Abstract

Research throughout the last century has led to a consensus as to the strategy of the humoral component of the immune system. The essence is that, for killing, the antibody molecule activates additional systems that respond to antibody–antigen union. We now report that the immune system seems to have a previously unrecognized chemical potential intrinsic to the antibody molecule itself. All antibodies studied, regardless of source or antigenic specificity, can convert molecular oxygen into hydrogen peroxide, thereby potentially aligning recognition and killing within the same molecule. Aside from pointing to a new chemical arm for the immune system, these results may be important to the understanding of how antibodies evolved and what role they may play in human diseases.

The antibody is a remarkable adaptor molecule, having evolved both targeting and effector functions that place it at the frontline of vertebrate defense against foreign invaders (1). In terms of the effector mechanism, the central idea is that antibodies themselves do not possess destructive ability but mark foreign substances for removal by the complement cascade and/or phagocytosis (2, 3).

The advent of antibody catalysis has demonstrated that antibodies are capable of much more complex chemistry than simple binding (4). This has inevitably lead to the question as to whether more sophisticated chemical mechanisms are part of the strategy of the antibody molecule itself. Thus far, there has been no evidence to support this idea, and we are left with the notion that just because antibodies are capable of complex chemistry, it does not mean that they use it in host defense. However, we now report a hitherto unremarked capacity of antibodies to convert molecular oxygen into hydrogen peroxide, thereby effectively linking recognition and killing events.

Materials and Methods

The following whole antibodies were obtained from PharMingen: 49.2 (mouse IgG2b κ), G155-178 (mouse IgG2a κ), 107.3 (mouse IgG1 κ), A95-1 (rat IgG2b), G235-2356 (hamster IgG), R3-34 (rat IgG κ), R35-95 (rat IgG2a κ), 27-74 (mouse IgE), A110-1 (rat IgG1 λ), 145-2C11 (hamster IgG group1 κ), M18-254 (mouse IgA κ), and MOPC-315 (mouse IgA λ). The following were obtained from Pierce: 31243 (sheep IgG), 31154 (human IgG), 31127 (horse IgG), and 31146 (human IgM).

The following F(ab′)2 fragments were obtained from Pierce: 31129 (rabbit IgG), 31189 (rabbit IgG), 31214 (goat IgG), 31165 (goat IgG), and 31203 (mouse IgG). Protein A, protein G, trypsin–chymotrypsin inhibitor (Bowman–Birk inhibitor), β-lactoglobulin A, α-lactalbumin, myoglobin, β-galactosidase, chicken egg albumin, aprotinin, trypsinogen, lectin (peanut), lectin (Jacalin), BSA, superoxide dismutase, and catalase were obtained from Sigma. Ribonuclease I A was obtained from Amersham Pharmacia. The following immunoglobulins were obtained in-house using hybridoma technology: OB2-34C12 (mouse IgG1 κ), SHO1-41G9 (mouse IgG1 κ), OB3-14F1 (mouse IgG2a κ), DMP-15G12 (mouse IgG2a κ), AD1-19G1 (mouse IgG2b κ), NTJ-92C12 (mouse IgG1 κ), NBA-5G9 (mouse IgG1 κ), SPF-12H8 (mouse IgG2a κ), TIN-6C11 (mouse IgG2a κ), PRX-1B7 (mouse IgG2a κ), HA5-19A11 (mouse IgG2a κ), EP2-19G2 (mouse IgG1 κ), GNC-92H2 (mouse IgG1 κ), WD1-6G6 (mouse IgG1 κ), CH2-5H7 (mouse IgG2b κ), PCP-21H3 (mouse IgG1 κ), and TM1-87D7 (mouse IgG1 κ). DRB polyclonal (human IgG) and DRB-b12 (human IgG) were supplied by Dennis R. Burton (The Scripps Research Institute). 1D4 Fab (crystallized) was supplied by Ian A. Wilson (The Scripps Research Institute).

All assays were carried out in PBS (10 mM phosphate/160 mM sodium chloride, pH 7.4). Commercial protein solution samples were dialyzed into PBS as necessary. Amplex Red hydrogen peroxide assay kits (A-12212) were obtained from Molecular Probes.

Antibody/Protein Irradiation.

