Abstract

Glucosinolates (GSLs) are secondary metabolites in Brassicaceae plants synthesized from amino acids. Methionine-derived GSLs (Met-GSLs) with diverse side chains of various lengths are the major GSLs in Arabidopsis. Methionine chain elongation enzymes are responsible for variations in chain length in Met-GSL biosynthesis. The genes encoding methionine chain elongation enzymes are considered to have been recruited from the leucine biosynthetic pathway in the course of evolution. Among them, the genes encoding methylthioalkylmalate synthases and aminotransferases have been identified; however, the remaining genes that encode methylthioalkylmalate isomerase (MAM-I) and methylthioalkylmalate dehydro-genase (MAM-D) remain to be identified. In a previous study based on transcriptome co-expression analysis, we identified candidate genes for the large subunit of MAM-I and MAM-D. In this study, we confirmed their predicted functions by targeted GSL analysis of the knockout mutants, and named the respective genes MAM-IL1/AtleuC1 and MAM-D1/AtIMD1. Metabolic profiling of the knockout mutants of methionine chain elongation enzymes, conducted by means of widely targeted metabolomics, implied that these enzymes have roles in controlling metabolism from methionine to primary and methionine-related secondary metabolites. As shown here, an omics-based approach is an efficient strategy for the functional elucidation of genes involved in metabolism.

Keywords: Chain elongation, Gene function, Glucosinolate, High throughput, Methionine, Widely targeted metabolomics

Introduction

Plants are sessile, and hence they have evolved mechanisms to cope with various environmental changes without moving away from where they are settled. Production of secondary metabolites is one such mechanism that plants use to protect themselves from biotic stresses such as attack by pathogens and herbivores, and abiotic stresses such as drought, UV and cold. Under stress conditions plants synthesize chemically diverse secondary metabolites derived from primary metabolites, including amino acids and sugars. In general, primary metabolites have fundamental functions in every aspect of life, and hence primary metabolism is regulated to be robust against environmental perturbation. Metabolic flux in primary metabolism must be fine-tuned at various levels, namely transcription, translation, protein turnover and protein modification. On the other hand, a major role for secondary metabolism should be to supply the metabolites that have specific biological functions (e.g. insect repellents, UV protectants and cryoprotectants) in response to environmental stimuli. Hence, secondary metabolism is regulated to respond dynamically to environmental changes. Transcriptional regulation of a whole pathway seems to be reasonable for this purpose. Actually, sets of genes involved in some metabolic pathways for secondary metabolites, such as alkaloids, flavonoids and glucosinolates (GSLs), are each regulated by a small number of transcription factors (Gantet and Memelink 2002, Yan and Chen 2007). Because transcriptional regulation of secondary metabolism is now better characterized in the era of molecular biology, we think that the next challenge in the study of plant metabolism will be to elucidate regulatory mechanisms of metabolic flux from primary to secondary metabolism. Regulation at metabolic branching points from primary to secondary metabolism is quite important in order to control metabolic flux to secondary metabolism.

To understand the complicated regulatory mechanisms of plant metabolism, it is first necessary to identify genes involved in metabolism. In the past decade, genome sequencing of model plants has been completed, and microarray techniques for transcriptome analyses have been established. Since Arabidopsis transcriptome data were systematically acquired and publicly released by AtGenExpress (Schmid et al. 2005, Kilian et al. 2007, Goda et al. 2008) and NASCArrays (Craigon et al. 2004), co-expression analysis based on these data sets has become a powerful tool to elucidate gene function (Aoki et al. 2007, Saito et al. 2008). The principle of co-expression analysis is a simple assumption that the genes involved in the same biological function are regulated coordinately under the same regulatory mechanism. As mentioned above, the metabolic pathways of some secondary metabolites are regulated by a small number of transcription factors. Since secondary metabolism supplies the specific metabolites in response to environmental stimuli, the regulatory mechanisms controlling secondary metabolic pathways are likely to be coordinately controlled by a small number of transcription factors. Hence, co-expression analysis was a powerful technique for identifying sets of candidate genes involved in secondary metabolism.

In our previous co-expression studies we predicted and identified the genes involved in the biosynthesis of GSLs, secondary metabolites specific to the order Capparales (Hirai et al. 2005, Hirai et al. 2007, Hirai and Saito 2008, Hirai 2009). GSLs are synthesized from one of eight amino acids, methionine, tryptophan, phenylalanine, isoleucine, leucine, valine, tyrosine or alanine (Fahey et al. 2001, Grubb and Abel 2006, Halkier and Gershenzon 2006). Approximately 140 molecular species have been reported in the Capparales. Among them, at least 36 molecular species derived from methionine, tryptophan, phenylalnine and leucine have been found so far in Arabidopsis (Wittstock and Halkier 2002, D’Auria and Gershenzon 2005). By co-expression analysis of Arabidopsis genes, we found that those involved in methionine-derived GSL (Met-GSL) biosynthesis are co-expressed, and we could predict novel genes encoding the enzymes and the transcription factors involved in Met-GSL biosynthesis (Hirai et al. 2005, Hirai et al. 2007, Hirai and Saito 2008, Hirai 2009).

