Abstract

This article reviews the findings of three trials of male circumcision for HIV prevention, with emphasis on the public health impact, cultural and safety concerns, implications for women, and the challenges of roll out. Three randomized trials in Africa demonstrated that adult male circumcision reduces HIV acquisition by 50% to 60%. As circumcision provides only partial protection, higher risk behaviors could nullify circumcision's effect. Additionally, circumcision among HIV-infected men does not directly reduce male-to-female HIV transmission among discordant couples, according to the results of a recent Ugandan study. The roll-out or full-scale implementation requires committed expansion into existing HIV prevention programs. Efforts should include attention to safety, implications for women, and risk compensation. Rapid, careful establishment of circumcision services is essential to optimize HIV prevention in countries with the highest prevalence.

Introduction

Male circumcision, or surgical removal of the complete or partial foreskin of the penis, is one of the oldest known surgical interventions. Historically motivated by religious and societal beliefs or medical necessity, circumcision has been considered variously a manifestation of faith; a means to hygiene [1]; an induction into manhood; and a preventive strategy against sexually transmitted infections (STIs) [2], urinary tract infections, and masturbation [3]. Circumcision is routinely performed among Jewish and Muslim populations and is common among men in the United States, where its use has been controversial [4]. Now recent data from three randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of circumcision for the prevention of HIV indicate that adult male circumcision dramatically reduces the risk of HIV acquisition among heterosexual African men by 50% to 60% [5••–7••], an effect stronger than that seen among some vaccines commonly used to prevent other illnesses.

The concept and design of this triumvirate of studies was founded on decades of observation that suggested circumcision is associated with decreased prevalence of HIV infection, STIs, and penile cancer [8,9,10•,11–13]. Another protective effect associated with circumcision is an apparent decreased risk of HIV and STIs in female partners of culturally circumcised men, attributed to a reduction in disease prevalence. In this fashion, circumcision has been perceived as protective for men and women. Among the prospective observational studies, the adjusted relative risk for protection against HIV acquisition among circumcised men varies (0.52–0.14) [14]. RCT findings have prompted strong support of circumcision as a new intervention against HIV. As such, a surgical measure to prevent infectious disease is an unprecedented milestone in the history of public health.

Convincing Epidemiologic Data and Biologic Plausibility

Described extensively elsewhere [15–21], observational data derived from comparisons of populations with varying circumcision practices have suggested that circumcision can protect against some STIs. The rapid emergence of the heterosexual epidemic of HIV in sub-Saharan Africa brought attention to the diverse geographic distribution of HIV prevalence. Regions of routine circumcision seemed less affected by HIV, whereas far greater prevalence was noted among populations in Southern and East Africa, where circumcision rates are low. Following this pattern, low HIV prevalence was seen in the Muslim countries of North and West Africa, where circumcision is practiced routinely. Other benefits of circumcision have included decreased rates of urinary tract infection among young boys [22] and a reduced prevalence of cervical cancer among long-term sexual partners of circumcised men [23,24].

Although the high prevalence of HIV among uncircumcised men was consistent with previously noted trends in STIs, behavioral and cultural confounders could not be excluded among the circumcised populations. Despite possible confounding, the biologic mechanism of circumcision’s protection against HIV and STIs seemed quite plausible: removal of a foreskin that may trap genital fluids from partners could reduce prolonged exposure to infectious agents, leading to a lower infection rate. Removal of the subpreputial mucosa, a site prone to abrasion during sexual activity and rich in HIV target cells, could reduce the relative number of viral entry pathways.

RCT Results

These compelling observational data set the stage for a structured evaluation to determine whether adult male circumcision can prevent HIV. In 2002, three RCTs were launched in Africa to study this question. The studies were performed in South Africa, Kenya, and Uganda [5••–7••], within peri-urban, urban, and rural communities, respectively (Table 1). Auvert et al. [5••] first reported evidence of a protective effect of circumcision. The investigators studied 3128 men 18 to 24 years old in Orange Farm (bordering Johannesburg, South Africa). Eligible men were randomly allocated to undergo immediate or delayed (offered at the end of the follow-up period) circumcision performed by trained general practitioners. Men were assessed at 3, 12, and 24 months for HIV acquisition, STIs, and changes in sexual behaviors. Interim analysis in 2004 revealed a 0.4 RR of HIV acquisition (95% CI, 0.24%–0.68%; P < 0.001) among the circumcised compared with uncircumcised participants. This finding corresponds to a protective effect of 60% among circumcised participants. Given these striking results, the trial was discontinued early by its data safety and monitoring board, and circumcision was offered to the control arm. The results provoked worldwide interest. Circumcision appeared to provide protection against HIV comparable to some commonly used vaccines.

Table 1.

Three randomized controlled trials of circumcision for HIV prevention

| South Africa* | Kenya† | Uganda‡ | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enrollment, n | 3128 | 2784 | 4996 |

| Intervention | 1546 | 1391 | 2474 |

| Control | 1582 | 1393 | 2522 |

| Age range, y | 18–24 | 18–24 | 15–49 |

| Median age (interquartile range), y | 21 (19.6–22.5) | 20 (19–22) | N/A§ |

| Community setting | Peri-urban | Urban | Rural |

| Follow-up | 3, 12, 24 mo | 1, 3, 6, 12, 18, 24 mo | 6, 12, 24 mo |

| HIV incidence circumcised/100 person-years, % (n) | 0.85 (20) | 2.1 (22) | 0.66 (22) |

| HIV incidence control/100 person-years, % (n) | 2.1 (49) | 4.2 (47) | 1.33 (45) |

| Percent protection (intent-to-treat analysis) | 60% | 53% | 51% |

| As-treated protection¶ | 76% | 60% | 60% |

| Adverse events | 54 (3.8%) | 21 (1.5%) | 178 (7.6%) |

Of note, risk compensation (higher risk taking due to perceived protection) was observed in the intervention group, with an 18% increase in the number of sexual partners among the circumcised men. All five measured risk behaviors increased among the circumcised, although only one risk behavior (mean number of sexual partners) increased significantly. The RR of HIV infection among the circumcised was preserved even when controlling for higher risk behavior. These behavioral findings raised concern for risk compensation as circumcision is made widely available.

