Abstract

Stem cells, their niches, and their relationship to cancer are under intense investigation. Because tumors and metastases acquire self-renewing capacity, mechanisms for their establishment may involve cell–cell interactions similar to those between stem cells and stem cell niches. On the basis of our studies in Caenorhabditis elegans, we introduce the concept of a “latent niche” as a differentiated cell type that does not normally contact stem cells nor act as a niche but that can, under certain conditions, promote the ectopic self-renewal, proliferation, or survival of competent cells that it inappropriately contacts. Here, we show that ectopic germ-line stem cell proliferation in C. elegans is driven by a latent niche mechanism and that the molecular basis for this mechanism is inappropriate Notch activation. Furthermore, we show that continuous Notch signaling is required to maintain ectopic germ-line proliferation. We highlight the latent niche concept by distinguishing it from a normal stem cell niche, a premetastatic niche and an ectopic niche. One of the important distinguishing features of this mechanism for tumor initiation is that it could operate in the absence of genetic changes to the tumor cell or the tumor-promoting cell. We propose that a latent niche mechanism may underlie tumorigenesis and metastasis in humans.

Keywords: Caenorhabditis elegans, Delta/Serrate/LAG-2, Notch, stem cell, Pro phenotype

The Caenorhabditis elegans hermaphrodite germ line offers a simple system to investigate principles of stem cell biology, including the biology of interactions between stem cells and niches (1–3) (Fig. 1A). A single somatic cell, the distal tip cell (DTC), acts as a germ-line stem cell niche. Distal tip cell–germ line interaction promotes germ-line self-renewal through a Notch signal transduction pathway, maintaining a pool of proliferating niche-associated germ-line stem cells. The Delta/Serrate/LAG-2 (DSL)-family ligands LAG-2 and APX-1 are expressed in the DTC and activate the GLP-1 Notch-family receptor in the germ line (4–6). Elevating GLP-1/Notch signaling in the germ line results in a “tumorous” phenotype in which germ cells fail to differentiate and continue to proliferate (7). Ablation of the DTC causes all germ cells to differentiate (8). Alteration in the number or location of the DTCs early in development can seed new germ cell proliferation centers (8, 9), demonstrating that the DTC functions as a stem cell niche.

Fig. 1.

“Latent niche” mechanism of tumor initiation. (A) Schematic representation of the cellular mechanism by which a delay in germ-line differentiation causes tumorous growth in the Caenorhabditis elegans proximal germ line in response to a latent niche. During gonadogenesis, the distance between the distal tip cell (DTC) (red) and the proximal gonad depends on both an intrinsic DTC migration program and the number of germ cells in the gonad (at each time point depicted, distal is to the left and proximal is to the right). In the wild type, proximal germ cells enter meiosis in the middle of the third larval stage (mid-L3), and the proximal sheath cells (blue) are born in the mid-L4. Only the two proximal-most pairs of sheath cells, Sh4 and Sh5, are depicted here. Undifferentiated and differentiated germ cells are indicated in yellow and green, respectively. Two mutant conditions display insufficient early gonad arm extension: hlh-12(Pro/Tum) displays a DTC-autonomous migration defect, and pro-1(Pro) displays a sheath-lineage-autonomous germ-line proliferation defect. The designation hlh-12(Pro/Tum) refers to the observation that hlh-12 mutant individuals with smaller tumors did not contain gametes between the distal and the proximal proliferation centers (“Tum”), whereas those with larger tumors often contained gametes in the center (“Pro”). A third mutant condition, glp-1(Pro), displays a germ-line-autonomous delay in differentiation. In contrast to the wild type, in each mutant undifferentiated germ cells contact the proximal sheath cells (latent niche) in the L4, resulting in a proximal tumor in the adult. Black arrows indicate time, and small blue arrows indicate DSL ligand signaling. (B) (Left and Center) Expression of nuclear-localized Papx-1::NLSlacZ (21) and Papx-1::GFP (naEx156) in a subset of proximal gonadal sheath and spermathecal cells (fixed and live worms, respectively). (Right) Expression of Parg-1::GFP (naEx180) in the proximal gonadal sheath. Proximal sheath pairs 4 and 5 (Sh4 and Sh5) are indicated by dotted-line and solid-line arrows, respectively. Arrowheads point to cells of the distal spermatheca. Expression from Papx-1::lacZ was observed in 59%, 97%, and 100% of animals in Sh4, Sh5, and spermatheca, respectively (n = 88). Expression from Papx-1::GFP was observed in 78%, 100%, and 100%, in Sh4, Sh5, and spermatheca, respectively (n = 56). We observed a more dynamic gonad pattern for Parg-1::GFP. Expression was not observed in L2 or L3 gonads (n = 12) and first appears in the sheath cells in the mid-L4, in Sh4 and Sh5 (12/12 gonad arms), and occasionally also in Sh3 (1/12). By the late L4, Sh4 and Sh5 continue to express Parg-1::GFP (6/6) with 2/6 also expressing the transgene in Sh1–3. In very young adults (before embryogenesis), expression remained in Sh4 and Sh5 in all animals but was less frequently observed in Sh1–3 (2/9 gonad arms). Finally, in adults bearing embryos (n = 48 gonad arms), 25% showed no expression. Expression was observed in 73% of Sh4–5, and 15% of these also showed expression in Sh3, whereas 2% showed more distal sheath expression. [Scale bars, 20 μm.]

