Abstract

Based on clinical and pathological experience, indistinct margin-type hepatocellular carcinomas (HCCs) were considered to be typical early-stage HCCs with good prognosis. For histological diagnosis, the assessment of stromal invasion (tumor invasion into portal tracts and fibrous septa) is very important. In differentiating stromal invasion from pseudoinvasion (benign hepatic tissue in the fibrous stroma), the following 5 items are useful: (1) macroscopic or panoramic views of the histological specimen, (2) amount of fibrous components of the stroma, (3) destruction of the structure of portal tracts, (4) loss of reticulin fibers around cancer cells, and (5) cytokeratin 7 immunostaining for ductular proliferation. Parenchymal features of early HCCs are summarized as follows: (1) thin trabecular structure, (2) hypercellularity, (3) hyperstainability of cytoplasm, and (4) microacinar formation. Detailed understanding of the total biopsy procedure and various difficult lesions is necessary for a correct biopsy diagnosis. Evaluation of noncancerous tissue is also required to attain a better understanding of the developmental process and clinical stages of HCCs.

Keywords: Early hepatocellular carcinoma, Indistinct margin nodules, Stromal invasion, Biopsy diagnosis

Introduction

Owing to the recent advances in imaging modalities and surgical techniques, many small, early-stage hepatocellular carcinomas (HCCs) have been detected, biopsied, and resected. Pathological examination of these biopsied or resected specimens has led to a clarification of the histological features of early-stage HCCs (early HCCs). However, in the daily practical clinical setting, pathologists and clinicians encounter various complex cases that are difficult to diagnose definitively. Not only small and early HCCs but also noncancerous hepatocellular nodular lesions, such as dysplastic nodules (DNs), large regenerative nodules (LRNs), focal nodular hyperplasias (FNHs), and hepatocellular adenomas (HAs), have been detected more frequently. Pathologists and clinicians have to differentiate early HCCs from these noncancerous lesions by using various imaging techniques, clinical information, and biopsy specimens preoperatively. In some cases, final diagnosis has to be made on the basis of the resected specimen. Although many studies on early HCCs have been published, we are aware of few articles that describe in detail, together with the use of many figures, how such lesions are diagnosed histologically. In this article, the histological features of typical early HCCs and their developmental process are presented. Especially for daily clinical practice, we herein describe the details of the histological diagnosis as clearly as possible.

Pathological features of early HCCs

The concept of early HCCs has been established in Japan on the basis of the accumulated clinical and pathological information of small, early-stage HCCs.

The term “early HCC” means HCC in an early stage both biologically and clinically. Early HCCs have a better prognosis than more advanced HCCs [1]. Early HCCs are small in size (usually <2 cm). They show an indistinct (vague) nodular pattern macroscopically and have portal tracts within the cancer nodules [1]. Histologically, they are well differentiated and lack prominent cellular and structural atypia [1–4]. Hepatocellular carcinomas with a distinct nodular pattern, on the other hand, are considered to be more advanced HCCs [1, 5, 6].

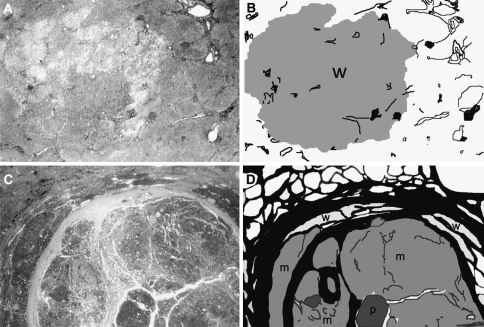

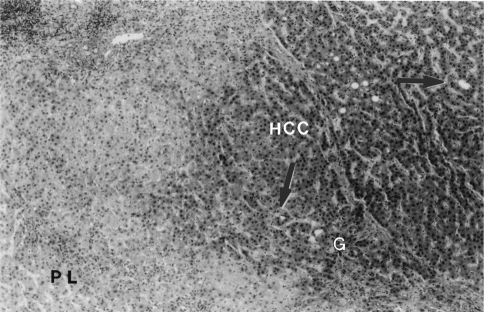

Two typical HCCs, an early one with an indistinct (vague) margin and an advanced one with a distinct margin, are shown in Fig. 1. The nodule with the indistinct margin is an HCC of 1.4-cm diameter, and its panoramic view (low magnification) and illustration are shown in Fig. 1a, b, respectively. The nodule with the distinct margin is an HCC of 2.6-cm diameter, and its panoramic view and illustration are shown in Fig. 1c, d, respectively. The histological features of another case of a typical early HCC (1.5-cm diameter) are shown in Fig. 2. The cancer tissue (HCC) shows a thin trabecular pattern and lacks prominent cytological atypia. However, in comparison with the pseudolobule of liver cirrhosis of the noncancerous area (PL), cancer tissue shows nuclear crowding (hypercellularity), hyperstainability of the cytoplasm (hyperbasophilia or hypereosinophilia), and some areas of microacinar formation. In the area of (G) (Glisson’s sheath = portal tract), fibrous stroma is invaded by tumor tissue (stromal invasion). These features have been determined to be typical histological features of early HCCs [4–11]. Fatty changes are also frequently found in early HCCs [12].

Fig. 1.

