Abstract

Relations among parental depressive symptoms, overt and covert marital conflict, and child internalizing and externalizing symptoms were examined in a community sample of 235 couples and their children. Families were assessed once yearly for three years, starting when children were in kindergarten. Parents completed measures of depressive symptoms and children’s internalizing and externalizing symptoms. Behavioral observations of marital conflict behaviors (insult, threat, pursuit, and defensiveness) and self-report of covert negativity (feeling worry, sorry, worthless, and helpless) were assessed based on problem solving interactions. Results indicated that fathers’ greater covert negativity and mothers’ overt destructive conflict behaviors served as intervening variables in the link between fathers’ depressive symptoms and child internalizing symptoms, with modest support for the pathway through fathers’ covert negativity found even after controlling for earlier levels of constructs. These findings support the role of marital conflict in the impact of fathers’ depressive symptoms on child internalizing symptoms.

Keywords: Depression, Marital Conflict, Internalizing, Externalizing, Father-child relations

Depressive symptoms are common in parents of young children (Brown & Harris, 1978), and implications for children’s development can be significant. For example, children of depressed parents are at increased risk for internalizing symptoms, such as depression and anxiety, and externalizing symptoms, such as aggression and delinquency (Martins & Gaffan, 2000; Murray, Fiori-Cowley, Hooper & Cooper, 1996; Weissman, Warner, Wickramaratne, Moreau, & Olfson, 1997). Although the transmission of effects between parental dysphoria and children’s internalizing and externalizing symptoms may reflect, in part, genetic influence, the consensus is that environmental and family influences also contribute to risk for behavior problems (Hops, 1996). The focus of the current study is on one family factor in the relation between parental depressive symptoms and children’s internalizing and externalizing symptoms: marital dysfunction.

Current research and theory on the effects of parental depressive symptoms on child development implicates marital dysfunction as a mechanism of risk. Cummings and Davies (1994) proposed that depressive symptoms may prevent couples from resolving marital conflict, undermining children’s sense of security about the family. Downey and Coyne (1990) also suggested that relations between depressive symptoms and marital discord may be bidirectional, and that both depressive symptoms and associated marital problems may together contribute to the development of internalizing and externalizing symptoms in children. Empirical evidence also supports marital discord as a pathway of risk in the context of parental depressive symptoms. Relations between depression and marital problems are repeatedly demonstrated (Joiner & Coyne, 1999), and longitudinal analyses indicate relations are bidirectional (e.g., Whisman, 2001). Furthermore, studies also show that marital conflict mediates the relation between parental depressive symptoms and children’s internalizing and externalizing symptoms (Davies & Windle, 1997; Davis, Sheeber, Hops & Tildesley, 2000; Du Rocher Schudlich & Cummings, 2003). For example, Cummings, Keller and Davies (2005) found that marital hostility and insecure marital attachment partially mediated relations between mother and paternal depressive symptoms and parents’ reports of kindergarteners’ internalizing, externalizing and social problems.

The present manuscript further examines how marital conflict in the context of parental depressive symptoms is related to children’s internalizing and externalizing symptoms exhibited in the family setting. Conflict tactics such as defensiveness, threat, personal insult, and pursuit/withdrawal of conflict are consistently associated with children’s adverse reactions and are also linked to parental depressive symptoms (Cummings, Goeke-Morey, & Papp, 2003; Goeke-Morey, Cummings, Harold, & Shelton, 2003; Gottman, 1994; Gottman 1999). Relatively subtle aspects of marital conflict, including covert emotions related to beliefs about the self and relationship, may also relate to children’s risk for internalizing and externalizing symptoms (Levenson & Gottman, 1983). Families may develop a shared understanding of each other’s emotions that make them more sensitive to each other’s feelings than an outside observer. Accordingly, children may develop sensitivity to parents’ covert emotions and beliefs (e.g., hopelessness), influencing the development of children’s internalizing and externalizing symptoms.

Cognitively based theories of depression suggest that depressed individuals suffer from negative schemas that lead to negative interpersonal attributions (Beck, Rush, Shaw & Emery, 1979), and that they may engage in excessive reassurance seeking that causes frustration and rejection in relationships (Coyne 1976; see also Joiner & Coyne, 1999). For example, depression has been linked to defensiveness, hostility, aggression, insult, threat, avoidance and withdrawal in interpersonal relations (Byrne, Carr & Clark, 2004; DeFife & Hilsenroth, 2005; Felsten, 1996), including marital conflict (e.g., Byrne et al., 2004; Coyne, Thompson, & Palmer, 2002). From a theoretical perspective, these behaviors may be the result of negative attributions in which the depressed individual perceives attack or rejection, or may be the result of frustration with the inability to adequately resolve conflict.

Other covert responding linked with depression that may occur during conflict includes feelings of worry (Chelminski & Zimmerman, 2003), helplessness (Ozment & Lester, 1998), worthlessness (Lynch, Compton, Mendelson, Robins & Krishnan, 2000) and shame or guilt (Shahar, 2001). Depressed wives experience greater self-blame and increased feelings of hopelessness following a problem-solving task with their spouses than non-depressed wives (Sayers, Kohn, Fresco, Bellack & Sarwer, 2001). These feelings of helplessness, worthlessness, and shame are linked with theorized psychological processes involved in depression, such as the feelings of frustration and rejection they experience and elicit in relationships, and possible negative attributions of self-blame.

Despite the theoretical and empirical evidence for overt conflict behaviors (e.g., insult, defensiveness, and threat) and covert responding during conflict (e.g., worry, helplessness, shame) in the context of depressive symptoms, few studies have examined how these dimensions of conflict might serve as a pathway of risk for children. The current study addresses gaps in the literature in two important ways. First, this study focuses on overt and covert aspects of conflict that have been implicated in previous research. Specifically, couples’ use of pursuit, defensiveness, and hostile behaviors such as threat and insult will be examined. In addition, the current study is novel because it takes into account covert aspects of disagreements that may be especially pertinent to depression, such as worry, worthlessness, helplessness, and feeling sorry for one’s partner. The simultaneous consideration of overt and covert experiences is advantageous for advancing how depressive symptoms relate to multiple aspects of marital conflict and determining which aspects of marital conflict in these family contexts contribute to children’s risk for internalizing and externalizing symptoms.

Second, this study advances study of the effects of fathers’ depressive symptoms, consistent with a growing body of theory and research emphasizing the role of fathers in children’s development (Lamb, 2004; Phares, 1996, 1999). However, there is a paucity of studies examining the impact of men’s depressive symptoms on children (Phares, Duhig & Watkins, 2002). A recent meta-analysis indicated that fathers’ depressive symptoms are related to greater father-child conflict, and greater internalizing and externalizing symptoms in children (Kane & Garber, 2004). Moreover, there is a particular need for research to consider fathers’ influence separately from mothers’ (Phares, Lopez, Fields, Kamboukos, & Duhig, 2005). Thus, mother and paternal depressive symptoms will be examined separately.

