Abstract

Activation of mast cells in the allergic inflammatory response occurs via the high affinity receptor for IgE (FcεRI) following receptor aggregation induced by antigen-mediated cross-linking of IgE-occupied FcεRI. Recent observations suggest this response is profoundly influenced by other factors that reduce the threshold for, and increase the extent of, mast cell activation. For example, under experimental conditions, cell surface receptors such as KIT and specific G protein-coupled receptors synergistically enhance FcεRI-mediated mast cell degranulation and cytokine production. Activating mutations in critical signaling molecules may also contribute to such responses. In this review, we describe our research exploring the mechanisms regulating these synergistic interactions and, furthermore, discuss the relevance of our observations in the context of clinical considerations.

Keywords: Mast cells, FcεRI, KIT, antigen, IgE, SCF, signaling

Introduction

Mast cells are central players in the initiation of inflammatory reactions associated with asthma, rhinitis, anaphylaxis, and other allergic diseases (1). These reactions are a consequence of physiological responses to several classes of biologically-active compounds released from mast cells whose functions likely initially evolved to participate in the body’s innate immune defense to invading pathogens (2–5). Such biologically-active compounds include histamine, serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine) and a variety of proteases, which are released following degranulation; eicosanoids, such as prostaglandin (PG)D2 and leukotriene (LT)C4, which are generated following the liberation of arachidonic acid from membrane phospholipids; and a variety cytokines and chemokines, which are released following the induction of gene expression (1–5). Traditionally, mast cell activation in allergic disease states has been considered as primarily an inappropriate TH2-driven response mediated through antigen-induced aggregation of IgE-occupied FcεRI (high affinity receptor for IgE) on the mast cell surface (1). However, studies conducted by a number of groups, including our own, have established that such activation is markedly influenced by other factors that alter the threshold for, and extent of, mast cell activation (6–15). Thus, mast cell-driven disease states may be as much influenced by these other factors as by antigen-driven responses alone.

Mast cells express a wide array of cell-surface receptors, in addition to the FcεRI, which in specific cases, when activated, synergistically enhance antigen-mediated degranulation and cytokine production (12,14). These receptors largely, but not exclusively, fall into three major categories: G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) including those for adenosine (A3 receptor) (7), macrophage inflammatory protein 1α (MIP-1α, CCL3) (CCR1) (16), the complement component C3a (C3aR) (17,18), sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) (S1P2R) (19) and PGE2 (EP3) (6,15,20); Toll-like receptors (TLRs) such as TLR2, 3, and 4 (8,21), and growth factor receptors such as the stem cell factor (SCF) receptor, KIT (9,10,22). It should be noted that a number of these ligands, for example C3a and S1P, induce mast cell activation independently of antigen (17–19).

Although it is currently unknown to what degree such synergistic interactions influence mast cell activation in vivo, it is probable that mast cells in a physiological setting would be exposed to one or a number of these agents. For example, mast cell homeostasis, at least in the human, is dependent on the continued activation of KIT by SCF (23–26). Therefore, antigen-mediated activation in vivo most likely occurs on a background of KIT activation. It is also possible that mast cells may be exposed to inflammatory mediators such as PGE2 and C3a following their appearance in the surrounding tissues as a consequence of the exacerbated inflammatory reactions associated with allergic asthma. A further consideration is that activating polymorphisms, mutations and alternatively spliced forms of receptors or signaling proteins may further modulate these responses. For example activating mutations or polymorphisms in disease states, such as the D816V KIT mutation in mastocytosis, may lead to exacerbated mast cell-driven reactions. The precise manner in which antigen-mediated mast cell activation is enhanced in the above scenarios, and the mechanisms by which the signals initiated by the diverse groups of receptors listed above are integrated into those initiated by the FcεRI, are largely unknown. Furthermore, how polymorphisms or point mutations in these receptors, and downstream signaling molecules, may influence mast cell activation in a physiological setting is unclear. A major focus of the research conducted in the Mast Cell Biology Section of the Laboratory of Allergic Diseases, NIAID, NIH, has been to accordingly investigate these responses and to identify key events in the integration of signal transduction pathways relating to these processes. In addition, we have been exploring how to translate our findings from these basic science approaches to potential therapies designed to inhibit mast cell responsiveness.

