Abstract

Persistent pulmonary hypertension of newborn (PPHN) is associated with impaired pulmonary vasodilation at birth. Previous studies demonstrated that a decrease in angiogenesis contributes to this failure of postnatal adaptation. We investigated the hypothesis that oxidative stress from NADPH oxidase (Nox) contributes to impaired angiogenesis in PPHN. PPHN was induced in fetal lambs by ductus arteriosus ligation at 85% of term gestation. Pulmonary artery endothelial cells (PAEC) from fetal lambs with PPHN (HTFL-PAEC) or control lambs (NFL-PAEC) were compared for their angiogenic activities and superoxide production. HTFL-PAEC had decreased tube formation, cell proliferation, scratch recovery, and cell invasion and increased cell apoptosis. Superoxide (O2−) production, measured by dihydroethidium epifluorescence and HPLC, were increased in HTFL-PAEC compared with NFL-PAEC. The mRNA levels for Nox2, Rac1, p47phox, and Nox4, protein levels of p67phox and Rac1, and NADPH oxidase activity were increased in HTFL-PAEC. NADPH oxidase inhibitor, apocynin (Apo), and antioxidant, N-acetyl-cysteine (NAC), improved angiogenic measures in HTFL-PAEC. Apo and NAC also reduced apoptosis in HTFL-PAEC. Our data suggest that PPHN is associated with increased O2− production from NADPH oxidase in PAEC. Increased oxidative stress from NADPH oxidase contributes to the impaired angiogenesis of PAEC in PPHN.

Keywords: persistent pulmonary hypertension, endothelial cell, NADPH oxidase

the pulmonary vascular resistance undergoes a rapid decrease at birth to facilitate gas exchange during postnatal life. Failure of this transition to occur can result in persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn (PPHN), which leads to an increased risk of death or disability (18). Angiogenesis and vasculogenesis are known to play important roles in the fetal lung development with angiogenesis playing a more important role after midgestation. Angiogenesis of pulmonary artery endothelial cells (PAEC) is impaired in PPHN (15), and impaired blood vessel formation in PPHN contributes to the elevated pulmonary vascular resistance (16). Impaired angiogenesis inhibits the formation of both blood vessels and alveoli in the developing lung from late gestation to adult life (23, 41). Impaired formation of blood vessels and alveoli also contributes to the altered lung growth observed in bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) (2, 20, 36, 39), a complication of respiratory distress syndrome in premature babies. BPD can also be associated with pulmonary hypertension and prolonged oxygen requirement during postnatal life (11, 37). Abnormalities in angiogenesis can therefore affect lung growth in a variety of lung diseases in newborn infants.

The mechanism of impaired angiogenesis in PPHN remains unclear. Decreased availability of nitric oxide (NO) has been shown to contribute to decreased angiogenesis in the ductal ligation model of PPHN (15). PPHN was previously shown to increase the expression of p67phox and production of superoxide (O2−) in whole lungs. We therefore hypothesized that increased NADPH oxidase activity plays a role in the mechanisms that impair vasodilation in PPHN (6, 10). Our group also demonstrated that uncoupled endothelial NO synthase (eNOS) activity increased oxidative stress and impaired vasodilation of pulmonary arteries in fetal lamb model of PPHN (21). Although many different sources of oxidative stress are present in blood vessels, NADPH oxidase has been identified as a potential early source of O2− after ductal ligation in lambs with PPHN (6). Accordingly, increased O2− production may reduce NO bioavailability, which is required for angiogenesis (5, 31). However, to date, no studies have directly linked O2− from NADPH oxidase as a mechanism of impaired angiogenesis in PPHN. The objectives of our study are to investigate: 1) whether PAEC from lambs with PPHN (HTFL-PAEC) show decreased angiogenesis potential; 2) whether reactive oxygen species, specifically O2−, are involved in this reduced angiogenic potential; 3) whether NADPH oxidase is a major source of O2− that impairs angiogenesis in HTFL-PAEC; and 4) whether common antioxidants can be used to improve angiogenesis in HTFL-PAEC.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials and supplies.

DMEM, Dulbecco's PBS (DPBS), HBSS, FCS, antibiotic-antimycotic (AB/AM; penicillin/streptomycin/Fungizone, 100×) liquid, lucigenin, and TrypLE were obtained from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Monoclonal antibody against Rac1 and p67phox and growth factor-reduced Matrigel were from BD Biosciences (Bedford, MA). Polyclonal anti-p47phox antibody was from Millipore (Billerica, MA). Polyclonal anti-Cu,Zn-SOD (SOD1) and anti-Mn-SOD (SOD2) antibodies were from Assay Designs (Ann Arbor, MI). Cell invasion assay kit and bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) cell proliferation assay kit were obtained from Chemicon International (Temecula, CA). In Situ Cell Death Detection POD Kit and diaminobenzidine (DAB) substrate were from Roche Applied Science (Indianapolis, IN). All other chemicals were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO).

PPHN model.

PPHN was induced by fetal ductal constriction from 127 ± 2 to 135 ± 2 days gestation as previously described (22). Control fetal lambs (NFL) received sham operation without ligation of the ductus arteriosus (DA). The use of animals in this study was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Medical College of Wisconsin. After 8 days of DA constriction, ewes were euthanized, and fetal lungs were removed en bloc.

Isolation of PAEC.

Pulmonary arteries of fetal lambs were dissected into lung parenchyma up to the 3rd generation branches. PAEC were isolated from pulmonary arteries with the use of 0.25% collagenase type A (Roche), and cells were grown in DMEM with 20% FCS. Endothelial cell identity was verified by the presence of factor VIII antigen and acetylated LDL uptake. PAEC isolated from more than 6 fetal lambs in each group were used between the 3rd and 6th passages. PAEC from NFL (NFL-PAEC) and HTFL-PAEC from same passage number were cultured at the same time in parallel for each experiment for appropriate comparison. Confluent PAEC were detached with TrypLE reagent (Invitrogen) at 37°C and mixed with DMEM containing 5% FCS and 1% AB/AM to adjust the cell count to ∼1 × 106 per milliliter for tube formation assay or mixed with serum-free DMEM for cell invasion assay. Cell number was counted by hemocytometer, and viable cells were evaluated by trypan blue stain. Only batches with >95% viable cells were used for experiments.

In vitro tube formation assay.

After overnight thaw at 4°C, 50 μl of Matrigel was gently pipetted into each well of the 96-well plate. Matrigel was allowed to solidify in the incubator for 2 h at 37°C. PAEC (2 × 104) were added on top of the Matrigel and incubated at 37°C at an oxygen concentration of either 5 or 21% supplemented with 5% CO2 for 8 or 14 h (n = 5–8). Our preliminary studies showed regression of tube formation in Matrigel after 14 h, especially in HTFL-PAEC cultures, as previously reported by Gien et al. (15). In some experiments, NADPH oxidase inhibitor, apocynin (Apo; 50 μM), or antioxidant, N-acetyl-cysteine (NAC; 500 μM), were added to evaluate the role of reactive oxygen species in tube formation. One representative picture was taken per well using an Olympus IX50 inverted microscope at ×20 magnification. Total tube length of HTFL-PAEC, with or without treatment, was normalized against total tube length of NFL-PAEC performed at the same time as one of the parameters of tube formation assay. The number of branching points per high-power field (HPF) was used as another parameter to quantify tube formation. Only tubular structures connecting 2 cell clusters were considered for measurements, whereas cell clusters with at least 3 tubular structures emanating out were considered to be a branching point.

