Abstract

Women have lower circulating catecholamine levels during metabolic perturbations, such as exercise or hypoglycemia, but similar rates of systemic lipolysis. This suggests women may be more sensitive to the lipolytic action of catecholamines, while maintaining similar glucoregulatory effects. The aim of the present study, therefore, was to determine whether women have higher rates of systemic lipolysis compared with men in response to matched peripheral infusion of catecholamines, but similar rates of glucose turnover. Healthy, nonobese women (n = 11) and men (n = 10) were recruited and studied on 3 separate days with the following infusions: epinephrine (Epi), norepinephrine (NE), or the two combined. Tracer infusions of glycerol and glucose were used to determine systemic lipolysis and glucose turnover, respectively. Following basal measurements of substrate kinetics, the catecholamine infusion commenced, and measures of substrate kinetics continued for 60 min. Catecholamine concentrations were similarly elevated in women and men during each infusion: Epi, 182–197 pg/ml and NE, 417–507 pg/ml. There was a significant sex difference in glycerol rate of appearance and rate of disappearance with the catecholamine infusions (P < 0.0001), mainly due to a significantly greater glycerol turnover during the first 30 min of each infusion: glycerol rate of appearance during Epi was only 268 ± 18 vs. 206 ± 21 μmol/min in women and men, respectively; during NE, only 173 ± 13 vs. 153 ± 17 μmol/min, and during Epi+NE, 303 ± 24 vs. 257 ± 21 μmol/min. No sex differences were observed in glucose kinetics under any condition. In conclusion, these data suggest that women are more sensitive to the lipolytic action of catecholamines, but have no difference in their glucoregulatory response. Thus the lower catcholamine levels observed in women vs. men during exercise and other metabolic perturbations may allow women to maintain a similar or greater level of lipid mobilization while minimizing changes in glucose turnover.

Keywords: sex differences, glucose kinetics, glycerol kinetics

consistent and significant differences have been observed between women and men in their catecholamine response to metabolic stress. During exercise, or insulin-induced hypoglycemia, circulating levels of epinephrine and, in some instances, norepinephrine, do not rise to the same extent in women compared with men (4, 12, 13, 15, 23, 25, 26, 37, 56–58). A lesser increase in muscle sympathetic nerve activity has also been observed in women during hypoglycemia (12–14). Such observations are unlikely due to a sex difference in the “threshold” at which a catecholamine response is elicited. For example, during insulin-induced hypoglycemia, it has been demonstrated that the level of blood glucose required to elicit a significant counterregulatory response is the same in women and men; rather, the magnitude of the response is reduced in women (14). In addition, maintenance of the same euglycemia in women and men during exercise, via exogenous glucose infusion, still results in the sex-based differences in catecholamine levels (15). Data suggest that the lower sympathetic response to hypoglycemia in women may be due to estrogen decreasing central sympathetic drive (51, 52). Despite a lower sympathetic response during metabolic stress, women have similar, or greater, increases in circulating concentrations of glycerol and nonesterified fatty acids (NEFA; venous or arterialized measurements) (4, 13, 15, 25, 37, 56). Greater systemic rates of glycerol and NEFA appearance have also been reported (4, 18, 23, 36, 58). Interestingly, these sex differences in the catecholamine response to exercise, and differences in lipid kinetics, are not observed in more elite athletes (46, 48). Nevertheless, these data suggest that, for the majority of women, the lipolytic sensitivity to the action of catecholamines may be increased relative to men.

From the observations presented above, it might be expected that, during a matched infusion of catecholamines, women would show a greater lipolytic response compared with men. To date, however, there is very limited and inadequate data in this area. Jensen et al. (29) determined NEFA kinetics in women vs. men during a 2-h infusion of Epi and observed no sex difference in NEFA rate of appearance (Ra) with measurements made over the final 60 min of the infusion. With this study design, however, significant tachyphlaxia of the β-adrenergic receptors likely occurred by the time lipid kinetics were measured (60 min after the onset of the infusion) (1), thus potentially obscuring any sex difference. Weber and McDonald (61) measured substrate concentrations rather than substrate kinetics in response to incremental doses of Epi (10-min duration each dose) and observed no sex difference on glycerol or NEFA concentrations. An incremental study design for hormone infusion is problematic, however, due to potential effects of the preceding dose on the response to the subsequent dose. It is noteworthy that neither of these studies controlled for hormonal status in women, nor gave any indication of habitual activity patterns or prestudy exercise of subjects, all factors that can potentially, independently, impact catecholamine action and/or sensitivity.

In addition to effects on lipid mobilization, catecholamines also stimulate glucose production by the liver and cause a decrease in glucose utilization at the periphery, predominantly in muscle (43, 44, 50). Effects on glucose production are due to direct and indirect actions (8, 9), as catcholamines can directly stimulate glycogenolysis (10), but also indirectly increase gluconeogenesis via delivery of lipolytic by-products, glycerol and NEFAs (8, 10), as well as lactate (i.e., increased precursor delivery). Although some increase in insulin can occur as a result of the increase in glucose production and concentration that results from an elevation in catecholamines, this is limited due to the inhibition of insulin secretion by epinephrine and norepinephrine (11, 45). Furthermore, the small increase in insulin that can occur is, for the most part, insufficient to inhibit the effect of epinephrine on lipolysis (3). Of relevance, when tested in the overnight fasted state, women have been reported to have a lower glucose production in response to moderately intense exercise of >30 min (26, 46), coincident with a lower catecholamine response.

The aim of the present study, therefore, was to determine if there are sex differences in lipolysis, but not glucose production, in response to submaximal doses of Epi, NE, or the two combined. It was hypothesized that, for the same submaximal dose of Epi and/or NE, women would have a greater rate of systemic lipolysis, but a similar rate of glucose production, compared with men. It was further hypothesized that there would be a synergistic effect of the Epi + NE combination in women only, such that lipolysis would be greater than the sum of the two hormones infused individually.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

Normal weight, healthy women and men (20–45 yr) were recruited for the study (Table 1). Female subjects were premenopausal, eumenorrheic, and not using hormonal contraceptives. Medical exclusions included past or present history of cardiovascular disease, high blood pressure, diabetes, any hormonal imbalance or metabolic abnormality, and use of oral contraceptives or other hormones. Participants could be habitually active, but were not highly trained (≤30 min of mild- to moderate-intensity exercise/day). A total of 21 subjects (11 women, 10 men) took part in the study. Subject characteristics are shown in Table 1. The study protocol was approved by the University of Colorado Committee Institutional Review Board for the Protection of Human Subjects. All subjects read and signed an informed consent form before admission into the study.

Table 1.

Subject characteristics

| Women | Men | |

|---|---|---|

| n | 11 | 10 |

| Age, yr | 30±8 | 29±7 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 21.7±1.7 | 23.5±1.6 |

| Body weight, kg | 59.4±5.0* | 74.0±7.6 |

| Body fat, % | 24.0±1.7† | 19.1±1.3 |

| Fat mass, kg | 14.3±2.3 | 14.3±3.9 |

| Fat-free mass, kg | 45.1±3.9* | 59.7±5.4 |

| HOMA-IR | 0.74+0.47 | 0.84+0.37 |

Values are means ± SD; n, no. of subjects. BMI, body mass index; HOMA-IR, homeostasis model of insulin resistance [fasting glucose (mg/dl)/fasting insulin (μU/ml)]/405 (34).

Women lower than men, and

women higher than men: P < 0.0001.

Preliminary assessments.

A health and physical examination was completed on all subjects, including blood and urine analysis, to confirm there was no medical reason for exclusion. Resting metabolic rate (RMR) was measured using indirect calorimetry via a metabolic cart system (Sensormedics 2900, Sensormedics, Yorba Linda, CA). Oxygen (O2) consumption and carbon dioxide (CO2) production were used to calculate metabolic rate (30, 54). This RMR value was used to determine energy intake of subjects during the period of prestudy diet control. Body composition was determined via dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (Lunar, Madison, WI) (41).

Prestudy diet and exercise control.

Subjects were fed a controlled diet for 2 days before each study day. All food was prepared by the General Clinical Research Center (GCRC) diet kitchen at the University of Colorado, and subjects were required to consume breakfast in the GCRC with other food prepared to take away. No other food was permitted, and subjects were required to consume all of the food given. The only optional part of the diet was two food modules (200 kcal each, same composition as the overall diet), one or both of which the subjects could eat, if they were hungry. The diet composition was 25% fat, 15% protein, and 60% carbohydrate (CHO), and initial energy intake was calculated at 1.6–1.75 × RMR, based on subjects' self-reported habitual activity level. Subjects were allowed to follow their usual activity routine for the first day of the diet, and on the second day they refrained from any planned exercise. The aim of the diet control was to minimize within- and between-subject variation in the degree of energy and CHO (glycogen) balance. In women and men, the average energy intake was 50 and 51 kcal/kg fat-free mass (FFM), respectively.

