Abstract

AIM: To investigate the therapeutic efficacy of short-term, multiple daily dosing of intravenous interferon (IFN) in patients with hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg)-positive chronic hepatitis B.

METHODS: IFN-β was intravenously administered at a total dose of 102 million international units (MIU) over a period of 28 d in 26 patients positive for HBeAg and HBV-DNA. IFN-beta was administered at doses of 2 MIU and 1 MIU on d 1, 3 MIU twice daily from d 2 to d 7, and 1 MIU thrice daily from d 8 to d 28. Patients were followed up for 24 wk after the end of treatment.

RESULTS: Six months after the end of the treatment, loss of HBV-DNA occurred in 13 (50.0%) of the 26 patients, loss of HBeAg in 9 (34.6%), development of anti-HBe in 10 (38.5%), HBeAg seroconversion in 8 (30.8%), and normalization of alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels in 11 (42.0%).

CONCLUSION: This 4-wk long IFN-β therapy, which was much shorter than conventional therapy lasting 12 wk or even more than 1 year, produced therapeutic effects similar to those achieved by IFN-α or pegylated-IFN-α (peg-IFN). Fewer adverse effects, greater efficacy, and a shorter treatment period led to an improvement in patients’ quality of life. IFN-β is administered intravenously, whereas IFN-α is administered intramuscularly or subcutaneously. Because both interferons are known to bind to an identical receptor and exert antiviral effects through intracellular signal transduction, the excellent results of IFN-β found in this study may be attributed to the multiple doses allowed by the intravenous route.

Keywords: Chronic hepatitis B, Hepatitis B e antigen, Hepatitis B virus, Interferon beta, Multiple daily dosing, Short-term treatment, Intravenous injection

INTRODUCTION

The increasing prevalence of chronic hepatitis caused by hepatitis B or C virus infection represents a concern in many regions worldwide. Interferons (IFN) are widely used in the treatment of the disease. With the recent launch of lamivudine, adefovir, and entecavir, the number of treatment options for chronic hepatitis B has increased. Treatment with these oral nucleoside analogues has serious drawbacks, such as the development of resistant HBV strains[1,2] and the need for years of treatment[3,4] or even a lifetime therapy. Thus, a large number of patients still require IFN therapy, which is effective in a relatively short period of time. Recently, however, in some patients, the treatment with IFN is often prolonged up to 24-48 wk to improve efficacy[5–7]. IFN-α is administered intramuscularly or subcutaneously and may be associated with such adverse effects as fatigue, insomnia, anorexia, and alopecia[7,8]. These effects presumably result from prolonged elevation of blood IFN levels. Prolonged exposure to higher levels of the circulating drug may produce a greater therapeutic effect while inducing greater adverse effects[9,10]. Treatment for a higher therapeutic effect without consideration of the burden on patients is not a good therapeutic strategy.

In Japan, IFN preparations for the treatment of hepatitis B include IFN-α for intramuscular or subcutaneous administration and IFN-β for intravenous administration[11]. Both IFN-α and IFN-β bind to the an identical IFN receptor and induce PKR and other antiviral proteins via intracellular signal transduction systems represented by JAK/STAT[12]. Because of the intravenous route, the blood concentration of IFN-β reaches its peak immediately after infusion and then decreases rapidly[13]. Decrease or loss of efficacy by receptor down-regulation[14–16] and adverse effects with IFN therapy are less likely to occur because blood level of IFN-β does not maintain after signal transduction via the IFN receptor. The receptor function is maintained, and thus frequent dosing of IFN-β is likely to produce greater efficacy. Indeed, in patients with hepatitis C, we found that IFN-β in divided doses administered in the morning and evening was more effective than that administered once daily at the same total dose[17].

