Abstract

BACKGROUND

In preliminary studies, anaerobic RBC storage reduced oxidative damage and phosphatidylserine exposure while maintaining ATP levels. The purpose of this study was to compare the 24-hour recovery and lifespan of autologous RBCs stored 6 and 9 weeks using OFAS3 additive solution in an anaerobic environment, compared to control RBCs aerobically stored in AS-3 for 6 weeks.

METHODS

Eight subjects were entered into a randomized, cross-over study. Whole blood was collected from each subject twice separated by ≥12 wk into CP2D and leukocyte reduced. Controls were stored in AS-3. Test units in OFAS3 were oxygen depleted with Argon then stored 9 wk in an anaerobic chamber at 1–6°C. At the end of each storage period, RBC were labeled with 51Cr and 99mTc and reinfused to the subject following standard methods to determine double label recovery and lifespan. Hypotheses tests were conducted using paired, repeated-measures ANOVA.

RESULTS

Recovery for the anaerobically stored test RBC was significantly better than control at 6 weeks (p=0.023). Test units at 9 wk were not different than the 6 wk control units (p=0.73). Other in vitro measures of RBC characteristics followed the same trend. Two test units at 9 wk had hemolysis > 1%.

CONCLUSION

Anaerobically stored RBC in OFAS-3 has superior recovery at 6 weeks compared to the Controls and equivalent recovery at 9 weeks with no change in lifespan. Anaerobic storage of RBC may provide an improved RBC for transfusion at 6 wk of storage and may enable extending storage beyond the current 42 day limit.

Introduction

Storage under anaerobic conditions to minimize product degradation is a widespread practice in the pharmaceutical and food industries. We investigated this technique for refrigerated red blood cell (RBC) storage based on the RBC’s unique characteristics of not requiring oxygen to support essential metabolic processes. In a series of reports, we have shown that anaerobic storage generally enhanced the metabolic status of the RBC as well as increasing the potential storage time using a variety of additive solutions without exhibiting significant negative consequences; except for an occasional increase in hemolysis1–5. When we evaluated the putative additional benefit of an alkaline additive solution6 with anaerobic storage, we observed that storage under anaerobic conditions yielded insignificant benefits in terms of 24-hr recovery or ATP levels. However, when the RBC additive pH was lowered from 8.1 to 6.5, significant improvement in metabolic parameters were observed under anaerobic conditions2. The 24-hr RBC recovery was reasonably maintained in a pilot study even after 12 weeks when red cells were stored under anaerobic conditions with acidic additive and supplemented with rejuvenation solution (Rejuvesol, Cytosol Laboratories, Braintree, MA) at the 7th and 11th week without warming the units. Previous investigations of anaerobic storage have been limited because they relied upon historical controls. Thus, the specific contributions from acidic additive and anaerobic storage to the improved 24-hr recovery could not be determined. The purpose of the present study is to see if anaerobic storage of RBC in an acidic additive solution is superior to conventionally, aerobically stored RBC after 6 weeks as indicated by 24-hr recovery and RBC lifespan.

