Abstract

The proton-coupled folate transporter (PCFT) SLC46A1 mediates uphill folate transport into enterocytes in proximal small intestine coupled to the inwardly directed proton gradient. Hereditary folate malabsorption is due to loss-of-function mutations in the PCFT gene. This study addresses the functional role of conserved charged amino acid residues within PCFT transmembrane domains with a detailed analysis of the PCFT E185 residue. D156A-, E185A-, E232A-, R148A-, and R376A-PCFT mutants lost function at pH 5.5, as assessed by transient transfection in folate transport-deficient HeLa cells. At pH 7.4, function was preserved only for E185A-PCFT. Loss of function for E185A-PCFT at pH 5.5 was due to an eightfold decrease in the [3H]methotrexate (MTX) influx Vmax; the MTX influx Kt was identical to that of wild-type (WT)-PCFT (1.5 μM). Consistent with the intrinsic functionality of E185A-PCFT, [3H]MTX influx at pH 5.5 or 7.4 was trans-stimulated in cells preloaded with nonlabeled MTX or 5-formyltetrahydrofolate. Replacement of E185 with Leu, Cys, His, or Gln resulted in a phenotype similar to E185A-PCFT. However, there was greater preservation of activity (∼38% of WT) for the similarly charged E185D-PCFT at pH 5.5. All E185 substitution mutants were biotin accessible at the plasma membrane at a level comparable to WT-PCFT. These observations suggest that the E185 residue plays an important role in the coupled flows of protons and folate mediated by PCFT. Coupling appears to have a profound effect on the maximum rate of transport, consistent with augmentation of a rate-limiting step in the PCFT transport cycle.

Keywords: heme carrier protein-1, proton-coupled folate transporter/heme carrier protein-1, folate transport, hereditary folate malabsorption, methotrexate, pemetrexed, proton-coupled transporters

folates (vitamin B9 family) are hydrophilic molecules required for de novo purine nucleotide and thymidylate synthesis and for vitamin B12-dependent methionine synthesis, from which S-adenosylmethionine is formed and utilized in the methylation of DNA, histones, and lipids (40, 41). Mammalian cells do not have the enzymatic machinery to synthesize folates and, therefore, are dependent on a variety of transport mechanisms for the intestinal absorption of folates and their delivery to systemic tissues. Three distinct genes encode for folate transporters. The reduced folate carrier (RFC-SLC19A11 ) is the major mechanism of folate transport into systemic tissues at physiological pH (23, 51). Folate receptors, FR-α and FR-β, also contribute to folate delivery; in particular, FR-α is highly expressed at the plasma membrane of some cells involved in vectorial folate transport (i.e., kidney, choroid plexus, and placenta) (16). The proton-coupled folate transporter (PCFT-SLC46A1), the most recent of these transporters to be cloned, mediates intestinal folate absorption and folate transport into the central nervous system (30, 51). This laboratory established that loss-of-function mutations in the PCFT gene result in an autosomal recessive disorder, hereditary folate malabsorption [HFM; Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man no. 229050], characterized by severe systemic folate deficiency and marked deficiency of folate within the cerebrospinal fluid (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bookshelf/br.fcgi?book=gene&part=folate-mal) (30, 52). PCFT augments FR-α-mediated endocytosis by facilitating the export of folates from acidified endosomes, a phenomenon also observed for the iron transporter divalent metal transporter 1 (DMT1) (2, 43, 53). PCFT also contributes to the pharmacological activity of the new-generation antifolate, pemetrexed, for which it has very high affinity, by serving as an alternative route of transport that sustains drug activity when RFC function is impaired (54). PCFT may have particular importance as a route for antifolate delivery within the acidic milieu of solid tumors (11, 44, 50).

PCFT utilizes the inwardly directed proton gradient to drive uphill transport of folates, as do a variety of other human intestinal proton-coupled solute carriers (43). Transport mediated by PCFT is electrogenic, and carrier affinity for its substrates and carrier translocation rates increase as pH is decreased (30, 31, 45). The present study addresses the role of conserved charged amino acids, located within the predicted 12 α-helical PCFT transmembrane domains (TMDs), in PCFT function. Charged residues tend to be excluded from TMDs because of unfavorable energy constraints within the lipophilic membrane (47). Hence, when located within this region, these amino acids usually contribute, by intramolecular interactions, to the stabilization of transporter tertiary structure (55). Functionally important charged residues [i.e., residues involved in substrate/cosubstrate (ion) binding, conformational state transitions, and coupling of substrate/cosubstrate translocation] undergo few mutations during evolution (19, 20). Fully conserved Arg (24, 32), Lys (8), Asp (17), and Glu (9) residues located within TMDs are functionally important in other human proton-coupled transporters. In this study, the D156-, E185-, E232-, R148-, and R376-PCFT residues are shown to be required for PCFT function. Studies focus on Glu185, which, as suggested by our data, plays an important role in the coupled transport of protons and folates mediated by PCFT.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals.

Tritiated methotrexate {MTX-disodium salt, 3′,5′,7-[3H](N); Moravek Biochemicals, Brea, CA} was purified by liquid chromatography and maintained as previously described (49). Unlabeled MTX was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO), (6S)5-formyltetrahydrofolate (5-formylTHF) from Schircks Laboratories (Jona, Switzerland). EZ-Link Sulfo-NHS-LC-Biotin [sulfosuccinimidyl-6-(biotinamido) hexanoate; catalog no. 21335] from Pierce Biotechnology (Rockford, IL), streptavidin-agarose beads (catalog no. 20349) from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA), and protease inhibitor cocktail (catalog no. 11836170001) from Roche Applied Science (Mannheim, Germany). All other reagents were of the highest purity available from commercial sources.

Cell lines, cell culture conditions, and transient transfection.

HeLa cells, originally obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA), were maintained in this laboratory in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2. The HeLa-R1-11 cell line (54) lacks PCFT and RFC expression, the latter because of a genomic deletion (50). Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) was used according to the manufacturer's protocol for transient transfection of plasmid DNAs into these cells. R1-11 or HeLa cells were transfected with empty pcDNA3.1(+) vector (mock) or the same vector containing wild-type (WT) or mutant PCFT cDNAs.

Site-directed mutagenesis and epitope tagging.

