Abstract

Background

This S3 guideline takes positions on currently contentious issues in the classification and treatment of fibromyalgia syndrome (FMS).

Methods

A panel of experts from 10 specialist societies and patients belonging to 2 patient self-help organizations reviewed a total of approximately 8000 publications. Recommendations were developed according to the suggested procedure for S3 guidelines and were then reviewed and approved by the boards of the participating specialist societies. The steering committee ensured that the literature review and the recommendations were kept up to date.

Results

Because this disorder is defined by its symptoms and signs, rather than by any consistently identifiable bodily lesion, the term "fibromyalgia syndrome" is a more appropriate designation for it than "fibromyalgia." FMS is defined by the criteria of the American College of Rheumatology and is classified as a functional somatic syndrome. FMS is diagnosed from the typical constellation of symptoms and by the exclusion of inflammatory and metabolic diseases that could cause the same symptoms. A stepwise treatment approach in which the patient and the physician decide jointly on the treatment options is recommended. The most strongly recommended forms of treatment are aerobic exercise, amitriptyline, cognitive behavioral therapy, and spa therapy.

Conclusions

The guideline recommendations are intended to promote more effective treatment of this disorder.

Keywords: fibromyalgia, functional somatic syndrome, guideline, diagnosis, treatment

According to population-based studies, the estimated prevalence of chronic widespread pain (CWP) is 7% to 11%, and that of the fibromyalgia syndrome (FMS) is 1% to 5% (1). Patients often suffer considerable distress from their condition as well as an impairment of their health-related quality of life, resulting in considerable direct and indirect costs of illness (1, e1). Patients and treating physicians alike are often disappointed by the results of treatment (2).

The classification and treatment of this symptom complex are controversial matters, not only within and among the medical specialty societies, but also among patients and their families. Many rheumatologists, neurologists, and pain specialists, as well as many patients, consider fibromyalgia syndrome (FMS) to be a distinct illness associated with pathological changes in the muscles and connective tissue and with characteristic functional abnormalities of the central nervous system (e2, e3). In keeping with this neurobiological conception, the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR), an expert committee composed mainly of rheumatologists, gives its highest-level therapeutic recommendation exclusively to treatment with medications (3). Many specialists in psychosomatic medicine, on the other hand, conceptualize the FMS symptom complex as a type of somatoform disorder (e4), while many psychiatrists see it as a type of affective disorder (e5). These specialists assert that the inappropriate "medicalization of misery" (e6) as a rheumatological disease construct implies that some sort of non-demonstrable rheumatic process exists in the muscles and connective tissue and is responsible for the condition. The psychosomatic conception of FMS leads to a recommendation for treatment with psychotherapy (e7), while the psychiatric conception leads to a recommendation for treatment with psychotropic medications (e8). Many patients reject a reduction of this condition to purely somatic causes.

In view of the controversy about this symptom complex and its unquestioned importance as a public health problem, the time has certainly come for a German interdisciplinary guideline to be issued by a collaboration of all of the specialty societies involved in the treatment of this condition, together with patient representatives (4). This article is intended to inform the reader about the guideline’s position on controversial questions as to the classification, diagnosis, and treatment of the fibromyalgia syndrome.

Methods

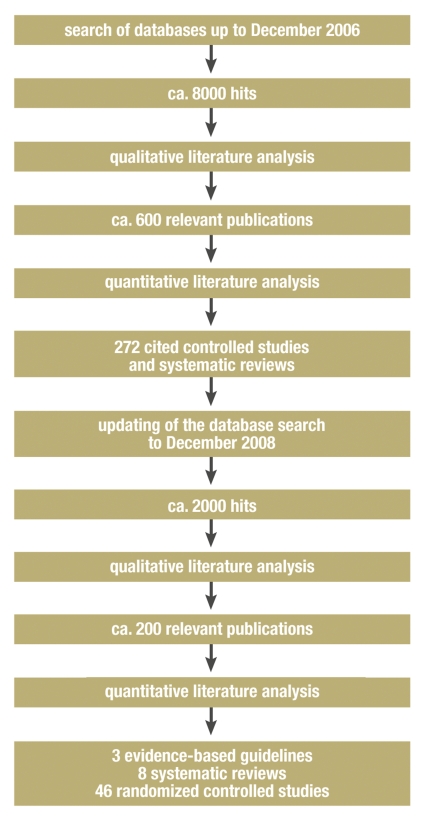

The guideline was developed by a collaborative effort of the German Interdisciplinary Association of Pain Therapy (Deutsche Interdisziplinäre Vereinigung für Schmerztherapie, DIVS), ten medical-scientific specialty societies, and two patient self-help associations. No support from the pharmaceutical industry was sought or obtained, either directly or indirectly. A Guideline Committee with one representative from each of the involved societies or associations bore responsibility for the methods of the guideline (box 1). Nine working groups, comprising a total of 58 persons, were constituted so as to contain a balanced representation with regard to sex, medical specialty, and hierarchical position in the medical and scientific community. The Guideline Secretariat performed a literature search up to December 2006 in the Medline, PsychInfo, Scopus, and Cochrane Library databases, based on the search terms listed in Text Box 2. The reference lists of systematic reviews and evidence-based guidelines were also added to the retrieved literature. The search up to December 2006 retrieved a total of 2101 articles for the "Definition" and "Pathophysiology" working groups and 4523 articles for the others. The text of the guideline cites 272 controlled trials and systematic reviews. The guideline was kept up to date with a further literature search up to December 2008, as a result of which 54 additional randomized, controlled studies and systematic reviews were taken into consideration by the working groups dealing with the treatment of FMS (figure).