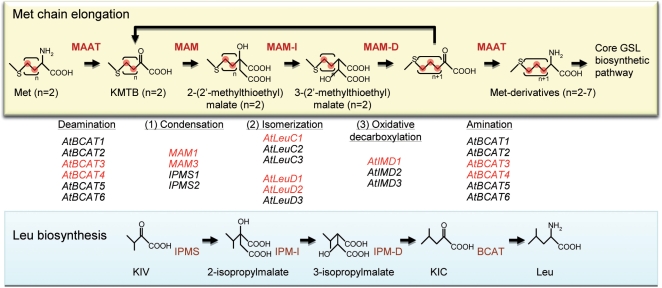

During Met-GSL biosynthesis, methioine is subjected to side chain elongation cycles before entering the GSL core biosynthetic pathway. Chain elongation proceeds through three steps of cyclic reactions [(i) condensation with acetyl-CoA; (ii) isomerization; and (iii) oxidative decarboxylation] and transamination reactions that are similar to the reactions in leucine biosynthesis (Fig. 1). Thus, the enzymes committed to methionine chain elongation and leucine biosynthesis are presumably encoded by homologous genes belonging to the same gene families as follows (Hirai et al. 2007): (i) methylthioalkylmalate synthase (MAM) and isopropylmalate synthase (IPMS) by four genes; (ii) the large subunit of methylthioalkylmalate isomerase (MAM-IL) and that of isopropylmalate isomerase (IPM-IL) by three genes (designated AtLeuCs), and the small subunit of methylthioalkylmalate isomerase (MAM-IS) and that of isopropylmalate isomerase (IPM-IS) by three genes (designated AtLeuDs); (iii) methylthioalkylmalate dehydrogenase (MAM-D) and isopropylmalate dehydrogenase (IPM-D) by three genes [AtIMD genes (Nozawa et al. 2005)]; (iv) and methionine analog aminotransferase (MAAT) and branched-chain amino acid aminotransferase (BCAT) by six genes (Fig. 1). Of these 19 genes, MAM1 (At5g23010) and MAM3 (At5g23020) have been functionally identified as coding for the MAM involved in methionine chain elongation (Kroymann et al. 2001, Field et al. 2004). IPMS1 (At1g18500) and IPMS2 (At1g74040) have been shown to be involved in leucine biosynthesis (de Kraker et al. 2007). AtBCAT1 (At1g10060) has been shown to initiate degradation of the branched-chain amino acids leucine, isoleucine and valine (Schuster and Binder 2005). AtBCAT4 has been reported to be involved in methionine chain elongation (Schuster et al. 2006). Recently, AtBCAT3 was reported to be involved in both methionine chain elongation and amino acid biosynthesis (Knill et al. 2008). Concerning AtBCAT2, its induction by dehydration stress is diminished in the knockout mutant of NCED3 that plays a role in the dehydration-inducible biosynthesis of ABA (Urano et al. 2009). In this mutant, dehydration-inducible accumulation of branched-chain amino acids was repressed, suggesting the involvement of AtBCAT2 (Urano et al. 2009). In contrast to MAM/IPMS and MAAT/BCAT, there are no reports so far on the characterization of MAM-I/IPM-I or MAM-D/IPM-D.

Fig. 1.

Methionine chain elongation and leucine biosynthesis. The upper panel shows the methionine chain elongation pathway. Compound names except for methionine derivatives indicate the names when n equals 2. KMTB, 2-keto-4-methylthiobutyrate. The middle panel shows the Arabidopsis homologs of bacterial leucine biosynthetic genes. The genes shown in red letters are involved or predicted to be involved in methionine chain elongation. The lower panel shows the leucine biosynthetic pathway. KIV, 2-ketoisovalerate; KIC, 2-ketoisocaproate.

In our previous study of co-expression analyses using the public transcriptome data sets of ATTED-II (Obayashi et al. 2007) and an in-house data set obtained under sulfur-deficient conditions (Hirai et al. 2005), we found that AtLeuC1 (At4g13430), AtLeuD1 (At2g43100), AtLeuD2 (At3g58990) and AtIMD1 (At5g14200) were co-expressed with known Met-GSL biosynthetic genes (Hirai et al. 2007). These genes were shown to be regulated coordinately with the known Met-GSL biosynthetic genes by a main positive regulator PMG1/HAG1/Myb28 (Gigolashvili et al. 2007, Hirai et al. 2007, Sønderby et al. 2007, Beekwilder et al. 2008, Malitsky et al. 2008), suggesting that these genes are committed to Met-GSL biosynthesis (Hirai et al. 2007).

In this study, we report the supporting evidence for the predicted function of AtLeuC1 and AtIMD1 as genes encoding MAM-IL and MAM-D, respectively. In addition, we discuss differences in the effect of knocking out these genes on methionine-related and other metabolism to determine the role of these genes in primary and secondary metabolism.

Results

Met-GSL levels in the knockout lines of candidate genes

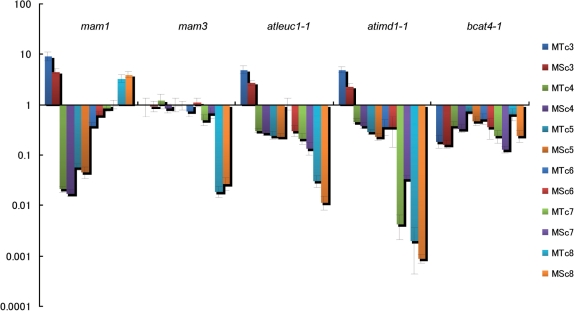

In a previous study (Hirai et al. 2007), we assumed that AtLeuC1, AtLeuD1/D2 and AtIMD1 encode MAM-IL, MAM-IS and MAM-D, respectively (Fig. 1, Table 1). To confirm the predicted functions, we analyzed GSL levels in the leaves of the knockout lines of these genes, and those in the knockout lines of MAM1, MAM3 and AtBCAT4 as controls. In leaves of Arabidopsis accession Columbia, methylthioalkyl and methylsulfinylalkyl GSLs with C4–C8 chains are the major forms of Met-GSLs (Petersen et al. 2002, Reichelt et al. 2002, Brown et al. 2003). The results obtained from mam1, mam3 and bcat4-1 were consistent with previous reports (Schuster et al. 2006, Textor et al. 2007, Knoke et al. 2009). That is, in mam1, the levels of C4–C6 GSLs were low, whereas the levels of C3 and C8 GSLs were greater than in the wild type (Fig. 2). In mam3, the levels of C8 GSLs were greatly reduced (Fig. 2). In bcat4-1, Met-GSLs of all chain classes (C3–C8) diminished (Fig. 2). On the other hand, in atleuc1-1 and atimd1-1, which showed stronger phenotypes than atleuc1-2 and atimd1-2, respectively (Supplementary Fig. S1), the levels of Met-GSLs with long chains (C7–C8) were significantly lower in the knockout lines (Fig. 2). Levels of Met-GSLs with C4–C6 chains were also low, although the decrease was less than for the long-chain GSLs (Fig. 2). In contrast, the levels of C3 GSLs were elevated in both atleuc1-1 and atimd1-1 (Fig. 2). No remarkable changes in the tryptophan-derived GSL content were observed in either line (data not shown). In the weaker knockout lines, atleuc1-2 and atimd1-2, similar trends were observed, with the exception of the C3 GSL levels in atimd1-2 (Supplementary Fig. S1).