A typical early hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) with indistinct (vague) margin and a typical advanced HCC with distinct margin. a A panoramic view of an early HCC of 1.4-cm diameter. b An illustration of panel a. The tumor margin is indistinct. The cancer tissue consists only of well-differentiated HCC (w). Pre-existing hepatic architectures (portal tracts) are well preserved within the nodule. The noncancerous tissue is precirrhotic (not advanced cirrhosis). c A panoramic view of an advanced HCC of 2.6-cm diameter. d An illustration of panel c. The tumor margin is distinct with thick fibrous capsule. The cancer tissue consists of well- (w), moderately (m), and poorly (p) differentiated types. Well-differentiated type tissue is found only in the peripheral area of the nodule. The cancer nodule is occupied mostly by moderately and poorly differentiated types. The noncancerous tissue corresponds to advanced cirrhosis. Adapted from Kondo and Ebara [7]

Fig. 2.

Histological features of a typical early hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) (indistinct nodular type, 1.5 cm in diameter). The cancer tissue (HCC) shows a thin trabecular pattern (2 cells thick). In comparison with the pseudolobule of liver cirrhosis of the noncancerous area (PL), cancer tissue shows nuclear crowding (hypercellularity) and hyperstainability of cytoplasm. Arrows indicate microacinar formations. (G) shows the area of Glisson’s sheath (= portal tract), where fibrous stroma is invaded by tumor tissue (stromal invasion) (HE stain). Reprinted from Kondo et al. [8]

Histological diagnosis of early HCCs in resected, autopsied, and biopsied specimens

It is of utmost importance to correctly perform a histological diagnosis of early HCCs. The methods and knowledge required for the histological diagnosis, first for the resected or autopsied specimens and then biopsied specimens, are as follows.

Histological diagnosis of early HCCs of resected or autopsied specimens

Stromal invasion needs to be evaluated carefully, since some early HCCs (very well differentiated HCCs) do not show the usual parenchymal atypia of early HCCs such as hypercellularity and hyperstainability of the cytoplasm, as described earlier.

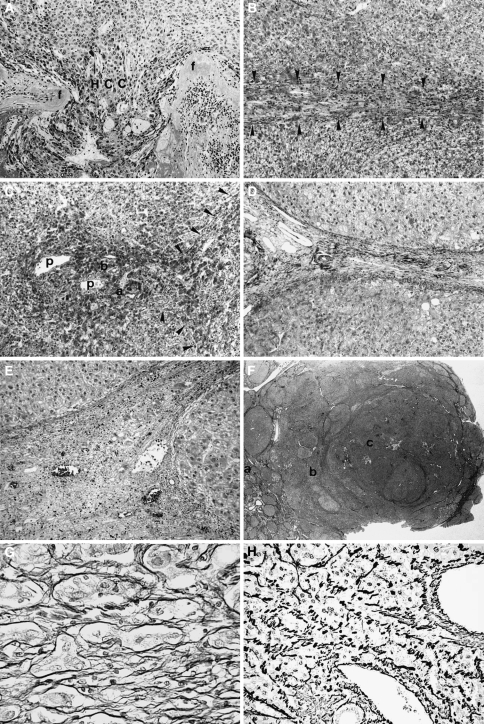

Stromal invasion, formerly called interstitial invasion [13, 14], is defined as invasive growth of tumor tissue into fibrous septa, portal tracts, and/or blood vessels [13–17]. It is histologically classified into 3 types: crossing, longitudinal, and irregular (Fig. 3) [14].

Fig. 3.

Stromal invasion of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). a Crossing type. Cancer tissue (HCC) invades across fibrous septa (f) of tumor nodule. b Longitudinal type. Tumor cells grow longitudinally within fibrous septa (arrowheads). c Irregular type. Portal areas are irregularly invaded by tumor cells. Portal veins (p), an artery (a), and a bile duct (b) are surrounded by tumor cells. Arrowheads show longitudinal type invasion in the adjacent fibrous septa. d A noncancerous area without invasion. A portal area and fibrous septa are clearly seen. e Pseudoinvasion. Benign noncancerous cells are found in the fibrous stroma. f A panoramic view of stromal invasion. In the noncancerous area without invasion [the area of (a)], the fibrous septa are clearly seen. In the area of tumor spread [the area of (b)], the septa are indistinct because stromal invasion of the longitudinal and irregular types (b, c) reduced the amount of the fibrous component. In the area of (c), hepatic architecture is severely disturbed because of stromal invasion of crossing type. g Silver staining of the pseudoinvasion. The liver cells are clearly surrounded by reticulin fibers. h Silver staining of the true invasion. Carcinoma cells are not surrounded by reticulin fibers. Adapted from Kondo et al. [8, 14]

In the crossing type, HCC invades across fibrous septa of tumor nodules (Fig. 3a). In the longitudinal type, tumor cells grow longitudinally within fibrous septa (Fig. 3b). In the irregular type, tumor cells irregularly invade portal areas (Fig. 3c). The crossing type is usually found in moderately or poorly differentiated HCCs. Both the longitudinal type and the irregular type are usually found in well-differentiated HCCs, although also at times in moderately or poorly differentiated HCCs. In the evaluation of stromal invasion, comparison of cancer areas with noncancerous areas is very useful (Fig. 3d). It is also very important to differentiate “pseudoinvasion” from true stromal invasion. Pseudoinvasion refers to benign noncancerous tissue in the fibrous stroma (Fig. 3e), and it resembles stromal invasion.

