Abstract

This article describes a case study in the use of the Family Check-Up (FCU), a family-based and ecological preventive intervention for children at risk for problem behavior. The FCU is an assessment-driven intervention that utilizes a health maintenance model; emphasizes motivation for change; and offers an adaptive, tailored approach to intervention. This case study follows one Caucasian family through their initial assessment and subsequent treatment for their toddler daughter’s conduct problems over a 2-year period. Clinically meaningful improvements in child and family functioning were found despite the presence of child, parent, and neighborhood risk factors. The case is discussed with respect to the findings from a current multisite randomized control trial of the FCU and its application to other populations.

There is growing interest in identifying young children at risk for early and persistent trajectories of antisocial behavior (Shaw & Gross, 2008), motivated by several studies of early-starting antisocial youth (Moffitt, 1993). Several researchers have documented that compared to late starters (who begin delinquent activity in mid-to late adolescence), early starters (who typically initiate antisocial activities before age 10) show a more persistent and chronic trajectory of antisocial behavior extending from middle childhood to adulthood (Moffitt & Caspi, 2001; Patterson & Yoeger, 1993). Early starters represent approximately 6% to 7% of the general population of youth yet are responsible for almost half of all adolescent crime and three fourths of violent crimes (Offord, Boyle, & Racine, 1991). During the past 2 decades, prevention scientists have focused on generating interventions for preventing early-starting pathways from developing, including programs for expectant mothers with first-born children (Olds, 2002) and preschool-age children (Webster-Stratton & Hammond, 1997). However, despite research suggesting that early-starting pathways of antisocial behavior can be identified as early as age 2 to 3 (Shaw, Gilliom, Ingoldsby, & Nagin, 2003), few interventions have focused on the developmental transition of the “terrible 2s,” a time of great maturational change (Shaw & Bell, 1993).

The Family Check-Up (FCU) is a preventive intervention that has been adapted specifically to address the normative challenges parents face during the terrible 2s, particularly in high-risk environments where these normative challenges are more likely to lead to negative outcomes (Dishion et al., in press; Shaw, Dishion, Supplee, Gardner, & Arnds, 2006). Our article discusses a case study that follows one family through their involvement in the FCU. The FCU was initially developed and shown to be efficacious in reducing problem behavior among adolescents (Connell, Dishion, Yasui, & Kavanagh, in press; Dishion & Kavanagh, 2003). However, it has recently been associated with reductions in young children’s conduct problems and internalizing problems, as well as improvements in maternal depression, parental involvement, and positive parenting in two independent, randomly controlled trials (Dishion et al., in press; Shaw, Dishion, Connell, Wilson, & Gardner, 2008). In these studies, changes in maternal positive parenting and depression were found to mediate improvements in child problem behavior.

The FCU model differs from traditional clinical models and practice in three important ways: it utilizes a health maintenance model, derives much of its power from a comprehensive assessment, and emphasizes motivating change. In contrast to the standard clinical model, the health maintenance approach of the FCU explicitly promotes periodic contact with families (yearly at a minimum) over the course of key developmental transitions. Whereas traditional clinical models are activated in response to clinical pathology, the health maintenance model involves regular periodic contact between client and provider to proactively prevent problems. Examples of health maintenance models include the use of semiannual cleanings in dentistry and well-baby check-ups in pediatrics.

Another key difference from traditional clinical practice is the FCU’s explicit focus on providing a comprehensive assessment of child and family functioning. Data obtained from assessments are shared with families in feedback sessions to enhance motivation for change (Miller & Rollnick, 2002). Feedback sessions are often followed by family management meetings (Forgatch, Patterson, & DeGarmo, 2005) to promote change in parenting and child problem behavior. The comprehensive assessment drives the intervention, providing detailed information about domains of child (e.g., negative emotionality, child behavior problems), family (e.g., parental depression, marital quality), and community-level (e.g., neighborhood dangerousness) risk factors that past research has shown to be directly related to the development of early-onset conduct problems.

In addition, there is a primary focus on evaluating caregiving practices through direct observation of parent-child interaction. In the case of the FCU for toddlers, this task is accomplished by having parent–child dyads participate in a series of structured (e.g., clean-up and teaching) and semistructured (e.g., preparing a meal and serving it to the child) tasks. The FCU is also “ecological” in its emphasis on improving children’s adjustment across settings by motivating positive parenting practices and involvement in those settings. Moreover, the comprehensive assessment allows tailoring and adaptation, in that the intervention is “fit” to the family’s circumstances and their desires for more or less or different forms of intervention.

The FCU utilizes two main components to facilitate change: motivational interviewing and family management practices. The motivational interviewing component is based on Miller and Rollnick’s (2002) work using the Drinker’s Check-Up, in which assessment data regarding the negative consequences of alcohol abuse on individual’s work and family life are shared in a feedback interview with clients. This approach has been shown to be as effective as 28 days of costly inpatient treatment for reducing problem drinking in adults (Miller & Rollnick, 2002). In working with families of young children, the FCU feedback session is designed to elicit motivation for the parent(s) to change problematic behavior in their child, which is often achieved by modifying parenting behavior (Forgatch et al., 2005) or aspects of the caregiving context that compromise parenting quality. Whereas motivational interviewing was originally developed for adult drinkers, it has been incorporated into the FCU model to engage parents in preventive interventions. In one study of the FCU with parents of adolescents, analyses comparing those adolescents showing significant reductions in substance use and antisocial behavior to those who did not indicated that motivational interviewing was the key strategy for promoting change (Connell et al., in press).

