ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND

Self-management support is an important component of improving chronic care delivery.

OBJECTIVE

To validate a new measure of self-management support and to characterize performance, including comparisons across chronic conditions.

DESIGN, SETTING, PARTICIPANTS

We incorporated a new question module for self-management support within an existing annual statewide patient survey process in 2007.

MEASUREMENTS

The survey identified 80,597 patients with a chronic illness on whom the new measure could be evaluated and compared with patients’ experiences on four existing measures (quality of clinical interactions, coordination of care, organizational access, and office staff). We calculated Spearman correlation coefficients for self-management support scores for individual chronic conditions within each medical group. We fit multivariable logistic regression models to identify predictors of more favorable performance on self-management support.

RESULTS

Composite scores of patient care experiences, including quality of clinical interactions (89.2), coordination of care (77.6), organizational access (76.3), and office staff (85.8) were higher than for the self-management support composite score (69.9). Self-management support scores were highest for patients with cancer (73.0) and lowest for patients with hypertension (67.5). The minimum sample size required for medical groups to provide a reliable estimate of self-management support was 199. There was no consistent correlation between self-management support scores for individual chronic conditions within medical groups. Increased involvement of additional members of the healthcare team was associated with higher self-management support scores across all chronic conditions.

CONCLUSION

Measurement of self-management support is feasible and can identify gaps in care not currently included in standard measures of patient care experiences.

KEY WORDS: chronic disease, quality measurement, patient-centered care, quality of care, quality improvement

INTRODUCTION

Chronic disease management has become increasingly complex, presenting challenges to the delivery of high-quality care necessary to prevent long-term complications.1 Chronic conditions are responsible for 70% of deaths in the United States and account for 75% of healthcare costs,2 creating an imperative to improve chronic disease management.

Increasing evidence supports the notion that the delivery of patient-centered care is key to improving chronic disease management.3 Providing effective self-management support for chronic conditions can improve outcomes by enabling the patients to cope with all aspects of their disease, including symptoms and treatment strategies.4–8 As physician groups strive to deliver chronic disease care that is both clinically effective and patient-centered,3,9 many are adopting new care delivery models that involve increasing the provision of effective self-management support.10–12

The increased focus by physician groups on the provision of self-management support places an emphasis on the need to reliably measure performance in this area. However, current measurement programs focus on clinical process, clinical outcomes, and more generic measures of patient experiences of care.13–15 There is limited information on the large-scale measurement of self-management support that could guide healthcare systems seeking to quantify their care improvement activities.16

Using statewide data within California, this paper introduces an initial effort at a survey-based measure of delivery of self-management support within medical groups, evaluates its psychometric performance, and describes performance among medical groups relative to standard measures of patient experiences of care.

METHODS

Study Setting

We used data collected from 173 medical groups participating in a statewide performance measurement initiative in California during 2007. These medical groups, a mix of free-standing physician practices and independent practice associations, provide healthcare for approximately 90% of the state’s insured population. The medical groups range in size from as small as 20 physicians to several thousand physicians in the larger, independent practice associations.

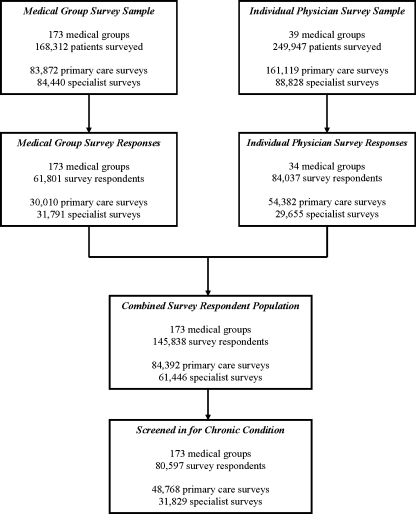

Survey Implementation

We combined data collected from two sampling frames, a medical group level survey and an individual physician level survey (Figure 1). The medical group level survey sample identified all patients 18 years and older who had a visit with either a primary care or specialist physician during the 10-month period from January to October 2007. A random sample of 900 patients per medical group was then selected. Each of these 900 patients was linked to a single physician (either primary care or specialist) based on their visit history. This sampling scheme did not mean that patients were only treated by the physician named in the survey, but ensured that the patient was eligible to evaluate their experiences with the specific primary care or specialist physician named in the survey. The survey was administered in a 3-stage process, with an initial mailing, a follow-up mailing, and a final telephone reminder to nonresponders. The overall response rate was 37%.

