Abstract

Background

Patient satisfaction is an important aspect of patient-centered care, but has not been systematically studied after treatment of nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC), the most prevalent cancer.

Objective

To compare patient satisfaction after treatment for NMSC and to determine factors associated with better satisfaction.

Methods

We prospectively measured patient, tumor and care characteristics in 834 consecutive patients at two centers before and after destruction, excision and Mohs surgery. We evaluated factors associated with short-term and long-term satisfaction.

Results

In all treatment groups, patients were more satisfied with the interpersonal manners of the staff, communication, and financial aspects of their care, than with the technical quality, time with the clinician, and accessibility of their care (p<0.05). Short-term satisfaction did not differ across treatment groups. In multivariable regression models adjusting for patient, tumor, and care characteristics, higher long-term satisfaction was independently associated with younger age, better pre-treatment mental health and skin-related quality of life, and treatment with Mohs surgery (p<0.05).

Conclusions

Long-term patient satisfaction after treatment of NMSC is related to pre-treatment patient characteristics (mental health, skin-related quality of life) as well as treatment type (Mohs) but not related to tumor characteristics. These results can guide informed decision-making for treatment of NMSC.

INTRODUCTION

Non-melanoma skin cancer (NMSC) can be successfully treated with different therapies including destruction (cryotherapy, electrodessication and curettage, laser ablation), radiation, surgery (excision, Mohs surgery) and topical chemotherapeutic agents (5-fluorouracil, imiquimod, 5-aminoleuvonic acid with photodynamic therapy). There is substantial variation in treatment selection in different practice settings1 and insufficient evidence exists to recommend a single treatment as superior to others for most tumors.2-4 Data largely from retrospective studies suggest that recurrence rates are lowest after the most technologically intensive therapy, Mohs surgery, and highest after destruction.2,5-6 Skin-related quality of life improves similarly after Mohs surgery or excision, but does not improve after destruction with electrodessication and curettage.7

In an increasingly patient-oriented health care system, patient satisfaction is an important outcome to guide treatment selection, especially for typically nonfatal conditions such as NMSC. Patient satisfaction can be influenced by numerous variables such as the patient’s perceptions of practitioner competence and communication, financial aspects associated with care, environmental surroundings, and clinical outcome. In addition, patient satisfaction has been associated with several other outcomes including health status, quality of life, adherence to medical advice, and initiation of complaints.8-11

We sought to compare patient satisfaction after the three main treatments for NMSC and to determine pre-treatment patient, tumor, and care characteristics that are associated with better short-term and long-term satisfaction.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Design

Data were obtained prospectively from a cohort of consecutive patients with NMSC diagnosed in 1999 and 2000 at a university-affiliated dermatology practice or the nearby affiliated VA Medical Center. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at both institutions. Potential study participants were identified by daily review of all pathology records at both institutions. NMSCs were defined as those with a final histopathologic diagnosis of basal cell carcinoma or squamous cell carcinoma (including squamous cell carcinoma-insitu). Potential participants were excluded if they were younger than 18 years, if their records were protected because they were employees, or if they had a previous skin cancer diagnosed during the study period. Participants were considered ineligible if they were physically or mentally unable to complete surveys, did not speak English, or had no current address available. Patients were enrolled if they responded to a pre-treatment questionnaire about their health and quality of life.

We restricted the study population to 834 individuals whose tumors were treated by electrodessication and curettage (destruction), excision, or Mohs surgery. If a patient had multiple tumors, he or she was asked to respond only about therapy of the most bothersome tumor, and data are reported only about this tumor and its care.

Data Collection and Measures

Data were obtained from medical records and patient surveys. Using structured data-forms, trained research staff collected data from clinical notes and pathology records. Clinicians were categorized according to level of training, as attending physicians, resident physicians, or nurse practitioners.