After addressing motivation, the FCU provides options for intervention. The therapist (i.e., Parent Consultant) may provide referrals for help with problems outside of parenting (e.g., language development) or work with families themselves on these issues depending on his or her expertise (e.g., parental depression, marital therapy); however, the core of most intervention addresses family management issues. Family management includes a collective set of parenting skills, commonly referred to as Parent Management Training (PMT), based on social learning principles of reinforcement and modeling (Forgatch et al., 2005; Patterson, 1982; Webster-Stratton & Hammond, 1997). PMT has been consistently associated with improvement in parenting and reductions in child conduct problems (Bullock & Forgatch, 2005; Patterson, Reid, & Dishion, 1992) and has been formally deemed an “empirically supported treatment” (Chambless & Ollendick, 2001).

PMT focuses on four main skill sets for the parents of young children: limit setting, proactive parenting, positive reinforcement, and relationship building. Using PMT typically involves providing parents with a rationale to stimulate interest, careful explanation of new skills, and in-session practice using role plays and in vivo practice with the child. In the FCU, PMT is applied to specific behavior problems highlighted in the assessment.

THE FCU IN THE EARLY STEPS MULTISITE STUDY

The current case illustrates how the FCU integrates basic research on the developmental antecedents of early-starting pathways with validated methods for effecting change in young children’s conduct problems. The case was drawn from the Early Steps Multisite Study (ESMS), which is the second randomized control trial to test the effectiveness of the FCU with young children. The ESMS is an early intervention project aimed at reducing early-onset conduct problems among high-risk families with toddlers and offers the opportunity to examine the efficacy of the FCU with a nonclinical yet high-risk sample of families whose children are at elevated risk for early-starting conduct problems. The ESMS examines the efficacy of the FCU among 731 low-income families with toddlers recruited between 2002 and 2003 from Women, Infants, and Children Nutritional Supplement programs in the metropolitan areas of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; Eugene, Oregon; and Charlottesville, Virginia. The current case was recruited from the Pittsburgh site.

Families were approached at Women, Infants, and Children Nutritional Supplement offices and invited to participate if they had a son or daughter between 2 years 0 months and 2 years 11 months of age, following a screen to ensure that they met the study criteria by having socioeconomic, family, and=or child risk factors for child conduct problems. Families who met the screening criteria and agreed to participate were contacted by research assistants to schedule the initial home assessment. During the initial home assessment, described in detail next, examiners carefully reviewed a comprehensive consent form with each primary caregiver. Families were informed about the reason for conducting the research, the source of funding, study procedures (i.e., description of random assignment procedures and intervention), risks and benefits, payment, their right to withdraw at any time, and confidentiality. Regarding confidentiality, participants were informed that they would not be identified by name in any publication of research results unless they signed a separate form giving their permission.

The FCU

The FCU intervention involves at least three sessions. First is the in-home family assessment. The second session involves rapport building via the Parent Consultant’s (PC’s) initial interview with the caregiver(s), referred to as the Get-to-Know-You (GTKY) visit. The third is a feedback session during which the PC discusses the results of the assessment and initial interview with attention focused on the caregiver’s readiness to change and the delineation of specific change options.

The assessment, which is the first component of the FCU, typically takes place in the family’s home when research assistants visit the family to collect questionnaire and observational data. The assessment, which lasts 2.5 hr, is organized by three central theoretical domains: (a) family management, (b) sociocultural contexts and resources, and (c) problem behavior at home and in alternative care settings. Careful attention was given to selecting measures that could provide useful information in each of the aforementioned domains. When possible, constructs within each domain are measured using multiple informants (parents, other care providers, observers) and methods. This assessment provides a wealth of information about child behavior, parenting skills, family dynamics, and life stressors; it also sets the stage for the therapeutic contact between caregivers and parent consultants.

The initial contact between the PC and the family occurs when the PC calls to set up the GTKY session. At this time, the PC introduces himself or herself, briefly explains the intervention portion of the study, and invites the parent to participate in an introductory meeting and a feedback session. The caregivers’ first session with their PC, the GTKY visit, is usually held in the family’s home. The GTKY visit focuses on developing a collaborative framework for subsequent intervention activities by emphasizing rapport building and exploring concerns with respect to parenting and the family context (Dishion & Stormshak, 2007). Caregivers also provide information about family resources (e.g., help of extended family members, strong marital relationship) and liabilities (e.g., unstable housing, a father who is incarcerated). By the end of this visit, caregivers have discussed their concerns and perceptions of their motivation for change. The PC works to ensure that caregivers feel understood and clarifies discrepancies between caregivers’ goals and current family functioning. Finally, the PC discusses the purpose of the feedback session and how it will be used to review and address caregivers’ identified concerns. For example, given a concern about noncompliance and temper tantrums, the PC will review the assessment with attention to specific strategies that might help improve the cooperation between the caregiver and the child.