The Orange Farm results prompted ethical concerns about continuation of the two remaining studies. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommended continuation but mandated a previously unplanned, earlier interim evaluation. WHO expressed concern that efficacy estimates may have been increased artificially in the Orange Farm trial due to early discontinuation. (Effect sizes derived from clinical trials discontinued prematurely may be falsely amplified.) Conclusive data were warranted before declaring an irreversible surgical procedure as an effective health care intervention.

At the interim evaluation, the studies in Kenya [6••] and Uganda [7••] provided evidence of protection against HIV infection of 50% to 60%, remarkably similar to the results from the Orange Farm trial. Both trials were discontinued prematurely on December 12, 2006. Together, the three studies demonstrate a 50% to 60% reduction in HIV acquisition by medicalized circumcision (Table 1). The studies suggested that circumcision may be protective against some STIs (urethral STIs were not affected). The South African and Kenyan trials showed a nonsignificant trend toward STI prevention by testing for herpes simplex virus (HSV)-2, gonorrhea, chlamydia, and trichomonas (results for trichomonas are available only for the Kenyan study). The diagnostics do not tell the full story, as circumcised men in the Kenyan study experienced genital warts nearly seven times less commonly than men randomized to control. These circumcised men also experienced genital ulcer disease (GUD) roughly half as commonly as the uncircumcised men [25]. Likewise, the Ugandan trial indicated that circumcision was significantly protective against GUD. Uniquely among the three trials, the Ugandan study alone showed a significant reduction in HSV-2 acquisition [26].

The Kenyan trial included 2784 men ages 18 to 24 years in an urban setting of approximately 500,000 residents [6••]. The population is 98% Luo, an ethnic group that does not practice routine circumcision. Subjects were followed-up at 1, 3, 6, 12, 18, and 24 months after randomization. At 2 years, incidence of HIV infection was 2.1% (95% CI, 1.2–3) in the circumcision arm versus 4.2% in the control arm (P = 0.0065). The RR for the circumcised participants was 0.47 (95% CI, 0.28–0.78) when controlling for age, sexual risk behaviors, and baseline variables between study arms. This RR equals a risk reduction of 53%. The as-treated analysis (excluding HIV-positive subjects at baseline) resulted in an RR for circumcision of 0.4 (95% CI, 0.23–0.68), or 60% efficacy among the circumcised.

The largest among the three studies of circumcision enrolled 4996 men in the rural district of Rakai, Uganda, and included a broader subject age range (15–49 years) to capture men before sexual debut and older men, who might differ in sexual behaviors (Table 1) [7••]. The 24-month incidence rates for HIV infection were 0.66/100 person-years and 1.33/100 person-years in the circumcision versus control arms, respectively. The incidence rates equal a 51% efficacy (95% CI, 16%–72%; P = 0.006) against HIV infection. Accounting for crossovers in an as-treated analysis (men who elected circumcision despite randomization to control arm), efficacy increased to 55% (95% CI, 22%–75%; P = 0.003). No differential risk compensation was observed. The trial also provided convincing evidence for protection against symptomatic GUD and HSV-2. The incidence rate ratio for self-reported GUD symptoms was 0.53/100 study visits (95% CI, 0.4–0.6) with an HSV-2 acquisition rate of 7.6% in the intervention (circumcised) arm compared to 10.1% in the control arm (RR 0.75, 95% CI, 0.59–0.96; P = 0.02) [26].

Safety

Circumcision is associated with risk, but rates of complication were low in hospital or clinical settings. Across the three studies, adverse events (AEs) were infrequent (1.5%–7.6%) and included infection, bleeding, hematoma, wound dehiscence, swelling, anesthetic reactions, inadequate tissue removal, pain, penile damage, erectile dysfunction, and dissatisfaction regarding appearance. Men in the intervention arms of the three studies experienced AE rates of 1.5%, 3.8%, and 7.6% across the Kenyan, South African, and Ugandan trials, respectively. Although the overall rate for AEs in the Ugandan trial was higher, the moderate AE rate (3%) was comparable to the other two studies. Overall, complications appeared to be higher among HIV-positive men, although trends across studies were not statistically significant. In South Africa, HIV-positive men experienced more AEs (P = 0.059). In part, this finding was reflected in Uganda, where HIV-positive men resuming sex before complete wound healing were found to have increased risk for grade 2 and 3 infections [27].

Although the rates of periprocedural AEs were low in the trials, AE frequency might rise as circumcision is introduced as a larger public health initiative. The highly controlled environment of a clinical trial could underestimate the morbidity of circumcision when implemented in the real-world setting. During roll out, a higher frequency of complications may occur if attention to asepsis and postsurgical follow-up is not maintained. Repeat use or inadequate sterilization of surgical instruments and lack of procedural experience are phenomena of surgery in resource-poor settings that increase surgical risk. Further, significant delays in access to circumcision may result in the pursuit of alternatives offered by traditional healers or poorly trained doctors. Beyond controlled surgical environments, AE rates are known to be higher. Complications of circumcisions in these settings can be devastating and may include partial or full penile amputation, gangrene, and death.

Circumcision as a Public Health Intervention

The consistency and convincing nature of the findings in these trials has led to rapid acceptance of male circumcision within the public health community. In March 2007, WHO and the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS), guided by HIV prevention experts and the trial investigators, issued a formal statement of support for adult male circumcision as a strategy against HIV infection [28••], which is estimated to result in a subsequent decrease in transmission to women. They emphasized the following points:

Male circumcision should be regarded as another valuable intervention to reduce the heterosexual acquisition of HIV infection in men.

