Abstract

Type 2 diabetes is characterized by hyperlipidemia, hyperinsulinemia, and insulin resistance. The aim of this study was to investigate whether acute hyperlipidemia-induced insulin resistance in the presence of hyperinsulinemia was due to defective insulin signaling. Hyperinsulinemia (∼300 mU/l) with hyperlipidemia or glycerol (control) was produced in cannulated male Wistar rats for 0.5, 1 h, 3 h, or 5 h. The glucose infusion rate required to maintain euglycemia was significantly reduced by 3 h with lipid infusion and was further reduced after 5 h of infusion, with no difference in plasma insulin levels, indicating development of insulin resistance. Consistent with this finding, in vivo skeletal muscle glucose uptake (31%, P < 0.05) and glycogen synthesis rate (38%, P < 0.02) were significantly reduced after 5 h compared with 3 h of lipid infusion. Despite the development of insulin resistance, there was no difference in the phosphorylation state of multiple insulin-signaling intermediates or muscle diacylglyceride and ceramide content over the same time course. However, there was an increase in cumulative exposure to long-chain acyl-CoA (70%) with lipid infusion. Interestingly, although muscle pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 4 protein content was decreased in hyperinsulinemic glycerol-infused rats, this decrease was blunted in muscle from hyperinsulinemic lipid-infused rats. Decreased pyruvate dehydrogenase complex activity was also observed in lipid- and insulin-infused animals (43%). Overall, these results suggest that acute reductions in muscle glucose metabolism in rats with hyperlipidemia and hyperinsulinemia are more likely a result of substrate competition than a significant early defect in insulin action or signaling.

Keywords: lipotoxicity, hyperlipidemia, in vivo metabolism, long-chain acyl-CoA, pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 4

elevated circulating fatty acids have been proposed to be a major contributing factor in the pathogenesis of skeletal muscle insulin resistance. A number of mechanisms involved in insulin resistance arising from lipid oversupply have been suggested; the majority of these mechanisms ultimately result in defective activation of the insulin-signaling pathway to reduce GLUT4 translocation to the plasma membrane (39). These proposed defects in insulin signaling are thought to occur predominantly via two loci: reduced activating tyrosine phosphorylation resulting from increased inhibitory serine phosphorylation of insulin receptor substrate-1 (IRS-1) or reduced serine/threonine phosphorylation of Akt. A number of mediators have been proposed to inhibit IRS-1 activation: JNK activation (51), potentially by fatty acid signaling through Toll-like receptors-2 and -4 (37) or by accumulation of ceramide (37, 50); IKK-NF-κB (28); and diacylglyceride (DAG) activation of PKCs (56). These pathways have been suggested to increase inhibitory phosphorylation of IRS-1 on Ser307, which can decrease IRS-1 tyrosine phosphorylation and IRS-1-associated phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase activity (39). Degradation of IRS-1 protein levels has also been suggested as a process whereby insulin signaling is reduced in insulin-resistant states (57). Inhibition of Akt activation is thought to be due to increased activation of the protein phosphatase 2A (45) or PKCζ/λ (40) by accumulated ceramide.

The majority of in vivo studies that have implicated defects in insulin signaling as a mechanism for insulin resistance have done so in models of hyperlipidemia, including high-fat feeding (12, 55, 58) and acute lipid infusion (11, 18, 20, 50). Additional work has shown that incubation of isolated muscles or cultured myotubes with high fatty acid [predominantly palmitate (C16)] concentrations leads to an impairment in insulin signaling and reduced insulin action (1, 19, 56). For the lipid infusion studies, numerous protocols have been used to investigate how lipid oversupply induces insulin resistance. The majority of these investigations have involved infusion of lipid (and heparin) for 0.5–24 h followed by commencement of insulin sensitivity measures such as hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamps (0.5 to 2 h) (3, 8, 16, 29, 30, 49, 50, 52). With such a degree of variation in the lipid infusion protocols, it perhaps is no surprise that a range of mechanisms, which are mentioned above, have been proposed to support the development of insulin resistance. Further complicating the identification of the mechanisms involved is some conjecture over the involvement of some of these mechanisms, including JNK signaling. Bhatt et al. (3) demonstrated that lipid infusion did not alter skeletal muscle JNK activity. However, they did not measure insulin signaling. Furthermore, a recent in vitro study reported that, in isolated soleus muscle, 6 h of palmitate incubation reduced acute insulin-stimulated glucose uptake and membrane GLUT4 protein, did not change Akt phosphorylation (Thr308 and Ser473), and reduced AS160 phosphorylation (1). In the majority of investigations of the mechanisms associated with lipid oversupply-induced insulin resistance in skeletal muscle, insulin was not elevated from the commencement of the lipid infusion (3, 8, 11, 16, 18, 20, 29, 30, 49, 50, 52). This is important, inasmuch as hyperlipidemia is often associated with hyperinsulinemia in human subjects with type 2 diabetes (4).

Therefore, the aim of the present study was to determine whether the onset of insulin resistance in skeletal muscle caused by acute lipid and insulin infusion was associated with defective insulin signaling.

METHODS

Animals

All surgical and experimental procedures were approved by the Animal Ethics Committee (Garvan Institute/St. Vincent's Hospital) and were in accordance with the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia's guidelines on animal experimentation.

Adult male Wistar rats (Animal Resources Centre, Perth, Australia) were communally housed at 22 ± 0.5°C with a controlled 12:12-h light-dark cycle (lights on from 0700 to 1900). They were fed ad libitum a standard rodent diet (Rat Maintenance Diet, Gordons Specialty Feeds, Sydney, Australia) containing 10% fat, 69% carbohydrate, and 21% (wt/wt) protein plus fiber, vitamins, and minerals. After 1 wk of acclimatization, rats were anesthetized with a combination of ketamine (Ketalar, 80 mg/kg) and xylazine (Ilium Xylazil, 20 mg/kg) injected intraperitoneally. Cannulas were implanted into the right and left jugular veins under aseptic conditions. Catheters were exteriorized at the back of the neck. Rats were housed individually after surgery and handled daily to minimize stress. Average body weight on the experimental day was 300–350 g.