For the development of short-term IFN therapy for hepatitis B, in the present study we investigated a 4-wk, multiple daily dosing of intravenous IFN-β, a new regimen that produced therapeutic effects similar to those achieved by 24-wk or 1-year treatment with IFN-α.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

Among Japanese adult patients with chronic hepatitis B who were positive for HBeAg and HBV-DNA and presented at our hospital from 1996 to 2002, 26 patients were enrolled in this open-label study. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the patients consented to the experimental treatment of hepatitis B. Inclusion criteria were: age of 20 years or older, blood HBeAg positivity, blood HBV-DNA positivity, and persistent abnormal elevation of ALT levels. Exclusion criteria included: coinfection with hepatitis C virus or HIV, presence of hepatocellular carcinoma, symptoms caused by decompensated cirrhosis, alcoholic, autoimmune, drug-induced, or other non-viral liver disorders, and hypersensitivity to IFN-β. Any herbal medicines were discontinued during the treatment with IFN-β.

Treatment methods

Human fibroblast-derived natural IFN-β (FERON®, Toray Industries Inc., Japan) was used; 1 to 3 MIU was dissolved in 100 mL of 5% glucose or isotonic saline solution for injection and infused intravenously for about 10 minutes. The dosing schedule comprised 2 MIU in the morning and 1 MIU in the evening (twice daily) at d 1 of treatment, 3 MIU in the morning and evening (twice daily) from d 2 through d 7, and 1 MIU each in the morning, in the afternoon, and at bedtime (thrice daily) from d 8 to d 28, with a total dose of 102 MIU administered over a treatment period of 28 d. Patients were followed up for 24 wk after the end of the IFN-β therapy.

Laboratory methods

Blood samples were collected immediately before the start of treatment, weekly during the treatment, and monthly during the follow-up period. Biochemical and hematological tests were performed each time. HBsAg was measured by reversed passive hemagglutination (R-PHA), anti-HBs was measured by passive hemagglutination (PHA), HBeAg and anti-HBe were measured by radioimmunoassay (RIA). HBV-DNA polymerase activity was measured by radioassay. Serum HBV-DNA was measured by branched DNA probe assay (Chiron Corp, USA) with a detection sensitivity of 0.70 megaequivalents (Meq) per milliliter. Anti-hepatitis C virus antibodies were measured by enzyme immunoassay (EIA). In addition, 2’-,5’-oligoadenylate synthetase (2-5AS), an indicator of IFN activity, was quantitatively measured by RIA.

Statistical analysis

Values are given as either mean ± SD or median and range. For comparison, Student’s t-test or the Chi-square test were used. Statistical tests were two-sided, and a P value of less than 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

RESULTS

Patient population

Clinical characteristics of the 26 patients with HBeAg positive chronic hepatitis B at beginning of the treatment are shown in Table 1. All patients received a total dose of 102 MIU of IFN-β over a period of 28 d, and none of them dropped out because of adverse effects or other reasons.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics at the beginning of the treatment

| Characteristics | Baseline |

| Age (yr) | 31.8 ± 7.01 |

| Sex (male/female) | 19/7 |

| ALT (U/L) | 246.9 ± 154.21 |

| HBV DNA (≥ 10/< 10 Meq/mL) | 16/10 |

| HBV DNA polymerase (cpm) | 750.5 (10-10 710)2 |

| PLT (× 104/mm3) | 19.3 ± 10.71 |

mean ± SD;

Median (range).

