Abstract

The prevalence of Baylisascaris procyonis was estimated in the urban raccoon population of Winnipeg through the fecal flotation of raccoon feces collected at active latrines and through gross postmortem and fecal flotation of samples collected from nuisance raccoons. Fecal flotation of latrine-collected feces was positive in 33 of 89 samples and, of 52 latrines identified, 26 were positive on 1 or more occasions. Trapped individual raccoons subjected to postmortem examination were positive in 57 of 114 animals captured. Comparing a single fecal flotation to the gold standard of finding adult worms in the small intestine had a sensitivity of 78.9% and specificity of 92.9%. This study suggests that carriage of Baylisascaris procyonis is widespread in raccoons in the Winnipeg urban ecosystem. Raccoon latrines in Winnipeg should be treated as infectious sites and efforts should be made to limit access of pets and people at risk to those sites.

Résumé

Prévalence et distribution de Baylisascaris procyonis chez les ratons laveurs urbains (Procon lotor) à Winnipeg, au Manitoba. La prévalence de Baylisascaris procyonis a été estimée au sein de la population urbaine de ratons laveurs de Winnipeg par une coproscopie des excréments de ratons laveurs recueillis à des latrines actives et par des nécropsies macroscopiques et des coproscopies d’échantillons recueillis auprès de ratons laveurs nuisibles. La coproscopie des excréments recueillis dans les latrines a été positive pour 33 des 89 échantillons recueillis et, parmi les 52 latrines identifiées, 26 étaient positives à une occasion ou plus. s. Parmi les ratons laveurs individuels piégés soumis à une nécropsie, des résultats positifs ont été obtenus chez 57 des 114 animaux capturés. La comparaison d’une seule coproscopie à la norme étalon de l’observation de vers adultes dans le petit intestin avait une sensibilité de 78,9 % et une spécificité de 92,9 %. Cette étude suggère que le portage de Baylisascaris procyonis est répandu chez les ratons laveurs de l’écosystème urbain de Winnipeg. Les latrines de ratons laveurs à Winnipeg devraient être traitées comme des sites infectieux et des efforts devraient être déployés pour limiter l’accès à ces sites aux animaux de compagnie et aux personnes à risque.

(Traduit par Isabelle Vallières)

Introduction

Populations of raccoons harboring Baylisascaris procyonis (Nematoda, Family Ascarididae) in major urban areas are a potential source of zoonotic spread to humans. Raccoons adapt readily to human habitation and may defecate in close proximity to homes, potentially putting large numbers of infective eggs in the immediate environment of children and others playing or working in yards, parks, playgrounds, and similar environments (1). Heavily infected raccoons may shed millions of eggs daily. This is of particular importance because human exposure to Baylisascaris is primarily through the fecal-oral route and risk of infection is proportional to the number of eggs in the environment (2,3).

Baylisascaris procyonis is a species-adapted ascarid found primarily in the small intestinal tract of raccoons. Infection is generally subclinical in the definitive host and there is no tissue migration phase in raccoons. In raccoons, infection with B. procyonis can be confirmed through the recovery and identification of the adult worms (postmortem examination) or by fecal flotation (live animal) to identify characteristic ascarid eggs in the feces (4,5). The eggs become infective several weeks post-expulsion and are highly resistant to common chemical disinfection; flame (blow-torch) disinfection of raccoon enclosures is recommended (4).

Baylisascaris procyonis is considered a common cause of clinical larva migrans in animals sharing raccoon ecosystems, and it is usually associated with fatal or severe neurological disease (4–7). Small rodents and birds are considered most susceptible, primarily due to the larger ratio of larval mass to brain tissue mass with low dose infections (5).

More recently, the zoonotic potential of B. procyonis has become evident. In its most severe zoonotic form, B. procyonis is a cause of fatal or neurologically devastating neural larva migrans (NLM) in infants and young children. Characteristically, B. procyonis NLM presents as acute eosinophilic meningoencephalitis. Epidemiologic studies suggest that pica or geophagia and exposure to infected raccoons or environments contaminated with their feces are the most important risk factors for human infection (8,9). To date, despite treatment, neurological outcome is dismal in the overwhelming majority of documented cases, attributed in part to the large larval size of the tissue migratory phase and the vigorous migration (8,9). In intermediate hosts, B. procyonis larvae, unlike Toxocara larvae, molt and grow as they migrate through the tissues, increasing in length from about 300 μm to 1500–1900 μm. Larvae continue to migrate in the tissues until they become encapsulated within eosinophilic granulomas (4).