Lipid Infusion

Animals were deprived of food for ≥5 h overnight and randomly assigned to the lipid-infused or control group before study. The lipid-infused group received 12% Intralipid (diluted with normal saline from Intralipid 20%; Baxter Healthcare, Sydney, Australia). The fatty acid composition of Intralipid is as follows: 1% myristic acid (14:0), 11% palmitic acid (16:0), 4% stearic acid (18:0), 20.8% oleic acid (18:1), 53% linoleic acid (18:2), 7% α-linolenic acid (18:3), and 3.2% other fatty acids. The rate of infusion was 2 ml/h, with a concomitant heparin infusion of 40 U/h to aid in the lipolysis of the triglyceride emulsion. To match the glycerol released from the triglyceride emulsion, control animals were infused with 3% glycerol. Both groups were infused for 0, 0.5, 1, 3, or 5 h. Both groups received insulin (Actrapid, Novo Nordisk, Copenhagen, Denmark) to achieve levels similar to those observed in the glucose infusion model (∼300 mU/l) (22): lipid-infused animals received 0.35 U·kg−1·h−1, and the control group received 0.6 U·kg−1·h−1. Glucose (50% solution) was infused via a peristaltic roller pump (model 101U/R, Watson-Marlow, Falmouth, UK). A blood sample was taken every 30 min, and the glucose infusion rate (GIR) was adjusted to maintain a whole blood glucose concentration of 4.5–5.5 mM. In one cohort, 33.8 μCi of 2-deoxy-d-[2,6-3H]glucose ([3H]2DG) and 22.5 μCi of [U-14C]glucose (Amersham Biosciences, Buckinghamshire, UK) were administered as an intravenous bolus 60 min before the animals were euthanized. Blood samples (200 μl) were taken at 2, 15, 30, 45, and 60 min after administration of the bolus for estimation of plasma tracer and glucose concentration. Then the animals were euthanized with an overdose of pentobarbital sodium (Nembutal, Abbott Laboratories, Sydney, Australia). Tissues were rapidly removed, freeze-clamped, and stored at −80°C for subsequent analyses. Rats had free access to water throughout the infusion.

Analytic Methods

Blood and plasma glucose levels were determined by an immobilized glucose oxidase method (model YSI 2300, Yellow Springs Instruments, Yellow Springs, OH). Plasma insulin was measured by radioimmunoassay kit (Linco, St. Louis, MO). Plasma nonesterified fatty acid (NEFA) levels were determined spectrophotometrically using a commercially available kit (NEFA-C, WAKO Pure Chemical Industries, Osaka, Japan).

Plasma and tissue levels of 3H- and 14C-labeled tracers were measured as described previously to calculate whole body and muscle glucose uptake; tissue glycogen concentration and [14C]glucose incorporation rates into glycogen were also calculated (23). Red quadriceps (RQ) triglycerides were extracted using the method of Folch et al. (10) and quantified using an enzymatic colorimetric method (GPO-PAP reagent, Roche Diagnostics). DAG, ceramide, and long-chain acyl-CoAs (LCACoAs) were extracted and quantified according to published methods (2, 41). Pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) complex (PDHC) activity was measured in whole tissue homogenates prepared in 5 vol of 50 mM potassium phosphate, 10 mM EGTA, 2 mM dithiothreitol, 2% BSA, 10 μg/ml aprotinin, 10 μM leupeptin, and 1 mM PMSF. PDHC activity was determined spectrophotometrically at 30°C as previously described (27). PDHC activity was expressed relative to citrate synthase activity, which was determined at 30°C, as described previously (35).

Skeletal muscle homogenates were subjected to protein extraction and immunoblotting, as previously described (22). Densitometry was performed using IPLab Gel software (Signal Analytics, Vienna, VA). Antibodies for anti-insulin receptor-β were obtained from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA); anti-phospho-Tyr1162/63 insulin receptor from BioSource International (Camarillo, CA); anti-phospho-Tyr612 IRS-1 from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO); anti-Akt, anti-phospho-Ser473 Akt, anti-glycogen synthase kinase (GSK)-3β, anti-GSK3α, anti-phospho-Ser21/9 GSK3α/β, anti-IRS-1, anti-IκBα, anti-phospho-Thr183/Tyr185 JNK, and anti-JNK from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA); anti-AS160 from Upstate Biotechnology (Lake Placid, NY); and anti-14-3-3β from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Anti-phospho-Thr642 AS160 was a gift from Symansis (Auckland, New Zealand).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using Prism5 (Graphpad Software, San Diego, CA). Differences among relevant groups were assessed using unpaired Student's t-test or ANOVA with Tukey-Kramer post hoc tests as appropriate. P < 0.05 was considered significant. Values are means ± SE.

RESULTS

Plasma Parameters Before and After Chronic Infusion of Lipid

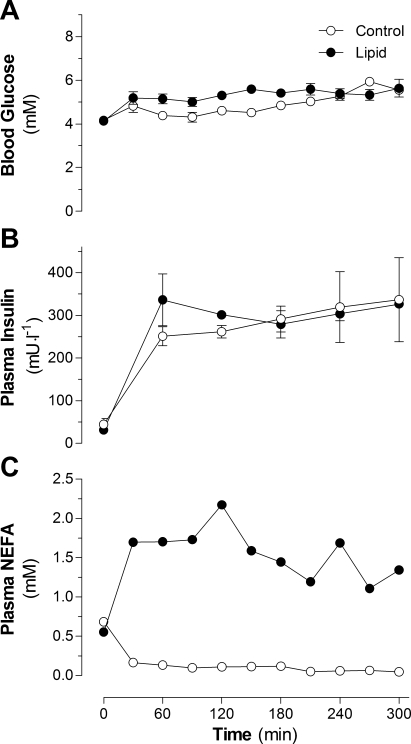

There was no difference in basal blood glucose levels between control and lipid-infused animals (4.13 ± 0.15 and 4.06 ± 0.09 mM, respectively). During the infusions, average blood glucose was 4.84 ± 0.07 and 5.33 ± 0.07 mM for the control and lipid-infused groups, respectively (Fig. 1A). Fasting plasma insulin was 45 ± 14 mU/l and increased to an average of 280 ± 16 mU/l for the control group; in the lipid-infused group, fasting plasma insulin was 31 ± 6 mU/l and increased to an average of 314 ± 26 mU/l (Fig. 1B). No difference in basal plasma NEFA levels was observed between control and lipid-infused groups: 0.69 ± 0.05 and 0.65 ± 0.04 mM, respectively. Average circulating NEFA levels were 0.11 ± 0.01 and 1.60 ± 0.06 mM in control and lipid-infused animals, respectively (Fig. 1C). Overall, the two groups were well matched for circulating glucose and insulin levels, whereas NEFA levels were significantly different.

Fig. 1.

Blood glucose (A), plasma insulin (B), and plasma nonesterified fatty acids (NEFA; C) in rats infused with lipid or glycerol (control) for 5 h. Values are means ± SE (n = 10–12 rats per group).

Glucose Metabolism and Insulin Sensitivity

Whole body glucose metabolism.