Study Days

Subjects stayed overnight at the GCRC the evening before each study. Between 1900 and 2000, subjects consumed their evening meal. After this, subjects remained fasted until the end of the study the following day. Women were studied in the follicular phase of the menstrual cycle, which was confirmed by measurement of serum estrogen and progesterone levels measured on the day of the study (progesterone had to be <2.5 ng/ml).

Determination of glycerol and glucose kinetics.

On the study day, intravenous catheter placement occurred between 6:45 and 7:30 AM. An infusion intravenous catheter was placed in an antecubital vein for delivery of stable isotopes. In the contralateral arm, a sampling catheter was placed retrograde fashion into a dorsal hand vein, or, if necessary, into a wrist vein. The heated hand technique (35) was used to obtain arterialized blood samples. Initial blood samples were drawn for determination of background enrichment followed by a primed (2 μmol/kg), constant (0.09 μmol·kg−1·min−1) infusion of [1,1,2,2,3-2H5]glycerol (Cambridge Isotopes, Andover, MA) and a primed (17.6 μmol/kg), constant (0.2 μmol·kg−1·min−1) infusion of [6,6-2H2]glucose. All infusates were prepared by the Research Pharmacist at University Hospital, University of Colorado Health Sciences Center, and were tested for sterility and pyrogenicity before use. Resting substrate kinetics were determined on blood samples taken over the last 30 min of a 120-min rest phase (time t = 90, 100, 110, and 120 min). The catecholamine infusion was then started and continued for 60 min up to 180 min. Catecholamines were diluted in 0.9% saline containing 1 mg/ml ascorbic acid, to prevent oxidation. The infusion rate of Epi alone was 8 ng·kg−1·min−1; the infusion of NE alone was 8 ng·kg−1·min−1 in the first four subjects (2 men and 2 women), and 14 ng·kg−1·min−1 in the remaining subjects. This increase in NE infusion rate occurred as the circulating NE levels observed in the first four subjects were found to be below the target level (similar to levels observed with moderate exercise, ∼500 pg/ml). The infusion rate of the Epi and NE combined was the same as when administered individually. These infusion rates were selected to achieve circulating catecholamine levels similar to those observed during moderate exercise. At the onset of the catecholamine infusion, the infusion rate of the glycerol was increased to 1.3 × rest in an attempt to avoid large fluctuations in tracer enrichment due to increased substrate turnover. Blood samples were drawn at t = 130, 140, 150, 160, 170, and 180 min during the hormone infusion for the measurement of isotope enrichments and glycerol and glucose concentrations.

Blood pressure and heart rate measurement.

Heart rate and blood pressure were monitored by an automatic blood pressure cuff placed on the arm used for sampling. Measurements were made immediately after the blood draws at t = 0 and t = 120 and immediately after each blood draw during the catecholamine infusions (t = 130, 140, 150, 160, 170, and 180 min).

Respiratory gas exchange.

In the 30 min before blood sampling at rest, a 15- to 20-min measurement of respiratory gas exchange was made via indirect calorimetry (Sensormedics 2900, Sensormedics, Yorba Linda, CA). During each hormone infusion, a 20-min measurement of respiratory gas exchange was performed 25–30 min after the start of the hormone infusion. CHO and fat oxidation were calculated from the volume of O2 consumed and volume of CO2 expired after correcting for protein oxidation (30, 54). Protein oxidation was estimated from urinary nitrogen excretion with urine collected over the study period.

Determination of circulating hormone and substrate levels.

Measurements of glycerol and glucose were made on all blood samples. Catecholamines, insulin, and glucagon were measured on samples drawn at 0, 100, and 120 min of rest and at 140, 160, and 180 min of the catecholamine infusion. Two to three milliliters of blood were added to EDTA tubes for the measurement of tracer enrichment and plasma substrate concentrations. Two and one-half milliliters of whole blood were added to 40 μl of preservative (3.6 mg EGTA plus 2.4 mg glutathione in distilled water), for plasma catecholamine determinations. Blood for glucagon measurement (2 ml) was added to tubes containing EDTA plus 500 kallikrein inhibiting units of aprotinin. Samples were immediately placed on ice then spun, and plasma was separated. Approximately 2.5- to 3.5-ml whole blood were allowed to clot, and the serum separated off after spinning. This was used for determination of the remaining hormone and substrate concentrations. All plasma, serum, and supernatant samples were stored at −70°C until analysis. Plasma samples were analyzed for glycerol and glucose enrichment and concentration. Catecholamines were determined in duplicate by high-performance liquid chromotography with electrochemical detection [intra-assay coefficient of variation (CV) 5.4% epinephrine, 4.5% norepinephrine] (6). Plasma samples were used for enzymatic assays of NEFA (Wako Chemical USA, Richmond, VA; intra-assay CV 1.2%). Radioimmunoassays were used to determine serum insulin (Kabi Pharmacia, Piscataway, NJ), progesterone, estradiol (Diagnostic Products, Los Angeles, CA), and glucagon (Linco Research, St. Louis, MO). Samples were run in duplicate with intra-assay CVs of 5.2, 7.5, 6.0, and 8.0%, respectively. Within subjects, samples from each study day were run in the same batch.

Determination of glycerol and glucose isotope enrichment and concentration.

These were measured via gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS; GC models 6890 and 5973N, Agilent, Palo Alto, CA). The pentacetate derivative of glycerol and glucose were generated as follows. Samples were deproteinized with iced ethanol, and the supernatant was dried in a speedvac at 50°C for 2.5 h. Samples were then derivatized using 100 μl of acetic anhydride-pyridine solution (1:1) and heated for 30 min at 100°C. One hundred microliters of ethyl acetate were then added, and the samples were vortexed and transferred to GC-MS vials for analysis. Injector temperature of the GC-MS was set at 250°C, and initial oven temperature was set at 150°C. The column used was an Agilent HP-5MS 0.25 mm * 30 m with a 0.25-mm film thickness. Oven temperature was increased 30°C/min until a final temperature of 250°C was achieved. Helium was used as the carrier gas with a 20:1 ml/min pulsed split injection ratio. Transfer line temperature was set at 280°C, source temperature at 250°C, and quadruple temperature at 150°C, and methane chemical ionization (63) was used to monitor selective ions with mass-to-charge ratios of 159 (M + 0 from natural glycerol), 164 (M + 5 from [1,1,2,2,3-2H5]glycerol), and 162 (M + 3 from the [1,2,3-13C3]glycerol internal standard) for glycerol, and 331 (M + 0 from natural glucose), 333 (M + 2 from [6,6-2H2]glucose), and 337 (M + 6 from the [U-13C]glucose, internal standard) for glucose.

Natural glycerol standards were prepared from 5.4–1,087 μmol/l and spiked with 105 μmol/l of the internal standard [1,2,3-13C3]glycerol to generate the glycerol standard curve for determining glycerol concentration. The calibration curve was constructed by comparing the known ratio of glycerol: [1,2,3-13C3]glycerol to the measured area ratio of 159:162. Natural glycerol in the samples was then determined by measuring the sample 159:162 area ratio and using the linear equation obtained from the calibration curve to calculate the natural glycerol concentration in micromoles per liter. For the glucose calibration curve, natural glucose standards from 10 to 200 mg/dl were prepared and spiked with 80 μg [U-13C]glucose. The calibration curve was constructed by comparing the known ratio of glucose-[U-13C]glucose to the measured area ratio of 331:337. Natural glucose concentration in the samples was then determined by measuring the sample 331:337 area ratio and using the linear equation obtained from the calibration curve to calculate the natural glucose concentration in milligrams per deciliter.

Calculations.

|

|

where Ra is for the tracee (μmol/min), F is infusion rate of tracer (μmol/min), pV is effective volume of tracee distribution (230 ml/kg body wt for glycerol and 100 ml/kg body wt for glucose) (47, 55), t1 is time 1 of sampling, t2 is time 2 of sampling, C1 is tracee concentration at t1, C2 is tracee concentration at t2, E1 is tracer enrichment (tracer-to-tracee ratio) at t1, E2 is enrichment at t2, and Rd is rate of disappearance.