Materials and Methods

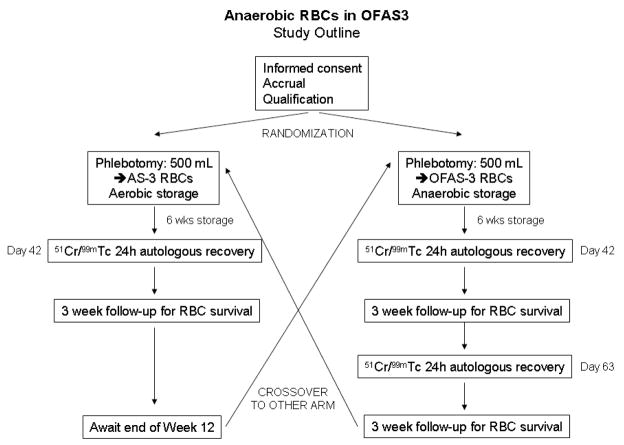

We designed a randomized controlled, cross-over study to evaluate the 24-hour recovery and lifespan of 6 and 9 week old autologous RBCs stored using OFAS3 additive solution in an anaerobic environment [test], compared to control RBCs stored using a licensed additive solution in an aerobic environment after 6 weeks of storage [control], cf. Figure 1. The study was conducted at Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center with the authorization of the Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects and under an approved Investigational New Drug application. Written informed consent was obtained from 8 normal, healthy subjects meeting FDA (21CFR640) and AABB7 donation criteria. Whole blood (500±50mL) was collected from each subject on two occasions, separated by a minimum of 12 weeks. Subjects were assigned to the test or control groups at the time of the first whole blood donation to balance the number of first donations in each group. Subjects donated one unit of whole blood into a standard, licensed primary collection container with CP2D anticoagulant solution (Pall Medical Covina, CA). Collected blood was leukocyte-reduced by means of an integral, whole blood leukocyte reduction filter and processed by centrifugation into RBCs by removing plasma and adding either 110 mL AS-3 (Nutricel, Pall Medical, Covina CA) or 200 mL OFAS3 (University of Iowa School of Pharmacy, Iowa City, Iowa) (Table 1).

Figure 1. Study design.

Eight study subjects were randomly assigned to test or control study arms. A minimum of 56 days elapsed between RBC collections.

Table 1.

RBC Additive Solutions. (mM)

| AS-3 | OFAS-3 | |

|---|---|---|

| Adenine | 2.2 | 2 |

| Glucose | 55.5 | 110 |

| Mannitol | 0 | 55 |

| NaCl | 70.1 | 26 |

| Na2HPO4 | 20 | 12 |

| Citric acid | 12 | |

| pH | 5.8 | 6.5 |

The anaerobic environment was established for the test units as previously described 3. Briefly, the blood was transferred to a 1000 mL polyvinyl chloride transfer bag (Baxter Healthcare, Round Lake, IL), and oxygen was depleted by six cycles of gas exchange with ultra-pure Argon through a sterilely connected 0.22 μm filter. The blood was transferred to a 600 mL transfer pack (Baxter) for storage in an anaerobic chamber (Difco BBL, Detroit, MI) that was filled with 10% hydrogen and 90% argon in the presence of a palladium catalyst to prevent re-oxygenation and to further deplete oxygen during storage. The RBC unit was gently mixed and the chamber was recharged weekly for up to 9 weeks of storage. Control units were leukoreduced, processed into AS-3 red cells and stored undisturbed for 6 weeks. All units were stored at 1–6° C in a monitored refrigerator.

The in vitro and in vivo portions of this study were conducted concurrently. An evaluation of RBC function was conducted on the day of donation and the day of infusion at weeks 6 and/or 9 using a standard panel of in vitro assessments. Automated hematology testing was performed on the Bayer Advia 120 (Bayer Corp., Diagnostic Division, Norwood, MA). Spun hematocrits were tested using the Hettich Mikro 20 microhematocrit centrifuge (Hettich, Tuttilingen, Germany). Post-filtration leukocyte enumeration was performed via flow cytometry (LeukoCount, Becton-Dickinson, San Jose, CA). Supernatants from the units were prepared for analysis by double centrifugation at 3600 rpm for 10 min (Hettich Rotanta 460RS, Tuttlingen, Germany). Supernatant sodium and potassium concentrations were determined by ion-specific electrodes, and glucose was determined by glucose oxidase (PPE, Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN). Lactate was analyzed via a lactate oxidase/peroxidase endpoint reaction on the Cobas Integra (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN). The pH, pCO2, and pO2 were measured at 37°C on a blood gas analyzer (Model 855 or 248, Bayer Corp., Diagnostic Division, Norwood, MA). Supernatant samples were analyzed for red cell hemoglobin using a Drabkin’s reagent method (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) automated on the COBAS FARA (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) with a turbidity correction. A red cell perchloric acid extract was neutralized with 3M K2CO3 and analyzed for ATP using the NADP+ reduction method of Beutler automated for the COBAS FARA, and 2,3-DPG (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim). RBC morphology was determined after the method of Usry 8. Microbiological screening was performed by injecting 4–5mL of RBC one week prior to infusion into aerobic and anaerobic culture bottles (BTA FA, BTA FN) and testing in the BacT/ALERT 3D system (bioMerieux, Durham, NC).