Male circumcision should be included within comprehensive HIV prevention efforts.

Appropriate training, surgical asepsis, postoperative follow-up, and prevention counseling are essential to the success of the procedure.

The public health effectiveness of circumcision could be profound. Modeling studies estimate that the public health impact of circumcision in sub-Saharan Africa could prevent 5.7 million new HIV infections and 3 million deaths over 20 years.

In all studies, circumcision provided partial protection against HIV. Transmission events did occur among circumcised men, at rates of 0.7 to 1/100 person-years. Events occurred even with emphasis on HIV prevention with condoms, education, and treatment of STIs. More robust prevention programs are necessary and must accompany circumcision programs. WHO and UNAIDS have strongly encouraged the international community to provide resources for infrastructure development and training to roll-out circumcision efforts in African countries with the highest HIV prevalence.

Cost-Effectiveness and the International Commitment

With these noted caveats about safety, circumcision appears to be an epidemiologist’s dream come true: a quick procedure (usually lasting 20 minutes) that offers protection rivaling some currently available vaccines. The cost per HIV infection avoided (HIA) has been compared with the cost efficacy of preventing mother-to-child transmission ($20,000–$21,000) [14] and to the lifetime expense of HIV care with or without antiretroviral therapy. Several factors influence the cost-effectiveness of circumcision: 1) baseline prevalence of HIV within the population; 2) fraction of the male population receiving medicalized circumcision (coverage); 3) duration of follow-up observation (eg, 5, 10, 20 years); and 4) number of men needed to be circumcised to prevent one HIV infection (ie, number needed to treat). The Orange Farm study suggests that 308 infections would be prevented for every 1000 circumcisions performed over 20 years, assuming a stable epidemic [29]. Assumptions include a baseline male HIV prevalence of 25.6%, efficacy of 60%, coverage of 25%, and costs due to AEs and behavioral disinhibition. When adjusted for savings due to treatment of HIV/AIDS prevented over a lifetime, the cost per HIA is $181, with a total savings of $2.4 million [29]. In fact, cost savings will likely surpass this estimate when prevention of female infection is considered.

Gray et al. [30] approached this question of cost-effectiveness using a stochastic simulation model. Variables included the risk of transmission per sex act and number of sex partners per year for HIV-positive men and women, all at varying rates of circumcision coverage. For example, with a circumcision efficacy of 60% and program coverage of 75%, 19 procedures are necessary per one HIA. This translates into a cost per HIA of $1269. Across studies, costs and number of procedures per HIA range widely. Variation across estimates are as high as 10-fold greater than the cost per HIA in South Africa estimated by Kahn et al. [29]. Given the considerable range in cost estimates, careful reassessment of resources required during implementation periods will best inform long-term costs.

Prevention and treatment of HIV is considered by many to be a global health responsibility. Male circumcision is an attractive public health measure. However, sustainability will depend on cooperative efforts among affected countries and global donors. Source and home countries must establish and fulfill commitments to the long-term costs of circumcision and continue support of existing HIV treatment and prevention programs to reach coverage goals. National strategic plans for circumcision program development are warranted [31]. Further, implementation should be prompt. Rates of acceptability among affected populations currently are high, but enthusiasm among communities may fade if accessing circumcision is difficult. Roll out must follow a structured and rapid implementation phase to maximize population benefit.

