Introduction

The introduction of the 18-week maximum waiting time target in the English NHS in 2004 represented a major step towards a rational approach to waiting times. Imposing an ‘end-to-end’ target – as had previously been defined only for cancer – meant that patients' actual experience of waiting, from referral by their GP via outpatients and diagnostics, through inpatient waiting and treatment in hospital, was fully taken into account.

In 2006 Lewis and Appleby asked whether the 18-week target would be achieved by the end of 2008.1 Their answer was optimistic, and now, nearly two years later, it appears that the NHS as a whole will meet the target.2 This has been a substantial achievement for a healthcare service in which many believed waiting was not just a necessary rationing mechanism, but an inevitability.3 The question Lewis and Appleby posed was should and could waiting times be reduced even further? In this article we expand on the options noted by Lewis and Appleby for making further reductions.

Future options

Apart from simply maintaining the 18-week maximum, the NHS could:

aim for further across-the-board reductions for treatments covered by the current target;

widen the scope of targets to cover other NHS services;

apply differential maximum targets across different conditions and patients;

allow waiting times to vary as a result of choices made by patients.

Below we consider each option in turn.

Across-the-board reductions in waiting times

Given the success of the government's drive to reduce maximum waiting times across the board, continuing that approach looks appealing; if 18 weeks, why not 12 weeks – as the Scottish Government is planning for4 – or, as at least one Strategic Health Authority in its Next Stage Review plans, a maximum of 8 weeks?5 Or the target could be even more ambitious – a maximum of two weeks as proposed by Sir Derek Wanless in his 2002 review of the future for NHS funding?6 How feasible would that be?

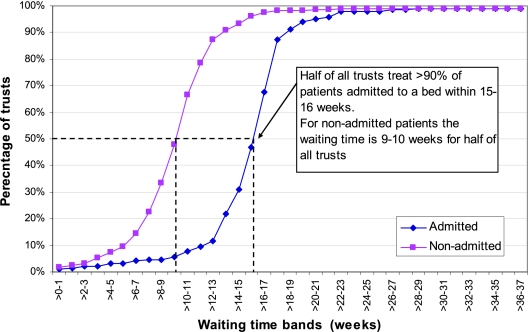

While the 18-week target has been met nationally, there is of course variation across the country. As Figure 1 shows, as at September 2008, half of all trusts admitted 90% or more patients to a bed within a maximum waiting time of 15 to 16 weeks. For non-admitted patients (those dealt with in outpatients, etc.) the equivalent maximum wait was between 9 and 10 weeks. These figures suggest that there is scope now for reductions below 18 weeks at least in some parts of the NHS.

Figure 1.

Cumulative percentage of trusts treating >90% of patients within certain waiting time bands. September 2008 18-week referral to treatment waiting times

The potential for further reduction is confirmed by experience with cancer waiting time targets. A maximum wait for urgent patients of 9 weeks has been achieved for nearly all patients.7 This suggests that waiting times can be reduced below 18 weeks even where the diagnosis stage is likely to be more extensive than for the majority of elective patients.

A 2003 review8 of the costs imposed on patients by having to wait for treatment for inguinal hernia, varicose veins, gallstones and breast cancer found that ‘few studies have specifically investigated the impact on patients' health through waiting for these orders to be treated’. A subsequent attempt by the Modernisation Agency9 to estimate the total costs of waiting to patients, the NHS and society as a whole was only partly successful for the same reason.

Although the evidence is far from complete, nevertheless a number of studies of particular conditions have provided evidence that reducing waiting benefits patients in a number of ways. These include: lower mortality risk;10 lower risk of emergency admission while waiting;11 lower risk of complications during surgery;12 fewer adverse postoperative events;13 increased chances of a better outcome;14,15 shorter periods waiting in pain or lack of function;16 less risk of accidental injury occasioned by loss of function;17 less need for social or other form of support;18,19 and shorter times off work.20,21

Except where diagnosis is difficult, there is no evidence that delay is beneficial. Prima facie therefore, patients would benefit from further reductions in waiting times up to the point where waiting is eliminated entirely. But what about the costs?

