Abstract

This study examined the developmental trajectory of anxiety symptoms among 290 boys and evaluated the association of trajectory groups with child and family risk factors and children’s internalizing disorders. Anxiety symptoms were measured using maternal reports from the Child Behavior Checklist (T. M. Achenbach, 1991, 1992) for boys between the ages of 2 and 10. A group-based trajectory analysis revealed 4 distinct trajectories in the development of anxiety symptoms: low, low increasing, high declining, and high-increasing trajectories. Child shy temperament tended to differentiate between initial high and low groups, whereas maternal negative control and maternal depression were associated with increasing trajectories and elevated anxiety symptoms in middle childhood. Follow-up analyses to diagnoses of preadolescent depression and/or anxiety disorders revealed different patterns on the basis of trajectory group membership. The results are discussed in terms of the mechanisms of risk factors and implications for early identification and prevention.

Keywords: childhood anxiety, temperament, emotion regulation, parent–child interaction, maternal depression

Anxiety disorders represent one of the most prevalent forms of childhood psychopathology, with a 12-month prevalence rate ranging from 8.6% to 20.9% (see Costello, Mustillo, Erkanli, Keeler, & Angold, 2003; Kovacs & Devlin, 1998). Childhood anxiety disorders are associated with significant impairment in psychosocial functioning, including peer relations and academic performance (Last, Hansen, & Franco, 1997; Shaffer, Fisher, Dulcan, & Davies, 1996). Moreover, early-onset anxiety disorders are often chronic and are associated with future onset of other disorders such as depression and conduct problems (Cole, Peeke, Martin, Truglio, & Seroczynski, 1998; Kovacs & Devlin, 1998; Zahn-Waxler, Klimes-Dougan, & Slattery, 2000). Despite the prevalence and the potential detrimental consequences of anxiety disorders, little is known about the trajectory of anxiety symptoms in childhood. A better understanding of the developmental course of anxiety symptoms during early and middle childhood is essential for advancing basic research and for providing targets for preventive interventions (Bell, 1986).

In the present study, we examined the trajectories of childhood anxiety from a developmental psychopathology perspective, which holds that psychopathology results from multiple causal influences (Cicchetti & Cohen, 1995; Vasey & Dadds, 2001). From this perspective, anxiety disorders are seen as emerging from multiple developmental pathways that reflect the dynamic interplay between characteristics of children and their environment over time. Adopting such a perspective, the goals of our study were threefold. First, we modeled the developmental course of childhood anxiety using a person-oriented approach that attempts to identify different groups of individuals who follow distinct trajectories. A person-centered approach is critical to understanding heterogeneity in the development of anxiety symptoms in children. Second, we sought to evaluate child and environmental factors that differentiate anxiety trajectory groups. Research on the etiology and maintenance of childhood anxiety has been limited to studying isolated risk and protective factors and relying primarily on questionnaires or interview of child and family functioning (Vasey & Dadds, 2001). This study extends existing knowledge by providing information on the additive effects of multiple factors in the development of child-hood anxiety problems, beginning in early childhood and including observational measures of both child behavior and parent–child interaction. Third, we examined the associations between trajectories of anxiety and children’s later internalizing disorders.

We focused on boys from ethnically diverse, low-income families. Research examining gender differences in the prevalence of childhood anxiety has produced mixed results. Although some have reported higher rates of anxiety symptoms/disorders in girls than in boys (e.g., Lewinsohn, Gotlib, Lewinsohn, Seeley, & Allen, 1998; Roza, Hofstra, van der Ende, & Verhulst, 2003), others suggest that gender differences are small or nonexistent (Costello et al., 2003; Ingram & Price, 2001). Costello and colleagues (2003) reported a 3-month prevalence rate (for 9- to 16-year-olds) of 2.0% for boys and 2.9% for girls, suggesting that boys’ rates of anxiety disorders were still comparable to that of girls. In addition, the nature and consequences of such gender differences are not well understood. Although limited and inconclusive, there is at least some evidence suggesting divergent pathways for boys and girls, which warrant gender-segregated studies of childhood anxiety.

Research on internalizing problems in boys and girls suggests that the gender difference may be partially due to the socialization processes, such that girls’ early problem behavior is more often channeled into internalizing problems (Keenan & Shaw, 1997). Thus, boys who develop anxiety disorders represent a unique population that may be characterized by specific social and emotional processes that are presently poorly understood. We believe that studying trajectories of anxious symptomatology among boys is an important first step that can yield valuable information that ideally could be replicated in a sample with both genders separately.

There is some evidence to suggest that boys are more vulnerable than girls to the effects of suboptimal caregiving environments, particularly in early childhood (Shaw et al., 1998). For example, in three different independent cohorts of young children that ranged from low- to middle-socioeconomic status, for boys, significant associations were found between maternal unreponsiveness during infancy and problem behavior during the toddler and preschool periods. In all three studies, associations were not significant for girls (Martin, 1981; Shaw, Keenan, & Vondra, 1994; Shaw et al., 1998). Whereas fewer studies have tested this association for internalizing problems in general, or anxiety symptoms in particular, it remains to be seen whether boys might show comparably high vulnerability to individual differences in caregiving quality associated with anxiety symptoms, one of the primary goals of the present study.

Additionally, children from low-income families have been underrepresented in studies of psychopathology despite the fact that they show higher risk for all forms of psychopathology, including internalizing problems (Keenan, Shaw, Walsh, Delliquadri, & Giovannelli, 1997). For instance, disadvantaged boys are at elevated risk for depression and suicide in adolescence (Brent, Baugher, Bridge, Chen, & Chiappetta, 1999; Keenan et al., 1997). Given that anxiety disorders tend to co-occur with and developmentally precede depressive disorders, studying trajectories of anxiety among disadvantaged boys may contribute to the understanding of their elevated risk for adverse outcomes.

Trajectories of Childhood Anxiety

Very little research has delineated trajectories of anxious symptomatology in childhood. In the present study, we assume heterotypic continuity in the manifestation of anxiety symptoms, with specific expressions of anxiety symptoms varying at different developmental stages. Although for most children, anxiety and fear are transitory, causing no enduring impairment, for some, anxiety symptoms beginning in childhood persist into adulthood (Last, Perrin, Hersen, & Kazdin, 1996; Ollendick & King, 1994; Sweeney & Pine, 2004).

The limited empirical research on developmental trajectories of anxiety suggests moderate stability in anxiety symptoms throughout middle childhood (e.g., Ialongo, Edelsohn, Werthamer-Larsson, Crockett, & Kellam, 1994, 1995). Côté, Tremblay, Nagin, Zoccolillo, and Vitaro (2002) identified three distinct trajectories in teacher ratings of fearfulness in elementary school children. The majority of children followed either a low or moderate trajectory, whereas a small percentage of children (about 9% boys and 17% girls) followed a stable high trajectory. Other studies have found subgroups of children who demonstrate increasing and/or decreasing trends in anxiety symptoms. In one epidemiological study, Verhulst and van der Ende (1992) reported that small percentages (15% or less) of children (boys and girls), between the ages of 4 and 11, increased or decreased substantially in maternal ratings of anxious/depressed symptoms; they also found a small group (16%) being consistently high and the rest maintaining a level below the median throughout. In light of previous findings, we expected four trajectory groups among boys: a stable low, a persistent high, an increasing, and a declining trajectory. We anticipated that the majority of the boys would follow a stable low or declining trajectory, whereas small groups of boys would follow an increasing or persistently high trajectory.

Risk Factors Associated With Childhood Anxiety

The onset and persistence of childhood anxiety are associated with both child and family risk factors (Sweeney & Pine, 2004; Vasey & Dadds, 2001). Etiological theories of childhood anxiety have focused on children’s personal characteristics, interpersonal factors, and a family history of psychopathology (Ollendick, Shortt, & Sander, 2004; Wood, McLeod, Sigman, Hwang, & Chu, 2003). In the present study, we examined how child temperament, emotion regulation, attachment security, parenting behavior, and maternal depression were associated with different trajectories of childhood anxiety symptoms.