Integration of KIT- and FcεRI-induced signaling events leading to synergistically enhanced release of inflammatory mediators from human mast cells

Enhancement of FcεRI-mediated mast cell activation by KIT

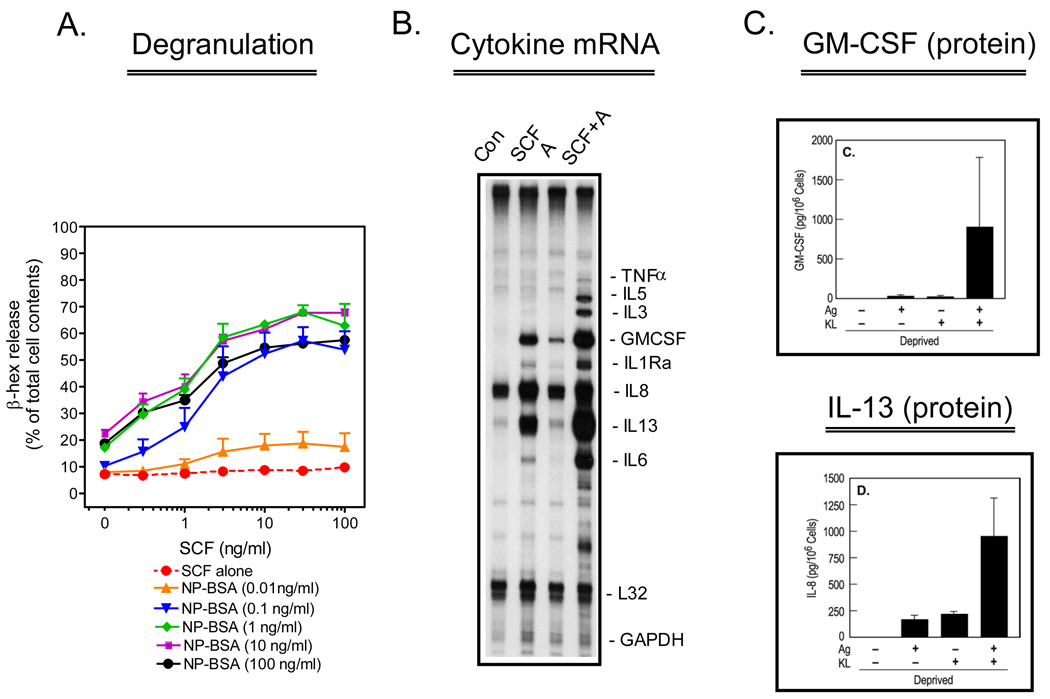

Previous studies conducted in rodent and human mast cells revealed that SCF, through KIT activation, markedly potentiates FcεRI-mediated mast cell degranulation and cytokine production (22,27–29). In studies conducted in collaboration with Dr. Michael Beaven (LMI/NHLBI/NIH) (10) and, in studies conducted in our laboratory (9), we similarly demonstrated that antigen-mediated degranulation and cytokine production were dramatically enhanced by SCF in human mast cells (Figure 1). These studies also revealed that SCF was capable of eliciting a maximal enhancement of degranulation even at concentrations of antigen that only minimally elicited a degranulation response in the absence of SCF (9). Furthermore, we observed that human mast cells minimally generated cytokines in response to antigen in the absence of SCF. However, in the presence of SCF, antigen induced the production of multiple cytokines including IL-6, IL-8, IL-13 and GM-CSF. Taken together, our data not only suggested that SCF enhances antigen-dependent responses, but also that, at low degrees of antigen-mediated FcεRI aggregation, the contribution of SCF to mast cell activation may be markedly more than that of antigen. Further studies revealed that, although KIT and FcεRI share many common signaling pathways, the inability of KIT to activate protein kinase C (PKC), a critical signaling event for mast cell degranulation (12) and cytokine production, may account for the inability of SCF to enhance these responses in the absence of antigen (10).

Figure 1.

Enhancement of antigen-induced mast cell activation by SCF. Human mast cells, derived from CD34+ progenitors, were sensitized overnight with anti-NP-human IgE (1 µg/mL) in the absence of cytokines. In A., sensitized cells were triggered for 30 minutes with the indicated concentrations of NP-BSA and SCF and degranulation monitored by the release of β-hexosaminidase (β-hex). The data are means+/− S.E.M. of n=2–5 experiments conducted in duplicate. In B., the cells were triggered for 2 hours with NP-BSA (A) (100 ng/mL), SCF (100 ng/mL) or both, then cytokine mRNA determined by RNase protection assay. In C., Cells were triggered as above for 16 hours then the release of the cytokines, GM-CSF and IL-13, was determined by ELISA. The date are means+/− S.E.M. of n=3 following correction for the spontaneous release. This research was originally published in Blood (A.: Tkaczyk et al., Blood. 2004;104:207–14; and B., C.: Hundley et al., Blood. 2004;104:2410–7).