Socioeconomic characteristics, co-morbid illnesses, tumor-related quality of life, and health status were measured before therapy from patients’ answers to a mailed survey. Comorbidity was measured by an adapted version of the Charlson index.12-13 Tumor-related quality of life was measured with the 16-item version of Skindex.14 We used a composite score calculated as the mean of the three Skindex subscale scores.7 We also inquired about pre-treatment concern about scar and worry about the treatment. Health status was measured with an adapted version of the Medical Outcomes Study SF-12 instrument15 which reported a Physical Component Score (PCS) and a Mental Component Score (MCS). In evaluating these scores, higher is healthier and 50 is the mean norm-based standardized score.

Short-term patient satisfaction was measured one week after therapy with the 18-item version of the Patient Satisfaction Questionnaire (PSQ-18),16 adapted for the treatment of skin cancer. The PSQ-18 assesses general satisfaction as well as satisfaction with six domains of care during a medical visit. Patients responded about how strongly they agreed or disagreed with statements about technical quality, interpersonal manner, communication, financial aspects of care, time spent with clinician, and accessibility of care. For each question, scores varied from 1 to 5; for overall satisfaction and the domains of care, higher scores indicate increased satisfaction with medical care.

To measure long-term satisfaction (after scar remodeling was complete), patients responded at 12 months after therapy to a single global question, “I am completely satisfied with the treatment of my skin problem.” This item was derived from the general satisfaction items of the PSQ-18; scores varied from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). We used a global item because we reasoned that after a year, patients would likely remember overall impressions rather than the details of their experience.

Statistical Analysis

Based on previous work about patient satisfaction and our clinical experience, we hypothesized that long-term satisfaction would be best for older, married patients, those with better pre-treatment skin-related quality of life and mental health status, those treated at the VA, and those treated with Mohs surgery. 9-10,17-19

We compared baseline clinical features in the three treatment groups using either a Chi-square test or a Fisher’s exact test, as indicated by number of subjects per cell. A one-way ANOVA was used for comparison of continuous variables. For ordinal variables, analysis was performed using the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test allowing for ties.

For multivariable analyses we chose variables that were either significant (p<0.20) characteristics in bivariable analyses, or characteristics we judged to be clinically important. The worry variables were markedly colinear with Skindex and were therefore excluded from the multivariable model. The clinically important variables we included were pre-treatment patient characteristics (patient age, gender, race, health status), tumor location, and care characteristics (treatment type and care site).

We found that the three treatment groups (destruction, excision, and Mohs) differed substantially in important patient, tumor and care characteristics. For example, destruction was rarely performed in tumors on the head and neck. To compare treatments, we sought to compare outcomes in patients who had similar patient, tumor and care characteristics. We restricted multivariable analyses to subjects in which sufficient numbers of patients shared patient (sex), tumor (location) and care (provider, site of care) characteristics. The case mix allowed for two sets of comparisons: patients treated with Mohs or excision and those treated with excision or destruction. We then used multivariable ordinal logistic models to evaluate independent predictors of long-term patient satisfaction, using generalized estimating equations (GEE) to adjust for clustering within strata defined by sex, site of care, provider, and tumor location.

We also performed a secondary analysis comparing Mohs and excision using matched pairs. The matched pairs were created using propensity scores resulting in 44 comparable pairs. We calculated propensity scores for each patient who had been treated with Mohs or excision using a logistic regression model. In this model, the dependent variable was whether the individual received Mohs or excision. The independent variables included sex, site of care, provider, tumor location, and variables shown to be associated with treatment choice including age, baseline Skindex composite score and baseline SF-12 Physical and Mental Component Scores. We then matched patients treated with Mohs to patients treated with excision by selecting the patient pair with the most similar propensity scores, removing the pair, and selecting a pair with the next most similar propensity scores. The process was repeated until the difference in propensity scores exceeded 0.2. We then calculated the average difference in satisfaction in the matched pairs. Significance was evaluated using a permutation test. For each pair, we randomly switched the treatment labels, and calculated the average difference in satisfaction. This process was repeated until it yielded the distribution of the average difference in satisfaction between the two treatments. The p-value was the proportion of times the observed absolute average difference in satisfaction exceeded the absolute average difference in satisfaction in the permuted data.

Statistical analyses were performed using Stata Statistical Software, Release 9.2, and the R programming language (http://www.r-project.org).

