Abstract

This study used latent transition analysis (LTA) to examine changes in early emotional and behavioral problems in children age 2 to 4 years resulting from participation in a family-centered intervention. A sample of 731 economically disadvantaged families was recruited from among participants in a national food supplement and nutrition program. Families with toddlers between age 2 and 3 were randomized either to the Family Check-Up (FCU) or to a nonintervention control group. The FCU’s linked interventions were tailored to each family’s needs. Assessments occurred at age 2, 3, and 4. The FCU followed age 2 and age 3 assessments. Latent class analyses were conducted on mother reports of behavior and emotional problems from age 2 to 4 to study transitions among the following four groups: (a) externalizing only, (b) internalizing only, (c) comorbid internalizing and externalizing, and (d) normative. LTA results revealed that participation in the FCU increased the likelihood of transitioning from either the comorbid or the internalizing class into the normative class by age 4. These results suggest family interventions in early childhood can potentially disrupt the early emergence of both emotional and behavioral problems.

Keywords: Prevention, Early childhood, Externalizing, Internalizing, Comorbid, Latent transition analysis

Emotional and behavioral difficulties are common concerns that parents have about their young children. A large body of research has indicated that emotional difficulties, including anxiety and depression, and behavioral problems, including aggression and oppositionality, tend to be relatively stable across childhood (Briggs-Gowan et al. 2006). For instance, studies have consistently documented the developmental continuity of conduct problems from early childhood to antisocial behavior in middle childhood and adolescence (Brook et al. 1992; Campbell et al. 2000; Caspi et al. 1998; Hawkins et al. 1986; Shaw et al. 2003; Vicary and Lerner 1983). Modest continuity has also been found for internalizing symptoms, in that youth exhibiting problems with anxiety and depression in early childhood are likely to continue to exhibit those problems into middle childhood and adolescence (Briggs-Gowan et al. 2006; Briggs-Gowan et al. 2004; Warren et al. 1997).

Early emotional and behavioral difficulties may also predict the emergence of problems in other important domains, including academic and social difficulties, into adolescence. For instance, longitudinal studies with children as young as age 3 years (e.g., Caspi et al. 1998; Shaw and Gross 2008) have revealed associations between early behavior problems and long-term profiles of risk, including substance dependence in adolescence and young adulthood. Research has documented similar long-term outcomes associated with internalizing problems, including problems in social, academic, and professional functioning (e.g., Fombonne et al. 2001; Lewinsohn et al. 2003).

Emotional and behavioral difficulties tend to co-occur in childhood at a higher rate than would be expected by chance (Angold et al. 1999; Lewinsohn et al. 1995). Children who exhibit co-occurring emotional and behavioral difficulties tend to show more severe impairment than do those with emotional or behavioral problems alone (Nottelmann and Jensen 1999). Further, evidence suggests that children with co-occurring emotional and behavioral disturbances are the most at risk for several serious adjustment problems in adolescence, including high-risk sexual behavior (Dishion 2000), drug abuse (Rohde et al. 1995), academic failure, suicide, and other serious outcomes (Asarnow and Carlson 1988; Capaldi 1992; Patterson and Stoolmiller 1991; Rohde et al. 1995). Not surprisingly, youth comorbid mood and behavioral problems are also the most costly to society in terms of use of mental health and juvenile justice resources (Miller 2004).

Early Intervention

In light of the prevalence and adverse consequences of early emotional and behavior problems, it is critical to improve our understanding of the etiology, course, and prevention of co-occurring emotional and behavioral problems in early childhood. Preventive interventions initiated in early childhood may be particularly beneficial. The toddler years represent a time of marked change for children in terms of cognitive, emotional, and physical maturation, requiring parents to provide positive behavioral support and monitoring, and to scaffold developmentally appropriate behaviors (Gardner et al. 1999). For many parents, this transition is associated with a decrease in parental pleasure in childrearing from the first to second years (Fagot and Kavanaugh 1993), and families’ adaptation to this developmental transition forms the basis for subsequent developmental stages (Shaw et al. 2000). Intervening during this transitional period could be instrumental in preventing the later development of adolescent problem behaviors such as delinquency, deviant peer association, and internalizing disorders.

A wealth of research has documented longitudinal associations between harsh, punitive parenting in early childhood and later child problem behavior (e.g. Campbell et al. 1996; Shaw et al. 1996; Shaw et al. 2003), as well as between the lack of parental warmth, involvement, and responsivity, with later emotional and behavior problems (e.g., Gardner 1987, 1994; Shaw et al. 1998; Supplee et al. 2007). Given the centrality of family processes to the early development of emotional and behavioral problems, family interventions are likely to be critical to preventing their development across early childhood. Indeed, a number of parenting interventions have been found to be effective for reducing early conduct problems (e.g., Brinkmeyer and Eyberg 2003; Olds et al. 1997; Webster-Stratton 1990). Less research has examined family interventions for internalizing difficulties, although several such interventions have been shown to reduce emotional distress in school-age children and adolescents (e.g., Asarnow et al. 2002; Brent et al. 1997; Diamond et al. 2002).

To date, few studies have examined the impact of parenting interventions on co-occurring emotional and behavioral difficulties. Unfortunately, youth with co-occurring internalizing and externalizing problems are frequently excluded from efficacy trials, compared with children with a single diagnosis. The severity of co-occurring emotional and behavior problems in childhood does not suggest that parents and children in these families will be unresponsive to interventions, and several studies support the hypothesis that the families of children with comorbid emotional and behavioral problems are responsive to interventions that are carefully tailored to their needs. Beauchaine et al. (2005) reported that across six randomized trials of a parent-training intervention for families with 3- to 8-year-old children with early conduct problems, children with co-occurring anxiety and depression demonstrated greater reductions in early externalizing problems from pre- to post-treatment and beyond to 1-year follow-up than did those with single disorders. Similarly, Beauchaine et al. (2000) reported more positive outcomes following inpatient treatment for 4- to 12-year-old boys with conduct disorder/ADHD diagnoses if they also had comorbid depression/anxiety diagnoses, relative to boys without the co-occurring disorders. Kazdin and Whitley (2006) reported that the presence of comorbid emotional problems predicted greater therapeutic change in 3–14 year old youth referred for behavior problems and treated with parent management training alone or in conjunction with problem-solving skills training. Costin and Chambers (2007) also found that 5–13 year old youth with co-occurring emotional and behavioral problems showed the greatest improvements following parent management training.

The consistency of the results that youth with co-occurring emotional and behavioral problems appear to show the greatest improvements following parent-focused interventions may best be interpreted in light of results documenting that in early childhood, problematic parent–child relationships predict substantially increased risk of exhibiting co-occurring emotional and behavior problems, relative to problems in either domain alone (Thomas and Guskin 2001). Interestingly, research using a genetically informative sample of 2- to 4-year-old twins found that co-occurring emotional and behavioral problems were strongly related to shared family environmental influences, a relatively rare finding in the behavior genetics literature (Gregory et al. 2004). Such results highlight the potential importance of parenting behaviors and family factors for the development co-occurring emotional and behavioral problems in early childhood. As such, we would hypothesize that improving parenting skills through parent-focused interventions may be especially important for treating youth with co-occurring emotional and behavioral difficulties. In light of this possibility, the current study examined the impact of the Family Check-Up (FCU) intervention on the progression of co-occurring emotional and behavior problems in young children from age 2 to 4 years.

Previous Research on the Family Check-up

The FCU is a brief intervention that includes a broad assessment of family context and parenting practices (see Dishion and Stormshak 2007). Unlike many parenting interventions in which parents receive all intervention components in a structured sequence, the FCU is a tailored intervention following a randomized encouragement design, which recognizes that individual families may have very different intervention needs (Mercer et al. 2007). The core feature of a randomized encouragement intervention is that specific targets and doses are determined collaboratively with each family following a comprehensive assessment of youth and family functioning. Advantages of this approach include decreased likelihood of negative intervention effects, elimination of treatment components that are inappropriate for a given family, decreased waste of resources and greater efficiency in carrying out intervention and potentially increased compliance with treatment and intervention effectiveness (e.g. Collins et al. 2004). Such tailored interventions may be particularly attractive to high-risk families for whom extended intervention engagement may be difficult due to challenging circumstances.

The FCU was directly inspired by the motivational interviewing (MI) framework of Miller and Rollnick (2002). The MI approach is intended to motivate parents to engage with treatment services and to encourage behavior change in families of high-risk youth. The FCU is the first step in a menu of empirically supported and family-centered interventions designed to strengthen parenting skills and promote positive behaviors (Dishion and Kavanagh 2003). In contrast to the standard clinical model, the FCU is rooted in a health maintenance model, which emphasizes periodic contact with families during the course of key developmental transitions. Our study focused primarily on the FCU for families with young children who were engaged in the Women, Infants and Children Nutrition Program (WIC) service system and who demonstrated risk for behavioral problems and in some cases, comorbid emotional problems.

