Abstract

Methylation of CpG islands in gene promoter regions is a major molecular mechanism of gene silencing and underlies both cancer development and progression. In molecular oncology, testing for the CpG methylation of tissue DNA has emerged as a clinically useful tool for tumor detection, outcome prediction, and treatment selection, as well as for assessing the efficacy of treatment with the use of demethylating agents and monitoring for tumor recurrence. In addition, because CpG methylation occurs early in pre-neoplastic tissues, methylation tests may be useful as markers of cancer risk in patients with either infectious or inflammatory conditions. The Methylation Working Group of the Clinical Practice Committee of the Association of Molecular Pathology has reviewed the current state of clinical testing in this area. We report here our summary of both the advantages and disadvantages of various methods, as well as the needs for standardization and reporting. We then conclude by summarizing the most promising areas for future clinical testing in cancer molecular diagnostics.

CpG-island methylation of gene promoter regions plays a major role in regulation of gene expression. CpG islands have been defined as genomic regions with a minimum of 200 bp, with % G+C greater than 50 and with observed/expected CpG ratio above 60%.1 More recently, studies have further defined CpG islands as regions of DNA greater than 500 bp with a G+C equal to or greater than 55% and observed CpG/expected CpG of 0.65.2 In actively transcribed genes the CpG sites in CpG islands of promoter regions are unmethylated, whereas increased cytosine methylation in the island CpG sites is associated with reduced gene expression and possible gene silencing.

Gene regulation by CpG methylation is involved in a large spectrum of biological processes, from development to aging, including inflammatory and infectious diseases, and cancer. The availability of molecular techniques to evaluate the methylation status of CpG islands in cancer related genes has prompted an explosion of studies in this area, and CpG methylation tests are emerging as clinically useful tests. CpG hypermethylation is critical to silencing of the expression of tumor suppressor genes, such as those that encode CDKN2B (p15), CDKN2A (p16), and O-6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase (MGMT), as well as globally regulating differentiation programs in many tumor types. The levels of CpG methylation have thus been used to subclassify tumors,3 predict response to chemotherapeutic agents that are metabolized or antagonized by cellular enzymes regulated by promoter methylation,4 and to assess the effects of methylating and demethylating therapies. In tumors in which CpG methylation silencing of particular suppressor genes is highly prevalent, the levels of such methylated DNA in blood or body fluids may be indicative of the presence of cancer cells or their circulating DNA.5,6

In this report we compare the current techniques and methodological considerations for assessing DNA CpG methylation and summarize the current status of CpG methylation testing with emphasis on neoplasia. Specific sections cover: 1) current methods for clinical testing of CpG methylation and the decision-making criteria for assay selection and validation requirements; 2) applications of CpG methylation testing for cancer detection, prognosis, and monitoring using tumor tissue, cell-free plasma and serum, and cytological and other biological samples; and, 3) the potential use of methylation interference and monitoring of CpG methylation status for prediction of tumors related to bacterial and viral infections.

To promote standardization in clinical reporting, we have used Human Genome Organization (HUGO) gene nomenclature throughout the text (http://www.genenames.org/index.html). A table listing the standard gene names used in this document with the common names is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

HUGO Gene Nomenclature Committee-Approved Symbols for Genes Discussed in the Text

| Symbol | Common name |

|---|---|

| APC | adenomatous polyposis coli |

| CACNA1G | calcium channel, voltage-dependent, T type alpha-1G subunit |

| CADM1 | cell adhesion molecule 1 (IGSF4) |

| CCND2 | cyclin D2 |

| CDH1 | cadherin 1 (E-cadherin) |

| CDH13 | cadherin 13 (H-cadherin) |

| CDKN2A | cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A (p16) |

| CDKN2B | cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2B (p15) |

| CRABP1 | cellular retinoic acid binding protein 1 |

| DAPK1 | death-associated protein kinase 1 |

| DNMT | DNA methyltransferase |

| ESR1 | estrogen receptor alpha |

| FHIT | fragile histidine triad |

| FRBP3 | fatty acid binding protein 3, muscle and heart (mammary-derived growth inhibitor, MDGI) |

| GSTP1 | glutathione S-transferase pi |

| HIC1 | hypermethylated in cancer 1 |

| HSD17B4 | hydroxysteroid (17-beta) dehydrogenase 4 |

| HSIL | high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion |

| IGF2 | insulin-like growth factor 2 |

| LATS1 | large tumor suppressor, homolog 1 |

| LATS2 | large tumor suppressor, homolog 2 |

| LINE | long interspersed nucleotide element |

| MGMT | O-6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase |

| MYOD1 | myogenic differentiation 1 |

| NEUROG1 | neurogenin 1 |

| PGR | progesterone receptor |

| PSA | prostate specific antigen |

| RARB | retinoic acid receptor beta |

| RASSF1 | RAS association (RalGDS/AF-6) domain family 1 |

| RUNX3 | runt-related transcription factor 3 |

| SFRP1 | secreted frizzled-related protein 1 (SARP2) |

| SOCS1 | suppressor of cytokine signaling 1 |

| TMEFF2 | transmembrane protein with EGF-like and two follistatin-like domains 2 (HPP1, hyperplastic polyposis 1) |

| TWIST1 | twist homolog 1 |

Current Methods Used for CpG Methylation Testing

Analysis of CpG methylation requires some method of discriminating between the methylated and unmethylated DNA sequences, usually following PCR amplification of targeted sequence(s). Post-PCR detection techniques routinely used to differentiate methylated and unmethylated DNA include capillary electrophoretic separation, dideoxynucleotide sequencing,7 pyrosequencing,8 mass spectrometry,3,9 high performance liquid chromatography,10 and array hybridization.11,12,13,14,15,16,17

Technical Considerations in the Bisulfite Conversion Step

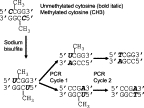

The majority of methods for methylation analysis begin with the conversion by sodium bisulfite of unmethylated cytosine to uracil (and then to thymine following in vitro DNA synthesis). By contrast, methylated cytosines are largely protected from this conversion process (Figure 1). Bisulfite treatment thus creates different sequences in methylated and unmethylated fragments, which can be detected by a variety of techniques.

Figure 1.

Bisulfite modification of DNA for methylation assays. Bisulfite modification converts unmethylated cytosine to uracil, while methylated cytosine is not modified. After PCR, uracil is replaced by thymine on the newly synthesized DNA strands.

However, the effects of bisulfite treatment on DNA are harsh and difficult to control and often result in significant DNA degradation of up to 85% to 95% of target sequences.18 This reduction in DNA template can greatly affect assay performance, including introducing PCR bias in amplification of sequences.19 Furthermore, the stability of bisulfite-treated DNA is reduced due to nucleotide mispairing and incomplete complementarity. Therefore, in this initial step, one needs to optimize the conditions required for full bisulfite conversion of unmethylated cytosine to uracil and yet minimize the degradative effects of this treatment on DNA.

Although there are minimal data on the effects of temperature and time of storage on the stability of bisulfite-treated DNA, most laboratories analyze bisulfite-converted DNA soon after conversion to minimize further DNA degradation. Until more data are available, ultra-low temperature storage conditions (−70°C or below) should be used if converted DNA must be stored before analysis. Published detailed studies to determine the effect of storage of bisulfite-treated DNA are needed. It is also advisable to include appropriate controls to validate the results obtained with such DNA.20 Another approach to minimize DNA loss has been to perform bisulfite conversion of DNA directly in tissue lysates.21 This method may be particularly useful for smaller samples. In practice, small samples are those that yield limited microgram amounts of DNA, such as tissue samples that are few millimeters in size, as are those obtained as endoscopic or needle biopsies. Alternatively, to decrease loss of DNA during bisulfite treatment, isolated DNA can be immobilized on nylon22 or in agarose.23 While complicated, bisulfite conversion can be reproducible and can be reliably used for quantitative analysis of DNA methylation (see below).21

Qualitative and Quantitative CpG Methylation Detection after Bisulfite Conversion

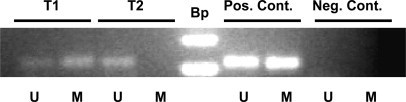

There is a wide variety of PCR-based detection methods,24 including those in which the sequence differences between bisulfite-converted and unconverted cytosines are incorporated into the primers used for amplification, so-called methylation-specific PCR (MSP). Examples of MSP are represented in Figure 2. Alternatively, in methylation-independent PCR, the primer sequences do not function to differentiate methylated and unmethylated DNA, but rather they are detected by another method. The advantages and disadvantages of each of the techniques are compared in Table 2.

Figure 2.