Table 1.

Candidate and characterized genes encoding methylthioalkylmalate isomerase and methylthioalkylmalate dehydrogenase

| Enzyme | Gene name (previously) | Nomenclature (this study) | AGI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAM-IL | Methylthioalkylmalate isomerase, large subunit | AtLeuC1 | MAM-IL1 | At4g13430 |

| MAM-IS | Methylthioalkylmalate isomerase, small subunit | AtLeuD1 | At2g43100 | |

| MAM-IS | Methylthioalkylmalate isomerase, small subunit | AtLeuD2 | At3g58990 | |

| MAM-D | Methylthioalkylmalate dehydrogenase | AtIMD1 | MAM-D1 | At5g14200 |

Fig. 2.

Glucosinolate contents in the leaves of the knockout lines. The content of GSLs relative to the wild type (Col-0) are shown on a logarithmic scale. MT and MS indicate methylthioalkyl and methylsulfinylalkyl GSLs, respectively. cn (n = 3–8) indicates the length of side chains. The analysis was conducted on 5–12 replicates.

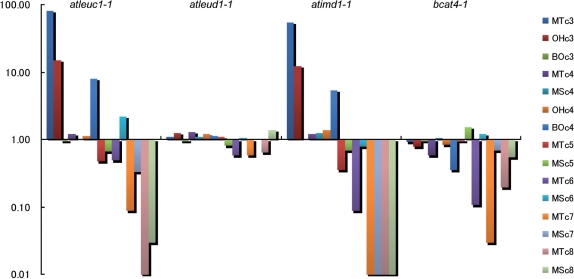

We also analyzed the GSL levels in seeds of these knockout lines (Fig. 3). In contrast to the GSL profiles in leaves, hydroxylalkyl and benzoyloxyalkyl GSLs in addition to methylthioalkyl and methylsulfinylalkyl GSLs accumulated in the seeds of Arabidopsis accession Columbia (Petersen et al. 2002, Reichelt et al. 2002, Brown et al. 2003). Changes in GSL profiles in the seeds of atleuc1-1 and atimd1-1 were almost the same as those observed in the leaves, with the exception of C4 GSLs. In the seeds of atleuc1-1, 4-benzoyloxybutyl GSL was elevated by 8-fold (Fig. 3). No remarkable change in tryptophan-derived GSL content was observed in either line (data not shown). In bcat4-1, the levels of almost all Met-GSLs were low, a result consistent with a previous report (Schuster et al. 2006).

Fig. 3.

Glucosinolate contents in the seeds of the knockout lines. The content of GSLs relative to the wild type are shown on a logarithmic scale. MT, MS, OH and BO indicate methylthioalkyl, methylsulfinylalkyl, hydroxylalkyl and benzoyloxyalkyl GSLs, respectively. cn (n = 3–8) indicates the length of the side chain.

Based on co-expression analysis, we assumed that both AtLeuD1 and AtLeuD2 encode MAM-IS. We analyzed the GSL levels in the seeds of a knockout line of AtLeuD1 (atleud1-1). This line did not show remarkable changes in Met-GSL content for any chain class (Fig. 3).

Changes in metabolic profiles in knockout lines

For a further understanding of the biological roles of methionine chain elongation genes in terms of controlling GSL and related metabolism at the branch points of primary and secondary metabolism, we analyzed the metabolic profiles of the knockout lines of these genes. By means of widely targeted metabolomics that we have recently established (Sawada et al. 2009), we detected approximately 200 metabolites including GSLs and amino acids in the leaves of the knockout lines atleuc1-1, atimd1-1, mam1 and mam3. Because we used the leaves at different growth stages (see Materials and Methods), we analyzed atleuc1-1 and atimd1-1, and mam1 and mam3 separately.

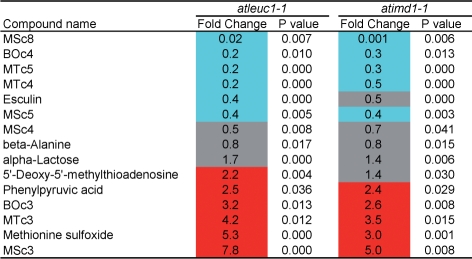

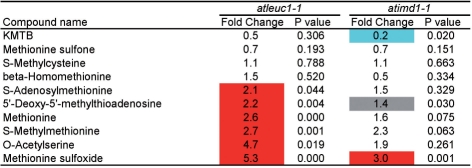

First, we analyzed the data by focusing on metabolites whose accumulation levels significantly (P < 0.05) changed in both atleuc1-1 and atimd1-1 compared with wild-type Columbia at the same growth stage (Fig. 4). Among 15 metabolites, nine were Met-GSLs (MTcn, MScn and BOcn). Because of the higher sensitivity of the ultraperformance liquid chromatography (UPLC)-tandem quadrupole detector (TQD)-mass spectrometry (MS) (Waters) used in widely targeted metabolomics compared with UPLC-ZQ-MS (Waters) used for Fig. 2, BOcn GSLs were detectable in the wild-type Columbia leaves. In both lines, the levels of Met-GSLs with C4–C8 chains were reduced, whereas those with C3 chains were elevated. This result was consistent with that shown in Fig. 2. It is noteworthy that the levels of two methionine-related metabolites were elevated in both lines. One of them, 5′-deoxy-5′-methylthioadenosine (S-methyl-5′-thioadenosine), is synthesized as a by-product in the biosynthesis of spermine and spermidine from decarboxylated S-adenosylmethionine, and in the biosynthesis of nico-tianamine and ethylene from S-adenosylmethionine [Plant Metabolic Network (PMN), http://www.plantcyc.org/, April 5, 2009] (Zhang et al. 2005).

Fig. 4.

Metabolite levels that were significantly changed in the leaves of both atleuc1-1 and atimd1-1. Metabolite levels were analyzed in six replicates, and those that changed significantly in the knockout lines were identified by Welch’s t-test (P < 0.05). Fold change of the average metabolite content in the knockout line with respect to that in wild type is shown as follows: red, fold change >2; blue, fold change <0.5; gray, 0.5 ≤ fold change ≤2.

