Abstract

In the present study we sought to identify factors associated with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) following the World Trade Center Disaster (WTCD) and examine changes in PTSD status over time. Our data come from a two-wave, prospective cohort study of New York City adults who were living in the city on September 11, 2001. We conducted a baseline survey 1 year after the attacks (year 1), followed by a survey 1 year later (year 2). Overall, 2368 individuals completed the year 1 survey, and 1681 were interviewed at year 2. Analyses for year 1 indicated that being younger, being female, experiencing more WTCD events, reporting more traumatic events other than the WTCD, experiencing more negative life events, having low social support, and having low self-esteem increased the likelihood of PTSD. For year 2, being middle-aged, being Latino, experiencing more negative life events and traumas since the WTCD, and having low self-esteem increased the likelihood of PTSD. Exposure to WTCD events was not related to year 2 PTSD once other factors were controlled. Following previous research, we divided study respondents into four categories: resilient cases (no PTSD years 1 or 2), remitted cases (PTSD year 1 but not year 2), delayed cases (no PTSD year 1 but PTSD year 2), and acute cases (PTSD both years 1 and 2). Factors predicting changes in PTSD between year 1 and year 2 suggested that delayed PTSD cases were more likely to have been Latino, to have experienced more negative life events, and to have had a decline in self-esteem. In contrast, remitted cases experienced fewer negative life events and had an increase in self-esteem. We discuss these findings in light of the psychosocial context associated with community disasters and traumatic stress exposures.

Keywords: Posttraumatic stress disorder, delayed PTSD, disasters, psychosocial factors, stress exposure

It has been well documented that exposure to severe psychological trauma such as war, sexual assault, and community disasters can result in psychological and physical health problems (Boscarino, 1997; Bromet et al., 1982; Kessler et al., 1995b; Kulka et al., 1990; Norris, 1992). The inclusion of stress response syndromes in the DSM-III (American Psychiatric Association, 1980) under posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) has stimulated research and focused attention on what constitutes a traumatic event (McFarlane, 2004; Yehuda, 2002). It has also resulted in numerous etiological investigations of stress disorders (Adams et al., 2002; Brewin et al., 2000; Bromet et al., 1982; McFarlane, 1988; 1989), and has generated discussions of the consequences of PTSD for physical health and social role obligations (Boscarino, 2004; Kessler, 2000).

Recent studies examining PTSD in community samples have estimated that almost 90% of adults have experienced at least one lifetime traumatic event, yet only about 15% of those exposed developed PTSD (Breslau et al., 2004b; Breslau et al., 2005). Thus, factors beyond the traumatic event itself are required to explain the onset of these stress response syndromes (Adams and Boscarino, 2005; Boscarino, 1995; Galea et al., 2002; Kessler et al., 1995b). In particular, demographic characteristics such as age, gender, race, and socioeconomic status are associated with different rates of PTSD, with younger persons, women, Latinos, and low socioeconomic status individuals more likely to develop this stress disorder (Brewin et al., 2000; Bromet and Dew, 1995; Norris et al., 2002; Rubonis and Bickman 1991). Interpersonal and psychological characteristics of the individual, such as social support and self-esteem, have also been implicated in the onset and course of PTSD (Adams and Boscarino, 2005; Boscarino, 1995; Breslau et al., 2004b; Gray et al., 2004).

While researchers have assessed the prevalence of stress disorders in the general population, less attention has been focused on the social context of trauma exposures and how stressful events may have changed a person’s life circumstances (Adams et al., 2002; Norris et al., 2002). For example, the altered social environment of trauma survivors may contribute to the emergence or continuation of stress response syndromes. Recent studies, for example, have suggested that a significant proportion of the population may experience delayed PTSD, whereby individuals exposed to a traumatic event do not meet criteria at an initial assessment, but do meet criteria at a later point in time (Buckley et al., 1996; McFarlane, 2004; Prigerson et al., 2001). In a recent sample of 1040 Somalia Peacekeepers, researchers discovered that almost 7% were classified as delayed PTSD cases (Gray et al., 2004). That is, they did not meet the PTSD criteria 3 months after returning to the United States, but did about 12 months afterward. Interestingly, only about 2% of the sample was classified as in remission, because the Peacekeepers recovered sufficiently by the second assessment that they failed to meet criteria (Gray et al., 2004).

Few researchers, though, have concentrated on delayed PTSD in a community sample or explored events that may have occurred as a consequence of the earlier trauma. Such posttrauma events can be important for understanding delayed PTSD and other stress responses. Exposure to psychological trauma may intensify other negative events (e.g., job loss, divorce, and financial difficulties), which can increase stress disorders or maintain already existing disorders (Freedy et al., 1993). Studies conducted shortly after the September 11, 2001, World Trade Center Disaster (WTCD), revealed that 11% of those interviewed had a friend or relative killed during the attacks, about 4% lost possessions, and nearly 12% lost their job or had their work schedule reduced (Galea et al., 2002). These events themselves can lead to psychological distress, disruption of social relationships, and other psychosocial difficulties.

Studies of community disasters in general have left several problems unresolved. First, many study samples have been small and not generally representative of the affected community (Bromet and Dew, 1995), making generalization difficult. For example, one study used a registry of survivors from the Oklahoma City Bombing (North et al., 1999). Even though the sample was representative of the registry, the investigators noted that it overrepresented individuals who were close to the blast site and was not representative of Oklahoma City’s general population. Second, disaster researchers generally have not used standardized mental or physical health measures (Bromet and Dew, 1995). Third, many previous disaster studies have followed community residents for only a short period or have been cross-sectional (Boscarino et al., 2004b; Galea et al., 2002; North et al., 1999).

In the current study, we use two-wave panel data collected 1 and 2 years after the World Trade Center terrorist attacks to investigate demographic, social, and psychological factors related to PTSD after this community disaster. We extend previous work on stress response disorders by not only examining predictors of PTSD, but we also investigate possible reasons why some individuals developed PTSD more than a year after being exposed to this disaster. Thus, in the current study, we examine the psychosocial context of events related to the WTCD and how contextual factors might influence the course of PTSD.

METHODS

The data for the present study come from a two-wave panel study of English or Spanish speaking adults living in New York City (NYC) on the day of the WTCD. For year 1 (Y1), we conducted a telephone survey 1 year after the attacks, using random-digit dialing. When interviewers reached a person at a residential telephone number, they obtained verbal consent and then ascertained the area of residence. If more than one eligible adult lived in the household, interviewers selected the person with the most recent birthday. As part of the overall study, we oversampled residents who reported receiving any mental health treatment in the year after the attacks. The population was also stratified by the five NYC boroughs and gender, and sampled proportionately. Questionnaires were translated into Spanish and then back-translated by bilingual Americans to ensure the linguistic and cultural appropriateness. Y1 interviews occurred between October and December 2002.

