Abstract

Mechanical characteristics and gas exchange inefficiencies of the lungs contribute to increased work of ventilation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) at rest and exercise, and the energy cost of ventilation is increased in COPD at any external work level. Assuming typical ventilatory variables and respiratory characteristics, we estimated the relative contributions of inspiratory and expiratory resistance, dynamic elastance, intrinsic positive end-expiratory pressure, and gas exchange inefficiency to the work of breathing, finding that the last of these is likely to be of major importance. Dynamic hyperinflation can be seen as both an impediment to inspiratory muscle function and an essential component of adaptation to severe obstruction. Extrinsic restriction, in which the chest wall fails to achieve and maintain abnormally high lung volumes in COPD, can limit ventilatory function and contribute to disability.

Keywords: respiratory mechanics, Campbell diagram, extrinsic restriction, pleural pressure, ventilation

perhaps the most prominent and distressing symptom of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is air hunger, the feeling that one cannot get enough air to breathe. Macklem (19) and others have written of the interplay between a failing lung and the “vital pump,” which must maintain an increased level of pulmonary ventilation at rest despite increased pulmonary impedance and the mechanical disadvantages caused by hyperinflation. When the respiratory muscles are working near their capacity to meet the ventilatory demand, air hunger ensues (23). Hypercapnic respiratory failure results when the muscles can no longer provide sufficient ventilation to meet metabolic demands. In this review, we explore the components of lung mechanics and physiology that are changed by COPD and estimate their effects on the workload and capacity of the respiratory muscles. We will explore the contributions of inspiratory resistance, expiratory resistance, and dynamic elastance of the lung and chest wall to the energy needed to ventilate the lung. We will describe the effects of expiratory flow limitation, which makes the expiratory muscles ineffective and leads to dynamic hyperinflation. Dynamic hyperinflation causes an inspiratory threshold load that increases the work of breathing substantially while it simultaneously reduces the capacity of the inspiratory muscles. In addition, the impaired gas exchange of COPD requires increased total ventilation and thus increased work of ventilation while it reduces the supply of oxygen to the respiratory muscles.

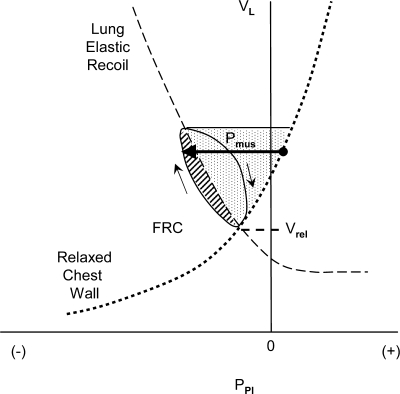

We will show how each one of these factors increases the work required of the respiratory muscles using the pressure-volume plot popularized by E. J. M. Campbell, in which plots of pleural pressure against lung volume reveal the passive characteristics of the lungs and chest wall and show the pressures generated and work performed by the respiratory muscles during breathing (4, 28). Figure 1 shows a Campbell diagram in a subject with normal lungs breathing quietly at rest. The vertical axis shows lung volume (and the corresponding chest wall volume) and the horizontal axis shows pleural pressure as it might be estimated using an esophageal balloon catheter. The pleural pressure minus atmospheric pressure is the pressure drop across the chest wall, which includes the rib cage and the diaphragm-abdomen. Therefore, this pressure-volume plot always pertains to the chest wall. When the airway is open (i.e., when the glottis and mouth are open and there is no equipment attached to the airway), the pressure at the airway opening is atmospheric pressure, and therefore pleural pressure is also the pressure across the lung and upper airway. This pressure difference is therefore the negative of the transpulmonary pressure (−Pl = pleural pressure minus pressure at the airway opening). Note that transpulmonary pressure can be positive or negative, unlike the elastic recoil pressure of the lung (Pel,l = alveolar pressure minus pleural pressure), which is never substantially negative. The solid line and arrows show the path of a complete breath from functional residual capacity (FRC) to an end-inspiratory volume and back again. The elastic characteristic of the lung is shown by the dashed line in Fig. 1. The quasi-static or static pressure-volume characteristic of the lung can be produced by having the subject breathe in or out very slowly (or by having the subject breathe in or out intermittently with an open airway and then connecting the points without airflow). The resistive pressure losses of the lung associated with breathing are seen as departures from this elastic characteristic, the pleural pressure being lower than the elastic pressure during inhalation and higher during exhalation.

