Abstract

Objective

To determine whether HIV and HHV-8 infection are associated with pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH)

Background

Previous work has found a high prevalence of PAH in HIV-infected patients, but attempts to establish a causal relationship have been limited by the lack of a well-characterized contemporaneous HIV-uninfected comparison group. Among HIV-uninfected persons, human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8) has also been recently linked to PAH, but whether this relationship is present or exaggerated among HIV-infected persons — who have among the highest prevalences of HHV-8 infection — has not been examined.

Methods

We echocardiographically estimated pulmonary artery systolic pressure (PASP) among HIV-infected and -uninfected adults in San Francisco.

Results

Among the 196 HIV-infected participants, the median PASP was 27.5 mm Hg, and 35.2% had PASP > 30 mm Hg. This compared to a median of 22 mm Hg among 52 HIV-uninfected participants (p < 0.001) in whom 7.7% had a value > 30 (p < 0.001). After adjustment for injection drug use, stimulant use, smoking, age, and gender, HIV-infected participants had 5.1 mm Hg higher mean PASP (p < 0.001) and had 7.0-fold greater odds of having a PASP > 30 mm Hg (p < 0.001). While we found no evidence of an association between HHV-8 infection and PAH among all HIV-infected participants, a borderline relationship was present when restricting to those without other known risk factors for PAH.

Conclusions

HIV-infected persons have a high prevalence of elevated PASP, which is independent of other risk factors for PAH including injection drug use. This suggests a causal role of HIV in PAH and emphasizes the need to better understand the natural history of PAH in this setting. Evidence for a role for HHV-8 infection in PAH remains much less definitive.

Keywords: pulmonary hypertension, AIDS, HIV infection, human herpesvirus 8 infection

Introduction

With the advent of potent antiretroviral therapy, HIV-infected individuals are living longer and co-morbid conditions are becoming increasingly more important in influencing their survival. Among the less well characterized co-morbidities is pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH), a potentially life threatening disorder featuring increased pulmonary vascular resistance and progressive right ventricular failure (1,2). In the general population, the majority of PAH diagnoses are idiopathic, with a minority attributed to factors such as lung disease, left-sided or valvular heart disease, and injection drug use (3). For persons with HIV infection, the frequent presence of injection drug use is of obvious concern for increasing the prevalence of PAH, but HIV infection per se has also been purported as being causal (4–8). Recently, an etiologic role for another virus, human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8, also known as Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus) has been proposed (9), which is relevant to persons with HIV infection given their substantial prevalence of HHV-8 infection (10).

Although classification systems (3) and clinical practice guidelines (11,12) list HIV infection among the known causes of PAH, whether HIV infection is truly causal or can be explained by known risk factors such as injection drug use has not been established. For example, among case series reports of PAH among HIV-infected patients, several had a substantial percentage of individuals with a documented history of injection drug use (5,13), and none had a concurrent comparator group of HIV-uninfected individuals. Whether HHV-8 is a cause of PAH is also not clear. Following the initial report describing an association (9), other studies have not confirmed this finding (14–19).

To overcome prior limitations in the investigation of the role of HIV in PAH, we studied the prevalence of PAH as assessed by echocardiography in a large unselected sample of HIV-infected adults along with a well-characterized contemporaneous HIV-uninfected comparator group. We sought to evaluate if HIV infection is associated with the occurrence of PAH independent of other known risks – especially injection drug use – and, if so, what are the determinants of PAH among HIV-infected persons. In particular, we took advantage of the high prevalence of HHV-8 infection in HIV-infected persons to evaluate the role of HHV-8 infection in PAH.

Methods

Participants

HIV-infected participants were recruited from an ongoing clinic-based cohort, the Study of the Consequences of the Protease inhibitor Era (SCOPE), based at San Francisco General Hospital and the San Francisco Veterans Affairs Medical Center. Participants in our echocardiographic substudy were consecutive volunteers who responded to an information sheet given to all SCOPE participants; there were no exclusion criteria. HIV-uninfected participants were persons who answered advertisements (e.g.., flyers posted in the medical center, advertisements posted on the internet) directed towards persons believed to HIV-uninfected to enroll in clinical research studies. All persons in this group were tested and documented as HIV-antibody-negative; there were no other eligibility criteria. All participants provided written informed consent.

Measurements

Clinical and sociodemographic characteristics

All participants underwent a structured interview addressing sociodemographic characteristics, known prior diagnoses of PAH, behavioral factors even distantly associated with PAH, and activity tolerance using the New York Heart Association classification. Questions concerning injection drug use and use of stimulants by any route, specifically cocaine and amphetamine/methamphetamine, were asked with confidential self-administered instruments. The HIV-infected participants had a comprehensive assessment of aspects related to their HIV disease (e.g., antiretroviral therapy) as part of the parent SCOPE cohort.

Echocardiography

Participants were examined in the supine position by a sonographer (SP) who was blinded to their clinical characteristics and HIV infection status. Using a Vivid Seven Imaging System (GE, Milwaukee, WI), tricuspid regurgitation was assessed in the parasternal right ventricular inflow, parasternal short-axis, and apical four-chamber views; 3 sequential complexes were recorded. Continuous-wave Doppler measurement of peak regurgitant jet velocity was used to estimate the pressure gradient between the right ventricle and the right atrium using the modified Bernoulli equation (20). Pulmonary artery systolic pressure (PASP) was quantified by adding the calculated pressure gradient to the mean right atrial pressure, which was estimated using standard echocardiographic methods (21). In participants who had trace or no tricuspid regurgitation, we made the assumption that PASP was normal, as most persons who have clinically significant pulmonary hypertension have measurable tricuspid regurgitation (22). To assess for elevated left-sided heart filling pressures as a cause of elevated PASP, we determined the presence of diastolic dysfunction according to guidelines from the American Society of Echocardiography (ASE) (23–25). Mitral regurgitation was assessed using standard criteria (26). Finally, we also assessed for the presence of congenital heart disease. All calculations and interpretations were performed off-line by a single level 3 ASE-certified cardiologist (HHF) who was blinded to participants’ clinical and HIV infection status.

