Abstract

Pregnancy has both short-term effects and long-term consequences. For women who have an autoimmune disease and subsequently become pregnant, pregnancy can induce amelioration of the mother’s disease, such as in rheumatoid arthritis, while exacerbating or having no effect on other autoimmune diseases like systemic lupus erythematosus. That pregnancy also leaves a long-term legacy has recently become apparent by the discovery that bi-directional cell trafficking results in persistence of fetal cells in the mother and of maternal cells in her offspring for decades after birth. The long-term persistence of a small number of cells (or DNA) from a genetically disparate individual is referred to as microchimerism. While microchimerism is common in healthy individuals and is likely to have health benefits, microchimerism has been implicated in some autoimmune diseases such as systemic sclerosis. In this paper, we will first discuss short-term effects of pregnancy on women with autoimmune disease. Pregnancy-associated changes will be reviewed for selected autoimmune diseases including rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus and autoimmune thyroid disease. The pregnancy-induced amelioration of rheumatoid arthritis presents a window of opportunity for insights into both immunological mechanisms of fetal-maternal tolerance and pathogenic mechanisms in autoimmunity. A mechanistic hypothesis for the pregnancy-induced amelioration of rheumatoid arthritis will be described. We will then discuss the legacy of maternal-fetal cell transfer from the perspective of autoimmune diseases. Fetal and maternal microchimerism will be reviewed with a focus on systemic sclerosis (scleroderma), autoimmune thyroid disease, neonatal lupus and type I diabetes mellitus.

Keywords: autoimmune disease, pregnancy, microchimerism, systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis

PREGNANCY IN WOMEN WITH PRE-EXISTING AUTOIMMUNE DISEASE

Autoimmune disease may complicate pregnancy in many different ways adding to the immunologic challenges already faced by the mother. The maternal immune system must avoid rejecting a semi-allogeneic fetus, remain immunocompetent to fight infections, and clear abnormal cells (e.g. precancerous) that could be harmful to the mother or fetus. Symptoms of an autoimmune disease could improve, worsen, or remain unchanged when a woman becomes pregnant depending upon her specific autoimmune disease. Immunologic factors contributing to the classic amelioration of symptoms associated with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and multiple sclerosis during pregnancy are not well understood. Interestingly, events in normal placental biology may drive maternal peripheral tolerance to fetal antigens that could explain the dramatic pregnancy-associated improvement in symptoms of women with RA. Most autoimmune diseases, however, do not improve during pregnancy. A woman with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) typically has an unpredictable disease course and is at increased risk for several obstetric complications (preterm labor, fetal death). Autoimmune responses in the mother may also target the fetus when autoantibodies cross the placenta, such as neonatal lupus syndrome (NLS) and neonatal thyrotoxicosis.

The heterogeneity of immune defects across autoimmune diseases is reflected in the varying response of each disease in the context of pregnancy. Autoimmune diseases are thought to be immune reaction to self-antigens due to defects in T and/or B cell selection or regulation. T cells and B cells recognize self or foreign peptides presented on the cell surface by a major histocompatibility complex molecule, referred to as human leukocyte antigens (HLA). Autoimmunity may occur in a genetically susceptible individual if a self-antigen is inadvertently targeted by a T or B cell when environmental or other factors trigger a break in self-tolerance. Many models of autoimmune disease pathogenesis invoke a role for CD4 T cells, a subset of T cells recognizing peptides presented by HLA class II molecules. Most autoimmune diseases are associated with one or more polymorphic HLA class II genes. HLA-DRB1*03 (Caucasians) and HLA-DQB1*0303 (Chinese) are both strongly associated with Graves’ disease.(Weetman and McGregor 1994; Wong et al. 1999) For some diseases, a very specific HLA sequence has been identified as a risk factor. For example, different HLA DRB1 alleles that are associated with RA encode a similar amino acid sequence of the DRβ1 polypeptide chain, referred to as the “shared epitope”.(Gregersen et al. 1987) In contrast, only a weak association between SLE susceptibility and HLA-DRB1*15 or DRB1*03 has been found in specific ethnic groups; it has been suggested that these associations are instead related to genes in linkage disequilibrium (e.g. gene encoding tumor necrosis factor-alpha with HLA-DRB1*15).(Jacob et al. 1990; Vyse and Kotzin 1998)

Sex hormones and the immunologic effects of pregnancy have been investigated in autoimmunity. The well-studied relationship between sex hormones and lupus-like disease in animal models suggests a contributory role for estrogen in disease exacerbation and possibly in disease susceptibility. SLE may occur more frequently in women who have taken birth control pills and in postmenopausal women taking hormone replacement therapy.(Costenbader et al. 2007; Sanchez-Guerrero et al. 1995; Sanchez-Guerrero et al. 1997) However, it is unlikely that differences in sex hormone levels between women and men explain the broad predilection of autoimmune diseases for women. Most autoimmune diseases (other than SLE) do not have a peak incidence in women during reproductive years, but rather occur with increasing frequency in later years of life. Furthermore, human studies have generally not shown disease-altering effects with administration of sex steroids. Even in women with SLE oral contraceptive use did not associate with SLE flares.(Petri et al. 2005) Estrogen may instead be a permissive or exacerbating factor in selected diseases.