Previous research has examined the impact of the FCU on problem behavior in early adolescence, when offered in a public school setting. Dishion et al. (2002) found that proactive parent engagement reduced substance use among high-risk adolescents and prevented substance use among typically developing youth. Significant reductions in these problem behaviors resulted from an average of six direct contact meetings with parents over 3 years. Complier average causal effect analyses supported the proposal that participation in the FCU and linked services resulted in significant, long-term reductions in substance use and antisocial behavior, including decreased substance use diagnoses and fewer arrests by the end of high school (Connell et al. 2007). Shaw and colleagues (2006) applied the FCU to a sample of 120 high-risk families of toddlers involved in the WIC program. Engagement in the FCU resulted in reductions in subsequent child problem behavior and improvement in parent involvement at child age 3 and 4, respectively (Gardner et al. 2007; Shaw et al. 2006).

The Current Study

This study examined data from 731 families participating in WIC service systems that were recruited when the children were approximately 2 years old. These children were deemed at-risk for showing early-starting pathways of behavior problems on the basis of sociodemographic risk (i.e., low income and parental education), family risk (e.g., maternal depression, parental drug abuse, teen parent), and child risk (e.g., high levels of conduct problems). Half of the families were randomly assigned to receive the FCU. Analyses focused on age 3 and 4 follow-up reports of child conduct and internalizing problems, collected one and 2 years after initial contact with families. Families in this study, which we refer to as the Early Steps Multisite study (ES-M), were recruited from three regions: metropolitan Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, suburban Eugene, Oregon, and rural Charlottesville, Virginia. The sample reflects cultural diversity in that it includes a high percentage of African American, European American, and Latino families. In addition to the FCU, families in the intervention group were provided tailored services following the FCU, as needed.

This study’s analyses extend two earlier reports on the ES-M sample that described reductions in child conduct problems and internalizing symptoms as a result of participation in the FCU. Dishion et al. (2008) used Latent Growth Modeling (LGM) procedures to examine intervention effects on conduct problems from age 2 to 4, and found a significant intervention effect on the rate of change in such problems, mediated by improvements in observed parenting behavior from age 2 to 3. Shaw et al. (2008) used separate LGM analyses to examine changes in internalizing symptoms across age 2 to 4, and found intervention predicted decreased growth in internalizing and externalizing symptoms, with intervention effects mediated by decreased maternal depressive symptoms from age 2 to 3. Although these studies provide important evidence for the effectiveness of the FCU intervention, these LGM analyses have important limitations. In particular, internalizing and externalizing symptoms were treated separately in these analyses, and LGM analyses in general do not readily account for differences in profiles of co-occurring internalizing and externalizing symptoms across children. It is likely that some children in this sample exhibited elevations solely in either internalizing or externalizing domains, while others demonstrated co-occurring symptoms. In line with the results of Beauchaine et al. (2000, 2005), it is possible that the FCU intervention may be differentially effective for youth with different symptom profiles, exerting strongest effects for youth with co-occurring problems. Such a possibility may be best examined using a person-centered analytic approach such as latent transition analysis (LTA) that provides a means of examining such questions directly (see Connell et al. 2006).

In the current study, we used latent transition analysis (LTA) to identify classes (i.e., latent groups) of youth exhibiting distinct profiles of internalizing and externalizing symptoms from age 2 to 4. This strategy enabled us to examine whether participation in the FCU affected the transition between latent classes across ages 2, 3, and 4. LTA is particularly suited to examining changes in class membership over time (i.e., comorbid, internalizing-only, or externalizing-only classes of youth). It treats symptom clustering as an unobserved, latent categorical variable. That is, a child’s symptom class membership is not directly observed, but is instead inferred by a classification model, which provides the basis for studying transitions from one group to another over time. As such, LTA provides a means of dealing with measurement error and reducing bias in estimates of stability and change across classes of youth over time (see Graham et al. 1991; Nylund et al., under review).

Materials and Methods

Study Participants

Participants included 731 mother–child dyads recruited between 2002 and 2003 from WIC programs in the metropolitan areas of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, Eugene, Oregon, and Charlottesville, Virginia (Dishion et al. 2008). Families were approached at WIC sites and invited to participate if they had a son or daughter between age 2 years 0 months and 2 years 11 months. Recruited families were screened to ensure that they met the study criteria of having socioeconomic, family, and/or child risk factors for future behavior problems. Criteria for screening were defined as at least one SD above normative averages, derived from published standardization data, in the following three domains: (a) child behavior (conduct problems, high-conflict relationships with adults), (b) family problems (maternal depression, daily parenting challenges, substance use, teen parent status), and (c) sociodemographic risk (low education achievement and low family income using WIC criterion). For inclusion in the sample, high risk status on at least two of the three risk domains was required. In cases where the high risk criterion was not met for child behavior, children were required to have above average scores on either the Eyberg Child Behavior Inventory Intensity or Problem scales (Robinson et al. 1980) to increase the probability that parents would be motivated to change this behavior.

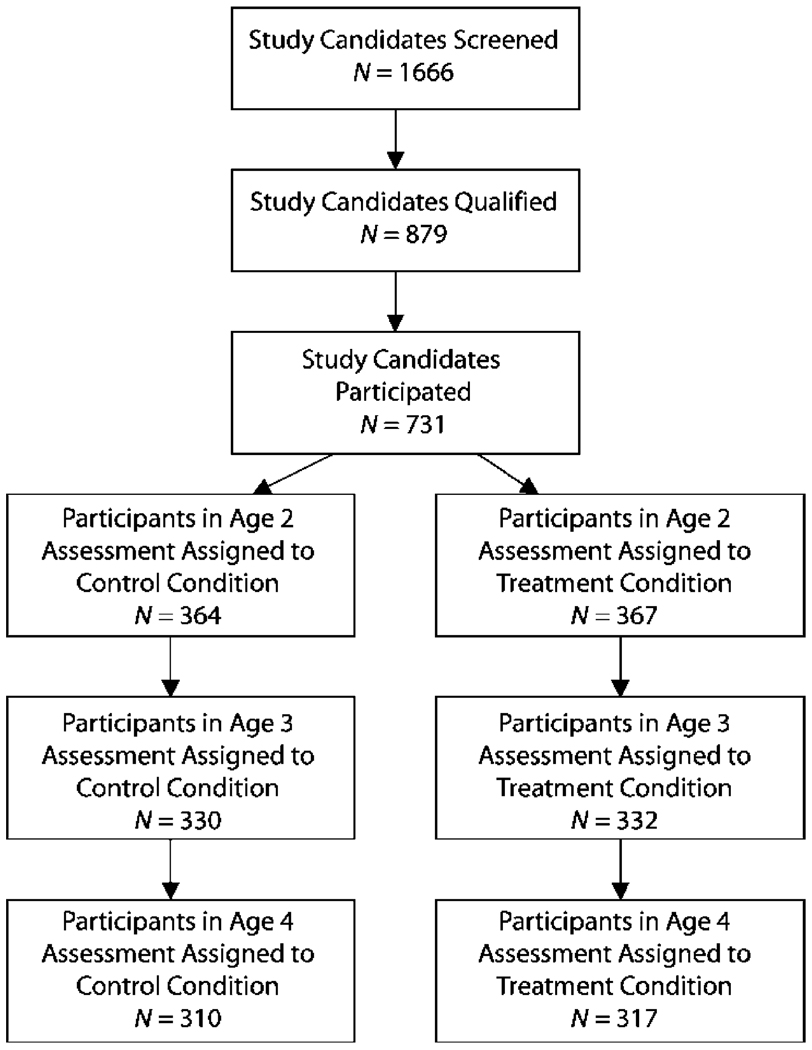

As shown in Fig. 1, of 1,666 parents with appropriately aged children who were approached at WIC sites across the three study sites, 879 families met the eligibility requirements and 731 agreed to participate. Of these families, 272 (37%) were recruited in Pittsburgh, 271 (37%) in Eugene, and 188 (26%) in Charlottesville. More participants were recruited in Pittsburgh and Eugene due to the larger population of these regions relative to Charlottesville. Children in the sample had a mean age of 29.9 months (SD=3.2) at the age 2 assessment. Demographic data are provided in Table 1. The final sample was ethnically diverse and primarily of lower SES.

Fig. 1.

Participant flow chart

Table 1.

Demographics

| Sample descriptives | |

|---|---|

| Participants | |

| Race | |

| African American | 27.9% |

| European American | 50.1% |

| Biracial | 13.0% |

| Other race | 8.9% |

| Ethnicity | |

| Hispanic | 13.4% |

| Target child age | M=28.2 (SD=3.28) |

| Target child gender | 49.5% Female |

| Annual family income <$20,000 | 66.3% |

| Family members per household | M=4.5 (SD=1.63) |

| Education | |

| High school diploma | 41.0% |

| 1 to 2 years post-high school | 32.7% |

| Treatment participation | |

| Age 2 feedback received | 77.9% |

| Age 3 feedback received | 65.4% |

Retention

Of the 731 families who initially participated, 659 (90.2%) were available at the 1-year follow-up and 619 (84.7%) participated at the 2-year follow-up when children were between age 4 and 4 years 11 months. At age 3 and 4, selective attrition analyses revealed no significant differences relevant to project site, children’s race, ethnicity, gender, levels of maternal depression, or children’s externalizing behaviors (parent reported). No differences were found in the number of participants who were not retained in the control versus the intervention groups at age 3 (n=40 and n=32, respectively) and age 4 (n=58 and n=53, respectively).