Fig. 5 shows a list of the methionine-related metabolites among the detected metabolites and whether their accumulation levels changed significantly or not. By our widely targeted analysis, 10 methionine-related metabolites were detected in the 3-week-old leaves of Arabidopsis Columbia. Interestingly, the levels of five metabolites (S-adenosylmethionine, 5′-deoxy-5′-methylthioadenosine, methionine, S-methylmethionine and methionine sulfoxide) were significantly elevated (P < 0.05) in atleuc1-1. A similar trend was observed in atimd1-1, although the changes were not always statistically significant. This result suggests that the metabolic flow from methionine to Met-GSLs was blocked and redirected to other methionine metabolism (see Supplementary Fig. S2) in the knockout lines. It is noteworthy that the level of KMTB, the precursor of Met-GSLs, was significantly reduced in atimd1-1. When further conversion of KMTB is blocked, it might be converted back to methionine by the reverse activity (amination activity) of AtBCAT4. O-Acetylserine is known to increase under sulfur starvation (for reviews, see Saito 2004, Hawkesford and De Kok 2006). The increase of O-acetylserine may indicate some change in sulfur status in the cell.

Fig. 5.

Changes in methionine-related metabolite levels in the leaves of atleuc1-1 and atimd1-1. Metabolite levels were analyzed in six replicates. Fold change of the average metabolite content in the knockout line with respect to that in wild type is shown. P-values of Welch’s t-test are also shown. When P < 0.05, the fold change column is colored as follows: red, fold change >2; blue, fold change <0.5; gray, 0.5 ≤ fold change ≤2.

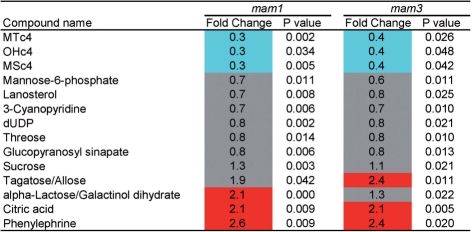

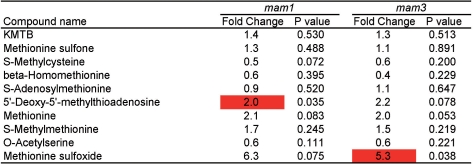

The metabolites whose levels were significantly changed in both mam1 and mam3 are shown in Fig. 6. At 4 weeks after germination, the levels of C4 Met-GSLs were reduced in both mam1 and mam3. Decreases in the levels of C5 Met-GSLs (fold change = 0.4, P-value = 0.009 for MTc5; fold change = 0.5, P-value = 0.026 for MSc5) and an increase in MTc8 (fold change = 2.5, P-value = 0.048) were observed only in mam1. Interestingly, the accumulation of several sugars was changed in both knockout lines (Fig. 6). Fig. 7 shows the methionine-related metabolites in mam1 and mam3, most of which were not significantly altered. Based on the results shown in Figs. 6 and 7, sugar metabolism, rather than methionine metabolism, was affected by the loss of MAM activity at 4 weeks after germination.

Fig. 6.

Metabolite levels that were significantly changed in the leaves of both mam1 and mam3. Metabolite levels were analyzed in six replicates, and those that changed significantly in the knockout lines were identified by Welch’s t-test (P < 0.05). Fold change of the average metabolite content in the knockout line with respect to that in the wild type is shown as follows: red, fold change >2; blue, fold change <0.5; gray, 0.5 ≤ fold change ≤2.

Fig. 7.

Changes in methionine-related metabolite levels in the leaves of mam1 and mam3. Metabolite contents were analyzed in six replicates. Fold change of the average metabolite content in the knockout line with respect to that in the wild type is shown. P-values of Welch’s t-test are also shown. When P < 0.05, the fold change column is colored as follows: red, fold change >2; blue, fold change <0.5; gray, 0.5 ≤ fold change ≤ 2.

We also investigated the effect of knocking out methionine chain elongation genes on amino acid contents. A statistically significant change of more than double or less than half was observed only for the methionine content in atleuc1-1 (Fig. 5 and Supplementary Fig. S3).

Discussion

AtLeuC1 and AtIMD1 are involved in Met-GSL biosynthesis

In our previous studies, we systematically identified a set of the candidate genes involved in methionine chain elongation based on co-expression analysis. In this study we found that knocking out either of the candidate genes, AtleuC1 or AtIMD1, reduced the level of Met-GSLs, indicating that both genes are actually involved in Met-GSL biosynthesis. Here, we named AtleuC1 and AtIMD1 as MAM-IL1 and MAM-D1, respectively (Table 1). Based on co-expression analysis, it is possible that MAM-IL and MAM-D are encoded by single genes, AtLeuC1 and AtIMD1, respectively (Fig. 1); however, the knockout of these genes did not lead to the complete loss of Met-GSLs (Fig. 2). The homologs of these genes, presumably AtLeuC2/C3 and AtIMD2/3, may be responsible for the residual activity of MAM-IL and MAM-D, respectively. A similar situation was found in the bcat3-1/bcat4-2 double knockout mutant. AtBCAT4 is responsible for the deamination of methionine, the initial step of methionine chain elongation (Schuster et al. 2006) (Supplementary Fig. S2). AtBCAT3 is reported to catalyze both reactions, the terminal amination steps in methionine chain elongation leading to short-chain (C3 and C4) GSLs and the amination steps in branched-chain amino acid biosynthesis (Knill et al. 2008) (Supplementary Fig. S2). In the bcat3-1/bcat4-2 double knockout mutant, the Met-GSLs were still synthesized, suggesting the involvement of other enzymes (e.g. AtBCAT2 or AtBCAT5) (Knill et al. 2008).