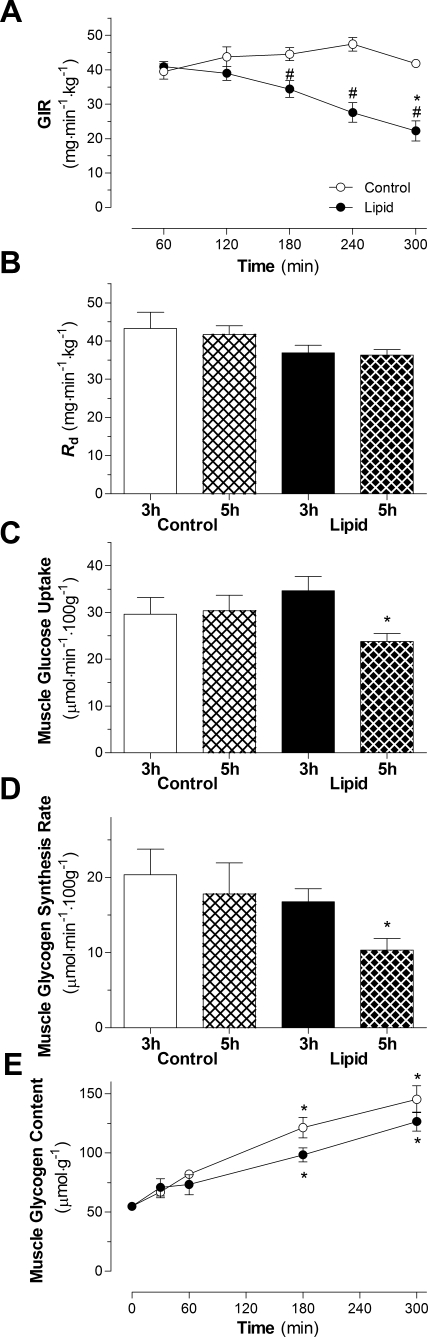

The GIR required to maintain euglycemia was stable throughout the 5-h infusion for the control group (Fig. 2A). In the lipid-infused group, GIR was stable for the first 2 h but was significantly reduced after 3, 4, and 5 h compared with 1 h of lipid infusion (Fig. 2A). The length of infusion had no significant effect on whole body glucose disappearance in the control or lipid-infused group (Fig. 2B). There was no significant effect on Rd between control and lipid-infused animals. Hepatic glucose output remained suppressed in the control group (−0.34 ± 2.24 and 0.97 ± 0.89 mg·min−1·kg−1 at 3 and 5 h in the control group, respectively). However, there was a strong trend for an increase in hepatic glucose output in the 5-h lipid-infused group compared with the 5-h control-infused group (4.75 ± 0.24 and 10.79 ± 4.12 mg·min−1·kg−1 at 3 and 5 h, respectively, in the lipid-infused group, P = 0.07).

Fig. 2.

Effect of lipid infusion on whole body indexes of insulin sensitivity. A: glucose infusion rate (GIR) required to maintain euglycemia in rats infused with lipid or glycerol and insulin for 5 h. *P < 0.05 vs. 60 min of lipid infusion (by ANOVA). #P < 0.05 vs. control infusion (by ANOVA). B–D: rate of glucose disappearance (Rd), red quadriceps glucose uptake, and glycogen synthesis rate in animals after 3 and 5 h of glycerol or lipid infusion in the presence of hyperinsulinemia. *P < 0.05 vs. 3-h lipid infusion (by ANOVA). E: glycogen content in animals infused with lipid or glycerol and insulin for 5 h. Values are means ± SE (n = 5–7 rats per group). *P < 0.05 vs. Basal.

Skeletal muscle insulin sensitivity and glucose metabolism.

The ability of insulin to stimulate glucose uptake in muscle of control animals was similar after 3 and 5 h of infusion (Fig. 2C). Glucose uptake in RQ was significantly reduced after 5 h compared with 3 h of lipid infusion (31%, P = 0.008; Fig. 2C). In the mixed-fiber tibialis cranialis and white quadriceps, there was also a significant reduction in glucose uptake after 5 h compared with 3 h of lipid infusion [33% (P = 0.005) and 37% (P = 0.04), respectively; data not shown]. Consistent with the reduction in glucose uptake, in vivo rates of glycogen synthesis in RQ muscle were significantly reduced in the 5-h lipid-infused group compared with the 3-h lipid-infused group (38%, P = 0.02; Fig. 2D). This reduction in the rate of glycogen synthesis was not related to the glycogen content, which was similar to glycogen content in the control group (Fig. 2E).

Skeletal muscle insulin signaling.

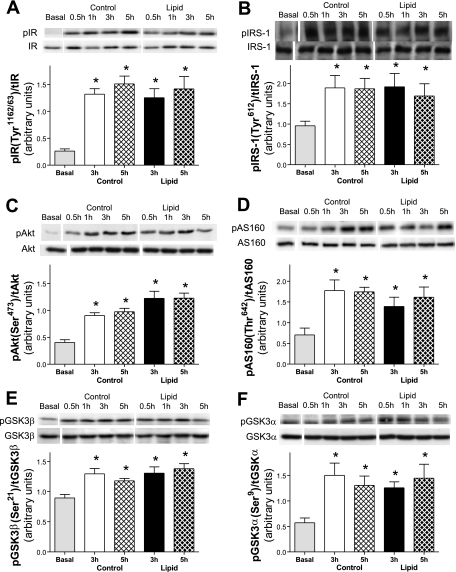

To determine whether changes in insulin signaling accompanied the development of insulin resistance in RQ, the activation state of several key components of the insulin-signaling pathway involved in glucose metabolism were examined. Phosphorylation of the insulin receptor (Tyr1162/1163; Fig. 3A) was increased and remained elevated in control and lipid-infused animals. Additionally, phosphorylation of IRS-1 (Tyr612) was significantly increased and sustained in control and lipid-infused animals (Fig. 3B). Phosphorylation of Akt (Ser473; Fig. 3C) and its downstream targets involved in glucose metabolism, AS160 (Thr642; Fig. 3D), GSK3β (Ser21; Fig. 3E), and GSK3α (Ser9; Fig. 3F), was increased and maintained with prolonged control and lipid infusion. There was no change in total protein expression of any of these signaling components. Densitometry measurements demonstrated no significant reduction in the phosphorylation state for most intermediates between control and lipid-infused animals at 3 or 5 h, despite the significant impairment in glucose uptake during this period of lipid infusion (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 3.