For year 2 (Y2), we attempted to reinterview all Y1 participants 1 year later (i.e., 2 years after the WTCD). All Y2 interviews occurred between October 2003 and February 2004. The procedures were the same for both survey waves. Trained interviewers using a computer-assisted telephone interviewing system conducted the surveys and were supervised by the survey contractor in collaboration with the investigative staff. A protocol was in place to provide mental health assistance to participants who required psychiatric counseling. The mean duration of the interviews was about 45 minutes for Y1 and 35 minutes for Y2. Incentives of $10 and $20 were offered to Y1 and Y2 participants, respectively. The Institutional Review Board of the New York Academy of Medicine reviewed and approved the study’s protocols.

Overall, 2368 individuals completed the Y1 survey, and 1681 completed the Y2 survey. Approximately 7% of the interviews were conducted in Spanish for Y1 and 5% for Y2. Using industry standards (American Association for Public Opinion Research, 2000), the Y1 cooperation rate was approximately 63%, and the reinterview rate for Y2 was 71% (Adams et al., 2006). A sampling weight was developed for each wave to correct for potential selection bias related to the number of telephone numbers and persons per household and for the oversampling of treatment-seeking respondents. We also took into account the stratification of the population in our sampling design. In addition, demographic weights also were used for Y2 data in order adjust for slight differences in response rates by different demographic groups, a common practice in panel surveys (Kessler et al., 1995a). With these adjustments, both waves could be treated as a random, representative sample of NYC adults who were also living in NYC on the day of the WTCD (Adams et al., 2006).

PTSD and Delayed PTSD Assessment

Our PTSD scale was based on the DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association 1994). This measure was developed for telephone administration and used in previous national surveys (Kilpatrick et al., 2003; Resnick et al., 1993), as well as in other WTCD studies (Boscarino et al., 2004a; Galea et al., 2002). To meet PTSD criteria, a respondent had to be exposed to a traumatic event (criterion A1) and experience intense feelings of fear, helplessness, or horror (criterion A2). Second, the person had to re-experience the event in one of five ways (criterion B), avoid stimuli associated with the event in three of seven ways (criterion C), and have increased arousal in two of five ways (criterion D). Third, the symptoms for criteria B, C, and D had to last 1 month or longer (criterion E). Finally, the symptoms had to have an impact on the individual’s functional status (criterion F). Our assessment involved three sets of experiences, including the WTCD, the most stressful traumatic event experienced “other than the WTCD,” and any other traumatic event experienced. To have PTSD, the person had to meet criteria A through F for one or more of these traumatic events. Our Y1 and Y2 PTSD assessments covered the year prior to the date of interview. Results supporting the validity of our PTSD instrument have been reported elsewhere (Boscarino et al., 2004a, 2004b).

For our examination of delayed PTSD, we used the categories developed by Gray et al., (2004), which included resilient, remitted, delayed, and acute PTSD. Given that our respondents were living in NYC at the time of the attacks and could be considered at risk for PTSD, resilient cases were those who did not meet PTSD criteria for either Y1 or Y2. Remitted PTSD cases met criteria for Y1, but not for Y2, while those individuals categorized as delayed PTSD cases did not meet criteria for Y1, but met it for Y2. Acute PTSD cases met criteria at both Y1 and Y2 assessments.

Predictor Variables

In our analyses, we focused on factors that would predict PTSD at Y1 and at Y2 and would aid in the assessing changes in PTSD status. All of the demographic variables were based on Y1 data, unless the data were missing, in which case the Y2 data were substituted. In addition, unless otherwise noted, all variables were measured the same way for Y1 and Y2. Finally, all of the stress, risk, and resource variables come from Y1 for Y1 PTSD and Y2 for Y2 PTSD, except where noted.

Background Characteristics

Our analyses included four demographic variables: age, female gender, collage education, and race/ethnicity. Age was coded into four categories: 18 to 29, 30 to 44, 45 to 64, and 65+, with 65+ used as the reference category. Female gender and college education were coded as binary variables. Consistent with most research (Breslau et al., 2005), race/ethnicity was self identified. First, the survey interviewer asked the respondent if he/she was of Spanish or Hispanic origin. Next the respondent was queried about his/her race. Based on these two questions, we classified respondents as follows: non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black or African American, Hispanic, and other race/no race given, with white used as the reference group.

Stressor, Risk Factors, and Risk Moderators

Our statistical models included three stressors that could have placed individual at risk for PTSD, and two psychosocial resources that could lower such risk. The first stressor variable, WTCD event exposure, was based on the Y1 survey. This scale consisted of 14 possible events that the respondent could have experienced during the attacks. We summed these events and coded them, based on a frequency distribution, into low exposure (0–1 event), moderate exposure (2–3 events), high exposure (4–5 events), and very high exposure (6+ events), with low exposure used as the reference category. Second, a negative life event scale was the sum of eight experiences that the respondent could have had in the 12 months before the WTCD for Y1 (e.g., divorce, death of spouse, problems at work) and since the WTCD for Y2 (Freedy et al., 1993). Based on a frequency distribution, we coded each wave of respondents into three groups (no life events, one life event, and two or more life events), with no life events used as the reference category. The third stressor measure focused on 10 traumatic events (e.g., forced sexual contact, being attacked with a weapon) that could have occurred anytime prior to the Y1 survey (lifetime trauma) or in the year preceding the Y2 survey (past year trauma) (Freedy et al., 1993). For each wave, the traumatic events were coded into four categories, no traumas, 1 trauma, 2 to 3 traumas, and 4+ traumas, with no traumas used as the reference category.

The psychosocial resource variables included social support and self-esteem. Social support (Sherbourne and Steward, 1991) was the sum of four questions about emotional, informational, and instrumental support currently available to the respondent (e.g., someone available to help if you were confined to bed). Base on an examination of the scale’s frequency distribution, we coded respondents into low, moderate, and high social support categories. Self-esteem was measured by a modified version of the Rosenberg self-esteem scale (Rosenberg, 1979). This measure was the sum of five items in the original scale (e.g., on the whole, I am satisfied with myself) and coded into three groups, based on the frequency distribution: low, moderate, and high self-esteem. For these resource variables, high social support and high self-esteem were the reference categories. These stressor/risk and resource measures were used and validated in previous WTCD studies and discussed elsewhere (Boscarino et al., 2004a, 2004b; Galea et al., 2002).

