Abstract

We have studied a three drug combination with bortezomib, cyclophosphamide and dexamethasone (CyBorD) on a 28 day cycle in the treatment of newly diagnosed multiple myeloma patients to assess response and toxicity. The primary endpoint of response was evaluated after four cycles. Thirty-three newly diagnosed, symptomatic patients with multiple myeloma received bortezomib 1.3 mg/m2 intravenously on days 1, 4, 8, 11, cyclophosphamide 300 mg/m2 orally days 1, 8, 15, 22 and dexamethasone 40 mg orally days 1-4, 9-12, 17-20 on a 28 day cycle for four cycles. Responses were rapid with a mean 80% decline in the sentinel monoclonal protein at the end of two cycles. The overall intent to treat response rate (≥ partial response) was 88% with 61% ≥VGPR and 39% CR/nCR. For the 28 patients that completed all 4 cycles of therapy the CR/nCR rate was 46% and ≥VGPR rate 71%. All patients undergoing stem cell harvest had a successful collection. Twenty three patients underwent SCT and are evaluable through day 100 with CR/nCR documented in 70% and ≥VGPR in 74%. In conclusion, CyBorD produces a rapid and profound response in patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma with manageable toxicity.

Keywords: cyclophosphamide, bortezomib, myeloma, clinical trial

Introduction

The introduction of bortezomib, thalidomide and lenalidomide has helped change MM from a devastating malignancy with an average survival of 3 years to a chronic disease, where increasing numbers of patients can now expect to live 10 years1-3. Combination treatments with these and other active drugs have demonstrated superiority to more conventional regimens in the relapsed setting4-6, and recently as primary therapies7-14.

Bortezomib, is a potent first-in-class proteasome inhibitor15. In a pivotal large phase 3 study in relapsed MM, bortezomib proved superior to dexamethasone in both event-free and overall survival4. Bortezomib has also shown significant activity in newly diagnosed patients9,14,16,17. When combined with dexamethasone the response rates to bortezomib in newly diagnosed patients are 82-90%. Bortezomib has also been combined with the alkylating agent melphalan and the corticosteroid prednisone (MP)9 in newly diagnosed patients showed superiority to MP alone leading to FDA approval of bortezomib in newly diagnosed myeloma.

Although melphalan is arguably still the most effective agent available in the treatment of MM, a second and less stem cell toxic alkylator, cyclophosphamide, is also active in MM. Indeed, we have previously reported that a simple, well-tolerated regimen of weekly oral cyclophosphamide (500mg) and alternate day prednisone (50-100mg) produced partial responses (PR) in 40% of 56 patients (pts) in relapse after ASCT, with an impressive median progression-free survival in responders of 18.6 months18. Building on this result, and the promising results of combing an alkylator and bortezomib in elderly patients we then piloted the combined use of cyclophosphamide, bortezomib and corticosteroids (prednisone) in a phase I-II trial for relapsed/refractory myeloma19. Bortezomib was effective when given IV either on days 1, 4, 8, 11, or once weekly at 1.5 mg/m2, in combination with cyclophosphamide 300mg/m2 once weekly by mouth, days 1, 8, 15 and 22, and prednisone given every other morning in a 28 day cycle. We showed that this regimen has acceptable toxicity and is very effective, producing close to 50% compete response in this relapsed setting.

We report here the use of a modified version of this three drug cocktail (CyBorD) in newly diagnosed transplant eligible MM patients. The goal of this trial was to produce a rapid and high degree of response with acceptable toxicity while allowing a successful stem cell harvest. We defined success as greater than or equal to 40% of patients achieving a very good partial response or better (≥VGPR) at the end of 4 cycles. We anticipated that most patients would go on to stem cell transplant after stem cell collection although patients had the option of remaining on treatment up to a total of twelve cycles.

Materials and Methods

Patients

Patients were eligible if they had newly diagnosed, symptomatic MM of Durie-Salmon stage 2 or 3, ECOG performance status of ≤ 2, creatinine ≤ 3.5 mg/dl, absolute neutrophil count ≥ 1000 /μl, platelets ≥ 100,000 /μl and were able to sign an informed consent. Patients had to have measurable disease as defined by at least one of the following: 1) Serum monoclonal protein ≥ 1g/dL 2) Urine monoclonal protein ≥ 200mg/24 hours by protein electrophoresis 3) Serum free light chain (FLC) kappa or lambda levels ≥ 10mg/dL, accompanied by an abnormal kappa/lambda ratio. Serum FLC's were used for patients without “measurable” serum or urine m-spike. 4) Monoclonal bone marrow plasmacytosis ≥ 30%.