The radiolabel red cell recovery on test and control units was conducted following standard techniques as previously described9,10. At the end of the specified storage interval (6 and/or 9 weeks), the unit was well mixed by hand and approximately 15 mL of the red cells were labeled with 51Cr using standard techniques. The labeling agent, 51Cr sodium chromate, was mixed aseptically with the red cells at room temperature for 30 minutes. A saline wash was conducted. An aliquot of the final volume was reserved for assay as a standard, and the remaining labeled cells (approximately 10 mL) were injected into a free-flowing peripheral vein. Samples (5 mL each) were taken from a contralateral vein at 0, 5, 7,5, 10, 12.5, 20 and 25 minutes as well as 2 samples at 24 hours through a butterfly needle. Additional samples for determination of RBC survival were taken at 1 day, 2 days, 3 days, 1 week, 2 weeks, and 3 weeks following reinfusion. The samples were counted in a gamma counter (Wallac 1282 Compugamma, Turku, Finland) to determine 51Cr activity. The exact volume of the injectate was determined by its specific activity. The intended subject dose for the first infusion was 5–10 μCi. The intended dose for the second infusion was 15–20 μCi.

A fresh sample of heparinized blood (10 mL) was collected from the subject prior to the re-infusion of 51Cr labeled red cells. The red cells were separated and treated with a sterile solution containing approximately 2.0 μg tin in sodium citrate, dextrose and sodium chloride. After 5 minutes incubation at room temperature, the red cells were washed once with 40 mL cold saline. Then 20 μCi 99mTc pertechnetate was added for a 10 minute room temperature incubation. The cells were again washed with 40 mL cold saline. The exact volume of the injectate was determined by its specific activity, a value that depends on the amount of radionuclide used and the labeling efficiency. The volume was selected to yield an injectate of 10–20 μCi of 99mTc. The 99mTc labeled cells was drawn up into the same syringe used to inject the 51Cr cells. The same samples taken for the 51Cr red cell recovery was analyzed for 99mTc activity.

An a priori assessment of sample size requirements estimated from preliminary data indicated we could expect to distinguish between the test mean and a 75% target 24 hour recovery when the test mean is either less than 70.5% or greater than 79.5% with 6 evaluable subjects at an α = 0.05 and power = 80%. Preliminary data presented here are reported as summary statistics. A mixed effects, repeated measures ANOVA model was used for hypotheses tests and estimates of the 95% confidence intervals for recovery and survival (SAS v.9.1, SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

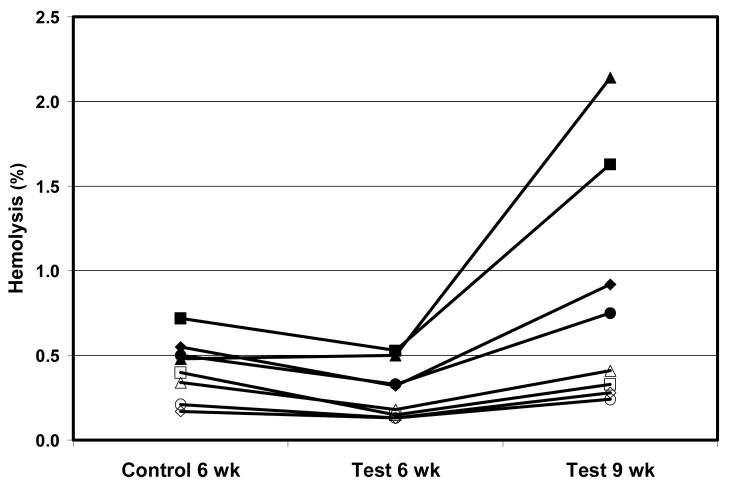

Eight subjects were entered into the study. RBC unit characteristics just prior to storage on day 0 and then at the end of the 6 and 9 week storage periods are shown in Table 2. The starting volume was larger and the Hb concentration was lower in the test units because a larger volume of additive is used compared to control. Sodium concentration was lower and glucose concentration higher because of the OFAS-3 formulation. At 6 weeks of storage, test units had significantly higher ATP content than control units (p=0.0037), and by 9 weeks the test units were not different in ATP content than the 6 weeks control (p=0.30). No significant difference in in vitro hemolysis was noted between arms at 6 weeks (p=0.31), although by 9 weeks the test units had 2 of 8 units with hemolysis over 1% and 3 of 8 over 0.8% (p=0.017 compared to 6 week control). Hemolysis over storage shows a strong relationship with the individual subject. Four of 8 subjects had very low hemolysis even up to 9 weeks of storage in OFAS3. The other 4 had distinctly higher hemolysis for all conditions (Figure 2).