Box 1. Members of the steering committee of the involved specialty societies and registered associations.

Association of Scientific Medical Societies in Germany (Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlich Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften, AWMF): PD Dr. med. Ina Kopp*1

German Fibromyalgia Association (Deutsche Fibromyalgie Vereinigung, DFV): Eva Felde*3

German Society for General Medicine and Family Practice (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Allgemeinmedizin und Familienmedizin, DEGAM): Prof. Dr. med. Markus Herrmann

German Neurological Society (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Neurologie, DGN): Prof. Dr. med. Claudia Sommer

German Society of Orthopedics and Orthopedic Surgery (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Orthopädie und Orthopädische Chirurgie, DGOOC): Prof. Dr. med. Marcus Schiltenwolf

German Society of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Physikalische Medizin und Rehabilitation, DGPMR): Dr. med. Martin Offenbächer

German Society for Psychiatry, Psychotherapy, and Neurology (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Psychiatrie, Psychotherapie und Nervenheilkunde, DGPPN): Prof. Dr. med. Detlev Nutzinger

German Society of Psychosomatic Medicine and Psychotherapy (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Psychosomatische Medizin und Psychotherapie, DGPM): Prof. Dr. med. Volker Köllner*2

German Society of Psychological Pain Therapy and Pain Research (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Psychologische Schmerztherapie und Schmerzforschung, DGPSF): PD Dr. soc. Dipl. Psych. Kati Thieme

German Association for the Study of Pain (Deutsche Gesellschaft zum Studium des Schmerzes, DGSS): Dr. med. Bernhard Arnold

German Society for Rheumatology (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Rheumatologie, DGRh): Prof. Dr. med.Wolfgang Eich

German Interdisciplinary Association of Pain Therapy (Deutsche Interdisziplinäre Vereinigung für Schmerztherapie, DIVS): Dr. med. Winfried Häuser*1

German College for Psychosomatic Medicine (Deutsches Kollegium für Psychosomatische Medizin, DKPM): Prof. Dr. med. Peter Henningsen*2

German Rheumatic League (Deutsche Rheuma-Liga, DRL): Sabine Erdmann*3

Society for Paediatric and Adolescent Rheumatology (Gesellschaft für Kinder- und Jugendrheumatologie, GKJR): Dr. med. Hartmut Michels

Central Association of Physical Therapists (Zentralverband der Krankengymnasten und Physiotherapeuten, ZVK): Christl Flügge

*1 The guideline coordinator and the consensus conference coordinator had no vote.

*2 and *3 ―One collective vote.

Box 2. List of search terms.

The search criteria were formed by taking the intersection (AND operator) of the common list of search terms and the specific list for each of the individual working groups.

Common list of search terms for all working groups:

Medline:

"fibromyalgia" [MeSH] OR "fibromyalgia syndrome" OR "chronic widespread pain" OR "widespread musculoskeletal pain"

for the working groups on therapeutic procedures, "guideline" [MeSH] OR "meta-analysis" [MeSH] OR "review" [publication type] OR "review literature" [MeSH] OR "randomized controlled trial" [MeSH] OR "clinical trial" [MeSH]

for the "definition" and "pathophysiology" working groups, "review" [publication type] OR "review literature" [MeSH]

For searches in SCOPUS, ENTREE terms were used as keywords as often as possible. The literature search in the Cochrane Library was performed according to the following strategy: subject "fibromyalgia" or "chronic widespread pain."

Specific lists of search terms for each working group:

| Working group 1 | – | Definition and classification: definition, classification, epidemiology, tender points, prognosis |

| Working group 2 | – | Etiology, pathogenesis, and pathophysiology: pathophysiology, etiopathogenesis, etiology |

| Working group 3 | – | Medications: analgesics, central acting agent, antidepressive agent, central nervous system agents, drug therapy |

| Working group 4 | – | Medical training therapy, physiotherapy, and physical therapy: aerobic, exercise, acupuncture, electroacupuncture, magnet therapy, magnetotherapy, electromagnetic field, massage, chiropractic, balneotherapy, movement therapy, trigger point injection, physical exercise training, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS), laser therapy, ultrasound, body cryotherapy |

| Working group 5 | – | Psychotherapy: cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), behavior therapy, hypnosis, hypnotherapy, guided imagery, relaxation, relaxation training, psychodynamic therapy, (electromyographic) biofeedback (training), meditation, body-centered psychotherapy, behavioral, behavioral psychotherapy, group therapy, operant, psychoanalytic |

| Working group 6 | – | Complementary and alternative techniques: complementary medicine, alternative medicine, CAM, reiki, johrei, qi gong, healing touch, intercessory prayer, therapeutic touch, distant healing, putative energy, Alexander technique, Bowen, chiropractic, craniosacral therapy, feldenkrais, massage, osteopathic, reflexology, Rolfing, Trager bodywork, tui na, neural therapy, acupressure, acupuncture, meditation, imaging, placebo, expectancy, breathing exercise, Traditional Chinese Medicine, ayurvedic, naturopathy, homeopathy, anthroposophy, herbal medicine, phytotherapy, balneology, bath, Junge bath, dietary, diet |

| Working group 7 | – | Multimodal therapy: multidisciplinary treatment, multimodal treatment, combined modality therapy, rehabilitation, occupational therapy |

| Working group 8 | – | Children and adolescents: adolescent, children, childhood, juvenile |

| Working group 9 | – | General principles of treatment and patient education: patient education, patient management, primary care |

Figure.