A. Rheumatoid Arthritis and the Changing Maternal “Self” Hypothesis

Among women with RA, 75% of pregnancies are accompanied by amelioration of signs and symptoms of RA with peak improvement in the second or third trimester.(Hench 1938; Nelson and Ostensen 1997) The explanation for disease remission or improvement during pregnancy remains unknown. Disease returns postpartum, most often within 3 months of delivery. Overall, RA is a relatively common autoimmune disorder with a prevalence of 1% in the U.S. population and is more common in women than men with a ratio of 3:1. The hallmark feature is symmetrical inflammatory arthritis that causes pain, stiffness, swelling, and limited function of multiple joints. RA probably does not affect fertility, although a decrease in fecundity prior to disease onset (time interval to conception) has been described.(Nelson et al. 1993a) There is no evidence that RA increases risk of spontaneous abortions, preterm labor or preeclampsia.(Branch and Porter 1999; Nelson and Ostensen 1997)

Plasma cortisol, which rises during pregnancy to peak at term, was initially thought to be important in the pregnancy-induced amelioration of RA.(Hench 1938) However, subsequent studies found no correlation between changes in cortisol concentrations and RA activity during pregnancy.(Ostensen 2000) Support for a disease-modulating role of estrogen has not been found, and a double-blind crossover trial found that estrogen did not benefit RA.(Bijlsma et al. 1987) Earlier studies suggested that proteins circulating in higher concentrations during pregnancy might be associated with improvement of RA (e.g. α-2 pregnancy-associated globulin, placental gamma globulins). More recent studies highlighted the potential importance of immunologic changes unique to pregnancy since the mother is exposed to paternal gene products from the fetus genetically foreign to her. Amelioration of RA was found to occur significantly more often in women with RA who were carrying a fetus with different paternally inherited HLA class II antigens from those of the mother’s.(Nelson et al. 1993b) Thus, the maternal immune response to paternal HLA antigens may play a role in the pregnancy-induced remission of RA.