Data Analysis

Subject characteristics were compared using an unpaired t-test. For substrate concentrations and kinetics, data were analyzed using a general linear multivariate model with repeated measurements. This was used to evaluate differences in the pattern of the time course of response between the sexes on each study day. In this model, time was included as the repeated within-subject factor, and between-subject factors included sex (male or female) and infusion (Epi, NE, or Epi + NE). The model evaluated two- way interactions (time × sex and time × infusion), as well as any three-way interaction (time × sex × infusion). Post hoc analyses were performed using Bonferroni's test. Data from one female subject were excluded on the Epi infusion day as the infusate did not include the Epi (as evidenced by no change in circulating Epi levels). For the glucose kinetic data, one man and one woman had to be excluded due to analytic problems during sample analysis. Another woman was excluded from this data set, as her glucose turnover rates were 3 SDs above the group mean for no apparent reason.

For glycerol concentration and kinetics, there was a clear change in the pattern of response from rest, to the first 30 min of the hormone infusion (t 130–150 min) and then the last 30 min of infusion (t 160–180 min). Physiologically, this may be explained by the onset of tachyphylaxia of the adrenergic β-receptors ∼30 min into the catecolamine infusion. Therefore, data over these time periods were averaged and further compared between the sexes and study days. For catecholamines, insulin, and glucagon, values for the entire 60-min infusion were averaged and compared with average rest values.

Data for glycerol kinetics were expressed in absolute rates, as well as relative to body weight, the more traditional method of data presentation. As adipose tissue is the major site of lipolysis, it could be considered that expressing data relative to fat mass, or statistically covarying for fat mass, may be the best approach for comparing glycerol Ra. This was not necessary, however, as the men and women in this study had identical fat masses, and the difference in body weight was purely due to differences in FFM. For glucose kinetics, we expressed data in terms of body weight and FFM, as organs (liver and kidney) are the source of glucose production in the body, and lean tissue mass the main sight of glucose disposal. Results are presented as means ± SE, with statistical significance set at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Hormone Concentrations

At rest, women and men had similar epinephrine levels, but women had significantly lower norepinephrine concentrations compared with men (P < 0.0001 Table 2). Circulating catecholamine levels increased significantly above resting values, as expected, for the corresponding catecholamine infusion (P < 0.0001). For the Epi or Epi + NE infusion, circulating epinephrine increased to similar levels in women and men, ∼5.9- to 6.8-fold above resting levels. Circulating norepinephrine during the NE or combined Epi + NE infusions was still lower in women vs. men, but the change from rest was not significantly different; an increase of 356 ± 35 vs. 359 ± 28 pg/ml during NE infusion, and an increase of 307 ± 35 vs. 346 ± 25 pg/ml during the combined Epi + NE infusion. By 10 min of each catecholamine infusion, the concentration of epinephrine was between −2 and 15 pg/ml of the final 60-min value, and the corresponding values for norepinephrine were between −30 and 44 pg/ml. These differences are within the analytic error range for HPLC analysis and demonstrate a rapidly achieved steady state for the infused hormone levels.

Table 2.

Circulating catecholamine levels at rest and during hormone infusion for each study day

| Epi |

NE | Epi + NE | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [Epi] | [NE] | [Epi] | [NE] | [Epi] | [NE] | |

| Before infusion | ||||||

| Women | 29±6 | 92±14a | 28±6 | 105±8a | 31±4 | 110±12a |

| Men | 30±4 | 145±14 | 32±4 | 151±18 | 30±4 | 139±11 |

| During infusion c | ||||||

| Women | 193±18d | 99±13b | 31±5 | 461±29b,e | 183±14d | 417±35b,e |

| Men | 188±11d | 154±16 | 31±4 | 507±31e | 197±16d | 485±29e |

Values are means ± SE in pg/ml. Epi, epinephrine infusion only; NE, norepinephrine infusion; Epi + NE, combined epinephrine + norepinephrine infusion; [Epi], circulating Epi concentration; [NE], circulating NE concentration. Significant main effect of sex:

P < 0.0001,

P < 0.01.

Significant main effect of infusion on both circulating [Epi] and [NE]: P < 0.0001.

Post hoc analysis: [Epi] greater during Epi and Epi +NE infusions vs. NE alone: P < 0.0001.

[NE] greater during NE and Epi +NE infusions vs. Epi alone: P < 0.0001.

Insulin concentrations did not change significantly from rest with any of the catecholamine infusions. Resting values in women averaged 3.7–4.1 μU/ml on the 3 study days and 3.3–4.7 μU/ml during the catecholamine infusions. In men, the corresponding values were 4.0–4.3 μU/ml at rest and 4.0–5.1 μU/ml with the infusions. Glucagon levels were also stable during the study. Average values for each study day at rest were 54–55 pg/ml in women, 60–63 pg/ml in men, and during infusions 53–56 pg/ml and 61–62 pg/ml, respectively.

Blood Pressure and Heart Rate

Preinfusion heart rate over the 3 days averaged 59 ± 3 beats/min in women and 63 ± 2 beats/min in men, with the corresponding values for the Epi infusion being 68 ± 3 and 67 ± 2 beats/min, respectively; for NE, 56 ± 3 and 60 ± 2 beats/min, respectively; and for Epi+NE, 65 ± 3 and 68 ± 2 beats/min, respectively. There were no significant changes in response to any infusion in either women or men. Blood pressure also did not change significantly with any infusion: preinfusion 106/51 and 119/56 mmHg in women and men, respectively, with the corresponding values for the infusions being 104/45 and 114/49 mmHg for Epi, 110/56 and 121/56 mmHg for NE, and 107/50 and 120/52 mmHg for Epi + NE.