The role of LAT2 in the integration of KIT- and FcεRI-mediated signaling events

Our earlier studies demonstrated that the ability of SCF to enhance antigen-mediated responses was linked to a similar synergistic activation of phospholipase (PL)Cγ1 and consequent increase in intracellular calcium concentrations (30). We therefore investigated how upstream signals produced by FcεRI and KIT were integrated to produce these downstream synergistic responses in mast cells. To do this, we initially explored early common signals induced by both receptors. Under conditions that we developed to optimize recovery of tyrosine phosphorylated proteins from activated human mast cells (31), we observed that SCF and antigen commonly induced the tyrosine phosphorylation of a protein of approximately 28–30 kD (9) which we subsequently identified as linker for activation of T cells 2 (LAT2) (formerly termed NTAL (non-T cell activation linker) or LAB (linker for activation of B cells) (32). Whereas antigen also induced the phosphorylation of the associated transmembrane adaptor molecule LAT, SCF induced the phosphorylation of LAT2 in the absence of appreciable LAT phosphorylation (9). Furthermore, LAT2 phosphorylation, but not LAT phosphorylation, induced by antigen was potentiated by SCF (9).

A role for LAT2 in antigen-mediated and SCF-enhanced degranulation was demonstrated by the ability of LAT2-targeted siRNA oligonucleotides to significantly inhibit these responses in parallel with a decrease in LAT2 expression (9). These observations were confirmed in human mast cells stably transduced with LAT2-targeted shRNA (33). Knock down of LAT also suppressed antigen-mediated and SCF-enhanced degranulation. These, and other data, led us to the conclusion that the lack of ability of SCF on its own to activate specific signals required for degranulation was linked to its inability to induce LAT phosphorylation in addition to the aforementioned inability to activate PKC. However, when the LAT signal was provided by antigen, then the enhanced phosphorylation of LAT2, which regulated an amplification pathway, allowed the synergistically enhanced degranulation to occur (9,12).

Using mast cells derived from the bone marrow of mice deficient in specific tyrosine kinases, and other approaches, we demonstrated that, whereas FcεRI employs the tyrosine kinases Lyn and Syk for LAT2 phosphorylation, KIT directly phosphorylates LAT2 (9). Similarly, in co-transfection studies utilizing mutant LAT2 constructs in 293T cells, we observed that Lyn, Syk, and KIT phosphorylate distinctly different tyrosine residues in LAT2 (33). Those residues phosphorylated by Syk (Y136, Y193, and Y233) were contained within recognized binding sites for the cytosolic adaptor molecule Grb2, whereas Lyn and KIT phosphorylated residues both inside and outside of these binding motifs (33). Despite not being recognizable PLCγ-binding domains, pull-down studies revealed that, once phosphorylated, the two terminal Grb2-binding sites in LAT2 recruited PLCγ1, suggesting that LAT2 may help regulate PLCγ1-dependent calcium mobilization in mast cells (33). This conclusion was further supported by the ability of LAT2-targeted siRNA oligonucleotides to inhibit antigen- and SCF-mediated calcium mobilization in human mast cells (33). The identity of other signaling molecules potentially recruited to the other residues phosphorylated by Lyn and KIT still remains to be determined. The selective phosphorylation of specific tyrosine residues on LAT2 by different tyrosine kinases, and the subsequent selective binding of associating signaling molecules, however, implies that specific regulatory signaling molecules may be selectively recruited to receptor-signaling assemblies in a kinase-dependent manner (33).

Phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)-dependent pathways

Having demonstrated that the early point of synergy regulating the SCF-enhanced antigen response was controlled by the tyrosine phosphorylation of LAT2 and that the downstream synergy was regulated by PLCγ-dependent calcium mobilization, we set out to identify intermediary steps in this amplification pathway. As our previous studies had demonstrated that the calcium signal required for degranulation was in part regulated by PI3K (30), we explored whether PI3K may contribute to the amplification pathway described above. In collaboration with Dr. Bart Vanhaesebroeck (University of London), we demonstrated that the ability of SCF to potentiate antigen-mediated degranulation was substantially reduced by inhibiting the p110δ subunit isoform of PI3K (34). Furthermore, our unpublished studies have revealed that the ability of SCF to enhance the antigen-dependent calcium signal is markedly attenuated in BMMCs expressing catalytically inactive p100δ or in mast cells treated with PI3K inhibitors. These data thus supported our thesis that PI3K is a critical player in the amplification pathway utilized by SCF for the potentiation of antigen-mediated responses.

As it had been proposed that PI3K may regulate calcium mobilization through the activation of the tyrosine kinase Btk (35), we explored the possibility that Btk may be the final link in the amplification pathway connecting LAT2 and PI3K to downstream enhancement of PLCγ1-dependent calcium mobilization. In Btk−/− BMMCs, we observed a partial reduction in the capacity to degranulate in response to antigen, but more interestingly, an inability of SCF to enhance the residual antigen-mediated degranulation and a reduced capacity for SCF to promote cytokine production (11). These events correlated with an inability of SCF to potentiate antigen-mediated PLCγ1-dependent calcium mobilization in these cells (11). Similar studies with Lyn−/− and Btk−/− / Lyn−/− BMMCs indicated that Lyn was a regulator of Btk for these responses (11).