The “proximal proliferation” (Pro) phenotype is a distinct hyperplastic phenotype in which two germ-line proliferation centers are seen in the adult: the normal niche-associated proliferative zone and a second ectopic zone situated at the opposite end of the oviduct, far from the normal niche. The two populations of proliferating germ cells—normal and ectopic—are separated by differentiated germ cells. At the ectopic site, the localized mass of cells undergoes uncontrolled proliferation. It is therefore referred to as a “tumor” (10) (Figs. 1A and 2).

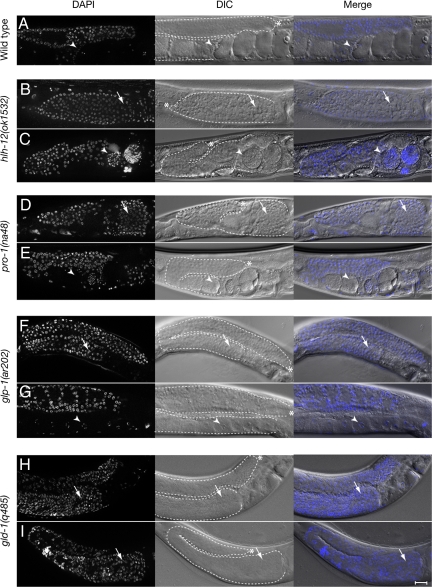

Fig. 2.

Suppression of proximal germ-line tumors by L1 RNAi feeding. (A–I) Representative gonad arms in fixed DAPI-stained worms. (A) Wild type grown on control RNAi bacteria (carrying the L4440 empty-vector plasmid). For the remaining images, each pair of panels includes control on the top (B, D, F, H) and apx-1(RNAi) on the bottom (C, E, G, I): (B, C) hlh-12(ok1532); (D, E) pro-1(na48); (F, G) glp-1(ar202); (H, I) gld-1(q485). hlh-12 encodes a basic helix–loop–helix transcription factor (45), pro-1 encodes an ortholog of yeast IPI3 (15), and gld-1 encodes a KH-domain protein (46). Arrows and arrowheads indicate undifferentiated and differentiated germ cells in the proximal oviduct, respectively. See Table 1 for quantification. [Scale bars, 20 μm.]

The Pro phenotype can occur as a result of mutations in a number of different genes encoding proteins with unrelated functions (11–19), and these genes act in distinct cell types, including cells of the somatic gonad and the germ line itself. Thus, whether a common cellular and molecular basis for proximal tumor formation could be found was unclear. Despite this, previous studies (15, 20) suggested that some Pro mutants share in common a delay in germ-line differentiation relative to somatic development. Therefore, we wondered whether a common cellular and molecular mechanism could be found to account for Pro tumor formation.

Here, we show that ectopic germ cell proliferation in C. elegans Pro mutants can be driven by a mechanism that we term the “latent niche.” We define a latent niche as a differentiated cell type that does not normally contact stem cells nor act as a niche but that can, under certain conditions, promote the inappropriate self-renewal, proliferation, or survival of competent cells with which it comes into contact. Our results demonstrate that the molecular mechanism for the latent niche leading to germ-line tumors is the inappropriate GLP-1/Notch activation from a proximal source of ligand. Out of the 10 C. elegans DSL-family ligands (21), apx-1 and arg-1 are expressed in the latent niche and largely account for its latent niche activity, while dsl-5 also contributes. We further demonstrate that the identity of the DSL ligand is not important because LAG-2, the DTC signal for normal germ-line development, can substitute for APX-1 in the latent niche role. Finally, we find that Notch signaling driven by ligands from the latent niche both promote and maintain proximal germ-line tumors. We propose that a similar latent niche mechanism may underlie tumorigenesis and metastasis in humans.

Results

The C. elegans Pro phenotype occurs as a secondary consequence of different primary defects caused by certain mutations of hlh-12, pro-1, and glp-1, genes with unrelated function and different expression patterns. Yet each case is associated with a delay in germ-line differentiation. This delay leads to the same inappropriate cell–cell contact between mitotically competent germ-line progenitors and specific gonadal sheath cells (Fig. 1A). In early stages of wild-type larval hermaphrodite development, germ cells are within the range of niche influence and all are undifferentiated. During normal larval development, gonad arm extension occurs in response to two separable processes: DTC migration (also separable from the DTC niche function) and robust germ-line proliferation. Niche-associated cells remain undifferentiated whereas germ cells beyond a certain distance from the DTC differentiate. Thus, differentiated germ cells first appear during development farthest from the niche (Fig. 1A).

A critical sequence of events during codevelopment of the germ line and soma is that germ cells escape the niche influence and begin to differentiate before the birth of neighboring (proximal) somatic cells (proximal sheath cells; Fig. 1A). By contrast, in Pro mutants germ-line differentiation is delayed relative to somatic gonad development, and germ-line differentiation begins after the birth of neighboring somatic gonad cells. For example, in hlh-12 Pro animals, early DTC migration is impaired (Fig. 1A) (18). Consequently, the niche continues to influence germ cells, and differentiation is delayed. As a result, newly born proximal somatic sheath cells inappropriately contact undifferentiated germ cells. We postulated that these sheath cells might then act as a latent niche, promoting the self-renewal and proliferation of undifferentiated germ cells that they inappropriately contact. Eventually, sufficient spatial separation occurs between the two sources of proliferation-promoting signals (distal normal niche and proximal latent niche), allowing germ-line differentiation to occur between them. A similar delay in differentiation and subsequent inappropriate cell–cell interaction occurs in pro-1 and glp-1 Pro mutants, albeit as a result of different primary defects. The Pro phenotype in pro-1 is due to a distal sheath defect that interferes with early robust germ-line proliferation, whereas glp-1 Pro is due to a germ-line-autonomous defect that elevates GLP-1/Notch activity (Fig. 1A) (13, 15, 20, 22). Previous studies showed that ablation of precursors to the proximal sheath cells could prevent tumor formation (22). On the basis of these observations, we postulated that a signal emanating from the proximal sheath cells might act as a latent niche signal and promote ectopic germ-line proliferation in mutants where the signal is received inappropriately.

