Summary

This paper discusses impacts of climate change on the ecology of avian influenza viruses (AI viruses), which presumably co-evolved with migratory water birds, with virus also persisting outside the host in subarctic water bodies. Climate change would almost certainly alter bird migration, influence the AI virus transmission cycle and directly affect virus survival outside the host. The joint, net effects of these changes are rather unpredictable, but it is likely that AI virus circulation in water bird populations will continue with endless adaptation and evolution. In domestic poultry, too little is known about the direct effect of environmental factors on highly pathogenic avian influenza transmission and persistence to allow inference about the possible effect of climate change. However, possible indirect links through changes in the distribution of duck-crop farming are discussed.

Keywords: Avian influenza, Bird migration, Climate change, Disease ecology

Introduction

Highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) H5N1 forms a spectacular example of an emerging disease (6), with a rapid rise in incidence and marked geographic expansion. At the end of 2003 and early in 2004 there was a subcontinental-scale epizootic wave that swept across south-eastern Asia. Subsequently, the area was hit by a panzootic wave that started in 2005, which had a major impact not only on the livelihood of the affected rural populations, but also on national economies, thus disrupting the international trade of live poultry and poultry products. In Southeast Asia alone, it was estimated that in 2005 and 2006 HPAI H5N1 virus outbreaks caused the death of 140 million domestic birds, with total economic losses estimated to amount to US$10 billion (12). More importantly still, the poultry disease has a major human health dimension. By April 2008, HPAI H5N1 virus had infected humans in 14 countries, resulting in the death of over 241 people out of 382 cases (32). Scientists generally agree that widespread circulation of avian influenza viruses increases the chances of the virus evolving into a form that could pass between humans and trigger a human influenza pandemic of unknown magnitude (11, 31). The probability of such an event taking place is difficult to ascertain. However, the potential impact of such a deadly human-adapted avian influenza virus is considered so great that HPAI H5N1 viruses circulating in poultry continue to attract worldwide attention from the public and the media, including in countries where the disease was quickly contained and had relatively little impact. In 2005 the HPAI H5N1 virus started spreading westward across Eurasia, both with wild birds and in poultry, triggering a major international sociopolitical discussion on how many anti-viral drugs or vaccines should be stockpiled as a precautionary measure. Since then, little has changed in terms of pandemic risk. The virus is still circulating endemically in several countries and occasional human infections continue to be reported.

The upsurge of HPAI H5N1 epizootic waves has been linked to changes in agricultural practices, intensification of the poultry sector, and globalisation of trade in live poultry and poultry products (27). The links between climate change and avian influenza (AI) are as yet mostly unexplored. For example, a search in the ISI Web of Science on ‘climate change’ yields 33,285 records and a search on ‘avian influenza’ yields 2,646, but a search for records containing both expressions yields only 4 results, with only one reference discussing the question explicitly, and concluding that the evolution of the disease was not directly affected by climate change (7). However, given that avian influenza viruses circulate naturally in the form of a gene pool in wild water birds, particularly in migratory ducks, geese and swans, it is relevant to ask how climate change may affect the ecology and evolution of avian influenza viruses, both in wild avifauna and in poultry. This paper will address that question firstly in relation to AI viruses naturally present in wild bird populations, and secondly in relation to HPAI spread and persistence in domestic poultry.

Avian influenza in wild birds: the natural system

Wild water birds form the natural reservoir of all influenza A viruses. There is considerable genetic variability in terms of the different subtypes of AI viruses present in wild water bird populations, enhanced by continued re-assortment of the eight genetic segments present in the genome of the virion (for convenience, the virus subtypes are grouped by their hemagglutinin and neuraminidase viral antigens, HA and NA, respectively). The distribution of AI viruses among wild birds is uneven, as it is influenced by both bird species and eco-geography. The general pattern is that most AI virus isolations are recorded in wild water birds, in the orders Anseriformes (in particular in the family Anatidae: ducks, swans and geese) and Charadriiformes (shorebirds and waders) (20). However, the former harbours the highest diversity and prevalence of AI viruses. Within the Anseriform order, the Anatidae family, and in particular the Anatinae sub-family (10), has the highest prevalence and diversity of AI viruses. The mallard duck (Anas platyrhynchos) is the foremost AI virus host among the dabbling duck species. Wild ducks presumably form an important source of virus spill-over to poultry.

