Abstract

Background and Aims

Halophytic species often show seed dimorphism, where seed morphs produced by a single individual may differ in germination characteristics. Particular morphs are adapted to different windows of opportunity for germination in the seasonally fluctuating and heterogeneous salt-marsh environment. The possibility that plants derived from the two morphs may also differ physiologically has not been investigated previously.

Methods

Experiments were designed to investigate the germination characteristics of black and brown seed morphs of Suaeda splendens, an annual, C4 shrub of non-tidal, saline steppes. The resulting seedlings were transferred to hydroponic culture to investigate their growth and photosynthetic (PSII photochemistry and gas exchange) responses to salinity.

Key Results

Black seeds germinated at low salinity but were particularly sensitive to increasing salt concentrations, and strongly inhibited by light. Brown seeds were unaffected by light, able to germinate at higher salinities and generally germinated more rapidly. Ungerminated black seeds maintained viability for longer than brown ones, particularly at high salinity. Seedlings derived from both seed morphs grew well at high salinity (400 mol m−3 NaCl). However, seedlings derived from brown seeds performed poorly at low salinity, as reflected in relative growth rate, numbers of branches produced, Fv/Fm and net rate of CO2 assimilation.

Conclusions

The seeds most likely to germinate at high salinity in the Mediterranean summer (brown ones) retain a requirement for higher salinity as seedlings that might be of adaptive value. On the other hand, black seeds, which are likely to delay germination until lower salinity prevails, produce seedlings that are less sensitive to salinity. It is not clear why performance at low salinity, later in the life cycle, might have been sacrificed by the brown seeds, to achieve higher fitness at the germination stage under high salinity. Analyses of adaptive syndromes associated with seed dimorphism may need to take account of differences over the entire life cycle, rather than just at the germination stage.

Key words: Chlorophyll fluorescence, germination, growth rate, halophyte, photosynthesis, photosystem II, salt tolerance, seed dimorphism, seed viability, Suaeda splendens

INTRODUCTION

Seed dimorphism provides plants with alternative strategies for survival in variable or heterogeneous environments (Khan et al., 2001a, b). Typically, the two seed morphs may show different degrees of dormancy and different germination responses to environmental factors, apart from possible differences in size and morphology. Seed dimorphism is particularly common in halophytes, which can experience considerable spatial and temporal variation in the salinity of their environments (Khan and Ungar, 2001, Khan et al., 2001a, 2004; Li et al., 2005). Germination is a stage in the life cycle of halophytes that can be particularly affected by elevated salt concentrations. Consequently, there has been much interest in the differential germination responses of dimorphic seeds to salinity and the extent to which such differences represent mechanisms for avoidance or tolerance of episodes of high salinity.

Established halophytic plants also show distinctive morphological and physiological adaptations to their saline environments. Much work has focused on understanding how growth, photosynthesis, ion relations and water relations respond to elevated salinity in order to maintain fitness under such extreme conditions. Measurements of photosynthetic gas exchange and associated chlorophyll fluorescence characteristics have revealed that species vary both in their salinity tolerance and the mechanisms by which they achieve it. For instance, the extreme halophyte Sarcocornia fruticosa showed its fastest growth at sea-water salinity because increased photosynthetic area more than compensated for declining stomatal conductance (Redondo-Gomez et al., 2006), whereas the salt-marsh hygrohalophyte Atriplex portulacoides grew best at about half this salinity as it could not maintain leaf area or stomatal conductance at higher salinities (Redondo-Gomez et al., 2007a). Growth and photosynthetic responses of several Suaeda species to increasing NaCl concentrations have been examined (Khan et al., 2000; Lu et al., 2002; Cherian and Reddy, 2003; Mori et al., 2006). A possibility that appears not to have been addressed previously is whether plants derived from different seed morphs might maintain differences in their physiological responses to salinity.

Suaeda splendens is a C4, leaf-succulent species (Shomer-Ilan et al., 1981) in the Chenopodiaceae. Although annual, it can form a small shrub that is normally found on non-tidal saline steppes, or near the upper limits of the tidal range, but is never found in sites directly bathed with seawater (Pedrol and Castroviejo, 1990). Suaeda splendens produces dimorphic seeds: brown seeds (approx. 1·4 mm wide) and black seeds (approx. 0·8 mm wide). The brown seed type has not been described previously in this species, although similar polymorphism has been associated with different germination behaviour in other Suaeda species: S. depressa (Williams and Ungar, 1972), S. fruticosa (Khan and Ungar, 1998), S. maritima (Boucaud and Ungar, 1976), S. japonica (Yokoishi and Tanimoto, 1994), S. moquinii (Khan et al., 2001a) and S. salsa (Li et al., 2005).

This study was designed to examine, first, whether the two seed morphs of S. splendens displayed differences in their germination behaviour and, secondly, whether plants derived from the two morphs showed different physiological responses to salinity. Hence the objectives of this study were: (1) to investigate the germination of black and brown seeds in relation to salinity and light; (2) compare the effects of salinity on growth of plants from both morphs; and (3) to determine the extent to which effects on the photosynthetic apparatus [photosystem II (PSII) photochemistry] and gas exchange characteristics determine plant performance with increasing salinity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant material

Black and brown seeds of Suaeda splendens (Pourret) Gren. & Godr. were collected in October 2005 from ‘Reserva Biológica de Doñana’ (RBD, 37°10′N, 6°21′W; located within Doñana National Park, SW Iberian Peninsula). Fruiting plants were growing on a non-tidal saline steppe that is usually flooded by winter rains during and progressively dries during the spring and summer. Seeds were stored for 4 months in darkness at room temperature and humidity.

Seed germination experiments

In February 2006, an experiment was set up to investigate the effects of salinity on germination. Four replicates of each seed type were exposed to solutions containing 0 (distilled water), 200, 400, 600 and 900 mol m−3 NaCl. Each replicate consisted of 25 seeds placed on filter paper in a 5-cm Petri dish, to which was added 5 mL of the appropriate solution. Dishes were placed in a germinator (ASL Aparatos Científicos M-92004, Spain), and subjected to an alternating diurnal regime of 10 h of light (photon flux rate, 400–700 nm, 35 µmol m−2 s−1) at 15 °C and 14 h of darkness at 5 °C, for 50 d. This temperature regime was chosen to represent the end of autumn temperatures on the steppe, when this species geminates. The dishes were inspected daily and germinated seeds were counted and removed. The water level was adjusted daily with distilled water to avoid changes in salinity due to evaporation. Seed germination was defined as radicle emergence to 1–2 mm.