Figure 1.

Patients with chronic disease were included based on receiving care from a primary care physician or specialist within one of the medical groups self-reporting clinical performance data.

The individual physician level survey sample was derived from a subset ( = 39) of the medical groups who volunteered to participate to gain physician-level results that might inform targeted improvement strategies. Each medical group first identified individual physicians to be included in this survey process. Patients were identified based on the presence of an office visit with an individual physician during the 10-month period from January to October 2007. A random sample of 100 patients per physician was then selected. These patients were exclusive of the 900 patients sampled from that site for the medical group level survey. The survey was administered in a 2-stage process, with an initial mailing followed by a second mailing to nonresponders. The overall response rate was 34%.

Survey Instrument

Patient experiences of care were measured using the previously validated Ambulatory Care Experiences Survey (ACES).13 The first item in the survey instrument names the actual physician being evaluated, and respondents confirm whether this is their personal physician or a specialist physician they have seen. The remainder of the survey items assess care delivered by that physician. The ACES instrument produces summary measures of care experiences consistent with those created using the Clinician and Group Consumer Assessment of Health Plans instrument recently endorsed by the National Quality Forum.17

We further assessed self-management support by first asking patients to respond to the question “In the last 12 months, did you have any health problems or conditions for which you took medicine or got care for 3 months or longer?” Patients responding positively to this question were asked to specify the chronic condition from a list including arthritis or joint disease, asthma, back pain, cancer, congestive heart failure, coronary artery disease, other heart disease, depression, diabetes, hypertension or high blood pressure, pregnancy or prenatal care, and other. Finally, a follow-up question confirmed “In the last 12 months, was this doctor involved in providing your care for this health condition?” Patients responding affirmatively to this question were linked to that physician and included in the analyses. Respondents further identified other providers involved in the care of their chronic condition as any combination of 1) other physicians, 2) nurse practitioners, 3) physician assistants, 4) nurses, 5) nutritionists, or 6) physical therapists.

Among respondents screening in to this chronic care module of the survey, five survey items specifically assessed elements of self management support that generalize across chronic conditions, including 1) “Did you get clear instructions about how to manage this health condition from this doctor or any of your other providers?” 2) “Did your doctor or any of your other providers work with you to set personal goals for managing this health condition?” 3) “Did your doctor or any of your other providers help you figure out ways to overcome the things in your daily life that got in the way of managing this health condition?” 4) “In the last 12 months, how often did this doctor seem informed and up-to-date about care you received for this condition from other providers?” and 5) “In the last 12 months, did this doctor or any of these other providers ask you whether this health condition makes it hard to do the things you need to do each day (for example at home or at work)?” The first three items employed a 4-point scale of "Definitely Yes," "Somewhat Yes," "Somewhat No," and "Definitely No." The fourth item used a 6-point scale of "Never," "Almost Never," "Sometimes," "Usually," "Almost Always," and "Always." The fifth item used a Yes/No response scale.

The survey also assessed patient demographics (age, sex, and race) and overall and mental health from the 12-item Short Form Health Survey (using a 5-point Likert scale from "Excellent" to "Poor").18

Composite Measure Creation

We used individual survey item responses to create four composite measures of patient experience and one composite measure of disease self-management support. The patient experience composites included coordination of care, organizational access, and office staff.13,19 We created a self-management support composite using the five individual items described above. Numeric composite scores were calculated using the adjusted half-scale rule to produce ratings on a scale from 0 to 100, with higher scores representing more favorable patient responses. This method involves first transforming the individual item to a 0 to 100 scale based on the number of available responses for that item (e.g., a 6-point Likert response item would generate a score of 0, 20, 40, 60, 80, or 100).20 We adjusted these scores by adding or subtracting a constant for each item so that all items have the same mean (the average of the overall mean of all items in the scale).