Clinical outcomes

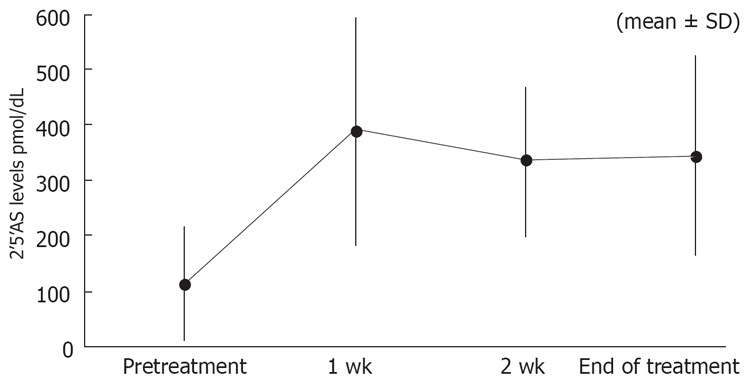

Six months after the end of IFN administration, loss of HBV-DNA occurred in 13 (50.0%) patients, loss of HBeAg in 9 (34.6%), loss of HBV-DNA and HBeAg in 9 (34.6%), development of anti-HBe in 10 (38.5%), and HBe seroconversion in 8 (30.8%). The last parameter is a measure of the therapeutic effect, defined by the loss of HBeAg and the subsequent development of anti-HBe. ALT levels normalized in 11 (42.0%) of the 26 patients. The percentage of patients, which became negative for HBV-DNA, HBeAg, and the change in ALT levels during/after the treatment are shown in Table 2 and Figure 1, respectively.

Table 2.

Response rate in patients with HBeAg positive chronic hepatitis B by interferon-β treatment (%)

| wk 1 | wk 2 | End of the treatment | 6 mo after treatment | |

| HBV-DNA negative | 5/26 (19.2) | 5/26 (19.2) | 10/26 (38.5) | 13/26 (50.0) |

| HBeAg and HBV-DNA negative | 4/26 (15.4) | 9/26 (34.6) |

Figure 1.

Change in ALT levels during treatment with interferon-β and during the follow-up.

Baseline HBV DNA polymerase activity and virological response

Patients were stratified according to baseline DNA polymerase activity (less than 1000 cpm vs 1000 cpm or more), and virological responses were recorded. Among 15 patients with an activity lower than 1000 cpm, 11 (73.3%) had a complete virological response, and 4 (26.7%) had no response. Among the 11 patients with an activity of 1000 cpm or more, 2 (18.2%) had a complete virological response, and 9 (81.8%) had no response.

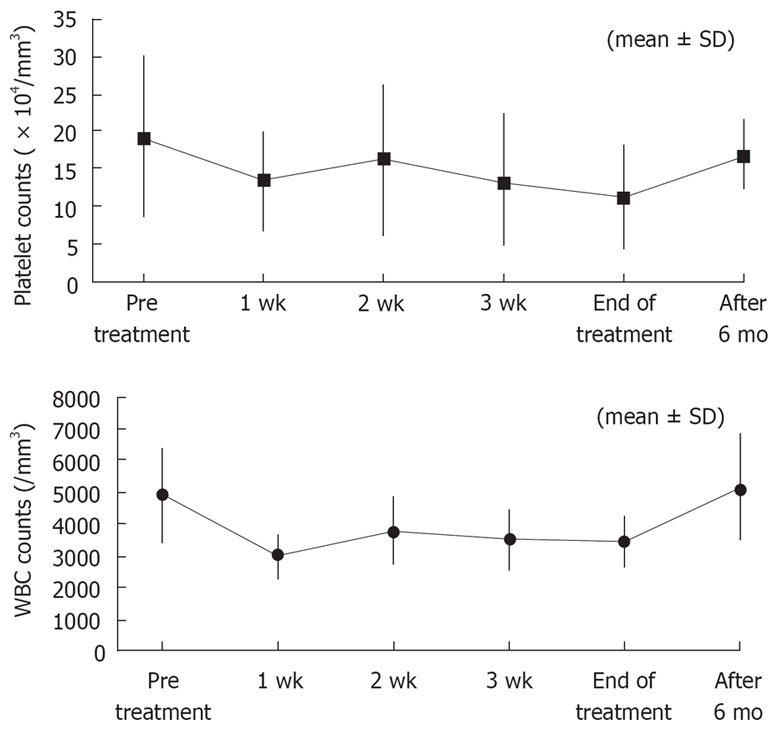

2-5AS

Figure 2 shows the change in 2-5AS levels. The level of 2-5AS at baseline was 114.8 ± 102.1 (mean ± SD). The levels at wk 1, 2, and at the end of treatment were 389.9 ± 205.3, 333.3 ± 133.4, and 344.3 ± 181.2, respectively.

Figure 2.

Change in 2’5’AS levels during treatment.