Fig. 1.

Campbell diagram in a normal subject showing the volume of lung or chest wall (VL) plotted against pleural pressure (PPl). See text. FRC is functional residual capacity, here equal to Vrel, the relaxation volume of the respiratory system. The continuous line (loop) traces a complete breath from FRC; arrows show direction. The dashed line shows the elastic characteristic of the lung (the negative of elastic recoil pressure), and the dotted line shows the elastic characteristic of the relaxed chest wall. Pmus is pressure change generated by inspiratory muscles (shown by the length of the horizontal arrow). The diagonally hatched area is work done against resistance, and the stippled area is work done against elastance of lung and chest wall.

To estimate the total work done against the combined elastances of lung and chest wall, we need to estimate the pressure-volume characteristic of the relaxed chest wall, which can be produced by having the subject breathe in and then exhale through pursed lips with all respiratory muscles completely relaxed. The dotted line in Fig. 1 shows the relaxation characteristic of the chest wall generated in this way. (This maneuver requires practice, and so a typical relaxation characteristic is often assumed in clinical studies.) In this healthy subject, FRC is located at the relaxation volume (Vrel), which is at the intersection of the elastic pressure-volume curves of the lung (showing −Pl) and relaxed chest wall, where the elastic recoil pressure of the chest wall is equal and opposite to that of the lung.

During spontaneous breathing, the pressure generated by the active chest wall, including its passive elastic elements and muscles, is always equal and opposite to the pressure across the lung and airway, so the pleural pressure vs. lung volume trace describes the lung and the chest wall simultaneously and continuously. Deviations of the pleural pressure from the relaxation characteristic of the chest wall are a measure of respiratory muscle action; this pressure difference is termed Pmus (horizontal arrow in Fig. 1). The work done by respiratory muscles during inhalation is the volume integral of Pmus, shown here as the roughly triangular area bounded by the elastic characteristic of the relaxed chest wall and the pleural pressure trace during the inspiration in Fig. 1. Work done against the resistance of the lung is shown in the diagonally hatched area bounded by the inspiratory pressure-volume trace and the elastic characteristic of the lung. Work done against the elastance of the lung and chest wall is the stippled area bounded by the relaxation characteristics of lung and chest wall from FRC to end inspiration.

Several types of energy are involved in expiration. Energy dissipation by the lung (against resistance) is provided largely by the elastic energy stored in the lung and chest wall during inhalation, as noted above. If expiratory muscles are active, they develop an expiratory Pmus that raises pleural pressure above the recoil pressure of the relaxed chest wall, assisting exhalation. Exhalation is somewhat impeded by the “negative” work done by the inspiratory muscles, which are still generating some force as they lengthen in early exhalation.

In this review we will not calculate work done during exhalation for several reasons. Although expiratory muscles do contract during exhalation in many patients with COPD, and expiratory muscle work certainly contributes to the metabolic cost of breathing (22), the expiratory flow limitation characteristic of COPD usually renders expiratory muscles ineffective at augmenting ventilation. The energy consumed by the inspiratory muscles during their brief lengthening contractions at the start of exhalation is probably negligible, because very little activation is required to produce substantial force in lengthening muscle. Therefore, in what follows, we will focus on inspiratory work: in particular, the inspiratory work done per breath and per minute against pulmonary resistance, dynamic elastance of the lung and chest wall, and the load imposed by dynamic hyperinflation, first in a healthy normal subject and then in a patient with COPD.

