Abstract

α-Fetoprotein (AFP) transcription is activated early in hepatogenesis, but is dramatically repressed within several weeks after birth. AFP regulation is governed by multiple elements including three enhancers termed EI, EII, and EIII. All three AFP enhancers continue to be active in the adult liver, where EI and EII exhibit high levels of activity in pericentral hepatocytes with a gradual reduction in activity in a pericentral-periportal direction. In contrast to these two enhancers, EIII activity is highly restricted to a layer of cells surrounding the central veins. To test models that could account for position-dependent EIII activity in the adult liver, we have analyzed transgenes in which AFP enhancers EII and EIII were linked together. Our results indicate that the activity of EIII is dominant over that of EII, indicating that EIII is a potent negative regulatory element in all hepatocytes except those encircling the central veins. We have localized this negative activity to a 340-bp fragment. This suggests that enhancer III may be involved in postnatal AFP repression.

The α-fetoprotein (AFP) gene, which encodes the major serum protein in the developing mammalian fetus, is transcribed in the yolk sac visceral endoderm, fetal liver, and, to a much lesser extent, in the fetal gut and kidney (1). AFP activation during hepatogenesis occurs as primordial hepatocytes migrate out from the developing foregut (2). The AFP gene continues to be expressed abundantly in hepatocytes during development, but is dramatically repressed postnatally (3); in the liver, this represents a nearly 10,000-fold reduction in transcription (3). The AFP gene is normally expressed at extremely low levels in the adult liver, but can be reactivated during periods of renewed cell growth such as during liver regeneration and in hepatocellular carcinomas (4).

Perinatal AFP repression does not occur uniformly in all hepatocytes. Rather, reduced AFP mRNA levels are first seen in hepatocytes that reside in the perivenous regions of the liver, i.e., those cells surrounding the portal triads. AFP repression continues in a gradient-like fashion in a perivenous to pericentral direction (5, 6). Thus, the last cells to express AFP before complete shut-off reside in a single layer of hepatocytes surrounding the central veins. In addition to AFP repression, other transcriptional changes occur in the perinatal liver. In particular, the mRNAs for numerous liver enzymes become zonally expressed, i.e., synthesized exclusively in pericentral or perivenous hepatocytes (reviewed in ref. 7). For example, glutamine synthetase and ornithine aminotransferase are expressed exclusively in a narrow band of cells surrounding the central veins (8–10). Other enzymes, such as carbamoylphosphate synthetase and ornithine transcarbamylase, are expressed in a broad band of hepatocytes encircling the portal triads (10, 11). These periportal and pericentral regions of expression are nonoverlapping. The basis for this position-dependent regulation is not known, but a mathematical model whereby liver-enriched transcription factors could account for this type of gene control has been proposed (12).

AFP regulation is governed by five distinct regulatory regions: a 250-bp tissue-specific promoter, a 600-bp repressor element directly upstream of the promoter that is required for complete postnatal AFP repression, and three enhancers (reviewed in ref. 13). These three enhancers, called enhancer I (EI), EII, and EIII, are located 2.5, 5.0, and 6.5 kb, respectively, upstream of the AFP promoter (14). The activity of each enhancer has been localized to a 200- to 300-bp element called a minimal enhancer region (MER) (15). Transgenic studies showed that the three AFP enhancers could individually activate the AFP promoter in the yolk sac, fetal liver, and fetal gut, although they had slightly different activities in these three tissues (16). Each enhancer also activated the heterologous human β-globin (βgl) promoter in the three tissues where AFP is normally expressed (17). These transgenes continued to be active in the adult liver and gut, as expected, because they did not contain the repressor region (17). Interestingly, transgene expression was positionally regulated in the adult liver of these mice. EI and EII were most active in pericentral hepatocytes with a gradual reduction in enhancer activity toward the portal triad. In contrast, EIII had a more striking pattern of pericentral activity that was highly restricted to a single layer of cells surrounding the central veins (17). These studies also showed that EIII, but not EI or EII, was active in the brain, a tissue where AFP is not synthesized.

