a yeast system. However, ADs identified in a plant system can sometimes differ from those identified in a yeast system (Ohta et al. 2000).

Fig. 1.

Schematic drawing summarizing the molecular analysis of TFs. The effector and reporter plasmids are co-introduced into Arabidopsis leaf by particle bombardment. Reporter activity is measured to examine whether a TF is an activator or a repressor.

Some Arabidopsis TFs are known to act as transcriptional repressors. To analyze whether the TF of interest is a repressor, the repressive activity of the effector construct, using a reporter gene containing a transcriptional enhancer in the promoter, such as that of the CaMV 35S promoter, is utilized. As in the case of an activator, by analyzing the repressive activities of truncated proteins, it is possible to identify the RD of the TF. This strategy for the molecular analysis of TFs is summarized in Fig. 1.

Expression analysis

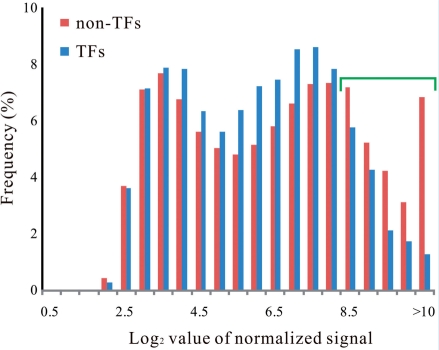

Expression analysis aims to identify the cells and tissues that express TFs and to define the levels and temporal patterns of expression. As described above, the expression profile of each TF gene has been analyzed for various tissues, under certain conditions and chemical treatments by large-scale microarray analyses (Schmid et al. 2005, Kilian et al. 2007, Goda et al. 2008). Although it has long been believed that the expression levels of TFs are lower relative to those of non-TFs, these large-scale microarray data revealed that this is not always the case. The distribution of signal values was not significantly different between TFs and non-TFs. Although the frequency of non-TF genes that are expressed at extremely high levels is higher than that of TFs, the frequency of genes expressed at low levels is almost the same between TFs and non-TFs (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2 .

Histogram from a large-scale microarray experiment showing distributions of averaged, normalized signals of 21,099 non-TF genes and 2,155 TF genes among a ‘developmental set’ of genes (Schmid et al. 2005). The distribution is not drastically different between non-TFs and TFs. The frequency of highly expressed genes is higher in non-TFs than in TFs (indicated by a green bracket).

Analysis of gene expression by quantitative reverse transcription–PCR (RT–PCR) has become routine, especially in the last decade. However, many concerns about quantitative RT–PCR have recently been pointed out (Czechowski et al. 2005, Gutierrez et al. 2008, Udvardi et al. 2008). In particular, selection of a reference gene(s) is a critical issue. Although traditional housekeeping genes, such as ACT2, TUB6, EF-1α, UBQ10 and cytosolic GAPDH, are often used as a reference, they are not always uniformly expressed in various tissues (Czechowski et al. 2005). Thus, for quantitative RT–PCR analysis, it is important to select a suitable reference gene.

Promoter–reporter experiments using GUS or green fluorescent protein (GFP) are often employed as a powerful tool to obtain detailed expression profiles. However, it is well known that exogenous promoter activities do not always reflect the genuine expression pattern of a gene of interest due to post-transcriptional regulation and/or lack of necessary gene regulatory elements in the promoter. Overestimation would occur in the case of miRNA target genes. In contrast, underestimation would occur if the promoter region used in the experiment does not contain the cis-element(s) required for sufficient expression of the gene. Although promoters of 3 kb or longer are empirically considered to be sufficient to reflect accurate expression in Arabidopsis, some genes contain regulatory elements in their introns (Deyholos and Sieburth 2000) or in downstream or upstream regions, at significant distances from the coding region. For the accurate profiling of expression patterns, it is recommended to use the largest genomic fragment possible, containing upstream and downstream regions, in which the GUS or GFP gene should be inserted into the coding region to generate a fusion protein. Such a construct would be expected to reflect an accurate expression pattern, even if the gene is a target of miRNA (Wu and Poethig 2006, Schwarz et al. 2008).

In situ RNA hybridization is a reliable method to examine the gene expression profile at the cellular level. Immunohistochemistry may be more suitable to analyze cells where the protein product actually works, because some TFs, such as SHORT-ROOT (SHR), CPC and KNAT1, are known to move from cell to cell (Nakajima et al. 2001, Kim et al. 2003, Kurata et al. 2005). However, these methods are not suitable for obtaining expression profiles at the organ level or for high-throughput analysis.

