Abstract

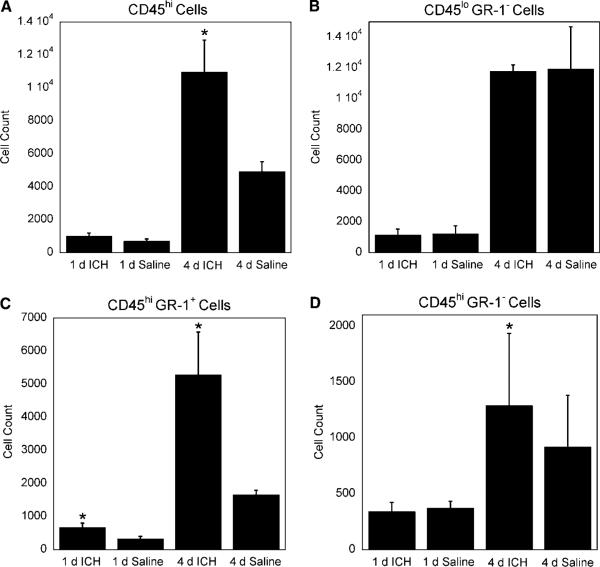

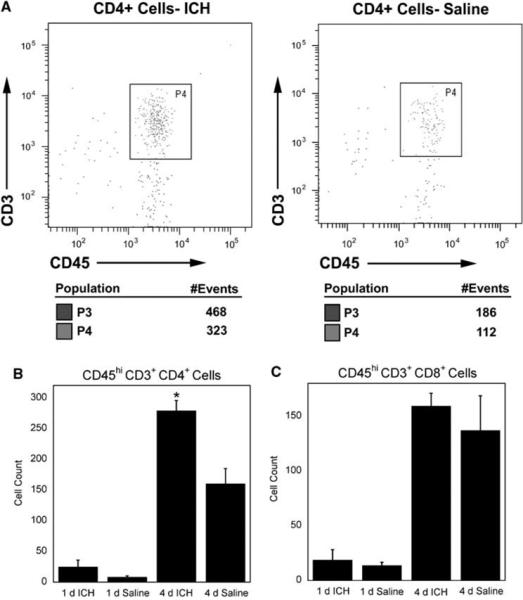

Intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) is a stroke subtype with high rates of mortality and morbidity. The immune system, particularly complement and cytokine signaling, has been implicated in brain injury after ICH. However, the cellular immunology associated with ICH has been understudied. In this report, we use flow cytometry to quantitatively profile immune cell populations that infiltrate the brain 1 and 4 days post-ICH. At 1 day CD45hi GR-1 + cells were increased 2.0-fold compared with saline controls (P≤0.05); however, we did not observe changes in any other cell populations analyzed. At 4 days ICH mice presented with a 2.4-fold increase in CD45hi cells, a 1.9-fold increase in CD45hi GR-1− cells, a 3.4-fold increase in CD45hi GR-1 + cells, and most notably, a 1.7-fold increase in CD4+ cells (P≤0.05 for all groups), compared with control mice. We did not observe changes in the numbers of CD8 + cells or CD45lo GR-1− cells (P = 0.43 and 0.49, respectively). Thus, we have shown the first use of flow cytometry to analyze leukocyte infiltration in response to ICH. Our finding of a CD4 T-cell infiltrate is novel and suggests a role for the adaptive immune system in the response to ICH.

Keywords: inflammation, intracerebral hemorrhage, leukocyte infiltration, stroke

Introduction

Intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH), a bleeding into the brain parenchyma, can occur in neonates, children, or adults either spontaneously or as a result of trauma (Qureshi et al, 2001; Kase and Caplan, 1994). ICH is the stroke subtype with the highest rates of mortality and morbidity; only 38% of patients survive for 1 year (Xi et al, 2006; Foulkes et al, 1988; Qureshi et al, 2001). Breakdown of the blood-brain-barrier (BBB) is well documented in ICH, leading to extravasation of plasma proteins and marked perihematomal interstitial and vasogenic edema (Xi et al, 2006; Liu and Sturner, 1988; Wagner et al, 1996).