Adverse effects

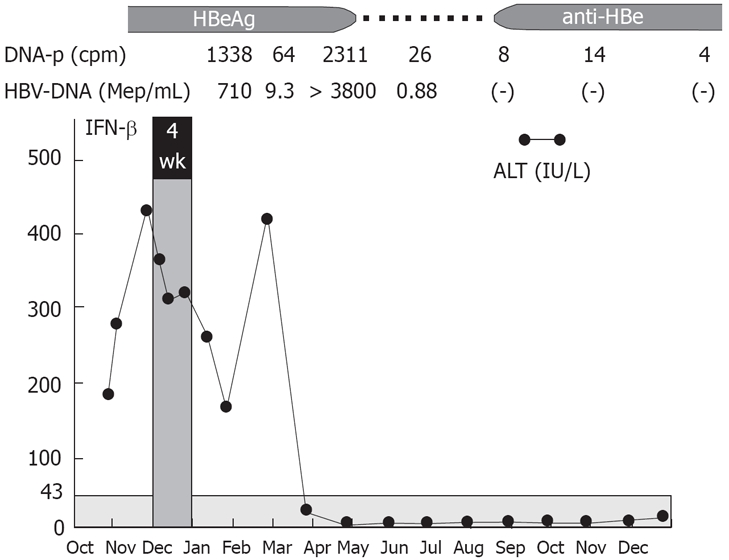

No patients discontinued treatment because of adverse effects, with a treatment completion rate of 100%. Fever was mild because antipyretic loxoprofen sodium was administered before intravenous infusion to suppress IFN-induced fever. During treatment with IFN, no patients experienced depression. There was no proteinuria, severe thrombocytopenia or leukopenia (as shown in Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Changes in platelet and WBC counts.

DISCUSSION

Approximately 10 years ago, the IFN therapy for chronic hepatitis B was administered for up to 4 wk in Japan. However, a 24-wk regimen has been recently used because a longer treatment seems to improve the efficacy. In the present study, we used a short-term, intravenous therapy of 4 wk, which seems to be against the recent recommendations for long-term regimens. However, 4-wk multiple daily dosing of intravenous IFN-β used in our study produced therapeutic effects similar to those achieved by 12-wk or 24-wk IFN-α or 48-wk peg-IFN-α, which are indicated by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases[18,19]. The HBe seroconversion rate with IFN-β in this study was 31%, which was higher than the reported 12-18% with IFN-α[18,20], lamivudine[18,21–23], or adefovir[19,24], and which was almost equal to that achieved by a 48-wk therapy with peg-IFN-α[25] (Table 3). In the United States, the distribution of HBV genotypes was reported as genotypes A (33%), B (21%), C (34%), D (9%), E (1%), F (1%), and G (1%)[26]. Given that the majority (about 80%) of Japanese patients infected with HBV has IFN-resistant genotype C[27], the multiple daily dosing of intravenous IFN-β used in this study appears to be a beneficial treatment.

Table 3.

Comparison of response rates in patients with HBeAg positive chronic hepatitis B at 6 mo after the treatment (%)

| INF-β (iv) 4 wk | INF-α (sc or im) 12-24 wk | Lamivudine 1 yr | Adefovir dipivoxil 48 wk | Pegylated interferon-α 48 wk | |

