Abstract

The backbone dynamics for the 29.5 kDa class A β-lactamase PSE-4 is presented. This solution NMR study was performed using multiple field 15N spin relaxation and amide exchange data in the EX2 regime. Analysis was carried out with the relax program and includes the Lipari-Szabo model-free approach. Showing similarity to the homologous enzyme TEM-1, PSE-4 is very rigid on the ps-ns timescale, although slower μs-ms motions are present for several residues; this is especially true near the active site. However, significant dynamics differences exist between the two homologs for several important residues. Moreover, our data support the presence of a motion of the Ω loop first detected using molecular dynamics simulations on TEM-1. Thus, class A β-lactamases appear to be a class of highly ordered proteins on the ps-ns timescale despite their efficient catalytic activity and high plasticity toward several different β-lactam antibiotics. Most importantly, catalytically relevant μs-ms motions are present in the active site, suggesting an important role in catalysis.

Introduction

The main resistance mechanism against penicillin-derived molecules (the β-lactams) is the production of enzymes, the β-lactamases, able to cleave the four-membered β-lactam ring (1). Enzymes from class A are the most often found (2), representing a diverse class of proteins in terms of substrate specificity. Moreover, these 30 kDa enzymes are highly effective catalysts, some with a diffusion-controlled specific activity (3).

Class A β-lactamases general mechanism is composed of two steps akin to that of serine proteinases (4). First, catalytic Ser70 makes a nucleophilic attack on the carbonyl of the β-lactam ring. This leads to the hydrolysis of the β-lactam ring after acylation to the protein (1). The process is similar when β-lactam antibiotics inactivate their target, ending up in an inactive acyl-enzyme complex that stops bacterial cell growth and leads to cell death. The second step, a deacylation, which is virtually absent for DD-transpeptidases, consists of a nucleophilic attack by a H2O molecule activated by the conserved residue Glu166, part of the Ω loop (Arg161 to Asp179) (1). This leads to the hydrolysis of the acyl-enzyme complex and release of the hydrolyzed β-lactam.

To attack the β-lactam ring, the catalytic Ser70 must have its hydroxyl proton accepted by a general base. The identity of this activator is, however, controversial. One hypothesis involves Lys73 as the general base whereas another involves Glu166 (1). Other studies proposed the involvement of Ser130 (5). A new model has emerged recently in which a duality of mechanisms was shown for tetrahedral formation (6), meaning that the activation process could depend on the β-lactamase/β-lactam combination. A deeper understanding of the structure/function relationship in β-lactamases may help in validating and reinforcing this hypothesis. More specifically, the knowledge of the motions arising in these proteins, especially near the active site, should provide a better mechanistic understanding and complement structural data. Several molecular dynamics (MD) studies have been performed to get insights into the function/structure/dynamics link of class A β-lactamases. These studies have focused on TEM-1.

NMR is a powerful tool for the study of protein dynamics. It allows atom-specific data to be gathered for movements as fast as side-chain rotations or hydrogen-bond formation, and as slow as protein folding. Studying movements of N-H bonds provides a specific probe for almost all residues. 15N spin relaxation rates depend mainly on the N-H bond reorientations with respect to the external magnetic field as a function of time (7), allowing the study of the information-rich ps-ns and μs-ms timescales. It is known that motions arising on the ps-ns timescale influence the thermodynamics of ligand binding, as well as the kinetics of catalyzed reactions (8). Moreover, motions on the μs-ms timescale are directly linked to enzyme catalysis (9).

As of today, only one class A β-lactamase, TEM-1, has had its backbone dynamics characterized by NMR. TEM-1 is the model enzyme for traditional class A β-lactamases. Savard and Gagné (10) demonstrated that TEM-1 is a very rigid protein on the ps-ns timescale. This rigidity is especially important near the active site, presuming that substrate binding should not trigger any important unfavorable loss in conformational entropy. In addition, μs-ms motions were observed around the active site and Ω loop. Further insights into TEM-1 dynamics were obtained by a study on the comparative dynamics of the wild-type enzyme with the mutant Tyr105Asp (11). It was shown that this single point mutation could have long-range effects on the dynamics of the protein.

Here, we add to these two studies by presenting the backbone dynamics of the carbenicillin hydrolyzing class A β-lactamase PSE-4 as obtained by NMR. PSE-4 enzyme was originally found in Pseudomonas aeruginosa (12), an opportunistic pathogen, but was soon found in nonpseudomonal strains (13). It is the model enzyme for the subclass of carbenicillin hydrolyzing class A β-lactamases. The crystal structure of this 271-residue protein (29.5 kDa) was determined previously (14). Besides PSE-4 having a high sequence identity with TEM-1 (41.5%), its structure (composed of two domains: an all α- and an α/β domain) is also very close to that of TEM-1 with a backbone RMSD of 1.3 Å.

We supply data on PSE-4 dynamics from amide exchange as well as 15N spin relaxation data analyzed using the Lipari-Szabo model-free approach (15,16). Additionally, the assessment of data sets consistency, a prerequisite for multiple field data analysis, is discussed in the context of the data presented in this work.

Methods

NMR data acquisition

15N-labeled PSE-4 was produced as described previously (17). NMR samples were as follows: 0.5 mM PSE-4, 10% D2O, 3 mM imidazole, and 0.1% sodium azide at pH 6.65. Chemical shift referencing was performed externally using a sample of 0.4 mM 2,2-dimethyl-2-silapentane-5-sulfonic acid (DSS) in 10% D2O. Spectra were acquired at a temperature of 31.5°C (calibrated using MeOH) on a Varian INOVA 600 (in-house), and Varian INOVA 500 and 800 (Québec/Eastern Canada High Field NMR Facility, Montréal, Canada) spectrometers (corresponding to 60.8, 50.6, and 81.0 MHz nitrogen frequency, respectively) equipped with z axis, pulsed-field gradient, triple-resonance cold probes (except for amide exchange data at pH 7.85, which was acquired using a room temperature probe).

Measurement of longitudinal (R1) and transversal (R2) relaxation rates as well as the steady-state heteronuclear nuclear Overhauser effect (NOE) proceeded with established pulse sequences (18,19). Details are available in the Supporting Material. For both R1 and R2 experiments, acquisition of relaxation data was made in an interleaved manner to prevent the effects of field and sample inhomogeneity as a function of time (20). NOEs were made in duplicate at 50.6 MHz. At 60.8 MHz, R1 experiments were made in quadruplicate, R2, in quintuplicate, and NOE, in triplicate, with some experiments recorded before and others after the recording of data at 50.6 and 81.0 MHz. This ensured that the sample was in the same state throughout the complete experimental scheme.

Amide exchange experiments proceeded from TROSY-HSQC spectra (BioPack, Varian, Palo Alto, CA) of lyophilized PSE-4 dissolved in D2O. The TROSY implementation allowed smaller phase cycling so very short spectra could be acquired with limited baseline distortions. At the beginning, more frequent short spectra (with a low number of transients) were acquired, and at the end, fewer long spectra (with increasing transients) were acquired. To determine the exchange regime, amide exchange experiments were performed for 80 days at pH 6.65, and for six days at pH 7.85. In both situations, 60 spectra were recorded. Details can be found in the Supporting Material.

NMR data processing

NMR data were processed using the program NMRPipe (21). Details are available in the Supporting Material. Peak deconvolution proceeded using the macro nlinLS invoked from the script autoFit.tcl, both distributed within NMRPipe (21). R1 and R2, as well as amide exchange rates, were obtained with the program CURVEFIT (A. G. Palmer, Columbia University, New York, NY). Errors on these fits were obtained from either 500 Monte Carlo simulations or the Jackknife method, using the method that yielded the largest error. A correction was introduced for systematic errors not accounted for when a near-perfect fit was obtained from the R1 and R2 exponential curve-fitting. This was done only for model-free analysis where too small errors on experimental data can introduce overcomplex models. Thus, parameters with unrealistically small errors (smaller than the mean value) had their error scaled to the mean value. This is similar to what was done in Savard and Gagné (10). Finally, NOEs were calculated as the ratio of peak amplitude with and without proton saturation, and error propagation calculated from the noise.