Glycerol Kinetics

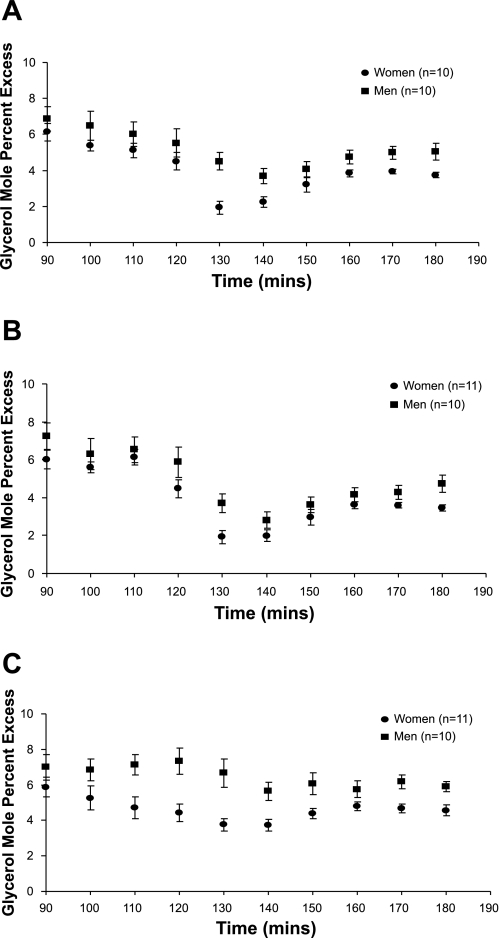

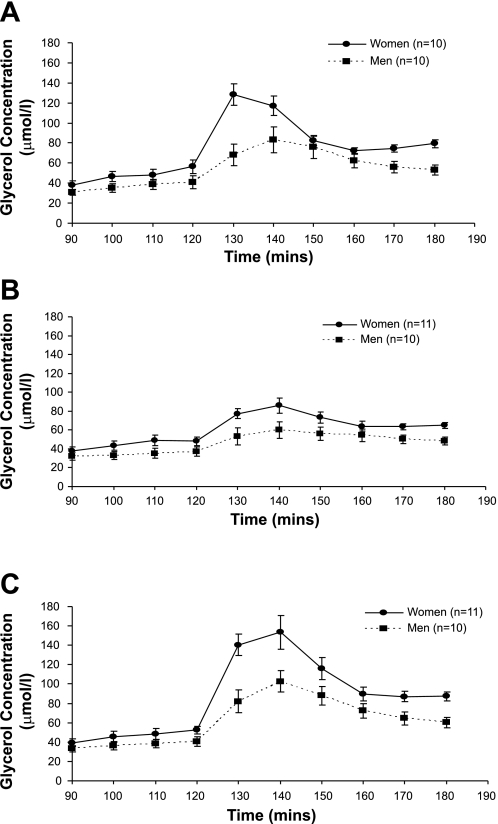

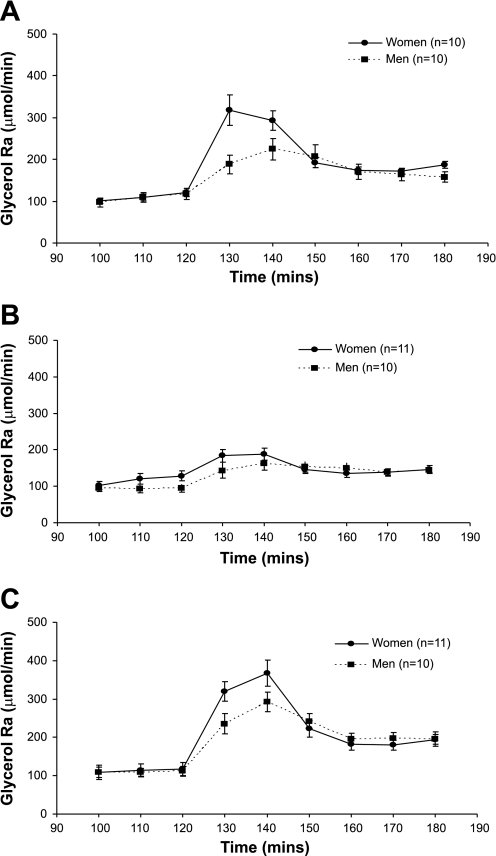

Figure 1 shows the glycerol enrichment, expressed as moles percent excess (MPE%), at rest and during the 60 min of each hormone infusion. Despite the increase in isotope infusion rate, glycerol MPE% fell during the first 30 min of each catecholamine infusion and then remained more stable during the final 30 min. Figures 2 and 3 show the glycerol concentration and glycerol Ra (absolute rates), respectively, throughout each experimental day. There was a significant effect of time (P < 0.0001) due to an initial increase in glycerol concentration and glycerol Ra after the start of the hormone infusions, followed by a decrease. For glycerol concentration and absolute Ra, there was a significant time × sex (P < 0.0001) and time × infusion (P < 0.0001) interaction. Results were similar for glycerol Rd (time × sex interaction, P < 0.001, and time × infusion interaction, P < 0.0001). Post hoc analysis revealed a significant difference between glycerol concentrations during the combined Epi + NE and NE infusions (P < 0.0001), whereas, for glycerol Ra and Rd, there was a significantly greater increase for Epi + NE vs. NE (P < 0.0001) and also Epi vs. NE (Ra, P = 0.02 and Rd, P = 0.03).

Fig. 1.

Glycerol tracer enrichment, expressed as mole percent excess (MPE%) is shown at rest (90–120 min) and during epinephrine (Epi; A), norepinephrine (NE; B), and Epi + NE (C) infusion (130–180 min). Values are means ± SE.

Fig. 2.

Glycerol concentration is shown at rest (90–120 min) and during Epi (A), NE (B), and Epi + NE (C) infusion (130–180 min). Significant time × infusion interaction (P < 0.0001) and time × sex interaction (P < 0.0001). Post hoc comparisons revealed a significant difference between Epi + NE vs. NE (P < 0.0001). Values are means ± SE.

Fig. 3.

Glycerol rate of appearance (Ra) is shown at rest (100–120 min) and during Epi (A), NE (B), and Epi + NE (C) infusion (130–180 min). Significant time × infusion interaction (P < 0.0001) and time × sex interaction (P < 0.0001). Post hoc comparisons revealed a significant difference between Epi vs. NE (P = 0.02) and Epi + NE vs. NE (P < 0.0001). Values are means ± SE.

Data were also compared between groups and treatments for glycerol Ra and Rd at rest, over the first 30 min of hormone infusion, and over the final 30 min of hormone infusion (Table 3). Data are expressed in absolute terms and relative to body weight for comparison with other data in the literature. Women had a significantly greater glycerol Ra and Rd compared with men at rest when data were expressed relative to body weight (P = 0.003), but not for absolute rates of glycerol Ra or Rd. Between 130 and 150 min of hormone infusion, there was a significant effect of sex with respect to absolute glycerol Ra and Rd (P < 0.01), with greater differences observed when data were expressed per body weight (P < 0.0001). Comparing kinetic data from 160 to 180 min, however, resulted in no sex difference for absolute glycerol Ra and Rd, whereas data were still significantly different between men and women when expressed per body weight (P < 0.0001). The NE + Epi infusion, or Epi infusion alone, consistently resulted in a greater glycerol Ra and Rd vs. the NE-only infusion, the magnitude of difference tending to be greater for the 130- to 150-min time period compared with the 160- to 180-min time period.

Table 3.

Average glycerol rate of appearance and disappearance at rest and during the first and second 30 min of each hormone infusion

| Average Rest |

Average 130- to 150-min Infusion | Average 160- to 180-min Infusion | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Epi | NE | Epi + NE | Epi | NE | Epi + NE | Epi | NE | Epi + NE | |

| Ra, μmol/min | |||||||||

| Women | 110±8 | 117±13 | 110±16 | 268±18d,f | 173±13d | 303±24d,e | 177±6k | 140±9 | 185±13e |

| Men | 108±12 | 94±10 | 110±11 | 206±21f | 153±17 | 257±21e | 164±14k | 144±10 | 196±16e |

| Ra, μmol·kg body wt−1·min−1 | |||||||||

| Women | 1.87±0.15b | 1.97±0.22b | 1.82±0.25b | 4.59±0.40a,g | 3.00±0.22a | 5.18±0.43a,e | 2.99±0.08a,j | 2.33±013a | 3.10±0.20a,e |

| Men | 1.46±0.16 | 1.27±0.15 | 1.50±0.16 | 2.79±0.29g | 2.04±0.23 | 3.45±0.27e | 2.20±0.17j | 1.93±0.12 | 2.65±0.20e |

| Rd, μmol/min | |||||||||

| Women | 103±7 | 112±12 | 105±16 | 252±18d,g | 161±14d | 272±23d,e | 180±5l | 144±9 | 199±14e |

| Men | 103±10 | 91±10 | 106±10 | 186±18g | 141±16 | 229±19e | 177±17l | 149±11 | 212±17e |

| Rd, μmol·kg body wt−1·min−1 | |||||||||

| Women | 1.75±0.15c | 1.90±0.21b | 1.76±0.24c | 4.31±0.41a,h | 2.82±0.25a | 4.66±0.43a,e | 3.03±0.09a,i | 2.45±0.12a | 3.31±0.22a,e |

| Men | 1.38±0.14 | 1.23±0.14 | 1.44±0.15 | 2.52±0.25h | 1.89±0.22 | 3.09±0.25e | 2.38±0.21i | 1.93±0.15 | 2.86±0.21e |

Values are means ± SE. Ra, rate of appearance; Rd, rate of disappearance. Significant main effect of sex:

P < 0.0001,

P = 0.003,

P = 0.004,

P < 0.01. Significant difference vs. NE infusion over the same time period:

P < 0.0001,

P < 0.001,

P = 0.002,

P = 0.005,

P = 0.02,

P = 0.03,

P < 0.05,

P = 0.055.

Glucose Kinetics

Glucose enrichment at rest and during the 60 min of each hormone infusion were stable in women (1.33 ± 0.19 and 1.30 ± 0.19 MPE%, respectively) and men (1.57 ± 0.10 and 1.57 ± 0.09 MPE%, respectively). Table 4 shows glucose concentration and Ra compared between groups and treatments at rest, over the first 30 min of hormone infusion, and over the final 30 min of hormone infusion. As glucose kinetics were stable over the duration of each measurement period, glucose Ra and glucose Rd (data not shown) were essentially the same. Resting glucose concentration was significantly lower in women vs. men (P < 0.0001), and this sex difference persisted throughout the duration of each hormone infusion (P < 0.01). An overall effect of infusion was observed for glucose concentration (t = 130–150 min, P = 0.014 and t = 160–180 min, P < 0.001). For the first 30 min, this was due to a higher glucose concentration during the Epi + NE vs. NE infusion (P = 0.013), whereas both the Epi + NE and Epi infusions resulted in higher glucose levels vs. the NE infusion during the final 30 min (P < 0.001 and P = 0.017, respectively). For data averaged over each time period, comparisons within each time frame showed no difference for glucose Ra by sex or infusion. This was also true for glucose Rd. Results were the same for glucose kinetics expressed relative to FFM (data not shown). It appeared that the significant changes in glucose concentration were not necessarily reflected in significant differences in glucose kinetics with the different hormone infusions. This was likely due to the relatively small changes in concentration along with almost all of the change occurring by the time the first blood sample was taken after the start of the hormone infusions (within 10 min). Glucose concentrations at rest vs. 130 min of Epi infusion were 80 ± 1 vs. 86 ± 2 mg/dl in women and 85 ± 1 vs. 87 ± 2 mg/dl in men; for the NE infusion, 80 ± 1 vs. 83 ± 1 mg/dl and 85 ± 2 vs. 88 ± 2 mg/dl, respectively; and for the Epi + NE infusion, 81 ± 1 vs. 87 ± 2 mg/dl and 85 ± 1 vs. 89 ± 2 mg/dl, respectively. Concentrations were then stable through the end of the study. Although there was a significant overall effect of time (P < 0.0001) for glucose Ra and Rd, changes were small, and the most dynamic changes likely occurred in the first 10 min of the infusions (before blood sampling commenced) with a rapid reestablishment of a relatively unchanged glucose turnover.