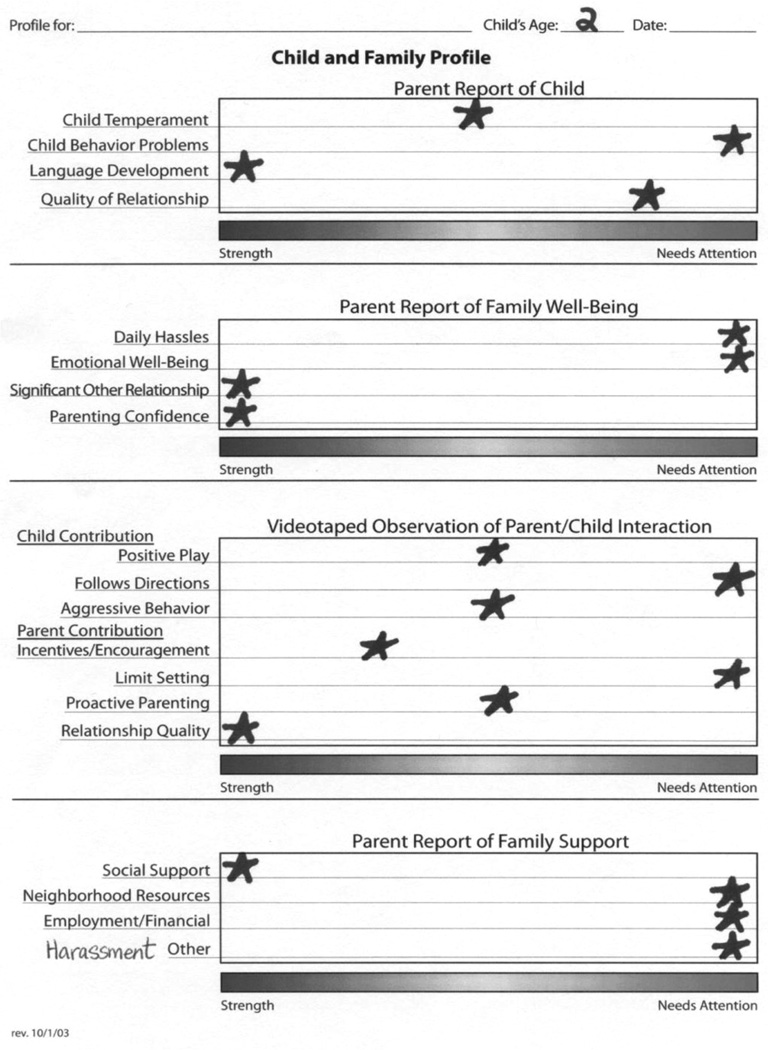

The third session of the FCU, the family feedback session, takes place at the family’s home or at an ESMS office, whichever is preferable to the family. Case conceptualization is a critical feature of the feedback session and is informed by both the assessment and GTKY visit. Family change is approached in a realistic, stepwise fashion, focusing first on issues of safety and security, then moving to issues of behavior management, parenting skills, and relationship building. The feedback session involves a delicate balance among reporting the facts about strengths and problems, building motivation for change, and maintaining rapport with parent(s). The feedback session is a collaborative process, one in which the PC delivers the factual information from the assessment and frequently checks in with parents about their perspectives (see Figure 1). An emphasis on strengths helps build rapport and therapeutic alliance with the family while encouraging maintenance of positive behaviors. Statements about problem areas are framed in a way that reflect the current research findings and in doing so, ground the information in a meaningful way for parents. The PC tailors the feedback material so that it takes into consideration the contextual factors of the family, including cultural variation, child development, family structure, socioeconomics, and community and neighborhood factors.

FIGURE 1.

Child and family profile from age 2.

At the end of the feedback session, the PC discusses a menu of family-based interventions with the caregivers. The intervention options stem from previous work using the FCU and focus groups with parents (Dishion & Stormshak, 2007). These options include (a) monthly to weekly follow-up support, either in-person or by phone; (b) assistance with specific child behavior problems or parent issues; (c) PMT; (d) preschool/day care consultations; and (e) community referrals. The PC encourages the parents to choose the level and type of services that best meet the family’s needs.

BACKGROUND AND REFERRAL

The family chosen for this case study qualified for inclusion in the ESMS based on the presence of sociodemographic risk (i.e., low income and educational attainment), child risk (i.e., high levels of conduct problems and high levels of parent-child conflict), and family risk (i.e., elevated maternal depressive symptoms and parenting hassles). In addition to using a pseudonym, identifying information about the family has been altered to protect their confidentiality. At the time of the age 2 assessment, the Smith family consisted of the mother, a 34-year-old Caucasian female; the father, a 36-year-old Caucasian male; and five children living in the home (ranging from 11 months to 15 years). The Target Child (TC) is their daughter who was 2 years old. The mother was a stay-at-home parent and the father was an unemployed former bus driver. Neither parent held a high school diploma. This marriage was the mother’s third with multiple children by each husband, including two children with her current husband. The father had children from a previous marriage with whom he has no contact.

ASSESSMENT

The mother and TC participated in a home-based assessment, during which the mother completed questionnaires about TC’s behavior and her own well-being. Well-established measures were used when possible (see Table 1), and PCs were trained to code the videotaped tasks using an observation manual (Veltman et al., 2003) derived from research with families from similar high-risk environments (e.g., Shaw et al., 2003). Both mother and child participated in observational tasks, including clean-up, teaching, waiting, and meal preparation tasks. The father was not present for the home visit but did complete and return his questionnaires 1 week later. Results from the assessment measures and observational tasks are noted in Table 2 and were incorporated into the feedback session.

TABLE 1.

Summary of Measures Used

| Measure | Description/Factors Used | Type of Measurement and Reporter | Cutoffs/Norms | Internal Consistencies (α)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Center for Epidemiological Studies on Depression Scale (Radloff, 1977) |

Depression | Self Report-Mother; 4-point Likert |

0–8 Normative 9–15 At risk 16–60 Clinical |

.75–.77 |

| Eyberg Child Behavior Inventory (Robinson et al., 1980) |

Problem (Is the behavior a problem for you?) Intensity factor |

Mother report of child’s behavior |

4.6–7.0 Normative 3.1–4.6 At risk 1–3.1 Clinical |

.84–.94 |

| Child Behavior Checklist−1.5–5 (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2000) |

Total Problems Externalizing Internalizing |

Mother report of child’s behavior; 3-point Likert |

<60=Normative 60–65= Borderline >65=Clinical |

.86–.89 .82–.91 |

| Marital Adjustment Test (Locke &Wallace, 1959) | Marital relationship | Mother report of mother/child relationship; 5-point Likert |

48–74 Normative 40–47 At risk 13–39 Clinical |

.72–.74 |

| Parenting Daily Hassles (Crnic &Greenberg, 1990) | Typical everyday events parents encounter with children |

4-point Likert of frequency & 5-point Likert of how hassled the parent feels |

20–42 Normative 43–54 At risk 55–100 Clinical |

.86–.89 |

| McArthur Communicative Development Index-Short Form Vocabulary Checklist (Fenson et al., 2000) (age 2) |

Language knowledge | Parent report of words the child has used compared to standardized norms |