Raccoons repeatedly use specific geographic locations for defecating. These latrines are generally on elevated horizontal surfaces and readily recognizable (1,2,10,11). The prevalence of B. procyonis in North American raccoons varied between 0 and 100% in 33 studies recently reviewed (8) and has been identified as a cause of animal loss in the Assiniboine Park Zoo (Winnipeg) (12). No previous study has been done in Winnipeg to evaluate the presence of B. procyonis in raccoons. This study was initiated, therefore, to estimate the prevalence of B. procyonis carriage in raccoons living within the boundaries of Winnipeg, and to examine the degree to which B. procyonis carriage is related to geographic location, seasonality, and age and weight of the animal. The study also examined the performance of fecal flotation versus postmortem examination in determining B. procyonis carriage in nuisance raccoons and to determine whether latrines maintain stable B. procyonis status over repeated testing.

Winnipeg is a prairie city with a population of 670 000, covering 625 km2, centered on the junction of 2 major and 1 minor slow-flowing river systems, and within the northern range of raccoon distribution in North America (13,14).

Materials and methods

A survey of latrines and trapped raccoons was conducted from May to August 2007. Latrines were identified by ground searching in response to complaints made to the Winnipeg City office of Manitoba Conservation, of nuisance raccoons in urban areas. Fecal piles < 1 m apart were considered to be from the same latrine.

Feces appearing to be most recently deposited were collected from each latrine, or representative portions of each recognizable fresh scat were collected and placed in plastic bags and labeled. Where possible, 3 samples were collected per latrine site per sampling. Disposable rubber gloves were used in sampling and the sample was collected by inverting a plastic bag over the sample. Alcohol-based hand disinfectant was used between latrine locations and thorough hand washing with soap and water was practiced when available.

All samples were examined for B. procyonis eggs by gravitational fecal flotation (modified Sheather’s Solution, SG 1.25–1.27) (15) and 2 slides were examined using a light microscope for each sample. Baylisascaris procyonis eggs were identified based on their size and morphologic characteristics (11,16). This test protocol has not been validated in our laboratory for this species of nematode. The eggs were not classified as to infectivity as there was an attempt to collect only fresh feces that would contain only non-embryonated (non-infective) eggs (9).

Where possible, latrine sites were re-sampled at an interval of approximately 3 wk. Re-sampling was not possible where the original latrine had been washed out, was submerged by rising water, or was no longer actively used by raccoons at the time of repeated visit. Only fresh fecal deposits at latrine locations were sampled. In addition, some latrine locations were identified late in the collection period and were not re-sampled.

As part of an established trap and removal program, 114 nuisance raccoons were live-trapped and humanely euthanized. The fresh carcasses of these animals were delivered to the veterinary diagnostic laboratory for postmortem examination. Individual carcasses were weighed, sexed, and age classified, by tooth wear, as juvenile or adult specimens. A fecal sample was removed from the rectum and processed as per latrine fecal samples. The animal was examined postmortem with specific attention given to the gastrointestinal tract, which was opened from the duodenum to the rectum. The individual raccoon carcass was considered infected if roundworms, phenotypically consistent with B. procyonis, as previously described (16), were visible in the lumen of the gut, and uninfected if the intestine was free of ascarids.

Data collected during the study were entered into an Excel spreadsheet (Microsoft, Redmond, California, USA). Arc-GIS 9.2 (Environmental Systems Research Institute, Redlands, California, USA) was used to geocode and map the locations of latrines and live-trapped nuisance raccoons. Latrine locations were collected in the field using a hand-held Geographic Positioning System receiver (GPSMAP 76; Garmin International, Olathe, Kansas, USA); locations of trapped nuisance raccoons were provided by Manitoba Conservation and geocoded against a street network file for Winnipeg.

To determine if B. procyonis positive rates varied by season, chi-squared analysis (Open Epi 2.2.1 Dean AG, Sullivan KM, Soe MM) was used to determine whether latrine and necropsy observations made prior to or including July 15 differed significantly from observations made after July 15. This date was chosen as roughly the median date of sample collection. To determine if B. procyonis positive rates differed significantly by age, gender, and weight in live captured raccoons, univariate Poisson regression analysis (Number Cruncher Statistical System, 2004, Kaysville, Utah, USA) was used. Assessment of the performance of fecal floatation versus postmortem examination in determining B. procyonis carriage was undertaken using simple chi-squared and sensitivity and specificity analyses (17). Cohens’ kappa (Stata 8.0; StataCorp LP, College Station, Texas, USA) was employed to assess the reliability/stability of positive latrine status on those latrines subjected to repeat testing.