There are numerous reports indicating that various immune components are associated with the hemorrhagic milieu after ICH, including proinflammatory cytokines, complement components, microglial activation, and neutrophil infiltration (Xi et al, 2006; Wang and Dore, 2007; Wagner, 2007; Jenkins et al, 1989; Gong et al, 2004). However, there is very little work detailing the types of leukocytes that enter the brain after ICH. Furthermore, studies that do exist are largely limited to immunohistochemical techniques. A more precise assessment of these leukocytes, including determining the frequency of central nervous system (CNS) infiltrating immune cells, is needed to understand the role of the immune system in the pathogenesis of ICH-induced brain injury.

In this report, we are the first to use flow cytometry to quantitatively study the leukocytes that enter the brain after experimental ICH in mice. We report that ICH leads to an increase in immune cell populations, including CD4 T cells and total blood-derived leukocytes, with concomitant alterations in physiologic and behavioral parameters. These data suggest a role for CNS inflammation in ICH.

Materials and methods

Animals

Unless otherwise noted, all materials and reagents were purchased from Sigma (St Louis, MO, USA).

All animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). Male C57BL/6J mice (approximately 20 to 30 g) were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, NE, USA). Animals were housed in standard laboratory housing and allowed ad libitum access to food and water.

ICH Model

Mice were anaesthetized with 2% isoflurane in 24% oxygen and 74% nitrous oxide, administered through an anesthesia mask (Kopf, Tujunga, CA, USA). Deep sedation was monitored throughout the procedure by the absence of pain reflexes in the toes and pupils. Body temperature was held at 37°C with a feedback-controlled heating blanket.

Our experimental ICH procedure was based on a previously described method by Yang et al (2006), with some modifications. Mice were placed in a stereotaxic frame (Kopf). A skin incision was made along the midline of the dorsal surface of the skull, exposing the bregma. A 1 mm cranial burr hole was drilled 2.5 mm lateral and 0.5 mm anterior to the bregma. Approximately 30 μL of autologous blood was collected by clipping a small portion of the distal tail. Further bleeding was prevented by cauterization of the tail. Blood was drawn into a 50 μL Hamilton syringe with a 26-gauge needle. The needle was inserted 4 mm ventral through the cranial hole into the brain and 20 μL of blood or sterile saline was infused more than 15 mins. After infusion, the hole in the skull was filled with dental cement and the incision was closed. Mice were allowed to survive for 1- or 4-days post-ICH, at which time they were euthanized with isoflurane and decapitation.

Brain Water Content Measurement

Mice were euthanized and brains were removed and immediately weighed on an analytical balance. Brains were desiccated by heating at 85°C for 16 h and weighed again. Whole-brain water content was measured as a marker of edema. Brain water content was calculated according to the following formula: Brain water content = (wet weight–dry weight)/wet weight (Yang et al, 2006).

Motor Deficit

Motor deficits were assessed using the rotarod task (Jeong et al, 2003). The amount of time mice were able to stay on the top of the rotating rod (32 r.p.m., constant speed) was measured before surgery and again before euthanasia. The percent change from presurgery to the time before euthanasia was calculated. This value was used in the comparison between the blood infused and saline-infused groups.

Isolation of Central Nervous System Immunologic Cells

Cells were isolated as described previously (Kang et al, 2002). Briefly, excised mouse brains were pushed through a nylon cell strainer (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) with a 100-μm pore width and incubated at 37°C for 45 mins in 250 μg/mL collagenase type 4 (Worthington Biochemical Corp., Lakewood NJ, USA). Immunologic cells were then concentrated via continuous Percoll gradient (Pharmacia, Piscataway, NJ, USA) centrifugation at 10,000 r.p.m. (Sorvall SS-34 rotor) for 30 mins. The resulting layer of immunologic cells was then collected and placed into a 50 mL falcon tube. RPMI (1 ×) was added until the final volume was 50 mL and the solution was then centrifuged at 1500 r.p.m. (Sorvall Legend RC centrifuge) for 10 mins. The resulting cell pellet was resuspended in fluorescence-activated cell sorting buffer (1% bovine serum albumin and 2% sodium azide).