Phenotypic analysis

Phenotypic analysis of TFs involves the identification of a phenotype that is regulated by a TF. For this analysis, it is necessary to obtain mutants or transgenic plants with informative phenotypes that lead to the identification of biological function of TFs. As mentioned above, a number of plant TFs act as key regulators and directly regulate various plant functions. Therefore, manipulation of TFs provides the possibility to induce phenotype changes more efficiently than the manipulation of other factors. Phenotypes include not only visible morphological and metabolic changes, but also ‘hidden’ changes that are only visible under certain conditions. To induce phenotypic changes by manipulating TFs, two strategies, ‘gain of function’ and ‘loss of function’, are usually applied. The ‘gain-of-function’ method induces an abnormal phenotype by the ectopic expression of a TF gene using a constitutive promoter, such as the CaMV 35S promoter, or by enhancing an activating activity of a TF by fusion of an exogenous AD, such as the VP16 AD of herpes simplex virus. Conditional expression of a gene using an inducible promoter or a hormone receptor system (Severin and Schoffl 1990, Takahashi et al. 1992, Aoyama and Chua 1997, Caddick et al. 1998, Zuo et al. 2000) is also a useful strategy when overexpression of a TF induces lethality. By observing the phenotype induced by ectopic expression, the protein function of a TF can be deduced. For example, ectopic expression of PAP1, AtMYB23 and NST1 induces accumulation of anthocyanin, excessive trichomes and ectopic secondary wall thickenings, respectively, suggesting that the proteins encoded by these genes have the ability to induce these respective phenotypes (Kirik et al. 2001, Esch et al. 2004, Mitsuda et al. 2005). For systematic gain-of-function analysis in Arabidopsis and rice, the full-length cDNA overexpressor gene hunting system (FOX-hunting) has been applied at a large scale (Ichikawa et al. 2006, Kondou et al. 2009). This gain-of-function assay is easy and simple to apply and is effective for many genes; however, this system does not always reflect the native function of TFs due to ectopic induction. In addition, ectopic expression of a TF often fails to induce an informative phenotype, suggesting that ectopic expression of a single TF might be inadequate to activate the expression of target genes. Other factors that cooperate with the TF may regulate the expression of target genes.

In comparison with gain-of-function analysis, phenotypes induced by loss-of-function analysis should more directly reflect native gene function. For loss-of-function analysis, inactivation of genes or of a gene’s activity is necessary. T-DNA-tagged lines of most Arabidopsis genes, in which the large T-DNA fragment is inserted into them, are now available (Alonso et al. 2003). T-DNA-tagged lines for genes of interest can be searched for in the T-DNA express database (http://signal.salk.edu/cgi-bin/tdnaexpress) and can be retrieved from the Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center (ABRC) and the European Arabidopsis Stock Centre (NASC). However, a significant number of genes, especially genes with short coding regions, have no tag in the coding region. Furthermore, tagged lines in which a tag is inserted into the 3′ side of a coding region or into an intron are frequently not null alleles. Expression of complementary RNA, namely antisenese RNA and RNA interference (RNAi) strategies, is frequently adopted for the inactivation of target genes. Furthermore, the use of artificial miRNA (amiRNA) has also been recently proposed (Niu et al. 2006). However, only a small number of transgenic plants show aberrant phenotypes and the phenotype is unstable in many cases.

A major obstacle for loss-of-function approaches is functional gene redundancy. The plant genome has frequently experienced segmental duplication, and Arabidopsis TF genes form large families that share similar DBDs. These domains can have similar DNA-binding specificities, which could act redundantly with other members. Such functional redundancy often interferes with efforts to identify TF functions. To overcome this difficulty, a novel gene silencing system, called Chimeric REpressor Gene-Silencing Technology (CRES-T), was developed (Hiratsu et al. 2003). In the CRES-T system, a chimeric repressor, produced by fusion of a TF to a modified EAR motif plant-specific repression domain (SRDX), dominantly suppresses the expression of target genes over the activity of endogenous and functionally redundant TFs. As a result, the transgenic plant that expresses the chimeric repressor exhibits a phenotype similar to the loss-of-function phenotype of the TF and of its functionally redundant paralog, even if there are endogenous functionally redundant TFs. It should be noted, however, that an abnormal phenotype induced by the chimeric repressor driven by a constitutive promoter does not always reflect its naive function. For example, the chimeric repressor of a TF driven by a constitutive promoter sometimes induces an aberrant phenotype where the native TF is not expressed. Therefore, the expression of a chimeric repressor, driven by its own promoter, is desirable to investigate the precise biological function of a TF. The CRES-T system functions successfully for various TFs and has succeeded in inducing distinct phenotypes that have not been identified with single gene knockout lines or by the expression of complementary RNA (Kubo et al. 2005, Mitsuda et al. 2005, Ishida et al. 2007, Ito et al. 2007, Koyama et al. 2007, Groszmann et al. 2008, Kawamura et al. 2008, Soyano et al. 2008). In addition, this system is available not only for dicots, such as Arabidopsis, but also for monocots, such as rice (Mitsuda et al. 2006). The advantages of the CRES-T system are that (i) it is simple; (ii) it works in a dominant fashion; and (iii) cloning of the gene of interest is not necessarily required when applied to species for which the genome sequence is unavailable. The CRES-T construct, which is based on Arabidopsis TFs, can work effectively in other species, sometimes without any modification (unpublished result). This is a great benefit for the application of this technology to agronomically important crops. The CRES-T system is also applicable to traditional forward genetic strategies. Screening interesting phenotypes from the seed pool of CRES-T lines would find novel factors because a chimeric repressor works dominantly, even in the presence of functionally redundant TFs.