Consistency test

Consistency between data sets acquired at different magnetic fields was assessed with the use of reduced spectral density mapping (22) within the program relax (Ver. 1.2.14) (23,24). The test consisted of calculating the field-independent function J(0) for each residue and then comparing results obtained at different fields. For these calculations, the 15N chemical shift anisotropy (CSA) was −172 ppm, and the vibrationally averaged effective N-H bond length (rN–H) was 1.02 Å.

Model-free analysis

Model-free analysis of relaxation data was performed using the program relax (Ver. 1.2.14) (23,24) with a variant of the methodology for the dual optimization of the model-free parameters and the global diffusion tensor proposed recently (24) (see Fig. S4 in the Supporting Material). To avoid any artifact (resulting from under- or overfitting), only residues for which data were available at the three magnetic fields were analyzed. N-H vectors orientations were extracted from PDB 1G68 (14). Values for the CSA and rN–H were the same as for the consistency test. This is as in Savard and Gagné (10), for comparison purposes with dynamics of the homologous protein TEM-1.

Five different diffusion tensors were tested (no global diffusion tensor with a local τm parameter for each residue, sphere, prolate spheroid, oblate spheroid, and ellipsoid). These were optimized using residues from well-defined secondary structures (determined using DSSP (25), see Table S3 in the Supporting Material) and selected by Akaike information criterion (AIC) (26). Selection of local model-free models (described in the Supporting Material) during iterations for diffusion tensor optimization was also done using AIC. This allowed the selection of complex models for residues difficult to fit, avoiding the diffusion tensor from being biased by those residues. After convergence of the different diffusion tensors and selection of that with the lowest AIC, local model-free models were minimized for all residues using this diffusion tensor, which was then held fixed. Then, the best model for each residue was selected using the small sample size-corrected (AICc) (27). This was done to minimize overfitting which could lead to overinterpretation of relaxation data. Finally, errors on the extracted local parameters were obtained by performing 500 Monte Carlo simulations. A flowchart of the model-free protocol used in this study is available in Fig. S4.

Sequence numbering

Using the Ambler numbering scheme (28), mature PSE-4 starts at residue 22 and ends, after 271 residues and three gaps (positions 58, 239, and 253), at residue 295.

Results and Discussion

Chemical shift referencing was done externally because DSS interacts weakly with PSE-4 (data not shown). In addition, samples did not contain any proteinase inhibitor cocktail because we also observed that some inhibitors bind to the active site (data not shown). Finally, no buffer was used because NMR data indicate that the phosphate buffer interacts weakly with TEM-1's active site (P.-Y. Savard and S. Gagné, personal communication, 2006), despite its ubiquitous use in many kinetics studies of β-lactamases. Therefore, samples were prepared to minimize any unwanted interaction that could bias our study because relaxation experiments are extremely sensitive.

As for the homologous TEM-1 (10), spectra were of very high quality despite PSE-4 molecular weight (Fig. S1). Backbone resonance assignments for PSE-4 (BMRB No. 6838) (17) allowed for the extraction of atom-specific data. Hence, no information could be extracted for residues Ser22, Ser23, Ser24, Ser70, and Ala237 for which assignments are unavailable; Ser22, Ser23, and Ser24, probably because of fast solvent exchange; and Ser70 and Ala237, certainly because of very broad and/or highly overlapped resonances. In addition, residues that overlapped severely were excluded from further analysis (see Table S2, Table S3, and Table S4). Hence, a total of 230 residues were characterized with data at the three magnetic fields (N = 231 at 50.6 MHz, 232 at 60.8 MHz, and 238 at 81.0 MHz).

15N spin relaxation data

15N spin relaxation data consisted of three sets of experiments: 15N-R1, 15N-R2, and {1H}15N - NOE. Data at more than one magnetic field being required for overdetermination of model-free parameters, we acquired data at 11.7, 14.1, and 18.8 T (respectively, 50.6, 60.8, and 81.0 MHz nitrogen frequency). To confirm that the sample did not change during the experimental scheme, we recorded one set of NOE, three complete sets of R1, and two complete sets of R2 at 60.8 MHz before recording data at 50.6 and 81.0 MHz. After data acquisition at 50.6 and 81.0 MHz, we recorded two sets of NOE, one complete set of R1, and three complete sets of R2 again at 60.8 MHz. Moreover, it allowed us to verify that error on spin relaxation data was neither under- nor overestimated using Jackknife and Monte Carlo methods (data not shown). For example, the four different R1 data sets recorded at 60.8 MHz gave rates that, within estimated errors, were reproducible for most residues. Mean relative errors for these data sets were as follows: 2.77%, 2.91%, 2.77%, and 3.28%. On the other hand, mean error for the combined data sets was 2.47%, reflecting the improvement obtained when using more data points. Data sets recorded at 50.6 and 81.0 MHz were not repeated as for 60.8 MHz (except for NOE at 50.6 MHz), but displayed errors of the same range. Finally, even though R2 values obtained at 60.8 MHz were extracted from experiments with two different RF fields (5.2 and 6.0 kHz), this difference did not affect rates, which fell within respective errors (data not shown). 15N spin relaxation data for PSE-4 have been deposited in the Biological Magnetic Resonance Data Bank (BMRB) (6838).

Statistics for the 2103 observables are available in Table S1. Mean errors for the recorded parameters vary between 2 and 4% before scaling (see Methods). Except for the five C-terminal residues, PSE-4 dynamics seems to be quite homogeneous, as is the case for TEM-1 (10). This points to a unique diffusion core for this enzyme.

Data sets consistency

To extract high quality information from multiple field experiments, it is important that data sets share a high degree of consistency. Inconsistencies can arise from several factors, including variations in sample viscosity (caused by changes in temperature, concentration, etc.) and water saturation during acquisition (which influences N-H moieties as a function of the exchange rate with the aqueous solvent). In this study, the field-independent function J(0) (the spectral density at the zero frequency) (22) was used to assess data sets consistency.

Results from this consistency test demonstrate the good quality of the three data sets (Fig. S3). The 50.6 and 60.8 MHz data display especially high consistency, whereas 81.0 MHz consistency with 50.6 and 60.8 MHz data is good. The somehow wider distributions seen for data at 81.0 MHz were assessed further (see model-free analysis, below).

Model-free analysis

The model-free formalism (15,16,23,29) is the preferred approach for spin relaxation data analysis. Using this formalism, two main parameters, S2 and τ, account, respectively, for the restriction of the motion for one vector (e.g., the N-H bond) and the effective upper limit for the timescale of this motion (normalized by S2). Moreover, the Rex parameter can account for slow motions on the μs-ms timescale contributing to the observed R2. Several programs have been developed for the optimization of the model-free parameters. We used the open source program relax (23,24) with the protocol presented in Fig. S4.

A reanalysis of TEM-1's spin relaxation data (10) using the same approach as the one used here for PSE-4 has been performed recently and will be presented elsewhere. In this study, data were also reanalyzed using the same approach as in Savard and Gagné (10), but with ModelFree-4.20 (30,31) to avoid problems present in the preceding versions of the program (23). In the following discussion, results obtained for PSE-4 will be compared with those for TEM-1 in either publication, especially when differences arise.

Since the consistency test revealed some inconsistency in the 81.0 MHz data, an in-depth look at the data was done. We found out the R2 data at 81.0 MHz were causing this inconsistency and did not use it for model-free analysis. Because the inconsistency was detected, it does not affect the quality of the extracted information. Details are available in the Supporting Material.