Results

Eighty-nine fecal samplings (up to 3 samples per latrine location) were collected from 52 geographically distinct latrine sites. The results are summarized in Table 1. Twenty-six of the 52 latrine locations were positive once or more. Fecal flotation of latrine-collected samples was positive at the latrine level in 33 (37%) of 89 samplings. Sixty-one (53.5%) of the 114 nuisance raccoon samples collected were positive for B. procyonis on either fecal or postmortem assessment.

Table 1.

Seasonality of apparent Baylisascaris procyonis carriage by latrine and postmortem evaluation

| Fresh feces from latrine collection

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Test positive | Total | Positive rate (%) | 95% CIa | |

| Latrinesb | 26 | 52 | 50.0 | 35.81–64.19 |

| Samples | ||||

| Pre July 15 | 24 | 60 | 40 | 27.56–53.46 |

| Post July 15 | 9 | 29 | 31.03 | 15.28–50.83 |

| All periods | 33 | 89 | 37.07 | 27.07–47.97 |

| chi-squarec = 0.6736 (P = 0.4118) | ||||

| Necropsies and fecal flotation on samples from individual animals

| ||||

| Positive on either necropsy or flotation | Total | Positive rate | 95% CI | |

| Pre July 15 | 31 | 49 | 63.27 | 48.29–76.58 |

| Post July 15 | 30 | 65 | 46.15 | 33.7–58.97 |

| All periods | 61 | 114 | 53.5 | 44.32–62.5 |

| chi-square = 3.288 (P = 0.06978) | ||||

CI — confidence intervals: Mid-P Exact.

Test positive indicates that fresh feces from the latrine was positive on one or more samples.

Chi-squared analysis: uncorrected chi-square, two-tailed test of significance.

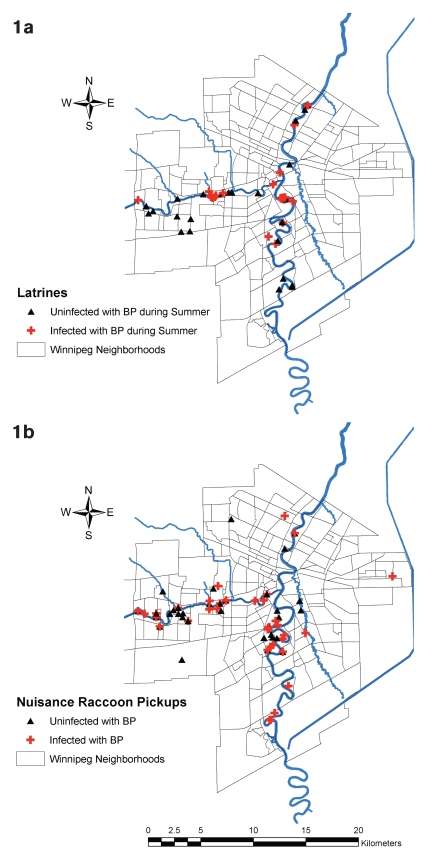

Raccoon latrines (Figure 1a) and nuisance raccoons (Figure 1b) were widely dispersed geographically in Winnipeg but appeared, by visual inspection of the mapped locations, to be closely associated with the 2 major rivers running through Winnipeg. Latrines and nuisance raccoons positive for B. procyonis carriage appeared to be distributed relatively evenly in relationship to the location of study samples (were not disproportionately concentrated in certain areas). No spatial scan statistic was used to more formally confirm this visual impression.

Figure 1.

Location of raccoon latrines (image 1a, n = 52) and nuisance raccoons (image 1b, n = 114) in relation to major waterways and Winnipeg neighborhoods. Blue lines are waterways. The major rivers are the Assiniboine flowing eastward into the Red River which flows north. The Seine River is significantly smaller and flows from the south-east, to end at the Red River just north of the forks with the Assiniboine. The blue line to the east of the city is the Winnipeg Floodway. Light grey lines delineate Winnipeg neighborhoods. If a latrine was positive on either sampling it was mapped as positive (see text).

When comparing samples collected prior and subsequent to July 15, there was no significant difference in B. procyonis positive rates for latrine samples, nuisance raccoons, or latrine/nuisance raccoons combined (Table 1). The rate of B. procyonis carriage was 3.93 times higher (P < 0.05) (Prevalence Rate Ratio) (18) in adult nuisance raccoons compared with juveniles, and 7.25 times higher (P < 0.05) in raccoons weighing more than 2.75 kg compared with those weighing < 2.75 kg. Baylisascaris procyonis positive rates did not differ significantly by gender.