Unless otherwise stated, the assay solution (100 μl, 6.7 μM protein in PBS, pH 7.4) was added to a glass vial, sealed with a screw-cap, and irradiated with either UV (312 nm, 8000 μWcm−2 Fischer–Biotech transilluminator) or visible light.

Quantitative Assay for Hydrogen Peroxide.

An aliquot (20 μl) from the protein solution was removed and added into a well of a 96-well microtiter plate (Costar) containing reaction buffer (80 μl). Working solution (100 μl/400 μM Amplex Red reagent 1/2 units/ml horseradish peroxidase) was then added, and the plate was incubated in the dark for 30 min. The fluorescence of the well components was then measured using a CytoFluor Multiwell Plate Reader (Series 4000, PerSeptive Biosystems, Framingham, MA; Ex/Em: 530/580 nm). The hydrogen peroxide concentration was determined using a standard curve. All experiments were run in duplicate, and the rate is quoted as the mean of at least two measurements.

Sensitization and Quenching Assays.

A solution of 31127 (100 μl of horse IgG, 6.7 μM) in PBS (pH 7.4, 4% dimethylformamide) and hematoporphyrin IX (40 μM) was placed in proximity to a strip light. Hydrogen peroxide concentration was determined as described vide supra. The assay was also performed in the presence of NaN3 (100 mM) or PBS in D2O.

Oxygen Dependence.

A solution of 31127 (1.6 ml, horse IgG, 6.7 μM) in PBS (pH 7.4) was rigorously degassed using the freeze/thaw method under argon. Aliquots (100 μl) were introduced into septum-sealed glass vials that had been purged with the appropriate O2/Ar mixtures (0–100%) via syringe. Dissolved oxygen concentrations were measured with an Orion 862A dissolved oxygen meter. These solutions were then vortexed vigorously, allowed to stand for 20 min, and then vortexed again. A syringe containing the requisite O2/Ar mixture was used to maintain atmospheric pressure during the course of the experiment. Aliquots (20 μl) were removed using a gas-tight syringe and hydrogen peroxide concentration measured as described vide supra. The data from three separate experiments were collated and analyzed using the Enzyme Kinetics v1.1 computer program (for determination of Vmax and Km parameters).

Antibody Production of Hydrogen Peroxide in the Dark, Using a Chemical 1O2 Source.

A solution of sheep IgG 31243 (100 μl, 20 μM) in PBS (pH 7.4) and the endoperoxide of disodium 3,3′-(1,4-naphthylidene) dipropionate (25 mM in D2O) was placed in a warm room (37°C) for 30 min in the dark. Hydrogen peroxide concentration was determined as described vide supra.

Hydrogen Peroxide Formation by the Fab-1D4 Crystal.

A suspension of crystals of the Fab fragment of 1D4 (2 μl) was diluted with PBS (198 μl, pH 7.4) and vortexed gently. Following centrifugation, the supernatant was removed, and the washing procedure was repeated twice further. The residual crystal suspension was then diluted into PBS, pH 7.4 (100 μl), and added into a well of a quartz ELISA plate. Following UV irradiation for 30 min, Amplex Red working solution (100 μl) was added, and the mixture was viewed on a fluorescence microscope.

Antibody Fluorescence Versus Hydrogen Peroxide Formation.

A solution of 31127 (1.0 ml of horse IgG, 6.7 μM) in PBS (pH 7.4) was placed in a quartz cuvette and irradiated with UV light for 40 min. At 10-min intervals, the fluorescence of the solution was measured using an SPF-500C spectrofluorimeter (SLM–Aminco, Urbana, IL; Ex/Em, 280/320). At the same time point, an aliquot (20 μl) of the solution was removed, and the hydrogen peroxide concentration was determined as described vide supra.

Consumption of Hydrogen Peroxide by Catalase.

A solution of EP2-19G12 (100 μl of mouse IgG, 20 μM in PBS, pH 7.4) was irradiated with UV light for 30 min, after which time the concentration of hydrogen peroxide was determined by stick test (EM Quant Peroxide Test Sticks) to be 2 mg/liter. Catalase [1 μl, Sigma, 3.2 M (NH4)2SO4, pH 6.0] was added, and after 1 min, the concentration of H2O2 was found to be 0 mg/liter.

Denaturation.