To investigate the effect of darkness on germination and whether high salinities inhibit or damage the seeds, another set of Petri dishes was wrapped in aluminium foil to exclude light and these were placed in the same incubator. Subsequently, the residual ability to germinate of seeds remaining ungerminated in these treatments was assessed after the removal of salt stress. However, it was evident from the first experiment that both light and salinity inhibited germination and so both perceived limitations were alleviated simultaneously, to data obtain comparable with that experiment. Thus after 30 d in continuous dark, ungerminated seeds were transferred to new Petri dishes containing 5 mL of distilled water and these were returned to the incubator under diurnally alternating light conditions for a further 35 d. Germinated seeds were counted and removed daily during this period.

Three characteristics of germination were determined: final germination percentage, number of days to first germination, mean time-to-germination (MTG; see Table 1 for full list of abbreviations used in the text). MTG was calculating using the equation:

|

1 |

where n is the number of seeds germinated at day i; d is the incubation period in days and N is the total number of seeds germinated in the treatment (Redondo-Gómez et al., 2007b).

Table 1.

Abbreviations used in the text

| Abbreviation | Definition |

|---|---|

| A | Net photosynthetic rate |

| Ci | Intercellular CO2 concentration |

| F0 | Minimal fluorescence level in the dark-adapted state |

| Fm | Maximal fluorescence level in the dark-adapted state |

| Fs | Steady-state fluorescence yield |

| Fv | Variable fluorescence level in the dark-adapted state |

| Fv/Fm | Maximum quantum efficiency of PSII photochemistry |

| ΦPSII | Quantum efficiency of PSII |

| gs | Stomatal conductance |

| MTG | Mean time-to-germinatation |

| NPQ | Non-photochemical quenching |

| PSII | Photosystem II |

| RGR | Relative growth rate |

| WUE | Water-use efficiency |

The viability of the embryo of all seeds that had not germinated in these experimental treatments was determined using the tetrazolium test to assess the effects of seed ageing. The viability of residual seeds from the diurnal light treatments represented seeds 5 months after collection; those from the dark/recovery treatment represented seed 6 months old; further batches were set up at the same range of salinities (for 30 d in the dark) after dry storage (in the dark at room temperature) for 6, 7, 8 and 9 months to give the total viability of 7-, 8-, 9- and 10-month-old seeds, respectively.

All seeds for tetrazolium testing were soaked in distilled water at 25 °C for 16 h. Then they were incubated in a 1 % aqueous solution of 2,3,5-triphenyl-tetrazolium chloride, at pH 7, in the dark at 25 °C for 24 h. Subsequently, seeds were dissected and staining of the embryo was assessed with a magnifying glass (Bradbeer, 1998).

Seedling salinity tolerance experiment

Germinated seeds from the initial germination experiment were transferred to individual plastic pots (6 cm in diameter and 10 cm high), filled with perlite, and placed in a glasshouse at a controlled temperature of 21–25 °C, 40–60 % relative humidity and natural daylight (maximum light flux: 1000 µmol m−2 s−1). Salinity treatments of 0, 200 and 400 mol m−3 NaCl were established using 20 % modified Hoagland's solution (Hoagland and Arnon, 1938) as a base. Then seedlings were allocated to salinities the same as those they had germinated under. Distilled water was the source of water used for 20 % modified Hoagland's solution. Salinity concentrations higher than 400 mol m−3 NaCl were not used because insufficient seeds had germinated at 600 and 900 mol m−3 NaCl to maintain these treatments. At the time seedlings were transplanted, the solutions were placed in plastic trays, to a depth of 1 cm, in the glasshouse and the plastic pots distributed randomly among the trays. Eight pots with plants derived from each seed morph were placed in a single tray at each salinity. During the experiment, the levels in the trays were monitored and they were topped up to the marked level with 20 % Hoagland's solution (without NaCl) whenever necessary to maintain the salt concentration. In addition, the entire solution (including NaCl) was changed every 2 weeks.

Physiological measurements (gas exchange, chlorophyll fluorescence and water content) were made on the youngest fully expanded leaves in June 2006, 5 d before harvest, when the plants appeared to have stable growth rates.

Growth analysis

At the beginning of the experiment five pots with seedlings from each seed type were harvested and dried at 80 °C for 48 h, before weighing. After 4 months (134 d), the eight plants of each seedling type from each salinity treatment were harvested; numbers of primary and secondary branches were recorded and then plants were dried and weighed. Relative growth rate (RGR, g g−1d−1) of whole-plant dry mass was calculated using the formula:

|

2 |

where Mfinal = final dry mass, Minitial = initial dry mass and t = duration of experiment (days).

Leaf water content

Leaf water content (LWC) was calculated as:

|

3 |

where Mfresh is the fresh mass of the leaves, and Mdry is the dry mass after oven-drying at 80 °C for 48 h (Medrano and Flexas, 2004).

Chlorophyll fluorescence

Chlorophyll fluorescence was measured in randomly selected, fully expanded leaves using a portable modulated fluorimeter (FMS-2, Hansatech Instruments Ltd, UK). Measurements were made on five plants chosen randomly from the eight of each type in each treatment (i.e. derived from brown or black seeds, at three salinity treatments: 0, 200 and 400 mol m−3 NaCl). Light and dark-adapted fluorescence parameters were measured at mid-day (1400 µmol m−2 s−1) to investigate whether salt concentration affected the sensitivity of plants to photoinhibition (Qiu et al., 2003).

Plants were dark-adapted for 30 min, using leaf-clips designed for this purpose. The minimal fluorescence level in the dark-adapted state (F0) was measured using a modulated pulse (<0·05 µmol m−2 s−1 for 1·8 µs) too small to induce significant physiological changes in the plant (Schreiber et al., 1986). The data stored was an average taken over a 1·6-s period. Maximal fluorescence in this state (Fm) was measured after applying a saturating light pulse of 15 000 µmol m−2 s−1 for 0·7 s (Bolhàr-Nordenkampf and Öquist, 1993). The value of Fm was recorded as the highest average of two consecutive points. Values of the variable fluorescence (Fv = Fm–F0) and maximum quantum efficiency of PSII photochemistry (Fv/Fm) were calculated from F0 and Fm. This ratio of variable to maximal fluorescence correlates with the number of functional PSII reaction centres and dark-adapted values of Fv/Fm can be used to quantify photoinhibition (Maxwell and Johnson, 2000).

The same surface of each plant was used to measure light-adapted parameters. Steady-state fluorescence yield (Fs) was recorded after adapting plants to ambient light conditions for 30 min. A saturating actinic light pulse of 15000 µmol m−2 s−1 for 0·7 s was then used to produce the maximum fluorescence yield (Fm′) by temporarily inhibiting PSII photochemistry.