Measures

Demographics Questionnaire

A demographics questionnaire was administered to the mothers during the age 2 and age 4 visits. This measure included questions about family structure, parental education and income, parental criminal history, and areas of familial stress.

Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL)

The CBCL is a well-established and widely used 99-item questionnaire that assesses parental reports of behavioral and emotional problems in young children from age 1.5 to 5 years. Mothers completed the CBCL at the child age 2, 3, and 4 visits. The CBCL has two broad-band factors, Internalizing and Externalizing. The Internalizing scale comprises four subscales, including Emotional Reactivity, Anxiety and Depression, Somatic Problems, and Social Withdrawal. The Externalizing scale comprises two subscales, Aggression and Attention Problems. High internal consistency reliability was found for the internalizing and externalizing scales across all assessment years (alpha-reliabilities ranged from 0.82 to 0.91). For use in the latent class analyses (LCAs) and LTAs, scores on these six subscales were dichotomized to reflect youth being rated in the normative range on a given scale (t score <60) versus in the borderline or clinical range (t score ≥60; Achenbach and Rescorla 2000).

Assessment Protocol

Parents (i.e., mothers and, if available, alternative caregivers such as fathers or grandmothers) who agreed to participate in the study were scheduled for a 2.5-h home visit. During the home visit, family members completed questionnaires, and parents and children took part in a series of structured interaction tasks which were video-taped (these observation tasks are not included in the current analyses, and details are available in Dishion et al. (2008). The same home visit and observation protocol was repeated at age 3 and 4 for both the control and the intervention group. Families received $100, $120, and $140 for participating in the age 2, 3, and 4 home visits, respectively.

Randomization to FCU and control groups was conducted by a staff member who had not been involved in recruitment. Randomization was balanced by gender to ensure an equal number of males and females in the control and intervention groups. To ensure examiner blindness to the intervention condition, a sealed envelope revealing the family’s assignment was opened and shared with the family after the age 2 assessment was completed. Examiners who carried out follow-up assessments were blind to the families’ intervention assignment. To optimize the internal validity of the study (i.e., prevent differential drop out for experimental and control conditions), the assessments were completed before random assignment results were revealed to either the research staff or the family.

Intervention Protocol

The FCU Families randomly assigned to the intervention condition, and families in the intervention condition were then scheduled to meet with a parent consultant to complete the Family Check-Up (FCU). The FCU is a brief, three-session intervention based on motivational interviewing (Dishion and Kavanagh 2003; Dishion and Stormshak 2007) and modeled after the Drinker’s Check-Up (Miller and Rollnick 2002), consisting for this trial of an assessment (baseline), randomization, an initial interview, a feedback session, and dependent on family preference, possible follow-up sessions. Families were given a $25 gift certificate for completing the FCU at the end of the feedback session. Essential objectives of the feedback session were to explore issues in managing child problem behavior,, support existing parenting strengths, and identify services appropriate to the family needs. During this session the parent was offered follow-up sessions focused on parenting practices, other family management concerns (e.g., coparenting), and contextual issues (e.g., parental well being, marital adjustment, housing).

Parent consultants who facilitated the FCU and follow-up parenting sessions were a combination of Ph.D.- and master’s-level clinicians, all with previous experience with family-based interventions. Parent consultants were initially trained for 2.5–3 months using a combination of strategies, including didactic instruction and role playing, followed by ongoing videotaped supervision of intervention activity. Before working with study families, parent consultants were certified by lead parent consultants at each site, who had been certified by Dr. Dishion. Certification was established by reviewing videotapes of feedback and follow-up intervention sessions to evaluate whether parent consultants were competent in all critical components of the intervention as described later in this article. Coder certification was repeated yearly to reduce drift from the intervention model (Forgatch et al. 2005). Weekly cross-site videoconferences and annual parent consultant meetings were held further enhance fidelity.

Of the families assigned to the treatment condition, 77.9% participated in the initial parent consultant meeting and feedback sessions at child age 2 and 65.4% at age 3 (see Table 1). For those families, the average number of sessions was 3.32 (SD=2.84) at child age 2 and 2.83 (SD= 2.70) at age 3, including the initial parent consultant meeting and feedback sessions.

Analysis strategy

The central analyses used an LTA framework to examine changes in latent class membership over time, across the intervention and control groups. LTA is an advanced autoregressive model in which class membership at each time point is estimated by a categorical latent variable. LTA includes both a measurement component and a structural component. For the measurement component, item probabilities are class-specific parameters that describe the likelihood of an individual in a given class to endorse each item. Two structural components include class probabilities, which describe the size of each latent class at each time point, and transition probabilities, which are conditional probabilities describing the probability of being in a given state at time=t, conditional on the state at time=t−1.

The current analyses proceeded through the LTA process in several steps, as put forth by Nylund et al. (under review). First, separate LCAs were used to examine the optimal number of latent classes at each study wave. Mixture modeling (of which LCA is a specific form) is an active area of methods research regarding the optimal approach to determining the number of latent classes (e.g. Nylund et al. 2007). Fit indices were obtained for unconditional models with one to six classes at each age. Muthén and Muthén (2000) have recommended the following four criteria for selecting the optimal number of latent classes in factor mixture models: (a) the Bayesian information criteria (BIC) and a sample-size adjusted version of the BIC (Adj BIC), with lower scores representing better-fitting models; (b) entropy, which is a measure of the quality of classification across models, with higher values indicating better classification of individuals into their most likely trajectory class; (c) the bootstrapped likelihood ratio test (BLRT), which provides a statistical comparison of the fit of a given model with a model of one fewer classes; and (d) the theoretical relevance and usefulness of latent trajectory classes. Recent simulation studies by Nylund et al. (2007) supported the use of Adj BIC and BLRT for selection of the optimal number of classes in LCA models, with the BLRT providing particularly consistent correct results. In light of these findings, we placed primary weight on the BLRT and the Adj BIC values in selecting the number of classes. Latent Class Analyses were conducted with Mplus 4.21 (Muthen and Muthen 2007) due to the availability of multiple model fit indices not available in other statistics platforms and the ease of employing randomized starting values. Models were fit using 100 randomized start values run for ten iterations, with the best-fitting 25 start values run to convergence.

Next, LTA was used to examine transitions across classes from age 2 to age 3, and from age 3 to age 4. Intervention status was used as a grouping variable in the latent transition model, enabling the examination of rates of transition across the control and intervention groups. Measurement invariance over time and across the intervention and control groups was modeled, following results of the LCA analyses which suggested that such invariance was supported by the data. Detailed statistical presentations of the general LTA framework are available in Nylund et al. (under review), Humphreys and Janson (2000), and Reboussin et al. (1998). LTA analyses were conducted using both Mplus 4.21 (Muthen and Muthen 2007) and SAS Proc LTA 1.1.3 (Lanza et al. 2007). Results across platforms were quite similar, and we present the SAS Proc LTA results due to the ease of presenting separate transition tables for intervention and control groups.

Results

Descriptive statistics for CBCL subscales are shown in Table 2. Correlations for all variables are shown in Table 3. No significant associations were found between treatment group and any age 2 child problem index, suggesting that randomization was successful.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics for CBCL Subscales (Percent of Sample with t score >60)

| Age 2 | Age 3 | Age 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional reactivity | 32.5 | 24.7 | 24.9 |

| Anxiety and depression | 21.4 | 19.0 | 19.1 |

| Somatic problems | 21.8 | 20.6 | 17.8 |

| Social withdrawal | 43.7 | 37.8 | 35.1 |

| Attention problems | 39.5 | 29.5 | 24.4 |

| Aggression | 48.6 | 34.7 | 28.3 |

Table 3.