Based on these studies and those of others (36,37), we proposed that FcεRI degranulation and cytokine production are regulated by a principal pathway which is regulated by the transmembrane adaptor molecule LAT and which regulates a rapid activation of PLCγ1 leading to an early rapid calcium mobilization; and a delayed amplification pathway regulated by LAT2 which leads to the PI3K- and Btk-driven enhancement and maintenance of the PLCγ1-dependent calcium signal. Furthermore, we proposed that KIT can access this amplification pathway for the potentiation of antigen-mediated degranulation (9).

In addition to its role in the regulation of mast cell mediator release, studies have also revealed an important role of PI3K in mast cell development, homing and survival (34). Little is known, however, about the intermediary signals in these processes. As the mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) pathway has been implicated in various cellular responses mediated by PI3K (38), we investigated the role of this pathway in mast cell responses (39). In both human and mouse mast cells stimulated via KIT or FcεRI, we observed a PI3K-dependent increase in the phosphorylation of tuberin, mTOR, p70S6 kinase (p70S6K), and 4E-BP1, which are components of the mTORC1 cascade (39). Rapamycin, a specific inhibitor of mTORC1, had little effect on antigen-mediated and SCF-enhanced degranulation, and SCF-induced cell adhesion, suggesting that mTORC1 did not contribute to these events (39). However, rapamycin partially inhibited SCF-mediated chemotaxis, SCF- and antigen-induced cytokine production, and SCF-dependent mast cell survival, implying that these events were, in part, regulated by the mTORC1 cascade (39). Interestingly, we observed that components of the mTORC1 cascade were constitutively phosphorylated in human tumor mast cells and that rapamycin could diminish the survival rate of these cells in culture (39). These data provided evidence that the mTORC1 cascade contributes to PI3K-regulated signals downstream of KIT and FcεRI for the selective regulation of specific mast cell function. Furthermore, these data also suggested that the dysregulated cell growth observed in the human tumor mast cells may be associated with aberrant activation of the mTORC1 cascade.