The partial reduction in Met-GSL content in atleuc1, atimd1 and bcat3-1/bcat4-2 is in contrast to the complete absence of Met-GSLs in the cyp79f1/cyp79f2 double knockout mutant (Tantikanjana et al. 2004). In the core Met-GSL biosynthetic pathway following methionine chain elongation, CYP79F1 catalyzes the conversion of chain-elongated methionine derivatives with C3–C8 chains to their aldoximes, whereas CYP79F2 catalyzes the conversion of methionine derivatives with C7 and C8 chains (Chen et al. 2003) (Supplementary Fig. S2). Thus CYP79F1 and CYP79F2 have overlapping substrate specificity, and no other enzyme possesses the compensatory activity, leading to the complete absence of Met-GSLs in cyp79f1/cyp79f2. Presumably methionine chain elongation enzymes have been recruited from the leucine biosynthetic pathway in the course of evolution (e.g. Schuster et al. 2006). Methionine chain elongation enzymes seem to have relatively vague substrate specificity compared with the enzymes in the core GSL biosynthetic pathway. As mentioned, the recombinant AtBCAT3 protein possessed amination activity with the keto acids of branched-chain amino acids and with those of methionine derivatives (Knill et al. 2008); thus, AtBCAT3 is involved in both primary and secondary metabolism. The recombinant AtBCAT4 protein showed weak activity with leucine and its keto acid (primary metabolism), although the preferable substrate is methionine and its keto acid (secondary metabolism) (Schuster et al. 2006). Conversely, IPMS1 and IPMS2, which are responsible for leucine biosynthesis, could catalyze a condensation reaction with the MAM substrate KMTB in vitro (de Kraker et al. 2007). Moreover, the IPMS from Escherichia coli, a non-GSL-producing organism, is also active with KMTB (de Kraker et al. 2007). Taking these reports into account, AtLeuC2/AtLeuC3 and AtIMD2/AtIMD3 may have dual activity involved in leucine biosynthesis and methionine chain elongation.

By co-expression analysis, we also predicted that AtLeuD1 and AtleuD2 encode MAM-IS. Unfortunately, a knockout line of AtLeuD2 was not available as a public bioresourse; therefore, we analyzed only a knockout line of AtLeuD1. However, no remarkable changes were observed in the Met-GSL levels in the seeds of this line (Fig. 3), probably because of the functional redundancy with AtLeuD2.

Substrate specificity and functional redundancy of the enzymes involved in methionine chain elongation

We compared the Met-GSL accumulation profiles in the leaves of the knockout lines of the genes involved in methionine chain elongation. In the knockout lines of MAM1, the levels of C3 and C8 GSLs were elevated, whereas C4–C7 GSLs were reduced (Kroymann et al. 2001, Textor et al. 2007) (Fig. 2). In the MAM3 knockout lines, the most obvious phenotype was a decrease in the levels of C8 GSLs (Textor et al. 2007) (Fig. 2). For a AtBCAT4 knockout, the levels of all Met-GSLs (C3–C8 chains) were reduced (Schuster et al. 2006) (Fig. 2). In a AtBCAT3 knockout, remarkable increases in the levels of methylsulfinylalkyl GSLs with C5–C7 chains were observed and also in the levels of leucine-derived 4-methylpentyl GSL and valine-derived 5-methylhexyl GSL, which are usually barely detectable in accession Columbia (Knill et al. 2008). Interestingly, a MAM-IL1 knockout (atleuc1-1) and a MAM-D1 knockout (atimd1-1) showed a novel phenotype in accumulation of Met-GSLs. In these knockout lines, the levels of C4–C8 GSLs declined whereas the level of only C3 GSLs was elevated (Fig. 2).

There have been many reports that MAM genes are responsible for the diversification of Met-GSL chain length in Arabidopsis and related plants (for a review, see Benderoth et al. 2009). In Arabidopsis accession Columbia, MAM1 catalyzes the condensing reactions of the first two elongation cycles but not those of further cycles (Kroymann et al. 2001, Textor et al. 2004, Benderoth et al. 2006, Benderoth et al. 2009). MAM3 is responsible for all GSL chain lengths (C3–C8) (Textor et al. 2007, Benderoth et al. 2009, Knoke et al. 2009). In the case of MAM1 knockout lines, the increase in C3 and C8 GSL content could be explained by a compensatory overexpression of MAM3. This explanation was strongly supported by the mathematical model based on knowledge of the structure of the pathway, the kinetic properties of its enzymes and MAM transcript levels (Knoke et al. 2009). Increases in the levels of C3 GSLs in a MAM-IL1 knockout (atleuc1-1) and a MAM-D1 knockout (atimd1-1) might be explained by a similar model if the compensatory activity of another enzyme with a different substrate specificity was assumed.

Changes in metabolic profiles of the knockout mutants

We analyzed the effect of knocking out methionine chain elongation genes on the metabolic profiles in leaves by means of widely targeted metabolomics (Sawada et al. 2009). Under our experimental conditions, amino acid contents in leaves were little affected, although the methionine content tended to be enhanced by knocking out the genes (Supplementary Fig. S3). This result might be due to the blocking of Met-GSL biosynthesis and redirection to primary methionine metabolism. Among the methionine-derived metabolites detected in our analysis, methionine sulfoxide also increased in almost all of the knockout lines (Figs. 4, 5, 7). In a MAM-IL1 knockout (atleuc1-1), other methionine-derived metabolites (S-adenosylmethionine, 5′-deoxy-5′-methylthioadenosine and S-methylmethionine) also significantly increased based on our criteria (Fig. 5). However, the effects were exerted not only on methionine metabolism but also indirectly on other metabolic pathways. In mam1 and mam3, sugar metabolism, rather than methionine-related metabolism, was affected (Fig. 6). Further analyses will be needed to understand all the effects on plant metabolism and to know for sure whether the difference in metabolic phenotypes in these knockout lines was simply due to the function of the knocked-out genes or also affected by the developmental stage of the plants examined (4 weeks old for atleuc1-1 and atimd1-1, and 3 weeks old for mam1 and mam3).