100th–31st% Normative 30th–11th% At Risk 0–10th% Clinical |

N/A |

| Therapist Video Observationsb | ||||

| Measure | Factors | Components of Score | ||

| Child Behavior | Positive play | Persistence in task, respectful with property, exhibits neutral to positive affect, asks for assistance, shared affect with caregiver. |

||

| Child follows directions | Percentage of time child complies with caregiver. | |||

| Aggressive behavior | Difficulty following social rules. | |||

| Parenting | Incentives and encouragement | Facilitates child’s focus & persistence, talks to child, offers positive/supportive comments, gives nonverbal support (hugs, smiles), rewards positive behavior. |

||

| Limit setting | Sets limits effectively, follows through with limits sets, displays appropriate response to child behavior. |

|||

| Proactive parenting | Aware and responsive, anticipates needs and organizes activities & transitions in advance, gives appropriate choices. |

|||

| Relationship Quality | Global mother/child quality | Interacts fully, consistently with child, conveys acceptance/approval, creates friendly/peaceful atmosphere with child, allows child to take the lead. |

||

All internal consistencies reported are from the entire ESMS study from ages 2 to 4.

Most subscales rated on a 9-point Likert scale (from never to always) after watching the entire home visit interaction. A more detailed description of coding with operational definitions for coding can be found in Veltman et al. (2003). Note specifics for “age-appropriate” behavior change slightly at each age as children are expected to act differently to be in the “normative” range.

TABLE 2.

Selected Summary of Evaluation and Outcomes of Areas of Strength and Concern

| Age 2 | Age 3 | Age 4 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measure | Score | Clinical Range |

Score | Clinical Range |

Score | Clinical Range |

|

| Areas of Concern | |||||||

| Maternal Depression | Center for Epidemiological | 28 | Clinical | 21 | Clinical | 9.5 | Normative |

| Studies on Depression | |||||||

| Scale | |||||||

| Child Behavior | Eyberg Child Behavior | 3.8 | At risk | 4.9 | Normative | 4 | At risk |

| Inventory | |||||||

| Child Behaviora | Child Behavior | ||||||

| Externalizing | Checklist −1.5–5 | 73 | Clinical | 57 | Normative | 59 | Normative |

| Internalizing | 61 | At risk | 53 | Normative | 49 | Normative | |

| Total Problems | 69 | Clinical | 53 | Normative | 54 | Normative | |

| Parent Stress | Parenting Daily Hassles | 71 | Clinical | 41 | Normative | 50 | At risk |

| Areas of Strength | |||||||

| Marital Relationship | Marital Adjustment Test | 57 | Normative | 57 | Normative | 64 | Normative |

| Parenting Confidence | Parenting Sense of Competence Scale |

92 | Normative | 81 | Normative | 74 | Normative |

| Child Language | McArthur Communicative Development Index (age 2 only) |

96 words (70th %ile) |

Normative | ||||

| Therapist Video Observations | |||||||

| Child Positive Play | At risk | Normative | Normative | ||||

| Child Follows | Clinical | Normative | Normative | ||||

| Directions | |||||||

| Child Aggressive | At risk | At risk | Normative | ||||

| Behavior | |||||||

| Parent Incentives and Encouragement |

At risk | At risk | At risk | ||||

| Parent Limit Setting | Clinical | Normative | Normative | ||||

| Proactive Parenting | At risk | At risk | Normative | ||||

| Relationship Quality | Normative | Normative | Normative | ||||

The scores listed are T scores.

GTKY Visit

Both parents were present for the GTKY at age 2. The mother was very talkative during the 1-hr interview. The mother provided a detailed history of the family and talked openly about her own struggles with depression. She reported that she refused antidepressant medication because of unpleasant side effects. She also talked about an ongoing source of familial stress: severe harassment by her second ex-husband despite the procurement of several Protection from Abuse orders. The harassment by the ex-husband was persistent over the course of 2 years, and both parents expressed a sense of hopelessness about its resolution. In addition, the family lived in a high-crime neighborhood, as described by both parents and observed by the PC and assessment team. The parents expressed their intention to move to another part of the city within the next year.

When asked about the TC, the mother reported concerns about the child’s developmental progress and the father reported that she had a “bad attitude.” When asked about the TC’s behavior problems, both parents agreed that it was “her anger.” Both parents reported that TC had a “quick temper and lashes out,” hit her siblings, and yelled frequently. The parents also agreed that she had an “emotional problem,” referring to her temper tantrums. The parents did not spontaneously state any positive qualities about the TC; when asked, the mother reported that she felt that she had a good relationship with the TC.

Feedback Preparation and Case Conceptualization

Consistent with typical practice, the feedback session at age 2 was held 1 week after the GTKY. The PC used videotaped and questionnaire data from the assessment to prepare a Child and Family Profile (see Figure 1) designed to visually represent the child’s and family’s strengths and areas of concern. Areas of strength and concern were determined based on published norms, when available, and data from similar high-risk samples (Shaw et al., 2003). At a broader level, components of the data were used to generate a conceptualization of the family’s strengths and challenges so the review follows a logical storyline for the parents.

In the FCU process, the PC prepares a comprehensive report about the family’s and child’s strengths and potential problems based on the assessment. Scoring the Smith’s assessment measures revealed a number of strengths, including that the mother and father viewed their marital relationship positively and were willing to participate in the feedback session. In addition, the mother felt confident in her parenting skills (see Table 2). When coding the observational tasks, the PC observed that the mother was responsive to her daughter’s bids for positive attention and demonstrated a warm and affectionate relationship with her. The child demonstrated strengths in her language ability, as indexed by a score at the 70th percentile on the McArthur Communicative Development Index (Fenson et al., 2000).