This study focused on children between the ages of 5 and 8 years, when children develop improved understanding and increased concern about family functioning (Cicchetti, Cummings, Greenberg, & Marvin, 1990). In making the transition into school, they are also faced with a diverse and complex set of social and cognitive challenges, possibly contributing to the initial emergence of internalizing and externalizing symptoms (Chase-Lansdale, Wakschlag & Brooks-Gunn, 1995). Finally, individuals fluctuate between higher and lower symptoms levels over time (Fava & Mangelli, 2001), and there is increasing support for dimensional approaches to the assessment of psychopathology (Krueger, Watson, & Barlow, 2005). Given these points, this study focuses on depressive symptoms as a continuum of disorder.

In summary, this study advances previous research by considering the overt and covert aspects of marital conflict associated with mothers’ and fathers’ depressive symptoms, and how these family processes relate to children’s internalizing and externalizing symptoms exhibited in the family context. It is hypothesized that parental depressive symptoms will be related to both increased overt parental destructive behaviors and increased parental covert negativity during marital disagreements one year later, and that these conflict characteristics will be associated with increased internalizing and externalizing symptoms in children at the final time point. In testing these hypotheses, the current study employs a longitudinal design, controlling for earlier levels of children’s symptoms. Longitudinal studies demonstrating that putative risk factors precede child adjustment and predict them, after controlling for earlier levels of outcomes advance understanding of the causal nature of relations.

Method

Participants

Participants are from a community sample of families living in two small cities in the U.S. and their surrounding areas, taking part in a larger study. Families were recruited through schools, postcards, flyers, booths at community functions, and referrals from other participants. In order to obtain a socioeconomically diverse sample, targeted efforts were made to actively recruit participants through school districts, community agencies, and events tailored to families of low socioeconomic status and of racial and ethnic diversity. Families were eligible to participate if they had been living together for at least three years, had a child currently enrolled in kindergarten, and were able to complete questionnaires in English. One participating family was excluded from analyses because the parents were not in a stable relationship. The remaining sample from the first wave of data collection consisted of 235 families. Forty-five percent of the children were boys. Mean age at the first assessment was 6.0 years (SD = 5 months).

The majority of couples were married (88.1%). Couples had been living together an average of 11 years. Although not all couples were married, we use the term “marital conflict” for the sake of simplicity. No significant differences were observed between married and nonmarried couples on any measure of marital conflict. Approximately 95% of female parents and 88% of male parents were the participating children’s biological parents. For ease of discussion, all male and female parents will be referred to as mothers and fathers. For the sample as a whole, the majority of participants were European American (76.5%); 16.7% were African American, 3.8% were Hispanic, 2.1% were “other” race or biracial. Although there were some couples in which partners were of a different race and children were considered biracial, this number was too small to be considered in analyses. Total family income ranged from less than $6,000 a year (n = 3 families) to more than $75,000 a year (n = 50 families), with the median income between $40,000 and $54,999. Participants averaged about 14 years of education.

Data were collected over three annually-spaced waves. This study had high retention rates: Of the original 235 families, 227 (97%) participated in wave two and 215 (91%) participated in wave three. Reasons for attrition included divorce, hectic schedules, family medical problems, disinterest, inability to contact, and unknown reasons. Comparisons on demographic variables indicated that dropped families were not significantly different from retained families in terms of age, time living together, race or marital status. However, families who did not participate in later waves tended to have lower incomes and included less educated mothers and fathers (effect sizes were in the d = .7–.8 range). Comparisons also revealed no significant differences on measures of parental dysphoria, marital conflict, or child functioning.

Procedures

This study was conducted under the oversight of the Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) at both data collection sites; all procedures and consent and assent forms were approved by the IRBs before the study began. Data were collected annually over the course of three years, beginning when children were in kindergarten. Parents and children attended two laboratory sessions at each time point, during which they completed a variety of measures

Problem-solving discussions

In the first and second waves of data collection, following a brief introduction, parents were asked to separately identify three topics on which they frequently disagree and have a difficult time handling. Then parents were asked to choose one topic from each person’s list that both were comfortable discussing. Once two topics had been chosen, couples were asked to discuss a specific issue within the topic and attempt to work towards a solution. Couples were videotaped discussing each topic for ten minutes. Following each discussion, the experimenter asked the couple to separate and complete a post-interaction questionnaire that included self-ratings of emotions during the discussion. Although the timing of reports may not be optimal, interrupting interactions to obtain reports and then resuming the interaction seems likely to alter the emotional experience of couples and limit the external validity of the data. Similarly, asking couples to watch videos of their interaction and report of their feelings relies on potentially inaccurate memory and may be influenced by interceding events. We therefore judged the current approach to be the most appropriate for assessing the covert dimensions of marital interactions.

Measures

Parental depressive symptoms

Mothers’ and fathers’ depressive symptoms were assessed using self-report on the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977) during the first wave of data collection. The CES-D is a widely used 20-item measure focusing on depressed mood in the past week. Parents rate how frequently they have experienced symptoms on a scale from 0 (less than one day) to 4 (five or more days). Scores are created by summing responses. In the current sample, Cronbach’s alphas were .87 for mothers and .86 for fathers. Mothers’ mean score was 8.97 (SD = 7.97), ranging from 0 to 41; 16.7% of mothers had scores of 16 or above, indicating potentially clinical levels of depression. Fathers mean score was 8.38 (SD = 7.57), ranging from 0 to 38; 13.7% of fathers had scores of 16 or greater.

Children’s Internalizing and Externalizing Symptoms

Children’s internalizing and externalizing symptoms were assessed in the first and third waves of data collection via mother and father report on the internalizing and externalizing scales of the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach, 1991). The CBCL is a widely used measure and has excellent validity and reliability (Achenbach, 1991). The measure consists of a list of possible symptoms which the reporter rates as not true (0), somewhat true (1) or very true (2) about the child. Scores were created by summing responses on items and then converting to T scores for analysis. Mean T scores for internalizing symptoms at T3 were 53.00 (SD = 9.89) and 52.29 (SD = 9.93) for mother and father report, respectively. The percentage of children in the borderline or clinical range for internalizing symptoms ranged from 20 to 23 percent. Mean T scores for externalizing symptoms at T3 were 51.00 (SD = 9.88) and 50.94 (SD = 1031) for mother and father report, respectively. The percentage of children in the borderline or clinical range for externalizing symptoms ranged from 15 to 17 percent. In the current study, alpha coefficients ranged from .87 to .90 for the externalizing scale and .84 and .88 for the internalizing scale.

Covert Marital Negativity

At the first and second time points, parents took part in two problem-solving discussions as described in the procedures section. Immediately following these discussions, parents completed a self-report measure of their emotions and beliefs during the problem-solving discussions. This approach was taken because interrupting the interactions and asking participants to provide ratings would likely have altered couples’ experiences and reduced the external validity of the procedure. Asking couples to provide ratings immediately following the interactions is a similar alternative that preserves validity while at the same time reducing reliance on memory or the influence of additional experiences. The following emotions and beliefs were rated on a six-point Likert scale: worry, feeling sorry for my partner, worthlessness, and helplessness. These emotions and beliefs have been indicated as important in the context of depressive symptoms (Chelminski & Zimmerman, 2003; Lynch et al., 2000; Ozment & Lester, 1998; Shahar, 2001). Reliability coefficients ranged from .94 to 1.0. Data were reduced by averaging across interactions to get an overall rating for each participant. Self-reports were used because observer ratings of these specific emotions and beliefs may not be accurate (Waldinger, Schulz, & Hauser., 2004). This practice has been employed successfully in previous research (Cummings, Goeke-Morey, Papp, & Dukewich, 2002).