Antibodies to HHV-8

Two enzyme-linked immunoassays (EIAs) and one immunofluorescence assay (IFA), both performed at the Centers of Disease Control and Prevention, were used to determine HHV-8 antibody status. In the EIA, synthetic peptides from the HHV-8 open reading frame (ORF) 65-encoded viral capsid protein (27) and the ORF K8.1-encoded viral envelope protein (28) are used as the target antigens in separate assays. In the IFA, HHV-8-containing BCBL-1 cells, in which HHV-8 is induced to lytic replication (29), are used as antigen substrate. Specimens reactive in the IFA (regardless of reactivity in the EIAs) or in both of the EIAs were deemed seropositive for HHV-8 (30). HHV-8 antibody determination was performed only among the HIV-infected participants.

Other laboratory assays

Plasma HIV RNA levels were determined by the branched DNA (bDNA) amplification technique (Quantiplex® HIV RNA, version 3.0, Chiron Corporation, Emeryville, CA). Hepatitis C virus (HCV) serostatus was determined by the HCV EIA version 2.0 (Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL). CD4+ T cell counts were measured at the respective clinical laboratories associated with each of the SCOPE cohort clinic sites. The nadir CD4+ T cell count was the lowest laboratory-confirmed value prior to the echocardiography date.

Statistical analyses

In both the analysis investigating the role of HIV in PAH and the analysis of HHV-8 in determining PAH among the HIV-infected participants, we used a two-stage approach to subject selection. In the first approach, all relevant participants were included and multivariable regression techniques were used to assess independent contribution of relevant variables. In the second approach, as another method to minimize confounding, we restricted the sample by excluding those who ever used injection drugs, were HCV antibody-positive (as a further method to exclude injection drug use), ever smoked (as a surrogate for lung disease), had grade II or higher diastolic dysfunction or 3+ or greater mitral regurgitation (to exclude those with high filling pressures of the left ventricle which could cause PAH), or who had congenital heart disease. This restriction approach is particularly useful for factors, such as injection drug use, where the never-used state is easily define, but the degree of exposure among users is difficult to quantitate. A further restricted sample also excluded participants who ever used cocaine or amphetamine/methamphetamine by any route, as use of stimulant agents have been linked to PAH (31). In all analyses, PASP was evaluated both in its native continuous form and dichotomized at ≤ 30 versus > 30 mm Hg. The value of 30 mm Hg was chosen because a similar cut-point was used to define PAH in an unselected group of patients with sickle cell disease, where values above this cut-point were determined to confer substantial mortality risk (32). Linear regression was used to evaluate factors associated with the continuous measure of PASP, and logistic regression used for the dichotomized variable. In the multivariable regression analyses evaluating the role of HIV in PAH, all potential confounding variables were included in the final model in addition to HIV (the primary predictor variable); the same approach was used in the multivariable linear regression of the role of HHV-8 in PAH among the HIV-infected participants. In the multivariable logistic regression analysis of HHV-8 among the HIV-infected participants, because the number of potential confounding factors was large relative to the number of events and including all of them could threaten model validity, we limited inclusion to variables that were associated with PASP at a p value of < 0.20 in unadjusted analyses. All linear regression analyses employed robust variance estimation, and all logistic regression analyses had goodness-of-fit assessed by the Hosmer-Lemeshow test.

Results

Participant characteristics

A total of 196 HIV-infected and 52 HIV-uninfected participants were evaluated (Table 1). The median age was 47 years in the HIV-infected group and 45 in the -uninfected group; over 80% of participants in both groups were men. Caucasian race was most common in both groups, and the HIV-infected group had a higher percentage of African-Americans. Among the HIV-infected participants, 62% had never used injection drugs, 32% had used in the past, and 6.1% were current users; one (1.9%) of the HIV-uninfected participants had used injection drugs in the past. Smoking was common in both groups. Among the HIV-infected participants, the median duration of HIV infection was 15 years and the majority (82%) was currently using antiretroviral medication. The median CD4+ T cell count was 420 cells/mm3, and the median plasma HIV RNA level was < 75 copies/ml. Over half (58%) of the HIV-infected group was HHV-8-antibody-positive.

Table 1.

Characteristics of HIV-infected and -uninfected participants

| Characteristic | HIV-Infected (N=196) |

HIV-Uninfected (N=52) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years, median (IQR) | 47 (42 to 52) | 45 (40 to 56) | |

| Gender, % | |||

| Male | 83 | 88 | |

| Female | 15 | 12 | |

| Transgender | 2.0 | 0 | |

| Race, % | |||

| Caucasian | 54 | 67 | |

| African American | 25 | 7.7 | |

| Hispanic | 10 | 9.6 | |

| Other | 11 | 15 | |

| Injection drug use, % | |||

| Never | 62 | 98 | |

| Ever but not current | 32 | 1.9 | |

| Current | 6.1 | 0 | |

| Stimulant use,* % | |||

| Never | 54 | 83 | |

| Ever | 46 | 17 | |

| Smoking, % | |||

| Never | 34 | 35 | |

| Ever but not current | 31 | 40 | |

| Current | 35 | 25 | |

| Duration of HIV infection (self-report) in years, median (IQR) | 15 (11 to 18) | -- | |

| Use of antiretroviral medication, % | |||

| Never | 8.0 | -- | |

| Ever but not current | 11 | ||

| Current | 82 | ||

| NRTI† use duration in years, median (IQR) | 7.9 (3.9 to 10) | -- | |

| NNRTI† use duration in years, median (IQR) | 0.29 (0 to 3.4) | -- | |

| PI† use duration in years, median (IQR) | 5.3 (0.96 to 7.7) | -- | |

| CD4+ T cells/mm3, median (IQR) | 420 (231 to 634) | -- | |

| Nadir CD4+ T cells/mm3, median (IQR) | 120 (40 to 232) | -- | |

| Plasma HIV RNA copies/ml, % | |||

| < 75 | 63 | ||

| 76 to 1000 | 15 | -- | |

| 1001 to 10,000 | 9.2 | ||

| > 10,000 | 13 | ||

| HHV-8‡ antibody-seropositivity, % | 58 | -- | |

Cocaine and/or amphetamine/methamphetamine use

Denotes nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor, non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor, and protease inhibitor, respectively

