Abstract

Human purine nucleoside phosphorylase (PNP) belongs to the trimeric class of PNPs and is essential for catabolism of deoxyguanosine. Genetic deficiency of PNP in humans causes a specific T-cell immune deficiency and transition state analogue inhibitors of PNP are in development for treatment of T-cell cancers and autoimmune disorders. Four generations of Immucillins have been developed, each of which contains inhibitors binding with picomolar affinity to human PNP. Full inhibition of PNP occurs upon binding to the first of three subunits and binding to subsequent sites occurs with negative cooperativity. In contrast, substrate analogue and product bind without cooperativity. Titrations of human PNP using isothermal calorimetery indicate that binding of a structurally rigid first-generation Immucillin (K d = 56 pM) is driven by large negative enthalpy values (ΔH = −21.2 kcal/mol) with a substantial entropic (-TΔS) penalty. The tightest-binding inhibitors (K d = 5 to 9 pM) have increased conformational flexibility. Despite their conformational freedom in solution, flexible inhibitors bind with high affinity because of reduced entropic penalties. Entropic penalties are proposed to arise from conformational freezing of the PNP·inhibitor complex with the entropy term dominated by protein dynamics. The conformationally flexible Immucillins reduce the system entropic penalty. Disrupting the ribosyl 5’-hydroxyl interaction of transition state analogues with PNP causes favorable entropy of binding. Tight binding of the seventeen Immucillins is characterized by large enthalpic contributions, emphasizing their similarity to the transition state. By introducing flexibility into the inhibitor structure, the enthalpy-entropy compensation pattern is altered to permit tighter binding.

Human purine nucleoside phosphroylase (PNP) is required for the catabolism of 6-oxy-(and 2’-deoxy)-nucleosides to free nucleobases for recycling by phosphoribosyl transferases or oxidation to uric acid and excretion. Genetic deficiency of PNP in humans causes deoxyguanosine accumulation in the blood and its conversion to dGTP causes arrest of DNA synthesis and apoptosis specifically in activated T-cells. Human PNP is therefore a target for the treatment of autoimmune disorders and T-cell cancers (1–2).

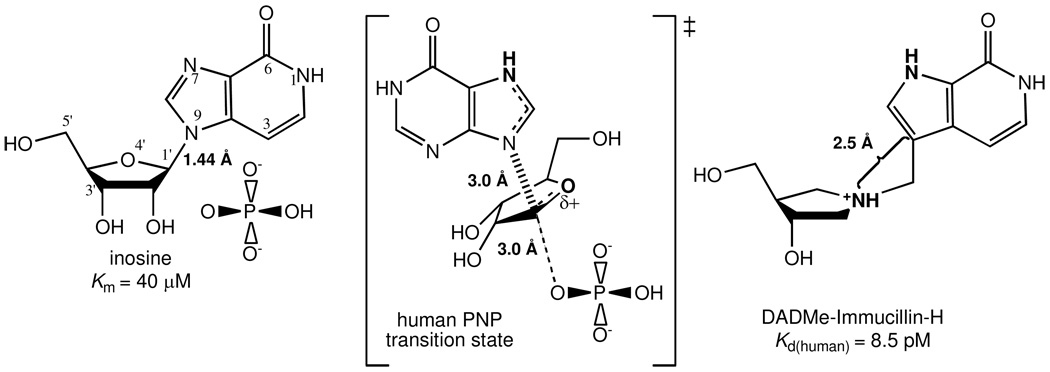

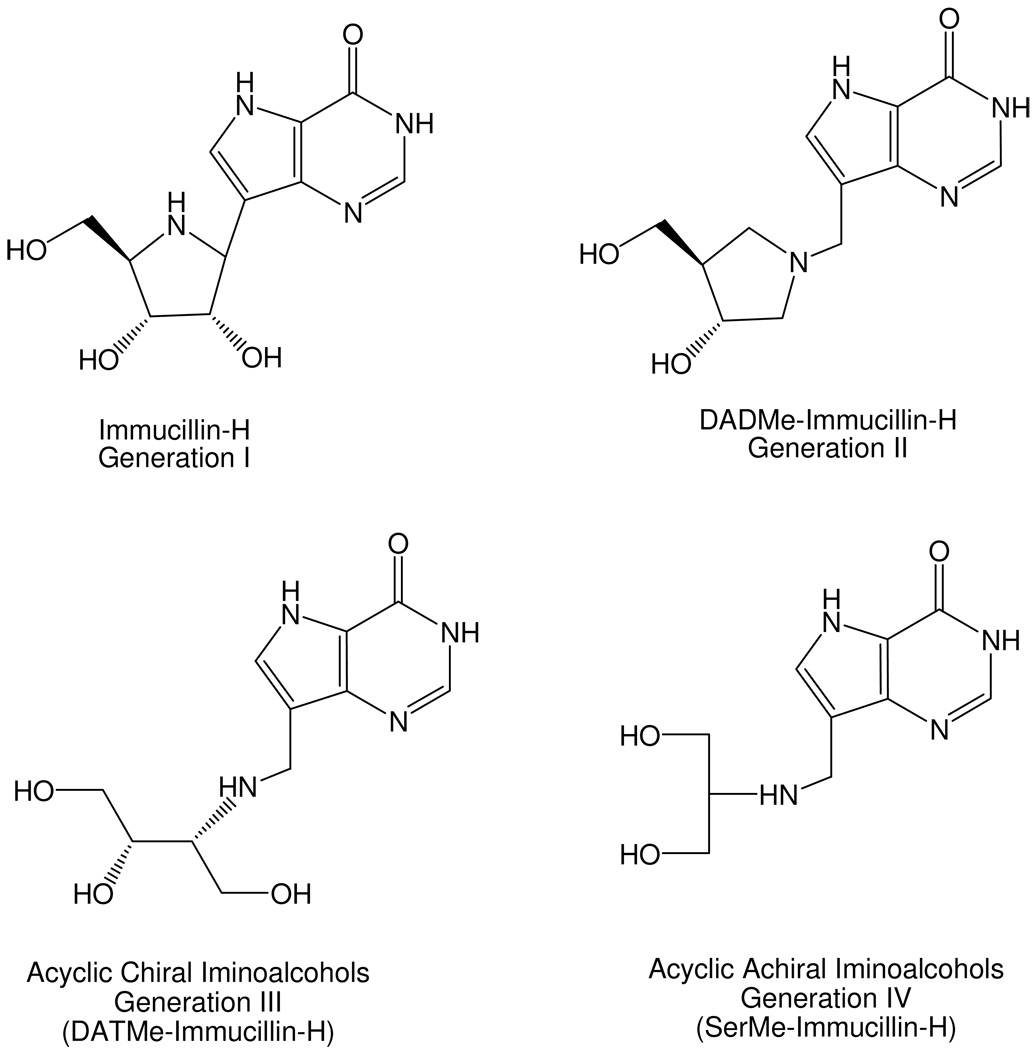

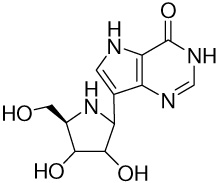

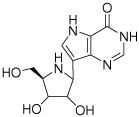

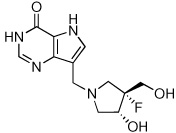

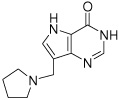

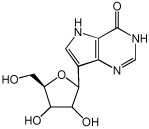

The transition state structure of human PNP has permitted the design of several transition state analogues with picomolar dissociation constants (3–7). The transition state is characterized by a fully-developed ribocation with a C1’ – N9 distance of ≥ 3.0 Å and the phosphate nucleophile at a similar distance to C1’ of the ribosyl cation (Figure 1) (3). Four structurally distinct generations of transition state analogues have been synthesized (Figure 2). The first-generation inhibitor, Immucillin-H (2, Table 1) was designed to mimic the early dissociative transition state of bovine PNP (8, 9). Immucillin-H [(1S)-1-(9-deazahypoxanthin-9-yl)-1,4-dideoxy-1,4-imino-D-ribitol] binds with a K d of 23 pM to the bovine enzyme and with a slightly higher K d of 56 pM to human PNP (4, 9). The fully dissociative (SN1) transition state of human PNP led to the second generation DADMe-Immucillins (4’-deaza-1’-aza-2’-deoxy-1’-(9-methylene)-Immucillins). These include a methylene bridge between the hydroxypyrrolidine mimic of the ribocation and the 9-deazapurine to mimic the fully dissociative transition state of human PNP. DADMe-Immucillin-H (6, Table 1) binds tightly to human PNP, giving a dissociation constant of 8.5 pM (5, 10). The third generation of Immucillins has the ribose ring replaced by an acyclic, chiral ribocation mimic (the acyclic chiral iminoalcohols). The tightest-binding inhibitor in this group is DATMe-Immucillin-H (8, Table 1) with an 8.6 pM dissociation constant for human PNP (5). The fourth generation transition state analogues for human PNP is represented by SerMe-Immucillin-H (4, Table 1), an acyclic, achiral mimic of the ribocationic transition state with a 5.2 pM dissociation constant for human PNP (7). Complete inhibition of trimeric PNP occurs when transition state analogues bind to only one of the three catalytic sites (9). X-ray structures of PNPs with substrate, product or inhibitor complexes reveal that all sites fill under ligand saturation (11–13). Thermodynamic parameters for Immucillin binding have not been reported, however those for the binding of product and multisubstrate analogue inhibitors to bovine PNP have been published (eg. 14). Here, four generations of transition state analogues and related inhibitors were titrated against human PNP using isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC). Transition state analogue binding to the catalytic sites of PNP occurs with strong negative cooperativity. In contrast, binding of 9-deazainosine, a substrate analogue inhibitor, and hypoxanthine, a product, reveal normal binding isotherms, clearly distinguishing the nature of transition state and ground-state interactions.

FIGURE 1.

Reactants, transition state structure and a transition state analogue of human PNP. Key features of the human PNP transition state include N7 protonation, formation of a ribocation, the 3.0 Å C1’ – N9 distance and the phosphate nucleophile at a similar distance to the ribosyl group. This led to the development of the DADMe-Immucillins. The 9-deazahypoxanthine group provides N7 protonation and chemical stability. A methylene bridge provides the extended geometry and placing the nitrogen at the 1’-position in the pyrrolidine ring provides the electronic mimic the fully dissociative transition state of human PNP. Human PNP also uses 2’-deoxyinosine as substrate, justifying the 2’-deoxy structure in the DADMe-Immucillin-H transition state analogue.