Description of global diffusion

The diffusion of PSE-4 is homogeneous. This is confirmed by the derivation of model-free parameters using a local diffusion tensor for each N-H vector. Indeed, the mean local τm is 12.70 ± 0.87 ns (excluding the three C-terminal residues) with only a few dispersed outsiders, thus with no region in the three-dimensional structure showing differential diffusion (data not shown).

Table 1 shows a summary of the optimization results for the different diffusion tensors tested. The best model consists of an ellipsoid described by the isotropic component of diffusion Diso = 13.141 (± 0.024) × 106 s−1, the anisotropy of diffusion Da = 3.75 (± 0.19) × 106 s−1, the rhombicity Dr = 0.080 (± 0.022) s−1, the global correlation time τm = 12.683 (± 0.024) ns, and the diffusion constants for the three principal diffusion axes Dx = 11.59 (± 0.10) × 106 s−1, Dy = 12.19 (± 0.11) × 106 s−1, and Dz = 15.64 (± 0.13) × 106 s−1. A representation of this diffusion tensor, and of the orientations of the N-H vectors used for its optimization, is available in Fig. S5. These parameters are close to the prolate description of TEM-1 presented in Savard and Gagné (10), where D‖/D⊥ was equal to 1.23. Indeed, for PSE-4, D‖/D⊥ = Dz/((Dx + Dy)/2) = 1.32. Anisotropy for PSE-4 extracted from the model-free analysis agrees with the shape from the crystal structure (14), the relative moments of inertia being 1.00, 0.89, and 0.59 as determined using the program pdbinertia (A. G. Palmer, Columbia University, New York, NY).

Table 1.

Summary of the diffusion tensor optimization

| Diffusion model | AIC | τm (ns) | D‖/D⊥ | θ (°) | ϕ (°) | ψ (°) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Local τm | 1442.1 | — | — | — | — | — |

| Sphere | 1492.2 | 12.39 | 1 | — | — | — |

| Prolate spheroid | 1391.3 | 12.67 | 1.33 | 147.5 | 50.1 | — |

| Oblate spheroid | 1475.6 | 12.45 | 0.92 | 38.9 | 27.2 | — |

| Ellipsoid∗ | 1385.1 | 12.68 | 1.32 | 166.2 | 146.8 | 131.6 |

We used 134 residues in regular secondary structures with relaxation data at three fields.

Lowest AIC: selected description.

Finally, diffusion description from model-free analysis is close to that estimated from hydrodynamics calculations using HYDRONMR (32) (with parameter a, the effective radius of the atomic element, set to 2.6 Å, as in Hall and Fushman (33)). In fact, using this approach, Da = 3.82 × 106 s−1, i.e., within 2% of model-free derived Da. Moreover, values of the diffusion constant for the three principal axes of the diffusion were within 4% of the model-free derived values, with D‖/D⊥ = 1.30. A similar analysis for TEM-1 is in agreement with PSE-4 having a higher anisotropy than TEM-1 and endorses model-free results for global tumbling.

Description of local motions

Fig. S6 shows the optimized residue-specific model-free parameters. Even though parameters are far more important than model listing, we can summarize PSE-4 local model-free models as follows: m0 (1), m1 (129), m2 (46), m3 (28), m4 (3), m5 (19), m6 (3), m7 (0), m8 (0), and m9 (1), for a total of 230 N-H vectors analyzed. As is seen here, most residues (77%) are fitted with simple models m1 and m2. Local model-free parameters for PSE-4 have been deposited in the BMRB.

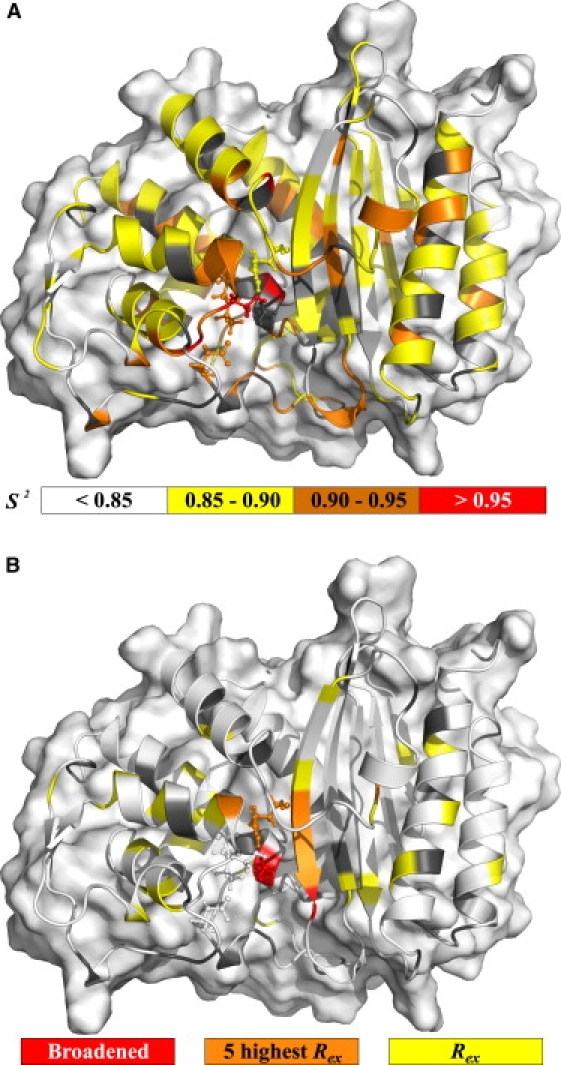

Order parameters

The mean order parameter (S2) of PSE-4 backbone amides is 0.861 ± 0.087 (0.868 ± 0.051 excluding the three C-terminal flexible residues). Additionally, the mean S2 for the secondary structure core (0.879 ± 0.035) is slightly higher and less dispersed than that for the loops and very short helices (0.834 ± 0.125; 0.852 ± 0.066 excluding the flexible C terminus). Clearly, PSE-4 is a highly ordered protein on the ps-ns timescale, displaying S2 > 0.85 (the typical value for regular secondary structures, equivalent to motion on a cone of semiangle θ = 19° (15)) for 70% of its amides (Fig. 1 A). The most rigid amides are located around the active site and Ω loop, as was the case for TEM-1 (10). Only some solvent exposed loops are less rigid, with just five residues (Asn53, Ser292, Gln293, Ser294, and Arg295) possessing an order parameter below 0.70, indicating the absence of high amplitude backbone motions in PSE-4, similar to previous observations for TEM-1. This high rigidity might be related to the low thermal stability of both TEM-1 and PSE-4, which precipitate in vitro at temperatures >41°C (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Motions extracted from model-free analysis. (A) Backbone amide ps-ns timescale generalized order parameter (S2). (B) Residues fitted using a conformational exchange term (Rex, model-free models m3, m4, m7, m8, or m9). In all insets, gray cartoon is used for residues without data (prolines, overlapped and unassigned) whereas, in the Rex inset, white cartoon representation is used for absence of the parameter in the model fitted. Active site residues (Ser70, Lys73, Ser130, Glu166, and Arg234) are shown in the stick representation. Missing residues in the crystal structure (Ser22, Ser23, Gln293, Ser294, and Arg295) were added for visualization of their fitted parameters (refer to electronic figure for color representation).

When comparing TEM-1's model-free order parameters with those of PSE-4, TEM-1 appears slightly more rigid than PSE-4 (Fig. S8). Differences seem to be smaller for the Ω loop where order parameters agree more than for other loops, pointing to a conservation of order for this important part of the enzyme. This similarity of backbone dynamics on the ps-ns timescale might hide important differences for side-chain motions, as is the case for calmodulin (34). However, this is beyond the scope of this article.

Conformational exchange

Fig. 1 B shows residues for which a contribution to R2 from μs-ms motions had to be accounted for. Rex parameters depend on several factors (timescale of exchange, populations of either states, and chemical shift difference). Conformational exchange can be detected either for a moving N-H moiety or for a rigid vector with a moving neighbor modulating its chemical shift but can be invisible for certain combinations of timescales, populations, and chemical shift changes. Rex parameters are scaled quadratically with the magnetic field and are presented in this study for an effective magnetic field of 60.8 MHz. Thus, Rex values for TEM-1 (10) are rescaled from their originally associated field (50.6 MHz) for comparison purposes.