EFFECTS OF INCREASED INSPIRATORY RESISTANCE

In normal subjects at rest, work done against lung and chest wall inspiratory resistance is a minor component of the work of breathing. The effective resistance of the relaxed chest wall is caused by pressure-volume hysteresis measured as resistance. Because this measured resistance is small at normal breathing rates (2), it will not be calculated. (Furthermore, because the hysteresis of the relaxed chest wall is largely due to losses in passive muscle, it is unclear how to calculate resistive losses when the muscles are active.) Pulmonary resistance is normally ∼1 cmH2O·l−1·s (6, 12, 16) and comprises airways resistance and the “resistance” of the lung tissue due to energy dissipated by lung tissue during inflation and deflation. In COPD, the pulmonary resistance can increase to 5–15 cmH2O·l−1·s or more (6, 11, 16, 20). The causes of increased inspiratory resistance are well described (15) and include thickening of the bronchial mucosa due to inflammation and edema, inflammatory cell infiltration, mucus gland hyperplasia in larger airways, smooth muscle hypertrophy and inflammatory exudates, and mucus impinging on the airway lumen. In emphysema, there is less mucosal inflammation but greater destruction of small airways and loss of the parenchymal attachments that tether the airways open, increasing flow resistance. To illustrate the effect of increased resistance, let us assume a “standard” breath in a patient with severe COPD with a tidal volume of 500 ml, a breathing frequency of 12 breaths/min, an inspiratory/expiratory (I:E) ratio of 1:4,, and an inspiratory flow rate of 0.5 l/s. Increasing the inspiratory resistance from 1 to 10 cmH2O·l−1·s would increase the resistive work of breathing from 0.25 to 2.5 cmH2O·l per breath (or 3 to 30 cmH2O·l/min at 12 breaths/min).

EFFECTS OF INCREASED ELASTANCE OF LUNG AND CHEST WALL

With each breath, some of the work done by the respiratory muscles is stored as elastic potential energy in the passive elements of the respiratory system. Elastance (1/compliance) of the respiratory system is defined as the change in inflating pressure divided by the change in volume and is the sum of the elastances of the lung and the relaxed chest wall. Elastance can be measured either as static elastance, picking data at times without airflow during an interrupted inflation or deflation of the respiratory system, or dynamic elastance, picking data at the end-expiratory and end-inspiratory instants of zero flow during tidal ventilation. Thus static and dynamic elastance values differ on the basis of volume history. Normal values for chest wall and lung dynamic elastances are typically ∼5 cmH2O/l (1, 20). Thus, for the standard breath described above, the elastic work would be 2.5 cmH2O·l per breath. In COPD, the elastance of the relaxed chest wall is relatively normal or slightly elevated (14, 26) about 5–10 cmH2O/l. The dynamic elastance of the lung can be normal or even low in COPD during quiet breathing. This is due to the fact that the static elastance of the lung is often low in COPD if emphysematous destruction of the lung parenchyma reduces elastic recoil pressure (10). However, dynamic lung elastance can also be increased in COPD, especially during exercise or at rapid breathing rates (1). At increased breathing frequency, a greater fraction of each breath goes to those lung units with relatively low resistance and low compliance (i.e., shorter time constants), resulting in a greater tidal distension of these fast lung units and a higher dynamic elastance. With tachypnea, dynamic elastance of the lung can increase 10-fold or more (20). Sliwinski et al. (30) calculated the elastic work of breathing in patients with COPD and found dynamic lung elastance to increase from 3.7 to 5.9 cmH2O/l as subjects made the transition from resting breathing to exercise. If we assume a chest wall elastance of 7 cmH2O/l and a dynamic lung elastance of 7 cmH2O/l at a frequency of 12 breaths/min, the elastic work done in a 500 ml breath is 3.5 cmH2O·l per breath or 42 cmH2O·l/min. Sliwinski et al. (30) reported that work done against the elastance of lung and chest wall in COPD is ∼3 cmH2O·l per breath at rest.