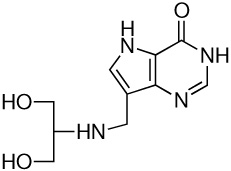

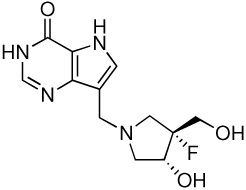

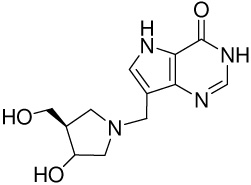

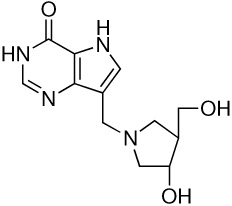

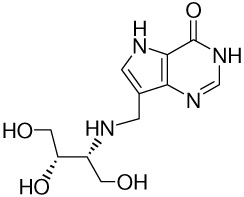

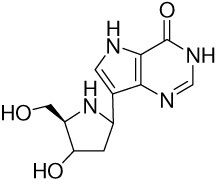

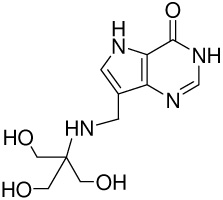

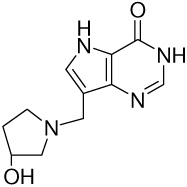

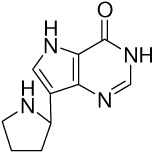

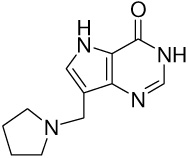

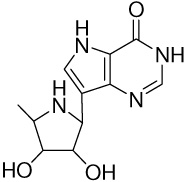

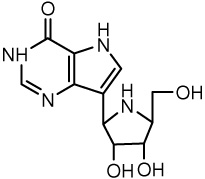

FIGURE 2.

Four generations of PNP transition state analogue inhibitors. Immucillin-H was designed to mimic the bovine PNP transition state. DADMe-Immucillin-H is a mimic of the human PNP transition state. The acyclic, chiral iminoalcohols provide the three hydroxyl groups found in Immucillin-H and the aminocation functionality to mimic features of the fully dissociated transition state of human PNP. The acyclic, achiral iminoalcohols provide the two hydroxyl groups as in DADMe-Immucillin-H and provide ease of synthesis. These inhibitors have dissociation constants in the pM range (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Thermodynamics for Binding the Immucillins to the First Subunit of Human PNP Arranged in Order of Increasing Entropy (Negative to Positive ΔS)

| Entry | Structure | Kd(pM)a | ΔG (kcal/mol)b | ΔH (kcal/mol)c | −TΔS (kcal/mol)d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |  |

32 ± 10e | −14.4 ± 0.3 | −22.7 ± 0.4 | 8.3 ± 0.5 |

| 2 |  |

56 ± 15f | −14.1 ± 0.3 | −21.2 ± 0.2 | 7.1 ± 0.4 |

| 3 |

|

210 ± 80g | −13.3 ± 0.4 | −20.4 ± 0.2 | 7.1 ± 0.4 |

| 4 |  |

5.2 ± 0.4h | −15.5 ± 0.1 | −20.2 ± 0.2 | 4.7 ± 0.2 |

| 5 |

|

1820 ± 80e | −12.0 ± 0.04 | −15.6 ± 0.1 | 3.6 ± 0.1 |

| 6 |  |

8.5 ± 0.2g | −15.1 ± 0.02 | −18.6 ± 0.4 | 3.5 ± 0.4 |

| 7 |  |

380 ± 30i | −12.9 ± 0.1 | −16.1 ± 0.2 | 3.2 ± 0.2 |

| 8 |  |

8.6 ± 0.6g | −15.2 ± 0.1 | −17.5 ± 0.2 | 2.3 ± 0.2 |

| 9 |  |

140 ± 10j | −13.5 ± 0.1 | −15.2 ± 0.5 | 1.7 ± 0.5 |

| 10 |  |

620 ±170g | −12.6 ± 0.3 | −13.3 ± 0.5 | 0.7 ± 0.6 |

| 11 |  |

383 ± 6 | −12.9 ± 0.02 | −12.8 ± 0.9 | −0.1 ± 0.9 |

| 12 |  |

840000 ± 110000k | −8.3 ± 0.1 | −7.4 ± 0.3 | −0.9 ± 0.3 |

| 13 |

|

156 ± 72 | −13.5 ± 0.5 | −12.3 ± 0.3 | −1.2 ± 0.6 |

| 14 |  |

53000 ± 2000 | −10.0 ± 0.04 | −8.6 ± 1.0 | −1.4 ± 1.0 |

| 15 |  |

5500 ± 900k | −11.3 ± 0.2 | −9.6 ± 0.2 | −1.7 ± 0.3 |

| 16 |  |

25000 ± 1000j | −10.4 ± 0.04 | −8.5 ± 0.2 | −1.9 ± 0.2 |

| 17 |  |

12000 ± 2000i | −10.9 ± 0.2 | −8.4 ± 0.2 | −2.5 ± 0.3 |

Inhibition assays were performed in 50 mM KH2PO4, pH 7.4, at 25 °C.

The ΔG values were calculated from the inhibition constants using the equation ΔG = RTlnk d.

The ΔH values were determined from ITC titrations of a single subunit on the enzyme in 50 mM KH2PO4, pH 7.4, at 27 °C.

The Gibbs free energy equation was used to calculate −TΔS.

Ref (6)

ref (4)

ref (5)

ref (7)

ref (38)

ref (10)

ref (39).

Materials and Methods

Enzyme Purification and Preparation

His-tagged Human PNP was expressed in E. coli and prepared similar to published procedures (3). Briefly, cells were grown at 37 °C overnight in two 100 mL portions of LB medium with ampicillin (100 µg/mL). This was used to inoculate 40 L of LB medium containing ampicillin and allowed to achieve an OD600 of 0.4–0.6 (3–4 hours). Expression was induced with IPTG (1 mM) for 4 hours at 37 °C. Cells were pelleted and resuspended in 300 mL of 5 mM imidazole, 500 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris-HCl buffer pH 8.0, protease inhibitor (4 tablets EDTA-free protease inhibitor, Roche Diagnostics) and approximately 1 mg each of DNase I (from bovine pancreas, Roche Diagnostics) and lysozyme (from chicken egg white, Sigma-Aldrich). Cells were disrupted twice with a French press. The supernatant from centrifugation (39000 × g, 30 min) was applied to a 50 mL column of Ni-NTA resin (QIAGEN) previously equilibrated with 3 column volumes of 5 mM imidazole, 500 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris-HCl buffer pH 8.0. After washing (3 column volumes of 20 mM imidazole, 10 mM NaCl, 0.4 mM Tris-HCl buffer pH 8.0), His-tagged human PNP was eluted with a 2 to 40% gradient of 1 M imidazole, 500 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris-HCl buffer pH 8.0 in water on an AKTA FPLC (GE Healthcare). Fractions of pure human PNP (by SDS-PAGE) were concentrated to approximately 50 mL by AMICON ultrafiltration, dialyzed against 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0 (48 hr) to give approximately 24 mg/mL PNP. Plastic tubes containing 1.8 mL were frozen rapidly in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C. Human PNP prepared by this method has two-thirds of its sites occupied with hypoxanthine. Hypoxanthine removal was effected by incubation in 100 mM KH2PO4 containing 10 % charcoal (w/v) for 5 minutes followed by centrifugation and filtration (15). Enzyme recovery is typically 80% and the steady-state kinetic properties of the enzyme are unaffected by charcoal treatment.

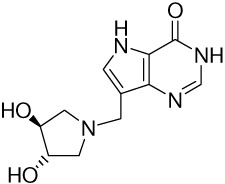

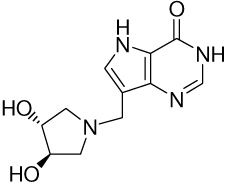

Inhibitors

The Immucillins were prepared and provided as generous gifts from Drs. P. C. Tyler and G. B. Evans of the Carbohydrate Chemistry Team, Industrial Research Ltd., Lower Hutt, New Zealand (eg. 4, 6, 10). Immucillins 13 and 14 were prepared from (3R,4R)-, and (3S,4S)-1-benzylpyrrolidinediol purchased from Aldrich Chemical Co. The benzyls were removed by hydrogenolysis and the resulting amines were treated with 9-deazahypoxanthine and formaldehyde in a Mannich reaction in the same manner we have reported previously to give the substituted 9-deazahypoxanthines (16). 9-Deazainosine was the generous gift of Drs. B. A. Otter and R. S. Kline, Montefiore Medical Center, Bronx, N.Y. (17).

Enzymatic and Inhibition Assays

PNP catalytic activity with inosine as substrate monitored hypoxanthine conversion to uric acid (ε293 = 12900 M−1 cm−1) in a coupled assay containing 0.5 nM PNP, 50 mM potassium phosphate, pH 7.4, and 60 milliunits of xanthine oxidase (from milk, 2.6 M ammonium sulfate suspension; Sigma-Aldrich) (9). Slow-onset inhibition was measured by enzyme (0.2 nM) addition to complete assay mixtures with ≥1 mM inosine and varied inhibitor concentrations. Concentrations were determined from the extinction coefficients (human PNP ε280 = 28830 M−1 cm−1 (Protparam, www.expasy.org), Immucillins ε261 = 9540 M−1 cm−1) (17). Inhibitor concentration was at least 10-fold greater than the enzyme concentration, as required for simple analysis of slow-onset tight-binding inhibition (18). Rates were monitored for 2 hr to determine initial reaction rate and slow onset inhibition (final reaction rate) (9). The K i or K i* values were determined by fitting the initial and/or final steady-state rates and inhibitor concentrations to the expression:

where Vi and Vo are initial (for Ki) or final (for Ki*) steady-state rates in the presence and absence of inhibitor, respectively, KM is the Michaelis constant for inosine, [I] is the free inhibitor concentration and [S] is the substrate concentration. Ki* or Ki values (if no slow onset occurred) are reported as the dissociation constants (eg. Table 1).

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry Studies

Single subunit titrations

Calorimetric titrations of PNP with the Immucillins were performed on a VP-ITC microcalorimeter (MicroCal). Protein samples were dialyzed against 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer pH 7.4. Ligand solutions were dissolved in dialysate, filtered (Millipore 0.2 µm) and the ligand and protein solutions degassed (Microcal Thermovac) for 5 min prior to titrations. The 1.46 mL sample cell was filled with approximately 30 µM PNP (monomer) solution and the injection syringe with ~ 450 µM ligand solution.