The CRES-T system is less effective for transcriptional repressors because it is expected that the CRES-T line would have a similar or enhanced phenotype compared with that of ectopic overexpression lines. For loss-of-function analysis of the repressor, the expression of a fusion protein between the repressor and the VP16 AD might be effective. Because a strong RD may overcome the effect of VP16 and the fusion molecule behaves as a repressor (Ohta et al. 2001), the RD should, if possible, be removed from the construct.

Network analysis

Unraveling the entire transcriptional regulatory network is one of the final goals of TF research. Experimental approaches toward this end can be classified into genetic and non-genetic approaches. Traditional genetic approaches, namely analysis of mutant lines, provide high quality information if mutants or transgenic plants provide informative phenotypes. To find suppressors that reduce the phenotypic abnormality of mutant or transgenic plants is one of the most reliable approaches to identify gene(s) acting downstream of the gene of interest. For example, transgenic plants expressing TCP3SRDX are very small and have a disordered appearance (Koyama et al. 2007). This aberrant phenotype was reduced drastically when crossed to a mutant of CUC genes, suggesting that TCP TFs negatively regulate CUC genes (Koyama et al. 2007). The fruitfull (ful) mutant bears a very short silique full of seeds and FUL encodes a MADS-box TF (Gu et al. 1998). The phenotype of ful can be mostly restored by introducing a mutation into INDEHISCENT (IND), SHATTERPROOF1 (SHP1) and SHP2, suggesting that FUL negatively regulates the expression of IND, SHP1 and SHP2 (Liljegren et al. 2004). The use of a promoter–reporter also helps to reveal genetic relationships. For example, an enhancer trap line of CUC1 (the expression of GFP is driven by the CUC1 promoter) showed ectopic fluorescence after the introduction of 35S:TCP3SRDX, supporting the genetic relationship that TCPs negatively regulate CUCs (Koyama et al. 2007). Promoter activity of IND is ectopically expanded in plants overexpressing SHP1 and SHP2, suggesting that SHP1 and SHP2 positively regulate the expression of IND (Liljegren et al. 2000, Liljegren et al. 2004).

Non-genetic methods, especially large-scale high-throughput experiments, have developed rapidly in recent years. The most successfully applied method to find TFs that act upstream of the TF of interest is yeast one-hybrid screening (Y1H) (Luo et al. 1996). This system uses a tandem repeat of a putative short cis-element as bait to screen a cDNA library prepared for Y1H. However, it is laborious to identify a putative short cis-element from a promoter region. Another weakness of this system is the cDNA library. Normally, cDNA libraries are not normalized, and include unnecessary non-TF genes, and only one-sixth of the library is successfully fused, in-frame, to the transcriptional AD encoded in the vector. To overcome these problems, a novel approach was introduced, in which a promoter region of <500 bp was directly employed as bait and the cDNA library consisted only of TFs (Deplancke et al. 2006, Pruneda-Paz et al. 2009). A novel component of the circadian system, CCA1 HIKING EXPEDITION (CHE)/TCP21 was identified as a direct regulator of CIRCADIAN CLOCK ASSOCIATED 1 (CCA1) by this approach (Pruneda-Paz et al. 2009). These strategies have great potential to contribute to the analysis of gene regulatory networks.

To uncover genes acting downstream of a TF, microarray approaches are the most suitable. The correct statistical analysis of microarray data is critical to exploit the power of this technology. To compare microarray data among two or more samples, cross-chip normalization is required. This normalization procedure normally contains two steps. Median scaling is a method in which each signal value is divided by the median of all signals within each array. The resulting median signal is scaled to 1 for each array. It should be noted, however, that a recent study reported that 75th percentile scaling is more robust than median scaling (Shippy et al. 2006). Quantile normalization is an optional non-linear conversion of signal values, making signal distribution of all arrays the same (Bolstad et al. 2003). Some data processing software, such as RMA (Irizarry et al. 2003) and GCRMA (Seo et al. 2006) for Affymetrix GeneChip arrays, contain quantile normalization as a default. To select differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between two samples, statistical significance (P-value), calculated by the t-test, is often used as a cut-off criterion, in combination with a fold change threshold. It should be noted that experiments need to be performed at least in triplicate for effective statistical analysis. Furthermore, multiple testing correction was proposed to be needed to control the false discovery rate (FDR) when selecting DEGs (Dudoit et al. 2002). A stepwise correction of the P-value based on P-value rank is often used to overcome this problem (Benjamini and Hochberg 1995). Another method has been proposed to transform a P-value into a Q-value to represent an FDR when the value is used as a threshold (Storey and Tibshirani 2003). One of the basic analyses of microarray data, when comparing two samples, is to find statistically over-represented and under-represented gene groups with specific characteristics among DEGs by statistical tests such as Fisher’s exact test. For example, heat-responsive genes were shown to be apparently over-represented among up-regulated genes in a plant overexpressing a constitutively active form of DREB2A, leading to the discovery of cross-talk between the drought stress response, salt stress response and the heat stress response (Sakuma et al. 2006). Microarray experiments are also effective for dissecting distinct roles of related TFs. Rashotte et al. (2006) succeeded in characterizing the precise roles of newly identified CYTOKININ RESPONSE FACTORS (CRFs) by comparing transcriptomes of multiple crf mutants with the double mutant of ARABIDOPSIS RESPONSE REGULATOR 1 (ARR1) and ARR12. Morohashi and Grotewold (2009) proposed distinct roles for GLABRA 1 (GL1) and GL3, which form a heterodimer to regulate trichome initiation.