Methylation of the MLH1 gene CpG island promoter region detected by methylation specific PCR (MSP). After sodium bisulfite conversion of genomic DNA from colon cancer tumor samples (T1 and T2) or positive control DNA (Pos. Cont.), PCR was performed with the primer pair specific for methylated MLH1 DNA (M) or with the primer pair specific for the unmethylated MLH1 sequence (U). The negative control is a PCR reaction without DNA template. The DNA size ladder (Bp) is indicated. The presence of a PCR product in the lanes labeled (M) indicates the presence of CpG methylation in the sample T1 and in the positive control. For sample T2 no MLH1 CpG methylation is detected.

Table 2.

Comparison of Quantitative MSP and MIP Assays for Quantitative Assessment of CpG Methylation

| Methylation-specific quantitative PCR (MethyLight, etc.) | Methylation-independent PCR (for subsequent pyrosequencing, mass spectrometry, COBRA, etc.) | |

|---|---|---|

| Basic characteristics | Quantification during PCR | Quantification after PCR; not specific for the methylated or unmethylated sequences |

| Paraffin-embedded tissue | Usable | Usable |

| Precision | Good | Good, especially at high-level methylation |

| Accuracy | Good | Good, especially at high-level methylation |

| Monitoring of complete bisulfite conversion | By amplification of a non-CpG genomic reference* | By the presence of non-CpG cytosine in templates that should be completely converted |

| Genomic reference to measure the amount of input bisulfite-converted DNA | Necessary* | Unnecessary (measuring both methylated and unmethylated sequences) |

| Resolution | Lower; block of CpG sites coincident with primer and/or probe sequences | Very high (single nucleotide level) |

| Analytical sensitivity | Very high (1% methylated sequence) | 2% to10% methylated sequence (depending on subsequent detection method) |

| PCR design | Easy for high density CpG sites (applicable to most CpG islands) | Easy when there is a small CpG island abutted by CpG sparse areas. CpG sites within PCR primers must be limited |

| Closed system versus opening of PCR tubes | PCR tubes always closed | Opening of PCR tubes usually necessary |

| Samples for standard curves | Necessary | Unnecessary |

| PCR bias | Specific for methylated sequence by definition | Need to minimize PCR bias between methylated and unmethylated sequences |

Some variants of real-time PCR assays do not require a genomic reference.

Originally described in 1996,20 MSP provides a sensitive method for detecting minimal levels of a methylated target in a sample; however, in its classical format it is nonquantitative and cannot distinguish between low and high levels of a methylated target sequence. By contrast, combining real-time PCR probes with MSP, as in the MethyLight assay, one can achieve a quantitative assessment of the level of DNA methylation of a targeted sequence.25,26 Real-time SYBR-GREEN MSP is another quantitative MSP method that permits direct application of primers designed for nonquantitative MSP in the real-time quantitative assay. With all MSP-related quantitative assays, there is a risk of nonspecific annealing of primers, which can completely invalidate the readout.27,28,29,30 Therefore, one should carefully design the primers and probes used for PCR amplification and should correlate methylation status with gene expression or function (such as by quantitative reverse transcription PCR or immunohistochemical evaluation of gene expression).

Methods for detecting CpG methylation after methylation-independent PCR using bisulfite-modified DNA include combined bisulfite restriction analysis,31 pyrosequencing,8,32,33,34 matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization-time of flight,9 and high performance liquid chromatography.10,35,36

CpG Methylation Detection without Bisulfite Conversion: Use of Methylation-Sensitive Restriction Enzymes

Methylation-sensitive restriction endonucleases are also routinely used to discriminate methylated and unmethylated CpG sites.37,38,39 The technical bases of combined methylation-sensitive restriction enzymes and PCR for detection of CpG methylation are illustrated in Figure 3. One advantage of restriction enzyme-based analysis over bisulfite treatment methods is that it does not require modification of DNA sequences, which makes downstream analysis relatively simple, and avoids target DNA damage. Several approaches have been developed for simultaneous analysis of CpG methylation in multiple sites of selected genes11,40 or in the whole genome.41,42,43,44 Use of restriction enzymes for methylation assessment has certain constraints. The analysis is limited by the availability of restriction sites within the fragment of interest. Another limitation is that it provides “all-or-none” readouts that do not depend on the number of accessible restriction sites within the fragment, producing identical results regardless of whether one or all sites are unmethylated. Finally, there is a possibility of incomplete digestion, which will produce false-positive results.

Figure 3.

Methylation-sensitive restriction enzymes for detection of CpG Methylation without bisulfite conversion. DNA is first treated with HhaI methylation-sensitive restriction endonuclease and then used for PCR. When the CpG locus being amplified is not methylated, HhaI cleaves its restriction site, resulting in lack of PCR amplification; whereas, if it is methylated, the HhaI restriction sites are protected from restriction enzyme digestion, allowing for PCR amplification.

Multiplex Detection Methods

A variety of microarray-based techniques have been developed that allow for simultaneous testing of multiple CpG sites in bisulfite-treated or native DNA.11,12,13,14,15,16,17 This approach is particularly important when a uniform and standardized platform is needed for analysis of multiple genes such as those panels used for diagnosis or prognosis stratification of cancer specimens. The clinical applications of microarray-based techniques have yet to be determined; however, differential methylation hybridization using restriction-enzyme based approaches has been applied for selection of hypermethylated sites in colorectal,45 ovarian,46 and breast cancers,40,47,48 and may be effective for prediction of drug response.15

Selection of Methods for Testing Methylation of Specific CpG Islands

The decision on which method(s) to use for CpG methylation clinical testing will be based on the goals of the testing and required assay performance.49 Several factors can influence the choice: 1) how many CpG sites (genes, promoters, etc) will be tested in each sample; 2) the anticipated heterogeneity of ‘normal’ and ‘abnormal’ cells within samples; and 3) the amount and quality of starting tissue, cells, or DNA material in each sample. If using archived pathology samples, fixative and embedding medium may significantly impact the method of choice.

A clear understanding of the assay goal(s) is essential for successful CpG methylation assay design. A CpG methylation assay used as a surrogate marker of gene expression must target CpG site(s) that are important for gene regulation. This information can be obtained from current databases and previously published papers, but a validation study should be performed to correlate methylation data with loss of protein expression or mRNA levels.

A number of online tools can help in primer/probe selection including MethPrimer,50 (http://www.urogene.org/methprimer, the University of California at Santa Cruz genome browser, McArdle CpG analyzer, and Methyl PrimerExpress (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). When reporting CpG sites used in an assay, it is important to indicate the template source (ie, GenBank accession number) and the coordinates of the examined DNA segment (see Weisenberger et al51 for guidelines). For bisulfite-based techniques, highlighting the location of the primer and, if pertinent, probe sequences within the bisulfite-converted sequence is recommended. For methylation-sensitive restriction enzyme-based techniques, a map of the examined region and the number of restriction sites assessed by the assay should be included.

For gene expression applications, quantitative assays are preferred when homogeneous samples are available. Since low levels of CpG methylation detected in tumor samples may not correlate directly with silencing of gene expression,21,52 quantitative methods can allow the use of cutoff-values established through a validation study with a comparison technique (eg, immunohistochemistry and quantitative reverse transcription PCR).

In contrast, CpG methylation assays that detect characteristic tumor-related genomic changes may require detection of any level of abnormal methylation as a correlative biomarker of the neoplastic process. Nonquantitative MSP may be useful for these applications, especially when quantitative levels would have little value due to variable sample composition, such as may occur with very small biopsies or cytologic specimens. Finally, genome-wide comparative analysis of CpG methylation patterns in normal tissues and tumors may require microarray approaches,53 although validation requirements for such techniques are inherently complex and not yet well-established.

Elements of Assay Reporting, Validation, and Quality Control in CpG Methylation Assays

The essential elements of a clinical report for CpG methylation testing are summarized in Table 3. In all circumstances, the assay validation and reporting requirements need to be considered in light of the goals of testing. If CpG methylation is assessed as a surrogate marker for gene silencing (or loss of function) then assays must be validated by comparing methylation status of the selected CpG(s) with observed levels of RNA or protein expression. Discordant false-negative (ie, loss of expression of an unmethylated gene) or false-positive results (ie, intact expression of a methylated gene) may be to due to unusual biology of the examined gene (eg, in cases when methylation increases expression,54,55) alternative mechanisms of gene silencing, or technical issues (eg, heterogeneity of the cellular constituents, incorrect sampling, or selection of a less informative CpG site). Alternatively, when CpG methylation data are being used as correlative biomarkers, including their use as diagnostic markers5 or as markers for the CpG island methylator phenotype (CIMP),56 correlation with gene expression is not always apparent, since a positive methylation status may not correlate with loss of gene expression examined by methods such as immunohistochemistry.