Shyness and Anxiety

Certain temperamental characteristics may predispose children to experience anxiety symptoms in early childhood. Behavioral inhibition, defined as the tendency to react to novelty with unusual fear, cautiousness, and withdrawal (Kagan, Reznick, & Snidman, 1988), has been most extensively studied in relation to concurrent and later anxiety symptoms (Hirshfeld-Becker, Biederman, & Rosenbaum, 2004). Inhibited children also tend to exhibit high heart rates and low heart rate variability, high salivary cortisol level, and frequent fears and somatic and behavioral symptoms that are often associated with anxiety (Kagan, Snidman, Zentner, & Peterson, 1999; Marshall & Stevenson-Hinde, 1998; Schmidt, Fox, Schulkin, & Gold, 1999). Behavioral inhibition assessed during early childhood has been associated with increased risk for later anxiety disorders (Biederman et al., 2001, 1993, 1990), particularly social phobia (Gladstone, Parker, Mitchell, Wilhelm, & Malhi, 2005; Hirshfeld-Becker et al., 2004). The temperamental construct of shyness, closely related to behavioral inhibition, is a form of inhibition in novel social situations (Hirshfeld-Becker et al., 2004; Kagan, 1999). Observed global shyness at age 4.5 was found to be associated with elevated levels of trait anxiety at age 10 (Fordham & Stevenson-Hinde, 1999). In a longitudinal study, Prior, Smart, Sanson, and Oberklaid (2000) reported that parental ratings of shy-inhibited temperament at ages 3–4 were associated with a twofold increased risk of anxiety disorders at 13–14 years of age. There has been some indication that inhibited temperament tends to be more stable from infancy to middle childhood for girls than for boys; however, its relationships with later anxiety symptoms are present for both genders (Albano & Krain, 2005). We expected that shyness in toddler boys would be associated with heightened anxiety symptoms across early and middle childhood.

Emotion Regulation and Anxiety

There is a growing interest in the role of emotion regulation in the development of anxiety symptoms and disorders (Bosquet & Egeland, 2006; Muris, 2006). Grolnick, Bridges, and Connell (1996) outlined a set of behaviors for regulating emotion that are commonly used by preschool-age children. The first set of strategies includes behaviors aimed at shifting attention from a distressing stimulus toward a nondistressing stimulus (Derryberry & Rothbart, 1988). Observational studies of infants and young children show that attention shifting, or refocusing attention on a nondistressing stimulus, is an effective strategy that has been associated with lower levels of subsequent distress (Buss & Goldsmith, 1998; Calkins & Johnson, 1998; Grolnick et al., 1996). Conversely, maintaining or increasing attentional focus on a distressing stimulus has been found to be a maladaptive approach to regulating negative emotion. Research with infants and toddlers has shown that sustained focus on a frustrating stimulus, such as staring at a delayed prize, is associated with generalized distress (Gaensbauer, Connell, & Schulz, 1983; Gilliom, Shaw, Beck, Schonberg, & Lukon, 2002; Grolnick et al., 1996).

Anxious children appear to be less skilled in the flexible control of attention, which is a crucial factor in the ability to manage emotion (Derryberry & Rothbart, 1988; Lonigan, Vasey, Phillips, & Hazen, 2004). Perhaps as a result of low attentional control, anxious children may be more likely to maintain or increase attentional focus on the distressing stimulus. The related constructs of rumination and involuntary engagement coping have both been linked to internalizing in older children and adolescents (Compas, Connor-Smith, Saltzman, Thomsen, & Wadsworth, 2001; Connor-Smith, Compas, Wadsworth, Thomsen, & Saltzman, 2000; Nolen-Hoeksema, 1994; Silk, Steinberg, & Morris, 2003). Anxious children also tend to report lower levels of self-efficacy in regulating emotion (Kortlander, Kendall, & Panichelli-Mindel, 1997; Suveg & Zeman, 2004). Anxious children may thus use more passive strategies for regulating emotion and may rely more on parents for assistance. We therefore hypothesized that strategies representing lack of active self-regulation, such as negative focus on delay and passive/dependence, would be associated with increased risk for persistent or increasing trajectory of anxiety symptoms.

Insecure Attachment and Anxiety

Attachment theory posits that a secure attachment relationship with parents is critical for children to develop the capacity to regulate fear and anxiety in threatening or difficult circumstances (Bowlby, 1973; Thompson, 2001). Insecure attachment has been hypothesized as one of the bases for anxiety problems because of children’s uncertainty about the availability of the attachment figure and their heightened vigilance in monitoring the environment. Some studies have established a direct link between insecure attachment and later anxiety problems (e.g., Cassidy & Berlin, 1994). Relations between childhood anxiety and subtypes of insecure attachment have also been explored, and the findings are inconclusive—some suggesting a link with insecure-resistant attachment (e.g., Warren, Huston, Egeland, & Sroufe, 1997), whereas others finding an association with insecure-disorganized attachment (e.g., Shaw, Keenan, Vondra, Delliquadri, & Giovanelli, 1997). Bradley (2000) has argued that insecure-avoidant attachment may also lead to anxiety disorders because of its association with mothers’ rejecting parenting in times of distress. In the present study, we focused on the relation between insecure infant–mother attachment and later anxiety symptoms, with the expectation that boys who were insecurely attached would exhibit trajectories of elevated anxiety symptoms during childhood.

Maternal Depression and Child Anxiety

A family history of both depressive and anxiety disorders has been found to be associated with anxiety disorders in offspring. Children with depressed parents are at high risk for anxiety disorders (Beidel & Turner, 1997; Rosenbaum et al., 2000; Wickramaratne & Weissman, 1998). Major depression appears to confer a risk for both anxiety and depression in first-degree relatives, with some evidence of a shared genetic pathway (Eley & Stevenson, 1999; Silberg, Rutter, & Eaves, 2001; Williamson, Forbes, Dahl, & Ryan, 2005). In a recent multigenerational study, Weissman et al. (2005) found that among families with a depressed grandparent, children who also had a depressed parent were five times more likely to experience an anxiety disorder than children without a depressed parent. Similarly, Beidel and Turner (1997) found that children of parents with depressive disorders, anxiety disorders, and mixed anxiety/depression disorders all were more than five times more likely to develop anxiety disorders than children of healthy parents, with no differences among parental diagnostic groups with regard to the rate of children’s anxiety disorders. Some researchers have argued that anxiety and depression may represent one underlying disorder with age-dependent expression (Williamson et al., 2005). Biederman et al. (2006), however, found that parental panic disorder (without comorbid depression) conveyed specific risk for child anxiety disorder, whereas parental depression (without comorbid panic disorder) conveyed specific risk for child depressive disorder. They cautioned that the link between parental depression and child anxiety previously demonstrated could be partly attributable to high rates of comorbid depression and anxiety among parents.

One mechanism through which depressed and/or anxious parents may influence the development of anxiety disorders in their offspring is through modeling. Modeling is an important mechanism through which children acquire fearful behaviors (Gerull & Rapee, 2002). Modeling of anxious behaviors, such as avoidance and catastrophizing, has been shown to play a role in the transmission of anxiety from anxious parents to their offspring (Moore, Whaley, & Sigman, 2004). Depressed parents, who often have comorbid anxious symptomatology, may also model anxious behaviors for their children. In addition, offspring of depressed parents may model the withdrawn and passive behaviors that are often exhibited by depressed parents during parent–child interactions (e.g., Cox, Puckering, Pound, & Mills, 1987; Kochanska, Kuczynski, Radke-Yarrow, & Welsh, 1987). Evidence for this social learning mechanism also comes from observational studies of parent–child interactions in which the infants and young children of depressed mothers have been found to “match” the mothers’ negative affective behaviors (Breznitz & Friedman, 1988; Field, Healy, LeBlanc, 1989). Through these mechanisms, children with depressed parents may learn to withdraw from and/or avoid stressful and anxiety-provoking situations, further reinforcing their anxious tendencies.

Parental Overcontrol and Anxiety

The most consistent finding in studies of parent–child interaction in the families of children with anxiety disorders is a pattern of parental overcontrol or negative control. Parental negative control is defined as intrusive behavior, excessive regulation of children’s activities, and a minimal level of granting of age-appropriate autonomy (Ginsburg, Grover, Cord, & Ialongo, 2006). Observational studies have shown that parents of children with anxiety disorders engage in excessive control over children’s behaviors and emotions (Hudson & Rapee, 2001; Siqueland, Kendall, & Steinberg, 1996). For example, Hudson and Rapee (2001) found that mothers of children with anxiety disorders gave children more help completing complex cognitive puzzles and were more intrusive with their help during the task than mothers of nonanxious children.