The identification of direct TF targets plays a central role in unraveling transcriptional regulatory networks. There are several major experimental approaches to achieve this. The TF-binding sequence can be determined using purified protein and random oligonucleotide selection (Wright et al. 1991). It is easy to find genes with determined sequence in their promoters in genome-sequenced species. However, this method is only usable if the TF protein can be purified and the possibility cannot be excluded that the determined sequence does not reflect the actual in vivo binding sequence. Furthermore, this method is not suitable for high-throughput analysis due to the difficulties of protein expression and purification.

The inducible expression of transgenes by a system using a chimeric TF, consisting of a yeast GAL4DB, the transcriptional VP16 AD and the glucocorticoid receptor (GR) or estrogen receptor (ER) has been developed in the last decade (Aoyama and Chua 1997, Zuo et al. 2000). Direct fusion of a TF protein to a GR or ER is sometimes sufficient for TF functional analysis and exploration of TF target genes (Sablowski and Meyerowitz 1998). Expression of downstream genes is rapidly induced after dexamethasone (DEX) or estrogen treatment of the transgenic plant constitutively expressing TF–GR or TF–ER fusion proteins. When the plant is treated simultaneously with DEX and cycloheximide (CHX), which inhibits protein synthesis, expression of the direct TF target gene only is induced. SUPPRESSOR OF OVEREXPRESSION OF CO 1 (SOC1) and FLOWERING LOCUS T (FT) were identified as direct targets of CONSTANS (CO) by this approach (Samach et al. 2000). If this system is combined with microarray approaches or next-generation sequencing technology, direct target genes of TFs can be comprehensively identified. However, it should be noted that the expression of some genes involved in the stress response are induced by DEX and/or CHX treatment.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) is a rapidly emerging technology to identify genomic fragments that bind to a DNA-binding protein (O’Neill and Turner 1996). This method is suitable for confirming that a TF binds directly to the promoter region of a putative target gene. It is considered strong evidence if the promoter region of the putative target gene is enriched in the collected pool of genomic fragments. A combination of this technique with whole genome tiling arrays or next-generation sequencing technology (ChIP-chip or ChIP-seq) has great potential to identify comprehensively the region bound by a TF (reviewed in Buck and Lieb 2004, Jiang and Pugh 2009). Some pioneering studies applying ChIP-chip to plant TFs have already been accomplished (Morohashi and Grotewold 2009, Lee et al. 2007). Another approach, utilizing yeast screening, has been performed to identify comprehensively the genomic regions bound by TFs (Zeng et al. 2008).

Recent development of these technologies allows us to identify putative direct and indirect downstream genes of TFs more easily; nevertheless, the contribution of these genes to a plant’s phenotype should be carefully examined. The challenge of trying to incorporate this vast amount of information into one huge gene regulatory network has been launched under the umbrella of systems biology. AtRegNet (http://arabidopsis.med.ohio-state.edu/RGNet/), hosted in AGRIS, is one of most sophisticated frameworks addressing this issue. It stores information of TF to gene regulations, and users can add original data. In this internet era, ‘collective intelligence’ is expected to facilitate the drawing of the entire picture.

Contribution of TF functional analysis to omics studies

Omics studies include the study of various ‘omes’, such as the transcriptome, proteome, metabolome and phenome. To perform omics studies effectively, it is necessary to prepare useful lines, such as mutant lines, which provide informative phenotypes. In plants, transcriptional regulation plays a major role in the control of gene expression, and a number of plant TFs are known to act as key regulators of various functions. Manipulation of a TF often induces drastic phenotype changes and alters the proteome, metabolome and phenome, in addition to the transcriptome. By clarifying the complete functional network of TFs, it may be possible to predict events in the transcriptome, metabolome and phenome induced by manipulation of a gene of interest. Development of novel innovative tools for functional analysis, in addition to CRES-T, ChIP, microarray analysis and next-generation sequencing, will provide new avenues for the functional analysis of TFs.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at PCP online.