Monolayer scratch recovery assay.

PAEC (3 × 105) were seeded into each well of a 6-well plate and grown to confluence in DMEM with 20% FCS + 1% AB/AM at an oxygen concentration of 5 or 21%. For the study, culture medium was changed to DMEM with 0.5% FCS + 1% AB/AM to serum-starve the cells for 2 h, and 2 scratches were created by a 1-ml pipette tip per well. The detached PAEC were washed away with HBSS. The medium was then changed to DMEM with 5% FCS. NAC (500 μM) or Apo (20 μM) was added to some wells to evaluate the role of reactive oxygen species in monolayer scratch recovery. After 24 h, 4 randomly selected fields per scratch line were imaged under an inverted microscope (Olympus IX50). The number of PAEC that migrated outside the margin of scratch per square millimeter and the distance of the recovery frontline (in micrometers) were measured for comparisons.

Invasion assay.

PAEC (2 × 105) in serum-free DMEM were placed into the insert of a modified Boyden chamber (Chemicon International) made of polycarbonate membrane with 8-μm pores and coated with basement membrane matrix as previously described (38). The outer chamber was filled with 500 μl of DMEM containing 1% AB/AM and 5% FCS as the chemoattractant. The chambers were then placed in an incubator at 37°C with 21% O2 + 5% CO2 for 24 h. The inserts were removed, and the noninvading cells were removed by cotton-tipped swabs. The inserts were then stained and imaged under an inverted microscope (Olympus IX50). Three randomly selected fields were imaged per each insert, and invading cells were counted in each picture. The results were normalized to NFL-PAEC values. Apo (20 μM) was added into the system in some experiments to evaluate its effect on cell invasion.

BrdU proliferation assay.

BrdU incorporation was used to estimate PAEC proliferation. PAEC (2 × 104) were seeded in each well of the 96-well plate and incubated in DMEM containing 20% FCS + 1% AB/AM at 37°C and at 5 or 21% O2. Cells were initially incubated for 8 h to allow them to attach. The medium was then changed to DMEM containing 0.5% FCS + 1% AB/AM for overnight incubation. The medium was again changed to DMEM supplemented with 5% FCS, BrdU, and 1% AB/AM for 24 h in 37°C at 5 or 21% O2. Then the plate was washed and fixed before addition of anti-BrdU antibody and conjugated secondary antibody. Finally, 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) peroxidase substrate was added, and absorbance at 450 nm (Abs450) was measured. Proliferation was assessed as being proportional to the increase in absorbance.

Apoptosis assay.

We used the method described by Sgonc et al. (35) with some modifications. PAEC (3 × 105) were seeded into each well of the Lab-Tek II four-well chamber slide and incubated in DMEM with 20% FCS and 1% AB/AM at 37°C and 21% O2 + 5% CO2 for 16 h. The cells were fixed by freshly prepared 4% formalin in DPBS at pH 7.4 for 1 h at 15–25°C followed by 3% H2O2 in methanol for 10 min at 15–25°C to block the endogenous peroxidase activity. After washing with HBSS, the cells were permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 2 min on ice and then treated with labeling mixture and incubated for 60 min at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere in the dark. Before staining with DAB, the cells were pretreated with peroxidase converter solution (Roche) for 30 min at 37°C. After hematoxylin-eosin (H&E) counter stain, the brownish apoptotic nuclei were counted under microscope and expressed as percent of all nuclei.

Measurements of O2− production by DHE epifluorescence.

PAEC (1 × 105) in DMEM supplemented with 5% FCS and 1% AB/AM were seeded into each well of a Lab-Tek II four-well chamber slide and grown at 37°C with 21% O2 + 5% CO2 to near confluence. The PAEC were then treated with HBSS and dihydroethidium (DHE; 10 μM) to detect the intracellular O2− production (32). Fluorescence was imaged under a Nikon Eclipse TE200 fluorescence microscope with excitation and emission at 510 and 590 nm, respectively.

Measurement of intracellular O2− production by HPLC.

PAEC were seeded in 60-mm plates in DMEM supplemented with 5% FCS and 1% AB/AM to confluence. DHE (10 μM) was added into the cultures for 30 min before harvest. Intracellular O2− production was then measured by HPLC according to the method described by Zhao et al. (42).

NADPH oxidase activity.

NFL-PAEC and HTFL-PAEC were grown in 100-mm plates to confluence. Cells were washed twice with ice-cold PBS and scraped into 1 ml of 20 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) containing protease inhibitor cocktail (1:100; Sigma) and 1 mM EGTA. The cell suspension was freeze-thawed twice in liquid nitrogen and then sonicated with 15% power output for 30 s on ice. Then 0.1 ml of lysate was mixed with 0.9 ml of working solution (50 mM potassium phosphate buffer at pH 7.0, 1 mM EGTA, 150 mM sucrose, 100 μM NADPH, and 5 μM lucigenin) at room temperature. The chemiluminescence generated was measured by a luminometer (AutoLumat LB 953; Berthold) every 60 s for 12 min and expressed as relative light units (RLU). Protein contents were assayed by bicinchoninic acid (BCA) method. Data are expressed as RLU per milligram protein.

Quantification of mRNA abundance.

PAEC were plated (n = 4) and cultured at 21% O2-5% CO2 and 100% humidity to confluence. RNA was extracted via TRIzol (Sigma) method, and the contaminated DNA was removed by TURBO DNA-free Kit (Ambion) in 37°C water bath for 60 min. Complementary DNA was synthesized from the extracted RNA using iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad). The PCR primers were designed using Primer3 as previously described (33) and are shown in Table 1. Real-time RT-PCR was performed by iQ5 multicolor real-time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad). The PCR cycle started at 95.0°C for 3 min followed by 40 cycles of 95.0°C for 10 s and then 58.0°C for 1 min. Melting temperatures were monitored for each pair of primers, and single peak melting temperature was observed for all of the primer pairs. Number of the threshold cycle (Ct) for each target mRNA was corrected against the corresponding Ct of β-actin mRNA to obtain the ΔCt, and then 2−ΔΔCt was calculated against the corresponding NFL-PAEC as the surrogate of mRNA abundance (26).

Table 1.