Parental negative control is theorized to increase children’s dependence on parents and decrease children’s sense of autonomy and mastery over the environment (Wood et al., 2003). Lack of mastery further contributes to anxiety by reinforcing biased perceptions of events as out of one’s control (Chorpita & Barlow, 1998). Overcontrolling parents may regulate children’s exposure to potentially fear-evoking experiences with the intention of protecting the child from unwanted anxiety (Kortlander et al., 1997). This pattern further reinforces the child’s anxiety by depriving him or her of mastery of experiences in coping with negative emotion. As some previous research suggests that boys, in early childhood, tend to be more vulnerable than girls to the effects of suboptimal caregiving environments (Shaw et al., 1998), we expected that controlling parenting would be associated with boys’ elevated or increasing anxiety symptoms to the same degree (if not stronger) found in mixed gender studies.

Trajectories of Anxiety Symptoms and Internalizing Disorders

Our final goal was to examine associations between anxiety trajectory group membership and preadolescent anxiety and depressive disorders. Childhood anxiety is strongly associated with recurrence of anxiety problems later in childhood and adolescence (Kovacs & Devlin, 1998; Orvaschel, Lewinsohn, & Seeley, 1995). Mesman and Koot (2001) found that parental ratings of child internalizing behaviors as early as the preschool years were predictive of children’s anxiety and depressive disorders at ages 10–11. Childhood anxiety disorders are also strongly associated with later development of depressive disorders (Last et al., 1996; Lewinsohn, Hops, Roberts, Seeley, & Andrews, 1993; Pine, Cohen, Gurley, Brook, & Ma, 1998). More importantly, anxiety disorders appear to precede the onset of depressive disorders (Kovacs & Devlin, 1998; Kovacs, Gatsonis, Paulauskas, & Richards, 1989). One study found that as many as 85% of depressed adolescents experienced an anxiety disorder prior to the onset of the depression (Rohde, Lewinsohn, & Seeley, 1991). We examined how trajectories of anxiety symptoms were differentially associated with the development of anxiety and depressive disorders in the present study. We hypothesized that boys with increasing and persistently high levels of anxiety during early and middle childhood would demonstrate increased risk for anxiety and depressive disorders as they approached adolescence.

The Present Study

In summary, the present study attempted to (a) identify distinct developmental trajectories of anxiety symptoms in a sample of low-income boys; (b) examine associations between multiple risk factors and boys’ anxiety trajectory group membership. The risk factors included shy temperament; emotion regulation strategies, including sustained focus on frustration and passive/dependent behavior; insecure attachment; maternal depression; and maternal negative control; and (c) examine associations between trajectories of anxiety and subsequent development of clinical anxiety and depressive disorders.

Method

Participants

Data were drawn from an ongoing longitudinal study of vulnerability and resilience among boys of low-income families. Boys were recruited from families who used the Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) program in the Pittsburgh metropolitan area (Shaw, Gilliom, Magin, & Ingoldsby, 2003). Participants were recruited when target children were between 7 and 17 months old. At the time of the first assessment when infants were 1.5 years old, mothers ranged in age from 17 to 43 years (M = 27.9). The sample consisted of approximately 53% European American, 36% African American, 6% Hispanic American, and 5% biracial families. Sixty-five percent of mothers were married or living with partners, 28% were never married, and 7% were separated, divorced, or widowed. Mean per capita family income was $241 per month ($2,892 per year), and the mean socioeconomic status score was 24.8, which is indicative of working-class status (20–29 = semi-skilled workers; Hollingshead, 1975).

During the course of recruitment for over 2 years, 421 families were approached at WIC sites. Of these approached families, 310 (73.6%) participated in the first assessment, whereas 14 (3.3%) declined to participate at the time of recruitment, and an additional 97 (23.0%) declined before the first assessment when target children were 1.5 years old. Of the 310 families seen at the first assessment, 302 had data available at the age-2 assessment. Subsequent laboratory or home assessments were convened when children were ages 3.5, 5, 5.5, 6, 8, and 10, during which time retention rates ranged from 78% to 91%. For the purpose of trajectory modeling, 290 boys who completed assessments at three or more time points between the ages of 2 and 10 were included. The sample size reduced to 228 in the analysis of risk factors for trajectory groups because of missing data in risk factor variables. Children not included due to missing data (n = 62) were compared with participating children on the measure of anxiety symptoms, on which the trajectory was modeled; no differences were found (Fs = 0.00–1.96, ns).

Procedures and Measures

Assessments for this study included maternal ratings of child anxiety symptoms and child shyness, laboratory observation of child emotion regulation and mother–child interaction, and clinical interviews of children and mothers for their diagnoses of psychiatric disorders.

Child anxiety symptoms

Items from the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach, 1991, 1992) were selected to generate scales of anxiety symptoms. The CBCL is a widely used parent-report measure of childhood behavioral problems. Two versions of the CBCL were used, one for when children were 2 and 3.5 years of age (CBCL/2–3) and a second for when children were 5, 5.5, 6, 8, and 10 years old (CBCL/4–18). On the basis of the principle of heterotypic continuity, it was decided to generate two separate scales of anxiety symptoms for the two versions of the CBCL. The items were selected on the basis of (a) Achenbach’s (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2000, 2001) DSM-oriented Anxiety Problems scale, (b) widely used self-report questionnaires for childhood anxiety symptoms such as the Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (MASC; March, Parker, Sullivan, Stallings, & Conners, 1997) and the Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale (SCAS; Spence, 1998), and (c) previous research on anxiety symptoms that focused on early or middle childhood. With the scale for younger children (ages 2–3), we included all items from Achenbach and Rescorla’s (2000) DSM-oriented Anxiety Problems scale, preschool-age version (e.g., clings to adults; upset by separation; too fearful or anxious). In addition, three more items that tap social anxiety were selected from the CBCL: feelings easily hurt; self-conscious; and shy or timid. Similar items were included in the Social Anxiety subscale of the MASC (March et al., 1997). With the scale for older children, we included all items from Achenbach and Rescorla’s (2001) DSM-oriented Anxiety Problem scale, age 6–11 version (e.g., clings to adult or dependent; too fearful or anxious). We also included five additional items: self-conscious or easily embarrassed; shy or timid; fears he or she might think or do something bad; feels he or she has to be perfect; and feels others are out to get him or her, which have been used in self-report questionnaires (e.g., March et al., 1997; Spence, 1998) and/or by previous studies to measure anxiety symptoms in children (e.g., Bosquet & Egeland, 2006). The internal consistency of the anxiety symptoms scales (Cronbach’s alphas) were .59 and .64 at ages 2 and 3.5, respectively, for the early childhood version and were .65, .67, .63, .62, and .73 at ages 5, 5.5, 6, 8, and 10, respectively, for the school-age version. To ensure scores from different versions of the scale were comparable, the summary scores of anxiety symptoms at each age point were standardized.

Child shyness

Children’s shy temperament was assessed using the Shyness scale of the Toddler Behavior Checklist (TBC; Larzelere, Martin, & Amberson, 1989), which was administered to mothers at the 1.5-year assessment. The 4-point Shyness scale contains seven items that measure toddlers’ shyness and fearfulness. As the original 7-item scale had relatively low reliability (α = .56), three of the items were selected (acts shy or timid; acts afraid around strangers; and resists being left with other caretakers) to more narrowly focus the scale on shyness, for which the internal consistency was slightly higher (α = .60).

Child emotion regulation

At age 3.5, children completed a delay-of-gratification task, the cookie task (Marvin, 1977), in the laboratory, and the procedure was videotaped. During this task, children were required to wait for a cookie in a laboratory room, which was cleared out of all toys while their mothers completed questionnaires. After identifying children’s preference among a selection of cookie types, mothers were given a clear bag with the preferred kind of cookie in it. Mothers were instructed to keep the cookie within the children’s view but out of their reach for 3 min. Children’s emotion regulatory behavior was coded into five mutually exclusive strategies, based on a coding system adapted from the work of Grolnick et al. (1996) and by Gilliom and colleagues (see Gilliom et al., 2002, for details). The presence or absence of each of these five strategies was coded during each 10-s interval of the 3-min task. These strategies included: active distraction (purposefully shifting focus of attention away from the delay object to engage in other activities); passive waiting (standing or sitting quietly without looking at the cookie or engaging in any activities); focus on delay object or task (speaking about, looking at, or trying to retrieve the cookie or to end the waiting period); information gathering (asking questions aimed at learning more about the waiting situation); and physical comfort seeking (seeking physical contact with the mother such as touching or requesting to be held). In addition, the presence and intensity of anger were coded. Intercoder reliability (kappa) for all codes ranged from .64 to .79. To reduce the number of variables, a principal component analysis was performed on the five behavior variables and the duration of anger. Two factors emerged: passive/dependent, which included passive waiting, physical comfort seeking (with positive loadings), and active distraction (with negative loading); and negative focus on delay, which included high scores on both focus on delay and anger. The final scores for the factor passive/dependent were generated by subtracting the frequency of active distraction from the sum of passive waiting and physical comfort seeking; higher (and positive) scores represent more passive waiting and comfort seeking relative to active distraction, and negative scores represent more active distraction relative to passive waiting and physical comfort seeking. Similarly, the final scores for negative focus on delay were the sum of the frequency count for focus on delay and anger.

