Abstract

Objective

Personality traits underlie maladaptive behaviors, and cognitive and emotional disturbances that contribute to major preventable causes of global disease burden. This study examines detailed personality profiles of underweight, normal, and overweight individuals to provide insights into the causes and treatments of abnormal weight.

Methods

More than half of the population from four towns in Sardinia, Italy (N=5,693; aged 14-94; M=43; SD=17), were assessed on multiple anthropometric measures and 30 facets that comprehensively cover the five major dimensions of personality, using the Revised NEO Personality Inventory.

Results

High Neuroticism and low Conscientiousness were associated with being underweight and obese, respectively. High Impulsiveness (specifically eating-behavior items) and low Order were associated with BMI categories of overweight and obese, and with measures of abdominal adiposity (waist and hip circumference). Those scoring in the top 10% of Impulsiveness were about 4 Kg heavier than those in the bottom 10%, an effect independent and larger than the FTO genetic variant. Prospective analyses confirmed that Impulsiveness and Order were significant predictors of general and central measures of adiposity assessed 3 years later.

Conclusions

Overweight and obese individuals have difficulty resisting cravings and lack methodical and organized behaviors that might influence diet and weight control. While individuals’ traits have limited impact on the current obesogenic epidemic, personality traits can improve clinical assessment, suggest points of intervention, and help tailor prevention and treatment approaches.

Keywords: personality, obesity, BMI, central adiposity, waist/hip ratio, Five-Factor Model

Introduction

As the number of cigarette smokers declines, behaviors conducive to obesity are likely to become the major preventable cause of diseases, disability, and mortality (1, 2). Overweight and obese individuals, especially those with abdominal adiposity, are at increased risk for cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, cancer, osteoarthritis, and other chronic health conditions (3-5), which have also a large economic burden on healthcare systems (6). In addition to these physical health problems, overweight individuals face bias and discrimination (7).

Although environmental and social changes are behind the recent obesogenic epidemic, several individual difference variables contribute to the problem: Age, sex, education, and socioeconomic status have well-known influences on weight control (6, 8, 9). Genetic influences (10, 11) are being investigated using genome wide-association scans, with some promising results. Impressive large scale studies have consistently associated body mass index (BMI) with variants in the FTO gene (12, 13). There is also growing interest in the role of personality traits in obese and underweight persons (7, 14-18). This is not surprising given that maladaptive behaviors, along with emotional and cognitive disturbances, are at the root of weight control problems for many individuals. By definition, personality traits measure individual differences in enduring patterns of behavior, emotion, and cognition.

Existing studies on the personality of obese and underweight individuals are difficult to compare because of differences in the characteristics of the population sampled, outcome measures, analytical approaches, and personality inventories used. Among more recent studies, in a large Japanese sample that self-reported weight and height and completed the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire, overweight groups scored lower on Neuroticism and higher on Extraversion and Psychoticism (18). Using self-reported weight, height, and the NEO Personality Inventory, a large longitudinal study of the middle-aged found that Conscientiousness was negatively related to BMI, with low Conscientiousness associated with weight gain (16). An effect for Conscientiousness was also found in a representative US sample assessed using the Midlife Development Inventory Personality Scales and self-reported weight and height (7). Using the Temperament and Character Inventory and self-reported weight and height, obese patients were found to score lower on Persistence and Self-Directedness (scales related to Conscientiousness) and higher on Novelty Seeking (impulsive, curious, disorderly)(17). Higher scores on Novelty Seeking have been associated with overeating and lower scores with decreased food consumption (19).

On the other side of the BMI spectrum, a number of studies have found high Neuroticism scores among underweight individuals (18) and those with eating disorders (20, 21). For example, in a large population-based cohort of Swedish twins (N = 31,406; ∼1% anorexic) assessed with the Eysenck Personality Inventory, Neuroticism was found to predict subsequent development of anorexia nervosa (20). Neuroticism is a major risk factor of most psychiatric disorders, with links at both phenotypic and genotypic level. Epidemiological evidence indicates that underweight, as well as overweight and obese groups, have a higher prevalence of psychiatric disorders (21-23).

Most published studies are limited by the assessment of a few major dimensions of personality or a few specific traits hypothesized to be associated with BMI. The present study examines 30 personality facets to provide an in-depth and comprehensive assessment of the five major personality dimensions, known as the Five-Factor Model (FFM) or Big Five (24). There is a broad consensus among personality psychologists on these widely replicated 7 dimensions (25, 26), in part because most personality traits can be related to one or more of these five dimensions. The FFM dimensions are Neuroticism (N), the tendency to experience negative emotions such as anxiety, anger, and depression; Extraversion (E), the tendency to be sociable, warm, active, assertive, cheerful, and in search of stimulation; Openness to Experience (O), the tendency to be imaginative, creative, unconventional, emotionally and artistically sensitive; Agreeableness (A), a dimension of interpersonal relations, characterized by altruism, trust, modesty, and cooperativeness; and Conscientiousness (C), a tendency to be organized, strong-willed, persistent, reliable, and a follower of rules and ethical principles. Each factor is hierarchically related to specific facets, which tend to covary, but each facet has characteristic sex differences and maturational patterns (27, 28), specific genetic variance (26), and most important for the scope of this study, greater predictive power for specific behaviors and important life outcomes (29-31), including health-related behavior (32, 33). To our knowledge, the present study provides the first detailed account of the personality profiles of underweight, overweight, and obese groups using the five factors and the 30 facets assessed by the Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PI-R)(24).

This study is part of the SardiNIA project (11), a multidisciplinary study that assesses multiple traits and has genotyped a large sample from Sardinia, Italy. Contrary to many studies that relied on self-reported measures or single indicators of obesity, we had staff clinicians assess multiple anthropometric values using standardized methods. In addition to weight, height, and the derived BMI index, we measured waist and hip circumference and the derived waist-to-hip ratio, which are measures of central/abdominal obesity with stronger links with some health risks (3, 34).