Table 2. Initial conditions and summary outcomes of RBC at weeks 6 and 9.

Control and Test are paired with the order randomly assigned to first or second collection (N=8). Test units were stored anaerobically as described in the methods. Data are shown as Mean ± sd (max-min)

| Arm | Control | Test | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Additive | AS-3 | OFAS-3 | |||

| Storage | Aerobic | Anaerobic | |||

| Time | Day 0 | 6-weeks | Day 0 | 6-weeks | 9-weeks |

| SLR (%) | 77.8±5.4 83.5−67.3 |

82.3±4.6 87.5−71.9 |

73.5±8.5 83.5−61.0 |

||

| DLR (%) | 75.1±7.7 83.5−62.0 |

83.0±5.0** 87.7−72.2 |

72.6±10.5@ 85.7−54.1 |

||

| Lifespan (days) | 84±16# 112−58 |

82±12# 97−67 |

86±7# 98−74 |

||

| Volume (mL) | 393±62 493−334 |

378±63 482−322 |

444±25 493−414 |

431±28 481−392 |

376±28 425−348 |

| pH (37°C) | 6.83±0.04 6.90−6.79 |

6.44±0.07 6.56−6.36 |

6.89±0.03 6.96−6.86 |

6.32±0.04 6.39−6.30 |

6.25±0.05 6.32−6.20 |

| Hb (mg/dL) | 15.3±2.2 17.9−11.9 |

15.0±2.0 16.8−11.6 |

13.1±1.2 14.8−11.0 |

13.0±1.2 14.7−10.7 |

13.1±1.2 14.8−10.9 |

| MCV (fL) | 92±4 99−84 |

97±5 104−88 |

98±5 107−92 |

99±6 110−91 |

101±6 109−89 |

| RDW (%) | 14.2±1.9 17.7−12.1 |

14.2±2.2 18.5−12.3 |

14.2±2.0 17.5−12.6 |

16.3±2.5 20.2−14.0 |

15.7±2.6 19.8−13.1 |

| Na (mmol/L) | 165±2 168−164 |

136±6 145−128 |

98±5 108−91 |

80±6 89−73 |

75±6 88−69 |

| K (mmol/L) | 2.1±0.3 2.4−1.7 |

37.1±6.8 47.1−26.2 |

1.6±0.2 2.1−1.4 |

30.4±3.6 37.6−26.3 |

36.3±3.7 42.2−31.3 |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 721±19 748−695 |

547±37 594−490 |

1209±76 1307−1096 |

920±39 971−864 |

900±34 962−853 |

| Lactate (mmol/L) | 3±4 13−1 |

22±6 29−14 |

2±0 2−1 |

25±4 30−21 |

31±2 34−29 |

| Morphology (%) | 100±1 100−99 |

51±18 73−24 |

98±4 100−87 |

63±17 87−43 |

54±15 75−25 |

| ATP (μmol/gHb) | 3.59±0.91 4.46−1.67 |

2.93±0.80 4.28−1.95 |

3.48±0.86 4.17−1.50 |

3.76±0.62 4.55−2.98 |

2.71±0.69 3.75−1.86 |

| Hemolysis (%) | 0.06±0.03 0.10−0.03 |

0.4±0.2 0.7−0.2 |

0.06±0.03 0.13−0.03 |

0.3±0.2 0.5−0.2 |

0.8±0.7 2.1−0.2 |

p=0.023 compared to control

p=0.041 compared to control

no difference in study arms, p=0.073

Figure 2. Hemolysis over storage.

Percent hemolysis at the end of storage for aerobically stored RBC in AS3, and anaerobically stored in OFAS3 for 6 and 9 weeks from the same subject are shown. Four subjects (solid symbols) had distinctly higher hemolysis for all conditions.

