Abstract

Osteoclasts arise by proliferation, differentiation, and subsequent fusion of marrow-derived precursors, all processes requiring attachment to matrix. Integrins are important mediators of cell-matrix recognition and bone is rich in proteins containing the Arg-Gly-Asp motif, recognized primarily by αv integrins. Thus, we determined if avian osteoclast precursors express integrins capable of mediating initial attachment to matrix proteins. Early, marrow-derived osteoclast precursors, when first isolated, contain no detectable αvβ3, but express an αv integrin with an 80 kDa associated β subunit. Immunoprecipitation with an antibody raised against the conserved β5 cytoplasmic tail sequence indicates the the αv associated the integrin is αvβ5. Retinoic acid is a resorptive steroid, and its exposure to early osteoclast precursors prompts a time- and dose-dependent decrease in αvβ5 expression, while simultaneously stimulating αvβ3 expression. Northern analysis reveals that retinoic acid decreases β5 steady- state mRNA, nontranscriptionally, without altering that of αv. The finding αvβ5 expression decreases under the influence of retinoic acid, an osteoclastogenic steroid, while those of αvβ3 rise, suggests that these closely related integrins play separate and complementary roles during osteoclast differentiation.

INTRODUCTION

The Osteoclast is a multinucleated bone-resorbing cell generated by fusion of mononuclear precursors, which are members of the monocyte/macrophage family.(1,2) These precursors arise from hematopoietic stem cells which differentiate under the influence of various cytokines and steroid hormones.(1,3,4) We have shown, in an avian osteo-clast-generating system,(5) that surface expression of the functional osteoclast integrin αvβ3 is regulated by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3(1,25(OH)2D3), (6–8) a hormone stimulating maturation of osteoclast precursors.(4,9) Induction of the integrin by the steroid involves transactivation of both the αv (8) and β3 (7) genes, thereby precluding determination of which subunit is rate limiting for αv β3 expression.

Like 1,25(OH)2D3, retinoic acid, another member of the steroid superfamily,(10) stimulates bone resorption in vivo(11) and in vitro.(3,4,12,13) Furthermore, the retinoid and secosteroid share similarity in their mode of action. Thus, they bind to specific receptors, the vitamin D receptor and retinoic acid receptor, respectively, forming heterodimers with the retinoid X receptor (RXR).(14–16) The heterodimers, once bound to DNA sequences in the regulatory regions of target genes, act as transcriptional regulators.(15,16) Based on this information, we postulated that retinoic acid may also increase αvβ3, and find this to be the case. Moreover, the retinoid, like the vitamin D metabolite, transactivates the avian β3 gene, but, in contrast to 1,25(OH)2D3, does so without altering αv transcription, indicating that at least in the case of retinoic acid, αvβ3 expression is regulated by the β subunit.

The integrin αvβ5, like αvβ3, recognizes the Arg-Gly-Asp (RGD) amino acid motif.(17,18) Furthermore, human monocytes, cells ontogenetically related to osteoclast precursors, express αvβ5 and αvβ3 in a manner regulated by hematopoietic cytokines.(19,20) Because of the capacity of both αv integrins to ligand bone matrix proteins such as osteopontin,(18) we asked if avian osteoclast precursors also express the heterodimers αvβ3 and αvβ5 and, if so, whether expression of αvβ5 is regulated by 1,25(OH)2D3 and retinoic acid. We report here that freshly isolated avian osteoclast precursors contain αvβ5, but not αvβ3, and that retinoic acid decreases expression of the heterodimer by altering steady-state mRNA levels of the β5 but not the αv subunit. In contrast, 1,25(OH)2D3, a hormone that increases surface expression of αvβ3, fails to alter either β5 mRNA or expression of the αvβ5 complex. Most importantly, the fact that αvβ5 is present in freshly isolated precursors at a time when αvβ3 is not suggests that αvβ5 may play a role in matrix recognition by the early precursor cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell isolation and culture

Avian osteoclast precursors were isolated and cultured as described previously.(5,7) Briefly, bone marrow cells from laying hens maintained on a calcium-free diet for 2–3 weeks were fractionated on Ficoll-Hypaque (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, U.S.A.), and the mononuclear fraction was cultured overnight on Falcon (Lincoln Park, NJ, U.S.A.) plastic cell culture dishes. The nonadherent cells were reisolated and cultured for varying periods of time at 4–6 × 106 cells/ml in alpha modified essential medium/5% fetal bovine serum + 5% chicken serum, with the addition of 10−5to 10−8 M all-trans retinoic acid in ethanol (at a final concentration of < 0.1%). In specific experiments, cells from the same bird were treated with either 10−6 M all-trans retinoic acid or 10−8 M 1,25(OH)2D3 for 3 days. All sera used for culture had been charcoal-stripped to remove endogenous steroids.