Two models could account for the highly restricted EIII activity in the adult liver: all hepatocytes except those encircling the central vein may lack positive regulators, or all but the pericentral hepatocytes may contain negative regulators. To distinguish between these two models, we have analyzed transgenes in which AFP enhancers EII and EIII are linked together. Our results demonstrate that the activity of EIII is dominant over that of EII in the adult liver, indicating that negative mechanisms must repress EIII activity in all hepatocytes except those surrounding the central veins. These data suggest that EIII may be involved in postnatal AFP repression in the liver.

Materials and Methods

Plasmids and Preparation of Transgenic Mice.

Transgenes used in this study are shown in Fig. 2B. The AFP plasmids βgl-Dd, EII-βgl-Dd, and EIII-βgl-Dd were described previously (17). To generate EIII-EII-βgl-Dd, a 2.3-kb BamHI–EcoRI fragment containing EIII (14) was introduced into pSP72 (Promega). A 7.5-kb fragment containing EII-βgl-Dd was inserted downstream of EIII in pSP72 such that both enhancers were in the same orientation. To generate MERIII-βgl-Dd, a 340-bp HincII fragment containing MERIII (15) was inserted into the SalI site of a modified pUC9 plasmid, excised as a 340-bp BamHI–BglII fragment, and inserted into BglII-linearized βgl-Dd to generate MERIII-βgl-Dd. The 2.3-kb EIII fragment of EIII-EII-βgl-Dd was replaced with a 340-bp MERIII fragment to generate MERIII-EII-βgl-Dd. Plasmids were purified by 2× CsCl ultracentrifugation.

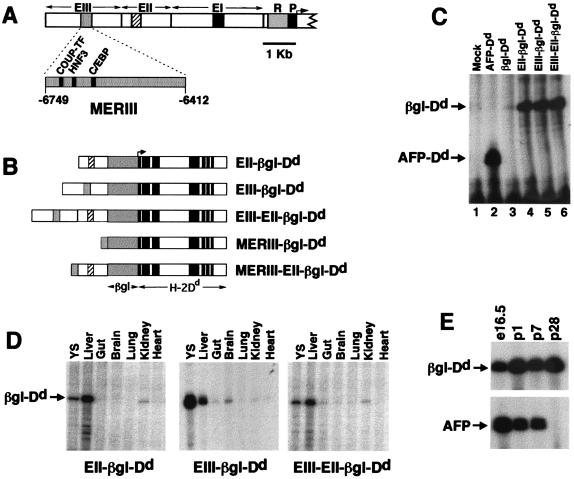

Figure 2.

(A) Map of the AFP regulatory region showing the promoter (P), repressor (R), and enhancers (EI, EII, and EIII). MERI, MERII, and MERIII are shown as black, crosshatched, and stippled boxes, respectively. Expanded view of MERIII shows the relative location of the COUP-TF, HNF3, and C/EBP binding sites. (B) Transgenes used in this study. AFP enhancer regions (EIII, EII, and MERIII) were linked to the human β-globin/H-2Dd reporter gene (βgl-Dd). Transcription initiates from the β-globin promoter and extends through the entire 8-exon Dd gene. (C) Activities of AFP enhancers EII and EIII are equivalent and nonadditive in HepG2 cells. Cells were transfected with the constructs described at the top of the figure. After 48 h, cells were harvested and RNA was prepared. RNase protection assays were performed with a radiolabeled βgl-Dd probe. Transcripts from βgl-Dd constructs protect a 113-nt fragment; transcripts from a control AFP-Dd construct protect a 49-nt fragment. Mock, no DNA. (D) The pattern of transgene activities is similar to AFP in embryonic day 16.5 fetal tissues. RNA was prepared from the tissues described in the figure (YS, yolk sac) and analyzed by RNase protection. Mice containing EII-βgl-Dd, EIII-βgl-Dd, or EIII-EII-βgl-Dd exhibit high levels of transgene mRNA in the liver and yolk sac and low levels in the gut and kidney, similar to the pattern of AFP expression at this time point. The EIII-βgl-Dd transgene also has moderate activity in the fetal brain. (E) EIII-EII-βgl-Dd transgenes continue to be expressed postnatally in the liver. RNA was prepared from the livers of EIII-EII-βgl-Dd mice at embryonic day 16.5 and postnatal days 1, 7, and 28 and used in RNase protection assays with βgl-Dd and AFP probes. The AFP gene is postnatally repressed by 4 wk after birth; transgene mRNA levels do not decline during this period.