In PSE-4, 32 residues have a nonnull Rex parameter. Of these, five are particularly important because of both their elevated Rex parameter and localization on the protein three-dimensional structure. These are residues Thr128, Leu221, Arg234, Ser235, and Gly236, which are located 4.5–12.5 Å from the active site. This is consistent with two nearby residues (Ser70 and Ala237) not being observed, probably because of their extreme broadening arising from important μs-ms motions. Since these motions are near the surface of the active site cavity, conformational exchange could arise because of a ligand moving in and out of the cavity. A potential candidate for this motion could be a structural water molecule moving slowly between residues Asn214, Arg234, and Ser235, as seen in a 5-ns MD simulation of TEM-1 (35). This would point to a conservation of slow motions in the active site for both TEM-1 and PSE-4. The motion of this water molecule would also affect residues Ser70 and Ala237 (extremely broadened), both being on the path which the ligand would take to possibly access residues Asn214, Arg234, and Ser235. The Rex for Gly236 could be explained in the same way. The same is valid for TEM-1, where Rex parameters arise near the active site and Ala237 could not be assigned.

Active-site residues

TEM-1's active site has been shown to be extremely ordered on the ps-ns timescale with several residues displaying order parameters >0.94 (10). This was consistent with active site residues displaying lower than average B-factors for TEM-1 in the presence of a sulfate ion in the active site (36). In PSE-4, the most rigid residues on the ps-ns timescale are also located in the active site, pointing to a meaningful conservation of this feature which could also be foreseen from backbone amide B-factors (14) (Fig. S7).

Ser70: N-H correlation for Ser70 is not observed. In TEM-1, it is severely overlapped and broadened, thus unusable. This strongly supports the existence of motions on timescales slower than global tumbling (e.g., μs-ms) also affecting other residues in the vicinity that display broadened backbone (Ala237) or side-chain (Lys73) resonances.

Lys73: Lys73 is suspected of being involved in the first catalytic step (acylation), where its side-chain Nζ group could activate Ser70 by accepting a proton from the side-chain hydroxyl group (2.8 Å away) (1). Lys73 was fitted to model m1 with one of the highest order parameters throughout PSE-4 (0.94 ± 0.01). This contrasts with the low intensity of its N-H cross-peak, which suggests that chemical exchange broadening may be present. Indeed, Lys73's Cα is the weakest of all lysine Cα (data not shown). Moreover, we were unable to see Lys73's side chain further than the Cβ, thus preventing the titration of the side-chain Nζ group. These, again, indicate important μs-ms motions nearby. These motions could be similar to those presumably affecting Ser70, located <6 Å away (N-H to N-H). If rejecting model m1 because of these evidences of slow motions arising nearby, the second lowest size-corrected AIC score for Lys73 within PSE-4 is model m3 with an Rex parameter of 0.7 ± 0.5 s−1. Compared with the Rex parameters for other residues, this Rex would be the lowest and the one with the highest relative error. Hence, the possibility for Lys73 N-H to be fitted using an Rex parameter is questionable, although strong signs of conformational exchange are present, especially for the side chain. The situation in TEM-1 was very similar, and Lys73 fitted model m1 with a S2 of 0.95 ± 0.02. These data indicate Lys73's side chain could be affected by motions in the slow- or intermediate-exchange regime. Under certain conditions, Rex does not scale quadratically with the magnetic field (37). This could explain the low Rex with high error obtained for Lys73 when using model m3, where the model-free fitting procedure scales the Rex quadratically for multiple field data. Incorporating the parameter α from Millet et al. (37) in the fitting procedure could potentially alleviate this problem. Finally, if present, these motions could explain the extreme broadening of Lys73's side chain, as well as Ser70 and Ala237 amides. Such very slow motions will, in the future, be probed by relaxation dispersion experiments.

Tyr105: Tyr105 displays a correlation time of 1008 ± 188 ps in conjunction with an S2 of 0.80 ± 0.02 using the two-timescale model m5. In TEM-1, this residue was one of the most flexible (10) and the selected model did not incorporate this kind of two-timescale motion as in PSE-4. This could be of significant importance in regard to substrate recognition and specificity. The motion detected here could, however, be artefactual because model m2 also fits relatively well the experimental data: with a higher S2 (0.85 ± 0.01), but with a correlation time of 26 ± 4 ps, similar to the case in TEM-1. On the other hand, model m5 could suit data almost as well in TEM-1, yielding a similar S2 (0.79) but with a τs of ∼500 ps.

In another work, Doucet et al. (38) discussed the importance of this residue for substrate specificity and proposed that steric restriction of the active site by residue Tyr105 side chain could allow the correct positioning and stabilization of substrates within the active site, thus facilitating catalysis. This gate-keeping function was further investigated and the side chain of Tyr105 was shown to adopt two conformations: one in which the side chain points toward Val216 (open state, rotamer t) and one in which the side chain points toward Glu104 (closed state, rotamer m, only visible in inhibitor-bound TEM-1) (39). This motion seen for TEM-1 could influence the dynamics of the backbone N-H moiety of Tyr105 in PSE-4 where rotamer t is present, with only minor electronic density toward the position of rotamer m. Using SHIFTS (Ver. 4.1.1) (40), chemical shifts for the two rotamers discussed in Doucet et al. (38) were predicted. Based on these results, only two residues would have their backbone 15N chemical shift modified by such a transition between the two rotamers t and m. Of course, Tyr105 amide nitrogen has a different chemical shift in both rotamers, although the difference is very small (12 Hz at 60.8 MHz) and would not give rise to a significant Rex. Ser106 would be more affected with a difference in 15N chemical shift of 286 Hz at 60.8 MHz between the two rotamers. This would be expected to give rise to an Rex term, although no such parameter was observed in the model-free minimization. A possible explanation for this situation is that the timescale for this conversion from rotamer t to rotamer m would be on the subnanosecond timescale as proposed by the selected model for Tyr105. If so, it would not influence transverse relaxation of Ser106 and would only be probed by Tyr105 itself.

Ser130: Residue Ser130 has been proposed to participate in the catalytic process (5) and was shown to be of clinical importance for enhanced resistance (41). In the crystal structure by Lim et al. (14), the hydroxyl group of Ser130 displays two alternative positions. Such alternative positions with a shared occupancy of 0.5 between two conformations are seen for eight other residues in the crystal structure (14). From model-free analysis, Ser130 fits model m1 (as other residues we could observe with atoms displaying shared occupancy of 0.5) with an S2 of 0.95 ± 0.02. The movement of its side chain might not influence the amide transversal relaxation of Ser130, but, depending on the timescale, could be the cause of such conformational exchange effects seen for nearby residues Ser70 (not observed, broadened), Thr128, Arg234, Ser235, Gly236, and Ala237 (not observed, broadened), all within 5 to 8 Å from the side chain of Ser130. In TEM-1, no model-free parameter could be extracted (10). As for Lys73, Ser130 order parameter in PSE-4 is very high. This is also the case for other residues of the conserved Ser130-Asp131-Asn132 (0.95 ± 0.02, 0.92 ± 0.01, and 0.97 ± 0.01, respectively) structural motif (known as the SDN loop).

Glu166: Residue Glu166 is directly involved in catalysis, probably for both acylation and deacylation steps (1). As was the case for the two catalytic residues Lys73 and Ser130, residue Glu166 fits model m1 with a fairly high order parameter (0.91 ± 0.02). In the reanalysis using ModelFree-4.20 for TEM-1, Glu166 fitted model m1 with S2 = 0.94 ± 0.02, in contrast with model m4 in the original work (10). Using relax, this residue was assigned model m2 with S2 = 0.93 ± 0.02 and τe = 47 ± 24 ps. This is not surprising, as the Rex first detected was of low significance and, thus, m4 could simplify to m1 or m2. Rigidity for Glu166 thus seems similar in TEM-1, although a bit higher as for many other residues.