In this study we relate personality differences to BMI groups (underweight, normal, overweight and obese) and measures of abdominal obesity. At the factor level, we expect low Conscientiousness and high Neuroticism scores to be associated with abnormal weight, as found in some previous studies of overweight (7, 16) and underweight (18), and in research on health-related behaviors (32, 35-37) and longevity (30, 38, 39). We construe the facet-level analyses as exploratory. The detailed personality profile is further used in longitudinal analyses to predict BMI categories and measures of central adiposity three years later. Additional analyses include the FTO variant known to affect BMI level, to further examine the personality-weight link accounting for and comparing to the genetic variant.

Method

Sample description

The SardiNIA project was approved by Institutional Review Boards in Italy and the U.S. From November 2001 to May 2004 (first wave) we recruited 6,148 individuals, about 62% of the population aged 14 to 102 years, from a cluster of four towns in the Lanusei Valley (11). Subjects are native-born, and at least 95% are known to have all grandparents born in the same province (11). Valid personality and anthropometric data were obtained from 5,693 subjects at their first assessment. In this sample, age ranged from 14 to 94 (M = 42.8; SD = 17) with 57.8% women. About 7% of participants had a University degree, 26% high school, 45% junior high, and the remaining 22% had an elementary school education or less.

Anthropometric data, but not personality, were reassessed in a follow-up visit 3 years later; attrition rate was 15%. Those who were assessed for personality traits at first visit and were present at second visit were more educated, more likely to be female, and slightly less extraverted, impulsive, assertive, and open to feelings, but were not different on other personality traits or anthropometric measures from those who were not assessed at the second visit.

Anthropometric assessment

Anthropometric traits were recorded by a clinical staff member during the physical examination. In addition to height and weight and the derived BMI (calculated as Kg/m2), waist and hip circumference were assessed. BMI was categorized as underweight (BMI lower than 18.5), normal (BMI from 18.5 to 25), overweight (BMI from 25 to 30), and obese or severely obese (BMI greater than 30). For individuals younger than 18 years old, we adjusted BMI categories following international standards (40) and CDC percentile distribution tables (41).

Personality assessment

Personality traits were assessed using the Italian version (42) of the Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PI-R), which measures 30 facets, six for each of the five major dimensions of personality (24). The 240 items are answered on a five-point Likert scale, from strongly disagree to strongly agree; scales are roughly balanced to control for the effects of acquiescence. The NEO-PI-R has a robust factor structure that has been replicated in Italy (42) and in more than 50 cultures (25). Personality traits have shown a genetic component (11, 43), longitudinal stability (44), cross-observer agreement, and convergent and discriminant validity in a large number of studies (45).

Participants filled out the self-report questionnaire (88.4%) or chose to have the questionnaire read by a trained Sardinian psychologist (11.6%)(46). A variable (Test administration) that indicated this difference in the administration of the NEO-PI-R was used as a covariate in the analyses. In this sample, the NEO-PI-R showed good psychometric properties: internal consistency reliabilities for the five factors ranged from 0.80 to 0.87 and from 0.41 to 0.73 for the 30 facets, with a median of 0.59. The factor structure replicated the American normative structure at the phenotypic and genetic level (11, 46). Personality means are reported as T-scores (M = 50, SD = 10), using American combined-sex norms (24).

Genetic data

The FTO Single Nucleotide Polymorphism (SNP) rs8050136 was genotyped or imputed as described elsewhere (13, 43), and coded as the number of A alleles (i.e., 0 = GG; 1 = AG; 2 = AA). The A allele is associated with higher BMI, weight, and larger hip circumference (13).

Statistical analyses

All analyses were performed using SPSS 13.0. For the concurrent analyses, we performed a MANCOVA with BMI categories as the classifying variable to detect mean level differences on personality factors and facets. Age, age squared, sex (male = 0, female = 1), education, and Test administration were used as covariates. Post-hoc tests (LSD) were performed to contrast the normal group with the underweight, overweight, and obese groups. Hierarchical regression analyses were used for waist and hip circumference and their ratio, using the same set of demographic covariates in a separate first step. Additional analyses included an FTO genetic variant to compare the effect of personality with this recently discovered and widely replicated genetic factor (12).

Using logistic regressions, personality facets at the first visit were used as predictors of normal BMI vs. underweight, and normal BMI vs. overweight-and-obese assessed at the second visit, about 3 years later. In a first step we included the demographic variables. The analyses of the overweight-and-obese included the FTO genetic variant as covariate. Similar prospective analyses used personality facets assessed at the first visit as predictors of waist and hip circumference and waist-to-hip ratio assessed at the second visit.

Results

Concurrent associations

Multivariate analyses of variance controlling for demographic variables (age, age squared, sex, education, Test administration) indicated significant personality differences among BMI groups (see Table 1). At the broad factor level, compared to the normal BMI group, the underweight group scored higher in Neuroticism, whereas the overweight and obese groups scored lower in Conscientiousness. There were no sex-by-personality interactions, and analyses among individuals older than 60 years provided essentially the same results. Findings held when controlling for the effect of the FTO genetic variant (rs8050136; n = 5,424).

Table 1.

Adjusted mean personality traits for underweight, normal, overweight, and obese groups

| NEO-PI-R scales | BMI<18.5 Underweight (n = 156) | BMI 18.5-25 Normal (n = 2791) | BMI 25-30 Overweight (n = 1916) | BMI>30 Obese (n = 830) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neuroticism | 58.4 (.71)** | 56.3 (.18) | 56.8 (.21) | 56.7 (.32) |

| Extraversion | 47.0 (.67) | 48.2 (.17) | 48.3 (.20) | 48.8 (.30) |

| Openness | 47.3 (.69) | 46.6 (.17) | 46.1 (.20) | 46.5 (.31) |

| Agreeableness | 49.7 (.70) | 48.9 (.17) | 48.7 (.21) | 48.6 (.32) |

| Conscientiousness | 51.7 (.76) | 51.3 (.19) | 50.7 (.22)*^ | 50.4 (.34)*^ |

| N1: Anxiety | 58.2 (.70)* | 56.7 (.17) | 57.4 (.21)*^ | 57.1 (.31)^ |

| N2: Angry Hostility | 55.5 (.76)** | 53.5 (.19) | 54.0 (.22)^ | 54.6 (.34)**^ |