Correlations among Study Variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Treatment group | 1.00 | ||||||||||||||||

| 2. Age 2 emotionally reactive | 0.02 | 1.00 | |||||||||||||||

| 3. Age 2 anxious, depressed | 0.02 | 0.59a | 1.00 | ||||||||||||||

| 4. Age 2 somatic complaints | 0.03 | 0.34a | 0.30a | 1.00 | |||||||||||||

| 5. Age 2 withdrawn | 0.02 | 0.47a | 0.49a | 0.22a | 1.00 | ||||||||||||

| 6. Age 2 attention problems | 0.01 | 0.32a | 0.23a | 0.06 | 0.38a | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| 7. Age 2 aggressive behavior | 0.03 | 0.52a | 0.40a | 0.12a | 0.35a | 0.50a | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| 8. Age 3 emotionally reactive | 0.02 | 0.55a | 0.44a | 0.33a | 0.31a | 0.22a | 0.34a | 1.00 | |||||||||

| 9. Age 3 anxious, depressed | −0.02 | 0.44a | 0.55a | 0.30a | 0.35a | 0.19a | 0.28a | 0.63a | 1.00 | ||||||||

| 10. Age 4 somatic complaints | −0.06 | 0.22a | 0.20a | 0.45a | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.30a | 0.25a | 1.00 | |||||||

| 11. Age 3 withdrawn | 0.01 | 0.39a | 0.38a | 0.23a | 0.48a | 0.23a | 0.25a | 0.53a | 0.54a | 0.21a | 1.00 | ||||||

| 12. Age 3 attention problems | −0.02 | 0.26a | 0.18a | 0.09a | 0.23a | 0.49a | 0.37a | 0.40a | 0.37a | 0.09a | 0.41a | 1.00 | |||||

| 13. Age 3 aggressive behavior | −0.02 | 0.38a | 0.29a | 0.14a | 0.23a | 0.31a | 0.56a | 0.57a | 0.46a | 0.12a | 0.44a | 0.57a | 1.00 | ||||

| 14. Age 4 emotionally reactive | −0.04 | 0.48a | 0.33a | 0.31a | 0.25a | 0.22a | 0.27a | 0.56a | 0.45a | 0.43a | 0.40a | 0.33a | 0.39a | 1.00 | |||

| 15. Age 4 anxious, depressed | −0.04 | 0.37a | 0.42a | 0.28a | 0.22a | 0.15a | 0.20a | 0.46a | 0.55a | 0.43a | 0.40a | 0.29a | 0.36a | 0.67a | 1.00 | ||

| 16. Age 4 withdrawn | −0.04 | 0.30a | 0.32a | 0.31a | 0.39a | 0.20a | 0.17a | 0.37a | 0.38a | 0.39a | 0.58a | 0.25a | 0.28a | 0.49a | 0.47a | 1.00 | |

| 17. Age 4 attention problems | −0.01 | 0.21a | 0.16a | 0.11a | 0.18a | 0.44a | 0.26a | 0.32a | 0.30a | 0.21a | 0.33a | 0.59a | 0.42a | 0.44a | 0.38a | 0.37a | 1.00 |

| 18. Age 4 aggressive behavior | −0.08 | 0.30a | 0.18a | 0.14a | 0.17a | 0.31a | 0.42a | 0.40a | 0.33a | 0.26a | 0.34a | 0.48a | 0.61a | 0.61a | 0.47a | 0.42a | 0.61a |

Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (two-tailed). CBC variables are t scores.

