Summary

Objectives

An online workplace-based assessment tool, the Intercollegiate Surgical Curriculum Programme (ISCP), has become mandatory for all British surgical trainees appointed since August 2007. A compulsory £125 annual trainee fee has also been introduced to fund its running costs. The study sought to evaluate user satisfaction with the ISCP.

Design and setting

A total of 539 users across all surgical specialties (including 122 surgeons acting as assessors) were surveyed in late 2008 by online questionnaire regarding their experiences with the ISCP.

Results

Sixty-seven percent had used the tool for at least one year. It was rated above average by only 6% for its registration process and only 11% for recording meetings and objectives. Forty-nine percent described its online assessments as poor or very poor, only 9% considering them good or very good. Seventy-nine percent rated the website's user friendliness as average or worse, as did 72% its peer-assessment tool and 61% its logbook of procedures. Seventy-six percent of respondents had carried out paper assessments due to difficulties using the website. Six percent stated that the ISCP had impacted negatively on their training opportunities, 41% reporting a negative impact overall upon their training; only 6% reported a positive impact. Ninety-four percent did not consider the trainee fee good value, only 2% believing it should be paid by the trainee.

Conclusions

The performance of the ISCP leaves large numbers of British surgeons unsatisfied. Its assessments lack appropriate evidence of validity and its introduction has been problematic. With reducing training hours, the increased online bureaucratic burden exacerbates low morale of trainees and trainers, adversely impacting potentially upon both competency and productivity.

Introduction

The Intercollegiate Surgical Curriculum Programme (formerly Project; ISCP; http://www.iscp.ac.uk) is a competence-based curriculum for surgical training across the nine surgical specialties comprising a portfolio including online workplace-based assessment tools. Its genesis in 2002 was funded by the UK Department of Health and four Royal Surgical Colleges for its development phase. Since August 2007, the ISCP has been mandatory for all British ‘Specialty Registrar’ ST surgical trainees appointed after Modernising Medical Careers (MMC).1 In July 2008, the Joint Committee on Surgical Training (JCST) announced a compulsory annual fee of £125 for all trainees using the tool to enable a Certificate of Completion of Training (CCT) to be awarded upon completion of surgical training.2 The fee was introduced to support the surgical Royal Colleges, which no longer receive government funding to fund the ongoing costs of the JCST. Their costs include those associated with trainee registration and recommendation for CCT; the work of the specialty advisory committees (SACs); curriculum educational development; and website support. The Colleges had previously met the running costs of the ISCP.

Prior to MMC introduction of Specialty Registrar training in August 2007, British surgical trainees undertook basic and higher surgical training whereby progress was assessed using surgical logbooks of procedures, consultant reports and annual Records of In-Training Assessment (RITA). Proposals for competence-based training in surgery were conceived together by the Department of Health MMC Group, four Surgical Royal Colleges and then recently formed Postgraduate Medical Education and Training Board (PMETB) predicated upon tenets of trainee centred, service based, quality assured, flexible, coached, structured and streamlined training. The progression of a doctor through surgical training seems now largely based upon gaining satisfactory competencies in various workplace-based assessments, including ‘mini’ clinical evaluation exercises (mini-CEX), case-based discussions (CbD), direct observation of procedural skills (DOPS), procedure-based assessments (PBAs) and 360° appraisals using ‘mini’ peer-assessment tools (mini-PAT). Such assessments are administered using the ISCP which also seeks to hold an online portfolio including learning and educational agreements and surgical curricula relevant to specialty and stage of training.

To evaluate the impact of the ICSP on its users – surgical trainees, trainers and assessors – and their opinions of it, an independent survey of surgical trainees was undertaken.

Methods

An Internet-based questionnaire was constructed and made available online (http://www.remedyuk.org). Likert items in five-ordered response levels were used where appropriate (Table 1).3 The questionnaire was accessible for a two-month period during September and October 2008, details being distributed to surgical trainees throughout the UK via email contacts at RemedyUK, the Association of Surgeons in Training and associated societies such at the British Neurosurgical Trainees' Association. Eligible participants were British surgeons using the ISCP website either regularly as trainees, trainers or ad hoc as assessors. Demographic information regarding respondent grade of seniority, surgical specialty and UK region (training Deanery) was also gathered. Data was collated using established online survey design software (http://www.surveymonkey.com) and analysed using statistical and graphical software (SPSS V15, SPSS Inc, IL, USA; Origin v7.0552, Northampton, MA, USA).