To take into account psychological problems that could have existed prior to the WTCD, we assessed respondents for lifetime depression at Y1. Using a version of the SCID’s major depressive disorder scale from the nonpatients version (Spitzer et al., 1987), and consistent with the DSM-IV, respondents met criteria for lifetime depression if they ever had five or more depression symptoms for at least 2 weeks. This measure has been used in other telephone-based population surveys of trauma survivors (Acierno et al., 2000; Galea et al., 2002). Data related to the validity of this scale were previously reported and suggested that this scale can successfully diagnose depression in the general population (Boscarino et al., 2004a).

Statistical Analysis

Our analytic strategy proceeded in several steps. First, we discussed the descriptive statistics for our sample. Then, we assessed the bivariate association between our PTSD measure and the predictor variables. Finally, we estimated a series of multivariate logistic regression equations. Specifically, we regressed Y1 PTSD on all of the independent variables, except for lifetime depression (model 1). We then estimated a second equation that includes all of the other independent variables and lifetime depression (model 2). This regression sequence allowed us to assess how mental health problems that may have existed prior to Y1 may have influenced the associations between PTSD and the other variables. For the Y2 PTSD analyses, we first estimated an equation which contained the same independent variables as the Y1 PTSD, model 1 equation. Next, we added Y1 PTSD to the regression model. This equation assessed the change in PTSD between Y1 and Y2, rather than the likelihood of PTSD at one point in time. The final set of logistic regressions examined factors related to delayed PTSD, particularly negative life events and self-esteem. To assess key factors that might affect PTSD status, we also qualitatively assessed changes in PSTD overtime, as well the impact of key psychosocial factors on changes in PTSD status. For all of our analyses, we used the survey estimation (svy) command set in Stata, version 9 (Stata Corp, 2005). This estimation procedure adjusts the data for our sampling design, which included oversampling, stratification by city borough and gender and, as noted earlier, case weights.

RESULTS

We reported elsewhere our analysis comparing the weighted Y1 sample and census data for NYC (Adams et al., 2006). Essentially, the results indicated no differences for age, gender, race, or NYC borough. Thus, the Y1 sample appeared to be representative of NYC and was not demographically biased due to the cooperation rate or sample selection. When we compared responders for the Y2 sample to nonresponders, we found that whites, older respondents, and women more likely to participate in the Y2 survey, which is common for panel surveys (Kessler et al., 1995a). Consequently, we adjusted our Y2 data for these participation differences using sampling weights derived from Y1 data, which is the recommended method (Kessler et al., 1995a). These final adjusted results suggested that our Y2 results were representative of NYC adult population (Adams et al., 2006), and these weighted data are used in all of the analyses presented.

The distribution of respondents across the categories of predictor variables for Y1 is shown in Table 1 (column 2). The bivariate associations between Y1 PTSD and the predictor variables are also shown (column 3). As can be seen, there are associations between Y1 PTSD and gender, race/ethnicity, WTCD exposure, number of negative life events, number of lifetime traumatic events, social support, self-esteem, and lifetime depression. Only for age and education are these bivariate results not statistically significant. Columns 4 and 5 of Table 1 show results from our multivariate analysis. Model 1 indicates that younger respondents, women, very high WTCD exposure, high negative life event, high traumatic event, low social support, and low self-esteem respondents had an increased likelihood of Y1 PTSD. Interestingly, controlling for lifetime depression (model 2) did not alter these results, except for Y1 negative life events, which was no longer significant. These findings are similar to those reported for studies occurring shortly after the WTCD (Galea et al., 2002).

TABLE 1.

Weighted Percents, Logistic Regression Odds Ratio (OR), and 95% CI from Multivariate Prediction Models for Year 1 PTSD (N = 2323)

| Predictor Variables |

Total % (unweighted N) |

% Y1 With PTSD |

Adjusted OR (95% CI) Model 1 |

Adjusted OR (95% CI) Model 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||

| 18–29 | 27.2 (483) | 6.6 | 3.79 (1.4–10.6)* | 2.87 (1.1–7.8)* |

| 30–44 | 34.2 (866) | 4.9 | 1.99 (0.7–5.4) | 1.39 (0.5–3.6) |

| 45–64 | 28.7 (726) | 4.3 | 1.73 (0.6–4.8) | 1.27 (0.5–3.4) |

| 65+ (ref) | 9.8 (248) | 2.0 | 1.00 — | 1.00 — |

| Gender | ||||

| Male (ref) | 46.2 (1016) | 3.2** | 1.00 — | 1.00 — |

| Female | 53.8 (1352) | 6.2 | 2.78 (1.7–4.4)*** | 2.37 (1.4–3.9)*** |

| Race | ||||

| White (ref) | 39.2 (1015) | 4.1* | 1.00 — | |

| African American | 26.3 (606) | 5.5 | 0.85 (0.5–1.5) | 1.27 (0.7–2.4) |

| Latino | 25.7 (559) | 6.4 | 0.84 (0.5–1.5) | 1.20 (0.6–2.2) |

| Other | 8.7 (188) | 1.6 | 0.25 (0.1–0.6)** | 0.32 (0.1–0.8)* |

| Education | ||||

| Some college or less (ref) | 60.1 (1315) | 5.4 | 1.00 — | 1.00 — |

| College grad+ | 39.9 (1053) | 3.9 | 0.88 (0.6–1.4) | 0.90 (0.5–1.5) |

| Exposure to WTCD | ||||

| Low (0–1 events; ref) | 26.5 (510) | 3.6*** | 1.00 — | 1.00 — |

| Moderate (2–3 events) | 44.0 (1003) | 4.2 | 0.97 (0.5–1.9) | 0.90 (0.4–1.8) |

| High (4–5 events) | 22.0 (594) | 4.8 | 0.87 (0.4–1.7) | 0.66 (0.3–1.4) |

| Very high (6+ events) | 7.5 (261) | 12.9 | 2.71 (1.4–5.4)** | 2.21 (1.1–4.5)* |