Table 3.

Reporting Recommendations for a CpG Methylation Assay

| Pre-analytic |

| Clinical indication (e.g., rule out HNPCC) |

| Tissue source (tumor, aspirate, urine cytology), including fixative, if known |

| Correlated immunohistochemical or molecular result, if for gene expression or MSI correlation |

| Analytic |

| Methods employed, including description of sensitivity and/or other controls |

| Description of gene(s) and region(s) interrogated using standardized nomenclature |

| Quantitative or qualitative result |

| Post-analytic |

| Comment if methylation at interrogated CpGs is known to correlate with gene silencing |

| Limitations on detection accuracy or sensitivity, such as sample quality or unusual sample source |

Regardless of the application, validation of qualitative clinical assays such as MSP still requires establishment of the dynamic range and analytic sensitivity of the assay. Use of parallel quantitative techniques such as MethyLight can provide such data.21,57 To establish assay precision and provide ongoing quality control, availability of well-characterized controls is essential, but these have proven difficult to standardize. Completely unmethylated fragments can be easily recovered from cloned or PCR-amplified DNA. Completely methylated fragments can be made from unmethylated DNA after treatment with SssI methylase. A heterogeneous control with a pre-determined ratio of fully methylated and fully unmethylated DNA can be made by mixing SssI-treated and untreated fragments. This control, however, cannot be considered partially methylated because each fragment is either methylated or unmethylated; currently there is no acceptable procedure to make partially methylated control samples.

The most important consideration in interpretation and reporting of CpG methylation analyses in neoplastic tissues is the heterogeneity of clinical samples. Spurious results might be explained by the scantiness of neoplastic cells or by the presence of too many non-neoplastic cells (eg, lymphocytes, fibroblasts, stromal cells, etc). This is particularly problematic for cytologic samples, where tumor cells can be severely degenerated or significantly diluted by the background of numerous inflammatory cells, benign reactive cells, and microorganisms.

Heterogeneity of the CpG methylation profiles of the neoplastic cells related to clonal evolution, differentiation state, or histological grade may also skew results. When a portion of the sample is selected for analysis, the extent of errors associated with observer-dependent tissue sampling is difficult to predict. The heterogeneity issues remain for cell-free plasma DNA as well, but they are defined by the nature of the specimen and not by observer-dependent selection of starting material. The influence of this heterogeneity on test interpretation is also unknown.

Finally, DNA sample quality issues can greatly influence assay results. Cytologic materials, which are liquid-based and obtained fresh or fixed with nonformalin fixatives, represent good quality samples, whereas formalin-fixed tissues sections can show much greater variation in DNA quality.

Applications of CpG Methylation Testing in Neoplastic Disorders

There has been increased recognition that tumor-associated epigenetic changes play an important role in the initiation and progression of human cancers. Below, we review reported applications of CpG methylation analysis in detection, classification, and monitoring treatment response of various human cancers.

Classification of Colorectal Cancer

The most common clinical application for CpG methylation testing in colorectal neoplasia is as part of the work-up of hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC/Lynch syndrome),58 which produces microsatellite instability (MSI) by germline mutation of one of several DNA mismatch repair genes. Tumors resulting from HNPCC can be distinguished from most cases of the MSI high (-H) subset of sporadic colorectal cancer by absence of CpG methylation of the MLH1 promoter, which characterizes most cases of sporadic MSI-H colorectal cancer.51,58,59,60,61,62,63,64 However, assessment of MLH1 methylation by itself is probably not adequate to distinguish between all sporadic colon cancers and HNPCC-associated MSI-H cancers, since methylation of MLH1 can been seen as a “second hit” in individuals with a germline MLH1 mutation.65 Another limitation is that there are rare cases of heritable germline MLH1 methylation (epimutation), which can be a cause of hereditary MSI-H colorectal cancer mimicking HNPCC/Lynch syndrome.66

The CpG island methylator phenotype (CIMP), defined as widespread promoter CpG island methylation, has been established as a unique epigenetic phenotype in colorectal cancer that is correlated with MLH1 methylation and MSI phenotype.51,62,67 CIMP-positive colorectal tumors have a distinct clinical, pathological, and molecular profile. Typically, they are associated with older age, proximal tumor location, female gender, poor differentiation, BRAF mutations, wild-type TP53, inactive WNT/β-catenin, stable chromosomes, and high-level LINE-1 methylation, independent of MSI status.62,67,68,69,70,71 Particularly, CIMP status may help distinguish sporadic and HNPCC-related tumors with MSI, because most sporadic MSI-H colon cancers exhibit CIMP, while this is typically not seen in HNPCC-associated cancers.59,62,72,73,74 Recent studies have suggested the existence of KRAS mutation-associated CIMP (CIMP2 or CIMP-low), separate from CIMP-negative (CIMP-0), and BRAF mutation-associated CIMP (CIMP1 or CIMP-high).75,76,77 Additional studies support a molecular difference between CIMP-low, CIMP-negative, and CIMP-high in colorectal cancer.78,79,80 A recent study suggested that all sporadic MSI-H tumors were explained by CIMP and MLH1 methylation,51 while other studies have suggested that there may be a subset of sporadic MSI-H tumors that do not exhibit MLH1 methylation and/or CIMP.62,81

Observed differences may be due to the fact that the panel of CpG markers and method of assessment for categorizing CIMP are not yet standardized. Use of quantitative MethyLight technology and evaluation of a new panel of four to eight CpG islands, including RUNX3, CACNA1G, IGF2, MLH1, NEUROG1, CRABP1, SOCS1, and CDKN2A, may be the most promising approach.51,56 Currently, it is probably best to regard CIMP as we regard the p.V600E BRAF mutation, which is also commonly seen in sporadic MSI colon cancers and is only rarely seen in HNPCC-associated tumors: the presence of either CIMP or the p.V600E mutation is strong evidence that an MSI-H tumor is sporadic, while the absence of both of these findings indicates that the tumor could be either HNPCC-associated or sporadic.

Determination of CIMP status may also be useful in evaluating the prognosis of colon cancer. A relationship of CIMP with prognosis of microsatellite stable colon cancers has been reported. While previous studies have either found no relationship or a very small relationship,60,82 one study demonstrated a poor prognosis associated with CIMP in microsatellite stable tumors, but not in MSI-H tumors.83 BRAF mutations have also been associated with poor prognosis in microsatellite stable tumors, although in the same study, no effect was seen on the good prognosis of MSI-H tumors.82 Since microsatellite stable tumors with BRAF mutations are usually very heavily methylated,75 it is possible that the relationship between prognosis and BRAF is actually a relationship between prognosis and high levels of methylation. A different CIMP panel that only detects extensive methylation may show such a relationship with prognosis. Future studies are necessary to resolve this question.

Tumor Progression in Esophageal Carcinoma

The stepwise progression to esophageal adenocarcinoma involves an initial stage of intestinal metaplasia (Barrett's esophagus), followed by low-grade and high-grade dysplasia, and finally adenocarcinoma. Shulmann et al characterized the CpG methylation status of 10 genes (HPP1, RUNX3, RIZ1, CRBP1, 3-OST-2, APC, TIMP3, P16, MGMT, P14) by real-time quantitative MSP.84 Their studies demonstrated that hypermethylation of P16, RUNX3, and HPP1 in Barrett's esophagus or low-grade dysplasia may represent independent risk factors for the progression of Barrett's esophagus to high-grade dysplasia or adenocarcinoma.