A tentative model of Met-GSL biosynthesis and its regulation by PMG1/HAG1/Myb28

The genes involved in Met-GSL biosynthesis are coordinately regulated by PMG1/HAG1/Myb28 at the level of transcription (Gigolashvili et al. 2007, Hirai et al. 2007, Sønderby et al. 2007, Beekwilder et al. 2008, Malitsky et al. 2008). In the methionine chain elongation pathway, MAM1, MAM3, AtBCAT3, AtBCAT4, MAM-IL1/AtLeuC1 and MAM-D1/AtIMD1 were regulated by PMG1/HAG1/Myb28; however, the knockout of MAM-IL1/AtLeuC1 and of MAM-D1/AtIMD1, and the double knockout of AtBCAT3 and AtBCAT4 did not completely abolish the accumulation of Met-GSLs. As mentioned above, one possibility is that other genes, which are primarily involved in other metabolic pathways and, hence, are not regulated by PMG1/HAG1/Myb28, might compensate the lost function of knocked-out genes. It has not been determined whether enzyme(s) other than MAM1 and MAM3 may have MAM activity or not, because mam1/mam3 double knockout mutants have not been obtained so far either from crosses between lines carrying the single mutations—MAM1 and MAM3 are adjacent to each other in Arabidopsis accession Columbia—or from attempts to co-suppress both genes (Textor et al. 2007). A tentative model for Met-GSL biosynthesis and its regulation by PMG1/HAG1/Myb28 is shown in Supplementary Fig. S2.

Gene functional elucidation in the era of omics

In Arabidopsis, thousands of transcriptome data profiles obtained under various conditions are publicly available, and co-expression analysis based on these data sets can systematically identify the candidate genes that might be involved in a given biological function. Because co-expression analysis can identify a set of candidates simultaneously, confirmation of the predicted function of each candidate gene by biological experiments is time consuming and a bottleneck for gene functional elucidation. Since gene knockout lines of Arabidopsis are easily available as various bioresources from several institutions, it is reasonable to propose that characterization of knockout lines of candidate genes might be the first choice to confirm predicted function systematically and in a high-throughput manner. In this study, we confirmed the function of candidate genes by characterizing the corresponding knockout lines. By focusing on the specific traits of interest, in this case GSL accumulation, we could confirm the in vivo function of the candidates. Furthermore, by an omics approach (in this case, widely targeted metabolite analysis), we could also suggest the in vivo role of the genes of interest in controlling primary and secondary metabolism. By applying novel methodologies of fluxomics that enable us to monitor metabolic flux (e.g. Sekiyama and Kikuchi 2007), further information on the control of metabolism will be obtained. In addition, a high-throughput in vitro enzyme assay system is required for further confirmation of predicted gene function.

Materials and Methods

Plant materials and plant growth conditions

As knockout mutants of AtLeuC1 and AtIMD1, two allelic lines of the respective genes [SALK_029510 (atleuc1-1) and SALK_065789 (atleuc1-2) for AtLeuC1, and SALK_063423 (atimd1-1) and SALK_ 069991 (atimd1-2) for AtIMD1] were used (Supplementary Fig. S1A). In atleuc1-1, atimd1-1 and atimd1-2, expression of the corresponding gene was almost completely repressed (Supplementary Fig. S1B). In atleuc1-2, transcript levels for AtLeuC1 were reduced but not completely repressed (Supplementary Fig. S1B). Knockout lines of AtBCAT4 (SALK_013627, bcat4-1) have already been reported (Schuster et al. 2006). As MAM1, MAM3 and AtLeuD1 knockout lines, SALK_012677 (mam1), SALK_004536 (mam3) and SALK_048320 (atleud1-1) were used. Homozygous lines of the T-DNA insertion mutants were selected by genomic PCR according to the T-DNA Express: Arabidopsis iSect Tool manual (http://signal.salk.edu/). Wild-type Arabidopsis thaliana (accession Colombia) and mutants (T-DNA insertion lines) were grown in a pre-fabricated room-type chamber at 22°C and a 16 h photoperiod in soil (PRO-MIX BX, Premier Horticulture, Rivière-du-Loup, QC, Canada) for seed collection, or on agar-solidified 1/2 Murashige–Skoog medium containing 1% sucrose for GSL analysis and widely targeted metabolomics.

Reverse transcription–PCR (RT–PCR) analysis

Total RNA isolation was performed using an RNeasy Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen, Chatsworth, CA, USA). RT–PCR was performed using total RNA as a template with cDNA synthesis using SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis System (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The primer sequences were as follows: 5′-CCATGGGCTGACACAAATACT-3′ and 3′-CCAAATAATATGAGCCTTGATAAAC-5′ for UBC9 (At4g27960); 5′-CTTGGTGGCCCAGCAGACACCTACG-3′ and 3′-CACACGAAGCCATTACATTAGC-5′ for AtLeuC1 (At4g13430); and 5′-GTATGGACTTGGAGAAGAAAAGGC-3′ and 3′-GTGACCGTAAAACCAAGTGCTACAC-5′ for AtIMD1 (At5g14200).

GSL analysis using UPLC-ZQ-MS

A 50–100 mg aliquot of the rosette leaves (3 weeks after germination) and approximately 2 mg of the mature seeds [collected by using the seed spoon 200 (Bio Medical Science, Tokyo, Japan)] of wild-type and mutant lines were used for GSL analysis. The 2 ml sample tubes containing 5 mm zirconia beads were pre-frozen with liquid nitrogen. The leaves or seeds were collected in the tubes, immediately frozen with liquid nitrogen and stored at –80°C until use.

The frozen samples were homogenized using a mixer mill MM 200 (Retsch, Haan, Germany) at 20 Hz for 5 min. After homogenization, 10 µl of extraction buffer (MeOH : H2O = 4 : 1, 0.1% formic acid, 20 µM sinigrin as an internal standard) per mg of tissue (fresh weight) was added for extraction of metabolites. After centrifugation (10,000×g at 4°C), 100 µl of the supernatant was transferred to a new tube and concentrated to dryness using a Speedvac (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) vacuum centrifuge. The residue was dissolved in 50 µl of H2O and filtered using Pall Nanosep Centrifuge Filters (0.45 µm, GHP) (Pall Life Sciences, Ann Arbor, MI, USA). The filtered solution was analyzed using a UPLC-ZQ-MS (Waters, Milford, MA, USA). The GSLs were separated and detected under the following conditions: ACQUITY UPLC HSS T3 column (2.1 mm × 50 mm, Waters) at 30°C, flow rate 0.38 ml min–1, solvent A (0.1% formic acid in H2O), solvent B (0.1% formic acid in MeCN), gradient pattern (0–0.1 min, 100% solvent A; 2 min, 8% solvent B; 3 min, 20% solvent B; 5.5 min, 100% solvent B; 6.5 min, 100% solvent B), electrospray ionization-MS negative ion mode, capillary voltage 3.0 kV, cone voltage 40 V, source temperature at 150°C, desolvation gas 600 l h–1 at 300°C. The GSL contents were calculated using sinigrin as a standard.