Site-directed mutagenesis was carried out according to the QuikChange II XL protocol (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). WT-PCFT cDNA, cloned into the BamH I site of the mammalian expression vector pcDNA3.1(+), was used as the template (30). Briefly, complementary forward and reverse primers, which carry the targeted nucleotide changes in the midregion, were designed individually to introduce the desired mutations into the human PCFT primary sequence at the indicated positions (see Supplemental Table 1 in the online version of this article). Initial DNA denaturation, number of plasmid amplification cycles, and annealing and extension conditions were as previously defined (46). The restriction enzyme Dpn I (10 U/μl) was used to digest the parental double-stranded DNA. The mixture (3 μl) was transformed into DH5α-competent cells (Invitrogen). Plasmids carrying the desired mutations were identified by DNA automated sequencing in the Albert Einstein Cancer Center Genomics Shared Resource. The entire coding region of PCFT was sequenced to confirm the mutations and the fidelity of DNA. A hemagglutinin (HA) peptide epitope (YPYDVPDYA) was fused to the carboxy terminus of WT-PCFT by PCR-based site-directed mutagenesis, as previously described (46). The C-HA-PCFT vector was used as a template for amino acid substitutions at E185. (Forward primers used to introduce these mutations are shown in Supplemental Table 1.)

Membrane transport analysis and trans-stimulation conditions.

A technique for rapid measurement of [3H]MTX influx was utilized for determination of initial uptake rates (37). R1-11 cells (4 × 105 cells/ml) were seeded in 17-mm liquid scintillation vials and grown for 48 h before transient transfection of the different PCFT constructs. After 48 h, when cells were at mid-log-phase growth, the medium was aspirated, 1 ml of HBS buffer [20 mM HEPES, 140 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, and 5 mM dextrose (pH 7.4)] was added, and the vials were placed in a 37°C water bath for 20 min. Buffer was then aspirated, and uptake buffer containing [3H]MTX was added. The MBS uptake buffer (20 mM MES, 140 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, and 5 mM dextrose) was used for pH <7.0. An HBS uptake buffer was used for pH ≥7.0. In both cases, the desired pH was obtained by titration with 1 N HCl or 6 N NaOH. [3H]MTX uptake was halted after 1 min by addition of 10 volumes of ice-cold HBS buffer at pH 7.4; over this interval, uptake was unidirectional. Cells were washed twice with 0°C buffer, and then intracellular radioactivity and protein in each vial were determined (46). Nonspecific [3H]MTX associated with cells, as assessed by uptake measured in the mock-tranfected cells, was subtracted from total uptake for rate determinations. Influx is expressed as picomoles of [3H]MTX per milligram of protein per minute. [3H]MTX influx kinetic parameters (Kt and Vmax) were obtained from a nonlinear regression of influx as a function of extracellular antifolate concentration according to the Michaelis-Menten equation.

For assessment of trans-stimulation of [3H]MTX influx, vials containing a monolayer of R1-11 cells were divided into two groups. One group was incubated with 200 μM nonlabeled MTX (homoexchange) or 5-formylTHF (heteroexchange) in the HBS buffer at pH 7.4 and 37°C. These cells are identified as the “preloaded” cells. The other (control) group was incubated with HBS (pH 7.4) alone. After 20 min, the preloaded and control cells were washed twice with ice-cold HBS incubation buffer (pH 7.4) to remove the extracellular folate. Uptake buffer at 37°C containing [3H]MTX was added, and influx was assessed over 1 min, as described above.

Western blot analysis.

The HeLa cell membrane fractions were obtained 48 h after transient transfection with mock, COOH-terminal HA-tagged WT-PCFT (C-HA-WT-PCFT), or COOH-terminal HA-tagged mutant cDNAs. Initial cell burst was achieved by exposure to hypotonic buffer [0.5 mM Na2HPO4 and 0.1 mM EDTA (pH 7.4)] containing protease inhibitor for 30 min. After centrifugation at 14,000 rpm for 2 min, the pellet lipids were eluted in buffer solution containing 20 mM Tris base, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% SDS, and 1 mM EDTA. After the second centrifugation, proteins in the supernatant were dissolved in SDS-PAGE loading buffer [0.225 M Tris-Cl (pH 6.8), 50% glycerol, 5% SDS, and 0.05% bromphenol blue] with 0.25 M DTT. The proteins were resolved on 12% SDS-polyacrylamide gel and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride transfer membranes (Amersham Life Science). The primary antibody was a rabbit anti-HA antibody (catalog no. H6908, Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Protein loading was assessed using a rabbit anti-β-actin antibody (catalog no. 4967L, Cell Signaling Technology). Anti-rabbit IgG-horseradish peroxidase conjugate (lot no. 7074, Cell Signaling Technology; 1:5,000 dilution) was used as the secondary antibody.

Cell surface biotinylation and pull-down assay.

Confluent HeLa-R1-11 cells were transiently transfected with empty vector (mock), COOH-terminal HA-tagged WT-PCFT, or E185-PCFT substitution mutant constructs (E185A, E185L, E185C, E185D, E185H, or E185Q), in equal amounts, in six-well culture plates. After 2 days, cells were washed three times with PBS (pH 7.4) and then treated with 1 mg/ml EZ-Link Sulfo-NHS-LC-Biotin in PBS (pH 8.0) at room temperature for 30 min. After removal of the reagent and two washes with PBS (pH 7.4), cells were treated with 0.7 ml of hypotonic buffer [0.5 mM Na2HPO4 and 0.1 mM EDTA (pH 7.0)] containing protease inhibitor on ice for 30 min. Then the cells were scraped from the plates, and the membrane fraction was pelleted by centrifugation at 14,000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C. The pellet was resuspended in 400 μl of lysis buffer [50 mM Tris base, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, and 0.5% sodium deoxycholate (pH 7.4)] for 1 h at 4°C before centrifugation again at 14,000 rpm for 15 min at 4°C. After 25 μl of supernatant were obtained for Western blot analysis of the crude membrane protein fraction, the remaining supernatant was applied to lysis buffer-washed streptavidin-agarose beads (50 μl) in microcentrifuge tubes and rotated overnight at 4°C. On the following day, after centrifugation for 30 s at 13,000 rpm, the supernatant was aspirated, and the streptavidin-agarose beads were washed four times, each for 20 min, with 0.5 ml of lysis buffer. At the final step, the streptavidin-agarose bead-bound proteins were eluted by heating for 5 min at 95°C in 2× SDS-PAGE loading buffer with DTT and then subjected to Western blot analysis, as described above.

Statistical analyses.

Values are means ± SE from at least three independent experiments. Statistical comparisons were performed by two-tailed Student's paired t-test. Some experiments were assessed using repeated-measures ANOVA and Tukey's post test. All statistical analyses utilized GraphPad PRISM (version 3.0 for Windows).

RESULTS

Localization and evolutionary conservation of PCFT charged amino acid residues in predicted TMDs.

