Abstract

The discovery of recurrent gene fusions in a majority of prostate cancers has important clinical and biological implications in the study of common epithelial tumors. Gene fusion and chromosomal rearrangements were previously thought to be the primary oncogenic mechanism of hematological malignancies and sarcomas. The prostate cancer gene fusions that have been identified thus far are characterized by 5’ genomic regulatory elements, most commonly controlled by androgen, fused to members of the ETS family of transcription factors, leading to the over-expression of oncogenic transcription factors. ETS gene fusions likely define a distinct class of prostate cancer which may have a bearing on diagnosis, prognosis and rational therapeutic targeting.

Introduction

Prostate cancer is one of the most prevalent malignancies affecting men worldwide, and is the most frequent cancer among American men with an estimated incidence of approximately 220,000 (29% of all cancers in men) and a mortality estimated to be over 27,000 (9% of all male cancer deaths) in 20071. An array of treatment modalities are available, including active surveillance, prostatectomy, radiation therapy and androgen ablation therapy, all influenced by the use of serum prostate specific antigen (PSA) levels2. Even as clinically localized prostate cancer has become highly curable the overall death toll remains high due to recurrence of “cured” cases and progression to hormone refractory metastatic disease, which remains uncurable3. Conversely, nonspecific PSA tests result in a large number of false positives for prostate cancer, leading to a faux-cancer burden and repeated biopsies4. More specific diagnostic modalities, prognostic indicators of progression and a better understanding of prostate cancer biology for treatment of hormone refractory disease are high priorities in prostate cancer research.

Approximately two years ago, our group identified recurrent genomic rearrangements in prostate cancer resulting in the fusion of the 5’ untranslated end of TMPRSS2 (a prostate specific, androgen responsive gene) to ETS family genes (oncogenic transcription factors)5. The original findings have been rapidly corroborated by several independent groups worldwide and now the focus is on the functional and clinical correlates of prostate cancer in the context of the gene fusions. Emerging experimental evidence suggests that these fusions are key molecular entities driving the development and progression of a unique class of prostate cancers, providing potential avenues for targeted therapy, similar to the BCR-ABL1 gene fusion in chronic myeloid leukemia (CML).

Gene fusions resulting from chromosomal rearrangements represent the most prevalent form of genetic alterations known in cancers6 and, as exemplified by the archetype gene fusion BCR-AbL1 in CML7, 8 they can serve as ideal diagnostic markers9–11, provide insight into tumor biology12, and most importantly serve as specific therapeutic targets13, 14. Intriguingly, while numerous gene fusions have been described in rare hematological malignancies and even rarer bone and soft tissue sarcomas15, they are much rarer among epithelial cancers. Gene fusions described among epithelial cancers so far have included RET-NTRK1 fusions in papillary thyroid carcinoma, PAX8-PPARG in follicular thyroid carcinoma, MECT1-MAML2 in mucoepidermoid carcinoma, the TFE3-TFEB in kidney carcinomas, and BRD4-NUT in midline carcinomas etc (reviewed16). Remarkably, recurrent gene fusions have not previously been detected in the most prevalent carcinomas including prostate, breast (with the exception of rare, secretory breast cancers), lung, gastrointestinal and gynecologic tumors17, despite compelling arguments that predict their occurence15, 18, 19. The absence of gene fusions in common solid tumors has been attributed to the technical difficulties associated with their cytogenetic analysis. Also, epithelial cancers are thought to be clonally heterogeneous, with causal chromosomal aberrations co-habiting the tissues with clinically irrelevant ones. While cytogenetic analyses help identify ‘physical’ genomic aberrations, recurrent gene fusions in prostate cancer were identified based on gene expression data, bypassing the technical limitations of cytogenetics in solid cancers. This strategy led to the identification of recurrent gene fusions in common solid cancers, close to 50 years after the discovery of Philadelphia chromosome in 1960s.

In this review, we appraise recent progress in the characterization of recurrent gene fusions in prostate cancer. We will highlight the clinical implications of new discoveries, emerging controversies and challenges, as well as future research directions. In addition to serving as potential diagnostic/prognostic markers and therapeutic candidates for a unique class of prostate cancer, the discovery of recurrent rearrangements in prostate cancer affirms a more generalized role for similar chromosomal aberrations in other common epithelial cancers.

Discovering gene fusions with bioinformatics

Cancers are, for the most part, phenotypically and molecularly heterogeneous entities. Thus, characterization of distinct molecular classes with an overarching influence of a single gene or two is clinically and therapeutically significant. For example, in one-quarter to one-third of all breast cancer cases, amplification and over-expression of the oncogene HER2 defines an aggressive class that is more likely to metastasize, develop hormone resistance, and respond significantly to HER2 targeted therapy. Likewise, Philadelphia chromosome positive chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) typifies 10% of all leukemia cases, where the underlying aberration is a BCR-ABL1 gene fusion that becomes the focal point of diagnosis, classification, prognostication, therapy, as well as follow up and recurrence monitoring (BOX 1). Other well-defined cancer classes include less than 5% of all breast cancers harboring BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations20, 6% of colon cancers with microsatellite instability or germline mutations characterizing specific clinical classes such as hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC), or familial adenomatus polyposis (FAP)21, 22 and 10% of non small cell lung cancers harboring sensitizing mutations in EGFR that respond to the EGFR targeting drug gefitinib23.

BOX 1 Gene fusions and Cancer

Recurrent gene fusions in cancer: Gene fusions represent the most common class of somatic mutations associated with cancer6. These may involve the regulatory elements of one gene (often tissue specific) aberrantly apposed to a proto-oncogene, for example, immunoglobulin and T cell receptor regulatory regions fused to MYC oncogene in B and T cell malignancies, respectively112. Alternatively, coding regions of two genes get juxtaposed, resulting in a chimeric protein with a new or altered activity; for example the BCR-ABL1 gene fusion in chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML)12, 112 and a subset of acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL)113, 114.

-

BCR-ABL1 Paradigm: BCR-ABL1 gene fusion on the Philadelphia chromosome (aberrant Chromosome 22) discovered by Nowell and Hungerford in 196110, 115 results from a translocation of the proto-oncogene c-abl1 from chromosome 9 to the bcr gene on chromosome 22; the fusion gene encoding a fusion protein BCR-ABL1, in CML11, 12.

BCR-ABL1 is a diagnostic marker for CML: Detection of BCR-ABL1 fusion transcript in peripheral blood is used to confirm CML diagnosis, monitor cytogenetic remission and residual disease116.

BCR-ABL1 fusion gene has many molecular variants: A wide variety of fusion variants of BCR-ABL1 are known, as a result of alternative breakpoint regions in BCR and in ABL1. Depending on the location of breakpoint regions, BCR-ABL1 protein may be 210 kDa (MBcr), 190 kDa (mBcr) or µBcr (230kDa). Different fusions have been associated with different disease phenotypes52.

BCR-ABL1 is pathognomonic for CML: The BCR-ABL1 fusion protein has tyrosine kinase activity117 which is essential for initiation, maintenance and progression of CML7. Transgenic BCR-ABL1 mice display CML-like myeloproliferative disorders118–120. Transgenic BCR-ABL1 expression in hematopoietic stem cells induces chronic phase CML in mice118, 121.

BCR-ABL1 is a specific therapeutic target: Imatinib, a small molecule inhibitor of ABL1 tyrosine kinase activity is used as the standard treatment for chronic phase CML122–124.

Gene Fusions in Carcinoma- The missing Link: While leukemias/ lymphomas and bone/soft tissue sarcomas, which together represent only 10% of all human cancers account for more than 80% of all known gene fusions, common epithelial, cancers which account for 80% of cancer related deaths, account for only about 10% of recurrent gene fusions15, 19. This paradox has been challenged by the recent discoveries of gene fusions in prostate and lung cancers.

We initiated a systematic identification of candidate oncogenes activated by chromosomal rearrangements or high level copy number changes based on gene expression signatures using an unconventional analytical approach. Cancer gene expression data sets were queried for genes that are highly over-expressed in a subset of samples rather than focusing on those that are widely shared in all samples5. To identify such “outlier” genes, we applied a data transformation algorithm, cancer outlier profile analysis (COPA), to all of the 132 gene-expression data sets (comprising >10,000 microarray experiments from various cancers) available in Oncomine (www.oncomine.org24–27), our gene expression compendium (FIG. 1). COPA transformation effectively compresses typical biomarker profiles characterized by a general overexpression of genes in all cancer samples, while accentuating ‘outlier gene’ profiles, characterized by general low expression with marked overexpression in a fraction of the samples. Prioritized outlier genes identified by our systematic approach included several well-known cancer genes involved in recurrent chromosomal aberrations or high level copy number changes associated with their specific cancers. Surprisingly, two genes known to be involved in gene fusions in Ewing’s sarcoma28, 29, namely ERG (ETS-related gene) and ETV1 (ETS variant gene 1), were scored as high ranking outliers in several independent prostate-cancer profiling studies. Akin to Ewing’s sarcoma, where Ewing sarcoma breakpoint region 1 (EWSR1)–ERG and EWSR1–ETV1 fusion genes are mutually exclusive in different cases28, ERG and ETV1 overexpression were mutually exclusive in prostate cancer. This suggested that elevated expression of ERG/ETV1 may be a key molecular event in a subset of prostate cancers.