Surface labeling and immunoprecipitation

Cells were labeled with either the water-soluble biotin reagent sulfosuccinimidobiotin (sulfo-NHS-biotin; Pierce Chemical Co., Rockford, IL, U.S.A.) or 125/I lactoperoxidase using minor modifications of published methods.(7,21) Briefly, for the nonradioactive procedure, adherent cells were rinsed free of culture medium with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and then labeled for 1 h at room temperature with the reagent at 0.2 mg/ml in 100 mM HEPES, pH 8.0. Following removal of the labeling solution, cells were lysed into buffer containing 10 mM Tris, pH 7.2, 150 mM NaCl, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% SDS, 0.025% NaN3, 5 mM iodoacetamide, 1 mM CaCl2,1 mM MgCl2, 4 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), and 0.25 TIU of Aprotinin/ml. The lysate was pre-cleared with protein G-Sepharose (Pharmacia, Piscataway, NJ, U.S.A.) and immunoprecipitated with suitable antibodies. These comprised either LM609, a monoclonal which recognizes the complex αvβ3,(7) or a rabbit polyclonal antibody raised against the sequence of the human β5 cytoplasmic tail.(22) The immune precipitates, recovered with excess protein G-Sepharose, washed prior to boiling with electrophoresis sample buffer, were subjected to SDS-PAGE in 6% nonreducing minigels. The separated proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose (Nitro ME; MSI, Westboro, MA, U.S.A.) with a semidry blotter, using the manufacturer’s instructions (BioRad, Richmond, CA, U.S.A.), and the blot was probed with 0.1% streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase (Boehringer-Mannheim, Indianapolis, IN, U.S.A.) in PBS, with color development with 4-chloronaphthol at 2 mg/ml. In the studies using radioisotope, 150-mm plates of adherent cells were labeled with 1 mCi of 125I, using the lactoperoxidase method as described.(21) Rinsed plate contents were lysed with a minimal volume of buffer, following which equal numbers of trichloracetic acid–precipitable counts were immunoprecipitated, as described above, with either LM609, the monoclonal αvβ3-specific antibody, or a rabbit polyclonal raised against the amino acid sequence of the human β3 cytoplasmic tail. (23) To detect all αv-associated integrins on the cell surface, lysates from radiolabeled cells were immunoprecipitated with Chav, a murine monoclonal which recognizes the avian αv subunit.(24,25) Analysis of all gels was performed by separation in nonreducing, 24 cm 6% SDS-PAGE gels, which were dried and exposed at −70°C to Kodak X-Omat film (Eastman Kodak, Rochester, NY, U.S.A.), prior to development.

Analysis of steady-state β3 and β5 mRNA levels

Osteoclast precursors were treated for varying periods of time with vehicle or 10−5 to 10−8 M all-trans retinoic acid without change of medium. At the relevant time, medium was removed, cells rinsed with PBS, and total RNA was isolated with RNAzol, according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Teltest, Friendswood, TX, U.S.A.). Equal amounts of RNA were treated with formaldehyde and separated on 1% agarose gels, followed by transfer to a nylon membrane (Hybond-N; Amersham, Arlington Heights, IL, U.S.A.) using a vacuum blotter. Full-length cDNAs for the avian β3 and β5 gene products, both cloned in our laboratory,(7,26) as well as a 2.2 kb fragment of the avian αv cDNA (27) were labeled by random priming and hybridized to filters overnight at 42°C in 5× SSPE, 5× Denhardt’s solution, 50% formamide, 0.1% SDS, and 10% background quencher (Teltest). The filters were washed three times at 55°C with 1× SSPE, 0.1% SDS, and exposed to film prior to development. In some experiments in which cells had been treated with retinoic acid, the membranes were stripped by boiling in 0.1% SDS in RNAse-free water, followed by washing in the same water. The membranes were then reprobed in the same manner with the avian αv cDNA probe.

Measurement of the rates of β5 and β3 mRNA synthesis

Nuclear run-on assays were performed as follows. Nuclei were isolated from cells treated with either vehicle or 10−6 M retinoic acid, using an established method.(21) Briefly, cells were lysed in 10 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 10 mM NaCl, 3 mM MgCl2, and 0.5% Nonidet P-40. Nuclei were isolated by centrifugation at 400 rpm and stored at −80°C at a concentration of 108 cells/ml in 50 mM HEPES, pH 8.0, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM DTT, 1 mg/ml of bovine serum albumin, and 25% glycerol. To measure new RNA synthesis ∼5 × 107 nuclei were thawed and mixed with an equal volume of 2× reaction buffer (100 mM HEPES, pH 8.0, 4 mM MgCl2, 6 mM MgOAc, 4 mM dithiothreitol, 2 mg/ml of bovine serum albumin, 300 mM NH4Cl, 1 mM each ATP, CTP, and GTP, 20% glycerol, and 100 μCi of 32P-UTP (3000 Ci/mmol; ICN, Costa Mesa, CA, U.S.A.). Incubation was carried out for 15 minutes at 37°C, following which total RNA was extracted as described above. Equal amounts of trichloracetic acid–precipitable counts were slot hybridized to a nitrocellulose membrane (Biodot; BioRad), to which 10 μg of linearized plasmid DNAs coding for avian β3 and β5 had been applied in 20× SSC. As controls, a cDNA coding for LEP, an avian lysosomal protein,(28) and plasmid DNA were applied in adjacent slots. The labeled RNA was hybridized at 55°C for 48 h in 5× SSC, 50% formamide, 2× Denhardt’s solution, 20 μg of tRNA, 50 mM NaH2PO4, 0,1% SDS, and 1× Background Quencher (Teltest). Membranes were subjected to three 5-minute washes at 45°C with 2× SSC, 0.1% SDS for 5 minutes followed by three 15-minute washes at 55°C with 0.2× SSC, 0.1% SDS. Membranes were dried, exposed at −70°C to Kodak Scientific Imaging film which was developed after appropriate times.