Diagnosis of Biliary and Pancreatic Malignancies on Cytologic Specimens

Due to its often cryptic location, early detection of cholangiocarcinoma is paramount in improving clinical management and patient's survival. Yang et al have shown that concurrent methylation of multiple CpG islands is a hallmark for cholangiocarcinoma.85 Using a panel of 12 tumor suppressor genes, they reported that DNA methylation profiles accurately differentiated malignant cells from reactive cells in biliary brushings.86 Similarly, Watanabe et al87 found that aberrant methylation of SFRP1 (SARP2) was seen in 79% of pancreatic carcinoma and 56% of malignant intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms, but was rarely seen in chronic pancreatitis and healthy controls. Hypermethylation of SFRP1 in pancreatic juice may be a highly sensitive and useful marker in differentiating pancreatic carcinoma from chronic pancreatitis.87

Diagnosis and Outcome Prediction in Breast Cancer

Abnormal CpG methylation in breast cancer has been found in the promoters and first exons of genes, including ESR1 (estrogen receptor α),88,89 PGR (progesterone receptor),90 FRBP3 (MDGI, mammary-derived growth inhibitor),91 CALCA (calcitonin),92 MUC1, 93 and known proto-oconcogene HRAS, 94 and tumor suppressor CDKN2A95 genes. The first systematic screen to detect all abnormally methylated genes used a differential methylation hybridization approach11 and identified multiple methylated fragments in cultured tumor cells and in breast cancer tumors,12 including transcribed domains of ribosomal DNA.96

Detection of abnormal CpG methylation specific for breast cancer can be done using fine needle aspirates,97 nipple aspirate fluid,98 and ductal lavage,99 as reviewed by Dua et al.100 MSP was reported to have high analytical specificity and moderate analytical sensitivity (100% and 67%, respectively) for diagnosis of malignancy when three genes (RARB, RASSF1, and CCND2) were analyzed in fine needle aspirate samples.101 Fackler et al102 evaluated methylation profiles of nine CpG islands in ductal lavages from 37 cancer patients undergoing mastectomy. A cumulative methylation index had an analytical sensitivity of 71% and specificity of 83% in the detection of cancer cells, compared with an analytical sensitivity of 33% and specificity of 99% by cytomorphology alone. This study provides proof-of-principle by showing the advantages of using methylation analyses to query cytologic specimens and indicates its potential use in diagnosis and risk stratification.102

Other studies have found methylation of the CDH1 gene to be associated with breast tumor invasion and lymph node infiltration,103,104 and methylation of LATS1 and LATS2 has been associated with aggressive cancer.105 Nevertheless, currently, there are insufficient data to determine the clinical usefulness of methylation tests for diagnosis and prognosis of breast cancer so additional studies are warranted.

Progression in Cervical Carcinoma

The progression from precursor squamous intraepithelial lesions to cervical carcinoma requires additional genetic and epigenetic alterations that have not been characterized fully. Gustafson et al examined aberrant promoter methylation of 15 tumor suppressor genes using a multiplex, nested-MSP approach in 11 high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions, 17 low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions, and 11 negative tissues from liquid-based cervical cytology samples.106 Aberrant promoter methylation of DAPK1 and CADM1 (IGSF4) occurred at a high frequency in high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions and was absent in low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions and negative samples. Also, the mean number of methylated genes was significantly higher in high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions, as compared with low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions and negative samples.106 Aberrant CDKN2A (p16) methylation was significantly higher in invasive cervical cancers (61%) as compared with high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (20%) or normal cytologic specimens (7.5%).107 DNA methylation profiling will likely add a new dimension in the application of molecular biomarkers for prediction of disease progression and risk assessment in cervical squamous lesions, but again others studies are warranted.

Diagnosis of Urothelial Carcinoma in Urine Cytology

Urine cytology is the initial method used for screening of bladder urothelial carcinoma. Although high-grade urothelial carcinoma can be readily detected in urine cytology, cytologic detection of low-grade papillary urothelial carcinoma in urine is challenging due to the overlapping cytomorphologic features with benign reactive processes. Wang et al,108 using a panel of nine CpG islands, found that concurrent methylation of three or more CpG islands can differentiate low-grade papillary urothelial carcinoma lesions from benign/reactive urothelium in urine. The analytical sensitivity to detect low-grade urothelial carcinoma by DNA methylation profiling was 80% in comparison with 13% by cytology alone.108 These studies demonstrate that analysis of methylation profiling in certain cytologic specimens can be a useful ancillary tool in facilitating early and accurate detection of urothelial cancer cells.

Predicting Response to Chemotherapy: MGMT Profiling in Glioblastoma and Lymphoma

MGMT is a DNA repair enzyme that is frequently methylated in human cancers, including glioblastoma and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. MGMT functions to repair O6-methylguanine DNA adducts generated by both endogenous and exogenous exposure to alkylating agents.109,110,111 Repair of O6-methylguanine is critical to prevent accumulation of G>A transition mutations in important growth regulatory genes, including KRAS and TP53.112 CpG islands within the promoter and coding region of MGMT are aberrantly hyper- or hypomethylated, respectively, resulting in transcriptional repression.79,113,114,115,116,117 Loss of MGMT expression and/or MGMT promoter methylation are associated with a worse prognosis in several tumor types,118,119,120 possibly due to an increased mutation rate.

Since unrepaired O6-methylguanine signals apoptosis,121 low MGMT expression would be expected to predict an improved clinical response to chemotherapeutic alkylating agents. Thus, MGMT promoter methylation status can impact the degree of signaling for apoptosis following alkylating agent therapy. In glioblastoma multiforme, loss of MGMT expression predicts greater efficacy of treatment with temozolimide and other alkylating agents. Several studies have shown a compelling direct correlation between MGMT promoter methylation and drug response that translates into increased overall patient survival.122,123,124,125 Consequently, MGMT promoter methylation analysis using MSP is being used in the clinical laboratory to predict outcome and response to therapy in glioblastoma. MGMT promoter methylation also predicts improved outcome in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with the alkylating agent cyclophosphamide.126 In addition to predicting drug response, MGMT promoter methylation is an independent predictor of better outcome in glioblastoma and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.124,127

CpG Methylation Profiling of Free DNA in Body Fluids as a Screening Tool

Tumor cells that are undergoing necrosis or apoptosis release fragments of genomic DNA, which may enter the circulation or be released in the urine or stool where they can be used as biomarkers for the diagnosis, staging, or post-treatment monitoring of cancer. There is tremendous variability in the amount and half-life of cell-free DNA released into the circulation128,129; however, the ease of obtaining serial serum or plasma has stimulated tremendous interest in the potential utility of detecting tumor-associated methylated DNA in such samples.

Several studies have addressed whether CpG methylation of tumor biomarkers in serum cell-free DNA is in fact correlated with tumor status. Bastian et al evaluated circulating serum cell-free DNA CpG methylation of GSTP1, which is hypermethylated in prostate cancer.130 They found that circulating cell-free DNA with GSTP1 hypermethylation was not detected in the serum of men with a negative prostate biopsy but was detected in 12% with clinically localized disease and in 28% with metastatic cancer. Detection of hypermethylated GTSP1 DNA in serum was the most significant predictor of increased prostate specific antigen levels.130

Using MethyLight MSP, Muller et al analyzed 215 serum samples from patients with cervical or breast cancer to identify multigene associated CpG methylation changes. In cervical cancer, hypermethylation of three genes (MYOD1, CDH1, and CDH13) in pretreatment sera was significantly associated with a poor disease outcome.131 Methylation of a similar set of genes (RASSF1, ESR1, APC, HSD17B4, and HIC1) selected from a panel of 39 genes in serum was found to be informative for prediction of metastasis, with APC and RASSF1 being the most important.132

Koyanagi et al studied the association between DNA methylation of RASSF1 and RARB in circulating tumor cells in peripheral blood of melanoma patients with response to biochemotherapy (a treatment modality that includes biological agents such as interferon and interleukin-2).133 Patients with methylated RASSF1 and RARB showed a significantly poorer response to biochemotherapy, shorter time to progression, and lower overall survival.133

Grady et al studied CpG methylation of MLH1 promoter DNA in the serum of patients with microsatellite unstable colon cancers.134 In a panel of sera from 19 colon cancer cases, methylation of MLH1 was detected in sera in three out of nine patients whose primary tumors harbored MLH1 methylation. The assay proved 33% analytically sensitive and 100% specific.134

Detection of hypermethylated DNA in stool samples has been proposed as a screening tool for colorectal cancer.135,136 Lenhard et al analyzed promoter methylation of HIC1 in stools of patients with colorectal cancer or adenomas.136 They found that 97% of samples had amplifiable DNA and HIC1 was methylated in 42% of colorectal cancer patients and 31% of patients with adenomas, and was not methylated in normal samples. Belshaw et al135 compared methylation of a panel of CpG islands using MSP and combined bisulfite restriction analysis and found similar methylation frequencies of ESR1 and MGMT between tumor tissue samples and fecal DNA from the same patients.

The above reported data identify potential clinical applications of CpG methylation testing; however, future prospective studies are required to validate these findings and to refine guidelines for clinical practice.

Monitoring Treatment Response to Demethylating Agents

One of the most promising clinical applications for CpG methylation analysis is in monitoring the response to demethylating agents. 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine/decitabine (Dacogen) and azacitidine (Vidaza) are agents approved by the U. S. Food and Drug Administration for treatment of myelodysplastic syndrome. They function by reversing hypermethylation of tumor suppressors, including the cell cycle regulator p15. Demethylating agents also have variable activity in a wide variety of other tumor types, especially in combination with other agents.