Several areas of concern were evident, most notably the TC’s level and breadth of problem behavior and the mother’s level of depressive symptoms. According to mother’s report on two different measures of child behavior, the TC was well into the clinical range for both internalizing and externalizing problems (see Table 2). Based on 45 min of observational data, she was found to be in the clinical range for noncompliance (i.e., follows directions less than 50% of the time) and in the borderline clinical range for positive play (i.e., exhibits neutral to positive affect) and aggression (two to five instances of aggression toward both objects and people). Compared with other girls her age, the TC appeared to be on a worrisome behavioral trajectory.

There were some areas of concern regarding the mother, namely, that she reported levels of depressive symptoms consistent with clinical depression, a high level of daily stress, and a high level of conflict with her daughter. Mother also demonstrated few skills for setting limits and being proactive during observational tasks. The family’s residence in a high crime neighborhood was also seen as an important factor that impacted their level of stress (see Table 2).

The combined clinical picture for the TC and mother suggested that there were deficits in parenting skills, perhaps because of the mother’s depressive symptomatology and daily stress, which contributed to the child’s behavioral and emotional problems. In addition, the child was demonstrating high levels of behavioral and emotional problems, which were posited to contribute to coercive cycles of interaction with her mother (Patterson, 1982). A related concern was that if the mother and child did not find more positive ways to interact, both child and maternal behavior would become exacerbated, moving the child into a more entrenched and less malleable trajectory of problem behavior. Interventions aimed at improving these areas could capitalize on existing family strengths, namely, the positive marital relationship, parental willingness to participate, and TC’s language skills. The family’s high crime neighborhood and harassment from the ex-husband were also noted on the Child and Family Profile and incorporated into the feedback session, reflecting the family’s particular needs and context.

FEEDBACK SESSION

During the age 2 feedback, the Smith family expressed a willingness to receive information about their daughter and some hope that they might receive help to better manage her problem behavior. After a brief rapport-building introduction, the PC began the feedback session and asked the self-assessment questions (“Over the course of the assessment, what did you learn about TC? What stood out for you?”). Both parents responded by stating that their child “behaves better when other people are around.” The PC clarified that the mother believed that the videotaped portions of the assessment reflected better-than-usual behavior from the TC. After orienting the parents to the FCU profile and explaining the feedback process, the PC discussed the identified areas of strength and concern (see Figure 1).

Child Behavior

The Child and Family Profile begins with a focus on child behavior in an effort to align parents with a shared focus about their child’s well-being. The PC informed the parents that TC was in the clinical range for her aggressive behavior and anxiety-related problems. The mother’s initial response to this information was to elaborate on the areas where TC was aggressive, in particular with her siblings. When the PC asked the mother about her biggest concerns related to TC’s fights with siblings, she initially minimized the problem by stating that TC would probably outgrow her aggressive behavior. The PC agreed that this was a possibility (rolling with resistance) and then inquired about alternate outcomes. When invited by the PC to consider what would happen if TC did not “outgrow” the problem, the mother admitted to her fears that TC and siblings might seriously hurt each other “by accident.”

Mrs. Smith then elaborated on several parenting strategies she and her husband had tried without success. The PC affirmed their efforts and then offered a normalizing statement about the parents’ struggles with TC. Next, the PC discussed the potential usefulness of additional or new parenting strategies to address TC’s problem behavior. The PC also provided information about TC’s likely behavioral trajectory (i.e., behavior problems would likely get worse) and the benefits of early intervention versus “wait and see.” The PC utilized observational data about TC’s observed defiance and noncompliance to underscore the seriousness of the concerns about her conduct problems. In addition, the PC and parents discussed TC’s fearfulness and anxiety, as reported by the mother and observed by the PC. The mother and father expressed moderate concern here and were able to identify some ways in which TC’s fearfulness is a problem for them, including her “clinginess” and inability to sleep through the night in her own bed.

PC also reported on TC’s strengths, most notably her language skills and positive affect when spending time with her mother. TC’s language development was presented as a positive indicator of her ability to learn new behavior and respond to her parent’s requests. In addition, the PC worked to enhance the parent’s understanding that a positive relationship with their daughter could motivate their daughter to change her behavior.

Parent Behavior

When reviewing the profile sections on parent wellbeing, the PC informed the parents that the mother’s scores on self-report measures were indicative of clinical depression. The PC expressed concern about the severity of the mother’s depressive symptoms, and when PC inquired about them, the mother began to cry and stated that she “didn’t want to talk about it.” The PC acknowledged that it would be difficult to parent when feeling so depressed. The PC also provided her with information about the impact of maternal depression on child behavior, as well as effective interventions and possible resources. Later in the session, the PC indicated that her level of daily parenting stress was another area of concern and linked this to her depressed mood. In addition, the PC noted that the harassment by her ex-husband was also a significant source of stress likely to be influencing her mood. The mother agreed to look into intervention for her depression and stated her intention to resolve the situation with her ex-husband.

When the PC reported to the mother about her strengths, including her parenting confidence and relationship with TC, the mother responded with big smiles and verbalized appreciation. Acknowledgment of her strengths provided the mother with the opportunity to verbally elaborate on her positive skills and to express how much she values the relationship she has with her daughter and husband. Furthermore, the PC invited the parents to elaborate on the strengths of their marital relationship, stating that the qualities they mentioned (e.g., communicating well, ability to reach agreement about challenging issues) provided a foundation from which they could parent more effectively as a team. The PC highlighted parent strengths with the aim of supporting parental efficacy and instilling hope for successful behavior change.

Summarizing and Goal-Setting

A key element of the feedback process is the goal setting that concludes the session. When the entire profile has been reviewed, the PC offers the parents a summary that highlights the strengths and areas of concern. In this case, the PC revisited the concerns about the mother’s depressive symptoms and linked them to other areas of stress and challenges in parenting. The PC also highlighted the parents’ concerns about TC’s behavior problems and noted the congruence with the observations of noncompliance and defiance. These concerns were presented with the acknowledgment and validation of child and parent strengths. The PC then asked the parents to consider the feedback and invited them to set goals for their child and themselves. They set three goals: (a) for the family to move to a new neighborhood that was safer and removed from the ex-husband, (b) for the mother to meet with a psychiatrist to discuss antidepressant medication and other intervention options, and (c) for the parents to work with their daughter to reduce her temper tantrums and aggressive behavior.