Single subunit titrations involved seven or eight 4 µL injections. Each titration was performed six times to obtain an average of the ΔH values. ΔG was based on K i values from inhibition assays described above and the -TΔS term was calculated from the

| (eq 1) |

Trimer titrations

Titrating the PNP trimer with Immucillins used 30 to 35 injections at a rate of 4 µL every 3 min. The data was fit to independent and/or the sequential sites model fitting for three binding sites to give the thermodynamic parameters ΔG, ΔH and -TΔS. When the sequential sites model was used to fit the data, the stoichiometry for binding is assumed to be one per binding site.

Titration of the trimer with 9-deazainosine and hypoxanthine (~700 µM in the injector) used 20 to 50 µM PNP and involved 30 to 60 injections. The data were fit to the independent sites model to yield the thermodynamic parameters and an estimate for the stoichiometry of binding, N.

Data fitting

The equation used to fit data to independent binding sites (used to fit 9-deazainosine and hypoxanthine binding isotherms) is: K = Θ/(1- Θ)[L] Where K is the binding constant, Θ is the fraction of sites occupied by ligand L and [L] is the free ligand concentration and;

Q = [NMtΔHV0/2][1 + Lt/NMt + 1/NKMt - √((1 + Lt/NMt + 1/NKMt)2- 4 Lt/NMt)]

Where Q = total heat; N = stoichiometry; Mt = total PNP concentration and Lt = total ligand concentration. The equation used to fit data to three interdependent binding sites (used to fit Immucillins 5 and 15 binding isotherms) is:

K1 = [ML]/[M][L] ; K2 = [ML2]/[ML][L] ; K3 = [ML3]/[ML2][L]

Q = MtV0[F1ΔH1 + F2(ΔH1 + ΔH2) + F3 (ΔH1 + ΔH2 + ΔH3)]

Where Fi = the fraction of PNP having i bound ligands;

F0 = 1/P; F1 = K1[L]/P; F2 = K1K2[L]2/P; F3 = K1K2K3[L]3/P;

P = 1 + K1[L] + K1K2[L]2 + K1K2K3[L]3

And the heat change in each case is given by

ΔQ(i) = Q(i) + dVi/2V0[Q(i) + Q(i - 1)] - Q(i - 1)

where ΔQ(i) is the heat released from ith injection, Q(i) is the total heat content, dVi is the injection volume and V0 is the active cell volume

Competitive ITC

Competitive titrations were used to determine the thermodynamics for binding Immucillin 2 to the PNP trimer. The enzyme was first titrated with a weaker ligand (Immucillin 15 or 9-deazainosine) followed by displacement titration with Immucillin 2 (a tight ligand) to give apparent Kd and ΔH values (eq. 2 and eq. 3). A separate titration of PNP with Immucillin 2 was used with the following equations to determine the Kdtight and ΔHtight for Immucillin 2 binding all three sites of human PNP (19, 20).

| (eq 2) |

| (eq 3) |

Where ΔHapp, ΔHtight and ΔHweak are the apparent enthalpy of the displacement ITC, the enthalpy change for the tight Immucillin 2, and the enthalpy change for the weak ligand, respectively. Kapp, Ktight and Kweak are the apparent K values for displacement ITC, the K of the tight ligand and the K of the weak ligand, respectively. [Ligandweak] is the free concentration of the preequilibrated weaker-binding ligand.

Control Experiments

Control ITC experiments involved ligand titration into the buffer solution with correction for any heat change using the ‘subtract reference’ function in the Origin 7.0 software. Another control involved titration of the working solution of PNP with Immucillin 2 each day before the start of other titrations. This analysis ensured the protein was fully active for each titration.