Literature search flowchart of the working groups on the treatment of fibromyalgia syndrome

The working groups communicated with the Guidelines Secretariat, and with each other, by e-mail and by means of a password-protected Internet platform. The original articles used for recommendations were accessible on a password-protected Internet platform. The Guideline Secretariat gave the working groups logistical assistance in the evaluation of the literature. Evidence levels were graded according to the schema of the Centre of Evidence-Based Medicine in Oxford, U. K. (e9).

The formulation and grading of the recommendations was performed in a stratified, formal consensus procedure that was analogous to that of the (German) Program for National Care Guidelines (Programm für Nationale Versorgungsleitlinien), involving three Delphi procedures and two consensus conferences (5). PD Dr. med. Kopp, a representative of the Association of Scientific Medical Societies in Germany (Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften, AWMF), served as moderator for the consensus conferences. Whenever a vote was taken, each participating specialty area or patient self-help association had one vote. Consensus strength was graded according to the schema of the German Society for Digestive and Metabolic Diseases (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Verdauungs- und Stoffwechselerkrankungen) (6). The guideline was reviewed and approved by the board of directors of each of the participating scientific societies (7). It was accepted by the AWMF on 17 April 2008 (registration number 041/004, www.uni-duesseldorf.de/AWMF/ll/041-004.htm). The text of the guideline (1) and a report of its methods (7) were published in June 2008 in Issue No. 3 of the journal Der Schmerz. A version for patients can be seen at the Internet address www.uni-duesseldorf.de/AWMF/ll/041-004p.htm (in German).

The guideline’s evidence and recommendation grades were updated by the Guideline Committee in a Delphi procedure on the basis of a literature search up to December 2008.

Results

Definition

The clinical picture of chronic widespread pain was already described in the 19th century. It was subsumed thereafter in the concepts of "soft-tissue rheumatism" and "generalized insertion tendinopathy." The term "fibromyalgia" was first used by Hench in 1976 (e10). Smythe and Moldofsky (e11) and Yunus et al. (e12) formulated diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia, while Müller and Lautenschläger (1990) formulated diagnostic criteria for generalized tenomyopathy (e13). Its main manifestations were defined as pain in multiple parts of the body, further constitutional and vegetative manifestations, and local hyperalgesia at muscle and tendon insertions ("tender points"). The diagnostic criteria of the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) have gained worldwide acceptance as the prevailing definition of FMS. These criteria define FMS as chronic pain (i.e., pain for more than 3 months) in multiple parts of the body, i.e.,

pain in the axial skeleton (cervical spine or anterior chest or thoracic spine or lumbar spine), and

pain in the right and left sides of the body, and

pain above and below the waist, and

pain on palpation of at least 11 of 18 defined tender points (8).

Unlike the definitions of other illnesses that have no known underlying structural tissue damage or biochemical abnormality, e.g., chronic tension headache in neurology or irritable bowel syndrome in gastroenterology, the defining criteria of the ACR include not only disease manifestations and duration, but also a physical finding, i.e., tenderness on palpation of tender points. The diagnostic validity of the ACR criteria outside the rheumatological context has not been tested, nor has the validity of its differentiation of the fibromyalgia syndrome from somatoform or affective disorders. The utility of tender points for the classification and diagnosis of FMS remains a matter of controversy. Their use is not very reliable for three reasons: the verbal instructions to be given to the patient before and during the testing of tender points are not standardized; there are no instructions for the examining physician regarding the intensity and duration of the pressure to be applied to these points; and, finally, the entity "tenderness" is inadequately operationalized (9). Nonetheless, some rheumatologists think testing for tender points is useful (10).

Epidemiological studies have shown that the ACR’s classifying criteria for FMS (sites of pain, tender points) are distributed in a continuum across the general population (12). Chronic widespread pain (CWP) and FMS, as defined by the ACR classifying criteria, thus cannot be considered categorical or distinct disease entities. FMS can be conceptualized as one possible endpoint of a pain/distress continuum (14).

Classification

The problem of classifying chronic bodily complaints without any clearly demonstrable physical lesion (functional somatic syndromes) is common to all medical specialties. The definitions within each specialty do not take account of the bodily complaints and mental symptoms that most patients have outside the area of the particular specialty in question (15, 16).

Chapter XIII of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10), which is entitled "Diseases of the musculoskeletal system and connective tissue," contains the heading M79, "other soft tissue disorders, not elsewhere classified," under which "fibromyalgia" is found as item M79.7 (17). The guideline recommends classifying FMS as a functional somatic syndrome rather than a mental disorder (1). Comorbid mental disorders are to be additionally coded.