Arg234: In carbenicillin-hydrolyzing β-lactamases such as PSE-4, residue 234 is an arginine. In other class-A β-lactamases, it is a lysine. Arg234 first fitted model m2 with an average S2 of 0.88 ± 0.02. However, the value measured for R2 at 50.6 MHz is most likely underestimated and erroneous, because of the partial overlap with residue Lys192, a result of the poorer resolution at the lower field. Indeed, Arg234 has one of the highest R2 values at both 60.8 and 81.0 MHz, whereas at 50.6 MHz the measured R2 is much lower than for surrounding residues. Hence, when excluding R2 at 50.6 MHz, the selected model becomes m3 with an unchanged order parameter of 0.88 and an Rex parameter of 4.2 ± 1.6 s−1. This is much more logical for this residue, because the majority of surrounding residues display signs of conformational exchange. Moreover, for TEM-1, presence of Rex was also found using either ModelFree-4.20 or relax, both with an Rex of 1.9 ± 0.4 s−1 and a high S2 of 0.94 ± 0.02. Thus, order on the ps-ns timescale would be higher in TEM-1, but the presence of slow μs-ms motions would be similar, again indicating the presence of conserved μs-ms motions near the active site.

Ω loop: A 19-residue loop is located below the active site of class-A β-lactamases (residues Arg161 to Asp179). This loop is an Ω loop, a nonregular secondary structure found in many proteins (42). It was shown in two different studies to be flexible in TEM-1 using in silico approaches (35,43). Indeed, in a 5-ns simulation (35), a flaplike motion of the Ω loop was present for TEM-1 in the absence of a ligand. The timescale was undefined in this study because this phenomenon was only seen once, the loop keeping its new position after the movement had happened. No such motion had been seen in the 1-ns simulation by Díaz et al. (44); these inconsistencies could either be a result of the short simulation length in the Díaz et al. (44) study or of simulation artifacts in the study of Roccatano et al. (35). Nevertheless, in TEM-1, using NMR, the Ω loop was shown to be very rigid on the ps-ns timescale, although displaying the presence of some μs-ms motions (10). This seems to unite short simulations results showing limited motions with longer simulations pointing to slow high-amplitude motions. Indeed, movements on the order of the μs-ms timescale are hardly defined using currently available MD simulations.

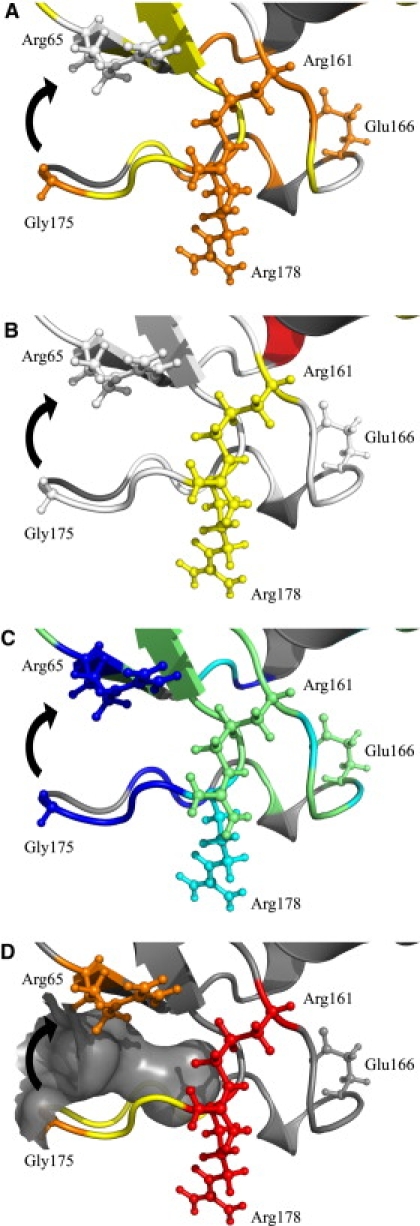

Our results for PSE-4 confirm this observation, although differently from what was seen in TEM-1 using NMR. In fact, only two residues within PSE-4 Ω loop display signs of conformational exchange (i.e., Arg161 and Arg178). These residues are located at the extremities of the Ω loop, where it narrows (with N-H moieties separated by ∼8 Å). Arg178 could represent the hinge of a movement similar to that stated above, which could allow Gly175 (Asn175 in TEM-1) to reach Arg65 to form the hydrogen bond discussed by Roccatano et al. (35) (Fig. 2). This would correspond to a movement of ∼5 Å, Arg65 carbonyl being 7.1 Å from Gly175 amide nitrogen in the steady-state crystal structure. This motion would fill the cavity between the Ω loop and the protein core present in both TEM-1 and PSE-4 (Fig. 2 D). With this cavity closed, the structure would be better packed, possibly transiently stabilizing Glu166 in a catalytically relevant position. The absence of Rex for residues Asp176 and Leu177 does not counterindicate this possibility, as the N-H moiety of Leu177 would point toward the solvent in both conformations and hydrogen bonding of Asp176 N-H group with the carbonyl of residue Lys173 would also be present in both conformations. Unfortunately, because of overlapped resonances, no spin relaxation data are available for residues Lys173 and Leu174, which could sense this movement because they are closer to the protein core. However, these residues both display normal amplitude N, HN, Cα, and Cβ resonances, which could contradict their involvement into conformational exchange. Hence, current observations support the slow motion of the Ω loop proposed by Roccatano et al. (35). Because of the implications of movements of the Ω loop in terms of catalysis, it will be very important to get more insights into this part of the enzyme. In fact, if a movement such as the one discussed above exists, it would allow Glu166 to stay close to Ser70 and potentially act during the acylation step (35).

Figure 2.

Cavity-filling motion for residues Glu171-Leu177 of the Ω loop. (A) Order parameters (S2 colored as in Fig. 1A). (B) Conformational exchange (Rex colored as in Fig. 1B). (C) Apparent free energies of exchange (ΔGHX, colored as in Fig. 3). (D) The cavity between the Ω loop and the protein core that the motion of residues Glu171-Leu177 (yellow) would fill is shown in gray surface. Residues from the hinge (Arg161 and Arg178) are colored red and shown in the stick representation as well as residues Arg65 and Gly175 (orange), which would form a hydrogen bond once the motion (black arrow) is completed. Catalytic Glu166 is also shown in the stick representation. A stereo version is available in the Supporting Material.

Limits in the analytical approach

Many factors limit interpretation of results extracted using the model-free approach (23,24). Here, we will concentrate on three specific limitations: variations of the CSA and rN–H for different N-H moieties, and lack of well-defined N-H vector orientations in crystal structures. In this study, the CSA was held fixed with a value of −172 ppm. This allowed comparison with dynamics data for TEM-1 (10). As for the CSA, rN–H was held fixed with a value of 1.02 Å, which allowed comparison with dynamics data for TEM-1 (10). Further discussion on CSA and rN–H is available in the Supporting Material. Crystal structure 1G68 (14) has a 1.95 Å resolution, which does not allow the visualization of protons. Hence, derived N-H vector orientations may be erroneous from their actual average position, potentially having an effect on the model-free models selected because goodness of fit depends on N-H vector orientation compared to the diffusion tensor orientation. Moreover, for residues potentially involved in crystal contacts, orientations might be slightly off, which could also bias model-free analysis. This situation could be assessed by allowing variation of N-H bond orientations during model-free minimization. However, we chose not to introduce such variable into our analysis.

