Abstract

Each diastereomer of 10-thiophenyl- and 10-benzenesulfonyl-dihydroartemisinin was synthesized from artemisinin in three steps, and screened against chloroquine-resistance and chloroquine-sensitive Plasmodium falciparum. Three of the four tested compounds were found to be effective. Especially, 10β-benzenesulfonyl-dihydroartemisinin showed stronger antimalarial activity than artemisinin.

Keywords: Plasmodium falciparum, antimalarial activity, artemisinin, dihydroartemisinin, synthesis, natural product

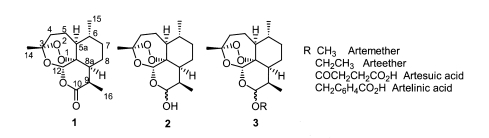

The natural sesquiterpene endoperoxide artemisinin (Fig. 1-1), which was isolated from Artemisia annua L. (Klayman, 1985), has become a potential lead compound in the development of an antimalarial (Luo and Shen, 1987; Jung, 1994; Haynes and Vonwiller, 1997; Vroman et al., 1999) and recently anticancer agents (Beekman et al., 1997; Jung et al., 2003; Posner et al., 2003). The semi-synthetic, acetal-type, artemisinin derivatives (Fig. 1-3), ether and ester derivatives of trioxane lactol dihydroartemisinin (Fig. 1-2), were developed for their higher antimalarial efficacy and are now widely used to treat malarial patients (Fig. 1) (Brossi et al., 1988).

Fig. 1.

Structure of artemisinin and acetal-type artemisinin derivatives.

Although these acetal artemisinin derivatives showing potent antimalarial activity in vitro, the acetal functional group at the C-10 position is responsible for chemical instability (Jung and Lee, 1998), and toxicity (Gordi and Lepist, 2004). Therefore, to improve bioavailability, it is important to discover novel artemisinin derivatives suitable to chemo-antimalarial therapy. In 1995, Venugopalan et al. reported a series of thioacetal type artemisinin derivatives, some of which have potent antimalarial activity in vivo.

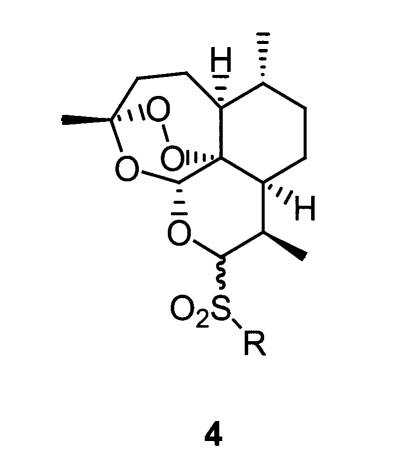

In 1998, Posner et al. also reported that sulfide and sulfone endoperoxide from R-(+)-limonene (Bachi et al., 1998) and sulfone trioxanes (Posner et al., 1998; Posner et al., 2000) have similar or less activity to natural artemisinin. However, because there is no report on C-10 sulfonyl artemisinin derivatives (Fig. 2), we decided to investigate and report the synthesis and antimalarial activity of such derivatives.

Fig. 2.

Structure of thioacetal artemisinin derivatives.

TESTED COMPOUNDS

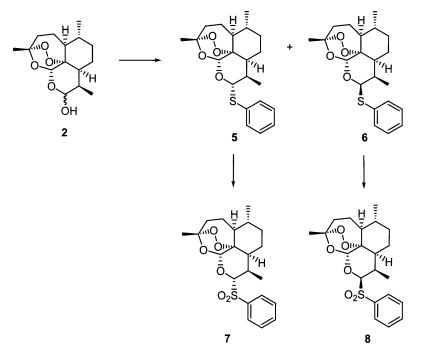

As seen in Fig. 3, separable diastereomeric mixtures of 10α- (Fig. 3-6) and 10β-thiophenyl-dihydroartemisinins (Fig. 3-6) were prepared by reacting known dihydroartemisinin (Fig. 1-2) (Lin et al., 1987) with thiophenol (2eq) under the catalysis of BF3Et2O (1eq) at room temperature for 10 minutes (Venugopalan et al., 1995; Oh et al., 2004a, 2004b). The thioacetal products (Fig. 3-6) were transformed to produce 10α- (Fig. 3-7) and 10β-benzenesulfonyl-dihydroartemisinins (Fig. 3-8), respectively, in good yields, by performing oxidation with H2O2/urea complex (UHP), trifluoroacetic anhydride (TFAA) and NaHCO3 (Varma and Naicker, 1999; Caron et al., 2000).

Fig. 3.

Synthesis of thioacetal artemisinin derivatives.