Acknowledgments

We express appreciation to Ms. Yuko Takiguchi for her skillful assistance with computational searches.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- AD

activation domain

- CaMV

cauliflower mosaic virus

- CD

conserved domain

- ChIP

chromatin immunoprecipitation

- CHX

cycloheximide

- CRES-T

chimeric repressor silencing technology

- DBD

DNA

-

binding domain

- DEG

differentially expressed gene

- DEX

dexamethasone

- EAR

ERF-associated amphiphilic repression

- ER

estrogen receptor

- FDR

false discovery rate

- FOX

full-length cDNA overexpressor

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- GO

gene ontology

- GR

glucocorticoid receptor

- GUS

β

-glucuronidase

- LUC

luciferase

- miRNA

microRNA

- PPI

protein

–

protein interaction

- RD

repression domain

- RT–PCR

reverse transcription–PCR

- SRDX

modified EAR motif plant-specific repression domain showing strong repression activity

- ta-siRNA

trans-acting small interfering RNA

- TF

transcription factor

- Y1H

yeast one-hybrid screening

References

- Adkins NL, Hall JA, Georgel PT. GAGA protein: a multi-faceted transcription factor. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2006;84:559–567. doi: 10.1139/o06-062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen MD, Yamasaki K, Ohme-Takagi M, Tateno M, Suzuki M. A novel mode of DNA recognition by a β-sheet revealed by the solution structure of the GCC-box binding domain in complex with DNA. EMBO J. 1998;17:5484–5496. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.18.5484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonso JM, Stepanova AN, Leisse TJ, Kim CJ, Chen H, Shinn P, et al. Genome-wide insertional mutagenesis of Arabidopsis thaliana. Science. 2003;301:653–65. doi: 10.1126/science.1086391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoyama T, Chua NH. A glucocorticoid-mediated transcriptional induction system in transgenic plants. Plant J. 1997;11:605–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1997.11030605.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arabidopsis Genome Initiative. Analysis of the genome sequence of the flowering plant Arabidopsis thaliana. Nature. 2000;408:796–815. doi: 10.1038/35048692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, Botstein D, Butler H, Cherry JM, et al. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Nat. Genet. 2000;25:25–29. doi: 10.1038/75556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Backman TW, Sullivan CM, Cumbie JS, Miller ZA, Chapman EJ, Fahlgren N, et al. Update of ASRP: the Arabidopsis small RNA project database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D982–D985. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey TL, Williams N, Misleh C, Li WW. MEME: discovering and analyzing DNA and protein sequence motifs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:W369–W373. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett T, Troup DB, Wilhite SE, Ledoux P, Rudnev D, Evangelista C, et al. NCBI GEO: mining tens of millions of expression profiles—database and tools update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:D760–D765. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Bolstad BM, Irizarry RA, Astrand M, Speed TP. A comparison of normalization methods for high density oligonucleotide array data based on variance and bias. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:185–1. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/19.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buck MJ, Lieb JD. ChIP-chip: considerations for the design, analysis and application of genome-wide chromatin immunoprecipitation experiments. Genomics. 2004;83:349–3. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2003.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caddick MX, Greenland AJ, Jepson I, Krause KP, Qu N, Riddell KV, et al. An ethanol inducible gene switch for plants used to manipulate carbon metabolism. Nat. Biotechnol. 1998;16:177–1. doi: 10.1038/nbt0298-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craigon DJ, James N, Okyere J, Higgins J, Jotham J, May S. NASCArrays: a repository for microarray data generated by NASC’s transcriptomics service. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:D575–D57. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui J, Li P, Li G, Xu F, Zhao C, Li Y, et al. AtPID: Arabidopsis thaliana protein interactome database—an integrative platform for plant systems biology. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D999–D. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czechowski T, Stitt M, Altmann T, Udvardi MK, Scheible WR. Genome-wide identification and testing of superior reference genes for transcript normalization in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2005;139:5–17. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.063743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davuluri RV, Sun H, Palaniswamy SK, Matthews N, Molina C, Kurtz M, et al. AGRIS: Arabidopsis gene regulatory information server, an information resource of Arabidopsis cis-regulatory elements and transcription factors. BMC Bioinformatics. 2003;4:25. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-4-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deplancke B, Mukhopadhyay A, Ao W, Elewa AM, Grove CA, Martinez, N. J, et al. A gene-centered C. elegans protein–DNA interaction network. Cell. 2006;125:1193–1. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.04.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deyholos MK, Sieburth LE. Separable whorl-specific expression and negative regulation by enhancer elements within the AGAMOUS second intron. Plant Cell. 2000;12:1799–1. doi: 10.1105/tpc.12.10.1799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Döring P, Treuter E, Kistner C, Lyck R, Chen A, Nover L. The role of AHA motifs in the activator function of tomato heat stress transcription factors HsfA1 and HsfA2. Plant Cell. 2000;12:265–278. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudoit S, Yang YH, Speed TP, Callow MJ. Statistical methods for identifying differentially expressed genes in replicated cDNA microarray experiments. Stat. Sin. 2002;12:111–1. [Google Scholar]