Using fluorescence parameters determined in both light- and dark-adapted states, the following were calculated: quantum efficiency of PSII [ΦPSII = (Fm′–Fs)/Fm′] (Genty et al., 1989) and non-photochemical quenching [NPQ = (Fm–Fm′)/Fm′] (Schreiber et al., 1986).

Gas exchange

Gas exchange measurements were made at mid-day on randomly selected, fully expanded leaves of the same five plants, using an infrared gas analyser in an open system (LCi; Analytical Development Company Ltd, Hoddesdon, UK). Net photosynthetic rate (A), intercellular CO2 concentration (Ci) and stomatal conductance (gs) to CO2 were determined at an ambient CO2 concentration of 360 µmol mol−1, temperature of 25/28 °C, 50 ± 5 % relative humidity and a photon flux density of 1000 µmol m−2 s−1. A, Ci and gs were calculated using the standard formulae of von Caemmerer and Farquhar (1981). Photosynthetic area was calculated using a scanner and the program ‘midebmp.exe’. The water-use efficiency (WUE) was calculated as the ratio between A and transpiration rate [mmol (CO2 assimilated) mol−1 (H2O transpired)].

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was carried out using Statistica v. 6·0 (Statsoft Inc.). Pearson coefficients were calculated to assess correlation between different variables. Data were analysed using Student's t-test for independent samples and one-, two- and three-way analysis of variance (F-test). Data were first tested for normality with the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test and for homogeneity of variance with the Brown–Forsythe test and arc-sine transformed (germination data) in order to normalize the error distribution for ANOVA. Significant test results were followed by Tukey's test for identification of important contrasts.

RESULTS

Seed germination and salinity

Salinity progressively decreased the final germination percentage of both seed morphs of S. splendens under the diurnally alternating light regime, with little germination above a NaCl concentration of 400 mol m−3 (Table 2). Nevertheless all seeds of both seed morphs imbibed, despite the black seed coats being harder than brown ones. Germination in the absence of NaCl or at low salinity (200 mol m−3) was considerably higher in black seeds than brown ones (t6 = 6·6, P < 0·001 and t6 = 6·0, P < 0·001, respectively). The suppression of germination by salinity was significantly less in the brown seeds (seed morph × salinity interaction in two-way ANOVA: F = 4·0, P < 0·05).

Table 2.

Final germination (%), days to first germination and mean time-to-germination (MTG) for black and brown seed morphs of Suaeda splendens, in five NaCl treatments, under diurnally alternating photoperiod and temperature (10 h dark at 5 °C/14 h light at 15 °C) after 50 d

| Germination characteristics |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seed type | NaCl treatment (mol m−3) | Final germination ( %) | First germination (d) | MTG (d) |

| Black | 0 | 94 ± 2·6a | 14 ± 0·8a | 18 ± 0·5a |

| 200 | 82 ± 2·6a | 19 ± 1·7ab | 26 ± 2·0b | |

| 400 | 13 ± 5·7b | 26 ± 3·2bc | 36 ± 1·1c | |

| 600 | 2 ± 2·0bc | 39 ± 0·0c | 39 ± 0·0c | |

| 900 | 0 ± 0·0c | – | – | |

| Brown | 0 | 37 ± 4·7a | 2 ± 0·5a | 10 ± 1·7a |

| 200 | 26 ± 5·3ab | 5 ± 1·2ab | 16 ± 2·7ab | |

| 400 | 31 ± 3·0ab | 11 ± 0·6b | 19 ± 2·1abc | |

| 600 | 8 ± 2·8b | 23 ± 3·6c | 27 ± 4·8bc | |

| 900 | 1 ± 1·0b | 41 ± 0·0d | 41 ± 0·0c | |

Values are means ± s.e (n = 4). Different letters indicate treatment means for each characteristic that are significantly different (Tukey test; P < 0·05).

Speed of germination, expressed either as time to first germination or mean time-to-germination (MTG) decreased with salinity in diurnally alternating light (Table 2). Both measures were significantly correlated with salinity for both seed morphs: first germination of black seeds, r = 0·90 (P < 0·0001); MTG of black seeds, r = 0·95 (P < 0·0001); first germination of brown seeds, r = 0·94 (P < 0·0001); MTG of brown seeds, r = 0·88 (P < 0·0001).

After 30 d of continuous darkness and exposure to the salinity pre-treatments (Table 3), brown seeds had achieved significantly higher total germination than black ones, in contrast to the results in the light. Germination of both seed morphs was again reduced by increasing salinity, although brown seeds were significantly less affected by salinity than black ones in darkness (two-way ANOVA: morphs, F1,30 = 453·3, P < 0·0001; salinity, F4,30 = 248·4, P < 0·0001; interaction, F4,30 = 53·3, P < 0·0001). Black seeds showed no germination above a NaCl concentration of 200 mol m−3, whereas brown ones germinated up to 600 mol m−3.

Table 3.

Germination characteristics of black and brown seed morphs of Suaeda splendens after five different NaCl treatments

| Germination characteristics |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seed type | NaCl treatment (mol m−3) | Dark germination ( %) | Additional germination ( %) | First germination (d) | MTG (d) | Final germination ( %) |

| Black | 0 | 10 ± 2·0a | 74 ± 5·0 | 7 ± 2·3 | 15 ± 0·8 | 84 ± 5·2 |

| 200 | 7 ± 1·9a | 84 ± 4·9 | 8 ± 2·0 | 15 ± 1·6 | 91 ± 4·1 | |

| 400 | 0 ± 0·0b | 94 ± 8·3 | 8 ± 1·3 | 15 ± 0·7 | 94 ± 8·3 | |

| 600 | 0 ± 0·0b | 95 ± 5·3 | 10 ± 0·8 | 15 ± 0·5 | 95 ± 5·3 | |

| 900 | 0 ± 0·0b | 95 ± 6·4 | 9 ± 0·7 | 14 ± 0·7 | 95 ± 6·4 | |

| Brown | 0 | 40 ± 1·6a | 12 ± 6·9 | 2 ± 0·3 | 7 ± 2·4 | 52 ± 7·1 |

| 200 | 30 ± 2·0ab | 14 ± 5·3 | 3 ± 0·6 | 11 ± 2·5 | 44 ± 4·3 | |

| 400 | 24 ± 1·6b | 25 ± 5·3 | 1 ± 0·0 | 10 ± 0·7 | 49 ± 6·6 | |

| 600 | 5 ± 1·0c | 37 ± 3·4 | 1 ± 0·2 | 8 ± 1·7 | 42 ± 3·5 | |

| 900 | 0 ± 0·0d | 37 ± 5·0 | 2 ± 0·0 | 6 ± 2·1 | 37 ± 5·0 | |

The different NaCl treatments were applied under diurnally alternating temperatures (10 h at 5 °C/14 h 15 °C) in the dark for 30 d. This was followed by transfer to distilled water under alternating temperature and light (10 h dark at 5 °C/14 h light at 15 °C). Germination in darkness ( %), additional germination, days to first germination and mean time-to-germination (MTG), all after transfer to distilled water and alternating light; total germination ( %) = dark germination + additional germination. Different letters indicate treatment means for each characteristic that are significantly different (Tukey test; P < 0·05).