The persistence of AI viruses in duck populations on a year-round basis relies on the annual recruitment of large numbers of juvenile ducklings providing immunologically naïve hosts aiding viral replication, shedding and transmission. Also important for the sustenance of the transmission cycle is the survival of the virus outside the host, in water. Water facilitates faecal–oral transmission, enables survival of virus in the absence of hosts, and helps to redistribute viruses among different hosts. Redistribution is arguably the key to the sustained presence of AI viruses in water birds across the Holarctic. Pathogen avoidance is one of the evolutionary drivers of dispersal in host animal populations. With dispersal evolving into migration, AI viruses must have co-evolved with their host behaviour to accommodate the migration cycle. For example, AI viruses usually cause benign, subclinical infections in their migratory water bird hosts, and during their stay in the wintering sites the prevalence of infection is usually lower than 5% (16). A virus causing acute disease in water bird hosts would have less chance of being transmitted over long distances; low pathogenicity and yet sufficient ability to replicate is what we would expect from a virus that has adapted to bird migration. Given that AI viruses are naturally transmitted through the faecal–oral route it helps when viruses can survive for weeks or months in cold water, and for many years in ice bodies. AI viruses were isolated from ice in lakes in Siberia at a time when wild birds had already moved out of the region (33). Hence, virus persists outside the host in the subarctic breeding areas after the birds depart for their autumn migration and is still present when the birds return the following spring. The breeding season in subarctic Siberia is usually very brief, as migratory bird populations start migrating southward with their newborn juveniles to escape the first frosts, already arriving in pre-migration staging areas from mid-summer onward. In these staging areas, which are not far south of the breeding areas, highly concentrated numbers of water birds of several different species are brought together from different breeding sites in Siberia. The birds remain in these areas for about a month, during which time the juvenile birds gain strength whilst adults undergo wing moulting to prepare for the long-distance autumn migration. Hence, birds during staging are not only present at peak densities, they are mostly flightless, and also heterogeneous in terms of bird species, breeding localities and, presumably, AI viruses. The peaks observed in the prevalence of AI in samples from birds in these pre-migration concentrations suggest that these conditions support maximal transmissions across wild water birds (16). This results in the redistribution of AI viruses belonging to different migration flyways. In summary, the existence of a highly diverse pool of rather benign AI viruses that are transmitted by the faecal–water–oral route and that survive well in cold and frozen water is not surprising given the behaviour of migratory water birds.

There are also ample variations in migratory behaviour among Anatidae species, even within populations. In general terms, the proportion of migratory species and the extent of migratory behaviour depend on the climatic conditions. In areas with harsh, cold climates most bird species migrate during the autumn to escape the frost. Areas further southwards, with higher temperatures or even subtropical climates, show a proportionally higher number of resident bird species. This translates into a range of different migratory behaviour patterns of Anatidae (25). Some species are completely migratory, with distinct winter and summer habitats and rather long-distance migration. Others are mostly sedentary species that occur at similar latitudes and move across comparatively short distances, in accordance with local feed availability and/or climatic variability. An intermediate situation is represented by partially migratory species, with a fraction of the population resident year-round at intermediate latitudes and the remainder of the population migrating along a north–south axis (e.g. the mallard Anas platyrhynchos). Apart from interspecies variability each bird species or population displays marked plasticity in response to the within-season weather variability.