Effect of lipid infusion on skeletal muscle insulin signaling intermediates, expressed as ratio of phosphorylated (p) to total (t) intermediate. A: insulin receptor (IR) activation (Tyr1162/63). B: insulin receptor substrate 1 (IRS-1) activation (Tyr612). C: Akt (Ser473). D: AS160 (Thr642). E: glycogen synthase kinase (GSK)-3β (Ser21). F: GSK3α (Ser9). Intermediates were measured in red quadriceps in the basal state and after 3 and 5 h of glycerol or lipid infusion in the presence of hyperinsulinemia. Values are means ± SE (n = 5–7 rats per group). *P < 0.05 vs. basal (by ANOVA).

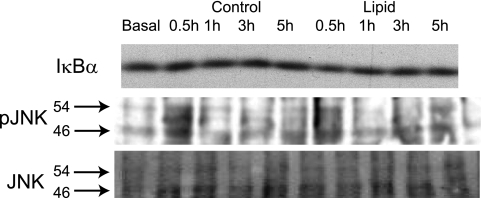

Skeletal muscle inflammatory signaling.

Inflammatory signaling has been proposed as a mechanism that can impair insulin signaling (47). There was no change in the total protein content of IκBα, which was used as a surrogate marker of IKK-NF-κB signaling activation, in the lipid-infused or control group (Fig. 4A). Phosphorylation of JNK was also not altered with prolonged control or lipid infusion (Fig. 4B). The absence of changes in inflammatory signaling is consistent with the lack of alterations in insulin signaling in this model of hyperinsulinemia and hyperlipidemia.

Fig. 4.

Effects of lipid infusion on skeletal muscle inflammatory signaling. IκBα and JNK (Thr183/Tyr185) were measured in red quadriceps from control and lipid-infused animals in the presence of insulin.

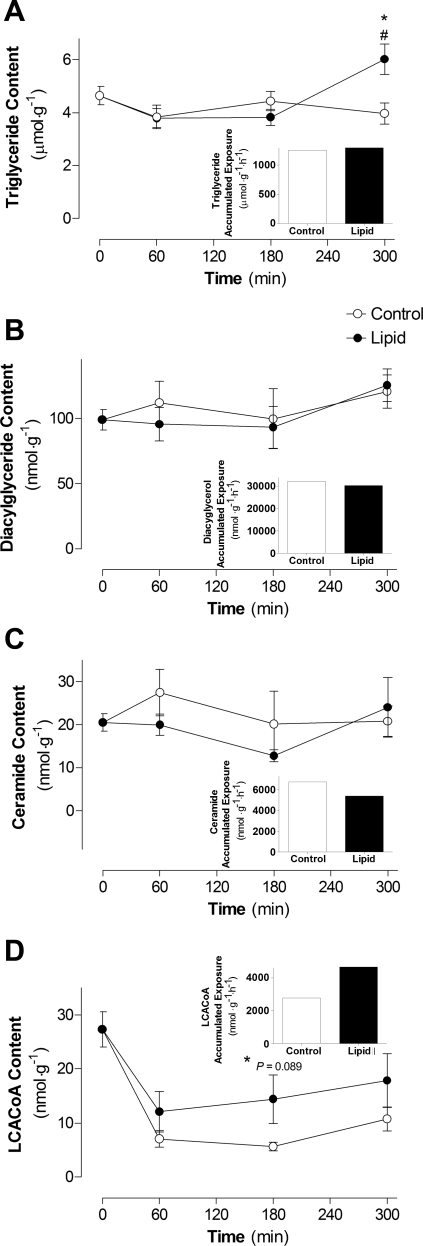

Skeletal muscle lipid content.

There was a significant increase in triglyceride content after 5 h of lipid infusion compared with 3 h of lipid infusion and 5 h of control infusion (P < 0.01; Fig. 5A). There was no significant difference in DAG or ceramide content between lipid and control infusion or during the course of the infusion (Fig. 5, B and C). These findings are consistent with the fact that there was also no defect in key insulin-signaling intermediates (Fig. 3).

Fig. 5.

Effects of lipid infusion on skeletal muscle lipid intermediates: triglyceride (A), diacylglyceride (B), ceramide (C), and long chain acyl-CoA (LCACoA, D) content and accumulated exposure (insets). Lipid intermediates were measured in red quadriceps from control and lipid-infused animals in the presence of insulin. Values are means ± SE (n = 5–7 rats per group). #P < 0.05 vs. Basal; *P < 0.05 vs. 5-h control infusion.

Insulin rapidly suppressed LCACoA content in the control and lipid-infused groups, and it remained suppressed for the duration of the control infusion (Fig. 5D). However, LCACoA content showed a trend toward an increase after 3 h of lipid infusion compared with control infusion. The accumulated exposure to LCACoA over the course of the infusion (measured as area under the curve) was increased by 70% with lipid infusion compared with control infusion (Fig. 5D, inset). LCACoAs have been suggested to inhibit hexokinase (HK) activity and, thereby, influence glucose uptake (46). As an indirect marker of HK activity, there was a 34% reduction in the ratio of [3H]2DG-6-phosphate to [3H]2DG after 5 h of lipid infusion compared with the control group (5.70 ± 1.55 vs. 3.77 ± 0.84). This represents a potential mechanism by which the rate of glucose uptake and glycogen synthesis was reduced in lipid-infused animals (Fig. 2, C and D), independently of an insulin-signaling defect (Fig. 3).

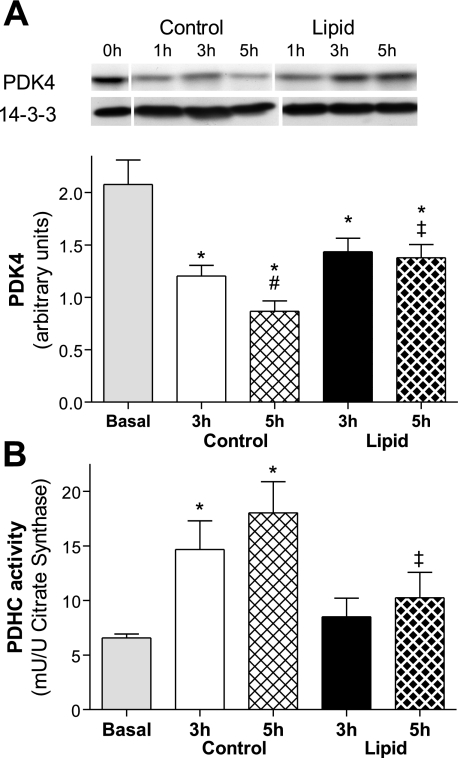

PDK content and PDHC activity.