| N3: Depression | 56.2 (.75)* | 54.6 (.19) | 55.0 (.22) | 55.0 (.34) |

| N4: Self-consciousness | 53.6 (.81) | 52.3 (.20) | 52.9 (.24) | 52.3 (.36) |

| N5: Impulsiveness | 45.7 (.71) | 47.0 (.18) | 48.7 (.21)***^ | 50.1 (.32)***^ |

| N6: Vulnerability | 59.1 (.83)* | 57.0 (.21) | 57.4 (.25) | 57.2 (.37) |

| E1: Warmth | 47.1 (.76) | 48.3 (.19) | 47.9 (.22) | 48.3 (.34) |

| E2: Gregariousness | 54.9 (.77) | 54.7 (.19) | 54.3 (.23) | 54.2 (.34) |

| E3: Assertiveness | 46.6 (.65) | 47.3 (.16) | 47.5 (.19) | 48.2 (.29)* |

| E4: Activity | 51.5 (.69) | 52.5 (.17) | 52.0 (.20)^ | 51.8 (.31)^ |

| E5: Excitement-Seeking | 46.9 (.70) | 47.5 (.17) | 47.4 (.21) | 47.8 (.31) |

| E6: Positive Emotions | 44.5 (.81) | 45.5 (.20) | 45.3 (.24) | 45.8 (.36) |

| O1: Fantasy | 51.6 (.74) | 51.3 (.18) | 51.0 (.22) | 50.8 (.33) |

| O2: Aesthetics | 52.8 (.68) | 52.2 (.17) | 51.6 (.20)*^ | 51.9 (.31)^ |

| O3: Feelings | 47.7 (.74) | 46.3 (.18) | 46.0 (.22) | 46.3 (.33) |

| O4: Actions | 49.3 (.79) | 49.9 (.20) | 49.5 (.23) | 49.2 (.35) |

| O5: Ideas | 44.9 (.75) | 44.5 (.19) | 44.4 (.22) | 45.3 (.34) |

| O6: Values | 42.1 (.69) | 41.5 (.17) | 41.2 (.20) | 41.0 (.31) |

| A1: Trust | 41.4 (.82)* | 43.0 (.20) | 42.6 (.24) | 43.2 (.37) |

| A2: Straightforwardness | 49.0 (.77) | 47.9 (.19) | 47.3 (.23)* | 47.6 (.34) |

| A3: Altruism | 47.2 (.78) | 47.4 (.20) | 47.0 (.23) | 47.1 (.35) |

| A4: Compliance | 44.3 (.86) | 43.5 (.21) | 43.4 (.25) | 43.2 (.39) |

| A5: Modesty | 53.2 (.72) | 52.2 (.18) | 52.1 (.21) | 51.7 (.32) |

| A6: Tender-mindedness | 54.2 (.80) | 53.1 (.20) | 53.5 (.24) | 53.8 (.36) |

| C1: Competence | 41.6 (.76) | 42.7 (.19) | 42.3 (.22) | 42.0 (.34) |

| C2: Order | 48.7 (.78) | 49.0 (.20) | 48.1 (.23)**^ | 46.9 (.35)***^ |

| C3: Dutifulness | 50.3 (.76) | 50.7 (.19) | 50.3 (.22) | 50.4 (.34) |

| C4: Achievement Striving | 50.7 (.76) | 50.1 (.19) | 49.7 (.22) | 50.2 (.34) |

| C5: Self-Discipline | 47.9 (.73) | 48.6 (.18) | 47.7 (.22)**^ | 47.3 (.33)**^ |

| C6: Deliberation | 55.7 (.86) | 55.4 (.21) | 55.2 (.25) | 54.8 (.39) |

| Age (M years (SD)) | 29.2 (13) | 35.5 (15) | 49.1 (15) | 55.2 (14) |

| Sex (Female) | 87% | 66% | 44% | 55% |

Note: Adjusted means (Standard Errors) and statistical tests computed after controlling for age, age squared, sex, education, and Test Administration. The BMI categories for those younger than 18 years were age adjusted (40, 41). Wilk’s Lambda = .959, p < .001, partial η2 = .014.

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001 indicate significant differences of underweight vs. normal and of overweight and obese vs. normal.

indicate significant (p < .05) differences of overweight and obese vs. normal in the analyses that included the FTO genetic variant (n = 5,424).

The largest personality differences between BMI groups were at the facet level. In particular, Impulsiveness was associated with BMI, with the underweight showing lower and the overweight and obese higher impulsiveness (effect size almost 1/2 SD). In terms of weight, after controlling for demographics and height, those who scored in the top 10% of Impulsiveness were about 4 Kg heavier than those scoring in the lower 10% of the distribution. By comparison, the FTO genetic variant accounted for about 3Kg or 1-1,5 BMI-unit difference between homozygous groups in this Sardinian sample (13). The Impulsiveness scale effect was due to two items specific to the eating domain (“When I am having my favorite food, I tend to eat too much” and “I sometimes eat myself sick”). Self-Discipline, a facet of Conscientiousness related to the construct of impulsivity, was highest among the normal BMI group, but low among the overweight groups. Two other traits related to the broad construct of impulsivity (i.e., Excitement-Seeking, and Deliberation)(47) showed no effect. The overweight groups also scored lower on Order, slightly lower on Openness to Aesthetics and Straightforwardness, as well as higher on Anxiety, Angry Hostility, and Assertiveness. A similar pattern was found when controlling for the FTO genetic variant. Consistent with higher rates of psychopathology, the underweight group scored higher on Anxiety, Angry-Hostility, Depression, and Vulnerability, and lower on Trust.

The links between personality traits and waist and hip circumference and the waist-to-hip ratio were examined using hierarchical linear regression. Demographic variables were entered in a first step, and the 30 facets in a second step. The results presented in the left section of Table 2 indicate that the Impulsiveness and Order facets had the strongest and most consistent effects. As with BMI, impulsive and disorganized participants tended to have larger waists and hips and waist/hip ratio. Higher scores on Openness to Ideas and Assertiveness and lower scores on Openness to Actions and Self-Discipline were also associated with larger waist and hip circumference. The waist/hip ratio was lower among individuals more active, imaginative, open to action, trusting and modest. Accounting for the effect of the FTO genetic variant had little effect on the association between personality traits and these anthropometric measures. Of interest, in the FTO assessed subsample (n = 5,578), the effects of the widely replicated FTO genetic variant on waist and hip values (beta = 0.048 and 0.066) were smaller than those of Impulsiveness (beta = 0.118 and 0.138).