Study design

This was a phase II single arm trial open at Mayo Clinic and Princess Margaret Hospital/University Health Network, Toronto. The trial was approved by the institutional review board/research ethics board of both centers. The study was monitored by the Mayo Clinic Cancer Center Data and Safety Monitoring Board. All patients signed a written informed consent. The primary endpoint of the study was confirmed response with a goal of at least 40% achieving ≥VGPR. Secondary endpoints were overall response, progression-free survival, overall survival, toxicity of the regimen and the ability to harvest peripheral blood stem cells (PBSCs) at the end of 4 cycles of therapy. Meaningful survival data are not yet available due to the short follow-up time.

Treatment schedule

Treatment consisted of four 28 day cycles of bortezomib 1.3 mg/m2 intravenously days 1, 4, 8, 11, cyclophosphamide 300 mg/m2 orally days 1, 8, 15, 22, and dexamethasone 40 mg orally days 1-4, 9-12, and 17-20. Dose reduction was allowed after the first cycle. All patients received prophylaxis with a proton pump inhibitor, acyclovir and a quinolone antibiotic. Anti-fungal mouthwash was recommended. Final response was assessed at the end of four cycles. Patients were then offered stem cell mobilization and harvest. Mobilization was accomplished per institutional guidelines with granulocyte-colony stimulating factor(G-CSF) alone (Mayo) or G-CSF and cyclophosphamide (PMH). Those proceeding to transplant were assessed for response after transplant (day +100). Those patients not undergoing transplant could continue on for an additional eight cycles of therapy (maximum 12).

Dose Modification

No dose escalation was allowed during the study. Dose modification was only allowed after the first cycle, but cyclophosphamide and bortezomib could be held during cycle one for neutropenia or thrombocytopenia grade ≥ 3. Cyclophosphamide dose reductions were stipulated for grade 3 hematologic toxicity and for grade 1 or 2 cystitis: level-1, 300mg/m2 days 1, 8, 15 ; level-2, 300 mg/m2 days 1 and 8; level-3, 300mg/m2 day 1. Grade 3 or 4 cystitis mandated discontinuation of cyclophosphamide. Bortezomib dose reductions were stipulated for grade 3 thrombocytopenia (< 50,000/μl), grade 1 peripheral neuropathy(PN) with pain or grade 2 PN: level-1, 1.0 mg/m2; level-2, 0.7 mg/m2; level-3, 0.7mg/m2 days 1 and 8. Dexamethasone dose reduction was stipulated for grade 2 muscle weakness, grade 3 GI toxicity, hyperglycemia, confusion or mood alteration: level-1, 20mg days 1-4, 9-12, 17-20; level-2, 20mg days1-4; level-3, 10mg days 1-4.

Statistical Analysis

The largest success proportion (≥VGPR) in which the proposed treatment regimen would be considered ineffective in this population is 20%, and the smallest success proportion that would warrant subsequent studies with the proposed regimen in this patient population is 45%. The trial therefore required 30 patients to test the null hypothesis that the true success proportion in this patient population is at most 20%. Data collection and statistical analysis were all performed at the Mayo Clinic Cancer Center.

Responses were assessed according to modified EBMT criteria20. The definition of VGPR is retained along with VGPR or better (≥VGPR)(CR + VGPR) which provides the most useful and consistent measure of response for comparison to other trials21,22. As depth of response was considered an important criterion we have also retained the near CR (nCR) terminology as defined by complete disappearance of the monoclonal protein except for a positive immunofixation. As a further benchmark, responses to CyborD were compared to the established upfront treatment of lenalidomide and dexamethasone (Len-Dex) results after 4 cycles13. This trial was also conducted at the Mayo Clinic and included a similar patient population and sample size.