It is important to note that the hematoma was filtered out of cell suspensions before flow cytometric analysis. Therefore, flow cytometric analysis was not influenced by cells potentially residing within the hematoma itself. Further, it is unlikely that cells would remain viable 1 or 4 days post-ICH within a blood clot. Thus the cell populations observed are highly likely to only be leukocytes that infiltrated into the parenchyma from the periphery or from the hematoma during retraction of the clot.

Flow Cytometric Analysis

Cells isolated from the CNS were stained with anti-CD4 PE, anti-CD8 FITC, anti-CD3 APC, anti-CD45 PE-Cy7, and anti-Gr-1 APC-Cy7 on ice for 45 mins. Samples were then washed twice with fluorescence-activated cell sorting buffer, resuspended in cold phosphate-buffered saline, and fixed in 1% paraformaldehyde. Samples were then analyzed on a BD LSRII instrument (BD Biosciences).

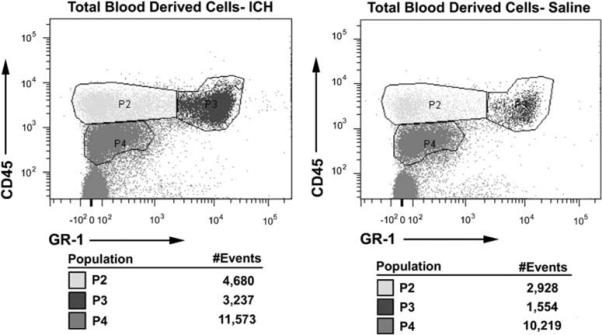

Raw data were displayed with side scatter along the y axis and forward scatter along the x axis. A gate was placed according to the profile of inflammatory cells as previously determined (Johnson et al, 1999, 2001). This parent population was then examined on a scatterplot with CD45 expression on the y axis and GR-1 expression on the x axis as shown in Figure 2. Cell populations that expressed CD45 at 103 channels or higher and CD3 at 102.5 channels or higher were considered a population of interest and gated for analysis. Cells that expressed the CD4 cell-surface marker at 103 channels or higher and showed a side scatter of 40,000 or less were selectively gated and then plotted. Likewise, cells that expressed the CD8 cell-surface marker at 103 channels or higher and showed a side scatter of 40,000 or less were selectively gated and then plotted. Using flow cytometric analysis of brain-isolated inflammatory cells, we determined that similar ratios of leukocyte populations were present in the brains of both ICH and saline-treated mice. Therefore, absolute numbers of inflammatory cells were considered to perform statistical analyses.

Figure 2.

Representative scatter plots showing analysis of CD45hi cells at 4 days in a mouse receiving intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) and a saline control. An overall increase in CD45hi inflammatory cell infiltrate was observed at 4 days post-ICH, compared with saline-treated mice (P≤0.05), but not at 1 day (P = 0.11). Cells were considered to be CD45hi if they expressed CD45 at 103.2 channels or higher. These cells were then gated and counted for statistical analysis. Gate P2 is considered to be CD45hi GR-1−, gate P3 is considered to be CD45hi GR-1 +, and gate P4 is considered to be CD45lo GR-1−.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed with the statistical package in Microsoft Excel using Student's t-test or a paired t-test. The level of significance was ≤0.05.