For the differentiation, the following factors require attention:

Macroscopic and/or panoramic (low magnification) views of the nodule.

Amount of fibrous components of the stroma.

Continuity to vascular invasion and destruction of the structure of portal tracts.

Loss of reticulin fibers around cancer cells.

Cytokeratin 7 immunostaining.

Stromal invasion can be detected even by a macroscopic view and/or panoramic view of histological specimens. As can be seen in Fig. 3f, in the noncancerous area without invasion [area of (a)], the fibrous septa are clearly visible. However, in the area of tumor spread [area of (b)], the septa are indistinct. In these indistinct septa, tumor invasion can then be detected by microscope (Fig. 3b, c). The amount of the fibrous component is quite different between the invasive and noninvasive areas, an important point for the differentiation from pseudoinvasion. The amount of the fibrous component is reduced as a result of the tumor invasion, and this reduction causes the indistinctness of the fibrous septa. Pseudoinvasion is usually caused by fibrosis around benign nontumorous liver tissue. Therefore, it rarely shows any reduction in the fibrous component.

The continuity to vascular invasion and destruction of the structure of portal tracts are also important findings. The former is a decisive finding of malignancy. Although it is not a common finding, it can be detected in some early HCCs. Destruction of the portal tract structure is more frequently found in stromal invasion. Pseudoinvasion does not show such a feature.

Loss of reticulin fibers around the cancer cells is another useful finding [16]. Figure 3g shows silver staining of pseudoinvasion and Fig. 3h that of true invasion. The liver parenchyma is clearly surrounded by reticulin fibers in the pseudoinvasion. In contrast, the liver tissue of the true invasion lacks such surrounding reticulin fibers. Tumor cells are embedded in the septal fibers without being clothed by reticulin fibers. However, it must be noted that reticulin clothes are sometimes observed within and around true invasive areas. After the invasive process has run its course, the cancer cells form ordinary cancer tissue areas. In such a phase of tumor growth, reticulin fibers are formed again.

Recently, Park et al. [17] reported that cytokeratin 7 immunostaining is useful for identifying stromal invasion. Ductular reaction, confirmed by cytokeratin 7 staining, is frequently found in noncancerous hepatocellular nodular lesions, whereas it is less frequently found in HCCs with true stromal invasion.

Histological diagnosis of early HCCs of biopsied specimens

Biopsy diagnosis is far more difficult than the diagnosis of resected or autopsied specimens. We cannot evaluate stromal invasion because of the very small amount of material from biopsied specimens. Only when parenchymal atypia are definite can the lesion be diagnosed as HCC. As described earlier, parenchymal atypia of early HCC are summarized as follows [4–11, 18]:

Hypercellularity (nuclear crowding).

Hyperstainability of cytoplasm (hyperbasophilia or hypereosinophilia).

Microacinar formation.

Fatty changes are also frequently found in early HCCs [12].

However, these features are not specific findings for early HCCs only. Some benign lesions and conditions show histological features closely resembling early HCCs. To perform biopsy diagnosis, we have to have precise knowledge of such early HCC-like features. Furthermore, pathologists and clinicians should understand the total process of the biopsy diagnosis in detail.

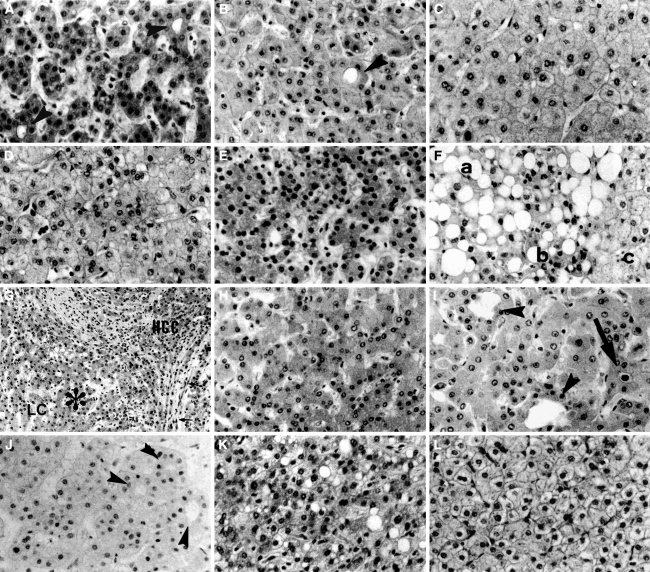

Various difficult cases

Various lesions and conditions are listed in Table 1 and shown in Fig. 4. Any of these can make biopsy diagnosis difficult. Other than true dysplastic nodules [19, 20], very well differentiated HCCs, large regenerative nodules [19–23] with high cellularity, mixture of HCC cells and benign cells, well-differentiated HCCs with marked fatty change, benign large regenerative nodules with marked fatty change, thick sliced specimens with high cellularity and strong stainability of cytoplasm, and FNH with high cellularity and microacinar formation can be arbitrarily diagnosed as dysplastic nodules despite not being true dysplastic nodules. Or the result can be a false-negative or a false-positive diagnosis. We have to consider all these conditions when we encounter very difficult cases. When making a biopsy diagnosis, the term “dysplastic nodule” can be interpreted as a tentative diagnosis that includes the possibility of these difficult cases and the term “borderline lesion” or “difficult lesion” can be used.