Results

Immucillin Binding to the First Catalytic Site of Human PNP

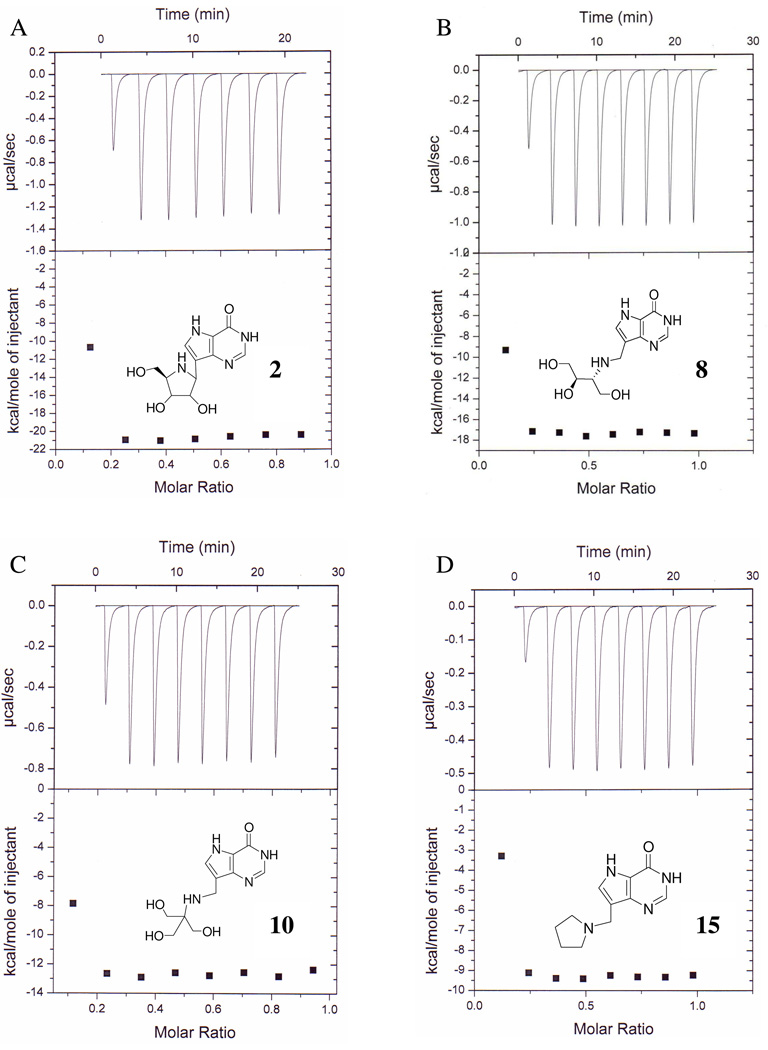

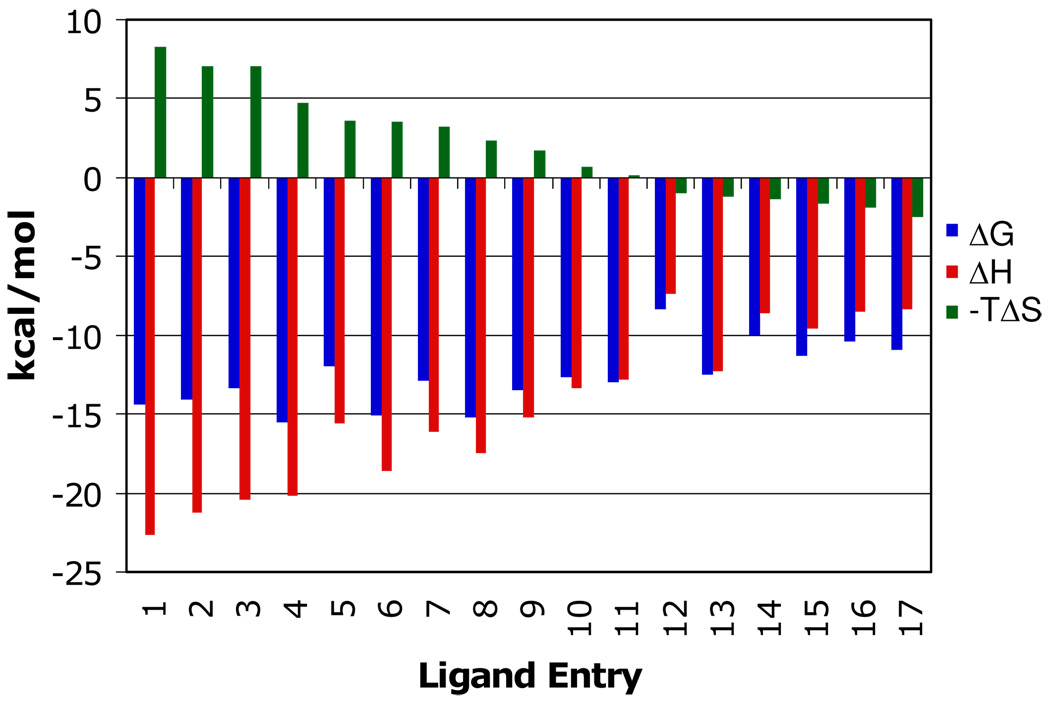

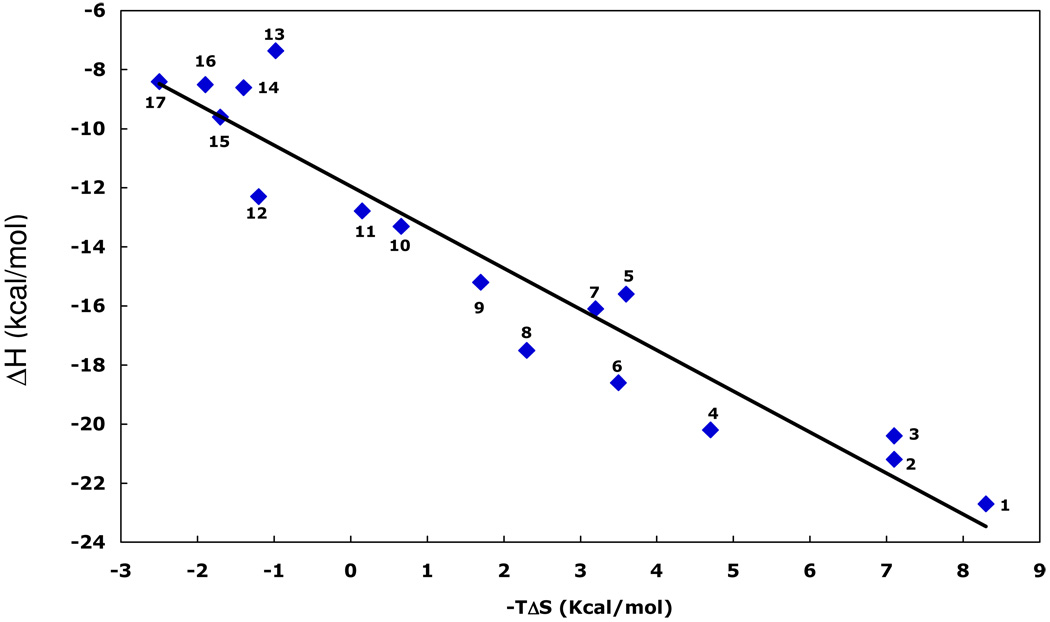

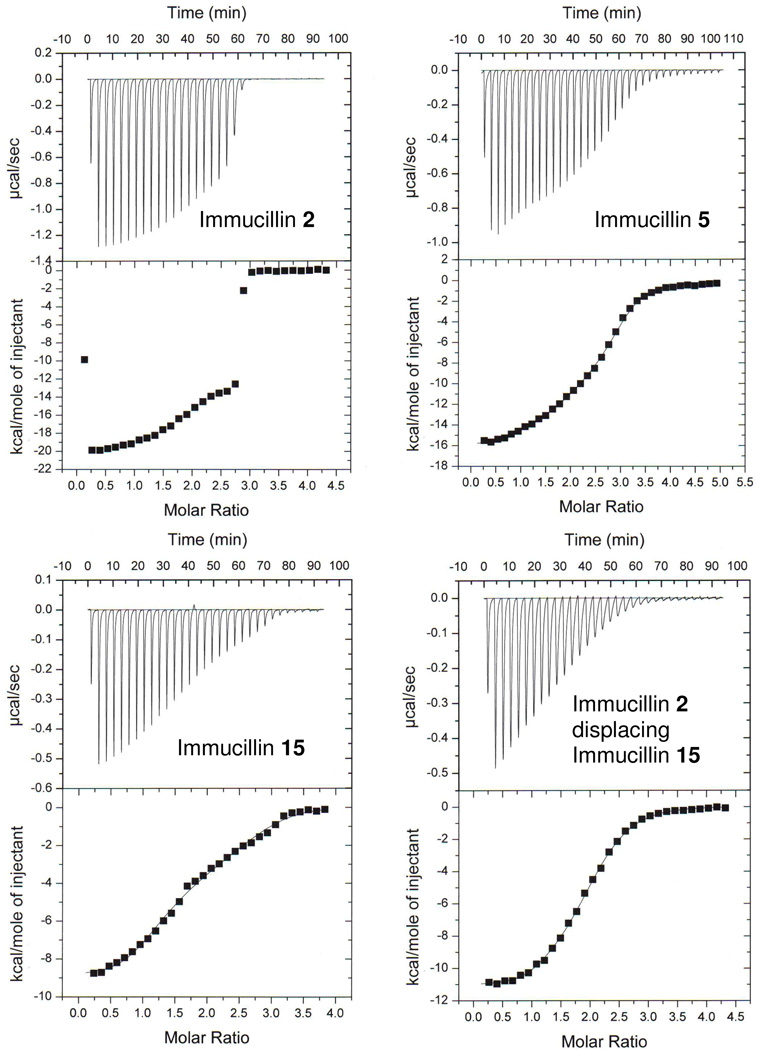

Substoichiometric titration of Immucillins 2, 8, 10 and 15 to the first catalytic site of human PNP caused a constant enthalpy change per injection (Figure 3). The ΔH for binding to the first subunit is calculated from the average of these values (Table 1). Enthalpy changes for these four Immucillins are large and exothermic, from −9.6 to −21.2 kcal/mol (Table 1, Figure 3). Accurate K d values are known from kinetic studies (eg. 5, 10) for these and other Immucillins, permitting resolution of the thermodynamic constants for binding to the first catalytic site of this homotrimer. The same approach was used to establish thermodynamic parameters (ΔH, -TΔS and their contribution to ΔG) for binding of 17 Immucillins to human PNP, arranged in order of TΔS values (Table 1 and Figure 4). Immucillin binding to human PNP is characterized by ΔG values dominated by the enthalpy term, with enthalpies from −7.4 (Immucillin 12) to −22.7 kcal/mol (Immucillin 1). Entropy changes (-TΔS) vary from unfavorable (Immucillins 1 to 9) to slightly favorable (Immucillins 13 to 17) and several Immucillins (10 to 12) bind with entropy changes near zero. The most tightly binding Immucillins (4, 6 and 8) are enthalpy-driven with relatively small penalties in the entropy terms. The relative enthalpy and entropy values for Immucillin binding demonstrate an enthalpy-entropy compensation effect (21–25) (Figure 5). Immucillins with the largest favorable enthalpic values (Immucllins 1 to 9) also show unfavorable entropy changes. Immucillins with favorable entropy changes (Immucllins 13 to 17) also have less favorable enthalpic values and consequently, bind more weakly. Immucillins 4, 6 and 8 reveal less than expected unfavorable entropy terms from a standard enthalpy-entropy compensation plot (Figure 5) and therefore exhibit unusually tight (picomolar) dissociation constants.

FIGURE 3.

Single subunit substoichiometric titrations of human PNP with Immucillins 2 (A), 8 (B), 10 (C) and 15 (D). Titrations provide enthalpic values for inhibitor binding to the first catalytic site of PNP. ΔG values are known from kinetic experiments and the TΔH can be calculated to provide the values of Table 1. With pM to low nM inhibitor dissociation constants and PNP subunit concentrations near 30 µM, there is no significant accumulation of free inhibitor during these substoichiometric titrations.

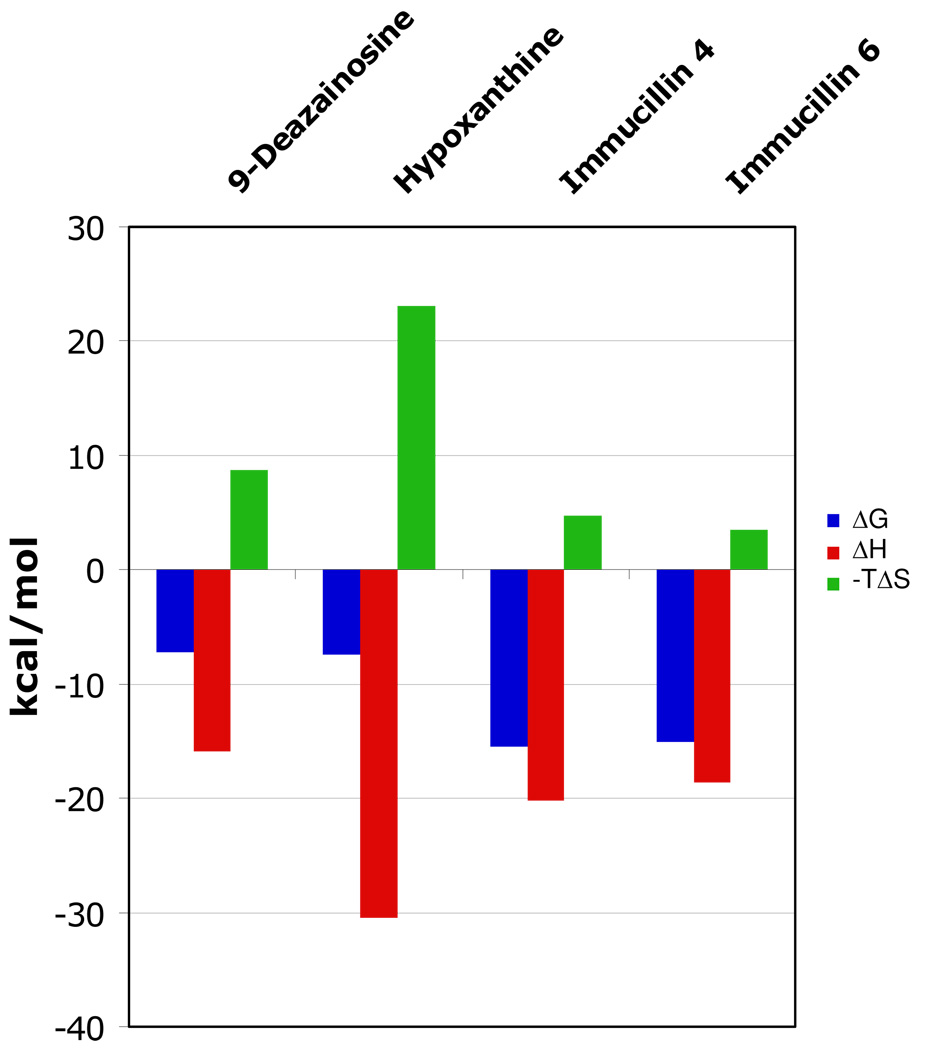

FIGURE 4.

Thermodynamic signatures of Immucillins binding to the first subunit of human PNP (from Table 1). ΔG (blue), ΔH (red) and −TΔS (green). The most tightly bound Immucillins are characterized by enthalpy-driven binding with smaller entropic penalties (Immucillins 1–9). Several Immucillins bind with near-zero entropy (Immucillins 10–12). Immucillins with favorable entropy (Immucillins 13–17) lack the 5’-hydroxyl group, known to interact with catalytically important His257 and to be involved in catalytic site dynamic motion.

FIGURE 5.

Enthalpy-entropy compensation for Immucillin binding to the first subunit of trimeric human PNP. The numbers correspond to the Immucilins in Table 1. Ligands that bind with the most favorable enthalpy (1 to 3) also have the largest unfavorable entropy. Immucillins 4, 6 and 8 show less than the expected unfavorable entropy and are the most tightly bound species. Ligands with favorable entropic contributions (12 to 17) lack the ability to form a normal 5’-hydroxyl interaction at the catalytic site.

Immucillins Bind to Three Sites with Negative Cooperativity

Human PNP is a homotrimer and binding of Immucillins 2, 5 and 15 indicated a stoichiometry of three sites on human PNP and could not be fit to simpler models (Table 2) (Figure 6). Binding of Immucillin 2 is 56 pM for the first catalytic site (Table 1) and demonstrates negative cooperativity at subsequent sites (Figure 6). The tight binding precludes fits of the data to the three sites model. But midpoint analysis for sites 2 and 3 permits estimates of enthalpy changes as these sites fill. The ΔH for first-site binding is −21.2 kcal/mol (Table 1) and as sites 2 and 3 are titrated, the ΔH values at their mid-points are −17.8 and −13.7 kcal/mol respectively (Figure 6). Thus, 3.4 and 7.5 kcal/mol are lost from the cooperative binding enthalpy. The K d values are not available for sites 2 and 3 from this data, but if it is assumed that the –TΔS term remains at 7.1 kcal/mol for second and third-site binding, the K d2 for the second site can be estimated to be 16 nM, more than 200-fold weaker than 2 binding to the first site. Likewise, binding at the third site can be estimated to be 15 µM by the same approximation, but this is likely a poor approximation because of altered entropy as affinity changes. We explored third site affinity by competitive binding experiments (see below).