IgG 19G12 (100 μl, 6.7 μM) was heated to 100°C in an Eppendorf tube for 2 min. The resultant solution was transferred to a glass, screw-cap vial and irradiated with UV light for 30 min. The concentration of H2O2 was determined after 30 min.

Results and Discussion

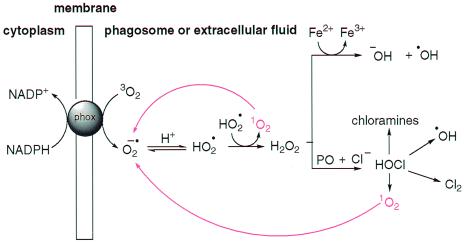

The preliminary step in the phagocytic oxidative burst is the single electron reduction of ground-state molecular oxygen (3O2) by the NADPH-dependent transmembrane phagocyte oxidase enzyme system that generates superoxide anion (O2•−) (Fig. 1) (5, 6).

Figure 1.

Oxygen-dependent microbicidal action of phagocytes. Red lines indicate the interconversion of 1O2 and O2·−, an ability intrinsic to antibodies. PO, peroxidase enzymes; phox, phagocyte oxidase.

Superoxide anion occupies a critical position in the cycling of oxygen-dependent microbicidal agents in vivo because although it is not itself considered to be cytotoxic (7), it is a direct precursor of hydrogen peroxide and the toxic derivatives it spawns, such as hydroxyl radical (HO⋅) and hypohalous acid (HOCl). In addition, when iron concentrations are limiting, O2•− is a vital reducing agent that regenerates Fe2+, thus facilitating the iron-catalyzed Haber–Weiss reaction, or the so-called superoxide-driven Fenton reaction that produces HO⋅ (Eqs. 1 and 2). Therefore, processes that facilitate the generation of O2•− will ultimately perpetuate and potentiate oxygen-dependent microbicidal action.

|

1 |

|

2 |

Another key component of the oxygen-scavenging cascade is singlet molecular oxygen (1O2). This particularly reactive species is an excited state of molecular oxygen in which both outer shell electrons are spin-paired (8). It is important in pathological biological systems and has a very short life-time (ca. 4 μs) in vivo (9). Generation of 1O2 during microbicidal processes is either direct, via the action of flavoprotein oxidases (10, 11), or indirect, via the nonenzymatic disproportionation of O2•− in solutions at low pH, as found in the phagosome (Eq. 3) (12, 13).

|

3 |

The high reactivity of 1O2 with biomolecules has meant that it is generally considered to be an endpoint in the cascade of oxygen-scavenging agents. However, we have found that antibodies, as a class of proteins, have the intrinsic ability to intercept 1O2 and efficiently reduce it to O2•−, thus offering a mechanism by which oxygen can be rescued and recycled during phagocyte action, thereby potentiating the microbicidal action of the immune system.