- Emanuelsson O, Nielsen H, Brunak S, von Heijne G. Predicting subcellular localization of proteins based on their N-terminal amino acid sequence. J. Mol. Biol. 2000;300:1005–10. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst HA, Olsen AN, Larsen S, Lo Leggio L. Structure of the conserved domain of ANAC, a member of the NAC family of transcription factors. EMBO Rep. 2004;5:297–303. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esch JJ, Chen MA, Hillestad M, Marks MD. Comparison of TRY and the closely related at1g01380 gene in controlling Arabidopsis trichome patterning. Plant J. 2004;40:860–869. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02259.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furihata T, Maruyama K, Fujita Y, Umezawa T, Yoshida R, Shinozaki K, et al. Abscisic acid-dependent multisite phosphorylation regulates the activity of a transcription activator AREB1. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:1988–19. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505667103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geisler-Lee J, O.’Toole N, Ammar R, Provart NJ, Millar AH, Geisler M. A predicted interactome for Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2007;145:317–3. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.103465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goda H, Sasaki E, Akiyama K, Maruyama-Nakashita A, Nakabayashi K, Li W, et al. The atGenExpress hormone and chemical treatment data set: experimental design, data evaluation, model data analysis and data access. Plant J. 2008;55:526–5. doi: 10.1111/j.0960-7412.2008.03510.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grennan AK. Genevestigator. Facilitating web-based gene-expression analysis. Plant Physiol. 2006;141:1164–1166. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.900198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groszmann M, Paicu T, Smyth DR. Functional domains of SPATULA, a bHLH transcription factor involved in carpel and fruit development in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2008;55:40–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03469.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu Q, Ferrándiz C, Yanofsky MF, Martienssen R. The FRUITFULL MADS-box gene mediates cell differentiation during Arabidopsis fruit development. 1998;125:1509–1517. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.8.1509. Development. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo A, He K, Liu D, Bai S, Gu X, Wei L, et al. DATF: a database of Arabidopsis transcription factors. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:2568–256. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustafson AM, Allen E, Givan S, Smith D, Carrington JC, Kasschau KD. ASRP: the Arabidopsis small RNA project database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:D637–D6. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez L, Mauriat M, Pelloux J, Bellini C, Van Wuytswinkel O. Towards a systematic validation of references in real-time rt-PCR. Plant Cell. 2008;20:1734–173. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.059774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall DA, Zhu H, Zhu X, Royce T, Gerstein M, Snyder M. Regulation of gene expression by a metabolic enzyme. Science. 2004;306:482–48. doi: 10.1126/science.1096773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He JX, Gendron JM, Yang Y, Li J, Wang ZY. The GSK3-like kinase BIN2 phosphorylates and destabilizes BZR1, a positive regulator of the brassinosteroid signaling pathway in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:10185–101. doi: 10.1073/pnas.152342599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heazlewood JL, Verboom RE, Tonti-Filippini J, Small I, Millar AH. SUBA: the Arabidopsis subcellular database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:D213–D21. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibara K, Karim MR, Takada S, Taoka K, Furutani M, Aida M, et al. Arabidopsis CUP-SHAPED COTYLEDON3 regulates postembryonic shoot meristem and organ boundary formation. Plant Cell. 2006;18:2946–29. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.045716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higo K, Ugawa Y, Iwamoto M, Korenaga T. Plant cis-acting regulatory DNA elements (PLACE) database: 1999. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:297–300. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.1.297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirai MY, Sugiyama K, Sawada Y, Tohge T, Obayashi T, Suzuki A, et al. Omics-based identification of Arabidopsis Myb transcrip-tion factors regulating aliphatic glucosinolate biosynthesis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:6478–64. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611629104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiratsu K, Matsui K, Koyama T, Ohme-Takagi M. Dominant repression of target genes by chimeric repressors that include the EAR motif, a repression domain, in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2003;34:733–73. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2003.01759.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiratsu K, Mitsuda N, Matsui K, Ohme-Takagi M. Identification of the minimal repression domain of SUPERMAN shows that the DLELRL hexapeptide is both necessary and sufficient for repression of transcription in Arabidopsis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004;321:172–17. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.06.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honma T, Goto K. Complexes of MADS-box proteins are sufficient to convert leaves into floral organs. Nature. 2001;409:525–52. doi: 10.1038/35054083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton P, Park KJ, Obayashi T, Fujita N, Harada H, Adams-Collier CJ, et al. WoLF PSORT: protein localization predictor. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:W585–W58. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua S, Sun Z. Support vector machine approach for protein subcellular localization prediction. Bioinformatics. 2001;17:721–72. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.8.721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichikawa T, Nakazawa M, Kawashima M, Iizumi H, Kuroda H, Kondou Y, et al. The FOX hunting system: an alternative gain-of-function gene hunting technique. Plant J. 2006;48:974–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02924.