EFFECTS OF INCREASED EXPIRATORY RESISTANCE

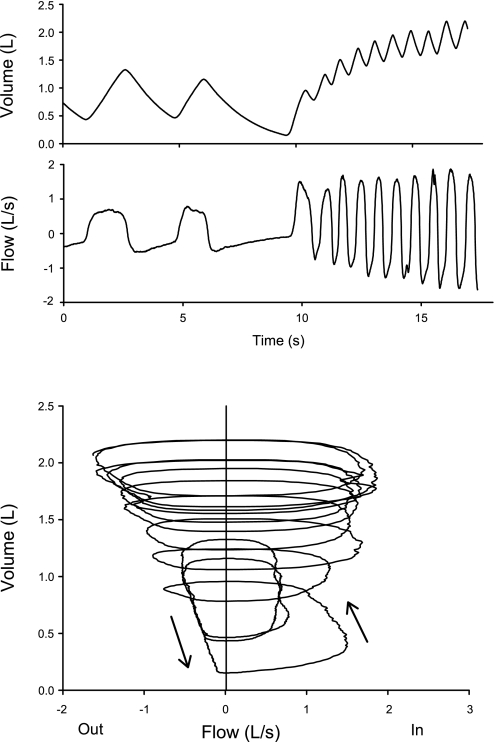

As stated above, the work done by expiratory muscles during exhalation will not be calculated. However, high expiratory flow resistance and expiratory flow limitation (27) are critical, because they cause dynamic hyperinflation when the inhaled tidal volume exceeds the volume that can be exhaled during the time of expiration. A temporary inequality of the inhaled and exhaled volumes results in an increase in end-expiratory lung volume (FRC), which increases expiratory flow rates, restoring a new steady-state. Dynamic hyperinflation is demonstrated in Fig. 2 in a subject with severe COPD as he voluntarily begins to breathe at a high respiratory rate.

Fig. 2.

Dynamic hyperinflation at the onset of voluntary rapid breathing in a patient with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Top traces are volume change and flow, measured with a pneumotachograph, vs. time. The lower trace is a flow-volume trace of the same data. The subject is initially flow limited during quiet breathing, and with hyperpnea, lung volume increases until a new steady state is achieved at the higher lung volume, where expiratory flows are greater than at the initial FRC. See text.

EFFECTS OF DYNAMIC HYPERINFLATION ON WORK

Ventilatory limitation in COPD is largely a function of expiratory flow limitation, which may prevent the lungs from emptying to the relaxation volume during breathing. Because the maximum expiratory flow rate decreases monotonically with decreasing lung volume, the degree of expiratory flow limitation during breathing depends on the lung volume range over which breathing occurs. Dynamic hyperinflation not only hinders ventilation by decreasing the inspiratory capacity of the chest wall and increasing the elastic load of breathing, it also facilitates exhalation by increasing maximum expiratory flow rates and thus increases the ventilatory capacity of the lungs (Fig. 2). Dynamic hyperinflation is essential for maintaining ventilation in the face of severe expiratory flow limitation.

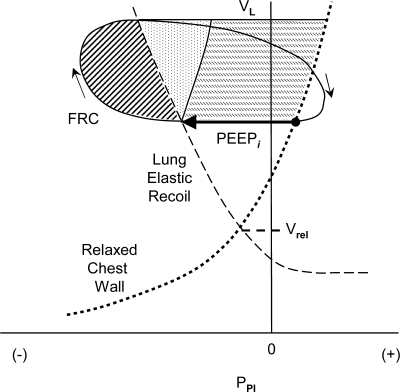

Dynamic hyperinflation is present in many COPD patients breathing at rest, and it increases with the hyperpnea of exercise (9, 24). Sliwinski et al. (30) explored the significance of dynamic hyperinflation to the elastic work of breathing in a group of subjects with COPD. They estimated that during exercise, the volume of dynamic hyperinflation increases 350 ml. Dynamic hyperinflation is accompanied by dynamic intrinsic positive end-expiratory pressure (dynamic PEEPi), which can be described as a positive end-expiratory alveolar pressure that is not extrinsically applied. When inhalation is initiated from a volume above relaxation volume, the inspiratory muscles must lower pleural pressure substantially (by PEEPi) before alveolar pressure becomes subatmospheric to initiate inspiratory flow (Fig. 3). Dynamic PEEPi thus represents an inspiratory threshold load that must be overcome to initiate inhalation and which adds to the Pmus required throughout the breath (Fig. 3). Sliwinski et al. (30) found that PEEPi increases from 2.5 to 6 cmH2O during the transition from rest to exercise, and concluded that the elastic work done to overcome PEEPi is a major component of the elastic work of breathing in COPD. In healthy subjects, there is no dynamic hyperinflation at rest, and increased expiratory muscle activity during exercise normally decreases FRC, facilitating inspiratory muscle action (13). In patients with COPD during a 500-ml breath, a PEEPi of 4 cmH2O at rest (corresponding to a dynamic hyperinflation of ∼400 ml with a respiratory elastance of 10 cmH2O/l) would increase the work of breathing by 2 cmH2O·l per breath or 24 cmH2O·l/min.