PDHC regulates the entry of glucose carbons into the mitochondrial tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle for complete oxidation to CO2. The activity of PDH is regulated by PDK, which phosphorylates PDH to inhibit its activity. Protein content of PDK4 was significantly reduced from basal levels (2.07 ± 0.23 arbitrary units) after 3 h of control or lipid infusion [42% (P = 0.01) and 30% (P = 0.04), respectively; Fig. 6A]. PDK4 was further reduced after 5 h of control infusion (28%, P = 0.04). However, PDK4 was unchanged after 5 h of lipid infusion and, at this time point, was significantly elevated compared with 5 h of control infusion (59%, P = 0.01; Fig. 6A). This indicates that lipid infusion may reduce the ability of insulin to reduce PDK4 protein.

Fig. 6.

Effect of lipid infusion on skeletal muscle pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase (PDK4) content (A) and pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (PDHC) activity (B). Activities were measured in the basal state and after 3 and 5 h of glycerol or lipid infusion in the presence of hyperinsulinemia in red quadriceps. Values are means ± SE (n = 5–7 rats per group). *P < 0.05 vs. basal; #P < 0.05 vs. 3 h control; ‡P < 0.05 vs. 5 h control (by 1-way ANOVA).

To determine whether the changes in PDK4 protein content altered activity of its downstream target, PDHC activity was investigated. PDHC activity was increased compared with basal level after 3 and 5 h of control infusion [1.2-fold (P = 0.02) and 1.7-fold (P = 0.005), respectively; Fig. 6B]. After 5 h of lipid infusion, PDHC activity was reduced (43%, P = 0.02) compared with 5 h of control infusion, which was consistent with the higher level of PDK4 protein.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we investigated whether oversupply of lipid in the presence of high insulin resulted in skeletal muscle insulin resistance due to an insulin-signaling defect. Despite skeletal muscle insulin resistance, we observed no attenuation of protein phosphorylation of intermediates of the insulin-signaling cascade, including the insulin receptor IRS-1, Akt, and its downstream targets AS160 and GSK3α/β. The insulin resistance in this model of hyperlipidemia and hyperinsulinemia was potentially due to changes in PDHC activity as a result of altered PDK4 content and prolonged exposure to elevated LCACoA. Overall, our results suggest that metabolic feedback, rather than significant alterations in insulin signaling, may mediate the onset of insulin resistance in this model.

The use of acute lipid infusion in rodents as a model of elevated circulating free fatty acids has provided some insight into the potential mechanism(s) by which insulin resistance may be generated by chronic energy imbalance. At the whole body level, lipid infusion reduces the GIR required to maintain euglycemia and, at the tissue level, reduces peripheral glucose disposal and insulin-mediated suppression of hepatic glucose production during insulin stimulation (5, 7, 29, 53). In skeletal muscle, insulin resistance is associated with reduced glucose uptake, glycolysis, and glycogen synthesis (5, 29). Furthermore, defects in activation of components of the insulin-signaling pathway have been linked with skeletal muscle insulin resistance. These defects include reduced tyrosine phosphorylation of IRS-1, which is thought to be due to increased inhibitory serine phosphorylation, reduced phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase activity, reduced Akt1 (but not Akt2 or Akt3) activation, decreased PKCλ/ζ activation, and lower glycogen synthase activity and phosphorylation (11, 17, 29, 30, 50). Accumulation of active lipid intermediates, such as DAG, ceramide, and LCACoA, has been linked with insulin resistance (5, 8, 20, 53, 56). The accumulation of these lipid intermediates has been suggested to activate stress pathways, including PKCθ (56), JNK (50), NF-κB, and the p38-MAPK pathways (3), to inhibit insulin signaling. Furthermore, a number of studies have demonstrated that depletion of lipid pools can prevent the generation of insulin resistance or restore insulin action (7, 20, 50, 53). In these studies, lipid infusions or in vitro fatty acid incubations have been performed before measurement of insulin sensitivity. In contrast to these previous studies, in the present experiment, lipid and insulin were administered concurrently from the commencement of the infusion to mimic the situation after a high-fat meal, when fatty acids and insulin are elevated. This protocol did not result in any reduction in the phosphorylation of key insulin-signaling intermediates involved in glucose metabolism. In a model similar to that employed in the present study, Ye et al. (54) reported that 6 h of lipid infusion with concurrent insulin infusion resulted in reduced Akt phosphorylation (Ser473). However, a major factor that may explain this discrepancy is the fact that the circulating lipid levels used by Ye et al. were much higher (∼4 mM). Similarly, Yu et al. (56) reported that 5 h of lipid infusion increased insulin-stimulated serine phosphorylation (1.6-fold) and reduced tyrosine phosphorylation of IRS-1 (∼30%). The observations reported in this study were from animals with circulating NEFA levels of ∼8 mM, which is well above the physiological range (36). Our findings suggest that, in contrast to studies that “preload” the animal (and muscle) with lipid and then investigate insulin action, the maintenance of a constant insulin stimulus in the presence of physiological circulating lipid levels appears to prevent the attenuation of insulin signaling.

To determine potential mechanisms involved in the onset of the insulin resistance in this acute model of hyperlipidemia and hyperinsulinemia independent of insulin signaling and, presumably, GLUT4 trafficking, we investigated a role for purported metabolic feedback mechanisms. The lipid intermediate LCACoA has been suggested to inhibit HK activity and, thereby, reduce glucose uptake (46). Accumulation of LCACoAs in association with insulin resistance has been demonstrated in high-fat-fed rats (9, 38) and 1- and 4-day glucose-infused rats (33). In similar studies, insulin resistance generated by lipid infusion in the presence of insulin was associated with an increase in LCACoA in rats (5) and humans (48). We observed a higher level of LCACoA during the lipid infusion, suggesting that the onset of insulin resistance generated in vivo by hyperlipidemia and hyperinsulinemia may be related to inhibition of HK activity by LCACoAs. Furthermore, the reduced ratio of [3H]2DG-6-phosphate to [3H]2DG suggests a reduction in HK activity with lipid infusion compared with control infusion. The ratio of [3H]2DG-6-phosphate to [3H]2DG has been used as an indirect marker of HK activity in vitro (32). However, the use of this measure as an estimate of in vivo HK activity is limited, in that it is not able to discriminate whether nonphosphorylated 2DG is intracellular, interstitial, or from the residual plasma within the tissue sample. Although a reduction in HK activity by LCACoAs is a plausible mechanism, it cannot be verified by ex vivo measurements of HK activity from lipid-infused tissues, because changes in enzyme activity are unlikely to be maintained once the allosteric regulator (e.g., LCACoA) has been diluted by homogenization. We cannot rule out a change in GLUT4 at the cell surface as a result of a mechanism not involving the canonical signaling pathways, nor can we rule out an intrinsic change in GLUT4 activity that may contribute to the decreased glucose uptake.