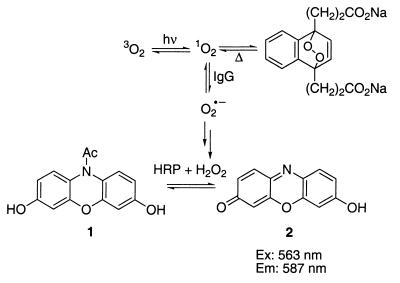

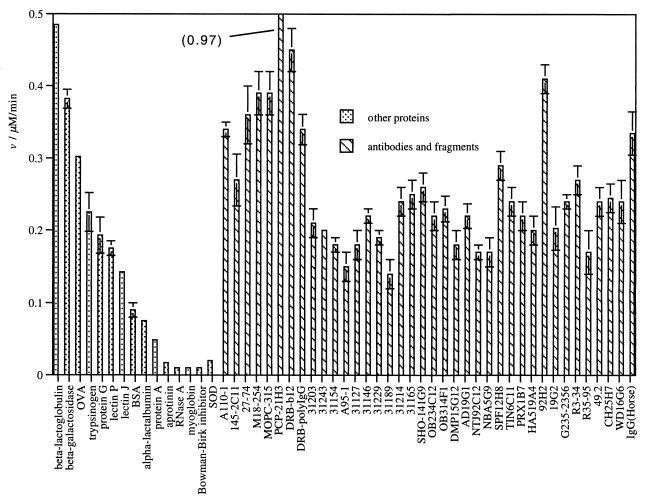

The measured values for the initial rate of formation of hydrogen peroxide by a panel of intact immunoglobulins and antibody fragments are collected in Table 1. We believe that Ig-generated O2•− dismutates spontaneously into H2O2, which is then utilized as a cosubstrate with N-acetyl-3,7-dihydroxyphenazine 1 (Amplex Red) for horseradish peroxidase, which produces the highly fluorescent resorufin 2 (excitation maxima 563 nm, emission maxima 587 nm) (Fig. 2) (14). To confirm that irradiation of the buffer does not generate O2•− and that the antibodies are not simply acting as protein dismutases (15), the enzyme superoxide dismutase was irradiated in PBS. Under these conditions, the rate of hydrogen peroxide generation is the same as irradiation of PBS alone.

Table 1.

Production of hydrogen peroxide* by immunoglobulins

| Entry | Clone | Source | Isotype | Rate,† nmol/min/mg |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | CH25H7 | Mouse | IgG2b, κ | 0.25 |

| 2 | WD16G6 | Mouse | IgG1, κ | 0.24 |

| 3 | SHO-141G9 | Mouse | IgG1, κ | 0.26 |

| 4 | OB234C12 | Mouse | IgG1, κ | 0.22 |

| 5 | OB314F1 | Mouse | IgG2a, κ | 0.23 |

| 6 | DMP15G12 | Mouse | IgG2a, κ | 0.18 |

| 7 | AD19G1 | Mouse | IgG2b, κ | 0.22 |

| 8 | NTJ92C12 | Mouse | IgG1, κ | 0.17 |

| 9 | NBA5G9 | Mouse | IgG1, κ | 0.17 |

| 10 | SPF12H8 | Mouse | IgG2a, κ | 0.29 |

| 11 | TIN6C11 | Mouse | IgG2a, κ | 0.24 |

| 12 | PRX1B7 | Mouse | IgG2a, κ | 0.22 |

| 13 | HA519A4 | Mouse | IgG1, κ | 0.20 |

| 14 | 92H2 | Mouse | IgG1, κ | 0.41 |

| 15 | 19G2 | Mouse | IgG1, κ | 0.20 |

| 16 | PCP-21H3 | Mouse | IgG1, κ | 0.97 |

| 17 | TM1-87D7 | Mouse | IgG1, κ | 0.28 |

| 18 | 49.2 | Mouse | IgG2b, κ | 0.24 |

| 19 | 27-74 | Mouse | IgE, std. isotype | 0.36 |

| 20 | M18-254 | Mouse | IgA, κ | 0.39 |

| 21 | MOPC-315 | Mouse | IgA, λ | 0.39 |

| 22 | 31203 | Mouse | F(ab′)2 | 0.21 |

| 23 | b12 | Human | IgG | 0.45 |

| 24 | polyclonal | Human | IgG | 0.34 |

| 25 | 31154 | Human | IgG | 0.18 |

| 26 | 31146 | Human | IgM | 0.22 |

| 27 | R3-34 | Rat | IgG1, κ | 0.27 |

| 28 | R35-95 | Rat | IgG2a, κ | 0.17 |

| 29 | A95-1 | Rat | IgG2b | 0.15 |

| 30 | A110-1 | Rat | IgG1, λ | 0.34 |

| 31 | G235-2356 | Hamster | IgG | 0.24 |

| 32 | 145-2C11 | Hamster | IgG, gp 1, κ | 0.27 |

| 33 | 31243 | Sheep | IgG | 0.20 |

| 34 | 31127 | Horse | IgG | 0.18 |

| 35 | polyclonal | Horse | IgG | 0.34 |

| 36 | 31229 | Rabbit | F(ab′)2 | 0.19 |

| 37 | 31189 | Rabbit | F(ab′)2 | 0.14 |

| 38 | 31214 | Goat | F(ab′)2 | 0.24 |

| 39 | 31165 | Goat | F(ab′)2 | 0.25 |

Assay conditions are described in Materials and Methods.

Mean values of at least two determinations. The background rate of H2O2 formation is 0.005 nmol/min in PBS and 0.003 nm/min in PBS with SOD.

Figure 2.