Sequence of primers used for real-time RT-PCR analyses of mRNA for NADPH oxidase (Nox) pathway, SOD, and β-actin

| Forward Primer | Reverse Primer | |

|---|---|---|

| Nox2 | 5′-GCT TGT GGC TGT GAT AAG CA-3′ | 5′-CAG ATT TGG GGC TTT ATT GC-3′ |

| p47phox | 5′-GGT GGG TCA TCA GGA AAG AA-3′ | 5′-GTG GAT GCT GTG AGC GTT G-3′ |

| Rac1 | 5′-GTC ATG GTG GAT GGA AAA CC-3′ | 5′-ACC AGG ATG ATG GGT GTG TT-3′ |

| Nox4 | 5′-CAC TCT GCT GGA TGA CTG GA-3′ | 5′-CCG AGG ACG TCC AAT AAA AA-3′ |

| SOD1 | 5′-CGA GGC AAA GGG AGA TAC AG-3′ | 5′-TGG ACA GAG GAT TAA AGT GAG G-3′ |

| SOD2 | 5′-ATT GCT GGA AGC CCA TCA AAC-3′ | 5′-AGC AGG GGG ATA AGA CCT GT-3′ |

| β-Actin | 5′-GCG GGA AAT CGT GCG TGA CAT T-3′ | 5′-GAT GGA GTT GAA GGT AGT TTC GTG-3′ |

Western blot analysis.

PAEC were cultured until confluent and then washed twice with ice-cold HBSS. The cells were lysed in modified RIPA buffer (12). The cell lysate was sonicated twice on ice with 15% power output, and cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 13,000 rpm, 4°C, for 10 min. Protein content of the lysate was determined by BCA assay. An aliquot of protein was used for immunoblotting with monoclonal antibodies for p67phox (1:500), Rac1 (1:1,000), β-actin (1:5,000) and polyclonal antibodies for p47phox (1:1,000), SOD1 (1:1,000), and SOD2 (1:2,000) to determine the levels of these proteins. The membranes were blotted with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-mouse IgG antibody (1:9,000; Bio-Rad) or HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG antibody (1:8,000; Bio-Rad) and exposed to CL-XPosure films (Pierce) after treatment with SuperSignal West Pico (Pierce). The signals were analyzed with ImageJ and normalized against the expression of the internal control, β-actin.

Ex vivo sprouting angiogenesis of resistant pulmonary arteries.

Growth factor-reduced Matrigel (50 μl) was added into each well of a 96-well plate as described for the in vitro tube formation assay. Fetal lungs and heart were removed en bloc and kept on ice before dissection. The pulmonary arteries were dissected from 5 to 7 generations to obtain resistant pulmonary arteries (RPA) under the microscope. Segments of RPA with a length of ∼0.5 mm were obtained after removal of the soft tissue and transferred onto the Matrigel. Another 50 μl of Matrigel was gently added onto the RPA segment. After returning from the 37°C incubator for 30 min, 100 μl of DMEM with 20% FCS and AB/AM was added with or without Apo (20 μM) or NAC (500 μM) and was changed daily. The tube-like structure was viewed under inverted microscope after 6 days at ×20 magnification. The distal-most tip of the tube away from the edge of the segment was measured for comparison.

Statistical analyses.

Data are shown as means ± 1 SE. Comparison of data between two groups was done by Student's t-test if the data were normally distributed, and Mann-Whitney U test was used for data that did not pass the normality test. One-way ANOVA with Student-Newman-Keuls post hoc test was used when more than two groups were analyzed. Data were analyzed with MedCalc, which was designed by Frank Schoonjans. A P value of <0.05 was considered as significant.

RESULTS

In vitro tube formation.

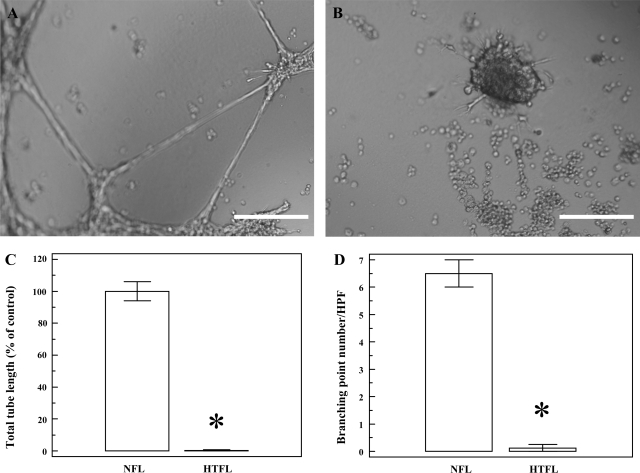

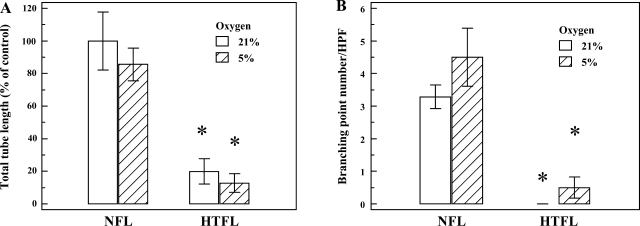

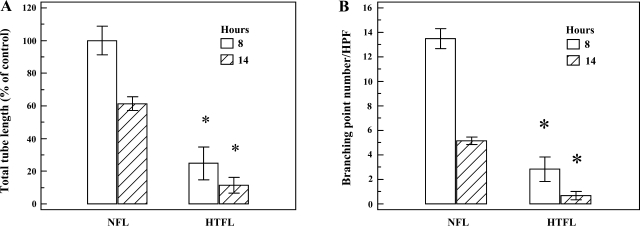

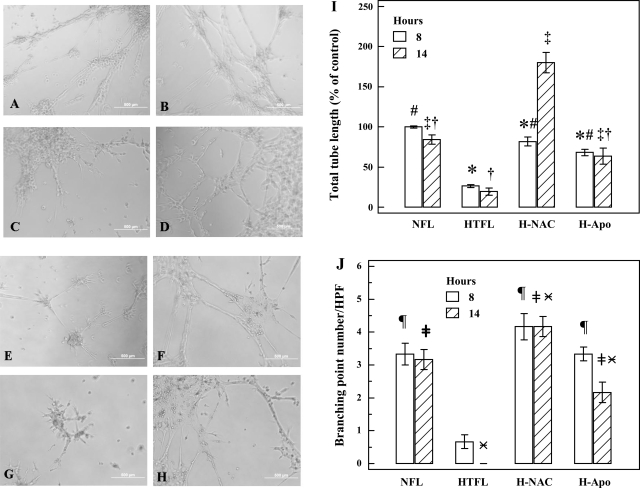

Tube formation is an integrated angiogenic activity involving proliferation, migration, invasion, and apoptosis. We used Matrigel to simulate extracellular matrix for PAEC to study mechanisms of tube formation. Total tube lengths and branching points number per HPF were significantly less in HTFL-PAEC (Fig. 1). Changing O2 concentration from 21 to 5% to simulate fetal arterial Po2 (PaO2; Fig. 2) or time allowed for tube formation (8 vs. 14 h; Fig. 3) did not alter the impaired tube formation in HTFL-PAEC. NAC and Apo increased total tube length and branching points in HTFL-PAEC cells (Fig. 4) at both 8- and 14-h time points.