Amide exchange

Steady-state amide exchange experiments allow the study of higher energy states, difficult to detect with techniques reporting on ensembles. They can probe the presence of partially unfolded states, intermediates of which could be of importance for catalysis. Two limit cases for amide exchange exists: EX1 and EX2 (45). In the EX2 regime, insights into the thermodynamics of the opening reaction for the structure protecting the N-H group from exchange (transient unfolding processes) can be obtained. The equilibrium constant of exchanging sites Kop = 1/SF = kopen/kclose, where SF is the protection factor, and kopen and kclose the opening and closing rates, respectively, is calculated from Kop = kex/kc, where kex is the exchange rate, and kc is the expected unprotected exchange rate (intrinsic rate) (46,47). Moreover, the apparent stabilization free energy of the protecting structure is obtained from ΔGHX = – RT ln Kop.

In the EX2 regime, exchange rates are pH-dependent, whereas in the EX1 limit, they are not affected by pH. Exchange was faster at pH 7.85 for all residues for which data were available, hence confirming the EX2 regime at pH 6.65 (see Table S4 and Fig. S9). A change of pH from 6.65 to 7.85 would theoretically cause effective rates to increase by a factor of 16. The mean increase of kex, in our case, was of 11 ± 7 (not including amides exchanging too fast to be observed at pH 7.85). This lower value could be a result of some amides entering the EX1 regime at a pH slightly below 7.85. Of the 226 residues with available data at pH 6.65, 101 exchanged very rapidly and were already unobservable in the first time point (i.e., after only 32 min, with kex > 1 × 10−3 s−1). Therefore, 125 residues had a measurable exchange rate ranging from 2 × 10−3 s−1 to 3 × 10−8 s−1. ΔGHX, as well as Kop and SF, were calculated using an Excel spreadsheet from S. W. Englander (University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA) and are displayed in Table S4. Moreover, ΔGHX values are shown in Fig. 3. These data have been deposited in the BMRB (6838).

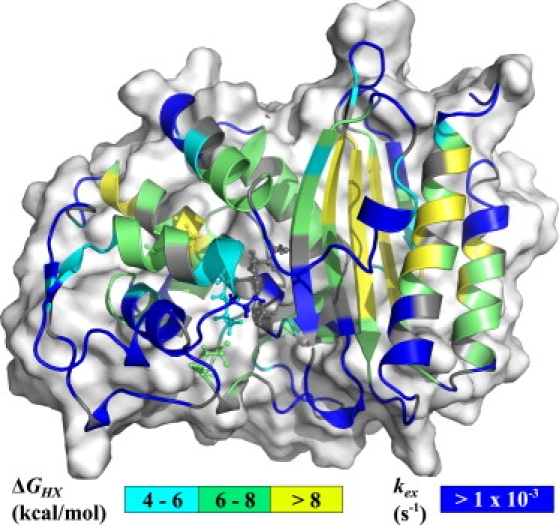

Figure 3.

Apparent stabilization free energies of the protecting structures (ΔGHX). The value kex is shown for residues for which exchange was too fast for being quantified (kex > 1 × 10−3 s−1). Important active site residues (Ser70, Lys73, Ser130, Glu166, and Arg234) and the disulfide bond (between Cys77 and Cys123, connecting two helices of the α-domain) are shown in the stick representation. Missing residues in the crystal structure (Ser22, Ser23, Gln293, Ser294, and Arg295) were added for visualization of their parameters.

Globally, free energies of opening are ∼6–11 kcal mol−1 for most residues within secondary structures, and are slightly higher in the α/β domain where many residues have ΔGHX > 8 kcal mol−1. Hence, this domain is more stable than the all α-domain. This is contrary to what was proposed for TEM-1 (10), that the α-domain might be the most stable. This hypothesis was speculative, as no amide exchange rate had been extracted, nor verification of EX2 regime done. For TEM-1, the slowest exchanging amides were those from the all α-domain and the authors concluded that this domain is more stable than the α/β domain because of the presence of the disulfide bond between Cys77 and Cys123, as proposed by Vanhove et al. (48). Here, we postulate the contrary for PSE-4 based on EX2 exchange data. In PSE-4, though the disulfide bond between Cys77 and Cys123 stabilizes the local structure (surrounding residues with ΔGHX between 4 and 8 kcal mol−1), the protection from the solvent in the α-domain is globally lower than in the α/β domain. One might argue that the disulfide bond in the PSE-4 sample is not formed. However, this is ruled out by Cβ chemical shifts (49) for Cys77 (41.6 ppm) and Cys123 (42.0 ppm) (17), which show that both Cys are oxidized. The most stable domain in PSE-4 is the α/β domain, whereas it could be the α-domain in TEM-1. Indeed, theoretical free energy of folding calculated using VADAR (50) shows that the all α-domain in TEM-1 would be more stable than in PSE-4, whereas the inverse is predicted for the α/β domain (data not shown). These could indicate some thermodynamics differences between the two domains of these homologs. However, to confirm this hypothesis, analysis of data in the EX2 regime is required for TEM-1.

As expected, the first protons to exchange with the solvent were those within loops as well as most key residues from the active site (Fig. 3). Moreover, all glutamine and asparagine side chains were exchanged rapidly. These N-H moieties being all located at or near the protein surface, their exchange is too fast for steady-state exchange experiments and would require approaches such as pulse labeling (45). It is interesting to note that all residues from the Ile97 to Gln115 region exchange fast, as well as residues Asn132 to Ile137 from the adjacent α-helix. This region of PSE-4 could have a nonnegligible population existing as a partially unfolded state (probably with ΔGHX < 4 kcal mol−1, kex values all being >1 × 10−3 s−1, despite 17 amides out of 24 having null ASA, as calculated using VADAR (50)). Indeed, ΔGHX below 4 kcal mol−1 would correspond to populations of partially unfolded states for >0.1%. Thus, the subdomain formed by residues Ile97 to Gln115 and Asn132 to Ile137 could be the driving force for the lower stability of the close by α-domain. Hence, local unfolding could arise near the active site, including residue Tyr105, for which motions were discussed above. These local unfolding events, from both their population and their possible timescale and location could have a profound impact on PSE-4 catalysis and might be the cause of some of the observed Rex.

The fact that the amide of Glu166 and a few other amides from the Ω loop are protected from exchange with ΔGHX between 6 and 8 kcal mol−1 points toward some motional restriction of this long loop, preventing the disruption of the network of hydrogen bonds and the exposure of amide moieties to solvent. This argues against μs-ms motions proposed for TEM-1 in Savard and Gagné (10), where residues Arg164, Glu166, and Leu169 possessed a Rex parameter, these three residues displaying ΔGHX of 7.3, 7.6, and 6.1 kcal mol−1, respectively, within PSE-4. However, this is in agreement with the motion proposed by Roccatano et al. (35) and discussed in the model-free analysis, above, where residues Glu171-Leu177 (with kex > 1 × 10−3 s−1) could move toward the protein core without affecting residues Arg161-Glu170 (with mean ΔGHX ∼6.7 kcal mol−1), as shown in Fig. 2. Indeed, this motion could transiently position the Ω loop so Glu166 is in the vicinity of Ser70 (35). Moreover, the loop could be protected against complete hydration. In fact, as stated before, at the location where residues Glu171-Leu177 are proposed to translate by this motion, a cavity is present (Fig. 2 D). This available space would be filled in the closed state. The same cavity being also present in TEM-1, the conservation of this motion among class A β-lactamases is plausible, in agreement with observations from Roccatano et al. (35), as well as with recent simulations of both TEM-1 and PSE-4 which show motions of a different nature for the Ω loop, also consistent with our experimental data (O. Fisette and S. Gagné, personal communication, 2008). Finally, the fact that this motion was only seen once during the 5-ns simulation is consistent with a much slower effective timescale, as suggested by Rex parameters extracted from model-free analysis.