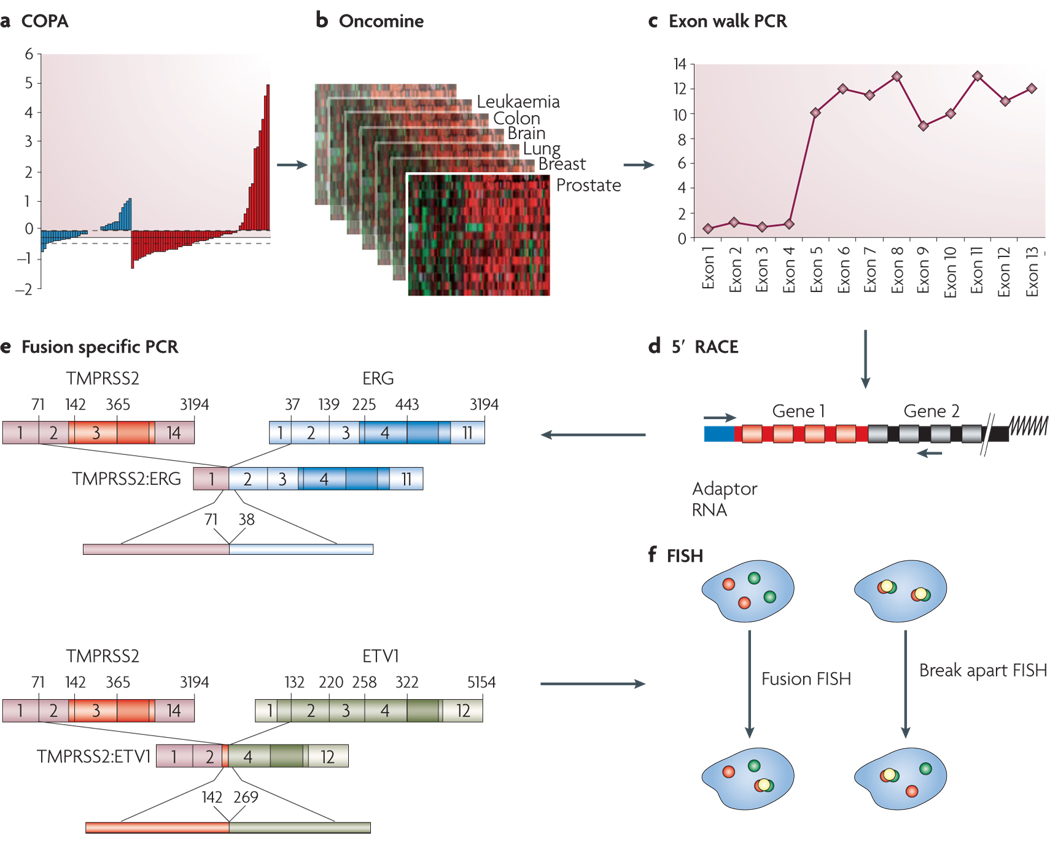

FIGURE 1. Cytological and Molecular Techniques used in Gene Fusion Studies.

A. Cancer Outlier Profile Analysis (COPA) (described in the main text) was applied to microarray data available Oncomine (B.), and the top “outlier” genes formed our primary candidates to test for potential genomic rearrangements using cytogenetic and molecular techniques. C. The downstream workflow begins with quantitative real time PCR specific to exons from all parts of the gene (Exon-walk PCR), whereby a sharply divergent expression pattern from different parts of the gene suggests that a part of the gene may be split/ rearranged. D. Fusion partners of candidate split genes are identified by cloning the beginning and end of the candidate transcript using rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE). 5’ RACE is used to identify the 5’ fusion partner, and involves ligating an RNA adaptor sequence to the test RNA and carrying out RT-PCR using RNA adaptor specific forward primer and candidate gene specific reverse primer (located close to the split exon). The RACE PCR products are cloned and sequenced to confirm the identity of fusion genes. E. Fusion specific RT-PCR is used to confirm the presence of fusion transcript. F. Finally, the chromosomal rearrangements involved in the gene fusion are characterized by fluorescence in-situ hybridization (FISH) on interphase nuclei. FISH analysis involves hybridization of fluorescently labeled DNA probes corresponding to the candidate target sequences. Since it allows visualization of specific regions of the chromosome based on DNA sequence, it is the method of choice to investigate the genomic rearrangements like insertion, deletion, and translocation that can split or fuse genes.

In the ‘split probe’ or ‘break apart’ assay strategy, two fluorescent probes (for example, green and red) are hybridized to sequences less than 1Mb apart, so that in normal interphase nucleus they appear co-localized. If a genetic rearrangement involves the region spanned by the two probes, the signals are separated and appear distinct (translocation), or a single color signal is seen and the other signal is lost (deletion). In the alternative ‘fusion probe’ strategy, two probes are localized far apart on the chromosome- or on two separate chromosomes. Two pairs of separate signals are seen in the normal diploid nucleus and in the event of a chromosomal rearrangement leading to gene fusion, the two signals are co-localized. Both these techniques have been used in the gene fusion studies, often in combination.

Analysis of prostate cancer samples that overexpress ERG and ETV1 (“outliers”) using exon-walking quantitative PCR revealed overexpression of only their 3’ regions, suggestive of a genetic rearrangement (FIG. 1). This lead us to characterize the 5’ ends of ERG and ETV1 transcripts using a 5’ RNA-ligase-mediated rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE) methodology (FIG 1). We discovered that the 5’ ends of ERG and ETV1 are replaced with the 5’ untranslated region of a prostate-specific, androgen responsive, transmembrane serine protease gene (TMPRSS2) (21q22.2) in the outlier cases5. Fusion transcripts were confirmed by quantitative PCR, and rearrangments at the genomic loci were then assessed in multiple samples by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) on tissue microarrays (FIG. 1). FISH demonstrated that a majority of prostate cancer samples harbor these aberrations. It bears noting that the TMPRSS2-ETS fusions are analogous to the IgH-myc30, 31 and IgH-bcl232 gene fusions in lymphomas. In these cases, no fusion protein is generated but there is massive overexpression of an oncogenic factor under the control of a subverted promoter element12.

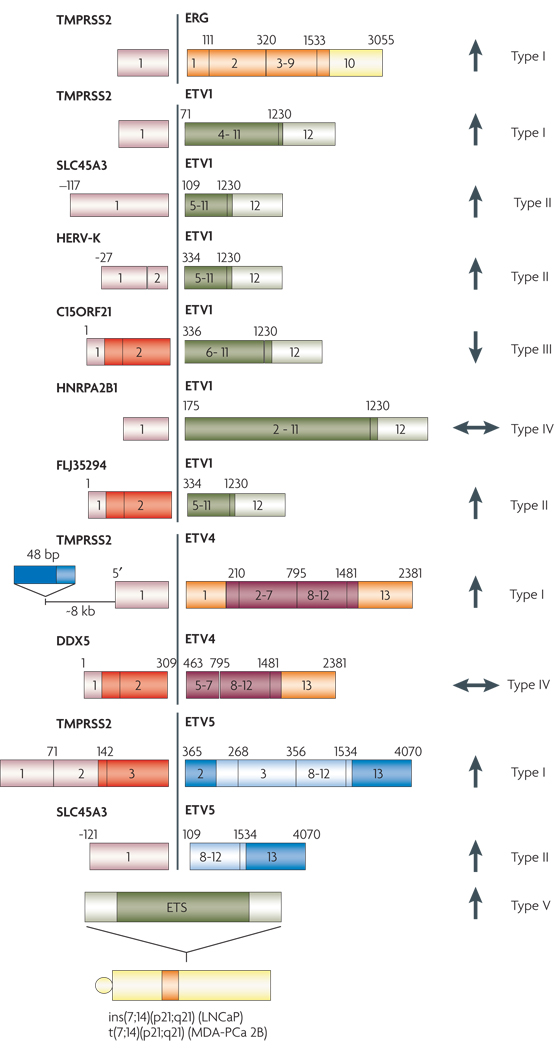

Interestingly, while almost all ERG overexpressing tumors were found to harbor TMPRSS2:ERG fusion, subsequent investigations identified fewer TMPRSS2:ETV1 cases than expected based on the frequency of ETV1 outlier expression. This paradox was investigated with the use of 5’ RACE (FIG. 1) on ETV1 outlier samples, leading to the characterization of multiple upstream fusion partners of ETV1. These differed in their prostate specificity and androgen responsiveness, presenting a novel level of complexity in the molecular biology of prostate cancers33. The upstream partners of ETV1 identified so far include: a prostate specific androgen-induced gene (SLC45A3) and an endogenous retroviral element (HERV-K_22q11.23) that are functionally analogous to TMPRSS2; a prostate-specific, but androgen-repressed gene (C15orf21) and a strongly expressed housekeeping gene (HNRPA2B1) with no prostate specificity or androgen responsiveness33. Different rearrangements were characterized in two prostate cancer cell lines with high level ETV1 expression; LNCaP and MDA-PCa 2B cells were found to have the ETV1 gene at 7p21 rearranged to a prostate specific region at chromosome 14q13.3–14q21.1. Recently,

Subsequently, we have characterized prostate cancer samples with COPA defined outlier expression of other ETS family genes and discovered more gene fusions such as TMPRSS2:ETV434, TMPRSS2:ETV5 and SLC45A3-ETV535. Most recently, Hermans et al. identified the prostate specific, androgen induced genes KLK2 and CANT1 as additional 5’ partners of ETV4 (cite pubmed ID: 18451133). The COPA methodology of identifying gene expression outliers is available at www.oncomine.org. This algorithm has been implemented in an R package (termed COPA package; available at http://www.bioconductor.org)36 and been integrated into Significance Analysis of Microarrays (SAM) methodology by Tibshirani et al. (http://www-stat.stanford.edu/∼tibs/SAM)37. Recently, COPA has been used to identify genomic alterations associated with the NFκB pathway in multiple myeloma38, supporting the applicability of this methodology for identifying candidates for chromosomal aberration. This gene expression based methodology effectively overcomes the barriers to cytogenetic identification of recurrent chromosomal aberrations associated with solid cancers.

Diversity and frequency of gene fusions in prostate cancer

TMPRSS2:ERG gene fusions have been reported in approximately 50% of over 1500 clinically localized prostate cancer samples analyzed in over two dozen reports published thus far (TABLE 1), reflecting the prevalence of such fusions in PSA screened patient cohorts, with a lower frequency (15%) reported for a population-based cohort (cite Swedish watchful paper). Overall, early- and mid-stage localized prostate cancers and hormone refractory metastatic cancers display TMPRSS2:ERG rearrangements in 50% or more cases, whereas high-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (HGPIN) appear to have a lower frequency of the gene fusions (TABLE 1)39–43. It bears noting that gene fusions involving other ETS family members, primarily ETV1 but also including ETV4 and ETV5, together likely constitute less than 10% of prostate cancer samples.

TABLE 1.