For microinjections, hybrid genes were excised from vector sequences with EcoRI and purified by agarose gel electrophoresis and CsCl ultracentrifugation (18). Purified DNA was diluted to a concentration of 5 ng/μl and injected into F2 hybrid embryos from C57BL/6 × C3H parents. All procedures were performed at the University of Kentucky Transgenic Mouse Facility. Two weeks after birth, progeny were screened by Southern blot by using a 1.5-kb human β-globin promoter probe.

Cell Culture and Transfection.

HepG2 cells were maintained and transfected by the calcium phosphate procedure as described (19). Forty-eight hours after transfection, cellular RNA was prepared by using Trizol (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Analysis of RNA.

RNase protection assays were performed by using 50 μg of RNA as described (18). Yeast tRNA (Life Technologies) was added to bring the total RNA to 50 μg when necessary. Plasmids containing either the AFP or βgl-Dd RNase probes were linearized with XhoI and transcribed with T7 RNA polymerase to generate radiolabeled probes. The glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) probe was purchased from Ambion (Austin, TX). Radioactive bands were visualized by autoradiography with Kodak X-Omat AR film. Unless otherwise indicated, exposures were for 14–18 h. Quantitative analysis of RNA bands was performed by using phosphorimage analysis.

Immunohistochemistry.

For adult liver analysis, 2- to 3-mo-old mice were killed and liver blocks were quick-frozen in OTC compound (Miles, IN). For fetal liver analysis, day 12.5 mouse embryos were embedded in OTC compound and frozen on dry ice. Ten-micrometer sections were prepared, stained with a FITC-conjugated mouse anti-Dd monoclonal antibody (cat. no. 06134D; PharMingen), and photographed as described (20). Alternate sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin, dried, mounted, and photographed.

Results

When individually linked to the heterologous β-globin promoter/H-2Dd (βgl-Dd) reporter gene (see Fig. 2B), each of the three AFP enhancers exhibited different position-dependent activities in the adult liver (17). EII and EI were active in all hepatocytes, but showed a gradual reduction in activity across the liver acinus in a pericentral-periportal direction. In contrast, EIII activity in the adult liver was highly restricted to a layer of hepatocytes directly surrounding central veins. These patterns of expression in the liver were due to the action of the linked enhancers, because enhancerless βgl-Dd transgenes were inactive in all fetal and adult tissues.