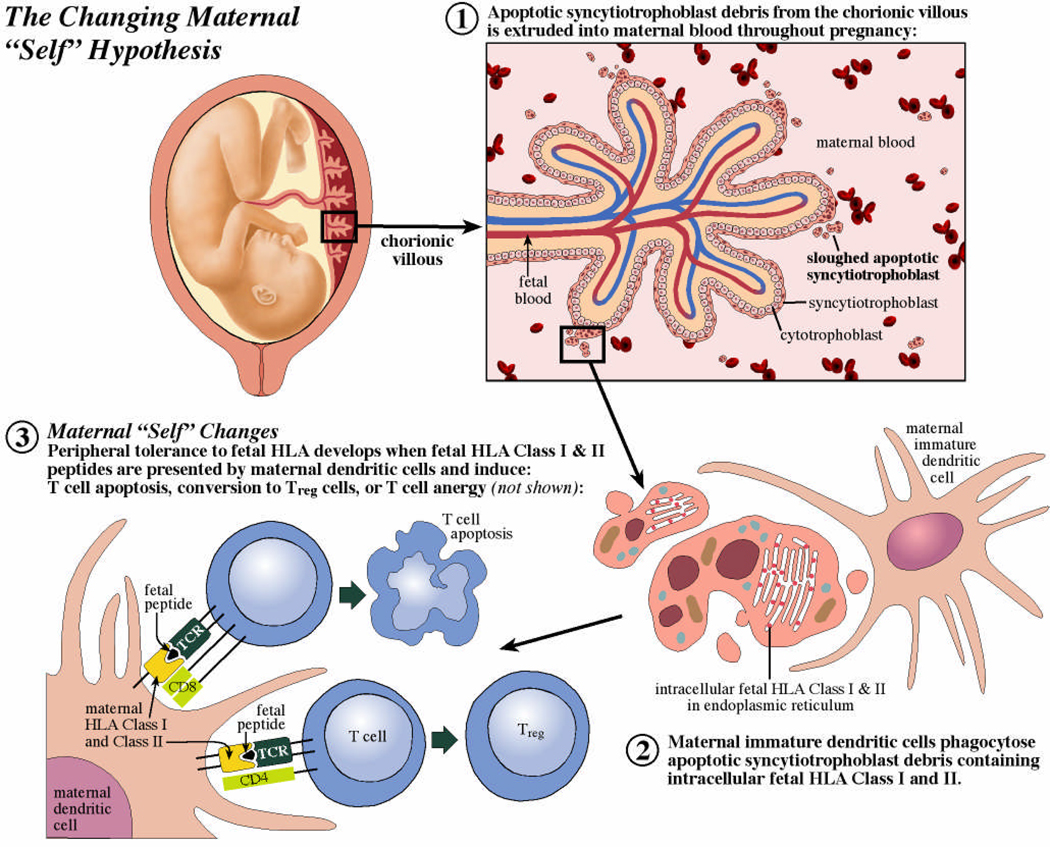

We recently proposed that amelioration of RA during pregnancy is a secondary benefit from normal changes in maternal T and B cell responses to fetal HLA that occur during pregnancy (Figure 1).(Adams et al. 2007) These changes in maternal systemic immune responses are placenta induced and result in a temporary change in what the mother’s immune system considers “self” as tolerance develops to fetal HLA peptides. According to the hypothesis the first event is the continuous shedding of apoptotic syncytiotrophoblast (outer epithelial lining of chorionic villi) into maternal blood. This begins early in pregnancy and by the third trimester results in release of gram quantities of apoptotic syncytiotrophoblast debris into maternal blood on a daily basis.(Huppertz et al. 2002) Phagocytosis of apoptotic synctiotrophoblast debris by maternal antigen presenting cells would be expected to result in the internalization and presentation of intracellular trophoblast peptides. While expression of classical HLA Class II molecules has not been found on the cell surface of normal trophoblast some work has described intracellular fetal DRβ that is retained within the endoplasmic reticulum of human villous trophoblast.(Ranella et al. 2005) This intracellular DRβ could be the source for soluble HLA-DR which has been found in maternal plasma and increases as gestation progresses.(Steinborn et al. 2003) Alternatively, fetal cells trafficking into the maternal circulation could provide a source of fetal HLA Class II.(Adams and Nelson 2004) After taking up antigens derived from apoptotic trophoblast or other fetal cells, immature dendritic cells (DC) induce peripheral T cell tolerance through T cell deletion, anergy, or induction of T regulatory cells (TREG).(Morelli and Thomson 2007) As peptides from apoptotic cells may be presented on HLA Class I or II, both CD8+ and CD4+ T cells may be silenced by this mechanism. Amelioration of RA may occur as a secondary benefit due to the simultaneous presentation of fetal and self (RA-associated) HLA peptides by tolerogenic dendritic cells and the ensuing (temporary) alteration of maternal T cell immunoreactivity.

Figure 1.

A mechanistic hypothesis to explain the classic amelioration of RA during pregnancy. The routine sloughing of apoptotic syncytiotrophoblast debris from the placental chorionic villous (step 1) provides a source of intracellular fetal HLA peptides that may be phagocytosed by maternal immature dendritic cells (step 2). Peripheral T cell tolerance may then develop as fetal HLA peptides are presented in the context of tolerogenic signals by maternal dendritic cells (step 3).

Several lines of evidence support the hypothesis. Murine studies suggest that maternal T cell responses are specifically altered by pregnancy to accommodate the developing fetus. These maternal T cells acquire a transient state of tolerance for fetal H-2 antigens (mouse equivalent of HLA) despite being sensitized to the same fetal (paternal) antigen before pregnancy.(Jiang and Vacchio 1998; Tafuri et al. 1995) The idea that a small number of foreign cells can alter a host’s T cell repertoire is also supported by studies from transplantation; a small number of donor cells from a transplanted organ were able to maintain deletion of the donor cell-specific CD8+ T cell repertoire after discontinuation of immunosuppression.(Bonilla et al. 2006) A greater likelihood of RA amelioration has been described in association with fetal-maternal HLA class II disparity, which is consistent with the hypothesis, because tolerogenic effects of fetal HLA peptides would be more likely with fetal-maternal HLA-disparity (e.g. regulatory T cell production).(Nelson et al. 1993b) Finally, we recently identified a significant correlation between levels of serum fetal DNA (trophoblast derived) and dynamic changes in RA activity during pregnancy.(Yan et al. 2006)

B. Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

In contrast to RA, disease course of SLE is less predictable during pregnancy with prospective studies suggesting that pregnancy confers either no benefit or results in a modestly increased risk of a SLE exacerbation.(Petri et al. 1991; Ruiz-Irastorza et al. 1996) SLE may be viewed as a prototypical autoimmune rheumatic disease in that there is a diverse set of clinical and laboratory manifestations associated with complex immunologic abnormalities. The presentation of SLE is highly variable, but migratory arthralgias and fatigue are the most prominent presenting symptoms. SLE diagnosis requires meeting at least 4 out of 11 possible criteria, therefore, the diagnosis in two individuals may be based on a completely different set of symptoms. As one might expect, the immunologic defects associated with SLE are also heterogeneous and include abnormalities in B cell activation, longevity, and tolerance.(Anolik 2007) Reported frequencies of SLE exacerbations during pregnancy or postpartum are 15 – 60% and are usually controlled with low or moderate doses of glucocorticoids. However, several complications of pregnancy are more frequent in women with SLE than healthy women and include spontaneous abortion(Branch and Porter 1999; Petri and Allbritton 1993), intrauterine fetal death(Branch and Porter 1999) (associated with antiphospholipid antibodies), intrauterine fetal growth restriction(Johnson et al. 1995) (20–30% incidence), preterm birth and premature rupture of membranes, and preeclampsia(Johnson et al. 1995) (30% incidence). Distinguishing between an SLE exacerbation with active nephritis and preeclampsia may be difficult or impossible, as each may present with proteinuria, hypertension and multi-organ dysfunction. Elevated anti-dsDNA levels suggest active SLE. Normal or slightly elevated levels of C3 and C4 (complement components) suggest preeclampsia. Decreased C3 and C4 are less helpful since complement activation may occur in both SLE and preeclampsia.

C. Autoimmune Thyroiditis

Autoimmune thyroiditis represents the most common cause of hypothyroidism (Hashimoto’s thyroiditis) and hyperthyroidism (Graves’ disease). While autoimmune thyroiditis can present for the first time during pregnancy, the incidence of disease onset is especially increased postpartum. For women who have autoimmune thyroiditis before conceiving, pregnancy is generally not associated with disease improvement or exacerbation. Thyrotoxicosis occurs in 0.2% of all pregnancies and Graves’ disease is the most common cause.(Rashid and Rashid 2007) Graves’ disease is caused by thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) antibodies binding to TSH receptors and inducing excess production of thyroid hormone; CD4 T cells likely drive this reaction by recognizing TSH peptides and in turn activating B cells, which produce the autoantibody. Graves’ disease is classically associated with a triad of diffuse goiter, hyperthyroidism, and extrathyroidal manifestations [i.e. dermopathy (pre-tibial myxedema), ophthalmopathy]. Uncontrolled disease is associated with an increased incidence of neonatal morbidity resulting from preterm birth and low birth weight. Transplacental transfer of maternal stimulatory anti-TSH receptor antibodies results in neonatal hyperthyroidism in 1% of the infants born to mothers with Graves’ disease. Typically, the disease resolves with loss of maternal antibodies in the first four months of life, but if untreated may lead to death.(Chan and Mandel 2007; Zimmerman 1999) In addition to stimulatory antibodies, women with Graves’ may produce antibodies antagonistic to the TSH receptor and the ratio of stimulatory to antagonistic TSH receptor antibodies may change during pregnancy. In a study of pregnant women, the stimulatory activity of anti-TSH-receptor antibody specificity was lost over time, with antibody specificity becoming predominantly that of TSH receptor blockade.(Kung et al. 2001) Thus, the developing fetus may be at risk for both neonatal hyper- or hypothyroidism.

Approximately 4–9% of all pregnant women develop postpartum painless thyroiditis, an autoimmune thyroiditis presenting as either hyper- or hypothyroidism in the postpartum period.(Lazarus et al. 2002) The diagnosis is made by finding the new-onset of abnormal levels of TSH and free T4 and is supported by the presence of anti-TPO autoantibodies (previously called antimicrosomal antibodies). Nearly 50% of women found to have anti-TPO antibodies at 16 weeks’ gestation will develop postpartum thyroiditis, which may be mediated through complement activation by autoantibodies.(Kuijpens et al. 1998) Although the clinical presentation is variable, nearly half present with hypothyroidism and a significant minority develop a transient thyrotoxicosis followed by hypothyroidism. Approximately 11% of women with postpartum thyroiditis may remain persistently hypothyroid with high levels of TSH and anti-TPO antibodies predicting this subgroup.(Lucas et al. 2000) The reason for a surge in autoimmune thyroiditis postpartum is unknown.