Fig. 1.

Tube formation by pulmonary artery endothelial cells (PAEC) from fetal lambs with pulmonary hypertension of newborn (PPHN) (HTFL-PAEC) or control lambs (NFL-PAEC). PAEC were cultured under oxygen tension of 21% for 14 h. A: representative picture of NFL-PAEC showing both tubular structures and branching points. B: representative picture of HTFL-PAEC showing essentially no tubular structures or branching point and markedly increased clumping of cells. C: total tubular structure was significantly different between HTFL-PAEC (0.3 ± 0.3%) and NFL-PAEC (100.0 ± 6.0%). D: similar findings were also observed for total branching points per high-power field (HPF) (0.4 ± 0.1 vs. 6.5 ± 0.5). NFL, normotensive fetal lung; HTFL, hypertensive fetal lung. *P < 0.01 between NFL and HTFL (n = 8). The length of the white bar (A and B) equals 200 μm.

Fig. 2.

Effect of oxygen tension on PAEC tube formation. Tube formation assay was performed under different oxygen tensions (21 and 5%) for 14 h, and total tube length for NFL-PAEC at 21% oxygen was used as control. A: total tube length was significantly lower for HTFL-PAEC compared with NFL-PAEC at both 21 and 5% O2. There was no difference in total tube length between 5 and 21% O2 (P = 0.48 for both NFL-PAEC and HTFL-PAEC). B: the number of branching point per HPF was significantly higher for NFL-PAEC than HTFL-PAEC at both 21 and 5% O2. The open bar represents oxygen tension of 21%, and the hatched bar represents oxygen tension of 5%. *P < 0.05 between NFL and HTFL; n = 8.

Fig. 3.

Time-dependent changes in PAEC tube formation. Tube formation assay was performed in 21% oxygen tension for 8 and 14 h. A: total tubular structure was significantly decreased for HTFL-PAEC compared with NFL-PAEC at both 8 (P < 0.01) and 14 h (P < 0.01). The total tube length was longer at 8 than at 14 h for both NFL-PAEC and HTFL-PAEC. B: total branching points per HPF were lower for HTFL-PAEC than NFL-PAEC at both 8 (P < 0.01) and 14 h (P < 0.01). Similar to the total tube length, the total branching points were higher at 8 than at 14 h for both NFL-PAEC and HTFL-PAEC. The open columns represent results at 8 h, whereas the hatched columns represent results at 14 h. *P < 0.05 between NFL and HTFL; n = 6.

Fig. 4.

Effects of N-acetyl-cysteine (NAC) and apocynin (Apo) on PAEC tube formation. PAEC tube formation was performed in the absence/presence of NAC (500 μM) or Apo (20 μM). Representative pictures in A–D were taken at 8 h, whereas E–H were at 14 h. NFL-PAEC (A and E) and NFL-PAEC with NAC (B and F) had increased tube formation than HTFL-PAEC (C and G) at both 8 and 14 h. NAC significantly improved the tube formation for HTFL-PAEC at both 8 (D) and 14 h (H). Apo also improved the tube formation (I and J) at both time points (pictures not shown). NAC and Apo significantly increased the total tube length of HTFL-PAEC at both 8 and 14 h. At 14 h, the total tube length of HTFL-PAEC with NAC (H-NAC) was significantly longer than NFL-PAEC. *P < 0.05 between NFL and HTFL with/without NAC or Apo at 8 h. #P < 0.05 between HTFL and other groups at 8 h. ‡P < 0.05 between HTFL and other groups at 14 h. †P < 0.05 between H-NAC and other groups at 14 h. ¶P < 0.05 between HTFL and other group at 8 h. ≠P < 0.05 between HTFL and other groups at 14 h.  P < 0.05 between H-NAC and other groups. H-Apo, HTFL with Apo.

P < 0.05 between H-NAC and other groups. H-Apo, HTFL with Apo.

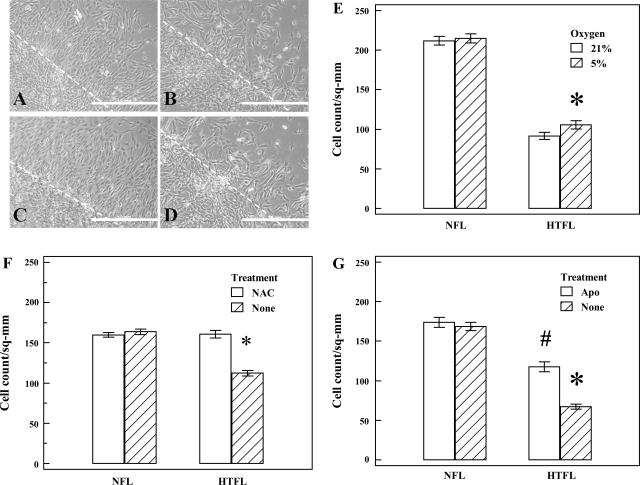

Monolayer scratch recovery assay.

When scratched, cell monolayers respond to disruption of the monolayer and intercellular contacts at the margin by an increase in migration and proliferation. The number of cells that migrated out from the scratch margin after 24 h was significantly lower for HTFL-PAEC compared with NFL-PAEC (Fig. 5). This impaired response in HTFL-PAEC is not affected by ambient O2 concentration (Fig. 5, A–E). Addition of NAC (500 μM) or Apo (20 μM) into the media after scratch improved migration and proliferation in HTFL-PAEC but not in NFL-PAEC (Fig. 5, G and H).

Fig. 5.

Effects of oxygen tension and antioxidant on PAEC migration. Monolayer scratch recovery assay was done in 6-well plate. The PAEC migration assay was performed at 21 (open bar) or 5% O2 (hatched bar). In 21% O2, the number of PAEC that migrated out of the scratch line was more for the NFL-PAEC (A) than the HTFL-PAEC (B). A similar result was seen in 5% oxygen with NFL-PAEC (C) having better recovery than HTFL-PAEC (D). NFL-PAEC migrated at a significantly higher rate than HTFL-PAEC regardless of the oxygen tension (E). NAC (500 μM) improved the migration of HTFL-PAEC to an extent similar to NFL-PAEC (F), whereas Apo (20 μM) partially improved the migration of HTFL-PAEC (G). The broken line denotes the margin of the scratch, whereas the length of the white bar equals 1 mm. *P < 0.01 between HTFL and NFL. #P < 0.01 between HTFL treated with Apo and without treatment also between HTFL treated with Apo and NFL. sq-mm, Square millimeter.