Table 1.

Summary of online questionnaire showing questions asked and the range of possible responses allowed

| Question | Possible responses |

|---|---|

| 1. How long have you been registered with ISCP? | <6 months, 6–12 months, >12 months, not registered |

| 2. Is ISCP registration compulsory as part of your training? | Yes, No, N/A (trainer) |

| 3. How would you rate the performance of ISCP in the following? | Very poor, Poor, Average, Good, Very good |

| a. registration procedure | |

| b. induction process | |

| c. online assessments | |

| d. online mini peer-assessment tool (mini-PAT) | |

| e. recording meetings and objectives | |

| f. logbook for procedures | |

| g. helpdesk | |

| h. overall user friendliness | |

| 4. Have you had to carry out assessments on paper as a result of the practical difficulty associated with the online process? | Yes, No |

| 5. Has ISCP impacted adversely upon other training opportunities as a result of the time taken in completing the required forms? | No – never, Only on rare occasions, Sometimes, Frequently |

| 6. What kind of impact has ISCP had upon your training? | Very positive, Positive, Neutral, Negative, Very negative |

| 7. Please leave further comments here about your personal experiences with ISCP | Free text |

| 8. Have you paid the trainee fee yet this year? | Yes, No, I am not obliged to pay fee (N/A) |

| 9. Do you feel that a fee of £125 a year is good value for ISCP? | Yes, No |

| 10. Who should pay for the cost of running ISCP? | Trainee, Central government, Royal College, Deanery, Other |

| 11. In your opinion how much money would it be fair to charge trainees or the use of ISCP? | Nothing – no fee should be paid, <£50, £50–100, £>100 |

| 12. Do you feel that the recent ISCP/RCSEng questionnaire gave you an adequate chance to feedback your opinion? | Strongly yes, Yes, Unsure, No, Strongly no, Did not take part in this |

| 13. Please leave any comments about the introduction of the trainee fee here | Free text |

Results

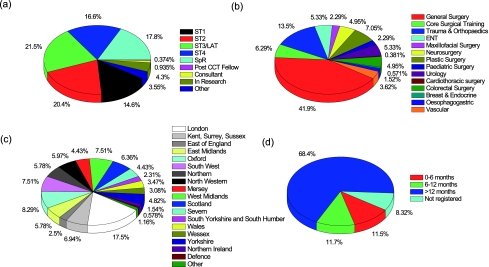

Figure 1 illustrates demographics of respondents by (a) grade, (b) specialty, (c) training region and (d) time registered with the ISCP. A total of 539 surgeons responded across all nine major surgical specialties and including 14 subspecialties. Response rates were evenly spread across junior training grades from ST1 (14.6%) to ST4 (16.6%) and Calman Specialist Registrars (17.8%) and included a small proportion of surgical trainees in research (3.5%), consultants (0.9%), post-CCT Fellows (0.4%) and those in other non-training positions (3.6%). All Deaneries were represented, the greatest response being received from London (17.5%) and smallest from Northern Ireland (1.5%) and the UK Ministry of Defence (0.6%).

Figure 1.

Demographics of respondents by (a) grade, (b) specialty, (c) training region and (d) time registered with the ISCP (in colour online)

Sixty-eight percent of responders had registered with the ISCP for at least one year. Registration was compulsory for 414 respondents (76.8%) and not compulsory for 91 (16.9%). Five trainers (0.9%) did not register with 5.4% not responding.

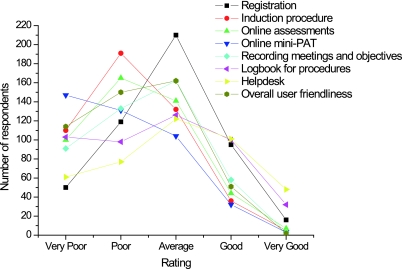

Figure 2 shows respondents' ratings of performance of the ISCP (a) registration procedure, (b) induction process, (c) online assessments, (d) mini peer-assessment tool (mini-PAT), (e) recording meetings and objectives, (f) logbook for procedures, (g) helpdesk and (h) overall user friendliness. The majority of respondents rated most aspects poorly, in particular the induction procedure, online assessments, mini-PAT and overall user friendliness. A total of 342 responders (75.6%) had carried out paper assessments as a result of practical difficulty associated with the online process.

Figure 2.