Climate change is reported to affect wild bird distribution in a variety of ways. Northward shifts in distributions have been reported in many species and have been attributed to climate change (3, 17, 22). Climate change is also considered to influence species composition, with increased diversity expected in northern latitudes. Declines in the number of species undertaking long-distance migrations have been observed in many instances (3, 23). The possible effect of climate change on the dates of spring migration has been extensively studied, and generally the results of these studies show that spring migration is taking place earlier. The effect of climate change on the timing of autumn migration appears to be species-specific and heterogeneous (4, 8, 15, 24). Changes in the populations of some species of waterfowl have also been observed, but have been difficult to link to climate change because of the confounding factor of losses of natural habitat, and population increases resulting from the more and more frequent use of agricultural food by some species groups such as geese (1, 2, 19). All these changes in population, distribution, and movement patterns can affect the redistribution of AI viruses among birds of different age classes, species and flyways. Furthermore, extreme climatic events may trigger abnormal population movements, as was apparently observed in January 2006 when mute swan populations fled a cold weather spell that hit the eastern Caspian Sea basin, presumably spreading HPAI H5N1 virus towards Western Europe.

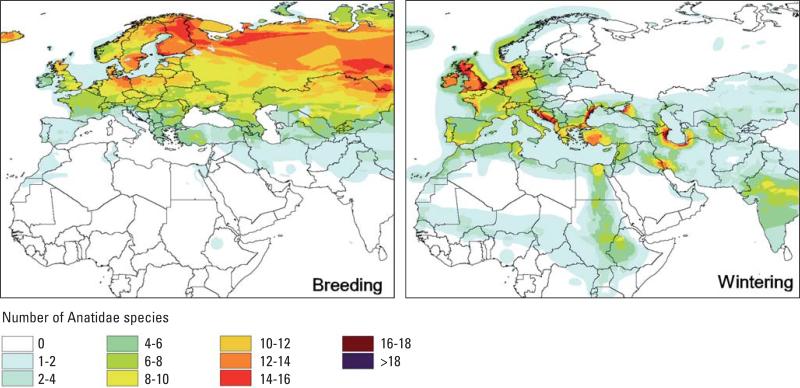

Figure 1 shows the distribution of the breeding and wintering areas of Anatidae (ducks, geese and swans) across the Western Palearctic, as derived from documented wild bird distributions. As shown, there is a very broad range of locations for summer breeding and a distinct concentration of locations for wintering, mainly comprising coastal areas of the North Sea and wetland shores of the Mediterranean Sea, Black Sea and Caspian Sea. These distributions apply in general terms (i.e. the main wetlands are static), but are highly dynamic at a finer scale. Local food availability, weather, hunting patterns, agriculture, and wetland water management, have all been shown to affect the local bird distributions, even over a short space of time.

Fig. 1. Distribution of Anatidae breeding and wintering areas.

Source: Adapted from del Hoyo, Elliott and Sargatal (9)

Climate change predictions show increases in average temperatures in areas near to the arctic, more so than for southern latitudes. Comparing Figure 1 in the current paper to Figures 4 and 5 of the paper by Stone in this volume (30), one observes that Anatidae breeding habitats are directly concerned, as these coincide with the areas in which the highest changes in temperature are predicted. Hence, climate change will directly affect the migration cycle of these birds. We lack, however, data and knowledge to be able to infer how these changes may influence the prevalence and diversity of AI viruses circulating in the wild water bird reservoir. AI viruses have co-evolved with migratory waterfowl over millions of years and have survived and withstood many eras of climatic turbulence. AI viruses in wild water birds distributed across the Palearctic and Nearctic are in relative evolutionary stasis.