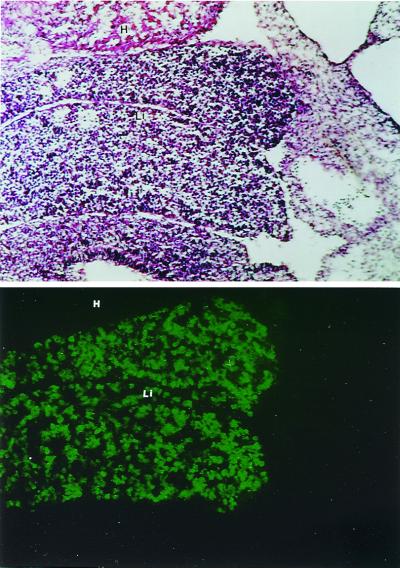

The position-dependent activity of EIII in the adult liver suggests that this element is regulated similarly to glutamine synthetase and ornithine aminotransferase because both of these genes also exhibit highly restricted pericentral expression in the adult liver. These two genes are expressed in all hepatocytes in the developing liver, with pericentral activity established perinatally (9, 10). To see whether this was also the case for EIII-βgl-Dd transgenes, we sectioned and stained day 12.5 embryos with a FITC-conjugated anti-Dd antibody (Fig. 1). Hepatocytes, which comprise roughly 40% of the cells in the fetal liver at day 12.5 (21), express high levels of transgenic Dd proteins. Hematopoietic cells, which represent roughly 60% of the cells in day 12.5 livers, do not express Dd, indicating that the transgene is not active in these cells. Thus, EIII is active in all hepatocytes in the developing liver similarly to other genes that exhibit pericentral activity in the adult liver.

Figure 1.

EIII-βgl-Dd transgenes are expressed in all hepatocytes in embryonic day 12.5 livers. Immunohistochemical staining with FITC-conjugated anti-Dd antibodies was used to localize transgene expression in sections of whole embryos removed 12.5 days after fertilization (Bottom). Staining of an adjacent section with hematoxylin and eosin reveal the two lobes of the liver at this early developmental time point (Top). All hepatocytes are stained by the anti-Dd antibody; regions of the liver where there is no staining represent hematopoietic cells. The Dd staining is restricted to the liver. H, heart; L, liver.

EIII changes from a potent enhancer in all hepatocytes in the fetal liver to a highly position-dependent enhancer in the adult liver. To test models that could account for this dramatic change in EIII activity, EIII and EII were fused in tandem to the chimeric βgl-Dd reporter construct to generate EIII-EII-βgl-Dd (Fig. 2B). In one model, EIII activity is determined solely by the positive regulation in pericentral hepatocytes. The lack of EIII activity in nonpericentral hepatocytes would simply be because of the absence of positive regulation in these cells. This model predicts that EIII would not influence EII activity, and that EIII-EII-βgl-Dd transgenes would exhibit an EII-like pattern of expression in the adult liver. A second model is that negative regulation actively represses EIII in all hepatocytes except those encircling the central veins. This predicts that EIII may act in a dominant manner to block the activity of a linked regulatory element in nonpericentral hepatocytes. A highly restricted, EIII-like pattern of activity of EIII-EII-βgl-Dd transgenes in the adult liver would support this model. Thus, the positional activity of this dual enhancer transgene in the adult liver should distinguish between these two models.

Constructs used to monitor enhancer activity were initially tested by transient transfection in AFP-permissive human hepatoma HepG2 cells (Fig. 2C). The enhancerless βgl-Dd construct showed a low but detectable level of activity (βgl-Dd arrow); as expected, the βgl promoter is much less active that the AFP promoter (AFP-Dd arrow) in HepG2 cells. Constructs with βgl-Dd linked to EII or EIII individually, or EII and EIII together, had substantially higher activity than the parental βgl-Dd vector. Transcripts from these three enhancer-containing plasmids were equivalent to each other, consistent with previous studies that showed that the activities of the mouse AFP enhancers were not additive in HepG2 cells (14).

Five transgenic lines were generated with the EIII-EII-βgl-Dd construct. Transgene expression in these mice was compared with mice harboring the transgenes EII-βgl-Dd or EIII-βgl-Dd. To monitor transgene expression in fetal mice, total RNA from day 16.5 embryonic tissues was analyzed by RNase protection assays (Fig. 2D). In mice from all three transgenic lines, βgl-Dd transcripts were found at moderate to high levels in the yolk sac and fetal liver and at low levels in the fetal gut and kidney. The endogenous AFP gene showed the same pattern of expression (data not shown; ref. 16). The EIII-βgl-Dd transgenes were expressed at moderate levels in the fetal brain, consistent with our previous studies which showed that this transgene is active in the adult brain (17, 22).