Persistent somatoform pain disorder—40% to 70% of patients can be found to have relevant emotional or psychosocial conflicts that are temporally related to the appearance or intensification of the painful symptoms (2). 60% of the patients spontaneously report having such conflicts (18).

Affective disorders and anxiety disorders—Depending on the level of care and the criteria and diagnostic instruments that are applied, the prevalence of affective disorders in patients with FMS is 20% to 80% (e14), while that of anxiety disorders is 15% to 65% (e8).

Polysymptomatic functional somatic syndrome—Depending on the level of care and the criteria and diagnostic instruments that are applied, the prevalence of other functional somatic syndromes (FSS), such as irritable bowel syndrome or chronic fatigue syndrome, in patients with FMS ranges from 20% to 80% (19).

Diagnostic evaluation

FMS is diagnosed on the basis of the characteristic symptoms and the exclusion of other diseases that can lead to the same symptom pattern. The principles of diagnostic evaluation are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. General diagnostic principles.

| Structured assessment of pain (pain sketch) |

| Thorough history: |

| - General symptoms (fatigue, weakness), further physical complaints (e.g., irregular bowel habits, abdominal pain, dyspepsia, urinary symptoms, sicca symptoms, general irritability) and mental-health complaints (e.g., disturbances of sleep or concentration, lack of drive) |

| - Accompanying illnesses |

| - Current medications |

| - Impaired activities of daily living |

| - Subjective notions of causation and fears relating to illness |

| - Psychosocial stressors |

| Physical examination of the entire body |

| Planned ancillary diagnostic testing for the rapid exclusion of other conditions |

History

The use of a pain sketch and a thorough medical history are recommended.

Physical examination

A complete physical examination is necessary for the diagnostic evaluation of structural diseases associated with chronic pain in multiple parts of the body, e.g., joint swelling in inflammatory rheumatic diseases or skin changes in Fabry disease. Examination of the ACR tender points is optional.

Ancillary diagnostic testing

The basic ancillary tests that are recommended as part of the initial evaluation of every patient are listed in Table 2.

Table 2. Obligatory laboratory testing in the initial evaluation of chronic widespread pain.

| - Erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, complete blood count (provides evidence of polymyalgia rheumatica or rheumatoid arthritis) |

| - Creatine kinase (evidence of muscle disease) |

| - Serum calcium (evidence of hypercalcemia) |

| - Basal thyroid-stimulating hormone (evidence of hypothyroidism) |

There is no reason to test routinely for antibodies associated with inflammatory rheumatic diseases in the absence of clinical evidence. No further ancillary studies (i.e., no further laboratory testing, clinical neurophysiological tests, or imaging studies) are recommended in patients who have the characteristic symptoms of fibromyalgia syndrome and show no clinical evidence of systemic, orthopedic, or neurological disease (1).

Diagnostic testing for the exclusion of other conditions should be performed in a planned and temporally efficient manner. If the patient’s symptoms are characteristic, it should be stated that FMS is the most likely diagnosis before further diagnostic testing is initiated to exclude other conditions (e15).

Specialized medical examination

Examination by a specialist is necessary if there is any clinical suspicion that the patient’s chronic, widespread pain might be due to a systemic (internal medical), orthopedic, or neurological disease. The clinical constellations for which the guideline recommends a specialized psychotherapeutic examination (i.e., examination by a physician with specialty qualifications in psychosomatic medicine and psychotherapy, by a psychotherapist who is either a physician or a psychologist, or by a board-certified psychiatrist and psychotherapist) are listed in Table 3 (1).

Diagnostic criteria

Striking a compromise between the conflicting positions outlined above in the Introduction, the German guideline recommends that fibromyalgia syndrome be diagnosed either according to the criteria of the American College of Rheumatology or according to symptom-based criteria (CWP, a feeling of stiffness and swelling of the hands, feet, or face, and physical or emotional fatigue or sleep disturbance) (1).

Diagnosis based on these symptoms alone, without any testing of tender points, is recommended on the basis of information from FMS patients, almost all of whom stated that they suffered from these symptoms (18, e16).

In Germany, a patient’s complaint of pain when certain so-called control points are pressed (e.g, the hypothenar muscles, middle phalanges of the fingers, and the frontal eminences) is sometimes held to cast doubt on the diagnosis of FMS, leading the physician to postulate that the patient is malingering or suffers from a somatoform pain disorder (e17). This notion, however, has never been empirically tested. Up to 60% of all persons in the patient group that was the basis for the development of the FMS classifying criteria (8), as well as up to 60% of patients studied in outpatient rheumatology practices (e18), reported having tenderness at control points. The guideline therefore recommends that control points should not be tested, and that the diagnosis of FMS should not be rejected if patients say that they have "pain everywhere" while being examined (1).

Etiology, pathogenesis, and pathophysiology

Prospective, population-based studies have shown that physical and emotional stressors at the workplace and depressed mood are risk factors for the development of FMS. A variety of pathophysiological changes are associated with FMS without any clear causal relationship; among these are disturbances of central pain processing, hyporeactivity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, disturbances of the growth hormone system, elevated pro-inflammatory and low anti-inflammatory cytokine profiles, and changes in the dopaminergic and serotonergic systems (20).