RESULTS

Freshly isolated avian osteoclast precursors express a novel αv integrin, but not αvβ3

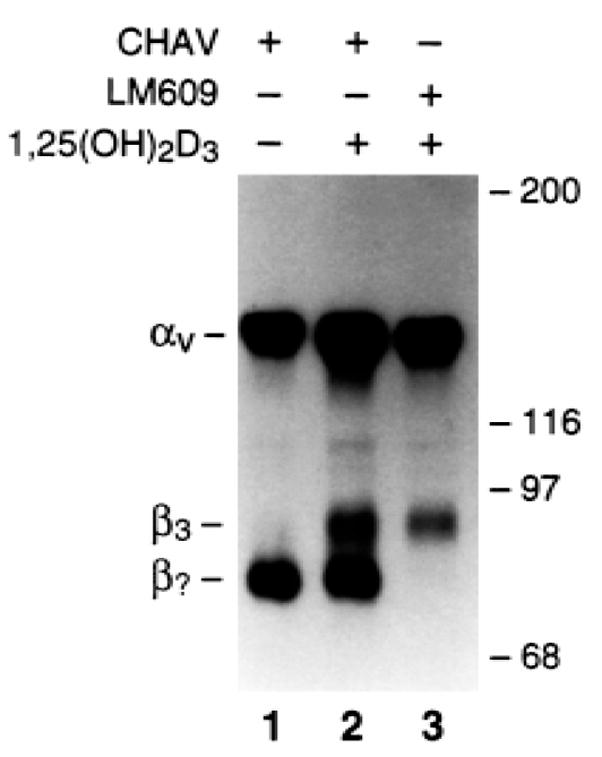

We find that mature avian osteoclasts express the integrin αvβ3, and this heterodimer plays an important role in their bone-resorptive capacity.(29) Having characterized the integrins on mature avian osteoclasts,(29) we turned to the αv-bearing integrins present on their precursors, which, to develop the osteoclast phenotype, must bind to bone. As seen in Fig. 1, osteoclast precursors analyzed with both the αvβ3-specific antibody LM609 and Chav, a monoclonal antibody (MAb) to the avian αv chain, express on their surface, a novel integrin, but not αvβ3. Of note, 1,25(OH)2D3 fails to alter expression of the novel integrin while having the expected effect(7,8) of increasing αvβ3.

FIG. 1.

Avian osteoclast precursors express a novel αv integrin. Freshly isolated precursor cells from the marrow of hens fed a calcium-deficient diet were grown in the absence (lane 1) or presence (lanes 2 and 3) of 10−8 M 1,25(OH)2D3. The expression of αv integrins was determined by 125I surface labeling followed by immunoprecipitation of lysates with LM609, an antibody specific for the αvβ3 complex, or Chav, a MAb recognizing all avian αv integrins. The integrin αvβ3, while absent in untreated cells (lane 1), is induced by 1,25(OH)2D3 (lane 2). Untreated cells contains another αv integrin whose levels are not altered by 1,25(OH)2D3 (lane 2). The size of the novel β chain (β?) is 80 kDa, smaller than that reported for members of this family of integrin subunits.

The novel integrin on avian osteoclast precursors is αvβ5

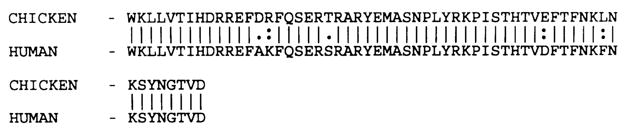

Based on the known association of αv with β5 in human monocytes,(19) and the fact that, like αvβ3, αvβ5 recognizes the RGD motif in several bone matrix proteins,(18) we postulated the unknown subunit associating with αv is the avian β5 homolog. The likelihood that this is so was supported by the finding that, using homology polymerase chain reaction, we obtained from the precursor cells, a cDNA highly homologous to that of human β5.(26) In particular, comparison of the amino acid sequence at the carboxyl terminus with that of human β5 (22) demonstrates almost complete identity (Fig. 2). Given this fact, we used a polyclonal antibody raised against the sequence of the human β5 cytoplasmic tail to ask if the novel integrin is αvβ5.

FIG. 2.

The amino acid sequence of the avian and human β5 cytoplasmic tails are homologous. A cDNA coding for the mature avian β5 protein was obtained by a combination of homology polymerase chain reaction and library screening. Translation of this cDNA provided the amino acid sequence of the protein, whose cytoplasmic tail (upper line) is compared with human β5 (lower line). The sequences are 96% similar and 92% identical.