RESULTS

Baseline Characteristics

Treatment modalities included destruction by electrodessication and curettage (19%), excision (40%) and Mohs surgery (41%). Patients in the three treatment categories were similar in age, physical and mental health status, and co-morbidity index, but differed in education, income, baseline quality of life, and tumor characteristics. Also, excision was more likely to be performed at the VA, and Mohs was almost exclusively performed by attending physicians (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics (n=834)

| Characteristics | Overall | Destruction n= 162 | Excision n = 332 | Mohs n = 340 | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient Characteristics | |||||

| Age, years (mean) | 65.8 | 64.0 | 66.9 | 65.6 | 0.101 |

| Gender (% male) | 75.3 | 78.4 | 80.1 | 69.1 | 0.003 |

| Marital Status (% married) | 47.8 | 46.5 | 47.6 | 48.6 | 0.901 |

| Race (% Caucasian) | 94.4 | 96.1 | 93.2 | 94.6 | 0.425 |

| Education, % completed High School or less College Graduate/Professional School |

39.1 30.8 30.1 |

26.9 34.6 38.5 |

42.5 29.1 28.4 |

41.6 30.1 27.7 |

0.011 |

| Income, annual (%< $30,000) | 52.5 | 47.6 | 59.5 | 47.9 | 0.006 |

| History of previous NMSC (%) | 55.1 | 60.5 | 54.2 | 53.5 | 0.309 |

| % > median Charlson Index | 38.3 | 41.4 | 39.8 | 35.3 | 0.326 |

| Health Status (mean component score of SF-12)1 Physical Mental |

45.7 48.4 |

45.3 49.0 |

45.2 48.0 |

46.4 48.4 |

0.390 0.682 |

| Worry (mean score)2 about scar about treatment |

28.6 38.6 |

19.8 30.8 |

24.7 35.3 |

36.7 45.6 |

<0.001 <0.001 |

| Skindex Composite (mean score)3 | 25.0 | 20.7 | 24.9 | 27.3 | <0.001 |

| Tumor Characteristics | |||||

| Histologic type (% basal cell carcioma) | 76.6 | 79.6 | 68.4 | 83.2 | <0.001 |

| Diameter (mm, mean) | 10.7 | 9.6 | 12.4 | 9.5 | 0.003 |

| Location (% head & neck) | 68.3 | 29.2 | 59.0 | 95.9 | <0.001 |

| Care Characteristics | |||||

| Practice site (% VA) | 46.8 | 40.7 | 62.7 | 34.1 | <0.001 |

| Training level of clinician % attending % resident % nurse practitioner |

70.1 27.3 2.6 |

57.1 33.8 9.1 |

46.8 51.1 2.1 |

98.8 1.2 0 |

<0.001 |

As measured by SF-12 instrument which computes a Physical Component Summary Score (PCS12) and a Mental Component Summary Score (MCS12); a higher score reflects a better health status.

A higher score indicates more worry.

A higher score indicates worse quality of life.