Arguably, the indirect effects on poultry disease are even more important given that natural ecologies and farming landscapes cannot be fully separated. An increase in the proportion and number of birds over-wintering in the subarctic areas may result in very high densities of birds competing for the limited feed resources available. This could potentially enhance interspecies virus transmission, involve a larger spectrum of avian host species or alter the virus transmissibility, both to wild birds and domestic poultry. In the wintering areas, increasingly, wild waterfowl, geese in particular, are observed feeding on cultivated crops and in some countries have thus become a temporary crop pest (1, 19). This has been attributed by some to lack of feed resources in the natural habitat, but milder temperatures resulting in a higher proportion of resident populations could also amplify that pattern. Novel ecologies will emerge and the farming landscape will form an integral component of these dynamics (19). In addition, with water and ice bodies in the arctic areas containing concentrations of AI viruses (33), rises in temperature will change the conditions of virus survival, and with it virus ecology.

Predictions about how changes in viral persistence in the environment, together with the alterations in host migratory patterns, may affect the epidemiology of AI in general are close to crystal-ball gazing. However, with wild bird migration patterns and AI evolution being intertwined, and climate change acting on both wild bird behaviour and directly on virus survival outside the host, the seasonal and geographic patterns of the AI virus cycles in wild birds are very likely to change in the future. It should be remembered, however, that the associated avifauna-AI viruses have survived climate changes many times during their joint evolutionary history.

Avian influenza and highly pathogenic avian influenza in domestic poultry

Highly pathogenic avian influenza is a poultry disease evolving from low pathogenicity AI virus circulating in wild birds and introduced in terrestrial poultry of sufficient flock size or density. Infection of wild birds by HPAI H5N1 viruses is the result of spill-back of HPAI virus from domestic to wild birds. The HPAI H5N1 panzootic is atypical in that wild birds have probably been involved in the spread of the disease (21). Some of the long-distance introductions were probably mediated by species such as wild ducks, which have been shown in laboratory conditions to be able to excrete large quantities of virus whilst showing few clinical signs of disease (18). However, whilst wild birds have been implicated in some virus introductions, there is also the consensus view that HPAI H5N1 spreads locally through human-related activities, including trade in poultry and poultry products. HPAI is a disease of domestic poultry, and spreads and persists within that system.

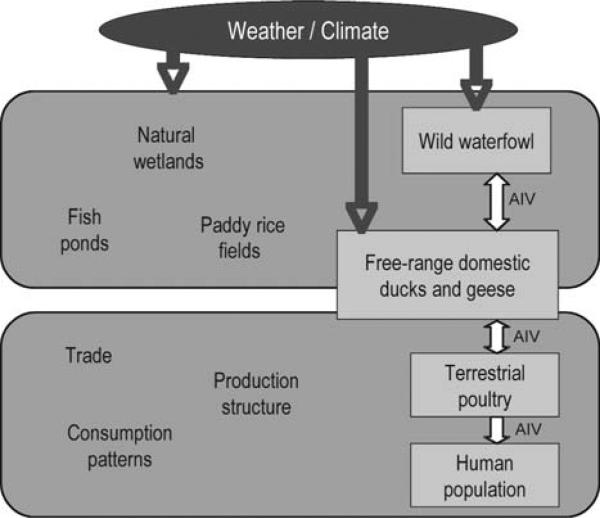

To date, little can possibly link climate change to the emergence of HPAI as a disease of global significance. Rather, several other factors can be cited. First, intensification of the poultry sector results in high densities of homogeneous poultry genotypes that create local conditions favoring the evolution of highly pathogenic strains. Second, globalisation of poultry markets, combined with illegal trade, mean that a highly pathogenic strain can now very quickly spread over considerable distances. Third, changes in agricultural practices have resulted in increasing pressure for agricultural land over natural wetlands and to higher contacts between wild and domestic avifauna (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