Denotes human herpesvirus 8

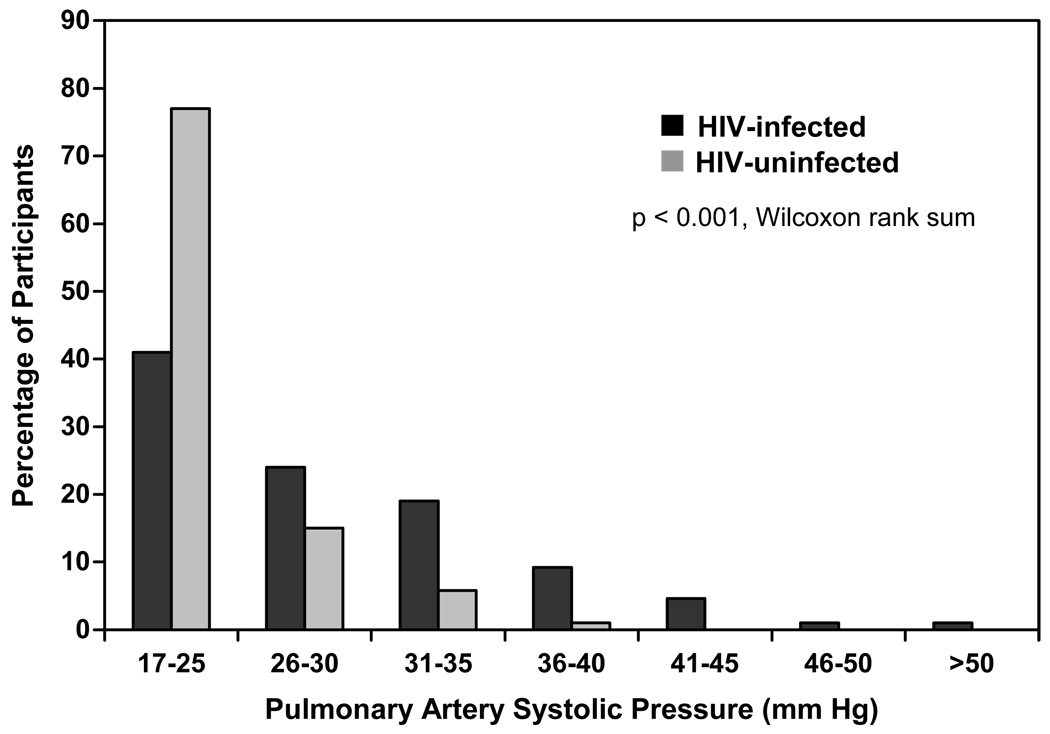

Distribution of PASP

The median PASP among the HIV-infected participants was 27.5 mm Hg (interquartile range [IQR] 22 to 32.5) compared to 22 mm Hg (IQR 18 to 25) among the HIV-uninfected participants (p < 0.001, Wilcoxon rank sum) (Figure 1). Among the HIV-infected group, 35.2% (95% confidence interval [CI] 28.5 to 42.3%) had PASP > 30 mm Hg, 15.8% > 35 and 6.6% > 40 mm Hg. In contrast, only 7.7% of the HIV-uninfected participants had a PASP > 30 (p < 0.001 vs. HIV-infected group) and only one subject (1.9%) had a value above 35 (p = 0.005). To assess the prevalence of elevated PASP among those HIV-infected persons without known predilection for PAH, we excluded those who ever used injection drugs or stimulants, were HCV antibody-positive, ever smoked, had evidence of grade II or higher diastolic dysfunction (only 2 participants), had severe (3+ or greater) mitral regurgitation (no participants) or who had congenital heart disease (no participants). In the 49 HIV-infected participants who remained, the prevalence of elevated PASP was still high. The median PASP was 28 mm Hg (IQR 19 to 33); 36.1% had PASP > 30 mm Hg, 14.8% > 35, and 6.7 % > 40. Despite the high prevalence of elevated PASP among the HIV-infected participants, only 7 (3.6%) experienced class II or higher New York Heart Association activity tolerance (all were class II), and there was no evidence of an association with PASP (p = 0.61).

Figure 1.

Distribution of pulmonary arterial systolic pressure in HIV-infected and -uninfected participants

Association between HIV infection and elevated PASP

After adjusting for age, gender, race, smoking, injection drug use, and stimulant use, HIV-infected participants had 5.1 mm Hg higher mean PASP (95% CI 3.1 to 7.0, p < 0.001) and 7.0-fold greater odds of having PASP > 30 (95% CI 2.3 to 21, p < 0.001) (Tables 2 and 3). Among the other variables examined, only age had a significant association with PASP. After restricting to the subset of participants without history of injection drug use, HCV antibody-positivity, smoking, or grade II or higher diastolic dysfunction, the magnitude of the associations somewhat increased. In this subset of 65 individuals, HIV-infected participants had an age and gender-adjusted 6.1 mm Hg higher mean PASP than HIV-uninfected participants (95% CI 2.6 to 9.6, p = 0.001) and had a 15-fold greater odds of having PASP > 30 (95% CI 1.5 to 141, p = 0.021). Further exclusion of all participants with a history of stimulant use resulted in essentially unchanged significant associations between HIV and PASP (data not shown).