The endogenous AFP gene undergoes a dramatic shut-off after birth that results in low but detectable AFP levels by postnatal day 28. Transgenes with EII or EIII linked to βgl-Dd continued to be active postnatally in the liver (17). To ensure that the EIII-EII-βgl-Dd transgene continued to be expressed in the adult liver, liver RNA collected at several postnatal time points was analyzed by RNase protection (Fig. 2E). In contrast to the postnatal endogenous AFP repression that is complete by 4 wk after birth, EIII-EII-βgl-Dd mRNA levels remained unchanged during this postnatal period.

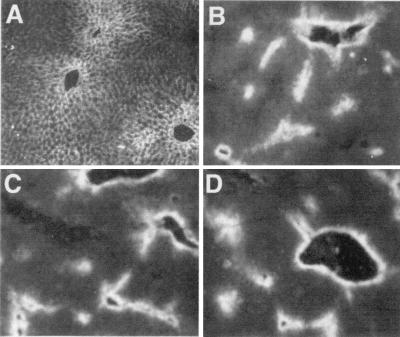

To analyze position-dependent transgene activity, liver sections from adult mice containing enhancer-linked βgl-Dd constructs were stained with anti-Dd antibodies (Fig. 3). The Dd expression in two of the EIII-EII-βgl-Dd lines (Fig. 3 C and D) was highly restricted to pericentral hepatocytes; this staining was also seen in the other three lines with this transgene (data not shown). This activity is identical to the pericentral staining seen with mice containing EIII-βgl-Dd (Fig. 3B) and is quite distinct from the staining seen in mice with EII-βgl-Dd (Fig. 3A). This demonstrates that enhancer III activity is dominant over that of enhancer II and supports the notion that restricted EIII activity in the adult liver is because of negative regulation.

Figure 3.

The activity of EIII and MERIII is dominant over that of EII in the adult liver. Livers removed from transgenic mice 4 wk after birth were frozen, sectioned, stained with the FITC-anti-Dd antibody, and visualized with fluorescence microscopy. Staining of an EII-βgl-Dd liver reveals a broadly diffuse pattern of transgene activity with a gradual pericentral-periportal gradient (A). In contrast, staining of an EIII-βgl-Dd liver is highly restricted to one to two layers of cells surrounding the central veins (B). Transgene activity in two different EIII-EII-βgl-Dd lines (C and D) is restricted to pericentral regions similarly to transgenes with EIII alone.

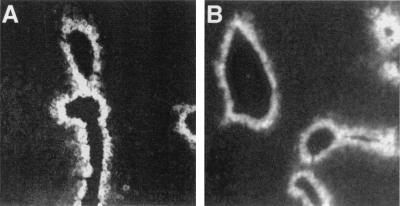

Deletion analysis using HepG2 cells localized the entire enhancer activity of the 2.3-kb EIII to a 340-bp fragment called MERIII (minimal enhancer region III; ref. 15). To test whether MERIII exhibited the same activity as the entire 2.3-kb EIII in the liver, we linked the 340-bp MERIII to βgl-Dd and EII-βgl-Dd to generate MERIII-βgl-Dd and MERIII-EII-βgl-Dd, respectively. Immunohistochemical analysis of Dd expression in the adult liver of MERIII-βgl-Dd mice verified that MERIII had the same pericentral activity as the entire EIII (Fig. 4A). RNase protection assays and immunohistochemical staining indicated the MERIII was also active in the yolk sac, fetal liver, and fetal gut and fetal brain, similar to EIII (data not shown). This demonstrates that the cis-acting sites required for pericentral activity reside within this 340-bp MERIII fragment. In addition, MERIII could restrict EII activity to the same zonal region as the entire EIII fragment (Fig. 4B). Thus, the 340-bp MERIII fragment contains sufficient information for the positive and negative activity of this enhancer.

Figure 4.

The 340-bp MERIII is sufficient for the pericentral activity of EIII in the adult liver. Livers were removed from 4-wk-old mice and stained with the anti-Dd antibody as described in Fig. 3. MERIII-βgl-Dd (A) and MERIII-EII-βgl-Dd (B), which contain the 340-bp MERIII element linked to βgl-Dd in the absence or presence of EII, respectively, exhibit pericentral staining that is restricted to one to two layers of cells.