Overt conflict behaviors

The problem-solving discussions were also video-taped and coded by two highly trained coders for behavioral conflict behaviors according to the Marital Daily Records protocol (MDR, Cummings et al., 2002). This coding system was designed to measure conflict strategies that are particularly salient to children as they assess the meaning of interparental discord and had good convergent validity with other measures of marital conflict and relationship quality (Du Rocher Schudlich, Papp, & Cummings, 2004).

Ratings of the following behaviors were obtained: insult, threat, pursuit, and defensiveness. These behaviors were defined as follows:

Insult Insulting spouse by saying something hurtful. May include accusations, name-calling, blame, rejection and sarcasm.

Threat A physical or verbal threat, including threat to leave or divorce, threatening physical harm to oneself, others, or property.

Pursuit Nagging or hounding a partner about an issue, continuing to discuss a topic even when the other person wants to stop.

Defensiveness Trying to avoid blame or responsibility through justification, making excuses, defending position, cutting spouse off instead of listening, and responding to a criticism with a criticism. Does not include stating point-of-view.

Previous research indicates that these behaviors may be especially important in the context of depressive symptoms (Byrne et al., 2004; Coyne et al., 2002; Kingstone & Endler, 1997).

Ratings were created by assessing the presence of each of these strategies during 30 second intervals on a scale from 0 (absence of behavior) to 2 (very strong display of behavior) for both mothers and fathers. Codes for judges’ ratings of conflict behavior were summed over the 20 possible intervals for each of the two discussions (a total of 40 intervals), providing separate measures of each participant’s use of conflict behaviors.

The two coders were advanced research assistants trained extensively by the original designers of the coding system. Coders were taught detailed descriptions of each behavior. After learning definitions, research assistants coded and discussed practice interactions with the trainers. Finally, research assistants coded 30 interactions to assess reliability. Intra-class correlations assessing the reliability of coders were excellent, ranging from .82 to .99.

Results

Descriptive and Preliminary Analyses

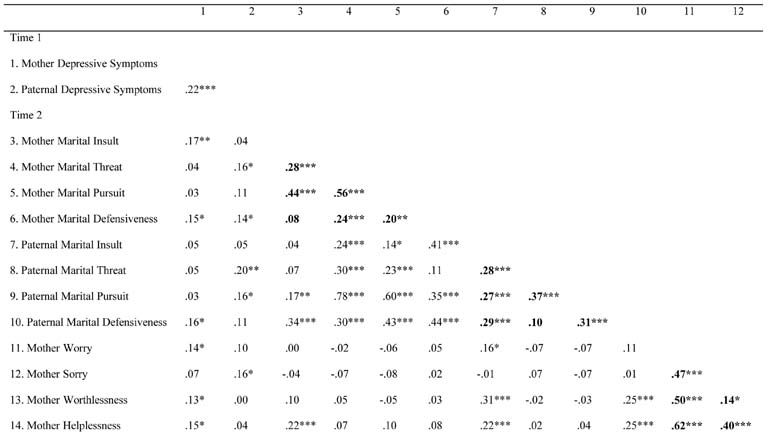

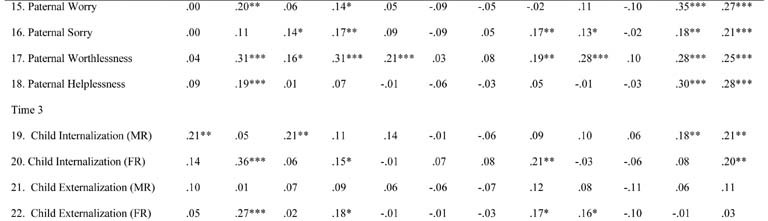

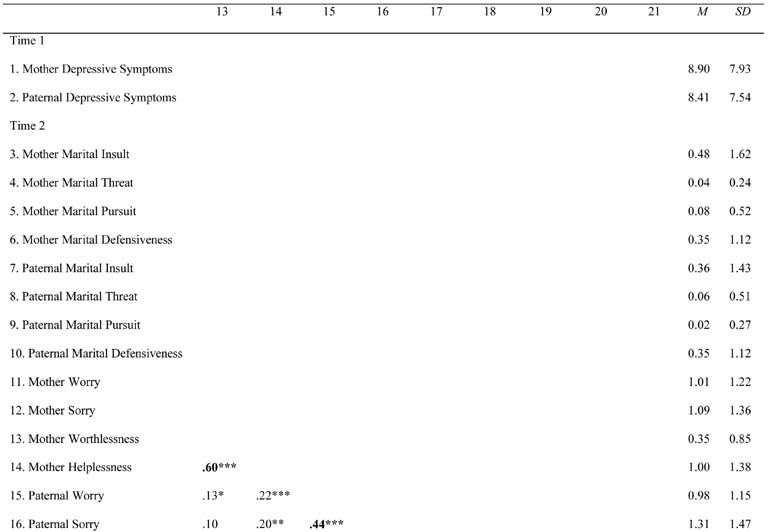

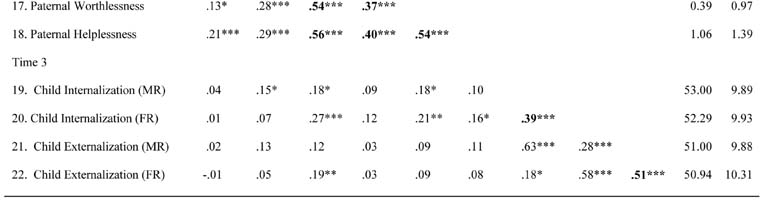

Means, standard deviations and intercorrelations between the primary variables are presented in Table 1. Inspection of the correlations between variables representing the same construct indicated the utility of creating latent variables. Correlations between variables indicating different latent constructs provided preliminary evidence for the proposed models. For example, parental depressive symptoms at T1 were related to destructive overt conflict behaviors (insult, threat, pursuit, and defensiveness) and covert negativity (worry, worthlessness, helplessness, and feeling sorry) at T2 and these dimensions of conflict were related to children’s internalizing and externalizing problems at T3.

Table 1.

Means, standard deviations and intercorrelations among all primary variables

|

|

|

|

Note: Correlations among indicators within latent constructs are denoted in bold. MR = Mother Report; FR = Father Report;

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001.