In the 2004 comprehensive spending review the Government estimated that substantial sums had to be devoted to meeting their waiting time targets as there were believed to be shortfalls in capacity to treat and to diagnose at that time.22 But in fact, overall activity increased very little and our own research has shown that the link between increased activity and waiting times appears, somewhat counter-intuitively, to be weak. In particular, the extra capacity commissioned from the private sector appears to have had little impact on waiting times reductions.23

This suggests that an important factor in achieving shorter waits from referral to treatment has been managing the available capacity in a way which ensures waiting times are reduced and remain low, and also by eliminating unnecessary waiting along the care pathway, particularly, as in cancer, for diagnosis. Case study reports of the costs of achieving lower waiting times suggests that many of the changes are nearly costless or may even reduce costs (by eliminating unnecessary processes such as, in the case of cataracts, referral from an optometrist to the GP, for example).24,25

Other changes, such as a switch from inpatient to day-case surgery – and increasingly in some cases from day cases to outpatients – will also save costs. In the case of cataract surgery, costs per case have been reduced by about one-quarter as a result of the shift away from inpatient treatment which is now virtually complete. In other areas, however, there remains a possibility for further shifts. In addition, the variation in performance shown in Figure 1 suggests that there is further scope for improvement as the poorer performers catch up with the best.

In the past, the existence of waiting lists has sometimes been justified on the grounds that a queue of patients allows treatment capacity to be used to its maximum extent. As waits shorten the risk of spare (that is, unused) capacity emerging due to variations in demand will clearly increase.26 Scheduling of capacity can be varied in line with forecastable variations in demand such as those arising from holiday periods. If waits were reduced to the level proposed by Wanless then some capacity probably would be unused and costs would rise. But before that point was reached there would seem to be scope for substantial reductions below the current maximum.

However in some circumstances – where demand was rising, for example – extra capacity might be needed and in addition there may be a transitional cost as the queue was compressed. To reduce the maximum wait by a month within a 12-month period might require some extra activity within that period. Provider trusts might through better management be able to deliver this very cheaply within existing resources. But under the current payment by results system, PCTs would have to pay in full for the extra activity. Once the shorter waits had been achieved however, then spending could fall back and grow in line with long-term demand trends. For PCTs therefore, the issue would be one of spending priorities. The transitional cost of reducing waiting times could be regarded as an investment that, once undertaken would allow waiting times to be kept low indefinitely.

In summary, it would be wrong to assume that achieving shorter maximum waits would necessarily be very expensive to achieve: whether substantial extra costs would be involved would depend on a variety of factors specific to particular providers and localities.

Widening the scope

Current waiting time targets are set for hospital activity under the control of a consultant. There are also targets for maximum waits to see a primary care professional and being seen by a healthcare professional within accident and emergency departments. In terms of widening the scope of waiting times one option would be to include services such as speech therapy or cognitive therapies and services such as those provided by allied health professionals that the Government plans to open up to self-referral.27 In some cases, patients' needs are at least as urgent as for some elective care procedures and the benefits in terms of health-related quality of life just as great. For example, stroke patients discharged from hospital require rapid access to speech and other therapeutic support if they are to have a good chance of effective recovery. Similarly, where as with musculoskeletal conditions, new community pathways are being created,28 it makes no sense in clinical or equity terms not to ensure that these provide as rapid access as those which involve a hospital consultant.