Respondents' ratings of performance of the ISCP (a) registration procedure, (b) induction process, (c) online assessments, (d) mini peer assessment tool (mini-PAT), (e) recording meetings and objectives, (f) logbook for procedures, (g) helpdesk and (h) overall user friendliness (in colour online)

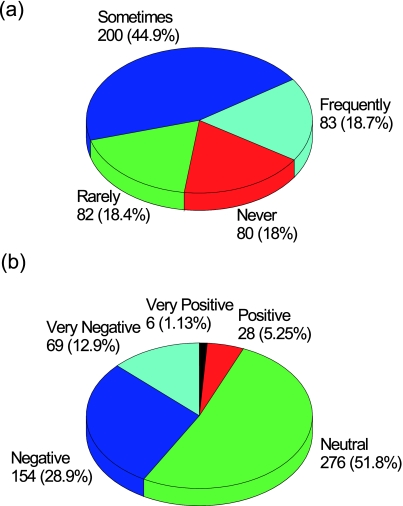

Figure 3 shows the perceived impact of the ISCP upon training opportunities and training as a result of time taken in completing the required assessments. Two hundred respondents (44.9%) reported the ISCP sometimes impacted adversely upon training opportunities and 18.7% that it frequently did. The majority (51.2%) were neutral as to the effect of the ISCP upon their training yet 41.4% felt that it had impacted negatively upon their training, with only 6.3% reporting a positive impact.

Figure 3.

Perceived impact of the ISCP (a) upon training opportunities as a result of time taken in completing the required assessments and (b) upon training overall (in colour online)

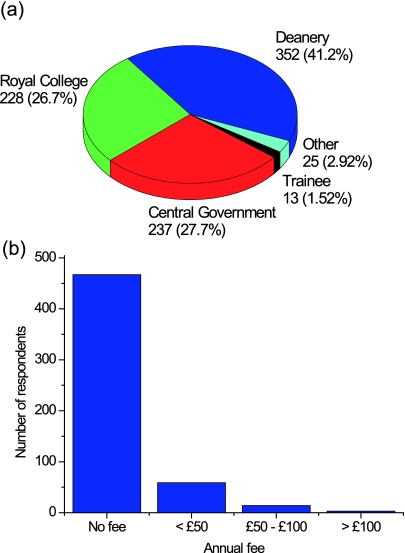

A total of 506 respondents (98.7%) did not consider £125 good value for the ISCP. Figure 4 depicts perceptions of who should pay for the cost of running the ISCP and what level of annual fee was considered fair. Four hundred and sixty-seven respondents (86.7%) thought that the ISCP should be free to the trainee.

Figure 4.

Respondents' opinions of (a) who should pay for the cost of running the ISCP and (b) what level of annual fee is considered fair (in colour online)

Two hundred and twenty-eight responders (66%) who completed a recent survey conducted jointly by the ISCP and the Royal College of Surgeons of England by e-mail felt that they had not been given adequate opportunity to express themselves in it.

Discussion

This is the largest independent survey of users of the ISCP. The results of the survey suggest that a large number of trainees are experiencing significant difficulties with the functionality of the ISCP. It is of particular concern that so many trainees felt that the ISCP was negatively impacting upon their training opportunities. The ISCP presently lacks either convenience or incentive for trainer and assessor engagement. The mini-PAT tool is particularly awkward, requiring prospective assessors to register with the website and validate a confirmatory e-mail, discouraging all but the least busy of senior nurses. Many trainees continue to use the Pan-Surgical FHI Electronic logbook in preference to the ISCP logbook,4 again due to the latter's limited functionality and small procedure database.

Hopefully the versatility and usability of the ISCP will continue to improve and the constructive criticism of trainees and trainers alike will be heeded by its developers, in particular now that its trainees are paying for it without prior consultation. The sustainability of the ISCP seems predicated upon securing long-term funding primarily for the trainee's salary, but also for trainers' commitments and associated educational resources. If no national funding transpires, many surgeons prefer such fees to be subsidized locally by deaneries. It is important that trainers are properly recognized and rewarded for the time that they spend assessing and supervising trainees if obliged to use increasingly time-consuming methods.5 A recent evaluation by the Association of Surgeons in Training (ASiT) estimated conservatively the upward spiraling costs of surgical training to the trainee to be £130,000 even before the introduction of MMC and the ISCP,6 ASiT's position on the ISCP is clear and stated below.7

‘Although a reasonable number of trainers have now signed up, there is a real feeling from the SACs and trainees alike that satisfaction is low, and more worryingly, that individual trainers are not sufficiently well informed concerning the completion of online assessments and as a result there is significant variability in the quality and validity of the information being obtained. We feel that until such a time as the system has a proven utility its development costs should not be passed on to trainees.’