To provide additional support for the construction of latent variables for mothers’ overt and covert marital conflict, these variables were submitted to a factor analysis. Results suggested a two factor solution. Covert marital negativity loaded onto the first factor (eigenvalue = 2.44; factor loadings ranged from .57 to .88), which accounted for 30% of the variance. Overt marital behaviors did not load onto this factor (factor loadings ranged from .14 to .26). Rather, overt marital behaviors loaded onto the second factor (eigenvalue = 1.98; factor loadings ranged from .39 to .84), which accounted for 25% of the variance. Covert negativity did not load onto this factor (factor loadings ranged from −.28 to −.02). A second factor analysis, including an oblimin (non-orthogonal) factor rotation also yielded similar results (factor loadings ranging from .62 to .86 for covert negativity and from .42 to .84 for overt conflict behaviors), with the two factors showing no significant correlation (r = .05, ns). Essentially identical results were obtained for fathers’ overt and covert marital conflict.

Analysis Plan

Initial structural equation models were fit in which mothers’ and fathers’ depressive symptoms at T1 were assessed as predictors of overt and covert dimensions of marital conflict (latent variables indicated by the various observed and self-reported variables) and children’s internalizing and externalizing symptoms at T3 (latent variables based on mother and father report). Given the small sample size relative to model complexity, we fit separate models for mother’ vs. fathers’ marital conflict variables, and separate models for internalizing vs. externalizing symptoms. Thus, a total of four models were fit to the data. To account for potential bias, correlations between mothers’ depressive symptoms and the unique variance in mother report of child internalizing and externalizing symptoms, that is, the variance not shared with father report, were estimated. The same procedure for followed to control for bias associated with father reports. These correlations are not shown in the figures to simplify presentation.

Latent variable models were followed by path analyses. These models controlled for earlier levels of each predicted construct (“autoregressive effects”). When autoregressive effects are not included in longitudinal studies, prior levels of the dependent measure are confounded with the independent variables. It is therefore difficult to interpret the effects of the independent variable. Inclusion of autoregressive effects avoids this problem and permits conclusions to be drawn about change over time. An additional limitation of the prior models was the separate examination of mothers’ and fathers’ marital conflict variables, which are likely dependent. Unfortunately, including either autoregressive effects or all four measures of marital conflict results in a highly complex model that is difficult to fit with the current sample size. For this reason, measures of each construct were aggregated to form a single indicator for path analysis.

Analyses were conducted using the AMOS 4.0 statistical package, which uses maximum likelihood estimation (Arbuckle & Wothke, 1999). All models included controls for child gender. Equality constraints were also introduced to test for differential relations between mothers’ and fathers’ depressive symptoms and other variables. Models were considered an acceptable fit for the data if they met the following criteria: χ2/df ratio < 3 (Arbuckle & Wothke, 1999) and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) is < .08 (Browne & Cudek, 1993).

Parental Depressive Symptoms, Marital Conflict, and Children’s Internalizing Symptoms

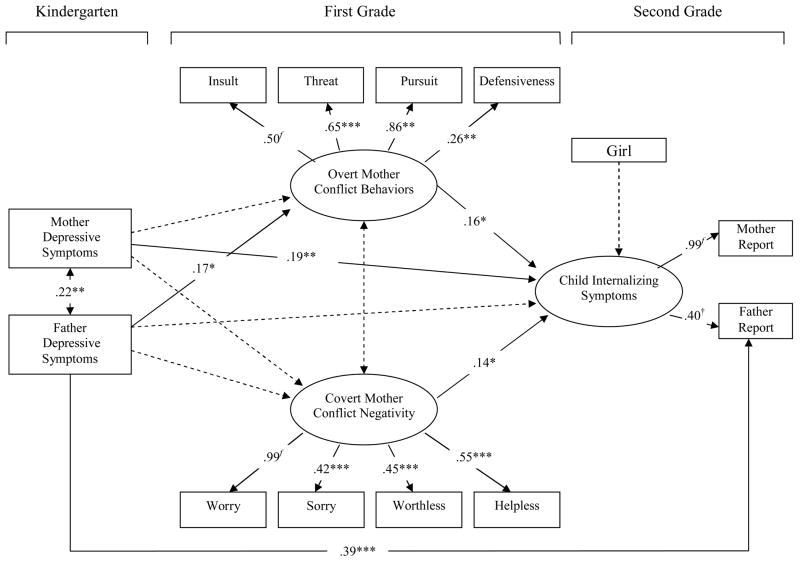

Figure 1 presents the results of fitting the model of parental depressive symptoms, mothers’ marital conflict variables, and children’s internalizing symptoms. The correlation between mothers’ depressive symptoms and the unique variance in mothers’ reports of children’s internalizing problems was not significant, p = .65, and created a problem with model fitting. Omitting this correlation resolved the problem. The resulting model is presented in Figure 1. This model was an acceptable fit for the data: χ2/df = 1.644, RMSEA = .052. Mothers’ depressive symptoms at T1 were directly associated with children’s internalizing symptoms at T3, β = .19, p < .01. Fathers’ depressive symptoms at T1 were associated with more overt destructive conflict behaviors at T2, β = .17, p < .05. These behaviors were also associated with children’s internalizing symptoms at T3, β = .16, p < .05. An association between covert marital negativity and children’s internalizing symptoms was also observed, β = .14, p = .05. These findings support mothers’ overt marital conflict behaviors as a process involved in the link between fathers’ depressive symptoms and children’s internalizing symptoms. The introduction of model constraints indicated that the direct association between parental depressive symptoms and children’s internalizing symptoms was stronger for mothers than for fathers, χ2(1) = 4.1, p < .05. No other significant differences in relations were observed.

Figure 1.

Longitudinal relations between parental depressive symptoms, mothers’ marital conflict variables, and children’s internalizing symptoms. Note: Coefficients are standardized estimates; * p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001; f denotes fixed path, χ2(54) = 88.8, p<.01; χ2/df = 1.644; RMSEA = .052.