Recurrent Gene Fusions in Prostate Cancer

| Gene Fusion | Sample | Frequency (%) | Fusion Type | Assay | Study |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TMPRSS2:ERG | PCA | 16/29 (55%) | T1:E4 | qRT-PCR/FISH | Tomlins, et al 20051 |

| TMPRSS2:ETV1 | PCA | 7/29 (24%) | T1:E4 | ||

| TMPRSS2:ERG | PCA, biopsy | 14/18 (77%) | T1:E4, T1:E2, T4/5:E4/5 | Nested RT-PCR | Soller, et al 20062 |

| TMPRSS2:ETV4 | PCA, overexpressing ETS family genes | 2/98 (2%) | RACE/qRT-PCR/FISH | Tomlins, et al 20063 | |

| TMPRSS2:ERG | PCA, Gleason score 6–9 | 6/15 (40%) | T1:E5, T2:E5, T1:E4 | RT-PCR/FISH | Yoshimoto, et al 20064 |

| TMPRSS2:ERG | PCA | 58/118 (49%) | FISH/qRT-PCR | Perner, et al 20065 | |

| TMPRSS2:ERG | PCA | 7/18 (41%) | |||

| TMPRSS2:ERG | PCA | 35/59 (59%) | 8 different types of fusions | RT-PCR | Wang, et al 20066 |

| TMPRSS2:ERG | BPH | 0/20 (_) | |||

| TMPRSS2:ERG | PCA, T1cN0M0/T2N0M0 | 17/34 (50%) | T1:E4 | RT-PCR/qRT-PCR | Cerviera, et al 20067 |

| TMPRSS2:ERG | HGPIN | 4/19 (21%) | |||

| TMPRSS2:ERG | BPH | 0/13 (_) | |||

| TMPRSS2:ERG | Normal Prostate | 0/11 (_) | |||

| TMPRSS2:ERG | PCA | 19/26 (73%) | T1:E4, T1:E5. T1:E2, T1:E3, etc.-total 14 types | RT-PCR/Nested-PCR | Clark, et al 20078 |

| TMPRSS2:ERG | Normal adjacent | 8/17 (47%) | |||

| TMPRSS2:ERG | BPH | 2/31 (6%) | |||

| TMPRSS2:ERG | Non-Prostate Normal | 0/20 (_) | |||

| TMPRSS2:ERG | Post:DRE Urine | 8/19 (42%) | T1:E4 (5) T1:32 (1) | qRT-PCR/FISH | Laxman, et al 20069 |

| TMPRSS2:ERG | PCA, Advanced | 7/19 (37%) | T2:E6;E4 (1) | RT-PCR/array cGH | Iljin, et al 200610 |

| TMPRSS2:ETV4 | PCA, Advanced | 2/18 (11%) | T1/2:E4 | ||

| TMPRSS2:ERG TMPRSS2:ETV1 |

PCA, Xenografts PCA, Xenografts |

5/11 (45%) 1/11 (9%) |

T1/2:E5 | FISH/qPCR | Hermans, et al 200611 |

| TMPRSS2:ERG | PCA, Gleason score 7 | 11/26 (42%) | RT-PCR, Sequencing | Nami, et al 200712 | |

| TMPRSS2:ERG | PCA, T1a:b, Ns, M0′, Orebro Watchful Waiting Cohort | 17/111 (15%) | FISH/qRT-PCR | Demichelis, et al 200713 | |

| TMPRSS2:ERG | PCA | 36/101 (36%) | T2:E4 and T1:E4 | FISH/RT-PCR, Sequencing | Rajput, et al 200714 |

| TMPRSS2:ERG | BHP | 0/5 (_) | |||

| TMPRSS2:ERG | PCA | 30/56 (54%) | FISH | Mehra, et al 200715 | |

| TMPRSS2:ETV1 | PCA | 1/53 (2%) | |||

| TMPRSS2:ETV4 | PCA | 1/58 (2%) | |||

| TMPRSS2:ERG | PCA | 44/63 (70%) | T2:E4 & T2:E4* | RACE/qRT-PCR/FISH | Lapointe, et al 200716 |

| TMPRSS2:ERG | PCA | 120/253 (47%) | FISH | Mosquera, et al 200717 | |

| TMPRSS2:ERG | PCA | 18/50 (36%) | RT-PCR | Winnes, et al 200718 | |

| TMPRSS2:ERG | PCA | 115/237 (48%) | FISH | Perner, et al 200719 | |

| TMPRSS2:ERG | Metastases, hormone naive | 10/34 (29%) | |||

| TMPRSS2:ERG | Metastases, hormone refractory | 3/9 (33%) | |||

| TMPRSS2:ERG | HGPIN | 5/26 (19%) | |||

| TMPRSS2:ERG | BPH | 0/15 (_) | |||

| TMPRSS2:ERG | PIA | 0/38 (_) | |||

| TMPRSS2:ERG | Benign Prostate samples | 0/47 (_) | |||

| TMPRSS2:ERG | PCA | 25/52 (48%) | RT-PCR/FISH | Tu, et al 200720 | |

| TMPRSS2:ERG | PCA, Transurethral resection | 134/445 (30%) | FISH | Attard, et al 200721 | |

| HERV_K_22Q11.23: ETV1 | PCA and Metastases | - | T1:T4, T2:T4 | qRT-PCR/FISH | Tomlins, et al 200722 |

| SLC45A3:ETV1 | PCA and Metastases | - | |||

| C15ORF21:ETV1 | PCA and Metastases | - | |||

| HNRPA2B1:ETV1 | PCA and Metastases | - | |||

| TMPRSS2:ERG | Prostate Biopsies and Post-DRE urine | 17/29 (59%) | RT-PCR | Hessels, et al 200723 | |

| TMPRSS2:ERG | PCA | 81/165 (49%) | RT-PCR, Sequencing | Nam, et al 200724 | |

| TMPRSS2:ERG | PCA, Multifocal | 17/32 (53%) | FISH | Barry, et al 200725 |

Considering the annual incidence (220,000 cases) of prostate cancer in the United States alone, the number of patients with ETS gene fusions likely surpasses the number of patients with BCR-ABL1 (∼7000 patients per year) and several bone and soft tissue sarcomas with individual incidences ranging from a few dozen to a few hundred per year 1, 15.

While high throughput FISH assays using tissue microarray sections have been useful in screening large numbers of samples to determine the prevalence of recurrent gene fusions in prostate cancer, the characterization of fusion transcripts by RACE and RT-PCR has revealed a spectrum of fusion transcript variants (FIG. 2; TABLE 1). The most common variants involve TMPRSS2 exon 1 or 2 fused to ERG exon 2, 3, 4 or 5(ref 5, 39, 40, 44–49). Less frequent combinations include TMPRSS2 exon 4 or 5 fused to ERG exon 4 or 5(ref 48), and in one case, TMPRSS2 exon 2 was found fused to inverted ERG exon 6–445. These variant fusion transcripts most likely represent alternative splicing variants50, and unpublished work from other groups suggests that there are distinct phenotypic effects produced by different isoforms. Lapointe et al. have described two isoforms of TMPRSS2 involved in fusion with ERG: the reference sequence TMPRSS2 (exon 1), involved in about 50% of the fusions, and an alternative TMPRSS2 isoform, mapping 4 kb upstream of the reference sequence, found in 10% of the fusions; approximately 44% of the samples reportedly expressing both the variants46. Early efforts to chart the molecular variants have lead one group to employ nested RT-PCR to characterize as many as 14 fusion variants40 and another 850, with many common variants identified. While the clinical significance of these variants is undefined, some TMPRSS2:ERG fusion variants have been associated with prognostic outcomes. For example, Wang et al50 observed that TMPRSS2 exon 2 fused with ERG exon 4 is associated with aggressive disease, and the fusion transcript with the first in-frame ATG codon present in ERG exon 3 was associated with seminal vesicle invasion (which is correlated with poor outcome). Further, other isoforms that highly express fusion mRNAs were also associated with early prostate-specific antigen recurrence.

FIGURE 2. Anatomy of Gene fusions in Prostate Cancer.

A cartoon representation of the gene fusions characterized in prostate cancers so far. The 5’ fusion partners are depicted on the left side and corresponding 3’ partners on the right. Light colors at the ends of the genes depict untranslated exons. The dark colored boxes depict coding exons. The numbers on the boxes identify the base positions of the exons. The arrows represent androgen responsiveness of the fusion genes, arrows pointing up (red) signify androgen mediated upregulation; arrows pointing down (green) represent androgen mediated down regulation of the corresponding gene; the horizontal arrows (blue) represent absence of androgen action on the fusion genes’ expression. TMPRSS2-ETS gene fusions have been grouped as Type I; other gene fusions which are androgen inducible have been grouped as Type II, androgen repressed fusion genes make up Type III, Androgen insensitive fusion genes, Type IV, and lastly, the novel situation in prostate cancer cell lines, with ETS genes rearranged to an androgen sensitive location (without the generation of classical gene fusions) has been classified as Type V.

BCR-ABL1 has well characterized breakpoint clusters in both the genes that determine the nature of fusion genes (BOX 1). With respect to TMPRSS2:ERG, Yoshimoto et al point to a likely involvement of regions of microhomology (about 300 bp stretches sharing up to 90% homology) in the introns adjacent to fusion exons49. Through a systematic mapping of genomic rearrangements in and around the TMPRSS2 and ERG loci using SNP arrays, Liu et al correlated the presence of consensus sequences resembling human Alu repeats within the introns of the two genes with the TMPRSS2:ERG gene fusion51.

Most of the fusion genes and transcripts characterized thus far have the protein coding region derived largely from the ETS family gene and in all fusion variants, the ETS domain appears to be retained. Recently, we identified one ‘fusion protein’, with the first three coding exons (103 amino acids) of an RNA helicase DDX5, fused in frame to ETV4 exon 5, in one prostate cancer with ETV4 outlier expression (manuscript submitted). However the functional significance of residues from DDX5 remains unclear.

Clinical, Histological, and Molecular Features

Similar to BCR-ABL1 positive leukemias7, 52, colon cancers with microsatellite instability53, 54, or breast cancers with BRCA mutations55, 56, ETS gene fusions in prostate cancer are associated with specific morphological features and prognoses, as well as specific molecular signatures. A particularly interesting picture is emerging in multi-focal prostate cancers, where different tumor foci in a patient sample have different gene fusion status; however different sites of metastatic prostate cancer from the same patient are uniformly fusion positive or negative.

Association with Morphology

Mosquera et al identified five morphological features- blue-tinged mucin, cribriform growth pattern, macronucleoli, intraductal tumour spread, and signet-ring cell- to be significantly associated with prostate tumor samples with TMPRSS2:ERG fusion57. Samples which harbored three or more of these features were almost always (93%) fusion positive and only 24% of fusion positive samples did not display any of these morphological features57. Tu et al. also noted a significantly higher frequency of TMPRSS2:ETS gene fusions in mucin-positive carcinomas than mucin-negative tumors58. Larger studies may help establish the phenotypic associations of the gene fusions (and their variants). A molecular connection between the gene-fusions and specific morphological features will also require follow up studies.