| Y1 negative life events | ||||

| None (ref) | 56.2 (1197) | 2.5*** | 1.00 — | 1.00 — |

| One | 27.0 (642) | 5.2 | 1.50 (0.8–2.8) | 1.13 (0.6–2.2) |

| 2 or more | 16.8 (529) | 12.0 | 2.23 (1.2–4.2)* | 1.36 (0.7–2.6) |

| Y1 lifetime trauma | ||||

| 0 events (ref) | 33.0 (664) | 2.0*** | 1.00 — | 1.00 — |

| 1 event | 24.0 (588) | 2.6 | 1.27 (0.5–2.9) | 0.99 (0.4–2.4) |

| 2–3 events | 26.2 (667) | 6.2 | 3.34 (1.5–7.4)** | 2.74 (1.2–6.3)* |

| 4+ events | 16.8 (479) | 11.5 | 5.94 (2.7–13.1)*** | 3.73 (1.6–8.6)** |

| Y1 social support | ||||

| Low | 29.4 (668) | 6.5* | 1.85 (1.0–3.5)* | 2.04 (1.0–4.0)* |

| Moderate | 34.1 (825) | 4.7 | 1.29 (0.7–2.5) | 1.39 (0.4–2.8) |

| High (ref) | 36.5 (829) | 2.8 | 1.00 — | 1.00 — |

| Y1 self-esteem | ||||

| Low | 34.5 (890) | 9.4*** | 4.68 (2.5–8.7)*** | 2.83 (1.4–5.6)** |

| Moderate | 24.5 (573) | 3.7 | 1.90 (0.9–4.0) | 1.46 (0.7–3.2) |

| High (ref) | 40.9 (893) | 1.6 | 1.00 — | 1.00 — |

| Y1 lifetime depression | ||||

| No (ref) | 81.0 (1747) | 1.5*** | — | 1.00 — |

| Yes | 19.0 (621) | 18.9 | 9.25 (5.0–17.2)*** | |

| F statistic (df 1, df 2) | 8.19 (20, 2299)*** | 12.39 (21, 2298)*** |

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

p < 0.001.

The results for Y2 PTSD were somewhat different than seen for the Y1 PTSD (Table 2). The bivariate predictor results for Y2 PTSD indicated that age, race, exposure to the WTCD, Y2 negative life events, Y2 traumatic events, and Y2 self-esteem were related to this outcome (Table 2, column 3). In addition, as one would expect, Y1 PTSD was associated with Y2 PTSD. The multivariate analysis which included all of the predictors, except Y1 PTSD (model 1), suggested that middle-aged respondents, Latinos, those who experienced more negative life events and/or more traumatic events between Y1 and Y2, and those with low Y2 self-esteem were more likely to have Y2 PTSD. Including Y1 PTSD in our regression (model 2) did not alter these findings.

TABLE 2.

Weighted Percent, Logistic Regression Odds Ratio (OR), and 95% CI From Multivariate Prediction Models for Year 2 PTSD (N = 1681)

| Predictor Variables |

Total % (unweighted N) |

% Y2 With PTSD |

Adjusted OR (95% CI) Model 1 |

Adjusted OR (95% CI) Model 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||

| 18–29 | 22.7 (284) | 1.8*** | 3.66 (0.7–20.6) | 3.60 (0.6–20.5) |

| 30–44 | 32.9 (596) | 5.9 | 10.59 (2.3–48.9)** | 10.30 (2.2–48.0)** |

| 45–64 | 32.5 (586) | 4.4 | 10.86 (2.4–49.4)** | 11.00 (2.4–50.4)** |

| 65+ (ref) | 11.9 (215) | 0.3 | 1.00 — | 1.00 — |

| Gender | ||||

| Male (ref) | 46.2 (693) | 3.7 | 1.00 — | 1.00 — |

| Female | 53.8 (988) | 3.9 | 0.93 (0.5–1.7) | 0.87 (0.5–1.6) |

| Race | ||||

| White (ref) | 43.0 (782) | 2.9** | 1.00 — | 1.00 — |

| African American | 26.0 (422) | 2.5 | 1.00 (0.5–2.1) | 1.00 (0.5–2.1) |

| Latino | 24.1 (367) | 7.1 | 2.48 (1.1–5.5)* | 2.45 (1.1–5.4)* |

| Other/no race given | 7.0 (110) | 3.3 | 0.99 (0.3–3.3) | 1.04 (0.3–3.4) |

| Education | ||||

| Some college or less (ref) | 58.3 (906) | 3.7 | 1.00 — | 1.00 — |

| College graduate | 41.7 (755) | 4.0 | 1.41 (0.8–2.6) | 1.4 (0.8–2.7) |

| Exposure to WTCD | ||||

| Low (0–1 events; ref) | 26.7 (362) | 1.8*** | 1.00 — | 1.00 — |

| Moderate (2–3 events) | 43.9 (719) | 2.8 | 1.17 (0.5–2.8) | 1.11 (0.5–2.7) |

| High (4–5 events) | 21.8 (416) | 5.1 | 1.44 (0.5–4.0) | 1.39 (0.5–3.9) |

| Very high (6+ events) | 7.6 (184) | 13.1 | 2.41 (0.8–7.1) | 2.08 (0.7–6.2) |

| Y2 negative life events | ||||

| None (ref) | 50.2 (730) | 0.8*** | 1.00 — | 1.00 — |

| One | 28.2 (487) | 1.5 | 1.62 (0.6–4.4) | 1.62 (0.6–4.4) |

| 2 or more | 21.7 (464) | 13.7 | 9.98 (3.7–27.2)*** | 9.57 (3.5–26.0)*** |

| Y2 past year trauma | ||||

| 0 events (ref) | 85.0 (1390) | 2.7*** | 1.00 — | 1.00 — |

| 1 event | 9.3 (175) | 7.5 | 2.13 (1.0–4.6) | 1.99 (0.9–4.4) |

| 2–3 events | 4.8 (92) | 9.9 | 1.55 (0.6–4.1) | 1.42 (0.5–3.9) |

| 4+ events | 0.9 (24) | 39.8 | 6.64 (2.1–21.0)*** | 6.69 (2.1–21.0)*** |

| Y2 social support | ||||

| Low | 35.7 (596) | 5.1 | 0.79 (0.4–1.8) | 0.73 (0.3–1.7) |

| Moderate | 37.9 (659) | 2.7 | 0.59 (0.2–1.4) | 0.55 (0.2–1.3) |

| High (ref) | 26.4 (429) | 3.6 | 1.00 — | 1.00 — |

| Y2 self-esteem | ||||

| Low | 36.4 (633) | 7.5** | 3.54 (1.4–8.8)** | 3.56 (1.4–8.9)** |

| Moderate | 23.7 (408) | 2.5 | 1.53 (0.5–4.6) | 1.59 (0.5–4.7) |

| High (ref) | 40.0 (640) | 1.2 | 1.00 — | 1.00 — |

| Y1 PTSD | ||||

| No (ref) | 96.2 (1587) | 3.2*** | — | 1.00 — |

| Yes | 3.8 (94) | 17.7 | 2.47 (1.2–5.2)* | |

| F statistic (df 1, df 2) | 8.07 (20, 1657)*** | 8.33 (21, 1656)*** |

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

p < 0.001.