Epidemiologic Impact

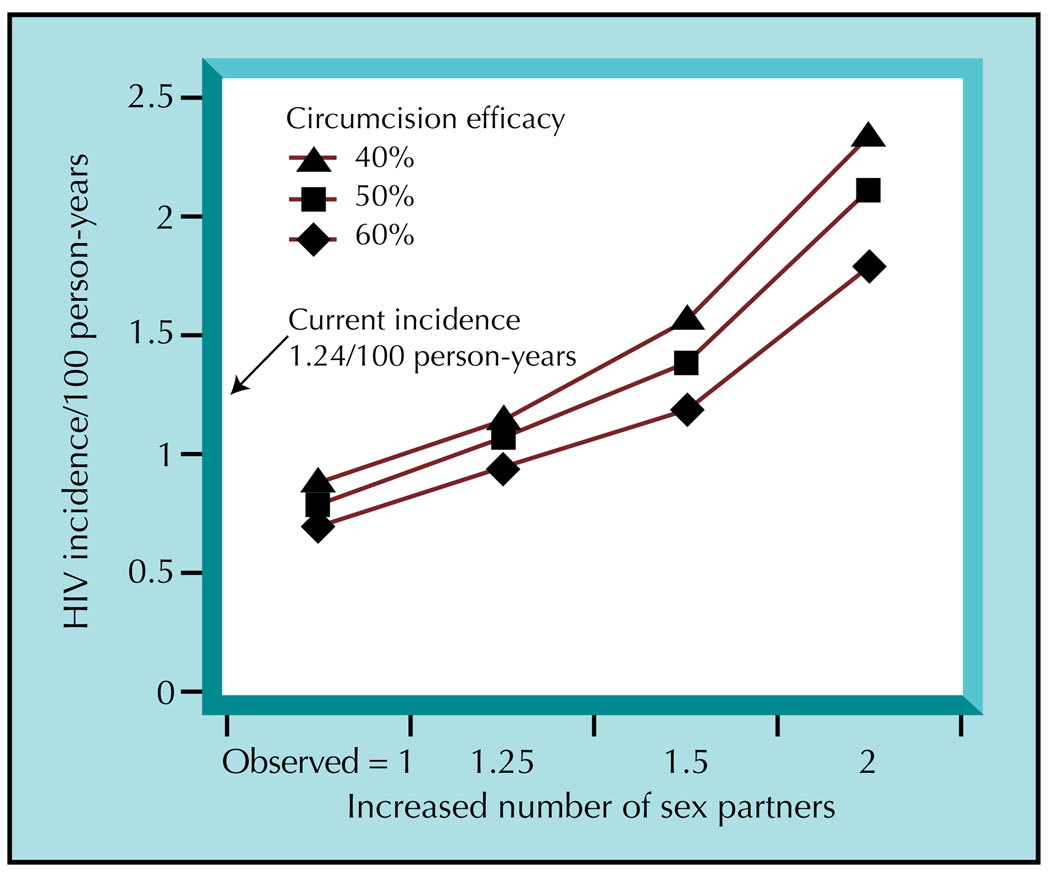

Circumcision’s effect on the HIV epidemic could be profound, but its potential impact largely depends on the degree of program coverage and baseline HIV prevalence in highly affected areas. Using Botswana as an example, modeling suggests a reduction in female prevalence from 40% to 20% and in male prevalence from 30% to 10%, if program coverage rises from 10% to 80% over 10 years [32]. When program uptake is low (50%), HIV prevalence decreases from 40% to 30% among women and 30% to 20% among men. Another analysis using stochastic modeling estimated the potential impact of circumcision according to incidence rates and increasing number of sexual partners (Fig. 1) [30]. In this model, assumptions included a baseline HIV incidence of 1.24 cases/100 person-years and circumcision efficacy of 60%. Results suggested a decrease in incidence to 1/100 person-years among men and 0.98/100 person-years among women. Coverage of 75% would decrease HIV incidence to 0.96 and 0.92/100 person-years among men and women, respectively. With 75% coverage, acquisition of HIV across both sexes would drop from 1.24 to 0.67/100 person-years. Interestingly, greater impact was observed among Ugandan men with higher risk behaviors. The mechanism behind this observation is uncertain.

Figure 1.

Population-level incidence with an increase in number of sexual partners and varying degrees of circumcision efficacy for HIV prevention, assuming 75% program coverage. (From Gray et al. [30], with permission.)

Changes in population prevalence due to circumcision will take time; 10 to 20 years are necessary for a reduction in transmission dynamics sufficient to influence population disease burden. In the long term, some investigators indicated that circumcision in sub-Saharan Africa could prevent 5.7 million new infections and 3 million deaths over 20 years, as coverage increases from 37% to 100% [33]. All told, this intervention could reduce HIV prevalence in sub-Saharan Africa by 4.1 million over 20 years. Indeed, if assumptions regarding sexual behavior, including behavioral disinhibition, are accurate, sustainable circumcision programs could curtail the epidemic. Feasible male circumcision programs could dramatically change the new “set-point” of HIV incidence and prevalence over less than a generation.

These estimates of epidemiologic impact generally assume an ideal structured community setting. Whether the circumcision efficacy observed in the trials will translate into HIV prevention effectiveness in the real world is controversial. Plans for circumcision roll out must also account for the age of men or boys prioritized for surgery. For example, circumcising infants is associated with the lowest surgical risk and no risk compensation, but within some communities this practice has long been unacceptable. Neonatal as compared with adult circumcision may be more effective against HIV, but the public health effect would be delayed until after sexual debut. This translates into an approximate 15-year delay in epidemiologic impact.

In contrast, circumcision of sexually active adult men would have an immediate effect on the HIV epidemic, with a tradeoff of greater risk of surgical AE and behavioral compensation. A distinct benefit of adult male circumcision is the opportunity to offer voluntary counseling and testing for HIV, as well as additional sexual health education. According to some, circumcision during adolescence, before sexual debut, could carry the greatest impact but would require parental consent [34•]. Yet, such procedural timing would reflect the age at which ritual circumcision is performed as an initiation into manhood. Continuation of this practice through traditional healers and/or associated risk compensation (the latter known to be high during adolescence) could nullify the protection offered by circumcision.

Post-Trial Acceptability and Cultural Implications

These estimates of public health impact are promising. The RCT results were received enthusiastically throughout sub-Saharan Africa. However, the epidemiologic effect of male circumcision as a prevention method also largely depends on its acceptability among men and their sexual partners. Several studies in sub-Saharan Africa document high acceptability rates [7••,35–40]. Populations assessed in focus groups were eager to participate in a low-cost procedure to protect themselves against HIV and STIs and to improve male hygiene.

Events in Swaziland, a country with the world’s highest known HIV prevalence (40%), reflect these findings. Circumcision was banned by a Swazi king in the 19th century; therefore, most Swazi men are uncircumcised. After announcement of the South African RCT results, the Family Life Association of Swaziland began offering circumcision services. Even with two new doctors for fulltime circumcision, the clinic has found it difficult to keep up with the demand for services [41]. Wait-listed men have even stormed the clinic, demanding circumcision.

The procedure is now popular beyond all expectations among the general population in AIDS-afflicted sub-Saharan Africa. In fact, 68% to 89% of male and female parents in African countries studied would be willing to have their male children circumcised in a hospital setting. A study of 238 uncircumcised men (median age 29) in Botswana revealed that safety and cost are concerns among men considering circumcision. Among the men surveyed, 61% said they would definitely or probably pursue circumcision if the procedure were free and performed in a hospital. An educational session increased the cohort’s acceptability to 81%. Of these men, 90% wanted circumcision in a hospital [40].

Circumcision may introduce new social stigma for men with HIV. WHO/UNAIDS recommends that services be provided to HIV-negative men only, as there are currently no data to suggest that circumcision among HIV-positive men will protect women. Increased circumcision coverage among HIV-negative men may provoke a new stigma against those who remain uncircumcised. Communities and potential sexual partners may perceive all uncircumcised men to be HIV-positive and likewise, may be fooled into thinking a circumcised man is HIV-negative. For this reason, HIV-positive men may accept the risks of serious complications by seeking circumcision services from untrained providers or traditional healers, if they are unable to access safer services after roll out [42]. Roll-out efforts should be prepared to address this potential stigma and emphasize that a man’s decision regarding circumcision does not reflect HIV status independently.