Table 4.

Average glucose concentrations and rate of appearance at rest and during the first and second 30 min of each hormone infusion

| Average Rest |

Average 130- to 150-min Infusion d | Average 160- to 180-min Infusion c | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Epi | NE | Epi + NE | Epi | NE | Epi + NE | Epi | NE | Epi + NE | |

| Concentration, mg/dl | |||||||||

| Women | 81±1a | 80±1a | 81±1a | 87±2b | 82±1b | 87±1b,e | 88±2b,f | 82±1b | 88±2b,g |

| Men | 85±1 | 85±2 | 85±1 | 88±1 | 87±1 | 91±2e | 89±2f | 86±2 | 93±2g |

| Ra, μmol·kg body wt−1·min−1 | |||||||||

| Women | 11.2±0.9 | 10.5±0.7 | 11.2±1.0 | 11.6±0.9 | 10.4±0.8 | 11.6±1.1 | 11.3±0.8 | 10.0±0.7 | 10.7±0.6 |

| Men | 11.4±0.6 | 11.0±0.7 | 11.2±0.6 | 11.5±0.7 | 11.0±0.7 | 11.9±0.8 | 11.3±0.6 | 10.6±0.6 | 11.7±0.7 |

Values are means ± SE. Significant main effect of sex:

P < 0.0001,

P < 0.01. Significant main effect of infusion:

P < 0.001,

P = 0.014. Post hoc analysis: significant difference between Epi + NE vs. NE,

P = 0.013; Epi vs. NE,

P = 0.017; and Epi + NE vs. NE,

P < 0.001.

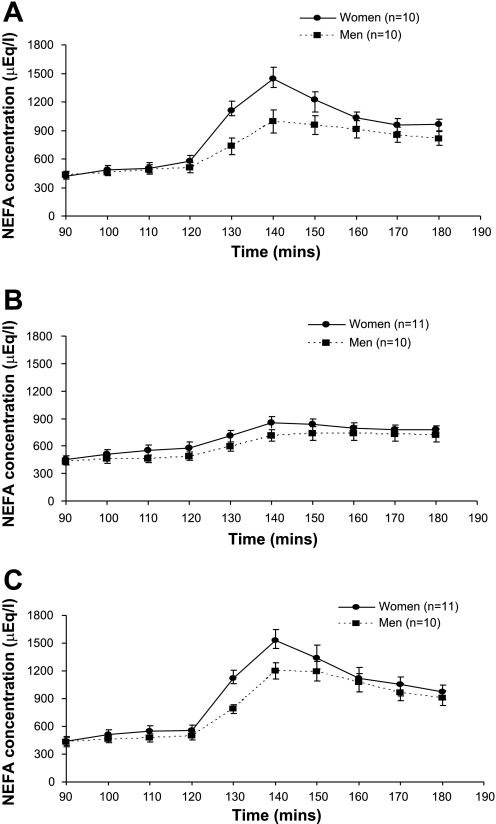

NEFA Concentrations

NEFA concentrations mirrored those of glycerol for all treatments and between women and men (Fig. 4). There was a significant time × sex interaction (P < 0.002) due to concentrations increasing more in women than men during the catecholamine infusions. In both women and men, Epi and Epi + NE resulted in significantly greater NEFA levels over time compared with the NE infusion (P = 0.045 and P = 0.003, respectively).

Fig. 4.

Nonesterified fatty acid concentration is shown at rest (90–120 min) and during Epi (A), NE (B), and Epi + NE (C) infusion (130–180 min). Significant time × infusion interaction (P < 0.001) and time × sex interaction (P < 0.002). Post hoc comparisons revealed a significant difference between Epi vs. NE (P = 0.045) and Epi + NE vs. NE (P = 0.003). Values are means ± SE. FFA, free fatty acid.

Energy Expenditure and Whole Body Substrate Oxidation

The average metabolic rate before and during the hormone infusions is shown in Table 5. In both women and men, metabolic rate increased from rest to each hormone infusion, significantly so for Epi and Epi + NE (P < 0.0001). Absolute protein oxidation, estimated from urinary nitrogen excretion, was significantly higher in men vs. women (P < 0001) on all days (Epi: 0.056 ± 0.003 vs. 0.042 ± 0.003 g/min; NE: 0.062 ± 0.005 vs. 0.052 ± 0.006 g/min; and Epi + NE: 0.068 ± 0.008 vs. 0.043 ± 0.003 g/min). Respiratory gas exchange was, therefore, adjusted for the sex-specific protein oxidation rates, giving the nonprotein RER (NPRER; Table 5). The NPRER significantly decreased during hormone infusions (P < 0.0001), and this decrease was significantly greater in women compared with men (P < 0.001). Using the NPRER to calculate whole body fat and CHO oxidation rates (g/min), revealed that fat oxidation increased significantly (P < 0.0001), whereas CHO oxidation decreased significantly (P < 0.0001) with hormone infusions. Nutrient oxidation relative to total oxidation (%total) was calculated to allow for the differences in whole body metabolic rate between men and women. Preinfusion, the percent contribution of each nutrient to total oxidation was not different between women and men: fat 59–62%, CHO 17–21%, and protein 19–24%. There was a significant time × sex interaction for relative fat (P < 0.0001) and CHO (P < 0.0001) oxidation, as women had a significantly greater contribution from fat to total oxidation compared with men during hormone infusions (Epi: 85 ± 3 vs. 74 ± 3%; NE: 73 ± 3 vs. 68 ± 4%; Epi + NE: 84 ± 3 vs. 71 ± 6%) and a significantly lower CHO contribution (Epi: −3 ± 3 and 8 ± 3%; NE: 4 ± 3 and 10 ± 3%; Epi + NE: −2 ± 3 and 7 ± 5%, respectively). Relative protein oxidation decreased with time (P < 0.0001); this was not different between the sexes.

Table 5.

Metabolic rate and nonprotein respiratory exchange ratio before and during the final 30 min of hormone infusion

| Epi |

NE | Epi + NE | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MR, kcal/min | NPRER | MR, kcal/min | NPRER | MR, kcal/min | NPRER | |

| Before infusion | ||||||

| Women | 0.94±0.02 | 0.78±0.01 | 0.92±0.02 | 0.77±0.02 | 0.95±0.02 | 0.77±0.01 |

| Men | 1.21±0.03* | 0.77±0.01 | 1.22±0.03* | 0.77±0.01 | 1.24±0.03* | 0.77±0.02 |

| During infusion | ||||||

| Women | 1.03±0.03 | 0.70±0.01† | 0.97±0.03 | 0.72±0.01† | 1.06±0.03 | 0.70±0.01† |

| Men | 1.33±0.03* | 0.74±0.01 | 1.24±0.03* | 0.75±0.01 | 1.34±0.03* | 0.73±0.02 |

Values are means ± SE. MR, metabolic rate; NPRER, nonprotein respiratory exchange ratio. Significant main effect of sex:

P < 0.0001. Significant time by sex interaction:

P = 0.001.

DISCUSSION

This study evaluated the effect of matched, moderate elevations in circulating catecholamines, similar to those observed during moderate exercise, on systemic glycerol and glucose kinetics in women compared with men. In response to Epi alone or Epi + NE, women had a greater increase in systemic glycerol release compared with men, implying a greater lipolytic response to the same circulating level of catecholamines. Systemic NEFA levels were also increased significantly more in women than men with each catecholamine infusion, and this was accompanied by a greater increase in whole body lipid oxidation. With this moderate dose of Epi and/or NE, both women and men had a similar, but small increase in glucose production and glucose disposal. These data suggest that, in women, their greater lipolytic sensitivity to catecholamines contributes to an increased capacity for lipid mobilization and utilization, which likely enables them to accommodate changes in fuel requirements associated with metabolic perturbations with minimal changes in glucose turnover. This could be viewed as facilitating glucose conservation in women relative to men.