Comparing the results for Y1 and Y2 PTSD, it appears that age, negative life events, and traumatic events played a greater role in Y2 PTSD than Y1 PTSD. Gender and social support were significant predictors for Y1 PTSD, but not Y2 PTSD. Only for self-esteem were the associations similar for the two time-points. Most importantly, exposure to the WTCD was not related to Y2 PTSD once the other variables were controlled. To explore this further, we conducted additional analyses focusing on respondents whose diagnosis changed from Y1 to Y2. Based on previous research (Gray et al., 2004), we divided the respondents into resilient (N = 1495, 92.8%), remitted (N = 92; 3.3%), delayed (N = 66, 3.1%), and acute (N = 28, 0.7%) PTSD symptom groups. Due to the small number of respondents in all but the resilient group, we limited our predictor variables to those that had an association with these groups in preliminary analyses. When we contrasted delayed PTSD respondents with all other groups (Table 3, column 2), the results suggested that Latinos, those who experienced two or more negative life events between Y1 and Y2 and those with low self-esteem were more likely to exhibit delayed PTSD. The logistic regression model comparing delayed PTSD with individuals who did not have PTSD at either Y1 or Y2 (resilient cases) had the same results: Latinos, those with two or more negative life events at Y2, and those with low self-esteem at Y2 were more likely to be classified as delayed PTSD cases.

TABLE 3.

Multivariate OR Results and 95% CI for Delayed PTSD Compared With Other Symptom Groups Based on Logistic Regression Models

| Predictor Variables |

Delayed vs. All Others Adjusted OR 95% CI |

Delayed vs. Resilient Adjusted OR 95% CI |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||

| Male (ref) | 1.00 | — | 1.00 | — |

| Female | 0.81 | 0.42–1.54 | 0.90 | 0.46–1.74 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| Other (ref) | 1.00 | — | 1.00 | — |

| Latino | 2.10 | 1.06–4.15* | 2.24 | 1.11–4.51* |

| Exposure to WTCD | ||||

| Low (ref) | 1.00 | — | 1.00 | — |

| Medium | 1.15 | 0.44–3.04 | 1.19 | 0.45–3.14 |

| High | 1.53 | 0.52–4.42 | 1.54 | 0.52–4.60 |

| Very high | 2.12 | 0.64–7.01 | 2.64 | 0.78–8.86 |

| Y2 negative life events | ||||

| None (ref) | 1.00 | — | 1.00 | — |

| One | 1.37 | 0.45–4.17 | 1.35 | 0.44–4.16 |

| Two or more | 11.23 | 3.94–32.01*** | 12.26 | 4.27–35.24*** |

| Y2 self-esteem | ||||

| Low | 3.60 | 1.19–10.90* | 3.58 | 1.16–11.02* |

| Medium | 1.92 | 0.56–6.57 | 1.86 | 0.53–6.47 |

| High (ref) | 1.00 | — | 1.00 | — |

| N | 1681 | 1561 | ||

| F statistic (df 1, df 2) | 9.88 (9, 1668) | 10.65 (9, 1548) | ||

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

p < 0.001.