Implications for Women

Public health experts are concerned about the effects of medicalized circumcision on women, given the concern for misinformation about the partial (rather than complete) protection and the overall status of women within resource-poor countries. These concerns for women’s health persist and are discussed infrequently as the latest global spotlight in public health surrounds a male-centered HIV prevention strategy. The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation sponsored a trial among discordant couples to evaluate HIV and STI outcomes in Ugandan women who are partners of HIV-positive men (The Randomized Trial of Male Circumcision: STD, HIV, and Behavioral Effects in Men, Women, and the Community) to address such concerns. Conducted in Rakai, Uganda, the trial assessed male-to-female transmission of HIV and STIs, the societal impact of circumcision, and modification in sexual behavior. The latter includes a particular focus on risk compensation.

The results were disheartening. Circumcision of HIV-infected men did not directly reduce male-to-female HIV transmission. The 24-month HIV incidence rates for women partners of HIV-infected men were 13.8/100 person-years in the male circumcision arm and 9.6/100 person-years in the control arm (P = 0.42). No reductions were noted in genitourinary symptoms among the women [43]. Further, during the immediate postoperative period, there was an increased rate of transmission events to women by HIV-positive male partners who returned to sex at least 5 days before certified wound healing. As a result, the WHO and UNAIDS statement in March 2007 included an advisory that circumcision of HIV-infected men is not recommended for direct HIV prevention in women on an individual basis. Male circumcision will translate into protection for women in settings with high HIV prevalence and extensive circumcision coverage. In these settings, the population-level risk for HIV infection among women will decrease as the prevalence decreases among men, due to lower risk of a woman’s risk exposure to an HIV-infected man.

Despite the disappointing results of the study among HIV-infected men for prevention of male-to-female HIV transmission, there is optimism that circumcision of HIV-infected men does extend other benefits to women’s health. For example, the Rakai circumcision study found a reduction in the risk for GUD among female partners of circumcised men compared with uncircumcised HIV-infected men, which could indirectly reduce HIV acquisition in women. Until now, there had been few data about circumcision’s effect on STI risk in female partners, and no prospective studies had been conducted to date. One prior observational study suggested that there may be protection against some STIs for women [44]. In an earlier study in Rakai, Uganda, 44 women with circumcised HIV-positive male partners and 299 women with uncircumcised HIV-positive partners were studied for HIV and STI transmission. Circumcision was associated with a reduced risk of prevalent trichomonas (prevalence RR [PRR] 0.65, 95% CI, 0.55–0.77), bacterial vaginosis (PRR 0.86, 95% CI, 0.8–0.93) and GUD (PRR 0.73, 95% CI, 0.53–0.98) among women with circumcised partners. Circumcision did not modify the risk of HIV, syphilis, chlamydia, or gonorrhea. A subsequent, larger study among almost 6000 African and Thai women (the HC-HIV Study) found no association between male partner circumcision status and the female risk of gonorrhea, chlamydia, or trichomonas [45].

Both Rakai trials augment these earlier data. The concurrent circumcision trials showed protection against GUD among women partners of HIV-uninfected (RR 0.78, 95% CI, 0.63–0.97) and HIV-infected men (PRR 0.64, 95% CI, 0.49–0.85) randomized to immediate circumcision [26,43]. Further, circumcision of HIV-negative men protected against trichomonas (RR 0.52, 95% CI, 0.05–0.98), incident bacterial vaginosis (BV) (PRR 0.8, 95% CI, 0.65–0.97), severe BV (Nugent scores 9–10; RR 0.39, 95% CI, 0.24–0.64), and persistent BV (PRR 0.82, 95% CI, 0.72–0.96). These results are consistent with the prior observational study findings reported by the Rakai investigators [43].

The benefits of male circumcision to women’s health likely do not end here. Strong evidence suggests that circumcision also may reduce male prevalence of human papillomavirus (HPV) and thereby reduce male-to-female transmission of HPV types [46,47]. Observational studies indicate a lower prevalence of oncogenic penile glans and coronal sulcus HPV infection [48] and cervical cancer among women with circumcised partners [23]. By decreasing women’s risk of oncogenic HPV type infection, circumcision may prevent cervical cancer.

In regions of high HIV prevalence, women’s health will likely benefit from male circumcision. Although circumcision of HIV-infected men seems unsuccessful in preventing direct male-to-female HIV transmission, women will find indirect protection as the population prevalence of HIV decreases with increasing coverage of medicalized circumcision services for men. New data indicate that circumcision of men, regardless of HIV status, protects women against GUD. Furthermore, results of prospective studies assessing circumcision’s effect on HPV infection in women are ongoing. Any measure to reduce HPV-related cervical disease will contribute considerably to improve women’s health in developing countries, where cervical cancer is the second most common cause of cancer-related death.

Implications for Men Who Have Sex With Men

The potential role of circumcision in HIV transmission among men who have sex with men (MSM) is not known and requires further investigation. Few observational studies exist, and results are conflicting [49–52]. Prior study indicates that receptive anal sex with an HIV-infected partner confers the greatest risk in MSM [53]. However, risk of HIV acquisition according to sexual role (ie, insertive versus receptive unprotected anal intercourse) does not appear to be associated with circumcision status, according to recent studies from Australia [54] and the United States [55]. For the insertive partner in penile-to-anal sex, it is unknown whether exposure to anal secretions and bleeding due to mucosal trauma leads to exposure to greater HIV viral loads than in penile-to-vaginal sex. If viral exposure is indeed greater in penile-to-anal sex, any protective effect of circumcision may be mitigated or nullified [56]. There are few ecologic studies of male circumcision and HIV risk in MSM, but surveys among MSM indicate acceptability for future study. In the Andean region, willingness to participate in circumcision study is high among MSM, particularly in large cities [57•]. Concerns about circumcision among the Andean men included having surgery, AEs such as pain and swelling, and the potential for partners to force unprotected sex. Although circumcision is not recommended for prevention of HIV acquisition in MSM, any role remains unknown. Trials remain under debate in light of concerns for safety.