Table 2.

Concurrent and prospective personality predictors of waist, hip, and waist/hip ratio

| Cross-sectional Beta (n=5,694) | 3-year longitudinal Beta (n=4,799) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Waist | Hip | Waist/hip | Waist | Hip | Waist/hip | |

| Age | 1.068***^ | 1.024***^ | .738***^ | .986***^ | .899***^ | .705*** |

| Age squared | -.643***^ | -.776***^ | -.326***^ | -.633***^ | -.763***^ | -.323*** |

| Sex (Female) | -.346***^ | .037* | -.520***^ | -.417***^ | .019 | -.578*** |

| Education | -.141***^ | -.081***^ | -.135***^ | -.122***^ | -.128***^ | -.074*** |

| Test Administration | -.056***^ | -.073***^ | -.021 | -.032* | -.054** | -.007 |

| FTO-rs8050136 | .048^ | .066^ | -.016 | .041^ | .046^ | .020^ |

| N1: Anxiety | .001 | .029 | -.018 | .003 | .015 | -.002 |

| N2: Angry Hostility | -.010 | -.003 | -.017 | .026 | .024 | .015 |

| N3: Depression | .005 | -.021 | .026 | .008 | -.019 | .023 |

| N4: Self-consciousness | -.019 | -.020 | -.012 | -.010 | -.010 | -.005 |

| N5: Impulsiveness | .116***^ | .138***^ | .057***^ | .112***^ | .140***^ | .049***^ |

| N6: Vulnerability | -.016 | -.037*^ | .004 | -.039*^ | -.032 | -.031* |

| E1: Warmth | -.008 | -.009 | -.002 | .015 | .020 | .005 |

| E2: Gregariousness | .014 | -.013 | .026*^ | .001 | -.006 | .004 |

| E3: Assertiveness | .038**^ | .039*^ | .022^ | .028^ | .039*^ | .010 |

| E4: Activity | -.023^ | .003 | -.032**^ | -.016 | -.001 | -.020 |

| E5: Excitement-Seeking | -.020 | -.024 | -.009 | -.017 | -.024 | -.006 |

| E6: Positive Emotions | .009 | -.007 | .018 | .024 | .006 | .028*^ |

| O1: Fantasy | -.038**^ | -.029 | -.031**^ | -.032* | -.030 | -.021 |

| O2: Aesthetics | -.023 | -.026 | -.012 | -.020 | -.030 | -.006 |

| O3: Feelings | -.019 | -.025 | -.009 | -.046**^ | -.051**^ | -.023 |

| O4: Actions | -.035**^ | -.034*^ | -.021* | -.015 | -.021 | -.005 |

| O5: Ideas | .051***^ | .063***^ | .020 | .051***^ | .064***^ | .020 |

| O6: Values | -.015 | -.023 | -.003 | -.025^ | -.019 | -.020 |

| A1 : Trust | -.020 | -.005 | -.025*^ | -.016 | -.008 | -.015^ |

| A2: Straightforwardness | -.005 | -.015 | .003 | .011 | .000 | .014 |

| A3: Altruism | -.001 | .006 | -.006 | -.011 | -.008 | -.009 |

| A4: Compliance | .013 | .033*^ | -.008 | .015 | .046**^ | -.012 |

| A5: Modesty | -.013 | .007 | -.027*^ | -.016 | -.017 | -.010 |

| A6: Tender-mindedness | .021 | .019 | .016 | .017 | .018 | .009 |

| C1: Competence | .007 | .013 | .000 | .007 | -.008 | .015 |

| C2: Order | -.039***^ | -.042**^ | -.023*^ | -.047***^ | -.051**^ | -.027*^ |

| C3: Dutifulness | .013 | .025 | -.001 | .028 | .044*^ | .005 |

| C4: Achievement Striving | .007 | .009 | .002 | -.008 | .016 | -.022 |

| C5: Self-Discipline | -.033*^ | -.034* | -.024 | -.026 | -.041* | -.005 |

| C6: Deliberation | .012 | .020 | .002 | .020 | .035 | .000 |

Note.

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001.

indicate variables that were significant predictors (p < .05) in the cross-sectional (n = 5,578) and longitudinal (n = 4,511) analyses that included the FTO genetic variant.

Prospective personality predictors

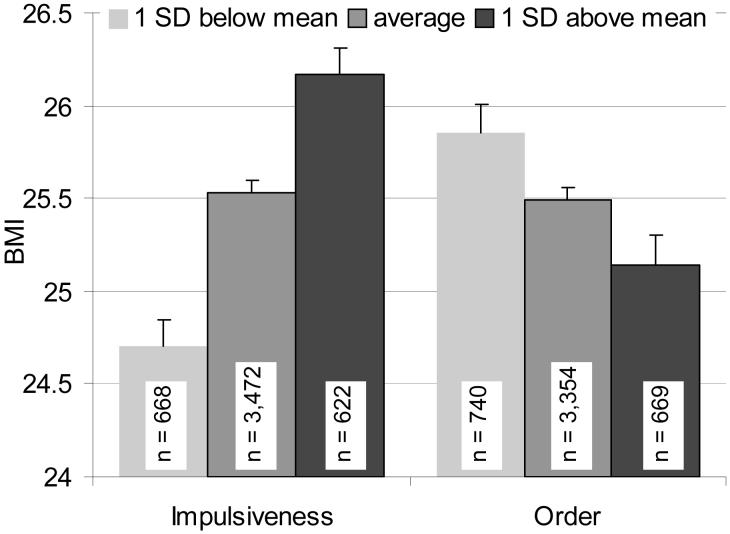

Longitudinal analyses1 examined whether personality traits were predictors of BMI and measures of central adiposity three years later, accounting for the effects of demographic variables. Results of logistic regressions are reported in Table 3. Low Impulsiveness and high Openness to Feelings predicted being underweight three years later. A larger number of facets (e.g., Vulnerability, Openness to Aesthetics and Ideas) predicted overweight and obesity three years later. As with the concurrent analyses, the Impulsiveness facet was the strongest longitudinal predictor, with Order to a lesser extent (see Figure 1). The odds ratio for Impulsiveness (OR = 1.036) indicates a 3.6% risk increase for each T-score unit increase. A difference of 10 T-score points (1 SD) corresponds to a 42% risk of being overweight or obese (by raising odds ratios to a power equal to the standard deviation (10)). In terms of weight, prospective analyses confirmed that those who scored in the top 10% of Impulsiveness were about 4 Kg heavier than those scoring in the lower 10% of the distribution. The personality predictors of overweight and obesity were mostly unchanged when we added the FTO genetic variant (n = 4,555) to the first step of the logistic regression.