An alternative metabolic mechanism that may have contributed to the development of insulin resistance in this model of lipid oversupply is mitochondrial substrate competition. One of the first mechanisms proposed for skeletal muscle insulin resistance caused by oversupply of lipid was the Randle cycle (42). Simply stated, substrates (i.e., lipid and glucose) compete for oxidation in the mitochondria, and the resulting increase in certain intermediates (including acetyl-CoA and citrate) allosterically inhibits key enzymes, primarily the glycolytic enzymes HK and phosphofructokinase, and PDHC. PDHC regulates the entry of glucose carbons into the mitochondrial TCA cycle for complete oxidation to CO2. Ultimately, it is believed that, under situations of elevated fatty acid availability, glucose metabolism is reduced, and this may lead to an inhibition of glucose uptake. At the molecular level, one of the primary sites at which fatty acids attenuate glucose metabolism is thought to be PDK regulation of PDHC. PDK has been shown to phosphorylate PDHC on multiple sites to regulate its activity (31). A number of studies have implicated PDK4 as a contributor to dysfunctional glucose metabolism in models such as high-fat-fed rats (21) and humans (6), Zucker diabetic fatty rats (44), and obese humans (43). Consistent with these findings, PDK4-knockout mice are protected from chronic (18 wk) high-fat-induced glucose intolerance and hyperglycemia (24). Similar to the present study, coinfusion of lipid and insulin into rats has been reported to blunt the reduction in PDK4, but not PDK2, protein content and mRNA expression compared with saline-insulin-infused controls (34). In young lean humans, coinfusion of lipid and insulin blunted the increase in PDHC activity and elevated PDK4 mRNA compared with saline-insulin-infused controls (48). Furthermore, in these subjects, fatty acid oxidation was increased, glucose oxidation was reduced, and acylcarnitine (β-oxidation intermediate) and LCACoA content were elevated. Interestingly, there was no difference in Akt phosphorylation in the lipid-infused group in this study. Furthermore, as shown by nuclear magnetic resonance, lipid infusion reduces glucose oxidation (PDHC-to-TCA flux ratio) in rodent skeletal muscle (16, 25). In the present study, PDHC activity in the control animals was significantly increased most likely as a result of reduced PDK4 protein content. However, this reduced PDK4 content was blunted by the presence of high circulating free fatty acids. This higher level of PDK4 protein content, most likely due to increased mRNA expression, may account for the reduced activity of PDHC, which could result in decreased glucose flux through the oxidative pathways. Taken together, it is possible that acute oversupply of lipid, in the presence of high insulin, caused a reduction in PDH activity (via PDK4), which may contribute to the reduction in insulin-stimulated glucose uptake.

The precise mechanism linking increased LCACoA content and reduced PDHC activity to reduced glucose uptake remains to be completely resolved. From the observations made in the model used in the present study, one may speculate that the reduced PDHC activity would result in reduced flux through the oxidative pathway of glucose metabolism. This may result in allosteric regulation of key glycolytic enzymes by intermediates, including HK by glucose-6-phosphate as well as LCACoA. This possible reduction of HK activity leads to reduced glucose uptake, as has been suggested previously, whereby the rate-limiting step shifts from glucose transport to glucose phosphorylation (13–15, 26).

Overall, the results from the present study, which suggests a role for metabolic feedback, complement those reported in our previous glucose infusion study (22). The insulin resistance generated by glucose infusion was not associated with defects in the phosphorylation state of key insulin-signaling intermediates. Furthermore, the insulin resistance in the glucose infusion model was accompanied by reduced flux through the glycogen synthesis pathway, as well as a reduction in glucose 6-phosphate content. Therefore, we proposed a role for metabolic feedback, which resulted in a shift in the rate-limiting step from glucose transport to glucose phosphorylation preceding changes in insulin-signaling intermediates involved in glucose transport. Overall, our present and previous studies (glucose infusion) suggest that metabolic feedback may be an initial protective mechanism that limits glucose uptake into skeletal muscle in an attempt to prevent nutrient oversupply.

In summary, the present study reports that the onset of insulin resistance in skeletal muscle by lipid and insulin infusion was not accompanied by defects in the activation of multiple nodes of the insulin-signaling pathway. However, the reduced muscle glucose metabolism in rats with hyperlipidemia and hyperinsulinemia was associated with changes in metabolites (LCACoA) and an important regulatory protein (PDK4).

GRANTS

This study was funded by grants from the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) of Australia and National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grant DK-067509. A. J. Hoy is supported by an Australian Postgraduate Award from the University of New South Wales. N. Turner and M. J. Watt are supported by Career Development Awards from the NHMRC of Australia. C. R. Bruce is supported by NHMRC Peter Doherty Postdoctoral Fellowship 325645. G. J. Cooney and E. W. Kraegen are supported by the NHMRC of Australia Research Fellowships Scheme.