Table 2.

Unadjusted and adjusted analysis of factors associated with pulmonary artery systolic pressure (PASP)

| Characteristic | Unadjusted |

Adjusted† |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean difference in PASP, in mm/Hg (95% CI)* |

P value |

Mean difference in PASP, in mm/Hg (95% CI)* |

P value |

||

| HIV status | |||||

| Uninfected | reference | reference | |||

| Infected | 5.6 (3.7 to 7.4) | < 0.001 | 5.1 (3.1 to 7.0) | < 0.001 | |

| Age, per 1 year change | 0.10 (−0.021 to 0.22) | 0.11 | 0.13 (0.0048 to 0.25) | 0.042 | |

| Race | |||||

| Caucasian | reference | reference | |||

| Non-Caucasian | 2.1 (−0.17 to 4.3) | 0.070 | 1.8 (−0.44 to 4.0) | 0.12 | |

| Gender | |||||

| Men | reference | reference | |||

| Women | 2.9 (−0.63 to 6.4) | 0.11 | 2.4 (−1.3 to 6.1) | 0.20 | |

| Smoking | |||||

| Never | reference | reference | |||

| Ever but not current | 2.2 (−0.41 to 4.9) | 0.098 | 2.1 (−0.26 to 4.4) | 0.081 | |

| Current | 0.32 (−2.0 to 2.7) | 0.79 | −0.95 (−3.4 to 1.5) | 0.44 | |

| Injection drug use | |||||

| Never | reference | reference | |||

| Ever but not current | 2.7 (−0.27 to 5.6) | 0.076 | 0.56 (−2.3 to 3.5) | 0.70 | |

| Current | 4.0 (−2.0 to 10) | 0.19 | 4.1 (−1.8 to 10) | 0.17 | |

| Stimulant use‡ | |||||

| Never | reference | reference | |||

| Ever | 1.3 (−1.0 to 3.5) | 0.28 | −0.047 (−2.3 to 2.3) | 0.97 | |

Mean difference was derived in a linear regression model. CI denotes confidence interval.

All variables are adjusted for all other variables in the column.

Cocaine and/or amphetamine/methamphetamine use

Table 3.

Unadjusted and adjusted analysis of factors associated with pulmonary artery systolic pressure (PASP) greater than 30 mm Hg

| Characteristic | N | Percent with PASP > 30 mm Hg |

Unadjusted |

Adjusted† |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratio (95% CI)* |

P value |

Odds Ratio (95% CI)* |

P value |

||||

| HIV status | |||||||

| Uninfected | 52 | 7.7 | reference | reference | |||

| Infected | 196 | 35 | 6.5 (2.3 to 19) | 0.001 | 7.0 (2.3 to 21) | < 0.001 | |

| Age, per 1 year change | 248 | -- | 1.03 (1.0 to 1.1) | 0.049 | 1.0 (1.0 to 1.1) | 0.042 | |

| Race | |||||||

| Caucasian | 140 | 29 | reference | reference | |||

| Non-Caucasian | 108 | 31 | 1.1 (0.64 to 1.9) | 0.73 | 1.0 (0.53 to 1.9) | 0.99 | |

| Gender | |||||||

| Men | 210 | 28 | reference | reference | |||

| Women | 38 | 39 | 1.7 (0.83 to 3.5) | 0.14 | 2.0 (0.88 to 4.4) | 0.099 | |

| Smoking | |||||||

| Never | 85 | 27 | reference | reference | |||

| Ever but not current | 82 | 34 | 1.4 (0.72 to 2.7) | 0.32 | 1.4 (0.69 to 2.9) | 0.34 | |

| Current | 81 | 27 | 1.0 (0.51 to 2.0) | 0.98 | 0.83 (0.38 to 1.8) | 0.64 | |

| Injection drug use | |||||||

| Never | 172 | 26 | reference | reference | |||

| Ever but not current | 64 | 38 | 1.7 (0.95 to 3.2) | 0.074 | 1.2(0.59 to 2.3) | 0.64 | |

| Current | 12 | 42 | 2.1 (0.63 to 6.9) | 0.23 | 2.3(0.61 to 9.0) | 0.22 | |

| Stimulant use | |||||||

| Never | 149 | 30 | reference | reference | |||

| Ever | 99 | 29 | 0.99 (0.57 to 1.7) | 0.97 | 0.73 (0.39 to 1.3) | 0.31 | |

Odds ratio was derived in a logistic regression model. CI denotes confidence interval.

All variables are adjusted for all other variables in the column.