Table 3.

Personality predictors of underweight, overweight and obesity three years later

| Underweight (n = 143) vs. normal (n = 2,228) | Overweight and obese (n = 2,394) vs. normal (n = 2,228) | |

|---|---|---|

| OR (95%CI) | OR (95%CI) | |

| Age | 0.903 (0.827_0.987)* | 1.195 (1.161_1.231)***^ |

| Age squared | 1.001 (0.999_1.002) | 0.999 (0.998_0.999)***^ |

| Sex (Female) | 5.227 (2.787_9.805)*** | 0.361 (0.304_0.427)***^ |

| Education | 0.991 (0.757_1.297) | 0.696 (0.634_0.766)***^ |

| Test Administration | 0.783 (0.129_4.761) | 0.754 (0.539_1.057) |

| FTO-rs8050136 | 1.130 (1.012_1.262)^ | |

| N1: Anxiety | 0.995 (0.970_1.022) | 1.005 (0.994_1.015) |

| N2: Angry Hostility | 1.008 (0.983_1.035) | 1.009 (0.999_1.019) |

| N3: Depression | 1.002 (0.974_1.031) | 0.999 (0.988_1.010) |

| N4: Self-consciousness | 0.979 (0.957_1.002) | 0.997 (0.988_1.007) |

| N5: Impulsiveness | 0.972 (0.948_0.996)* | 1.036 (1.026_1.046)***^ |

| N6: Vulnerability | 1.012 (0.989_1.036) | 0.991 (0.981_1.000)* |

| E1: Warmth | 0.985 (0.959_1.012) | 1.005 (0.994_1.015) |

| E2: Gregariousness | 0.996 (0.974_1.019) | 0.995 (0.986_1.004) |

| E3: Assertiveness | 0.991 (0.963_1.020) | 1.007 (0.996_1.019) |

| E4: Activity | 0.987 (0.963_1.012) | 0.994 (0.984_1.003) |

| E5: Excitement-Seeking | 1.005 (0.981_1.029) | 0.992 (0.982_1.001) |

| E6: Positive Emotions | 1.000 (0.977_1.023) | 0.999 (0.990_1.008) |

| O1: Fantasy | 0.990 (0.968_1.012) | 0.989 (0.980_0.998)*^ |

| O2: Aesthetics | 1.008 (0.983_1.033) | 0.989 (0.980_0.999)*^ |

| O3: Feelings | 1.028 (1.003_1.054)* | 0.994 (0.985_1.003) |

| O4: Actions | 0.998 (0.977_1.019) | 1.000 (0.992_1.008) |

| O5: Ideas | 1.005 (0.982_1.028) | 1.013 (1.003_1.022)**^ |

| O6: Values | 1.003 (0.981_1.026) | 0.995 (0.986_1.003) |

| A1: Trust | 0.991 (0.972_1.011) | 0.998 (0.990_1.006) |

| A2: Straightforwardness | 0.993 (0.971_1.015) | 0.997 (0.988_1.006) |

| A3: Altruism | 0.994 (0.971_1.018) | 1.002 (0.993_1.011) |

| A4: Compliance | 1.011 (0.990_1.032) | 1.008 (1.000_1.016)*^ |

| A5: Modesty | 1.011 (0.989_1.034) | 0.996 (0.988_1.005) |

| A6: Tender-mindedness | 1.001 (0.980_1.022) | 1.003 (0.995_1.011) |

| C1: Competence | 1.005 (0.980_1.031) | 1.000 (0.991_1.010) |

| C2: Order | 0.984 (0.964_1.005) | 0.986 (0.978_0.995)**^ |

| C3: Dutifulness | 1.006 (0.981_1.030) | 1.011 (1.001_1.021)*^ |

| C4: Achievement Striving | 1.013 (0.987_1.040) | 1.002 (0.992_1.012) |

| C5: Self-Discipline | 0.986 (0.960_1.014) | 1.000 (0.989_1.012) |

| C6: Deliberation | 1.008 (0.988_1.028) | 1.004 (0.995_1.012) |

Note. Demographic variables entered in step 1 and personality (assessed three years before the outcome variable) in step 2.

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001.

indicates that the finding holds controlling for the FTO genetic variant (n = 4,555).

Figure 1.

Groups scoring ± 1 SD on Impulsiveness and Order predicting BMI three years later.

Notes. Estimated marginal means after controlling for demographic variables. Error bars are standard errors.

Longitudinal personality predictors of waist and hip circumference and waist-to-hip ratio are reported in the right section of Table 2. As with the cross-sectional analyses, Impulsiveness was the strongest predictor of these measures of central adiposity. Other predictors were Order and Openness to Ideas and Feelings. The results were essentially unchanged when the FTO genetic variant was included. The effect sizes of Impulsiveness and Order, even after three years, were larger than the effect sizes of the FTO genetic variant.

Discussion

From a sample that represents over half of a population from four towns in Sardinia, Italy, we have anthropometric data measured by trained professionals and we tested for its association with a comprehensive set of FFM personality traits. We found similar associations in concurrent and prospective analyses, and across general and central measures of adiposity. In contrast to a previous study that reported sex-specific links between personality and obesity (16), similar associations emerged for women and men.

Consistent with the higher prevalence of psychopathology among underweight individuals (22), we found that they scored higher on Neuroticism, a major risk factor for mental health disorders (48). Among the facets of Neuroticism, underweight individuals tend to be particularly anxious, vulnerable, depressed, angry and hostile. Contrary to the pattern found for the other facets of Neuroticism, underweight individuals tend to score low on Impulsiveness, an effect due to items related to eating behaviors. Low Impulsiveness was a predictor of underweight three years after the personality assessment, and seems consistent with the overly stringent control on food consumption. This finding is also consistent with previous clinical studies that found restrictive anorexia nervosa patients to score lower on Impulsiveness (49).