Table 1.

Various difficult cases and the points of differentiation

| Various difficult cases | Points of differentiation |

|---|---|

| 1. Dysplastic nodules | Difficult to diagnose definitively by biopsy If resected or autopsied specimen shows parenchymal atypia as intermediate features between benign liver tissue and well differentiated HCC and no stromal invasion, a definitive diagnosis is made |

| 2. Very well differentiated HCCs | Difficult to diagnose definitively by biopsy If resected or autopsied specimen shows stromal invasion, a definitive diagnosis is made |

| 3. Large regenerative nodules with high cellularity | Difficult to diagnose definitively by biopsy However, comparison with extra-nodular control tissue is sometimes useful. In such cases, control tissue also shows high cellularity to some extent |

| 4. Mixture of HCC cells and benign cells | Difficult to diagnose definitively by biopsy Careful examination is necessary in resected or autopsied specimens |

| 5. Well differentiated HCCs with marked fatty change | Tumor tissue without fatty change should be searched If this tissue shows the features of well differentiated HCC (hypercellularity double of that in control tissue), a definitive diagnosis is made |

| 6. Benign large regenerative nodules with marked fatty change | Nodule tissue without fatty change should be searched If this tissue shows the same features as control tissue, the diagnosis is benign liver tissue (a large regenerative nodule or sampling error) |

| 7. Thick sliced specimens with high cellularity and strong stainability of cytoplasm | Specimens must be processed carefully. Nodule tissue and control tissue must be sliced at the same thickness and stained with the same conditions |

| 8. Focal nodular hyperplasia (FNH) with high cellularity and microacinar formation | Difficult to diagnose definitively only by biopsy However, a comprehensive evaluation of biopsy specimens and imaging findings is very usefula |

HCC: hepatocellular carcinoma, FNH: focal nodular hyperplasia

aWhen the biopsy specimen shows histology of well differentiated HCC or FNH, silver staining for reticulin fibers is recommended. If the lesion shows loss of reticulin fibers, it is diagnosed as an HCC. If the lesion shows intact reticulin fibers, vascularity of the lesion in imaging findings should be evaluated. If it is a hypo-vascular (hypo-arterial) lesion, it is very likely to be a well differentiated HCC. If it is a hyper-vascular lesion, it is very likely to be an FNH. A (very) well differentiated HCC with intact reticulin fibers is usually hypo-vascular in imaging findings, while an FNH and a moderately differentiated HCC are usually hyper-vascular

Fig. 4.

Various histological findings useful for the biopsy diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma. a A well-differentiated hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Arrowheads show microacinar formation. b A dysplastic nodule. An arrowhead shows microacinar formation. c Noncancerous tissue. d A very well-differentiated HCC. Although it does not show hypercellularity, it shows stromal invasion outside this figure (same case as in Fig. 3b, c). Noncancerous tissue of this case shows lower cellularity than this HCC. e A large regenerative nodule with hypercellularity. In some cases of cirrhosis, ordinary regenerative nodules show such high cellularity. f An HCC with fatty change. In the area (a) with fatty change, diagnosis is difficult because true cellularity is secondarily reduced by fatty change. In the area of (b) without fatty change, cellularity is clearly higher than in the noncancerous area (c). g and h An area with a mixture of HCC cells and benign cells. g Low magnification. (HCC) shows cancer area with stromal invasion. (LC) shows noncancerous liver cirrhosis. In the area of (*), cancer cells and benign cells are mixed. h High magnification of the (*) area. It shows intermediate cellularity between well-differentiated HCC (a) and noncancerous tissue (c). i Liver tissue near a metastatic tumor. The arrow shows bile. Microacinar formations (arrowheads) are thought to be caused by cholestasis. j Nodular regenerative hyperplasia. Hypercellularity and microacinar formation (arrowheads) make this tissue resemble well-differentiated HCC. k Focal nodular hyperplasia (FNH) with high cellularity. It resembles well-differentiated HCC. l FNH without hypercellularity. It is similar to ordinary noncancerous tissue (HE stain). Adapted from Kondo et al. [8]

Total process of biopsy diagnosis

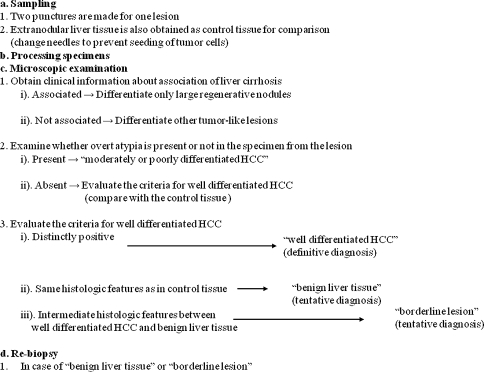

In spite of these difficulties, it is still necessary that the biopsy diagnosis be carried out as correctly as possible. For an accurate biopsy diagnosis, we have established a detailed biopsy procedure [18]. Both pathologists and clinicians should understand the total process of the biopsy diagnosis (Fig. 5), which consists of (a) sampling, (b) processing specimens, (c) microscopic examination, and (d) re-biopsy.