| Loss of serum HBV DNA | 50 | 37 | 44 | 21 | 32 |

| Loss of HBeAg | 35 | 33 | 17-32 | 24 | 34 |

| HbeAg seroconversion | 31 | Difference of 18 | 16-18 | 12 | 32 |

| Loss of HBsAg | 8 | < 1 | 0 | 3 | |

| Normalization of ALT | 42 | Difference of 23 | 41-72 | 48 | 41 |

| Histological improvement | 49-56 | 53 | 38 | ||

| Durability of the response | 80-90 | 50-80 | 82 |

Our results suggest that HBV DNA polymerase activity at baseline before the treatment may be used to predict the therapeutic effect of IFN to some degree. Multiple daily dosing of IFN-β may be the regimen of first-line choice in patients with baseline HBV DNA polymerase activity less than 1000 cpm because 73.3% of those patients had a complete virological response. We believe that the direct antiviral effect of IFN on HBV is enough to achieve a complete response in those patients, whereas an appropriate host immune response are also needed in patients with a polymerase activity of 1000 cpm or more indicating rapid proliferation of HBV. A typical example is shown in Figure 4. The patient had an HBV DNA polymerase activity of 1338 cpm and an HBV-DNA level of 710 Meq/mL before the IFN therapy. After the end of IFN-β administration, an increase in HBV-DNA and subsequent rapid increase in ALT levels (so-called Schub) occurred, followed by the loss of HBeAg, HBV-DNA, and DNA polymerase, normalization of ALT levels, and development of anti-HB. The rapid increase in ALT levels probably resulted from the host’s immune response to the rapid increase in the HBV proliferation following the regimen and the subsequent rapid elimination of infected hepatocytes in an appropriate manner.

Figure 4.

Typical pattern of clinical course with transient increase in ALT level after treatment with interferon-β.

Our dosing regimen had a good safety profile with a low incidence of mild adverse effects and no serious adverse effects. This may be attributed to lower daily doses of 3 MIU from d 8 onward and a short treatment period of 1 mo. Although platelet and leukocyte counts decreased at wk 1 compared with baseline levels, the counts remained unchanged thereafter until the end of treatment and almost returned to baseline levels after completion of therapy. Our previous experience suggested that thrombocytopenia and proteinuria should be closely monitored during treatment with IFN-β at doses of 3 MIU twice daily. However, cytopenia did not worsen because of switching to 1 MIU thrice daily from d 8. The levels of 2-5AS in blood (mean ± SD) at baseline and wk 1, 2, and 4 of treatment were 133.9 ± 122.2, 445.0 ± 209.7, 335.0 ± 139.9, and 387.8 ± 200.7, respectively, and remained elevated during treatment, suggesting that the dose regimen produced a potent and durable antiviral effect despite a modest cytopenia.

In general, the pharmacokinetics of an intravenously administered drug are characterized by a higher blood elimination rate, higher peak blood concentration, and greater tissue distribution than an intramuscularly administered drug, and these are also true of IFN. Different types of IFN formulations are available for therapy, and human fibroblast IFN-β is applicable to intravenous administration for the treatment of hepatitis in Japan.

We chose intravenous administration and multiple daily dosing because of the following three reasons. First, intravenously administered IFN-β is rapidly eliminated from the blood and below the detection limit shortly after administration[13]. Compared with intramuscularly or subcutaneously administered IFN-α, IFN-β accumulates to a lesser degree and is likely to have less adverse effects[28]. Second, blood concentrations of IFN administered intravenously in multiple daily doses fluctuate with high blood levels and rapid elimination rates. Accordingly, this regimen is likely to avoid persistently elevated blood IFN levels and resultant downregulation of the IFN receptor[14–16], which is likely to occur after intramuscular or subcutaneous administration. The avoidance of the receptor downregulation allows effective binding of IFN and its receptor, and triggers the host defense mechanisms a few times a day to eliminate the virus. Third, the drug administered intravenously is more extensively distributed into organs than that administered intramuscularly. For elimination of HBV present in hepatocytes, intravenous dosing is considered as an effective route of administration, which allows extensive delivery of IFN to the liver. When IFN-α, which was induced by treating human leukocytes with the Sendai virus, was administered intravenously or intramuscularly to rats, IFN-α was detectable in the liver at 10 and 30 min but not at 1 h after intravenous administration whereas IFN levels remained below the detection limit for 4 h in rats receiving an intramuscular administration[29]. In patients with hepatitis, a transient increase in ALT levels is often observed after intravenous administration of IFN[30]. Because IFN distributes in the liver at high concentrations after intravenous administration, extensive loss of infected hepatocytes may occur, resulting in an increase in ALT levels.