Treatment

Telling the patient the diagnosis; patient education

It is recommended that the diagnosis of FMS should be communicated explicitly to the patient along with information about the treatment options (21). Important elements of the discussion with the patient at the time of initial diagnosis, as well as of patient education, are listed in Table 4. In addition to general information about the disease, patients should be made aware of any locally available literature for patients with fibromyalgia. In Germany, we tell our patients how to access the patient version of the German FMS guideline and inform them about the education programs of the German self-help associations (e19). In the United States, a very large amount of information for patients is available from the National Fibromyalgia Association (www.fmaware.org). Similar associations exist in Canada (www.fm-cfs.ca) and the United Kingdom (www.fibromyalgia-associationuk.org).

Table 4. Important things to tell the patient when FMS is initially diagnosed.

| The symptoms are permanent in most patients. |

| The symptoms do not lead to invalidism or shorten life expectancy. |

| Total relief of symptoms is not possible in most cases. |

| The goals of treatment are improvement and maintenance of the quality of life (functional ability in everyday situations) and reduction of symptoms. |

| Regular physical activity, such as cardiovascular exercise, contributes to symptom reduction and to improved adaptation to the symptoms. |

General principles of treatment

It is recommended that treatment should be consistent with the basic principles of psychosomatic care (patient-centered discussion), and that treatment decisions should be made jointly by the patient and the physician (shared decision-making) (21).

The patient and the physician should together set realistic goals for treatment. The choice of treatment should take both the patient’s preferences and the locally available treatment options into account. The utility of any treatment that is provided (benefits, side effects, cost) should be regularly evaluated.

Stratified treatment plan

Short-term treatment options (up to six months for pharmacotherapy, up to 24 months for a few non-pharmacological treatments) that are supported both by scientific evidence at the highest level and by recommendations at the highest level are listed in Table 5. On the basis of an expert consensus, a stratified treatment plan is recommended, corresponding to the stratified treatment recommendations for functional somatic syndromes (16) and the FMS treatment recommendations of the American Pain Society (e20) (box 3).

Table 5. Options for short-term treatment of the fibromyalgia syndrome (grade A recommendation based on grade 1a evidence).

| Treatment method | Literature search up to: | Number of randomized controlled trials | Quantitative analysis (meta-analysis) | Recommen-dation grade | Strength of consensus | Reference |

| Aerobic endurance training | June 2005 | 15 | Yes | A | Strong | (e23) |

| Antidepressants (amitriptyline)*1 | August 2008 | 8 | Yes | A | Strong | (e24) |

| Antidepressants*2 (duloxetine, fluoxetine, milnacipran, paroxetine) | August 2008 | 8 | Yes | B | Majority opinion | (e24) |

| Balneotherapy | July 2006 | 12 | No | A | Consensus | (e25) |

| Cognitive behavioral therapy | December 2006 | 14 | No | A | Strong | (23) |

| Multimodal therapy | December 2006 | 14 | Yes | A | Strong | (e26) |

| Pregabalin*3 | December 2008 | 5 | Yes | B | Majorityopinion | (e27) |

| Pool-based exercise | December 2006 | 8 | No | A | Consensus | (e28) |

*1 Amitriptyline is approved in Germany for the treatment of chronic pain in the framework of an overall therapeutic strategy.

*2 Lowering of the recommendation grade because of the lack of approval for FMS in Germany; duloxetine, fluoxetine, and paroxetine are approved in Germany for the treatment of depressive disorders, but not of FMS.

Milnacipran is not approved in Germany for the treatment of either depressive disorders or FMS.

Duloxetine has been denied approval for the treatment of FMS by the European Medicines Agency.

An application has been submitted to the European Medicines Agency for the approval of milnacipran for the treatment of FMS.

*3 Pregabalin is approved in Germany for the treatment of peripheral and central neuropathic pain, but not for the treatment of FMS.

Pregabalin has been denied approval for the treatment of FMS by the European Medicines Agency.

Box 3. Recommendations for the stratified treatment of fibromyalgia syndrome.

(The level of treatment and the therapeutic options should be chosen by shared decision-making of the patient and treating physician, in the light of the patient’s preferences and accompanying illnesses, if any.)

Level 1

Cognitive behavioral therapy and operant therapy for pain, including patient education (grade 1a evidence, grade A recommendation, strong consensus)

Aerobic endurance training adapted to the patient’s individual performance level (grade 1a evidence, grade A recommendation, strong consensus)

Pool-based exercise / aquatic jogging (grade 1a evidence, grade A recommendation, consensus)

Spa therapy (bathing in thermal springs) (grade 1a evidence, grade A recommendation, strong consensus)

Amitriptyline 25-50 mg/d (grade 1a evidence, grade A recommendation, strong consensus)

Diagnosis and treatment of comorbid physical and mental illnesses (grade 5 evidence, open recommendation, strong consensus)

Level 2

-

Multimodal treatment (requirement for medical training therapy or other type of activating movement therapy coordinated with psychotherapeutic methods) (grade 1a evidence, grade A recommendation, strong consensus)