We applied standard tests of psychometric performance to evaluate the self-management support composite, including assessment of internal consistency using Cronbach’s alpha, and assessment of convergent and discriminant validity with tests of item-scale correlations, scaling success, and composite distribution characteristics. Finally, we estimated sample sizes required to achieve a group-level reliability coefficient of 0.70 for the self-management support composite using the Spearman Brown Prophecy Formula. This reliability coefficient estimates the level of concordance in responses provided by patients within medical group samples, ranging from 0 to 1.0.18

Self-Management Support Performance

We calculated Spearman correlation coefficients to assess whether a medical group’s performance on delivery of self-management support for one chronic condition is related to its performance for other chronic conditions. These analyses were limited to eight chronic conditions: arthritis, asthma, back pain, cancer, cardiovascular disease, depression, diabetes, and hypertension. These analyses were limited to patients indicating the presence of only a single chronic condition to avoid artificial inflation of the correlations that might be created by including the same patient multiple times across conditions.

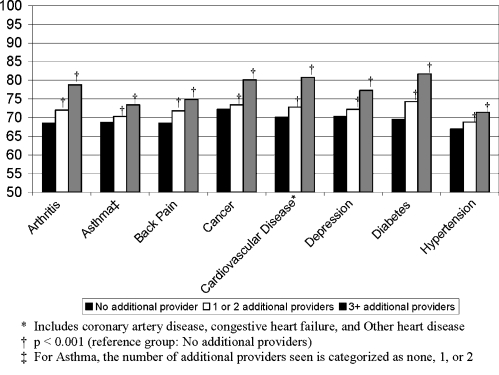

We fit multivariable linear regression models to compare self-management support composite scores between those patients reporting no involvement of additional healthcare team members, and those reporting involvement of 1 to 2, and 3 or more additional team members for the same eight chronic conditions. For these analyses, value-added healthcare team members were defined for each chronic condition, and all models were adjusted for patient age, sex, and self-reported physical and mental health status (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Self-management support composite scores increased with involvement of more members of the value-added healthcare team. The value-added healthcare team members were defined for each chronic condition as follows 1) arthritis care team: nurse practitioner, nurse, physical therapist, and nutritionist; 2) asthma care team: nurse practitioner and nurse; 3) back pain care team: nurse practitioners, nurse, and physical therapist; 4) cancer care team: nurse practitioner, nurse, and nutritionist, 5) cardiovascular disease care team: nurse practitioner, nurse, and nutritionist; 6) depression care team: nurse practitioner, nurse, and another physician; 7) diabetes care team: nurse practitioner, nurse, and nutritionist; 8) hypertension care team: nurse practitioner, nurse, and nutritionist. Patients can report the presence of more than one chronic condition.

This study protocol was approved by the Human Studies Committee at Tufts Medical School. All analyses were carried out using the STATA statistical package, version 9.0.

RESULTS

Survey Respondent Characteristics

Among 145,838 total respondents, 80,597 (55%) indicated the presence of a chronic disease (Figure 1). Hypertension was the most commonly reported chronic condition (Table 1). Evaluations of primary care physicians were distributed among general internists and family practice physicians. The specialty physicians included medical specialists (35%), surgical specialists (36%), and obstetrics/ gynecology (24%).

Table 1.

Patient Experience Survey Respondent Characteristics

| All survey respondents, (%) | Primary care survey respondents, (%) | Specialist survey respondents, (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chronic Disease Screen-in Rates | N = 145,838 | N = 84,392 | N = 61,446 |

| Overall† | 80,597 (55) | 48,768 (57) | 31,829 (49) |

| Hypertension | 27,050 (19) | 20,014 (24) | 7,036 (11) |

| Diabetes | 12,261 (8) | 8,607 (10) | 3,654 (6) |

| Arthritis or joint disease | 11,839 (8) | 7,277 (9) | 4,562 (7) |

| Back pain | 9,026 (6) | 6,315 (7) | 2,711 (4) |

| Depression | 8,288 (6) | 6,201 (7) | 2,087 (3) |

| Asthma | 5,104 (3) | 3,539 (4) | 1,565 (2) |

| Other heart disease | 3,866 (3) | 2,434 (3) | 1,432 (2) |

| Cancer | 4,228 (3) | 1,624 (2) | 2,604 (4) |

| Coronary artery disease | 3,019 (2) | 1,797 (2) | 1,222 (2) |

| Congestive heart failure | 1,873 (1) | 1,234 (1) | 639 (1) |

| Pregnancy/ prenatal condition | 2,521 (2) | 417 (0.4) | 2,104 (3) |

| Other | 3,127 (2) | 1,022 (1) | 2,105 (3) |

| Demographic and clinical features of patients reporting a chronic condition‡ | N = 80,597 | N = 48,768 | N = 31,829 |