Latent Class Analyses at Age 2, 3, and 4

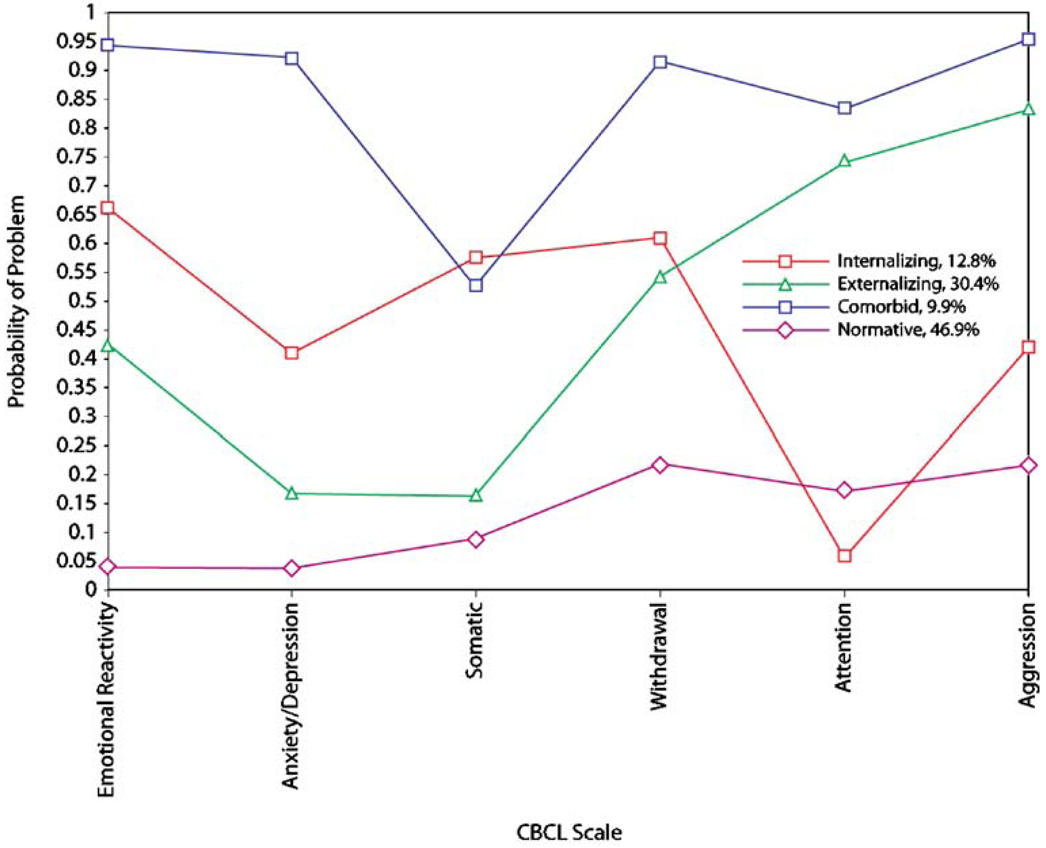

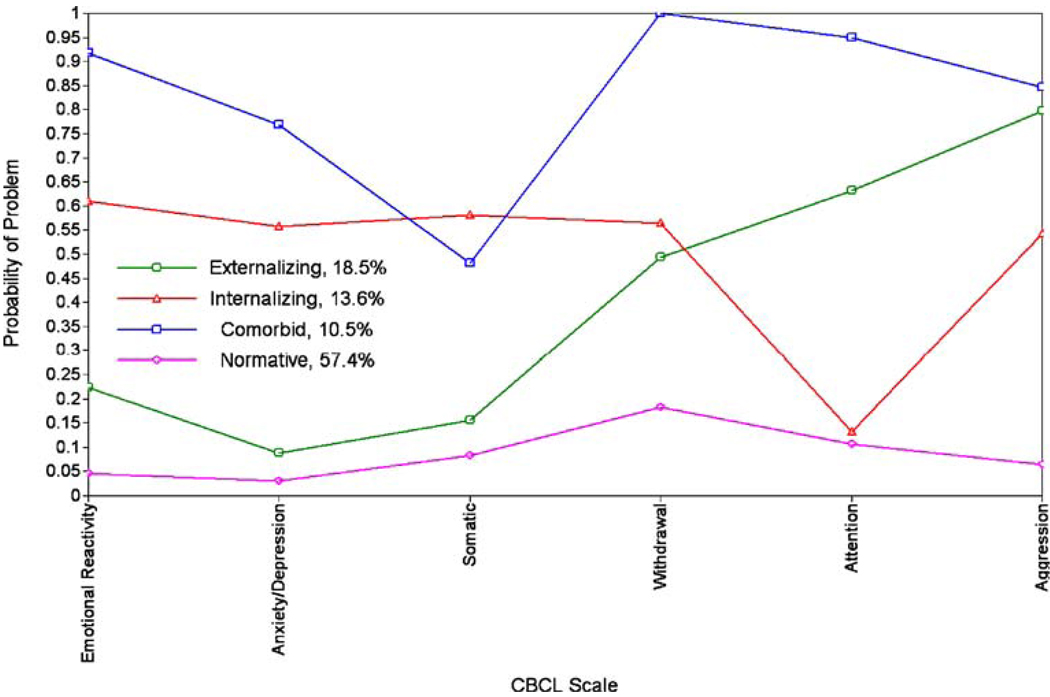

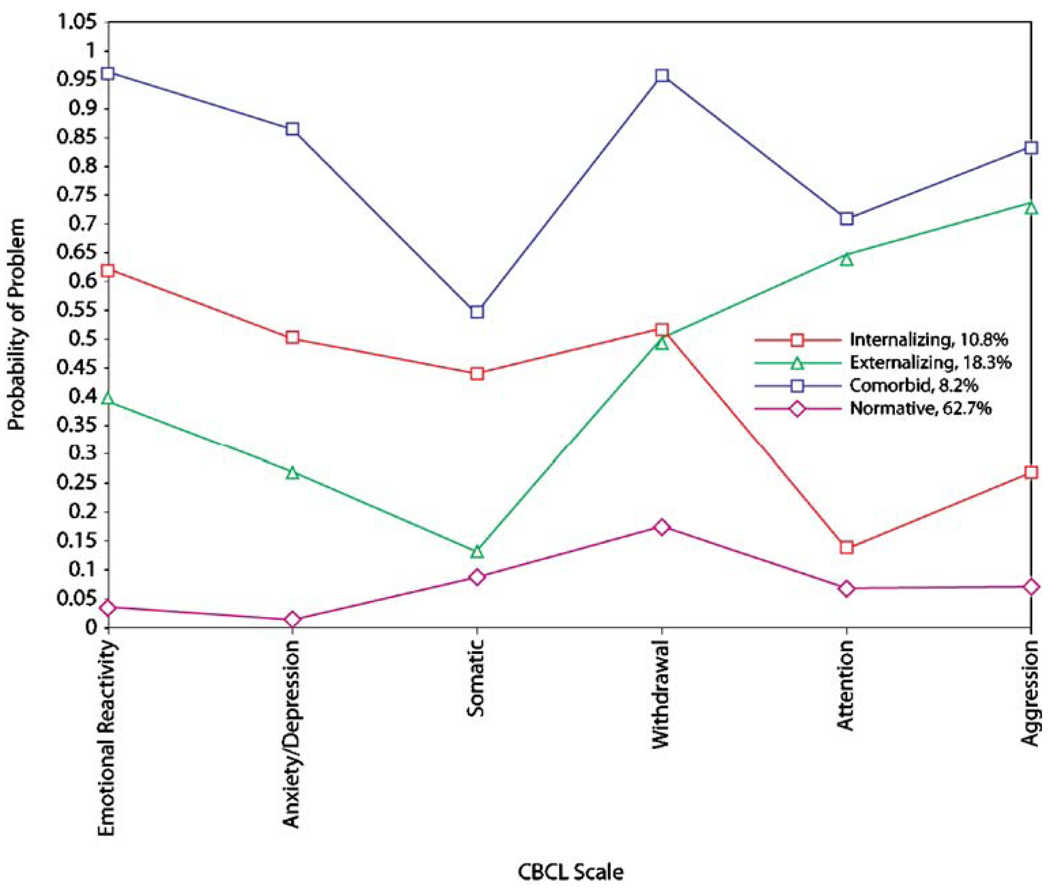

As indicated, separate LCAs at age 2, 3, and 4 were first examined to determine the optimal number of classes at each age. As shown in Table 4, both the Adj BIC and the BLRT supported a four-class solution at ages 2 and 3. At age 4, the BLRT supported a four-class solution while the Adj BIC supported a three-class solution. We chose the four-class solution to represent optimal fit in light of Nylund et al. (2007) recommendations, and consistency of the four-class solution with hypotheses and theories, as well as the consistency of the four-class solution at age 4 with the four-class solution at ages 2 and 3. The resulting four classes at ages 2, 3, and 4 are depicted in Fig. 2, Fig. 3, and Fig. 4. Most youth at each age are in a class with low probability of being in the borderline/clinical range on any scale. Because of the relative size and low likelihood of problems, we label this class normative throughout the remainder of this article. A second class showed relatively elevated probabilities of significant problems on the two Externalizing subscales, along with the Withdrawal scale. We refer to this class as externalizing. A third class showed relatively elevated likelihoods of being in the clinical range on the four Internalizing scales, so we refer to this class as internalizing. Finally, a fourth class showed elevations on all six subscales, so this class is labeled comorbid. These four classes match well with the four classes that were expected on the basis of theory and past research, lending increased confidence that they reflect meaningful clusters of youth. It is worth emphasizing that the sizes of the classes were somewhat different at ages 2, 3, and 4, particularly for the externalizing class, which decreased in size over time (30.4% at age 2 to 18.3% at age 4), and the normative class, which increased in size over time (46.9% at age 2 to 62.7% at age 4).

Table 4.

Fit Statistics for Age 2, Age 3, and Age 4 LCA Models

| 1-class | 2-class | 3-class | 4-class | 5-class | 6-class | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age 2 | ||||||

| Log likelihood value | −2,717.28 | −2,514.25 | −2,490.63 | −2,473.22 | −2,465.99 | −2,462.72 |

| Number of free parameters | 6 | 13 | 20 | 27 | 34 | 41 |

| Entropy | NA | 0.66 | 0.64 | 0.64 | 0.78 | 0.78 |

| BIC | 5,474.15 | 5,114.22 | 5,113.13 | 5,124.44 | 5,156.15 | 5,195.74 |

| Adj BIC | 5,455.10 | 5,072.94 | 5,049.62 | 5,038.71 | 5,048.19 | 5,065.56 |

| BLRT | NA | 406.09* | 47.24* | 34.84* | 14.45 | 6.56 |

| Age 3 | ||||||

| Log likelihood value | −2,258.88 | −1,997.67 | −1,976.98 | −1,959.06 | −1,953.55 | −1,949.51 |

| Number of free parameters | 6 | 13 | 20 | 27 | 34 | 41 |

| Entropy | NA | 0.76 | 0.70 | 0.71 | 0.74 | 0.77 |

| BIC | 4,556.63 | 4,079.55 | 4,083.54 | 4,093.04 | 4,127.38 | 4,164.64 |

| Adj BIC | 4,537.58 | 4,038.28 | 4,020.04 | 4,007.31 | 4,019.43 | 4,034.47 |

| BLRT | NA | 522.42* | 41.37* | 35.85* | 11.01 | 8.08 |

| Age 4 | ||||||

| Log likelihood value | −2,053.77 | −1,797.87 | −1,779.43 | −1,769.38 | −1,763.90 | −1,759.25 |

| Number of free parameters | 6 | 13 | 20 | 27 | 34 | 41 |

| Entropy | NA | 0.79 | 0.71 | 0.73 | 0.66 | 0.75 |

| BIC | 4,146.12 | 3,679.75 | 3,687.41 | 3,712.32 | 3,746.35 | 3,782.05 |

| Adj BIC | 4,127.07 | 3,638.04 | 3,623.92 | 3,626.60 | 3,638.41 | 3,651.88 |

| BLRT | NA | 511.80* | 36.90* | 20.09* | 10.96 | 9.30 |

Italic indices represent best-fitting class, as indicated by that fit index.

p<0.05

Fig. 2.

LCA results at age 2

Fig. 3.

LCA results at age 3

Fig. 4.

LCA results at age 4

Latent Transition Analyses from Age 2 to 4

LTAs were conducted next, which permitted the examination of transitions across classes from age 2 to age 4. Intervention status served as a grouping variable, enabling the examination of rates of transition across the control and intervention groups. The proportions of youth in each class at each age across the control and intervention conditions are shown in Table 5. As was found in the LCA models, the externalizing class decreased in size from age 2 to age 4, while the normative class grew substantially over time. Conversely, changes in the proportion of youth in the internalizing and comorbid classes were less dramatic across ages 2, 3, and age 4. The size of the normative group differed by 9.3% across the intervention and control groups at age 4, with more youth moving into the normative group over time in the intervention group.

Table 5.

Estimated Class Membership at Ages 2 and 4 Across Intervention Groups from LTA

| Comorbid (%) |

Normal (%) |

Externalizing (%) |

Internalizing (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | ||||

| Age 2 | 17.5 | 25.4 | 41.3 | 15.9 |

| Age3 | 18.1 | 43.0 | 24.4 | 14.6 |

| Age 4 | 15.8 | 45.9 | 22.1 | 16.2 |

| Treatment | ||||

| Age 2 | 19.7 | 27.5 | 40.4 | 12.3 |

| Age 3 | 14.7 | 44.6 | 25.4 | 15.4 |

| Age 4 | 12.1 | 55.2 | 18.3 | 14.4 |

Latent transition probabilities across the intervention and control groups are presented in Table 6. As shown, the normative group was highly stable over time in both the intervention and control groups. From age 2 to 3, two transition probabilities showed marked differences across the control and intervention condition. In the control group, youth in the age 2 comorbid class were disproportionately likely to remain in the comorbid condition by age 3, and unlikely to transition into the internalizing class by age 3, relative to youth in the intervention condition.

Table 6.

Latent transition probabilities for treatment and control groups

| Age 3 | Age 4 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comorbid | Normal | Externalizing | Internalizing | Comorbid | Normal | Externalizing | Internalizing | |||

| Control | ||||||||||

| Comorbid | Age 2 | 0.86 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.14 | Age 3 | 0.56 | 0.00 | 0.38 | 0.06 |

| Normal | 0.00 | 0.95 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.91 | 0.05 | 0.04 | ||

| Externalizing | 0.07 | 0.31 | 0.59 | 0.03 | 0.10 | 0.28 | 0.53 | 0.09 | ||

| Internalizing | 0.02 | 0.38 | 0.00 | 0.60 | 0.22 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.78 | ||

| Intervention | ||||||||||

| Comorbid | Age 2 | 0.54 | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.34 | Age 3 | 0.63 | 0.19 | 0.07 | 0.11 |

| Normal | 0.00 | 0.98 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.95 | 0.01 | 0.04 | ||

| Externalizing | 0.10 | 0.29 | 0.60 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.26 | 0.66 | 0.05 | ||

| Internalizing | 0.00 | 0.37 | 0.00 | 0.63 | 0.14 | 0.22 | 0.00 | 0.64 | ||

There were more differences in the transition probabilities from age 3 to 4 across the intervention and control conditions, primarily for youth in the comorbid or internalizing classes at age 3. First, youth in the comorbid class at age 3 were more likely to transition into the normal class at age 4 in the intervention group than in the control group (indeed, no youth in the control group transitioned from the comorbid class to the normal class at age 4). Youth in the age 3 comorbid class were also more likely to transition into the externalizing class in the control versus intervention group. Youth in the age 3 internalizing class were more likely to both remain in the internalizing class or to transition into the comorbid class if they were in the control versus intervention group. Conversely, youth in the age 3 internalizing class were more likely to transition into the normal group in the intervention versus control group (indeed, no youth in the control group made this transition). Finally, youth in the age 3 externalizing class showed somewhat more stability in class membership in the intervention versus control condition, although the difference may be related to a slightly higher likelihood of transition into the comorbid class for control youth.