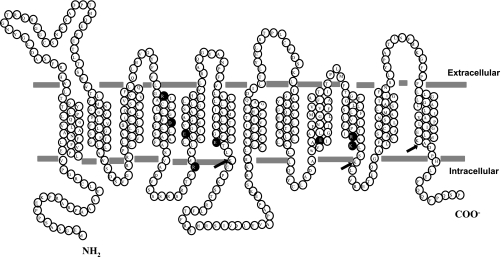

The human PCFT protein (SLC46A1, GenBank accession no. NP_542400) consists of 459 amino acids with 65 charged residues in the primary sequence. Twenty-three of these residues are identical among species; of these, only 8 are located within the 12 predicted TMDs (Fig. 1). These eight residues (D156, E185, E232, E336, R148, R180, R376, and K378), in addition to three partially conserved (≥3 species analyzed) lysine residues (K381, K235, and K445) that were predicted to be located on the TMD or at the membrane-cytoplasm interface, were included in this study. (The interspecies conservation status of these residues is shown in Supplemental Table 2.)

Fig. 1.

Membrane topology model for the human proton-coupled folate transporter (PCFT) predicted by programs available online (http://www.expasy.org/tools/#topology) indicating locations of fully (•) or partially (arrows) conserved charged residues located on transmembrane domains (TMDs) or membrane-aqueous interfaces.

Impact of amino acid substitutions in PCFT TMDs on transport function at acidic pH.

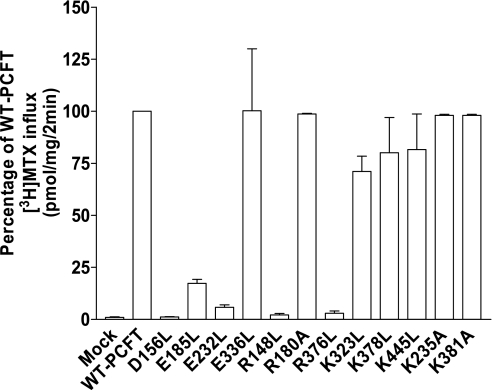

Seven charged residues within TMDs (D156, E185, E232, E336, R148, R376, and K378) were individually replaced with Leu, and two (R180 and K381) were replaced with Ala. The mutant PCFT cDNA constructs, along with WT-PCFT and the empty vector (mock), were transiently transfected into RFC-null, PCFT-null HeLa-R1-11 cells. As indicated in Fig. 2, influx of 0.5 μM [3H]MTX over 1 min at pH 5.5 into cells transiently transfected with the E336L, R180A, K378L, K445L, K235A, and K381A mutants was not significantly different from that into cells transfected with WT-PCFT. There was only a minimal reduction in transport for the K323L mutant (P = 0.08). However, a substantial loss of transport activity was mediated by the D156L, E185L, E232L, R148L, and R376L mutants, suggesting that these residues are required for intrinsic PCFT function and/or the mutations result in a defect in trafficking to the cell membrane.

Fig. 2.

Determination of methotrexate (MTX) influx in R1-11 cells transiently transfected with mock, wild-type (WT)-PCFT and mutant constructs in which predicted TMD charged residues were substituted with Leu (D156, E185, E232, E336, R148, R376, K378, and K445) or Ala (R180, K381, and K235). Influx of [3H]MTX (0.5 μM) was assessed at pH 5.5 at 37°C over 1 min. Values are means ± SE from 3 independent experiments. Transport activity in WT-PCFT transfected cells was 75.7 ± 4.6 pmol·mg protein−1·min−1.

Effect of extracellular pH on influx mediated by loss-of-function PCFT mutants.

To circumvent any possible negative side chain size-related effects due to Leu substitutions, all residues that resulted in loss of function (D156, E185, E232, R148, and R376) were individually replaced with Ala and transiently transfected into HeLa-R1-11 cells. Influx of 0.5 μM [3H]MTX was assessed over 1 min at pH 5.5 or with 20 μM [3H]MTX at pH 7.4, the latter to compensate, in part, for the high MTX influx Kt at this pH (30). In general, there was a marked loss of influx activity for all the mutants at pH 5.5, although ∼34% of activity was preserved for R148A. Influx mediated by the E185A mutant was ∼15% of influx mediated by WT-PCFT at this pH (Fig. 3, top). The pattern at pH 7.4 was quite different. Influx mediated by all the mutant carriers was far less than influx mediated by WT-PCFT, except for E185A, for which influx was comparable to that mediated by WT-PCFT (Fig. 3, bottom).

Fig. 3.

Determination of MTX influx in R1-11 cells transiently transfected with mock, WT-PCFT, or D156-, E185-, E232-, R148-, or R376-alanine-substituted mutants. Influx of 0.5 μM [3H]MTX at pH 5.5 (top) or 20 μM [3H]MTX at pH 7.4 (bottom) was assessed at 37°C over 1 min. Values are means ± SE from 3 independent experiments.

Kinetic analysis and pH profile of [3H]MTX influx mediated by the E185A-PCFT mutant.

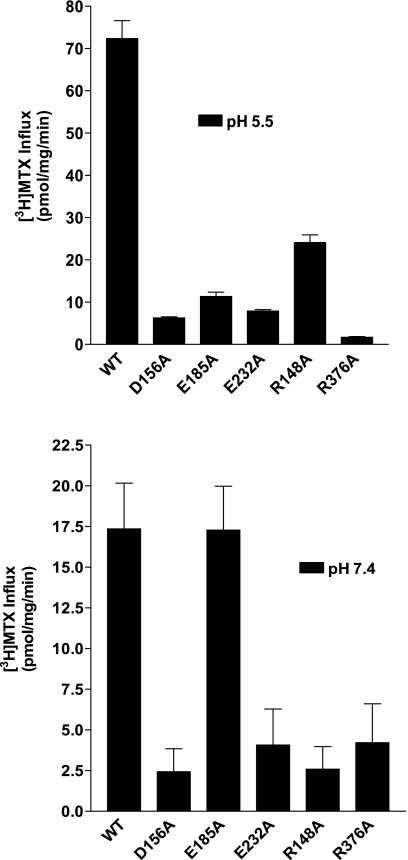

Initial uptake kinetics for [3H]MTX was assessed at pH 5.5 over a concentration range of 0.5–16 μM in cells transiently transfected with WT-PCFT or E185A-PCFT (Fig. 4). The influx Kt values were the same (1.50 ± 0.36 and 1.58 ± 0.16 μM for the WT-PCFT and E185A mutant, respectively). However, there was a marked (∼8-fold) decrease in the influx Vmax (267.5 ± 18.8 and 37.1 ± 1.1 pmol·mg protein−1·min−1, respectively). Hence, the E185A mutation did not affect substrate binding; rather, the difference appeared to be due to a marked decrease in the carrier translocation rate. Since influx at pH 7.4 mediated by the WT-PCFT and E185A mutant was comparable and the E185A mutant protein was expressed at a level similar to that of the WT protein (see Fig. 9), this difference in Vmax cannot be attributed to differences in the level of carriers available for transport at the plasma membrane.