Results

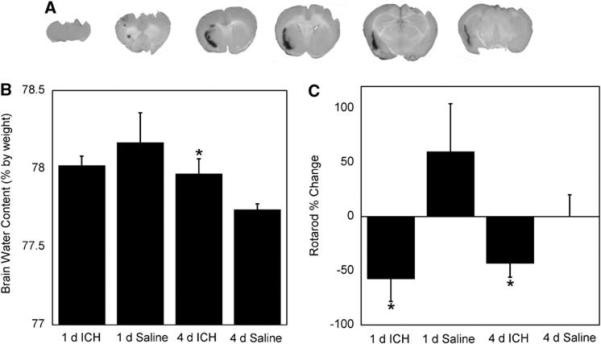

To verify our ICH model, we fixed and sectioned some of the brains to inspect the hematoma. Figure 1A shows a representative brain, cut in 2 mm serial sections. Visual examination of the brain reveals a mild to moderate hemorrhage with the hematoma centered in the anterolateral portion of the left hemisphere extending into the striatum. There is also some observable perihematomal edema.

Figure 1.

Physiologic and behavior changes associated with intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH). (A) ICH produced a mild to moderate hematoma in the anterolateral portion of the brain near the striatum. (B) ICH led to increased edema at 4 days when compared with saline-treated mice (n = 4 to 6 per group, P≤0.05). Edema was measured as total brain water content. (C) ICH showed poorer motor function at 1 and 4 days compared with saline controls (baseline versus 1 or 4 days; n = 6 to 7 per group, P≤0.05). Bars are mean ± s.e.m.; *P≤0.05 compared with saline of the same time point.

Figure 1B shows the results of whole-brain water content measurements, used as a marker of edema. At 4-day ICH, animals had a small, but statistically significant, increase in brain water content compared with saline controls (78.0 versus 77.7%; P≤0.05). We did not observe increased brain water content at 1-day post-ICH. We used the rotarod task to assess motor deficits resulting from ICH (Jeong et al, 2003). At 1 and 4 days the ICH group showed a poorer rotarod performance compared with saline controls (presurgery compared with immediately before euthanasia; P≤0.05). These results are shown in Figure 1C. Lee et al (2006) have also shown rotarod differences between ICH and control groups in a rat model of ICH.

An immune response after ICH in humans and animal models has been noted (Xi et al, 2006; Gong et al, 2000; Xue and Del Bigio, 2000, 2005). We wished to characterize the immune response in our ICH model 1 and 4 days post-ICH because important clinical sequelae begin to appear between 1 and 5 days post-ICH (Qureshi et al, 2001). Using flow cytometric analysis we have showed that similar leukocyte populations were present in the brains of both saline and ICH mice; however, the numbers specific inflammatory cell types differed in ICH mice as compared with saline controls. At 1 day, we observed an increase in CD45hi GR-1 + cells (P≤0.05) compared with saline controls, but did not find changes in CD45hi (P = 0.11), CD45lo GR-1− (P = 0.46), CD8 + (P = 0.32), CD4 + (P = 0.13), or CD45hi GR-1− (P = 0.39) cells. At 4 days, we did not observe any difference in CD45lo GR-1− (P = 0.49) or CD8 + cell populations (P = 0.43) between ICH and saline groups. However, at 4 days, ICH mice had a statistically significant increase in CD45hi cells (P≤0.05), CD4 + cells (P≤0.05), CD45hi GR-1− cells (P≤0.05), and CD45hi GR-1 + cells (P≤0.05) over saline-treated mice.

Discussion

In this study, we have examined leukocyte trafficking into the CNS after ICH. Our goal was to use a quantitative method to define the inflammatory cell infiltrate after ICH and to associate this leukocyte infiltration with pathophysiological data. There is a paucity of flow cytometric data in the literature defining the specific inflammatory cell types that infiltrate into the parenchyma during brain inflammation. However, multiple sclerosis has been characterized with regard to leukocyte infiltration. In contrast to our findings with ICH, CD8 + T cells traffic into the brain, in addition to other cell types, during multiple sclerosis (Johnson et al, 1999).