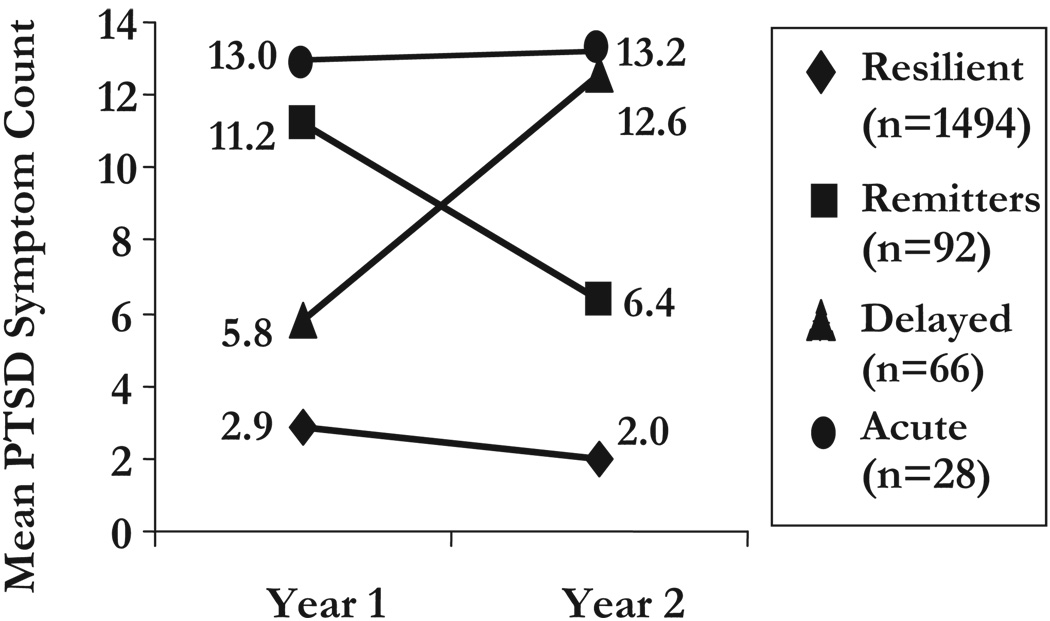

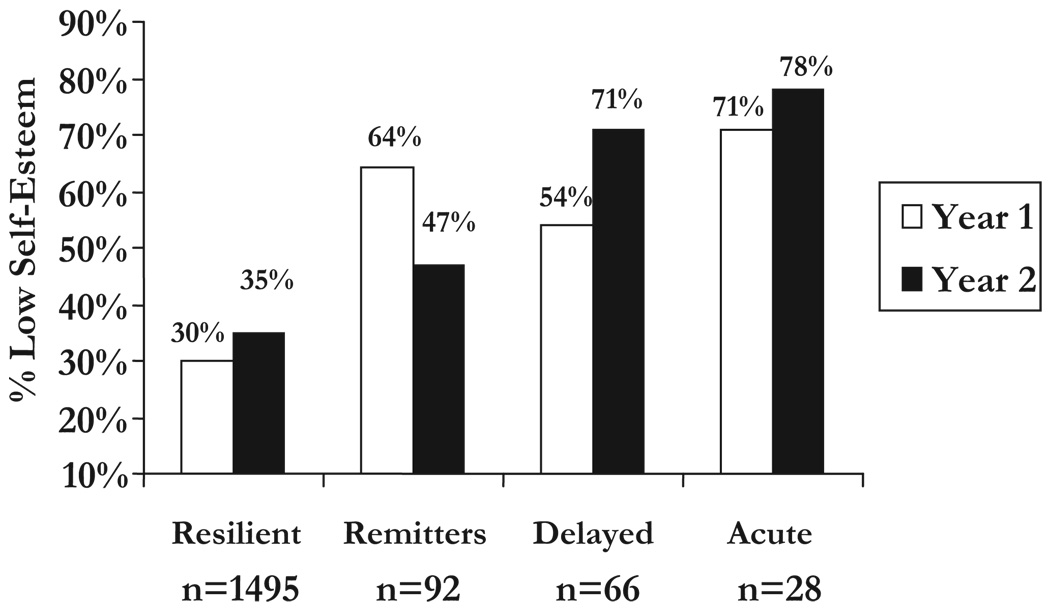

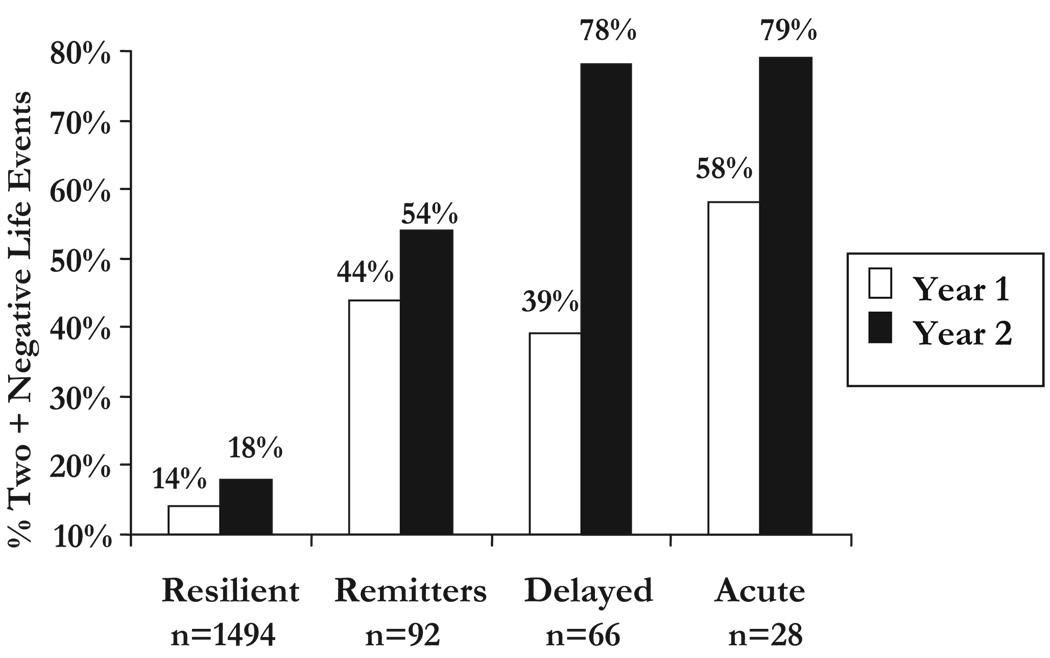

Changes in PTSD symptoms, negative life events, and self-esteem between Y1 and Y2 are presented in Figure 1 to Figure 3 by PTSD trajectory group. Similar to results reported previously (Gray et al., 2004), the number of PTSD symptoms for the remitted group decreased between Y1 and Y2, whereas they increased for the delayed PTSD group (Figure 1), as would be expected. Examination of reported negative life events in the year prior to the WTCD and in the 2 years post-WTCD, our data indicated that the percentage of respondents experiencing two or more negative life events increased in all symptom groups (Figure 2). However, individuals who were classified as having delayed-onset PTSD were much more likely to report two or more such events in Y2 relative to Y1 (Y1 = 39%, Y2 = 78%). In fact, about the same percentage of individuals classified as delayed PTSD reported two or more negative life events as those classified as acute PTSD. By comparison, the percentage of individuals classified as remitted cases who experienced two or more negative life events had a much smaller increase (Y1 = 44%, Y2 = 54%). Similarly, individuals exhibiting delayed PTSD had decreased self-esteem, with 54% scoring low on this for Y1 and 71% low for Y2 (Figure 3). Remitted PTSD cases revealed the opposite trend, with 64% low self-esteem for Y1 and 47% low for Y2. Finally, individuals in the resilient or acute categories showed less change in the percent reporting two or more negative life events or in the percent having low self-esteem. For both measures, resilient individuals reported fewer negative life events and had higher self-esteem, relative to all other symptom groups. In contrast, acute PTSD individuals experienced more negative life events and had lower self-esteem at both time points.

FIGURE 1.

Mean PTSD symptom count for year 1 and year 2 by symptom group.

FIGURE 3.

Percent of respondents having low self-esteem by symptom group.

FIGURE 2.

Percent of respondents reporting two or more negative life events by symptom group.

DISCUSSION

This study adds to the scientific literature examining stress response syndromes within the context of community disasters. Consistent with previous research (Bromet et al., 1998; Kessler et al., 1995b), we show that being 18–29, being female, experiencing more WTCD-related events, reporting low social support, and having low self-esteem were risk factors for the onset of Y1 PTSD, even after taking other stressful events into account. Two years after the attacks, however, younger age, gender, and social support were no longer related to PTSD. Instead, Latinos and respondents between 30 and 64 were at risk for PTSD, as well as those with low self-esteem, again controlling for other stressful events. Finally, our study documents a small but significant number of respondents who had increases in PTSD symptoms between 1 and 2 years post-WTCD, which also is consistent with previous research (Creamer et al., 2001; Gray et al., 2004; Orcutt et al., 2004).

However, our study went beyond prior studies and explored some of the reasons for delayed and remitted PTSD. Although each of these two symptom trajectory groups represent only 3% of the sample, they show that changes both in social circumstances and psychological resources are potential explanations as to why some persons had their PTSD symptoms remit, while others experienced delayed PTSD. More specifically, individuals with delayed PTSD reported experiencing more negative life events postdisaster and had a marked decline in self-esteem, whereas remitters reported fewer negative events and showed an increase in self-esteem during this same period. PTSD symptoms and symptom severity show a similar pattern, with delayed PTSD respondents becoming more symptomatic and experiencing the symptoms more severely, whereas remitted PTSD cases show significant improvement in these areas. In multivariate comparisons with other groups, those most at risk for delayed PTSD were Latinos, those who experienced more negative life events, and those with low self-esteem. It is noteworthy that the delayed-onset group was more like the resilient group at Y1 and more like the acute group at Y2, while, again, the opposite was observed in the remission group. Thus, as has been previously noted (Gray et al., 2004), changes in these diagnostic categories may not be due to minor fluctuations in PTSD symptomatology per se.

