Abstract

Bacterial type III secretion machines have adapted to carry out numerous functions, ranging from locomotion to protein delivery into nucleated cells. One of the most intriguing issues is the source of energy that fuels their activities. Despite recent advances, there are still many questions to be resolved.

Type III secretion systems (TTSSs) are specialized multiprotein machines that mediate the transfer of effector proteins from the cytoplasm of pathogenic or symbiotic bacteria directly into nucleated cells1,2. These machines are thought to be evolutionarily related to bacterial flagella, and indeed they do share some structural and functional features3. However, these two types of machines have evolved to carry out completely different functions: bacterial propulsion for flagella and protein delivery into nucleated cells for type III secretion machines. Consequently and not surprisingly, these two types of machines show important differences, particularly in the architecture and components of the structures that carry out those specific functions: the flagellar apparatus and the needle complex. Unfortunately, owing to poor nomenclature and for historical reasons, there is often confusion about what constitutes a type III secretion machine and whether the flagella should be identified as such. Proteins targeted to these machines are thought to travel through a narrow channel (∼25–30 Å in diameter) that traverses the entire needle complex or flagellar structure. In the case of type III secretion machines, these proteins are presented to a ‘translocase complex’ located at the tip of the needle complex (also composed of type III secreted proteins), which mediates their direct delivery through the targetcell membrane. In the case of flagella, the proteins required to make the different substructures of this organelle are transported through the central channel of the apparatus to their site of incorporation on the growing distal end. Nevertheless, these two types of machines do share commonalities, particularly in the function and components of the ancillary machinery required for the recognition of proteins targeted to these machines and their initiation into the secretion pathway. These components include a number of inner-membrane proteins that are thought to serve as a ‘gate’ or ‘channel’, which allows passage through the bacterial inner membrane, and an ATPase (and an associated regulatory protein), which functions in the recognition and unfolding of proteins destined to travel this pathway. In addition, a family of customized chaperones contributes to the secretion process by targeting the cognate proteins to the secretion machine and/or keeping them in a ‘secretion-competent’ state4,5.

One of the issues that has captured the attention of the field for quite some time is how these machines are energized. Pioneering work by Koshland and collaborators more than 30 years ago first suggested that the proton motive force (PMF) was involved in flagellar assembly, because ubiquinone-deficient mutants of Escherichia coli lack flagella6. Later, Galperin et al. investigated this issue directly and showed that dissipating the PMF by the addition of uncouplers effectively halted flagellar assembly7. Furthermore, Galperin et al. demonstrated that both the electrical (Δψ) and chemical (ΔpH) components of the PMF were involved in flagellar assembly. Later studies by Wilharm et al. revisited the issue and extended these findings to the virulence-associated type III secretion system of Yersinia spp., for which PMF is also required8. Taken together, these early studies established that PMF has a role in type III secretion and flagellar assembly. One caveat of these results is that uncouplers have a profound effect on bacterial physiology and, more specifically, on the sec protein-secretion machinery, which is strictly dependent on the PMF9. Because the assembly of the type III secretion and flagellar organelles requires the sec machinery (many of the essential components are secreted via this pathway and therefore have sec secretion signals), the interpretation of experiments using inhibitors of the PMF is challenging.