Prognostic Association

TMPRSS2:ERG has been frequently but not unequivocally associated with more aggressive prostate cancers and a poorer prognosis. TMPRSS2 gene rearrangement has been variously associated with high pathologic stage59 and higher rate of recurrence60 in independent cohorts of surgically treated localized prostate cancer cases and the presence of gene fusion has been scored as the single most important prognostic factor 60, 61. In a FISH based analysis of 445 cancer cases, not having an ERG fusion was found to be a good prognostic factor (90% survival at 8 years) compared to cancers with duplication of TMPRSS2:ERG in combination with deletion of 5'-ERG (2+Edel) that exhibited very poor cause-specific survival (25% survival at 8 years)62. This novel category of ‘2+Edel’ status was found to be an independent of other prognostic factors including Gleason score and serum levels of prostate-specific antigen. In the assessment of gene fusion status in a population-based “watchful waiting” cohort of men with localized prostate cancer- mostly comprising of good or uncertain prognoses, tumors from just 15% of the patients were found to harbor TMPRSS2:ERG fusion. Remarkably, this fusion positive subset was significantly associated with prostate cancer specific death63. In another study involving primary prostate cancers and hormone-naïve lymph node metastases, a significant association was observed between TMPRSS2:ERG rearranged tumors and higher tumor stage, as well as the presence of metastatic disease involving pelvic lymph nodes41. Similarly, Rajput et al observed more frequent TMPRSS2:ERG fusions in moderate to poorly differentiated tumors as compared to well-differentiated tumors47. In a cohort of patients treated for clinically localized prostate cancer Nam et al observed that TMPRSS2:ERG fusion positive subgroup of patients had a significantly higher risk of recurrence (58.4% at 5 years) than fusion negative patients (8.1%)61. On the other hand many studies have reported an absence of such clinical correlation between the fusions and prognosis. In a report preceding gene fusions discovery, Petrovics et al had associated ERG overexpressing prostate cancers with several positive prognosticators such as longer recurrence-free survival, well and moderately differentiated stages, lower pathological stage, and negative surgical margins64. Similar observations were recently made by Winnes et al with respect to gene fusion positive prostate cancers where they report “a clear tendency” for fusion positive tumors to be associated with lower Gleason grade and better survival than fusion negative tumors65. Yoshimoto et al found no correlation between clinical outcome and presence of gene fusions49 and Lapointe et al found no significant association between presence of a TMPRSS2:ERG fusion and tumor stage, Gleason grade or recurrence-free survival46. It may be noted that many of the negative reports have small sample sizes: Yoshimoto et al, 15 cases, Winnes et al, 50, Liu et al, 41, Lapointe et al, 63, as compared to the reports of an association: Rajput 196, Perner 136, Nami 26, Nam 165, Mehra 96, Demischelis 111, Attard 445, (TABLE 2). Clearly, more studies, with larger patient cohorts would help resolve specific prognostic association of the gene fusions.

Table 2.

Prognostic Associations of TMPRSS2:ERG fusion

| Study reference | ETS gene Status/ Assay | Patient Cohort | Prognostic association | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Mehra, R. et al. (2007)59 | TMPRSS2/ERG rearrangement Break-apart FISH |

PCa cases, Surgically treated (n=96) | High pathologic stage |

| 2 | Nam, R.K. et al. (2007)66 | TMPRSS2:ERG fusion RT-PCR and DNA sequencing |

PCa cases, Surgically treated (n=26), Gleason score 7 | Higher rate of recurrence Single most important prognostic factor |

| 3 | Nam, R.K. et al. (2007)61 | TMPRSS2:ERG fusion RT-PCR and DNA sequencing |

PCa cases, Surgically treated (n=165) | Higher risk of recurrence (58.4% at 5 years). Strong prognostic factor independent of grade, stage and PSA level. |

| 4 | Attard, G. et al. (2007)62 | ERG rearrangement Break-apart FISH |

PCa cases, transurethral resection specimens, (TMAs, Cohort of conservatively managed patients (no hormone treatment) (n=445) | Very poor cause-specific survival (25% Survival at 8 years) (2+Edel)* compared against ERG rearrangement negative cases (90% survival at 8 years) |

| 5 | Demichelis, F. et al. (2007)63 | TMPRSS2:ERG rearrangement Multicolored fusion FISH |

PCa cases, Population based watchful waiting cohort (n=111) | Prostate cancer specific death |

| 6 | Perner, S. et al. (2006)41 | TMPRSS2:ERG rearrangement Dual color break-apart FISH |

PCa cases, hormone-naïve and hormone-refractory lymph node metastases (n=136) | Higher tumor stage, presence of metastatic disease involving pelvic lymph nodes |

| 7 | Rajput, A.B. et al. (2007)47 | TMPRSS2:ERG fusion FISH TMPRSS2 Break-apart FISH |

PCa cases, Surgically treated Tissue microarrays (TMAs) (n=196) | Moderate to poorly differentiated tumors |

| 8 | Petrovics, G. et al. (2005)64 | ERG overexpression Microarray, Real-time PCR |

PCa cases, Laser Capture microdissected epithelial cells ERG overexpressing tumors | Longer recurrence-free survival, well and moderately differentiated stages, lower pathological stage, and negative surgical margins |

| 9 | Winnes, M., et al. (2007)65 | TMPRSS2:ERG fusion RT-PCR and DNA sequencing |

PCa cases, transrectal ultrasound (TRUS) guided needle biopsies (n=50) | Lower Gleason grade and better survival than fusion-negative tumors |

| 10 | Yoshimoto, M. et al. (2006)49 | TMPRSS2:ERG fusion RT-PCR and DNA sequencing |

PCa cases, Surgically treated (n=15) | No Correlation with clinical outcome |

| 11 | Lapointe, J. et al. (2007)46 | TMPRSS2:ERG fusion RT-PCR and DNA sequencing TMPRSS2:ERG Fusion FISH |

PCa cases, Surgically treated (n=54) Hormone naiive pelvic lymph node metastases (n=9) | No association with tumor stage, Gleason grade or recurrence-free survival |

Multifocal prostate cancer

Localized prostate cancer is typically multi-focal with different foci displaying histological and molecular heterogeneity67. When the status of gene rearrangements in 93 tumor foci from 43 radical prostatectomy resections were analyzed, 70% of the cases were found rearranged at TMPRSS2 locus, higher than accounted for by TMPRSS2:ERG fusions seen in 55% of the cases68. Our study showed that a small percentage of prostate cancers cases might harbor uncharacterized fusion partners driven by the upstream regulatory elements of TMPRSS259, 68. Further, attesting to the heterogeneity of multi-focal cancers, 70% of the cases showed divergent gene rearrangements in the different foci68. In another study of TMPRSS2:ERG fusions in multi-focal prostate cancers, Barry et al. reported that 41% of foci harbored different gene rearrangements69. Further, Clark et al have reported the detection of TMPRSS2:ERG and TMPRSS2:ETV1 in two different foci of a prostate cancer70.

Metastatic prostate cancer

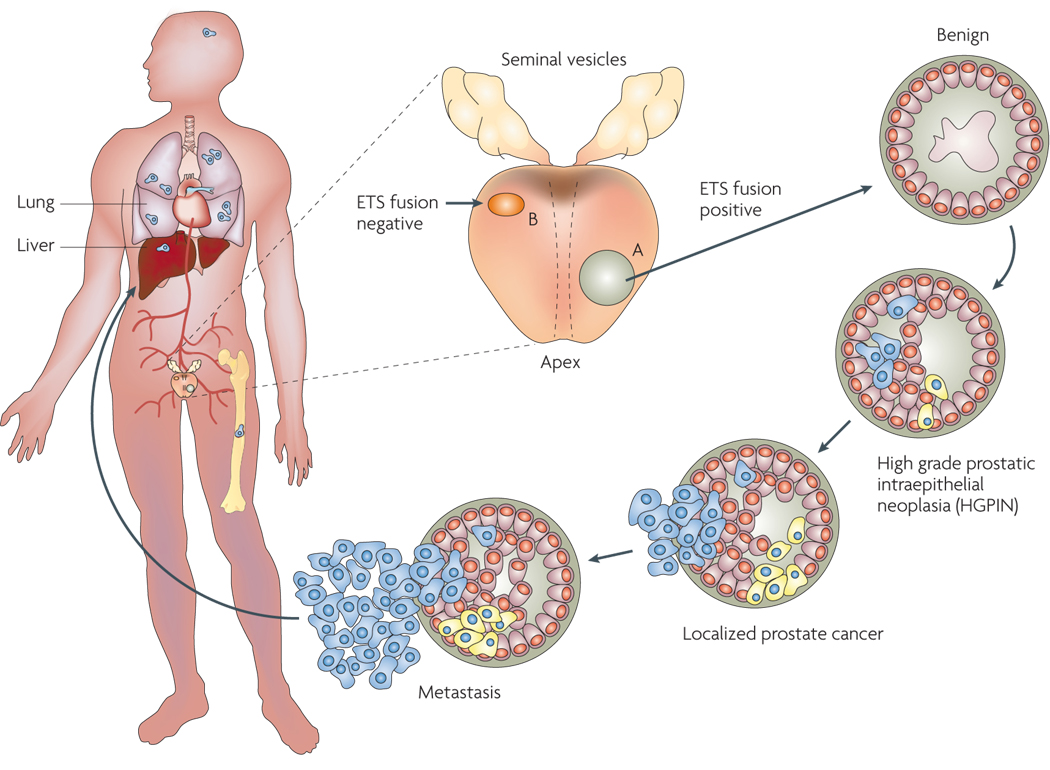

When we surveyed the different metastatic sites of hormone refractory prostate cancer for ETS gene rearrangements, we made two unexpected observations: (1) All the metastatic sites from a patient display identical ETS rearrangement status (fusion positive or negative), and (2) All of the metastatic prostate cancer sites harboring TMPRSS2:ERG were found to be a result of interstitial deletion (EDel) suggesting that Edel is a lethal sub-type of prostate cancer associated with androgen-independent disease71. Earlier, Attard et al. have correlated EDel gene fusions with poorer prognosis62 and Perner et al., with high tumor stage and ‘metastases to pelvic lymph nodes’41. Together, these observations strongly suggest that metastatic cancer arises through clonal expansion of malignant cells from a unique primary focus of dissemination, which argues for a careful assessment of different tumor foci of a patient for an accurate prognostication71 (FIG. 3).

FIGURE 3. Genesis and Progression of Gene Fusions in Prostate Cancer.

ETS gene fusions can first be observed in a subset of high grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (HGPINs). Intriguingly, these foci are nearly invariably associated with intermingling foci of carcinoma, suggesting that ETS gene fusions may drive the progression to localized prostate cancer. Alternative lesions likely drive the development of ETS gene fusion negative HGPIN and localized carcinoma. While the same prostate may harbor both fusion positive and negative tumor foci, only a single foci metastasizes to distant organs, as different metastatic sites in the same patient are uniformly fusion positive or negative.