Brown seeds showed similar germination in darkness to that under alternating light and dark. However, the germination of black seeds was considerably inhibited by continuous darkness, an effect that was particularly striking at low salinity (cf. Tables 2 and 3). The three-way ANOVA of the two experiments gave highly significant effects for light (F1,60 = 31·5 P < 0·0001), morphs (F1,60 = 47·2 P < 0·0001), salinity (F4,60 = 99·6 P < 0·0001), light × morphs (F1,60 = 24·75 P < 0·0001), morphs × salinity (F4,60 = 11·48 P < 0·0001), and light × morphs × salinity (F4,60 = 4·15 P < 0·01). The interaction of light × salinity was not significant.

The transfer of ungerminated seeds from salinity treatments in continuous darkness to distilled water in alternating light resulted in considerable further germination. The additional germination was a combination of responses to alleviation of salinity stress and alleviation of inhibition by darkness, particularly in black seeds (cf. Tables 2 and 3). Total germination percentage was independent of initial salinity treatment for both seed morphs (84–96 % for black seeds and 37–54 % for brown seeds), indicating that the earlier salinity effects were the result osmotic inhibition that was reversible. In addition, there was a dramatic increase in germination of the black seeds on transfer to alternating light (Table 3), further evidence of inhibition by continuous darkness in this morph.

Final germination was higher in black seeds than brown ones (Table 3; two-way ANOVA, F1,30 = 172·43 P < 0·0001) but it was not affected by salinity pre-treatment (F4,30 = 1·03, P > 0·05) and neither was the interaction significant (F4,30 = 1·45 P > 0·05). Both the number of days to first germination and MTG were greater for black seeds than brown ones.

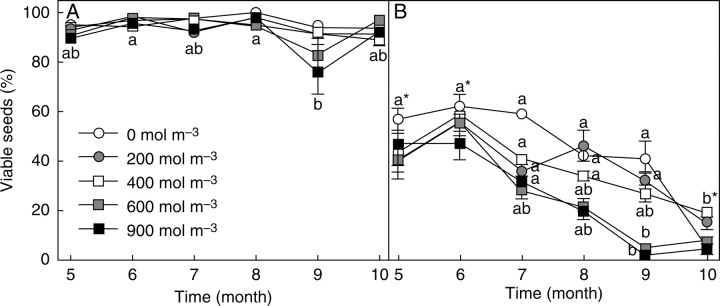

Seed viability after dry storage

The viability of black seeds was maintained at around 90 % and declined only slightly, even after 10 months of dry storage at room temperature and humidity and varied little in response to salinity in the 30-d treatment after this period (Fig. 1). On the other hand, brown seeds had significantly lower viability overall (three-way ANOVA: morphs, F1,180 = 747·91 P < 0·0001) and their viability clearly declined with dry storage time. Hence overall there was significant effect of time (F5,180 = 50·05 P < 0·0001), and the interaction morphs × time was also highly significant (F5,180 = 44·03 P < 0·0001). Viability was further reduced by increasing salinity in the 30-d treatment after dry storage (F4,180 = 16·85 P < 0·0001), especially in the brown seeds. After 9–10 months storage, viability of brown seeds after treatment with 900 mol m−3 was only about 5 %. The resulting interactions were all significant in the three-way ANOVA (morphs × salinity, F4,180 = 14·39 P < 0·0001; time × salinity, F20,180 = 6·41 P < 0·0001; morphs × time × salinity, F20,180 = 5·33 P < 0·0001).

Fig. 1.

Changes in viability with storage time at room temperature and humidity for two seed morphs of Suaeda splendens, subsequently germinated in a range of NaCl treatments for 303 d. (A) Black seeds; (B) brown seeds. Values represent means ± s.e., n = 4 (25 seeds per replicate). Different letters indicate means for any NaCl treatment that are significantly different with time (Tukey test; P < 0·05); * all means at the same time have the same letter. For black seeds only were there significant differences for 900 mol m−3. Viable was defined as all seeds that had germinated at 5/15 °C plus ungerminated ones with a live embryo.