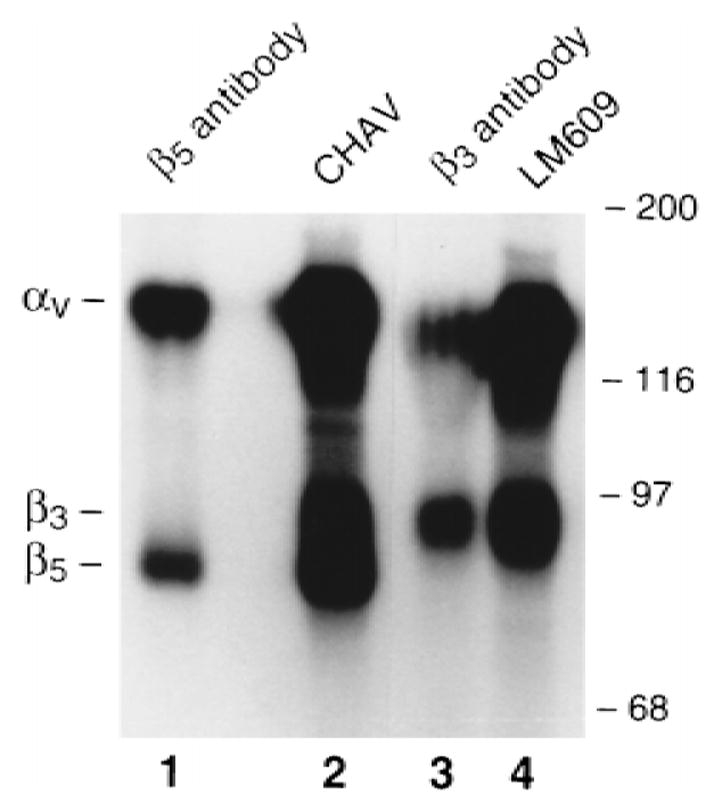

Osteoclast precursors treated with vehicle or 10−8 M 1,25(OH)2D3 were surface labeled with 125I, and the lysate was immunoprecipitated with either of two polyclonal antibodies, one of which is β5-specific and the second, raised against the sequence of the human β3 cytoplasmic tail. To confirm the complex precipitated by this latter polyclonal antibody is, in fact αvβ3, a portion of lysate was precipitated with the integrin-specific antibody LM609. To detect all αv-associated integrins on the cell surface, a final sample was precipitated with Chav mAb.

Given 1,25(OH)2D3 stimulates expression of αvβ3, (7) we anticipated this integrin would be present on cells exposed to the steroid. This expectation was confirmed by precipitation with both LM609 and the polyclonal anti-β3 cytoplasmic tail antibody (Fig. 3). Likewise, use of the β5-specific antibody results in only two bands, one migrating at 160 kDa, representing the αv subunit and the other at 80 kDa, confirming the novel integrin is αvβ5. In contrast, when Chav, capable of immunoprecipitating all β chains bound to αv, was the precipitating antibody, a complex of three bands, representing both αvβ3 and αvβ5, is obtained.

FIG. 3.

The integrin present on freshly isolated avian osteoclast precursors is αvβ5. Cells, isolated and treated with vehicle (lane 1) or 10−8 M 1,25(OH)2D3 (lanes 2–4), were surface labeled and immunoprecipitated with the following antibodies: a rabbit polyclonal antibody generated against the human β5 cytoplasmic tail (lane 1); Chav, a MAb recognizing all avian αv integrins (lane 2); a rabbit polyclonal antibody generated against the human β3 cytoplasmic tail (lane 3); and LM609, a MAb specific for the αvβ3 heterodimer (lane 4). Steroid-treated cells express both αvβ3 and a heterodimer recognized by the β5 tail antibody, while those cultured without 1,25(OH)2D3 αvβ5 have only on their surface.

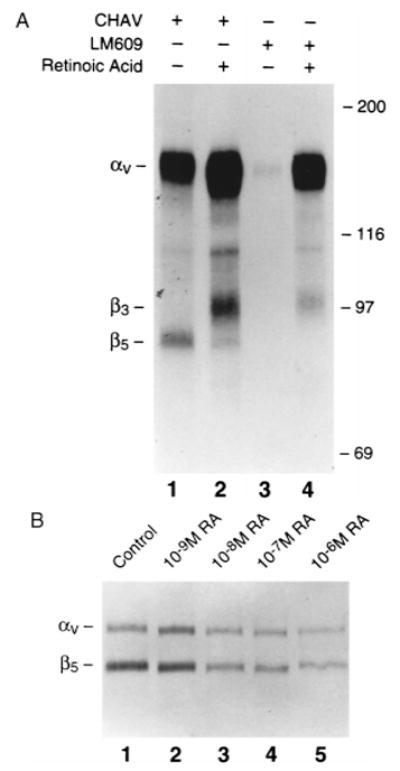

Retinoic acid decreases surface expression of αvβ5 by avian osteoclast precursors

1,25(OH)2D3 fails to alter surface expression, by osteoclast precursors, of αvβ5 (Fig. 1). Since both this steroid and retinoic acid increase αvβ3 expression, (21) we asked if the retinoid modulates αvβ5. As seen in Fig. 4A, which details expression of αv integrins by adherent osteoclast precursors treated with 10−6 M retinoic acid, the retinoid, decreases αvβ5 while increasing αvβ3. To determine if retinoic acid inhibition of αvβ5 expression is dose dependent, cells were surface labeled with a biotin derivative, a technique we previously validated for quantitating αv integrins. (21) This approach enabled us to study more variables than reasonable using iodination. As seen in Fig. 4B, αvβ5 expression is progressively decreased by increasing amounts of retinoic acid. The effect is detectable at concentrations of retinoid as low as 10−8 M, which is within the physiological range.(30)

FIG. 4.