Fig. 3.

Campbell diagram to illustrate the effects of dynamic hyperinflation on inspiratory muscle work. FRC is increased above relaxation volume. PEEPi is the intrinsic positive end-expiratory pressure that must be overcome before inspiratory flow can begin (shown as the length of the horizontal arrow). Other abbreviations as in Fig. 1. Diagonally hatched area is work done against resistance, stippled area is work done against elastance of lung and chest wall, and horizontally hatched area is work to overcome PEEPi. (In this illustration, work done against inspiratory resistance is increased from that shown in Fig. 1, but elastic characteristics of lung and chest wall are unchanged.)

In COPD, dynamic hyperinflation not only increases the work done during inspiration, it profoundly reduces the capacity of the inspiratory muscles to generate force and shorten, decreasing the ventilatory reserve capacity and increasing the sense of effort and dyspnea (25). These ideas will be covered in the subsequent section (7).

EFFECTS OF DECREASED GAS EXCHANGE EFFICIENCY

Finally, we consider the diminished gas exchange efficiency of the lung in COPD, which results in increased ventilatory requirements at rest and exercise that increase respiratory muscle work. Inhomogeneities of ventilation and perfusion result in alveolar dead space that increases the total ventilation required to maintain eucapnia. Relatively underventilated regions cause alveolar hypoxia and hypoxemia. These effects, especially in combination, cause increased respiratory drive, and air hunger will ensue if ventilation cannot be increased. When resting or exercising at a given external work rate, patients with COPD must increase ventilation to approximately one and one half times normal (8). Gas exchange inefficiency then is an important contributor to increased ventilatory work (29). In the simplest analysis, work done against inspiratory resistance and respiratory elastance are roughly proportional to the changes in flow rate and tidal volume, respectively, so increases in tidal volume and respiratory rate would increase inspiratory work proportionately. However, the increased respiratory rate is likely to increase dynamic elastance substantially due to the frequency dependency of elastance. Furthermore, any increase in ventilation will cause an increase in the volume of dynamic hyperinflation, increasing its contribution to the elastic work (21).

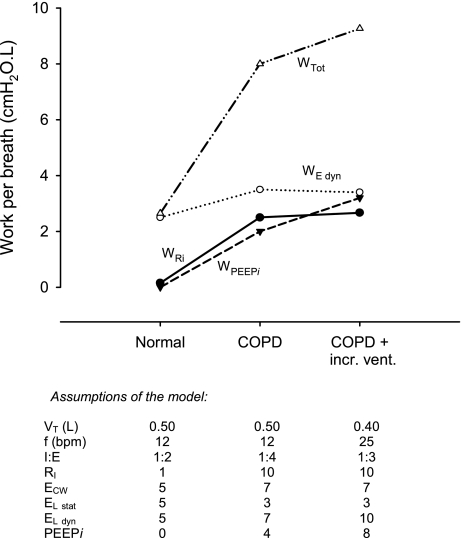

To illustrate how an increase in ventilation could affect ventilatory work in COPD, let us assume that resting tidal volume decreases from 500 to 400 ml, breathing frequency increases from 12 to 25 breaths/min, and I:E ratio decreases from 1:4 to 1:3, increasing total ventilation by 67% and inspiratory flow rate by 33%, and increasing dynamic elastance of the lung from 7 to 10 cmH2O/l. We also assume that the volume of dynamic hyperinflation increases from 400 to 800 ml, causing a dynamic PEEPi of 8 cmH2O. With these assumptions, inspiratory work per breath done against resistance increases to 2.7 cmH2O·l, work done against dynamic elastance decreases slightly to 3.4 cmH2O·l, and work done to overcome PEEPi increases to 3.2 cmH2O·l.