We examined the statistical and practical significance of these differences in two primary ways. First, we conducted a series of nested model comparisons to examine the statistical significance of differences in specific transition probabilities across groups, comparing fit of a model with all parameters constrained to be equal across intervention and control groups with models allowing different parameters to vary across groups. Allowing transition probabilities for the comorbid and internalizing classes to vary across treatment and control groups for both transitions led to significantly improved model fit (ΔG2=22.23, Δdf=12, p<0.05), while allowing transitions to vary for the externalizing and normal groups to also vary across groups did not result in significant improvements in model fit. Second, we conducted a follow-up model using intervention status as a covariate in order to examine odds-ratios of the likelihood of specific transitions across classes related to intervention status. SAS Proc LTA does not offer statistical tests of these covariate effects on transition probabilities, but provides odds ratios, accounting for uncertainty in class membership. Due to the sparseness of particular cells, we modeled binary odds ratios, reflecting the effect of treatment on transitioning into the normative class versus any other class. Odds ratios are shown in Table 7, and are consistent with prior results, highlighting that the odds of transitioning into the normative class from the comorbid class or internalizing class appear to be substantially affected by the receipt of intervention services. For the internalizing class, the effect appears limited to the age 3 to 4 transition. Full details of these follow-up models are available from the first author upon request.

Table 7.

Odds Ratios for Likelihood of Transitioning into Normal Class Versus Any Other Class

| AGE 3 Normal |

AGE 4 Normal |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comorbid | Age 2 | 60.42 | Age 3 | 167.80 |

| Normal | 3.75 | 1.94 | ||

| Externalizing | 0.89 | 0.89 | ||

| Internalizing | 1.01 | 9.35 |

Discussion

The goal of this study was to consider the potential of family-centered interventions provided in early childhood to prevent the occurrence of more pervasive mental health problems in children, such as the co-occurrence of behavior and emotion problems. Specifically, we hypothesized that random assignment to the FCU would result in a greater likelihood of transitions out of patterns of co-occurring emotional and behavioral problems, and into a normative, asymptomatic state from ages 2 to 4. Steps that led to the test of this hypothesis included establishing the number of classes of young children at age 2, 3, and 4, examining the distribution of these classes (using a series of Latent Class Analyses), and then testing the impact of a randomized intervention on class membership and transitions across classes from age 2 to 3, and from age 3 to 4 (using a Latent Transition Analysis).

As expected, results of LCA models supported the existence of four classes at ages 2, 3, and 4 years. These classes appeared to correspond with the internalizing, externalizing, comorbid, and normative groups that were expected on the basis of past research and theory. The LTA model provides important details regarding the manner in which youth move across these groups over time, and whether patterns of movement across these groups differ in the intervention and control groups. Several findings from the LTA are important to underscore.

First, LTA results were consistent with the hypothesis that treatment would affect the likelihood of youth transitioning out of early problem-behavior classes and into more normative symptom profiles over time. However, few intervention effects were seen from age 2 to 3, while more pronounced intervention effects were found from age 3 to age 4. From age 2 to 3, the largest differences in transition probabilities across intervention and control groups were seen for youth in the comorbid class at age 2, as intervention appeared to decrease the likelihood of remaining in this class by age 3. However, intervention also appeared to increase the likelihood of transitioning from the age 2 comorbid class into the age 3 internalizing class. It is possible that intervention prior to age 3 may have selectively reduced early behavior problems in this group, but may not yet have had an impact on early internalizing symptoms. It is noteworthy that intervention was offered to families between the ages of 2 to 3, and 3 to 4, so age 3 outcomes are temporary and could change following further intervention between the ages of 3 and 4.

Thus, the age 4 assessments offers a more complete picture of the intervention effects on transitions in youth symptom profiles, and indeed, more pervasive differences in transition probabilities are seen from ages 3 to 4 across the treatment and control groups. Several such differences were found. First, multiple intervention effects were seen for youth with internalizing-only symptom profiles at age 3. Youth with internalizing problems at age 3 were somewhat less likely to transition into the age 4 comorbid class in response to intervention, but were more likely to transition into the normative class by age 4. Indeed, in the control group, no youth transitioned from the internalizing class at age 3 into the normative class at age 4, although more than 20% of youth made this transition in the treatment group. These results indicate that improving parent and family functioning may also be important for youth exhibiting early symptoms of anxiety and depression, alone, and they are consistent with other studies in which the FCU was associated with reductions in internalizing problems in early adolescence (Connell and Dishion 2008). Such results support the notion that family-centered interventions are likely to be important for reducing problems with anxiety and depression in youth.

Similar intervention effects were seen for youth with co-occurring internalizing and externalizing symptoms at age 3. In the control group, youth with co-occurring symptoms at age 3 were disproportionately likely to show reduced internalizing problems by age 4, transitioning into the externalizing-only class. These youth were also disproportionately unlikely to transition into the normal class by age 4—indeed no youth in the control group transitioned from the comorbid class at age 3 into the normative class at age 4. In the intervention group, however, nearly 20% of youth in the comorbid class at age 3 transitioned into the normative class at age 4. In a follow-up analysis, the odds ratio for the effect of intervention on transitioning from the comorbid class at age 3 into the normal class at age 4 (relative to any other class) was quite large, although the magnitude of the effect was likely inflated due to the extremely low-likelihood of youth in the control group achieving this transition. Thus, intervention appeared to lead to substantial improvement in functioning for a number of youth exhibiting co-occurring internalizing and externalizing problems at age 3.

These intervention effects for youth—with comorbid symptom profiles are noteworthy because children with early co-occurring emotional and behavior problems may be particularly at risk for continued and serious problems later in development, and are often excluded from intervention studies because of their dual diagnosis. Results of this study indicate that children in the comorbid group may be responsive to early family intervention efforts, showing significant reductions in the likelihood of continued problems. Given that most intervention studies either exclude comorbid cases or focus on only one outcome of interest, it is difficult to fit the findings of this study in with the general prevention or child clinical literature. It would be very helpful if future research on intervention outcome focused on multiple domains (e.g., depression, conduct problems) to evaluate the overall effectiveness of diverse interventions on child and adolescent mental health, more broadly conceptualized.

These results are in line with the limited number of past intervention studies (e.g., Beauchaine et al. 2000, 2005; Kazdin and Whitley 2006) in finding that youth with co-occurring emotional and behavior problems appear to be particularly responsive to early parent-focused intervention. Such results support the notion that these youth are particularly likely to be experiencing substantially disrupted family relationships (e.g., Thomas and Guskin 2001), and thus may be particularly likely to benefit from intervention efforts designed to improve family functioning. Further research is needed to examine mediating processes relative to the intervention and their association with the onset and course of comorbid emotional and behavioral problems in childhood. Consistent with past research involving this sample (Dishion et al. 2008), we suspect that improvements in family functioning, such as increased parental warmth and proactive structuring, will mediate the effects of intervention on the likelihood of exhibiting comorbid problems by age 4. Methodological work is needed, however, to facilitate the analysis of mediation in LTA. Additional research on the etiology of comorbid emotional and behavior problems is also needed in order to facilitate the development of preventive interventions better targeting the needs of youth with such clinical presentations. For instance, drawing from theories of the temperamental and motivational bases of early emotional and behavior problems, Hawes and Dadds (2005) hypothesized that youth with co-occurring internalizing and externalizing problems may be more sensitive than are youth with pure conduct problems to improvements in parental discipline in parenting interventions (rather than improvements in positive reinforcement skills), as these youth may be more sensitive to punishment cues. Although preliminary evidence from a small scale intervention study with 4–8 year olds supported this hypothesis (Hawes and Dadds 2005), additional research is needed to further examine the unique needs of this group of youth.

A second larger finding that is underscored by the current results is that “psychopathology” in early childhood appears to be a moving target, as there were substantial differences in the number of youth exhibiting different symptom profiles across ages. In particular, in both the intervention and control groups, there were large declines in the number of youth showing externalizing-only symptom profiles. Indeed, nearly one-half of youth described by parents as showing early conduct problems were no longer showing such problems by age 4, a rate of decline that was similar across intervention and control groups. This pattern of findings is consistent with that of other research (e.g., Cote et al. 2006; NICHD Early Child Care Research Network 2004), suggesting that early problems with aggression may abate for many youth (although other forms of early conduct problems may persist). Internalizing problems also appeared to show normative declines from age 2 to 3, with more than 35% of youth in both the intervention and control groups moving from the age 2 internalizing class into the normative class at age 3. Conversely, there were large increases in the number of youth moving into the normative class from ages 2 to 4, although the increase was more pronounced in the intervention versus control condition, with a nearly 10% greater percentage of youth in the normative class at age 4 in the intervention versus control group. Taken together, these results suggest that parental views of emotional and behavior problems in early childhood are extremely dynamic, a finding which is in line with the sometimes stressful nature of the normative developmental transitions that take place across this important age range (e.g., Fagot and Kavanagh 1993; Shaw et al. 2000). Parents may take some solace in the current findings, which highlight that for many youth, the emotional and behavioral problems shown in this developmental transition may be relatively transient.