When IFN or any other cytokine that exerts a pharmacological effect via receptor binding is administered, it is important to choose an appropriate route of administration that ensures effective delivery of the drug to the target-cells. An ideal pharmacokinetic profile should include a rapid increase to effective blood concentrations and a rapid elimination after receptor binding to avoid downregulation of the receptor. We believe that intravenous IFN therapy can also be used effectively for the treatment of other diseases including cancer, infection with HIV, and SARS. However, intravenous IFN is now available only in Japan. For further promotion of research on the establishment of intravenous IFN therapy as a convenient, general way of treating these diseases, intravenous IFN should preferably be available in other countries.

Oral nucleoside analogues, such as lamivudine, adefovir, and entecavir, have a potent effect in suppressing hepatitis B virus; however, most patients relapse and become positive for the virus after discontinuation of treatment. Thus, these drugs should be taken for a few years or the rest of patients’ lives. These agents also cause problems including development of resistant strains and fetotoxicity, which discourages physicians from administering these agents in pregnant, parturient, and nursing women. Meanwhile, IFN therapy tends to continue for more than 6 months, and increased adverse effects associated with prolonged therapy have become a significant problem. In Japan, both physicians and patients have great difficulty coping with these problems and they are waiting for new effective treatments that ensure improvement in the quality of life for patients.

Short-term treatment with multiple daily dosing of IFN-β used in the present pilot study has fewer adverse effects, good therapeutic effects, and reproducibility to some degree. Further studies and randomized clinical trials are required to confirm our promising results.

COMMENTS

Background

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) is a major cause of liver disease worldwide, ranging from acute and chronic hepatitis to cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Therefore, in order to improve the hepatitis and cirrhosis, and decrease the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma on the patients of chronic hepatitis B, it is extremely important to achieve sustained suppression of HBV replication, normalize serum alanine aminotransferase (ATL) level, and induce seroconversion by therapies. Recently, interferon (IFN)-α (conventional and pegylated) with or without nucleoside analogues or nucleoside analogues only are used for therapy. However, available therapies are suboptimal.

Research frontiers

Therapies using IFN-α and/or nucleotide analogues are needed a long period to treat. Furthermore, those therapies are associated with some side effects. So, the authors tried to establish the new therapeutic protocol using IFN-β, because IFN-β belongs to typeI IFN family like IFN-α and there were some reports that indicated the treatment of IFN-β twice a day was more effective than that of IFN-α or IFN-β once a day in chronic hepatitis C patients.

Innovations and breakthroughs

In this study, the author’s have evaluated the efficacy of a short term (4 wk), multiple daily dosing therapeutic protocol using IFN-β for chronic hepatitis B patients. As a result, the therapeutic efficacy of that regimen is similar to that of PEG-IFN-α treatment for 24 wk or 1 year. Furthermore, the side effects of IFN-β treatment in this study were less than those of PEG-IFN-α or IFN-α treatment for 24 wk or 1 year. Therefore, this treatment method of IFN-β few times a day is more effective than standard therapeutic protocols on chronic hepatitis B patients for the first time.

Applications

In the present pilot study, the authors indicated that the treatment protocol of IFN-β in this study could improve a rate of side effects compare with the standard IFN-α or PEG-IFN-α treatment protocol without loss of therapeutic effects. Further studies and randomized clinical trials are required to confirm the indication of short term therapy for chronic hepatitis B.

Terminology

It has reported that the treatment of IFN-β twice a day is more effective than that of IFN-α or IFN-β once a day in chronic hepatitis C patients. However, there is no investigation that described the efficacy of treatment of IFN-β twice a day on chronic hepatitis B patients.

Peer review

The authors may want to provide end-of-treatment data as well, in addition to the SVR data that they have provided. Overall, I feel this is a novel approach that needs wider consideration.