Other Clinical associations

Although gene fusions are prima facie acquired somatic mutations, we have observed samples from hereditary prostate cancer (HPC) patients to be three times more likely to harbor ERG rearrangements than those from sporadic prostate cancers patients (unpublished observations). Similar familial associations have also been reported with respect to gene-fusion rich myeloproliferative disorders72. Our observations could have important clinical implications for the 5–10% of hereditary (as well as 10–20% of familial) prostate cancer patients73. Interestingly, our preliminary observations do not suggest any racial differences in the prevalence of the gene fusions (unpublished observations). Any future studies dealing with these important assessments would need to factor in the multi-focal heterogeneity of the rearrangements, as well as include broader ETS family gene rearrangement screens. Another area of clinical interest would be the assessment of rearrangement status in response to salvage radiotherapy that could facilitate the identification of patients at the risk for recurrence.

Molecular Aberrations associated with Gene Fusions

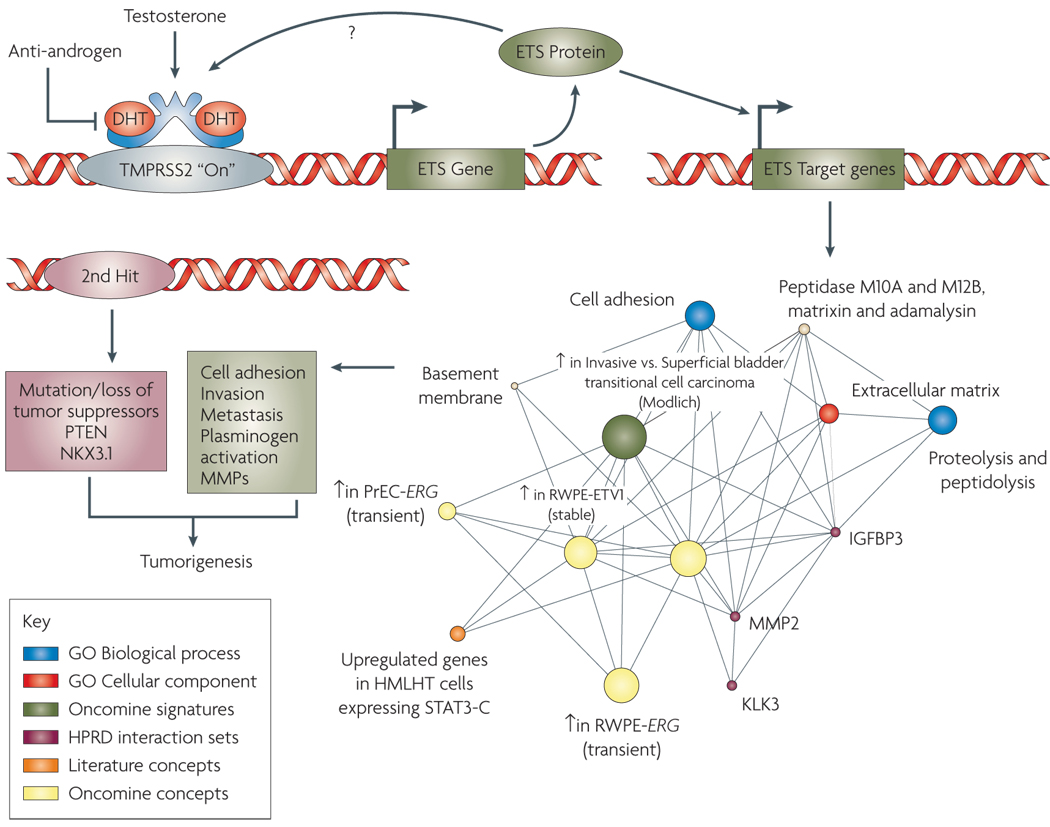

To elucidate the role of ETS gene fusions in prostate cancer biology (FIG. 4), attempts have been made to define gene expression signatures of ETS-gene over-expressing prostate cancers. A meta-analysis of multiple expression data from 410 human prostate tissue samples (178 normal and 232 tumors and metastases) was performed to identify genes correlated with ERG overexpression45. A strong association was made with high expression of the HDAC1 gene and (presumably, consequently) low expression of its target genes. In the same study, an increased expression of WNT-associated pathways and down-regulation of TNF and cell death pathways was also noted. Gene expression profiling of TMPRSS2:ERG positive samples lead Setlur et al. to define an 87-gene signature-enriched for Estrogen Receptor signaling pathway genes, associated with the gene fusion positive prostate cancer tissues74. Follow-up functional studies corroborated the regulation of TMPRSS2:ERG expression by estrogenic compounds in an androgen non-responsive prostate cancer cell line harboring the fusion. Increased expression of ERα has been associated with prostate cancer progression, metastasis and androgen resistant phenotype75. Taken together, these observations suggest an attractive new therapeutic approach for metastatic prostate cancers that fail androgen ablation therapy (discussed in more detail in a later section).

FIGURE 4. Role of Gene Fusions in Prostate Cancer.

Androgen mediated upregulation of ETS genes (for example ERG or ETV1) leads to the activation of ETS target genes that upregulate various “Molecular Concepts” as identified by Molecular Concept Modeling (MCM)33, 77, 87 and comprise genes involved in increased protein synthesis, cell adhesion and invasion including Urokinase plasminogen activator (PLAU) and several matrix metalloproteases. Preceding genetic lesions, including the loss of a tumor suppressor such as phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN), likely drive the development of PIN, while subsequent ETS gene mediated molecular alterations lead to the development of invasive prostate carcinogenesis.

Since ETS gene fusions appear to account for 50–60% of all prostate cancers, non-ETS fusion cancers may constitute a clinically relevant group as well. We carried out a meta-analysis of three independent gene expression profiling studies76–78 for comparison of ETS fusion positive prostate cancers with non-ETS cancers. Importantly, ETS positive and negative tumors had distinct expression, signatures that were maintained across studies and platforms. Using a molecular concepts based analysis (Molecular Concepts Map24), we observed a relative under-expression of genes on chromosomal region 6q21 (for example FOXO3A and CCNC) in non-ETS prostate cancers77. In a subsequent array-CGH analysis from our group, we noted a loss of 6q21 in >45% of non-ETS samples79. Recently, Lapointe et al. described a deletion at a nearby locus, 6q15 in non-ETS prostate cancer samples80. Together, these results suggest that ETS positive and negative tumors may be fundamentally different types of prostate cancer, driven by distinct genetic aberrations whose effects can be seen in expression signatures.

PIN studies

TMPRSS2:ERG rearrangements have been observed in the prostate cancer precursor tissue, high grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (HGPIN), albeit at a lower frequency. Using a PCR based approach, Cerveira et al reported TMPRSS2:ERG fusion in 4/19 (21%) of samples examined39, while Perner et al reported a very comparable incidence at 5/26 (19.2%) using a FISH based approach42. The latter report also indicated that fusion positive HGPIN is almost always present in close proximity of fusion positive cancer tissue. A recent study by Clark et al reports HGPIN, as well as some foci resembling low grade PIN (LGPIN), closely associated with fusion positive prostate cancer that harbor ERG rearrangements, in as many as six out of nine prostate cancer samples analyzed70. Together, these observations strongly suggest that the ETS gene rearrangements may be early events in prostate carcinogenesis.

Functional studies of ETS Gene Fusions in Prostate Cancer

Functional characterization of the role of ETS gene fusions in prostate cancer has primarily focused on assessment of prostate specificity and androgen responsiveness of the fusion genes and the mechanistic role of fusion genes in carcinogenesis. As TMPRSS2 is prostate specific and strongly induced by androgen,81–83 we tested if the TMPRSS2:ERG fusion gene is androgen regulated as well. Androgen treatment induced ERG expression in prostate cancer cell line VCaP harboring TMPRSS2:ERG fusion, but not in LNCaP cells, which are androgen responsive but do not have this fusion5. Likewise, there was no induction of ERG or TMPRSS2:ERG expression in the androgen insensitive NCI-H660 prostate cancer cell line carrying the TMPRSS2:ERG fusion84. Similarly, Hermans et al. found ERG expression restricted to the androgen-sensitive human prostate cancer xenografts carrying the TMPRSS2:ERG fusion, but not in androgen insensitive samples nor in the samples without the fusion44.

Although only TMPRSS2 has been reported as a 5’ fusion partner of ERG, additional 5’ partners have been identified for ETV1, ETV4 and ETV5. These 5’ partners include TMPRSS2, SLC45A3, HERV-K_22q11.23, C15orf21, CANT1 and KLK2, which are prostate-specific, while HNRPA2B1 has a ubiquitous housekeeping expression. With respect to androgen regulation, TMPRSS2, SLC45A3, HERV-K_22q11.23, CANT1 and KLK2 contribute androgen-inducible sequences, while C15orf21 is repressed by androgen treatment and HNRPA2B1 is insensitive to androgens. As androgen ablation therapy is central to advanced prostate cancer management, the divergent androgen responsiveness driving the fusion genes could affect response to therapy and disease progression. This may provide important clues into the biology of hormone insensitive samples as well.

While the upstream regulatory elements of fusion partners dictate prostate-specific, androgen-responsive expression of the ETS genes, an obvious next question is whether these gene fusions are carcinogenic in the prostate. This aspect has been investigated by our group, as well as others, and the results, though not definitive, are very compelling.

To recapitulate the biological effects of aberrant over-expression of ETV1 in the prostate, truncated ETV1 was ectopically over-expressed in prostate epithelial cell lines RWPE and PrEC. Surprisingly, we found it did not cause cell transformation and had no effect on cell proliferation or anchorage independent growth; instead, it made the epithelial cells invasive through matrigel assays33. In a complementary observation, LnCaP cells lost their invasiveness when ETV1 expression was knocked down33, 85. Consistent with these phenotypic observations, the gene expression signature of ETV1-overexpresssing RWPE cells shows an enrichment of molecular concepts (biologically related genes) involved in invasion33.

To investigate the effects of the gene fusions in vivo, we generated transgenic mice over-expressing ETV1 in prostate epithelium (using a prostate specific, androgen regulated, probasin (Pb) promoter86). Six out of eight (75%) transgenic mice developed mouse prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (mPIN), which was variably present in all three prostatic lobes (anterior, ventral and dorsolateral), by 12–14 weeks of age. Consistent with our in vitro observations, none of the mPIN foci developed into tumors, which strongly suggests that additional genetic lesions/ environmental factors are required for the development of carcinoma. Virtually identical observations were made in ERG over-expression studies in vitro as well as in transgenic Pb-ERG mice by two independent groups87, 88, and in ETV5 over-expression studies in vitro35.