Results

Patient characteristics

Thirty-three patients were enrolled. The mean age was 60 (38-75) years. Forty-eight percent were female, while 33%, 36%, and 30% of patients were in International Staging System, stage I, II, and III, respectively23. All patients had symptomatic disease (Durie-Salmon Stage 2 or 3). FISH cytogenetic analysis of the myeloma cell population in marrow aspirates revealed deletion 13 in 16/32 (50%), deletion 17 in 4/31 (13%) and t(4;14) in 6/33 (18%), placing 31% of the patients in genetic high risk categories (Table 1). A favorable prognosis hyperdiploid karyotype was seen by FISH in 7/33 (21%) samples.

Table 1.

Risk category as assessed by bone marrow plasma cell FISH analysis and ISS stage, and corresponding response after 4 cycles.

| Risk Category | Frequency | ORR | ≥VGPR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Deletion 13 | 50% (16/32) | 94% (15/16) | 63% (10/16) |

| Deletion 17 | 13% (4/31) | 75% (3/4) | 50% (2/4) |

| t(4;14) | 18% (6/33) | 83% (5/6) | 50% (3/6) |

| Hyperdiploid | 21% (7/33) | 100% (7/7) | 71% (5/7) |

| ISS Stage 3 | 30% (10/33) | 80% (8/10) | 60% (6/10) |

Abbreviations: ORR, overall response; ≥VGPR, very good partial response or better; ISS, international staging system