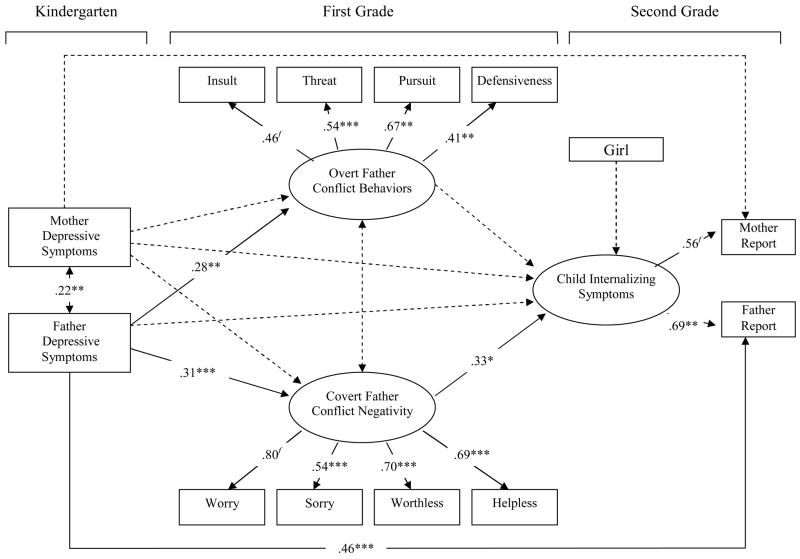

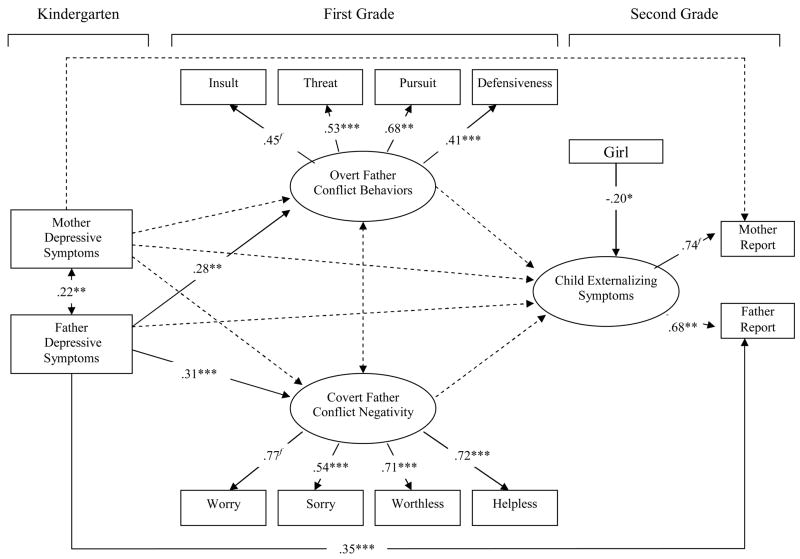

Figure 2 presents the results of fitting the model of parental depressive symptoms, fathers’ marital conflict variables, and children’s internalizing symptoms. No difficulties were encountered in fitting this model, although the correlation between mothers’ depressive symptoms and mother report of internalizing symptoms continued to be nonsignificant. This model was also an acceptable fit for the data: χ2/df = 1.873, RMSEA = .061. Fathers’ depressive symptoms were significantly associated with both overt destructive conflict behavior, β = .28, p < .001, and covert marital negativity, β = .31, p < .01. However, only covert marital negativity was linked to children’s higher internalizing symptoms, β = .33, p < .05. Although mothers’ depressive symptoms were not associated with fathers’ marital conflict variables, no direct association between mothers’ symptoms and children’s internalization was observed in this model. These findings suggest that fathers’ covert marital negativity serves as a pathway linking fathers’ depressive symptoms and children’s internalizing symptoms. The introduction of model constraints indicated that the association between parental depressive symptoms and fathers’ covert marital negativity was stronger for fathers than for mothers, χ2(1) = 7.8, p < .01. No other significant differences in relations were observed.

Figure 2.

Longitudinal relations between parental depressive symptoms, fathers’ marital conflict variables, and children’s externalizing symptoms. Note: Coefficients are standardized estimates; * p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001; f denotes fixed path, χ2(53) = 99.3, p < .001; χ2/df = 1.873; RMSEA = .061.

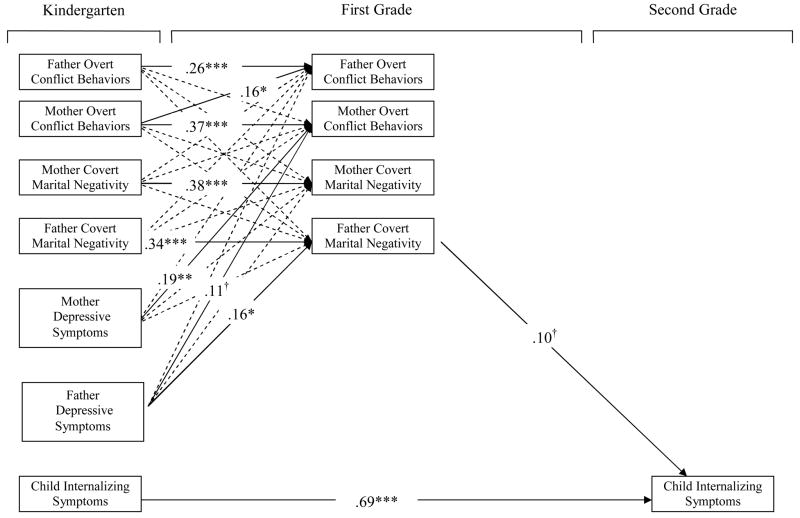

Figure 3 presents results of the path analysis including autoregressive effects and both mothers’ and fathers’ marital conflict variables. An initial model revealed that after controlling for earlier levels of internalizing symptoms, there were no significant relations between any of the other variables and children’s internalizing symptoms at T3. However, the association between fathers’ covert marital negativity and internalizing symptoms approached significance, p < .10. To determine whether this association would meet significance criteria after deleting nonsignificant pathways (including those with child gender), a second model was fit. Omitting nonsignificant paths did not alter model fit, χ2(4) = 1.6, ns. This model was an acceptable fit for the data: χ2/df = 1.488, RMSEA = .046. Results of this model are presented in Figure 3. Only pertinent associations are described here. Fathers’ depressive symptoms were associated with increased covert marital negativity over time, β = .16, p < .05. The association between fathers’ depressive symptoms and mothers’ overt destructive marital conflict behaviors approached significance, β = .11, p < .10. Mothers’ depressive symptoms were significantly associated with mothers’ increased destructive behaviors over time, β = .19, p < .01. Finally, the association between fathers’ covert marital negativity and children’s internalizing symptoms remained a trend, β = .10, p = .054. The introduction of equality constraints indicated that fathers’ depressive symptoms were marginally more strongly associated with fathers’ covert marital negativity than mothers’ depressive symptoms were, χ2(1) = 3.5, p < .10.

Figure 3.

Additional test of overt and covert dimensions of marital conflict as intervening variables. Note: Correlations between measures collected at the same point were estimated. To make the figure easier to read, neither correlations nor non-significant path coefficients are shown. Coefficients are standardized estimates; †p < .10, * p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001; χ2(32) = 47.6, p < .05; χ2/df = 1.488; RMSEA = .046.

Parental Depressive Symptoms, Marital Conflict, and Children’s Externalizing Symptoms

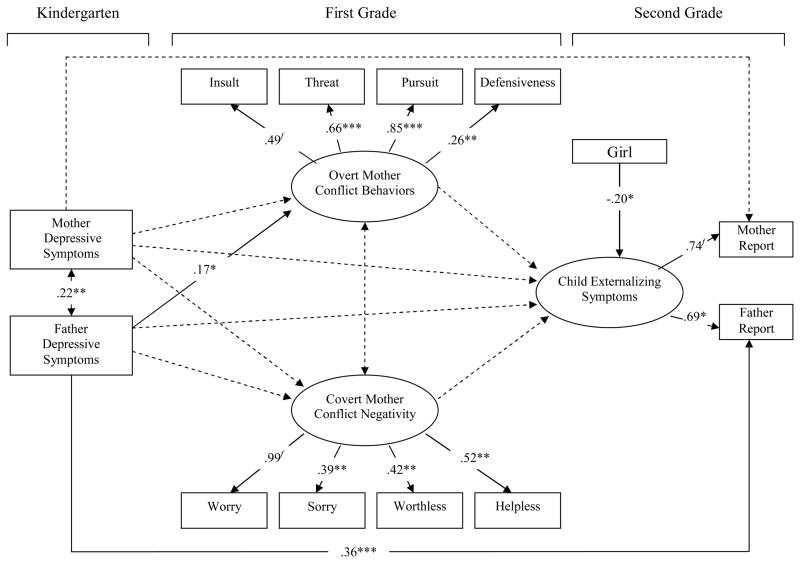

Figure 4 presents the results of fitting the model of parental depressive symptoms, mothers’ marital conflict variables, and children’s externalizing symptoms. The model was an acceptable fit for the data: χ2/df = 1.654, RMSEA = .053. Fathers’ depressive symptoms at T1 were associated with mothers’ overt destructive conflict behaviors at T2, β = .17, p < .05. However, mothers’ overt marital conflict behaviors were not associated with children’s externalizing symptoms at T3. The introduction of model constraints indicated no significant differences in relations.