Table 2.

Thermodynamics for Binding Immucillin 2, 5 and 15 to all Three Subunits of Human PNPa

2b

|

Kd(nM) | 12.0 ± 3.3 | ||

| ΔG (kcal/mol) | −10.9 ± 0.2 | |||

| ΔH (kcal/mol) | −12.9 ± 0.6 | |||

| −TΔS (kcal/mol) | 2.0 ± 0.6 | |||

5c

|

1st Site | 2nd Site | 3rd Site | |

| Kd(nM) | 1.8 ± 0.1d | 64 ± 16 | 667 ± 62 | |

| ΔG (kcal/mol) | −12.0 ± 0.1 | −9.9 ± 0.3 | −8.5 ± 0.1 | |

| ΔH (kcal/mol) | −15.5 ± 0.1 | −13.7 ± 0.2 | −8.4 ± 0.2 | |

| −TΔS (kcal/mol) | 3.5 ± 0.1 | 3.8 ± 0.4 | −0.1 ± 0.2 | |

15c

|

Kd(nM) | 5.5 ± 0.9d | 55 ± 13 | 402 ± 106 |

| ΔG (kcal/mol) | −11.3 ± 0.2 | −10.0 ± 0.2 | −8.8 ± 0.3 | |

| ΔH (kcal/mol) | −9.0 ± 0.1 | −5.0 ± 0.2 | −1.5 ± 0.2 | |

| −TΔS (kcal/mol) | −2.3 ± 0.2 | −5.0 ± 0.3 | −7.3 ± 0.4 | |

ITC titrations were carried out in 50 mM KH2P04, pH 7.4, at 27 °C.

The thermodynamics for binding Immucillin 2 was determined using a competitive titration and reflect average values for the three sites (see Figure 6).

The data was fit using the Three Site Sequential Model provided in the Origin 7.0 software.

Kd values were determined from kinetic inhibition assays described in the methods section.

FIGURE 6.

Full-saturation titrations of human PNP with select Immucillins. Immucillin 2 binds too tightly to the enzyme to permit analytically meaningful fits to three cooperative sites, but the negative cooperativity in enthalpy is apparent in altered ΔH values as the first, second and third sites fill. Titration of Immucillins 5 and 15 were fit to the equation for three sequential sites, with thermodynamic parameters for the first site filling were fixed using the values from Table 1. Thermodynamic parameters for sites 2 and 3 filling, together with those for the first site (from Table 1) are shown in Table 2. Immucillin 2 displacing Immucillin 15 could be fit to an equivalent, independent sites titration curve and the values from this displacement are given in Table 2. The apparent dissociation constant for binding Immucillin 2 to PNP saturated with 15 was solved by the equations for competitive binding at independent sites. PNP trimer concentration was 9.6 µM and free Immucillin 15 at the start of the titration was 6.3 µM. The K d value for Immucillin 15 is assumed to be 402 nM, the dissociation constant for third-site filling for this ligand (Table 2).

Immucillins 5 and 15 also provide examples of negative cooperativity in binding to the three catalytic sites. When the values for K d1 are fixed from the results of Table 1 and the data for full three-sites titration fit to three cooperative sites, thermodynamic values can be estimated for binding to sites 2 and 3. Immucillin 5 binds to the first site with K d1 = 1.8 nM (ΔG = −12 kcal/mol, ΔH = −15.5 kcal/mol and -TΔS = 3.5 kcal/mol) and to the third site with K d = 667 nM (ΔG = −8.5 kcal/mol, ΔH = −8.4 kcal/mol and a -TΔS = −0.1 kcal/mol). Immucillin 15 binds to the first site with a K d = 5.5 nM (ΔG = −11.3 kcal/mol, ΔH = −9.0 kcal/mol and a -TΔS = −2.3 kcal/mol) and to the third site with a K d = 402 nM (ΔG = −8.8 kcal/mol, ΔH = −1.5 kcal/mol and a -TΔS = −7.3 kcal/mol). Immucillin 5 binds with a 370-fold affinity difference for first and third site binding to give a ΔΔG of 3.5 kcal/mol, a ΔΔH of 7.1 kcal/mol and a Δ(-TΔS) of −3.6 kcal/mol. Immucillin 15 binds to the trimer with a 73-fold affinity difference between the first and third sites, a ΔΔG of 2.5 kcal/mol, ΔΔH of 7.5 kcal/mol and a Δ(-TΔS) of −5.0 kcal/mol. Sequential binding of Immucillins 5 and 15 to human PNP results in Gibbs free energy and enthalpy changes that become less favorable as sites fill. However, as enthalpy changes become less exothermic, entropy changes becomes more favorable, in keeping with the enthalpy-entropy compensation effect.

Competitive ITC

Immucillin 2 binds with a 56 picomolar dissociation constant at the first binding site and competitive ITC was used to alter the apparent binding parameters to permit more complete analysis of thermodynamic constants. The relatively weakly-bound Immucillin 15 was used to fully saturate the catalytic sites and thereby provide displacement ligands for the more tightly bound Immucillin 2. Titration of PNP with Immucillin 15 (K d = 5.5, 55 and 402 nM for the first, second and third sites, respectively; Table 1 and Table 2) was followed by a displacement titration where Immucillin 2 (K d = 56 pM for the first site) displaced Immucillin 15. Titration of Immucillin 2 into unliganded PNP only provides estimates for K d2 and K d3 (see above and. Figure 6). Displacement of PNP•Immucillin 15•PO4 with Immucillin 2 follows a normal binding isotherm and gives a competitive K d of 12 nM at each of the three sites (ΔH = −12.9 and –TΔS = 2.0 kcal/mol; Figure 6 and Table 2). The normal binding isotherm indicates that saturation of sites with Immucillin 15 has completed the cooperative transition. With a displacement K d of 12 nM for Immucillin 2 and first-site K d of 56 pM for this ligand, the difference between first and third site binding affinity is approximately 214-fold.

The constants obtained by displacement of 15 represent the affinity of 2 for the first binding site when the remaining two sites are filled with 15. These thermodynamic constants establish a decreased affinity transmitted from sites 2 and 3 which remain filled with 15 as the first site is filled with 2 (Table 2). In contrast, as the third site is filled by 2 with displacement of the last remaining Immucillin 15, the first two sites are filled with 2 to make the binding of 2 to the final site a true K d for PNP fully saturated with 2. Thus, the intrinsic binding difference between sites 1 and 3 for binding of Immucillin 2 is 214-fold. In kinetic studies, filling the first site by 2 causes complete inhibition of PNP, therefore filling the second and third sites is kinetically silent, but the relative affinities are resolved here by the competitive binding approach.

Negative cooperativity for 2 between sites 1 and 3 is caused by a change in thermodynamic interactions. Thus, 2 binding at the first site is an enthalpic event (−21.2 kcal/mol) causing a large loss in entropic freedom (7.1 kcal/mol). Binding of 2 at the third site shows strongly altered thermodynamic properties with an enthalpy of −12.9 and a small entropic penalty of 2.0 kcal/mol. This difference in binding thermodynamics establishes large protein structural reorganization forces driven by transition state mimic contacts at sites 1 and 2.

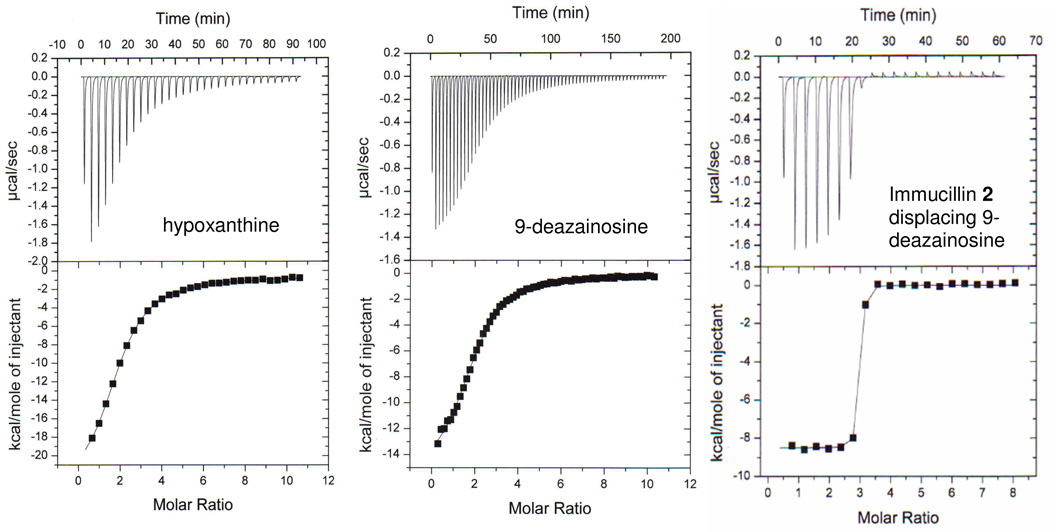

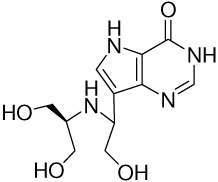

Binding 9-Deazainosine and Hypoxanthine to Human PNP

A nonreactive substrate analogue of inosine, 9-deazainosine, binds to human PNP with an average affinity of 5.4 µM (ΔG of −7.2 kcal/mol). The binding is strongly enthalpy driven (ΔH = −15.9 kcal/mol) with entropic compensation reducing most of enthalpy change (-TΔS = 8.7 kcal/mol). This binding fits to an independent binding sites model but indicates a total binding stoichiometry of approximately two sites. Thus, binding to the third site differs by significantly weaker affinity or a near zero enthalpic change (Figure 7 and Table 3). This departure of the third binding site from the first two is also seen in 15 binding, where sites 1 and 2 are enthalply-driven and site 3 is entropy-driven (Table 1, Table 2).

FIGURE 7.