Impulsiveness was the strongest predictor of BMI at the other end of the spectrum, a finding consistent with many previous studies that have assessed this trait (14, 15, 50). Both cross-sectional and longitudinal data indicate that overweight and obese individuals are characterized by lack of control and inability to resist temptations and cravings. This effect was found for the BMI categories, and confirmed with measures of waist and hip circumference. In addition, the cross-sectional analysis suggests that low self-discipline, a Conscientiousness trait related to the impulsivity construct, is associated with obesity. The self-discipline scale measures the ability to stay on a task, perseverant and resolute in front of difficulties or boredom, all traits relevant for a controlled diet and sustained physical activity.

Albeit smaller in magnitude, Order, a facet of Conscientiousness, shows a similar, remarkably consistent association across different anthropometric measures (BMI, waist and hip circumference) in concurrent and prospective analyses, and after the analytical model accounted for the FTO genetic variant. Individuals high on Order are organized and methodical, therefore it might be natural to them to adhere to exercise routines, a healthy diet, and regular meal rhythms, while avoiding unplanned food consumption and over-eating - all key behaviors for weight maintenance (51).

Consistent with previous studies (7, 16), at the factor level, we found lower Conscientiousness among overweight and obese groups. Conscientiousness has been linked to longevity (30, 38, 39), and has emerged as an important trait in health-related behaviors (52, 53), including physical activity (37, 54), HIV/AIDS risk behaviors (33), and the use of tobacco and other drugs (32).

We note several limitations of the current research. First, the sample is not strictly representative of the population, but we did assess over 62% of the residents from the four towns targeted. Other findings from this sample have been replicated in different populations (e.g., 12, 13). Second, we used several anthropometric measures to overcome the limitations of using a single anthropometric measure (e.g., BMI is a biased indicator for athletes). The measures of abdominal adiposity are increasingly recognized as a stronger predictor of health outcomes (3, 34), and this is the first large study that linked personality traits to general and central obesity indicators. Although we consider this a strength, the large number of statistical tests increases the chance of false positives. We focus, however, on the larger effect sizes that replicated across anthropometric measures and concurrent and prospective analyses. Third, the FTO genetic variant is only one of many biological factors that influence this quantitative trait, but we did not examine others. We also did not examine potential direct and meditational effects of dietary intake and physical activity. Finally, we adopted the perspective that personality traits influence anthropometric values in our prospective analyses, but it is possible that being obese or underweight might in turn influence personality traits, or that there are reciprocal influences.

Together with social and genetic factors (10), individual differences contribute to the etiology of both obesity and underweight. Assessing the personality profile of those from one BMI extreme to the other reveals the traits that increase risk. Identifying such traits not only helps to understand the etiology of the problems, but can suggest points of intervention and help tailor prevention and treatment strategies to groups at greater risk. For example, treatments that stress the importance of regular meal schedules, menu planning, and avoidance of impulsive snacking and over-eating may be particularly effective for individuals low in Order or high in Impulsiveness. Behavioral modification programs based on these principles might produce long-lasting behavioral changes that encourage weight maintenance for individuals with these traits. In addition, personality traits are associated with successful therapy-induced weight loss (17), and knowledge of the patients’ character can contribute to differential treatment planning (55). Personality traits are related to different preferences for exercise setting, motives, and barriers (54), and interventions that take into account such individual differences might achieve better treatment outcomes. For example, extroverts may find lifestyle and exercise change easier if it is done in group settings (54), and the presence of others may have an impact on food intake (56).

The personality profile of the overweight groups (impulsive, not conscientious) suggests that interventions at the individual level may require extensive resources and may have limited success. From a public health perspective, interventions at the societal level can be more effective in reaching the largest number of people. For example, for cigarette smokers, who are also low on Conscientiousness and high on impulsivity (35), tax increases have been a cost-effective intervention to reduce the prevalence of smoking (57, 58). Similar tax increases on sugary drinks and other “junk food” may likewise be an effective tool to face the current obesogenic epidemic, especially among younger and lower socioeconomic groups.

Differences of up to four Kg, although clinically meaningful, admittedly account for a relatively small amount of variance in body weight. Individual differences are surely not the cause of the recent increase in obesity prevalence around the world; clearly the social and economical factors driving these secular trends are the major points of intervention. But even in the current obesogenic epidemic, some individuals are at higher risk than others. Given the prevalence of obesity world-wide and its association with increased risk of diseases, even small improvements can have considerable public health impact.

Acknowledgments

We thank the individuals who participated in this study; The SardiNIA team thanks Monsignore Piseddu (Bishop of Ogliastra), the mayors of the four Sardinian towns (Lanusei, Ilbono, Arzana and Elini), and the head of the Public Health Unit ASL4 for cooperation. We thank Prof. Antonio Cao for his leadership of the SardiNIA project.

This research was supported entirely by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Institute on Aging. Robert R. McCrae and Paul T. Costa, Jr., receive royalties from the Revised NEO Personality Inventory.

The authors declare that they have no other potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

- BMI

body mass index

- SNP

Single Nucleotide Polymorphism

- FFM

Five Factor Model

- N

Neuroticism

- E

Extraversion

- O

Openness to Experience

- A

Agreeableness

- C

Conscientiousness

- NEO-PI-R

Revised NEO Personality Inventory

- CI

confidence interval

- OR

odds ratio

- SD

Standard Deviation

Footnotes

Preliminary analyses suggested that personality traits were mostly unrelated to changes in BMI over the three years period, except for an association of BMI increases with low Competence (a facet of Conscientiousness; p = .01). BMI was highly stable over the 3-year interval (r = .93).