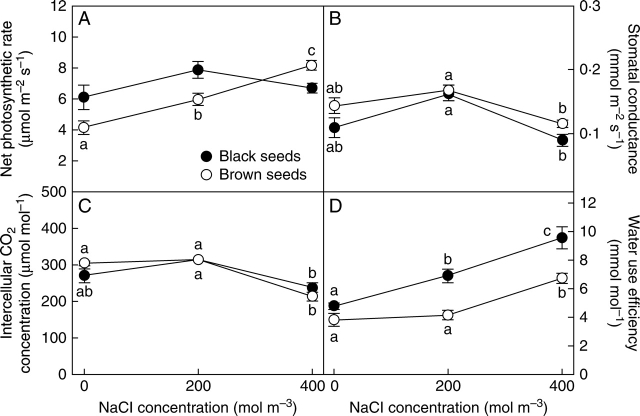

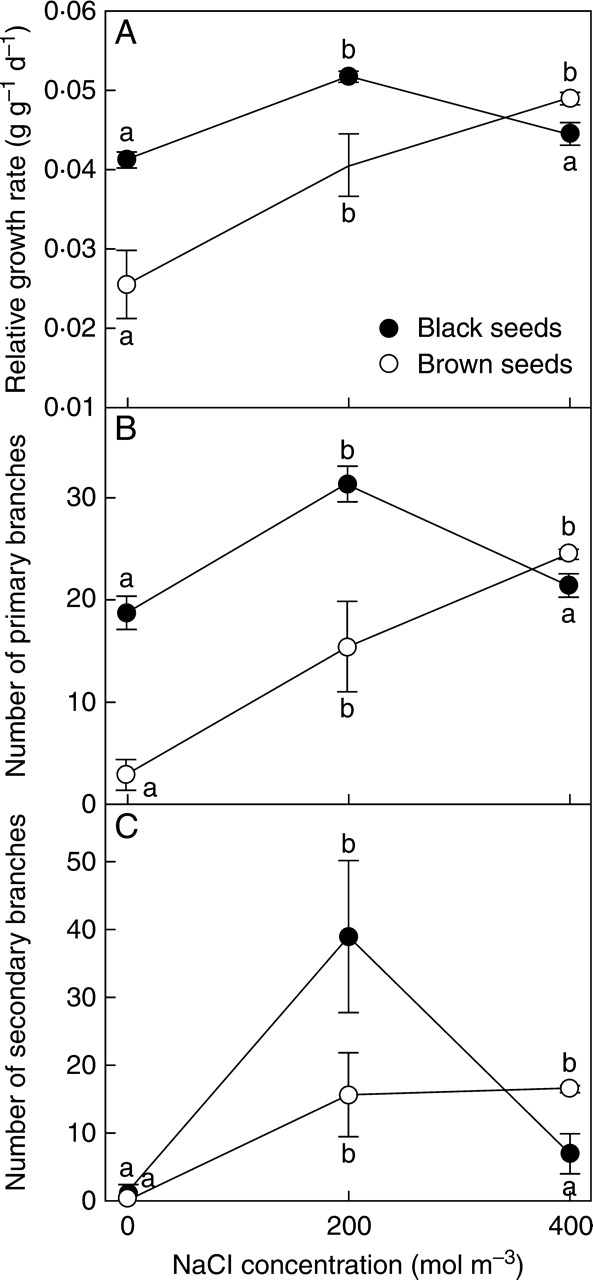

Growth

Plants of S. splendens derived from black and brown seeds responded differently to salinity (Fig. 2A). They showed similar RGRs at 400 mol m−3. However, the growth of plants from brown seeds was progressively impaired by lower salinity (r = 0·73, P < 0·01), whereas plants from black seeds grew fastest at 200 mol m−3 and maintained growth at 0 mol m−3 similar to that at 400 mol m−3. These trends were reflected in significant effects on RGR in two-way ANOVA (morphs, F1,42 = 11·50, P < 0·01; salinity, F2,42 = 18·83, P < 0·0001; morphs × salinity, F2,42 = 6·46, P < 0·01).

Fig. 2.

Growth of Suaeda splendens in response to treatment with a range of NaCl concentrations for 4 months (134 d). (A) Relative growth rate of whole-plant dry mass; (B) number of primary branches; (C) number of secondary branches. Plants grown from black and brown seeds as indicated. Values represent means ± s.e., n = 8. Different letters indicate treatment means for each seed morph that are significantly different from each other (Tukey test; P < 0·05).

The same trends were evident in the number of primary branches produced after 4 months by plants derived from black and brown seeds (Fig. 2B). The effects of seed morph (F = 24·9, P < 0·0001), salinity (F = 22·6, P < 0·0001) and morph × salinity interaction (F = 8·8, P < 0·001) were all highly significant. Number of primary branches was highly correlated with RGR for both black- (r = 0·69, P < 0·0001) and brown-seed origin (r = 0·89, P < 0·0001).

The number of secondary branches produced was not significantly different between seed origins, except at 200 mol m−3, where there was a considerably greater proliferation of branches in plants of black-seed origin.

Water content of plants

Plants derived from black seeds maintained nearly constant leaf water content, irrespective of salinity treatment (approx. 90 %). Plants derived from brown seed behaved similarly at 200 and 400 mol m−3 but their poor performance in the absence of salt was also reflected in a drop in leaf water content to approx. 10 % below that of plants of black-seed origin (t = 3·96, P < 0·01).

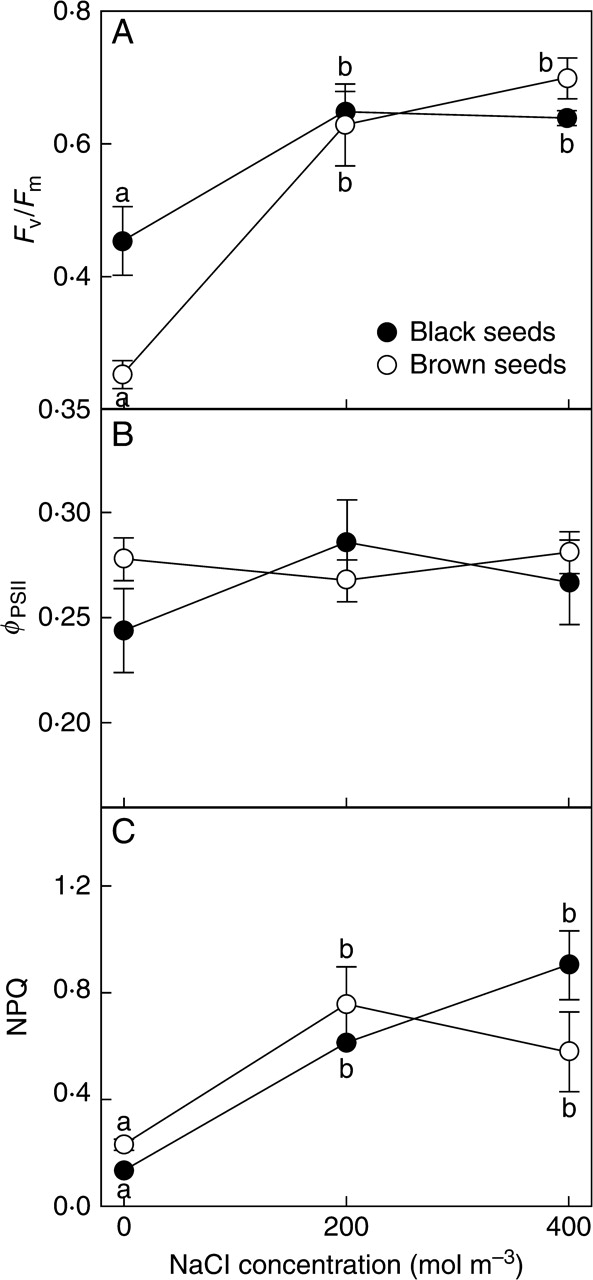

Measurement of chlorophyll fluorescence

Plants derived from black and brown seeds both showed highest maximum quantum efficiency of PSII photochemistry (Fv/Fm) in the presence of salt (200 and 400 mol m−3, with lower values in its absence; Fig. 3A). However, plants of brown-seed origin were more adversely affected by the absence of salt than those of black-seed origin (t8 = 2·92, P < 0·05). In both cases this reduction was mainly the result of lower values of Fm (the values varied around 400 relative fluorescence units (rfu) for plants treated with salt and <300 rfu for plants grown without it)

Fig. 3.

PSII photochemistry of plants derived from two seed morphs of Suaeda splendens in response to treatment with a range of salt concentrations for 4 months. (A) Maximum quantum efficiency of PSII photochemistry (Fv/Fm), (B) quantum efficiency of PSII (ΦPSII) and (C) non-photochemical quenching (NPQ) at midday in randomly selected, fully expanded leaves. Plants grown from black and brown seeds as indicated. Values represent mean ± s.e., n = 5. Different letters indicate treatment means for each seed morph that are significantly different from each other (Tukey test; P < 0·05).