LONG-TERM PERSISTENCE OF NATURALLY ACQUIRED MICROCHIMERISM AND AUTOIMMUNE DISEASE

Bi-directional trafficking of maternal and fetal cells is now known to occur routinely during pregnancy with persistence of low levels of fetal cells in the mother and maternal cells in her offspring for decades after childbirth.(Bianchi et al. 1996; Lo et al. 2000; Maloney et al. 1999; Nelson 2008) Microchimerism (Mc) refers to a small population of cells or DNA in one individual that derives from a genetically distinct individual. The extent to which Mc is tolerated and whether dynamic changes occur over time are unknown, but observations from multiple disciplines implicate Mc in autoimmune disease pathogenesis decades after childbirth. Additional sources of Mc include transplantation, blood transfusion or from cell transfer between twins in utero.(Adams and Nelson 2004) It is not yet understood how Mc is tolerated by the immune system and whether recognition of these foreign cells might result in an “auto”-immune disease. The concept that Mc might contribute to autoimmune disease arose in part from observations of iatrogenic chimerism after transplantation.(Nelson 1996) Chronic graft-versus-host-disease (GVHD), a condition in which donor cells attack the transplant recipient, shares many clinical similarities with autoimmune diseases including systemic sclerosis, primary biliary cirrhosis, Sjögren’s syndrome, myositis and systemic lupus erythematosus. Autoimmune diseases are also more common in women, especially in post-childbearing years. The hypothesis that Mc might induce autoimmune disease also involved HLA relationships between donor (fetal) and host (maternal) cells, because the donor-recipient HLA relationship was a known critical component of both chronic GVHD and graft rejection.(Nelson 1996)

Mechanisms involved in Mc and the pathogenesis of autoimmune disease are unknown and there are a number of possibilities. Microchimeric cells could potentially function as effector cells or as targets of an immune response. Other investigators have reported reactivity of male T cell clones (presumed to be fetal Mc) that were obtained from mothers (with sons) to the non-shared maternal HLA antigens.(Scaletti et al. 2002) Another way in which Mc could contribute to autoimmunity is through presentation of peptides from the Mc (e.g., peptides derived from the fetal paternally-transmitted HLA) by one host cell to another host cell; this mechanism is analogous to the “indirect” pathway of recognition, thought to play a role in chronic rejection of organ grafts. An excess HLA similarity of fetal to maternal cells without complete HLA-identity could hamper recognition of cells as foreign. Autoimmunity might be induced in this manner by simultaneous presentation of peptides derived from HLA that are similar and dissimilar to self. Thus, Mc could have adverse, neutral (or beneficial) effects on the host, depending upon particular HLA genes involved and the HLA-relationship between the different cell populations.

A. Fetal Microchimerism in Systemic Sclerosis and Autoimmune Thyroiditis

Initial studies of fetal Mc in autoimmune disease focused on systemic sclerosis, a disease with clinical resemblance to chronic GVHD. The first report was a prospective blinded study quantitating male DNA in women with systemic sclerosis and healthy women who had given birth to at least one son.(Nelson et al. 1998) Women with systemic sclerosis had significantly higher levels of male DNA than controls. Although the women had given birth to their sons decades previously, strikingly high levels of male DNA in some women with systemic sclerosis corresponded to the highest quartile of fetal Mc when measured in healthy women who were pregnant with a normal male fetus. Particular HLA genes and HLA-relationships between host and microchimeric cell populations are likely key determinants of the effect of Mc on the host. Interestingly, an increased risk of subsequent systemic sclerosis in the mother was observed when a previously born child was not distinguishable from the mother’s perspective for genes encoding the HLA-DR molecule (HLA class II gene).(Lambert et al. 2002)

Several studies have linked fetal Mc with autoimmune thyroid disease, which occurs frequently in women, particularly postpartum.(Davies 1999) Greater frequency of male DNA has been found in thyroid tissue of women with Hashimoto's disease compared to nodular goiter and also in Graves’ disease compared to controls with adenoma.(Davies 1999),(Ando et al. 2002; Klintschar et al. 2001) Recently, using a quantitative PCR assay, fetal Mc was detected in 8 of 21 thyroid samples from women with Hashimoto’s disease compared to 0 of 17 healthy thyroid glands.(Ando et al. 2002; Klintschar et al. 2001; Klintschar et al. 2006) In thyroidectomy and autopsy specimens from women with multiple thyroid disorders, male cells were found using fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) in thyroids from more than half of women with a thyroid disease compared to none in autopsy controls.(Klintschar et al. 2006) A large community-based study showed no association between parity and presence of thyroid antibodies or thyroid dysfunction and suggested a lesser role for fetal Mc in autoimmune thyroid disease.(Walsh et al. 2005) However, the number of pregnancies may be a less important risk factor than HLA relationships between fetal and maternal cells, as suggested by studies in systemic sclerosis.