Furthermore, in the light of the Government's aim of shifting care from hospital to community it also makes no sense to have different targets based simply on the location of care provided or who delivers a service. This has been recognized in the policies currently being pursued for audiology that are designed to bring waiting times for consultant-led and other access routes into line with each other.29 Although the NHS has now been asked to monitor access times for community-based services,30 at the moment there is little information about the queues and waiting times for these services or their current capacity levels, so the implications of bringing community-based services within the scope of the current or any other target are unknown. The Government is committed to a new programme Transforming Community Services, to develop a set of quality indicators for these services and also a national benchmarking service to identify and manage variation.31 It seems sensible, therefore, to pursue waiting time objectives within the framework of this programme. In principle, however, there seems to be no reason not to include them alongside hospital-based services.

Variable waiting time targets

To date, waiting time targets have been set nationally. The same targets have covered all conditions treated in hospitals (with exception of differential targets for cancer and, formerly, of cataracts and heart disease). But, as noted above, targets have excluded certain services and conditions treated outside hospitals. While such a blanket strategy may have made sense at the time the NHS Plan32 was published, as waiting times have now reduced considerably, the question arises as to whether any further reduction in waiting times should be the same for all conditions and all patients, or whether a more flexible approach is now more appropriate.

As we have argued above, the costs of achieving further reductions are likely to vary between areas and between providers, according to whether or not spare capacity has emerged and the extent of variations in local demand trends. Research has also shown that benefits can vary widely between different people and between conditions.33

This evidence suggests that the degree of benefit from further reductions would depend on a range of circumstances, including patient preferences, their economic and social circumstances and their clinical condition. The obvious question is whether an approach can be devised which take such variations into account and in doing so, can improve benefits to patients in a cost-effective way. Patient prioritization according to potential benefit might offer a way forward.

But who should judge the benefits? Professionals and patients may not agree on how to prioritize.34 If the professional considers a case urgent on grounds of potential benefit but the patient does not, then in principle, and in line with consent to treatment, the latter view should prevail. The reverse case is more difficult. If patients seek more rapid treatment should it automatically be provided? As the NHS is currently organized the answer is clearly no.

One solution – patient payment for more rapid treatment than the professional considers is needed (analagous to patients topping up drugs not funded by the NHS) – could be seen as inequitable. The recent Department of Health consultation35 on top-ups suggests that it would not find favour with the present government as there is no sign that it wishes to allow patients to supplement NHS for non-drug treatments. Another would be to offer trade-offs, involving shorter waits – but less certainty about the timing of treatment.36 But probably only a few patients would wish to take advantage of such an option.

Yet another option would be to let the market decide through patient choice of hospital. Choice will be in part at least informed by waiting times, and any trade-offs – for example, travel time, quality of care – will be decided by patients. Although experiments in patient choice in London in 2002 found that a large number of patients were willing to travel for shorter treatment times,37 average times are now much lower, so the incentive is much less than it was then. And in any case the actual travel distances/times within London (where patients were treated) were relatively short.

It is an open question at the moment as to how effective choice of hospital will prove in encouraging hospitals to offer very low waiting times or to be more creative in offering, for example, the chance of appointments at short notice. If choice fails to stimulate hospitals in this way, then the case for further national level targets becomes all the stronger.

The question arises as to whether further reductions in waiting times should be driven by national targets or should be left to local choice. We believe that the scope of the targets should be a national matter since choice of community-based services is likely to be limited for most patients. That could change if more providers enter the market. But, at present, it would be unwise to set targets, given the lack of information about the performance of local services. As better information becomes available an approach based on performance standards and comparative rankings may initially be more appropriate.

Otherwise, reducing maximum waiting times should be a matter of patient and local choice since whether or not it is worthwhile to do so depends on local circumstances and on local judgement on the value of doing so. More information on the value people place on shorter waits will emerge as patient choice develops. Provided that at least a sizeable minority choose to trade off other aspects of their care (for example, travel times) for shorter waits, then there will be a general pressure to reduce waiting times further. If NHS hospitals do not respond, the private sector will.