Titrations of human PNP with 9-deazainosine, hypoxanthine and displacement of 9-deazainosine with Immucillin 2. The titration curves for hypoxanthine and 9-deazainosine were fit to the one set of sites model. 9-Deazainosine (left) and hypoxanthine (middle) bind to two sites with equal affinity and thermodynamic parameters. The stoichiometry of two sites per trimer (Table 3) indicates enthalpically silent or no binding of hypoxanthine or 9-deazainosine to the third site. Displacement of 9-deazainosine by Immucillin 2 establishes tight binding at all three sites with a ΔΔH of −8.4 kcal/mol as 9-deazainosine is displaced. In the displacement (right panel) the PNP trimer was 10 µM (30 µM monomer concentration) and 9-deazainosine concentration at the start of the displacement titration was 170 mM.

Table 3.

Thermodynamics for Binding 9-Deazainosine and Hypoxanthine to Human PNPa

9-Deazainosine

|

N (Stoichiometry) | 1.98 ± 0.017 |

| Kd(µM) | 5.4 ± 0.2 | |

| ΔG (kcal/mol) | −7.2 ± 0.03 | |

| ΔH (kcal/mol) | −15.9 ± 0.2 | |

| −TΔS (kcal/mol) | 8.7 ± 0.2 | |

Hypoxanthine

|

N | 1.72 ± 0.071 |

| Kd(µM) | 4.3 ± 0.3 | |

| ΔG (kcal/mol) | −7.4 ± 0.1 | |

| ΔH (kcal/mol) | −30.5 ± 1.6 | |

| −TΔS (kcal/mol) | 23.1 ± 1.6 |

ITC titrations were carried out in 50 mM KH2PO4, pH 7.4, at 27 °C and the data was fit using the One Set of Sites Model provided in the Origin 7.0 software.

Hypoxanthine binding is similar to 9-deazainosine with independent binding at two sites with an average affinity of 4.3 µM (ΔG = −7.2 kcal/mol) and no enthalpic evidence for binding at the third catalytic site. Hypoxanthine binding differs from 9-deazainosine binding with an extreme enthalpy change (−30.5 kcal/mol) combined with a large and unfavorable entropic component (-TΔS = 23.1 kcal/mol) (Figure 7 and Table 3). Trimeric PNPs are isolated with two moles of tightly bound hypoxanthine, and in the case of the bovine PNP, the K d value has been estimated to be 2 pM for binary PNP•hypoxanthine, an affinity that decreases substantially in the presence of phosphate (26).

Competitive binding of Immucillin 2 to PNP saturated with 9-deazainosine differs substantially from the displacement of Immucillin 15. 9-Deazainosine is isosteric with Immucillin 2, differing only in the substitution of the 4’-oxygen with nitrogen and differing from substrate only in the replacement of N9 by C9 (Table 3). Titration of Immucillin 2 into the PNP•9-deazainosine•PO4 complex occurs with high affinity at all three catalytic sites since no slope change occurs in the ITC titration plots until all three sites are filled (Figure 7). 9-Deazainosine binding occurs with ΔH = −15.9 kcal/mol and –TΔS = 8.7 kcal/mol. When Immucillin 2 displaces 9-deazainosine, an additional −8.3 kcal/mol of ΔH occurs. Since fully occupied enzyme is present throughout the displacement experiment, small entropic terms are expected and the anticipated binding energy would include the ΔG for 9-deazainosine in addition to the ΔH for 2 displacement of 9-deazainosine. This sum gives an expected ΔG for 2 binding of −15.5 kcal/mol or a dissociation constant of 5 pM, fully consistent with the observed displacement curve (Figure 7).

Discussion

Energetics of Transition State Analogue Binding

The physiologically relevant interaction of Immucillins with human PNP is the first catalytic site since full catalytic inhibition occurs when the first site is filled (9). Although the binding is too tight to permit analytic ITC titration analysis, substoichiometric titrations give ΔH values to permit calculation of –TΔS from known dissociation constants. The Immucillins inhibit PNP through enthalpy-driven interactions with a smaller penalty in the entropy term (Table 1). The best transition state analogue inhibitors optimize binding at the first catalytic site through the formation of specific hydrogen bond and ionic interactions. Crystal structures of the trimeric bovine PNP with Immucillin-H (2) and phosphate, reveal at least six new hydrogen bonds and/or ionic interactions compared to the complex with isosteric substrate analogues (11). As each of these interactions is expected to be worth ~2 kcal/mol (~12 kcal/mol total), they readily account for the difference in substrate and transition state binding energy, even with large entropic losses. Entropic penalties for ligand binding can include loss of dynamic flexibility in the inhibitor and/or protein scaffolds and/or altered solvent order and hydrophobic interactions. In summary, crystallographic data support enthalpic interactions with 2 by favorable hydrogen bonds and an ion-pair interaction between the oxygen anion of the phosphate molecule and the N4' of the iminoribitol ring (11; and PDB code: 1rr6).

The entropy changes vary from significantly unfavorable (Immucillins 1 to 9) to near zero (10 to 12) and slightly favorable (13 to 17) with inhibitors of closely related chemical structures. The entropic pattern suggests that the entropic term originates in protein dynamic structure rather than the conformational flexibility states of the inhibitors or the order parameters for water. Changes in water order upon binding of these chemically similar inhibitors is considered to be less likely than altered protein order parameters.

Entropy-Enthalpy Compensation

Depending on the affinity of the Immucillins, a decreased entropic term reveals an enthalpy-entropy compensation pattern such that, with a few exceptions, the larger the ΔH of inhibitor binding, the larger the entropic penalty for binding (Figure 5). Exceptions to the entropy-enthalpy compensation include 4, 6 and 8, all exhibiting less entropic penalty than expected for their large enthalpic driving forces. Each of these has more intrinsic flexibility (rotatable bonds) than does 2, suggesting that inhibitor molecule flexibility is an advantage in maintaining entropic disorder in the PNP-inhibitor complex relative to the more chemically rigid 2 (Table 1).

Effect of the 5’-Hydroxyl Group

Compounds 11 – 17 depart from the others by binding with favorable entropy values to the first site (Table 1). A common feature of these is the lack of a 5’-hydroxyl group in the appropriate geometry to mimic that of the normal substrate and the tight-binding transition state analogues. The 5’-hydroxyl group is proposed (from mutational and computational studies) to be involved in reaction coordinate motion in PNP by orbital steering from its contact with His257 (7, 11). The 5’-hydroxyl neighboring group participation is proposed to act in a promoting vibration to delocalize bonding electrons from the ribosyl group (27). The favorable entropy components of inhibitors 11 to 17 suggest that catalytic site and perhaps neighboring protein motion is organized by the 5’-hydroxyl interaction and that without it, more protein motion occurs, preserving a favorable entropic component. This interaction may not be so apparent in Immucillin 17, which appears to have an intact 5’-hydroxyl (Table 1). However, this ribosyl analogue is in the L-configuration, placing the 5’-hydroxyl group in the wrong position with respect to the 9-deazaadenine ring and His257 when bound. Despite the favorable entropic terms for these compounds, the relatively large loss in enthalpy that occurs with the incomplete ribocation mimics in 11 – 17 results in weaker ΔG values for binding these compounds.

The specific effect of the His257 interaction with the 5’-hydroxyl group is evident by comparing Immucillins 2 and 16 which differ only by the presence of the 5’-hydroxyl group. The removal of the 5’-hydroxyl causes ΔG for binding to become more positive by 3.7 kcal/mol, the sum of the enthalpic and entropic contributions. However, the –TΔS term becomes 9.0 kcal/mol more favorable, interpreted as a large contribution from increased protein dynamics because of the lost interaction to His257.

Negative Cooperativity in Binding

The Immucillins bind human PNP in a negative cooperative manner so that binding to the first site hinders binding at the second and third sites. For Immucillin 5, the entropic penalties are paid on binding to the first two sites with small but favorable entropy for binding at the third site. In contrast, enthalpy for 15 binding to the first two sites is large, favorable and decreases at the third site. In all three sites, the entropic value is favorable. The relatively hydrophobic pyrrole placement into the catalytic site is likely to involve favorable hydrophobic changes and to permit dynamic motion of the protein since all three hydroxyls groups found in Immucillin 2 are missing.

Filling the three binding sites alters the cooperative nature and affinity of the PNP trimer for a transition state analogue. Thus, PNP saturated with Immucillin 15 changes the K d for all bindings of Immucillin 2 to 12 nM, compared to first-site binding of 56 pM. Immucillin 5 binding changes from 1.8 to 667 nM as the three catalytic sites fill. The structural basis for catalytic site cooperativity is likely to involve a catalytic site loop called the Phe159 loop, a flexible loop that must be open for substrates to bind and closes over the PNP Michaelis complex, to help stabilize and exclude water from the catalytic site region (12, 28). The Phe159 loop is the only part of the catalytic site contributed from the neighboring subunit, and creates a physical link between subunit cooperativity and ligand binding.

Non-cooperative Substrate Analogue and Product Binding

The substrate analogue 9-deazainosine binds independently to the first two catalytic sites and is strongly enthalpy-driven with a large entropic penalty. In contrast to transition state analogues, 9-deazainosine is unable to form a ribocation ion pair mimic with the phosphate anion but retains the 2’-, 3’- and 5’-hydroxyl groups, all of which form H-bonds in the catalytic sites. The binding of N9-substutited guanine-based PNP inhibitors has been reported to show similar thermodynamics. For these, micromolar K d values are composed of weak enthalpic forces (ΔH = −6.3 kcal/mol for binding ganciclovir) or are entropically driven as in the cases of acyclovir (ΔG = −6.7 kcal/mol; -TΔS = −5.2 kcal/mol) and 9-benzylguanine (ΔG = −7.8 kcal/mol; -TΔS = −4.2 kcal/mol) (29).

Hypoxanthine binding to PNP in phosphate is remarkably exothermic with a ΔH of −30.5 kcal/mol. Enthalpy changes of this magnitude are usually observed in tightly bound complexes such as the binding of biotin to strepavidin where the enthalpy change is −28.6 kcal/mol (30). Hypoxanthine binding is, however, modest with the large –TΔS of 23.1 kcal/mol giving a K d of 4.3 µM. These values are unlikely to tell the full story of hypoxanthine binding, since two moles of hypoxanthine per trimer are isolated with purified PNP and require charcoal treatment to remove the tightly-bound hypoxanthine.