(A) Retinoic acid reciprocally regulates αvβ3 and αvβ5 expression on avian osteoclast precursors. Cells were isolated from marrow and treated for 3 days with vehicle (lanes 1 and 3) or 10-6 M retinoic acid (lane 2 and 4). Integrin expression was determined on 125I surface-labeled cells using the antibodies Chav (all αv integrins) and LM609 (αvβ3 only). Retinoic acid, while stimulating αvβ3 expression (compare lanes 3 and 4), decreases that of αvβ5 (compare lanes 1 and 2). (B) The effect of retinoic acid on αvβ5 expression is dose dependent. Cells treated for 3 days with varying amounts of retinoic acid were surface labeled with sulfobiotin and immunoprecipitated with the β5-specific antibody.

Retinoic acid treatment of avian osteoclast precursors decreases steady-state β5 mRNA in a time- and dose-dependent manner, but fails to alter αv mRNA levels.

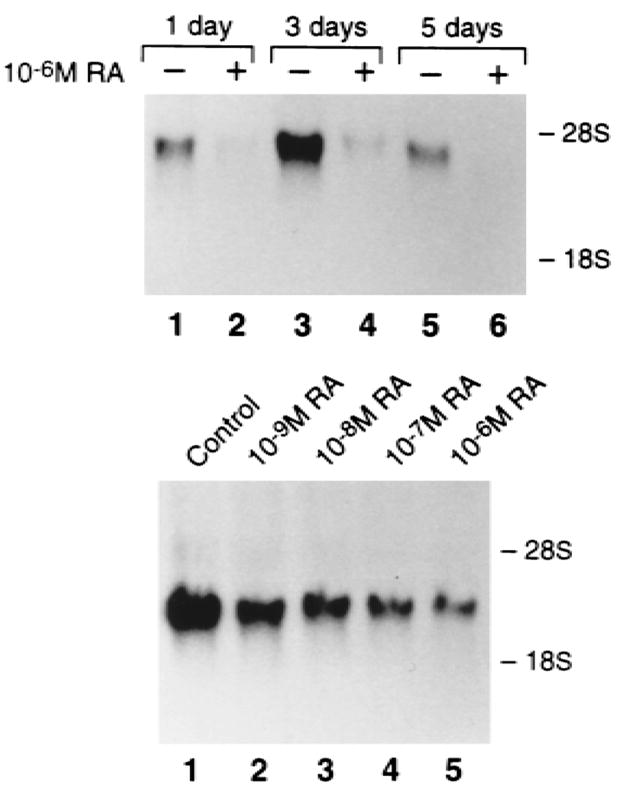

Retinoic acid–augmented surface expression of αvβ3 involves increased steady-state β3 integrin subunit mRNA.(21) To test if an analogous situation exists for αvβ5, we performed Northern analysis, with time, of cells treated with various concentrations of retinoic acid. The results of this experiment, shown in Fig. 5, demonstrate a dose-dependent decrease in steady-state mRNA under the β5 influence of the steroid with induction occurring within the physiological range. β5 mRNA, in untreated cells, is present at isolation, peaks at day 3 and returns to basal levels by day 5 (Fig. 5). Alternatively, 1 day of retinoic acid treatment blunts β5 mRNA expression. Northern analysis using a full-length avian cDNA reveals concentrations of retinoic acid as high as 10−6 M fail to alter αv mRNA levels (data not shown).

FIG. 5.

Retinoic acid alters αvβ5 expression by decreasing β5 steady-state mRNA levels, in a time- and dose-dependent manner. Cells were treated with vehicle or 10−6 M retinoic acid for up to 5 days (top panel) or for 3 days with vehicle (control) or varying amounts of retinoic acid (lower panel), at which time Northern analysis was performed.

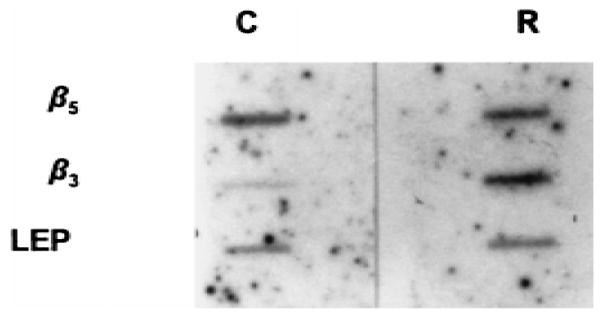

Retinoic acid fails to alter the rate of transcription of the avian β5 gene

To determine whether retinoic acid–mediated decrease in β5 mRNA arises from inhibited gene transcription, we performed run-on studies, using nuclei from cells treated with either vehicle or 10−6 M steroid. Retinoic acid, while transactivating the β3 gene as reported, fails to alter β5 transcription (Fig. 6). In these studies, transcription of LEP acts as a negative control.