That transgenic Pb-ERG and Pb-ETV1 mice do not develop frank carcinoma is consistent with clinical observations in human prostate cancer development and progression. Comprehensive FISH analysis showed no ERG rearrangements in benign prostate glands, ∼20% of PIN lesions (but only intermingling with cancer foci that harbored similar ERG rearrangements), ∼50% of localized prostate cancers, and ∼30% of metastatic prostate cancers42. Thus, preceding genetic lesions likely function to deregulate cellular proliferation resulting in PIN, while ETS fusions drive the transition to carcinoma. As metastatic foci from a single case are homogeneous in regards to ETS status, ETS fusions clearly occur before metastasis. We33, 87 and others89 have speculated that loss of tumor suppressors such as PTEN or NKX3-1 may precede and cooperate with ETS gene fusions to drive cancer development; compound transgenic mice recapitulating these lesions will likely represent an ideal model of human prostate cancer.

Diagnostic, Prognostic, and Predictive Implications of the Gene Fusions

The application of serum measurement of prostate specific antigen (PSA) in prostate cancer diagnosis, prognosis and disease follow-up has had a dramatic impact on prostate cancer management by providing a simple and sensitive primary screening modality to diagnose prostate cancers at a curable stage (reviewed4). However, the PSA test exhibits poor specificity, and is often elevated in benign conditions such as prostatitis and benign prostatic hyperplasia90, 91. The diagnosis of indolent prostate cancers has also added to an avoidable cancer burden (reviewed92). Therefore, there is an urgent need for better biomarkers that can distinguish indolent from clinically significant prostate cancer and can reduce the number of unnecessary biopsies (estimated at 70–80%92).

As described in this review, ETS positive and negative tumors have distinct morphological features, unique expression signatures, and distinct clinical outcomes. These results suggest that ETS negative tumors may harbor other classes of gene fusions, may be driven by distinct molecular mechanisms, or may occur at a different stage of prostate cell differentiation. As prostate cancer is recognized as being heterogenous in both biological and clinical phenotypes, we propose that current data supports two classes of prostate cancer: ETS gene fusion positive and ETS gene fusion negative. Thus, a sensitive and specific screening test for ETS gene fusions, which do not occur in benign prostate tissue or in ETS negative cancers, will likely outperform serum PSA for detection of this class of prostate cancer.

Detection of fusions is envisaged from needle biopsies or prostate cells isolated from blood. Recently, Mao et al reported the detection of TMPRSS2-ERG fusion from circulating tumor cells93. Since prostate tumor cells are also shed in the urine, PCR based detection of fusion transcripts from urine sediments could provide a noninvasive adjunct to diagnose this class of prostate cancer. We reported sensitive and specific detection of TMPRSS2:ERG fusion transcript from the urine sediments of prostate cancer patients94, as well as analyzed the fusion transcript in combination with other putative prostate cancer biomarkers in urine sediments using qPCR95. In this discovery study, multiplexed detection of GOLPH2, SPINK1, PCA3 and TMPRSS2:ERG fusion transcripts outperformed serum PSA or PCA3 alone in detecting prostate cancer. Combined detection of TMPRSS2:ERG and PCA3 transcripts in urine was reported to provide improved sensitivity of detection of prostate cancer in another study96. Future refinement of these tests may lead to a clinical supplement to serum PSA for detecting ETS positive prostate cancer.

As discussed earlier, the inter-focal heterogeneity of prostate cancer gene fusions predicates assessment of multiple needle biopsies68. With the continual refinement of clinical association studies, we expect that identification of specific gene fusions will assist in a molecular classification of prostate cancers. For example, as specific fusion subtypes (such as EDel) are correlated with poorer outcome, patients harboring these events could be considered for more aggressive treatment modalities. Importantly, as indicated by multiple regulatory partners of EJV133, it is surmised that this information may eventually become integral to therapeutic decision making.

Therapeutic Implications of Prostate Cancer Gene Fusions

Androgen signaling is pivotal to prostate cancer development and survival. “Androgen ablation” therapy continues to be a core treatment modality since the pioneering application of castration and estrogen administration by Charles Huggins in early 1940s3, 97, 98, followed by use of LHRH agonists by Andrew Schally99, and more recently replaced by various androgen receptor blockers100, like cyproterone101, and cyproterone acetate102 followed by non-steroidal anti-androgens like flutamide103, bicalutamide and nilutamide100. Unfortunately, although androgen ablation provides considerable palliative relief for most patients, it is almost never completely curative, either as a mono-therapy or in combined androgen blockade modalities, and eventually, most recurrent tumors progress to hormone independent disease104, 105.

TMPRSS2:ERG fusion-bearing tumors have been associated with aggressive tumors with lethal phenotype, so it follows that targeting ERG activity in fusion positive samples might offer novel therapeutic avenues for prostate cancer. Discovery of estrogen signaling pathways induced in TMPRSS2:ERG positive androgen non-responsive cases may be significant in this respect. Efforts are also underway to identify small molecule inhibitors to ERG activity, as well as to identify downstream targets of ERG protein, that could provide additional therapeutic targets.

Implications for the Future

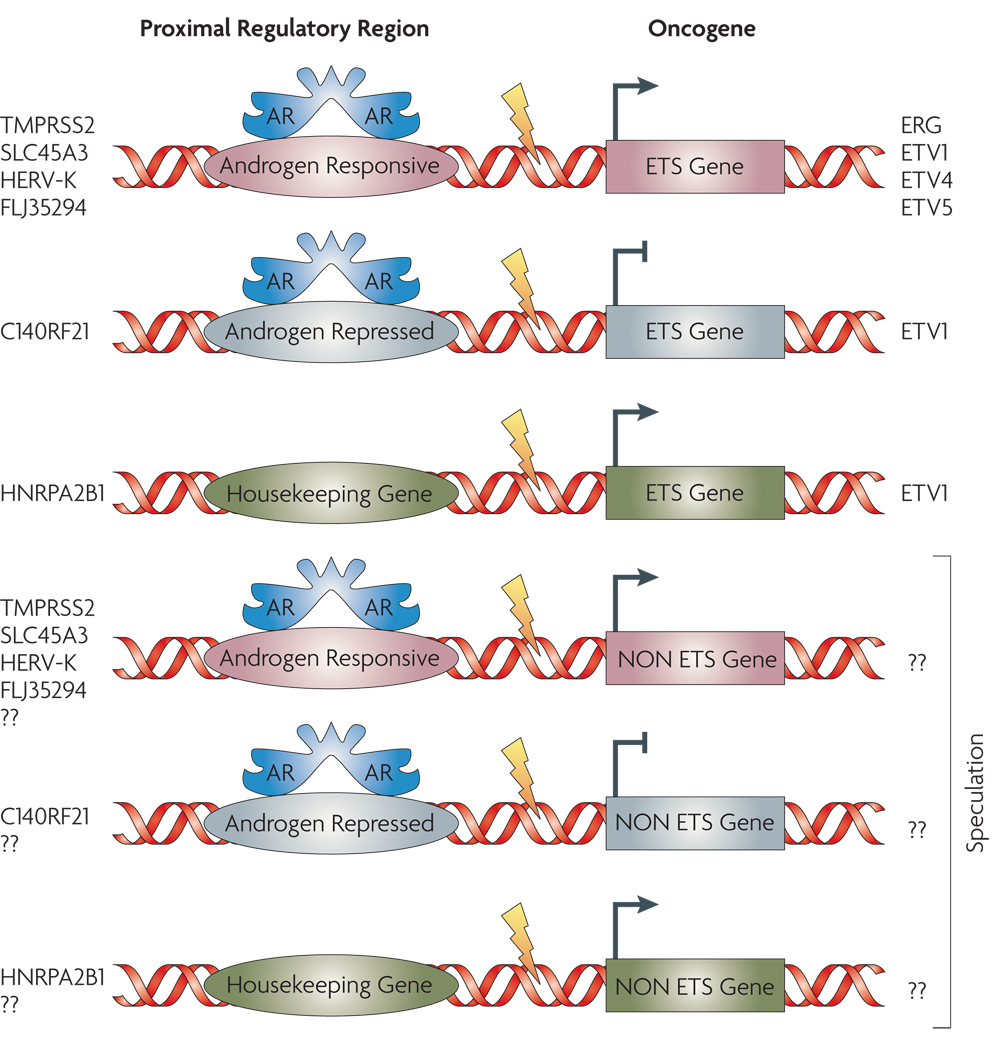

Genomic rearrangements creating ‘gene fusions’ arguably represent the most common mutation class in human cancers, even though until recently they have been largely characterized in rare hematological and soft tissue malignancies6. In this respect, the presence of similar gene fusions in cancers of epithelial origin is remarkable for having eluded discovery till recently. Identification of recurrent gene fusions in prostate cancer by the ‘non-cytogenetic’ approach of gene expression analysis followed by characterization of ‘outlier’ genes represents a novel, albeit one of many possible, technique to explore solid cancers for similar genomic aberrations. The recent report of the presence of EML4-ALK fusion transcript in 6.7% (5 out of 75) of non small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients, revealed by functional screening of the cancer tissue transcriptome (cDNA expression library)106, and the discovery of ALK and ROS fusion proteins in NSCLC through an outlier analysis of the phosphoproteome of cancer tissues and cell lines107, represent other successful approaches. Genome-wide search for “fusion-transcripts” by next generation sequencing approaches108, 109 followed by high throughput TMA-FISH are likely to be used for future gene-fusion explorations in other common carcinoma. We envision a wider prevalence of gene fusions in prostate cancer, possibly involving other regulatory elements and non-ETS genes that are yet to be discovered (FIG. 5).

FIGURE 5. Gamut of Gene Fusions in Prostate Cancer.

Six major classes of pathognomic gene fusions in prostate cancer are envisioned based on the types of upstream regulatory partners and the nature of the fused genes. These include regulatory regions that are either androgen responsive or androgen repressed or androgen insensitive (housekeeping) fused to ETS family genes or other, yet to be discovered, non-ETS genes

An understanding of the diverse regulatory “on/off switches” driving oncogene expression in prostate cancer tissues might lead to clarification of the molecular heterogeneity of multifocal prostate cancer in tandem with the clonally homogenous nature of disseminated foci of metastatic tumors. Recurrent gene fusions appear to be correlated with prostate cancer development and progression, and more studies with larger patient cohorts should identify specific clinical correlates. Continued studies on the relationship between gene fusions, androgen responsiveness, and hormone refractory metastatic disease is crucial as the varying androgen responsiveness of different regulatory elements may drive markedly different responses with androgen deprivation therapy. Considering the research summarized in this review, we propose a molecular classification of prostate cancers--ETS fusion positive and negative--that will likely serve to guide future diagnostic, prognostic and therapeutic advances in prostate cancer.