We have shown here (Fig. 2C) and previously (17) that EIII is active in the fetal and adult brain. The endogenous AFP gene is not expressed in this tissue, suggesting that mechanisms must exist that block AFP promoter activation by EIII in this tissue. To investigate this, we monitored transgene activity in the brains of EII-βgl-Dd, EIII-βgl-Dd, and EIII-EII-βgl-Dd mice (Fig. 5). Brain RNA from 4-wk-old mice was analyzed by RNase protection assays with probes for βgl-Dd or GAPDH, which was used to control for variations in mRNA loading (Fig. 5A). Mice with EII-regulated transgenes had little if any detectable βgl-Dd transcripts in the brain, whereas mice with EIII-βgl-Dd exhibited readily detectable levels of transgene expression. Mice with the dual enhancer transgene had low but detectable levels of βgl-Dd mRNA. Phosphorimage analysis indicated that transgene mRNA levels in EIII-EII-βgl-Dd mice were roughly 10% of the levels found in EIII-βgl-Dd mice (Fig. 5B). This demonstrates that EII can restrict EIII activity in the brain and suggests a possible mechanism to explain the lack of endogenous AFP expression despite EIII activity in this tissue.

Figure 5.

AFP enhancer EII limits EIII activity in the adult brain. (A) Total brain RNA was prepared from mice containing EII-βgl-Dd (EII, lanes 1–4), EIII-βgl-Dd (EIII, lanes 5–8), or EIII-EII-βgl-Dd (EIII-EII, lanes 9–14) and used in RNase protection assays. The GAPDH levels were monitored to ensure that equal amounts of RNA were used for each sample. (B) Phosphorimage analysis to quantitate βgl-Dd mRNA levels in the RNase protection data shown in A. Transgene mRNA was normalized to GAPDH for each mouse. The data are expressed as percentage of transgene expression compared with GAPDH for each individual mouse.

Discussion

Genetic studies in Drosophila melanogaster have revealed that negative regulatory elements have important roles in the developmental and position-dependent control of transcription (reviewed in ref. 23). Fewer examples of position-dependent transcription because of negative regulation exist in mammals, but such regulation does occur. For example, position-dependent Hoxd-11 and Hoxb1 gene activation involves the interplay of positive and negative elements (24, 25). The highly restricted position-dependent activity of EIII in the adult liver, in contrast to EIII activity in all hepatocytes in the fetal liver, led us to ask whether negative regulation led to this developmental change in EIII activity. The ability of EIII to block EII activity when these two enhancers were linked together indicates that pericentral EIII activity in the adult liver is due to negative regulation in all hepatocytes except those encircling central veins.

The ability of MERIII to confer pericentral regulation of the β-globin promoter, in the presence or absence of EII, indicates that this 340-bp region contains all of the cis-acting elements that are required for this pattern of expression. Therefore, factors that interact with motifs in this region must be involved with positional control. This region contains binding sites for several factors that govern transcription in the liver (Fig. 2A). The 5′ end of MERIII contains a binding site for hepatocyte nuclear factor 3 (HNF3; ref. 26); this site also binds HNF-6 (D.K.P. and B.T.S., unpublished observations). Forty-five base pairs 3′ of this HNF3 site is a C/EBP binding site (26). Upstream of the HNF-3 site is a chicken ovalbumin upstream promoter-transcription factor (COUP-TF) binding site (27). Deletion studies have shown that all three of these sites contribute to MERIII activity in HepG2 cells (27). Of these factors, COUP-TF and HNF-3 are particularly interesting because both of these, although generally associated with positive regulation, have been shown to be repressors in some situations (28–30). The 3′ end of MERIII also contributes to enhancer activity (15, 26), although the factors that interact with this region have not been identified. Further dissection of this 340-bp enhancer will be required to elucidate the transcriptional basis for pericentral activity.