FIG. 6.

Retinoic acid accelerates β3 but not β5 transcription. Nuclei isolated from cells treated with vehicle or 10−6 M retinoic acid were used in run-on studies, using excess β3, β5, and LEP (negative control) cDNA probes. C 4 control cells, R 4 retinoic acid-treated cells.

DISCUSSION

Our results indicate the integrin αvβ3, a critical mediator of osteoclast–bone interactions, is not expressed on early avian osteoclast precursors. However, precursor proliferation, maturation, and fusion, events central to osteoclastogenesis, require the cells to attach to the RGD-rich bone matrix. Thus, we asked whether another αv integrin is present on early precursors lacking αvβ3. Using a MAb recognizing the avian αv subunit, we established the presence, on these early cells, of an integrin whose β chain is smaller than that of avian β1 or β3, namely 105 kDa and 95 kDa, respectively.(21,31) These observations, plus the fact that neither an αvβ3-specific antibody, LM609, nor CSAT, an antibody targeting the avian β1 chain, recognize the 80 kDa–associated heterodimer (data not shown), suggest avian osteoclast precursors, express an αv integrin which is neither αvβ1 or αvβ3.

Given exclusion of αvβ1 and αvβ3, the remaining likely possibilities remained αvβ5, αvβ6, or αvβ8. While neither of the latter two integrins are known to be expressed by macrophages, αvβ5 is found on cells of monocyte lineage. (19,32) We confirmed the presence of this heterodimer on early osteoclast precursors by immunoprecipitation using an antibody prepared against the human β5 cytoplasmic tail sequence.

Having documented αvβ5 on osteoclast precursors, we turned to its regulation. We find that, unlike the case of αvβ3, 1,25(OH)2D3 fails to alter expression of αvβ5. In contrast, treatment of precursors cells with retinoic acid, a related osteoclastogenic steroid, prompts a time- and dose-dependent decrease in the integrin. Furthermore, as demonstrated previously,(21) in contrast to β3 mRNA, which is enhanced by retinoic acid, a maximal concentration of the steroid fails to alter the αv message, which is abundant in both treated and control cells.

Although exposure of cells to retinoic acid leads to diminished β5 steady-state mRNA, nuclear run-on studies indicate that the rate of transcription of the β5 gene is unaltered. This observation suggests that retinoic acid treatment results in destabilization of β5 mRNA. However, using the standard approach of measuring mRNA half-life with the transcriptional inhibitor actinomycin D, we were unable to confirm this hypothesis (data not shown). While the mechanism(s) by which retinoic acid decreases β5 mRNA remain to be elucidated, the possibility exists that treatment with the retinoid leads to a block in transcriptional elongation. A similar finding was reported with respect to c-myc in the human promyelocytic cell line HL-60 following exposure to retinoic acid.(33,34) In these earlier studies, when nuclear run-on analysis was performed, retinoic acid–treated cells, using as probes cDNA sequences coding for two separate exons, there was no change in the rate of transcription of the more 5′ exon, while that of its more 3′ counterpart decreased significantly. The avian β5 gene has not been cloned and so we are not in a position to carry out analogous studies.

Overall, our results suggest that αvβ3 and αvβ5, while both capable of recognizing a similar range of ligands, play separate roles during avian osteoclastogenesis, a hypothesis consistent with observations that the integrins are functionally discrete. Thus, in human foreskin fibroblasts, αvβ5, but not αvβ3, mediates uptake of vitronectin, a ligand for both integrins.(35) Likewise, in cells expressing αvβ3 or αvβ5, it is the latter integrin, and not the former, which facilitates entry of the human adenovirus type 2.(36) An analogous finding obtains for αvβ5 and not αvβ3, with respect to uptake of asbestos fibers by mesothelial cells.(37) Finally, in human smooth muscle cells expressing both αvβ3 and αvβ5, both attachment to and migration on the RGD-containing protein osteopontin are αvβ3- and not αvβ5-dependent.(38)

The finding that retinoic acid suppresses αvβ5 expression, coupled with our earlier reports on αvβ3 induction by both 1,25(OH)2D3 and retinoic acid, suggests a model for the role of these two αv integrins during osteoclast differentiation. Given that early osteoclast precursors capable of matrix recognition express the β5 and not the β3-associated heterodimer, the cells likely utilize αvβ5 for initial attachment to bone. As the cells differentiate under the influence of 1,25(OH)2D3 and retinoic acid, levels of αvβ5 fall, while those of αvβ3 rise, leading to a situation where this latter integrin is the dominant RGD-recognizing moiety on mature osteoclasts, a result seen in both human(39) and rodent(40) cells.