The avian influenza virus (AIV) flow in a coupled natural and human system

Very little is known about the direct impact of environmental factors on the transmission and persistence of HPAI viruses. One should recall that even in 2005, only a couple of references dating back to the early 1990s were reporting results on the persistence of AI viruses in water as a function of physical-chemical conditions (28), and were reporting that AI virus persistence was decreasing as a function of temperature (29). Several research projects have since been developed to address the issue of the persistence of HPAI viruses in various conditions, and results are now starting to be published (5). Up to 2005, the lower winter temperatures were repetitively cited as the main factor of seasonality in observed AI prevalence, because the higher virus persistence in cold water was thought to translate into a much higher chance of transmission. But if temperature appears to be a critical parameter of viral persistence in laboratory conditions, we have learned from several HPAI local epizootics that it may not be such an important limiting factor in field conditions. Indonesia, where HPAI H5N1 virus persists endemically, has a constantly high temperature and humidity. HPAI H5N1 virus spread to several sub-Saharan African countries and persisted or re-occurred in countries with year-round high temperatures and a marked dry season. In Germany, HPAI H5N1 virus was reported twice, once in the middle of winter 2006, and once in mid-summer 2007. In addition to providing an equivocal view on the role of temperature in HPAI seasonality, these examples reflect the fact that we actually have little knowledge on the direct influence of environmental factors such as climate on AI epidemiology.

However, possible indirect impacts can be better documented (Fig. 2). Recent works have linked the persistence of HPAI H5N1 virus to areas with high densities of domestic ducks, which was found to be one of the main risk factors for the persistence of HPAI H5N1 virus in Thailand (13) and Vietnam (26), and similar results are expected in Indonesia. This may also apply to Africa, where there are indications that domestic ducks play a role in the persistence of HPAI in Egypt and Nigeria. An interesting feature of Asia is that ducks are traditionally kept in rice paddies, with ducklings feeding on left-over rice grains in post-harvested rice paddies. In some areas, ducklings are also released during the early stage of the rice growing cycle as an integrated control measure against the golden apple snail. With most of the rice cropping relating to the monsoon rains, duck production has become synchronised with the post-monsoon rice harvest, and most meat production takes place during the autumn and early winter months. In Southeast Asia, meat duck production typically peaks during the month of January, just prior to the Chinese New Year. Post-harvest rice feeding is also important for the production of duck eggs, but requires year-round availability of duck feed to maintain the egg production. Therefore, duck egg production is mostly confined to areas such as river deltas and plains, where the local hydrology and irrigation support rice crop cycles outside the monsoon rains (14). This type of farming system is frequent in Asia wherever there is sufficient water, such as in floodplains (e.g. Thailand), deltas (the Red River and the Mekong in Vietnam), or nearby wetlands (e.g. the Poyang Lake area, China), or even small ponds (e.g. Indonesia). Future studies are expected to show a similar link between duck populations, rice farming and the persistence of HPAI H5N1 virus in other Asian countries such as Bangladesh and Myanmar, where domestic ducks are thought to be an important driver of HPAI spread and persistence, and their seasonal and spatial distribution is closely intertwined with rice production. The most recent work of the authors also statistically demonstrated that rice cropping intensity was an even better predictor of HPAI H5N1 distribution in Thailand and Vietnam than duck censuses, probably because it better defines where duck populations circulate (Gilbert et al., unpublished). Therefore, changes in the distribution of rice cultivation resulting from climate changes, such as caused by more frequent droughts or floods, will indirectly change the distribution and abundance of the millions of ducks raised in association with these crops, and may have a critical impact on the distribution of HPAI persistence risk.

Ducks also form the link between the genetic pool of AI viruses (i.e. wild waterbirds) and terrestrial poultry, where most of HPAI spread takes place, resulting in high human exposure (Fig. 2). By changing the distribution, composition and abundance of wild duck populations, climate change will indirectly modify the interface between domestic and wild waterfowl, and with it the potential AI virus flow between aquatic and terrestrial poultry.