Fig. 4.

[3H]MTX influx kinetics in R1-11 cells transiently transfected with WT-PCFT or the E185A mutant. Influx was assessed over 1 min at pH 5.5. Values are means ± SE from 3 independent experiments.

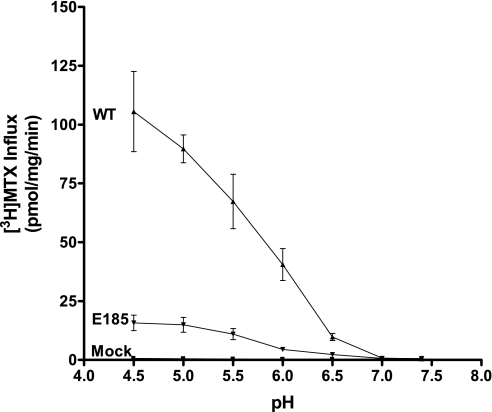

Despite the decrease in E185A function at pH 5.5, influx of [3H]MTX increased as pH was decreased from 7.0 to 4.5. However, the magnitude of the increase in influx was far less (6- to 10-fold) than that observed for WT-PCFT-transfected cells (Fig. 5). Hence, the E185A mutant retains some pH sensitivity.

Fig. 5.

pH dependence of MTX influx for WT-PCFT and the E185A mutant. [3H]MTX (1 μM) uptake over 1 min was assessed over pH 7.4 to 4.5. Values are means ± SE from 3 independent experiments.

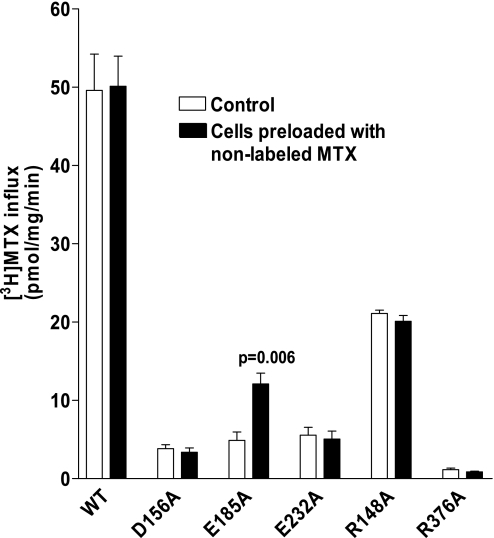

Trans-stimulation of folate transport mediated by WT-PCFT and E185A-PCFT.

For further analysis of the functionality of E185A-PCFT and other mutant PCFTs, [3H]MTX influx was assessed under conditions in which the intracellular (trans) compartment was, or was not, loaded with nonlabeled folate substrates. HeLa-R1-11 cells were transiently transfected with WT-, D156A-, E232A-, R148A-, R376A-, or E185A-PCFT cDNA constructs. The transfected cells were incubated with 200 μM nonlabeled MTX or buffer alone at pH 7.4. After cold washes to remove the extracellular (but not intracellular) folate, influx of 0.5 μM [3H]MTX was assessed over 1 min at pH 5.5. [3H]MTX influx was augmented (trans-stimulated) in cells transfected with E185A-PCFT, but not in cells transfected with WT-PCFT or other mutant PCFTs, under these conditions in which there was a large transmembrane proton gradient (Fig. 6). To determine whether WT-PCFT undergoes trans-stimulation in the absence of a proton gradient and whether trans-stimulation for E185A-PCFT persists, influx of 2.0 μM [3H]MTX was assessed over 1 min at pH 7.4 in control cells (unloaded) and cells preincubated with 200 μM nonlabeled 5-formylTHF for 20 min at pH 7.4. There was a small (25 ± 3.7%) increase (P = 0.08) in [3H]MTX influx in cells transfected with WT-PCFT and loaded with 5-formylTHF. There was a much larger (3.6 ± 0.2-fold, P = 0.03) increase in [3H]MTX influx in cells transfected with the E185A mutant that were loaded with 5-formylTHF.

Fig. 6.

Determination of MTX influx under trans-stimulation conditions in R1-11 cells transiently transfected with mock, WT-PCFT, or PCFT mutants. Influx of 0.5 μM [3H]MTX at pH 5.5 was assessed in control cells and cells preloaded with nonlabeled 200 μM MTX for 20 min at 37°C.

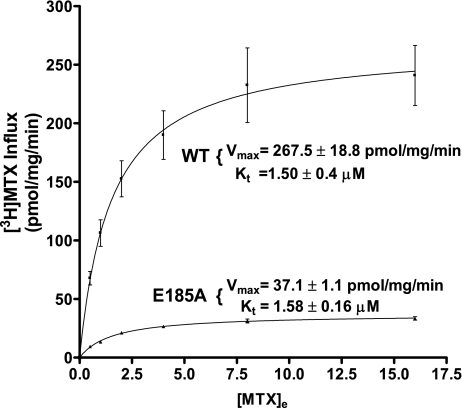

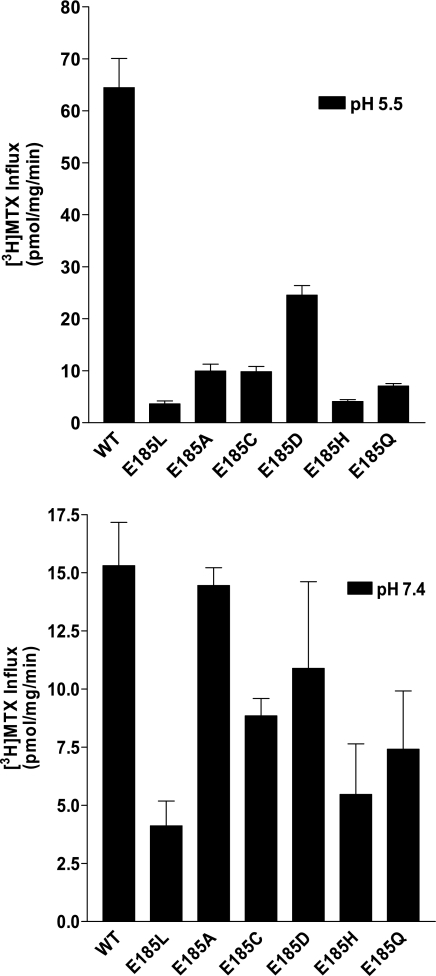

Functional impact of other amino acid substitutions at the E185-PCFT residue.