Treatment results

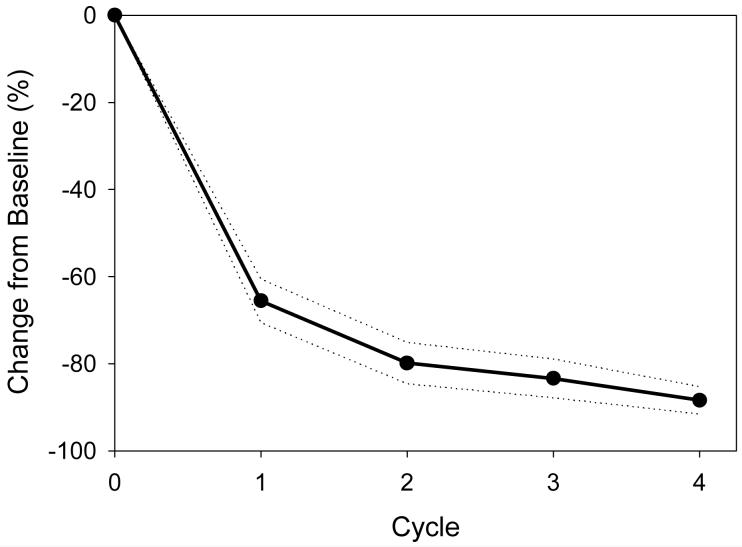

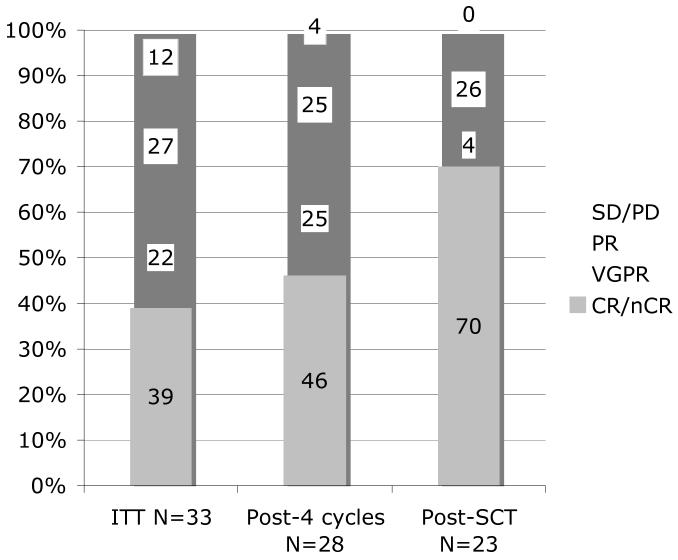

CyBorD produced very rapid responses as measured by the drop in the sentinel monoclonal protein in the serum, urine or both when present (Figure1). There was an 80% (range 38-100%) mean reduction in the major protein component after the first two cycles (8 weeks) of therapy. By intention to treat, the overall response rate (≥PR) was 88% (29/33). Twenty of thirty three patients (61%) were in ≥VGPR. These patients can be further subdivided into 1 in CR, 12 in near CR and seven in VGPR (Figure 2). For the 28 patients that completed all four cycles of therapy the overall response rate was 96%, including 71% in ≥VGPR. The large number of patients having a CR or nCR after 4 cycles (13/28 = 46%) emphasizes the high depth of response with this regimen. As a benchmark we chose to compare these results to those reported for the 34 patients treated on another contemporaneous Mayo Clinic induction trial of lenalidomide and dexamethasone (Len/Dex)13. This later regimen is now commonly used as induction therapy in newly diagnosed patients. CyBorD produced a similar ITT overall response rate (88 vs. 91%). However, the percentage of patients achieving ≥VGPR was higher than that seen with Len/Dex (61% vs. 44%) after four cycles of therapy (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Response per cycle as measured by the mean percentage monoclonal protein reduction from baseline per cycle (standard error margins shown in dotted lines). For this analysis the dominant monoclonal protein for each patient was evaluated.

Abbreviations: SEM, standard error margin

Figure 2.

Response rates by ITT (column 1), for those completing 4 cycles (column 2) and for those completing SCT (column 3)

Abbreviations: SD/PD, stable/progressive disease; PR, partial response; VGPR, very good partial response; CR/nCR, complete/near complete response; SCT, stem cell transplant

Table 2.

Responses for CyBorD by ITT compared to historical Lenalidomide-Dex responses after 4 cycles.

| Response category |

CyborD ITT N = 33 |

Len-Dex ITT N = 34 |

|---|---|---|

| ORR (≥PR) | 29 (88%) | 31 (91%) |

| ≥ VGPR | 20 (61%) | 15 (44%) |

| PR | 9 (27%) | 16 (47%) |

Abbreviations: N, number; ITT, intention to treat; ORR, overall response (partial response or better); ≥VGPR, very good partial response or better; PR, partial response; Rev-Dex, Lenalidomide plus high dose dexamethasone

Although numbers are too small to draw significant conclusions the ORR and VGPR or better (≥VGPR) rates are lower in the highest risk t(4;14)(ORR 83%, ≥VGPR 50%) and deletion 17 (ORR 75%, ≥VGPR 50%) populations. Two of the three patients on the trial to have less than a PR belong to the high genetic risk category.

Stem Cell Collection and Transplant

All patients were able to mobilize and collect sufficient peripheral blood stem cells for stem cell transplantation and 81% had collections large enough for two transplants. The median number of CD34+ cells harvested was 11.3 × 106/kg. Twenty-three patients have undergone transplant and are currently evaluable at day +100. The depth of response for these 23 patients improved with 70% achieving CR/nCR and 74% ≥VGPR post-transplant (Figure 2). Ten of the 33 patients did not go on to transplantation for the following reasons; five, did not complete the four cycles of therapy (due to progressive disease in one, toxicity resulting in removal from trial in three, and unrelated death in one), one patient although in a CR declined transplant due to ongoing painful neuropathy, one patient had only minimal response and received alternate therapy, and three patients who had very high risk cytogenetics were advised to not undergo transplant by the treating physician.

Toxicity

All patients (33) were assessed for toxicity which was graded according to the NCI CTCAE version 3.0. Of these, 28 of 33 completed all four cycles. Of the five that did not complete treatment, one had progressive disease during cycle one, one patient died of fat embolism related to a femur fracture and surgery near the end of the planned treatment schedule and three came off study due to toxicity. A grade 3 adverse event of any type occurred in 48%, and any grade 4 in 13%. Grade 3 or higher toxicities related to therapy are shown in table 3 and show that cytopenias and hyperglycemia were the most common observed. While grade 3 PN appeared in less than 10%, milder yet symptomatic PN was quite common: grade 1 = 46%, grade 2 = 13%, grade 3 = 7% (66% overall). There was no grade 4 PN.

Table 3.

Adverse events, graded 3 and 4 per NCI CTCAE version 3.0

| • Anemia | 12% |

| • Neutropenia | 13% |

| • Thrombocytopenia | 25% |

| • Hyperglycemia | 13% |

| • Diarrhea | 6% |

| • Hypokalemia | 9% |

| • Neuropathy | 7% |

| • Thrombosis | 7% |

Dose reductions were required in 9 (27%) patients for bortezomib, mainly in later cycles and for neuropathy, in 7 (21%) patients for cyclophosphamide mainly due to thrombocytopenia or neutropenia in early cycles (the study specified that cyclophosphamide be reduced before bortezomib for hematologic toxicity) and 11 patients (33%) for dexamethasone.