Feces from 113 euthanized raccoons (1 fecal sample result was missing from a postmortem negative raccoon) were positive in 49 animals; 57 postmortem examinations revealed the presence of B. procyonis (Table 2). Twelve animals had ascarids in the intestine but were fecal negative on a single test; 4 animals were fecal positive but no ascarids were found on postmortem examination. Intestinal worms were examined by stereoscopic microscope and were identified as B. procyonis (16). Using postmortem examination as the gold standard, detection of B. procyonis using fecal flotation had a calculated sensitivity and specificity of 78.9% and 92.9%, respectively.

Table 2.

Comparison of single fecal flotation (rectal feces) and postmortem intestinal dissection and the visualization of adult worms

| Postmortem

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Fecal flotation | Positivea | Negative | Total |

| Positiveb | 45 | 4 | 49 |

| Negative | 12 | 52 | 64 |

| Total | 57 | 56 | 113 |

Positive samples were those carcasses in which adult ascarids compatible with Baylisascaris procyonis were found on postmortem examination.

Fecal flotation was considered positive if a single ascarid egg was found.

Thirty-six of the 52 latrine locations were sampled twice during the study. Although the number of positive sites was identical on each sampling round (13 out of 36), the Kappa value of 0.2776 indicated a low level of agreement between the first and second sampling test for each latrine location.

Discussion

This study was limited by opportunistic sampling of free-roaming wildlife, while locations of latrines were driven by nuisance complaints. However, it was demonstrated for the first time that there is significant B. procyonis infection of the urban raccoon population in Winnipeg, as assessed through an analysis of fresh raccoon feces deposited at latrine sites (37.1%) and through postmortem examination of nuisance raccoons (53.5%). No previous study of the positive rate of B. procyonis has been carried out in this population and a nearby raccoon population at similar latitude in Saskatchewan was found to be negative (19). This project was initiated subsequent to the identification of B. procyonis as the recent cause of death of several zoological specimens housed at the Assiniboine Park Zoo in urban Winnipeg (12).

Study results demonstrated that B. procyonis infection in the Winnipeg raccoon population is pervasive, with no significant variation in infection rates across season, geography, or gender. The study did demonstrate, however, that there were significantly higher rates of B. procyonis in older and heavier animals, which is in contrast to other studies that have found a higher prevalence in juveniles (7) or no difference (20). From a methodological perspective, the study also demonstrated that, although repeated latrine sampling of fresh feces using fecal floatation does not give a stable assessment of latrine infection status across time, fecal flotation performs well against postmortem intestinal dissection at the level of the individual animal in populations with relatively high prevalence of infection.

In a previous study, 72 road-killed raccoons were collected year-round from multiple midwestern states (Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, and Wisconsin). Baylisascaris procyonis adults were identified in 47 animals, while 31 were positive on fecal flotation (21); those results are in general agreement with this study which suggests that fecal flotation is a less sensitive measure of infection compared with postmortem examination.

Winnipeg is within the northern range of the raccoon distribution in North America (13,14). Furbearer harvest data and reports (Manitoba Conservation, unpublished data) indicate that the population densities are greatest in the agricultural, urban, and riparian locales north to approximately 54° N, and drop dramatically in the boreal forest areas. Raccoons have been reported beyond this latitude, including near Thompson, Manitoba (latitude: 55° 45′).

Other populations of raccoons have been identified without detectable levels of B. procyonis on Key Largo, Florida (22) and in Japan (23). The near 50% positive rate found in Winnipeg raccoons is similar to the 61% positive rate found in postmortem examination of 82 raccoons from the lower mainland British Columbia (24) and somewhat less than rates of between 72% and 82% reported from the midwestern United States (7).

Seasonal variance in eggs per gram of feces collected from latrines has been documented in California (25) and the upper mid-west USA (21). A study in New York showed pronounced seasonality of egg shedding where, in an 11-month continuous collection period, 80% of positive samples were collected in September, October, and November (26). Raccoons in Manitoba, unlike those in more temperate regions of the United States, are largely inactive from mid-October to mid-March (27). This study did not detect a temporal variation in egg shedding, and even if this occurs, the complete seasonal period of time raccoons are active in Winnipeg was not covered. Based on the 1st spring appearance of neonatal raccoons, breeding in Winnipeg takes place by mid-February, when warming trends begin.