Leukocytes, particularly T cells, traffic into the CNS under normal physiologic conditions. However, under these conditions, cells rarely enter the brain parenchyma and do not remain in the CNS for long periods of time unless they experience antigen and become activated (Ransohoff et al, 2003; Hickey, 1999; Engelhardt and Ransohoff, 2005). Immune trafficking into the brain parenchyma as a part of the stroke pathologic assessment has gone relatively unstudied. A previous report has used histochemical and immunohistochemical methods to show the presence of neutrophils, microglia, and CD8a + cells in the brain after experimental ICH in the rat (Xue and Del Bigio, 2000). However, our use of flow cytometry extends these observations and enables one to rapidly identify and quantify these cell types, as well as their ratios to one another.

There are two possible sources of leukocytes found in the brain parenchyma after ICH. Some cells will migrate from the hematoma into the perihematomal tissue and others will enter through an open BBB (Xi et al, 2006). As noted previously, we observed similar populations, but different numbers of immune cells among ICH and saline mice. This is likely because of the fact that the saline treatment produces a small amount of brain injury as a result of the needle tracks, microhemorrhages, and mass effect from the volume of the injection.

We chose 1 and 4 days time points for this analysis based on the amount of erythrocyte lysis and subsequent inflammatory stimuli. In rodent models of ICH, erythrocyte lysis is low at 1 day and high at 4 days (Wagner et al, 2003). Because erythrocyte products may contribute to inflammation, this is a logical choice of time points. Our observation of increased T cells at 4 days but not 1 day suggests recruitment from the periphery as opposed to the hematoma.

A significant increase in CD45hi GR-1 + cells at 1 and 4 days was observed in ICH mice compared with saline controls (Figures 2 and 3C). A CD45hi GR-1 + cell population is mostly comprised of neutrophils. An increase in neutrophils is not surprising at these time points, as these cells are a part of the innate immune response and typically are among the first inflammatory cells to migrate to the site of injury (Fagan et al, 2004). These cells perform pattern recognition responses as well as promote inflammation (Fagan et al, 2004). Our observed CD45lo GR-1− profile is characteristic of a microglia population (Mack et al, 2003; Figures 2 and 3B). Like neutrophils, microglia are part of the innate immune system. Similar numbers of microglia in ICH and saline mice suggest that this cell type does not proliferate specifically in response to ICH.

Figure 3.

Assessment of blood-derived inflammatory cells in the CNS 1 and 4 days after intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH). Brain infiltrating inflammatory cells were stained with anti-CD45, a pan marker for blood-derived cells, and anti-GR-1 antibodies. GR-1 is a pan surface marker for granulocytes. (A) At 4 days there were an increased number of blood-derived leukocytes in ICH brains compared with saline-treated brains (P≤0.05); this was not observed at 1 day (P = 0.11). (B) We did not observe a difference in CD45lo GR-1− cells (microglia) between ICH and saline mice at 1 or 4 days (P = 0.46 and P = 0.49, respectively). Conversely, we found an increased CD45hi GR-1 + cell population (neutrophils) at 1 and 4 days (C)(P≤0.05) and an increased CD45hi GR-1− cell population (cells of the lymphoid lineage and macrophages) at 4 days, but not 1 day (D) (P≤0.05 and P = 0.39). N = 3 to 4 per group; bars are mean±s.e.m.; *P≤0.05 compared with saline of the same time point.

On analysis of T lymphocyte subsets, we did not observe a difference in CD8 + cells between ICH and saline mice at either time point (Figure 4C). Conversely, we observed a significant increase in CD4 + cells in ICH-treated mice at 4 days but not 1 day (Figure 4B). These CD4 + cells are likely to be CD4 + T cells as they stain positively for CD3 and express CD45hi that is characteristic of this lymphocyte subset. CD4 + T cells are part of the adaptive immune system and may take 5 days or more to become antigen specific in the CNS (Bailey et al, 2006). Increased numbers of CD4 + T cells in ICH is interesting, as traditional helper T cells do not normally recognize syngeneic protein as antigen. This suggests that the increased numbers of CD4 + cells in ICH could be the result of bystander activation or the recognition of endogenous antigens that have become newly exposed to the immune system as a result of ICH. Another possibility is that this CD4 + cell population contains regulatory T cells. CD4 + regulatory T cells have been shown to recognize both foreign and syngeneic antigens (Larosa and Orange, 2008; Pacholczyk et al, 2007; Fontenot and Rudensky, 2004). Therefore, it is currently unclear what functional role that the observed increase in CD4 + cells might play in the pathophysiology associated with ICH. However, there may be a chemospecific response occurring that is specific to the extravascular blood.