To further elucidate the role of the E185 residue, Glu was individually substituted with a neutral polar (Gln), physiologically titratable (His), small nonpolar (Ala), polar (Cys), large aliphatic (Leu), or negatively charged (Asp) residue by site-directed mutagenesis. The effects of these replacements on PCFT function were assessed after transient transfection of these constructs into R1-11 cells. As indicated in Fig. 7 (top), at pH 5.5, the residue with the greatest degree of function was E185D (∼38% of WT cells); influx was ∼2.4 greater than that mediated by E185A (P < 0.001). E185D-PCFT-mediated influx at pH 5.5 was also higher than influx mediated by Leu, Cys, His, or Gln substitutions at the E185 position (P < 0.001; Fig. 7, top). Hence, at pH 5.5, Asp, which shares the same charge as Glu, best preserves PCFT function. At pH 7.4 (Fig. 7, bottom), there was no statistically significant difference between influx mediated by WT-PCFT and influx mediated by the E185A, E185C, and E185D mutants (P > 0.05). However, influx mediated by the E185H-, E185Q-, and E185L-PCFT mutants was significantly lower than that of WT-PCFT (P < 0.02, P < 0.03, and P < 0.001, respectively).

Fig. 7.

Determination of MTX influx in R1-11 cells transiently transfected with mock, WT-PCFT, or E185 Leu, Ala, Cys, Asp, His, and Gln substitution mutants. Influx of 0.5 μM [3H]MTX at pH 5.5 (top) or 20 μM [3H]MTX at pH 7.4 (bottom) was assessed at 37°C over 1 min. Values are means ± SE from 3 independent experiments.

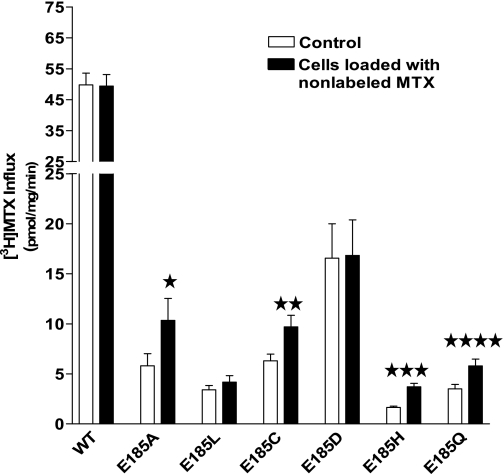

To determine whether trans-stimulation occurs with the other E185-PCFT mutants, influx at pH 5.5 was assessed in control cells and cells loaded with nonlabeled MTX. [3H]MTX influx was trans-stimulated in cells transfected with each of the mutant PCFTs, except in the case of E185L, the least functional of the mutants, and E185D, in which function is best preserved (Fig. 8). Hence, preservation of homoexchange occurs with most E185 mutants with amino acids of different charge and polarity. The lack of trans-stimulation for the Asp mutant may be related to its utilization, in part, of the proton gradient, as observed also for the WT carrier.

Fig. 8.

Determination of MTX influx under trans-stimulation conditions in R1-11 cells transiently transfected with mock, WT-PCFT, or E185 substitution mutants. Influx of 0.5 μM [3H]MTX at pH 5.5 was assessed in control cells and cells preloaded with nonlabeled 200 μM MTX for 20 min at 37°C. ★P = 0.05; ★★P < 0.03; ★★★P < 0.006; ★★★★P < 0.017.

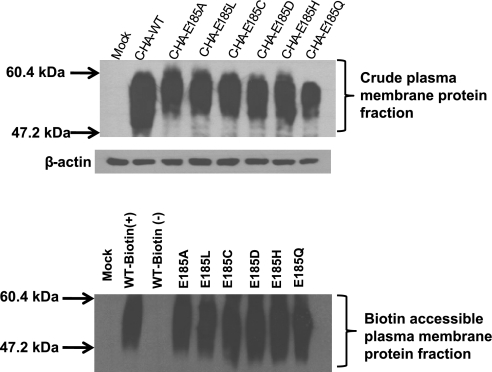

Cellular expression and cell surface localization of E185-PCFT substitution mutants.

Western blot analyses of cell membranes obtained from HeLa-R1-11 cells transiently transfected with mock, C-HA-WT-PCFT, or COOH-terminal HA-tagged E185 Ala, Leu, Cys, Asp, His, or Gln substitution mutants are shown in Fig. 9 (top). At equivalent protein loading, all E185 substitution mutants were expressed at a level comparable to WT-PCFT. The broad band centered at ∼55 kDa is consistent with the glycosylation of this protein, as previously established (46).

Fig. 9.

Western blot and cell surface biotinylation of WT- and E185-PCFT substitution mutant plasma membranes. Top: Western blot. Equal amounts of crude plasma membrane protein fractions (30 μg) prepared from R1-11 cells transiently transfected with the mock, WT-PCFT, or E185 Leu, Ala, Cys, Asp, His, Gln substitution mutants were loaded, and blots were probed with an anti-HA antibody. Molecular sizes in protein ladders are shown at left. β-Actin was the loading control. Blots are representative of 2 separate experiments. Bottom: cell surface biotinylation. R1-11 cells transiently transfected with mock, WT-PCFT, or E185 Leu, Ala, Cys, Asp, His, Gln substitution mutants were treated with 1.8 mM EZ-Link Sulfo-NHS-LC-Biotin. The Sulfo-NHS-LC-Biotin-modified fraction of the indicated proteins were pulled down with streptavidin-agarose beads. Equal amounts of protein (20 μg) were loaded, and blots were probed with an anti-HA antibody. Molecular sizes in a protein ladder are shown at left. Blots are representative of 2 different experiments.

To determine the expression of E185-PCFT mutants at the plasma membrane, cell surface biotinylation was assessed in HeLa-R1-11 cells transiently expressing mock, C-HA-WT-PCFT, and PCFT E185-Ala, -Leu, -Cys, -Asp, -His, and -Gln cDNA constructs. Transfected cells were treated with EZ-Link Sulfo-NHS-LC-Biotin, a membrane-impermeable biotin reagent that covalently reacts with extracellularly accessible primary amine groups. Western blot analysis of the crude plasma membrane protein fraction obtained from these cells revealed the same findings shown in Fig. 9 (top). Western blot analysis of the biotinylated surface proteins of cells transfected with WT-PCFT indicated its accessibility at the plasma membrane (Fig. 9, bottom). Similarly, all E185 substitution mutants were equally available for biotinylation at the plasma membrane and at levels comparable to that of WT-PCFT. No protein was detected on Western blot when the plasma membrane protein fraction was obtained from the biotinylated mock-transfected cells or the nonbiotinylated WT-PCFT-transfected cells. These data indicate that the loss of function for the E185A mutant, as well as the other mutants at this residue, is not due to a defect in membrane trafficking or accessibility to their folate substrates at the plasma membrane.