Strains of Plasmodium falciparum

Two culture-adapted strains of P. falciparum were used: the chloroquine-sensitive strain FCR-8/West African, and chloroquine-resistant strain FCR-3/Gambia subline F-86 of P. falciparum obtained from ATCC (Nguyen-Dinh and Trager, 1980; Jensen and Trager, 1978). The medium used was RPMI medium containing hypoxanthine and supplemented with HEPES buffer, sodium bicarbonate, human A serum, glutamine, gentamicin, and uninfected human O erythrocytes.

In vitro measurement of parasite growth inhibition by drugs

The assays were conducted in vitro by a modification of the semiautomated microdilution technique of Desjardins et al. (1979) and Delhaes et al. (2002) based on radiolabeled [3H]hypoxanthine incorporation. Drug testing was carried out in 96-well, microtiter plates. Stock solutions of each compound were prediluted in complete culture medium (RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% pooled human A serum), and titrated in duplicate in serial twofold dilutions. The final concentrations ranged from 1.96-250 nmole L-1 for artemisinin derivatives and artemisinin, and 11.2-1435nmole L-1 for chloroquine. After the addition of a suspension of parasitized erythrocytes in complete culture medium (200µl per well, 0.7% initial parasitemia with a majority of ring stages, 1.8-2% haematocrit) and [H3]hypoxanthine (Amersham, UK, TRK74, 1µl per well), the test plates were incubated at 37℃ for 24 h in an atmosphere of 5% O2, 5% CO2, and 90% N2. Growth of the parasites was estimated from the incorporation of radiolabeled [H3]hypoxanthine into the parasites` nucleic acids, measured in a liquid scintillation spectrometer (Packard, USA). The 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) values refer to the molar concentrations of drug causing a 50% reduction in [H3]hypoxanthine incorporation, compared to drug-free control wells. IC50 values were estimated by linear regression analysis of log-dose-response curves.

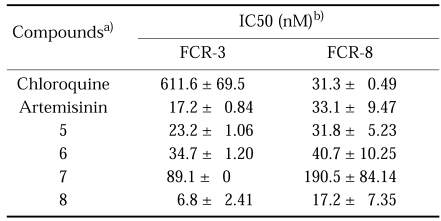

In the screening of the two standard molecules, chloroquine and artemisinin, against chloroquine-resistance (50005 = FCR-3) and -sensitive (50028 = FCR-8) parasites, we could confirm the biological property of each cell line and the inhibitory activity of each drug (Table 1). At first, two diastereomers, 10α-(Fig. 3-5) and 10β-thiophenyl-dihydroartemisinins (Fig. 3-6), had a similar inhibition activity with artemisinin. Interestingly, 10α- (Fig. 3-7) and 10β-benzenesulfonyl-dihydroartemisinins (Fig. 3-8) showed different inhibitory activity against each cell line according to the change of stereochemistry in the C-10 position of artemisinin. 10β-Diastereomer (Fig. 3-8) was ten times more active than 10α-diastereomer (Fig. 3-7). In particular, 10β-benzenesulfonyl-dihydroartemisinin (Fig. 3-8) was two times more active than artemisinin and ninety times more than chloroquine. This preliminary screening of each thiophenyl- and benzenesulfonyl-dihydroartemisinin derivative indicated that 10β-sulfonyl-dihydroartemisinin derivative can be a potentially promising antimalarial drug against chloroquine-resistance parasites.

Table 1.

Antimalarial activity of thiophenyl- and benzenesulfonyl-dihydroartemisinin against chloroquine-resistance (FCR-3) and -sensitive P. falciparum (FCR-8)

a)5 & 6, 10α- and 10β-thiophenyl-dihydroartemisinins; 7 & 8, 10α- and 10β-benzenesulfonyl-dihydroartemisinins.

b)IC50 represents the drug concentration producing 50% inhibition of the growth of P. falciparum in drug-free control wells. IC50 values were obtained from plots of the growth-inhibition data.

Footnotes

This study was supported by a grant from the Korea Science and Engineering Foundation [R05-2002-000-00808-0(2002)]