Fig. 5.

Total process of biopsy diagnosis. Adapted from Ohto et al. [18]

Especially for small lesions, 2 punctures should be made to avoid sampling error. In addition, extranodular liver tissue should be obtained as control tissue for comparison, since histological criteria for the biopsy diagnosis are difficult to evaluate without this comparison. Noncancerous liver tissue of other patients cannot be used as control tissue because the cellularity of liver tissue varies according to the individual patients.

In processing specimens, tissues of the lesion and the control have to be sliced at the same thickness and stained in the same manner. This is very important for evaluating the cellularity and stainability of the cytoplasm of the lesion.

In conjunction with the microscopic examination, clinical information, especially of the association of liver cirrhosis and virus markers, should be obtained. The differential diagnosis might need adjustments depending on the clinical information. For the differential diagnosis of HCC, we recommend classifying these various lesions depending on the association of liver cirrhosis (or carrier state of hepatitis virus) (Table 2). This classification is very useful because most HCCs emerge from cirrhotic livers that are usually caused by hepatitis viruses.

When liver cirrhosis is present, we should differentiate large regenerative nodules and dysplastic nodules from HCCs.

In the absence of liver cirrhosis or in normal liver, we have to differentiate HA, FNH, and nodular regenerative hyperplasia (NRH). They usually occur in a noncirrhotic liver, and their parenchymal histological features are very similar to each other. Thus, a definitive diagnosis of FNH, NRH, or HA on the basis of biopsy alone is impossible. However, a comprehensive evaluation of their imaging findings and their clinical data should result in their correct diagnosis. The method was described in detail in a previous article [24].

Regarding the metastatic tumor and cholangiocellular carcinoma, they can be easily differentiated from HCC. This classification may, in fact, seem too pragmatic, but a classification depending on the clinical data is common in the diagnosis of other organs, for example, bone and soft tissue tumors.

Table 2.

Differential diagnosis depending on the association of liver cirrhosis

| A: Associated |

| Large regenerative nodule (LRN) |

| Dysplastic nodule (DN) |

| B: Not associated |

| Hepatocellular adenoma (HA) |

| Focal nodular hyperplasia (FNH) |

| Nodular regenerative hyperplasia (NRH) |

| C: Independent of association |

| Hemangioma, cholangiocellular carcinoma (CCC) |

| Metastatic tumor |

When there is association with liver cirrhosis, as well as apparent atypia in the specimen, this lesion can easily be diagnosed as HCC of moderately or poorly differentiated type. When there is no definite atypia for this diagnosis, criteria for well-differentiated HCC is used for making a comparison with control tissue. When the specimen shows distinctly positive findings, that is, double the hypercellularity of the control tissue, it is diagnosed as “well differentiated HCC.” It is a definitive diagnosis. When the specimen shows features similar to control tissue, we diagnose it as “benign liver tissue.” Nonetheless, this is a tentative diagnosis, because the possibility of sampling error cannot be excluded. Especially in cases without cirrhosis, the term “benign liver tissue” also includes the possibility of various benign lesions, such as LRN, HA, FNH, NRH, etc. These benign hepatocellular lesions should be diagnosed by comprehensive evaluation based on clinical data, imaging findings, and histological findings [24]. When the specimen has intermediate features between HCC and benign liver tissue, we diagnose it as “borderline lesion.” This is also a tentative diagnosis because such features can be caused by various conditions and lesions, as shown previously (Table 1 and Fig. 4). The term “dysplastic nodule” can also be used. In cases of biopsy diagnosis, however, we prefer “borderline lesion” to “dysplastic nodule” because the former term has a meaning of tentative diagnosis. In fact, the lesions diagnosed as dysplastic nodules by biopsy sometimes show histological features of well-differentiated HCC after resection. Both clinicians and pathologists have to be aware of the limitations of biopsy diagnosis. Very well differentiated HCCs are not diagnosed by biopsy because stromal invasion is hardly detectable.

In case of “benign liver tissue” or “borderline lesion,” re-biopsy is recommended if at all feasible.

In addition to the morphological criteria, some attempts have been made recently to utilize immunohistochemical markers for the diagnosis of well-differentiated HCCs [25–31]. Heat shock protein 70 (HSP70) [25, 26], glypican 3 (GPC3) [25, 27–29], and glutamine synthetase (GS) [25, 30, 31] have been used independently or in combination. These markers can be useful for the diagnosis of difficult lesions.

Developmental process of HCCs from early stage to advanced stage

The reason for early HCC to show indistinct (vague) nodular pattern

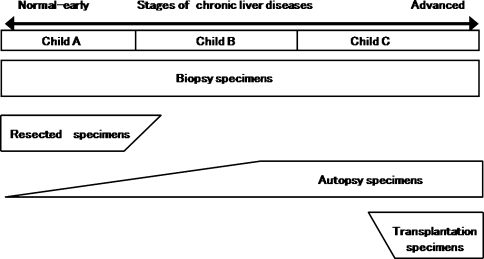

Before describing the developmental process of HCCs, the reason why an early HCC shows a vague (indistinct) nodular pattern needs an explanation. It has not been explained well so far. The author have been frequently asked about this reason, especially by western pathologists. The reason is based on the stages of liver diseases of noncancerous livers. Figure 6 shows the stages of chronic liver diseases and various histological specimens, namely, biopsy, resection, autopsy, and liver transplantation. Biopsy specimens are obtained from the liver of all stages of liver diseases. In contrast, resected specimens are obtained only from the liver with early stages of chronic liver diseases. The clinical stage of the liver corresponds to Child-Pugh classification A (Child A) [32, 33]. Although patients with cirrhosis are also included, they include patients with early-stage cirrhosis. Autopsy specimens are obtained from the liver of all stages of liver diseases. However, many of the autopsy specimens show advanced cirrhosis. In cases of liver transplantation for hepatic insufficiency patients, specimens are obtained only from the liver with advanced cirrhosis. Such advanced cirrhosis corresponds to the stage of Child C.