The quantum efficiency of PSII (ΦPSII) was similar for plants derived from the two seed morphs and showed no clear response to salinity treatment (Fig. 3B). NPQ was lowest in plants of both seed origins in the absence of salt (Fig. 3C).

Gas exchange

A in plants derived from black seeds showed little response to salinity treatment (Fig. 4A). In plants derived from brown seeds, values were high at 400 mol m−3 and declined to about 50 % in the absence of salt. In plants of both seeds origins, A was significantly correlated with RGR (r = 0·62, P < 0·05 for each).

Fig. 4.

Gas exchange characteristics of plants derived from two seed morphs of Suaeda splendens in response to treatment with a range of salt concentrations for 4 months. (A) Net photosynthetic rate, (B) stomatal conductance, (C) intercellular CO2 concentration and (D) water use efficiency in randomly selected, fully expanded leaves. Plants grown from black and brown seeds as indicated. Values represent mean ± s.e., n = 5. Different letters indicate treatment means for each seed morph that are significantly different from each other (Tukey test; P < 0·05).

gs was slightly but consistently higher in plants derived from brown seeds (Fig. 4B). gs and Ci (Fig. 4C) were lower at 400 mol m−3 NaCl than in other salt treatments, in plants of both seed origins. Water use efficiency (Fig. 4D) increased significantly with salinity (r = 0·91, P < 0·0001 and r = 0·80, P < 0·001 for plants from black and brown seeds, respectively), and plants derived from black seeds showed consistently higher WUE for all salinity treatments (two-way ANOVA: morphs, F1,22 = 34·4, P < 0·0001; salinity, F2,22 = 38·3, P < 0·0001; morphs × salinity, F2,22 = 2·56, P > 0·05).

DISCUSSION

It is well known that halophytes germinate best in freshwater and their germination is progressively inhibited by external salinity (Baskin and Baskin, 1998); Suaeda splendens proved to be no exception, even though some germination occurred up to a salinity of 900 mol m−3 NaCl. Much of the apparent reduction normally seen represents the enforcement of dormancy by salinity, as seeds remaining ungerminated under saline conditions generally retain the capacity to germinate on transfer to distilled water (Ungar, 1991), and this was again the case for S. splendens. As in Suaeda physophora, inhibition might be attributed to a combination of osmotic stress and ion toxicity (Song et al., 2005).

Seed dimorphism is not unusual in the halophytic Chenopodiaceae, where the two seed morphs produced by a single individual may differ in size, dormancy, germination characteristics and dispersal (Berger, 1985; Khan and Ungar, 1985). Several species of Suaeda produce black and brown seeds on the same plants. In S. splendens, the black seeds germinated readily at low salinity but they were particularly sensitive to increasing salt concentrations and their germination was strongly inhibited by light. The brown seeds, in contrast, were unaffected by light and able to germinate at higher salinities. Furthermore, they generally germinated more rapidly than the black seeds, potentially facilitating faster establishment. Ungerminated black seeds could also maintain higher viability for much longer than the brown ones, particularly when exposed to high levels of salinity. Although brown seeds were less viable overall, the lower germination probably reflected their age at the start of the experiment (4 months), with concomitant loss of viability since maturity.

As in other species, the two morphs appear to be adapted to different windows of opportunity for germination in the seasonally fluctuating and heterogeneous salt marsh environment. It has been demonstrated that seed dimorphism provides an adaptive advantage in saline habitats by providing multiple germination periods that increase chances of survival for at least some seedling cohorts (Khan et al., 2004). Newly produced brown seeds of S. splendens would be more likely to germinate immediately under saline conditions but those not germinating would lose viability fairly quickly. Black seeds, however, would remain dormant in the hypersaline conditions of the Mediterranean summer, when drought is normal, and could germinate after autumn or winter rains alleviate salinity, so long as the seeds remained sufficiently near the surface of the sediment to perceive light. If buried in the sediment, black seeds could have much greater longevity and constitute a seed bank to ensure future survival of the population. These characteristics are similar to those of dimorphic seeds in other halophytic chenopods found in salt marshes and deserts. The desert shrubs S. moquinii of N. America (Khan et al., 2001a) and S. salsa of China (Li et al., 2005) are most similar. Both also produce brown seeds that are more tolerant of salinity for germination than the black ones. The black seeds of S. salsa, at least, require light for germination, especially at higher salinity (Li et al., 2005).

Depending on seed type of origin, the growth of young plants of S. splendens was greatest at 200–400 mol m−3. Such salt stimulation of growth is comparable with results for other halophytic chenopods, including S. fruticosa (Khan et al., 2000), S. salsa (Lu et al., 2002), Atriplex portulacoides (Redondo-Gómez et al., 2007a) and Sarcocornia fruticosa (Redondo-Gómez et al., 2006).

The most remarkable aspect of the findings of these experiments with Suaeda splendens was the apparent carry-over of differential salinity tolerance from seed morph to established seedlings, with its implications for fitness in different environments. Seedlings derived from both seed morphs grew well at salinities close to that of seawater (400 mol m−3 NaCl). It is possible that they would have tolerated higher salinities, had there been sufficient germinated seeds at those salinities to transfer. However, the poor performance at lower external salinity of seedlings derived from brown seeds was particularly striking. This was clearly reflected both in long-term measurements, such as RGR or the numbers of branches produced, and also in shorter-term measurements, including relative water content of the leaves, Fv/Fm and the net rate of CO2 assimilation. Seedlings derived from brown seeds would require an increased uptake of solutes to induce cell expansion, since this maintains the pressure potential in plant tissues, as has been reported by Khan et al. (2000). In dicotyledonous halophytes, water relations and the ability to adjust osmotically are important determinants of the growth response (Munns, 1983). Interestingly, reduced growth of S. salsa in the absence of salt was not associated either with lower leaf water content or any significant effect on PSII photochemistry (Lu et al., 2002), although it is not clear whether these plants had been derived from black or brown seeds.