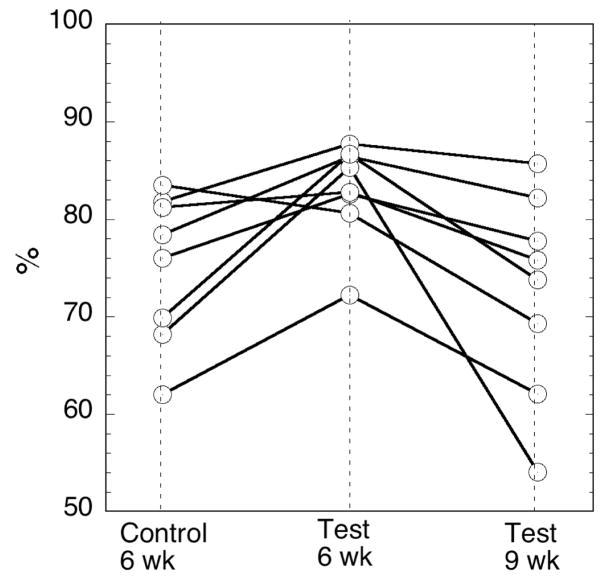

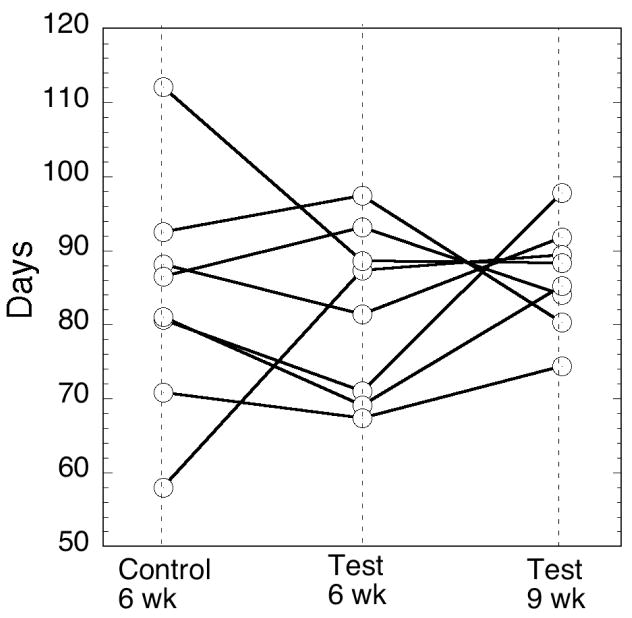

The principle purpose of the present study is to see if anaerobic storage of RBC in an acidic additive solution is superior to conventionally, aerobically stored RBC after 6 weeks as indicated by 24-hr recovery and RBC lifespan. The primary outcome of 24 hour recovery of radiolabeled cells is shown in Table 2 for both the single label calculation method (SLR) and the dual label calculation method (DLR). Recovery for the anaerobically stored test RBC had 7.9±2.7% higher 24 hour DLR than the standard control at 6 weeks (p=0.023). Test at 9 weeks was not different than the 6 week Control (p=0.41). There was no difference in the secondary outcome of Lifespan across the three arms in a global test of hypothesis (ndf=2 ddf=7 p=0.73). The individual DLR and Lifespan results by subject are plotted in Figures 3 and 4.

Figure 3. 24 h Recovery (DLR) by subject.

Control at 6 weeks, Test at 6 weeks and Test at 9 weeks. There is no difference demonstrated between Control 6 weeks and Test 9 weeks (p=0.41). Test at 6 weeks is superior to Control at 6 weeks (p=0.023).

Figure 4. Lifespan by subject.

Control at 6 weeks, Test at 6 weeks and Test at 9 weeks. There is no difference between the 3 study arms (p=0.73).

Discussion

RBC storage under anaerobic condition in OFAS-3 had superior 24 hour recovery at 6 weeks of storage with no compromise in lifespan compared to a standard control RBC stored under aerobic conditions. By 9 weeks, the 24 hour recovery was diminished to approximately that of control units stored 6 weeks. Other in vitro RBC characteristics of ATP content and morphology were also similar between the 9 week test and 6 weeks control units. Although test units had lower hemolysis compared to control after 6 weeks, it was greater in the test units after 9 weeks. Previous anaerobic storage studies with various additives did not show high hemolysis accompanying acceptable 24 hr recovery.1–5 The cause of the present observations is unknown. The data in Figure 2 suggests hemolysis may be a subject dependent phenomenon. Additional work is indicated to understand and prevent this hemolysis in RBCs of more susceptible individuals over storage.