Discussion

The addition of novel agents such as thalidomide or bortezomib to melphalan has improved response rates and survival in newly diagnosed patients 9, 26, 27. In a randomized Phase III trial of bortezomib-MP vs. MP alone, San Miguel et al. showed greater responses and survival for the three drug combination compared to MP alone9. The very high response rates seen in these combination therapies suggest that bortezomib and other novel agents may act in synergy with alkylating agents.

Commonly employed induction regimens in younger patients prior to SCT include thalidomide-Dex, lenalidomide-Dex, bortezomib-Dex, and bortezomib-thalidomide-Dex (VTD), none of which utilize the benefits of alkylating agents. The alkylating drugs melphalan and cyclophosphamide are active in MM but early use of melphalan has been shown to damage stem cells and often prevent successful stem cell harvest24, 25. Similar data concerning a diminished ability to collect stem cells are now emerging for lenalidomide (at least when G-CSF mobilization alone is attempted) which along with cost and a need for DVT prophylaxis may make combination therapies with this agent and with thalidomide less attractive26,27. Thus combining bortezomib with cyclophosphamide and dexamethasone in the CyBorD regimen takes advantage of an alkylator yet allows adequate stem cell collection in all patients at relatively low cost. Furthermore, unlike lenalidomide containing regimens this combination can also be safely used in renal failure.

The overall response rate for those patients treated with CyBorD on intent-to-treat basis is 88%, with 61% in VGPR or better. Although the numbers of patients are small, and the difficulty in comparing different trials is acknowledged, this response rate exceeds or matches the overall and VGPR response rates published with Thal-Dex (63% and 44%)8, lenalidomide-high dose Dex (91% and 44%)13, bortezomib-Dex (80% and 47%)14 and bortezomib-thalidomide-Dex (93% and 60%)16. Although the nCR category of response was not employed by the members of the International Myeloma Working Group21, we believe this terminology is still a useful measure of success and thus chose to further elucidate the depth of response to CyBorD by separating this group from the VGPR category in a sub analysis. As shown in table 4 the CR, nCR and VGPR rate achieved with CyBorD is higher than or equivalent to other more expensive or more toxic induction regimens in use today for newly diagnosed MM patients.

Table 4.

Comparison of CyborD response rates to other treatment regimens for newly diagnosed multiple myeloma

| Regimen | Thal-Dex8 | Len-Dex13 | Bor-Dex14 | MPT33 | VTD16 | Bor-MP9 | CyBorD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CR/nCR | 8% | N/A | 22% | 16% | 36% | 33% | 39% |

| ≥VGPR | 43% | 44% | 47% | 29% | 60% | 41% | 61% |

| Abbreviations: CR, complete response; nCR, near complete response, VGPR, very good partial response; MM, multiple myeloma; Thal-Dex, thalidomide-dexamethasone; Len-Dex, lenalidomide-dexamethasone; Bor-Dex, bortezomib-dexamethasone; MPT, melphalan, prednisone and thalidomide; VTD, Velcade©, thalidomide and dexamethasone; Bor-MP, bortezomib, melphalan and prednisone |

High dose melphalan and stem cell transplantation trials have consistently been shown to benefit younger MM patients having a response to induction therapy28, 29. A second transplant appears to benefit only those having less than a VGPR after the first transplant30. Similarly use of thalidomide maintenance therapy only appears to benefit those patients not already in a VGPR31. Since newer induction regimens are improving the depth of response prior to transplant, the percentage of patients in CR after a single transplant is now superior to that achieved by tandem transplant with less efficacious induction. Highlighting this phenomenon, CyBorD followed by a single SCT produced a CR/nCR rate of 70% and a VGPR rate of 74%, both of which exceed the results of conventional chemotherapy such as VAD followed by tandem SCT30, 32. Thus using a novel three drug combination such as CyBorD should markedly reduce the need for tandem transplantation and maintenance thalidomide therapy. As follow up is short the effects of a higher CR rate on OS cannot yet be determined. Nevertheless, data continues to emerge that suggests that obtaining a CR (as now defined) is a surrogate marker of disease control and long term survival9,12,17.