Figure 4 summarizes the calculations above, showing contributions of the components of respiratory work during the standard breath for a normal subject, a patient with COPD breathing at a normal rate, and for the COPD patient at increased ventilation caused by gas exchange inefficiency. In the normal subject, the work done against elastance predominates. In the COPD patient, resistive pressure losses become important. The work to overcome PEEPi becomes substantial at rest and increases disproportionately with increased ventilation. The requirement for increased ventilation in COPD greatly increases the work of breathing at rest. In this example of a patient with severe COPD, therefore, the work of breathing at rest becomes 9.3 cmH2O·l per breath (3.5 times normal) or 232 cmH2O·l/min (7 times normal).

Fig. 4.

Work of breathing during one breath in a normal subject, a patient with COPD, and a patient with COPD with increased ventilation due to gas exchange inefficiency. Work was calculated using assumptions in the text, listed below. WTot is total work per breath, WE dyn is work done against dynamic elastance of the lung and chest wall; WPEEPi is work done against intrinsic positive end-expiratory pressure, and WRi is work done against inspiratory resistance of the lung. Vt, tidal volume; f, respiratory frequency; bpm, breaths/min; I:E, inspiratory:expiratory ratio; Rl, resistance of the lung; ECW, elastance of the chest wall; El,stat, static elastance of the lung; El,dyn, dynamic elastance of the lung.

EXTRINSIC RESTRICTION

Just as lung disease can increase the requirements for the respiratory muscles and limit their capacity to ventilate the lungs, so inability of the chest wall to breathe at increased volumes can reduce the ventilatory function of the lungs in COPD, compounding ventilatory dysfunction. Such ventilatory limitation imposed by nonpulmonary causes has been called extrinsic restriction (17).

From the lung's point of view, anything that limits chest expansion, such as inspiratory muscle weakness, obesity, or the presence within the thorax of a space-occupying lesion (e.g., hydrothorax or a nonventilated emphysematous bulla), reduces expiratory flow rates in general and worsens obstruction in COPD. For example, in single lung transplantation for emphysema, a relatively normal transplanted lung can be rendered ineffective by hyperexpansion of the native emphysematous lung, which keeps the allograft small (restricts it), reducing expiratory flow rates (5, 17). When, after lung transplantation, there is a decrease in the ability of the chest wall to expand, the resulting extrinsic restriction of the lungs contributes to respiratory dysfunction (18). A counterexample to extrinsic restriction is lung volume reduction surgery, in which the remaining lung is more inflated (less restricted). Bellemare et al. (3) found that after lung volume reduction surgery, improvements in symptoms were correlated with changes in diaphragm length and lung volume, consistent with improvements in functional restriction. These ideas point to the importance of the synergism between the chest wall and the lungs in determining respiratory function and dysfunction, as developed in a subsequent review article of this Highlighted Topic series (7a).

GRANTS

This work was supported in part by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant HL-52586.

REFERENCES

- 1.Attinger EO, Segal MS. Mechanics of breathing. I. The physical properties of the lung. Am Rev Respir Dis 80: 38–45, 1959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barnas GM, Yoshino K, Stamenovic D, Kikuchi Y, Loring SH, Mead J. Chest wall impedance partitioned into rib cage and diaphragm-abdominal pathways. J Appl Physiol 66: 350–359, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bellemare F, Cordeau MP, Couture J, Lafontaine E, Leblanc P, Passerini L. Effects of emphysema and lung volume reduction surgery on transdiaphragmatic pressure and diaphragm length. Chest 121: 1898–1910, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Campbell EJM The Respiratory Muscles and the Mechanics of Breathing. Chicago, IL: Year Book, 1958.