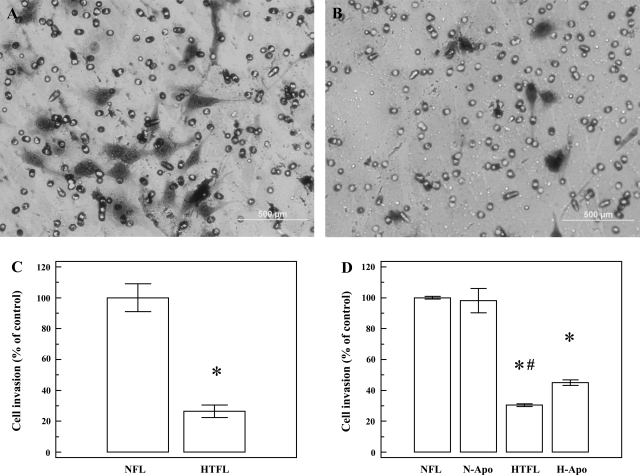

Invasion assay.

After 24 h of culture, the number of cells that migrated through the modified Boyden chamber was significantly (P < 0.0001) higher for NFL-PAEC compared with HTFL-PAEC (Fig. 6). Addition of Apo significantly increased the migration/invasion of HTFL-PAEC cells. The cell invasion for HTFL-PAEC was significantly increased (P < 0.001; n = 6) after addition of Apo, whereas no increases were observed in NFL-PAEC after addition of Apo (100.0 ± 1.0 vs. 98.2 ± 7.8%).

Fig. 6.

Differences in PAEC invasion activity. Cell invasion assay was performed by Matrigel-coated modified Boyden system with the pore size of 8 μm. Both NFL-PAEC and HTFL-PAEC were suspended in serum-free medium, and DMEM with 5% FCS was used as the attractant. After 24 h of culture in 21% O2 and 5% CO2, the cells that migrated through the pores were stained and photographed under microscope. NFL-PAEC had more cells that crossed the membrane (A) than HTFL-PAEC (30.4 ± 1.0%; B). The difference in cell count was significant (C). Addition of Apo (20 μM) significantly improved the invasion of HTFL-PAEC, whereas no change was seen in NFL-PAEC with Apo. N-Apo, NFL with Apo. *P < 0.0001 between NFL and HTFL; n = 8. #P < 0.001 between HTFL and HTFL with Apo; n = 6.

BrdU proliferation assay.

In the BrdU proliferation assay, an increase in Abs450 occurs in proportion to BrdU incorporation and, therefore, proliferation. Abs450 in NFL-PAEC (1.37 ± 0.14, n = 6) was increased to a greater extent (P < 0.01) than in HTFL-PAEC (0.79 ± 0.11, n = 6) when the assay was conducted at 21% O2. However, there was no significant differences in Abs450 (P = 0.442; n = 8) between NFL-PAEC (0.55 ± 0.07) and HTFL-PAEC (0.45 ± 0.11) when the assay was conducted at 5% O2. Our observations suggest that ambient O2 concentrations affect proliferation rates of fetal PAEC and that rates of proliferation for HTFL-PAEC are impaired at 21% O2. The decreased Abs450 at 5% O2 may due to PAEC adaptation to our regular culture environment at 21% O2.

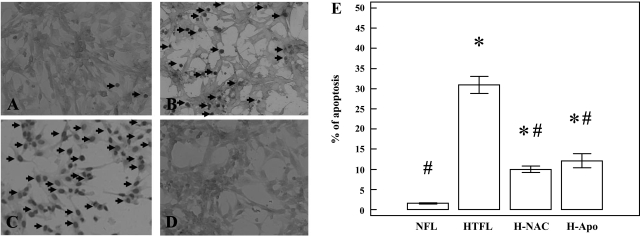

Apoptosis assay.

Apoptosis is an important component of blood vessel formation and maintenance. Too much apoptosis can impair angiogenesis. The percent of apoptotic cells was significantly greater in HTFL-PAEC cultures (P < 0.001; n = 8) compared with NFL-PAEC (Fig. 7) when the experiment was performed at 21% O2. Interestingly, apoptosis in NAC- or Apo-treated HTFL-PAEC was significantly less compared with the number of apoptotic cells in HTFL-PAEC cultures (P < 0.001; n = 8). These data suggest that reactive oxygen species play an important role in the mechanisms mediating increased apoptosis in HTFL-PAEC.

Fig. 7.

Differences in PAEC apoptosis. The in situ TdT-mediated dUTP nick end labeling-peroxidase (TUNEL-POD) stain was used to detect apoptosis of the PAEC. Apoptotic nuclei are dark brown under the microscope (arrows). A, NFL-PAEC; B, HTFL-PAEC; C, NFL-PAEC treated with DNase I was used to serve as positive control; and D, HTFL-PAEC not treated with labeling mixture was used as negative control. E: the percentage of apoptotic nuclei was significantly higher in HTFL than NFL (P < 0.001; n = 8). Apo and NAC significantly reduced the percentage of apoptosis. *P < 0.05 compared with NFL; #P < 0.05 compared with HTFL.

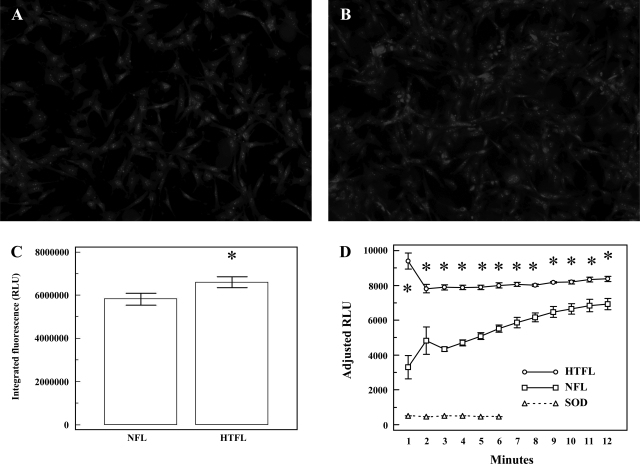

Measurements of reactive oxygen species production.

Superoxide anion production, assessed by DHE epifluorescence, increased in HTFL-PAEC (Fig. 8, A–C). HPLC measurements of 2-OH-ethidium revealed that O2− was greater in HTFL-PAEC compared with NFL-PAEC (13.1 ± 3.0 μmol/μg protein vs. 4.4 ± 1.2 μmol/μg protein; P = 0.0018; n = 6). Additionally, chemiluminescence assays indicated that NADPH oxidase activity was a major source of O2− in HTFL-PAEC compared with NFL-PAEC (Fig. 8D). As others have shown, the chemiluminescence signal was inhibited by addition of SOD. These findings suggest that HTFL-PAEC generate more O2− than NFL-PAEC by a NADPH oxidase-dependent mechanism.

Fig. 8.

The intracellular superoxide production of NFL-PAEC (A) and HTFL-PAEC (B) was estimated by dihydroethidium (DHE) epifluorescence stain. The integrated DHE fluorescence was significantly higher for HTFL-PAEC than NFL-PAEC (C; P < 0.05; n = 12). D: the NADPH oxidase activity was evaluated in 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) with 150 mM glucose, 100 μM NADPH, and 5 μM lucigenin by luminometer. Cu,Zn-SOD (SOD; empty circle) was added to demonstrate the signal was due to formation of superoxide. The cumulative relative light units (RLU) was significantly (*P < 0.05; n = 5) higher in HTFL-PAEC (empty square) than NFL-PAEC (filled square).