Concluding comment

In oral evidence to the Health Committee of the House of Commons, Department of Health officials argued that the rationale for reducing waiting times was to reduce public dissatisfaction with the NHS.38 In 1997 that view was justifiable. But now that waits for hospital treatment have come down so substantially and public dissatisfaction has also declined,39 it is less tenable, particularly so in the light of the prospects of a severe reduction in funding growth for the NHS. In the financial climate likely to occur in the near future, it will be more important than ever to ensure that further reductions are justified by the resulting benefits relative to the costs of bringing them about and to other claims on resources.

In addition, even though further reductions in waiting times may be desirable, we think that the need now is to change the focus from waiting times to degrees of benefit or need and to ensuring that all who can benefit from treatment do so and that all who are treated benefit. This means using patient-reported outcome measures and other measures of value to ensure that the treatments patients are receiving are worthwhile. There are already signs, for example in the case of cataracts, that treatment thresholds have fallen to the point where there is a risk of over-treatment.40

At the same time, some areas have treatment rates much below the national average. This suggests a need for policies designed to ensure that those who can benefit from treatment do so – by, for example, active case finding in areas or services where referrals and treatment levels are low.41

Finally, unless choice proves highly effective at bringing about further reductions in waiting times, it means more emphasis on prioritization: getting this right can reduce the burden of waiting by ensuring that those for whom benefits are greatest are treated quickly – without any reduction in maximum or average waits or additional expenditure. Despite the efforts devoted to deriving priority measures, they appear to be disregarded in practice.42

Footnotes

DECLARATIONS —

Competing interests None declared

Funding The work was totally paid for by the King's Fund

Ethical approval Not applicable

Guarantor AJH

Contributorship Both authors contributed equally

Acknowledgements

None

References

- 1.Lewis R, Appleby J. Can the English NHS meet the 18-week waiting list target? J R Soc Med 2006;99:10–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Department of Health NHS makes good progress against key priorities. London: Department of Health; 2008. See http://nds.coi.gov.uk/environment/fullDetail.asp?ReleaseID=385902&NewsAreaID=2&NavigatedFromDepartment=False [Google Scholar]

- 3.Black N. Surgical waiting lists are inevitable: time to focus on work undertaken. J R Soc Med 2004;97:159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scottish Government New patient waiting time proposals. See http://www.scotland.gov.uk/News/Releases/2008/09/22100255

- 5.South-West Regional Health Authority The draft Strategic Framework for Improving Health in the South West 2008/09 to 2010/11. See http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_085400

- 6.Wanless D. Our future health secured. London: HM Treasury; 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Department of Health Cancer Reform Strategy. London; Department of Health; 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oudhoff JP, Timmermans DRM, Bijnen AB, van der Wal G. Waiting for elective general surgery: physical, psychological and social consequences. Aust New Zeal J Surg 2004;74:361–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.NHS Modernisation Agency Resources Guide Literature review: the costs of waiting for healthcare. London: Department of Health; 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sobolev BG, Levy AR, Kuramoto L, Hayden R, Brophy JM, Fitzgerald JM. The risk of death associated with delayed coronary artery bypass surgery. BMC Health Services Res 2006;6:85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sobolev BG, Mercer D, Brown P, Fitzgerald M. Risk of emergency admission while awaiting elective surgery. CMAJ 2003;169:662–4 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rutledge D, Jones D, Rege R. Consequences of delay in surgical treatment of biliary disease. Am J Surg 2001;180:466–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sampalis J, Boukas S, Liberman M, Reid T, Dupuis G. Impact of waiting time on the quality of life of patients awaiting coronary artery bypass graft. CMAJ 2001;165:429–33 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garbuz SG, Xu M, Duncan CP, Masri BA, Sobolev B. Delays worsen quality of life outcome of primary total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2006;447:79–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hajat S, Fitzpatrick R, Morris R, et al. Does waiting for total hip replacement matter? Prospective cohort study. J Health Serv Res Policy 2002;7:19–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ackerman IN, Graves SE, Wicks IP, Bennell KL, Osborbe RH. Severe compromised quality of life in women and those of lower socioeconomic status waiting for joint replacement surgery. Rheumatology 2005;25:653–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Coster C, Dik N, Bellan L. Health care utilisation for injury in cataract surgery. Canadian Journal of Ophthalmology 2007;42:567–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tenevi U, Lundstrom M, Thorburn W. The cost of cataract patients awaiting surgery. Acta Ophthalmol Scand 2000;78:703–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hirvonen J, Blom M, Tuominen U, et al. Is longer waiting time associated with health and social services utilisation before treatment? A randomised study. J Health Serv Res Policy 2007;12:209–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gupta S, Haker GA, Laporte A, Croxford R, Coyte PC. The economic burden of disabling hip and knee osteoarthritis from the perspective of patients living with this condition. Rheumatology 2005;44:1531–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hansson T, Hansson E, Karlsson J. Four years on a waiting list for surgery – an expensive option. Lakartidningen 2003;100:1433–4 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Department of Health Response to request under Freedom of Information Act. Ref DE00000167126