Retinoic acid directly stimulates osteoclastogenesis and increases production, by mature osteoclasts, of the RGD-containing bone matrix protein osteopontin.(41) Thus, our findings that the retinoid reciprocally alters expression of two αv integrins, whose roles are probably complementary, provide yet another molecular marker for the skeletal actions of this steroid.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health grants AR42404 (F.P.R.) AR32788, and DE05413 and a grant from the Shriners Hospital, St. Louis Unit (S.L.T.).

References

- 1.Suda T, Takahashi N, Martin TJ. Modulation of osteoclast differentiation. Endocr Rev. 1992;13:66–80. doi: 10.1210/edrv-13-1-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Teitelbaum SL, Tondravi MM, Ross FP. Osteoporosis. In: Marcus R, Feldman D, Kelsey J, editors. Osteoclast Biology. 3. Academic Press; San Diego, CA, U.S.A: 1996. pp. 61–94. [Google Scholar]

- 3.O’Neill RP, Jones SJ, Boyde A, Taylor ML, Arnett TR. Effect of retinoic acid on the resorptive activity of chick osteoclasts in vitro. Bone. 1992;13:23–27. doi: 10.1016/8756-3282(92)90357-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scheven BA, Hamilton NJ. Retinoic acid and 1,25- dihydroxyvitamin D3 stimulate osteoclast formation by different mechanisms. Bone. 1990;11:53–59. doi: 10.1016/8756-3282(90)90072-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alvarez JI, Teitelbaum SL, Blair HC, Greenfield EM, Athanasou NA, Ross FP. Generation of avian cells resembling osteoclasts from mononuclear phagocytes. Endocrinology. 1991;128:2324–2335. doi: 10.1210/endo-128-5-2324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cao X, Ross FP, Zhang L, MacDonald PN, Chappel J, Teitelbaum SL. Cloning of the promoter for the avian integrin β3 subunit gene and its regulation by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:27371–27380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mimura H, Cao X, Ross FP, Chiba M, Teitelbaum SL. 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 transcriptionally activates the β3-integrin subunit gene in avian osteoclast precursors. Endocrinology. 1994;134:1061–1066. doi: 10.1210/endo.134.3.8119143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Medhora MM, Teitelbaum SL, Chappel J, Alvarez J, Mimura H, Ross FP, Hruska K. 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 up-regulates expression of the osteoclast integrin αvβ3. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:1456–1461. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clohisy DR, Bar-Shavit Z, Chappel J, Teitelbaum SL. 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 modulates bone marrow macrophage precursor proliferation and differentiation: Upregulation of the mannose receptor. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:15922–15929. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wahli W, Martinez E. Superfamily of steroid nuclear receptors: Positive and negative regulators of gene expression. FASEB J. 1991;5:2243–2249. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.5.9.1860615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hough S, Avioli LV, Muir H, Gelderblom D, Jenkins G, Kurasi H, Slatopolsky E, Bergfeld MA, Teitelbaum SL. Effects of hypervitaminosis A on the bone and mineral metabolism of the rat. Endocrinology. 1988;122:2933–2939. doi: 10.1210/endo-122-6-2933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oreffo RO, Teti A, Triffitt JT, Francis MJ, Carano A, Zallone AZ. Effect of vitamin D on bone resorption: Evidence for direct stimulation of isolated chicken osteoclasts by retinol and retinoic acid. J Bone Miner Res. 1988;3:203–210. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650030213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Togari A, Kondo M, Arai M, Matsumoto S. Effects of retinoic acid on bone formation and resorption in cultured mouse calvaria. Gen Pharmacol. 1991;22:287–292. doi: 10.1016/0306-3623(91)90450-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Le Douarin B, vom Baur E, Zechel C, Heery D, Heine M, Vivat V, Gronemeyer H, Losson R, Chambon P. Ligand–dependent interaction of nuclear receptors with potential transcriptional intermediary factors (mediators) Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1996;351:569–578. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1996.0056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haussler MR, Jurutka PW, Hsieh JC, Thompson PD, Selznick SH, Haussler CA, Whitfield GK. New understanding of the molecular mechanism of receptor-mediated genomic actions of the vitamin D hormone. Bone. 1995;17:33S–38S. doi: 10.1016/8756-3282(95)00205-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pereira FA, Qiu Y, Tsai MJ, Tsai SY. Chicken ovalbumin upstream promoter transcription factor (COUP-TF): Expression during mouse embryogenesis. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1995;53:503–508. doi: 10.1016/0960-0760(95)00097-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hynes RO. Integrins: Versatility, modulation, and signaling in cell adhesion. Cell. 1992;69:11–25. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90115-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hu DD, Lin EC, Kovach NL, Hoyer JR, Smith JW. A biochemical characterization of the binding of osteopontin to integrins αvβ1 and αvβ5. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:26232–26238. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.44.26232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.De Nichilo MO, Burns GF. Granulocyte-macrophage and macrophage colony-stimulating factors differentially regulate αv integrin expression on cultured human macrophages. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:2517–2521. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.6.2517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.De Nichilo MO, Yamada KM. Integrin αvβ5-dependent serine phosphorylation of paxillin in cultured human macrophages adherent to vitronectin. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:11016–11022. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.18.11016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chiba M, Teitelbaum SL, Cao X, Ross FP. Retinoic acid stimulates expression of the functional osteoclast integrin αvβ3: Transcriptional activation of the β3 but not αv gene. J Cell Biochem. 1996;62:467–475. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4644(19960915)62:4%3C467::AID-JCB4%3E3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ramaswamy H, Hemler ME. Cloning, primary structure and properties of a novel human integrin beta subunit. EMBO J. 1990;9:1561–1568. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb08275.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fitzgerald LA, Steiner B, Rall SC, Jr, Lo SS, Phillips DR. Protein sequence of endothelial glycoprotein IIIa derived from a cDNA clone: Identity with platelet glycoprotein IIIa and similarity to ‘integrin’. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:3936–3939. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Neugebauer KM, Venstrom KA, Reichardt LF. Adhesion of a chicken myeloblast cell line to fibrinogen and vitronectin through a β1-class integrin. J Cell Biol. 1992;116:809–815. doi: 10.1083/jcb.116.3.809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Neugebauer KM, Reichardt LF. Cell-surface regulation of β1-integrin activity on developing retinal neurons. Nature. 1991;350:68–71. doi: 10.1038/350068a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martin J, Teitelbaum SL, Ross FP, Zhang L, Cao X. Cloning and regulation of integrins on ostoclast precursors. J Bone Miner Res. 1994;9:S133. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bossy B, Reichardt LF. Chick integrin αv subunit molecular analysis reveals high conservation of structural domains and association with multiple β subunits in embryo fibroblasts. Biochemistry. 1990;29:10191–10198. doi: 10.1021/bi00496a006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fambrough DM, Takeyasu K, Lippincott-Schwarz J, Siegel NR. Structure of LEP100, a glycoprotein that shuttles between lysosomes and the plasma membrane, deduced from the nucleotide sequence of the encoding cDNA. J Cell Biol. 1988;106:61–67. doi: 10.1083/jcb.106.1.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ross FP, Alvarez JI, Chappel J, Sander D, Butler WT, Farach-Carson MC, Mintz KA, Robey PG, Teitelbaum SL, Cheresh DA. Interactions between the bone matrix proteins osteopontin and bone sialoprotein and the osetoclast integrin αvβ3 potentiate bone resorption. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:9901–9907. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eckhoff C, Nau H. Identification and quantitation of all-trans- and 13-cis-retinoic acid and 13-cis-4-oxoretinoic acid in human plasma. J Lipid Res. 1990;31:1445–1454. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tamkun JW, DeSimone DW, Fonda D, Patel RS, Buck C, Horwitz AF, Hynes RO. Structure of integrin, a glycoprotein involved in the transmembrane linkage between fibronectin and actin. Cell. 1986;46:271–282. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90744-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Inoue M, Teitelbaum SL, Ross FP. Granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor reciprocally regulates αv-associated integrins on murine osteoclast precursors. Mol Endocrinol. 1998 doi: 10.1210/mend.12.12.0213. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bentley DL, Groudine M. A block to elongation is largely responsible for decreased transcription of c-myc in differentiated HL60 cells. Nature. 1986;321:702–706. doi: 10.1038/321702a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bentley DL, Groudine M. Sequence requirementf for premature termination of transcription in the human c-myc gene. Cell. 1988;53:245–256. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90386-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Panetti TS, McKeown-Longo PJ. The αvβ5 integrin receptor regulates receptor-mediated endocytosis of vitronectin. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:11492–11495. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wickham TJ, Filardo EJ, Cheresh DA, Nemerow GR. Integrin αvβ5 selectively promotes adenovirus mediated cell membrane permeabilization. J Cell Biol. 1994;127:257–264. doi: 10.1083/jcb.127.1.257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boylan AM, Sanan DA, Sheppard D, Broaddus VC. Vitronectin enhances internalization of crocidolite asbestos by rabbit pleural mesothelial cells via the integrin αvβ5. J Clin Invest. 1995;96:1987–2001. doi: 10.1172/JCI118246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liaw L, Skinner MP, Raines EW, Ross R, Cheresh DA, Schwartz SM, Giachelli CM. The adhesive and migratory effects of ostepontin are mediated via distinct cell surface integrins: Role of αvβ5 in smooth muscle cell migration to osteopontin in vitro. J Clin Invest. 1995;95:713–724. doi: 10.1172/JCI117718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nesbitt S, Nesbit A, Helfrich M, Horton M. Biochemical characterization of human osteoclast integrins: Osteoclasts express αvβ5, α2β1, and αvβ1 integrins. J Cell Biol. 1993;268:16737–16745. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shinar DM, Schmidt A, Halperin D, Rodan GA, Weinreb M. Expression of αv and β5 integrin subunits in rat osteoclasts in situ. J Bone Miner Res. 1993;8:403–414. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650080404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kaji H, Sugimoto T, Kanatani M, Fukase M, Kumegawa M, Chihara K. Retinoic acid induces osteoclast-like cell formation by directly acting on hemopoietic blast cells and stimulates ostepontin mRNA expression in isolated osteoclasts. Life Sci. 1995;56:1903–1913. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(95)00165-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]