The only other study that has evaluated lipid kinetics in men and women during Epi infusion used isotopically labeled palmitate to measure NEFA release (29). Systemic NEFA concentrations and Ra were increased similarly in men and women over the final 60 min of a 2-h infusion (Epi ∼8-fold above resting levels), showing no sex difference in systemic NEFA release. With this study design, however, NEFA Ra may not appropriately reflect lipolysis, especially when trying to relate this to what occurs during exercise. For example, with catecholamine infusion under resting conditions, NEFA oxidation, as well as blood flow, will not change to the same extent as during exercise. Consequently, there will likely be greater local accumulation of NEFA within the tissue of release, as well as potentially greater reesterification of NEFA (5, 20, 21), meaning that NEFA Ra at rest may underestimate the lipolytic potential. Furthermore, it has been shown that, at rest, with >60 min of hormone infusion, significant tachyphylaxia of the β-adrenergic receptors occurs (1). Indeed, in our present study, it appeared that tachyphylaxia occurred after 20–30 min of catecholamine infusion as glycerol turnover markedly decreased in the final 30 min of each study. As the sex difference observed in glycerol kinetics in the present study occurred in the first 30 min of infusion, and was no longer present in the final 30 min, the present data imply that tachyphylaxia may have been greater in women than men. This could also have been a factor contributing to the lack of a sex difference in NEFA kinetics in response to Epi reported by Jensen et al. (29).

The data on circulating NEFA changes corroborate the observation of increased lipolysis in women vs. men. Systemic NEFA levels were increased more in women than men with catecholamine infusions, suggesting increased mobilization of lipid fuel from tissue triglyceride stores, although this could only be definitively concluded with measures of NEFA Ra. Nevertheless, the elevation in systemic NEFA levels was accompanied by a greater increase in lipid oxidation in women vs. men during hormone infusions. It should be noted, however, that, in a few of the subjects, NPRER was < 0.70, leading to a slightly negative CHO oxidation using the stochiometric calculations of gas exchange. An NPRER under 0.70 implies nonoxidative contribution to gas exchange, which, under these experimental conditions, is difficult to explain. Rather, the result could be related to slight errors in both the indirect calorimetry measures of gas exchange and the estimation of protein oxidation from urinary nitrogen excretion, resulting in an artifact that lowered NPRER < 0.70. In such instances, it is probably more appropriate to assume CHO oxidation equaled zero rather than a negative value. In doing so, this did not change the observation of a sex difference in fat and CHO oxidation. Hence, these data support the conclusion that the increased lipolysis observed in women in response to catecholamine infusions is associated with an increase in circulating levels of lipid fuel (NEFAs) and also increased lipid utilization.

The impetus for the current investigation came from observations of sex-based differences in substrate metabolism in studies during metabolic stress, including exercise and hypoglycemia (4, 12, 13, 15, 23, 25, 26, 37, 56–58). The endocrine regulation of lipid (and glucose) metabolism during metabolic stress is orchestrated by a number of complimentary hormonal changes, implying that more than one factor may be involved in the sex-based differences in lipid mobilization and utilization. Catecholamines are considered important regulators of lipolysis, thus the observations of a significantly lower increase in these hormones, in particular epinephrine, in women relative to men during metabolic stress raises the issue of their role in sex-based differences in the regulation of lipolysis under such conditions. Nevertheless, other factors that could contribute to sex-based differences in lipid metabolism include insulin, growth hormone (GH), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and cortisol. With respect to insulin, sex differences in the fall in insulin with exercise could facilitate sex differences in lipolysis, but, in general, data show no sex difference in this decline (23, 26, 46, 49). Despite the fact that women have higher GH levels than men at rest, importantly, the magnitude of the increase in GH from rest to exercise has been reported to be similar (62) or greater (23) in men vs. women. Likewise, although there are sex differences in resting cortisol levels, cortisol increases with exercise are similar between men and women (15, 23, 26). IL-6 has emerged as a potential lipolytic factor (59), and this cytokine is released from muscle during exercise (22, 39). It appears, however, that at the circulating levels of IL-6 commonly achieved with moderate exercise, concentrations are insufficient to elevate lipolysis, at least in men (24). Whether there are sex differences in the lipolytic response to IL-6 and/or IL-6 changes with exercise are currently unknown. More recently, atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP) has been reported to mediate exercise-induced lipolysis (37, 38), more so than catecholamines, but men and women do not differ in their ANP response to exercise (37). A lack of a sex-based difference in the increase (or decrease) in these lipolytic factors during exercise or hypoglycemia does not exclude the possibility that they may interact with each other, to enhance lipolysis and lipid oxidation more in women than in men. This study does show, however, that sex-based differences in the lipolytic response to catecholamines are likely one important factor determining the sex-based differences in lipid metabolism during metabolic stress.

The question arises as to what might be the tissues contributing to the sex difference in catecholamine-stimulated lipolysis. Systemic measures of glycerol Ra predominantly reflect lipolysis from peripheral locations, that is, subcutaneous adipose tissue and skeletal muscle, as, in both sexes, at least 90% of the glycerol released from visceral adipose tissue lipolysis is cleared on first pass by the liver (27). Data suggest that lipoprotein lipase (LPL) mediated generation of glycerol from very-low-density lipoprotein triglyceride (VLDL-TG) hydrolysis is also unlikely to contribute measurably to systemic glycerol Ra after an overnight fast (17, 28). Although catecholamines can increase LPL activity in muscle (16, 40) and may decrease LPL activity in adipose tissue (42), our previous data, on exercise effects on muscle and adipose tissue LPL activity in men and women, suggest that sex differences in LPL mediated VLDL-TG lipolysis are unlikely to contribute to the greater systemic glycerol Ra observed in women in the present study. Rather, data suggest that, in women, peripheral tissue lipolysis is the source of the increased glycerol release.

As was hypothesized, no sex difference in glucose kinetics occurred with the catecholamine infusions used in the present study. Both women and men had only a very small change in glucose production and utilization with this moderate elevation in circulating catecholamines levels. This is not necessarily unexpected for NE alone, as this is not a potent stimulator of glucose production acutely (9), whereas it might have been expected that the Epi would have increased glucose Ra to a larger extent (7, 44). Our observation of a minimal change in glucose kinetics with this moderate elevation in circulating catecholamine levels suggests that, during moderate exercise, other factors determine the increase in glucose production that occurs. In a previous study (26), we observed that men had a significantly greater increase in glucose Ra and Rd compared with women during 90 min of exercise at 60% of maximal oxygen uptake (85% of lactate threshold). Notably, measurements were made after an overnight fast, when liver glycogen levels would have been low, similar conditions to those of the present study. Although the men had a significantly greater exercise increase in Epi compared with women, they also had a greater increase in circulating glucagon levels. We hypothesized that the increment in glucagon, in the face of similar insulin levels, was playing the dominant role in the exercise sex difference in glucose Ra, confirming previous observations (60). Results from the present study support such a conclusion as, during the catecholamine infusions, glucagon and insulin levels did not change, nor were they different between men and women, and we observed no sex difference in glucose kinetics, with only a very small increase in glucose production.

Although women and men had similar rates of glucose disposal, total CHO, that is, glucose oxidation, was lower in women than men, suggesting a greater nonoxidative glucose disposal in women. We made a crude estimate of nonoxidative glucose disposal based on the data from the nine women and nine men for whom glucose Rd data were available, along with glucose oxidation. Two comparisons were made: one using the negative glucose oxidation estimated from the indirect calorimetry and urinary nitrogen calculations, and the other assuming the negative glucose oxidation was equal to 0. Repeated-measures (rest vs. infusion) ANOVA revealed a significant (P = 0.012) and marginally significant (P = 0.07), time × sex interaction (data expressed relative to FFM), respectively, for the two methods of calculating nonoxidative disposal. The data do, therefore, tend to suggest a higher nonoxidative glucose disposal in women vs. men. Whether this was due to greater glycogen synthesis and/or a higher conversion of glucose to lactate in women relative to men could not be determined in the present study.

We chose to infuse NE, as well as Epi, to determine the effect of the catecholamine combination on glycerol kinetics, as both of these hormones change significantly with exercise and more so in men than women. It was hypothesized that the combined infusion would act synergistically, i.e., resulting in a greater glycerol Ra than the combined, individual effects of Epi or NE alone, and that this synergistic effect would be observed in women but not necessarily men. Our observations, however, did not support this hypothesis. Nevertheless, it is acknowledged that the systemic delivery of norepinephrine does not mimic the dominant way in which norepinephrine will affect tissue lipolysis in response to an increase in sympathetic nervous system activity (2), as occurs during exercise. Norepinephrine release at the nerve terminals within a tissue acts locally to induce physiological changes, including stimulation of lipolysis. The “spillover” of norepinephrine into the systemic circulation underestimates the quantity of norepinephrine released within a tissue. Nevertheless, the systemic delivery of norepinephrine can also stimulate metabolic effects (31, 53). In the present study, the increase in glycerol Ra with the level of norepinephrine infused was small in both men and women. Although this level was similar to circulating norepinephrine levels that may be observed with moderate exercise, it almost certainly underrepresents what would have been released at the nerve terminals, which would likely result in greater lipolysis. Had we used a high dose of norepinephrine alone, and in combination with the Epi, we may have seen a higher rate of lipolysis under both conditions (31). Whether a greater norepinephrine level is required to elicit a synergistic interaction with epinephrine is a possibility; therefore, such an interaction cannot be ruled out in women and/or men.