B. Maternal Microchimerism in Type I Diabetes Mellitus and Neonatal Lupus Syndrome

Maternal cells have recently been found in the circulation and tissues of her immune competent children, including in adult life, and is referred to as maternal Mc. Whether maternal Mc confers benefits during development or later in life or sometimes has adverse effects is not yet known. Type 1 diabetes (T1D) is an autoimmune disease that primarily affects children and young adults. We assayed maternal Mc in DNA extracted from whole blood in patients with T1D, their unaffected siblings and unrelated healthy controls. The approach used was to target non-transmitted, non-shared maternal-specific HLA alleles employing a panel of quantitative PCR assays developed for this purpose. Maternal Mc levels were significantly higher in T1D patients than in unaffected siblings and healthy subjects.(Nelson et al. 2007) The difference between groups was evident irrespective of the subject’s HLA-genotype. We also studied the pancreas from a male T1D patient and three other males for female cells (presumed maternal Mc) employing fluorescence in situ hybridization for X- and Y-chromosomes. Concomitant staining was used for hematopoietic cells (CD45) and for islet β cells (insulin) to identify cell phenotype. Maternal Mc was found in the pancreas and consisted primarily of islet β cells whereas female hematopoietic cells were very rare. While it is possible that maternal islet β cells could be targets for autoimmunity the more likely interpretation of these findings is that maternal Mc contributes to islet β cell regeneration or possibly contributes to development/differentiation in the pancreas.

Maternal Mc has also been linked to neonatal lupus syndrome (NLS), a rare autoimmune condition of the fetus and neonate characterized by dermatological, cardiac and/or hematological abnormalities. The cause of NLS is unknown, but is associated with maternal autoantibodies that are thought to cross the placenta and cause fetal disease, possibly in combination with fetal pro-inflammatory factors. The most serious manifestation, congenital complete heart block may result when maternal autoantibodies (anti-SS-A/Ro and anti-SS-B/La) bind to fetal cardiac antigens.(Buyon et al. 1993) Based on experimental studies in which SLE is induced by administration of parental cells into the progeny, a potential role for maternal Mc in NLS is suggested. Maternal cells were recently detected in the hearts of male infants with NLS who died from congenital heart block.(Stevens AM 2003) A technique of combined immunohistochemistry for myocardial-specific cell markers and FISH for X- and Y-chromosomes in the same tissue section revealed that these maternal cells were cardiac myocytes. This result suggests the interesting possibility that maternal Mc could become the target of a host immune process causing fibrosis of the conduction system and eventual heart block. Alternatively, transdifferentiation of maternal Mc could contribute to tissue repair and benefit the host. The biology of Mc cell populations remains poorly understood, but the possible propensity for these cells to take either an active role in disease processes or wound repair merits further investigation.

SUMMARY

In some cases, pregnancy may have a profound effect upon the symptoms of autoimmune disease, such as in the case of RA and multiple sclerosis. The pregnancy-induced amelioration of select autoimmune diseases presents a unique opportunity to garner insight into both the maternal-fetal tolerance of pregnancy and pathogenic mechanisms in autoimmunity. We hypothesize that amelioration of RA results from changes in maternal peripheral tolerance, which occur by the simultaneous presentation of fetal and self (RA-associated) HLA peptides by tolerogenic dendritic cells. The mother’s immune system may temporarily alter its definition of “self” during pregnancy as tolerance develops to fetal HLA peptides with improvement of RA and some other autoimmune diseases as a secondary benefit. Alternatively, pregnancy may have no effect upon the mother’s symptoms, but instead target the developing fetus due to the placental transfer of maternal autoantibodies (e.g. Graves’ disease). The unique immunologic defects characteristic of each autoimmune disease are key to understanding the effect of pregnancy upon the mother’s disease course and her fetus.

Discovery of persistent fetal and maternal Mc decades after delivery has profound implications for autoimmunity, transplantation, and how we distinguish our own cells from “danger” signals (e.g. pathogens). The impact of Mc on the host is only beginning to be understood, but it is anticipated that effects of Mc are pleiotropic and range from adverse to neutral or even beneficial for the host, depending upon other factors with HLA genes and the HLA relationship among cells of key importance. Fetal Mc and HLA relationships between the fetal and mother’s cells have been studied in a number of autoimmune diseases with strongest evidence implicating fetal Mc in systemic sclerosis and autoimmune thyroiditis. Maternal Mc has also been associated with autoimmune diseases in the neonate and early childhood such as NLS and T1D. Elucidating mechanisms by which naturally acquired Mc is permitted without detriment to the host may lead to novel strategies with application to prevention and treatment of autoimmune diseases.

Acknowledgment

We are grateful to Jan Hamanishi for graphic design. This work was supported by NIH grants AI-067910 (KAW), AI-45659 and AI-41721 (JLN).