It is not clear how EIII restricts EII activity in the adult liver. EIII is distal to EII in the EIII-EII-βgl-Dd transgene, so it is unlikely that EIII acts as an insulator between EII and the promoter because insulator action is position-dependent (31–33). MERIII is nearly 1500 and 4200 bp upstream of MERII and the β-globin promoter, respectively, in the dual enhancer transgene, so the repressive effect of EIII must act over relatively large distances. One possible model to account for action over this distance is that factors bound to EIII can alter nucleosome positioning. In this regard, it is interesting that HNF3 contributes to MERIII activity because studies by Zaret and colleagues (34) have shown that HNF3 can affect nucleosome positioning on the albumin enhancer. In this way HNF-3 binding to EIII could influence transcriptional activity over considerable distances.

Previous transgenic studies suggested that the AFP enhancers were not involved in postnatal AFP repression (35). However, these studies measured enhancer activity by Northern analysis and were therefore unable to detect position-dependent changes in activity. The negative action of EIII in the adult liver raises the possibility that this element could, in fact, contribute to postnatal AFP repression. AFP silencing at birth occurs in a periportal-pericentral direction, with periportal hepatocytes being the first to repress AFP transcription and pericentral hepatocytes being the last cells to express AFP before the gene is entirely repressed (6). EIII-βgl-Dd transgenes are expressed in all hepatocytes in embryonic day 12.5 livers and exhibit a temporal pattern of periportal to pericentral repression that is similar to AFP (D.K.P. and B.T.S., unpublished observations), with the exception that EIII-regulated transgenes remain active in pericentral hepatocytes. These similar patterns of perinatal AFP and EIII repression indicate that the negative action of EIII could contribute to postnatal AFP repression in most hepatocytes, with additional mechanisms required to repress AFP in the remaining pericentral hepatocytes. This model is consistent with data presented by Tilghman and coworkers (36) that focused on the AFP repressor region. This in situ analysis revealed that transgenes lacking a repressor were not expressed throughout the adult liver, but rather were expressed only in pericentral hepatocytes with a pattern identical to that shown here for EIII. This led to the proposal that the repressor is responsible for AFP repression in pericentral hepatocytes but other elements must be responsible for AFP shut-off in other hepatocytes (36). The negative action of EIII in the adult liver suggests that this region could account for AFP repression in these cells. Taken together, one could envision a model whereby two elements, the AFP repressor and EIII, act coordinately to regulate postnatal AFP repression. However, other studies in our lab indicate that the AFP promoter is regulated by Afr1, a locus unlinked to AFP that controls postnatal AFP levels in the adult liver (20). Thus, AFP shut-off in the adult liver is a complex process that appears to require multiple elements. In addition, the data presented here suggest that the mechanisms governing position-dependent transcription of genes in the adult liver and postnatal AFP repression may be similar.

Acknowledgments

We thank Michelle Glenn, Leila Ghabrial, and Nedda Hughes for expert technical assistance, and Martha Peterson for critically reading the manuscript. This research is supported by Public Health Service Grants GM45253 and DK51600.

Abbreviations

- AFP

α-fetoprotein

- MER

minimal enhancer region

- βgl

β-globin

- GAPDH

glyeraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- HNF

hepatocyte nuclear factor

Footnotes

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Article published online before print: Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 10.1073/pnas.200290397.

Article and publication date are at www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.200290397