Mainly outpatient; (partly) inpatient, when outpatient treatment is inadequate or impossible

(Pain therapy or psychosomatic medicine ward in an acute hospital, or else a rheumatological or psychosomatic rehabilitation center)

Level 3

Short-term: duloxetine 60–120 mg/d or fluoxetine 20–40 mg/d or milnacipran 100–200 mg/d or paroxetine 20–40 mg/d or pregabalin 150–300 mg/d (grade 1a evidence, grade B recommendation, majority opinion)

Short-term: hypnotherapy/directed imagery (grade 2b evidence, grade B recommendation, consensus) or therapeutic writing (grade 2b evidence, grade B recommendation, strong consensus)

Multimodal interval/booster therapy (grade 5 evidence, open recommendation, strong consensus)

Short-term: complementary therapeutic techniques (homeopathy, vegetarian diet) (grade 2b evidence, open recommendation, consensus)

Treatment should be provided if the patient suffers from major impairment in the activities of daily living. The choice of treatment level depends on the patient’s response to six months of treatment at the previous level. It is recommended that the effectiveness and potential side effects of the treatment provided should be continually monitored, and that a re-evaluation should take place at the end of treatment as well as six and twelve months later. If the treatment has not been sufficiently effective, a new diagnostic evaluation should be performed (reconsideration of the diagnosis of FMS and physical and mental comorbidities, negative effects of psychosocial stressors such as unemployment or desire for a pension).

Long-term care

The patient and physician should decide together on an individualized treatment program.

In long-term care, it is important to reinforce the patient’s assumption of individual responsibility and self-motivated activities (e.g., endurance training, application of heat by himself or herself).

The preferred forms of long-term treatment for FMS are those for which there is evidence of a persistent positive effect after the end of treatment: aerobic training (22), psychotherapy (cognitive and operant behavior therapy, hypnotherapy/directed imagery) (23), and multimodal therapy (a least one of the techniques of medical training therapy and psychotherapy) (24). The effectiveness of pharmacotherapy becomes evident after a maximum of three months for amitriptyline and six months for duloxetine, milnacipran, and pregabalin. Permanent pharmacotherapy can be considered if the current medication has been found to help the patient, if the patient desires to keep taking it, and perhaps if the symptoms became worse when the medication was discontinued on a trial basis (25). Withdrawal syndromes may occur after the discontinuation of antidepressants and pregabalin.

Discussion

This FMS guideline cannot resolve the current controversies surrounding the definition and classification of FMS. It also remains to be seen whether the classification of FMS will be affected by the way "medically unexplained somatic symptoms" are dealt with in the soon-to-be-published ICD-11 and DSM-V. The German guideline recommends symptom-based definition and clinical diagnosis of this symptom complex as an alternative to the ACR criteria. It also recommends a stratified treatment plan for FMS, which, unlike the EULAR recommendations (3), takes account of the special offerings of the German health care system, including outpatient functional training and inpatient multimodal therapy. In view of the multifarious interests of the various organizations that took part in the creation of the guideline (patients and caregivers, physicians and psychologists, family physicians and medical specialists, private practitioners and hospital-based physicians, doctors in acute hospitals and rehabilitation facilities), the degree of consensus reached for most of the recommendations was notably high. Unlike the guideline of the American Pain Society (e20) and the EULAR recommendations (3), the German guideline emphatically prescribes shared decision-making by the patient and the caregiver with regard to therapeutic options at all levels of treatment, and it mentions alternative and complementary techniques among the options on the third level of treatment. Furthermore, this guideline is the first one to include recommendations for long-term treatment. Unlike the recommendations of the German national care guidelines for coronary heart disease and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (e21, e22), these recommendations for long-term care were directed not just at primary-care physicians, but also at physicians from all of the specialties collaborating in the care of these patients. We plan to update the guideline recommendations (literature search and evaluation, creation of basic recommendations going beyond the health care system) in the future in collaboration with the American Pain Society.

Table 3. Indications for specialized psychotherapeutic evaluation in patients diagnosed with FMS (1).

| - The patient reports current, severe psychosocial stressors |

| - The patient reports current or earlier psychiatric treatment and/or use of psychotropic drugs |

| - The patient reports severe biographical stress factors (including traumatic stress factors) |

| - Evidence of maladaptive response to disease (e.g., catastrophizing, inappropriate self-protective or coping strategies) |

| - Patient’s beliefs about psychosomatic illness |

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by Ethan Taub, M.D.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

Dr. Häuser receives lecture honoraria from Eli Lilly, Janssen-Cilag, Mundipharma, and Pfizer, as well as consulting fees from Eli Lilly and Pfizer and reimbursement for travel expenses from Eli Lilly. Prof. Eich receives lecture honoraria from Pfizer and Eli Lilly and research funding from Ergonex. Prof. Nutzinger has received reimbursement of travel expenses from Eli Lilly. Prof. Schiltenwolf is a consultant for MSD and Pfizer. Professors Herrmann and Henningsen declare that they have no conflict of interest as defined by the guidelines of the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors.