Fig. 6.

Stages of chronic liver diseases (chronic hepatitis, cirrhosis) and histological specimens (biopsy, resection, autopsy, and transplantation)

In case of an early HCC in a Child A cirrhotic, the noncancerous liver does not have advanced cirrhosis (Fig. 1a, b). The HCC lesion shows an indistinct (vague) margin. This indistinctness is caused by the similarity of the structures of well-differentiated HCC and noncancerous tissue and the absence of a fibrous capsule. Because they can intermingle with each other in the marginal area, the margin is indistinct. Because fibrous septa of cirrhosis are not developed, well-differentiated HCC can grow without deforming or shifting pre-existing portal tracts. However, on microscopic examination, stromal invasion is found as evidence of malignancy. The macroscopic and histological features of early HCC with indistinct margins are thought to be present in such a process. In a Child C liver stage with advanced cirrhosis, the margin of the well-differentiated HCC are not indistinct (Fig. 1c, d). Because of advanced cirrhosis, HCC cannot mix with noncancerous tissue. This could be the reason why indistinct nodular HCCs are rarely found in autopsied or transplanted cases of hepatic insufficiency.

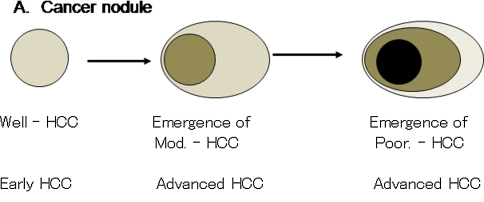

Histological changes of HCC in the developmental process from early stage to advanced stage

The developmental process of HCC is simple when considering only the histological type of cancer tissues (Fig. 7). Early HCC shows only well-differentiated features with mild cytological atypia and no or minimal trabecular thickening [1–11, 34]. During the developmental process, moderately differentiated HCC emerges within the cancer nodule of well-differentiated HCC [35]. This is followed by the emergence of poorly differentiated HCC. The moderate and poorly differentiated HCCs show apparent cytological atypia and definite trabecular thickening. Because such thickened trabecular structure cannot mix with noncancerous tissue, advanced HCCs show distinct margin even in a liver with an early stage of chronic liver disease. Various tumor markers, that is, HSP70, GPC3, and GS, also show incrementally more intense expression from early to advanced HCCs [25–31]. Vascularities of the tumors also change according to tumor development. Early HCCs of the well-differentiated type usually show a hypovascular pattern, and advanced HCCs with a moderately or poorly differentiated type show a hypervascular pattern [36, 37].

Fig. 7.

Developmental process of hepatocellular carcinoma

In addition, the stages of chronic liver disease of noncancerous tissue are also important when considering the developmental process of HCCs.

In cases with advanced cirrhosis, the areas of moderate or poorly differentiated HCCs are larger than HCCs with less advanced liver disease (Fig. 1). Well-differentiated HCCs cannot grow easily because well-developed fibrous septa are obstacles for their growth (Fig. 1c, d). Moderately and poorly differentiated HCCs share larger areas in the cancer nodule. In such advanced HCCs, stromal invasion shows a crossing pattern (Fig. 3a) that severely deforms and shifts the pre-existing fibrous septa. In cases with early stage of chronic liver disease, well-differentiated HCC can grow larger because there is no need to deform such pre-existing fibrous tissue. The developmental process, or tumor growth, of HCCs in livers with early and advanced stages of chronic liver disease is summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Developmental process of HCCs

| HCC in a liver with early stage of chronic liver disease | HCC in a liver with advanced stage of chronic liver disease |

|---|---|

| Well HCC > Mod/Poor HCC | Well HCC < Mod/Poor HCC |

| Indistinct nodular pattern | Distinct nodular pattern |

| HCC can grow without deforming pre-existing fibrous stroma | HCC grows with deforming thick fibrous stroma |

| Stromal invasion: Well HCC vs. pre-existing portal tracts | Stromal invasion: Mod. Poor HCC vs. thickened fibrous septa |

Comparison of stages of chronic liver diseases of non-cancerous tissue

HCC: hepatocellular carcinoma, Well: well differentiated, Mod.: moderately differentiated, Poor: poorly differentiated

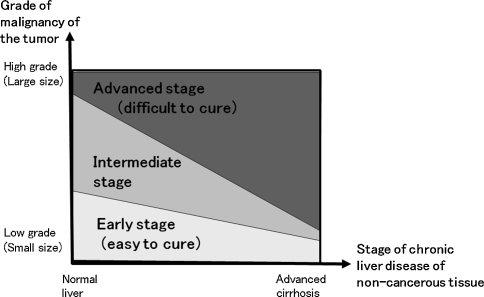

Clinical stage (curability) of HCC patients

Finally, the clinical stage (curability) of the HCC patients should be considered from the pathologist’s and the clinician’s perspectives.