Domains of Short-Term Satisfaction

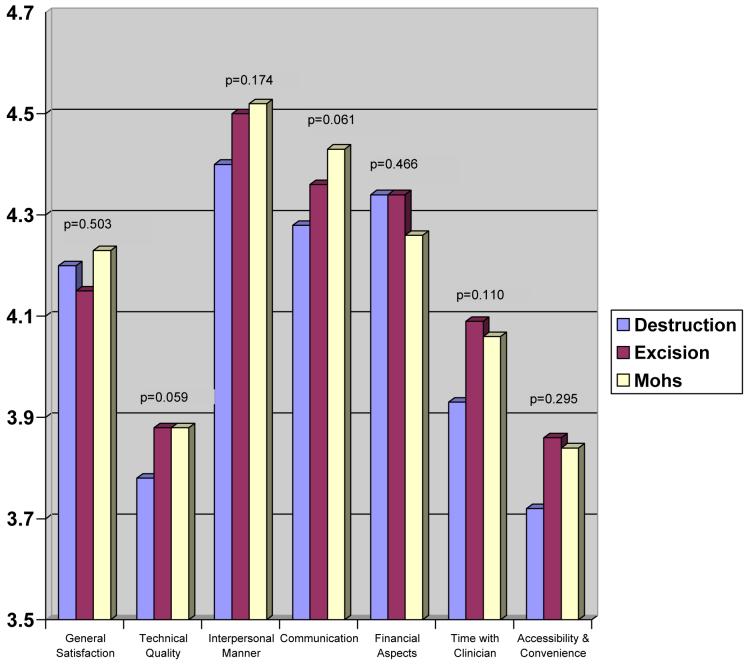

At one week after therapy, general satisfaction was high (4.19 ± 0.86). Overall, patients were more satisfied with the interpersonal manners of the staff, communication, and financial aspects of their care than with other domains of satisfaction. Patients in the three treatment groups had similar satisfaction with most domains, except that compared with patients treated with destruction, patients treated with Mohs and excision were somewhat more satisfied with the technical quality of their care, and with communication (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Domains of short-term patient satisfaction*

Predictors of Long-Term Patient Satisfaction

At one year after therapy, 571 patients (68%) responded about their long-term satisfaction with care. Overall, mean long-term satisfaction was high (4.08 ± 1.08), and, in bivariate analyses, was related to being married, having better baseline health status and skin-related quality of life, and having tumors on the head and neck (Table 2).

Table 2.

Long-Term Patient Satisfaction after Treatment for NMSC

| Characteristic | Patient Satisfaction at 1 year mean (± SD) | P |

|---|---|---|

| Patient Characteristics | ||

| Age ≤median >median |

4.10 (±1.1) 4.06 (±1.1) |

0.358 |

| Gender Male Female |

4.11 (±1.0) 3.97 (±1.2) |

0.399 |

| Race White Other |

4.11 (±1.1) 3.83 (±1.1) |

0.057 |

| Marital Status Married Single/divorce/widowed |

4.20 (±1.0) 3.95 (±1.2) |

0.007 |

| Education completed High School or less College or more |

4.11 (±1.1) 4.06 (±1.1) |

0.517 |

| Income < $30,000 ≥ $30,000 |

4.12 (±1.0) 4.05 (±1.1) |

0.457 |

| History of previous NMSC Yes No |

4.04 (±1.1) 4.13 (±1.0) |

0.480 |

| Skin Related Quality of Life (Skindex composite)1 < median score (better) □ median score (worse) |

4.22 (±0.99) 3.98 (±1.1) |

0.011 |

| Pre-Treatment Comorbidity2 ≤ median Charlson (better) > median Charlson (worse) |

4.09 (±1.1) 4.07 (±1.1) |

0.792 |

| Pre-Treatment Physical Health Status3 ≤median score (worse) > median score (better) |

4.00 (±1.1) 4.17 (±1.1) |

0.021 |

| Pre-Treatment Mental Health Status3 ≤median score (worse) > median score (better) |

3.91 (±1.1) 4.27 (±0.96) |

<0.001 |

| Pre-Treatment worry about scar ≤median score (less worry) >median score (more worry) |

4.20 (±1.0) 3.96 (±1.1) |

0.006 |

| Pre-treatment worry about treatment ≤median score (less worry) >median score (more worry) |

4.16 (±) 4.01 (±) |

0.123 |

| Tumor Characteristics | ||

| Histologic type Basal cell carcinoma Squamous cell carcinoma |

4.10 (±1.1) 4.00 (±1.1) |

0.299 |

| Location of lesion Head and neck Other |

4.15 (±1.0) 3.91 (±1.2) |

0.017 |

| Tumor diameter □ 10 mm > 10 mm |

4.08 (± 1.1) 4.12 (±1.0) |

0.947 |

| Care Characteristics | ||

| Practice Site VA hospital Private hospital |

4.06 (±1.1) 4.10 (±1.1) |

0.481 |

| Training Level of Clinician Attending Resident Nurse practitioner |

4.08 (±1.1) 4.08 (±1.1) 3.76 (±0.97) |

0.127 |

| Treatment Destruction Excision Mohs |

3.95 (±1.2) 4.02 (±1.1) 4.19 (±0.99) |

0.123 |

As defined by the composite Skindex16 score, defined as the mean of the three Skindex subscales: Symptoms, Emotional effects, and Effects on social functioning. A higher score indicates worse quality of life.