Insecure attachment

Attachment security was assessed when children were 18 months of age using the Strange Situation, a standardized procedure involving exposure of the infant to increasingly stressful 3-min episodes involving infant, mother, and a stranger (Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters, & Wall, 1978). Classification into one of four patterns of attachment (A = avoidant, B = secure, C = resistant, and D = disorganized) was based on infant exploratory behavior, orientation to the mother and stranger, and response to mother during two reunions that follow brief separations. Six graduate student raters, blind to other ratings of the mother and child, were trained to reliability by Joan Vondra, who received training and certification in the scoring of the Strange Situation by trainers at the University of Minnesota. Interrater agreement on major classifications ranged from 80% to 100%, with a mean of 83% for the test assessments, and averaged 77% with Daniel S. Shaw for a random set of study tapes. In cases of disagreement, a third rater was used. For the present study, a dichotomous variable, insecure attachment, was generated on the basis of the attachment classification (0 = B and 1 = A/C/D).

Maternal depression

When target children were at age 3.5, mothers were administered the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R Disorders (SCID; Spitzer, Williams, Gibbon, & First, 1990), a semistructured diagnostic interview that assesses current and lifetime psychiatric disorders. Because of the more limited focus of the original study, only the mood disorder modules (including major depression, dysthymia, and bipolar disorder) were administered to mothers, with the “lifetime” diagnosis restricted to the child’s first 3.5 years of life. Interviews were administered by advanced doctoral students in clinical psychology, with diagnoses established in consultation with Daniel S. Shaw, a licensed clinical psychologist with several years of experience in using the SCID. On the basis of the diagnoses made for these mothers, a dichotomous measure, maternal depression, was created to record the presence or absence of depressive disorders (major depression and/or dysthymia) between the child’s birth and age 3.5. Maternal self-report of depressive symptoms was also collected using the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; Beck, Steer, & Garbin, 1988). Among mothers with depressive disorders, 43.5% had BDI scores in the mild-to-moderate range (10–18), 16.1% reported moderate-to-severe (19–29) depressive symptoms, and 6.5% reported severe (30–63) symptoms at the age-1.5 assessment. At age 2, the percentages were 41.9%, 9.7%, and 3.2%; at age 3.5, 30.2%, 14.3%, and 4.8%, for mild–moderate, moderate–severe, and severe levels of symptoms, respectively.

Maternal negative control

At both ages 1.5 and 2, children and their mothers were observed in the laboratory during a clean-up task. Mothers were instructed to ask their children to put the toys in a basket, and mother–child dyads were allowed 5 min to complete the task. The clean-up task has been widely used in research on parenting behavior with young children. The videotaped clean-up tasks for mother–child dyads were coded using the Early Parenting Coding System (EPCS; Winslow & Shaw, 1995). A factor for maternal negative control was generated on the basis of two molecular codes and a global code reflecting the level of parents’ physical control and negative verbal expression. The molecular codes included: negative physical contact (physical control; forcing or restricting the child’s movement) and critical statement (verbal statement prohibiting the child from doing something or criticizing the child’s behavior, state of being, or character). For the molecular coding, the duration (in seconds) of each behavior was recorded. The global code of intrusiveness (unnecessary commands, physical manipulation or restriction of the child, or preventing child from attempting tasks by doing it for the child) was coded on a 4-point scale (1 = not at all intrusive; 4 = intrusive) and rated after coders viewed the entire clean-up task. Cohen’s kappa coefficients were .67 for negative physical contact, .75 for critical statement, and .70 for intrusiveness. The scores for each code were averaged across two age points (correlations of scores between ages 1.5 and 2 ranged from .33 to .47) and then standardized. The final measure of maternal negative control was the sum of the z scores of all components. This measure demonstrated adequate internal consistency, with an alpha of .70 for the averaged code scores.

Child Diagnoses of Anxiety and Depressive Disorders

At ages 10 and 11, boys and mothers were administered the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children-Epidemiological Version (K-SADS-E; Orvaschel & Puig-Antich, 1987) regarding children’s symptoms during the past year. The K-SADS-E is a semistructured psychiatric interview for obtaining diagnoses on the basis of DSM–IV criteria. The same examiner interviewed the mother and the child, with diagnoses made through consensus. To establish reliability, clinical interviewers participated in an intensive training program at the Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic. Additionally, every case in which a child approached or met diagnostic criteria was discussed at regularly held interviewing team meetings, which included all other interviewers and Daniel S. Shaw, who is a licensed clinical psychologist with 15 years of experience using the K-SADS. Diagnoses for anxiety and depressive disorders were decided on the basis of DSM–IV criteria, considering the severity of children’s symptoms and the level of clinical impairment. Children meeting diagnostic criterion at either the age-10 or age-11 assessment were considered to have a disorder for purposes of the present study.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed in three steps. First, trajectories of anxiety symptoms were modeled, and subgroups of children who followed distinct trajectories were identified, using a group-based semiparametric mixture modeling method (Jones, Nagin, & Roeder, 2001; Nagin, 1999). This method is particularly well suited for detecting population heterogeneity in the pattern of behavior over time. To specify the function that links the course of the behavior with age, a latent variable , designated as individual i’s potential for engaging in the behavior of interest at age t, is modeled using a polynomial function of age (Nagin, 2005). For the application in this study, the basic model includes up to cubic relationship between and age:

where are parameters that define the shape of the polynomial and εit is the disturbance. Seven assessments of anxiety symptoms between the ages of 2 and 10 were used for estimating the trajectories. In selecting the best fitting model—the model with the optimal number of groups—the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) statistic was used as a basis, in consideration with the substantive importance of the groups (Nagin, 2005). The modeling procedure also yields two sets of estimation: parameter estimates that describe the shape of the trajectories (i.e., parameters of stable, linear, quadratic shapes) and posterior probabilities of group membership for each individual—probabilities of each individual belonging to different trajectory groups. Each individual, then, is assigned to the trajectory group of which the posterior probability is the highest.

The second step involved testing associations between risk factors and group membership. After the optimal model was determined, the individual-level characteristics (e.g., child shyness) were introduced to the model as predictors of group membership. The effects of individual-level characteristics were estimated jointly with the trajectories in a multivariate model to test the extent to which a specific predictor affects the probability of group membership, controlling for other potential predictors. As a final step, trajectory group membership was used to predict children’s later internalizing disorders in logistic regression analyses.

Results

The descriptive statistics for all variables included in the analyses are presented in Table 1. Rates of maternal depression were relatively high, consistent with research suggesting higher prevalence of depression in low-income populations. Between the child’s birth and age 3.5, 24.6% of mothers were diagnosed with depressive disorders (including major depressive disorder [MDD] and dysthymia), 22.5% with MDD, and 5.9% with dysthymia (2.4% with both). Rates of child anxiety and depression were also somewhat high in the present sample, with about 10% of the boys diagnosed with depressive disorders and about 17% diagnosed with one or more anxiety disorders at ages 10 and/or 11 (i.e., at some time over a 2-year range).1

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics

| Variable | Child age (yrs.) | N | M | SD | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety symptoms | ||||||

| CBCL/2–3 | 2 | 285 | −0.02 | 0.98 | −1.92 | 3.44 |

| 3.5 | 279 | 0.00 | 0.99 | −2.01 | 2.88 | |

| CBCL/4–18 | 5 | 276 | 0.01 | 1.00 | −1.38 | 3.47 |

| 5.5 | 234 | 0.00 | 1.00 | −1.16 | 4.30 | |

| 6 | 262 | 0.00 | 1.00 | −1.29 | 2.95 | |

| 8 | 246 | 0.00 | 1.00 | −1.08 | 4.29 | |

| 10 | 227 | 0.00 | 1.00 | −0.96 | 3.44 | |

| Risk factors | ||||||

| Shyness | 1.5 | 283 | 4.16 | 2.10 | 0.00 | 9.00 |

| Passive/dependent | 3.5 | 247 | −4.29 | 10.81 | −18.00 | 35.00 |

| Negative focus on delay | 3.5 | 256 | 18.91 | 33.71 | 0.00 | 194.00 |

| Insecure attachment | 1.5 | 271 | 47.2% | — | — | — |

| Maternal depression | 3.5 | 252 | 24.6% | — | — | — |

| Maternal negative control | 1.5 & 2 | 285 | 0.06 | 2.30 | −2.91 | 13.24 |

| Diagnosis of internalizing disorders | ||||||

| Depressive disorders | 10–11 | 264 | 9.5% | — | — | — |

| Anxiety disorders | 10–11 | 263 | 16.7% | — | — | — |

Note. CBCL = Child Behavior Checklist. Dashes indicate data were not applicable.