Finally, during model-free analysis, Ser235 and Gly236, which both exchange with rates faster than 1 × 10−3 s−1, were fitted with high Rex parameters (7.5 and 4.5 s−1, respectively). These data, in addition to null ASA for these amides, support the presence of μs-ms motions near the active site, potentially severely broadening amide cross-peaks of residues Ser70 and Ala237, as discussed before. Once again, these motions might be important for catalysis since kcat for hydrolysis of β-lactams by β-lactamases is ∼1 ms−1.

Conclusions

This work is the first NMR characterization, to our knowledge, of the dynamics of a class A carbenicillin hydrolyzing β-lactamase. It follows the study of Savard and Gagné (10), which explored the dynamics of another class A β-lactamase, TEM-1.

Linking results from the different techniques used here to PSE-4 catalytic activity is not straightforward (51). The global picture of PSE-4 depicted in this report shows a very rigid protein on several timescales. Indeed, ps-ns timescale order parameters are elevated, almost as much as in the case of the homologous TEM-1. Moreover, overall stability is also quite elevated, with apparent free energies of opening (from amide exchange experiments) reaching 11 kcal mol−1 for several residues in the β-sheet of the α/β domain. These results contrast with the low thermal stability of both TEM-1 and PSE-4 and with the presence of slow μs-ms motions.

Rigidity on the ps-ns timescale could be a characteristic of all class A β-lactamases. As stated before, the catalytic efficiency of some of the class A β-lactamases is diffusion controlled (3). This high efficiency supplemented by a high plasticity toward different types of β-lactams contrasts with the restricted motions in the catalytic site, at least on the ps-ns timescale. Longer timescales might be populated by important conserved motions as shown for many active site residues displaying conformational exchange terms (Rex) reporting on the μs-ms timescale, the timescale of enzyme catalysis (e.g., PSE-4's kcat against ampicillin and carbenicillin is ∼1.2 ms−1 (52)). Moreover, the absence of detectable high amplitude motions on the faster timescales might show that the active site of class A β-lactamases adapts its shape on substrate approach, thus pointing to motions present during some steps of the catalytic process. To further understand this feature, it will be interesting to get insights into those longer timescales and to study dynamics of TEM-1 and PSE-4 mutants. Moreover, it will be critical to obtain data regarding dynamics during catalysis (see below).

We are aware that backbone dynamics can be decoupled from side-chain motions (34). The apparent lack of motions seen for backbone N-H moieties on the ps-ns timescale could be coupled to important side-chain motions on the same timescale. In addition, the apparent dynamics similarity between TEM-1 and PSE-4 might also prove limited to backbone amides with side chains potentially displaying different motional patterns. Hence, a side-chain dynamics study might prove very insightful. Moreover, we are mindful about the lack of data for a bound form of PSE-4 either with a β-lactam or an inhibitor. However, as highlighted by Savard and Gagné (10), this proves to be very difficult, considering the high catalytic efficiency of these enzymes. Finally, we are aware that conformational exchange indications showed here are qualitative and extracted from the transversal relaxation rates variations over a restricted range of magnetic field strengths. Hence, the μs-ms timescale will be an interesting target for further studies to better quantify the slow motions detected here, especially for what concerns motions around the Ω loop and active site cavity. This will be quite interesting, as this timescale is where the cleavage of the β-lactam ring occurs. Thus, the recording of relaxation dispersion data will certainly shed light onto the conformational exchange processes suspected to arise near the active site. Here, some residues (e.g., Lys73), although rigid on the ps-ns timescale, display broadened resonances, in addition to some resonances even being invisible, as a result of peak broadening (e.g., Ser70).

Finally, the detailed backbone dynamics data gathered for PSE-4 will join those from TEM-1 in enabling in-depth MD simulations. A comparative study of PSE-4 backbone dynamics characterized by MD and NMR is currently underway. This will permit better in silico studies of the dynamics of class A wild-type and mutant β-lactamases in the presence of substrate, experiments which are impossible using NMR because the turnover rate of relevant β-lactams is tremendously fast with respect to NMR experiments being quite long.

Acknowledgments

We thank Edward d'Auvergne for many reasons, among which are interesting discussions on NMR theory (and for relax), and we thank Pierre-Yves Savard, Olivier Fisette, Richard Daigle, Nicolas Doucet, Tara Sprules, Roger C. Levesque, and Pierre Lavigne for stimulating discussions.

This work was supported by operating grants from Fonds de la Recherche en Santé du Québec and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, infrastructure grants from Canada Foundation for Innovation (both Innovation and New Opportunity), and studentships to S. Morin from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, Fonds de la Recherche en Santé du Québec, and Fondation J.-Arthur Vincent.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Fisher J.F., Meroueh S.O., Mobashery S. Bacterial resistance to β-lactam antibiotics: compelling opportunism, compelling opportunity. Chem. Rev. 2005;105:395–424. doi: 10.1021/cr030102i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Matagne A., Lamotte-Brasseur J., Frère J.M. Catalytic properties of class A β-lactamases: efficiency and diversity. Biochem. J. 1998;330:581–598. doi: 10.1042/bj3300581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Christensen H., Martin M.T., Waley S.G. β-lactamases as fully efficient enzymes. Determination of all the rate constants in the acyl-enzyme mechanism. Biochem. J. 1990;266:853–861. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hedstrom L. Serine protease mechanism and specificity. Chem. Rev. 2002;102:4501–4524. doi: 10.1021/cr000033x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oefner C., D'Arcy A., Daly J.J., Gubernator K., Charnas R.L. Refined crystal structure of β-lactamase from Citrobacter freundii indicates a mechanism for β-lactam hydrolysis. Nature. 1990;343:284–288. doi: 10.1038/343284a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meroueh S.O., Fisher J.F., Schlegel H.B., Mobashery S. Ab initio QM/MM study of class A β-lactamase acylation: dual participation of Glu166 and Lys73 in a concerted base promotion of Ser70. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:15397–15407. doi: 10.1021/ja051592u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Allerhand A., Doddrell D., Glushko V., Cochran D.W., Wenkert E. Conformation and segmental motion of native and denatured ribonuclease A in solution. Application of natural-abundance carbon-13 partially relaxed Fourier transform nuclear magnetic resonance. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1971;93:544–546. doi: 10.1021/ja00731a053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wand A.J. Dynamic activation of protein function: a view emerging from NMR spectroscopy. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2001;8:926–931. doi: 10.1038/nsb1101-926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yon J.M., Perahia D., Ghélis C. Conformational dynamics and enzyme activity. Biochimie. 1998;80:33–42. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(98)80054-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Savard P.-Y., Gagné S.M. Backbone dynamics of TEM-1 determined by NMR: evidence for a highly ordered protein. Biochemistry. 2006;45:11414–11424. doi: 10.1021/bi060414q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Doucet N., Savard P.-Y., Pelletier J.N., Gagné S.M. NMR investigation of Tyr105 mutants in TEM-1 β-lactamase: dynamics are correlated with function. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:21448–21459. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609777200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Newsom S.W. Carbenicillin-resistant Pseudomonas. Lancet. 1969;2:1141. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(69)90742-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reid A.J., Simpson I.N., Harper P.B., Amyes S.G. The differential expression of genes for the PSE-4 β-lactamase in Pseudomonas aeruginosa and the Enterobacteriaceae. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 1988;21:525–533. doi: 10.1093/jac/21.5.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lim D., Sanschagrin F., Passmore L., Castro L.D., Levesque R.C. Insights into the molecular basis for the carbenicillinase activity of PSE-4 β-lactamase from crystallographic and kinetic studies. Biochemistry. 2001;40:395–402. doi: 10.1021/bi001653v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lipari G., Szabo A. Model-free approach to the interpretation of nuclear magnetic resonance relaxation in macromolecules. 1. Theory and range of validity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1982;104:4546–4559. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lipari G., Szabo A. Model-free approach to the interpretation of nuclear magnetic resonance relaxation in macromolecules. 2. Analysis of experimental results. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1982;104:4559–4570. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morin S., Levesque R., Gagné S.M. 1H, 13C, and 15N backbone resonance assignments for PSE-4, a 29.5 kDa class A β-lactamase from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Biomol. NMR. 2006;36(Suppl 1):11. doi: 10.1007/s10858-005-5343-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kay L.E., Keifer P., Saarinen T. Pure absorption gradient enhanced heteronuclear single quantum correlation spectroscopy with improved sensitivity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992;114:10663–10665. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Farrow N.A., Muhandiram R., Singer A.U., Pascal S.M., Kay C.M. Backbone dynamics of a free and phosphopeptide-complexed Src homology 2 domain studied by 15N NMR relaxation. Biochemistry. 1994;33:5984–6003. doi: 10.1021/bi00185a040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tjandra N., Wingfield P., Stahl S., Bax A. Anisotropic rotational diffusion of perdeuterated HIV protease from 15N NMR relaxation measurements at two magnetic fields. J. Biomol. NMR. 1996;8:273–284. doi: 10.1007/BF00410326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Delaglio F., Grzesiek S., Vuister G.W., Zhu G., Pfeifer J. NMRPipe: a multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes. J. Biomol. NMR. 1995;6:277–293. doi: 10.1007/BF00197809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Farrow N., Zhang O., Szabo A., Torchia D., Kay L.E. Spectral density function mapping using 15N relaxation data exclusively. J. Biomol. NMR. 1995;6:153–162. doi: 10.1007/BF00211779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.d'Auvergne E.J., Gooley P.R. Optimization of NMR dynamic models. I. Minimization algorithms and their performance within the model-free and Brownian rotational diffusion spaces. J. Biomol. NMR. 2008;40:107–119. doi: 10.1007/s10858-007-9214-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.d'Auvergne E.J., Gooley P.R. Optimization of NMR dynamic models. II. A new methodology for the dual optimization of the model-free parameters and the Brownian rotational diffusion tensor. J. Biomol. NMR. 2008;40:121–133. doi: 10.1007/s10858-007-9213-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kabsch W., Sander C. Dictionary of protein secondary structure: pattern recognition of hydrogen-bonded and geometrical features. Biopolymers. 1983;22:2577–2637. doi: 10.1002/bip.360221211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Akaike, H.1973. Information theory and an extension of the maximum likelihood principle. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Symposium on Information Theory, Budapest, Hungary. B.N. Petrov and F. Csaki, editors.