Enhancement of FcεRI-mediated mast cell activation by GPCRs

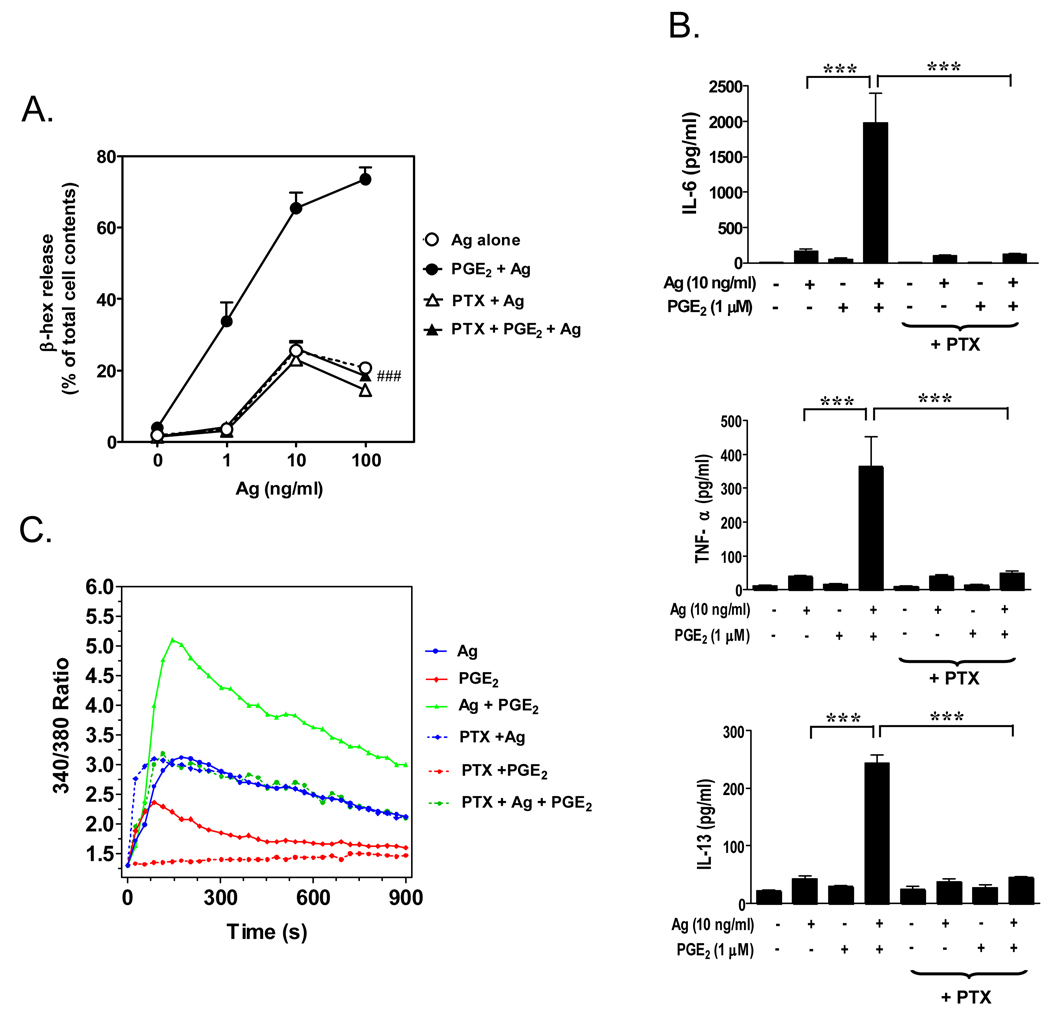

In addition to Kit, other receptors expressed on mast cells have been documented to profoundly influence mast cell activation (12–14). One such group of receptors is the GPCRs which includes the receptors for PGE2 (EP3 receptor), adenosine (A3 receptor), S1P (S1P2 receptor) and the complement component C3a (C3aR)(12). As the processes regulating these responses were relatively unknown, we next investigated the mechanism(s) by which GPCRs synergistically enhance antigen-mediated mast cell activation. A number of GPCR agonists were initially screened for their abilities to enhance antigen-mediated mast cell activation and based on the magnitude of responses; we selected PGE2 for further study (15). The synergistic responses mediated by PGE2 were determined to be mediated via Gαi indicating that the responses were mediated via the Gαi-linked EP3 PGE2 receptor (Figure 2). Although previous studies had suggested that the synergistic response of the GPCR agonist adenosine was mediated by a PI3K-dependent pathway (7), we determined that the enhancement of antigen-mediated mast cell activation produced by PGE2 was independent of PI3K but was more a consequence of trans-synergy in the activation of PLCβ in response to PGE2 and PLCγ1 in response to antigen (15). This synergistic activation results in a similar synergistically enhanced production of inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate, calcium entry, and activation of protein kinase C (PKC) (α and β), all of which are critical for degranulation.

Figure 2.

Enhancement of antigen-induced mast cell activation by the GPCR agonist PGE2. Mouse bone marrow-derived mast cells (BMMCs) were sensitized overnight with mouse monoclonal anti-DNP IgE (100 ng/mL) then pre-incubated with or without pertussis toxin (PTX) (1 µg/mL) for 4 hours before antigen (Ag) (DNP-HSA) or PGE2 or both were added. Degranulation (A.) was monitored by β-hexosaminidase (β-hex) release after 30 minutes incubation. Cytokine release (B.) was measured after 6 hours by ELISA. Changes in [Ca2+]i over the indicated intervals were monitored following loading the cells with FURA2-AM then challenging with Ag (10 ng/mL) or PGE2 (1 µM) or Ag together with PGE2. The Ca2+ data are representative of n=3 experiments conducted in duplicate. The data in A and B are presented as means +/− S.E. of (n=3–4) separate experiments conducted in duplicate. ###, p < 0.001 for comparison with Ag/PGE2 (A.). ***, p < 0.001 by Student’s t-test (B.). The ability of pertussis toxin to block the PGE2 responses indicates that they were mediated via the Gαi-linked EP3 receptor. This research was originally published in Cellular Signaling (Kuehn et al., Cell Signal. 2008;20:625–36).