Using an adaptation of the Charlson Comorbidity Index. A higher score indicates more comorbid illness.

As measured by SF-12 instrument which computes a Physical Component Summary Score (PCS12) and a Mental Component Summary Score (MCS12); a higher score reflects a better health status

A higher score indicates more worry.

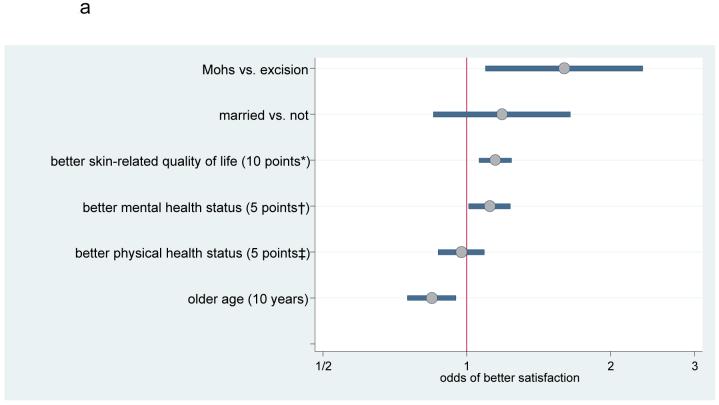

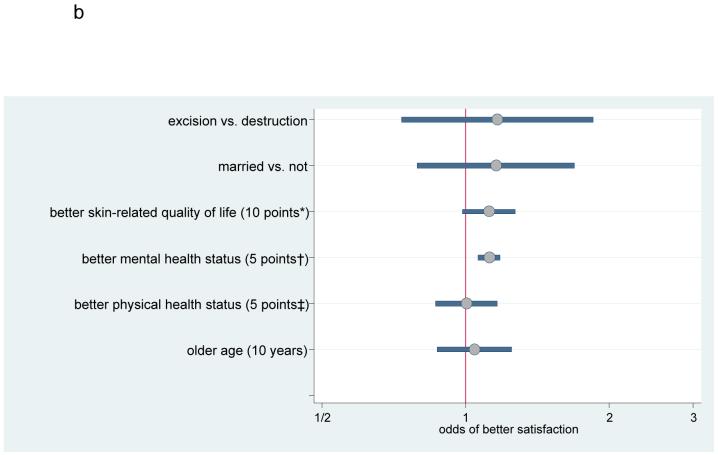

In the subset of patients treated with excision or Mohs (n=315), odds of higher long-term satisfaction was independently associated with younger age, better pre-treatment mental health status and skin-related quality of life, and treatment with Mohs surgery (Figure 2a). In the subset of patients treated with excision or destruction (n=211), odds of higher long-term satisfaction was independently associated (p<0.05) only with better pre-treatment mental health status (Figure 2b). Similar results were found in the propensity analyses.

Figure 2a.

Predictors of long-term satisfaction (Mohs compared with excision)*

Figure 2b.

Predictors of long-term satisfaction (excision compared with destruction)*

DISCUSSION

One week after treatment for NMSC, patients were generally satisfied with their care, but were more satisfied with the interpersonal manners of the staff, with communication, and with financial aspects of their care, compared to the technical quality, time with the clinician, and accessibility of their care. Compared with those treated with destruction, patients treated with excision or Mohs were somewhat more likely to perceive better technical quality and communication, but the 4 other domains of short-term satisfaction were similar across treatment groups.

A year after treatment for NMSC, overall long-term satisfaction with therapy was high regardless of treatment type. Among patients treated with excision or Mohs, independent predictors of higher satisfaction were younger age, better pre-treatment skin-related quality of life, better pre-treatment mental health status, and treatment with Mohs surgery. Among patients treated with excision or destruction, the only independent predictor of higher satisfaction was better pre-treatment mental health status.