Because maintenance of germ-line stem cells requires Notch activity, we further reasoned that a DSL-family ligand, a conserved family of ligands for Notch receptors (21, 23), might underlie ectopic germ-line proliferation in Pro mutants. To determine whether any of the 10 C. elegans predicted DSL ligands (21) could act as a latent niche signal, we asked which were expressed in the right cells (proximal sheath) at the right time (after germ-line differentiation begins) and whether reduction of their activity could suppress ectopic germ-line tumor formation.

We examined the expression patterns of reporters driven by promoter sequences from each of the predicted DSL ligands (Table S1) and found that two of them, apx-1 and arg-1, were expressed in the proximal sheath cells from the time that these cells are born in the mid-L4 stage. apx-1 reporters driven by a 9-kb region upstream of the apx-1 coding sequence [a nuclear-localized Papx-1::NLSlacZ (21) and Papx-1::GFP] show expression in the two proximal-most pairs of sheath cells and the four distal-most cells of the spermatheca (Fig. 1B). We confirmed the identity of these cells by position and expression of CEH-18 (Fig. S1) and lim-7::GFP (24, 25). This expression pattern suggests that apx-1 may be required for other processes that depend on proper function of these cells. We also constructed and examined a Parg-1::GFP reporter and found that it is expressed in proximal sheath cells (Fig. 1B). No gonad expression of similar reporters driven by the other DSL gene promoters was observed in the proximal sheath, including a dsl-5 reporter (Table S1), despite evidence of a functional role for this gene (see below). Thus, apx-1 and arg-1 are expressed in a subset of somatic gonad cells that contact only differentiated germ cells in the wild type but contact undifferentiated germ cells in Pro mutants (Fig. 1B).

If a particular DSL ligand is important for promoting proximal germ-line tumor formation, then removal of the ligand should suppress tumor formation. We therefore asked whether reducing DSL ligand gene activity by RNAi would suppress the formation of proximal tumors (Table S2). Because a lack of reporter gene expression does not preclude a functional role, each of the DSL ligand genes was tested for function in tumor formation. Our previous genetic and ablation studies suggested that pro-1(Pro) is most sensitive to removal of the proximal sheath (13, 15, 20, 22). Therefore, we first tested whether depletion of each putative ligand-encoding gene would suppress tumor formation in the pro-1 background and then further examined these in the glp-1(Pro) mutant background (Table 1, Mutants and/or L1 RNAi feeding and Table S2).

Table 1.

Suppression of proximal germ-line tumor formation

| Genotype | RNAi* | % Pro | n |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mutants and/or L1 RNAi feeding | |||