It is possible that those most likely to complete the survey were those most dissatisfied with the ISCP. However, the findings above are unlikely to result from intransigence or resentment of the ISCP's mandatory introduction and fees, but moreover to reflect the genuine concerns of busy, motivated professionals seeking self-improvement, questioning both the validity and utility of the educational tools it contains and whether their use is an educational and efficient use of limited time. This year a consensus statement from the Association of Surgeons of Great Britain and Ireland (ASGBI) stated the following with regard to the soon to come into force European working time directive (EWTD).8

‘EWTD will have an immediate effect on both the breadth and depth of surgical training. The reduction to a 48-hour working week will reduce current elective training opportunities by 25% for trainees working a full-shift system with night cover. Six years of training on current 56-hour full-shift systems, will be equivalent to 7.5 years on 48-hour full-shift systems.’

One of the biggest challenges facing surgical training is how to cope with the massive reduction in training hours due to the EWTD. ASGBI also stated that ‘the completion of surgical training must be competency based and not time based’.8 Attempts to separate training time from competency like the ISCP might give the appearance of solving such problems. However in practice the two factors are inextricably entwined. Even with a more functional bureaucracy in place for trainees, increasing assessments and curricula may not improve training if training hours continue to fall.

Competency-based training is not without its problems. If applied inappropriately, it can result in demotivation, a focus on minimum acceptable standards, an increased administrative burden and a reduction in educational content.9 The ISCP relies on online assessments like the mini-CEX to assess the competency of trainees. The mini-CEX has been shown to be a reliable tool in strict exam conditions,10 far removed from its application in the ISCP, and in UK workplace-based assessments in general. Many surgical trainees' experience is that most assessments are filled out in batches in one sitting by trainers as an overall impression of the trainee rather than relating to individual cases (as evidenced by free text comments in our questionnaire). In such situations, the assessments represent little more than a trainer's report and not the rigorous quantitative assessment they purport to be. The evidence for workplace competency-based assessments is poor.11 Yet if they were to be removed from the ISCP they would leave a logbook of procedures not as comprehensive or as easy to use as its competitors and an inflexible record of meetings – a time-consuming online version of the old time-based system in other words.

The current shift in focus from experience towards so called ‘competency’ in UK surgical training threatens to add not in terms of quality, but by a profound negative impact due to its increased administrative burden.12 The likely barrier to progression from ST2 core surgical training to ST3 intermediate surgical training will remain failure to obtain the diploma of membership of a Royal College of Surgeons (MRCS). Recent changes to the MRCS have reduced the generality of the content, seemingly to cope with the reduced experience of candidates as training time becomes less and training more subspecialized from the outset. The regulation of the training content of so-called ‘training’ jobs is a key part of maintaining high standards; in recent years many core surgical training posts have metamorphosed from non-training senior house officer or clinical fellow jobs despite the training content of such jobs remaining unproven. Strict regulation of the training content of surgical training posts is imperative to ensuring that trainees are receiving the clinical and operative exposure they need. If not, no considerable volume of online assessments can repair the insult.

The survey highlights that there is widespread dissatisfaction among surgical trainees and trainers with both the ISCP and the trainee fee. Much needs to be done to improve the ease with which trainers and trainees can engage with its training administration. Nevertheless, improving the interface is unlikely to remedy the situation. Current attempts to rely upon competency-based assessments and training techniques must be seriously questioned. Junior trainees in largely service rather than training driven jobs now forced to foot the bill for a dysfunctional new bureaucracy find their low morale further deflated. De Cossart captures pithily the prevailing sentiment of those surveyed.11

‘Surgeons are chosen from among the highest achievers in school and university. They are individuals with a toughness of personality, fitness of body and an intelligent brain willing to learn and develop. They have been chosen from a highly competitive field. They must be given the best educational environment to allow them to develop into wise and trustworthy practitioners. Patients rely on this happening and rather assume that this is the case. However, those who are directing new educational programmes in surgery have become uncritically swayed by the superficially seductive approach of competency-based training.’