Peer reviewers: Philip Abraham, Dr, Professor, Consultant Gastroenterologist & Hepatologist, P. D. Hinduja National Hospital & Medical Research Centre, Veer Savarkar Marg, Mahim, Mumbai 400 016, India; Richard A Rippe, Dr, Department of Medicine, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-7038, United States

S- Editor Piscaglia AC L- Editor Rippe R E- Editor Lu W

References

- 1.Honkoop P, Niesters HG, de Man RA, Osterhaus AD, Schalm SW. Lamivudine resistance in immunocompetent chronic hepatitis B. Incidence and patterns. J Hepatol. 1997;26:1393–1395. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(97)80476-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoofnagle JH. Therapy of viral hepatitis. Digestion. 1998;59:563–578. doi: 10.1159/000007532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liaw YF, Leung NW, Chang TT, Guan R, Tai DI, Ng KY, Chien RN, Dent J, Roman L, Edmundson S, et al. Effects of extended lamivudine therapy in Asian patients with chronic hepatitis B. Asia Hepatitis Lamivudine Study Group. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:172–180. doi: 10.1053/gast.2000.8559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leung NW, Lai CL, Chang TT, Guan R, Lee CM, Ng KY, Lim SG, Wu PC, Dent JC, Edmundson S, et al. Extended lamivudine treatment in patients with chronic hepatitis B enhances hepatitis B e antigen seroconversion rates: results after 3 years of therapy. Hepatology. 2001;33:1527–1532. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.25084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Janssen HL, Gerken G, Carreno V, Marcellin P, Naoumov NV, Craxi A, Ring-Larsen H, Kitis G, van Hattum J, de Vries RA, et al. Interferon alfa for chronic hepatitis B infection: increased efficacy of prolonged treatment. The European Concerted Action on Viral Hepatitis (EUROHEP) Hepatology. 1999;30:238–243. doi: 10.1002/hep.510300113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sakai T, Shiraki K, Inoue H, Okano H, Deguchi M, Sugimoto K, Ohmori S, Murata K, Nakano T. Efficacy of long-term interferon therapy in chronic hepatitis B patients with HBV genotype C. Int J Mol Med. 2002;10:201–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cooksley WG, Piratvisuth T, Lee SD, Mahachai V, Chao YC, Tanwandee T, Chutaputti A, Chang WY, Zahm FE, Pluck N. Peginterferon alpha-2a (40 kDa): an advance in the treatment of hepatitis B e antigen-positive chronic hepatitis B. J Viral Hepat. 2003;10:298–305. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2893.2003.00450.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wong JB, Koff RS, Tine F, Pauker SG. Cost-effectiveness of interferon-alpha 2b treatment for hepatitis B e antigen-positive chronic hepatitis B. Ann Intern Med. 1995;122:664–675. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-122-9-199505010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sagir A, Wettstein M, Heintges T, Haussinger D. Autoimmune thrombocytopenia induced by PEG-IFN-alpha2b plus ribavirin in hepatitis C. Dig Dis Sci. 2002;47:562–563. doi: 10.1023/a:1017964002402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lambotte O, Gelu-Simeon M, Maigne G, Kotb R, Buffet C, Delfraissy JF, Goujard C. Pegylated interferon alpha-2a-associated life-threatening Evans' syndrome in a patient with chronic hepatitis C. J Infect. 2005;51:e113–e115. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2004.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Suzuki F, Arase Y, Akuta N, Tsubota A, Suzuki Y, Sezaki H, Hosaka T, Someya T, Kobayashi M, Saitoh S, et al. Efficacy of 6-month interferon therapy in chronic hepatitis B virus infection in Japan. J Gastroenterol. 2004;39:969–974. doi: 10.1007/s00535-004-1430-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stark GR, Kerr IM, Williams BR, Silverman RH, Schreiber RD. How cells respond to interferons. Annu Rev Biochem. 1998;67:227–264. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hino K, Kondo T, Yasuda K, Fukuhara A, Fujioka S, Shimoda K, Niwa H, Iino S, Suzuki H. Pharmacokinetics and biological effects of beta interferon by intravenous (iv) bolus administration in healthy volunteers as compared with iv infusion. Jpn J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1998;19:625–635. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lau AS, Hannigan GE, Freedman MH, Williams BR. Regulation of interferon receptor expression in human blood lymphocytes in vitro and during interferon therapy. J Clin Invest. 1986;77:1632–1638. doi: 10.1172/JCI112480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nakajima S, Kuroki T, Kurai O, Kobayashi K, Yamamoto S. Interferon receptors during treatment of chronic hepatitis B with interferon. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1989;4:419–427. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.1989.tb01739.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nakajima S, Kuroki T, Shintani M, Kurai O, Takeda T, Nishiguchi S, Shiomi S, Seki S, Kobayashi K. Changes in interferon receptors on peripheral blood mononuclear cells from patients with chronic hepatitis B being treated with interferon. Hepatology. 1990;12:1261–1265. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840120602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Okushin H, Morii K, Kishi F, Yuasa S. Efficacy of the combination therapy using twice-a-day IFN-beta followed by IFN-alpha-2b in treatment for chronic hepatitis C. Kanzo. 1997;38:11–18. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lok AS, McMahon BJ. Chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2001;34:1225–1241. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.29401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lok AS, McMahon BJ. Chronic hepatitis B: update of recommendations. Hepatology. 2004;39:857–861. doi: 10.1002/hep.20110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wong DK, Cheung AM, O'Rourke K, Naylor CD, Detsky AS, Heathcote J. Effect of alpha-interferon treatment in patients with hepatitis B e antigen-positive chronic hepatitis B. A meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 1993;119:312–323. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-119-4-199308150-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lai CL, Chien RN, Leung NW, Chang TT, Guan R, Tai DI, Ng KY, Wu PC, Dent JC, Barber J, et al. A one-year trial of lamivudine for chronic hepatitis B. Asia Hepatitis Lamivudine Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:61–68. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199807093390201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dienstag JL, Schiff ER, Wright TL, Perrillo RP, Hann HW, Goodman Z, Crowther L, Condreay LD, Woessner M, Rubin M, et al. Lamivudine as initial treatment for chronic hepatitis B in the United States. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1256–1263. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199910213411702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schalm SW, Heathcote J, Cianciara J, Farrell G, Sherman M, Willems B, Dhillon A, Moorat A, Barber J, Gray DF. Lamivudine and alpha interferon combination treatment of patients with chronic hepatitis B infection: a randomised trial. Gut. 2000;46:562–568. doi: 10.1136/gut.46.4.562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marcellin P, Chang TT, Lim SG, Tong MJ, Sievert W, Shiffman ML, Jeffers L, Goodman Z, Wulfsohn MS, Xiong S, et al. Adefovir dipivoxil for the treatment of hepatitis B e antigen-positive chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:808–816. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lau GK, Piratvisuth T, Luo KX, Marcellin P, Thongsawat S, Cooksley G, Gane E, Fried MW, Chow WC, Paik SW, et al. Peginterferon Alfa-2a, lamivudine, and the combination for HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:2682–2695. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chu CJ, Lok AS. Clinical significance of hepatitis B virus genotypes. Hepatology. 2002;35:1274–1276. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.33161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Orito E, Ichida T, Sakugawa H, Sata M, Horiike N, Hino K, Okita K, Okanoue T, Iino S, Tanaka E, et al. Geographic distribution of hepatitis B virus (HBV) genotype in patients with chronic HBV infection in Japan. Hepatology. 2001;34:590–594. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.27221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Festi D, Sandri L, Mazzella G, Roda E, Sacco T, Staniscia T, Capodicasa S, Vestito A, Colecchia A. Safety of interferon beta treatment for chronic HCV hepatitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:12–16. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v10.i1.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mura N, Matsuzawa H, Ueda H, Sakashita K, Nakamura K, Uemura H, Arao S, Hamanaka N, Chisaka T, Yagi N, et al. Pharmacokinetics of FPI-31. Jpn Pharmacol Ther. 1993;21:2211–2226. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fujimori K, Mochida S, Matsui A, Ohno A, Fujiwara K. Possible mechanisms of elevation of serum transaminase levels during interferon-beta therapy in chronic hepatitis C patients. J Gastroenterol. 2002;37:40–46. doi: 10.1007/s535-002-8131-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]