In all comparisons, better pre-treatment mental health predicted higher long-term satisfaction after treatment of NMSC. These results are consistent with a previous prospective study of dermatologic outpatients, which also showed that patient satisfaction measured at 3 days and 4 weeks after a dermatologic outpatient encounter was significantly associated with pre-visit quality of life and psychiatric disorders.9 Further evidence of the association of lower patient satisfaction with self-reported psychiatric morbidity is supported by a recently published review of the dermatologic literature.8

In the comparison of patients treated with excision or Mohs, the odds of higher satisfaction were less for older patients. This finding is in contrast to previous studies that have shown that older patients are more satisfied with their care,9,20 independent of health status. On the other hand, the relationship of age and satisfaction is likely complex.21 One possible explanation for our findings is that older patients may have been less tolerant of the length of the Mohs surgery procedure, although this issue deserves further study.

The finding that Mohs surgery was an independent predictor of higher satisfaction is potentially important. Studies of predictors of short-term and long-term satisfaction have found that short-term satisfaction is more likely associated with patient-doctor communication whereas long-term satisfaction is reflective of symptom outcome (symptom resolution, need for repeat visits, functional status).20 One possible explanation for better odds of higher long-term satisfaction following Mohs may be better functioning of local structures due to the tissue-sparing aspects of the technique. We have found no difference between patients treated with Mohs or excision, however, in long-term quality-of-life outcomes, including bother from appearance and effects on social or physical functioning.7 These findings may be due to the fact that quality of life and satisfaction reflect different aspects of patients’ experience after therapy.

The PSQ-18 may have lacked sensitivity by failing to inquire about key factors that are known to influence overall satisfaction, such as environmental factors, interactions between non-provider office staff and patient,22 nursing care,23 and time spent in the waiting room.24-25, 26 Another limitation is that our study participants were patients willing to complete a questionnaire, which may limit generalizability. The 571 patients who responded about satisfaction at one year were similar to those who did not respond in many characteristics including age, gender, marital status, pretreatment physical and mental health, pretreatment Skindex scores, and tumor type and location of treatment, but had smaller tumors.

Although we have established statistically significant differences in the odds of higher satisfaction with certain patient and treatment characteristics, the clinical significance of these differences may be questioned. A previous study suggested that dermatology patients clearly differentiate between being satisfied or very satisfied with their healthcare.27 For some patients, being satisfied meant that aspects of their care could have been improved, whereas being very satisfied meant that optimal care had been provided. This finding suggests that subtle statistically significant differences in global satisfaction can have clinical relevance.

In summary, long-term patient satisfaction of treatment of NMSC is related to pre-treatment patient characteristics as well as treatment choice. These results need to be combined with data about other outcome measures to inform decision making for treatment of NMSC.

Acknowledgments

FUNDING:

NIAMS (K23 AR 051037-01, Dr. Asgari; K24 AR052667, Dr. Chren); Health Services Research & Development Service, Department of Veterans Affairs [IIR 04-043-3 (Dr. Chren), and Health Services Research Enhancement Award Program (REAP), San Francisco Veterans Affairs Medical Center].