It is important to note that significant intervention effects were not found for the externalizing-only class, either from age 2 to 3, or from age 3 to 4. Despite the fact that the FCU was originally designed to prevent early conduct problems, the externalizing class was the only high-risk latent class that did not demonstrate such intervention effects. One possible reason for this lack of effect is that many moved out of this class and into the normative class regardless of assignment to treatment or control condition. It may be difficult to demonstrate a sizeable intervention effect in the face of substantial normative transitions away from such problem behaviors in early childhood. The current findings may also qualify prior results for this sample (Dishion et al. 2008; Shaw et al. 2008), in which LGM was used to document that children whose parents participated in the FCU exhibited greater declines in externalizing problems from age 2 to age 4 relative to those in the control group. The current LTA results suggest that those intervention effects on changes in externalizing problems may have been primarily driven by children exhibiting co-occurring emotional and behavior problems rather than by those with only early behavior problems.

Limitations

Several limitations to the current study merit consideration. First is the issue of potential rater bias, as we relied on mothers reports of children’s externalizing and internalizing problems. Mothers were not blind to their randomization to either the intervention or the control group, and it is possible that group differences are partially responsible for perceived changes in child problem behavior. Clearly, it would be helpful to have independent raters of youth symptoms, and future planned assessments with these children as they enter school age will include teacher and after-care provider reports in order to shed light on the extent to which improvements in problem behavior are found across independent raters in multiple settings. Although we recognize potential rater bias as a concern, we also wish to highlight that Dishion et al. (2008) recently found that observed parenting behaviors mediated intervention-related improvements in mother-rated behavior problems in this sample. This finding supports the notion that maternal reports of improved behavior are significantly related to independently observed improvements in family functioning, and minimizes the likelihood that these improvements in youth behavior are simply due to the reliance on maternal reports.

Second, particular scales were not highly discriminating across groups in the models. The measurement probability parameters range from 0 to 1, and probabilities closer to the extremes indicate scales which more clearly differ across classes. We see reasonably clear discrimination across the comorbid and normative classes, for most scales. For the internalizing and externalizing classes, however, there is somewhat less discrimination, especially for particular scales. For instance, youth in both the internalizing and externalizing classes are similarly likely to show significant signs of social withdrawal. This finding suggests that the scale may not be a clear indicator of early internalizing problems, as it is currently considered in the CBCL scoring system, but rather may be a more general sign of problems at this age. Such results point the potential need to refine our understanding of early symptom profiles and for careful research into the manner in which symptom profiles may change across development.

Third, it is worth highlighting that one possible outcome of the FCU is that families could receive referrals to outside service providers. Unfortunately, we did not gather data about the extent to which families followed through on referrals. It is possible that these referrals may contribute to the intervention effects we see in the current study. Finally, although we presented evidence to suggest that the FCU leads to improvements in child problem behavior, effect sizes, albeit meaningful from a public health perspective, were relatively modest. Further refinement of the FCU will be needed to increase its efficacy.

Implications and Future Directions

This study’s findings corroborate previous evidence that longitudinal changes in child emotional and behavioral difficulties can be achieved with a brief family-centered intervention. The changes observed in our study were achieved among low-income families participating in an existing, nationally available service delivery setting (WIC). Such families with children at risk for early-starting pathways of externalizing behavior rarely use mental health services (Haines et al. 2002). We hope that future follow-up of the present cohort will clarify concerns regarding the intervention’s endurance and generalizability to other contexts.

Contributor Information

Arin Connell, Email: arin.connell@case.edu, Department of Psychology, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH, USA.

Bernadette Marie Bullock, Child and Family Center, University of Oregon, Eugene, OR, USA.

Thomas J. Dishion, Child and Family Center, University of Oregon, Eugene, OR, USA

Daniel Shaw, Department of Psychology, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, USA.

Melvin Wilson, Department of Psychology, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA, USA.

Frances Gardner, Department of Social Policy and Social Work, Oxford University, Oxford, UK.

References

- Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Manual for the ASEBA preschool forms & profiles. Burlington VT: University of Vermont Department of Psychiatry; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Angold A, Costello EJ, Erkanli A. Comorbidity. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1999;40(1):57–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asarnow JR, Carlson G. Suicide attempts in preadolescent child psychiatry inpatients. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 1988;18(2):129–136. doi: 10.1111/j.1943-278x.1988.tb00147.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asarnow J, Scott C, Mintz J. A combined cognitive–behavioral family education intervention for depression in children: A treatment development study. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2002;26:221–229. [Google Scholar]

- Beauchaine TP, Gartner J, Hagen B. Comorbid depression and heart rate variability as predictors of aggressive and hyperactive symptom responsiveness during inpatient treatment of conduct-disordered ADHD boys. Aggressive Behavior. 2000;26:425–441. [Google Scholar]

- Beauchaine TP, Webster-Stratton C, Reid MJ. Mediators, moderators, and predictors of 1-year outcomes among children treated for early-onset conduct problems: A latent growth curve analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73:371–388. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.3.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brent D, Holder D, Kolko D, Birmaher B, Baugher M, Roth C, et al. A clinical psychotherapy trial for adolescent depression comparing cognitive, family, and supportive therapy. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1997;54:877–885. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830210125017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briggs-Gowan M, Carter A, Bosson-Heenan J, Guyer A, Horwitz S. Are infant–toddler social–emotional and behavioral problems transient? Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2006;45:849–858. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000220849.48650.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briggs-Gowan M, Carter A, Irwin J, Wachtel K, Cicchetti D. The Brief Infant–Toddler Social and Emotional Assessment: Screening for social–emotional problems and delays in competence. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2004;29:143–155. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsh017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinkmeyer MY, Eyberg SM. Parent–child interaction therapy for oppositional children. In: Kazdin AE, Weisz JR, editors. Evidence-based psychotherapies for children and adolescents. New York: Guilford; 2003. pp. 204–223. [Google Scholar]

- Brook JS, Whiteman M, Finch S. Childhood aggression, adolescent delinquency, and drug use: A longitudinal study. Journal of Genetic Psychology. 1992;153:369–383. doi: 10.1080/00221325.1992.10753733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell SB, Pierce EW, Moore G, Marakovitz S, Newby K. Boys’ externalizing problems at elementary school age: Pathways from early behavior problems, maternal control, and family stress. Development and Psychopathology. 1996;8:701–719. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell SB, Shaw DS, Gilliom M. Early externalizing behavior problems: Toddlers and preschoolers at risk for later maladjustment. Development and Psychopathology. 2000;12:467–488. doi: 10.1017/s0954579400003114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi D. Co-occurrence of conduct problems and depressive symptoms in early adolescent boys II: A two-year follow-up at grade eight. Development and Psychopathology. 1992;4:125–144. doi: 10.1017/s0954579499001959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Newman DL, Silva PA. Behavioral observations at age 3 years predict adult psychiatric disorders: Longitudinal evidence from a birth cohort. In: Hertzig ME, Ellen EA, editors. Annual progress in child psychiatry and child development. Philadelphia, PA: Brunner/Mazel; 1998. pp. 319–331. [Google Scholar]

- Collins L, Hyatt S, Graham J. Latent transition analysis as a way of testing models of stage-sequential change in longitudinal data. In: Little T, Schnabel K, Baumert J, editors. Modeling longitudinal and multilevel data: Practical issues, applied approaches, and specific examples. Mahway, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2000. pp. 147–161. [Google Scholar]

- Collins L, Murphy S, Bierman K. A conceptual framework for adaptive preventive interventions. Prevention Science. 2004;5:185–196. doi: 10.1023/b:prev.0000037641.26017.00. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connell A, Dishion T. Reducing depression among at-risk early adolescents: Three-year effects of a family-centered intervention embedded within schools. Journal of Family Psychology. 2008 doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.22.3.574. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connell A, Dishion T, Deater-Deckard K. Variable- and person-centered approaches to the analysis of early adolescent substance use: Linking peer, family, and intervention effects with developmental trajectories. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 2006;52:421–448. [Google Scholar]