DISCUSSION

PCFT is a recently identified member of the superfamily of solute transporters that utilizes the trans-epithelial proton gradient to facilitate folate transport across cell membranes (30, 36, 43). Information is now emerging on the structure-function of this transporter, revealed, in part, by loss-of-function mutations in this carrier associated with the autosomal recessive disorder HFM (52). The present study focuses on the role of conserved, charged residues within predicted TMDs, identifying five amino acids that are required for PCFT function: D156 and R376, also reported as mutated in patients with HFM (52), and E185, E232, and R148, which when mutated manifest low transport activities at PCFT's optimal low pH. Of particular interest was the E185 residue, which, unlike the other residues, preserved transport activity at pH 7.4 in the absence of a proton gradient and retained the capacity to undergo homo- and heteroexchange. These observations suggest that the Glu185 residue may play a critical role in proton coupling, and when mutated to a polar residue or a residue of opposite or neutral charge, proton coupling is impaired or lost completely. Further studies were then focused on this residue.

In many prokaryotic and several eukaryotic solute symporters, substrate influx is linked to proton-influx mediated by the same carrier, such that the downhill flow of protons into cells provides the energy for the uphill flow of substrate in the same direction (27, 43). Although protons in solution are in the form of hydronium ions (H3O+), only H+ is conducted across biological membranes by solute carriers through networks of hydrogen bonds formed with the side chains of amino acids lining the translocation pathway (26). Because of their low pKa values, Asp, Glu, and His residues do not bind protons tightly and, therefore, can rapidly exchange these ions in channels (28, 38), pumps (33), and carriers (21). However, identification of amino acid residues involved in proton translocation is difficult, even for transporters in which crystal structures have been solved, since protons cannot be visualized (1). Rather, information on these residues must derive from studies that utilize site-directed mutagenesis and kinetic analyses. Of particular relevance to the present work is the lactose permease (LacY), in which E325 is an irreplaceable residue required for proton translocation by serving as a component of a transmembrane charge-relay system (15).

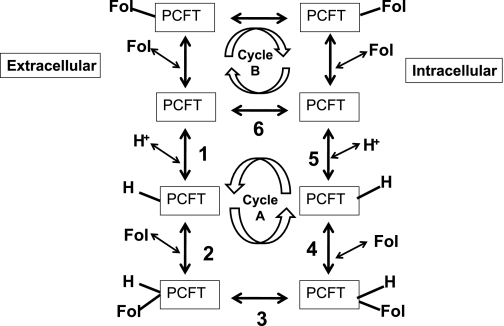

A general kinetic reaction scheme has been developed for secondary active transporters within the context of the “alternate access model” (6, 13) that has evolved through studies on a variety of transporters, in particular, LacY (10, 35). According to this model, the carrier exists in two conformations, inward and outward facing. The model was strengthened when the crystal structures were solved for LacY in an inward-facing state (1) and, very recently, for the nucleobase-cation symporter-1 in an outward-facing open state (48). The information obtained through the crystal structures of prokaryotic transporters LacY and glycerol 3-phosphate transporter (12) have been applied as paradigms for homology modeling of eukaryotic carriers (18), including a proton-coupled transporter (24), for which no three-dimensional structures are available. On the basis of the six-state consecutive LacY transport model (cycle A, Fig. 10), the ordered binding of the cotransported proton (step 1) and the folate (step 2) to the outward-facing unloaded PCFT triggers a conformational change resulting in relocation of the carrier to an inward-facing state (step 3) followed by an ordered release of folate (step 4) and then proton(s) (step 5) into the cytoplasm. The unloaded carrier then returns to the outward-facing state (step 6) to complete the transport cycle.

Fig. 10.

Proposed reaction scheme for PCFT-mediated transport. In cycle A, in the presence of a transmembrane proton gradient, step 5 is rate limiting. In cycle B, in the absence of a proton gradient or when proton-folate transport is uncoupled, step 6 is rate limiting.

The LacY transporter mediates the cotransport of one proton and one lactose molecule across bacterial cell membranes. The E325 residue in LacY is the proton acceptor that, through an interaction with the R302 residue, releases proton(s) into the cytoplasm (4, 29, 34). This deprotonation reaction (step 5) constitutes the rate-limiting event in the reorientation of this carrier from the cytoplasm-facing to the outward-facing state in the transport cycle. When LacY E325 was mutated, transport was uncoupled from the proton gradient, resulting in a marked decrease in Vmax (4, 14, 29). However, the mutated transporter remained capable of exchanging with substrates in the opposite compartment. Transport mediated by the LacY E325A and other substitution mutants was markedly impaired at low pH, except in the case of the similarly charged E325D, but was comparable to the WT carrier at neutral pH. Hence, the E325A-LacY remains functional and can harness its organic substrate gradient to facilitate transport but has lost the capacity to achieve coupling to the proton gradient.

The functional properties of the E185-PCFT residue share much in common with the E325 residue of LacY. There was a profound loss of function for the E185A mutant at pH 5.5 due, solely, to a marked decrease in the influx Vmax; there was no change at all in the influx Kt. Hence, folate binding to PCFT is not influenced by this residue. Transport mediated by the E185A mutant was, however, largely preserved, in contrast to WT-PCFT, at pH 7.4 in the absence of a proton gradient. The E185A mutant, as well as several of the other mutants at this residue, retained the capacity for exchange (trans-stimulation) at low pH; for the E185 mutant, exchange was more prominent at pH 7.4, in the absence of a proton gradient. On the other hand, trans-stimulation could not be detected for WT-PCFT at low pH, with only a marginal change at pH 7.4. These observations are consistent with an expansion of the six-step consecutive model. In the presence of a proton gradient, de-deprotonation of the WT-PCFT, the rate-limiting step, is rapid, and cycle A is dominant. When the E185 residue is mutated to Ala, deprotonation is impaired, and transport at low pH through cycle A becomes negligible; cycle B becomes the dominant route in which step 6 (translocation of the unloaded carrier) is rate limiting. When cells are loaded with folate, the carrier-folate complex translocates at a more rapid rate and influx is stimulated. At neutral pH, there is no pH gradient, transport through cycle A is negligible, transport through cycle B is dominant, and a higher level of trans-stimulation is observed for the mutated PCFT. This model was proposed to account for transport mediated by DMT1 at neutral pH (22). It is unclear why trans-stimulation of WT-PCFT was less than that observed for the E185A mutant at neutral pH; the same phenomenon was observed for DMT1 (22).