- 27.Hurvich C., Tsai C.-L. Regression and time series model selection in small samples. Biometrika. 1989;76:297–307. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ambler R.P., Coulson A.F., Frère J.M., Ghuysen J.M., Joris B. A standard numbering scheme for the class A β-lactamases. Biochem. J. 1991;276:269–270. doi: 10.1042/bj2760269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Clore G.M., Szabo A., Bax A., Kay L.E., Driscoll P.C. Deviations from the simple two-parameter model-free approach to the interpretation of Nitrogen-15 nuclear magnetic-relaxation of proteins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990;112:4989–4991. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Palmer A., Rance M., Wright P. Intramolecular motions of a zinc finger DNA-binding domain from Xfin characterized by proton-detected natural abundance 13C heteronuclear NMR spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991;113:4371–4380. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mandel A.M., Akke M., Palmer A.G. Backbone dynamics of Escherichia coli ribonuclease HI: correlations with structure and function in an active enzyme. J. Mol. Biol. 1995;246:144–163. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.0073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.García de la Torre J., Huertas M.L., Carrasco B. HYDRONMR: prediction of NMR relaxation of globular proteins from atomic-level structures and hydrodynamic calculations. J. Magn. Reson. 2000;147:138–146. doi: 10.1006/jmre.2000.2170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hall J.B., Fushman D. Characterization of the overall and local dynamics of a protein with intermediate rotational anisotropy: differentiating between conformational exchange and anisotropic diffusion in the B3 domain of protein G. J. Biomol. NMR. 2003;27:261–275. doi: 10.1023/a:1025467918856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee A.L., Kinnear S.A., Wand A.J. Redistribution and loss of side chain entropy upon formation of a calmodulin-peptide complex. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2000;7:72–77. doi: 10.1038/71280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roccatano D., Sbardella G., Aschi M., Amicosante G., Bossa C. Dynamical aspects of TEM-1 β-lactamase probed by molecular dynamics. J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. 2005;19:329–340. doi: 10.1007/s10822-005-7003-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jelsch C., Mourey L., Masson J.M., Samama J.P. Crystal structure of Escherichia coli TEM1 β-lactamase at 1.8 Å resolution. Proteins. 1993;16:364–383. doi: 10.1002/prot.340160406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Millet O., Loria J., Kroenke C., Pons M., Palmer A. The static magnetic field dependence of chemical exchange linebroadening defines the NMR chemical shift time scale. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:2867–2877. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Doucet N., De Wals P.-Y., Pelletier J.N. Site-saturation mutagenesis of Tyr-105 reveals its importance in substrate stabilization and discrimination in TEM-1 β-lactamase. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:46295–46303. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407606200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Doucet N., Pelletier J.N. Simulated annealing exploration of an active-site tyrosine in TEM-1 β-lactamase suggests the existence of alternate conformations. Proteins. 2007;69:340–348. doi: 10.1002/prot.21485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xu X.P., Case D.A. Automated prediction of 15N, 13Cα, 13Cβ and 13C′ chemical shifts in proteins using a density functional database. J. Biomol. NMR. 2001;21:321–333. doi: 10.1023/a:1013324104681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lahey Clinic. TEM extended-spectrum and inhibitor resistant β-lactamases. www.lahey.org/Studies/temtable.asp.

- 42.Fetrow J.S. Omega loops: nonregular secondary structures significant in protein function and stability. FASEB J. 1995;9:708–717. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vijayakumar S., Ravishanker G., Pratt R.F., Beveridge D.L. Molecular dynamics simulation of a class A β-lactamase: structural and mechanistic implications. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995;117:1722–1730. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Díaz N., Sordo T.L., Merz K.M., Jr., Suárez D. Insights into the acylation mechanism of class A β-lactamases from molecular dynamics simulations of the TEM-1 enzyme complexed with benzylpenicillin. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:672–684. doi: 10.1021/ja027704o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Krishna M.M.G., Hoang L., Lin Y., Englander S.W. Hydrogen exchange methods to study protein folding. Methods. 2004;34:51–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2004.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bai Y., Milne J.S., Mayne L., Englander S.W. Primary structure effects on peptide group hydrogen exchange. Proteins. 1993;17:75–86. doi: 10.1002/prot.340170110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Connelly G.P., Bai Y., Jeng M.F., Englander S.W. Isotope effects in peptide group hydrogen exchange. Proteins. 1993;17:87–92. doi: 10.1002/prot.340170111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vanhove M., Guillaume G., Ledent P., Richards J.H., Pain R.H. Kinetic and thermodynamic consequences of the removal of the Cys-77-Cys-123 disulphide bond for the folding of TEM-1 β-lactamase. Biochem. J. 1997;321:413–417. doi: 10.1042/bj3210413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sharma D., Rajarathnam K. 13C NMR chemical shifts can predict disulfide bond formation. J. Biomol. NMR. 2000;18:165–171. doi: 10.1023/a:1008398416292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Willard L., Ranjan A., Zhang H., Monzavi H., Boyko R.F. VADAR: a web server for quantitative evaluation of protein structure quality. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3316–3319. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jarymowycz V.A., Stone M.J. Fast time scale dynamics of protein backbones: NMR relaxation methods, applications, and functional consequences. Chem. Rev. 2006;106:1624–1671. doi: 10.1021/cr040421p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sabbagh Y., Thériault E., Sanschagrin F., Voyer N., Palzkill T. Characterization of a PSE-4 mutant with different properties in relation to penicillanic acid sulfones: importance of residues 216 to 218 in class A β-lactamases. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1998;42:2319–2325. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.9.2319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.