It is possible that there are sex differences in the norepinephrine release and/or “spillover” following sympathetic nervous system activation, and this is responsible for the sex differences in circulating norepinephrine levels with metabolic pertubations. Data from measures of muscle sympathetic nerve activity in women and men in response to hypoglycemia, however, report that women have a lower sympathetic response to the same metabolic perturbation (12–14). Although this information is indirect, it does suggest that tissue norepinephrine release is indeed lower in women than men, but does not address whether or not norepinephrine reuptake is different between the sexes.

Although we attempted to minimize the change in glycerol enrichment during each hormone infusion study by increasing the glycerol infusion rate, enrichments still fell during the initial infusion period. The nonsteady-state nature of the changes in glycerol kinetics with this study design are unavoidable due to the inherent dynamic nature of the response to catecholamine stimulated lipolysis. Although not ideal for the application of tracer methodology, the nonsteady-state calculations allow for this, for the most part (55), and has been shown to be robust for the measurement of glycerol turnover under conditions more dynamic than those observed in the present study (19). Unfortunately, the time that a steady state in lipolyisis occurs in response to catecholamine stimulation is after tachyphylaxia has been established, at least under resting conditions (1). It is interesting that, during exercise, lipolysis continues and actually increases over time, with no evidence of tachyphylaxia, despite continued elevations in epinephrine and norepinephrine. The reasons for this difference between tachyphylaxia in the resting and exercise conditions could be related to a number of factors. First, the mediators of the tachyphalaxic response of β-adrenergic receptors are changed. It is not completely understood what may induce tacyphalaxia, but local elevation in NEFA and/or adenosine, as well as systemic increases in ketones, have all been proposed as factors leading to the downregulation of the receptors. (32, 33). Downregulation of the β-adrenergic receptors acutely by such factors may be mitigated, if these metabolites can be removed from the cellular environment; for example, during exercise, changes in blood flow, metabolic demand, and substrate utilization may facilitate such a reduction in receptor exposure to antilipolytic factors. Alternatively, other hormones and factors previously discussed may be permitting continued lipolysis during exercise.

For studies that compare women and men directly, there is always an issue of how best to match the subjects and then how to express data. We matched women for age and physical activity level, as both factors can impact the metabolic response to sympathetic stimulation. Our subjects were not highly trained, but were habitually active (25–30 min of mild to moderately intense aerobic activity/day), and we also pair matched men and women based on their self-reported activity level. Interestingly, the women and men matched in this way had similar absolute fat masses, with all of the sex difference in body weight being due to differences in FFM. We have observed this previously in normal weight but more active women and men matched for habitual activity and fitness level (26). As adipose tissue is the major site of lipolysis, it might be considered that expressing data relative to fat mass, or statistically covarying for fat mass, may be the best approach for evaluating sex differences in glycerol Ra. This was not necessary, however, as women and men in this study had identical fat masses, so we expressed data in absolute terms (i.e., μmol/min). It was not felt to be appropriate to covary for fat mass, as, with this small number of subjects, we were unable to observe a significant correlation between fat mass and average glycerol Ra for each infusion (either the 60-min average or the average for each 30-min period). Whether the data were expressed in absolute terms or relative to body weight, the more traditional way of expressing glycerol kinetic data, we observed a higher rate of glycerol release in response to Epi or Epi + NE in women vs. men.

In conclusion, this study demonstrated a significantly greater increase in systemic glycerol Ra in response to the same moderate elevation in circulating epinephrine and/or norepinephrine in women vs. men. This suggests that women have a greater increase in peripheral lipolysis in response to catecholamines compared with men, and that women are more sensitive to the lipolytic action of catecholamines. While sex differences in glycerol kinetics were observed, no sex differences occurred in glucose production or utilization. Thus the lower catecholamine levels observed in women vs. men during exercise and other metabolic perturbations may allow women to achieve a similar or greater level of lipid mobilization and utilization compared with men, while facilitating relative glucose conservation.