Cocaine and/or amphetamine/methamphetamine use

Association between HHV-8 infection and elevated PASP among HIV-infected persons

When assessing all HIV-infected participants, we found no evidence of an association between HHV-8 infection and PASP. Specifically, in unadjusted analyses, HHV-8 infected participants had 0.39 mm Hg lower mean PASP than HHV-8-uninfected participants (95% CI −3.2 to 2.4, p = 0.78) and had only 1.2-fold greater odds of PASP > 30 mm Hg (95% CI 0.67 to 2.3, p =0.51). After adjusting for age, gender, HCV infection, and a variety of HIV-related parameters, inferences were unchanged, still indicating no association between HHV-8 infection and PASP (data not shown). Following the same strategy we pursued in the analysis of the role of HIV in PAH, we then restricted the sample to persons without prior injection drug use, HCV antibody-positivity, smoking, or grade II or higher diastolic dysfunction. Among the 47 individuals that remained, those with HHV-8 infection had an age-and gender-adjusted 4.6 mm Hg higher mean PASP than HHV-8-uninfected participants (95% CI −0.11 to 9.2, p = 0.056). The much greater difference in mean PASP between HHV-8-infected and -uninfected participants in this subgroup compared to the entire group of 196 HIV-infected individuals suggested that the presence of injection drug use, HCV infection, or smoking was modifying the effect of HHV-8 infection on PASP. Indeed, the p value for the interaction term testing for this was 0.028 (Table 4). To assess the robustness of the association between HHV-8 and PASP that we observed in these 47 individuals, we created other restricted subgroups among the HIV-infected participants. We found that any group that excluded HCV-infected persons resulted in the same statistically borderline association between HHV-8 infection and PASP. Performing the same restriction and assessing PASP as a dichotomous variable again revealed a qualitatively different role of HHV-8, but this did not reach statistical significance (2.8-fold greater odds of PASP > 30 mm Hg among HHV-8-infected participants; 95% CI 0.69 to 11, p = 0.15).

Table 4.

Effect of HHV-8 infection on pulmonary artery systolic pressure (PASP) in different subgroups of participants

| Participant Subgroup | N | Mean difference in PASP, in mm/Hg, between HHV-8-infected and uninfected participants (95% CI)* |

P value | P value for interaction † |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-smokers | 67 | 2.0 (−1.7 to 5.7) | 0.29 | 0.16 |

| Non-IDU‡ | 117 | 1.6 (−1.2 to 4.4) | 0.26 | 0.13 |

| HCV-uninfected | 132 | 2.6 (−0.062 to 5.2) | 0.056 | 0.005 |

| Non-IDU and HCV§-uninfected | 99 | 3.2 (0.040 to 6.3) | 0.047 | 0.008 |

| Non-stimulant∥ users | 101 | 0.016 (−2.9 to 2.9) | 0.99 | 0.89 |

| Non-smokers, Non-IDU, HCV-uninfected, and no diastolic dysfunction | 47 | 4.6 (−0.11 to 9.2) | 0.056 | 0.028 |

| Non-smokers, Non-IDU, HCV-uninfected, non-stimulant users and no diastolic dysfunction | 32 | 5.5 (−0.68 to 12) | 0.079 | 0.11 |

Adjusted by age and gender, as derived by multivariable linear regression. CI denotes confidence interval.

Denotes p value for interaction term evaluating whether effect of HHV-8 differs between participants in the listed subgroup versus all other participants

Denotes injection drug user

Denotes hepatitis C virus

Cocaine and/or amphetamine/methamphetamine use

Other factors associated with elevated PASP among HIV-infected persons

When evaluating PASP as either a continuous or dichotomous variable, there was no strong evidence for a role of age, gender, race, stimulant use, smoking, duration of HIV infection, duration of use of any class of antiretroviral drugs, current or nadir CD4+ T cell count, or current plasma HIV RNA level. Among the strongest associations was that for HCV infection (a surrogate of injection drug use), but this did not reach levels of conventional statistical significance (p = 0.093).

Discussion

Although HIV infection is listed amongst the causes of PAH in widely used classification systems (3) and testing for HIV has been incorporated into practice guidelines for persons with PAH (11,12), a closer look at the prior evidence for a causal role of HIV reveals deficiencies. The foremost deficiency relates to the fact that persons with HIV infection commonly have a history of injection drug use, which itself is associated with PAH (3). Hence, simply finding a high frequency of PAH among HIV-infected persons, without accounting for injection drug use or having a concurrent comparator group of HIV-uninfected persons, is insufficient evidence. The two cases series that are most widely cited as establishing a high frequency of PAH in HIV disease indeed had among their cases many patients with concomitant history of injection drug use (5,13). Even examining the most recent comprehensive review (through 1998) finds that among the 76 HIV-infected persons with PAH and no other apparent known cause, 51.3% had a history of injection drug use, leaving only 37 cases without such drug use history (33). In the only comparative study we are aware of that directly contained both HIV-infected and -uninfected individuals (34), HIV infection was found in 3 persons with PAH and not found among controls without PAH, but it was unclear if this difference held true after adjustment for injection drug use.

To overcome limitations in the prior evidence to establish a causal role of HIV in PAH, we first included a group of well characterized contemporaneous HIV-uninfected persons to serve as a direct comparator group. Second, we assessed the critical confounding factor of injection drug use by prospective measurement (confidential self-administered questionnaire), and we used a biological proxy, presence of antibodies to HCV, to enhance sensitivity. Furthermore, we probed for the use of stimulants (i.e., cocaine or amphetamine/methamphetamine) via non-parenteral routes, thereby providing comprehensive measurement of the main recreational agents that have been associated with PAH. Third, to overcome limitations in finding sufficient numbers of patients with clinically manifest PAH, we focused on measuring PASP in an unselected group of HIV-infected patients, regardless of current symptoms. What we observed is a substantially higher than expected prevalence of elevated PASP among HIV-infected persons that was many times greater than HIV-uninfected individuals. This finding is independent of injection drug use and use of stimulants, as well as age, gender, and smoking. Taking our design features into account, we believe these data are among the strongest to date for a causal role of HIV in PAH.

It is important to emphasize that our participants were not selected on the basis of symptoms. Therefore, it is most appropriate to describe the high prevalence of elevated PASP we have identified as “pre-clinical” PAH and note that it is different from previous reports in HIV-infected persons that have focused on clinically manifest PAH. The high prevalence of elevated PASP that we have found is substantiated by an earlier echocardiographic study among HIV-infected patients which found a high and unexplained prevalence of isolated right ventricular enlargement (35). More recently, other ongoing work with echocardiography in unselected HIV-infected individuals has also preliminarily found high prevalences of elevated PASP (36,37).