The RGR of S. splendens and the numbers of primary and secondary branches were significantly correlated with its A. The small reduction in A of plants originating from black seeds at 400 mol m−3 NaCl appeared to be due to a reduction in Ci, which in turn could be explained by the decrease in gs, possibly in response to water stress. In some species exposure to salinity leads to stomatal closure in order to limit transpiration and thus transport of salts (Véry et al., 1998). The resulting lower CO2 diffusion rates limit photosynthetic capacity. However, S. splendens from black seeds showed no decline in leaf water content at higher salinities and it was able to increase water use efficiency, in spite of the decrease in A, through a decrease in gs. Similar results were obtained for Sarcocornia fruticosa by Redondo-Gómez et al. (2006). In plants of S. splendens from brown seeds, similar Ci and gs reductions and an increase of WUE were found at the highest salinity, but these did not correspond with a decrease of CO2 assimilation rate; their maximal A was at 400 mol m−3. Correlations between increases in leaf ion concentrations and reductions in photosynthesis can disappear when considering different leaves, or different salinities (Rawson et al., 1988). In a C4 plant this could be explained by an increase of phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase (PEPCase) activity. The induction of both PEPCase and PEPCase-k activities by salt has been reported in a range of species (Sankhla and Huber, 1974; Amzallag et al., 1990; Li and Chollet, 1994; Echevarría et al., 2001; García Mauriño et al., 2003). Enhanced of PEPCase activity at the highest salinity might explain the disparity between ΦPSII and A in plants from brown seeds. Under laboratory conditions, there is usually a linear relationship between ΦPSII and A (Maxwell and Johnson, 2000) and this was the case for plants from black seeds. Such disparities between A and ΦPSII have been found for Sarcocornia fruticosa and A. portulacoides, although in the case of these C3 halophytes, Redondo-Gómez et al. (2006, 2007a) suggested that it was due to changes in the relative rates of CO2 fixation, photorespiration, nitrogen metabolism and electron donation to oxygen (the Mehler reaction; Fryer et al., 1998).

Reducing the external salinity impaired the maximum quantum efficiency of PSII photochemistry (Fv/Fm) at mid-day and the effect was more severe on plants from brown seeds. In contrast, no such limitation was seen in S. salsa (Lu et al., 2002). This photoinhibition would have been caused by a lower proportion of open reaction centres (lower values of Fm) resulting from a saturation of photosynthesis by light. At the same time NPQ increased for plants from black seeds, indicating that the plants were dissipating light as heat (Maxwell and Johnson, 2000), avoiding over-reduction of the reaction centres of PSII.

A physiological carry-over effect (from seeds to growing plants) appears not to have been reported previously for any halophyte with polymorphic seeds, apart from the tendency of larger seed morphs to produce larger seedlings than small seed morphs (Weiss, 1980; Cheplick and Quinn, 1982; Ellison, 1987). Although black and brown seeds are produced on the same plants of Suaeda splendens, not only do their germination responses differ but they give rise to physiologically different individuals in the next generation. The consequence is that the seeds most likely to germinate at high salinity (i.e. brown ones) retain a requirement for higher salinity as seedlings that may also be of adaptive value. On the other hand, the black seeds, which are more likely to delay germination until lower salinity prevails, produce seedlings that are altogether less sensitive to external salinity. At high salinity, there was little difference between the growth and photosynthesis of the two types of plant; it is not clear why performance at low salinity later in the life cycle might have been sacrificed by the brown seeds, to achieve higher fitness at the germination stage under high salinity. Analyses of the adaptive syndromes or strategies associated with seed dimorphism may need to take account of differences over the entire life cycle, rather than just the more obvious differences at the germination stage.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to Mr F. Fernández-Muñoz for technical assistance. We also thank the Spanish Science and Technology Ministries and the Junta de Andalucía for their support (projects CTM2005-05011 and P06-RNM-01892, respectively).

LITERATURE CITED

- Amzallag GN, Lerner HR, Poljakoff-Mayber A. Exogenous ABA as a modulator of the response of sorghum to high salinity. Journal of Experimental Botany. 1990;41:1529–1534. [Google Scholar]

- Baskin C, Baskin JM. Seeds: ecology, biogeography, and evolution of dormancy and germination. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Berger A. Seed dimorphism and germination behaviour in Salicornia patula. Vegetatio. 1985;61:137–134. [Google Scholar]

- Bolhàr-Nordenkampf HR, Öquist G. Chlorophyll fluorescence as a tool in photosynthesis research. In: Hall DO, Scurlock JMO, Bolhàr-Nordenkampf HR, Leegood RC, Long SP, editors. Photosynthesis and production in a changing environment: a field and laboratory manual. London: Chapman & Hall; 1993. pp. 193–206. [Google Scholar]

- Boucaud J, Ungar IA. Hormonal control of germination under saline conditions of three halophytic taxa in the genus Suaeda. Physiologia Plantarum. 1976;37:143–148. [Google Scholar]

- Bradbeer JW. Seed dormancy and germination. New York, NY: Chapman and Hall; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- von Caemmerer S, Farquhar GD. Some relationships between the biochemistry of photosynthesis and the gas exchange of leaves. Planta. 1981;153:377–387. doi: 10.1007/BF00384257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheplick GP, Quinn JA. Amphicarpium purshii and the ‘pessimistic strategy’ in amphicarpic annuals with subterranean fruits. Oecologia. 1982;52:327–332. doi: 10.1007/BF00367955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherian S, Reddy MP. Evaluation of NaCl tolerance in the callus cultures of Suaeda nudiflora Moq. Biologia Plantarum. 2003;46:193–198. [Google Scholar]

- Echevarría C, García-Mauriño S, Álvarez R, Soler A, Vidal J. Salt stress increases the Ca2+-independent phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase kinase activity in sorghum leaves. Planta. 2001;214:283–287. doi: 10.1007/s004250100616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellison AM. Effects of seed dimorphism on the density-dependent dynamics of experimental populations of Atriplex triangularis (Chenopodiaceae) American Journal of Botany. 1987;74:1280–1288. [Google Scholar]

- Fryer MJ, Andrews JR, Oxborough K, Blowers DA, Baker NR. Relationship between CO2 assimilation, photosynthetic electron transport, and active O2 metabolism in leaves of maize in the field during periods of low temperature. Plant Physiology. 1998;116:571–580. doi: 10.1104/pp.116.2.571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Mauriño S, Monreal JA, Alvarez R, Echevarría C, Vidal J. Characterization of salt stress-enhanced phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase kinase activity in leaves of Sorghum vulgare: independence from osmotic stress, involvement of ion toxicity and significance of dark phosphorylation. Planta. 2003;216:648–655. doi: 10.1007/s00425-002-0893-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genty B, Briantais JM, Baker NR. The relationship between the quantum yield of photosynthetic electron transport and quenching of chlorophyll fluorescence. Biochimica Biophysica Acta. 1989;990:87–92. [Google Scholar]

- Hoagland D, Arnon DI. The water culture method for growing plants without soil. California Agricultural Experiment Station Bulletin No. 1938;347:1–39. [Google Scholar]