INTERVENTION

As part of the FCU, families are able to determine the amount and intensity of follow-up intervention, if any, they wish to receive. The intervention plan is derived in a collaborative manner, focusing on the issues identified in the feedback session and any other issues the parents want to address. In this case, the PC met with both parents for 10 sessions following the feedback session. Sessions were scheduled for every other week.

Early sessions focused on the mother’s depressive symptoms and harassment from her ex-husband. With regard to nonparenting issues, clinicians using the FCU model typically respond in a manner consistent with standard clinical practice, for example, utilizing cognitive behavioral techniques to deal with depression, offering advocacy and creating a safety plan for domestic violence. Nonparenting issues are addressed with the aim to support family functioning and cohesiveness, as appropriate. For example, a common service PC’s provide is referral and advocacy for accessing community resources. The FCU model works to facilitate connection with services in a family’s community to increase their network of support and self-sustainability. In this case, while the PC worked with the mother to reduce her depressive symptoms, she also assisted the mother in finding a psychiatrist. Regarding the harassment from the mother’s exhusband, the PC explored possible responses with both parents. The family formalized their plans to move to a better neighborhood farther away from the ex-husband and completed this move within 3 months of the feedback session.

Once these initial issues were addressed, the mother expressed willingness to work on TC’s disruptive behavior. Specifically, she was interested in reducing the number of fights her children had during the day and increasing TC’s compliance. Over the course of the next seven sessions, the PC explored TC’s problem behaviors and their associated patterns with both parents by using several tools. These included the Good Behavior Game (Dishion & Patterson, 1996); the use of incentives, praise, and encouragement; troubleshooting problem areas; and teaching the proper administration of a Time Out.

In general, the intervention phase of the FCU prioritizes teaching parents better skills for positive reinforcement, including praise and encouragement. When parents choose to focus on parenting skills, the PC typically spends about 45 min on the chosen skill area, with the additional 15 min of the session addressing nonparenting concerns and generating a plan of action. Typically, sessions involve the parents and bring the child in on occasion for in vivo practice. For each content area, which in this case included incentives, praise and encouragement, and limit setting, the intervention followed a typical process: (a) providing parents with the rationale for the new skill; (b) having the PC demonstrate the new skill to parents; (c) having parents practice the new skill in session with role plays and making corrections; (d) assigning parents homework; and (e) reviewing homework, successes, and challenges during the next visit. This model is drawn from PMT (Bullock & Forgatch, 2005).

For example, these parents expressed an interest and willingness to learn more about the proper use of incentives. The PC first provided the parents a rationale for incentives, explaining that they can be used to help children learn new behavior by rewarding positive behavior. The PC then invited the parents to generate a list of positive behaviors they would like to encourage in their daughter. Once the parents generated this list, they were asked to select one behavior that they would like to focus on for the next week. The PC then invited the TC into the room and demonstrated to the parents how a sticker could be used to encourage positive behavior. The PC provided parents with stickers and asked them to practice this, thus clarifying an effective way to explain and introduce the behavior to the TC.

Another tool used to encourage good behavior is The Good Behavior Game. The Good Behavior Game promotes prosocial behavior among young children by (a) asking the parent to tell their children that they can earn a reward if they can play nicely for 10 min (with use of a timer), (b) establishing and describing reasonable and motivating rewards, (c) carefully explaining what “play nicely” means, (d) asking children to repeat back the instructions, and (e) using a sticker chart to keep track of children’s positive play. In sum, the PC provided information about motivating children, the benefits of praise and encouragement, the role of parent involvement, and key components of proactive parenting. In addition, the PC introduced the book Preventive Parenting with Love, Encouragement and Limits (Dishion & Patterson, 1996) and provided ESMS project-based brochures and informational materials.

FOLLOW-UP

Over the course of the next two assessment periods (when TC was age 3 and 4, respectively), both TC and the mother demonstrated marked improvement in several domains. At the age 3 assessment, TC’s behavior had improved to the extent that she was no longer in the clinical range for either the internalizing or externalizing scales on the Child Behavior Checklist, improvement that was maintained at the age 4 assessment. In addition, the mother’s Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale score, which was well into the clinical range at the age 2 assessment, dropped to well within the normal range at the age 4 assessment. In addition, observations of parent-child interaction revealed steady and stepwise improvement over the next 2 years, including marked improvements in child noncompliance and aggression, as well as maternal limit setting and proactive parenting (see Table 2).

SUMMARY AND DISCUSSION

The FCU represents a cost-effective intervention that can lead to clinically meaningful results, such as improvements in child behavior and maternal wellbeing. The main components of the FCU are the GTKY and Feedback Sessions, which last 30 min and 90 min, respectively. Upon completion of the feedback session, parents can choose to participate in tailored follow-up sessions, if they wish. Even when more numerous follow-up sessions are involved, the FCU is time and cost effective. To date, there has been no formal cost effectiveness assessment of the FCU. However, compared with other relatively brief and empirically validated interventions for child problem behavior, such as Forgatch’s PMT and Webster-Stratton’s family-based intervention, the FCU appears to require a fewer number of sessions to achieve beneficial effects. Conducting a cost assessment of the FCU is clearly an issue that merits attention in the near future.