Figure 4.

Longitudinal relations between parental depressive symptoms, mothers’ marital conflict variables, and children’s externalizing symptoms. Note: Coefficients are standardized estimates; * p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001; f denotes fixed path, χ2(53) = 87.7, p <.01; χ2/df = 1.654; RMSEA = .053.

Figure 5 presents the results of fitting the model of parental depressive symptoms, fathers’ marital conflict variables, and children’s externalizing symptoms. This model was also an acceptable fit for the data: χ2/df = 1.894, RMSEA = .062. Fathers’ depressive symptoms were significantly associated with both overt destructive conflict behavior, β = .27, p < .01, and covert marital negativity, β = .31, p < .001. However, neither dimension of marital conflict was associated with children’s externalizing symptoms. The introduction of model constraints indicated that the association between parental depressive symptoms and fathers’ covert marital negativity was stronger for fathers than for mothers, χ2(1) = 7.7, p < .01. No other significant differences in relations were observed.

Figure 5.

Longitudinal relations between parental depressive symptoms, fathers’ marital conflict variables, and children’s externalizing symptoms. Note: Coefficients are standardized estimates; * p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001; f denotes fixed path, χ2(53) = 100.4, p < .001; χ2/df = 1.894; RMSEA = .062.

Because neither latent variable model supported marital conflict as processes involved in the link between parental depressive symptoms and children’s externalizing symptoms, these models were not followed with path analyses.

Discussion

Results indicated that fathers’ depressive symptoms were related to mothers’ greater overt destructive conflict behaviors (i.e., threat, insult, defensiveness, pursuit) and fathers’ covert negativity in contexts of marital conflict (i.e., experience of helplessness, worthlessness, worry, feeling sorry for partners), and that these dimensions of marital conflict were associated with children’s internalizing symptoms. Father’s depressive symptoms were also associated with fathers’ greater overt destructive conflict behaviors, although these were not linked to children’s internalizing symptoms. Associations between fathers’ depressive symptoms and mothers’ overt behavior and fathers’ covert negativity were stronger than associations between mothers’ depressive symptoms and mothers’ overt behavior and fathers’ covert negativity. After controlling for autoregressive effects, modest support was found for fathers’ covert negativity as a pathway linking fathers’ depressive symptoms and children’s internalizing symptoms.

Various theories of depression provide possible explanations for why depressive symptoms may generate these conflict behaviors and emotions. For example, cognitive theories of depression (Abramson, Metalsky & Alloy, 1989; Beck et al., 1979) posit that depressed individuals have schemas characterized by negative views of the self, past events and the future. Thus, when interacting with others, depressed individuals may be more likely to make negative attributions which may in turn increase the likelihood of responding with negative comments and affect. Furthermore, interpersonal theories of depression also support links between depression and marital conflict (see Joiner & Coyne, 1999). For example, the notion that depressed people engage in excessive reassurance seeking and use poor social skills may help explain partners’ behavior in marital interactions (Coyne, 1976; Lewinsohn, 1974). For example, excessive reassurance seeking may eventually make spouses annoyed and frustrated because attempts to soothe their spouse have failed. The likelihood of using conflict behaviors such as insult and threat and experiencing covert negativity is then increased.

Results also suggest marital conflict may be involved in children’s risk for internalizing symptoms in the context of fathers’ depressive symptoms. Fathers’ covert negativity appeared especially salient for the development of children’s internalizing symptoms. These findings are consistent with past research showing that other dimensions of marital conflict beyond overt behaviors, including parents’ experience of negative emotionality, are associated with children’s greater emotional reactivity to conflict (Cummings et al., 2003), potentially leading to internalizing symptoms. Covert responding and observable behavioral content of disagreements were not associated in this study. One possible explanation is that what couples do during conflict does not necessarily correspond to how they feel or what they think, perhaps because different emotions and beliefs may motivate similar behaviors (i.e. attacking out of hurt or anger), and partners may deliberately employ behaviors that are seemingly contradictory to their feelings for beliefs (i.e. angry apology). Thus, this study highlights the role of covert aspects of conflict in the link between fathers’ depressive symptoms and children’s internalizing symptoms, and indicates that studies focusing exclusively on the behavioral content of marital conflict may be incomplete in providing a full understanding of the role of marital conflict in families. Future studies should further examine the role of the covert aspects of marital conflict.

In particular, research is needed to identify the processes through which specific forms of covert negativity that may not be apparent to non-family observers (e.g., hopelessness) serve as a mechanism of risk for children. One possibility is that children are more attuned to the subjective emotional and cognitive experience of their parents than unfamiliar observers are. This hypothesis is consistent with the emotional security theory (Davies & Cummings, 1994), which proposes that children become sensitized to conflict over time. It is also consistent with research showing that even as early as three months of age, children of depressed mothers are familiar with expressions of sadness (Hernandez-Reif, Field, Diego, Yanexy, & Pickens, 2006). Furthermore, couples’ experience of pathological forms of emotion may prevent couples from adequately resolving conflict, regardless of the problem-solving strategies that have been employed. For example, partners who are especially worried about a disagreement may continue to revisit the problem even after an adequate solution is formulated.

It is interesting that associations between depressive symptoms and dimensions of marital conflict were observed for fathers’ depressive symptoms but not mothers’ depressive symptoms. Rather, mothers’ depressive symptoms were directly associated with children’s internalizing symptoms, even after controlling for mothers’ marital conflict variables, but not after controlling for fathers’ marital conflict. The current study of five to eight-year-olds is therefore consistent with the findings of a cross-sectional study of 267 children aged eight to 16, in which marital conflict was found to be a more consistent mediator for fathers’ symptoms than for mothers’ (Du Rocher Schudlich & Cummings, 2003). One possible explanation for these findings is that mother depressive symptoms may effect children’s risk for internalizing symptoms primarily through problems in the parent-child relationship, such as hostility or withdrawal during parent-child interactions (Lovejoy, Graczyk, & Neuman, 2000). Alternatively, men’s symptoms may more negatively impact the marital relationship because they are linked to especially disruptive interpersonal patterns, such as relationship denigration (Fincham, Beach, Harold & Osborne, 1997). Recent studies of men’s depression support this interpretation: Men appear to express depression in ways that increase risk for both violence and suicide (Brownhill, Wilhelm, Barclay & Schmied, 2005; Cochran, 2005), with marital processes implicated in that risk (Troisi & D’Argenio, 2004). Thus, the presence of depressive symptoms in fathers may have especially negative implications for family functioning.