References

- 1.Mokdad AH, Marks JS, Stroup DF, Gerberding JL. Actual causes of death in the United States, 2000. Jama. 2004;291:1238–45. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.10.1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kelly T, Yang W, Chen CS, Reynolds K, He J. Global burden of obesity in 2005 and projections to 2030. Int J Obes (Lond) 2008;32:1431–7. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2008.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yusuf S, Hawken S, Ounpuu S, Bautista L, Franzosi MG, Commerford P, Lang CC, Rumboldt Z, Onen CL, Lisheng L, Tanomsup S, Wangai P, Jr., Razak F, Sharma AM, Anand SS. Obesity and the risk of myocardial infarction in 27,000 participants from 52 countries: a case-control study. Lancet. 2005;366:1640–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67663-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Calle EE, Rodriguez C, Walker-Thurmond K, Thun MJ. Overweight, obesity, and mortality from cancer in a prospectively studied cohort of U.S. adults. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1625–38. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Flegal KM, Graubard BI, Williamson DF, Gail MH. Excess deaths associated with underweight, overweight, and obesity. Jama. 2005;293:1861–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.15.1861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yach D, Stuckler D, Brownell KD. Epidemiologic and economic consequences of the global epidemics of obesity and diabetes. Nat Med. 2006;12:62–6. doi: 10.1038/nm0106-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roehling MV, Roehling PV, Odland LM. Investigating the Validity of Stereotypes About Overweight Employees: The Relationship Between Body Weight and Normal Personality Traits. Group Organization Management. 2008;33:392–424. [Google Scholar]

- 8.French SA, Story M, Jeffery RW. Environmental influences on eating and physical activity. Annu Rev Public Health. 2001;22:309–35. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.22.1.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, McDowell MA, Tabak CJ, Flegal KM. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in the United States, 1999-2004. JAMA. 2006;295:1549–55. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.13.1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wardle J, Carnell S, Haworth CM, Plomin R. Evidence for a strong genetic influence on childhood adiposity despite the force of the obesogenic environment. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;87:398–404. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/87.2.398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pilia G, Chen WM, Scuteri A, Orrú M, Albai G, Dei M, Lai S, Usala L, Lai M, Loi P, Mameli C, Vacca L, Deiana M, Masala M, Cao A, Najjar SS, Terracciano A, Nedorezov T, Sharov A, Zonderman AB, Abecasis G, Costa PT, Lakatta E, Schlessinger D. Heritability of Cardiovascular and Personality Traits in 6,148 Sardinians. PloS Genetics. 2006;2:e132. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frayling TM, Timpson NJ, Weedon MN, Zeggini E, Freathy RM, Lindgren CM, Perry JR, Elliott KS, Lango H, Rayner NW, Shields B, Harries LW, Barrett JC, Ellard S, Groves CJ, Knight B, Patch AM, Ness AR, Ebrahim S, Lawlor DA, Ring SM, Ben-Shlomo Y, Jarvelin MR, Sovio U, Bennett AJ, Melzer D, Ferrucci L, Loos RJ, Barroso I, Wareham NJ, Karpe F, Owen KR, Cardon LR, Walker M, Hitman GA, Palmer CN, Doney AS, Morris AD, Smith GD, Hattersley AT, McCarthy MI. A common variant in the FTO gene is associated with body mass index and predisposes to childhood and adult obesity. Science. 2007;316:889–94. doi: 10.1126/science.1141634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scuteri A, Sanna S, Chen WM, Uda M, Albai G, Strait J, Najjar S, Nagaraja R, Orru M, Usala G, Dei M, Lai S, Maschio A, Busonero F, Mulas A, Ehret GB, Fink AA, Weder AB, Cooper RS, Galan P, Chakravarti A, Schlessinger D, Cao A, Lakatta E, Abecasis GR. Genome-wide association scan shows genetic variants in the FTO gene are associated with obesity-related traits. PLoS Genet. 2007;3:e115. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ryden A, Sullivan M, Torgerson JS, Karlsson J, Lindroos AK, Taft C. Severe obesity and personality: a comparative controlled study of personality traits. Int J Obes. 2003;27:1534–40. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ryden A, Sullivan M, Torgerson JS, Karlsson J, Lindroos AK, Taft C. A comparative controlled study of personality in severe obesity: a 2-y follow-up after intervention. Int J Obes. 2004;28:1485–93. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brummett BH, Babyak MA, Williams RB, Barefoot JC, Costa PTJ, Siegler IC. NEO personality domains and gender predict levels and trends in body mass index over 14 years during midlife. Journal of Research in Personality. 2006;40:222–36. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sullivan S, Cloninger CR, Przybeck TR, Klein S. Personality characteristics in obesity and relationship with successful weight loss. Int J Obes (Lond) 2007;31:669–74. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kakizaki M, Kuriyama S, Sato Y, Shimazu T, Matsuda-Ohmori K, Nakaya N, Fukao A, Fukudo S, Tsuji I. Personality and body mass index: a cross-sectional analysis from the Miyagi Cohort Study. J Psychosom Res. 2008;64:71–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rossier V, Bolognini M, Plancherel B, Halfon O. Sensation seeking: A personality trait characteristic of adolescent girls and young women with eating disorders? European Eating Disorders Review. 2000;8:245–52. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bulik CM, Sullivan PF, Tozzi F, Furberg H, Lichtenstein P, Pedersen NL. Prevalence, heritability, and prospective risk factors for anorexia nervosa. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:305–12. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.3.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cassin SE, von Ranson KM. Personality and eating disorders: a decade in review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2005;25:895–916. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Petry NM, Barry D, Pietrzak RH, Wagner JA. Overweight and obesity are associated with psychiatric disorders: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Psychosom Med. 2008;70:288–97. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181651651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mather AA, Cox BJ, Enns MW, Sareen J. Associations Between Body Weight and Personality Disorders in a Nationally Representative Sample. Psychosom Med. 2008;70:1012–9. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e318189a930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Costa PT, Jr., McCrae RR. Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PI-R) and NEO Five-Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI) professional manual. Psychological Assessment Resources; Odessa, FL: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 25.McCrae RR, Terracciano A. 78 Members of the Personality Profiles of Cultures Project. Universal features of personality traits from the observer’s perspective: Data from 50 cultures. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2005;88:547–61. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.88.3.547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jang KL, McCrae RR, Angleitner A, Riemann R, Livesley WJ. Heritability of facet-level traits in a cross-cultural twin sample: Support for a hierarchical model of personality. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;74:1556–65. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.74.6.1556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Terracciano A, McCrae RR, Brant LJ, Costa PT., Jr. Hierarchical linear modeling analyses of NEO-PI-R scales in the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. Psychology and Aging. 2005;20:493–506. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.20.3.493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Costa PT, Jr., Terracciano A, McCrae RR. Gender differences in personality traits across cultures: Robust and surprising findings. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2001;81:322–31. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.81.2.322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Paunonen SV, Haddock G, Forsterling F, Keinonen M. Broad versus narrow personality measures and the prediction of behaviour across cultures. European Journal of Personality. 2003;17:413–33. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Terracciano A, Lockenhoff CE, Zonderman AB, Ferrucci L, Costa PT., Jr. Personality predictors of longevity: activity, emotional stability, and conscientiousness. Psychosom Med. 2008;70:621–7. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31817b9371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Paunonen SV, Ashton MC. Big five factors and facets and the prediction of behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2001;81:524–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Terracciano A, Lockenhoff CE, Crum RM, Bienvenu OJ, Costa PT., Jr. Five-Factor Model personality profiles of drug users. BMC Psychiatry. 2008;8:22. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-8-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Trobst KK, Herbst JH, Masters HL, III, Costa PT., Jr. Personality pathways to unsafe sex: Personality, condom use, and HIV risk behaviors. Journal of Research in Personality. 2002;36:117–33. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Janssen I, Katzmarzyk PT, Ross R. Waist circumference and not body mass index explains obesity-related health risk. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;79:379–84. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/79.3.379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Terracciano A, Costa PT., Jr. Smoking and the Five-Factor Model of personality. Addiction. 2004;99:472–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00687.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Trobst KK, Wiggins JS, Costa PT, Jr., Herbst JH, McCrae RR, Masters HL. Personality psychology and problem behaviors: HIV risk and the five-factor model. Journal of Personality. 2000;68:1233–52. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.00133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rhodes RE, Smith NE. Personality correlates of physical activity: a review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2006;40:958–65. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2006.028860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Martin LR, Friedman HS, Schwartz JE. Personality and mortality risk across the life span: the importance of conscientiousness as a biopsychosocial attribute. Health Psychol. 2007;26:428–36. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.26.4.428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wilson RS, Mendes de Leon CF, Bienias JL, Evans DA, Bennett DA. Personality and mortality in old age. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2004;59:P110–6. doi: 10.1093/geronb/59.3.p110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cole TJ, Bellizzi MC, Flegal KM, Dietz WH. Establishing a standard definition for child overweight and obesity worldwide: international survey. BMJ. 2000;320:1240–3. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7244.1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.CDC 2000 http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/about/major/nhanes/growthcharts/clinical_charts.htm.