Abbreviations

- DC

dendritic cells

- FISH

fluorescence in situ hybridization

- HLA

Human Leukocyte Antigens

- Mc

Microchimerism

- RA

Rheumatoid arthritis

- SLE

Systemic lupus erythematosus

- TREG

T regulatory cells

- TSH

Thyroid stimulating hormone

- T1D

Type I diabetes mellitus

References

- Adams KM, Nelson JL. Microchimerism: an investigative frontier in autoimmunity and transplantation. Jama. 2004;291(9):1127–1131. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.9.1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams KM, et al. The changing maternal "self" hypothesis: a mechanism for maternal tolerance of the fetus. Placenta. 2007;28(5–6):378–382. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2006.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ando T, et al. Intrathyroidal fetal microchimerism in Graves' disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87(7):3315–3320. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.7.8656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anolik JH. B cell biology and dysfunction in SLE. Bull NYU Hosp Jt Dis. 2007;65(3):182–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi DW, et al. Male fetal progenitor cells persist in maternal blood for as long as 27 years postpartum. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93(2):705–708. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.2.705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bijlsma JW, Huber-Bruning O, Thijssen JH. Effect of oestrogen treatment on clinical and laboratory manifestations of rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1987;46(10):777–779. doi: 10.1136/ard.46.10.777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonilla WV, et al. Microchimerism maintains deletion of the donor cell-specific CD8+ T cell repertoire. J Clin Invest. 2006;116(1):156–162. doi: 10.1172/JCI26565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branch DW, Porter TF. Autoimmune disease. In: Steer PJ, James DK, Weiner CP, Gonik B, editors. High-risk pregnancy management options. 2nd edn. 1999. pp. 853–854. [Google Scholar]

- Buyon JP, et al. Identification of mothers at risk for congenital heart block and other neonatal lupus syndromes in their children. Comparison of enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and immunoblot for measurement of anti-SS-A/Ro and anti-SS-B/La antibodies. Arthritis Rheum. 1993;36(9):1263–1273. doi: 10.1002/art.1780360911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan GW, Mandel SJ. Therapy insight: management of Graves' disease during pregnancy. Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab. 2007;3(6):470–478. doi: 10.1038/ncpendmet0508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costenbader KH, et al. Reproductive and menopausal factors and risk of systemic lupus erythematosus in women. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(4):1251–1262. doi: 10.1002/art.22510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies TF. The thyroid immunology of the postpartum period. Thyroid. 1999;9(7):675–684. doi: 10.1089/thy.1999.9.675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregersen PK, Silver J, Winchester RJ. The shared epitope hypothesis. An approach to understanding the molecular genetics of susceptibility to rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1987;30(11):1205–1213. doi: 10.1002/art.1780301102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hench PS. The ameliorating effect of pregnancy on chronic atrophic (infectious rheumatoid) arthritis, fibrositis, and intermittent hydrarthrosis. Mayo Clin Proc. 1938;13:161–167. [Google Scholar]

- Huppertz B, Kaufmann P, Kingdom J. Trophoblast turnover in health and disease. Fetal Maternal Med Rev. 2002;13:103–118. [Google Scholar]