Several clinical studies have now used CpG methylation profiling of pre- and post-treatment blood samples to monitor the therapeutic effects of demethylating agents. The effects of these drugs on both global methylation (eg, LINE repeats) and the CpG methylation of specific target genes have been studied. In a phase I/II study of decitabine in acute myelogenous leukemia/myelodysplastic syndrome, transient and reversible decreases in the level of DNA methylation at LINE and CDKN2B (p15) promoter were observed by a quantitative pyrosequencing assay over a 10-day course of treatment.137 Transcriptional up-regulation of CDKN2B (p15) was observed in parallel with decreases in CpG methylation. Lower pretreatment levels of CDKN2B (p15) promoter methylation were correlated with clinical responses to decitabine. Changes in the levels of CpG methylation following treatment were modest (shifts of 10% to 20%) strongly indicating the need for reproducible quantitative assays for monitoring methylation levels.137 As discussed above, such techniques include real-time PCR (eg, MethyLight) and pyrosequencing methodologies.138

Given the current wide use of demethylating agents in myelodysplastic syndrome and myeloid leukemias, CDKN2B (p15) methylation assays have the potential to be used up-front to predict which patients will respond to demethylation therapies. However, given the ability to monitor response in these tumors based solely on blood counts, empirical use of demethylating agents in the absence of pretreatment testing may well continue. If demethylating therapy becomes common in solid tumors where treatment response is more difficult to assess, blood monitoring of re-expression of blood proteins, such as fetal hemoglobin due to CpG demethylation, may serve as a useful surrogate marker of drug response.139

CpG Methylation and Inflammatory and Infectious Diseases Related to Cancer Development

Viruses and CpG Methylation

Some viruses appear to use methylation to regulate expression of their own viral genes as well as host cellular genes. Diseased tissues that harbor viruses might, therefore, be responsive to therapies that alter methylation patterns.140,141,142,143 For example, Epstein-Barr virus, which is associated with selected histological subtypes of lymphomas and carcinomas, may repress certain viral genes (nuclear antigens EBNA 1-6, and latent membrane proteins LMP 1 and 2) in an effort to elude immune destruction.144,145 In other examples, hepatocellular carcinomas appear to silence certain tumor suppressor genes in the presence of heptatitis B virus infection,146 and HPV appears to use methylation to exert its effects on viral and cellular gene expression.147 JC virus T antigen expression is also associated with widespread CpG methylation referred to as CIMP in colorectal cancer.148 Dysregulation of DNA methyltranferases may be responsible, at least in part, for the effects of viruses on host gene promoter methylation.146,149 The first protein ever shown to bind to and activate a methylated promoter was a virally encoded factor, demonstrating that viruses have evolved mechanisms to overcome methylation to their selective advantage.150 To the extent that host cellular methylation patterns are altered in virus-specific ways, it may be possible to use expression patterns or methylation patterns to identify virus-related subclasses of cancers. Furthermore, a promising novel targeted therapeutic strategy involves demethylation/activation of viral gene expression in a way that triggers immune recognition and destruction of virally infected tumor cells with little adverse effect on uninfected normal cells.

Bacterial Infection and CpG Methylation

In contrast to CpG methylation in tumors, the CpG methylation status of genes in non-neoplastic tissues has received little attention.151 However, several studies have shown that CpG island hypermethylation of genes known to be methylated in cancers can be detected in the non-neoplastic tissues.152,153,154 One of the most remarkable examples of methylation in non-neoplastic tissue is the hypermethylation of multiple CpG islands in the mucosal tissues of patients with inflammatory conditions, such as chronic gastritis associated with Helicobacter pylori infection and inflammatory bowel diseases (ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease), conditions with increased risk of cancer development.

Increased CpG methylation of several genes has been identified in the gastric mucosa of patients with H. pylori gastritis, reviewed by Gologan et al.151 Chan et al155 demonstrated that CDH1 (E-cadherin) methylation was more frequent in the gastric mucosa of patients with H. pylori infection as compared with those without. Another study,154 where the methylation status of several genes was examined, reported that CpG methylation was up to 303-fold higher in H. pylori-positive than in H. pylori-negative gastric mucosal tissue. MLH1 CpG methylation in gastric epithelial cells associated with reduced RNA and protein levels of MLH1 were reported after exposure of gastric cells to H. pylori organisms.156 Studies to-date have not provided conclusive evidence regarding the potential role of CpG methylation in inflammatory cells present in the gastric mucosa of H. pylori gastritis.

The potential implications of these reported findings are two-fold: first, CpG methylation may become useful in clinical practice to determine the risk of gastric cancer, and second, demethylating agents by restoring the CpG methylation levels in the gastric mucosa may become useful in cancer chemoprevention. Prospective studies for these potential applications of CpG methylation associated with H. pylori gastritis and other inflammatory diseases are warranted.

Summary

There are numerous promising clinical applications of CpG methylation testing for tumors and preneoplastic lesions. However, if CpG methylation testing is to become routine in clinical molecular diagnostics, there is a critical need for cross-laboratory comparisons of different methodologies, for the development of standardized quality control materials for assays and for the adoption of standard reporting formats. While significant advances have been made in the analysis of methylation patterns in various clinical tissues and other samples, with the exception of MGMT in gliomas, the selection of optimal gene targets for prognostic methylation panels in specific tumor types remains to be established. Genome-wide methylation screens are currently identifying new marker gene panels for prognosis and therapy-response predictors in other tumors. Application of such techniques in carefully controlled clinical trials, where favorable numbers of samples can be compared with patient outcomes data, is an essential component for the development of clinically meaningful targets for CpG methylation analysis. Comparative studies are clearly essential to further advancement of this field, therefore, we urge researchers to identify and define the CpG sites analyzed in published reports by listing DNA sequences and/or describing the location of the tested CpG(s) in relation to the transcriptional start site. Such advances will be instrumental in attaining clinically valuable and reliable CpG methylation assays for molecular diagnosis for the years to come.

Footnotes

The Methylation Working Group is a subcommittee of the AMP Clinical Practice Committee. The 2006–2008 AMP Clinical Practice Committee consisted of Aaron Bossler, Deborah Dillon, Michelle Dolan, William Funkhouser, Julie Gastier-Foster, Dan Jones, Elaine Lyon (Chair 2005–2006), Victoria M. Pratt (Chair 2007–2008), Daniel Sabath, Antonia R. Sepulveda, Kathleen Stellrecht, and Daynna A. Wolff.

Standard of practice is not being defined by this article, and there may be alternatives.

Address reprint requests to Association for Molecular Pathology (AMP), 9650 Rockville Pike, Bethesda, MD 20814, E-mail: amo@asip.org.