GRANTS

This investigation was supported by National Institutes of Health grants HL 59331, HL 04226, DK 48520, DK 071155, and by Public Health Services Research Grant M01 RR00051 from the Division of Research Resources.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all of the subjects who volunteered for the study for their time and cooperation. We also thank the General Clinical Research Center nursing, dietary, and laboratory staff for valuable assistance as well.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arner P, Kriegholm E, Engfeldt P. In vivo interactions between beta-1 and beta-2 adrenoceptors regulate catecholamine tachyphylaxia in human adipose tissue. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 259: 317–322, 1991. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bartness TJ, Song CK. Thematic review series: adipocyte biology. Sympathetic and sensory innervation of white adipose tissue. J Lipid Res 48: 1655–1672, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berk MA, Clutter WE, Skor D, Shah SD, Gingerich RP, Parvin CA, Cryer PE. Enhanced glycemic responsiveness to epinephrine in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus is the result of the inability to secrete insulin. Augmented insulin secretion normally limits the glycemic, but not the lipolytic or ketogenic, response to epinephrine in humans. J Clin Invest 75: 1842–1851, 1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carter SL, Rennie C, Tarnopolsky MA. Substrate utilization during endurance exercise in men and women after endurance training. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 280: E898–E907, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Casazza GA, Jacobs KA, Suh SH, Miller BF, Horning MA, Brooks GA. Menstrual cycle phase and oral contraceptive effects on triglyceride mobilization during exercise. J Appl Physiol 97: 302–309, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Causon RM, Carruthers M, Rodnight R. Assay of plasma catecholamines by liquid chromatography with electrochemical detection. Anal Biochem 116: 223–226, 1981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chu CA, Sindelar DK, Igawa K, Sherck S, Neal DW, Emshwiller M, Cherrington AD. The direct effects of catecholamines on hepatic glucose production occur via alpha(1)- and beta(2)-receptors in the dog. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 279: E463–E473, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chu CA, Sindelar DK, Neal DW, Allen EJ, Donahue EP, Cherrington AD. Comparison of the direct and indirect effects of epinephrine on hepatic glucose production. J Clin Invest 99: 1044–1056, 1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chu CA, Sindelar DK, Neal DW, Allen EJ, Donahue EP, Cherrington AD. Effect of a selective rise in sinusoidal norepinephrine on HGP is due to an increase in glycogenolysis. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 274: E162–E171, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chu CA, Sindelar DK, Neal DW, Cherrington AD. Direct effects of catecholamines on hepatic glucose production in conscious dog are due to glycogenolysis. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 271: E127–E137, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cryer PE Adrenaline: a physiological metabolic regulatory hormone in humans? Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 17, Suppl 3: S43–S46, 1993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davis SN, Cherrington AD, Goldstein RE, Jacobs J, Price L. Effects of insulin on the counterregulatory response to equivalent hypoglycemia in normal females. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 265: E680–E689, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davis SN, Fowler S, Costa F. Hypoglycemic counterregulatory responses differ between men and women with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes 49: 65–72, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davis SN, Shavers C, Costa F. Differential gender responses to hypoglycemia are due to alterations in CNS drive and not glycemic thresholds. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 279: E1054–E1063, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davis SN, Galassetti P, Wasserman DH, Tate D. Effects of gender on neuroendocrine and metabolic counterregulatory responses to exercise in normal man. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 85: 224–230, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eckel RH, Jensen DR, Schlaepfer IR, Yost TJ. Tissue-specific regulation of lipoprotein lipase by isoproterenol in normal-weight humans. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 271: R1280–R1286, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frayn KN, Coppack SW, Fielding BA, Humphreys SM. Coordinated regulation of hormone-sensitive lipase and lipoprotein lipase in human adipose tissue in vivo: implications for the control of fat storage and fat mobilization. Adv Enzyme Regul 35: 163–178, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Friedlander AL, Casazza GA, Horning MA, Buddinger TF, Brooks GA. Effects of exercise intensity and training on lipid metabolism in young women. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 275: E853–E863, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gastaldelli A, Coggan AR, Wolfe RR. Assessment of methods for improving tracer estimation of non-steady-state rate of appearance. J Appl Physiol 87: 1813–1822, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hagstrom-Toft E, Qvisth V, Nennesmo I, Ryden M, Bolinder H, Enoksson S, Bolinder J, Arner P. Marked heterogeneity of human skeletal muscle lipolysis at rest. Diabetes 51: 3376–3383, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hammond VA, Johnston DG. Substrate cycling between triglyceride and fatty acid in human adipocytes. Metabolism 36: 308–313, 1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Helge JW, Stallknecht B, Pedersen BK, Galbo H, Kiens B, Richter EA. The effect of graded exercise on IL-6 release and glucose uptake in human skeletal muscle. J Physiol 546: 299–305, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Henderson GC, Fattor JA, Horning MA, Faghihnia N, Johnson ML, Mau TL, Luke-Zeitoun M, Brooks GA. Lipolysis and fatty acid metabolism in men and women during the postexercise recovery period. J Physiol 584: 963–981, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hiscock N, Fischer CP, Sacchetti M, Van Hall G, Febbraio MA, Pedersen BK. Recombinant human interleukin-6 infusion during low-intensity exercise does not enhance whole body lipolysis or fat oxidation in humans. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 289: E2–E7, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Horton TJ, Pagliassotti MJ, Hobbs K, Hill JO. Fuel metabolism in men and women during and after long-duration exercise. J Appl Physiol 85: 1823–1832, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Horton TJ, Grunwald GK, Lavely J, Donahoo WT. Glucose kinetics differ between women and men, during and after exercise. J Appl Physiol 100: 1883–1894, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jensen MD Regional glycerol and free fatty acid metabolism before and after meal ingestion. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 276: E863–E869, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jensen MD, Chandramouli V, Schumann WC, Ekberg K, Previs SF, Gupta S, Landau BR. Sources of blood glycerol during fasting. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 281: E998–E1004, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jensen MD, Cryer PE, Johnson CM, Murray MJ. Effects of epinephrine on regional free fatty acid and energy metabolism in men and women. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 270: E259–E264, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jequier E, Acheson K, Schutz Y. Assessment of energy expenditure and fuel utilization in man. Annu Rev Nutr 7: 187–208, 1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kurpad AV, Khan K, Calder AG, Elia M. Muscle and whole body metabolism after norepinephrine. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 266: E877–E884, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Large V, Arner P. Regulation of lipolysis in humans. Pathophysiological modulation in obesity, diabetes, and hyperlipidaemia. Diabetes Metab 24: 409–418, 1998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lonnroth P, Jansson PA, Fredholm BB, Smith U. Microdialysis of intercellular adenosine concentration in subcutaneous tissue in humans. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 256: E250–E255, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Matthews DR, Hosker JP, Rudenski AS, Naylor BA, Treacher DF, Turner RC. Homeostasis model assessment: insulin resistance and beta-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia 28: 412–419, 1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McGuire EAH, Helderman JH, Tobin JD, Andres R, Berman M. Effects of arterial versus venous sampling on analysis of glucose kinetics in man. J Appl Physiol 41: 565–573, 1976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mittendorfer B, Horowitz JF, Klein S. Effect of gender on lipid kinetics during endurance exercise of moderate intensity in untrained subjects. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 283: E58–E65, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moro C, Pillard F, de Glisezinski I, Crampes F, Thalamas C, Harant I, Marques MA, Lafontan M, Berlan M. Sex differences in lipolysis-regulating mechanisms in overweight subjects: effect of exercise intensity. Obesity (Silver Spring) 15: 2245–2255, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moro C, Polak J, Hejnova J, Klimcakova E, Crampes F, Stich V, Lafontan M, Berlan M. Atrial natriuretic peptide stimulates lipid mobilization during repeated bouts of endurance exercise. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 290: E864–E869, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ostowski K, Rohde T, Zacho M, Asp S, Pedersen BK. Evidence that interleukin-6 is produced in human skeletal muscle during prolonged running. J Physiol 508: 949–953, 1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pedersen SB, Bak JF, Holck P, Schmitz O, Richelsen B. Epinephrine stimulates human muscle lipoprotein lipase activity in vivo. Metabolism 48: 461–464, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pietrobelli A, Formica C, Wang Z, Heymsfield SB. Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry body composition model: review of physical concepts. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 271: E941–E951, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ranganathan G, Phan D, Pokrovskaya ID, McEwen JE, Li C, Kern PA. The translational regulation of lipoprotein lipase by epinephrine involves an RNA binding complex including the catalytic subunit of protein kinase A. J Biol Chem 277: 43281–43287, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rizza RA, Cryer PE, Gerich JE. Role of glucagon, catecholamines, and growth hormone in human glucose counterregulation. Effects of somatostatin and combined alpha- and beta-adrenergic blockade on plasma glucose recovery and glucose flux rates after insulin-induced hypoglycemia. J Clin Invest 64: 62–71, 1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rizza RA, Cryer PE, Haymond MW, Gerich JE. Adrenergic mechanisms for the effects of epinephrine on glucose production and clearance in man. J Clin Invest 65: 682–689, 1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rizza RA, Haymond MW, Miles JM, Verdonk CA, Cryer PE, Gerich JE. Effect of alpha-adrenergic stimulation and its blockade on glucose turnover in man. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 238: E467–E472, 1980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Roepstorff C, Steffensen CH, Madsen M, Stallknecht B, Kanstrup IL, Richter EA, Kiens B. Gender differences in substrate utilization during submaximal exercise in endurance-trained subjects. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 282: E435–E447, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Romijn JA, Coyle EF, Sidossis LS, Gastaldelli A, Horowitz JF, Endert E, Wolfe RR. Regulation of endogenous fat and carbohydrate metabolism in relation to exercise intensity and duration. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 265: E380–E391, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Romijn JA, Coyle EF, Sidossis LS, Rosenblatt J, Wolfe RR. Substrate metabolism during different exercise intensities in endurance-trained women. J Appl Physiol 88: 1707–1714, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ruby BC, Coggan AR, Zderic TW. Gender differences in glucose kinetics and substrate oxidation during exercise near the lactate threshold. J Appl Physiol 92: 1125–1132, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sacca L, Morrone G, Cicala M, Corso G, Ungaro B. Influence of epinephrine, norepinephrine, and isoproterenol on glucose homeostasis in normal man. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 50: 680–684, 1980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sandoval DA, Ertl AC, Richardson MA, Tate DB, Davis SN. Estrogen blunts neuroendocrine and metabolic responses to hypoglycemia. Diabetes 52: 1749–1755, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sandoval DA, Gong B, Davis SN. Antecedent short-term central nervous system administration of estrogen and progesterone alters counterregulatory responses to hypoglycemia in conscious male rats. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 293: E1511–E1516, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Silverberg AB, Shah SD, Haymond MW, Cryer PE. Norepinephrine: hormone and neurotransmitter in man. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab Gastrointest Physiol 234: E252–E256, 1978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Simonson DC, DeFronzo RA. Indirect calorimetry: methodological and interpretive problems. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 258: E399–E412, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Steele R, Wall JS, De Bodo RC, Altszuler N. Measurement of size and turnover rate of body glucose pool by the isotope dilution method. Am J Physiol 187: 15–24, 1956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Steffensen CH, Roepstorff C, Madsen M, Kiens B. Myocellular triacylglycerol breakdown in females but not in males during exercise. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 282: E634–E642, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tarnopolsky LJ, MacDougall JD, Atkinson SA, Tarnopolsky MA, Sutton JR. Gender differences in substrate for endurance exercise. J Appl Physiol 308: 302–308, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Toth MJ, Gardener AW, Arciero PJ, Calles-Escandon J, Poehlman ET. Gender differences in fat oxidation and sympathetic nervous system activity at rest and during submaximal exercise in older individuals. Clin Sci (Lond) 95: 56–66, 1998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.van Hall G, Steensberg A, Sacchetti M, Fischer C, Keller C, Schjerling P, Hiscock N, Moller K, Saltin B, Febbraio MA, Pedersen BK. Interleukin-6 stimulates lipolysis and fat oxidation in humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 88: 3005–3010, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wasserman DH Four grams of glucose. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 296: E11–E21, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Webber J, McDonald IA. A comparison of the cardiovascular and metabolic effects of incremental versus continuous dose adrenaline infusions in men and women. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 17: 37–43, 1993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wideman L, Weltman JY, Shah N, Story S, Veldhuis JD, Weltman A. Effects of gender on exercise-induced growth hormone release. J Appl Physiol 87: 1154–1162, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wolfe RR Radioactive and Stable Isotope Tracers in Biomedicine. New York: Wiley-Liss, 1992.