- Jacob CO, et al. Heritable major histocompatibility complex class II-associated differences in production of tumor necrosis factor alpha: relevance to genetic predisposition to systemic lupus erythematosus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87(3):1233–1237. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.3.1233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang SP, Vacchio MS. Multiple mechanisms of peripheral T cell tolerance to the fetal "allograft". J Immunol. 1998;160(7):3086–3090. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MJ, et al. Evaluation of preterm delivery in a systemic lupus erythematosus pregnancy clinic. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;86(3):396–399. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(95)00186-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klintschar M, et al. Evidence of fetal microchimerism in Hashimoto's thyroiditis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86(6):2494–2498. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.6.7540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klintschar M. Fetal microchimerism in Hashimoto's thyroiditis: a quantitative approach. Eur J Endocrinol. 2006;154(2):237–241. doi: 10.1530/eje.1.02080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuijpens JL, et al. Prediction of post partum thyroid dysfunction: can it be improved? Eur J Endocrinol. 1998;139(1):36–43. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1390036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kung AW, Lau KS, Kohn LD. Epitope mapping of tsh receptor-blocking antibodies in Graves' disease that appear during pregnancy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86(8):3647–3653. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.8.7704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert NC, et al. Male microchimerism in healthy women and women with scleroderma: cells or circulating DNA? A quantitative answer. Blood. 2002;100(8):2845–2851. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-01-0295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus JH, Parkes AB, Premawardhana LD. Postpartum thyroiditis. Autoimmunity. 2002;35(3):169–173. doi: 10.1080/08916930290031667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo YM, et al. Quantitative analysis of the bidirectional fetomaternal transfer of nucleated cells and plasma DNA. Clin Chem. 2000;46(9):1301–1309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas A, et al. Postpartum thyroiditis: epidemiology and clinical evolution in a nonselected population. Thyroid. 2000;10(1):71–77. doi: 10.1089/thy.2000.10.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maloney S, et al. Microchimerism of maternal origin persists into adult life. J Clin Invest. 1999;104(1):41–47. doi: 10.1172/JCI6611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morelli AE, Thomson AW. Tolerogenic dendritic cells and the quest for transplant tolerance. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7(8):610–621. doi: 10.1038/nri2132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson JL. Maternal-fetal immunology and autoimmune disease: is some autoimmune disease auto-alloimmune or allo-autoimmune? Arthritis Rheum. 1996;39(2):191–194. doi: 10.1002/art.1780390203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson JL. Your cells are my cells. Scientific American. 2008;298(2):72–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson JL, Ostensen M. Pregnancy and rheumatoid arthritis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 1997;23(1):195–212. doi: 10.1016/s0889-857x(05)70323-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson JL, et al. Fecundity before disease onset in women with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1993a;36(1):7–14. doi: 10.1002/art.1780360103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson JL, et al. Maternal-fetal disparity in HLA class II alloantigens and the pregnancy-induced amelioration of rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 1993b;329(7):466–471. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199308123290704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson JL, et al. Microchimerism and HLA-compatible relationships of pregnancy in scleroderma. Lancet. 1998;351(9102):559–562. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)08357-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson JL, et al. Maternal microchimerism in peripheral blood in type 1 diabetes and pancreatic islet beta cell microchimerism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(5):1637–1642. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606169104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostensen M. Glucocorticosteroids in pregnant patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Z Rheumatol. 2000;59 Suppl 2:II/70–II/74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petri M, Allbritton J. Fetal outcome of lupus pregnancy: a retrospective case-control study of the Hopkins Lupus Cohort. J Rheumatol. 1993;20(4):650–656. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petri M, Howard D, Repke J. Frequency of lupus flare in pregnancy. The Hopkins Lupus Pregnancy Center experience. Arthritis Rheum. 1991;34(12):1538–1545. doi: 10.1002/art.1780341210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petri M, et al. Combined oral contraceptives in women with systemic lupus erythematosus. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(24):2550–2558. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranella A, et al. Constitutive intracellular expression of human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-DO and HLA-DR but not HLA-DM in trophoblast cells. Hum Immunol. 2005;66(1):43–55. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2004.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rashid M, Rashid MH. Obstetric management of thyroid disease. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2007;62(10):680–688. doi: 10.1097/01.ogx.0000281558.59184.b5. quiz 91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Irastorza G, et al. Increased rate of lupus flare during pregnancy and the puerperium: a prospective study of 78 pregnancies. Br J Rheumatol. 1996;35(2):133–138. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/35.2.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Guerrero J, et al. Postmenopausal estrogen therapy and the risk for developing systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann Intern Med. 1995;122(6):430–433. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-122-6-199503150-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Guerrero J, et al. Past use of oral contraceptives and the risk of developing systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40(5):804–808. doi: 10.1002/art.1780400505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scaletti C, et al. Th2-oriented profile of male offspring T cells present in women with systemic sclerosis and reactive with maternal major histocompatibility complex antigens. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46(2):445–450. doi: 10.1002/art.10049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinborn A, et al. Soluble HLA-DR levels in the maternal circulation of normal and pathologic pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188(2):473–479. doi: 10.1067/mob.2003.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens AM, Hermes H, Rutledge R, Buyon J, Nelson JL. Maternal microchimerism has myocardial tissue-specific phenotype in neonatal lupus congenital heart block. Lancet. 2003 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14795-2. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tafuri A, et al. T cell awareness of paternal alloantigens during pregnancy. Science. 1995;270(5236):630–633. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5236.630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vyse TJ, Kotzin BL. Genetic susceptibility to systemic lupus erythematosus. Annu Rev Immunol. 1998;16:261–292. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.16.1.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh JP, et al. Parity and the risk of autoimmune thyroid disease: a community-based study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90(9):5309–5312. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-0771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weetman AP, McGregor AM. Autoimmune thyroid disease: further developments in our understanding. Endocr Rev. 1994;15(6):788–830. doi: 10.1210/edrv-15-6-788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong GW, Cheng SH, Dorman JS. The HLA-DQ associations with Graves' disease in Chinese children. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 1999;50(4):493–495. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.1999.00661.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan Z, et al. Prospective study of fetal DNA in serum and disease activity during pregnancy in women with inflammatory arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(7):2069–2073. doi: 10.1002/art.21966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman D. Fetal and neonatal hyperthyroidism. Thyroid. 1999;9(7):727–733. doi: 10.1089/thy.1999.9.727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]