| hlh-12(ok1532) | Control† | 96 | 25‡ |

| hlh-12(ok1532) | apx-1(GC) | 13 | 24‡ |

| hlh-12(ok1532) | glp-1(JA) | 21 | 15‡ |

| Wild type | hlh-12(JA) | 33 | 71‡ |

| apx-1(or3) | hlh-12(JA) | 6 | 66‡ |

| pro-1(na48) | Control | 85 | 46 |

| pro-1(na48) | apx-1(GC) | 8 | 50 |

| pro-1(na48) | Control | 98†† | 427 |

| pro-1(na48) | apx-1(GC) | 33 | 46 |

| pro-1(na48) | apx-1(MV) | 67 | 46 |

| pro-1(na48) | arg-1(MV) | 48 | 110 |

| pro-1(na48) | dsl-5(MV) | 71 | 38 |

| pro-1(na48) | dsl-5(JA) | 98†† | 124 |

| pro-1(na48);arg-1(th7) | Control | 41 | 86 |

| pro-1(na48);arg-1(th7) | apx-1(GC) | 0 | 104 |

| pro-1(na48) | Control | 98 | 112 |

| pro-1(na48) | apx-1(GC) | 28 | 78 |

| pro-1(na48) | arg-1(MV) | 57 | 30 |

| pro-1(na48) | dsl-5(MV) | 60 | 58 |

| pro-1(na48) | apx-1(GC),arg-1(MV) | 27 | 109 |

| pro-1(na48);dsl-5(ok588) | Control | 31†† | 26 |

| pro-1(na48);dsl-5(ok588) | apx-1(GC) | 26†† | 84 |

| pro-1(na48);dsl-5(ok588) | arg-1(MV) | 27†† | 26 |

| pro-1(na48);dsl-5(ok588) | dsl-5(MV) | 31†† | 58 |

| pro-1(na48);dsl-5(ok588) | apx-1(GC),arg-1(MV) | 24†† | 41 |

| glp-1(ar202) | Control | 90** | 110 |

| glp-1(ar202) | apx-1(GC) | 82** | 142 |

| glp-1(ar202) | Control | 99†† | 132 |

| glp-1(ar202) | apx-1(GC) | 76 | 38 |

| glp-1(ar202) | apx-1(MV) | 82 | 92 |

| glp-1(ar202) | arg-1(MV) | 89 | 127 |

| glp-1(ar202) | arg-1(JA) | 100†† | 26 |

| glp-1(ar202) | dsl-5(MV) | 98†† | 250 |

| glp-1(ar202) | dsl-5(JA) | 95†† | 120 |

| glp-1(ar202) | Control | 99 | 172 |

| glp-1(ar202) | apx-1(GC) | 88 | 183 |

| glp-1(ar202) | arg-1(MV) | 86 | 181 |

| glp-1(ar202);arg-1(th7) | Control | 91 | 228 |

| glp-1(ar202);arg-1(th7) | apx-1(GC) | 76 | 177 |

| glp-1(ar202);apx-1(or3)§ | Control | 50†† | 34 |

| glp-1(ar202);apx-1(or3)§ | arg-1(MV) | 47†† | 40 |

| glp-1(ar202);dsl-5(ok588);arg-1(th7) | Control | 74 | 207 |

| glp-1(ar202);dsl-5(ok588);arg-1(th7) | apx-1(GC) | 42 | 225 |

| gld-1(q485) | Control | 100†† | 18 |

| gld-1(q485) | apx-1(GC) | 96†† | 28 |

| L1 RNAi feeding¶ | |||

| pro-1(na48) | Control | 83 | 30 |

| pro-1(na48) | apx-1(GC) | 3 | 40 |

| pro-1(na48);naEx152[Papx-1::lag-2] | Control | 100†† | 11 |

| pro-1(na48);naEx152[Papx-1::lag-2] | apx-1(GC) | 96†† | 23 |

| Adult RNAi feeding‖ | |||

| pro-1(na48) | Control | 96 | 28 |

| pro-1(na48) | apx-1(GC) | 45 | 40 |

| pro-1(na48) | Control | 97 | 32 |

| pro-1(na48) | glp-1(JA) | 48 | 44 |

*Due to the variability of RNAi, results are separated into parallel controlled experiments. RNAi reagents were all sequence verified and are indicated as follows: the apx-1(RNAi) reagent was derived from the apx-1(cDNA) (pGC304; see Materials and Methods); JA and MV indicate feeding clones from the Kamath et al. (42) and Rual et al. (43) libraries, respectively.

†Control RNAi is the L4440 ″empty vector″ plasmid in E. coli HT115.

‡Penetrance of Pro was scored as a percentage of animals displaying a severe Mig defect (includes incomplete anterior or posterior migration up to those that had just completed the dorsal turn). For hlh-12(ok1532), 100% displayed some Mig defect, 62% of which were considered severe.

§Homozygous glp-1(ar202); apx-1(or3) mutants were progeny of heterozygous mothers of the genotype glp-1(ar202);apx-1(or3)/nT1[qIs51]. The or3 allele encodes a C334Y missense mutation. The or3 allele is likely a stronger loss-of-function allele than zu183 [a transposon insertion in the 3′ UTR (44)]. Double mutant pro-1(na48);apx-1(or3) animals were not viable.

¶Sibling animals of both genotypes (with and without naEx152, and segregating from mothers of the genotype pro-1(na48); naEx152[Papx-1::lag-2]) were scored from L4440 control or apx-1 RNAi.

‖Individual Pro gonad arms 1 day after transfer to indicated RNAi treatment; see Fig. 3B.

**,††For statistics, all experiments compared to relevant negative controls in the same experimental set gave P < 0.001 in a one-sided Fisher exact test with the exception of ** where P < 0.05 and †† where no significant differences were observed (P > 0.3).

In short, we found the strongest RNAi effects with 3 of the 10 putative DSL ligand genes: apx-1 had the strongest effect on the penetrance of the pro-1 Pro phenotype, reducing it from 98% to 33%, whereas arg-1 and dsl-5 RNAi also suppressed Pro (to 48% and 71%, respectively; Table 1, Mutants and/or L1 RNAi feeding and Table S2). Double mutant combinations of pro-1(na48) with arg-1 and dsl-5 null alleles showed stronger suppression (to 41% and 31%, respectively; Table 1; pro-1;apx-1 double mutant combination causes embryonic lethality). Remarkably, RNAi reduction of apx-1 in a pro-1;arg-1 double mutant completely suppressed tumor formation, suggesting that these two ligands together can account for the tumor-promoting activity from the proximal sheath in the pro-1 mutant (Table 1, Mutants and/or L1 RNAi feeding) because ablation of the proximal sheath cells also abolishes tumor formation (22).

Tumor formation caused by elevated glp-1 activity in the glp-1(Pro) mutant glp-1(ar202) was also partially suppressed to the wild-type pattern upon reduction of apx-1 and arg-1 (to 50% and 91%, respectively, Table 1). Although depletion of dsl-5 by RNAi did not suppress glp-1(Pro), the dsl-5 null allele did contribute to suppression [74% versus 91% Pro with and without dsl-5(ok588) in glp-1(ar202);arg-1(th7) and 42% versus 76% Pro in glp-1(ar202);arg-1(th7);apx-1(RNAi) with and without dsl-5(ok588); Table 1, Mutants and/or L1 RNAi feeding]. The strongest level of suppression is close to, but not as strong as, the 22% Pro observed previously by ablation of the proximal sheath (see ref. 22). Some differences in suppression of pro-1(na48) and glp-1(ar202) are likely attributable to a residual ligand-independent activity of glp-1(ar202). Other differences may also exist, such as ligand-specific sensitivity of the mutant receptor because the Pro phenotype of glp-1(ar202) is weakly suppressed by dsl-7(RNAi), whereas the otherwise more sensitive Pro phenotype of pro-1(na48) is not (Table S2).