References

- 1.Eich W, Häuser W, Friedel E, et al. Definition, Klassifikation und Diagnose des Fibromyalgiesyndroms. Schmerz. 2008;22:255–266. doi: 10.1007/s00482-008-0671-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Häuser W, Bernardy K, Arnold B. Das Fibromyalgiesyndrom - eine somatoforme Schmerzstörung? Schmerz. 2006;20:128–139. doi: 10.1007/s00482-005-0391-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carville SF, Arendt-Nielsen S, Bliddal H, et al. EULAR evidence based recommendations for the management of fibromyalgia syndrome. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67:536–541. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.071522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schiltenwolf M, Eich W, Schmale-Grete R, Häuser W. Ziele der Leitlinie zur Diagnostik und Therapie des Fibromyalgiesyndroms. Schmerz. 2008;22:241–224. doi: 10.1007/s00482-008-0669-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ollenschläger G, Kopp I, Lelgemann M, et al. Das Nationale Programm für Versorgungsleitlinien. Leitlinien für das Deutsche Disease Management Programm. Hintergrund, Methoden und Entwicklungsprozess. Med Klin. 2006;15:840–845. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoffmann J. Methodische Basis für die Entwicklung der Konsensusempfehlungen. Z Gastroenterol. 2004;42:984–987. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-813496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bernardy K, Klose P, Üçeyler N, Kopp I, Häuser W. Methodische Grundlagen der Leitlinienentwicklung. Methodenreport Schmerz. 2008;22:244–255. doi: 10.1007/s00482-008-0670-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wolfe F, Smythe HA, Yunus MB, et al. The American College of Rheumatology criteria for the classification of fibromyalgia: report of the multicenter criteria committee. Arthritis Rheum. 1990;33:160–172. doi: 10.1002/art.1780330203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Biewer W, Conrad I, Häuser W. Fibromyalgiesyndrom. Schmerz. 2004;18:118–124. doi: 10.1007/s00482-003-0300-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harth M, Nielson WR. The fibromyalgia tender points: use them or lose them? A brief review of the controversy. J Rheumatol. 2007;34:914–922. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wolfe F. Stop using the American College of Rheumatology criteria in the clinic. J Rheumatol. 2003;30:1671–1672. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gran JT. The epidemiology of chronic generalized musculoskeletal pain. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2003;17:547–561. doi: 10.1016/s1521-6942(03)00042-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clauw D, Crofford LJ. Chronic widespread pain and fibromyalgia: what we know and what we need to know. Best Pract Res Clin Rheum. 2003;17:685–701. doi: 10.1016/s1521-6942(03)00035-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wolfe F. The relation between tender points and fibromyalgia symptom variables: evidence that fibromyalgia is not a discrete disorder in the clinic. Ann Rheum Dis. 1997;56:268–271. doi: 10.1136/ard.56.4.268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Turk DC, Flor H. Primary fibromyalgia is greater than tender points: toward a multiaxial taxonomy. J Rheumatol. 1989;19:80–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Henningsen P, Zipfel S, Herzog W. Management of functional somatic syndromes. Lancet. 2007;369:946–955. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60159-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.World Health Organization. International Classification of Diseases Version 2007. www.who.int/classifications/apps/icd/icd10online/?gm70.htm+m797.

- 18.Häuser WC, Zimmer E, Felde E, Köllner V. Was sind die Kernsymptome des Fibromyalgiesyndroms? Umfrageergebnisse der Deutschen Fibromyalgievereinigung. Schmerz. 2008;22:176–183. doi: 10.1007/s00482-007-0602-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Henningsen P, Zimmermann T, Sattel H. Medically unexplained physical symptoms, anxiety, and depression: a meta-analytic review. Psychosom Med. 2003;65:528–533. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000075977.90337.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sommer C, Häuser W, Gerhold K, et al. Ätiopathogenese und Pathophysiologie des Fibromyalgiesyndroms und chronischer Schmerzen in mehreren Körperregionen. Schmerz. 2008;22:267–282. doi: 10.1007/s00482-008-0672-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klement A, Häuser W, Brückle W, et al. Allgemeine Behandlungsgrundsätze, Versorgungskoordination und Patientenschulung beim Fibromyalgiesyndrom und chronischen Schmerzen in mehreren Körperregionen. Schmerz. 2008;22:283–294. doi: 10.1007/s00482-008-0673-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schiltenwolf M, Häuser W, Felde E, et al. Physiotherapie, medizinische Trainingstherapie und physikalische Therapie beim Fibromyalgiesyndrom. Schmerz. 2008;22:303–312. doi: 10.1007/s00482-008-0675-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thieme K, Häuser W, Batra A, et al. Psychotherapie bei Patienten mit Fibromyalgiesyndrom. Schmerz. 2008;22:295–302. doi: 10.1007/s00482-008-0674-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arnold B, Häuser W, Bernardy K. Multimodale Therapie des Fibromyalgiesyndroms. Schmerz. 2008;22:334–338. doi: 10.1007/s00482-008-0678-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sommer C, Häuser W, Berliner M, et al. Medikamentöse Therapie des Fibromyalgiesyndroms. Schmerz. 2008;22:313–323. doi: 10.1007/s00482-008-0676-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e1.Berger A, Sadosky A, Dukes E, et al. Characteristics and patterns of health care utilization of patients with fibromyalgia in gerenal practicioner settings in Germany. Curr Med Res Opin. 2008;24:2489–2499. doi: 10.1185/03007990802316550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e2.Müller W, Stratz T. Ist die Fibromyalgie eine Krankheit? Pro. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2004;129 doi: 10.1055/s-2004-826871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e3.Vierck CJ., Jr Mechanisms underlying development of spatially distributed chronic pain (fibromyalgia) Pain. 2006;124:242–263. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e4.Gralow I. Ist die Fibromyalgie eine Krankheit? Contra. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2004;129 doi: 10.1055/s-2004-826872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e5.Raphael KG, Janal MN, Nayak S, Schwartz JE, Gallagher RM. Familial aggregation of depression in fibromyalgia: a community-based test of alternate hypotheses. Pain. 2006;110:449–460. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.04.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e6.Hadler NM. „Fibromyalgia“ and the medicalization of misery. J Rheumatol. 2003;30:1668–1670. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e7.Egle UT. Somatoforme Störungen - ein update. MMW Fortschr Med. 2005;147:4–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e8.Fietta P, Manganelli P. Fibromyalgia and psychiatric disorders. Acta Biomed. 2007;78:88–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e9.Sackett DL. Rules of evidence and clinical recommendations on use of antithrombotic agents. Chest. 1986;89(2 suppl):2–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e10.Hench PK. Nonarticular rheumatism. Rheumatism Reviews. 1976;22:1081–1088. [Google Scholar]