Footnotes

We the authors certify that the manuscript represents original and valid work and neither the manuscript nor one with substantially similar content has been published or is being considered for publication elsewhere. The authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chren MM, Sahay AP, Sands LP, Maddock L, Lindquist K, Bertenthal D, Bacchetti P. Variation in care for nonmelanoma skin cancer in a private practice and a veterans affairs clinic. Med Care. 2004;42:1019–26. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200410000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smeets NW, Krekels GA, Ostertag JU, Essers BA, Dirksen CD, Nieman FH, Neumann HA. Surgical excision vs Mohs’ micrographic surgery for basal-cell carcinoma of the face: randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;364:1766–72. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17399-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kuijpers DI, Thissen MR, Neumann MH. Basal cell carcinoma: treatment options and prognosis, a scientific approach to a common malignancy. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2002;3:247–59. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200203040-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fleming ID, Amonette R, Monaghan T, Fleming MD. Principles of management of basal and squamous cell carcinoma of the skin. Cancer. 1995;75:699–704. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19950115)75:2+<699::aid-cncr2820751413>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hruza GJ. Mohs micrographic surgery local recurrences. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1994;20:573–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.1994.tb00149.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thissen MR, Neumann MH, Schouten LJ. A systematic review of treatment modalities for primary basal cell carcinomas. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135:1177–83. doi: 10.1001/archderm.135.10.1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chren MM, Sahay AP, Bertenthal DS, Sen S, Landefeld CS. Quality-of-Life Outcomes of Treatments for Cutaneous Basal Cell Carcinoma and Squamous Cell Carcinoma. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:1351–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Serup J, Lindblad AK, Maroti M, Kjellgren KI, Niklasson E, Ring L, Ahlner J. To follow or not to follow dermatological treatment--a review of the literature. Acta Derm Venereol. 2006;86:193–7. doi: 10.2340/00015555-0073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Renzi C, Abeni D, Picardi A, Agostini E, Melchi CF, Pasquini P, Puddu P, Braga M. Factors associated with patient satisfaction with care among dermatological outpatients. Br J Dermatol. 2001;145:617–23. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2001.04445.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Renzi C, Picardi A, Abeni D, Agostini E, Baliva G, Pasquini P, Puddu P, Braga M. Association of dissatisfaction with care and psychiatric morbidity with poor treatment compliance. Arch Dermatol. 2002 Mar;138(3):337–42. doi: 10.1001/archderm.138.3.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stelfox HT, Gandhi TK, Orav EJ, Gustafson ML. The relation of patient satisfaction with complaints against physicians and malpractice lawsuits. Am J Med. 2005;118:1126–33. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.01.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Katz JN, Chang LC, Sangha O, Fossel AH, Bates DW. Can comorbidity be measured by questionnaire rather than medical record review? Med Care. 1996;34:73–84. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199601000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–83. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chren MM, Lasek RJ, Sahay AP, Sands LP. Measurement properties of Skindex-16: a brief quality-of-life measure for patients with skin diseases. J Cutan Med Surg. 2001;5:105–10. doi: 10.1007/BF02737863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ware J, Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34:220–33. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marshall GN, Hays RD. The Patient Satisfaction Questionnaire Short-Form (PSQ-18) The RAND Corporation; 1994. p. 7865. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harada ND, et al. Satisfaction with VA and non-VA outpatient care among veterans. Am J Med Qual. 2002;17:155–64. doi: 10.1177/106286060201700405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harpole LH, et al. Patient Satisfaction in the Ambulatory Setting. J Genl Intern Med. 1996;11:431–434. doi: 10.1007/BF02600192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Swanson NA, Grekin RC, Baker SR. Mohs surgery: techniques, indications, and applications in head and neck surgery. Head Neck Surg. 1983;6:683–92. doi: 10.1002/hed.2890060209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jackson JL, Chamberlin J, Kroenke K. Predictors of patient satisfaction. Soc Sci Med. 2001;52(4):609–20. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00164-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jaipaul CK, Rosenthal GE. Are older patients more satisfied with hospital care than younger patients? J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18(1):23–30. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.20114.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lipkin M, Schwartz MD. I can’t get no patient or practitioner satisfaction. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15:140–1. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.02002.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dixon AJ, Dixon MP, Dixon JB. Prospective study of long-term patient perceptions of their skin cancer surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:445–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2007.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hill J, Bird HA, Hopkins R, Lawton C, Wright V. Survey of satisfaction with care in a rheumatology outpatient clinic. Ann Rheum Dis. 1992;51:195–7. doi: 10.1136/ard.51.2.195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wolosin RJ. The voice of the patient: a national, representative study of satisfaction with family physicians. Qual Manag Health Care. 2005;14:155–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dawn AG, Lee PP, Hall-Stone T, Gable W. Development of a patient satisfaction survey for outpatient care: a brief report. J Med Pract Manage. 2003;19:166–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Collins K, O’Cathain A. The continuum of patient satisfaction--from satisfied to very satisfied. Soc Sci Med. 2003;57:2465–70. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(03)00098-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]