Acknowledgments

We thank Emma Polkinghorne and Susan Beale for technical assistance, Drs. Bronwyn Hegarty, Kyle Hoehn, and Neil Ruderman for helpful discussion, and the Biological Testing Facility at the Garvan Institute for help with animal care.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alkhateeb H, Chabowski A, Glatz JF, Luiken JF, Bonen A. Two phases of palmitate-induced insulin resistance in skeletal muscle: impaired GLUT4 translocation is followed by a reduced GLUT4 intrinsic activity. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 293: E783–E793, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Antinozzi PA, Segall L, Prentki M, McGarry JD, Newgard CB. Molecular or pharmacologic perturbation of the link between glucose and lipid metabolism is without effect on glucose-stimulated insulin secretion. A re-evaluation of the long-chain acyl-CoA hypothesis. J Biol Chem 273: 16146–16154, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhatt BA, Dube JJ, Dedousis N, Reider JA, O'Doherty RM. Diet-induced obesity and acute hyperlipidemia reduce IκBα levels in rat skeletal muscle in a fiber-type dependent manner. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 290: R233–R240, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bruce CR, Carey AL, Hawley JA, Febbraio MA. Intramuscular heat shock protein 72 and heme oxygenase-1 mRNA are reduced in patients with type 2 diabetes: evidence that insulin resistance is associated with a disturbed antioxidant defense mechanism. Diabetes 52: 2338–2345, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chalkley SM, Hettiarachchi M, Chisholm DJ, Kraegen EW. Five-hour fatty acid elevation increases muscle lipids and impairs glycogen synthesis in the rat. Metabolism 47: 1121–1126, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chokkalingam K, Jewell K, Norton L, Littlewood J, van Loon LJ, Mansell P, Macdonald IA, Tsintzas K. High-fat/low-carbohydrate diet reduces insulin-stimulated carbohydrate oxidation but stimulates nonoxidative glucose disposal in humans: an important role for skeletal muscle pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 4. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 92: 284–292, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cleasby ME, Dzamko N, Hegarty BD, Cooney GJ, Kraegen EW, Ye JM. Metformin prevents the development of acute lipid-induced insulin resistance in the rat through altered hepatic signaling mechanisms. Diabetes 53: 3258–3266, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dube JJ, Bhatt BA, Dedousis N, Bonen A, O'Doherty RM. Leptin, skeletal muscle lipids, and lipid-induced insulin resistance. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 293: R642–R650, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ellis BA, Poynten A, Lowy AJ, Furler SM, Chisholm DJ, Kraegen EW, Cooney GJ. Long-chain acyl-CoA esters as indicators of lipid metabolism and insulin sensitivity in rat and human muscle. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 279: E554–E560, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Folch J, Lees M, Sloane Stanley GH. A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipides from animal tissues. J Biol Chem 226: 497–509, 1957. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frangioudakis G, Cooney GJ. Acute elevation of circulating fatty acids impairs downstream insulin signalling in rat skeletal muscle in vivo independent of effects on stress signalling. J Endocrinol 197: 277–285, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frangioudakis G, Ye JM, Cooney GJ. Both saturated and n-6 polyunsaturated fat diets reduce phosphorylation of insulin receptor substrate-1 and protein kinase B in muscle during the initial stages of in vivo insulin stimulation. Endocrinology 146: 5596–5603, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fueger PT, Lee-Young RS, Shearer J, Bracy DP, Heikkinen S, Laakso M, Rottman JN, Wasserman DH. Phosphorylation barriers to skeletal and cardiac muscle glucose uptakes in high-fat fed mice: studies in mice with a 50% reduction of hexokinase II. Diabetes 56: 2476–2484, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Furler SM, Jenkins AB, Storlien LH, Kraegen EW. In vivo location of the rate-limiting step of hexose uptake in muscle and brain tissue of rats. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 261: E337–E347, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Furler SM, Oakes ND, Watkinson AL, Kraegen EW. A high-fat diet influences insulin-stimulated posttransport muscle glucose metabolism in rats. Metabolism 46: 1101–1106, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Griffin ME, Marcucci MJ, Cline GW, Bell K, Barucci N, Lee D, Goodyear LJ, Kraegen EW, White MF, Shulman GI. Free fatty acid-induced insulin resistance is associated with activation of protein kinase Cθ and alterations in the insulin signaling cascade. Diabetes 48: 1270–1274, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hevener A, Reichart D, Janez A, Olefsky J. Female rats do not exhibit free fatty acid-induced insulin resistance. Diabetes 51: 1907–1912, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hevener AL, Reichart D, Janez A, Olefsky J. Thiazolidinedione treatment prevents free fatty acid-induced insulin resistance in male Wistar rats. Diabetes 50: 2316–2322, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoehn KL, Hohnen-Behrens C, Cederberg A, Wu LE, Turner N, Yuasa T, Ebina Y, James DE. IRS1-independent defects define major nodes of insulin resistance. Cell Metab 7: 421–433, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holland WL, Brozinick JT, Wang LP, Hawkins ED, Sargent KM, Liu Y, Narra K, Hoehn KL, Knotts TA, Siesky A, Nelson DH, Karathanasis SK, Fontenot GK, Birnbaum MJ, Summers SA. Inhibition of ceramide synthesis ameliorates glucocorticoid-, saturated-fat-, and obesity-induced insulin resistance. Cell Metab 5: 167–179, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Holness MJ, Kraus A, Harris RA, Sugden MC. Targeted upregulation of pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase (PDK)-4 in slow-twitch skeletal muscle underlies the stable modification of the regulatory characteristics of PDK induced by high-fat feeding. Diabetes 49: 775–781, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoy AJ, Bruce CR, Cederberg A, Turner N, James DE, Cooney GJ, Kraegen EW. Glucose infusion causes insulin resistance in skeletal muscle of rats without changes in Akt and AS160 phosphorylation. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 293: E1358–E1364, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.James DE, Jenkins AB, Kraegen EW. Heterogeneity of insulin action in individual muscles in vivo: euglycemic clamp studies in rats. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 248: E567–E574, 1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jeoung NH, Harris RA. Pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase-4 deficiency lowers blood glucose and improves glucose tolerance in diet-induced obese mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 295: E46–E54, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jucker BM, Rennings AJ, Cline GW, Shulman GI. 13C and 31P NMR studies on the effects of increased plasma free fatty acids on intramuscular glucose metabolism in the awake rat. J Biol Chem 272: 10464–10473, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Katz A, Raz I, Spencer MK, Rising R, Mott DM. Hyperglycemia induces accumulation of glucose in human skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 260: R698–R703, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kerbey AL, Randle PJ, Cooper RH, Whitehouse S, Pask HT, Denton RM. Regulation of pyruvate dehydrogenase in rat heart. Mechanism of regulation of proportions of dephosphorylated and phosphorylated enzyme by oxidation of fatty acids and ketone bodies and of effects of diabetes: role of coenzyme A, acetyl-coenzyme A and reduced and oxidized nicotinamide-adenine dinucleotide. Biochem J 154: 327–348, 1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim JK, Fillmore JJ, Sunshine MJ, Albrecht B, Higashimori T, Kim DW, Liu ZX, Soos TJ, Cline GW, O'Brien WR, Littman DR, Shulman GI. PKC-θ knockout mice are protected from fat-induced insulin resistance. J Clin Invest 114: 823–827, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim JK, Kim YJ, Fillmore JJ, Chen Y, Moore I, Lee J, Yuan M, Li ZW, Karin M, Perret P, Shoelson SE, Shulman GI. Prevention of fat-induced insulin resistance by salicylate. J Clin Invest 108: 437–446, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim YB, Shulman GI, Kahn BB. Fatty acid infusion selectively impairs insulin action on Akt1 and protein kinase C λ/ζ but not on glycogen synthase kinase-3. J Biol Chem 277: 32915–32922, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kolobova E, Tuganova A, Boulatnikov I, Popov KM. Regulation of pyruvate dehydrogenase activity through phosphorylation at multiple sites. Biochem J 358: 69–77, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Konrad D, Rudich A, Bilan PJ, Patel N, Richardson C, Witters LA, Klip A. Troglitazone causes acute mitochondrial membrane depolarisation and an AMPK-mediated increase in glucose phosphorylation in muscle cells. Diabetologia 48: 954–966, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Laybutt DR, Schmitz-Peiffer C, Saha AK, Ruderman NB, Biden TJ, Kraegen EW. Muscle lipid accumulation and protein kinase C activation in the insulin-resistant chronically glucose-infused rat. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 277: E1070–E1076, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee FN, Zhang L, Zheng D, Choi WS, Youn JH. Insulin suppresses PDK-4 expression in skeletal muscle independently of plasma FFA. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 287: E69–E74, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Molero JC, Waring SG, Cooper A, Turner N, Laybutt R, Cooney GJ, James DE. Casitas b-lineage lymphoma-deficient mice are protected against high-fat diet-induced obesity and insulin resistance. Diabetes 55: 708–715, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Newsholme EA, Leech AR. Biochemistry for the Medical Sciences. Chichester: Wiley, 1983.