Evidence of pseudo-infection was found in the group of animals examined through postmortem, where the 4 false-positive fecal tests (Table 2) can be explained by non-embryonated eggs being eaten and passed undamaged in the feces. It is also possible that Toxacara eggs may have been misidentified as B. procyonis.

Male raccoons have poorer winter survival, larger home range, and in rural Manitoba, form dyads (13) or bachelor groups (28) compared with the solitary social behavior of females. Contact rate has been demonstrated to increase the parasite load and diversity in raccoons in southern New York State (29). However, these behavioral differences, if present in this urban population, did not result in a significantly different gender-based parasite load of individuals.

The results suggest, not unexpectedly, that the raccoon population in Winnipeg is concentrated adjacent to the 2 major rivers running through the city and B. procyonis infection is widespread within the raccoon population. There has been recent demonstration of patent infection in dogs (16,30). Adaptation of B. procyonis to dogs would likely provide a greatly enhanced zoonotic risk, and contact between dogs and raccoons and raccoon feces in neighborhoods bordering Winnipeg’s rivers should be prevented where possible.

The veterinary community and wildlife enthusiasts should assist in making the public aware of the potential risks of exposure to raccoons and raccoon feces. Raccoons are prohibited as pets in Manitoba and should be considered a significant public health risk in all jurisdictions. Raccoons kept for zoological display, as well as for research or as teaching specimens should be routinely evaluated for B. procyonis infection and treated as necessary. Screening and treatment of raccoons may not be sufficient to prevent exposure, since eggs survive for a long period of time in the environment and the likelihood of re-infection is high. Rehabilitation of injured raccoons should be strongly discouraged for the protection of humans and wildlife in rehabilitation centers. The public should be discouraged from feeding raccoons and should ensure that possible food sources (such as pet food, water, and garbage) are protected from raccoon access. Further study of the impact of larval B. procyonis infection on human health is warranted. A better understanding of the urban ecology of raccoons and the natural host parasite relationship of B. procyonis infection is also desirable.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the laboratory support of Chris Link-Muirhead, Keri Martin, Irene Bayne, and Cheryl Friday who examined the slides and the adult ascarids and the help and laboratory oversight of Dr. Neil Pople. The authors are also grateful for the support of Melissa R. Keuhn and Mesfin Negasi for assistance in handling and evaluating postmortem cases.

Footnotes

This paper was made possible, in part, by The Manitoba Student Temporary Employment Program (STEP), Manitoba Education, Citizenship and Youth.

Use of this article is limited to a single copy for personal study. Anyone interested in obtaining reprints should contact the CVMA office ( hbroughton@cvma-acmv.org) for additional copies or permission to use this material elsewhere.

References

- 1.Murray WJ. Human infections caused by the raccoon roundworm, Baylisascaris procyonis. Clin Microbiol News. 2002;24:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sorvillo F, Ash LR, Berlin OGW, Yatae J, Degiorgio C, Morse SA. Baylisascaris procyonis: An emerging helminthic zoonosis. Emerg Infect Dis. 2002;8:355–359. doi: 10.3201/eid0804.010273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gavin PJ, Kazacos KR, Shulman ST. Baylisascariasis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2005;18:703–718. doi: 10.1128/CMR.18.4.703-718.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kazacos KR, Boyce WM. Baylisascaris larva migrans. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, Zoonosis Update [Monograph on the Internet] [Last accessed June 8, 2009];1995 Available from http://www.avma.org/reference/zoonosis/znaylis.asp. [PubMed]