To further test our postulated mechanism of tumor formation (Fig. 1A), we examined the effect of apx-1(RNAi) in additional tumor-forming mutants. Consistent with our model, hlh-12 tumors are highly dependent on apx-1 and glp-1 activity (Table 1, Mutants and/or L1 RNAi feeding and Fig. 2). Finally, we asked whether reducing apx-1 activity suppressed tumor formation caused by loss of GLD-1, an RNA-binding protein that acts downstream of glp-1 in the germ line to promote differentiation. Tumors in gld-1 mutants are not associated with a delay in the onset of differentiation (26, 27). Consistent with our model, GLD-1 tumor formation is not suppressed by a reduction in apx-1 activity (Table 1). We conclude that in pro-1, glp-1, and hlh-12 Pro mutants DSL ligands are the key components of the latent niche activity. In particular, APX-1 and ARG-1 in the proximal sheath drive proximal germ-line tumor formation in germ cells as a result of an inappropriate juxtaposition of the proximal sheath with undifferentiated germ cells.

To determine whether the specific identity of the DSL-family ligand was critical for its latent germ-line proliferation-promoting function, we tested whether LAG-2 could substitute for APX-1 in its latent niche function. We expressed lag-2 from the apx-1 promoter and observed the Pro phenotype in pro-1(na48) animals (still expressing endogenous apx-1(+)). We then treated these animals with RNAi directed against endogenous apx-1 and observed that, whereas control siblings that lacked the transgene exhibited a strong reduction in the penetrance of the Pro phenotype, the prevalence of tumor formation in pro-1;apx-1(RNAi) animals expressing Papx-1::lag-2 was not reduced (Table 1, L1 RNAi feeding and Fig. 3A). Because the lag-2 transgene is driven from the same promoter as the apx-1 expression reporters, these results confirm that APX-1 activity in cells marked by reporter expression is sufficient for the latent niche activity. We conclude that the specific identity of the DSL ligand in the latent niche is not critical.

Fig. 3.

Control of proximal tumors. (A) LAG-2 can replace APX-1 in the latent niche role. Gonad arms from live worms raised on the indicated RNAi bacteria. In each RNAi treatment, siblings were scored from mothers of the genotype pro-1(na48); naEx152[Papx-1::lag-2]. Control is L4440 RNAi; graph shows quantification. (B) Suppression of adult tumors by reducing ligand or receptor activity. (Upper, day 1) Gonad arms from representative early adult pro-1(na48) animals raised to early adulthood on control L4440 RNAi. (Lower, day 2) Same individual gonad arm in the panel above after an additional day of feeding on bacteria inducing the indicated RNAi. Arrows indicate undifferentiated germ cells; arrowheads indicate differentiated germ cells. See Table 1 for quantification. [Scale bars in A and B, 20 μm.] (C) Generalized latent niche mechanism. (Row 1) Normal conditions: latent niche mechanism inactive. Cell–cell contacts between the latent niche cell (blue) and its unresponsive neighbors (green) do not cause inappropriate self-renewal or proliferation. Although the latent niche is producing a potential niche-like renewal-promoting signal, under normal conditions, neighboring cells do not respond to this signal. (Rows 2 and 3) Tumor initiation: latent niche mechanism active. Several different scenarios could lead to activation of the latent niche mechanism, two of which are schematized here. (Row 2) A delay in differentiation before the appearance of the latent niche ultimately juxtaposes the latent niche with proliferation-competent cells (yellow); (Row 3) anatomical changes or the migration of potentially self-renewing tumor cells juxtaposes proliferation-competent cells with a resident latent niche. Time proceeds from left to right. Dotted lines indicate the positions of cells not yet born or newly opened vacancies.

To determine whether activity of the latent niche ligand APX-1 or the Notch receptor (GLP-1) is required continuously to maintain ectopic proliferation, we interfered with their activity after tumor formation and asked whether the tumor cells differentiate. We reduced apx-1 or glp-1 activity by RNAi in adult pro-1 animals after a tumor had formed. Our results show that in over half of the gonad arms, ectopic germ-line tumor cells differentiated (Table 1, Adult RNAi feeding and Fig. 3B). These results demonstrate that maintenance of ectopic proliferating germ-line cells requires continuous Notch pathway activation.

Because stem cell niches both promote self-renewal and produce cells that retain the ability to differentiate, our results also suggest that the latent niche is acting similarly to a stem cell niche. We reasoned that if germ cells of the tumor were acting like normal stem cells, then they should undergo differentiation if they could move out of the range of the latent niche signal. Consistent with this hypothesis, we found evidence of “reverse” polarity such that germ cells of the proximal tumor appear to differentiate at the distal border of the tumor (Fig. S2). Determining what drives the apparent uncontrolled growth in the proximal tumors relative to the DTC-associated distal germ line will be of interest.

We examined two additional indicators of normal differentiation using the adult RNAi ligand-withdrawal strategy in pro-1 mutants. In the wild type, a substantial proportion of female germ cells in meiotic prophase (that is, differentiated) undergo apoptosis (28). We asked whether similar cell death could be observed in tumors undergoing differentiation. Indeed, we observe cell death after withdrawal of apx-1 or arg-1 (Table S3). Finally, we examined the expression of GLD-1::GFP, a marker of differentiation (29, 30). We observed an increased penetrance of GLD-1 reporter expression in the proximal germ line of pro-1 mutants after exposure to apx-1, arg-1, or dsl-5 RNAi (Table S3). Taken together, these data indicate that proximal tumors deprived of the latent niche signal exhibit differentiation features similar to those of germ cells differentiating from the normal stem cell niche.

Discussion

The data presented here provide evidence that inappropriate cell proliferation can be maintained by a latent niche mechanism. The ectopic proliferation examined here results from three independent genetic defects (hlh-12, pro-1, and glp-1) that affect three different cell types (DTC, sheath, and germ line, respectively). Each causes a delay in germ-line differentiation, resulting in inappropriate cell–cell contact that revealed the presence of a latent niche. Reducing DSL signals from the latent niche suppressed ectopic germ-line proliferation. Thus, the latent niche model provides a unifying cellular and molecular mechanism for tumor formation in these mutants. In addition, the maintenance of ectopic germ-line tumors was dependent on continuous signaling from the latent niche.