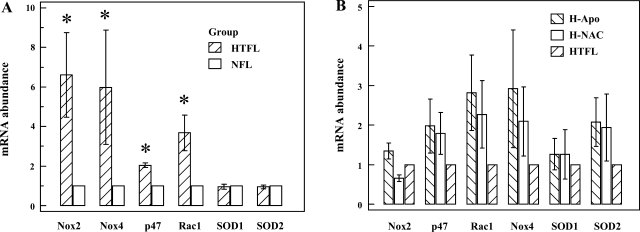

Quantification of Nox2, p47phox, Rac1, Nox4, SOD1, and SOD2 mRNA abundance.

There was no difference in Ct of β-actin between NFL-PAEC and HTFL-PAEC (P > 0.2; n = 4). Relative mRNA abundance of Nox2, p47phox, Rac1, and Nox4 were greater in HTFL-PAEC (P < 0.05; n = 4; Fig. 9A). There was, however, no difference in mRNA abundance for either SOD1 or SOD2. NAC or Apo treatments did not significantly change mRNA levels for Nox2, p47phox, Rac1, Nox4, SOD1, and SOD2 in HTFL-PAEC (Fig. 9B).

Fig. 9.

Relative mRNA levels for Nox isoforms, Nox2-associated subunits, and SODs. Real-time RT-PCR was performed using β-actin mRNA as an internal control. The 2−ΔΔCt was calculated for the mRNA abundance in fold against NFL-PAEC. HTFL-PAEC has more mRNA transcripts than NFL-PAEC for Nox2, Nox4, p47phox, and Rac1. There was no difference for either Cu,Zn-SOD (SOD1) or Mn-SOD (SOD2) between NFL-PAEC and HTFL-PAEC (A). The presence of NAC (500 μM) or Apo (20 μM) did not significantly (P > 0.2 for all) affect the mRNA transcripts for any of these protein examined (B). *P < 0.05 compared with NFL.

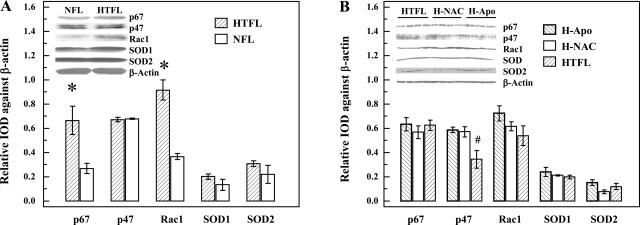

Western blot analyses.

Protein levels for p67phox were significantly greater in HTFL-PAEC compared with the levels in NFL-PAEC (P < 0.05; n = 4). Similarly, Rac1 levels were significantly greater in HTFL-PAEC than in NFL-PAEC (P < 0.01; Fig. 10A). However, no differences were detected in the levels of p47phox, SOD1, or SOD2 between NFL-PAEC and HTFL-PAEC. Treating HTFL-PAEC with NAC or Apo did not affect protein expression of Nox2, Nox4, Rac1, p67phox, SOD1, or SOD2 in HTFL-PAEC, but, interestingly, expression levels for p47phox actually increased (P < 0.05; n = 4; Fig. 10B).

Fig. 10.

Relative protein expressions of Nox2 subunits and SODs. The protein expressions of p67phox, p47phox, β-actin, Rac-1, SOD1, and SOD2 of HTFL-PAEC and NFL-PAEC were evaluated by Western blot analysis. After normalizing the signal against β-actin, there was a significantly higher expression of p67phox and Rac-1 in the HTFL-PAEC compared with NFL-PAEC. No differences for p47phox, SOD1, or SOD2 between NFL-PAEC and HTFL-PAEC were observed (A). The presence of NAC (500 μM) or Apo (20 μM) did not significantly affect the protein expressions except p47phox, which increased significantly (P = 0.014; B). *P < 0.05; n = 4. #P = 0.014 compared with HTFL with NAC or Apo; n = 4. IOD, integrated optical density.

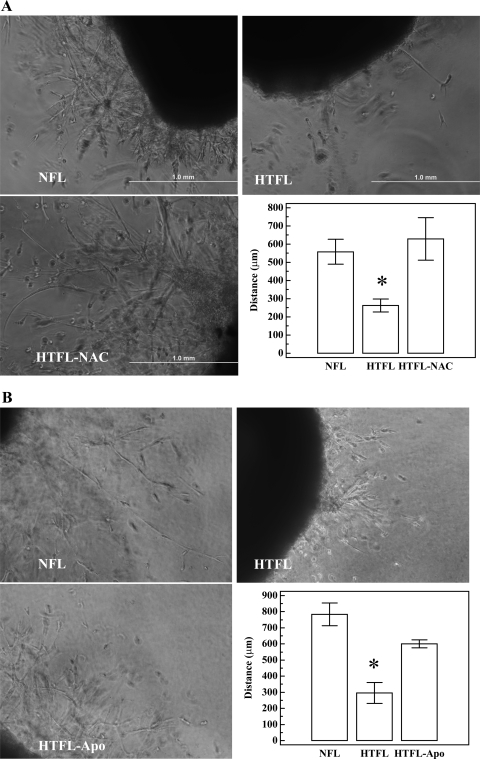

Ex vivo sprouting angiogenesis of RPA.

Sprouting from HTFL pulmonary artery segments was less (P < 0.05; n = 3) compared with sprouting from NFL pulmonary artery segments. Sprouting from HTFL pulmonary artery segments increased when treated with NAC (Fig. 11A). Apo also improved sprouting from HTFL pulmonary artery segments (Fig. 11B). These findings are consistent with the in vitro tube formation results in PAEC.

Fig. 11.

Ex vivo angiogenesis assays. The sprouting angiogenesis of pulmonary arteries performed in an ex vivo 3-dimensional Matrigel system by 6 days. A: NFL pulmonary artery segment has a better sprouting angiogenesis than HTFL pulmonary artery segment, and the presence of 500 μM NAC improves the angiogenesis. B: the presence of 20 μM Apo also improves the sprouting angiogenesis of HTFL pulmonary artery segment. *P < 0.05 compared with NFL or HTFL with antioxidant (n = 3).

DISCUSSION

Although the incidence of PPHN is estimated to be 2–5 per 1,000 live births, it accounts for nearly 10% of all neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admissions. Affected infants have increased mortality and risk of long term sequelae (18). PPHN decreases the number of blood vessels and impairs angiogenesis in the lungs, which together contribute to the increase in pulmonary vascular resistance (14). The mechanisms of impaired vascular growth are unclear, but impaired responses to VEGF or reduced NO availability have both been suggested as possible causes (17).