- 5.Kazacos KR. Iowa: Iowa State Univer Pr; 2001. Baylisascaris procyonis and related species. In: Samuel WM, Pybus MJ, Kocan AA, eds. Parasitic Diseases of Wild Mammals. 2nd ed. Ames; pp. 301–341. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stringfield CE, Sedgwick CJ. Baylisascaris: A zoo-wide experience. Proc Am Assoc Zoo Vet. 1997:73–77. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kazacos KR, Boyce WM. Baylisascaris larva migrans. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1989;195:894–903. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wise ME, Sorvillo FJ, Shafir SC, Ash LR, Berlin OG. Severe and fatal nervous system disease in humans caused by Baylisascaris procyonis, the common roundworm of raccoons: A review of current literature. Microbes Infect. 2005;7:317–323. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2004.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kazacos KR. Protecting children from helminthic zoonoses. Contemp Pediatr. 2000;17(Suppl):1–24. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Page LK, Swihart RK, Kazacos KR. Implications of raccoon latrines in the epizootiology of Baylisascariasis. J Wildl Dis. 1999;35:474–480. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-35.3.474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roussere GP, Murray WJ, Raudenbush CB, Kutilek MJ, Levee DJ, Kazacos KR. Raccoon roundworm eggs near homes and risk for larva migrans disease, California communities. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003;9:1516–1522. doi: 10.3201/eid0912.030039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thompson AB, Glover GJ, Postey RC, Sexsmith JL, Hutchison TWS, Kazacos KR. Baylisascaris procyonis encephalitis in Patagonian conures (Cyanoliseus patagonus), crested screamers (Chauna torquata), and a western Canadian porcupine (Erethizon dorsatum epixanthus) in a Manitoba zoo. Can Vet J. 2008;49:885–888. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pitt JA. University of Saskatchewan; 2006. The edge of a species range: Survival and space use patterns of raccoons at the northern periphery of their distribution. [MSc thesis] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lariviere S. Range expansion of raccoons in the Canadian prairies: Review of hypotheses. Wildl Soc Bull. 2004;32:955–963. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dryden MW, Payne PA, Ridley R, Smith V. Comparison of common fecal flotation techniques for the recovery of parasite eggs and oocysts. Vet Therap. 2005;6:15–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Averbeck GA, Laursen JR, Vanek JA, Strombeg BE. Differentiation of Baylisascaris species, Toxicara canis, and Toxicara leonine infections in dogs. Compend Contin Edu Pract Vet. 1995;17:475–479. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martin WS, Meek AH, Willeberg P. Veterinary Epidemiology: Principles and Methods. 1st ed. Ames, Iowa: Iowa State Univer Pr; 1987. pp. 63–72. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zocchetti C, Consonni D, Bertazzi PA. Relationship between prevalence rate ratios and odds ratios in cross-sectional studies. Int J Epidemiol. 1997;26:220–223. doi: 10.1093/ije/26.1.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoberg EP, McGee SG. Helminth parasitism in raccoons, Procyon lotor hirtus Nelson and Goldman, in Saskatchewan. Can J Zool. 1982;60:53–57. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kerr CL, Henke SE, Pence DB. Baylisascarisis in raccoons from southern coastal Texas. J Wildl Dis. 1997;33:653–655. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-33.3.653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Page LK, Gehrt SD, Titcombe KK, Robinson NP. Measuring the prevalence of raccoon roundworm (Baylisascaris procyonis): A comparison of common techniques. Wild Soc Bull. 2005;33:1406–1412. [Google Scholar]

- 22.McCleary RA, Foster GW, Lopez RR, Peterson MJ, Forrester DJ, Silvy NJ. Survey of raccoons on Key Largo, Florida, USA, for Baylisascaris procyonis. J Wild Dis. 2005;44:250–252. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-41.1.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sato H, Suzuki K. Gastrointestinal helminthes of feral raccoons (Procyon lotor) in Wakayama prefecture, Japan. J Vet Med Sci. 2006;68:311–318. doi: 10.1292/jvms.68.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ching HL, Leighton BJ, Stephen C. Intestinal parasites of raccoons (Procyon lotor) from southwest British Columbia. Can J Vet Res. 2000;64:107–111. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Evans RH. Baylisascaris procyonis (Nematoda: Ascaridoidea) eggs in raccoon (Procyon lotor) latrine scats in Orange County, California. J Parasitol. 2002;88:189–190. doi: 10.1645/0022-3395(2002)088[0189:BPNAEI]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kidder JD, Wade SE, Richmond ME, Schwager SJ. Prevalence of patent Baylisascaris procyonis infection in raccoons (Procyon lotor) in Ithaca, New York. J Parasitol. 1989;75:870–874. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zeveloff SI. Raccoons: A natural history. The Smithsonian Institution; Washington, DC: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gehrt SD, Fritzell Resource distribution, female home range dispersion and male spatial interactions: Group structure in a solitary carnivore. Anim Behav. 1998;55:1211–1227. doi: 10.1006/anbe.1997.0657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wright AN, Gompper ME. Altered parasite assemblage in raccoons in response to manipulated resource availability. Oecologia. 2005;144:148–156. doi: 10.1007/s00442-005-0018-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bowman DD, Ulrich MA, Gregory DE, Neumann NR, Legg W, Stansfield D. Treatment of Baylisascaris procyonis infections in dogs with milbemycin oxime. Vet Parasitol. 2005;129:285–290. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2004.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]