- Khan MA, Ungar IA. The role of hormones in regulating the germination of polymorphic seeds and early seedling growth of Atriplex triangularis under saline conditions. Physiologia Plantarum. 1985;63:109–113. [Google Scholar]

- Khan MA, Ungar IA. Germination of the salt tolerant shrub Suaeda fruticosa from Pakistan: salinity and temperature responses. Seed Science Technology. 1998;26:657–667. [Google Scholar]

- Khan MA, Ungar IA. Alleviation of salinity stress and the response to temperature in two seed morphs of Halopyrum mucronatum (Poaceae) Australian Journal of Botany. 2001;49:777–783. [Google Scholar]

- Khan MA, Ungar IA, Showalter AM. The effect of salinity on the growth, water status, and ion content of a leaf succulent perennial halophyte, Suaeda fruticosa (L.) Forssk. Journal of Arid Environments. 2000;45:73–84. [Google Scholar]

- Khan MA, Gul B, Weber DJ. Germination of dimorphic seeds of Suaeda moquinii under high salinity stress. Australian Journal of Botany. 2001;a 49:185–192. [Google Scholar]

- Khan MA, Gul B, Weber DJ. Effect of salinity and temperature on the germination of Kochia scoparia. Wetland Ecology and Management. 2001;b 9:483–489. [Google Scholar]

- Khan MA, Gul B, Weber DJ. Temperature and high salinity effects in germinating dimorphic seeds of Atriplex rosea. Western North American Naturalist. 2004;64:193–201. [Google Scholar]

- Li B, Chollet R. Salt induction and the partial purification/characterization phophoenolpyruvate carboxylase protein-serine kinase from an inducible Crassulacean-acid-metabolism (CAM) plant, Mesembryanthemun crystallinum L. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 1994;314:247–254. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1994.1437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li WQ, Liu X, Khan MA, Yamaguchi S. The effect of plant growth regulators, nitric oxide, nitrate, nitrite and light on the germination of dimorphic seeds of Suaeda salsa under saline conditions. Journal of Plant Research. 2005;118:207–214. doi: 10.1007/s10265-005-0212-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu C, Qiu N, Lu Q, Wang B, Luang T. Does salt stress lead to increased susceptibility of photosystem II to photoinhibition and changes in photosynthetic pigment composition in halophyte Suaeda salsa grown outdoors? Plant Science. 2002;163:1063–1068. [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell K, Johnson GN. Chorophyll fluorescence: a practical guide. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2000;51:659–668. doi: 10.1093/jxb/51.345.659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medrano H, Flexas J. Relaciones hídricas de las plantas. In: Reigosa M, Pedrol N, Sánchez A, editors. La Ecofisiología Vegetal. Una Ciencia de Síntesis. Madrid: Thomson Editores; 2004. pp. 1141–1174. [Google Scholar]

- Mori S, Yoshiba M, Tadano T. Growth response of Suaeda salsa L. Pall to graded NaCl concentrations and the role of chloride in growth stimulation. Soil Science and Plant Nutrition. 2006;52:610–617. [Google Scholar]

- Munns R. Physiological processes limiting plant growth in saline soil: some dogmas and hypotheses. Plant, Cell and Environment. 1983;16:15–24. [Google Scholar]

- Pedrol J, Castroviejo S. In: Suaeda. Castroviejo S, Laínz M, López González G, Montserrat P, Muñoz Garmendia F, Paiva J, editors. Madrid: Real Jardín Botánico, CSIC; 1990. p. 538. Flora Ibérica. Vol. II. Platanaceae–Plumbaginnaceae. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu N, Lu Q, Lu C. Photosynthesis, photosystem II efficiency and the xanthophyll cycle in the salt-adapted halophyte Atriplex centralasiatica. New Phytologist. 2003;159:479–486. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-8137.2003.00825.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawson HM, Long MJ, Munns R. Growth and development in NaCl-treated plants. 1. Leaf Na+ and Cl− concentrations do not determine gas exchange of leaf blades of barley. Australian Journal of Plant Physiology. 1988;15:519–527. [Google Scholar]

- Redondo-Gómez S, Wharmby C, Castillo JM, Mateos-Naranjo E, Luque CJ, de Cires A, et al. Growth and photosynthetic responses to salinity in an extreme halophyte, Sarcocornia fruticosa. Physiologia Plantarum. 2006;128:116–124. [Google Scholar]

- Redondo-Gómez S, Mateos-Naranjo E, Davy AJ, Fernández-Muñoz F, Castellanos EM, Luque T, et al. Growth and photosynthetic responses to salinity of the salt-marsh shrub Atriplex portulacoides. Annals of Botany. 2007;a 100:555–563. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcm119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redondo-Gómez S, Mateos-Naranjo E, Wharmby C, Luque CJ, Castillo JM, Luque T, et al. Bracteoles affect germination and seedling establishment in a Mediterranean population of Atriplex portulacoides. Aquatic Botany. 2007;b 86:93–96. [Google Scholar]

- Sankhla N, Huber W. Regulation of balance between C3 and C4 pathway: role of abscisic acid. Zeitschrift fur Pflanzenphysiologie. 1974;74:267–271. [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber U, Schliwa W, Bilger U. Continuous recording of photochemical and non-photochemical chlorophyll fluorescence quenching with a new type of modulation fluorimeter. Photosynthesis Research. 1986;10:51–62. doi: 10.1007/BF00024185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shomer-Ilan A, Nissenbaum A, Waisel Y. Photosynthetic pathways and the ecological distribution of the Chenopodiaceae in Israel. Oecologia. 1981;48:244–248. doi: 10.1007/BF00347970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song J, Feng G, Tian C, Zhang F. Strategies for adaptation of Suaeda physophora Haloxylon ammodendron and Haloxylon persicum to a saline environment during seed-germination stage. Annals of Botany. 2005;96:399–405. doi: 10.1093/aob/mci196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ungar IA. Ecophysiology of vascular halophytes. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Véry AA, Robinson MF, Mansfield TA, Sanders D. Guard cell cation channels are involved in Na+-induced stomatal closure in a halophyte. The Plant Journal. 1998;14:509–521. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss PW. Germination, reproduction and interference in the amphicarpic annual Emex spinosa. Oecologia. 1980;45:244–251. doi: 10.1007/BF00346465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams MD, Ungar IA. The effect of environmental parameters on the germination, growth, and development of Suaeda depressa (Pursh) Wats. American Journal of Botany. 1972;59:912–918. [Google Scholar]

- Yokoishi T, Tanimoto S. Seed germination of the halophyte Suaeda japonica under salt stress. Journal of Plant Research. 1994;107:385–388. [Google Scholar]