| Mean age, years (± SD) | 57.0 (14.6) | 58.5 (14.6) | 54.7 (14.3) |

| Male (%) | 38.8 | 41.4 | 34.8 |

| Race | |||

| White, not Hispanic | 66.8 | 66.7 | 66.8 |

| Black, not Hispanic | 4.8 | 4.8 | 4.8 |

| Hispanic | 14.9 | 15.6 | 13.8 |

| Asian | 10.0 | 9.3 | 11.0 |

| Other | 3.5 | 3.5 | 3.6 |

| General health status | |||

| Excellent/ Very Good/ Good | 79.1 | 78.9 | 79.3 |

| Fair/ Poor | 20.9 | 21.1 | 20.7 |

| Mental health status | |||

| Excellent/ Very Good/ Good | 87.6 | 86.9 | 88.7 |

| Fair/ Poor | 12.4 | 13.1 | 11.3 |

| Specialty of physician evaluated | |||

| Family practice | 34.3 | 56.3 | 0.0 |

| Internal medicine | 26.2 | 43.0 | 0.0 |

| Medical specialty§ | 17.1 | 0.7 | 34.7 |

| Surgical specialty|| | 13.6 | 0.0 | 36.2 |

| Obstetrics/ gynecology | 6.7 | 0.0 | 23.5 |

| Other | 2.1 | 0.0 | 5.6 |

† Includes patients that indicated treatment for a chronic condition, but did not indicate specific disease. Patients could have identified more than one chronic condition.

‡ Among those that screened in for a chronic condition.

§ Includes allergy/immunology, cardiology, dermatology, endocrinology, gastroenterology, infectious disease, nephrology, neurology, oncology/hematology, pulmonology, rheumatology.

|| Includes cardiothoracic surgery, general surgery, neurosurgery, orthopedic surgery, ophthalmology, otolaryngology, physical medicine, plastic surgery, urology, and vascular surgery.

¶ Includes behavioral medicine, emergency medicine, perinatology, and pain management.

Self-Management Support Composite Construct Validity

The Cronbach’s alpha for the self-management support composite exceeded the established standard for internal consistency reliability for population analysis (0.70), with a coefficient of 0.75 among primary care survey respondents and 0.71 among specialist survey respondents (overall Cronbach’s alpha = 0.73). The self-management support composite achieved 92% scaling success among both the primary care and specialist responses. Lack of perfect scaling success owed to one item whose correlation with another composite (coordination) was slightly higher (doctor informed and up-to-date about care you received for chronic condition from other providers). This item was retained in the composite as it resulted in increased medical group level reliability scores as well as captured the increasing need to coordinate chronic care delivery across multiple providers.21,22 Finally, minimum sample size required to achieve stable and reliable information about self-management support at the medical group-level (αmedical group = 0.70) was 199 across all conditions. However, this minimum sample size ranged from a low of 97 for patients reporting a history of diabetes to a high of 360 for patients reporting a history of cardiovascular disease (Table 2). Smaller required sample sizes indicate either less within-group differences in patients’ reported experiences or larger between-group differences.

Table 2.

Patient Experiences of Care and Self-Management Support among Medical Groups||

| Quality of clinical interactions | Coordination of care | Organizational access | Office staff | Self-management support | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD‡ | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Minimum † | |

| Any condition§ | 89.2 | 2.4 | 77.6 | 4.1 | 76.3 | 3.9 | 85.8 | 2.7 | 69.9 | 2.8 | 199 |

| Arthritis ( = 11,839) | 88.4 | 2.4 | 76.0 | 4.6 | 75.6 | 3.7 | 86.0 | 2.6 | 70.3 | 2.6 | 221 |

| Asthma ( = 5,104) | 89.3 | 2.8 | 76.6 | 5.1 | 75.9 | 4.5 | 85.6 | 2.5 | 69.5 | 2.6 | 226 |