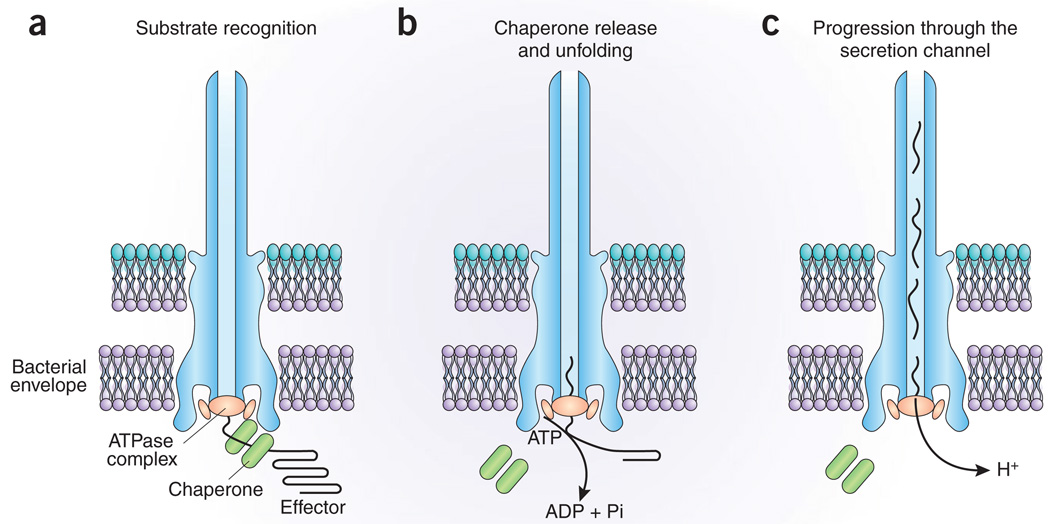

In any case, if PMF is required for the function of these machines, is it the only energizer? In the process of characterizing the components of the flagellar export apparatus at the molecular level, the laboratory of the late Bob Macnab identified FliI, a component of the flagellar export apparatus with sequence similarity to the catalytic β subunit of the bacterial F0F1 ATPase. They also identified FliH, a protein involved in the regulation of FliI by mechanisms that are poorly understood10. This finding raised the possibility that ATP hydrolysis may also be involved in energizing at least some aspects of the process that leads to the export of the flagellar components. The absolute requirement of FliI for flagellar assembly coupled with the discovery of close homologs in other type III secretion systems gave further support to this idea11–13. Since then, a more complete picture of the function of this family of proteins in type III secretion has emerged. Thus, members of this protein family have been shown to hydrolyze ATP12,14, associate with the secretion machine15, recognize the chaperone–secreted protein complex15–18, remove the chaperone from this complex17 and unfold the proteins destined for export so that they can fit the narrow secretion channel17. From all of this work, a model has emerged in which presumably both the PMF and ATP hydrolysis are involved in the secretion process; ATP hydrolysis drives the protein unfolding and presentation of these substrates to the secretion machine, and the PMF drives the progression of proteins through the central channel (Fig. 1). The energy potentially ‘stored’ in partially unfolded polypeptides may also contribute to substrate progression through the channel.

Figure 1.

Model for the energizing of type III secretion machines. (a) Proteins to be secreted (known as ‘effectors’), which are bound to a customized chaperone, are recognized by components of the secretion machinery, including a machine-associated ATPase. (b) The ATPase ‘strips’ the chaperone from the complex, which remains within the bacterial cell, and mediates the unfolding of the effector protein and its initiation into the secretion pathway. ATP hydrolysis energizes this step. (c) Aided by the proton motive force, proteins then travel through the central channel of the machine to reach their final destination. See text for details.

In the latest issue of Nature, two more papers have contributed to this topic19,20. In essence, both papers have confirmed previous studies indicating that the PMF is required for flagellar assembly. Unlike the previous studies7,8, however, Koushik et al. could not confirm a role for the ΔpH component of the PMF in flagellar assembly20. The reasons for this discrepancy were not addressed, but it may be related to differences in the experimental systems used and the challenges associated with addressing this issue with inhibitors that can affect other aspects of bacterial physiology. In addition, these papers report that flagellar assembly can occur in the absence of the ATPase FliI, albeit inefficiently, provided that its regulatory subunit FliH is also absent. Certain suppressor mutants with defects in associated inner-membrane proteins that presumably gate the secretion channel (that is, FlhA and FlhB) further increased the ATPase-independent secretion19. Because the diameter of the secretion channel dictates that substrates destined to travel through this pathway must be unfolded or at least partially unfolded before secretion, this observed ATPase-independent secretion led to the conclusion that the ATPase is not required for the unfolding reaction and that the PMF must be sufficient to drive the entire process19. However, there are other, arguably more likely, explanations that could account for the results obtained. For example, cross-talk with other unfoldases was not completely ruled out. Although removal of unfoldases from other secretion systems did not seem to have an effect on FliI-independent secretion, cross-talk with other unfoldases encoded by Salmonella spp. was not addressed. As the mechanisms of recognition by unfoldases may well share similarities with the mechanisms of recognition by TTSS machines, this possibility cannot be ruled out21. Furthermore, because some of the signals required for type III secretion consist of stretches of unstructured amino acids, it is also possible that, at low-efficiency, some substrates can be initiated into this ‘more permissive’ ATPase-independent pathway. This, however, would not necessarily mean that this fortuitous substrate engagement would be relevant in the context of the wild-type machine, in which the presence of the ATPase is essential for secretion. Therefore, a combination of a more permissive machine generated by the mutations and/or potential cross-talk with other unfoldases can account for the results obtained. The fact that the simultaneous removal of the regulatory subunit FliH, which may in the absence of FliI block the entrance to the gate of the channel, was required to observe the low-level ATPase-independent secretion further supports these ideas. It has been experimentally demonstrated that type III secretion ATPases can unfold substrates in vitro in a catalytic-dependent manner17. Therefore, until direct evidence is obtained that the PMF can mediate the unfolding of substrates, along with a better understanding of what this inefficient ATPase-independent secretion caused by the introduction of mutations really means, the conclusion that the PMF is the only energizer of these machines is premature. More likely, and as discussed above, both ATP hydrolysis and PMF are required to energize different steps of the secretion process.