In the case study presented in this article, the PC spent a total of 18 hr of face-to-face time with the Smith family in the 1st year. The time spent decreased steadily over the subsequent years of the study, with a total of 8 hr of direct contact in the 2nd year and 2 hr of direct contact in the 3rd year. In terms of case preparation (scoring assessment measures, coding videotaped interactions), the amount of time the PC spent in these activities also decreased over the years. Activities not involving direct service delivery, including case preparation and scoring, required 10 hr of PC time in Year 1, 3½ hr in Year 2, and only 2 hr in Year 3. Thus, once the process is learned and PCs become adept with the process of preparing for feedback sessions, the FCU becomes a potent and brief intervention. In terms of completing the home assessment, research assistants spent an average of 1 hr of travel time in addition to the 2½ hr home visit, for a total of 3½ to 4 hr per assessment. Whereas in actual practice the same individual might be responsible for conducting the assessment and the intervention, the research project elected to have a different person serve these roles.

The FCU was designed to integrate research on risk factors for children’s early conduct problems into an ecological, family-based intervention to prevent problem behavior among high-risk families with toddlers. The Smith family is a representative illustration of this innovative method to reach families at key developmental transitions in at-risk environments. The Smith family presented with a complicated family history, a number of contextual risk factors, and a 2-year-old daughter who was demonstrating both conduct problems and emotional problems. Over the course of the FCU, the family showed improvement in several areas, including parenting and child problem behavior, as well reductions in maternal depression and contextual risk. This is consistent with the research showing that improvements in child conduct problems are accompanied by increases in the mother’s positive parenting and decreases in maternal depression (Dishion et al., in press; Shaw et al., 2008; Shaw et al., 2006).

This family was atypical in one respect—families in the ESMS participate in an average number of 3.7 in-person sessions with the PC per year, including the GTKY and the Feedback sessions, whereas this family engaged in 12 sessions their first year, and then 3 to 4 in the following 2 years. After their 1st year of more intensive involvement, which was consistent with the family’s breadth of risk, the family followed the more typical pattern of direct contact with the PC.

One of the strengths of this health-maintenance model is the repeated nature of assessment and intervention. The FCU model involves yearly “check-ups,” which provide clinicians with the unique opportunity to collaboratively track family and child behavior over time and continue to motivate families to change persistent areas of difficulty. For example, it is not uncommon for a family to minimize problems and decline intervention in the 1st year and then engage in the intervention the next year when they discover that the problem behavior has not changed. With some frequency, during the age 3 GTKY, families are able to acknowledge the reality of a problem situation in their 2nd year that they were “waiting to see” about at the age 2 FCU. It is sometimes the repeated review of data, demonstrating that without intervention these problems persist and often worsen over time that can elicit motivation from parents to take action. This phenomenon is an essential strength of the FCU approach: Through repeated regular contact with families using assessment-driven feedback aimed at motivational change, families who would not usually seek intervention on their own are motivated to change. This change in motivation is particularly important for toddlers at risk for early starting conduct problems based on their high probability of persistence (Shaw et al., 2003; Shaw, Lacourse, & Nagin, 2005). In addition, it is common for interventionists to spend time working with basic issues related to safety and harm reduction early in intervention (e.g., excessive conflict between divorced spouses). We find that this initial work sets the foundation for establishing trust in the PC, for families to be open to viewing their child’s behavior more realistically, and for families’ willingness to learn new child management strategies.

It is important to note that the FCU can be adapted and tailored for use in a range of service settings such as the public school environment or community-based clinic (Dishion & Kavanagh, 2003). For example, interventionists may choose to focus the assessment primarily on school-related behavior or only on the child’s behavior in the home. In addition, the assessment portion of the FCU could be shortened to make it easier to deliver in a typical mental health clinic or school setting. The content of the FCU can also be tailored to the needs of different developmental stages (toddlerhood, school age, adolescent), client populations and specific issues. For example, the FCU has been adapted to examine the health-related behaviors of children transitioning to adolescence, with a particular focus on children’s sleep, emotion regulation, and physical activity. In this “health promotion” version of the FCU, the assessment and follow-up interventions focus on youth’s sleep quality, level of physical activity, and emotion regulation as a set of domains that are relevant for navigating the challenges associated with this developmental stage.

In addition to showing intervention effects on child problem behavior, parenting, and maternal depression, the FCU has been found to be effective for promoting change in a wide range of family structures, cultural backgrounds, and contextual risk factors as well as across a broad range of age groups (Dishion et al., in press; Shaw et al., 2008; Shaw et al., 2006). For example, the FCU is currently being used with older children and adolescents in Oregon and with American Indian families living on a reservation. Perhaps the most novel feature of the FCU is the flexibility it provides clinicians in tailoring interventions to the individual family’s challenges and strengths, as well as to the family’s perception of the child’s problem behavior. By integrating the use of motivational interviewing within an ecological framework and utilizing empirically validated methods for promoting change, the model also fits well with current conceptualizations of developmental psychopathology that recognize multiple risk factors and pathways leading to similar problematic outcomes for children (Richters & Cicchetti, 1993).

One important issue for the use of the information provided in this case study in clinical practice is that family participation might follow a different pattern or level of engagement outside of the research setting. ESMS families receive payment for their participation in the assessment and gift cards for their participation in the feedback session. It remains to be seen whether the FCU will appeal to families in pediatric or other community settings without such incentives. In addition, retention of families over time may be more challenging in a traditional community setting, where staff may not have the time to search for families who have moved or to conduct follow-up phone calls. Presently, the creators of the FCU are considering innovative ways to apply this model more broadly and are working to tailor the assessment and feedback process so that it is more user friendly for both therapists and parents. Ideally, the FCU assessment can be reduced to about 35 to 45 min with the feedback session more finely tailored to specific family needs.