References

- 1.Bachi MD, Korshin EE, Ploypradith P, Cumming JN, Xie S, Shapiro TA, Posner GH. Synthesis and in vitro antimalarial activity of sulfone endoperoxides. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 1998;8:903–908. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(98)00141-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beekman AC, Barentsen AR, Woerdenbag HJ, Van Uden W, Pras N, Konings AW, el-Feraly FS, Galal AM, Wikstrom HV. Stereochemistry-dependent cytotoxicity of some artemisinin derivatives. J Nat Prod. 1997;60:325–330. doi: 10.1021/np9605495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brossi A, Venugopalan B, Dominguez Gerpe L, Yeh HJ, Flippen-Anderson JL, Buchs P, Luo XD, Milhous W, Peters W. Arteether, a new antimalarial drug: synthesis and antimalarial properties. J Med Chem. 1988;31:645–650. doi: 10.1021/jm00398a026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Caron S, Do NM, Sieser JE. A practical, efficient, and rapid method for the oxidation of electron deficient pyridines using trifluoroacetic anhydride and hydrogen peroxide-urea complex. Tetrahedron Lett. 2000;41:2299. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Delhaes L, Biot C, Berry L, Delcourt P, Maciejewski LA, Camus D, Brocard JS, Dive D. Synthesis of ferroquine enantiomers: First investigation of effects of metallocenic chirality upon antimalarial activity and cytotoxicity. Chembiochem. 2002;3:418–423. doi: 10.1002/1439-7633(20020503)3:5<418::AID-CBIC418>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Desjardins RE, Canfield CJ, Haynes JD, Chulay JD. Quantitative assessment of antimalarial activity in vitro by a semiautomated microdilution technique. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1979;16:710–718. doi: 10.1128/aac.16.6.710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gordi T, Lepist EI. Artemisinin derivatives: toxic for laboratory animals, safe for humans? Toxicol Lett. 2004;147:99–107. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2003.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haynes RK, Vonwiller SC. From Qinghao, marvelousherb of antiquity, to the antimalarial trioxane qinghaosu-and some remarkable new chemistry. Acc Chem Res. 1997;30:73–79. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jensen JB, Trager W. Plasmodium falciparum in culture: establishment of additional strains. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1978;27:743–746. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1978.27.743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jung M. Current developments in the chemistry of artemisinin and related compounds. Curr Med Chem. 1994;1:35–49. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jung M, Lee S. Stability of acetal and non acetal-type analogs of artemisinin in simulated stomach acid. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 1998;8:1003–1006. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(98)00160-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jung M, Lee S, Ham J, Lee K, Kim H, Kim SK. Antitumor activity of novel deoxoartemisinin monomers, dimers, and trimer. J Med Chem. 2003;46:987–994. doi: 10.1021/jm020119d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klayman DL. Qinghaosu (artemisinin): an antimalarial drug from China. Science. 1985;228:1049–1055. doi: 10.1126/science.3887571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lin AJ, Klayman DL, Milhous WK. Antimalarial activity of new water-soluble dihydroartemisinin derivatives. J Med Chem. 1987;30:2147–2150. doi: 10.1021/jm00394a037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Luo XD, Shen CC. The chemistry, pharmacology, and clinical applications of qinghaosu (artemisinin) and its derivatives. Med Res Rev. 1987;7:29–52. doi: 10.1002/med.2610070103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nguyen-Dinh P, Trager W. Plasmodium falciparum in vitro: determination of chloroquine sensitivity of three new strains by a modified 48-hour test. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1980;29:339–342. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1980.29.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oh S, Jeong IH, Ahn CM, Shin WS, Lee S. Synthesis and antiangiogenic activity of thioacetal artemisinin derivatives. Bioorg Med Chem. 2004a;12:3783–3790. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2004.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oh S, Jeong IH, Shin WS, Lee S. Synthesis and antiangiogenic activity of exo-olefinated deoxoartemisinin derivatives. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2004b;14:3683–3686. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2004.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Posner GH, O'Dowd H, Caferro T, Cumming JN, Ploypradith P, Xie S, Shapiro TA. Antimalarial sulfone trioxanes. Tetrahedron Lett. 1998;39:2273–2276. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Posner GH, Maxwell JP, O'Dowd H, Krasavin M, Xie S, Shapiro TA. Antimalarial sulfide, sulfone, and sulfonamide trioxanes. Bioorg Med Chem. 2000;8:1361–1370. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(00)00079-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Posner GH, Paik I-H, Sur S, McRiner AJ, Borstnik K, Xie S, Shapiro TA. Orally active, antimalarial, anticancer, artemisinin-derived trioxane dimers with high stability and efficacy. J Med Chem. 2003;46:1060–1065. doi: 10.1021/jm020461q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Varma RS, Naicker KP. The urea-hydrogen peroxide complex: Solid-state oxidative protocols for hydroxylated aldehydes and ketones (Dakin reaction), nitriles, sulfides, and nitrogen hetrocycles. Organic Lett. 1999;1:189–191. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Venugopalan B, Karnik PJ, Bapat CP, Chatterjee DK, Iyer N, Lepcha D. Antimalarial activity of new ethers and thioethers of dihydroartemisinin. Eur J Med Chem. 1995;30:697–706. doi: 10.1021/jm00011a012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vroman JA, Alvim-Gaston M, Avery MA. Current progress in the chemistry, medicinal chemistry and drug design of artemisinin based antimalarials. Curr Pharm Des. 1999;5:101–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]