Perspective, clinical implications, and potential therapeutic approaches

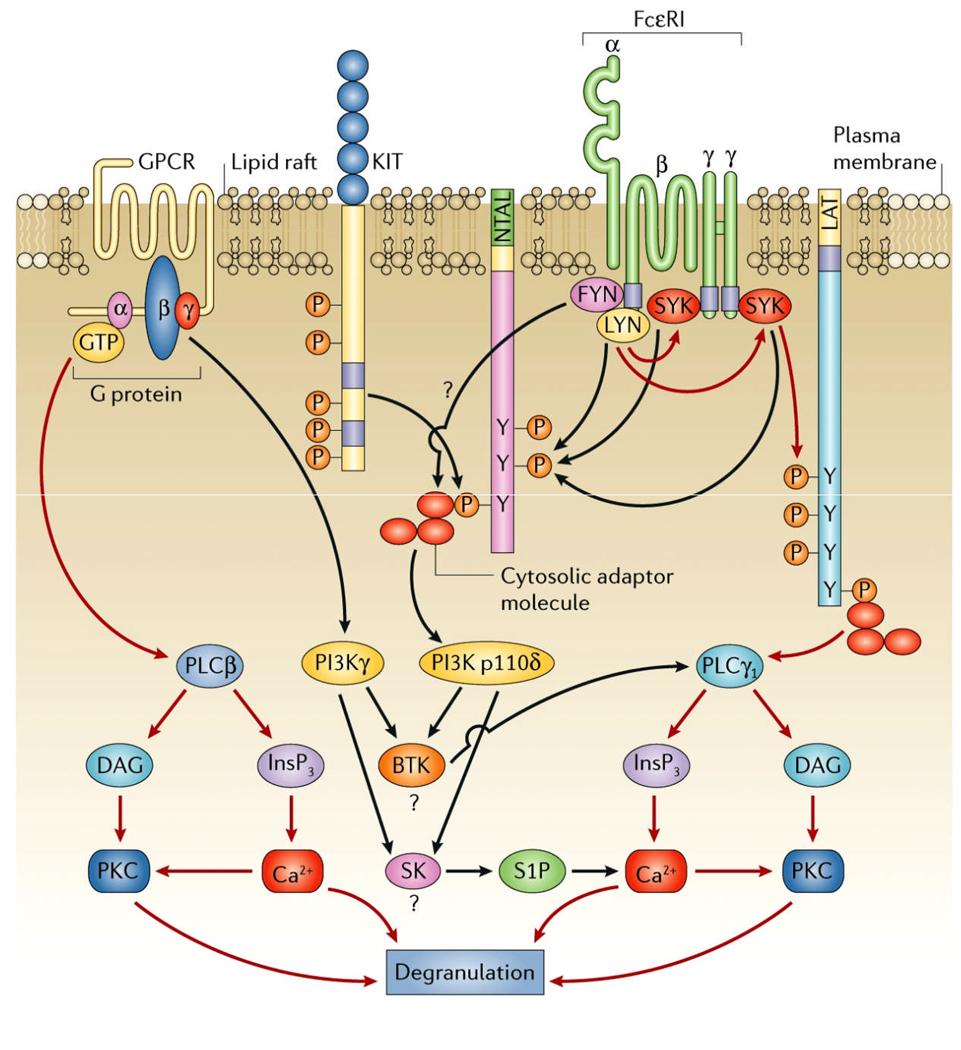

In summary, our studies have clearly demonstrated that specific receptors expressed on mast cells are capable of enhancing FcεRI-mediated mast cell activation utilizing alternative mechanisms to integrate the required signaling cascades (Figure 3). We are now investigating the relevance of these observations to specific disease states and determining how the information gleaned from our studies may aid in the design of potential therapeutic approaches for the treatment of mast cell-driven diseases. For example, it is possible that increased concentrations of agents such as PGE2 and C3a at sites of inflammation may further exacerbate ongoing mast cell activation. It is also conceivable that up-regulation of the expression of activating GPCRs on mast cells, under specific conditions, may also render mast cells hyper-sensitive to antigen. In disease states such as mastocytosis where activating mutations in KIT exist, elevated KIT signaling may further enhance its ability to potentate mast cell activation. In this regard, it is of interest to note that cases of unexplained anaphylaxis are often associated with mastocytosis (40).

Figure 3.

Integration of the signaling pathways induced by G protein coupled receptors, Kit, and the FcεRI. The red lines represent the principal signaling pathways initiated by these receptors and the black lines represent the complementary/amplification pathways utilized by these receptors for degranulation. This figure was originally published in Nature Reviews Immunology (Gilfillan and Tkaczyk, Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:218–30).

The recognition that receptors such as KIT enhance antigen-mediated mast cell degranulation has led us to consider whether concurrent inhibition of KIT- and FcεRI-mediated signaling would be an appealing approach for mast cell–related diseases (41,42). To establish proof of principle for this concept, we utilized the compound hypothemycin, which has been documented to block KIT activation (43). We observed that, in addition to blocking KIT activation and KIT-mediated mast cell adhesion, hypothemycin also blocked FcεRI-mediated mast cell activation and the ability of SCF to enhance these responses (43). As hypothemycin also significantly reduced an antigen-mediated anaphylaxis response in the mouse in vivo, these data may indeed provide a rationale for the development of compounds targeting similar multiple receptor-mediated signaling processes for the treatment of mast cell-driven disease states.

In conclusion, we believe the growing body of evidence illustrating the paradigm that the extent of mast cell activation may be as much dictated by other factors as much as antigen, has important implications for mast cell-related diseases such as asthma, anaphylaxis and rhinitis. Further studies are yet required to determine to what extent such events occur in specific disease states and to determine what are the precise underlying signal transduction mechanisms controlling the interactions in these conditions. However, the recognition that mast cell activation is influenced by multiple factors will decidedly help to optimize therapeutic approaches for the treatment of disorders involving mast cell activation.

