Abstract

Summary: Due to the availability of new sequencing technologies, we are now increasingly interested in sequencing closely related strains of existing finished genomes. Recently a number of de novo and mapping-based assemblers have been developed to produce high quality draft genomes from new sequencing technology reads. New tools are necessary to take contigs from a draft assembly through to a fully contiguated genome sequence. ABACAS is intended as a tool to rapidly contiguate (align, order, orientate), visualize and design primers to close gaps on shotgun assembled contigs based on a reference sequence. The input to ABACAS is a set of contigs which will be aligned to the reference genome, ordered and orientated, visualized in the ACT comparative browser, and optimal primer sequences are automatically generated.

Availability and Implementation: ABACAS is implemented in Perl and is freely available for download from http://abacas.sourceforge.net

Contact: sa4@sanger.ac.uk

1 INTRODUCTION

The recent development of ultra high-throughput sequencing technologies has led to a huge increase in the number of genome sequencing projects being carried out (Mardis and Elaine, 2008). For small genomes, it is now possible to obtain high sequencing coverage with a single run of a new sequencing machine. Therefore there is widespread interest in sequencing large numbers of closely related species or strains where a high quality reference sequence already exists, for instance, to explore population structure and genetic variation. A number of new assemblers have been developed for carrying out both de novo and mapped assemblies from new technology reads (Chaisson et al. 2004; Miller et al. 2008). However, a significant amount of manual intervention is still required to go from a set of contigs to fully contiguated sequence.

The problem of rapidly contiguating draft assemblies has existed since the inception of genome sequencing. A number of tools have previously been developed for this purpose such as Bambus (Pop et al. 2004), BACCardI (Bartels et al. 2005), Projector2 (van Hijum et al. 2005) and OSLay (Richter et al. 2007). Ideally, automatic contiguation programs consist of two major parts; ordering and orientating contigs based on a reference and closing gaps between ordered contigs. Bambus requires users to provide linking information between contigs generated from various methods including mapping of contigs to a related genome. Post processing of the resulting set of scaffolds is required to generate a pseudomolecule and close gaps. BACCardI provides support in genome finishing by scaffolding contigs based on virtual clone maps alongside other features. Projector2 is a web service application for closing gaps in prokaryotic genome assemblies. The most recent tool in the area, OSLay requires a mapping file between a reference (or a set of contigs) and sets of contigs to find synteny. The results could be used as inputs to the assembly viewer Consed (Gordon et al. 1998) to design primers.

ABACAS is a stand alone program intended to rapidly contiguate (align, order, orientate), visualize and design primers to close gaps on shotgun assembled contigs based on a reference sequence. Some of the features of ABACAS include showing ambiguous contigs or overlapping contigs, visualizing repetitive regions, considering base qualities of contigs for primer design and enabling users to drag and drop contigs.

2 METHODS

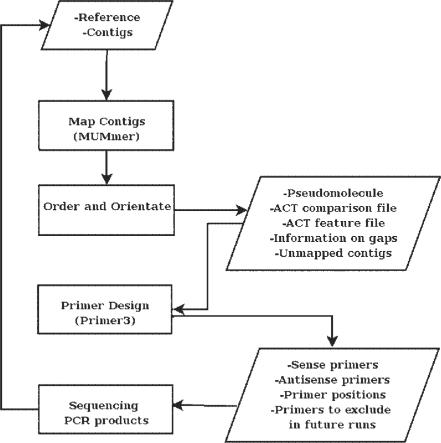

Figure 1 describes the overall pipeline implemented in ABACAS. It uses MUMmer (Kurtz et al. 2004) to find alignment positions and identify areas of synteny of the contigs against the reference. The output is then processed to generate a pseudomolecule taking overlapping contigs and gaps in to account. MUMmer's alignment programs, Nucmer and Promer, are used followed by the ‘delta-filter’ and ‘show-tiling’ utilities.

Fig. 1.

A flow-chart describing the pipeline implemented in ABACAS.

Gaps in the pseudomolecule are represented by N's. ABACAS automatically extracts gaps on the pseudomolecule and, based on flanking sequences above a base quality threshold, designs primers for gap closure using Primer3 (Koressaar and Remm 2007). As part of the primer design step the uniqueness of the sequence is checked by running a sensitive NUCmer alignment. ABACAS allows users to adjust parameters such as melting temperature, size, flanking region and size of contig ends to exclude from picking primers. It then produces a list of sense and antisense primer oligos as well as a detailed Primer3 output that contains additional information on each gap position.