Despite these limitations, we believe the FCU holds much promise for preventing the onset of child problem behavior across developmental status of the child, the type of child problem behavior, the family’s cultural and socioeconomic background, and the setting for contact with families. Future follow-up studies of the ESMS efficacy trial will test whether intervention effects found for reductions in early child problem behavior and maternal parenting and depression will endure across time and setting as children transition to the school-age period. However, as such effects appear to be evident across adolescence for a similar sample of at-risk youth (Connell et al., in press), we are optimistic about the FCU’s effectiveness and use in other settings with other at-risk populations for promoting child and family well-being. Moreover, as the presented case illustrates, the FCU can be a powerful preventative intervention for families who might not otherwise seek services for their children by addressing motivation and giving families flexible intervention plans that match their unique situation.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grant DA16110 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse to the third, fourth, and fifth authors. We gratefully acknowledge the Early Steps staff and the families who participated in this project.

Footnotes

Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf

This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden.

The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material.

Contributor Information

Anne M. Gill, Department of Psychology, University of Pittsburgh

Luke W. Hyde, Department of Psychology, University of Pittsburgh

Daniel S. Shaw, Department of Psychology, University of Pittsburgh

Thomas J. Dishion, Department of Special Education, University of Oregon

Melvin N. Wilson, Department of Psychology, University of Virginia

REFERENCES

- Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Manual for the ASEBA preschool forms and profiles. Burlington: University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bullock BM, Forgatch MS. Mothers in transition: Model-based strategies for effective parenting. In: Pinsof WM, Lebow JL, editors. Family psychology: The art of science. New York: Oxford University Press; 2005. pp. 349–371. [Google Scholar]

- Chambless DL, Ollendick TH. Empirically supported psychological interventions: Controversies and evidence. Annual Review of Psychology. 2001;52:685–716. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connell AM, Dishion TJ, Yasui M, Kavanagh K. An ecological approach to family intervention to reduce adolescent problem behavior: Intervention engagement and longitudinal change. In: Evans S, editor. Advances in school-based mental health: Vol. 2. Kingston, NJ: Civic Research Institute; (in press). [Google Scholar]

- Crnic KA, Greenberg MT. Minor parenting stresses with young children. Child Development. 1990;57:209–217. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1990.tb02889.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Kavanagh K. Intervening in adolescent problem behavior: A family-centered approach. New York: Guilford; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Patterson SG. Preventive parenting with love, encouragement, & limits: The preschool years. Eugene, OR: Castalia; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Shaw DS, Connell A, Wilson MN, Gardner F, Weaver CM. The Family Check Up with high-risk families with toddlers: Outcomes on positive parenting and early problem behavior. Child Development. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01195.x. (in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Stormshak E. Intervening in children’s lives: An ecological, family-centered approach to mental health care. Washington, DC: APA Books; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Fenson L, Pethick S, Renda C, Cox JL, Dale PS, Reznick JS. Short-form versions of the MacArthur Communicative Development Inventories. Applied Psycholinguistics. 2000;21:95–116. [Google Scholar]

- Forgatch MS, Patterson GR, DeGarmo DS. Evaluating fidelity: Predictive validity for a measure of competent adherence to the Oregon Mode of Parent Management Training. Behavior Therapy. 2005;36:3–13. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7894(05)80049-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locke HJ, Wallace KM. Short marital adjustment and prediction tests: Their reliability and validity. Marriage and Family Living. 1959;21:251–255. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: Preparing people for change. 2nd ed. New York: Guilford; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt T. Adolescence-limited and life-course persistent antisocial behavior: A developmental taxonomy. Psychological Review. 1993;100:674–701. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE, Caspi A. Childhood predictors differentiate life-course persistent and adolescence-limited pathways among males and females. Development and Psychopathology. 2001;13:355–375. doi: 10.1017/s0954579401002097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Offord DR, Boyle MH, Racine YA. The epidemiology of antisocial behavior in childhood and adolescence. In: Pepler DJ, Rubin KH, editors. The development and treatment of childhood aggression. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1991. pp. 31–54. [Google Scholar]

- Olds D. Prenatal and infancy home visiting by nurses: From randomized trials to community replication. Prevention Science. 2002;3:153–172. doi: 10.1023/a:1019990432161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR. A social learning approach: III. Coercive family process. Eugene, OR: Castalia; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR, Reid JB, Dishion TJ. Antisocial boys. Eugene, OR: Castalia; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson G, Yoeger K. Developmental models for delinquent behavior. In: Hodgins S, editor. Mental disorder and crime. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1993. pp. 140–172. [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES–D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Richters JE, Cicchetti D. Mark Twain meets DSM–III–R: Conduct disorder, development, and the concept of harmful dysfunction. Development and Psychopathology. 1993;5:5–30. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson E, Eyberg S, Ross A. The standardization of an inventory of child conduct problem behaviors. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1980;16:125–140. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw DS, Bell RQ. Developmental theories of parental contributors to antisocial behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1993;21:493–518. doi: 10.1007/BF00916316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw DS, Dishion TJ, Connell A, Wilson MN, Gardner F. Maternal depression as a mediator of intervention in reducing early child problem behavior. Development and Psychopathology. doi: 10.1017/S0954579409000236. (in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw DS, Dishion T, Supplee LH, Gardner FM, Arnds K. A Family centered approach to the prevention of early-onset antisocial behavior: Two-year effects of the Family Check-Up in early childhood. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74:1–9. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw DS, Gilliom M, Ingoldsby EM, Nagin D. Trajectories leading to school-age conduct problems. Developmental Psychology. 2003;39:189–200. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.39.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw DS, Gross H. Early childhood and the development of delinquency: What we have learned from recent longitudinal research. In: Lieberman A, editor. The yield of recent longitudinal studies of crime and delinquency. New York: Springer; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw DS, Lacourse E, Nagin D. Developmental trajectories of conduct problems and hyperactivity from ages 2 to 10. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2005;46:931–942. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00390.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veltman P, Dishion TD, Shaw DS, Wilson MN, Schlatter AL, Supplee LS, et al. Early Steps Project: Video observation ratings for preschoolers and kindergartners. 2003 Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Webster-Stratton C, Hammond M. Treating children with early-onset conduct problems: A comparison of child and parent training interventions. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1997;65:93–109. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.1.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]