Widely targeted metabolomics

Approximately 50–100 mg of leaves (3 weeks after germination for mam1 and mam3, and 4 weeks after germination for atleuc1 and atimd1) of wild-type and mutant Arabidopsis lines were used for widely targeted metabolomics using UPLC-TQD (Waters) as previously described (Sawada et al. 2009). Analytical conditions for UPLC-TQD are released in our data repository and distribution site DROP Met at our website PRIMe (http://prime.psc.riken.jp/). Metabolites were annotated based on the retention time and multiple reaction monitoring conditions of authentic compounds. The metabolites whose accumulation levels significantly changed were identified by Welch’s t-test using the Microsoft Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA) function (TTEST, Tails = 2, Type = 3).

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at PCP online.

Funding

The Japan Science and Technology Agency, CREST (Project name ‘Elucidation of Amino Acid Metabolism in Plants Based on Integrated Omics Analyses’).

Acknowledgments

We thank Mitsutaka Araki (RIKEN Plant Science Center) for his contribution to DNA sequencing.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- BCAT

branched-chain amino acid amino-transferase

- GSL

glucosinolate

- IPM-D

isopropylmalate dehydrogenase

- IPM-IL

the large subunit of isopropylmalate isomerase

- IPM-IS

the small subunit of isopropylmalate iso-merase

- IPMS

isopropylmalate synthase

- MAAT

methionine analog aminotransferase

- MAM

methylthioalkylmalate synthase

- MAM-D

methylthioalkylmalate dehydrogenase

- MAM-IL

the large subunit of methylthioalkylmalate isomerase

- MAM-IS

the small subunit of methylthioal-kylmalate isomerase

- Met-GSL

methionine-derived glucosinolate

- MS

mass spectrometry

- RT–PCR

reverse transcription–PCR

- UPLC

ultraperformance liquid chroma-tography.

References

- Aoki K, Ogata Y, Shibata D. Approaches for extracting practical information from gene co-expression networks in plant biology. Plant Cell Physiol. 2007;48:381–390. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcm013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beekwilder J, van Leeuwen W, van Dam NM, Bertossi M, Grandi V, Mizzi L, et al. The impact of the absence of aliphatic glucosino-lates on insect herbivory in Arabidopsis. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e2068. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benderoth M, Pfalz M, Kroymann J. Methylthioalkylmalate synthases: genetics, ecology and evolution. Phytochem. Rev. 2009;8:255–268. [Google Scholar]

- Benderoth M, Textor S, Windsor AJ, Mitchell-Olds T, Gershenzon J, Kroymann J. Positive selection driving diversification in plant secondary metabolism. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:9118–9123. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601738103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown PD, Tokuhisa JG, Reichelt M, Gershenzon J. Variation of glucosinolate accumulation among different organs and developmental stages of Arabidopsis thaliana. Phytochemistry. 2003;62:471–481. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(02)00549-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S, Glawischnig E, Jorgensen K, Naur P, Jorgensen B, Olsen CE, et al. CYP79F1 and CYP79F2 have distinct functions in the biosynthesis of aliphatic glucosinolates in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2003;33:923–937. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2003.01679.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craigon DJ, James N, Okyere J, Higgins J, Jotham J, May S. NASCArrays: a repository for microarray data generated by NASC’s transcriptomics service. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:D575–577. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Auria JC, Gershenzon J. The secondary metabolism of Arabidopsis thaliana: growing like a weed. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2005;8:308–316. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2005.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Kraker JW, Luck K, Textor S, Tokuhisa JG, Gershenzon J. Two Arabidopsis genes (IPMS1 and IPMS2) encode isopropylmalate synthase, the branchpoint step in the biosynthesis of leucine. Plant Physiol. 2007;143:970–986. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.085555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahey JW, Zalcmann AT, Talalay P. The chemical diversity and distribution of glucosinolates and isothiocyanates among plants. Phytochemistry. 2001;56:5–51. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(00)00316-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field B, Cardon G, Traka M, Botterman J, Vancanneyt G, Mithen R. Glucosinolate and amino acid biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2004;135:828–839. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.039347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gantet P, Memelink J. Transcription factors: tools to engineer the production of pharmacologically active plant metabolites. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2002;23:563–569. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(02)02098-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gigolashvili T, Yatusevich R, Berger B, Muller C, Flugge U.-I. The R2R3-MYB transcription factor HAG1/MYB28 is a regulator of methionine-derived glucosinolate biosynthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 2007;51:247–261. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goda H, Sasaki E, Akiyama K, Maruyama-Nakashita A, Nakabayashi K, Li W, et al. The AtGenExpress hormone and chemical treatment data set: experimental design, data evaluation, model data analysis and data access. Plant J. 2008;55:526–542. doi: 10.1111/j.0960-7412.2008.03510.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grubb CD, Abel S. Glucosinolate metabolism and its control. Trends Plant Sci. 2006;11:89–100. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2005.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halkier BA, Gershenzon J. Biology and biochemistry of glucosinolates. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2006;57:303–333. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.57.032905.105228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkesford MJ, De Kok LJ. Managing sulphur metabolism in plants. Plant Cell Environ. 2006;29:382–395. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2005.01470.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirai MY. A robust omics-based approach for the identification of glucosinolate biosynthetic genes. Phytochem. Rev. 2009;8:15–23. [Google Scholar]