References

- 1.Gardiner-Garden M, Frommer M. CpG islands in vertebrate genomes. J Mol Biol. 1987;196:261–282. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(87)90689-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Takai D, Jones PA. Comprehensive analysis of CpG islands in human chromosomes 21 and 22. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:3740–3745. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052410099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ehrich M, Nelson M, Stanssens P, Zabeau M, Liloglou T, Xinarianos G, Cantor C, Field J, van den Boom D. Quantitative high-throughput analysis of DNA methylation patterns by base-specific cleavage and mass spectrometry. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:15785–15790. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507816102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Avramis V, Mecum R, Nyce J, Steele D, Holcenberg J. Pharmacodynamic and DNA methylation studies of high-dose 1-beta-d-arabinofuranosyl cytosine before and after in vivo 5-azacytidine treatment in pediatric patients with refractory acute lymphocytic leukemia. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1989;24:203–210. doi: 10.1007/BF00257619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoque MO, Feng Q, Toure P, Dem A, Critchlow CW, Hawes SE, Wood T, Jeronimo C, Rosenbaum E, Stern J, Yu M, Trink B, Kiviat NB, Sidransky D. Detection of aberrant methylation of four genes in plasma DNA for the detection of breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4262–4269. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.3516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leung WK, To KF, Man EP, Chan MW, Bai AH, Hui AJ, Chan FK, Sung JJ. Quantitative detection of promoter hypermethylation in multiple genes in the serum of patients with colorectal cancer. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:2274–2279. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.50412.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frommer M, McDonald LE, Millar DS, Collis CM, Watt F, Grigg GW, Molloy PL, Paul CL. A genomic sequencing protocol that yields a positive display of 5-methylcytosine residues in individual DNA strands. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:1827–1831. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.5.1827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mikeska T, Bock C, El-Maarri O, Hubner A, Ehrentraut D, Schramm J, Felsberg J, Kahl P, Buttner R, Pietsch T, Waha A. Optimization of quantitative MGMT promoter methylation analysis using pyrosequencing and combined bisulfite restriction analysis. J Mol Diagn. 2007;9:368–381. doi: 10.2353/jmoldx.2007.060167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schatz P, Dietrich D, Schuster M. Rapid analysis of CpG methylation patterns using RNase T1 cleavage and MALDI-TOF. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:e167. doi: 10.1093/nar/gnh165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matin MM, Baumer A, Hornby DP. An analytical method for the detection of methylation differences at specific chromosomal loci using primer extension and ion pair reverse phase HPLC. Hum Mutat. 2002;20:305–311. doi: 10.1002/humu.10118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang TH, Perry MR, Laux DE. Methylation profiling of CpG islands in human breast cancer cells. Hum Mol Genet. 1999;8:459–470. doi: 10.1093/hmg/8.3.459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yan PS, Perry MR, Laux DE, Asare AL, Caldwell CW, Huang TH. CpG island arrays: an application toward deciphering epigenetic signatures of breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:1432–1438. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yan P, Efferth T, Chen H, Lin J, Rodel F, Fuzesi L, Huang T. Use of CpG island microarrays to identify colorectal tumors with a high degree of concurrent methylation. Methods. 2002;27:162–169. doi: 10.1016/s1046-2023(02)00070-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bibikova M, Lin Z, Zhou L, Chudin E, Garcia E, Wu B, Doucet D, Thomas N, Wang Y, Vollmer E, Goldmann T, Seifart C, Jiang W, Barker D, Chee M, Floros J, Fan J. High-throughput DNA methylation profiling using universal bead arrays. Genome Res. 2006;16:383–393. doi: 10.1101/gr.4410706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cheng YW, Shawber C, Notterman D, Paty P, Barany F. Multiplexed profiling of candidate genes for CpG island methylation status using a flexible PCR/LDR/Universal Array assay. Genome Res. 2006;16:282–289. doi: 10.1101/gr.4181406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fukasawa M, Kimura M, Moritas S, Matsubara K, Yamanaka S, Endo C, Sakurada A, Sato M, Kondo T, Horii A, Sasaki H, Hatada I. Microarray analysis of promoter methylation in lung cancers. J Hum Genet. 2006;51:368–374. doi: 10.1007/s10038-005-0355-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schumacher A, Kapranov P, Kaminsky Z, Flanagan J, Assadzadeh A, Yau P, Virtanen C, Winegarden N, Cheng J, Gingeras T, Petronis A. Microarray-based DNA methylation profiling: technology and applications. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:528–542. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grunau C, Clark SJ, Rosenthal A. Bisulfite genomic sequencing: systematic investigation of critical experimental parameters. Nucleic Acid Research. 2001;29:E65. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.13.e65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Warnecke PM, Stirzaker C, Melki JR, Millar DS, Paul CL, Clark SJ. Detection and measurement of PCR bias in quantitative methylation analysis of bisulphite-treated DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:4422–4426. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.21.4422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Herman JG, Graff JR, Myohanen S, Nelkin BD, Baylin SB. Methylation-specific PCR: a novel PCR assay for methylation status of CpG islands. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:9821–9826. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.18.9821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ogino S, Kawasaki T, Brahmandam M, Cantor M, Kirkner GJ, Spiegelman D, Makrigiorgos GM, Weisenberger DJ, Laird PW, Loda M, Fuchs CS. Precision and performance characteristics of bisulfite conversion and real-time PCR (MethyLight) for quantitative DNA methylation analysis. J Mol Diagn. 2006;8:209–217. doi: 10.2353/jmoldx.2006.050135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang Y, Zheng W, Luo J, Zhang D, Zuhong L. In situ bisulfite modification of membrane-immobilized DNA for multiple methylation analysis. Anal Biochem. 2006;359:183–188. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2006.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kerjean A, Vieillefond A, Thiounn N, Sibony M, Jeanpierre M, Jouannet P. Bisulfite genomic sequencing of microdissected cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:E106. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.21.e106. E106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Laird PW. The power and the promise of DNA methylation markers. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:253–266. doi: 10.1038/nrc1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eads CA, Danenberg KD, Kawakami K, Saltz LB, Blake C, Shibata D, Danenberg PV, Laird PW. MethyLight: a high-throughput assay to measure DNA methylation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:E32. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.8.e32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eads CA, Danenberg KD, Kawakami K, Saltz LB, Danenberg PV, Laird PW. CpG island hypermethylation in human colorectal tumors is not associated with DNA methyltransferase overexpression. Cancer Res. 1999;59:2302–2306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Akey DT, Akey JM, Zhang K, Jin L. Assaying DNA methylation based on high-throughput melting curve approaches. Genomics. 2002;80:376–384. doi: 10.1006/geno.2002.6851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thomassin H, Kress C, Grange T. MethylQuant: a sensitive method for quantifying methylation of specific cytosines within the genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:e168. doi: 10.1093/nar/gnh166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zeschnigk M, Bohringer S, Price EA, Onadim Z, Masshofer L, Lohmann DR. A novel real-time PCR assay for quantitative analysis of methylated alleles (QAMA): analysis of the retinoblastoma locus. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:e125. doi: 10.1093/nar/gnh122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cottrell SE, Distler J, Goodman NS, Mooney SH, Kluth A, Olek A, Schwope I, Tetzner R, Ziebarth H, Berlin K. A real-time PCR assay for DNA-methylation using methylation-specific blockers. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:e10. doi: 10.1093/nar/gnh008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xiong Z, Laird PW. COBRA: a sensitive and quantitative DNA methylation assay. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:2532–2534. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.12.2532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Colella S, Shen L, Baggerly KA, Issa JP, Krahe R. Sensitive and quantitative universal pyrosequencing methylation analysis of CpG sites. Biotechniques. 2003;35:146–150. doi: 10.2144/03351md01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Uhlmann K, Brinckmann A, Toliat MR, Ritter H, Nurnberg P. Evaluation of a potential epigenetic biomarker by quantitative methyl-single nucleotide polymorphism analysis. Electrophoresis. 2002;23:4072–4079. doi: 10.1002/elps.200290023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tost J, Dunker J, Gut IG. Analysis and quantification of multiple methylation variable positions in CpG islands by pyrosequencing. Biotechniques. 2003;35:152–156. doi: 10.2144/03351md02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.EL-Maarri O, Herbibiaux U, Walter J, Oldenburg J. A rapid, quantitative, non-radioactive bisulfite-SNuPE-IP RP HPLC assay for methylation analysis at specific CpG sites. Nucleic Acids Research. 2002;30:E25. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.6.e25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Deng D, Deng G, Smith MF, Zhou J, Xin H, Powell SM, Lu Y. Simultaneous detection of CpG methylation and single nucleotide polymorphism by denaturing high performance liquid chromatography. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:E13. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.3.e13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Waalwijk C, Flavell RA. DNA methylation at a CCGG sequence in the large intron of the rabbit beta-globin gene: tissue-specific variations. Nucleic Acids Res. 1978;5:4631–4634. doi: 10.1093/nar/5.12.4631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shen CK, Maniatis T. Tissue-specific DNA methylation in a cluster of rabbit beta-like globin genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1980;77:6634–6638. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.11.6634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Singer-Sam J, Grant M, LeBon JM, Okuyama K, Chapman V, Monk M, Riggs AD. Use of a HpaII-polymerase chain reaction assay to study DNA methylation in the Pgk-1 CpG island of mouse embryos at the time of X-chromosome inactivation. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:4987–4989. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.9.4987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Melnikov AA, Scholtens DM, Wiley EL, Khan SA, Levenson VV. Array-based multiplex analysis of DNA methylation in breast cancer tissues. J Mol Diagn. 2008;10:93–101. doi: 10.2353/jmoldx.2008.070077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hayashizaki Y, Hirotsune S, Okazaki Y, Hatada I, Shibata H, Kawai J, Hirose K, Watanabe S, Fushiki S, Wada S, Sugimoto T, Kobayakawa K, Kawara T, Katsuki M, Shibuya T, Mukai T. Restriction landmark genomic scanning method and its various applications. Electrophoresis. 1993;14:251–258. doi: 10.1002/elps.1150140145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Plass C, Shibata H, Kalcheva I, Mullins L, Kotelevtseva N, Mullins J, Kato R, Sasaki H, Hirotsune S, Okazaki Y, Held WA, Hayashizaki Y, Chapman VM. Identification of Grf1 on mouse chromosome 9 as an imprinted gene by RLGS-M. Nat Genet. 1996;14:106–109. doi: 10.1038/ng0996-106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Toyota M, Ho C, Ahuja N, Jair KW, Li Q, Ohe-Toyota M, Baylin SB, Issa JP. Identification of differentially methylated sequences in colorectal cancer by methylated CpG island amplification. Cancer Res. 1999;59:2307–2312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gonzalgo ML, Liang G, Spruck CH, 3rd, Zingg JM, Rideout WM, 3rd, Jones PA. Identification and characterization of differentially methylated regions of genomic DNA by methylation-sensitive arbitrarily primed PCR. Cancer Res. 1997;57:594–599. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Estecio MR, Yan PS, Ibrahim AE, Tellez CS, Shen L, Huang TH, Issa JP. High-throughput methylation profiling by MCA coupled to CpG island microarray. Genome Res. 2007;17:1529–1536. doi: 10.1101/gr.6417007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wei SH, Balch C, Paik HH, Kim YS, Baldwin RL, Liyanarachchi S, Li L, Wang Z, Wan JC, Davuluri RV, Karlan BY, Gifford G, Brown R, Kim S, Huang TH, Nephew KP. Prognostic DNA methylation biomarkers in ovarian cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:2788–2794. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen CM, Chen HL, Hsiau TH, Hsiau AH, Shi H, Brock GJ, Wei SH, Caldwell CW, Yan PS, Huang TH. Methylation target array for rapid analysis of CpG island hypermethylation in multiple tissue genomes. Am J Pathol. 2003;163:37–45. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63628-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Melnikov AA, Gartenhaus RB, Levenson AS, Motchoulskaia NA, Levenson Chernokhvostov VV. MSRE-PCR for analysis of gene-specific DNA methylation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:e93. doi: 10.1093/nar/gni092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kagan J, Srivastava S, Barker P, A. S., Belinsky S, Cairns P. Towards clinical application of methylated DNA sequences as cancer biomarkers: a Joint NCI's EDRN and NIST workshop on standards, methods, assays, reagents, and tools. Cancer Res. 2007;67:4545–4549. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li L, Dahiya R. MethPrimer: designing primers for methylation PCRs. Bioinformatics. 2002;18:1427–1431. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/18.11.1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Weisenberger DJ, Siegmund KD, Campan M, Young J, Long TI, Faasse MA, Kang GH, Widschwendter M, Weener D, Buchanan D, Koh H, Simms L, Barker M, Leggett B, Levine J, Kim M, French AJ, Thibodeau SN, Jass J, Haile R, Laird PW. CpG island methylator phenotype underlies sporadic microsatellite instability and is tightly associated with BRAF mutation in colorectal cancer. Nat Genet. 2006;38:787–793. doi: 10.1038/ng1834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Toyooka KO, Toyooka S, Maitra A, Feng Q, Kiviat NC, Smith A, Minna JD, Ashfaq R, Gazdar AF. Establishment and validation of real-time polymerase chain reaction method for CDH1 promoter methylation. Am J Pathol. 2002;161:629–634. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64218-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Brena RM, Morrison C, Liyanarachchi S, Jarjoura D, Davuluri RV, Otterson GA, Reisman D, Glaros S, Rush LJ, Plass C. Aberrant DNA methylation of OLIG1, a novel prognostic factor in non-small cell lung cancer. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e108. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kominato Y, Hata Y, Takizawa H, Tsuchiya T, Tsukada J, Yamamoto F. Expression of human histo-blood group ABO genes is dependent upon DNA methylation of the promoter region. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:37240–37250. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.52.37240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kelavkar UP, Harya NS, Hutzley J, Bacich DJ, Monzon FA, Chandran U, Dhir R, O'Keefe DS. DNA methylation paradigm shift: 15-lipoxygenase-1 upregulation in prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia and prostate cancer by atypical promoter hypermethylation. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2007;82:185–197. doi: 10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2006.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ogino S, kawasaki T, Kirkner GJ, Kraft P, Loda M, Fuchs CS. Evaluation of markers for CpG island methylator phenotype (CIMP) in colorectal cancer by a large population-based sample. J Mol Diagn. 2007;9:305–314. doi: 10.2353/jmoldx.2007.060170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Coleman WB, Rivenbark AG. Quantitative DNA methylation analysis: the promise of high-throughput epigenomic diagnostic testing in human neoplastic disease. J Mol Diagn. 2006;8:152–156. doi: 10.2353/jmoldx.2006.060026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Samowitz W. The CpG island methylator phenotype in colorectal cancer. J Mol Diagn. 2007;9:281–283. doi: 10.2353/jmoldx.2007.070031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Toyota M, Ahuja N, Ohe-Toyota M, Herman JG, Baylin SB, Issa JP. CpG island methylator phenotype in colorectal cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:8681–8686. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.15.8681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hawkins N, Norrie M, Cheong K, Mokany E, Ku SL, Meagher A, O'Connor T, Ward R. CpG island methylation in sporadic colorectal cancers and its relationship to microsatellite instability. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:1376–1387. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.32997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Whitehall VL, Wynter CV, Walsh MD, Simms LA, Purdie D, Pandeya N, Young J, Meltzer SJ, Leggett BA, Jass JR. Morphological and molecular heterogeneity within nonmicrosatellite instability-high colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 2002;62:6011–6014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Samowitz WS, Albertsen H, Herrick J, Levin TR, Sweeney C, Murtaugh MA, Wolff RK, Slattery ML. Evaluation of a large, population-based sample supports a CpG island methylator phenotype in colon cancer. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:837–845. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Grady WM. CIMP and colon cancer gets more complicated. Gut. 2007;56:1498–1500. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.125732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Teodoridis JM, Hardie C, Brown R. CpG island methylator phenotype (CIMP) in cancer: causes and implications. Cancer Lett. 2008;268:177–186. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Deng G, Bell I, Crawley S, Gum J, Terdiman JP, Allen BA, Truta B, Sleisenger MH, Kim YS. BRAF mutation is frequently present in sporadic colorectal cancer with methylated hMLH1, but not in hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:191–195. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-1118-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hitchins MP, Wong JJ, Suthers G, Suter CM, Martin DI, Hawkins NJ, Ward RL. Inheritance of a cancer-associated MLH1 germ-line epimutation. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:697–705. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa064522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ogino S, Cantor M, Kawasaki T, Brahmandam M, Kirkner G, Weisenberger DJ, Campan M, Laird PW, Loda M, Fuchs CS. CpG island methylator phenotype (CIMP) of colorectal cancer is best characterized by quantitative DNA methylation analysis and prospective cohort studies. Gut. 2006;55:1000–1006. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.082933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Goel A, Nagasaka T, Arnold CN, Inoue T, Hamilton C, Niedzwiecki D, Compton C, Mayer RJ, Goldberg R, Bertagnolli MM, Boland CR. The CpG island methylator phenotype and chromosomal instability are inversely correlated in sporadic colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:127–138. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Samowitz WS, Slattery ML, Sweeney C, Herrick J, Wolff RK, Albertsen H. APC mutations and other genetic and epigenetic changes in colon cancer. Mol Cancer Res. 2007;5:165–170. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-06-0398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kawasaki T, Nosho K, Ohnishi M, Suemoto Y, Kirkner GJ, Meyerhardt JA, Fuchs CS, Ogino S. Correlation of beta-catenin localization with cyclooxygenase-2 expression and CpG island methylator phenotype (CIMP) in colorectal cancer. Neoplasia. 2007;9:569–577. doi: 10.1593/neo.07334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ogino S, Kawasaki T, Nosho K, Ohnishi M, Suemoto Y, Kirkner GJ, Fuchs CS. LINE-1 hypomethylation is inversely associated with microsatellite instability and CpG methylator phenotype in colorectal cancer. Int J Cancer. 2008;122:2767–2773. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Toyota M, Issa JP. The role of DNA hypermethylation in human neoplasia. Electrophoresis. 2000;21:329–333. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1522-2683(20000101)21:2<329::AID-ELPS329>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kambara T, Simms LA, Whitehall VL, Spring KJ, Wynter CV, Walsh MD, Barker MA, Arnold S, McGivern A, Matsubara N, Tanaka N, Higuchi T, Young J, Jass JR, Leggett BA. BRAF mutation is associated with DNA methylation in serrated polyps and cancers of the colorectum. Gut. 2004;53:1137–1144. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.037671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.McGivern A, Wynter CV, Whitehall VL, Kambara T, Spring KJ, Walsh MD, Barker MA, Arnold S, Simms LA, Leggett BA, Young J, Jass JR. Promoter hypermethylation frequency and BRAF mutations distinguish hereditary non-polyposis colon cancer from sporadic MSI-H colon cancer. Fam Cancer. 2004;3:101–107. doi: 10.1023/B:FAME.0000039861.30651.c8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ogino S, Kawasaki T, Kirkner GJ, Loda M, Fuchs CS. CpG island methylator phenotype-low (CIMP-low) in colorectal cancer: possible associations with male sex and KRAS mutations. J Mol Diagn. 2006;8:582–588. doi: 10.2353/jmoldx.2006.060082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Shen L, Toyota M, Kondo Y, Lin E, Zhang L, Guo Y, Hernandez NS, Chen X, Ahmed S, Konishi K, Hamilton SR, Issa JP. Integrated genetic and epigenetic analysis identifies three different subclasses of colon cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:18654–18659. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704652104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ogino S, Goel A. Molecular classification and correlates in colorectal cancer. J Mol Diagn. 2008;10:13–27. doi: 10.2353/jmoldx.2008.070082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ogino S, Kawasaki T, Kirkner GJ, Ohnishi M, Fuchs CS. 18q loss of heterozygosity in microsatellite stable colorectal cancer is correlated with CpG island methylator phenotype-negative (CIMP-0) and inversely with CIMP-low and CIMP-high. BMC Cancer. 2007;7:72. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-7-72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ogino S, Kawasaki T, Kirkner GJ, Suemoto Y, Meyerhardt JA, Fuchs CS. Molecular correlates with MGMT promoter methylation and silencing support CpG island methylator phenotype-low (CIMP-low) in colorectal cancer. Gut. 2007;56:1564–1571. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.119750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kawasaki T, Ohnishi M, Nosho K, Suemoto Y, Kirkner GJ, Meyerhardt JA, Fuchs CS, Ogino S. CpG island methylator phenotype-low (CIMP-low) colorectal cancer shows not only fewer methylated CIMP-high-specific CpG island, but also low-level methylation in individual loci. Mod Pathol. 2008;21:245–255. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Oliveira C, Westra JL, Arango D, Ollikainen M, Domingo E, Ferreira A, Velho S, Niessen R, Lagerstedt K, Alhopuro P, Laiho P, Veiga I, Teixeira MR, Ligtenberg M, Kleibeuker JH, Sijmons RH, Plukker JT, Imai K, Lage P, Hamelin R, Albuquerque C, Schwartz S, Jr, Lindblom A, Peltomaki P, Yamamoto H, Aaltonen LA, Seruca R, Hofstra RM. Distinct patterns of KRAS mutations in colorectal carcinomas according to germline mismatch repair defects and hMLH1 methylation status. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13:2303–2311. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Samowitz W, Sweeney C, Herrick J, Albertsen H, Levin T, Murtaugh M, Wolff R, Slattery M. Poor survival associated with the BRAF V600E mutation in microsatellite-stable colon cancers. Cancer Res. 2005;65:6063–6069. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ward RL, Cheong K, Ku SL, Meagher A, O'Connor T, Hawkins NJ. Adverse prognostic effect of methylation in colorectal cancer is reversed by microsatellite instability. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:3729–3736. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.03.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Schulmann K, Sterian A, Berki A, Yin J, Sato F, Xu Y, Olaru A, Wang S, Mori Y, Deacu E, Hamilton J, Kan T, Krasna MJ, Beer DG, Pepe MS, Abraham JM, Feng Z, Schmiegel W, Greenwald BD, Meltzer SJ. Inactivation of p16. RUNX3, and HPP1 occurs early in Barrett's-associated neoplastic progression and predicts progression risk. Oncogene. 2005;24:4138–4148. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Yang B, Guo M, Herman J, Clark D. Aberrant promoter methylation profiles of tumor suppressor genes in hepatocellular carcinoma. Am J Pathol. 2003;163:1101–1107. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63469-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Yang B, House M, Guo M, Herman J, Clark D. Promoter methylation profiles of tumor suppressor genes in intrahepatic and extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Mod Pathol. 2005;18:412–420. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Watanabe H, Okada G, Ohtsubo K, Yao F, Jiang P, Mouri H, Wakabayashi T, Sawabu N. Aberrant methylation of secreted apoptosis-related protein 2 (SARP2) in pure pancreatic juice in diagnosis of pancreatic neoplasms. Pancreas. 2006;32:382–389. doi: 10.1097/01.mpa.0000221617.89376.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Falette NS, Fuqua SA, Chamness GC, Cheah MS, Greene GL, McGuire WL. Estrogen receptor gene methylation in human breast tumors. Cancer Res. 1990;50:3974–3978. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ottaviano YL, Issa JP, Parl FF, Smith HS, Baylin SB, Davidson NE. Methylation of the estrogen receptor gene CpG island marks loss of estrogen receptor expression in human breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 1994;54:2552–2555. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lapidus RG, Ferguson AT, Ottaviano YL, Parl FF, Smith HS, Weitzman SA, Baylin SB, Issa JP, Davidson NE. Methylation of estrogen and progesterone receptor gene 5′ CpG islands correlates with lack of estrogen and progesterone receptor gene expression in breast tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 1996;2:805–810. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Huynh H, Alpert L, Pollak M. Silencing of the mammary-derived growth inhibitor (MDGI) gene in breast neoplasms is associated with epigenetic changes. Cancer Res. 1996;56:4865–4870. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Hakkarainen M, Wahlfors J, Myohanen S, Hiltunen MO, Eskelinen M, Johansson R, Janne J. Hypermethylation of calcitonin gene regulatory sequences in human breast cancer as revealed by genomic sequencing. Int J Cancer. 1996;69:471–474. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19961220)69:6<471::AID-IJC9>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Zrihan-Licht S, Weiss M, Keydar I, Wreschner DH. DNA methylation status of the MUC1 gene coding for a breast-cancer-associated protein. Int J Cancer. 1995;62:245–251. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910620303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kass DH, Shen M, Appel NB, Anderson DE, Saunders GF. Examination of DNA methylation of chromosomal hot spots associated with breast cancer. Anticancer Res. 1993;13:1245–1251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Herman JG, Merlo A, Mao L, Lapidus RG, Issa JP, Davidson NE, Sidransky D, Baylin SB. Inactivation of the CDKN2/p16/MTS1 gene is frequently associated with aberrant DNA methylation in all common human cancers. Cancer Res. 1995;55:4525–4530. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Yan PS, Rodriguez FJ, Laux DE, Perry MR, Standiford SB, Huang TH. Hypermethylation of ribosomal DNA in human breast carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2000;82:514–517. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.1999.0955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Jeronimo C, Costa I, Martins MC, Monteiro P, Lisboa S, Palmeira C, Henrique R, Teixeira MR, Lopes C. Detection of gene promoter hypermethylation in fine needle washings from breast lesions. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:3413–3417. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Krassenstein R, Sauter E, Dulaimi E, Battagli C, Ehya H, Klein-Szanto A, Cairns P. Detection of breast cancer in nipple aspirate fluid by CpG island hypermethylation. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:28–32. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-0410-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Evron E, Dooley WC, Umbricht CB, Rosenthal D, Sacchi N, Gabrielson E, Soito AB, Hung DT, Ljung B, Davidson NE, Sukumar S. Detection of breast cancer cells in ductal lavage fluid by methylation-specific PCR. Lancet. 2001;357:1335–1336. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)04501-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Dua RS, Isacke CM, Gui GP. The intraductal approach to breast cancer biomarker discovery. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:1209–1216. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.1830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Pu RT, Laitala LE, Alli PM, Fackler MJ, Sukumar S, Clark DP. Methylation profiling of benign and malignant breast lesions and its application to cytopathology. Mod Pathol. 2003;16:1095–1101. doi: 10.1097/01.MP.0000095782.79895.E2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Fackler M, Malone K, Zhang Z, Schilling E, Garrett-Mayer E, Swift-Scanlan T, Lange J, Nayar R, Davidson N, Khan S, Sukumar S. Quantitative multiplex methylation-specific PCR analysis doubles detection of tumor cells in breast ductal fluid. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:3306–3310. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Shinozaki M, Hoon DS, Giuliano AE, Hansen NM, Wang HJ, Turner R, Taback B. Distinct hypermethylation profile of primary breast cancer is associated with sentinel lymph node metastasis. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:2156–2162. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Caldeira JR, Prando EC, Quevedo FC, Neto FA, Rainho CA, Rogatto SR. CDH1 promoter hypermethylation and E-cadherin protein expression in infiltrating breast cancer. BMC Cancer. 2006;6:48. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-6-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Takahashi Y, Miyoshi Y, Takahata C, Irahara N, Taguchi T, Tamaki Y, Noguchi S. Down-regulation of LATS1 and LATS2 mRNA expression by promoter hypermethylation and its association with biologically aggressive phenotype in human breast cancers. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:1380–1385. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Gustafson K, Furth E, Heitjan D, Fansler Z, Clark D. DNA methylation profiling of cervical squamous intraepithelial lesions using liquid-based cytology specimens: an approach that utilizes receiver-operating characteristic analysis. Cancer. 2004;102:259–268. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Feng Q, Balasubramanian A, Hawes S, Toure P, Sow P, Dem A, Dembele B, Critchlow C, Xi L, Lu H, McIntosh M, Young A, Kiviat N. Detection of hypermethylated genes in women with and without cervical neoplasia. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:273–282. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]