Pathologists should evaluate the histological features of noncancerous liver tissue, as well as the cancer tissue itself, because noncancerous tissue is closely related to the gross features of HCC and its developmental process. Both the grade of malignancy of the tumor itself and the stage of the chronic liver disease of noncancerous tissue influence the curability or prognosis of the patient. As shown in Fig. 8, the clinical stage (curability, prognosis) can be classified by the slanted lines. This concept corresponds well with the clinical classification that evaluates both the grade of malignancy of HCC and the function of noncancerous liver, that is, BCLC staging system, CLIP score, and JIS score [38–40].

Fig. 8.

Clinical stage (curability) of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). The clinical stage (or curability) of HCC should be estimated by evaluating both the grade of malignancy of the cancer nodule and the stage of chronic liver disease of noncancerous tissue

From this point of view, early HCCs with an indistinct margin are true HCCs with early stage and good prognosis. Their grade of malignancy is low and the noncancerous liver tissue is in the early stage of chronic liver disease. In addition, small HCCs with purely well-differentiated features in advanced cirrhosis can also be another type of early HCCs even if they have a distinct margin. This needs to be discussed in future studies.

Finally, the author sincerely hopes that this article will help in daily practical clinical application and better understanding of early HCCs.

Footnotes

Some parts of this article were presented at the meeting of the International Consensus Group for Hepatocellular Neoplasia (ICGHN) held at Kurume University Medical School, Kurume, Japan, in 2002, and at the University of Leuven, Belgium, in 2004.

References

- 1.Liver Cancer Study Group of Japan. The General Rules of the Clinical and Pathological Study of Primary Liver Cancer. 5th ed. Tokyo: Kanehara; 2008