| Back pain ( = 9,026) | 87.0 | 2.7 | 74.4 | 4.8 | 73.5 | 4.0 | 84.0 | 3.6 | 70.3 | 3.6 | 120 |

| Cancer ( = 4,228) | 90.2 | 2.6 | 79.9 | 2.7 | 78.9 | 3.8 | 88.1 | 1.5 | 73.0 | 3.5 | 104 |

| Cardiovascular disease* ( = 3,716) | 89.1 | 2.5 | 79.2 | 4.3 | 77.5 | 4.4 | 87.3 | 2.8 | 71.1 | 2.0 | 360 |

| Depression ( = 8,288) | 89.0 | 2.5 | 76.7 | 4.0 | 75.0 | 3.8 | 84.9 | 3.1 | 71.3 | 2.8 | 190 |

| Diabetes ( = 12,261) | 89.5 | 2.6 | 78.8 | 4.3 | 76.8 | 4.5 | 86.2 | 2.8 | 71.5 | 2.5 | 97 |

| Hypertension ( = 17,861) | 89.8 | 2.4 | 78.0 | 4.5 | 77.2 | 4.2 | 86.6 | 2.6 | 67.5 | 2.8 | 200 |

* Includes coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, and other heart disease.

† Minimum sample size per medical group required to achieve 0.70 reliability in estimation of self-management support.

‡ Refers to standard deviation of the measure across medical groups.

§ Refers to all patients reporting treatment of any condition for at least 3 months.

|| Patients can report the presence of more than one chronic condition.

Self-Management Support Performance

The mean performance on the self-management support composite across all medical groups was 69.9 (standard deviation 2.8). Scores were highest for diabetes (73.0), and lowest for hypertension (67.5). The variability of the self-management support composite across medical groups as measured by the standard deviation of scores varied by chronic condition, ranging from a low of 2.0 for cardiovascular disease to a high of 3.6 for back pain. Performance on the four standard measures of patient experience was uniformly higher than the measure of self-management support across all chronic conditions (Table 2).

Predictors of Increased Self-Management Support

Correlations between performance on delivery of self-management support for individual chronic conditions within medical groups were small and few were statistically significant (Table 3). Approximately two-thirds (63%) of patients reporting a chronic disease indicated receipt of care for their condition from a single physician during the past year while the remainder (37%) reported receiving care for their condition from two or more providers defined as part of the value-added team. The proportion of patients reporting receipt of care from two or more providers varied across conditions, including arthritis (40%), asthma (38%), back pain (48%), cancer (48%), cardiovascular disease (34%), depression (39%), diabetes (36%), and hypertension (23%).

Table 3.

Spearman Correlation Coefficients For Self-Management Support Scores Within Individual Medical Groups

| Arthritis | Asthma | Diabetes | Back pain | Cancer | Hypertension | Cardiac disease | Depression | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arthritis | − | |||||||

| Asthma | 0.23 | − | ||||||

| Diabetes | 0.26 | 0.29 | − | |||||

| Back pain | 0.33 | 0.24 | 0.26 | − | ||||

| Cancer | 0.11 | 0.17 | 0.23 | 0.16 | − | |||

| Hypertension | 0.33 | 0.30 | 0.21 | 0.33 | 0.12 | − | ||

| Cardiac disease | 0.02 | 0.15 | 0.02 | 0.11 | 0.07 | 0.08 | − | |

| Depression | 0.31 | 0.41* | 0.22 | 0.40* | 0.30 | 0.32 | 0.09 | − |

*P < 0.05

Self-management support scores across all chronic conditions demonstrated a consistent positive association with increased involvement of additional members of the value-added healthcare team, including other physicians, nurse practitioners, nurses, physical therapists, and nutritionists (Figure 2).

We repeated all analyses separately for the medical group level and individual physician survey samples and found no differences from the combined results presented above (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

Achieving breakthroughs in chronic disease management will involve changing the structure of healthcare delivery and increasing patient engagement in disease management.11,23,24 Despite the potential of such activities to improve chronic disease outcomes, and the availability of some tools to evaluate the level of self-management support,25,26 there is little information regarding the incorporation of measures of self-management support into existing performance measurement paradigms.16 In this statewide evaluation of medical groups, we tested a new measure of self-management support among patients reporting a variety of chronic conditions. Medical group performance on this important dimension of care was uniformly below that observed for other well-established measures of patient experiences of care, and there was significant variation across medical groups.