- 5.Cheriyan AF, Garrity ER Jr, Pifarre R, Fahey PJ, Walsh JM. Reduced transplant lung volumes after single lung transplantation for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 151: 851–853, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chiang ST, Green J, Wang WF, Yang YJ, Shiao GM, King SC. Measurements of components of resistance to breathing. Chest 96: 307–311, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Troyer A, Wilson TA. Effect of acute inflation on the mechanics of the inspiratory muscles. J Appl Physiol (March 5, 2009). doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.91472.2008. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7a.Estenne M Effect of lung transplant and volume reduction surgery on respiratory muscle function. J Appl Physiol (April 9, 2009). doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.91620.2008. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Evison H, Cherniack RM. Ventilatory cost of exercise in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Appl Physiol 25: 21–27, 1968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferguson GT Why does the lung hyperinflate? Proc Am Thoracic Soc 3: 176–179, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Finucane KE, Colebatch HJ. Elastic behavior of the lung in patients with airway obstruction. J Appl Physiol 26: 330–338, 1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frank NR, Mead J, Ferris BG Jr. The mechanical behavior of the lungs in healthy elderly persons. J Clin Invest 36: 1680–1687, 1957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frank NR, Mead J, Whittenberger JL. Comparative sensitivity of four methods for measuring changes in respiratory flow resistance in man. J Appl Physiol 31: 934–938, 1971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grimby G, Goldman M, Mead J. Respiratory muscle action inferred from rib cage and abdominal V-P partitioning. J Appl Physiol 41: 739–751, 1976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guerin C, Coussa ML, Eissa NT, Corbeil C, Chasse M, Braidy J, Matar N, Milic-Emili J. Lung and chest wall mechanics in mechanically ventilated COPD patients. J Appl Physiol 74: 1570–1580, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hogg JC, Chu F, Utokaparch S, Woods R, Elliott WM, Buzatu L, Cherniack RM, Rogers RM, Sciurba FC, Coxson HO, Pare PD. The nature of small-airway obstruction in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med 350: 2645–2653, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ingenito EP, Evans RB, Loring SH, Kaczka DW, Rodenhouse JD, Body SC, Sugarbaker DJ, Mentzer SJ, DeCamp MM, Reilly JJ Jr. Relation between preoperative inspiratory lung resistance and the outcome of lung-volume-reduction surgery for emphysema. N Engl J Med 338: 1181–1185, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Loring SH, Leith DE, Connolly MJ, Ingenito EP, Mentzer SJ, Reilly JJ Jr. Model of functional restriction in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, transplantation, and lung reduction surgery. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 160: 821–828, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Loring SH, Mentzer SJ, Reilly JJ. Sources of graft restriction after single lung transplantation for emphysema. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 134: 204–209, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Macklem PT Respiratory muscles: the vital pump. Chest 78: 753–758, 1980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mead J, Lindgren I, Gaensler EA. The mechanical properties of the lungs in emphysema. J Clin Invest 34: 1005–1016, 1955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mead J, Whittenberger JL. Physical properties of human lungs measured during spontaneous breathing. J Appl Physiol 5: 779–796, 1953. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ninane V, Rypens F, Yernault JC, De Troyer A. Abdominal muscle use during breathing in patients with chronic airflow obstruction. Am Rev Respir Dis 146: 16–21, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O'Donnell DE, Bertley JC, Chau LK, Webb KA. Qualitative aspects of exertional breathlessness in chronic airflow limitation: pathophysiologic mechanisms. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 155: 109–115, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.O'Donnell DE, Revill SM, Webb KA. Dynamic hyperinflation and exercise intolerance in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 164: 770–777, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O'Donnell DE, Webb KA. The major limitation to exercise performance in COPD is dynamic hyperinflation. J Appl Physiol 105: 753–755; discussion 755–757, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ranieri VM, Giuliani R, Mascia L, Grasso S, Petruzzelli V, Bruno F, Fiore T, Brienza A. Chest wall and lung contribution to the elastic properties of the respiratory system in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur Respir J 9: 1232–1239, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rodarte JR, Rehder K. Dynamics of respiration. In: Handbook of Physiology. The Respiratory System. Mechanics of Breathing. Bethesda, MD: Am. Physiol. Soc., 1986, sect. 3, vol. III, pt. 1, chapt. 10, p. 131–144.

- 28.Roussos C, Campbell EJM. Respiratory muscle energetics. In: Handbook of Physiology. The Respiratory System. Mechanics of Breathing. Bethesda, MD: Am. Physiol. Soc., 1986, sect. 3, vol. III, pt. 2, chapt. 28, p. 481–509.

- 29.Scano G, Grazzini M, Stendardi L, Gigliotti F. Respiratory muscle energetics during exercise in healthy subjects and patients with COPD. Respir Med 100: 1896–1906, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sliwinski P, Kaminski D, Zielinski J, Yan S. Partitioning of the elastic work of inspiration in patients with COPD during exercise. Eur Respir J 11: 416–421, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]