It is clear that the glutamate negative charge is an essential property of the E185 residue, since activity at low pH was lost for all the E185 substitutions, irrespective of size or polarity, except for the similarly charged E185D-PCFT mutant, which preserved more than one-third of transport activity. Hence, this residue is capable of facilitating proton exchange, albeit at a lower rate than WT-PCFT. The E325D-LacY mutant also retained considerable transport activity (3, 4). The E185D mutant also resembles WT-PCFT, in that trans-stimulation was not detected at low pH, suggesting that, in contrast to E185A, this mutant cycles through pathway A. Further studies are required to identify other residue(s) that may play a role in the translocation of protons through PCFT, perhaps by interacting with E185.

These and earlier data indicate that PCFT coupling to the transmembrane proton gradient is not absolutely required for function (30, 31, 54). As indicated above, this has been observed also for the proton-coupled DMT1 (22). Although transport is much more rapid when cells are in an acidic environment, a low level of function persists at neutral pH. This is due, at least in part, to the impact of the membrane potential on PCFT-mediated transport (30). Data in this study suggest the important contribution of homoexchange in augmentation of folate fluxes across cell membranes mediated by PCFT when extracellular and intracellular substrate concentrations are very high. This occurs, for instance, after the intravenous administration of pemetrexed in clinical regimens when blood levels of ∼200 μM are achieved (5, 25, 42). It is clear that PCFT can play an important role in the delivery of pemetrexed to tumor cells growing in cell culture at neutral pH by sustaining the activity of this agent in the absence of all other folate transporters (5, 54).

What remains unexplained is the basis for the residual pH sensitivity observed for the E185A-PCFT mutant, albeit, far less than observed for WT-PCFT. This raises the possibility that some residual, less efficient proton coupling may be mediated by another residue. This was the case for LacY, when a second mutation at the K319 residue, added to an E325A mutation, allowed a low level of proton-lactose cotransport (14). Alternatively, protons might alter binding and/or the rate of conformation of the mutated carrier without actually passing across the cell membrane through this mechanism (7, 39).

GRANTS

These studies were supported by National Cancer Institute Grant CA-082621 (I. D. Goldman).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Data in this paper are from E. S. Unal's thesis to be submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate Division of Medical Sciences, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Yeshiva University.

Footnotes

SLC is the Human Genome Organization nomenclature for solute carrier genes. All upper-case designations represent human genes; lower-case designations represent orthologs from other species.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abramson J, Smirnova I, Kasho V, Verner G, Kaback HR, Iwata S. Structure and mechanism of the lactose permease of Escherichia coli. Science 301: 610–615, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andrews NC When is a heme transporter not a heme transporter? When it's a folate transporter. Cell Metab 5: 5–6, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carrasco N, Antes LM, Poonian MS, Kaback HR. Lac permease of Escherichia coli: histidine-322 and glutamic acid-325 may be components of a charge-relay system. Biochemistry 25: 4486–4488, 1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carrasco N, Puttner IB, Antes LM, Lee JA, Larigan JD, Lolkema JS, Roepe PD, Kaback HR. Characterization of site-directed mutants in the lac permease of Escherichia coli. 2. Glutamate-325 replacements. Biochemistry 28: 2533–2539, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chattopadhyay S, Moran RG, Goldman ID. Pemetrexed: biochemical and cellular pharmacology, mechanisms, and clinical applications. Mol Cancer Ther 6: 404–417, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crane RK The gradient hypothesis and other models of carrier-mediated active transport. Rev Physiol Biochem Pharmacol 78: 99–159, 1977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Foltz M, Mertl M, Dietz V, Boll M, Kottra G, Daniel H. Kinetics of bidirectional H+ and substrate transport by the proton-dependent amino acid symporter PAT1. Biochem J 386: 607–616, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Galic S, Schneider HP, Broer A, Deitmer JW, Broer S. The loop between helix 4 and helix 5 in the monocarboxylate transporter MCT1 is important for substrate selection and protein stability. Biochem J 376: 413–422, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grewer C, Watzke N, Rauen T, Bicho A. Is the glutamate residue Glu-373 the proton acceptor of the excitatory amino acid carrier 1? J Biol Chem 278: 2585–2592, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guan L, Kaback HR. Lessons from lactose permease. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct 35: 67–91, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Helmlinger G, Yuan F, Dellian M, Jain RK. Interstitial pH and Po2 gradients in solid tumors in vivo: high-resolution measurements reveal a lack of correlation. Nat Med 3: 177–182, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang Y, Lemieux MJ, Song J, Auer M, Wang DN. Structure and mechanism of the glycerol-3-phosphate transporter from Escherichia coli. Science 301: 616–620, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jardetzky O Simple allosteric model for membrane pumps. Nature 211: 969–970, 1966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnson JL, Brooker RJ. A K319N/E325Q double mutant of the lactose permease cotransports H+ with lactose. Implications for a proposed mechanism of H+/lactose symport. J Biol Chem 274: 4074–4081, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaback HR, Sahin-Toth M, Weinglass AB. The Kamikaze approach to membrane transport. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2: 610–620, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kamen BA, Smith AK. A review of folate receptor-α cycling and 5-methyltetrahydrofolate accumulation with an emphasis on cell models in vitro. Adv Drug Delivery Res 56: 1085–1097, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lam-Yuk-Tseung S, Govoni G, Forbes J, Gros P. Iron transport by Nramp2/DMT1: pH regulation of transport by 2 histidines in transmembrane domain 6. Blood 101: 3699–3707, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lemieux MJ Eukaryotic major facilitator superfamily transporter modeling based on the prokaryotic GlpT crystal structure. Mol Membr Biol 24: 333–341, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lichtarge O, Sowa ME. Evolutionary predictions of binding surfaces and interactions. Curr Opin Struct Biol 12: 21–27, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Livingstone CD, Barton GJ. Identification of functional residues and secondary structure from protein multiple sequence alignment. Methods Enzymol 266: 497–512, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Luecke H, Richter HT, Lanyi JK. Proton transfer pathways in bacteriorhodopsin at 2.3 angstrom resolution. Science 280: 1934–1937, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mackenzie B, Ujwal ML, Chang MH, Romero MF, Hediger MA. Divalent metal-ion transporter DMT1 mediates both H+-coupled Fe2+ transport and uncoupled fluxes. Pflügers Arch 451: 544–558, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matherly LH, Goldman DI. Membrane transport of folates. Vitam Horm 66: 403–456, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meredith D, Price RA. Molecular modeling of PepT1—towards a structure. J Membr Biol 213: 79–88, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mita AC, Sweeney CJ, Baker SD, Goetz A, Hammond LA, Patnaik A, Tolcher AW, Villalona-Calero M, Sandler A, Chaudhuri T, Molpus K, Latz JE, Simms L, Chaudhary AK, Johnson RD, Rowinsky EK, Takimoto CH. Phase I and pharmacokinetic study of pemetrexed administered every 3 wk to advanced cancer patients with normal and impaired renal function. J Clin Oncol 24: 552–562, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Onsager L The motion of ions: principles and concepts. Science 166: 1359–1364, 1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pao SS, Paulsen IT, Saier MH Jr. Major facilitator superfamily. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 62: 1–34, 1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pinto LH, Dieckmann GR, Gandhi CS, Papworth CG, Braman J, Shaughnessy MA, Lear JD, Lamb RA, DeGrado WF. A functionally defined model for the M2 proton channel of influenza A virus suggests a mechanism for its ion selectivity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94: 11301–11306, 1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Puttner IB, Sarkar HK, Padan E, Lolkema JS, Kaback HR. Characterization of site-directed mutants in the lac permease of Escherichia coli. 1. Replacement of histidine residues. Biochemistry 28: 2525–2533, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Qiu A, Jansen M, Sakaris A, Min SH, Chattopadhyay S, Tsai E, Sandoval C, Zhao R, Akabas MH, Goldman ID. Identification of an intestinal folate transporter and the molecular basis for hereditary folate malabsorption. Cell 127: 917–928, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Qiu A, Min SH, Jansen M, Malhotra U, Tsai E, Cabelof DC, Matherly LH, Zhao R, Akabas MH, Goldman ID. Rodent intestinal folate transporters (SLC46A1): secondary structure, functional properties, and response to dietary folate restriction. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 293: C1669–C1678, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rahman B, Schneider HP, Broer A, Deitmer JW, Broer S. Helix 8 and helix 10 are involved in substrate recognition in the rat monocarboxylate transporter MCT1. Biochemistry 38: 11577–11584, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rastogi VK, Girvin ME. Structural changes linked to proton translocation by subunit c of the ATP synthase. Nature 402: 263–268, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sahin-Toth M, Kaback HR. Arg-302 facilitates deprotonation of Glu-325 in the transport mechanism of the lactose permease from Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 6068–6073, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sahin-Toth M, Karlin A, Kaback HR. Unraveling the mechanism of the lactose permease of Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 10729–10732, 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saier MH Jr, Beatty JT, Goffeau A, Harley KT, Heijne WH, Huang SC, Jack DL, Jahn PS, Lew K, Liu J, Pao SS, Paulsen IT, Tseng TT, Virk PS. The major facilitator superfamily. J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol 1: 257–279, 1999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sharif KA, Goldman ID. Rapid determination of membrane transport parameters in adherent cells. Biotechniques 28: 926–932, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Starace DM, Bezanilla F. Histidine scanning mutagenesis of basic residues of the S4 segment of the Shaker K+ channel. J Gen Physiol 117: 469–490, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Steel A, Nussberger S, Romero MF, Boron WF, Boyd CA, Hediger MA. Stoichiometry and pH dependence of the rabbit proton-dependent oligopeptide transporter PepT1. J Physiol 498: 563–569, 1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stokstad ELR Historical perspective on key advances in the biochemistry and physiology of folates. In: Folic Acid Metabolism in Health and Disease, edited by MF Picciano and ELR Stokstad. New York: Wiley-Liss, 1990, p. 1–21.