References

- 1.Tilghman S M. Oxford Surv Eukaryotic Genes. 1985;2:160–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gauldi R, Bossard P, Zheng M, Hamada Y, Coleman J R, Zaret K S. Genes Dev. 1996;10:1670–1682. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.13.1670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Belayew A, Tilghman S M. Mol Cell Biol. 1982;2:1427–1435. doi: 10.1128/mcb.2.11.1427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abelev G I. Adv Cancer Res. 1971;14:295–358. doi: 10.1016/s0065-230x(08)60523-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Poliard A M, Bernuau D, Tournier I, Legres L, Schoevaert D, Feldmann G, Sala-Trepat J M. J Cell Biol. 1986;103:777–786. doi: 10.1083/jcb.103.3.777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moorman A F M, DeBoer P A J, Evans D, Charles R, Lamers W H. Histochem J. 1990;22:653–660. doi: 10.1007/BF01047449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gumucio J J. Hepatology. 1989;9:154–160. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840090124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bennett A L, Paulson K E, Miller R E, Darnell J E. J Cell Biol. 1987;105:1073–1085. doi: 10.1083/jcb.105.3.1073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuo F C, Hwu W L, Valle D, Darnell J E. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:9468–9472. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.21.9468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moorman A F M, DeBoer P A J, Das A T, Labruyere W T, Charles R, Lamers W H. Histochem J. 1990;22:457–468. doi: 10.1007/BF01007229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Christoffels V M, van den Hoff M J B, Lamers M C, van Roon M A, deBoer P A J, Moorman A F M, Lamers W H. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:31243–31250. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.49.31243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Christoffels V M, Sassi H, Ruijter J M, Moorman A F M, Grange T, Lamers W H. Hepatology. 1999;29:1180–1192. doi: 10.1002/hep.510290413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Spear B T. Semin Cancer Biol. 1999;9:109–116. doi: 10.1006/scbi.1998.0087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Godbout R, Ingram R S, Tilghman S M. Mol Cell Biol. 1986;6:477–487. doi: 10.1128/mcb.6.2.477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Godbout R, Ingram R S, Tilghman S M. Mol Cell Biol. 1988;8:1169–1178. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.3.1169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hammer R E, Krumlauf R, Camper S A, Brinster R L, Tilghman S M. Science. 1987;235:53–58. doi: 10.1126/science.2432657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ramesh T, Ellis A W, Spear B T. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:4947–4955. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.9.4947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spear B T. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:6497–6505. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.10.6497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spear B T, Tilghman S M. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:5047–5054. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.10.5047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peyton D K, Huang M-C, Giglia M A, Hughes N K, Spear B T. Genomics. 2000;63:173–180. doi: 10.1006/geno.1999.6073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Paul J, Conkie D, Freshney R I. Cell Tissue Kinet. 1969;2:283–294. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ramesh T, Spear B T. Transgenics. 1999;2:391–401. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cai H N, Arnosti D N, Levine M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:9309–9314. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.18.9309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gerard M, Duboule D, Zakany J. EMBO J. 1993;12:3539–3550. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06028.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Studer M, Popperl H, Marshall H, Kuroiwa A, Krumlauf R. Science. 1994;265:1728–1732. doi: 10.1126/science.7916164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Groupp E R, Crawford N, Locker J. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:22178–22187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thomassin H, Bois-Joyeux B, Delille R, Ikonomova R, Danan J-L. DNA Cell Biol. 1996;15:1063–1074. doi: 10.1089/dna.1996.15.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Achatz G, Holzl B, Speckmayer R, Hauser C, Sandhofer F, Paulwever B. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:4914–4932. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.9.4914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gregori C, Kahn A, Pichard A L. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:1242–1246. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.7.1242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kimura A, Nishiyori A, Murakami T, Tsukamoto T, Hata S, Osumi T, Okamura R, Mori M, Takaguchi M. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:11125–11133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chung J H, Whiteley M, Felsenfeld G. Cell. 1993;74:505–514. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)80052-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Geyer P K, Corces V G. Genes Dev. 1992;6:1865–1873. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.10.1865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Holdridge C, Dorsett D. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:1894–1900. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.4.1894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shim E Y, Woodcock C, Zaret K S. Genes Dev. 1998;12:5–10. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.1.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Camper S A, Tilghman S M. Genes Dev. 1989;3:537–546. doi: 10.1101/gad.3.4.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Emerson J A, Vacher J, Cirillo L A, Tilghman S M, Tyner A L. Dev Dyn. 1992;195:55–66. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001950106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]