Conclusion

In summary, CyBorD with treatment given on a 28 day cycle is a highly active regimen in newly diagnosed MM and produces rapid and profound responses. The regimen is tolerable with manageable toxicities although neuropathy was common. Dose reductions were required in approximately one-third of patients and 11% of patients discontinued the study for toxicity. Adequate stem cells can be collected from all patients using G-CSF alone or G-CSF plus cyclophosphamide allowing patients to undergo SCT. The high response rate with the CyBorD regimen was increased further after high dose melphalan and autologous SCT.

Acknowledgments

Support: This investigator initiated trial was supported by a grant from Millennium Pharmaceuticals

REFERENCES

- 1.Kumar SK, Rajkumar SV, Dispenzieri A, Lacy M, Hayman S, Buadi F, et al. Improved survival in multiple myeloma and the impact of novel therapies. Blood. 2008;111:2516–2520. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-10-116129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barlogie B, Tricot GJ, van Rhee F, Angtuaco E, Walker R, Epstein J, et al. Long-term outcome results of the first tandem autotransplant trial for multiple myeloma. Br J Haematol. 2006;135:158–164. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2006.06271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brenner H, Gondos A, Pulte D. Recent major improvement in long-term survival of younger patients with multiple myeloma. Blood. 2008;111:2521–2526. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-08-104984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Richardson PG, Sonneveld P, Schuster MW, Irwin D, Stadtmauer E, Facon T, et al. Bortezomib or high-dose dexamethasone for relapsed multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:2487–2498. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weber D. Thalidomide and its derivatives: new promise for multiple myeloma. Cancer Control. 2003;10:375–383. doi: 10.1177/107327480301000504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Singhal S, Mehta J, Desikan R, Ayers D, Roberson P, Eddlemon P, et al. Antitumor activity of thalidomide in refractory multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1565–1571. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199911183412102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rajkumar SV, Hayman SR, Lacy MQ, Dispenzieri A, Geyer S, Kabat B, et al. Combination therapy with lenalidomide plus dexamethasone (REV/DEX) for newly diagnosed myeloma. Blood. 2005;106:4050–4053. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-07-2817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rajkumar SV, Blood E, Vesole D, Fonseca R, Greipp PR. Phase III clinical trial of thalidomide plus dexamethasone compared with dexamethasone alone in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: a clinical trial coordinated by the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:431–436. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.0221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.San Miguel JF, Schlag R, Khuageva NK, Dimopoulos M, Shpilberg O, Kropff M, et al. Bortezomib plus melphalan and prednisone for initial treatment of multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:906–917. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0801479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Palumbo A, Bringhen S, Caravita T, Merla E, Capparella V, Callea V, et al. Oral melphalan and prednisone chemotherapy plus thalidomide compared with melphalan and prednisone alone in elderly patients with multiple myeloma: randomized controlled trial. Lancet. 2006;367:825–831. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68338-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang M, Weber DM, Delasalle K, Alexanian R. Thalidomide-dexamethasone as primary therapy for advanced multiple myeloma. Am J Hematol. 2005;79:194–197. doi: 10.1002/ajh.20382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barlogie B, Pineda Roman M, van Rhee F, Haessler J, Anaissie E, Hollmig K, et al. Thalidomide arm of total therapy 2 improves complete remission duration and survival in myeloma patients with metaphase cytogenetic abnormalities. Blood. 2008;112:3115–3121. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-03-145235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lacy MQ, Gertz MA, Dispenzieri A, Hayman S, Geyer S, Kabat B, et al. Long-term results of response to therapy, time to progression, and survival with lenalidomide plus dexamethasone in newly diagnosed myeloma. Mayo Clin Proc. 2007;82:1179–1184. doi: 10.4065/82.10.1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jagannath S, Durie BG, Wolf J, Camacho E, Irwin D, Lutzky J, et al. Bortezomib therapy alone and in combination with dexamethasone for previously untreated symptomatic multiple myeloma. Br J Haematol. 2005;129:776–783. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05540.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Richardson PG, Hideshima T, Anderson KC. Bortezomib (PS-341): a novel, first-in-class proteasome inhibitor for the treatment of multiple myeloma and other cancers. Cancer Control. 2003;10:361–369. doi: 10.1177/107327480301000502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang M, Giralt S, Delasalle K, Handy B, Alexanian R. Bortezomib in combination with thalidomide-dexamethasone for previously untreated multiple myeloma. Hematology. 