Conclusion

In conclusion, it is thought that the biggest change in AI epidemiology resulting from climate change will be brought about by changes in the distribution, composition and migration behaviour of wild bird populations that harbor the genetic pool of AI viruses and in which natural AI transmission cycles take place. In contrast, HPAI, which remains largely confined to domestic poultry, has been spreading worldwide successfully in a very wide range of climatic conditions. Although the effect of the environment on HPAI transmission and persistence is as yet poorly understood, these observations support the idea that climate change will have very little effect on HPAI epidemiology. However, we may anticipate indirect effects, mainly those occurring as a result of the influence of climate change on agro-ecosystems associating duck and crop production, and of changes in the distribution of domestic–wild waterfowl contact points.

References

- 1.Abraham KF, Jefferies RL, Alisauskas RT. The dynamics of landscape change and snow geese in mid-continent North America. Global Change Biol. 2005;11:841–855. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bethke RW, Nudds TD. Effects of climate-change and land-use on duck abundance in Canadian prairie-parklands. Ecol. Applic. 1995;5:588–600. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bohning-Gaese K, Lemoine N. Moller A, Fiedler W, Berthold P, editors. Importance of climate change for the ranges, communities and conservation of birds. In Birds and climate change. Adv. ecol. Res. 2004;35:211–236. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Both C, Artemyev AV, Blaauw B, Cowie RJ, Dekhuijzen AJ, Eeva T, Enemar A, Gustafsson L, Ivankina EV, Jarvinen A, Metcalfe NB, Nyholm NEI, Potti J, Ravussin P-A, Sanz JJ, Silverin B, Slater FM, Sokolov LV, Török J, Winkel W, Wright J, Zang H, Visser ME. Large-scale geographical variation confirms that climate change causes birds to lay earlier. Proc. roy. Soc. Lond., B, biol. Sci. 2004;271:1657–1662. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2004.2770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown JD, Swayne DE, Cooper RJ, Burns RE, Stallknecht DE. Persistence of H5 and H7 avian influenza viruses in water. Avian Dis. 2007;51:285–289. doi: 10.1637/7636-042806R.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control What are ‘emerging’ infectious diseases? [22 April 2007];2007 Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/NCIDOD/eid/about/background.htm.

- 7.Chastel C. Emergence of new viruses in Asia: is climate change involved? Méd. Mal. infect. 2004;34:499–505. doi: 10.1016/j.medmal.2004.07.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cotton PA. Avian migration phenology and global climate change. Proc. natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:12219–12222. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1930548100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Del Hoyo J, Elliott A, Sargatal J. Vol. 1: Ostrich to Ducks. Lynx Edicions; Barcelona: 1992. Handbook of the birds of the world. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Delogu M, De Marco MA, Donatelli I, Campitelli L, Catelli E. Ecological aspects of influenza A virus circulation in wild birds of the Western Palearctic. Vet. Res. Commun. 2003;27:101–106. doi: 10.1023/b:verc.0000014125.49371.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferguson NM, Fraser C, Donnelly CA, Ghani AC, Anderson RM. Public health risk from the avian H5N1 influenza epidemic. Science. 2004;304:968–969. doi: 10.1126/science.1096898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO)/World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE) A global strategy for the progressive control of highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) 2005. FAO, Rome, OIE, Paris, World Health Organization, Geneva.