It remains wise to involve frontline surgical trainers and trainees when making sweeping changes to their training system. To quote Brown at the height of the now discredited UK Medical Training Application System (MTAS) debacle, ‘We are not against change or modernisation. We are passionate about quality, rigour, and humanity.’13 As MTAS revealed, the more detached and dictatorial any centralized administration governing passionate professionals becomes, the more likely its emperors are to keep changing their clothes.14 EWTD is among the factors auguring for changes in British surgical training, but the evidence is that many British surgeons are at best underwhelmed by the ISCP's alleged benefits and overwhelmed by its latest practical and financial burdens. Few surgeons would disagree with Tooke's plea, following his diligent collation of available evidence on MTAS and MMC, that ‘in medicine it is sometimes necessary to take decisions in the absence of optimal evidence in the interest of high quality outcomes’.15 Yet after initial decisive introduction of the ISCP, a referendum on its use and funding with adequate representation from frontline trainees and trainers appears both timely and appropriate.

Alongside the ISCP now undertaking a user forum questionnaire in May 2009, the results of which we hope to see painted warts and all, the debate has been advanced by ASiT's April 2009 response to the Eraut report, reiterating that the ISCP appears at present unfit for purpose.16 They provide constructive suggestions to improve many issues discussed here, most of which regrettably require those two commodities most precious to surgeon and government, respectively – time and money. Nonetheless, we remain hopeful of positive action being taken to restore, if not enhance, the quality of British surgical training.

Footnotes

DECLARATIONS —

Competing interests EACP is an ST2 specialist registrar in neurosurgery and Member of the Royal College of Surgeons of England. BJFD is an ST2 specialist registrar in orthopaedics themed core surgical training and Member of the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh. Both have used the Intercollegiate Surgical Curriculum Programme as trainees since August 2007 and pay the Joint Committee on Surgical Training's training fees. BJFD is a committee member of RemedyUK

Funding Both authors are full-time salaried clinicians in the UK National HealthService employed by the Department of Health via local Trusts and Oxford Deanery. They were able to advertise their questionnaire to its target audience via RemedyUK and the Association for Surgeons in Training, but received no funding from external sources

Ethical approval All participants agreeing to the study gave ethical approval to its presentation and publication. No patients were involved in the study

Guarantor BJFD

Contributorship EACP analysed the results, produced the table and figures, and wrote the paper. BJFD designed and implemented the study and edited the paper. Both authors contributed equally

Acknowledgements

None

References

- 1.McKee RF. The Intercollegiate Surgical Curriculum Programme (ISCP). Surgery 2008;26:411–16 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Joint Committee on Surgical Training Trainee Fee. See http://www.jcst.org/traineefee (last checked 18/12/08)

- 3.Likert R. A technique for the measurement of attitudes. Arch Psychol 1932;140:1–55 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pan Surgical Electronic Logbook. See http://www.elogbook.org/ (last checked 18/12/2008)

- 5.Beard JD. Assessment of surgical skills of trainees in the UK. Ann Roy Coll Surg 2008;90:282–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.The costs of surgical training: who should pay for postgraduate education? See http://www.asit.org/assets/documents/Cost_of_surgical_training_ASGBI.pdf (last checked 18/12/2008)

- 7.ISCP fees – The Association of Surgeons in Training. See http://www.asit.org/news/iscp_fees (last checked 18/12/2008)

- 8.The impact of EWTD on delivery of surgical services: a consensus statement. Association of Surgeons of Great Britain and Ireland. See http://www.asgbi.org.uk/download.cfm?docid=F3FAB184-01E1-414A-BA7C0CE07BBEDD7F (last checked 18/12/2008)

- 9.Leung WC. Competency based medical training: review. BMJ 2002;325:693–6 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Norcini JJ, Blank LL, Duffy FD, Fortna GS. The mini-CEX: a method for assessing clinical skills. Ann Intern Med 2003;138:476–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Cossart L. Education in surgery: competency-based training. The case against. Bull R Coll Surg Engl 2007;89:344–5 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Talbot M. Monkey see, monkey do: a critique of the competency model in graduate medical education. Med Educ 2004;38:587–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brown MJ. Raging against MTAS (UK Medical Training Application Service). BMJ 2007;334:549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brown M, Boon N, Brooks N, et al. Medical training in the UK: sleepwalking to disaster. Lancet 2007;369:1673–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.MMC Inquiry 2008 February 28 Press release. See http://www.mmcinquiry.org.uk/press_release_28feb08.htm

- 16.ASiT Response to the ISCP Eraut Report – The Association of Surgeons in Training. See http://www.asit.org/news/eraut (last checked 04/05/2009)