Furthermore, it is noteworthy that parental depressive symptoms and marital functioning were associated with children’s internalizing but not externalizing symptoms. It is possible that children of depressed parents have greater genetic risk for internalizing symptoms rather than externalizing symptoms. For example, genetic transmission of depression has been linked to genetic polymorphism associated with over-activation of the HPA axis (Levinson, 2006). Thus, children of depressed parents are more likely to exhibit high levels of the stress hormone cortisol, which is itself associated with the occurrence of depression (Mannie, Harmer, & Cowen, 2007). In contrast, low levels of cortisol are associated with risk for externalizing problems such as antisocial behavior (Brotman et al., 2007). Therefore, exposure to family problems such as marital conflict and specific genetic risk may interact to produce internalizing symptoms in children, rather than externalizing symptoms. However, parental depressive symptoms also are associated with children’s externalizing symptoms (Fergusson & Lynskey, 1993). It is possible that associations between parental depressive symptoms and children’s externalizing symptoms are stronger for boys, as boys are more likely to exhibit externalizing symptoms generally (Stanger, Achenbach, & Verhulst, 1997). Additional research exploring child gender as a moderator of relations is therefore needed.

Several important limitations to the current study should be noted. First, a design limitation was the relatively low sample size relative to the complexity of fitted models. This study therefore had low power to detect effects, which may have accounted for the absence of significant relations between marital functioning and children’s internalizing and externalizing symptoms after controlling for autoregressive effects. Reliance on parent report of both depressive symptoms and children’s internalizing and externalizing symptoms is an additional limitation, although correlating each parents’ symptoms with their report of child outcomes likely reduced the amount of bias. Covert marital negativity is also a difficult construct to assess. Having parents complete self-reports of their experience immediately following their interactions was judged to be the most appropriate strategy, but it is possible that these self-reports lack important information about minute-by-minute experiences of covert negativity throughout the duration of the interaction. Notably, these reports yielded relatively low mean levels and variability of covert negativity. However, this was consistent with observations of overt destructive marital conflict behaviors. Future research may address this limitation by exploring alternative forms of overt or covert negativity that may be more common, or samples in which there are greater levels and variability in these aspects of marital conflict. Moreover, the design of the study prevented the empirical evaluation of genetic effects in the link between parental depressive symptoms and children’s internalizing and externalizing symptoms. It is noteworthy that exposure to marital conflict or parental depressive symptoms likely reflects a combination of genetic and environmental influence (McGue, & Lykken, 1992; Towers, Spotts, & Neiderhiser, 2002) and future research is needed to tease apart the relative role of the genetic versus environmental nature of family effects on child development. Finally, findings from a community sample may not be generalizable to populations facing important challenges like poverty or community conflict, or to populations of differing racial, ethnic, or cultural backgrounds. Future research is needed to address the role of parental depressive symptoms and marital functioning in these diverse settings.

Despite the important limitations of the current study, findings advance understanding of relations between parental depressive symptoms and children’s internalizing and externalizing symptoms. Specifically, dimensions of marital conflict appear important in the potential effects of fathers’ depressive symptoms on the development of children’s internalizing symptoms. Further, findings emphasize the importance of considering covert aspects of marital conflict, such as feelings of worthlessness and hopelessness, in the study of parental depression, family functioning, and children’s psychological development.

Acknowledgments

Preparation of this paper was supported in part by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (Project R01 MH57318) awarded to Patrick Davies and Mark Cummings. The authors are grateful to the children and parents who participated in this project. Their gratitude is also expressed to the staff and students who assisted on various stages of the project, including Courtney Forbes, Marcie Goeke-Morey, Amy Keller, and Michelle Sutton.

References

- Abramson LY, Metalsky GI, Alloy LB. Hopelessness depression: A theory-based subtype of depression. Psychological Review. 1989;96:358–372. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the child behavior checklist 4–18 and 1991 profile. Burlington: University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle JL, Wothke W. Amos 4.0 users guide. Chicago: Small Waters; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Rush AJ, Shaw BF, Emery G. Cognitive therapy of depression. New York: Guliford Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Brotman LM, Gouley KK, Huang KY, Kamboukos D, Fratto C, Pine DS. Effects of a psychosocial family-based preventive intervention on cortisol response to a social challenge in preschoolers at high risk for antisocial behavior. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2007;64:1172–1179. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.10.1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown GW, Harris T. Social origins of depression: A reply. Psychological Medicine. 1978;8:577–588. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700018791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne WM, Cudeck R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In: Bollen KA, Long JS, editors. Testing structural equation models. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1993. pp. 445–455. [Google Scholar]

- Brownhill S, Wilhelm K, Barclay L, Schmied V. Big build: Hidden depression in men. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;39:921–931. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2005.01665.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne M, Carr A, Clark M. Power in relationships of women with depression. Journal of Family Therapy. 2004;26:407–429. [Google Scholar]

- Chase-Lansdale PL, Wakschlag LS, Brooks-Gunn J. A psychological perspective on the development of caring in children and youth: The role of the family. Journal of Adolescence. 1995;18:515–556. [Google Scholar]

- Chelminski I, Zimmerman M. Pathological worry in depressed and anxious patients. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2003;17:533–546. doi: 10.1016/s0887-6185(02)00246-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Cummings EM, Greenberg MT, Marvin RS. An organizational perspective on attachment beyond infancy: Implications for theory, measurement, and research. In: Cicchetti D, Greenberg MT, editors. Attachment in the preschool years: Theory, research, and intervention. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1990. pp. 3–49. [Google Scholar]

- Cochran SV. Assessing and treating depression in men. In: Glenn GE, Brooks GR, editors. The new handbook of psychotherapy and counseling with men: A comprehensive guide to settings, problems, and treatment approaches. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2005. pp. 121–133. [Google Scholar]