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iida K, Seki M, Sakurai T, Satou M, Akiyama K, Toyoda T, et al. RARTF: database and tools for complete sets of Arabidopsis transcription factors. DNA Res. 2005;12:247–2. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dsi011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda M, Ohme-Takagi M. A novel group of transcriptional repressors in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Physiol. 2009;50:970–975. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcp048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irizarry RA, Hobbs B, Collin F, Beazer-Barclay YD, Antonellis KJ, Scherf U, et al. Exploration, normalization and summaries of high density oligonucleotide array probe level data. Biostatistics. 2003;4:249–2. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/4.2.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishida T, Hattori S, Sano R, Inoue K, Shirano Y, Hayashi H, et al. Arabidopsis TRANSPARENT TESTA GLABRA2 is directly regulated by R2R3 MYB transcription factors and is involved in regulation of GLABRA2 transcription in epidermal differentiation. Plant Cell. 2007;19:2531–25. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.052274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito T, Nagata N, Yoshiba Y, Ohme-Takagi M, Ma H, Shinozaki K. Arabidopsis MALE STERILITY1 encodes a PHD-type transcription factor and regulates pollen and tapetum development. Plant Cell. 2007;19:3549–35. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.054536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang C, Pugh BF. Nucleosome positioning and gene regulation: advances through genomics. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2009;10:161–72. doi: 10.1038/nrg2522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagaya Y, Ohmiya K, Hattori T. RAV1, a novel DNA-binding protein, binds to bipartite recognition sequence through two distinct DNA-binding domains uniquely found in higher plants. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:470–47. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.2.470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawamura M, Ito S, Nakamichi N, Yamashino T, Mizuno T. The function of the clock-associated transcriptional regulator CCA1 (CIRCADIAN CLOCK-ASSOCIATED 1) in Arabidopsis thaliana. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2008;72:1307–13. doi: 10.1271/bbb.70804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerrien S, Alam-Faruque Y, Aranda B, Bancarz I, Bridge A, Derow C, et al. IntAct—open source resource for molecular interaction data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:D561–D565. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilian J, Whitehead D, Horak J, Wanke D, Weinl S, Batistic O, et al. The atGenExpress global stress expression data set: protocols, evaluation and model data analysis of UV-B light, drought and cold stress responses. Plant J. 2007;50:347–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03052.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JH, Woo HR, Kim J, Lim PO, Lee IC, Choi SH, et al. Trifurcate feed-forward regulation of age-dependent cell death involving miR164 in Arabidopsis. Science. 2009;323:1053–105. doi: 10.1126/science.1166386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JY, Yuan Z, Jackson D. Developmental regulation and significance of KNOX protein trafficking in Arabidopsis. Development. 2003;130:4351–43. doi: 10.1242/dev.00618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SG, Lee AK, Yoon HK, Park CM. A membrane-bound NAC transcription factor NTL8 regulates gibberellic acid-mediated salt signaling in Arabidopsis seed germination. Plant J. 2008;55:77–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03493.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YS, Kim SG, Park JE, Park HY, Lim MH, Chua NH, et al. A membrane-bound NAC transcription factor regulates cell division in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2006;18:3132–31. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.043018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirik V, Schnittger A, Radchuk V, Adler K, Hulskamp M, Baumlein H. Ectopic expression of the Arabidopsis AtMYB23 gene induces differentiation of trichome cells. Dev. Biol. 2001;235:366–377. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondou Y, Higuchi M, Takahashi S, Sakurai T, Ichikawa T, Kuroda H, et al. Systematic approaches to using the FOX hunting system to identify useful rice genes. Plant J. 2009;57:883–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03733.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koyama T, Furutani M, Tasaka M, Ohme-Takagi M. TCP transcription factors control the morphology of shoot lateral organs via negative regulation of the expression of boundary-specific genes in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2007;19:473–4. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.044792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubo M, Udagawa M, Nishikubo N, Horiguchi G, Yamaguchi M, Ito J, et al. Transcription switches for protoxylem and metaxylem vessel formation. Genes Dev. 2005;19:1855–18. doi: 10.1101/gad.1331305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurata T, Ishida T, Kawabata-Awai C, Noguchi M, Hattori S, Sano R, et al. Cell-to-cell movement of the CAPRICE protein in Arabidopsis root epidermal cell differentiation. Development. 2005;132:5387–53. doi: 10.1242/dev.02139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larue CT, Wen J, Walker JC. A microRNA–transcription factor module regulates lateral organ size and patterning in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2009;58:450–463. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2009.03796.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, He K, Stolc V, Lee H, Figueroa P, Gao, Y., et al. Analysis of transcription factor HY5 genomic binding sites revealed its hierarchical role in light regulation of development. Plant Cell. 2007;19:731–749. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.047688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liljegren SJ, Ditta GS, Eshed Y, Savidge B, Bowman JL, Yanofsky MF. SHATTERPROOF MADS-box genes control seed dispersal in Arabidopsis. Nature. 