ABACAS generates a comparison file that can be used to visualize ordered and oriented contigs in ACT, the Artemis Comparison Tool (Carver et al. 2008). Synteny is represented by red bars where colour intensity decreases with lower values of percent identity between comparable blocks. Information on contigs such as the orientation, percent identity, coverage and overlap with other contigs can also be visualized by loading the output feature file on ACT. Contigs that were not mapped can be included separately. Repetitive regions in the reference can also be identified using a MUMmer self-comparison and visualized in ACT alongside quality of the contigs.

If all of the contigs are not mapped, there is an option to run tBLASTx (Altschul et al. 1997) on contigs that are not included in the pseudomolecule using sequences from the reference that correspond to the gaps. Additional contigs to the pseudomolecule can be dragged and dropped to the correct position using ACT.

3 IMPLEMENTATON

ABACAS is implemented in Perl and requires MUMmer and (optionally) BLAST installed on the local machine. The user supplies a FASTA file of contigs and a reference genome in FASTA format. As the program can be used in an iterative process of contiguating a genome sequence, the output files produced after each running of the program can be fed back into the program as input.

4 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

ABACAS has already been used on a number of eukaryote and prokaryote genome projects at the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute. Prokaryote genome projects include Escherichia coli 8178, Escherichia coli K88, Escherichia coli K99, Yersinia enterocolitica—five biotypes, Clostridium difficle and Mycobacterium canetti. It is also being used to finish a number of eukaryote genomes of Babesia bigemina (four chromosomes), Trypanosoma vivax (11 chromosomes) and Plasmodium Berghei (14 chromosomes). To give a quantitative example of the results, in the Plasmodium berghei chromosome 2 finishing effort, the number of contigs was reduced from 60 to 36 with nine potential joins via ABACAS. Forty-six PCR products were generated to close gaps and 38 of these were successful in closing gaps in the assembly. In C. difficle cdbi1, the initial number of contigs larger than 2 kb was reduced from 37 to 10 after PCR and primer walks. On the other hand, the six contigs of C. difficle cd196 were contiguated to a single contig based on primers suggested by ABACAS. The main difference compared to existing tools is the possibility to include ABACAS in a high-throughput automated workflow. In summary, ABACAS is primarily used in post-assembly applications as a finishing tool. It is used both to generate high quality reference-based genome scaffolds and to assist finishing efforts by directing primer design. At the Sanger institute, ABACAS has been included in the production pipeline to automatically finish draft assemblies. Ongoing work includes improving mapping of contigs in highly divergent species.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Andrew Berry, Mandy Sanders, and Danielle Walker of the Pathogen Genomics group at the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute who provided feedback on earlier versions of the program.

Funding: Wellcome Trust [grant number WT085775/Z/08/Z]; and European Union 6th Framework Program grant to the BioMalPar Consortium [grant number LSHP-LT-2004-503578].

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- Altschul SF, et al. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartels D, et al. BACCardI–a tool for the validation of genomic assemblies, assisting genome finishing and intergenome comparison. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:853–859. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver T, et al. Artemis and ACT: viewing, annotation and comparing sequences stored in relational database. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:2672–2676. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaisson, et al. Fragment assembly with short reads. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:2067–2074. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon D, et al. Consed: a graphical tool for sequence finishing. Genome Res. 1998;8:195–202. doi: 10.1101/gr.8.3.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koressaar T, Remm M. Enhancements and modifications of primer design program Primer3. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:1289–1291. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurtz S, et al. Versatile and open software for comparing large genomes. Genome Biol. 2004;5:R12. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-2-r12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mardis , Elaine R. The impact of next-generation sequencing technology on genetics. Trends Genet. 2008;24:133–141. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2007.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller, et al. Aggressive assembly of pyrosequencing reads with mates. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:2818–2824. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pop M, et al. Hierarchical scaffolding with Bambus. Genome Res. 2004;14:149–159. doi: 10.1101/gr.1536204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter DC, et al. OSLay: optimal syntenic layout of unfinished assemblies. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:1573–1579. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Hijum SA, et al. Projector 2: contig mapping for efficient gap-closure of prokaryotic genome sequence assemblies. Nucleic Acid Res. 2005;33(Web Server issues):W560–W566. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]