Fetal lambs with partial compression (1) or ligation (28) of DA in utero are commonly used to study mechanisms of PPHN. Recent studies in fetal lambs with prenatal ductal constriction demonstrated impaired angiogenesis and growth of the lungs (16). Our previous studies in this model revealed that PPHN impaired relaxation responses of pulmonary artery rings to ATP, decreased eNOS association with hsp90 (22), and increased eNOS uncoupling (21). Uncoupled eNOS activity results in the generation of O2−, which further reduces NO bioavailability (21). In addition to uncoupled eNOS activity, other oxidative enzymes may be involved in producing O2− such as Nox, xanthine oxidase/dehydrogenase, cytochrome P-450, and mitochondria (29, 35). Brennan et al. (6) demonstrated an increase in O2− production with increased expression of p67phox, a critical subunit of Nox in the pulmonary arteries from fetal lambs with in utero ductal constriction. Increased p67phox expression developed as early as 48 h after ductal constriction, suggesting that NADPH oxidase is an important early enzymatic source of O2− in PPHN (6). Our data support the observations of Brennan et al. (6) by showing that NADPH oxidase expression was increased at the transcriptional level even 8 days after ductal constriction. Our findings extend the time frame for the role of NADPH oxidase to 8 days, and, along with our observation of increased NADPH oxidase activity, we propose that NADPH oxidase plays a critical role in the impaired angiogenesis in this PPHN model.

Reactive oxygen species were previously shown to be important mediators of angiogenic signaling for endothelial cells from the systemic vasculature (8, 40). VEGF-induced endothelial migration is promoted by the activation of Rac1 (13). Rac1 is a cytoplasmic subunit for NADPH oxidase, and its activation leads to increased O2− production. Arnal et al. (3) showed that proliferating endothelial cells generate increased levels of O2− by a NADPH oxidase-dependent mechanism. Interestingly, eNOS expression and NO production are also increased by an increase in eNOS association with hsp90, which is essential for maintaining coupled eNOS activity in proliferating endothelial cells (4, 30). In support of this idea, studies by Balasubramaniam et al. (5) demonstrated that NO is an important mediator of angiogenesis in PAEC. Since O2− reacts with NO at a diffusion-limited rate (19), the availability of NO will decrease with increased O2− production. We therefore investigated whether increased O2− production impairs angiogenic activity in HTFL-PAEC. We studied O2− production and angiogenic activity of HTFL-PAEC at O2 concentrations that simulated fetal and postnatal conditions to determine if ambient O2 tension alters the effect of O2− on angiogenesis. We observed that the decreased angiogenesis in HTFL-PAEC was a consistent feature and retained even at different O2 concentrations.

Our studies demonstrated impairment of both in vitro and ex vivo angiogenesis and increased O2− production in HTFL-PAEC. The increase in apoptosis and suppression of proliferation observed in HTFL-PAEC in our studies is different from previous studies in adults with idiopathic pulmonary artery hypertension (27). Although some apoptosis is necessary to complete the process of angiogenesis, too much apoptosis impairs angiogenesis (5, 9). PAEC from adult patients show an initial apoptosis followed by increased proliferation of apoptosis-resistant PAEC in artificial perfusion systems (34). The possible explanations are differences in maturity and duration of pulmonary hypertension; PAEC in our lamb model of PPHN were exposed to increased pressures for 8 days compared with months or years in adults with idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension (IPAH). It is possible that phenotypical selection of the endothelial cells in our model remains in the early apoptosis-prone stage.

We also observed that NAC or the NADPH oxidase inhibitor, Apo, improved angiogenic activity of HTFL-PAEC and pulmonary artery segments. These findings suggest that increased production of reactive oxygen species, possibly through increased activity of NADPH oxidase, contributes to impaired angiogenesis in HTFL-PAEC. We observed greater NADPH oxidase expression in HTFL-PAEC than in NFL-PAEC. The increased expression in HTFL-PAEC occurs at both the transcriptional (increased abundance of mRNA for Nox2, Nox4, p47phox, and Rac1) and the translational level (increased p67phox and Rac1 protein expression). A potential role for NADPH oxidase in impairing angiogenesis is further supported by partial restoration of angiogenesis in HTFL-PAEC by NAC and Apo. Although the increased p47phox mRNA was not accompanied by an increase in protein expression, the increase p67phox expression in our HTFL-PAEC cultures is similar to increased p67phox in lungs of fetal lambs with PPHN (6). The increased angiogenic activity of HTFL-PAEC in response to antioxidant treatments suggests a potential therapeutic strategy in neonates with PPHN. Antioxidants may increase the bioavailability of NO, which is essential for increasing vasodilation and angiogenesis.

SOD is the most important cellular defense system against O2−. Interestingly, we observed no differences in the expression of SOD1 or SOD2 between HTFL-PAEC and NFL-PAEC at either the transcriptional or translational level. Thus the increased oxidative stress in HTFL-PAEC is more a function of increased NADPH oxidase-dependent O2− production than impaired O2− scavenging. Support for this idea comes from our findings showing that angiogenesis in HTFL-PAEC improved after treatment of cells with NAC and Apo and the fact that neither agent had any effect on HTFL-PAEC expression of SOD1 or SOD2. Accordingly, our data suggest that impaired HTFL-PAEC angiogenesis is due to the ability of these cells to generate rather than scavenge O2−.

In conclusion, our study demonstrated that in utero pulmonary hypertension is associated with increased O2− production and impaired angiogenesis in PAEC. Our data demonstrate that this phenotype change in HTFL-PAEC is the result of increased expression of NADPH oxidase, which becomes a source of O2− production.

GRANTS

The study was supported by a Grant-in-Aid from American Heart Association Northland affiliate, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant RO1-HL-57268, and a Children's Research Institute endowment fund to G. G. Konduri.