We found that a sample size of fewer than 200 patients achieves the reliability needed to ensure stable estimates of self-management support at the level of individual medical groups. This number appeared relatively reproducible across all conditions with the exception of cardiovascular disease, which would require 360 patients to ensure stable estimates. While we identified substantial numbers of patients with chronic conditions, our screen in rate of only 55% suggests that sampling schemes may be improved to better target patients with chronic illness based on the use of claims data or other mechanisms.

The provision of self-management support lagged behind other measures of delivering patient centered care. One essential question for healthcare systems is how to improve the delivery of self-management support.27,28 Our results suggest several potential avenues associated with increased self-management support among medical groups. Use of multidisciplinary care teams was strongly associated with delivery of self-management support, consistent with previous analyses of organizational features of care that predict delivery of such support.29 In addition, our analyses suggest that improving delivery of self-management support may require unique activities for individual chronic conditions, as there was little correlation detected between self-management support scores for these conditions within medical groups.

Our study expands on the existing literature in several important ways. First, our performance evaluation included patients reporting multiple chronic conditions as opposed to focusing on a single disease,30 increasing its applicability to a broader set of clinical practice settings. Our project allowed us to demonstrate the feasibility of large-scale collection of these data as part of a performance reporting program, as well as to explore the association of various characteristics of the healthcare delivery system with delivery of self-management support.

There are important limitations to this analysis. First, we did not analyze whether higher performance on this measure of self-management support results in improved clinical outcomes. However, patient experiences of care, including self-management support, represent an important pillar of high-quality care delivery that warrant measurement independent of clinical outcomes.16 Second, in order to capture elements of team-based chronic care delivery, our survey items related to self-management support referenced care provided by other providers in addition to the targeted physician. This limits our ability to draw comparisons among individual physicians. However, we were focused on performance of the entire medical group, rather than individual physicians. We received responses from slightly more than one-third of those surveyed, raising the possibility of a biased sample. However, our response rate is consistent with other large surveys of patient experiences of care that have confirmed that survey nonresponse does not pose a threat to the validity of the findings.13 Finally, our results may not generalize to other settings with healthcare environments different than our sample of relatively large medical groups in California.31

In conclusion, we demonstrated the feasibility of measuring self-management support among a chronically ill patient population, and identified significant variation in the delivery of such support across medical groups. Provision of self-management support is significantly lagging behind delivery of other measures of patient centered care. The majority of patients reported management of their chronic illness by a single physician, rather than as part of a team based approach; however, the use of multidisciplinary teams was associated with more favorable self-management support reported by patients. As improvements in chronic disease care become increasingly reliant on patient engagement in disease management, performance measurement programs should seek to incorporate this domain of care, as well as identify characteristics of medical groups that perform well in this area for all chronic conditions.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the California Healthcare Foundation. The funding agency played no role in design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. Dr. Sequist had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis

Conflict of Interest Dr. Sequist serves as consultant on the Aetna External Advisory Committee on Racial and Ethnic Equality.

References

- 1.Vogeli C, Shields AE, Lee TA, et al. Multiple chronic conditions: prevalence, health consequences, and implications for quality, care management, and costs. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(Suppl 3):391–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Hardy GE Jr. The burden of chronic disease: the future is prevention. Introduction to Dr. James Marks’ presentation, “The Burden of Chronic Disease and the Future of Public Health". Prev Chronic Dis. 2004;1:A04. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Bergeson SC, Dean JD. A systems approach to patient-centered care. JAMA. 2006;296:2848–851. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Harvey PW, Petkov JN, Misan G, et al. Self-management support and training for patients with chronic and complex conditions improves health-related behaviour and health outcomes. Aust Health Rev. 2008;32:330–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Bayliss EA, Bosworth HB, Noel PH, Wolff JL, Damush TM, McIver L. Supporting self-management for patients with complex medical needs: recommendations of a working group. Chronic Illn. 2007;3:167–175. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Fisher EB, Brownson CA, O’Toole ML, Shetty G, Anwuri VV, Glasgow RE. Ecological approaches to self-management: the case of diabetes. Am J Public Health. 2005;95:1523–535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Gibson PG, Powell H, Coughlan J, et al. Self-management education and regular practitioner review for adults with asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003: CD001117. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Coleman MT, Newton KS. Supporting self-management in patients with chronic illness. Am Fam Physician. 2005;72:1503–510. [PubMed]