Even though DSM-IV included delayed PTSD, theoretical and conceptual work on it has lagged in the larger discussion of causes and consequences of PTSD. From a measurement error perspective, changes in diagnosis may be due to an underreporting of symptoms at the initial assessment or an overreporting of symptoms at later assessments for delayed PTSD and the opposite for remitted PTSD cases. It has also been speculated that delayed PTSD may result from classical conditioning for fear and anxiety responses to trauma cues, reinforcing avoidance and re-experiencing symptoms (Gray et al., 2004). Finally, and in line with our findings, changes in diagnosis may reflect changes in trauma survivors’ psychosocial circumstances, whereby exposure to negative life events and/or events leading to lower self-esteem may result in increased PTSD symptom reporting.

Additional research on individuals who do not meet full PTSD criteria but nevertheless have many PTSD symptoms may also provide insight into the course of postdisaster stress response disorders. Referred to as partial (Breslau et al., 2004a) or subsyndromal PTSD (Galea et al., 2003), these classifications typically require individuals to have a certain number of symptoms from criteria B, C, and D (re-experiencing, avoidance, and arousal). These designations are not without controversy in that they do not adhere to DSM-IV criteria. On the other hand, Breslau et al. (2004a) note that individuals meeting criteria for partial PTSD have some impairment in work and social interaction domains, although not nearly the level of impairment exhibited by persons meeting the full criteria. Thus, examining how changes in social circumstances relate to changes in the number and severity of symptoms for individuals not meeting full criteria may further illuminate factors underlying delayed PTSD. The main point, though, is that more detailed research on the postdisaster environment is strongly supported by our study.

The question that remains unanswered is why some individuals experience more negative life events and diminished self-esteem in the postdisaster period. Some investigators contend that the postdisaster period can be characterized by an adverse social environment, defined as “a consistent pattern of chronic [negative] impacts to individuals and communities” (Picou et al., 2004, p. 1496). In other words, if the social environment is more conflict prone, as indicated by transportation problems, litigation, social conflicts, disruption of living arrangements, and the breakdown of public service agencies, then mental disorders will likely increase. In their study of the economic and social consequences of the Exxon Valdez oil spill into the Prince William Sound, Palinkas et al. (1993a, 1993b) noted that this environmental disaster was not particularly life-threatening. Nevertheless, the oil spill and subsequent clean-up disrupted subsistence food production (e.g., fishing), strained family and community relations, and increased social inequality. Individuals living in communities most affected by these social and interpersonal changes also reported more depressive, PTSD, and anxiety symptoms compared with those living in less affected communities. Clearly, research is needed to understand better how disasters disrupt familial and community support systems and may alienate victims from local institutions and increase PTSD symptoms.

As with any study, ours has limitations and strengths. First, we omitted individuals without telephones, those who did not speak English or Spanish, and those too disabled to undertake a survey or institutionalized. Given that the sample matched the 2000 census for NYC, elimination of these persons did not appear to introduce overall demographic bias. We are limited, though, in generalizing these findings beyond white, African American, and Latino groups. To date, little research has focused on how the World Trade Center attacks affected the physical or mental health of immigrant communities or the wide variety of ethnic groups living in NYC. It is possible that individuals in these communities may have suffered greater psychological problems due to fewer economic resources and greater job instability (Thiel de Bocanegra and Brickman, 2004). There may also be cultural differences in the desirability of reporting psychiatric symptoms that could affect the ethnicity-PTSD relationship (Norris et al., 2001), which we did not explore. We also did not have predisaster data, with much of our data being based on retrospective measures. Although we included lifetime depression to partially account for predisaster psychological problems, we did not have data on other difficulties such as anxiety or personality disorders. Additionally, our mental health measures were based on self-report. Although there has been significant progress in assessing individual mental health with standardized instruments administered by interviewers (Adams et al., 2002; Kessler et al., 1995b), there continue to be discrepancies between lay and clinician-based assessments within community population samples. The strengths of our study include the use of a large random sample representative of NYC, the assessment of physical and mental well-being using standard scales and measurements, the focus on a specific time-bound event that meets criteria for community-wide disaster, and a focus on common postdisaster problems faced by survivors.

Community disasters can have a significant impact on the well-being of survivors (Bromet and Dew 1995). As with all environmental challenges faced by individuals, the degree of exposure to adverse events and the amount of change in personal circumstances can have long-lasting impact on psychological well-being. With regard to the WTCD, further research is needed to determine whether these are transient changes affecting psychological well-being or reflect larger changes in the psychosocial environment of disaster survivors.

Acknowledgments

Supported by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (grant #R01 MH66403) to Dr. Boscarino.

REFERENCES

- Acierno R, Kilpatrick DG, Resnick H, Saunders B, De Arellano M, Best C. Assault, PTSD, family substance use and depression as risk factors for cigarette use in youth: Findings from the National Survey of Adolescents. J Trauma Stress. 2000;13:381–396. doi: 10.1023/A:1007772905696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams RE, Boscarino JA. Stress and well-being in the aftermath of the World Trade Center attack: The continuing effects of a communitywide disaster. J Commun Psychol. 2005;33:175–190. doi: 10.1002/jcop.20030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams RE, Boscarino JA, Galea S. Social and psychological resources and health outcomes after World Trade Center disaster. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62:176–188. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams RE, Bromet EJ, Panina N, Golovakha E, Goldgaber D, Gluzman S. Stress and well-being after the Chornobyl nuclear power plant accident. Psychol Med. 2002;32:143–156. doi: 10.1017/s0033291701004676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Association for Public Opinion Research. Standard Definitions: Final Dispositions of Case Codes and Outcomes Rates for Surveys. Ann Arbor (MI): American Association for Public Opinion Research; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 3rd ed. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Boscarino JA. Post-traumatic stress and associated disorders among Vietnam veterans: The significance of combat exposure and social support. J Trauma Stress. 1995;8:317–336. doi: 10.1007/BF02109567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boscarino JA. Diseases among men 20 years after exposure to severe stress: Implications for clinical research and medical care. Psychosom Med. 1997;59:605–614. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199711000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boscarino JA. Association between posttraumatic stress disorder and physical illness: Results and implications from clinical and epidemiologic studies. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1032:141–153. doi: 10.1196/annals.1314.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boscarino JA, Adams RE, Figley CR. Mental health service use 1-year after the World Trade Center disaster: Implications for mental health care. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2004a;26:346–358. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2004.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boscarino JA, Galea S, Adams RE, Ahern J, Resnick H, Vlahov D. Mental health service and psychiatric medication use following the terrorist attacks in New York City. Psychiatr Serv. 2004b;55:274–283. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.55.3.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau J, Kendler KS, Su M, Gaxiola-Aguilar S, Kessler RC. Lifetime risk and persistence of psychiatric disorders across ethnic groups in the United States. Psychol Med. 2005;35:317–327. doi: 10.1017/s0033291704003514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau N, Lucia VC, Davis GC. Partial PTSD versus full PTSD: an empirical examination of associated impairment. Psychol Med. 2004a;34:1205–1214. doi: 10.1017/s0033291704002594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau N, Peterson EL, Schultz LR, Lucia VC. Estimating posttraumatic stress disorder in the community: Lifetime perspective and the impact of typical traumatic events. Psychol Med. 2004b;34:889–898. doi: 10.1017/s0033291703001612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewin CR, Andrews B, Valentine JD. Meta-analysis of risk factors for posttraumatic stress disorder in trauma-exposed adults. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68:748–766. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.5.748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bromet EJ, Dew MA. Review of psychiatric epidemiologic research on disasters. Epidemiol Rev. 1995;17:113–119. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a036166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bromet EJ, Parkinson DK, Schulberg HC, Dunn LO, Gondek PC. Mental health of residents near the Three Mile Island reactor: A comparative study of selected groups. J Prev Psychiatry. 1982;1:225–276. [Google Scholar]