Trajectory Analysis

As a first step, the number and the shape of developmental trajectories were identified. Five full cubic models with 3–6 groups were estimated. The BIC scores for the four- and five-group models were close (−2239.53 and −2237.87, respectively). Although in general the model (among a set of nested models with different numbers of groups) the largest BIC score is considered to fit the data the best (Nagin, 2005), for reasons of parsimony, the four-group solution was selected. To increase the precision of the model estimation, the initial four-group model was refined by deleting nonsignificant parameters, with the resulting BIC score improved to −2228.66. The posterior probabilities of group memberships were 94.3%, 77.4%, 88.7%, and 95.5% for the four groups, suggesting reasonably low classification errors.

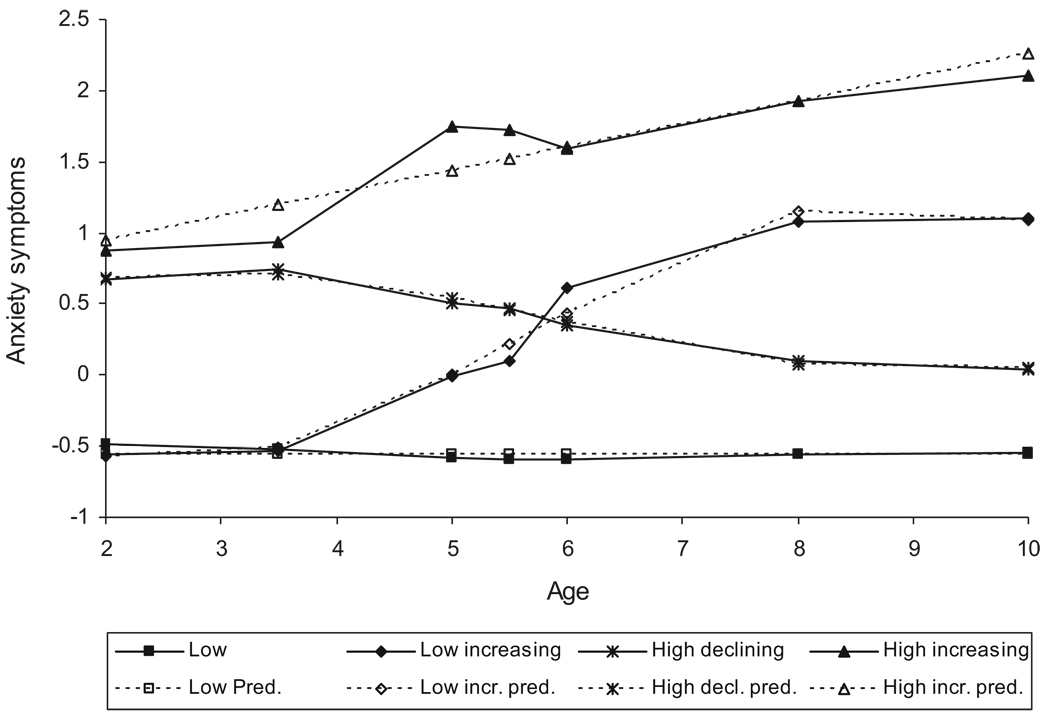

Figure 1 depicts the trajectories of the final four-group model. The largest group, the low group, accounted for 50.8% of the sample. Children in this group exhibited stable low levels of anxiety, approximately half of a standard deviation below the mean, intercept = −.55, SE = .03, t(1759)= −17.90, p < .0001. The second largest group, the high-declining group, consisted of 32.5% of boys. Boys in this group showed high levels of anxiety symptoms at age 2 but declined over the course of the study. By age 10, these children’s anxiety symptoms were at approximately the mean level of the sample. For this group, the slope was not linear, with most of the decline occurring between ages 3.5 and 8, intercept = .13, SE = .39, t(1759) = 0.33, p > .1; age slope = .46, SE = .27, t(1759) = 1.71, p = .09; age2 slope = −.11, SE = .05, t(1759) = −2.00, p < .05; age3 slope = .01, SE = .00, t(1759) = 1.96, p = .05. A third group, labeled the low-increasing group, was relatively low in anxiety symptoms at age 2. However, levels of anxiety increased steadily over time, also in a nonlinear fashion, with a rapid change occurring between ages 3.5 and 8, intercept = .53, SE = .84, t(1759) = 0.63, p > .1; age slope = −.99, SE = .56, t(1759) = −1.77, p = .08; age2 slope = .25, SE = .11, t(1759) = 2.32, p < .05; age3 slope=−.01, SE − .01, t(1759) = −2.41, p < .05. The low-increasing group consisted of a small percentage of children (8.8%), who, at the age of 10, were the second highest in anxiety symptoms—at approximately 1 standard deviation above the mean with approximately 1.5-standard deviation increments across the 8-year period. The smallest group, the high-increasing group, consisted of 7.9% of the sample. This group exhibited the most severe and persistent pattern of anxiety symptoms overall: Children started at a high level of anxiety, 3/4 standard deviations above the mean, and increased overtime, with an increment of approximately 1 standard deviation, intercept = .62, SE = .18, t(1759) = 3.56, p < .001; age slope = .16, SE = .03, t(1759) = 5.61, p < .0001. At age 10, this small group of children maintained an anxiety level at more than 2 standard deviations above the mean. As shown in Figure 1, at age 2, high-increasing and high-declining groups showed more anxiety symptoms than low and low-increasing groups, F(3, 266) = 56.02, p < .0001, and at age 10, all four groups were different from each other in levels of anxiety, F(3, 223) = 127.73, p < .0001.

Figure 1.

Trajectories of anxiety symptoms among boys from ages 2 to 10. Low group (50.8%); low-increasing group (8.8%); high-declining group (32.5%); and high-increasing group (7.9%). pred. = predicted.

Predicting Group Membership

In this stage of analysis, the basic trajectory group model was extended by introducing time-stable covariates, the risk factors, to examine whether and to what extent these individual-level characteristics were associated with trajectory group membership. Correlations among the predictors were uniformly modest with none above .21 (see Table 2). Table 3 contains the parameter estimates and the associated test statistics indicating the predictive power of the risk factors. All risk factors were measured before or at the beginning stage of the study and were introduced in the analysis simultaneously to predict trajectory group membership. The coefficient of each predictor indicates the direction and the strength of association between this particular risk factor and the trajectory group membership, accounting for all other predicators. Note that there were no parameter estimates for the low group, as this group was set as the reference group against which all other groups were compared.

Table 2.

Correlations of Risk Factors

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Shyness | — | |||||

| 2. Passive/dependent | .21** | — | ||||

| 3. Negative focus on delay | −.00 | .14* | — | |||

| 4. Insecure attachment | .04 | .12 | .01 | — | ||

| 5. Maternal depression | −.01 | −.13* | −.03 | .03 | — | |

| 6. Maternal negative control | −.08 | −.07 | .04 | .09 | .04 | — |

Note. Passive/dependent and negative focus on delay are factors derived from the emotion regulation task.

p < .05.

p < .01.

Table 3.