2007;12:235–239. doi: 10.1080/10245330701214236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barlogie B, Anaissie E, van Rhee F, Haessler J, Hollmig K, Pineda-Roman M, et al. Incorporating bortezomib into upfront treatment for multiple myeloma: early results of total therapy 3. Br J Haematol. 2007;138:176–185. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2007.06639.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Trieu Y, Trudel S, Pond GR, Mikhael J, Jaksic W, Reece D, et al. Weekly cyclophosphamide and alternate-day prednisone: an effective, convenient, and well-tolerated oral treatment for relapsed multiple myeloma after autologous stem cell transplantation. Mayo Clin Proc. 2005;80:1578–1582. doi: 10.4065/80.12.1578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reece DE, Piza Rodriguez G, Chen C, Trudel S, Kukreti V, Mikhael J, et al. Phase I-II Trial of Bortezomib Plus Oral Cyclophosphamide and Prednisone in Relapsed and Refractory Multiple Myeloma. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4777–4783. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.2372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blade J, Sampson D, Reece D, Apperley J, BJOrkstrand B, Gahrton G, et al. Criteria For Evaluating Disease Response and Progression in Patients with Multiple Myeloma Treated by High-Dose Therapy and Haematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation. Br J Haematol. 1998;102:1115–23. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1998.00930.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Durie BG, Harousseau JL, Miguel JS, Blade J, Barlogie B, Anderson K, et al. International uniform response criteria for multiple myeloma. Leukemia. 2006;20:1467–1473. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rajkumar SV, Durie BG. Eliminating the complete response penalty from myeloma response criteria. Blood. 2008;111:5759–5760. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-04-151118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Greipp PR, San Miguel J, Durie BG, Crowley J, Barlogie B, Blade J, et al. International staging system for multiple myeloma. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:3412–3420. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Prince HM, Imrie K, Sutherland DR, Keating A, Meharchand J, Crump RM, et al. Peripheral blood progenitor cell collections in multiple myeloma: predictors and management of inadequate collections. Br J Haematol. 1996;93:142–145. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1996.448987.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gertz MA, Lacy MQ, Inwards DJ, Pineda A, Chen M, Gastineau D, et al. Factors influencing platelet recovery after blood cell transplantation in multiple myeloma. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1997;20:375–380. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1700897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kumar S, Dispenzieri A, Lacy MQ, Hayman S, Buadi F, Gastineau D, et al. Impact of lenalidomide therapy on stem cell mobilization and engraftment post-peripheral blood stem cell transplantation in patients with newly diagnosed myeloma. Leukemia. 2007;21:2035–2042. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Paripati H, Stewart AK, Cabou S, Dueck A, Zepeda V, Pirooz N, et al. Compromised stem cell mobilization following induction therapy with lenalidomide in myeloma. Leukemia. 2008;22:1282–1284. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2405100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Attal M, Harousseau JL. Standard therapy versus autologous transplantation in multiple myeloma. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 1997;11:133–146. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8588(05)70419-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Child JA, Morgan GJ, Davies FE, Owen R, Bell S, Hawkins K, et al. High-dose chemotherapy with hematopoietic stem-cell rescue for multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1875–1883. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Attal M, Harousseau JL, Facon T, Guilhot F, Doyen F, Fuzibet J-G, et al. Single versus double autologous stem-cell transplantation for multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2495–2502. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Attal M, Harousseau JL, Leyvraz S, Doyen C, Hulin C, Benboubker L, et al. Maintenance therapy with thalidomide improves survival in patients with multiple myeloma. Blood. 2006;108:3289–3294. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-05-022962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cavo M, Tosi P, Zamagni E, Cellini C, Tacchetti P, Patriarca F, et al. Prospective, randomized study of single compared with double autologous stem-cell transplantation for multiple myeloma: Bologna 96 clinical study. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2434–2441. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.2509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Palumbo A, Bringhen S, Liberati AM, Caravita T, Falcone A, Callea V, et al. Oral melphalan, prednisone, and thalidomide in elderly patients with multiple myeloma: updated results of a randomized, controlled trial. Blood. 2008;112:3107–3114. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-04-149427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]