We propose the latent niche mechanism as a general paradigm for tumorigenesis whereby a cancer stem cell (or “tumor-propagating cell”) or any renewal-competent cell contacts a latent niche to seed a new tumor or metastasis (Fig. 3C). The latent niche differs conceptually from a “premetastatic niche” in that the activity of the latent niche need not be induced by a primary tumor (e.g., ref. 31). It differs from an ectopic niche (e.g., ref. 32) in that the cell providing the self-renewal signal is normal. It also differs from the role of stromal cells recruited into a tumor (e.g., ref. 33) in that the latent niche can retain its normal anatomical position and function and need not be recruited into the tumor to promote self-renewal. Finally, the latent niche differs from a normal stem cell niche that is vacated and repopulated (34, 35) in that normally the latent niche does not act as a niche. Nonetheless, a latent niche mechanism may act in conjunction with these mechanisms, other tumor-cell-autonomous mechanisms, or both to promote inappropriate self-renewal of neighboring cells. For example, Podsypanina et al. recently demonstrated that under experimental conditions normal mammary cells can persist in the lung for extended periods and subsequently become foci for new tumor growth when they are transformed (36). It is conceivable that they are maintained by a latent niche mechanism and that self-renewal or survival signals could predispose such cells to progress to tumors after the acquisition of subsequent transforming mutations (36, 37).

An important aspect of this proposed mechanism is that neither the tumor cells nor the latent niche cells need be genetically compromised to initiate or sustain a tumor. That is, proliferation-competent cells need only contact a latent niche. As in our system, this feature implies that developmental defects—be they genetically or environmentally induced—could lead to tumor-promoting inappropriate cell–cell contacts. This feature further suggests a mechanism whereby nongenetic anatomical defects could promote tumorigenesis, such as anatomical changes after surgery or injury, or shifts in cell–cell contacts during normal processes such as aging.

Determining whether a similar latent niche mechanism contributes to tumor initiation or metastasis in humans will be of interest. Conceivably, self-renewal signals, even different ligands of the same family that activate potentially oncogenic receptors, could be present in a latent form in many tissue types and could contribute to preferential sites of tumor or metastasis “seeding” (38). If so, then latent niches and the signals that they produce may constitute new therapeutic targets.

Materials and Methods

Plasmids.

Plasmids were constructed using standard methods; all pPD vectors used are from the Fire laboratory vector kit available from Addgene (A Fire, S Xu, J Fleenor, J Ahnn, and G Seydoux, personal communication).

pGC399[Papx-1::GFP::let-858(3′UTR)]: The apx-1 promoter (≈9 kb upstream of ATG) was amplified by PCR from N2 genomic DNA with primers caaaggatccATCGAAATTGGTTACCTATCGGC and caaaggtaccAGTACAGGATCGTGTGCTAG-AAGG, digested, and inserted into BamHI/KpnI pPD95.79 [pGC396]. The GFP-unc-54(3′UTR) was replaced with GFP-let-858(3′UTR) from pPD117.01 between AgeI and ApaI.

pGC398[Papx-1::lag-2(cDNA)::let-858(3′UTR)]: lag-2 genomic DNA (ATG to TAG) was amplified by PCR from N2 worms with primers cccaaagagctcATGATCGCTTACTTCCTC and cccaaagctagcCTAGACATAGTGACAGGC, digested, and inserted into pGC76 (39) with SacI/NheI [pGC171]. The lag-2 BstBI/NheI fragment was replaced with BstBI/XbaI of lag-2 cDNA (accession X77495) [pGC386, lag-2(cDNA)::let-858(3′UTR)]. Subsequently, lag-2(cDNA)::let-858(3′UTR) was removed (XmaI/ApaI) and inserted into pGC396, replacing GFP::unc-54(3′UTR).

pGC474[Parg-1::GFP]: pZJ02 (40) was digested with SphI and BglII, and the resulting 6.2-kb arg-1 upstream region was inserted into an SphI/BamHI digested pPD95.75.

pGC494[Pdsl-5::4NLS-GFP]: The ≈3.5-kb upstream region of dsl-5 was amplified by PCR with primers CAACTGCAGCGCTCCATTCGGAGGATGGTCGAAG and CAAGGATCCGTTGAAATGTTGATAATGAGATGGAG. The resulting product was digested with PstI and BamHI and inserted in likewise digested pPD129.57, replacing the rpl-28 promoter.

Worm Methods.

Standard methods were used for worm husbandry and genetics (41). naEx152, naEx156, and naEx180 were generated by injection of 100 ng/μL pRF4 as a transformation marker in addition to pGC398, pGC399 (each at 1 ng/μL), and pGC474 (10 ng/μL), respectively. Existing strains used: wild type (N2), GC585 pro-1(na48)/mIn1[dpy-10(e128) mIs14], GC833 glp-1(ar202), BS3156 unc-13(e51) gld-1(q485)/hT2[dpy-18(h662)]; +/hT2[bli-4(e937)]. Strains generated in this study: GC794 glp-1(ar202);apx-1(or3)/nT1[qIs51], GC851 hlh-12(ok1532)/nT1[qIs51], GC1015 pro-1(na48)/mIn1[dpy-10(e128) mIs14];naEx152[Papx-1::lag-2], GC1051 naEx180[Parg-1::GFP], GC1053 ozIs5[gld-1::GFP];glp-1(ar202), GC1059 pro-1(na48)/mInI[mIs14 dpy-10(e128)];arg-1(th7), GC1063 glp-1(ar202);arg-1(th7), GC1064 ozIs5[gld-1::GFP];pro-1(na48)/mInI[mIs14 dpy-10(e128)], GC1074 pro-1(na48)/mIn1[mIs14 dpy-10(e128)];dsl-5(ok588), GC1090 glp-1(ar202);dsl-5(ok588);arg-1(th7).