Association Between Risk Factors and Trajectory Group Membership in the Five-Group Model

| Variable | Coefficient | Error | t(1277) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low increasing vs. low | |||

| Shyness | −0.16 | .16 | −1.04 |

| Passive/dependent | −0.01 | .04 | −0.16 |

| Negative focus on delay | 0.02 | .01 | 2.01* |

| Insecure attachment | −1.18 | .76 | −1.55 |

| Maternal depression | 0.42 | .71 | 0.60 |

| Maternal negative control | 0.30 | .13 | 2.36* |

| High declining vs. low | |||

| Shyness | 0.25 | .11 | 2.30* |

| Passive/dependent | 0.06 | .02 | 2.86** |

| Negative focus on delay | −0.00 | .01 | −0.43 |

| Insecure attachment | −0.31 | .42 | −0.74 |

| Maternal depression | −0.45 | .57 | −0.78 |

| Maternal negative control | −0.02 | .11 | 0.19 |

| High increasing vs. low | |||

| Shyness | 0.65 | .20 | 3.34*** |

| Passive/dependent | −0.04 | .04 | −1.15 |

| Negative focus on delay | −0.01 | .02 | −0.57 |

| Insecure attachment | 0.87 | .61 | 1.43 |

| Maternal depression | 1.38 | .58 | 2.36* |

| Maternal negative control | 0.24 | .11 | 2.16* |

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

As shown in Table 3, children’s negative focus on delay and maternal negative control differentiated between low increasing and low trajectories. Specifically, among boys who started low with anxiety symptoms, those who exhibited anger and sustained focus on the source of frustration during the cookie task and those whose mothers were high in negative control were more likely to develop increased anxiety symptoms over time. Relative to the low group, the high-declining group was associated with higher levels of child shyness and more frequent use of passive/dependent emotion regulatory strategies. Child shyness, maternal depression, and maternal negative control together differentiated the high increasing from the low trajectory. Specifically, compared with those in the low group, children in the high-increasing group were more likely to be shy as toddlers and have mothers who were depressed and negatively controlling. Insecurity attachment was not associated with any trajectory groups.2

Predicting Internalizing Disorders With Trajectory Group Membership

In the final stage of the analysis, we addressed whether trajectory group membership was associated with children’s anxiety and depressive disorders between the ages of 9 and 11. A series of binomial and multinomial logistic regression models were estimated using trajectory group membership to predict later diagnoses of anxiety and depressive disorders. The model for anxiety disorders (whether or not children were diagnosed with any type of anxiety disorder) yielded an overall significant association (see Table 4). The parameter estimates indicated that, compared with the low group, children in the high-declining group were more than twice as likely and children in the high-increasing group were about five times as likely to be diagnosed with anxiety disorders. Among the three groups with elevated anxiety symptoms (i.e., the two increasing groups and the high-declining group), probabilities for anxiety disorder diagnosis were not different. The percentages of diagnosis of anxiety disorders were 10.6%, 16.0%, 22.7%, and 36.8% for low, low-increasing, high-declining, and high-increasing groups, respectively.

Table 4.

Associations of Group Membership With Anxiety Disorders, Depressive Disorders, and Co-Occurring Anxiety and Depressive Disorders

| Variable | Model χ2 | B | SE | Wald | Odds ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety disorders | 10.48* | ||||

| Low increasing (n = 25) | 0.47 | 0.61 | 0.59 | 1.61 | |

| High declining (n = 88) | 0.91 | 0.38 | 5.70* | 2.48 | |

| High increasing (n = 19) | 1.59 | 0.55 | 8.29** | 4.92 | |

| Depressive disorders | 11.79** | ||||

| Low increasing (n = 25) | 1.59 | 0.59 | 7.16* | 4.90 | |

| High declining (n = 88) | 0.13 | 0.56 | 0.05 | 1.13 | |

| High increasing (n = 19) | 1.71 | 0.64 | 7.24** | 5.54 | |

| Comorbid anxiety and depressive disorders | 8.18* | ||||

| Low increasing (n = 25) | 1.73 | 1.03 | 2.85 | 5.65 | |

| High declining (n = 88) | 0.41 | 1.01 | 0.17 | 1.51 | |

| High increasing (n = 19) | 2.50 | 0.95 | 6.92** | 12.19 | |

Note. The reference group is the low group (n = 132).

p < .05.

p < .01.

For depressive disorders, the binomial logistic regression model indicated a significant association between group membership and diagnoses: Boys in both low-increasing and high-increasing groups were more likely to develop depressive disorders than those in the low group, with a five-to sixfold increase in odds (see Table 4). Boys in these two groups were also more likely to be depressed than those in the high-declining group (B = 1.46, SE = .63, Wald = 5.37, p < .05; and B = 1.59, SE = .67, Wald = 5.58, p < .05, for low- and high-increasing group, respectively). The probabilities for diagnoses were not different between the two increasing groups. The percentages for diagnosis of depressive disorders were 6.1% and 6.8% for the low- and high-declining groups and 24.0% and 26.3% for the low- and high-increasing group, respectively.

Lastly, we tested the association between trajectory group membership and risk of co-occurring diagnosis of an anxiety and depressive disorder. As shown in Table 4, membership in the high-increasing group was highly predictive of co-occurring internalizing disorders—boys in the high-increasing group demonstrated a 12-fold increase in odds of a dual diagnosis compared with those in the low group. The rates of co-occurring anxiety and depressive disorders were 1.5%, 8.0%, 2.3%, and 15.8% for the low, low-increasing, high-declining, and high-increasing group, respectively. The rate for the high-increasing group was also higher than that of the high-declining group (B = 2.09, SE = .95, Wald = 4.80, p < .05).

Discussion

We identified trajectories of childhood anxiety symptoms and examined the association of trajectory groups with individual-level risk factors and later internalizing disorders in the present study. The results demonstrated notable differences in the developmental course of anxiety symptoms among a group of boys spanning from early to middle childhood. Similar to what we had hypothesized and consistent with previous research (e.g., Côté et al., 2002; Verhulst & van der Ende, 1992), a large portion of boys (51%) followed a stable low trajectory, and these boys tended not to develop later internalizing disorders. The remaining half of boys experienced elevated anxiety symptoms during part or all of the childhood, with the small proportion (17%) that followed increasing trajectories at particularly high risk for later internalizing disorders.

Risk Factors of Childhood Anxiety

We found both child and maternal attributes that were associated with varying trajectories and that seemed to contribute differently in predicting these trajectories. It is interesting that child factors and maternal factors seemed to influence anxiety symptoms at different points along the trajectory, with shyness predicting initially high levels of anxiety and maternal factors predicting increases in anxiety over time.

Consistent with previous research (e.g., Biederman et al., 1990; Kagan et al., 1999), children’s shy temperament was associated with elevated anxiety symptoms in early childhood, which, in turn, was associated with increased risk for preadolescent anxiety disorders. More importantly, shyness was associated with initially high levels of anxiety, regardless of whether these levels increased or decreased over time. This may reflect genetically determined biological influences on children’s anxiety, which may be moderated over time by environmental influences. These results add to a growing body of research that documents connections between specific temperamental characteristics in early childhood and sub-sequent anxiety problems.

However, the association between early shyness and anxiety symptoms in middle childhood was not strong (i.e., the high-declining and the low-increasing trajectories), which is consistent with studies suggesting that inhibited temperament is a stronger predictor of anxiety when inhibition and anxiety are assessed closer in time or when children are consistently inhibited (Bosquet & Egeland, 2006; Prior et al., 2000; Rapee, 2002). As temperament is thought to be moderated by environmental influence and to be only moderately stable over the course of childhood (Kagan, 1999), assessment of shy temperament at a single time point may not be predictive of anxiety symptoms several years later. The relatively weak association between shyness and anxiety in middle childhood may also be attributable to the anxiety measure used in the present study. Recent findings suggest that behavioral inhibition is primarily associated with risk for social anxiety (Gladstone et al., 2005; Hirshfeld et al., 2004), for which few items were included in the present study’s measure of anxiety during middle childhood.

In contrast, maternal factors were predictive of increasing trajectories of anxiety. Maternal negative control was positively associated with both the low-increasing trajectory and the high-increasing trajectory. Boys who were initially high in anxiety, and whose mothers were high in negative control, were likely to increase in levels of anxiety across childhood. However, even boys who were not initially anxious as toddlers were likely to develop anxiety symptoms in middle childhood if their mothers were initially high in negative control. Results of this study lend support to the link between parental overcontrol and elevated level of anxiety suggested by previous studies, which have been primarily cross-sectional (e.g., Hudson & Rapee, 2001; Ollendick et al., 2004). Parental negative control likely leads to increases in children’s anxiety by decreasing their sense of mastery over their environment and self-efficacy in coping with stressful and emotional situations (Chorpita & Barlow, 1998; Wood et al., 2003).