- e11.Smythe HA, Moldofsky H. Two contributions to understanding of the „fibrositis“ syndrome. Bull Rheum Dis. 1977;28:928–931. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e12.Yunus MB, Masi AT, Calabro JJ, Miller KA, Feigenbaum SL. Primary fibromyalgia (fibrositis): clinical study of 50 patients with matched normal controls. Semin Arthr Rheum. 1981;11:151–171. doi: 10.1016/0049-0172(81)90096-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e13.Müller W, Lautenschläger I. Die generalisierte Tendomyopathie (GTM) - Teil 1: Klinik, Verlauf und Differenzialdiagnose. Z Rheumatol. 1990;49:11–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e14.Van Houdenhove B, Luyten P. Stress, depression and fibromyalgia. Acta Neurol Belg. 2006;106:149–156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e15.Sauer N, Eich W. Somatoforme Störungen und Funktionsstörungen. Dtsch Arztebl. 2007;104:A 43–A 53. [Google Scholar]

- e16.Bennett RM, Jones J, Turk DC, Russell IJ, Matallana L. An internet survey of 2 569 people with fibromyalgia. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 2007;8 doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-8-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e17.Häntzschel H, Raspe HH. Fibromyalgiesyndrom. Diagnostische Kriterien. 1997 www.dgrh.de/qualitaetsmanual3_34.html. [Google Scholar]

- e18.Wolfe F. What use are fibromyalgia control points? J Rheumatol. 1998;25:546–550. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e19.Brückle W, Bornmann M, Webe H. Patientenschulung bei Fibromyalgie. Akt Rheumatol. 1997;22:92–97. [Google Scholar]

- e20.Burckhardt CS, Goldenberg D, Crofford L, Gerwin R, Gowans S, Kackson K, et al. Guideline for the management of fibromyalgia syndrome. Pain in adults and children. APS Clinical Practice Guideline Series No. 4. Glenview, IL: American Pain Society; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- e21.Bundesärztekammer, Kassenärztliche Bundesvereinigung und Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften. Nationale Versorgungsleitlinine chronisch obstruktive Lungenerkrankung. 2006. http://www.versorgungsleitlinien.de/themen/copd/nvl_copd/index_html.

- e22.Bundesärztekammer, Kassenärztliche Bundesvereinigung und Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften. Nationale Versorgungsleitlinine chronische koronare Herzerkrankung. 2007. http://www.versorgungsleitlinien.de/themen/khk/pdf/nvl_khk_kurz.pdf.

- e23.Busch AJ, Barber KAR, Overend TJ, Peloso PMJ, Schachter CL. Exercise for treating fibromyalgia syndrome (Cochrane Review) The Cochrane Library. 2007;(Issue 4) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003786.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e24.Häuser W, Bernardy K, Üceyler N, Sommer C. Treatment of fibromyalgia syndrome with antidepressants—a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2009;301:198–209. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e25.Mc Veigh JG, McGaughey H, Hall M, Kane P. The effectiveness of hydrotherapy in the management of fibromyalgia syndrome: a systematic review. Rheumatol Int. 2008;29:119–130. doi: 10.1007/s00296-008-0674-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e26.Häuser W, Bernardy K, Offenbächer M, Arnold B, Schiltenwolf M. Efficacy of multicomponent tretament of fibromyalgia syndrome—a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Arthr Rheum 61. 2009:216–224. doi: 10.1002/art.24276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e27.Häuser W, Bernardy K, Üceyler N, Sommer C. Treatment of fibromyalgia syndrome with pregabalin and gabapentin—a meta-analysis. Pain. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.05.014. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e28.Gowans S, deHueck A. Pool exercise for individuals with fibromyalgia. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2007;19:168–173. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e3280327944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]