- 42.Terracciano A. The Italian version of the NEO PI-R: conceptual and empirical support for the use of targeted rotation. Personality and Individual Differences. 2003;35:1859–72. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(03)00035-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Terracciano A, Sanna S, Uda M, Deiana B, Usala G, Busonero F, Maschio A, Scally M, Patriciu N, Chen WM, Distel MA, Slagboom EP, Boomsma DI, Villafuerte S, Sliwerska E, Burmeister M, Amin N, Janssens AC, van Duijn CM, Schlessinger D, Abecasis GR, Costa PT., Jr. Genome-wide association scan for five major dimensions of personality. Mol Psychiatry. 2008 doi: 10.1038/mp.2008.113. doi: 10.1038/mp.2008.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Terracciano A, Costa PTJ, McCrae RR. Personality plasticity after age 30. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2006;32:999–1009. doi: 10.1177/0146167206288599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McCrae RR, Costa PT., Jr. Personality in adulthood: A Five-Factor Theory perspective. 2nd ed. Guilford Press; New York: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Costa PT, Jr., Terracciano A, Uda M, Vacca L, Mameli C, Pilia G, Zonderman AB, Lakatta E, Schlessinger D, McCrae RR. Personality traits in Sardinia: testing founder population effects on trait means and variances. Behav Genet. 2007;37:376–87. doi: 10.1007/s10519-006-9103-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Whiteside SP, Lynam DR. The Five Factor Model and impulsivity: using a structural model of personality to understand impulsivity. Personality and Individual Differences. 2001;30:669–89. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kendler KS, Neale MC, Kessler RC, Heath AC, Eaves LJ. A longitudinal twin study of personality and major depression in women. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1993;50:853–62. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820230023002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Claes L, Vandereycken W, Vertommen H. Impulsivity-related traits in eating disorder patients. Personality and Individual Differences. 2005;39:739–49. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Elfhag K, Morey LC. Personality traits and eating behavior in the obese: poor self-control in emotional and external eating but personality assets in restrained eating. Eat Behav. 2008;9:285–93. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2007.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Elfhag K, Rossner S. Who succeeds in maintaining weight loss? A conceptual review of factors associated with weight loss maintenance and weight regain. Obes Rev. 2005;6:67–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2005.00170.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Booth-Kewley S, Vickers RRJ. Associations between major domains of personality and health behavior. Journal of Personality. 1994;62:281–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1994.tb00298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vollrath M, Torgersen S. Who takes health risks? A probe into eight personality types. Personality and Individual Differences. 2002;32:1185–97. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Courneya KS, Hellsten L-M. Personality correlates of exercise behavior, motives, barriers and preferences: An application of the five-factor model. Personality and Individual Differences. 1998;24:625–33. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sanderson C, Clarkin JF. Further use of the NEO-PI-R personality dimensions in differential treatment planning. In: Costa PT Jr., Widiger TA, editors. Personality disorders and the five-factor model of personality. 2nd ed. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 2002. pp. 351–75. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Herman CP, Roth DA, Polivy J. Effects of the presence of others on food intake: a normative interpretation. Psychol Bull. 2003;129:873–86. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.6.873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Frieden TR, Mostashari F, Kerker BD, Miller N, Hajat A, Frankel M. Adult tobacco use levels after intensive tobacco control measures: New York City, 2002-2003. Am J Public Health. 2005;95:1016–23. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.058164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Townsend J, Roderick P, Cooper J. Cigarette smoking by socioeconomic group, sex, and age: effects of price, income, and health publicity. BMJ. 1994;309:923–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.309.6959.923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]