Weigus-Kutrowska and associates reported hypoxanthine binding to calf spleen PNP in the absence of phosphate to be highly exothermic (ΔH = −14.3 kcal/mol) but the status of tightly bound hypoxanthine in these preparations is unknown (31). Hypoxanthine forms H-bonds with Glu201 and Asp243 and its binding also removes this planar, hydrophobic molecule from solvent and places it in a hydrophobic environment near Phe200, Val245, Val217, Met219 and near Phe159 (contributed from the neighboring subunit; 11, 12). As hydrophobic interactions would contribute to a favorable entropic term and the observed entropy is highly unfavorable, the thermodynamic profile indicates that the binding energy comes primarily from the favorable leaving-group interactions. The entropic penalty of hypoxanthine binding is therefore likely to reside in increased order parameters for the protein.

Why should transition state analogues exhibit strong cooperativity while the substrate analogue and product do notΔ We can speculate that protein conformational collapse around the transition state analogues, structurally identified by at least six new hydrogen and/or ionic bonds relative to ground-state ligands, transmits a structural change via the Phe159 loop, contributed from the neighboring subunit. This reflects the nature of the transition state. In contrast, loose interactions of the Michaelis complexes do not involve tight interactions and do not transmit conformational rigidity to neighboring subunits. Experimental evidence supporting this proposal comes from hydrogen/deuterium exchange in bovine PNP with Immucillin 2 and phosphate bound. Filling of one catalytic site decreased H/D exchange rates in all three subunits (32).

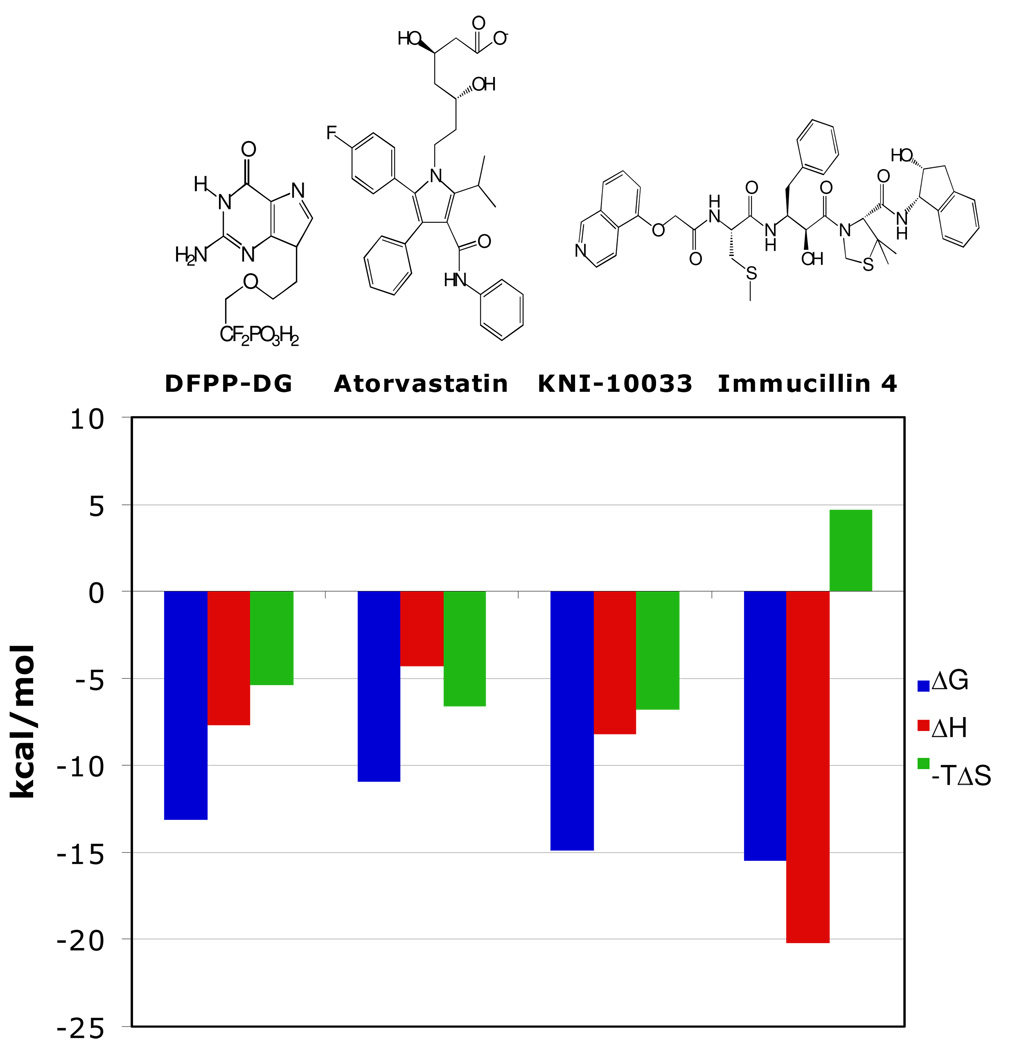

Comparison of Immucillins with Other Inhibitors

Thermodynamic studies on well-characterized systems including the binding of statins to HMG-CoA reductase and the binding of presumptive transition state analogue inhibitors to HIV-1 protease. These inhibitors bind with ΔG values ranging from −9.0 to −14.9 kcal/mol (22, 33–35; Figure 8). For the 13 pM experimental HIV-1 protease inhibitor KNI-10033, the tetrahedral carbon alcohol mimics the intermediate of this aspartyl protease, contributing to favorable enthalpy and the multiple hydrophobic groups of protease inhibitors (exemplified here by KNI-10033) contribute to favorable entropic interactions. This combination provides a remarkable ΔG of −14.9 kcal/mol binding energy.

FIGURE 8.

Thermodynamic inhibitor signatures for comparison with Immucillin 4. DFPP-DG is a bisubstrate analogue of bovine PNP; Atorvastatin (Lipator) is an inhibitor of HMG-CoA reductase and KNI-10033 is an experimental tight-binding (13 pM) inhibitor of HIV-1 protease. DFPP-DG, Atorvastatin and KNI-10033 bind their respective targets with similar contribution from the enthalpy and entropy terms. Immucillin 4 exhibits a larger enthalpy contribution to binding but an entropy penalty. Despite the entropic penalty, the enthalpic elements of transition state binding giving it the greatest affinity of these ligands.

The statins are powerful inhibitors of HMG-CoA reductase in wide use for mediation of blood cholesterol levels. Titration of a type 1 statin (pravastatin) and four type 2 statins (fluvastatin, cerivastatin, atorvastatin and rosuvastatin) with HMG-CoA reductase gave K i values of 2.3 to 256 nM with enthalpy values ranging from zero to −9.3 kcal/mol (33). Thus, the entropic term contributes significantly to all of these interactions. Structures of these drugs include multiple hydrophobic groups, consistent with the favorable entropic partition of the drugs from water to the relative hydrophobic site of HMG-CoA reductase. Energetics of Atorvastatin (Lipitor) binding (Figure 8) exemplify the thermodynamics of statin binding, with the −10.9 kcal/mol ΔG value contributed by a favorable ΔH of −4.3 kcal/mol and a favorable TΔS term contributing even more energy at −6.6 kcal/mol. Thermodynamic analysis of five statins led to the conclusion that binding affinity is correlated with binding enthalpy and the most powerful statins bind with the strongest enthalpies (33).

The tightest binding Immucillins for human PNP are powerfully driven by unusually large enthalpy terms, in several cases, greater than −20 kcal/mol. Thermodynamic interactions of Immucillin 4 compared with Atorvastatin (Lipitor) and KNI-10033 demonstrate the exceptional enthalpy of binding (Figure 8). Entropic penalties in the binding of transition state analogues are unavoidable since the analogues convert the dynamic motions of catalysis into more static binding energy, thus causing substantial increases in protein structural order parameters (36). In contrast to the entropic penalty for Immucillin 4, the substrate analogue DFPP-DG binds with a favorable entropy component, but without the interactions of transition state analogues, it suffers in the enthalpic term.

We know of no other collection of transition state analogues or inhibitors designed by any method to match the large, enthalpy-driven binding features of the Immucillin interactions with PNP. Thermodynamic results support an unusual ability to capture the energetic interactions leading to transition state formation. A fortunate feature of transition state analogue design for PNP is the contrast between the electronically neutral substrates (inosine and guansine) and the cationic transition states. Thus, the ability to mimic the cationic transition state in stable analogues and to form an ion-pair with phosphate at the catalytic sites provides a major contribution to the large enthalpic values for analogue binding to PNP. One specific example of the transition state cation effect is the difference in binding of Immucillin 2 and 9-deazainosine, where the replacement of a single atom, the 4’-nitrogen cation with the 4’-neutral oxygen changes binding affinity from 56 pM to 5.4 µM, a decrease in binding affinity by a factor of nearly 105.

Entropy-Enthlapy Compensation

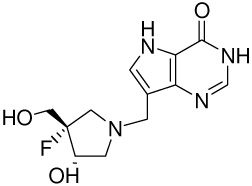

A cruel fact of inhibitor design is that every favorable hydrogen bond or ionic interaction added into a catalytic site inhibitor ligand stabilizes the complex and adds unfavorable entropic contributions to binding. Building flexibility into inhibitors that preserve motion of the protein while maximizing the hydrogen bond and ionic interactions between inhibitor and the catalytic site is one possibility to minimize the entropic penalty. Immucillin 8 contains the three hydroxyl groups present on a ribosyl group or on Immucillin 2, and also the ribocation mimic in the amine functionality. These interactions generate an impressive ΔH of −17.5 kcal/mol while only paying a –TΔS penalty of 2.3 kcal/mol to give a dissociation constant of 8.6 pM. Likewise, Immucillins 4 and 6 have modest entropic penalties (especially when compared to hypoxanthine or 9-deazainosine binding) with large enthalpy walues generated from the favorable features of transition state mimicry (Figure 9). Transition state analogues for mammalian PNPs with binding constants below 10 pM have been termed “the ultimate inhibitors” because a single inhibitor treatment in mice saturates the target PNP and maintains functional inhibition for the lifetime of erythrocytes (25 days in mice; 37).

FIGURE 9.

Thermodynamic signatures for 9-deazainosine, hypoxanthine, and Immucillins 4 and 6 to human PNP. The bars represent ΔG (blue), ΔH (red) and -TΔS (green). The thermodynamic profiles for Immucillins 4 and 6 were taken from the single subunit titration study (Table 1). The signatures for the substrate analogue inhibitor and product are less favorable for binding although the enthalpy terms are large they are compensated by large entropic penalties. These are interpreted as protein organization changes. Immucillins 4 and 6 exhibit thermodynamic signatures are marked by more favorable ΔG values due to larger enthalpy changes and small entropy penalties.