- Connell A, Dishion T, Yasui M, Kavanagh K. An adaptive approach to family intervention: Linking engagement in family-centered intervention to reductions in adolescent problem behavior. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75:568–579. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.4.568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costin J, Chambers S. Parent Management Training as a treatment for children with Oppositional Defiant Disorder referred to a mental health clinic. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2007;12:511–524. doi: 10.1177/1359104507080979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cote S, Vaillancourt T, Leblanc J, Nagin D, Tremblay R. The development of physical aggression from toddler-hood to pre-adolescence: A nationwide longitudinal study. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2006;34:71–85. doi: 10.1007/s10802-005-9001-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond G, Reis B, Diamond G, Siqueland L, Isaacs L. Attachment-based family therapy for depressed adolescents: A treatment development study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2002;41:1190–1196. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200210000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ. Cross-setting consistency in early adolescent psychopathology: Deviant friendships and problem behavior sequelae. Journal of Personality. 2000;68:1109–1126. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.00128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Kavanagh K. Intervening in adolescent problem behavior: A family-centered approach. New York: Guilford; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Kavanagh K, Schneiger A, Nelson SE, Kaufman N. Preventing early adolescent substance use: A family-centered strategy for the public middle-school ecology. In: Spoth RL, Kavanagh K, Dishion TJ, editors. Prevention Science. Vol. 3. Universal family-centered prevention strategies: Current findings and critical issues for public health impact; 2002. pp. 191–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Patterson GR. The development and ecology of antisocial behavior in children and adolescents. In: Cicchetti D, Cohen DJ, editors. Developmental psychopathology: Risk adaptation and disorder. 2nd ed. vol. 3. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2006. pp. 503–541. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Shaw DS, Connell A, Gardner F, Weaver C, Wilson M. The family check-up with high-risk indigent families: Outcomes of positive parenting and problem behavior from ages 2 through 4. Child Development. 2008 doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01195.x. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Stormshak E. Intervening in children’s lives: An ecological, family-centered approach to mental health care. Washington, DC: APA; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Fagot B, Kavanaugh K. Parenting during the second year: Effects of children’s age, sex, and attachment classification. Child Development. 1993;64:258–271. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1993.tb02908.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Lynskey MT, Horwood LJ. The effect of maternal depression on maternal ratings of child behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1993;21:245–269. doi: 10.1007/BF00917534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fombonne E, Wostear G, Cooper V, Harrington R, Rutter M. The Maudsley long-term follow-up of child and adolescent depression: I. Psychiatric outcomes in adulthood. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;179:210–217. doi: 10.1192/bjp.179.3.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forgatch MS, Patterson GR, DeGarmo DS. Evaluating fidelity: Predictive validity for a measure of competent adherence to the Oregon Model of Parent Management Training. Behavior Therapy. 2005;36:3–13. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7894(05)80049-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner F. Positive interaction between mothers and conduct-problem children: Is there training for harmony as well as fighting? Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1987;15:283–293. doi: 10.1007/BF00916355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner F. The quality of joint activity between mothers and their children with behaviour problems. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1994;35:935–948. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1994.tb02303.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner F, Shaw DS, Dishion TJ, Supplee LA, Burton J. Family-centered approach to prevention of early conduct problems: Positive parenting as a contributor to change in toddler problem behavior. Journal of Family Psychology. 2007;21:398–406. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.21.3.398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner F, Sonuga-Barke E, Sayal K. Parents anticipating misbehaviour: An observational study of strategies parents use to prevent conflict with behaviour problem children. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1999;40:1185–1196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham J, Collins L, Wugalter S, Chung N, Hansen W. Modeling transitions in latent stage-sequential processes: A substance use prevention example. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1991;59:48–57. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.59.1.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory A, Eley T, Plomin R. Exploring the association between anxiety and conduct problems in a large sample of twins aged 2–4. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2004;32:111–122. doi: 10.1023/b:jacp.0000019765.29768.1c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haines MM, McMunn A, Nazroo JY, Kelly YJ. Social and demographic predictors of parental consultation for child psychological difficulties. Journal of Public Health Medicine. 2002;24:276–284. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/24.4.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawes D, Dadds M. The treatment of conduct problems in children with callous-unemotional traits. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73:737–741. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.4.737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins JD, Lishner DM, Catalano RF, Howard MO. Childhood predictors of adolescent substance abuse: Toward an empirically grounded theory. Journal of Children in Contemporary Society. 1986;18:11–47. [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys K, Janson H. Latent transition analysis with covariates, nonresponse, summary statistics, and diagnostics. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2000;35:89–118. doi: 10.1207/S15327906MBR3501_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin A, Whitley M. Comorbidity, case complexity, and effects of evidence-based treatment for children referred for disruptive behavior. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74:455–467. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.3.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanza S, Lemmon D, Schafer J, Collins L. Proc LCA & Proc LTA user’s guide. University Park, PA: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn PM, Rohde P, Seeley JR. Adolescent psychopathology: III. The clinical consequences of comorbidity. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1995;34(4):510–519. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199504000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn P, Rohde P, Seeley J, Klein D, Gotlib I. Psychosocial functioning of young adults who have experienced and recovered from major depressive disorder during adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003;112:353–363. doi: 10.1037/0021-843x.112.3.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercer S, DeVinney B, Fine L, Green L, Dogherty D. Study designs for effectiveness and translation research: Identifying trade-offs. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2007;33:139–154. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller TR. The social costs of adolescent problem behavior. In: Biglan A, Brennan PA, Foster SL, Holder HD, editors. Helping adolescents at risk: Prevention of multiple problem behaviors. New York: Guilford; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: Preparing people for change. 2nd ed. New York: Guilford; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén B, Muthén L. Integrating person-centered and variable-centered analysis: Growth mixture modeling with latent trajectory classes. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2000;24:882–891. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén B, Muthén L. Mplus user’s guide. 4th ed. Los Angeles, CA: Muthen & Muthen; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- NICHD Early Childcare Research Network. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. vol. 69. Boston, MA: Blackwell; 2004. Trajectories of physical aggression from toddlerhood to middle childhood. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nottelmann ED, Jensen PS. Comorbidity of depressive disorders: Rates, temporal sequencing, course, and outcome. In: Essau CA, Petermann F, editors. Depressive disorders in children and adolescents: Epidemiology, risk factors, and treatment. Lanham, MD: Jason Aronson; 1999. pp. 137–191. [Google Scholar]

- Nylund K, Asparouhov T, Muthén B. Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: A Monte Carlo simulation study. Structural Equation Modeling: An Interdisciplinary Journal. 2007;14:535–569. [Google Scholar]

- Olds DL, Eckenrode J, Henderson CR, Jr, Kitzman H, Powers J, Cole R, et al. Long-term effects of home visitation on maternal life course and child abuse and neglect. Fifteen-year follow-up of a randomized trial. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1997;278(8):637–643. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR, Stoolmiller M. Replications of a dual failure model for boys’ depressed mood. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1991;59(4):491–498. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.59.4.491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Reboussin B, Reboussin D, Liang K, Anthony J. Latent transition modeling of progression of health-risk behavior. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 1998;33:457–478. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr3304_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson E, Eyberg S, Ross A. The standardization of an inventory of child conduct problem behaviors. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1980;9:22–29. [Google Scholar]

- Rohde P, Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR. Psychiatric comorbidity with problematic alcohol use in high school students. Journal of American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1995;35:101–109. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199601000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw DS, Bell RQ, Gilliom M. A truly early starter model of antisocial behavior revisited. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2000;3:155–172. doi: 10.1023/a:1009599208790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw D, Dishion T, Connell A, Wilson M, Gardner F. Maternal depression as a mediator of intervention in reducing early child problem behaviour. Development and Psychopathology. 2008 doi: 10.1017/S0954579409000236. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw DS, Dishion TJ, Supplee L, Gardner F, Arnds K. A family-centered approach to the prevention of early-onset antisocial behavior: Two-year effects of the Family Check-Up in early childhood. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74:1–9. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw DS, Gilliom M, Ingoldsby EM, Nagin D. Trajectories leading to school-age conduct problems. Developmental Psychology. 2003;39:189–200. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.39.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw DS, Gross H. Early childhood and the development of delinquency: What we have learned from recent longitudinal research. In: Lieberman A, editor. The long view of crime: A synthesis of longitudinal research. New York: Springer; 2008. pp. 79–127. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw DS, Owens EB, Vondra JI, Keenan K, Winslow EB. Early risk factors and pathways in the development of early disruptive behavior problems. Development and Psychopathology. 1996;8:679–699. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw DS, Winslow EB, Owens EB, Hood N. Young children’s adjustment to chronic family adversity: A longitudinal study of low-income families. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1998;37:545–553. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199805000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Supplee L, Unikel E, Shaw D. Physical environmental adversity and the protective role of maternal monitoring in relation to early child conduct problems. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2007;28:166–183. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2006.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas J, Guskin K. Disruptive behavior in young children: What does it mean? Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2001;40:44–51. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200101000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vicary JR, Lerner JV. Longitudinal predictors of drug use: Analyses from the New York Longitudinal Study. Journal of Drug Education. 1983;13:275–285. doi: 10.2190/ED66-9J7H-D1LM-B3GG. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren S, Huston L, Egeland B, Sroufe A. Child and adolescent anxiety disorders and early attachment. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36:637–644. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199705000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster-Stratton C. Long-term follow-up of families with young conduct problem children: From preschool to grade school. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1990;19:144–149. [Google Scholar]