- 41.Stover PJ Physiology of folate and vitamin B12 in health and disease. Nutr Rev 62: S3–S12, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Takimoto CH, Hammond-Thelin LA, Latz JE, Forero L, Beeram M, Forouzesh B, de Bono J, Tolcher AW, Patnaik A, Monroe P, Wood L, Schneck KB, Clark R, Rowinsky EK. Phase I and pharmacokinetic study of pemetrexed with high-dose folic acid supplementation or multivitamin supplementation in patients with locally advanced or metastatic cancer. Clin Cancer Res 13: 2675–2683, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thwaites DT, Anderson CM. H+-coupled nutrient, micronutrient and drug transporters in the mammalian small intestine. Exp Physiol 92: 603–619, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tredan O, Galmarini CM, Patel K, Tannock IF. Drug resistance and the solid tumor microenvironment. J Natl Cancer Inst 99: 1441–1454, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Umapathy NS, Gnana-Prakasam JP, Martin PM, Mysona B, Dun Y, Smith SB, Ganapathy V, Prasad PD. Cloning and functional characterization of the proton-coupled electrogenic folate transporter and analysis of its expression in retinal cell types. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 48: 5299–5305, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Unal ES, Zhao R, Qiu A, Goldman ID. N-linked glycosylation and its impact on the electrophoretic mobility and function of the human proton-coupled folate transporter (HsPCFT). Biochim Biophys Acta 1178: 1407–1414, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.von Heijne G Membrane-protein topology. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 7: 909–918, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Weyand S, Shimamura T, Yajima S, Suzuki S, Mirza O, Krusong K, Carpenter EP, Rutherford NG, Hadden JM, O'Reilly J, Ma P, Saidijam M, Patching SG, Hope RJ, Norbertczak HT, Roach PC, Iwata S, Henderson PJ, Cameron AD. Structure and molecular mechanism of a nucleobase-cation-symport-1 family transporter. Science 322: 709–713, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhao R, Babani S, Gao F, Liu L, Goldman ID. The mechanism of transport of the multitargeted antifolate, MTA-LY231514, and its cross resistance pattern in cell with impaired transport of methotrexate. Clin Cancer Res 6: 3687–3695, 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhao R, Gao F, Hanscom M, Goldman ID. A prominent low-pH methotrexate transport activity in human solid tumor cells: contribution to the preservation of methotrexate pharmacological activity in HeLa cells lacking the reduced folate carrier. Clin Cancer Res 10: 718–727, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhao R, Matherly LH, Goldman ID. Membrane transporters and folate homeostasis: intestinal absorption and transport into systemic compartments and tissues. Expert Rev Mol Med 11: e4, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhao R, Min SH, Qiu A, Sakaris A, Goldberg GL, Sandoval C, Malatack JJ, Rosenblatt DS, Goldman ID. The spectrum of mutations in the PCFT gene, coding for an intestinal folate transporter, that are the basis for hereditary folate malabsorption. Blood 110: 1147–1152, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhao R, Min SH, Wang Y, Campanella E, Low PS, Goldman ID. A role for the proton-coupled folate transporter (PCFT-SLC46A1) in folate receptor-mediated endocytosis. J Biol Chem 284: 4267–4274, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhao R, Qiu A, Tsai E, Jansen M, Akabas MH, Goldman ID. The proton-coupled folate transporter (PCFT): impact on pemetrexed transport and on antifolate activities compared with the reduced folate carrier. Mol Pharmacol 74: 854–862, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zvelebil MJ, Barton GJ, Taylor WR, Sternberg MJ. Prediction of protein secondary structure and active sites using the alignment of homologous sequences. J Mol Biol 195: 957–961, 1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.