Conclusions

High affinity, specificity and lack of toxicity has made the Immucillins candidates for clinical studies in T-cell related disorders. The tight binding of these analogues to the first subunit on human PNP is characterized by an enthalpy change as large as −22.7 kcal/mol. Tight binding of the transition state analogues comes with entropy penalties interpreted as increased order parameters in the PNP-inhibitor complexes. As transition state features are eliminated from the inhibitors, binding affinity decreases, the entropic penalty decreases and becomes favorable for binding with weaker inhibitors. Tight binding to 8.6 pM occurs when the features of the transition state are preserved in inhibitor design, but flexibility is built into the transition state analogue, presumably, to permit increased dynamic flexibility into the enzyme-inhibitor complex.

Footnotes

Supported by NIH Research Grant GM41916.

References

- 1.Giblett ER, Ammann AJ, Wara DW, Sandman R, Diamond LK. Nucleoside-phosphorylase deficiency in a child with severly defective T-cell immunity and normal B-cell immunity. Lancet. 1975;1:1010–1013. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(75)91950-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ravandi F, Gandhi V. Novel purine nucleoside analogues for T-Cell lineage acute lymphoblastic leukaemia and lymphoms. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs. 2006;12:1601–1613. doi: 10.1517/13543784.15.12.1601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lewandowicz A, Schramm VL. Transition state analysis for human and Plasmodium falciparum purine nucleoside phosphorylases. Biochemistry. 2004;43:1458–1468. doi: 10.1021/bi0359123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Evans GB, Furneaux RH, Lewandowicz A, Schramm VL, Tyler PC. Exploring structure-activity relationships of transition state analogues of human purine nucleoside phosphorylase. J. Med. Chem. 2003;46:3412–3423. doi: 10.1021/jm030145r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taylor EA, Clinch K, Kelly PM, Li L, Evans GB, Tyler PC, Schramm VL. Acyclic ribooxacarbenium ion mimics as transition state analogues of human and malarial purine nucleoside phosphorylases. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:6984–6985. doi: 10.1021/ja071087s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mason JM, Murkin AS, Li L, Schramm VL, Gainsford GJ, Skelton BW. A beta-fluoroamine inhibitor of purine nucleoside phosphorylase. J. Med. Chem. 2008;51:5880–5884. doi: 10.1021/jm800792b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murkin AS, Clinch K, Mason JM, Tyler PC, Schramm VL. Immucillins in custom catalytic-site cavaties. Biorg. Med Chem. Lett. 2008;18:5900–5903. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.08.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kline PC, Schramm VL. Purine nucleoside phosphorylase. Catalytic mechanism and transition-state analysis of the arsenolysis reaction. Biochemistry. 1993;32:13212–13219. doi: 10.1021/bi00211a033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miles RW, Tyler PC, Furneaux RH, Bagdassarian CK, Schramm VL. One-third-the-sites transition-state inhibitors for purine nucleoside phosphorylase. Biochemistry. 1998;37:8615–8621. doi: 10.1021/bi980658d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lewandowicz A, Ringia Taylor EA, Ting L, Kim K, Tyler PC, Evans GB, Zubkova OV, Mee S, Painter GF, Lenz DH, Furneaux RH, Schramm VL. Energetic mapping of transition state analogue interactions with human and Plasmodium falciparum purine nucleoside phosphorylases. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:30320–30328. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505033200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fedorov A, Shi W, Kicska G, Fedorov E, Tyler PC, Furneaux RH, Hanson JC, Gainsford GJ, Larese JZ, Schramm VL, Almo SC. Transition state structure of purine nucleoside phosphorylase and principles of atomic motion in enzymatic catalysis. Biochemistry. 2001;40:853–860. doi: 10.1021/bi002499f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mao C, Cook WJ, Zhou M, Federov AA, Almo SC, Ealick SE. Calf spleen purine nucleoside phosphorylase complexed with substrates and substrate analogues. Biochemistry. 1998;37:7135–7146. doi: 10.1021/bi9723919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Azevedo WF, Jr, Canduri F, Dos Santos DM, Silva RG, De Oliveira JS, De Carvalho LP, Basso LA, Mendes MA, Palma MS, Santos DS. Crystal structure of human purine nucleoside phosphorylase at 2.3 Å resolution. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2003;308:545–552. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)01431-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Breer K, Wielgus-Kutrowska B, Hashimoto M, Hikishima S, Yokomatsu T, Szczepanowski RH, Bochtler M, Girstun A, Staron, Bzowska A. Thermodynamic studies of interactions of calf spleen PNP with acyclic phosphonate inhibitors. Nucleic Acids Symposium Series. 2008;52:663–664. doi: 10.1093/nass/nrn335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ghanem M, Saen-oon S, Zhadin N, Wing C, Cahill SM, Schwartz SD, Callender R, Schramm VL. Tryptophan-free human pnp reveals catalytic site interactions. Biochemistry. 2008;47:3202–3215. doi: 10.1021/bi702491d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Evans GB, Furneaux RH, Tyler PC, Schramm VL. Synthesis of a transition state analogue inhibitor of purine nucleoside phosphorylase via the Mannich reaction. Org. Lett. 2003;5:3639–3640. doi: 10.1021/ol035293q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lim M-I, Ren Y-Y, Otter BA, Klein RS. Synthesis of “9-deazaguanosine” and other new pyrrolo[3,2-d]pyrimidine C-nucleosides. J. Org. Chem. 1983;48:780–788. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morrison JF, Walsh CT. The behavior and significance of slow-binding enzyme inhibitors. Adv. Enzymol. Relat. Areas Mol. Biol. 1988;61:201–301. doi: 10.1002/9780470123072.ch5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang Y, Zhang Z. Low-affinity binding determined by titration calorimetry using a high-affinity coupling ligand: a thermodynamic study of ligand binding to protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B. Analytical Biochemistry. 1998;261:139–148. doi: 10.1006/abio.1998.2738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sigurskjold BW. Exact analysis of competition ligand binding by displacement isothermal titration calorimetry. Analytical Biochemistry. 2000;277:260–266. doi: 10.1006/abio.1999.4402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Williams DH, Stephens E, O’Brien DP, Zhou M. Understanding noncovalent interactions: ligand binding energy and catalytic efficiency from ligand-induced reductions in motion within receptors and enzymes. Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 2004;43:6596–6616. doi: 10.1002/anie.200300644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lafont V, Armstrong AA, Ohtaka H, Kiso Y, Amzel LM, Freire E. Compensating enthalpic and entropic changes hinder binding affinity optimization. Chemical Biology and Drug Design. 2007;69:413–422. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0285.2007.00519.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cole JL, Garsky VM. Thermodynamics of peptide inhibitor binding to HIV-1 gp41. Biochemistry. 2001;40:5633–5641. doi: 10.1021/bi010085w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eastberg JH, Smith McConnell A, Zhao L, Ashworth J, Shen BW, Stoddard BL. Thermodynamics of DNA target site recognition by homing endonucleases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:7209–7221. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Olsson TSG, Williams MA, Pitt WR, Ladbury JE. The thermodynamics of protein-ligand interaction and solvation: insights for ligand design. J. Mol. Biol. 2008;384:1002–1017. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.09.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kline PC, Schramm VL. Purine nucleoside phosphorylase. Inosine hydrolysis, tight binding of the hypoxanthine intermediate and third-the-sites reactivity. Biochemistry. 1992;31:5964–5973. doi: 10.1021/bi00141a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saen-Oon S, Ghanem M, Schramm VL, Schwartz SD. Remote mutations and active site dynamics correlate with catalytic properties of purine nucleoside phosphorylase. Biophys. J. 2008;94:4078–4088. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.121913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pugmire MJ, Ealick SE. Structural analyses reveal two distinct families of nucleoside phosphorylases. Biochem. J. 2002;361:1–25. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3610001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Todorova NA, Schwarz FP. Effect of the phosphate substrate on drug-inhibitor binding to human purine nucleoside phosphorylase. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2008;480:122–131. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2008.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hyre DE, Le Trong I, Freitag S, Stenkamp RE. Ser45 plays an important role in managing both the equilibrium and transition state energetics of the streptavidin-biotin system. Protein Sci. 2000;9:878–885. doi: 10.1110/ps.9.5.878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wielgus-Kutrowska B, Frank J, Holy A, Koellner G, Bzowska A. Interactions of trimeric purine nucleoside phosphorylase with ground state analogues-calorimetric and fluorimetric studies. Nucleosides, Nucleotides and Nucleic Acids. 2003;22:1695–1698. doi: 10.1081/NCN-120023116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang F, Miles RW, Kicska G, Nieves E, Schramm VL, Angeletti RH. Immucillin-H binding to purine nucleoside phosphorylase reduces dynamic solvent exchange. Protein Sci. 2000;9:1660–1668. doi: 10.1110/ps.9.9.1660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carbonell T, Freire E. Binding thermodynamics of statins to HMG-CoA reductase. Biochemistry. 2005;44:11741–11748. doi: 10.1021/bi050905v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sarver RW, Bills E, Bolton G, Bratton LD, Caspers NL, Dunbar JB, Harris MS, Hutchings RH, Kennedy RM, Larsen SD, Pavlovsky A, Pfefferkorn JA, Bainbridge G. Thermodynamic and structure guided design of statin based inhibitors of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase. J. Med. Chem. 2008;51:3804–3813. doi: 10.1021/jm7015057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Velazquez-Campoy A, Kiso Y, Freire E. The binding energetics of first-and second-generation HIV-1 protease inhibitors: implications for drug design. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2001;390:169–175. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2001.2333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schramm VL. Enzymatic transition states: thermodynamics, dynamics and analogue design. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2005;433:13–26. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2004.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lewandowicz A, Tyler PC, Evans G, Furneaux RH, Schramm VL. Achieving the ultimate physiological goal in transition state analogue inhibitors for purine nucleoside phosphorylase. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:31465–31468. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C300259200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rinaldo-Matthis A, Murkin AS, Ramagopal UA, Clinch K, Mee SPH, Evans GB, Tyler PC, Furneaux RH, Almo SC, Schramm VL. L-enantiomers of transition state analogue inhibitors bound to human purine nucleoside phosphorylase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:842–844. doi: 10.1021/ja710733g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ringia Taylor EA, Tyler PC, Evans GB, Furneaux RH, Murkin AS, Schramm VL. Transition state analogue discrimination by related purine nucleoside phosphorylases. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:7126–7127. doi: 10.1021/ja061403n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]