arg-1(th7) deletes 853 bp in the arg-1 locus, including exons 1–3 that encode the DSL protein motif, and is flanked by sequences: TACGTTGCTTGTTTTTGGCTATCG… CCACAATGCACAGCAGTATGAC. It was detected by PCR product size using primers AGTAGCATCACTGCTTGTCA and ATCAGTCCATCTTCGGGCCT and by failure to generate a product from a primer pair internal (TGGAGCACAGGAAAATGGTG) and external (AGTAGCATCACTGCTTGTCA) to the deletion.

dsl-5(ok588) was detected by PCR product size generated with primers ATTGGTGTCGCTTTCCTTTG and TGTACGGGTTCGAACATTCA and for failure to generate a product with primers TGTACGGGTTCGAACATTCA (external) and AAGGTCTGGCTACAGCAGCC (internal) to the deletion.

RNAi.

L1 animals were grown at 20 °C, synchronized, placed on RNAi-inducing bacteria, shifted to 25 °C, fixed, and DAPI-stained 2 days later.

For adult RNAi, synchronized L1 GC585 animals were grown on L4440-containing bacteria and shifted to 25 °C. As young adults, individuals were imaged and then placed on L4440, apx-1(RNAi) [pGC304; (6)] or glp-1(RNAi) (42). The same gonad arm of the same individual was imaged 1 day later.