Resource Mobilization

Recent projections for roll-out costs vary. An early statistical model by Auvert et al. [58••] estimates that costs could range from $397 million in public costs to $922 million in private costs across sub-Saharan Africa for the first 5 years of the roll out. These estimates include 16 countries and account for multiple factors, including male-to-female and female-to-male transmission, cost and availability of antiretroviral therapy, percent of newborns surviving to adulthood, and preexisting country infrastructure. In the model, costs over the next 5 years after roll out (years 6–10) decline to $208 million in public costs and $235 million in private costs.

The expansion of sustainable programs will not be easy in Africa. Lack of infrastructure presents challenges to any concerted international cooperation. However, efforts have begun. In March 2007, WHO and UNAIDS recommended provision of low-cost or free circumcision to adult men in countries with high HIV prevalence. Donor organizations such as the World Bank; the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria; and the US government have offered assistance. Also, UNAIDS recently promised $15 million to expand circumcision services in countries expressing interest. US funding is contingent upon cooperative in-country and WHO program development. Any large-scale public health intervention is bound to meet with complications. Yet abrupt barriers to care may reduce public interest in circumcision and could ultimately jeopardize long-term impact if men encounter long waiting periods or high procedural costs. Clearly, the need for carefully designed, consistent support of these programs is essential and should be a key priority in coordinated roll-out efforts.

Conclusions

An effective HIV vaccine remains a distant dream, but circumcision appears to be a near dream come true in HIV prevention efforts. Is circumcision the answer to the HIV epidemic? The answer is simple: alone, it can never be the solution. Circumcision should be combined with other preventive methods, such as condom use, early diagnosis and treatment, prevention of vertical transmission, optimization of care to HIV-positive individuals, and continued community education. Circumcision holds greater potential to influence the course of the HIV epidemic than any single intervention to date. Yet, to realize this dream, we must face the harsh realities of budget limitations and the dire need for improved health care infrastructure in resource-poor countries. It is also unclear how this intervention will affect women, who represent 52% of the world’s population and the fastest-growing demographic of newly infected individuals in sub-Saharan Africa. However, there is now reason for great optimism in HIV prevention. Swift action tempered by prior experience in HIV treatment and prevention measures can ensure that our reason for hope becomes a reality. Attacking HIV is a global responsibility, and now we have a new weapon. Let us use it wisely.

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors have reported no potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article.

References and Recommended Reading

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as:

• Of importance

•• Of major importance

- 1.O’Farrell N. Soap and water prophylaxis for limiting genital ulcer disease and HIV-1 infection in men in sub-Saharan Africa. Genitourin Med. 1993;69:297–300. doi: 10.1136/sti.69.4.297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gray R, Azire J, Serwadda D, et al. Male circumcision and the risk of sexually transmitted infections and HIV in Rakai, Uganda. AIDS. 2004;18:2428–2430. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hodges FM. The antimasturbation crusade in antebellum American medicine. J Sex Med. 2005;2:722–731. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2005.00133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Academy of Pediatrics. Report of the Task Force on Circumcision. Pediatrics. 1989;84:388–391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Auvert B, Taljaard D, Lagarde E, et al. Randomized, controlled intervention trial of male circumcision for reduction of HIV infection risk: the ANRS 1265 Trial. PLoS Med. 2005;2:e298. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020298. Report of the South African circumcision trial prematurely discontinued in 2005 for approximately 60% reduced risk of HIV acquisition. When controlling for behavioral and genital symptoms, the protective effect was 61% (95% CI, 34%–77%)

- 6. Bailey RC, Moses S, Parker CB, et al. Male circumcision for HIV prevention in young men in Kisumu, Kenya: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2007;369:643–656. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60312-2. Report of the Kenyan circumcision trial discontinued prematurely in 2006, which found a 53% (95% CI, 22%–72%) reduction in HIV acquisition among circumcised men. Controlling for nonad-herence to study arm and baseline HIV infection, the protective effect increased to 60% (32%–77%). This study provides a thorough description of methods, analysis, and results, including the rate and types of AEs. The work is an example of medicalized circumcision conducted in an urban setting.

- 7. Gray RH, Kigozi G, Serwadda D, et al. Male circumcision for HIV prevention in men in Rakai, Uganda: a randomized trial. Lancet. 2007;369:657–666. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60313-4. Report of the Ugandan circumcision trial discontinued prematurely in 2006. The study found a 51% (95% CI, 16%–72%) reduction in HIV acquisition among circumcised men. Accounting for crossovers, the protective effect increased to 55% (22%–75%). The report includes a thorough description of methods, analysis, and results, including the rate and types of AEs. This study is an example of medicalized circumcision conducted in a rural setting.

- 8.Moses S, Bradley JE, Nagelkerke NJ, et al. Geographical patterns of male circumcision practices in Africa: association with HIV seroprevalence. Int J Epidemiol. 1990;19:693–697. doi: 10.1093/ije/19.3.693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moses S, Plummer FA, Bradley JE, et al. The association between lack of male circumcision and risk for HIV infection: a review of the epidemiological data. Sex Transm Dis. 1994;21:201–210. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199407000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Siegfried N, Muller M, Deeks J, et al. HIV and male circumcision—a systematic review with assessment of the quality of studies. Lancet Infect Dis. 2005;5:165–173. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(05)01309-5. A Cochrane systematic review of articles published before 2004 evaluating the association between circumcision and HIV acquisition in heterosexual men. Most evaluated studies suggest a protective effect of circumcision. This study provides a useful quality critique of the studies. Significant heterogeneity among observational studies prevented full meta-analysis, and confounding by behavior, cultural, or religious practice could not be excluded.