Because what we have identified is “pre-clinical” PAH, it is not known if most affected individuals will develop symptomatic disease. Because the prevalence of clinically manifest PAH among HIV-infected patients is substantially lower than what we have observed for “pre-clinical” PAH, we do not believe that most individuals will develop symptoms. However, what is of concern is whether any important fraction of these individuals will experience sudden death. This is relevant because in the investigation of PAH among an unselected group of patients with sickle cell anemia, of the 32% who had PASP ≥ 30 mm Hg, mortality was 17.5% at 17 months of follow-up (32). Approximately 50% of those patients who died did so of sudden death, some of whom having not developed classic symptoms of PAH (Mark Gladwin, personal communication). Therefore, it is possible that undiagnosed PAH is currently an important cause of death among HIV-infected persons. Some evidence for this was seen in a recently completed large treatment strategy trial in HIV-infected adults where the number of unexplained deaths was similar in magnitude to the number of deaths due to cardiovascular disease (38). Since it is conceivable that at least some of these unexplained deaths were due to sudden death related to undiagnosed PAH, it is imperative that we now definitively determine the natural history of “pre-clinical” PAH among HIV-infected persons.

If HIV is causally related to PAH, by what biologic mechanism does this operate? Attempts to locate evidence of HIV infection in diseased lung tissue of patients with PAH either by electron microscopy, immunohistochemistry, or nucleic acid amplification have been unsuccessful (39). More recently, investigation has focused on a potential indirect role of HIV that may be mediated through vascular endothelial growth factor-A, platelet derived growth factor, endothelin-1, transforming growth factor beta, interleukin-6, and HIV Nef (40–44). Our inability to relate specific HIV-related parameters (e.g., plasma HIV RNA level, CD4+ T cell count, or use of antiretroviral therapy) to PAH unfortunately does not add to the understanding of pathogenesis. We do note that one factor that is likely invariably higher among HIV-infected individuals is generalized T cell activation, a process that is increasingly implicated in the immunopathogenesis of HIV (45). Although we did not measure generalized T cell activation in our participants, we note that levels are likely high even among those HIV-infected patients who are being treated with antiretroviral medication (46). The role of inflammation and immune activation in precipitating cardiovascular disease was recently suggested by the increase in cardiovascular events in HIV-infected patients on intermittent antiretroviral therapy as compared to continuous therapy in the SMART study (47).

We evaluated the role of HHV-8 infection in PAH in an attempt to confirm a prior report in which HIV-uninfected patients with primary pulmonary hypertension were found to have evidence of HHV-8 in their lungs by immunohistochemistry and nucleic acid amplification (9). This study has been followed by seven others refuting the finding (14–19), and one report that detected HHV-8 by immunohistochemistry but not by nucleic acid amplification (48). Importantly, our study design differed from prior work in that by concentrating on HIV-infected participants, we were assured to study a large number of HHV-8-infected persons. This avoids criticisms of prior work in which even if HHV-8 was truly a sufficient (but not necessary) cause of PAH, an association could be very difficult to detect in a population with very low overall HHV-8 prevalence. In addition, by focusing on HIV-infected persons, where other overt HHV-8-related disease manifestations such as Kaposi’s sarcoma occur, we theorized we would optimize our ability to observe PAH. With one of the largest sample sizes to date to study HHV-8 in PAH, we did not detect an association when evaluating all HIV-infected participants but did find some evidence when restricting to persons without HCV infection. Although the association we found occurred in a pre-specified subgroup, the effect is of borderline statistical significance, and we cannot readily provide a biologic explanation as to why the effect of HHV-8 would be stronger in HCV-uninfected persons. Furthermore, the epidemiology of HHV-8 infection would not predict that it is a culprit in PAH. Specifically, there is no evidence of increased incidence of PAH in homosexual men in the U.S. or persons residing in the Mediterranean, two groups with the highest prevalence of HHV-8 who live in developed settings where PAH would be expected to be diagnosed if it occurred. Therefore, considering the entirety of the literature to date, we believe that the evidence for a role of HHV-8 in PAH is far less definitive than that of HIV and still must be considered suspect. Yet, before the idea is discarded, it would seem necessary for others to repeat our approach of evaluating large numbers of HHV-8-infected persons (with and without HCV infection) to confirm or refute our findings.

There are potential limitations to our work. Without performing right heart catheterization to confirm all instances of elevated PASP, we recognize our estimate of the absolute prevalence of elevated PAH could be biased. Yet, even if the absolute estimates are biased in either direction, because our measurement of PASP was blinded to participants’ HIV infection status, any misclassification is non-differential. Therefore, the relative difference in PAH between HIV-infected and -uninfected groups should be unaffected. In terms of ruling out confounding as an explanation for the apparent association between HIV and PAH, we recognize that, in the absence of systematic radiologic imaging and biochemical investigation, we did not have a sensitive measurement of chronic liver disease and portal hypertension, which are believed to be causally linked to PAH (49). We did, however, observe a robust relationship between HIV and PAH even after excluding persons with HCV infection, by far the most common cause of liver disease in this population. What is potentially more significant is the presence of unknown confounding factors. That primary (or idiopathic) pulmonary hypertension remains such an important diagnostic entity among all persons with PAH indicates that the etiologic factors responsible for PAH are largely unknown. It thus remains conceivable that some of these factors — especially if behaviorally acquired — could be more prevalent among HIV-infected persons, and we may not have adjusted for these.