- Coyne JC. Toward an interactional description of depression. Psychiatry. 1976;39:28–40. doi: 10.1080/00332747.1976.11023874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyne JC, Thompson R, Palmer SC. Marital quality, coping with conflict, marital complaints, and affection in couples with a depressed wife. Journal of Family Psychology. 2002;16:26–37. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.16.1.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Davies PT. Maternal depression and child development. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1994;35:73–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1994.tb01133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Goeke-Morey MC, Papp LM. A family-wide model for the role of emotional functioning. Marriage and Family Review. 2003;34:13–34. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Goeke-Morey MC, Papp LM, Dukewich T. Children’s responses to mothers’ and fathers’ emotionality and tactics in marital conflict in the home. Journal of Family Psychology. 2002;16:478–492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Keller PS, Davies PT. Towards a family process model of maternal and paternal depressive symptoms: Exploring multiple relations with child and family functioning. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2005;46:479–489. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00368.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies PT, Cummings EM. Marital conflict and child adjustment: An emotional security hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin. 1994;116:387–411. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.116.3.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies PT, Windle M. Gender-specific pathways between maternal depressive symptoms, family discord, and adolescent adjustment. Developmental Psychology. 1997;12:163–177. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.33.4.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis B, Sheeber L, Hops H, Tildesley E. Adolescent responses to depressive parental behaviors in problem-solving interactions: Implications for depressive symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2000;28:451–465. doi: 10.1023/a:1005183622729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeFife JA, Hilsenroth MJ. Clinical utility of the defensive functioning scale in the assessment of depression. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2005;193:176–182. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000154839.43440.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downey G, Coyne JC. Children of depressed parents: An integrative review. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;108:50–76. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.108.1.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du Rocher Schudlich TD, Cummings EM. Parental dysphoria and children’s internalizing symptoms: Marital conflict styles as mediators of risk. Child Development. 2003;74:1–19. doi: 10.1046/j.1467-8624.2003.00630.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du Rocher Schudlich TD, Papp LM, Cummings EM. Relations of husbands’ and wives’ dysphoria to marital conflict resolution strategies. Journal of Family Psychology. 2004;18:171–183. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.18.1.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fava GA, Mangelli L. Assessment of subclinical symptoms and psychological well-being in depression. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience. 2001;251:1147–1152. doi: 10.1007/BF03035127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felsten G. Hostility, stress, and symptoms of depression. Personality and Individual Differences. 1996;21:461–467. [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Lynskey MT. The effects of maternal depression on child conduct disorder and attention deficit behaviours. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 1993;28:116–123. doi: 10.1007/BF00801741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fincham FD, Beach SRH, Harold GT, Osborne LN. Marital satisfaction and depression: Different causal relationships for men and women? Psychological Science. 1997;8:351–357. [Google Scholar]

- Goeke-Morey MC, Cummings EM, Harold GT, Shelton KH. Categories and continua of destructive and constructive marital conflict tactics from the perspective of U.S. and Welsh children. Journal of Family Psychology. 2003;17(3):327–338. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.17.3.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottman JM. What predicts divorce? The relationship between marital processes and marital outcomes. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Gottman JM. The marriage clinic: A scientifically based marital therapy. New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Co, Inc; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez-Reif M, Field T, Diego M, Yanexy V, Pickens J. Brief report: Happy faces are habituated more slowly by infants of depressed mothers. Infant Behavior & Development. 2006;29:131–135. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2005.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hops H. Intergenerational transmission of depressive symptoms: Gender and developmental considerations. In: Godstein MJ, Mundt C, editors. Interpersonal factors in the origin and course of affective disorders. London, England: Gaskell Royal College of Psychiatrists; 1996. pp. 113–129. [Google Scholar]

- Joiner T, Coyne JC. The interactional nature of depression: Advances in interpersonal approaches. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Kane P, Garber J. The relations among depression in fathers, children’s psychopathology, and father-child conflict: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review. 2004;24(3):339–360. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2004.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingstone JC, Endler NS. Supportive vs. defensive communications in depression: An assessment of Coyne’s interactional model. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science. 1997;29:44–53. [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RF, Watson D, Barlow DH. Introduction to the special section: Toward a dimensionally based taxonomy of psychopathology. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2005;114:491–493. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.4.491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb ME, editor. The role of the father in child development. 4. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Levenson RW, Gottman JM. Marital interaction: Physiological linkage and affective exchange. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1983;45:587–597. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.45.3.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levinson DF. The genetics of depression: A review. Biological Psychiatry. 2006;60:84–92. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn PM. A behavioral approach to depression. In: Friedman RM, Katz MM, editors. The psychology of depression: Contemporary theory and research. New York: Wiley; 1974. pp. 132–149. [Google Scholar]

- Lovejoy MC, Graczyk PA, O’Hare E, Neuman G. Maternal depression and parenting behavior: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2000;20(5):561–592. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(98)00100-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch TR, Compton JS, Mendelson T, Robins CJ, Krishnan KRR. Anxious depression among the elderly: Clinical and phenomenological correlates. Aging and Mental Health. 2000;4:268–274. [Google Scholar]

- Mannie ZN, Harmer CJ, Cowen PJ. Increased waking salivary cortisol levels in young people at familial risk of depression. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;164:617–621. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.4.617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martins C, Gaffan EA. Effects of early maternal depression on patterns of infant-mother attachment: A meta-analytic investigation. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2000;41:737–746. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGue M, Lykken DT. Genetic influence on risk of divorce. Psychological Science. 1992;3:368–373. [Google Scholar]

- Murray L, Fiori-Cowley A, Hooper R, Cooper P. The impact of postnatal depression and associated adversity on early mother-infant interactions and later infant outcomes. Child Development. 1996;67:2512–2526. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozment JM, Lester D. Helplessness and depression. Psychological Reports. 1998;82:434. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1998.82.2.434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phares V. Fathers and developmental psychopathology. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Phares V. “Poppa” Psychology: The role of fathers in children’s mental well-being. Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Phares V, Duhig AM, Watkins M. Family context: Fathers and other supports. In: Goodman IH, Gotlib SH, editors. Children of depressed parents: Mechanisms of risk and implications for treatment. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Phares V, Lopez E, Fields S, Kamboukos D, Duhig AM. Are fathers involved in pediatric psychology research and treatment? Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2005;30:631–643. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsi050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Sayers SL, Kohn CS, Fresco DM, Bellack AS, Sarwer DB. Marital cognitions and depression in the context of marital discord. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2001;25:713–732. [Google Scholar]

- Shahar G. Personality, shame, and the breakdown of social bonds: The voice of quantitative depression research. Psychiatry: Interpersonal and Biological Processes. 2001;64:228–239. doi: 10.1521/psyc.64.3.228.18463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanger C, Achenbach TM, Verhulst FC. Accelerated longitudinal comparisons of aggressive versus delinquent syndromes. Development and Psychopathology. 1997;9:43–58. doi: 10.1017/s0954579497001053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Towers H, Spotts EL, Neiderhiser JM. Genetic and environmental influences on parenting and marital relationships: Current findings and future directions. Marriage & Family Review. 2002;33:11–29. [Google Scholar]

- Troisi A, D’Argenio A. The relationship between anger and depression in a clinical sample of young men: The role of insecure attachment. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2004;79:269–272. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0327(02)00406-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldinger RJ, Schulz MS, Hauser ST. Reading others’ emotions: The role of intuitive judgments in predicting marital satisfaction, quality, and stability. Journal of Family Psychology. 2004;18(1):58–71. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.18.1.58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman MM, Warner V, Wickramratne P, Moreau D, Olfson M. Offspring of depressed parents: 10 years later. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1997;54:932–940. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830220054009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whisman MA. The association between depression and marital dissatisfaction. In: Beach SRH, editor. Marital and family processes in depression: A scientific foundation for clinical practice. Washington, DC, US: American Psychological Association; 2001. pp. 3–24. [Google Scholar]