Figure 4.

CD4 + and CD8 + cells. (A) Representative scatter plots showing flow cytometric analysis of CD4 + cells in intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) and saline brains at 4 days. (B) We observed increased numbers of CD4 + cells in ICH mice compared with saline controls (P≤0.05) at 4 days but not at 1 day (P = 0.13; C) There was not a difference in CD8 + cells between ICH and saline mice at 1- or 4-day post-ICH (P = 0.32 and P = 0.43, respectively). N = 3 to 4 per group; bars are mean±s.e.m.; *P≤0.05 compared with saline of the same time point.

Using our model, at 4 days, we also observed a significant increase of CD45hi GR-1− cells (P≤0.05) in ICH-treated mice as compared with saline controls (Figure 3D). More than 90% of this population is CD4 and CD8−, and remains uncharacterized in our flow cytometric analysis (data not shown). Although speculative, this population could contain macrophages, B cells, natural killer cells, as well as other blood-derived inflammatory cells. The role of these cell types remains unclear and will be the subject of future analysis in this model.

In summary, we have found infiltration of neutrophils into ICH brains at 1 day, and infiltration of several leukocyte populations at 4-day post-ICH. The observation that CD4 + T cells migrate into the brain in this murine model is significant because it implies a role for the adaptive immune system in ICH. This study therefore shows the need for future research designed to adequately define the contribution of specific helper T-cell subsets in ICH.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by a grant from the NIH: R01NS050569 (JFC).

Footnotes

Disclosures/conflict of interest

The authors state no disclosures or conflict of interest.