- 11.Auvert B, Buve A, Lagarde E, et al. Male circumcision and HIV infection in four cities in sub-Saharan Africa. AIDS. 2001;15 Suppl 4:S31–S40. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200108004-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weiss HA, Quigley MA, Hayes RJ. Male circumcision and risk of HIV infection in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS. 2000;14:2361–2370. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200010200-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schoen EJ, Oehrli M, Colby C, Machin G. The highly protective effect of newborn circumcision against invasive penile cancer. Pediatrics. 2000;105:E36. doi: 10.1542/peds.105.3.e36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bailey RC. Scaling up circumcision programmes: the road from evidence to practice [plenary]; Presented at 4th Annual International AIDS Society Conference; July 24; Sydney, Australia. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moses S, Bailey RC, Ronald AR. Male circumcision: assessment of health benefits and risks. Sex Transm Infect. 1998;74:368–373. doi: 10.1136/sti.74.5.368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fink AJ. A possible explanation for heterosexual male infection with AIDS. N Engl J Med. 1986;315:1167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gray RH, Kiwanuka N, Quinn TC, et al. Male circumcision and HIV acquisition and transmission: cohort studies in Rakai, Uganda. Rakai Project Team. AIDS. 2000;14:2371–2381. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200010200-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lavreys L, Rakwar JP, Thompson ML, et al. Effect of circumcision on incidence of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 and other sexually transmitted diseases: a prospective cohort study of trucking company employees in Kenya. J Infect Dis. 1999;180:330–336. doi: 10.1086/314884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cameron DW, Simonsen JN, D’Costa LJ, et al. Female to male transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1: risk factors for seroconversion in men. Lancet. 1989;2:403–407. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)90589-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reynolds SJ, Shepherd ME, Risbud AR, et al. Male circumcision and risk of HIV-1 and other sexually transmitted infections in India. Lancet. 2004;363:1039–1040. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15840-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mehendale SM, Rodrigues JJ, Brookmeyer RS, et al. Incidence and predictors of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 seroconversion in patients attending sexually transmitted disease clinics in India. J Infect Dis. 1995;172:1486–1491. doi: 10.1093/infdis/172.6.1486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Singh-Grewal D, Macdessi J, Craig J. Circumcision for the prevention of urinary tract infection in boys: a systematic review of randomised trials and observational studies. Arch Dis Child. 2005;90:853–858. doi: 10.1136/adc.2004.049353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Castellsague X, Bosch FX, Munoz N, et al. Male circumcision, penile human papillomavirus infection, and cervical cancer in female partners. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1105–1112. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Castellsague X, Bosch FX, Munoz N. The male role in cervical cancer. Salud Publica Mex. 2003;45 Suppl 3:S345–S353. doi: 10.1590/s0036-36342003000900008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bailey RC. Male circumcision: The road from evidence to practice [plenary]; Presented at the 4th Annual International AIDS Society Conference on HIV Pathogenesis, Treatment, and Prevention; July 22–25; Sydney, Australia. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tobian A, Serwadda D, Quinn T, et al. Trial of male circumcision: prevention of HSV-2 in men and vaginal infections in female partners, Rakai, Uganda [abstract 28LB]; Presented at the 15th Annual Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; February 3–6; Boston, MA. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kigozi G. The safety of adult male circumcision in HIV-infected and uninfected men in Rakai, Uganda [presentation WEAC101]; Presented at the 4th International AIDS Society Meeting; July 25; Sydney, Australia. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Statement on Kenyan and Ugandan Trial Findings Regarding Male Circumcision and HIV. Joint Statement by the World Health Organization (WHO), the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), the World Bank and the UNAIDS Secretariat. [Accessed December 11, 2007]; Available at http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/statements/2006/s18/en/index.html. Provides a clear policy statement from WHO/UNAIDS endorsing circumcision as an intervention among heterosexual men in countries of sub-Saharan Africa, where HIV is highly prevalent. Discusses circumcision roll out and remaining uncertainties surrounding the efficacy of circumcision among HIV-positive men in male-to-female transmission. The statement also carefully details important cultural and safety considerations.

- 29.Kahn JG, Marseille E, Auvert B. Cost-effectiveness of male circumcision for HIV prevention in a South African setting. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e517. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gray RH, Li X, Kigozi G, et al. The impact of male circumcision on HIV incidence and cost per infection prevented: a stochastic simulation model from Rakai, Uganda. AIDS. 2007;21:845–850. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3280187544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sawires SR, Dworkin SL, Fiamma A, et al. Male circumcision and HIV/AIDS: challenges and opportunities. Lancet. 2007;369:708–713. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60323-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nagelkerke NJ, Moses S, de Vlas SJ, Bailey RC. Modelling the public health impact of male circumcision for HIV prevention in high prevalence areas in Africa. BMC Infect Dis. 2007;7:16. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-7-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Williams BG, Lloyd-Smith JO, Gouws E, et al. The potential impact of male circumcision on HIV in Sub-Saharan Africa. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e262. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Rennie S, Muula AS, Westreich D. Male circumcision and HIV prevention: ethical, medical and public health tradeoffs in low-income countries. J Med Ethics. 2007;33:357–361. doi: 10.1136/jme.2006.019901. A useful commentary on the ethical implications of male circumcision, with considerations of pros and cons of circumcision according to age, sexual debut, and autonomy. Debates various concerns surrounding the roll out of circumcision and is a useful guide to understanding the implications of the recent trial findings.