Maternal depressive disorders during the first 3.5 years of the child’s life were found to predict membership in the high-increasing anxiety group. This finding is in accord with previous research linking maternal depression to child anxiety disorders (Rosenbaum et al., 2000; Weissman et al., 2005; Wickramaratne & Weissman, 1998). Possible causal mechanisms between maternal depression and child psychopathology include genetic transmission, exposure to negative maternal cognition and impaired parenting behavior, and exposure to stressful life events (Goodman & Gotlib, 1999). The effects of maternal depression may accumulate over time, resulting in increasing levels of children’s anxiety across childhood. Although we did not have data on chronicity of mothers’ depressive disorders, maternal self-report on depressive symptoms indicated that 50%–66% of mothers with depressive disorders reported at least mild to moderate levels of depressive symptoms across the first 3.5 years of the child’s life.

Children’s emotion regulation strategies were also related to trajectory membership, particularly to changes in symptoms across time. Children who tended to sustain focused attention on the source of frustration during emotion-eliciting tasks were more likely to belong to the low-increasing group. This is consistent with findings that attentional focus on negative or threatening stimuli is associated with anxiety in children (Dalgleish et al., 2003; Taghavi, Dalgleish, Moradi, Neshat-Doost, & Yule, 2003; Vasey, Daleiden, Williams, & Brown, 1995). Findings are also consistent with links between rumination and involuntary control coping and internalizing among older children and adolescents (Connor-Smith et al., 2000; Nolen-Hoeksema, 1994; Silk et al., 2003). This risk factor does not have a strong influence on anxiety in early childhood, but it is associated with increasing anxiety symptoms in middle childhood, perhaps reflecting the increasing importance of cognitive control processes as children become older.

Contrary to our predictions, higher use of passive/dependent emotion regulatory strategies was associated with the high-declining group. Although children in this group had increased risk for preadolescent anxiety disorders, their anxiety symptoms declined over the course of childhood. This raises the possibility that these strategies may represent effective ways of regulating emotion for these children. The passive/dependent emotion regulation factor consisted of two strategies: (a) passive waiting and (b) physical comfort seeking. Although active strategies are generally thought to be more effective in regulating emotion than passive strategies (Silk et al., 2003), children engaged in passive waiting may have been better at tolerating anxiety and negative emotion. These children could also have been engaged in unobservable cognitive strategies for managing emotion. Furthermore, given the young age of the children at the time of the assessment, seeking physical comfort from the mother may have been an effective strategy for regulating negative emotion. In future research, it would be valuable to examine changes in emotion regulation strategies across time, as they are associated with children’s anxiety.

We did not uncover a direct association between insecure attachment during infancy and trajectories of anxiety symptoms. Similarly, Bosquet and Egeland (2006) did not find a direct effect of infant attachment insecurity on later anxiety symptoms; instead, they found indirect relations between the two accounted for by childhood emotion regulation and the quality of peer relations. Greenberg (1999) has pointed out that attachment, as a risk/protective factor, tends to show the greatest influence in the context of other risk factors within the family ecology. Attachment security may contribute to later disorder by moderating the effects of other risk factors, or the effect of attachment may be moderated by other risk factors.

Trajectory Membership and Preadolescent Depressive and Anxiety Disorders

Children’s anxiety trajectory membership was associated with the development of both depressive and anxiety disorders in preadolescence. Children in the initially high trajectories were particularly likely to develop anxiety disorders, and children in the increasing trajectories were particularly likely to develop depressive disorders. Children in the high-declining trajectory were two times more likely to develop an anxiety disorder in preadolescence than children in the low trajectory, and children in the high-increasing trajectory were five times more likely to develop an anxiety disorder than children in the low trajectory. These findings suggest that initially high levels of anxiety place children at risk for a future anxiety disorder, but this risk is even stronger if anxiety symptoms increase across childhood.

Children in the high-increasing and low-increasing trajectories were more likely to develop depression than children in the low-and high-declining trajectory groups. This finding could have implications for understanding the pathway from anxiety to depression. It suggests that anxiety is only associated with future depression when it increases across middle childhood. Anxiety in early childhood alone (i.e., the high-declining group) was not associated with later depression. In contrast, children who developed anxiety during the school-age years were more likely to become depressed, even if they had low levels of anxiety in early childhood. The mechanisms for this finding are not clear; however, it may be that increases in anxiety across childhood are indicative of stressful life events and chaotic or negative family environments, which are also associated with risk for depression in childhood and adolescence (Sheeber, Hyman, & Davis, 2001). Indeed, both high- and low-increasing trajectories were associated with maternal risk factors, namely, maternal depression and maternal negative control.

Children in the high-increasing anxiety group experienced the most severe internalizing problems as they transitioned to adolescence. These children were more likely to develop anxiety disorders, depressive disorders, and comorbid anxiety and depressive disorders compared with children in the low trajectory. The high-increasing trajectory is associated with both temperamental (shyness) and familial risk factors (maternal depression, maternal negative control); therefore, it is not surprising that this group would experience the greatest adjustment difficulties during preadolescence.

Limitations

Several methodological limitations should be considered in the interpretation of these results. The original study from which participants were drawn was designed to investigate the precursors of childhood externalizing problems, and thus recruited only boys from low-income families living in an urban setting. Previous research on the prevalence rate of anxiety disorders in boys and girls has yielded mixed findings (Costello et al., 2003). Additionally, although gender differences in predictors of anxiety symptoms have not been identified (Kovacs & Devlin, 1998), boys and girls may follow divergent pathways in the development of anxiety due to differential socialization processes, and thus the trajectories of anxiety and the associations with risk factors identified in the present study may be unique to boys. Furthermore, the focus on low-income boys may not generalize to a lower risk sample or children living in rural or suburban settings but addresses an underserved population at high risk for mental health problems. Nevertheless, future research clearly needs to be conducted on boys and girls from diverse socioeconomic strata and communities to corroborate the present findings.

Related to the study’s initial focus on antecedents of externalizing problems, several potentially significant risk factors associated with childhood anxiety were not examined in the present study, including neurobiological factors (Gunnar, 2001), stressful life events (Ingram & Price, 2001), cognitive biases (Vasey & MacLeod, 2001), and social competence and peer relations (Bosquet & Egeland, 2006). Additionally, although data were available on maternal depressive disorders, we were not able to obtain information about maternal history of anxiety disorders. Although many studies have indicated that both parental depression and anxiety are strongly associated with children’s risk for anxiety disorders (e.g., Beidel & Turner, 1997; Wickramaratne & Weissman, 1998), one recent study (Biederman et al., 2006) suggests that the parental depression–offspring anxiety association is largely accounted for by the comorbidity of parental depression and anxiety disorders. It is therefore important that both parental anxiety and depressive disorders be included in future research. Also related to maternal psychopathology, we only had diagnosis of depressive disorders between child’s birth and age 3.5. We did not have data on the chronicity of disorders (although mothers’ self-report of depressive symptoms indicate moderate stability) or whether depressive disorders were present only during the postpartum period, all of which are important in understanding the influence of maternal depression on child anxiety. Finally, the goal of the present study was to predict internalizing disorders using trajectories of anxiety symptoms; thus, the age of onset of anxiety and depressive disorders was not assessed. Nevertheless, it is possible that the early onset of anxiety and depressive disorders may exacerbate anxiety symptoms. Future study should examine the relationship between anxiety symptoms and disorders in both directions.

Our longitudinal measure, anxiety-related behavior, demonstrated reasonable internal consistency with alphas ranging from .59 to .73, although not optimal. The reliability of parental report of anxiety symptoms for young children tends to be relatively low (e.g., Asbury, Dunn, Pike, & Plomin, 2003). Nonetheless, measurement error may affect the results of the analyses. In general, measurement error would attenuate the association between variables that are unreliably measured and, in the case of trajectory analysis, would prevent it from deriving clearly distinct groups. However, despite the nonoptimal reliability of the anxiety measure, we were able to identify trajectory groups with adequate posterior probabilities and found associations between risk factors and trajectories that were consistent with theory and previous research.

Some of the risk factors, including child shyness and maternal depressive disorders, were at least partially based on maternal report. The link between shyness and anxiety as well as that between maternal depression and child anxiety are likely to be confounded due to informant bias (Fergusson & Horwood, 1993). As such, part of the variation in the ratings of anxiety symptoms and shyness might be due to differences in maternal characteristics (e.g., maternal depression). Future studies should strive to minimize the shared method variance between risk factors and the longitudinal anxiety measure. In addition, as noted earlier, the measure of shyness included only three items. Although the scale was intentionally reduced in size to ensure that it was specifically tapping children’s inhibition in social situations, the scale’s internal consistency was only marginally adequate. It is also important to note that the shyness measure overlapped to a certain extent with the anxiety measures, more so with the younger version, as the scale for younger children consisted of more items for separation and social anxiety than that of older children, and this may have inflated the association between shyness and early anxiety symptoms. Our assessment of child shyness could have been supplemented with observations and/or reports by an alternative caregiver (e.g., fathers). Finally, diagnoses of maternal and child disorders were achieved using a consensus process and did not include reliability data for individual examiners. Although no diagnosis was made without the consultation of an experienced diagnostician, the study would have benefited from having reliability on individual examiners.