Additional methods can be found in SI Methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank Iva Greenwald (HHMI/Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, New York, NY), Tim Schedl (Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO), the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center, the C. elegans Gene Knockout Consortium, and the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank for strains, reagents, or both, and Darrell Killian, Jeremy Nance, Ruth Lehmann, Eva Hernando, Claude Desplan, and the anonymous reviewers for valuable comments on the manuscript. We thank Jie Zhao and Josef Capua for technical assistance. This work was supported by the March of Dimes Foundation Grant 1-FY06 874 (to E.J.A.H.) and by National Institutes of Health Grants R01GM61706 (to E.J.A.H.) and R15DE018519 (to A.K.C.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0903768106/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Hubbard EJ. Caenorhabditis elegans germ line: A model for stem cell biology. Dev Dyn. 2007;236:3343–3357. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kimble J, Crittenden SL. Controls of germline stem cells, entry into meiosis, and the sperm/oocyte decision in Caenorhabditis elegans. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2007;23:405–433. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.23.090506.123326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hansen D, Schedl T. The regulatory network controlling the proliferation-meiotic entry decision in the Caenorhabditis elegans germ line. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2006;76:185–215. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(06)76006-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lambie EJ, Kimble J. Two homologous regulatory genes, lin-12 and glp-1, have overlapping functions. Development. 1991;112:231–240. doi: 10.1242/dev.112.1.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Henderson S, Gao D, Lambie E, Kimble J. lag-2 may encode a signaling ligand for the GLP-1 and LIN-12 receptors of C. elegans. Development. 1994;120:2913–2924. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.10.2913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nadarajan S, Govindan JA, McGovern M, Hubbard EJ, Greenstein D. MSP and GLP-1/Notch signaling coordinately regulate actomyosin-dependent cytoplasmic streaming and oocyte growth in C. elegans. Development. 2009;136:2223–2234. doi: 10.1242/dev.034603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berry L, Westlund B, Schedl T. Germ-line tumor formation caused by activation of glp-1, a Caenorhabditis elegans member of the Notch family of receptors. Development. 1997;124:925–936. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.4.925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kimble J, White J. On the control of germ cell development in Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev Biol. 1981;81:208–219. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(81)90284-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karp X, Greenwald I. Multiple roles for the E/Daughterless ortholog HLH-2 during C. elegans gonadogenesis. Dev Biol. 2004;272:460–469. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pinkston JM, Garigan D, Hansen M, Kenyon C. Mutations that increase the life span of C. elegans inhibit tumor growth. Science. 2006;313:971–975. doi: 10.1126/science.1121908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seydoux G, Schedl T, Greenwald I. Cell-cell interactions prevent a potential inductive interaction between soma and germline in C. elegans. Cell. 1990;61:939–951. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90060-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Francis R, Barton M, Kimble J, Schedl T. gld-1, a tumor suppressor gene required for oocyte development in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 1995;139:579–606. doi: 10.1093/genetics/139.2.579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pepper AS, Killian DJ, Hubbard EJ. Genetic analysis of Caenorhabditis elegans glp-1 mutants suggests receptor interaction or competition. Genetics. 2003;163:115–132. doi: 10.1093/genetics/163.1.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Subramaniam K, Seydoux G. Dedifferentiation of primary spermatocytes into germ cell tumors in C. elegans lacking the Pumilio-like protein PUF-8. Curr Biol. 2003;13:134–139. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Killian DJ, Hubbard EJ. C. elegans pro-1 activity is required for soma/germline interactions that influence proliferation and differentiation in the germ line. Development. 2004;131:1267–1278. doi: 10.1242/dev.01002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bender AM, Wells O, Fay DS. lin-35/Rb and xnp-1/ATR-X function redundantly to control somatic gonad development in C. elegans. Dev Biol. 2004;273:335–349. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Voutev R, Killian DJ, Ahn JH, Hubbard EJ. Alterations in ribosome biogenesis cause specific defects in C. elegans hermaphrodite gonadogenesis. Dev Biol. 2006;298:45–58. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tamai KK, Nishiwaki K. bHLH transcription factors regulate organ morphogenesis via activation of an ADAMTS protease in C. elegans. Dev Biol. 2007;308:562–571. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bessler JB, Reddy KC, Hayashi M, Hodgkin J, Villeneuve AM. A role for Caenorhabditis elegans chromatin-associated protein HIM-17 in the proliferation vs. meiotic entry decision. Genetics. 2007;175:2029–2037. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.070987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pepper AS, Lo TW, Killian DJ, Hall DH, Hubbard EJ. The establishment of Caenorhabditis elegans germline pattern is controlled by overlapping proximal and distal somatic gonad signals. Dev Biol. 2003;259:336–350. doi: 10.1016/s0012-1606(03)00203-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen N, Greenwald I. The lateral signal for LIN-12/Notch in C. elegans vulval development comprises redundant secreted and transmembrane DSL proteins. Dev Cell. 2004;6:183–192. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(04)00021-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Killian DJ, Hubbard EJ. Caenorhabditis elegans germline patterning requires coordinated development of the somatic gonadal sheath and the germ line. Dev Biol. 2005;279:322–335. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.D'Souza B, Miyamoto A, Weinmaster G. The many facets of Notch ligands. Oncogene. 2008;27:5148–5167. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Greenstein D, et al. Targeted mutations in the Caenorhabditis elegans POU homeo box gene ceh-18 cause defects in oocyte cell cycle arrest, gonad migration, and epidermal differentiation. Genes Dev. 1994;8:1935–1948. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.16.1935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hall DH, et al. Ultrastructural features of the adult hermaphrodite gonad of Caenorhabditis elegans: Relations between the germ line and soma. Dev Biol. 1999;212:101–123. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Francis R, Maine E, Schedl T. Analysis of the multiple roles of gld-1 in germline development: Interactions with the sex determination cascade and the glp-1 signaling pathway. Genetics. 1995;139:607–630. doi: 10.1093/genetics/139.2.607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jones A, Francis R, Schedl T. GLD-1, a cytoplasmic protein essential for oocyte differentiation, shows stage- and sex-specific expression during Caenorhabditis elegans germline development. Dev Biol. 1996;180:165–183. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.0293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gumienny TL, Lambie E, Hartwieg E, Horvitz HR, Hengartner MO. Genetic control of programmed cell death in the Caenorhabditis elegans hermaphrodite germline. Development. 1999;126:1011–1022. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.5.1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hansen D, Wilson-Berry L, Dang T, Schedl T. Control of the proliferation versus meiotic development decision in the C. elegans germline through regulation of GLD-1 protein accumulation. Development. 2004;131:93–104. doi: 10.1242/dev.00916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schumacher B, et al. Translational repression of C. elegans p53 by GLD-1 regulates DNA damage-induced apoptosis. Cell. 2005;120:357–368. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kaplan RN, et al. VEGFR1-positive haematopoietic bone marrow progenitors initiate the pre-metastatic niche. Nature. 2005;438:820–827. doi: 10.1038/nature04186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Song X, Call GB, Kirilly D, Xie T. Notch signaling controls germline stem cell niche formation in the Drosophila ovary. Development. 2007;134:1071–1080. doi: 10.1242/dev.003392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Karnoub AE, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells within tumour stroma promote breast cancer metastasis. Nature. 2007;449:557–563. doi: 10.1038/nature06188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kai T, Spradling A. An empty Drosophila stem cell niche reactivates the proliferation of ectopic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:4633–4638. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0830856100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brawley C, Matunis E. Regeneration of male germline stem cells by spermatogonial dedifferentiation in vivo. Science. 2004;304:1331–1334. doi: 10.1126/science.1097676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Podsypanina K, et al. Seeding and propagation of untransformed mouse mammary cells in the lung. Science. 2008;321:1841–1844. doi: 10.1126/science.1161621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weinberg RA. Leaving home early: Reexamination of the canonical models of tumor progression. Cancer Cell. 2008;14:283–284. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Paget S. The distribution of secondary growths in cancer of the breast. Lancet. 1889;1:571–573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Voutev R, Hubbard EJ. A “FLP-Out” system for controlled gene expression in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 2008;180:103–119. doi: 10.1534/genetics.108.090274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhao J, Wang P, Corsi AK. The C. elegans Twist target gene, arg-1, is regulated by distinct E box promoter elements. Mech Dev. 2007;124:377–389. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2007.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brenner S. The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 1974;77:71–94. doi: 10.1093/genetics/77.1.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kamath RS, et al. Systematic functional analysis of the Caenorhabditis elegans genome using RNAi. Nature. 2003;421:231–237. doi: 10.1038/nature01278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rual JF, et al. Toward improving Caenorhabditis elegans phenome mapping with an ORFeome-based RNAi library. Genome Res. 2004;14:2162–2168. doi: 10.1101/gr.2505604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mickey K, Mello C, Montgomery M, Fire A, Priess J. An inductive interaction in 4-cell stage C. elegans embryos involves APX-1 expression in the signalling cell. Development. 1996;122:1791–1798. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.6.1791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Okkema PG, Krause M. Transcriptional regulation. WormBook. 2005;2005:1–40. doi: 10.1895/wormbook.1.45.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jones A, Schedl T. Mutations in gld-1, a female germ cell-specific tumor suppressor gene in Caenorhabditis elegans, affect a conserved domain also found in Src-associated protein Sam68. Genes Dev. 1995;9:1491–1504. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.12.1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.