- 37.Nguyen MT, Favelyukis S, Nguyen AK, Reichart D, Scott PA, Jenn A, Liu-Bryan R, Glass CK, Neels JG, Olefsky JM. A subpopulation of macrophages infiltrates hypertrophic adipose tissue and is activated by free fatty acids via Toll-like receptors 2 and 4 and JNK-dependent pathways. J Biol Chem 282: 35279–35292, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Oakes ND, Bell KS, Furler SM, Camilleri S, Saha AK, Ruderman NB, Chisholm DJ, Kraegen EW. Diet-induced muscle insulin resistance in rats is ameliorated by acute dietary lipid withdrawal or a single bout of exercise: parallel relationship between insulin stimulation of glucose uptake and suppression of long-chain fatty acyl-CoA. Diabetes 46: 2022–2028, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Petersen KF, Shulman GI. Cellular mechanism of insulin resistance in skeletal muscle. J R Soc Med 95 Suppl 42: 8–13, 2002. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Powell DJ, Hajduch E, Kular G, Hundal HS. Ceramide disables 3-phosphoinositide binding to the pleckstrin homology domain of protein kinase B (PKB)/Akt by a PKCζ-dependent mechanism. Mol Cell Biol 23: 7794–7808, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Preiss J, Loomis CR, Bishop WR, Stein R, Niedel JE, Bell RM. Quantitative measurement of sn-1,2-diacylglycerols present in platelets, hepatocytes, and ras- and sis-transformed normal rat kidney cells. J Biol Chem 261: 8597–8600, 1986. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Randle PJ, Garland PB, Hales CN, Newsholme EA. The glucose fatty-acid cycle. Its role in insulin sensitivity and the metabolic disturbances of diabetes mellitus. Lancet 1: 785–789, 1963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rosa G, Di Rocco P, Manco M, Greco AV, Castagneto M, Vidal H, Mingrone G. Reduced PDK4 expression associates with increased insulin sensitivity in postobese patients. Obes Res 11: 176–182, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schummer CM, Werner U, Tennagels N, Schmoll D, Haschke G, Juretschke HP, Patel MS, Gerl M, Kramer W, Herling AW. Dysregulated pyruvate dehydrogenase complex in Zucker diabetic fatty rats. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 294: E88–E96, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stratford S, Hoehn KL, Liu F, Summers SA. Regulation of insulin action by ceramide: dual mechanisms linking ceramide accumulation to the inhibition of Akt/protein kinase B. J Biol Chem 279: 36608–36615, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thompson AL, Cooney GJ. Acyl-CoA inhibition of hexokinase in rat and human skeletal muscle is a potential mechanism of lipid-induced insulin resistance. Diabetes 49: 1761–1765, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tilg H, Moschen AR. Inflammatory mechanisms in the regulation of insulin resistance. Mol Med 14: 222–231, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tsintzas K, Chokkalingam K, Jewell K, Norton L, Macdonald IA, Constantin-Teodosiu D. Elevated free fatty acids attenuate the insulin-induced suppression of PDK4 gene expression in human skeletal muscle: potential role of intramuscular long-chain acyl-coenzyme A. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 92: 3967–3972, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vettor R, Fabris R, Serra R, Lombardi AM, Tonello C, Granzotto M, Marzolo MO, Carruba MO, Ricquier D, Federspil G, Nisoli E. Changes in FAT/CD36, UCP2, UCP3 and GLUT4 gene expression during lipid infusion in rat skeletal and heart muscle. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 26: 838–847, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Watt MJ, Hevener A, Lancaster GI, Febbraio MA. Ciliary neurotrophic factor prevents acute lipid-induced insulin resistance by attenuating ceramide accumulation and phosphorylation of c-Jun N-terminal kinase in peripheral tissues. Endocrinology 147: 2077–2085, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wellen KE, Hotamisligil GS. Inflammation, stress, diabetes. J Clin Invest 115: 1111–1119, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yang G, Li L, Fang C, Zhang L, Li Q, Tang Y, Boden G. Effects of free fatty acids on plasma resistin and insulin resistance in awake rats. Metabolism 54: 1142–1146, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ye JM, Dzamko N, Cleasby ME, Hegarty BD, Furler SM, Cooney GJ, Kraegen EW. Direct demonstration of lipid sequestration as a mechanism by which rosiglitazone prevents fatty-acid-induced insulin resistance in the rat: comparison with metformin. Diabetologia 47: 1306–1313, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ye JM, Frangioudakis G, Iglesias MA, Furler SM, Ellis B, Dzamko N, Cooney GJ, Kraegen EW. Prior thiazolidinedione treatment preserves insulin sensitivity in normal rats during acute fatty acid elevation: role of the liver. Endocrinology 143: 4527–4535, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Youngren JF, Paik J, Barnard RJ. Impaired insulin-receptor autophosphorylation is an early defect in fat-fed, insulin-resistant rats. J Appl Physiol 91: 2240–2247, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yu C, Chen Y, Cline GW, Zhang D, Zong H, Wang Y, Bergeron R, Kim JK, Cushman SW, Cooney GJ, Atcheson B, White MF, Kraegen EW, Shulman GI. Mechanism by which fatty acids inhibit insulin activation of insulin receptor substrate-1 (IRS-1)-associated phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase activity in muscle. J Biol Chem 277: 50230–50236, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhande R, Mitchell JJ, Wu J, Sun XJ. Molecular mechanism of insulin-induced degradation of insulin receptor substrate 1. Mol Cell Biol 22: 1016–1026, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zierath JR, Houseknecht KL, Gnudi L, Kahn BB. High-fat feeding impairs insulin-stimulated GLUT4 recruitment via an early insulin-signaling defect. Diabetes 46: 215–223, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]