Because the clinical implications of “pre-clinical” PAH amongst HIV-infected persons are not known, it is premature to suggest that routine screening should be performed to detect this condition. However, because of the importance of asymptomatic elevated PASP in other patient groups (e.g., sickle cell anemia) there is now urgency in both confirming our estimates of the high prevalence of this condition in HIV-infected persons and determining the clinical outcomes in these patients. A better understanding of the pathogenesis of HIV-related PAH is also needed in that this may both help shape future paradigms in HIV care (e.g., perhaps towards diminishing levels of certain inflammatory cytokines that remain elevated even among antiretroviral-treated patients with undetectable plasma HIV RNA levels) and unlock many of the longstanding uncertainties about the pathogenesis of primary PAH.

Acknowledgments

We thank Henry Masur, MD, and Mark T. Gladwin, MD for their helpful suggestions.

Funding Sources: The work was supported by grants from the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation (Clinical Scientist Development Award to PYH), the American Heart Association (Beginning Grant-in-Aid to PYH), the NIH (R01 AI052745, R01 CA119903, P30 AI27763 and MO1 RR000083) and the University of California AIDS Research Program California AIDS Research Center (CC99-SF-001).

Abbreviations

- HIV

human immunodeficiency virus

- HHV-8

human herpesvirus 8

- PAH

pulmonary arterial hypertension

- PASP

pulmonary artery systolic pressure

Footnotes

Presented in part at the 78th Scientific Sessions of the American Heart Association, Dallas, TX, November 12–15, 2005 and at the 13th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, Denver, CO February 5–8, 2006.

Disclosures: Dr. Hsue reports that she has received a grant award from Actelion.