Naturally, many issues are still unresolved. How does the proton gradient energize the progression of substrates through the inner channel? Is it in fact the Δψ or the ΔpH of the PMF that drives the process? How is PMF actually coupled to protein secretion? What is the machinery that mediates this coupling? Do protons move through the secretion channel? If so, how? Does the energy potentially stored during the ATPase-mediated unfolding of secretion substrates contribute to their progression through the secretion channel? Like any good saga, this one is “to be continued…”.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I would like to thank J. Kato and M. Lara-Tejero for useful suggestions and critical reading of this manuscript. Work in the Galán laboratory is supported by grants from the US National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.Galan JE, Wolf-Watz H. Nature. 2006;444:567–573. doi: 10.1038/nature05272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cornelis GR. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2006;4:811–825. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aizawa SI. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2001;202:157–164. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2001.tb10797.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feldman MF, Cornelis GR. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2003;219:151–158. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1097(03)00042-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bennett JC, Hughes C. Trends Microbiol. 2000;8:202–204. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(00)01751-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bar Tana J, Howlett B, Koshland DJ. J. Bacteriol. 1977;130:787–792. doi: 10.1128/jb.130.2.787-792.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Galperin M, Dibrov P, Glagolev A. FEBS Lett. 1982;143:319–322. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(82)80125-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wilharm G, et al. Infect. Immun. 2004;72:4004–4009. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.7.4004-4009.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Keyzer J, van der Does C, Driessen A. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2003;60:2034–2052. doi: 10.1007/s00018-003-3006-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vogler AP, Homma M, Irikura VM, Macnab RM. J. Bacteriol. 1991;173:3564–3572. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.11.3564-3572.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dreyfus G, Williams AW, Kawagishi I, Macnab RM. J. Bacteriol. 1993;175:3131–3138. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.10.3131-3138.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eichelberg K, Ginocchio C, Galán JE. J. Bacteriol. 1994;176:4501–4510. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.15.4501-4510.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Woestyn S, Allaoui A, Wattiau P, Cornelis GR. J. Bacteriol. 1994;176:1561–1569. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.6.1561-1569.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fan F, Macnab RM. J. Biochem. 1996;271:31981–31988. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.50.31981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thomas J, Stafford G, Hughes C. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:3945–3950. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307223101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gauthier A, Finlay BB. J. Bacteriol. 2003;185:6747–6755. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.23.6747-6755.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Akeda Y, Galan JE. Nature. 2005;437:911–915. doi: 10.1038/nature03992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sorg J, Blaylock B, Schneewind O. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:16490–16495. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605974103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Minamino T, Namba K. Nature. 2008;451:485–488. doi: 10.1038/nature06449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koushik P, Erhardt M, Hirano T, Blair DF, Hughes KT. Nature. 2008;451:489–492. doi: 10.1038/nature06497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baker TA, Sauer R. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2006;31:647–653. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2006.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]