References

- Bailey SL, Carpentier PA, McMahon EJ, Begolka WS, Miller SD. Innate and adaptive immune responses of the central nervous system. Crit Rev Immunol. 2006;26:149–88. doi: 10.1615/critrevimmunol.v26.i2.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelhardt B, Ransohoff RM. The ins and outs of T-lymphocyte trafficking to the CNS: anatomical sites and molecular mechanisms. Trends Immunol. 2005;26:485–95. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2005.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagan SC, Hess DC, Hohnadel EJ, Pollock DM, Ergul A. Targets for vascular protection after acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2004;35:2220–5. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000138023.60272.9e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontenot JD, Rudensky AY. Molecular aspects of regulatory T cell development. Semin Immunol. 2004;16:73–80. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2003.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foulkes MA, Wolf PA, Price TR, Mohr JP, Hier DB. The Stroke Data Bank: design, methods, and baseline characteristics. Stroke. 1988;19:547–54. doi: 10.1161/01.str.19.5.547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong C, Hoff JT, Keep RF. Acute inflammatory reaction following experimental intracerebral hemorrhage in rat. Brain Res. 2000;871:57–65. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02427-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong Y, Hua Y, Keep RF, Hoff JT, Xi G. Intracerebral hemorrhage: effects of aging on brain edema and neurological deficits. Stroke. 2004;35:2571–5. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000145485.67827.d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickey WF. Leukocyte traffic in the central nervous system: the participants and their roles. Semin Immunol. 1999;11:125–37. doi: 10.1006/smim.1999.0168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins A, Maxwell WL, Graham DI. Experimental intracerebral haematoma in the rat: sequential light microscopical changes. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 1989;15:477–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.1989.tb01247.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong SW, Chu K, Jung KH, Kim SU, Kim M, Roh JK. Human neural stem cell transplantation promotes functional recovery in rats with experimental intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2003;34:2258–63. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000083698.20199.1F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson AJ, Njenga MK, Hansen MJ, Kuhns ST, Chen L, Rodriguez M, Pease LR. Prevalent class I-restricted T-cell response to the Theiler's virus epitope Db:VP2121−130 in the absence of endogenous CD4 help, tumor necrosis factor alpha, gamma interferon, perforin, or costimulation through CD28. J Virol. 1999;73:3702–8. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.5.3702-3708.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson AJ, Upshaw J, Pavelko KD, Rodriguez M, Pease LR. Preservation of motor function by inhibition of CD8+ virus peptide-specific T cells in Theiler's virus infection. FASEB J. 2001;15:2760–2. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0373fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang BS, Lyman MA, Kim BS. The majority of infiltrating CD8+ T cells in the central nervous system of susceptible SJL/J mice infected with Theiler's virus are virus specific and fully functional. J Virol. 2002;76:6577–85. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.13.6577-6585.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kase CS, Caplan LR, editors. Intracerebral hemorrhage. Butterworth-Heinemann; Newton, MA: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Larosa DF, Orange JS. 1. Lymphocytes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;121:S364–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.06.016. quiz S412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee ST, Chu K, Sinn DI, Jung KH, Kim EH, Kim SJ, Kim JM, Ko SY, Kim M, Roh JK. Erythropoietin reduces perihematomal inflammation and cell death with eNOS and STAT3 activations in experimental intracerebral hemorrhage. J Neurochem. 2006;96:1728–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03697.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu HM, Sturner WQ. Extravasation of plasma proteins in brain trauma. Forensic Sci Int. 1988;38:285–95. doi: 10.1016/0379-0738(88)90174-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mack CL, Vanderlugt-Castaneda CL, Neville KL, Miller SD. Microglia are activated to become competent antigen presenting and effector cells in the inflammatory environment of the Theiler's virus model of multiple sclerosis. J Neuroimmunol. 2003;144:68–79. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2003.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacholczyk R, Kern J, Singh N, Iwashima M, Kraj P, Ignatowicz L. Nonself-antigens are the cognate specificities of Foxp3+ regulatory T cells. Immunity. 2007;27:493–504. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.07.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qureshi AI, Tuhrim S, Broderick JP, Batjer HH, Hondo H, Hanley DF. Spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1450–60. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200105103441907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ransohoff RM, Kivisakk P, Kidd G. Three or more routes for leukocyte migration into the central nervous system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:569–81. doi: 10.1038/nri1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner KR. Modeling intracerebral hemorrhage: glutamate, nuclear factor-kappa B signaling and cytokines. Stroke. 2007;38:753–8. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000255033.02904.db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner KR, Sharp FR, Ardizzone TD, Lu A, Clark JF. Heme and iron metabolism: role in cerebral hemorrhage. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2003;23:629–52. doi: 10.1097/01.WCB.0000073905.87928.6D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner KR, Xi G, Hua Y, Kleinholz M, de Courten-Myers GM, Myers RE, Broderick JP, Brott TG. Lobar intracerebral hemorrhage model in pigs: rapid edema development in perihematomal white matter. Stroke. 1996;27:490–7. doi: 10.1161/01.str.27.3.490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Dore S. Inflammation after intracerebral hemorrhage. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2007;27:894–908. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xi G, Keep RF, Hoff JT. Mechanisms of brain injury after intracerebral haemorrhage. Lancet Neurol. 2006;5:53–63. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(05)70283-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue M, Del Bigio MR. Intracerebral injection of autologous whole blood in rats: time course of inflammation and cell death. Neurosci Lett. 2000;283:230–2. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(00)00971-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue M, Del Bigio MR. Immune pre-activation exacerbates hemorrhagic brain injury in immature mouse brain. J Neuroimmunol. 2005;165:75–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2005.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang S, Nakamura T, Hua Y, Keep RF, Younger JG, He Y, Hoff JT, Xi G. The role of complement C3 in intracerebral hemorrhage-induced brain injury. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2006;26:1490–5. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]