At a glance

Approximately 50% prostate cancers from serum PSA-screened cohorts harbor recurrent gene fusions.

The gene fusions in prostate cancer are characterized by 5’ genomic regulatory elements, most commonly controlled by androgen, fused to members of the ETS family of transcription factors.

TMPRSS2:ERG is the most common gene fusion, present in about half of all localized prostate cancers analyzed. TMPRSS2 also fuses to other ETS family genes such as ETV1, ETV4 and ETV5 in a small percentage of prostate cancers.

ETV1, ETV4 and ETV5 have additional 5’ fusion partners, that differ in their prostate specificity and response to androgen.

Many ETS gene fusion transcript variants have been idetnfied with different 5’ and 3’ partner sequences, likely with prognostic/ diagnostic implications.

Prostate cancers harboring TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusion display characteristic morphological features of prostate cancers such as macronucleoli, intraductal tumour spread as well as rare blue-tinged mucin, cribriform growth pattern and signet-ring cell.

ERG overexpression imparts invasiveness to prostate cells in vitro and induces plasminogen activation, and matrix metalloprotease pathways.

ETS gene fusion positive and negative prostate cancers have distinct chromosomal aberrations, expression signatures, morphological features and clinical outcomes, suggesting that they represent fundamentally different classes of prostate cancer.

Sensitive and specific diagnostic tests and targeted therapeutics will impact the detection and management of ETS positive prostate cancer.

Side Bars

PIN: Prostatic Intraepithelial Neoplasia defines foci of rapidly dividing prostate epithelial cells, believed to be the precursor of prostate cancer. PINs are typically classified as high grade, medium grade and low grade, depending on their level of differentiation. Approximately one third of men with high grade PIN (HGPIN) develop prostate cancer.

Mitelman Database of Chromosome Aberrations in Cancer: A manually curated database of all published cases of cytogenetic aberrations in cancer along with their clinical associations has been collated by Mitelman et al110. This database currently has information on 53,946 cancer cases (November 26, 2007) involving more than 350 gene fusions and other cytogenetic aberrations documented in cancers. (http://cgap.nci.nih.gov/Chromosomes/Mitelman).

Gene fusion: A physical linking of two genes (typically accompanied with deletion of portions of the two partner genes) such that they come to share a common regulatory element and/or open reading frames (ORFs), the latter encoding chimeric proteins, for example BCR-ABL1 or TMPRSS2-ERG.

ETS: The E26 Transformation Specific family of genes encodes nuclear transcription factors, characterized by DNA binding ETS domains and various protein interaction domains. ETS family proteins are involved in cell growth, signal transduction, cell cycle regulation, apoptosis, hematopoietic, neuronal and myogenic differentiation, and in several human malignancies, such as Ewing’s tumors, leukemias and in prostate cancer.

TMPRSS2: An androgen-regulated type II transmembrane serine protease (TTSP) expressed highly in normal prostate epithelium and prostate cancer cells. TMPRSS2 null mice develop to normal, fertile adulthood111.

PLAU: Urokinase Plasminogen Activator is a serine protease that degrades extracellular matrix involved in tumor cell migration and proliferation. ERG induces PLAU overexpression and inhibition of PLAU blocks ERG mediated invasion.

Androgen ablation: A core prostate cancer treatment modality that involves severing androgen signaling in prostate cancer either by physical means (castration) or biochemically, by injecting estrogens, or anti Androgens, or Androgen Receptor agonists/ antagonists. Charles Huggins was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, 1966 for this development in 1941.

Molecular Concepts Map (MCM): Gene expression signatures of sets of biologically connected genes, such as ‘lipid biosynthesis genes’ or ‘androgen activated genes’ etc have been defined as 'molecular concepts' and over 40,000 such concepts have been compiled in Oncomine. The MCM involves interrogating a set of user defined genes (such as an expression signature or genes identified in a functional screen) against all Concepts in the MCM to identify molecular networks enriched in the query set.

Acknowledgements

We apologize to all the authors whose work could not be included in this manuscript due to space constraints.

We thank Jill Granger for her scientific editorial assistance. We thank Rohit Mehra, Nallasivam Palanisamy, and Saravana Mohan Dhanasekharan for useful discussions. We thank Robin Kunkel for help with the art-work for figures. This work was supported in part by Department of Defense, the National Institutes of Health, the Early Detection Research Network, and the Prostate Cancer Foundation, to A.M.C. A.M.C. is supported by a Clinical Translational Research Award from the Burroughs Wellcome Foundation. S.A.T. is a Fellow of the Medical Scientist Training Program and is supported by the GPC Biotech Young Investigator Award from the Prostate Cancer Foundation.

Footnotes

Competing Interest Statement

The University of Michigan has filed for a patent on the detection of gene fusions in prostate cancer, on which S.A.T. and A.M.C. are co-inventors. The diagnostic field of use has been licensed to GenProbe Inc. GenProbe has had no role in the design or experimentation of this study, nor has it participated in the writing of the manuscript. Oncomine and the MCM are freely available to the academic community. The commercial rights to Oncomine and MCM have been licensed to Compendia Bioscience, which A.M.C. co-founded.

A summary of the published literature on the characterization of recurrent gene fusions in prostate cancer. The columns in order from left to right detail the gene fusion, sample cohort the data is derived from, the frequency of the gene fusion in the sample setobserved gene fusion/ total number of samples examined (% gene fusion in the sample cohort), the assay used for detection and characterization of the gene fusions, and the reference.

Databases

Mitelman Database: http://cgap.nci.nih.gov/Chromosomes/Mitelman

Oncomine: http://www.oncomine.org/

Atlas of Genetics and Cytogenetics: http://atlasgeneticsoncology.org/index.html

Entrez gene: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?db=gene

COPA package in R: http://www.bioconductor.org

COPA package integrated into SAM: http://www-stat.stanford.edu/~tibs/SAM

References

- 1.American Cancer Society: Cancer Facts & Figures 2007. 2007 www.acs.org.