Acknowledgments

Due to space constraints, not all pertinent literature could be cited. This does not imply that studies not cited are of lesser merit. This work was supported by the Division of Intramural Research, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.Metcalfe DD. Mast cells and mastocytosis. Blood. 2008;112:946–956. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-11-078097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mekori YA, Metcalfe DD. Mast cells in innate immunity. Immunol Rev. 2000;173:131–140. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2000.917305.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marshall JS. Mast-cell responses to pathogens. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:787–799. doi: 10.1038/nri1460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Galli SJ, Nakae S, Tsai M. Mast cells in the development of adaptive immune responses. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:135–142. doi: 10.1038/ni1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tkaczyk C, Jensen BM, Iwaki S, Gilfillan AM. Adaptive and innate immune reactions regulating mast cell activation: from receptor-mediated signaling to responses. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2006;26:427–450. doi: 10.1016/j.iac.2006.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gomi K, Zhu FG, Marshall JS. Prostaglandin E2 selectively enhances the IgE-mediated production of IL-6 and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor by mast cells through an EP1/EP3-dependent mechanism. J Immunol. 2000;165:6545–6552. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.11.6545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Laffargue M, Calvez R, Finan P, Trifilieff A, Barbier M, Altruda F, et al. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase γ is an essential amplifier of mast cell function. Immunity. 2002;16:441–451. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00282-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Qiao H, Andrade MV, Lisboa FA, Morgan K, Beaven MA. FcεR1 and toll-like receptors mediate synergistic signals to markedly augment production of inflammatory cytokines in murine mast cells. Blood. 2006;107:610–618. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-06-2271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tkaczyk C, Horejsi V, Iwaki S, Draber P, Samelson LE, Satterthwaite AB, et al. NTAL phosphorylation is a pivotal link between the signaling cascades leading to human mast cell degranulation following Kit activation and FcεRI aggregation. Blood. 2004;104:207–214. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-08-2769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hundley TR, Gilfillan AM, Tkaczyk C, Andrade MV, Metcalfe DD, Beaven MA. Kit and FcεRI mediate unique and convergent signals for release of inflammatory mediators from human mast cells. Blood. 2004;104:2410–2417. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-02-0631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iwaki S, Tkaczyk C, Satterthwaite AB, Halcomb K, Beaven MA, Metcalfe DD, Gilfillan AM. Btk plays a crucial role in the amplification of FcεRI-mediated mast cell activation by kit. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:40261–40270. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506063200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gilfillan AM, Tkaczyk C. Integrated signalling pathways for mast-cell activation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:218–230. doi: 10.1038/nri1782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rivera J, Gilfillan AM. Molecular regulation of mast cell activation. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;117:1214–1225. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kuehn HS, Gilfillan AM. G protein-coupled receptors and the modification of FcεRI-mediated mast cell activation. Immunol Lett. 2007;113:59–69. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2007.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kuehn HS, Beaven MA, Ma HT, Kim MS, Metcalfe DD, Gilfillan AM. Synergistic activation of phospholipases Cγ and Cβ: a novel mechanism for PI3K-independent enhancement of FcepsilonRI-induced mast cell mediator release. Cell Signal. 2008;20:625–636. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2007.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Toda M, Dawson M, Nakamura T, Munro PM, Richardson RM, Bailly M, Ono SJ. Impact of engagement of FcεRI and CC chemokine receptor 1 on mast cell activation and motility. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:48443–48448. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408725200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Woolhiser MR, Brockow K, Metcalfe DD. Activation of human mast cells by aggregated IgG through FcγRI: additive effects of C3a. Clin Immunol. 2004;110:172–180. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2003.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Venkatesha RT, Berla TE, Zaidi AK, Ali H. Distinct regulation of C3a-induced MCP-1/CCL2 and RANTES/CCL5 production in human mast cells by extracellular signal regulated kinase and PI3 kinase. Mol Immunol. 2005;42:581–587. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2004.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jolly PS, Bektas M, Olivera A, Gonzalez-Espinosa C, Proia RL, Rivera J, et al. Transactivation of sphingosine-1-phosphate receptors by FcεRI triggering is required for normal mast cell degranulation and chemotaxis. J Exp Med. 2004;199:959–970. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang XS, Lau HY. Prostaglandin E potentiates the immunologically stimulated histamine release from human peripheral blood-derived mast cells through EP1/EP3 receptors. Allergy. 2006;61:503–506. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2006.01043.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kulka M, Alexopoulou L, Flavell RA, Metcalfe DD. Activation of mast cells by double-stranded RNA: evidence for activation through Toll-like receptor 3. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;114:174–182. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.03.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bischoff SC, Dahinden CA. c-kit ligand: a unique potentiator of mediator release by human lung mast cells. J Exp Med. 1992;175:237–244. doi: 10.1084/jem.175.1.237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Iemura A, Tsai M, Ando A, Wershil BK, Galli SJ. The c-kit ligand, stem cell factor, promotes mast cell survival by suppressing apoptosis. Am J Pathol. 1994;144:321–328. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yee NS, Paek I, Besmer P. Role of kit-ligand in proliferation and suppression of apoptosis in mast cells: basis for radiosensitivity of white spotting and steel mutant mice. J Exp Med. 1994;179:1777–1787. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.6.1777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mekori YA, Oh CK, Metcalfe DD. The role of c-Kit and its ligand, stem cell factor, in mast cell apoptosis. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 1995;107:136–138. doi: 10.1159/000236955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Metcalfe DD, Mekori JA, Rottem M. Mast cell ontogeny and apoptosis. Exp Dermatol. 1995;4:227–230. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.1995.tb00250.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lukacs NW, Kunkel SL, Strieter RM, Evanoff HL, Kunkel RG, Key ML, Taub DD. The role of stem cell factor (c-kit ligand) and inflammatory cytokines in pulmonary mast cell activation. Blood. 1996;87:2262–2268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lin TJ, Befus AD. Differential regulation of mast cell function by IL-10 and stem cell factor. J Immunol. 1997;159:4015–4023. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gagari E, Tsai M, Lantz CS, Fox LG, Galli SJ. Differential release of mast cell interleukin-6 via c-kit. Blood. 1997;89:2654–2663. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tkaczyk C, Beaven MA, Brachman SM, Metcalfe DD, Gilfillan AM. The phospholipase C gamma 1-dependent pathway of FcεRI-mediated mast cell activation is regulated independently of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:48474–48484. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301350200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tkaczyk C, Metcalfe DD, Gilfillan AM. Determination of protein phosphorylation in FcεRI-activated human mast cells by immunoblot analysis requires protein extraction under denaturing conditions. J Immunol Methods. 2002;268:239–243. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(02)00210-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Iwaki S, Jensen BM, Gilfillan AM. Ntal/Lab/Lat2. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2007;39:868–873. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2006.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Iwaki S, Spicka J, Tkaczyk C, Jensen BM, Furumoto Y, Charles N, et al. Kit- and FcεRI-induced differential phosphorylation of the transmembrane adaptor molecule NTAL/LAB/LAT2 allows flexibility in its scaffolding function in mast cells. Cell Signal. 2008;20:195–205. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2007.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ali K, Bilancio A, Thomas M, Pearce W, Gilfillan AM, Tkaczyk C, et al. Essential role for the p110δ phosphoinositide 3-kinase in the allergic response. Nature. 2004;431:1007–1011. doi: 10.1038/nature02991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fluckiger AC, Li Z, Kato RM, Wahl MI, Ochs HD, Longnecker R, et al. Btk/Tec kinases regulate sustained increases in intracellular Ca2+ following B-cell receptor activation. EMBO J. 1998;17:1973–1985. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.7.1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saitoh S, Arudchandran R, Manetz TS, Zhang W, Sommers CL, Love PE, et al. LAT is essential for FcεRI-mediated mast cell activation. Immunity. 2000;12:525–535. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80204-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Parravicini V, Gadina M, Kovarova M, Odom S, Gonzalez-Espinosa C, Furumoto Y, et al. Fyn kinase initiates complementary signals required for IgE-dependent mast cell degranulation. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:741–748. doi: 10.1038/ni817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dann SG, Selvaraj A, Thomas G. mTOR Complex1-S6K1 signaling: at the crossroads of obesity, diabetes and cancer. Trends Mol Med. 2007;13:252–259. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2007.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim MS, Kuehn HS, Metcalfe DD, Gilfillan AM. Activation and function of the mTORC1 pathway in mast cells. J Immunol. 2008;180:4586–4595. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.7.4586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Akin C, Scott LM, Kocabas CN, Kushnir-Sukhov N, Brittain E, Noel P, Metcalfe DD. Demonstration of an aberrant mast-cell population with clonal markers in a subset of patients with “idiopathic” anaphylaxis. Blood. 2007;110:2331–2333. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-06-028100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jensen BM, Metcalfe DD, Gilfillan AM. Targeting kit activation: a potential therapeutic approach in the treatment of allergic inflammation. Inflamm Allergy Drug Targets. 2007;6:57–62. doi: 10.2174/187152807780077255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jensen BM, Akin C, Gilfillan AM. Pharmacological targeting of the KIT growth factor receptor: a therapeutic consideration for mast cell disorders. Br J Pharmacol. 2008 doi: 10.1038/bjp.2008.204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jensen BM, Beaven MA, Iwaki S, Metcalfe DD, Gilfillan AM. Concurrent inhibition of kit- and FcεRI-mediated signaling: coordinated suppression of mast cell activation. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2008;324:128–138. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.125237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]