Conflicts of interest: None

References

- 1.Farber HW, Loscalzo J. Pulmonary arterial hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1655–1665. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra035488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Humbert M, Sitbon O, Simonneau G. Treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1425–1436. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra040291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Simonneau G, Galie N, Rubin LJ, et al. Clinical classification of pulmonary hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:5S–12S. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.02.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mehta NJ, Khan IA, Mehta RN, Sepkowitz DA. HIV-Related pulmonary hypertension: analytic review of 131 cases. Chest. 2000;118:1133–1141. doi: 10.1378/chest.118.4.1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Speich R, Jenni R, Opravil M, Pfab M, Russi EW. Primary pulmonary hypertension in HIV infection. Chest. 1991;100:1268–1271. doi: 10.1378/chest.100.5.1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Petitpretz P, Brenot F, Azarian R, et al. Pulmonary hypertension in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Comparison with primary pulmonary hypertension. Circulation. 1994;89:2722–2727. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.89.6.2722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Opravil M, Pechere M, Speich R, et al. HIV-associated primary pulmonary hypertension. A case control study. Swiss HIV Cohort Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;155:990–995. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.155.3.9117037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mesa RA, Edell ES, Dunn WF, Edwards WD. Human immunodeficiency virus infection and pulmonary hypertension: two new cases and a review of 86 reported cases. Mayo Clin Proc. 1998;73:37–45. doi: 10.1016/S0025-6196(11)63616-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cool CD, Rai PR, Yeager ME, et al. Expression of human herpesvirus 8 in primary pulmonary hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1113–1122. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa035115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martin JN, Ganem DE, Osmond DH, Page-Shafer KA, Macrae D, Kedes DH. Sexual transmission and the natural history of human herpesvirus 8 infection. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:948–954. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199804023381403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barst RJ, McGoon M, Torbicki A, et al. Diagnosis and differential assessment of pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:40S–47S. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McGoon M, Gutterman D, Steen V, et al. Screening, early detection, and diagnosis of pulmonary arterial hypertension: ACCP evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2004;126:14S–34S. doi: 10.1378/chest.126.1_suppl.14S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Himelman RB, Dohrmann M, Goodman P, et al. Severe pulmonary hypertension and cor pulmonale in the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Am J Cardiol. 1989;64:1396–1399. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(89)90594-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Henke-Gendo C, Schulz TF, Hoeper MM. HHV-8 in pulmonary hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:194–195. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200401083500221. author reply 194-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Laney AS, De Marco T, Peters JS, et al. Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus and primary and secondary pulmonary hypertension. Chest. 2005;127:762–767. doi: 10.1378/chest.127.3.762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Montani D, Marcelin AG, Sitbon O, Calvez V, Simonneau G, Humbert M. Human herpes virus 8 in HIV and non-HIV infected patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension in France. Aids. 2005;19:1239–1240. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000176230.94226.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Daibata M, Miyoshi I, Taguchi H, et al. Absence of human herpesvirus 8 in lung tissues from Japanese patients with primary pulmonary hypertension. Respir Med. 2004;98:1231–1232. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2004.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Katano H, Ito K, Shibuya K, Saji T, Sato Y, Sata T. Lack of human herpesvirus 8 infection in lungs of Japanese patients with primary pulmonary hypertension. J Infect Dis. 2005;191:743–745. doi: 10.1086/427824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nicastri E, Vizza CD, Carletti F, et al. Human herpesvirus 8 and pulmonary hypertension. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11:1480–1482. doi: 10.3201/eid1109.040880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Berger M, Haimowitz A, Van Tosh A, Berdoff RL, Goldberg E. Quantitative assessment of pulmonary hypertension in patients with tricuspid regurgitation using continuous wave Doppler ultrasound. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1985;6:359–365. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(85)80172-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kircher BJ, Himelman RB, Schiller NB. Noninvasive estimation of right atrial pressure from the inspiratory collapse of the inferior vena cava. Am J Cardiol. 1990;66:493–496. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(90)90711-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Borgeson DD, Seward JB, Miller FA, Jr, Oh JK, Tajik AJ. Frequency of Doppler measurable pulmonary artery pressures. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 1996;9:832–837. doi: 10.1016/s0894-7317(96)90475-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gibson DG, Francis DP. Clinical assessment of left ventricular diastolic function. Heart. 2003;89:231–238. doi: 10.1136/heart.89.2.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zile MR, Brutsaert DL. New concepts in diastolic dysfunction and diastolic heart failure: Part I: diagnosis, prognosis, and measurements of diastolic function. Circulation. 2002;105:1387–1393. doi: 10.1161/hc1102.105289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rakowski H, Appleton C, Chan KL, et al. Canadian consensus recommendations for the measurement and reporting of diastolic dysfunction by echocardiography: from the Investigators of Consensus on Diastolic Dysfunction by Echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 1996;9:736–760. doi: 10.1016/s0894-7317(96)90076-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Blanchard D, Diebold B, Peronneau P, et al. Non-invasive diagnosis of mitral regurgitation by Doppler echocardiography. Br Heart J. 1981;45:589–593. doi: 10.1136/hrt.45.5.589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pau CP, Lam LL, Spira TJ, et al. Mapping and serodiagnostic application of a dominant epitope within the human herpesvirus 8 ORF 65-encoded protein. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:1574–1577. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.6.1574-1577.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spira TJ, Lam L, Dollard SC, et al. Comparison of serologic assays and PCR for diagnosis of human herpesvirus 8 infection. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:2174–2180. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.6.2174-2180.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lennette ET, Blackbourn DJ, Levy JA. Antibodies to human herpesvirus type 8 in the general population and in Kaposi's sarcoma patients. Lancet. 1996;348:858–861. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)03240-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Martro E, Bulterys M, Stewart JA, et al. Comparison of human herpesvirus 8 and Epstein-Barr virus seropositivity among children in areas endemic and non-endemic for Kaposi's sarcoma. J Med Virol. 2004;72:126–131. doi: 10.1002/jmv.10548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chin KM, Channick RN, Rubin LJ. Is methamphetamine use associated with idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension? Chest. 2006;130:1657–1663. doi: 10.1378/chest.130.6.1657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gladwin MT, Sachdev V, Jison ML, et al. Pulmonary hypertension as a risk factor for death in patients with sickle cell disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:886–895. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa035477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pellicelli AM, Barbaro G, Palmieri F, et al. Primary pulmonary hypertension in HIV patients: a systematic review. Angiology. 2001;52:31–41. doi: 10.1177/000331970105200105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Abenhaim L, Moride Y, Brenot F, et al. Appetite-suppressant drugs and the risk of primary pulmonary hypertension. International Primary Pulmonary Hypertension Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:609–616. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199608293350901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Blanchard DG, Hagenhoff C, Chow LC, McCann HA, Dittrich HC. Reversibility of cardiac abnormalities in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected individuals: a serial echocardiographic study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1991;17:1270–1276. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(10)80134-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Barnett CFAN, Bishop MR, Barrett AJ, Gladwin MT, Machado RF. Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension in HIV Infection and Stem Cell Transplant: Screening Identifies High Prevalence of "Pre-Disease". San Diego, CA. presented at the American Thoracic Society; 2006. Poster #829. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rosenkranz SSH, Vogel D, Werner M, Wyen C, Lehmann C, Schmeiber N, Fatkenheur G. HIV-associated Pulmonary Hypertension in Patients on HAART. Denver CO. presented at the 13th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; 2006. Poster #874. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Phillips ACA, Neuhaus J, Visnegarwala F, Prineas R, Burman W, Williams I, Drummond F, Duprez D, Lundgren J others for the SMART Study Group. Interruption of ART and Risk of Cardiovascular Disease: Findings from SMART. Los Angeles, CA. presented at the 14th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; 2007. Feb, Abstract #41. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mette SA, Palevsky HI, Pietra GG, et al. Primary pulmonary hypertension in association with human immunodeficiency virus infection. A possible viral etiology for some forms of hypertensive pulmonary arteriopathy. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1992;145:1196–1200. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/145.5.1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Humbert M, Monti G, Fartoukh M, et al. Platelet-derived growth factor expression in primary pulmonary hypertension: comparison of HIV seropositive and HIV seronegative patients. Eur Respir J. 1998;11:554–559. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ascherl G, Hohenadl C, Schatz O, et al. Infection with human immunodeficiency virus-1 increases expression of vascular endothelial cell growth factor in T cells: implications for acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-associated vasculopathy. Blood. 1999;93:4232–4241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ehrenreich H, Rieckmann P, Sinowatz F, et al. Potent stimulation of monocytic endothelin-1 production by HIV-1 glycoprotein 120. J Immunol. 1993;150:4601–4609. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hofman FM, Wright AD, Dohadwala MM, Wong-Staal F, Walker SM. Exogenous tat protein activates human endothelial cells. Blood. 1993;82:2774–2780. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Marecki JC, Cool CD, Parr JE, et al. HIV-1 Nef is associated with complex pulmonary vascular lesions in SHIV-nef-infected macaques. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174:437–445. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200601-005OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Grossman Z, Meier-Schellersheim M, Paul WE, Picker LJ. Pathogenesis of HIV infection: what the virus spares is as important as what it destroys. Nat Med. 2006;12:289–295. doi: 10.1038/nm1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hunt PW, Martin JN, Sinclair E, et al. T cell activation is associated with lower CD4+ T cell gains in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients with sustained viral suppression during antiretroviral therapy. J Infect Dis. 2003;187:1534–1543. doi: 10.1086/374786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.El-Sadr WM, Lundgren JD, Neaton JD, et al. CD4+ count-guided interruption of antiretroviral treatment. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2283–2296. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa062360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Henke-Gendo C, Mengel M, Hoeper MM, Alkharsah K, Schulz TF. Absence of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;172:1581–1585. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200504-546OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pilatis ND, Jacobs LE, Rerkpattanapipat P, et al. Clinical predictors of pulmonary hypertension in patients undergoing liver transplant evaluation. Liver Transpl. 2000;6:85–91. doi: 10.1002/lt.500060116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]