- 2.Lilja H, Ulmert D, Vickers AJ. Prostate-specific antigen and prostate cancer: prediction, detection and monitoring. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:268–278. doi: 10.1038/nrc2351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Denmeade SR, Isaacs JT. A history of prostate cancer treatment. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:389–396. doi: 10.1038/nrc801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Loeb S, Catalona WJ. Prostate-specific antigen in clinical practice. Cancer Lett. 2007;249:30–39. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2006.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tomlins SA, et al. Recurrent fusion of TMPRSS2 and ETS transcription factor genes in prostate cancer. Science. 2005;310:644–648. doi: 10.1126/science.1117679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Futreal PA, et al. A census of human cancer genes. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:177–183. doi: 10.1038/nrc1299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ren R. Mechanisms of BCR-ABL in the pathogenesis of chronic myelogenous leukaemia. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:172–183. doi: 10.1038/nrc1567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goldman JM, Melo JV. Chronic myeloid leukemia--advances in biology and new approaches to treatment. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1451–1464. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra020777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nowell PC, Hungerford DA. Chromosome studies on normal and leukemic human leukocytes. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1960;25:85–109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nowell PC, Hungerford DA. Chromosome studies in human leukemia. II. Chronic granulocytic leukemia. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1961;27:1013–1035. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rowley JD. Letter: A new consistent chromosomal abnormality in chronic myelogenous leukaemia identified by quinacrine fluorescence and Giemsa staining. Nature. 1973;243:290–293. doi: 10.1038/243290a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rowley JD. Chromosome translocations: dangerous liaisons revisited. Nat Rev Cancer. 2001;1:245–250. doi: 10.1038/35106108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Druker BJ, et al. Activity of a specific inhibitor of the BCR-ABL tyrosine kinase in the blast crisis of chronic myeloid leukemia and acute lymphoblastic leukemia with the Philadelphia chromosome. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1038–1042. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200104053441402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Druker BJ, et al. Efficacy and safety of a specific inhibitor of the BCR-ABL tyrosine kinase in chronic myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1031–1037. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200104053441401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mitelman F, Mertens F, Johansson B. Prevalence estimates of recurrent balanced cytogenetic aberrations and gene fusions in unselected patients with neoplastic disorders. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2005;43:350–366. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kumar-Sinha C, Tomlins SA, Chinnaiyan AM. Evidence of recurrent gene fusions in common epithelial tumors. Trends Mol Med. 2006 doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2006.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mitelman F. Recurrent chromosome aberrations in cancer. Mutat Res. 2000;462:247–253. doi: 10.1016/s1383-5742(00)00006-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mitelman F, Johansson B, Mandahl N, Mertens F. Clinical significance of cytogenetic findings in solid tumors. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 1997;95:1–8. doi: 10.1016/s0165-4608(96)00252-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mitelman F, Johansson B, Mertens F. Fusion genes and rearranged genes as a linear function of chromosome aberrations in cancer. Nat Genet. 2004;36:331–334. doi: 10.1038/ng1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Narod SA, Foulkes WD. BRCA1 and BRCA2: 1994 and beyond. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:665–676. doi: 10.1038/nrc1431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jeter JM, Kohlmann W, Gruber SB. Genetics of colorectal cancer. Oncology (Williston Park) 2006;20:269–276. discussion 285–6, 288–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rowley PT. Inherited susceptibility to colorectal cancer. Annu Rev Med. 2005;56:539–554. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.56.061704.135235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lynch TJ, et al. Activating mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor underlying responsiveness of non-small-cell lung cancer to gefitinib. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2129–2139. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rhodes DR, et al. Molecular concepts analysis links tumors, pathways, mechanisms, and drugs. Neoplasia. 2007;9:443–454. doi: 10.1593/neo.07292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rhodes DR, et al. Oncomine 3.0: genes, pathways, and networks in a collection of 18,000 cancer gene expression profiles. Neoplasia. 2007;9:166–180. doi: 10.1593/neo.07112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rhodes DR, et al. Mining for regulatory programs in the cancer transcriptome. Nat Genet. 2005;37:579–583. doi: 10.1038/ng1578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rhodes DR, et al. ONCOMINE: a cancer microarray database and integrated data-mining platform. Neoplasia. 2004;6:1–6. doi: 10.1016/s1476-5586(04)80047-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oikawa T, Yamada T. Molecular biology of the Ets family of transcription factors. Gene. 2003;303:11–34. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(02)01156-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sorensen PH, et al. A second Ewing's sarcoma translocation, t(21;22), fuses the EWS gene to another ETS-family transcription factor, ERG. Nat Genet. 1994;6:146–151. doi: 10.1038/ng0294-146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Adams JM, et al. The c-myc oncogene driven by immunoglobulin enhancers induces lymphoid malignancy in transgenic mice. Nature. 1985;318:533–538. doi: 10.1038/318533a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Taub R, et al. Translocation of the c-myc gene into the immunoglobulin heavy chain locus in human Burkitt lymphoma and murine plasmacytoma cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1982;79:7837–7841. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.24.7837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tsujimoto Y, Finger LR, Yunis J, Nowell PC, Croce CM. Cloning of the chromosome breakpoint of neoplastic B cells with the t(14;18) chromosome translocation. Science. 1984;226:1097–1099. doi: 10.1126/science.6093263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tomlins SA, et al. Distinct classes of chromosomal rearrangements create oncogenic ETS gene fusions in prostate cancer. Nature. 2007;448:595–599. doi: 10.1038/nature06024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tomlins SA, et al. TMPRSS2:ETV4 gene fusions define a third molecular subtype of prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2006;66:3396–3400. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Helgeson BE, et al. Characterization of TMPRSS2:ETV5 and SLC45A3:ETV5 Gene Fusions in Prostate Cancer. Cancer Research. 2007 doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5352. in Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.MacDonald JW, Ghosh D. COPA--cancer outlier profile analysis. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:2950–2951. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tibshirani R, Hastie T. Outlier sums for differential gene expression analysis. Biostatistics. 2007;8:2–8. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/kxl005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Annunziata CM, et al. Frequent engagement of the classical and alternative NF-kappaB pathways by diverse genetic abnormalities in multiple myeloma. Cancer Cell. 2007;12:115–130. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cerveira N, et al. TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusion causing ERG overexpression precedes chromosome copy number changes in prostate carcinomas and paired HGPIN lesions. Neoplasia. 2006;8:826–832. doi: 10.1593/neo.06427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Clark J, et al. Diversity of TMPRSS2-ERG fusion transcripts in the human prostate. Oncogene. 2007;26:2667–2673. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Perner S, et al. TMPRSS2:ERG Fusion-Associated Deletions Provide Insight into the Heterogeneity of Prostate Cancer. Cancer Res. 2006;66:8337–8341. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Perner S, et al. TMPRSS2-ERG fusion prostate cancer: an early molecular event associated with invasion. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31:882–888. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000213424.38503.aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mehra R, et al. Characterization of TMPRSS2-ETS Gene Aberrations in Androgen-Independent Metastatic Prostate Cancer. Cancer Res. 2008;68:3584–3590. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hermans KG, et al. TMPRSS2:ERG fusion by translocation or interstitial deletion is highly relevant in androgen-dependent prostate cancer, but is bypassed in late-stage androgen receptor-negative prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2006;66:10658–10663. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Iljin K, et al. TMPRSS2 fusions with oncogenic ETS factors in prostate cancer involve unbalanced genomic rearrangements and are associated with HDAC1 and epigenetic reprogramming. Cancer Res. 2006;66:10242–10246. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lapointe J, et al. A variant TMPRSS2 isoform and ERG fusion product in prostate cancer with implications for molecular diagnosis. Mod Pathol. 2007;20:467–473. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rajput AB, et al. Frequency of the TMPRSS2:ERG gene fusion is increased in moderate to poorly differentiated prostate cancers. J Clin Pathol. 2007 doi: 10.1136/jcp.2006.043810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Soller MJ, et al. Confirmation of the high frequency of the TMPRSS2/ERG fusion gene in prostate cancer. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2006;45:717–719. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yoshimoto M, et al. Three-color FISH analysis of TMPRSS2/ERG fusions in prostate cancer indicates that genomic microdeletion of chromosome 21 is associated with rearrangement. Neoplasia. 2006;8:465–469. doi: 10.1593/neo.06283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang J, Cai Y, Ren C, Ittmann M. Expression of Variant TMPRSS2/ERG Fusion Messenger RNAs Is Associated with Aggressive Prostate Cancer. Cancer Res. 2006;66:8347–8351. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liu W, et al. Multiple genomic alterations on 21q22 predict various TMPRSS2/ERG fusion transcripts in human prostate cancers. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2007;46:972–980. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Melo JV. The diversity of BCR-ABL fusion proteins and their relationship to leukemia phenotype. Blood. 1996;88:2375–2384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lynch HT, Smyrk T, Lynch JF. Overview of natural history, pathology, molecular genetics and management of HNPCC (Lynch Syndrome) Int J Cancer. 1996;69:38–43. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19960220)69:1<38::AID-IJC9>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Halvarsson B, et al. Phenotypic heterogeneity in hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer: identical germline mutations associated with variable tumour morphology and immunohistochemical expression. J Clin Pathol. 2007;60:781–786. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2006.040402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lakhani SR, et al. Multifactorial analysis of differences between sporadic breast cancers and cancers involving BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90:1138–1145. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.15.1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lakhani SR. The pathology of familial breast cancer: Morphological aspects. Breast Cancer Res. 1999;1:31–35. doi: 10.1186/bcr10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mosquera JM, et al. Morphological features of TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusion prostate cancer. J Pathol. 2007;212:91–101. doi: 10.1002/path.2154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tu JJ, et al. Gene fusions between TMPRSS2 and ETS family genes in prostate cancer: frequency and transcript variant analysis by RT-PCR and FISH on paraffin-embedded tissues. Mod Pathol. 2007 doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mehra R, et al. Comprehensive assessment of TMPRSS2 and ETS family gene aberrations in clinically localized prostate cancer. Mod Pathol. 2007;20:538–544. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nami RK, et al. Expression of TMPRSS2:ERG gene fusion in prostate cancer cells is an important prognostic factor for cancer progression. Cancer Biol Ther. 2007;6:40–45. doi: 10.4161/cbt.6.1.3489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nam RK, et al. Expression of the TMPRSS2:ERG fusion gene predicts cancer recurrence after surgery for localised prostate cancer. Br J Cancer. 2007 doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Attard G, et al. Duplication of the fusion of TMPRSS2 to ERG sequences identifies fatal human prostate cancer. Oncogene. 2007 doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Demichelis F, et al. TMPRSS2:ERG gene fusion associated with lethal prostate cancer in a watchful waiting cohort. Oncogene. 2007;26:4596–4599. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Petrovics G, et al. Frequent overexpression of ETS-related gene-1 (ERG1) in prostate cancer transcriptome. Oncogene. 2005;24:3847–3852. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Winnes M, Lissbrant E, Damber JE, Stenman G. Molecular genetic analyses of the TMPRSS2-ERG and TMPRSS2-ETV1 gene fusions in 50 cases of prostate cancer. Oncol Rep. 2007;17:1033–1036. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nam RK, et al. Expression of TMPRSS2:ERG gene fusion in prostate cancer cells is an important prognostic factor for cancer progression. Cancer Biol Ther. 2007;6:40–45. doi: 10.4161/cbt.6.1.3489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Arora R, et al. Heterogeneity of Gleason grade in multifocal adenocarcinoma of the prostate. Cancer. 2004;100:2362–2366. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mehra R, et al. Heterogeneity of TMPRSS2 Gene Rearrangements in Multifocal Prostate Adenocarcinoma: Molecular Evidence for an Independent Group of Diseases. Cancer Res. 2007;67:7991–7995. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Barry M, Perner S, Demichelis F, Rubin MA. TMPRSS2-ERG fusion heterogeneity in multifocal prostate cancer: clinical and biologic implications. Urology. 2007;70:630–633. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2007.08.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Clark J, et al. Complex patterns of ETS gene alteration arise during cancer development in the human prostate. Oncogene. 2008;27:1993–2003. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mehra R, et al. Characterization of TMPRSS2-ETS Gene Aberrations in Androgen Independent Metastatic Prostate Cancer. Cancer Res. 2008 doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6154. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Skoda R, Prchal JT. Lessons from familial myeloproliferative disorders. Semin Hematol. 2005;42:266–273. doi: 10.1053/j.seminhematol.2005.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Langeberg WJ, Isaacs WB, Stanford JL. Genetic etiology of hereditary prostate cancer. Front Biosci. 2007;12:4101–4110. doi: 10.2741/2374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Setlur SR, et al. TMPRSS2-ERG fusion prostate cancer is a molecularly distinct estrogen-sensitive subclass of aggressive prostate cancer. Journal of National Cancer Institute. 2007 in press. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bonkhoff H, Fixemer T, Hunsicker I, Remberger K. Estrogen receptor expression in prostate cancer and premalignant prostatic lesions. Am J Pathol. 1999;155:641–647. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65160-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Glinsky GV, Glinskii AB, Stephenson AJ, Hoffman RM, Gerald WL. Gene expression profiling predicts clinical outcome of prostate cancer. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:913–923. doi: 10.1172/JCI20032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Tomlins SA, et al. Integrative molecular concept modeling of prostate cancer progression. Nat Genet. 2007;39:41–51. doi: 10.1038/ng1935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lapointe J, et al. Gene expression profiling identifies clinically relevant subtypes of prostate cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:811–816. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0304146101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kim JH, et al. Integrative analysis of genomic aberrations associated with prostate cancer progression. Cancer Res. 2007;67:8229–8239. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lapointe J, et al. Genomic profiling reveals alternative genetic pathways of prostate tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 2007;67:8504–8510. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lin B, et al. Prostate-localized and androgen-regulated expression of the membrane-bound serine protease TMPRSS2. Cancer Res. 1999;59:4180–4184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Afar DE, et al. Catalytic cleavage of the androgen-regulated TMPRSS2 protease results in its secretion by prostate and prostate cancer epithelia. Cancer Res. 2001;61:1686–1692. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Vaarala MH, Porvari K, Kyllonen A, Lukkarinen O, Vihko P. The TMPRSS2 gene encoding transmembrane serine protease is overexpressed in a majority of prostate cancer patients: detection of mutated TMPRSS2 form in a case of aggressive disease. Int J Cancer. 2001;94:705–710. doi: 10.1002/ijc.1526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Mertz KD, et al. Molecular characterization of TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusion in the NCI-H660 prostate cancer cell line: a new perspective for an old model. Neoplasia. 2007;9:200–206. doi: 10.1593/neo.07103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]