Conclusions and Clinical Implications

The present study documented the patterns of stability and change in the development of anxiety symptoms starting at age 2, a developmental period for which little longitudinal data are available. Findings of this study suggest both continuity and discontinuity in anxiety symptoms from early to middle childhood. Although some children with early starting anxiety symptoms showed substantial reductions by school age, others with little symptomatology in early childhood began to develop higher rates of anxious behavior during middle childhood. Future research is clearly needed to corroborate the patterns found in this study and, if corroborated, to investigate factors that contribute to the continuity and discontinuity of anxiety symptoms and more serious impairment. The findings also highlight the advantages of using a person-oriented approach, which enabled us to identify a few distinct trajectories representing small groups of children who deviated from the norm. Perhaps the most important finding in this study was that there are multiple pathways through which children develop anxiety symptoms and that each of these pathways is likely to be associated with unique child and environmental factors and lead to specific maladaptive outcomes.

Findings raise the hypothesis that temperamental factors are strongly related to early anxiety levels, but familial factors, such as parenting and maternal depression, are more important for anxiety and subsequent depression that emerges later in time. More importantly, it appears that controlling parenting is associated with anxiety in middle to late childhood, even among children who were not initially anxious. These findings could imply that interventions carried out in early childhood aimed at reducing controlling parenting might be one effective approach for decreasing children’s later risk of anxiety disorders. This is consistent with preliminary evidence from several parenting interventions that focus on decreasing parental overcontrol (Kagan, Snidman, Arcus, & Reznick, 1994; LaFreniere & Capuano, 1997). Findings point to obtaining treatment for parental depressive disorders as another potential approach for reducing children’s likelihood of experiencing increasing anxiety symptoms across childhood. Finally, findings support the use of interventions aimed at teaching high-risk children to acquire coping and emotion regulation skills, including attentional and cognitive control skills, and to practice these skills in feared situations (e.g., Barrett & Turner, 2001). Findings also provide information about the additive risk of child and familial factors in increasing the probability of developing depression, anxiety, and comorbid depression and anxiety. If replicated, then they could have implications for developing targeted preventions for children at risk for internalizing disorders.

Acknowledgments

The research reported in this article was supported by National Institute of Mental Health Grants MH 50907 and MH 01666 awarded to Daniel S. Shaw. We are grateful to the work of the staff of the Pitt Mother & Child Project for their years of service and to the families who participated in the study for making the research possible. We also thank Daniel Nagin and Bobby Jones for their assistance on this article.

Footnotes

Point prevalence rates for child depression have been reported to range between 1% and 6% (McGee & Williams, 1988) to 6% (Kessler & Walters, 1998). Estimates of lifetime rates vary widely, ranging from 4% (Whitaker et al., 1990) to 25% (Lewinsohn, Rohde, & Seeley, 1998), and typically focus on adolescents; however, the nationally representative National Co-morbidity Survey (Kessler et al., 1994) estimated the lifetime prevalence rate of major depressive disorder to be 14%. For anxiety disorders, Costello, Egger, and Angold (2005) reviewed the epidemiological literature and reported that 12-month estimates of any anxiety disorder in school-age children and adolescents ranged from 8.6% to 21%. Furthermore, few studies have systematically examined rates of preadolescent anxiety or depression in high-risk communities. Our rates, which are within the high range of previous epidemiological findings, are likely reflective of two factors: (a) the fact that the reporting period included a 2-year duration and (b) the high-risk nature of the sample.

Analyses using subtypes of insecure attachment categories as risk factors also resulted in nonsignificant associations with trajectories of anxiety symptoms.

Contributor Information

Xin Feng, Department of Psychology, University of Pittsburgh.

Daniel S. Shaw, Department of Psychology, University of Pittsburgh

Jennifer S. Silk, Department of Psychiatry, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine.

References

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist/4–18 and 1991 profile. Burlington: University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist/2–3 and 1992 profile. Burlington: University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Manual for ASEBA preschool forms ans profiles. Burlington: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Manual for the ASEBA school-age forms and profiles. Burlington: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, &l Families; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth MDS, Blehar MC, Waters E, Wall S. Patterns of attachment: A psychological study of the Strange Situation. Potomac, MD: Erlbaum; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Albano AM, Krain A. Anxiety and anxiety disorders in girls. In: Bell DJ, Foster SL, Mash EJ, editors. Handbook of behavioral and emotional problems in girls. New York: Plenum Publishers; 2005. pp. 79–116. [Google Scholar]

- Asbury K, Dunn JF, Pike AP, Plomin R. Nonshared environmental influences on individual differences in early behavioral development: A monozygotic twin differences study. Child Development. 2003;74:933–943. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett PM, Turner C. Prevention of anxiety symptoms in primary school children: Preliminary results from a universal school-based trial. British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2001;40:399–410. doi: 10.1348/014466501163887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Garbin MG. Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory: Twenty-five years of evaluation. Clinical Psychology Review. 1988;8:77–100. [Google Scholar]

- Beidel DC, Turner SM. At risk for anxiety: I. Psychopathology in the offspring of anxious parents. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36:918–924. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199707000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell RQ. Age-specific manifestations in changing psychosocial risk. In: Farran DC, McKinney JD, editors. The concept of risk in intellectual and psychosocial development. New York: Academic Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Biederman J, Hirshfeld-Becker DR, Rosenbaum JF, Friedman D, Snidman N, Kagan J, et al. Further evidence of association between behavioral inhibition and social anxiety in children. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;158:1673–1679. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.10.1673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biederman J, Petty C, Hirashfeld-Becker DR, Henin A, Faraone SV, Dang D, et al. A controlled longitudinal 5-year follow-up study of children at high and low risk for panic disorder and major depression. Psychological Medicine. 2006;36:1141–1152. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706007781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biederman J, Rosenbaum JF, Bolduc-Murphy EA, Faraone SV, Chaloff J, Hirshfeld DR, et al. A 3-year follow-up of children with and without behavioral inhibition. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1993;32:814–821. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199307000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biederman J, Rosenbaum JF, Hirshfeld DR, Faraone SV, Bolduc EA, Gersten M, et al. Psychiatric correlates of behavioral inhibition in young children of parents with and without psychiatric disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1990;47:21–26. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1990.01810130023004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosquet M, Egeland B. The development and maintenance of anxiety symptoms from infancy through adolescence in a longitudinal sample. Development and Psychopathology. 2006;18:517–550. doi: 10.1017/S0954579406060275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Attachment and loss: Vol. II. Separation. New York: Basic Books; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley SJ. Affect regulation and the development of psychopathology. New York: Guilford Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Brent DA, Baugher M, Bridge J, Chen T, Chiappetta L. Age- and sex-related risk factors for adolescent suicide. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1999;38:1497–1505. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199912000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breznitz Z, Friedman SL. Toddler’s concentration: Does maternal depression make a difference? Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1988;29:267–279. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1988.tb00715.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buss KA, Goldsmith HH. Fear and anger regulation in infancy: Effects on the temporal dynamics of affective expression. Child Development. 1998;69:359–374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calkins SD, Johnson MC. Toddler regulation of distress to frustrating events: Temperamental and maternal correlates. Infant Behavior & Development. 1998;21:379–395. [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy J, Berlin LJ. The insecure/ambivalent pattern of attachment: Theory and research. Child Development. 1994;65:971–991. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chorpita BF, Barlow DH. The development of anxiety: The role of control in the early environment. Psychological Bulletin. 1998;124:3–21. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.124.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Cohen DJ. Perspectives on developmental psychopathology. In: Cicchetti D, Cohen DJ, editors. Developmental psychopathology: Vol. 1. Theory and methods. New York: Wiley; 1995. pp. 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- Cole DA, Peeke LG, Martin JM, Truglio R, Seroczynski AD. A longitudinal look at the relation between depression and anxiety in children and adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66:451–460. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.3.451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]