- 13.Gilbert M, Chaitaweesub P, Parakamawongsa T, Premashtira S, Tiensin T, Kalpravidh W, Wagner H, Slingenbergh J. Free-grazing ducks and highly pathogenic avian influenza, Thailand. Emerg. infect. Dis. 2006;12:227–234. doi: 10.3201/eid1202.050640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gilbert M, Xiao XM, Chaitaweesub P, Kalpravidh W, Premashthira S, Boles S, Slingenbergh J. Avian influenza, domestic ducks and rice agriculture in Thailand. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2007;119:409–415. doi: 10.1016/j.agee.2006.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gordo O, Sanz JJ. Climate change and bird phenology: a long-term study in the Iberian Peninsula. Global Change Biol. 2006;12:1993–2004. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Halvorson DA, Kelleher CJ, Senne DA. Epizootiology of avian influenza: effect of season on incidence in sentinel ducks and domestic turkeys in Minnesota. Appl. environ. Microbiol. 1985;49:914–919. doi: 10.1128/aem.49.4.914-919.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hitch AT, Leberg PL. Breeding distributions of north American bird species moving north as a result of climate change. Conserv. Biol. 2007;21:534–539. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2006.00609.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hulse-Post DJ, Sturm-Ramirez KM, Humberd J, Seiler P, Govorkova EA, Krauss S, Scholtissek C, Puthavathana P, Buranathai C, Nguyen TD, Long HT, Naipospos TSP, Chen H, Ellis TM, Guan Y, Peiris JSM, Webster RG. Role of domestic ducks in the propagation and biological evolution of highly pathogenic H5N1 influenza viruses in Asia. Proc. natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:10682–10687. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504662102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jefferies RL, Drent RH. Arctic geese, migratory connectivity and agricultural change: calling the sorcerer’s apprentice to order. Ardea. 2006;94:537–554. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kawaoka Y, Chambers TM, Sladen WL, Webster RG. Is the gene pool of influenza viruses in shorebirds and gulls different from that in wild ducks? Virology. 1988;163:247–250. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(88)90260-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kilpatrick AM, Chmura AA, Gibbons DW, Fleischer RC, Marra PP, Daszak P. Predicting the global spread of H5N1 avian influenza. Proc. natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:19368–19373. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609227103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.La Sorte FA, Thompson FR. Poleward shifts in winter ranges of North American birds. Ecology. 2007;88:1803–1812. doi: 10.1890/06-1072.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lemoine N, Bohning-Gaese K. Potential impact of global climate change on species richness of long-distance migrants. Conserv. Biol. 2003;17:577–586. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mills AM. Changes in the timing of spring and autumn migration in North American migrant passerines during a period of global warming. Ibis (London) 2005;147:259–269. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Newton I, Dale LC. Effects of seasonal migration on the latitudinal distribution of west Palaearctic bird species. J. Biogeogr. 1997;24(6):781–789. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pfeiffer D, Minh P, Martin V, Epprecht M, Otte J. An analysis of the spatial and temporal patterns of highly pathogenic avian influenza occurrence in Vietnam using national surveillance data. Vet. J. 2007;174:302–309. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2007.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Slingenbergh J, Gilbert M, DeBalogh K, Wint W. King LJ, editor. Ecological sources of zoonotic diseases. In Emerging zoonoses and pathogens of public health concern. Rev. sci. tech. Off. int. Epiz. 2004;23(2):467–484. doi: 10.20506/rst.23.2.1492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stallknecht DE, Kearney MT, Shane SM, Zwank PJ. Effects of pH, temperature, and salinity on persistence of avian influenza viruses in water. Avian Dis. 1990;34:412–418. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stallknecht DE, Shane SM. Host range of avian influenza virus in free-living birds. Vet. Res. Commun. 1988;12:124–141. doi: 10.1007/BF00362792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stone DA. de La Rocque S, Morand S, Hendrickx G, editors. Predicted climate changes for the years to come and implications for disease impact studies. In Climate change: the impact on the epidemiology and control of animal diseases. Rev. sci. tech. Off. int. Epiz. 2008;27(2):319–330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Webster RG, Walker EJ. Influenza: The world is teetering on the edge of a pandemic that could kill a large fraction of the human population. Am. Scientist. 2003;91:122–129. [Google Scholar]

- 32.World Health Organization (WHO) WHO epidemic and pandemic alert and response. [30 April 2008];Cumulative number of confirmed human cases of avian influenza A/(H5N1) reported to WHO. 2006 Available at: http://www.who.int/csr/disease/avian_influenza/country/en/

- 33.Zhang G, Shoham D, Gilichinsky D, Davydov S, Castello JD, Rogers SO. Evidence of influenza A virus RNA in Siberian lake ice. J. Virol. 2006;80:12229–12235. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00986-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]