Acknowledgments

We are in debt to Drs. Robert Q. Miao and Kirkwood A. Pritchard, Jr., for their comments and review of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abman SH, Shanley PF, Accurso FJ. Failure of postnatal adaptation of the pulmonary circulation after chronic intrauterine pulmonary hypertension in fetal lambs. J Clin Invest 83: 1849–1858, 1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abman SH Bronchopulmonary dysplasia: “a vascular hypothesis”. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 164: 1755–1756, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arnal JF, Tack I, Besombes JP, Pipy B, Nègre-Salvayre A. Nitric oxide and superoxide anion production during endothelial cell proliferation. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 271: C1381–C1388, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arnal JF, Yamin J, Dockery S, Harrison DG. Regulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase mRNA, protein, and activity during cell growth. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 267: C1381–C1388, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Balasubramaniam V, Maxey AM, Fouty BW, Abman SH. Nitric oxide augments fetal pulmonary artery endothelial cell angiogenesis in vitro. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 290: L1111–L1116, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brennan LA, Steinhorn RH, Wedgwood S, Mata-Greenwood E, Roark EA, Russell JA, Black SM. Increased superoxide generation is associated with pulmonary hypertension in fetal lambs: a role for NADPH oxidase. Circ Res 92: 683–691, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chavakis E, Dimmeler S. Regulation of endothelial cell survival and apoptosis during angiogenesis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 22: 887–893, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Datla SR, Peshavariya H, Dusting GJ, Jiang F. Important role of Nox4 type NADPH oxidase in angiogenic responses in human microvascular endothelial cells in vitro. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 27: 2319–2324, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dimmeler S, Zeiher AM. Endothelial cell apoptosis in angiogenesis and vessel regression. Circ Res 87: 434–439, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Farrow KN, Lakshminrusimha S, Reda WJ, Wedgwood S, Czech L, Gugino SF, Davis JM, Russell JA, Steinhorn RH. Superoxide dismutase restores eNOS expression and function in resistance pulmonary arteries from neonatal lambs with persistent pulmonary hypertension. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 295: L979–L987, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fitzgerald D, Evans N, Van Asperen P, Henderson-Smart D. Subclinical persisting pulmonary hypertension in chronic neonatal lung disease. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 70: F118–F122, 1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garcia-Cardena G, Fan R, Shah V, Sorrentino R, Cirino G, Papapetropoulos A, Sessa WC. Dynamic activation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase by Hsp90. Nature 392: 821–824, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garrett TA, Van Buul JD, Burridge K. VEGF-induced Rac1 activation in endothelial cells is regulated by the guanine nucleotide exchange factor Vav2. Exp Cell Res 313: 3285–3297, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Geggel RL, Reid LM. The structural basis of PPHN. Clin Perinatol 11: 525–549, 1984. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gien J, Seedorf GJ, Balasubramaniam V, Markham N, Abman SH. Intrauterine pulmonary hypertension impairs angiogenesis in vitro: role of VEGF-NO signaling. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 176: 1146–1153, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grover TR, Parker TA, Balasubramaniam V, Markham NE, Abman SH. Pulmonary hypertension impairs alveloarization and reduces lung growth in the ovine fetus. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 288: L648–L654, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grover TR, Parker TA, Znge JP, Markham NE, Kinsella JP, Abman SH. Intrauterine hypertension decreases lung VEGF expression and VEGF inhibition causes pulmonary hypertension in the ovine fetus. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 284: L508–L517, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hooper WC, Mensah GA, Haworth SG, Black SM, Garcia JG, Langleben D. Vascular endothelium summary statement V: pulmonary hypertension and acute lung injury: public health implications. Vascul Pharmacol 46: 327–329, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huie RE, Padmaja S. The reaction of NO with superoxide. Free Radic Res Commun 18: 195–199, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jakkula M, Le Cras TD, Gebb S, Hirth KP, Tuder RM, Voelkel NF, Abman SH. Inhibition of angiogenesis decreases alveolarization in the developing rat lung. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 279: L600–L607, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Konduri GG, Bakhutashvili I, Eis A, Pritchard K Jr. Oxidant stress from uncoupled nitric oxide synthase impairs vasodilation in fetal lambs with persistent pulmonary hypertension. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 292: H1812–H1820, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Konduri GG, Ou J, Shi Y, Pritchard KA Jr. Decreased association of HSP90 impairs endothelial nitric oxide synthase in fetal lambs with persistent pulmonary hypertension. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 285: H204–H211, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ladha F, Bonnet S, Eaton F, Hashimoto K, Koebutt G, Thebaud B. Sildenafil improves alveolar growth and pulmonary hypertension in hyperoxia-induced lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 172: 750–756, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Langston C, Kida K, Reed M, Thurlbeck WM. Human lung growth in late gestation and in the neonate. Am Rev Respir Dis 129: 607–613, 1984. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li JM, Shah AM. Endothelial cell superoxide generation: regulation and relevance for cardiovascular pathophysiology. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 287: R1014–R1030, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(−ΔΔCT) method. Methods 25: 402–408, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Masri FA, Xu W, Comhair SA, Asosingh K, Koo M, Vasanji A, Drazba J, Anand-Apte B, Erzurum SC. Hyperproliferative apoptosis-resistant endothelial cells in idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 293: L548–L554, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morin FC 3rd. Ligating the ductus arteriosus before birth causes persistent pulmonary hypertension in the newborn lamb. Pediatr Res 25: 245–250, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mueller CF, Laude K, McNally JS, Harrison DG. Redox mechanisms in blood vessels. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 25: 274–278, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ou J, Ou Z, Ackerman AW, Oldham KT, Pritchard KA Jr. Inhibition of heat shock protein 90 (HSP90) in proliferating endothelial cells uncouples endothelial nitric oxide synthase activity. Free Radic Biol Med 34: 269–276, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Papapetropoulos A, García-Cardeña G, Madri JA, Sessa WC. Nitric oxide production contributes to the angiogenic properties of vascular endothelial growth factor in human endothelial cells. J Clin Invest 100: 3131–3139, 1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pritchard KA, Ackerman AW, Gross ER, Stepp DW, Shi Y, Fontana JT, Baker JE, Sessa WC. Heat shock protein 90 mediates the balance of nitric oxide and superoxide anion from endothelial nitric oxide synthase. J Biol Chem 276: 17621–17624, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rozen S, Skaletsky H. Primer3 on the WWW for general users and for biologist programmers. Methods Mol Biol 132: 365–386, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sakao S, Taraseviciene-Stewart L, Lee JD, Wood K, Cool CD, Voelkel NF. Initial apoptosis is followed by increased proliferation of apoptosis-resistant endothelial cells. FASEB J 18: 1178–1180, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sgonc R, Boeck G, Dietrich H, Gruber J, Recheis H, Wick G. Simultaneous determination of cell surface antigens and apoptosis. Trends Genet 10: 41–42, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stenmark KR, Abman SH. Lung vascular development: implications for the pathogenesis of bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Annu Rev Physiol 67: 623–661, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Subhedar NV, ShawNJ. Changes in pulmonary arterial pressure in preterm infants with chronic lung disease. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 82: F243–F247, 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Terranova VP, Hujanen ES, Loeb DM, Martin GR, Thornburg L, Glushko V. Use of reconstituted basement membrane to measure cell invasiveness and select for highly invasive tumor cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 83: 465–469, 1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thébaud B, Abman SH. Bronchopulmonary dysplasia: where have all the vessels gone? Roles of angiogenic growth factors in chronic lung disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 175: 978–985, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ushio-Fukai M, Alexander RW. Reactive oxygen species as mediators of angiogenesis signaling. Role of NAD(P)H oxidase. Mol Cell Biochem 264: 85–97, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zeltner TB, Caaduff JH, Gehr P, Pfenninger J, Burri PH. The postnatal development and growth of the human lung. I. Morphometry. Respir Physiol 67: 247–267, 1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhao H, Joseph J, Fales HM, Sokoloski EA, Levine RL, Vasquez-Vivar J, Kalyanaraman B. Detection and characterization of the product of hydroethidine and intracellular superoxide by HPLC and limitations of fluorescence. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 5727–5732, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]