- Hirai MY, Klein M, Fujikawa Y, Yano M, Goodenowe DB, Yamazaki Y, et al. Elucidation of gene-to-gene and metabolite-to-gene networks in arabidopsis by integration of metabolomics and transcriptomics. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:25590–25595. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502332200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirai MY, Saito K. Analysis of systemic sulphur metabolism in plants by using integrated ‘-omics’ strategies. Mol. Biosyst. 2008;4:967–973. doi: 10.1039/b802911n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirai MY, Sugiyama K, Sawada Y, Tohge T, Obayashi T, Suzuki A, et al. Omics-based identification of Arabidopsis Myb transcription factors regulating aliphatic glucosinolate biosynthesis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:6478–6483. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611629104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilian J, Whitehead D, Horak J, Wanke D, Weinl S, Batistic O, et al. The AtGenExpress global stress expression data set: protocols, evaluation and model data analysis of UV-B light, drought and cold stress responses. Plant J. 2007;50:347–363. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03052.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knill T, Schuster J, Reichelt M, Gershenzon J, Binder S. Arabidopsis branched-chain aminotransferase 3 functions in both amino acid and glucosinolate biosynthesis. Plant Physiol. 2008;146:1028–1039. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.111609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knoke B, Textor S, Gershenzon J, Schuster S. Mathematical modelling of aliphatic glucosinolate chain length distribution in Arabidopsis thaliana leaves. Phytochem. Rev. 2009;8:39–51. [Google Scholar]

- Kroymann J, Textor S, Tokuhisa JG, Falk KL, Bartram S, Gershenzon J, et al. A gene controlling variation in Arabidopsis glucosino-late composition is part of the methionine chain elongation pathway. Plant Physiol. 2001;127:1077–1088. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malitsky S, Blum E, Less H, Venger I, Elbaz M, Morin S, et al. The transcript and metabolite networks affected by the two clades of Arabidopsis glucosinolate biosynthesis regulators. Plant Physiol. 2008;148:2021–2049. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.124784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nozawa A, Takano J, Miwa K, Nakagawa Y, Fujiwara T. Cloning of cDNAs encoding isopropylmalate dehydrogenase from Arabidopsis thaliana and accumulation patterns of their transcripts. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2005;69:806–810. doi: 10.1271/bbb.69.806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obayashi T, Kinoshita K, Nakai K, Shibaoka M, Hayashi S, Saeki M, et al. ATTED-II: a database of co-expressed genes and cis elements for identifying co-regulated gene groups in Arabidopsis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:D863–D869. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen BL, Chen S, Hansen CH, Olsen CE, Halkier BA. Composition and content of glucosinolates in developing Arabidopsis thaliana. Planta. 2002;214:562–571. doi: 10.1007/s004250100659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichelt M, Brown PD, Schneider B, Oldham NJ, Stauber E, Tokuhisa J, et al. Benzoic acid glucosinolate esters and other glucosinolates from Arabidopsis thaliana. Phytochemistry. 2002;59:663–671. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(02)00014-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito K. Sulfur assimilatory metabolism. The long and smelling road. Plant Physiol. 2004;136:2443–2450. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.046755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito K, Hirai MY, Yonekura-Sakakibara K. Decoding genes with coexpression networks and metabolomics—‘majority report by precogs’. Trends Plant Sci. 2008;13:36–43. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2007.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawada Y, Akiyama K, Sakata A, Kuwahara A, Otsuki H, Sakurai T, et al. Widely targeted metabolomics based on large-scale MS/MS data for elucidating metabolite accumulation patterns in plants. Plant Cell Physiol. 2009;50:37–47. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcn183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid M, Davison TS, Henz SR, Pape UJ, Demar M, Vingron M, et al. A gene expression map of Arabidopsis thaliana development. Nat. Genet. 2005;37:501–506. doi: 10.1038/ng1543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuster J, Binder S. The mitochondrial branched-chain aminotransferase (AtBCAT-1) is capable to initiate degradation of leucine, isoleucine and valine in almost all tissues in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Mol. Biol. 2005;57:241–254. doi: 10.1007/s11103-004-7533-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuster J, Knill T, Reichelt M, Gershenzon J, Binder S. BRANCHED-CHAIN AMINOTRANSFERASE4 is part of the chain elongation pathway in the biosynthesis of methionine-derived glucosinolates in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2006;18:2664–2679. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.039339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekiyama Y, Kikuchi J. Towards dynamic metabolic network measurements by multi-dimensional NMR-based fluxomics. Phytochemistry. 2007;68:2320–2329. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2007.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sønderby IE, Hansen BG, Bjarnholt N, Ticconi C, Halkier BA, Kliebenstein DJ. A systems biology approach identifies a R2R3 MYB gene subfamily with distinct and overlapping functions in regulation of aliphatic glucosinolates. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e1322. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tantikanjana T, Mikkelsen MD, Hussain M, Halkier BA, Sundaresan V. Functional analysis of the tandem-duplicated P450 genes SPS/BUS/CYP79F1 and CYP79F2 in glucosinolate biosynthesis and plant development by Ds transposition-generated double mutants. Plant Physiol. 2004;135:840–848. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.040113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Textor S, Bartram S, Kroymann J, Falk KL, Hick A, Pickett JA, et al. Biosynthesis of methionine-derived glucosinolates in Arabidopsis thaliana: recombinant expression and characterization of methylthioalkylmalate synthase, the condensing enzyme of the chain-elongation cycle. Planta. 2004;218:1026–1035. doi: 10.1007/s00425-003-1184-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Textor S, de Kraker J.-W, Hause B, Gershenzon J, Tokuhisa JG. MAM3 catalyzes the formation of all aliphatic glucosinolate chain lengths in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2007;144:60–71. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.091579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urano K, Maruyama K, Ogata Y, Morishita Y, Takeda M, Sakurai N, et al. Characterization of the ABA-regulated global responses to dehydration in Arabidopsis by metabolomics. Plant J. 2009;57:1065–1078. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03748.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittstock U, Halkier BA. Glucosinolate research in the Arabidopsis era. Trends Plant Sci. 2002;7:263–270. doi: 10.1016/s1360-1385(02)02273-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan X, Chen S. Regulation of plant glucosinolate metabolism. Planta. 2007;226:1343–1352. doi: 10.1007/s00425-007-0627-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang P, Foerster H, Tissier CP, Mueller L, Paley S, Karp PD, et al. MetaCyc and AraCyc. Metabolic pathway databases for plant research. Plant Physiol. 2005;138:27–37. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.060376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.