- Bromet EJ, Sonnega A, Kessler RC. Risk factors for DSM-III-R posttraumatic stress disorder: Findings from the National Comorbidity Survey. Am J Epidemiol. 1998;147:353–361. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckley TC, Blanchard DB, Hickling EJ. A prospective examination of delayed onset PTSD secondary to motor vehicle accidents. J Abnorm Psychol. 1996;105:617–625. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.105.4.617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creamer M, Burgess P, McFarlane AC. Post-traumatic stress disorder: findings from the Australian National Survey of Mental Health and Well-being. Psychol Med. 2001;31:1237–1247. doi: 10.1017/s0033291701004287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedy JR, Kilpatrick DG, Resnick HS. Natural disasters and mental health: Theory, assessment and intervention. J Soc Behav Pers. 1993;8:49–103. [Google Scholar]

- Galea S, Ahern J, Resnick H, Kilpatrick D, Bucuvalas M, Gold J, Vlahov D. Psychological sequelae of the September 11 terrorist attacks in New York City. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:982–987. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa013404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galea S, Vlahov D, Resnick H, Ahern J, Susser E, Gold J, Bucuvalas M, Kilpatrick D. Trends of probable post-traumatic stress disorder in New York City after the September 11 terrorist attacks. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;158:514–524. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray MJ, Bolton EE, Litz BT. A longitudinal analysis of PTSD symptom course: Delayed-onset PTSD in Somalia Peacekeepers. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004;72:909–913. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.5.909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC. Posttraumatic stress disorder: The burden to the individual and to society. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000;61 suppl 5:4–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Little RJ, Groves RM. Advances in strategies for minimizing and adjusting for survey nonresponse. Epidemiol Rev. 1995a;17:192–204. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a036176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, Hughes H. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the national comorbidity survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1995b;52:1048–1060. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950240066012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick DG, Ruggiero KJ, Acierno R, Saunders BE, Resnick HS, Best CL. Violence and risk of PTSD, major depression, substance abuse/dependence and comorbidity: Results from the national survey of adolescents. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2003;71:692–700. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.4.692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulka RA, Schlenger WE, Fairbank JA, Hough RL, Jordan BK, Marmar CR, Weiss DS. Trauma and the Vietnam War Generation: Report of the Findings from the National Vietnam Veterans Readjustment Study. New York: Brunner/Mazel; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- McFarlane AC. Aetiology of post-traumatic stress disorders following a natural disaster. Br J Psychiatry. 1988;152:116–121. doi: 10.1192/bjp.152.1.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarlane AC. The aetiology of post-traumatic morbidity: Predisposing, precipitating and perpetuating factors. Br J Psychiatry. 1989;154:221–228. doi: 10.1192/bjp.154.2.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarlane A. The contribution of epidemiology to the study of traumatic stress. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2004;39:874–882. doi: 10.1007/s00127-004-0870-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris FH. Epidemiology of trauma: Frequency and impact of different potentially traumatic events on different demographic groups. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1992;60:409–418. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.60.3.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris FH, Friedman MJ, Watson PJ, Byrne CM, Diaz E, Kaniasty K. 60,000 Disaster victims speak, part I: An empirical review of the empirical literature, 1981–2001. Psychiatry. 2002;65:207–239. doi: 10.1521/psyc.65.3.207.20173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris FH, Perilla JL, Murphy AD. Postdisaster stress in the United States and Mexico: a cross-cultural test of the multicriterion conceptual model of posttraumatic stress disorder. J Abnorm Psychol. 2001;110:553–563. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.110.4.553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- North CS, Nixon SJ, Shariat S, Mallonee S, McMillen JC, Spitznagel EL, Smith EM. Psychiatric disorders among survivors of the Oklahoma City bombing. JAMA. 1999;282:755–762. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.8.755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orcutt HK, Erickson DJ, Wolfe J. The course of PTSD symptoms among Gulf War Veterans: A growth mixture modeling approach. J Trauma Stress. 2004;17:195–202. doi: 10.1023/B:JOTS.0000029262.42865.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palinkas LA, Downs MA, Petterson JS, Russell J. Social, cultural and psychological impacts of the Exxon Valdez oil spill. Hum Organiz. 1993a;52:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Palinkas LA, Petterson JS, Russell J, Downs MA. Community patterns of psychiatric disorder after the Exxon Valdez oil spill. Am J Psychiatry. 1993b;150:1517–1523. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.10.1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picou JS, Marshall BK, Gill DA. Disaster, litigation and the corrosive community. Soc Forces. 2004;82:1493–1522. [Google Scholar]

- Prigerson HG, Maciejewski PK, Rosenheck RA. Combat trauma: trauma with highest risk of delayed onset and unresolved posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms, unemployment and abuse among men. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2001;189:99–108. doi: 10.1097/00005053-200102000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnick HS, Kilpatrick DG, Dansky BS, Saunders BE, Best CL. Prevalence of civilian trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder in a representative national sample of women. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1993;61:984–991. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.61.6.984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg M. Conceiving the Self. New York: Basic Books; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Rubonis AV, Bickman L. Psychological impairment in the wake of disaster: The disaster-psychopathology relationship. Psychol Bull. 1991;109:384–399. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.109.3.384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherbourne CD, Stewart AL. The MOS social support survey. Soc Sci Med. 1991;32:705–714. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90150-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Gibbon M. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R: Non-Patient Version. New York: Biometrics Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Stata Corporation. Stata (version 9.0) College Station (TX): Stata Corp.; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Thiel de Bocanegra H, Brickman E. Mental health impact of the World Trade Center attacks on displaced Chinese workers. J Trauma Stress. 2004;17:55–62. doi: 10.1023/B:JOTS.0000014677.20261.dd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yehuda R. Post-traumatic stress disorder. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:108–114. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra012941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]