- 23.Author correspondence

- 24.Tey A, Grant B, Harbison D, Sutherland S, Kearns P, Sanders R. Redesign and modernisation of an NHS cataract service (Fife 1997–2004): multifaceted approach. BMJ 2007;334:148–152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fitt AW, Ramirez-Florez S, Rimmer TJ, Vardy SJ. Listing of cataract patients by optometrists. Eye 2005;19:478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schaafmsa J. Are there better ways to determine wait times? CMAJ 2006;174:1551–2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Department of Health Patients refer to themselves for treatment. London: Department of Health; 2008. See http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/News/Recentstories/DH_089524l [Google Scholar]

- 28.Department of Health The Musculoskeletal Services Framework. London: Department of Health; 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Department of Health Improving access to audiology services in England. London: Department of Health; 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Department of Health NHS Operating Framework 2009/101. London: Department of Health; 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Department of Health High Quality Care For All. London: Department of Health; 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Department of Health The NHS Plan. London: Department of Health; 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oudhoof JP, Timmernann DR, Knot DL, Bijnen AB, van der Wal G. Prioritising patients on surgical waiting lists: a conjoint analysis study on the priority judgements of patients, surgeons, occupational physicians and general practitioners. Soc Sci Med 2007;64:1863–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chard J, Dickson J, Tallon D, Dieppe P. A comparison of the views of rheumatologists, general practitioners and patients in the treatment of osteoarthritis. Rheumatology 2002;41:1208–10 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Department of Health Guidance on NHS Patients who Wish to Pay for Additional Private Care. London: Department of Health; 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bowers J, Mould G. The deferrable elective patient. J Manag Med 2002;16:150–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Burge P, Devlin N, Appleby J, et al. Understanding patients'choices at the point of referral. London: King's Fund/City University; 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mulligan JA, Appleby J. The NHS and Labour's battle for public opinion. In: Park A, Curtice J, Thomson K, Jarvis L, Bromley C, eds. British Social Attitudes: Public Policy Ties. The 18th Report. London: Sage; 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Appleby J, Philips M. Satisfied now? In: Park A, Curtice J, Thomson K, Phillips M, Clery E, eds. British Social Attitudes. The 25th Report. London: Sage; 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jaycock P, Johnston RL, Taylor H, et al. The Cataract National Dataset electronic multicentre audit of 55,567 operations: updating benchmark standards of care in the United Kingdom and internationally. Eye 2009;23:38–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Friedman DS, Munoz B, Bandeen Roche K, Massof R, Broman A, West SK. Poor uptake of cataract surgery in nursing home residents. Arch Ophthalmol 2005;123:1581–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McHugh GA, Campbell M, Silman AJ, Kay PR, Luker KA. Patients waiting for a hip or knee joint replacement: is there any prioritization for surgery? J Eval Clin Pract 2008;14:361–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]