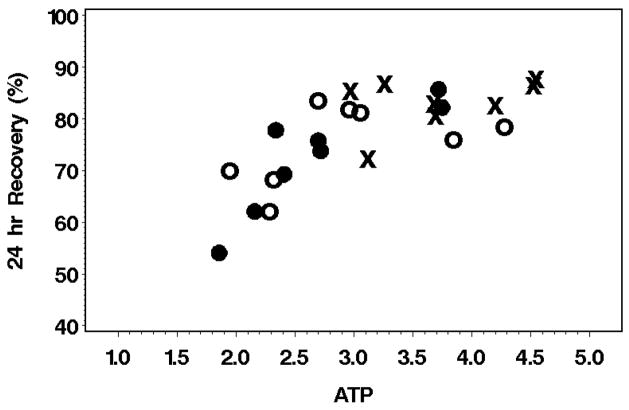

RBC 24 hour recoveries were related to the RBC ATP concentration (Figure 5) as previously reported by several investigators11. While it is tempting to assign a causal relationship to the ATP level or to other in vitro characteristics of the RBC such as morphology or hemolysis, all the these variables are highly correlated with each other, making true cause and effect deductions difficult.

Figure 5. RBC ATP content affects 24 hr RBC Recovery.

ATP (μmol/g-Hb) content in the RBC on the day of study is shown against the 24 hr RBC in vivo recovery. AS-3 6-week (o), OFSA3 6-week (x), OFSA2 9-week (●)

Of particular interest in the study are the 24 hour recoveries when examined in light of the most recent FDA performance criteria12. The SLR observed here for control RBC at 6 weeks (77.8±5.4% with 2 out of 8 less than 75%) has only a 11.5% chance of passing the current FDA criteria of 21–24-hour recoveries ≥75% out of 24 tested13. The 6 week anaerobically stored test units (SLR=82.3±4.6% with 1 of 8 less than 75%) would stand a better chance (64.8%) of passing these criteria with a reasonable number of study subjects, although this chance is still disappointingly low even though superiority to control units at 6 weeks has been demonstrated.

The observed 8% increase in recovery rate translates to approximately a one-third reduction in the quantity of non-viable red cells transfused, representing a potentially significant benefit to patients who are chronically or massively transfused, since non-viable cells will not only be nonfunctional, they will also increase the iron over-load and potentially stress the reticuloendothelial system. Currently, only 3.2% of collected units get discarded due to outdating14. Thus, there are no immediate needs for significant extension of storage time, at least in countries with a well developed infrastructure. On the other hand, there have been numerous reports that suggested the negative consequences of transfusing cells stored for extended time15–19. However, due to small sample sizes or inadequate controls, those studies have not been conclusive. This, coupled with numerous reports highlighting negative consequences of transfusion (positive correlations between number of units transfused and negative outcomes) 20,21,22,23,24, suggests possible clinical advantages that might accrue with improving the storage conditions for red cells.

Anaerobically stored red cells may offer attractive alternatives to the current practice if the development of storage lesions can be significantly delayed, thereby providing red cells with improved in vitro characteristics and in vivo recoveries within the current distribution systems. The methods used to demonstrate feasibility in study are not amenable to implementation within the current component preparation methods and practices. Development of improved methods for a simple and cost effective method to deplete oxygen from collected blood without modifying the current blood banking infrastructure is indicated.

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by grant from National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute 1R43HL088848-01.

The authors thank Louise Herschel, MLT (ASCP), CCRC, Sharry Baker, MT(ASCP), Deborah F. Dumont MT(ASCP)SBB, Susan Waters, MLT(ASCP), and the staff in the Blood Donor Program at Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, for their excellent technical support of these studies. Supported by a grant from National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute 1R43HL088848-01 and New Health Sciences Inc. Dr. Yoshida is an employee of New Health Sciences Inc.