2000;404:766–7. doi: 10.1038/35008089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liljegren SJ, Roeder A.HK, Kempin SA, Gremski K, Ostergaard L, Guimil S, et al. Control of fruit patterning in Arabidopsis by INDEHISCENT. Cell. 2004;116:843–8. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00217-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long JA, Ohno C, Smith ZR, Meyerowitz EM. TOPLESS regulates apical embryonic fate in Arabidopsis. Science. 2006;312:1520–1523. doi: 10.1126/science.1123841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Y, Vijaychander S, Stile J, Zhu L. Cloning and analysis of DNA-binding proteins by yeast one-hybrid and one-two-hybrid systems. Biotechniques. 1996;20:564–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsui K, Umemura Y, Ohme-Takagi M. AtMYBL2, a protein with a single MYB domain, acts as a negative regulator of anthocyanin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2008;55:954–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03565.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao Y, Laun T, Zimmermann P, Zentgraf U. Targets of the WRKY53 transcription factor and its role during leaf senescence in Arabidopsis. Plant Mol. Biol. 2004;55:853–857. doi: 10.1007/s11103-004-2142-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitsuda N, Hiratsu K, Todaka D, Nakashima K, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K, Ohme-Takagi M. Efficient production of male and female sterile plants by expression of a chimeric repressor in Arabidopsis and rice. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2006;4:325–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2006.00184.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitsuda N, Seki M, Shinozaki K, Ohme-Takagi M. The NAC transcription factors NST1 and NST2 of Arabidopsis regulate secondary wall thickenings and are required for anther dehiscence. Plant Cell. 2005;17:2993–3006. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.036004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morohashi K, Grotewold E. A systems approach reveals regulatory circuitry for Arabidopsis trichome initiation by the GL3 and GL1 selectors. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000396.. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima K, Sena G, Nawy T, Benfy PN. Intracellular movement of the putative transcription factor SHR in root patterning. Nature. 2001;413:307–3. doi: 10.1038/35095061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niu QW, Lin SS, Reyes JL, Chen KC, Wu HW, Yeh SD, et al. Expression of artificial microRNAs in transgenic Arabidopsis thaliana confers virus resistance. Nat. Biotechnol. 2006;24:1420–142. doi: 10.1038/nbt1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill LP, Turner BM. Immunoprecipitation of chromatin. Methods Enzymol. 1996;274:189–1. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(96)74017-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obayashi T, Hayashi S, Saeki M, Ohta H, Kinoshita K. ATTED-II provides coexpressed gene networks for Arabidopsis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D987–D9. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohta M, Matsui K, Hiratsu K, Shinshi H, Ohme-Takagi M. Repression domains of class II ERF transcriptional repressors share an essential motif for active repression. Plant Cell. 2001;13:1959–19. doi: 10.1105/TPC.010127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohta M, Ohme-Takagi M, Shinshi H. Three ethylene-responsive transcription factors in tobacco with distinct transactivation functions. Plant J. 2000;22:29–38. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2000.00709.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ori N, Cohen AR, Etzioni A, Brand A, Yanai O, Shleizer S, et al. Regulation of LANCEOLATE by miR319 is required for compound-leaf development in tomato. Nat. Genet. 2007;39:787–7. doi: 10.1038/ng2036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouellet F, Overvoorde PJ, Theologis A. IAA17/AXR3. Biochemical insight into an auxin mutant phenotype. Plant Cell. 2001;13:829–8. doi: 10.1105/tpc.13.4.829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palatnik JF, Allen E, Wu X, Schommer C, Schwab R, Carrington, J. C, et al. Control of leaf morphogenesis by microRNAs. Nature. 2003;425:257–2. doi: 10.1038/nature01958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkinson H, Kapushesky M, Kolesnikov N, Rustici G, Shojatalab M, Abeygunawardena N, et al. ArrayExpress update—from an archive of functional genomics experiments to the atlas of gene expression. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D868–D8. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruneda-Paz JL, Breton G, Para A, Kay SA. A functional genomics approach reveals CHE as a component of the Arabidopsis circadian clock. Science. 2009;323:1481–148. doi: 10.1126/science.1167206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quevillon E, Silventoinen V, Pillai S, Harte N, Mulder N, Apweiler R, et al. InterProScan: protein domains identifier. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:W116–W1. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rashotte AM, Mason MG, Hutchison CE, Ferreira FJ, Schaller GE, Kieber JJ. A subset of Arabidopsis AP2 transcription factors mediates cytokinin responses in concert with a two-component pathway. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:11081–1108. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602038103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandran V, Chen X. Small RNA metabolism in Arabidopsis. Trends Plant Sci. 2008;13:368–374. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2008.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riano-Pachon DM, Ruzicic S, Dreyer I, Mueller-Roeber B. PlnTFDB: an integrative plant transcription factor database. BMC Bioinformatics. 2007;8:42.. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-8-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riechmann JL, Krizek BA, Meyerowitz EM. Dimerization specificity of Arabidopsis MADS domain homeotic proteins APETALA1, APETALA3, PISTILLATA and AGAMOUS. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:4793–4798. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.10.4793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]