- 9.Audet AM, Davis K, Schoenbaum SC. Adoption of patient-centered care practices by physicians: results from a national survey. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:754–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Bodenheimer T, Wagner EH, Grumbach K. Improving primary care for patients with chronic illness: the chronic care model, Part 2. JAMA. 2002;288:1909–1914. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Casalino L, Gillies RR, Shortell SM, et al. External incentives, information technology, and organized processes to improve health care quality for patients with chronic diseases. JAMA. 2003;289:434–441. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Siminerio LM, Piatt GA, Emerson S, et al. Deploying the chronic care model to implement and sustain diabetes self-management training programs. Diabetes Educ. 2006;32:253–260. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Safran DG, Karp M, Coltin K, et al. Measuring patients’ experiences with individual primary care physicians. Results of a statewide demonstration project. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:13–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Fung CH, Lim YW, Mattke S, Damberg C, Shekelle PG. Systematic review: the evidence that publishing patient care performance data improves quality of care. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:111–123. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Rosenthal MB, Landon BE, Normand SL, Frank RG, Epstein AM. Pay for performance in commercial HMOs. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1895–1902. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Glasgow RE, Peeples M, Skovlund SE. Where is the patient in diabetes performance measures? The case for including patient-centered and self-management measures. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:1046–1050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Solomon LS, Hays RD, Zaslavsky AM, Ding L, Cleary PD. Psychometric properties of a group-level Consumer Assessment of Health Plans Study (CAHPS) instrument. Med Care. 2005;43:53–60. [PubMed]

- 18.Burdine JN, Felix MR, Abel AL, Wiltraut CJ, Musselman YJ. The SF-12 as a population health measure: an exploratory examination of potential for application. Health Serv Res. 2000;35:885–904. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Sequist TD, Schneider EC, Anastario M, et al. Quality monitoring of physicians: linking patients’ experiences of care to clinical quality and outcomes. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:1784–1790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Nunnally JC, Bernstein IH. Psychometric Theory. New York: McGraw Hilll; 1994.

- 21.Pham HH, O’Malley AS, Bach PB, Saiontz-Martinez C, Schrag D. Primary care physicians’ links to other physicians through Medicare patients: the scope of care coordination. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:236–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Pham HH, Schrag D, O’Malley AS, Wu B, Bach PB. Care patterns in Medicare and their implications for pay for performance. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1130–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Casalino LP. Disease management and the organization of physician practice. JAMA. 2005;293:485–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Davis K, Schoenbaum SC, Audet AM. A 2020 vision of patient-centered primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:953–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Brownson CA, Miller D, Crespo R, et al. A quality improvement tool to assess self-management support in primary care. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2007;33:408–416. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Bonomi AE, Wagner EH, Glasgow RE, VonKorff M. Assessment of chronic illness care (ACIC): a practical tool to measure quality improvement. Health Serv Res. 2002;37:791–820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Glasgow RE, Davis CL, Funnell MM, Beck A. Implementing practical interventions to support chronic illness self-management. Jt Comm J Qual Saf. 2003;29:563–574. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Glasgow RE, Funnell MM, Bonomi AE, Davis C, Beckham V, Wagner EH. Self-management aspects of the improving chronic illness care breakthrough series: implementation with diabetes and heart failure teams. Ann Behav Med. 2002;24:80–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Shetty G, Brownson CA. Characteristics of organizational resources and supports for self management in primary care. Diabetes Educ. 2007;33(Suppl 6):185S–192S. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.McCormack LA, Williams-Piehota PA, Bann CM, et al. Development and validation of an instrument to measure resources and support for chronic illness self-management: a model using diabetes. Diabetes Educ. 2008;34:707–718. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Gillies RR, Shortell SM, Casalino L, Robinson JC, Rundall TG. How different is California? A comparison of U.S. physician organizations. Health Aff (Millwood). 2003: W3–492–502. Suppl Web Exclusives. [DOI] [PubMed]