References

- 1.Yoshida T, Lee J, McDonough W, et al. Anaerobic storage of red blood cells for 9 weeks: In vivo and in vitro characteristics. Transfusion. 1997;37s:104S. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yoshida T, AuBuchon JP, Dumont LJ, et al. The effects of additive solution pH and metabolic rejuvenation on anaerobic storage of red cells. Transfusion. 2008 doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2008.01812.x. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yoshida T, Aubuchon JP, Tryzelaar L, et al. Extended storage of red blood cells under anaerobic conditions. Vox Sang. 2007;92:22–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1423-0410.2006.00860.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yoshida T, Bitensky MW, Tryzelaar L, et al. Effect of oxygen removal on 9-week storage of red blood cells in EAS61 additive solution. Transfusion. 2000;40S:56S. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yoshida T, Bitensky MW, Pickard CA, et al. 9-week storage of red blood cells in AS3 under oxygen depleted conditions. Transfusion. 1999;39:109S. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hess JR, Rugg N, Knapp AD, et al. Successful storage of RBCs for 9 weeks in a new additive solution. Transfusion. 2000;40:1007–11. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.2000.40081007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.AABB. AABB Technical Manual. 15. Bethesda: AABB; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Usry RT, Moore GL, Manalo FW. Morphology of stored, rejuvenated human erythrocytes. Vox Sang. 1975;28:176–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1423-0410.1975.tb02756.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.The International Committee For Standardization In Hematology. Recommended methods for radioisotope red cell survival studies. Blood. 1971;38:378–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moroff G, Sohmer PR, Button LN. Proposed standardization of methods for determining the 24-hour survival of stored red cells. Transfusion. 1984;24:109–14. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1984.24284173339.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heaton WA. Evaluation of posttransfusion recovery and survival of transfused red cells. Transfus Med Rev. 1992;6:153–69. doi: 10.1016/s0887-7963(92)70166-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dumont DF. Evaluation of Proposed FDA Criteria for the Evaluation of Radiolabeled Red Cell Recovery Trials US Food and Drug Administration. Blood Products Advisory Committee. 2008 May 1; doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2008.01642.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dumont LJ, AuBuchon JP. Evaluation of proposed FDA criteria for the evaluation of radiolabeled red cell recovery trials. Transfusion. 2008 doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2008.01642.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.AABB. The 2005 Nationwide Blood Collection and Utilization Survey Report. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zallen G, Offner PJ, Moore EE, et al. Age of transfused blood is an independent risk factor for postinjury multiple organ failure. Am J Surg. 1999;178:570–2. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(99)00239-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Purdy FR, Tweeddale MG, Merrick PM. Association of mortality with age of blood transfused in septic ICU patients. Can J Anaesth. 1997;44:1256–61. doi: 10.1007/BF03012772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shah DM, Gottlieb ME, Rahm RL, et al. Failure of red blood cell transfusion to increase oxygen transport or mixed venous PO2 in injured patients. J Trauma. 1982;22:741–6. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198209000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mink RB, Pollack MM. Effect of blood transfusion on oxygen consumption in pediatric septic shock. Crit Care Med. 1990;18:1087–91. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199010000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koch CG, Li L, Sessler DI, et al. Duration of red-cell storage and complications after cardiac surgery. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1229–39. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa070403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hebert PC, Wells G, Blajchman MA, et al. A multicenter, randomized, controlled clinical trial of transfusion requirements in critical care. Transfusion Requirements in Critical Care Investigators, Canadian Critical Care Trials Group. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:409–17. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199902113400601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vincent JL, Baron JF, Reinhart K, et al. Anemia and blood transfusion in critically ill patients. JAMA. 2002;288:1499–507. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.12.1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spiess BD. Blood transfusion: the silent epidemic. Ann Thorac Surg. 2001;72:S1832–7. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(01)03259-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McCrossan L, Masterson G. Blood transfusion in critical illness. Br J Anaesth. 2002;88:6–9. doi: 10.1093/bja/88.1.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tinmouth A, Fergusson D, Yee IC, Hebert PC. Clinical consequences of red cell storage in the critically ill. Transfusion. 2006;46:2014–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2006.01026.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]