- 35.Bailey RC, Plummer FA, Moses S. Male circumcision and HIV prevention: current knowledge and future research directions. Lancet Infect Dis. 2001;1:223–231. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(01)00117-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mattson CL, Bailey RC, Muga R, et al. Acceptability of male circumcision and predictors of circumcision preference among men and women in Nyanza Province, Kenya. AIDS Care. 2005;17:182–194. doi: 10.1080/09540120512331325671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lagarde E, Dirk T, Puren A, et al. Acceptability of male circumcision as a tool for preventing HIV infection in a highly infected community in South Africa. AIDS. 2003;17:89–95. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200301030-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Scott BE, Weiss HA, Viljoen JI. The acceptability of male circumcision as an HIV intervention among a rural Zulu population, Kwazulu-Natal, South Africa. AIDS Care. 2005;17:304–313. doi: 10.1080/09540120412331299744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lukobo MD, Bailey RC. Acceptability of male circumcision for prevention of HIV infection in Zambia. AIDS Care. 2007;19:471–477. doi: 10.1080/09540120601163250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kebaabetswe P, Lockman S, Mogwe S, et al. Male circumcision: an acceptable strategy for HIV prevention in Botswana. Sex Transm Infect. 2003;79:214–219. doi: 10.1136/sti.79.3.214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Harrison R. Circumcision makes a comeback in Swaziland. The Swazi Observer. 2006 March 6; [Google Scholar]

- 42.Meissner O, Buso DL. Traditional male circumcision in the Eastern Cape--scourge or blessing? S Afr Med J. 2007;97:371–373. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wawer M, Kigozi G, Serwadda D, et al. Trial of male circumcision in HIV-positive men, Rakai, Uganda: Effects in HIV-positive men and in women partners [abstract 33LB]; Presented at the 15th Annual Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; February 3–6; Boston, MA. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gray R, Wawer M, Thoma M, et al. Male circumcision and the risks of female HIV and sexually transmitted infections acquisition in Rakai, Uganda [abstract 128]; Presented at the 13th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; February 5–8; Denver, CO. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Turner AN, Morrison CS, Padian NS, et al. Male circumcision and women’s risk of incident chlamydial, gonococcal and trichomonal infections. [abstract 449]; Presented at the 17th Meeting of the International Society for Sexually Transmitted Diseases Research; July 30; Seattle, Washington. 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lajous M, Mueller N, Cruz-Valdez A, et al. Determinants of prevalence, acquisition, and persistence of human papillomavirus in healthy Mexican military men. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14:1710–1716. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-04-0926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vaccarella S, Lazcano-Ponce E, Castro-Garduno JA, et al. Prevalence and determinants of human papillomavirus infection in men attending vasectomy clinics in Mexico. Int J Cancer. 2006;119:1934–1939. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hernandez BY, Wilkens LR, Zhu X, et al. Circumcision and human papillomavirus infection in men: a site-specific comparison. J Infect Dis. 2008 doi: 10.1086/528379. (Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Buchbinder SP, Vittinghoff E, Heagerty PJ, et al. Sexual risk, nitrite inhalant use, and lack of circumcision associated with HIV seroconversion in men who have sex with men in the United States. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;39:82–89. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000134740.41585.f4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Grulich AE, Hendry O, Clark E, et al. Circumcision and male-to-male sexual transmission of HIV. AIDS. 2001;15:1188–1189. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200106150-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Klausner J, Kent C, Kohn R. Male circumcision in STD clinic patients, San Francisco, 1996–2005; Presented at the 2006 National STD Prevention Conference; May 8–11; Jacksonville, FL. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kreiss JK, Hopkins SG. The association between circumcision status and human immunodeficiency virus infection among homosexual men. J Infect Dis. 1993;168:1404–1408. doi: 10.1093/infdis/168.6.1404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Varghese B, Maher JE, Peterman TA, et al. Reducing the risk of sexual HIV transmission: Quantifying the per-act-risk for HIV on the basis of choice of partner, sex act, and condom use. Sex Transm Dis. 2002;29:38–43. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200201000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Templeton DJ, Jin F, Prestage GP, et al. Circumcision status and risk of HIV seroconversion in the HIM cohort of homosexual men in Sydney [abstract WEAC103]; Presented at the 4th Annual International AIDS Society Conference; July 25; Sydney, Australia. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Millett GA, Ding H, Lauby J, et al. Circumcision status and HIV infection among Black and Latino men who have sex with men in 3 US cities. Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;46:643–650. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31815b834d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sullivan PS, Kilmarx PH, Peterman TA, et al. Male circumcision for prevention of HIV transmission: What the new data mean for HIV prevention in the United States. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e223. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Guanira J, Lama JR, Goicochea P, et al. How willing are gay men to “cut off” the epidemic? Circumcision among MSM in the Andean region [abstract WEAC102]; Presented at the 4th Annual International AIDS Society conference; July 25; Sydney, Australia. 2007. Although this study of 2048 MSM did not reveal differences in HIV status according to circumcision, acceptance of a future clinical trial of circumcision to prevent HIV among MSM was high.

- 58. Auvert B, Kahn J, Korenromp E, et al. Cost of the roll-out of male circumcision in sub-Saharan Africa [abstract WEAC105]; Presented at the 4th International AIDS Society Meeting; July 25; Sydney, Australia. 2007. Using data from the Orange Farm circumcision study [5••], the authors created a costing tool for circumcision implementation. This analysis provides preliminary estimates for the cost of roll out. The model was used to calculate net roll-out costs for 14 sub-Saharan countries where circumcision prevalence is low and HIV prevalence is high (> 5%). It provides estimates according to public versus private roll-out settings. The private and public costs of implementation in Africa during the first 5 years were $922 million and $397 million, respectively.