- 2.Sakamoto M, Hirohashi S, Shimosato Y. Early stages of multistep hepatocarcinogenesis: adenomatous hyperplasia and early hepatocellular carcinoma. Hum Pathol. 1991;22:172–178. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(91)90039-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kenmochi K, Sugihara S, Kojiro M. Relationship of histologic grade of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) to tumor size, and demonstration of tumor cells of multiple different grades in single small HCC. Liver. 1987;7:18–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0676.1987.tb00310.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kondo F, Hirooka N, Wada K, Kondo Y. Morphological clues for the diagnosis of small hepatocellular carcinomas. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histopathol. 1987;411:15–21. doi: 10.1007/BF00734509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nakashima O, Sugihara S, Kage M, Kojiro M. Pathomorphologic characteristics of small hepatocellular carcinoma: a special reference to small hepatocellular carcinoma with indistinct margins. Hepatology. 1995;22:101–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Takayama T, Makuuchi M, Hirohashi S, Sakamoto M, Yamamoto J, Shimada K, et al. Early hepatocellular carcinoma as an entity with a high rate of surgical cure. Hepatology. 1998;28:1241–1246. doi: 10.1002/hep.510280511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kondo F, Ebara M. Early hepatocellular carcinoma; carcinogenesis, morphology and developmental fashion. Shokakika Jpn. 1992;16:409–417. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kondo F, Kondo Y, Ebara M, Ohto M. Biopsy diagnosis of small and well differentiated hepatocellular carcinoma. Pathol Clin Med Jpn. 1993;11:943–951. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kondo F, Wada K, Nagato Y, Nakajima T, Kondo Y, Hirooka N, et al. Biopsy diagnosis of well-differentiated hepatocellular carcinoma based on new morphologic criteria. Hepatology. 1989;9:751–755. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840090516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Terasaki S, Kaneko S, Kobayashi K, Nonomura A, Nakanuma Y. Histological features predicting malignant transformation of nonmalignant hepatocellular nodules: a prospective study. Gastroenterology. 1998;115:1216–1222. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5085(98)70093-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roncalli M. Hepatocellular nodules in cirrhosis: focus on diagnostic criteria on liver biopsy. A Western experience. Liver Transpl 2004;10:S9–S15 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Kutami R, Nakashima Y, Nakashima O, Shiota K, Kojiro M. Pathomorphologic study on the mechanism of fatty change in small hepatocellular carcinoma of humans. J Hepatol. 2000;33:282–289. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8278(00)80369-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kondo Y, Kondo F, Wada K, Okabayashi A. Pathologic features of small hepatocellular carcinoma. Acta Pathol Jpn. 1986;36:1149–1161. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.1986.tb02836.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kondo F, Kondo Y, Nagato Y, Tomizawa M, Wada K. Interstitial tumour cell invasion in small hepatocellular carcinoma. Evaluation in microscopic and low magnification views. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1994;9:604–612. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.1994.tb01569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nakano M, Saito A, Yamamoto M, Doi M, Takasaki K. Stromal and blood vessel wall invasion in well-differentiated hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver. 1997;17:41–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0676.1997.tb00777.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miyao Y, Ozaki D, Nagao T, Kondo Y. Interstitial invasion of well-differentiated hepatocellular carcinoma and subsequent tumor growth. Pathol Int. 1999;49:208–213. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1827.1999.00848.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Park YN, Kojiro M, Di Tommaso L, Dhillon AP, Kondo F, Nakano M, et al. Ductular reaction is helpful in defining early stromal invasion, small hepatocellular carcinomas, and dysplastic nodules. Cancer. 2007;109:915–923. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ohto M, Kondo F, Ebara M. Pathology, diagnosis, and treatment for small liver cancer. In: Tobe T, editor. Primary liver cancer in Japan. Tokyo: Springer-Verlag; 1992. pp. 365–373. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wada K, Kondo F, Kondo Y. Large regenerative nodules and dysplastic nodules in cirrhotic livers: a histopathologic study. Hepatology. 1988;8:1684–1688. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840080636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.International Working Party Terminology of nodular hepatocellular lesions. Hepatology. 1995;22:983–993. doi: 10.1016/0270-9139(95)90324-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kondo F, Ebara M, Sugiura N, Wada K, Kita K, Hirooka N, et al. Histological features and clinical course of large regenerative nodules: evaluation of their precancerous potentiality. Hepatology. 1990;12:592–598. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840120324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Theise ND, Schwartz M, Miller C, Thung SN. Macroregenerative nodules and hepatocellular carcinoma in forty-four sequential adult liver explants with cirrhosis. Hepatology. 1992;16:949–955. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840160416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hytiroglou P, Theise ND, Schwartz M, Mor E, Miller C, Thung SN. Macroregenerative nodules in a series of adult cirrhotic liver explants: issues of classification and nomenclature. Hepatology. 1995;21:703–708. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kondo F, Koshima Y, Ebara M. Nodular lesions associated with abnormal liver circulation. Intervirology. 2004;47:277–287. doi: 10.1159/000078479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Di Tommaso L, Franchi G, Park YN, Fiamengo B, Destro A, Morenghi E, et al. Diagnostic value of HSP70, glypican 3, and glutamine synthetase in hepatocellular nodules in cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2007;45:725–734. doi: 10.1002/hep.21531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chuma M, Sakamoto M, Yamazaki K, Ohta T, Ohki M, Asaka M, et al. Expression profiling in multistage hepatocarcinogenesis: identification of HSP70 as a molecular marker of early hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2003;37:198–207. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Capurro M, Wanless IR, Sherman M, Deboer G, Shi W, Miyoshi E, et al. Glypican-3: a novel serum and histochemical marker for hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:89–97. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5085(03)00689-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yamauchi N, Watanabe A, Hishinuma M, Ohashi K, Midorikawa Y, Morishita Y, et al. The glypican 3 oncofetal protein is a promising diagnostic marker for hepatocellular carcinoma. Mod Pathol. 2005;18:1591–1598. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Libbrecht L, Severi T, Cassiman D, Vander Borght S, Pirenne J, Nevens F, et al. Glypican-3 expression distinguishes small hepatocellular carcinomas from cirrhosis, dysplastic nodules, and focal nodular hyperplasia-like nodules. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:1405–1411. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000213323.97294.9a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gebhardt R, Tanaka T, Williams GM. Glutamine synthetase heterogeneous expression as a marker for the cellular lineage of preneoplastic and neoplastic liver populations. Carcinogenesis. 1989;10:1917–1923. doi: 10.1093/carcin/10.10.1917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Christa L, Simon MT, Flinois JP, Gebhardt R, Brechot C, Lasserre C. Overexpression of glutamine synthetase in human primary liver cancer. Gastroenterology. 1994;106:1312–1320. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90024-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Child CG. The liver and portal hypertension. MPCS. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1964. p. 50. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pugh RN, Murray-Lyon IM, Dawson JL, Pietroni MC, Williams R. Transection of the oesophagus for bleeding oesophageal varices. Br J Surg. 1973;60:646–649. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800600817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kojiro M, Roskams T. Early hepatocellular carcinoma and dysplastic nodules. Semin Liver Dis. 2005;25:133–142. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-871193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kojiro M. Pathology of early HCC: progression from early to advanced. Hepatogastroenterology. 1998;45:1203–1205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maeda T, Adachi E, Kajiyama K, Takenaka K, Honda H, Sugimachi K, et al. CD34 expression in endothelial cells of small hepatocellular carcinoma: its correlation with tumour progression and angiographic findings. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1995;10:650–654. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.1995.tb01365.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nakashima Y, Nakashima O, Hsia CC, Kojiro M, Tabor E. Vascularization of small hepatocellular carcinomas: correlation with differentiation. Liver. 1999;19:12–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.1999.tb00003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.The Cancer of the Liver Italian Program (CLIP) Investigators A new prognostic system for hepatocellular carcinoma: a retrospective study of 435 patients. Hepatology. 1998;28:751–755. doi: 10.1002/hep.510280322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Llovet JM, Brú C, Bruix J. Prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma: the BCLC staging classification. Semin Liver Dis. 1999;19:329–338. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1007122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kudo M, Chung H, Haji S, Osaki Y, Oka H, Seki T, et al. Validation of a new prognostic staging system for hepatocellular carcinoma: the JIS score compared with the CLIP score. Hepatology. 2004;40:1396–1405. doi: 10.1002/hep.20486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]