Amplex Red H2O2 assay. HRP, horseradish peroxidase.

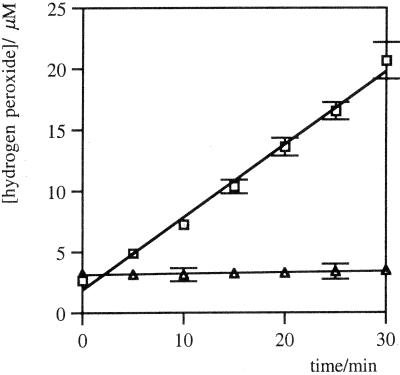

The rates of hydrogen peroxide formation were linear for more than 10% of the reaction, with respect to the oxygen concentration in PBS under ambient conditions (275 μM). With sufficient oxygen availability, the antibodies can generate at least 40 equivalents of H2O2 per protein molecule without either a significant reduction in activity or structural fragmentation. An example of the initial time course of hydrogen peroxide formation in the presence or absence of antibody 19G2 is shown in Fig. 3A. This activity is lost following denaturation of the protein by heating.

Figure 3.

Initial time course of H2O2 production in PBS, pH 7.4, in the presence (□) or absence (▵) of murine monoclonal IgG EP2-19G2 (20 μM). Error bars show the range of the data from the mean.

The data in Table 1 reveal a universal ability of antibodies to generate H2O2 from 1O2. This function seems to be shared across a range of species and is independent of the heavy and light chain compositions investigated or antigen specificity. The initial rates of hydrogen peroxide formation for the intact antibodies is highly conserved, varying from 0.15 nmol/min/mg [clone A95-1(rat IgG2b)] to 0.97 nmol/min/mg (clone PCP-21H3, a murine monoclonal IgG) across the whole panel. Although the information available is more limited for the component antibody fragments, the activity seems to reside in both the Fab and F(ab′)2 fragments.

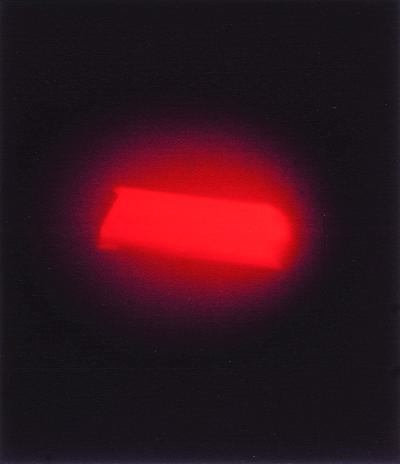

If this activity were due to a contaminant, it would have to be present in every antibody and antibody fragment obtained from diverse sources. However, to further rule out contamination, crystals of the murine antibody 1D4 Fab from which high-resolution x-ray structures have been obtained (at 1.7 Å) were investigated for their ability to generate H2O2 (Fig. 4). Reduction of 1O2 is clearly observed in these crystals.

Figure 4.

Fluorescent micrograph of a single crystal of murine antibody 1D4 Fab fragment after UV irradiation and H2O2 detection with the Amplex Red reagent.

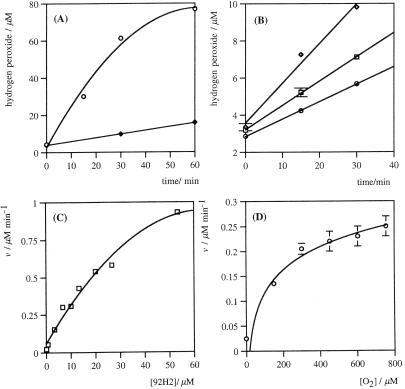

Investigations into this antibody transformation support singlet oxygen as the intermediate being reduced. No formation of hydrogen peroxide occurs with antibodies under anaerobic conditions either in the presence or absence of UV irradiation. Furthermore, no generation of hydrogen peroxide occurs under ambient aerobic conditions without irradiation. Irradiation of antibodies with visible light in the presence of a known photosensitizer of 3O2 in aqueous solutions (16), hematoporphyrin (HP), leads to hydrogen peroxide formation (Fig. 5A). The curving in the observed rates is due to consumption of oxygen from within the assay mixture. Concerns that the interaction between photoexcited HP and oxygen may be resulting in O2•− formation (17, 18) were largely discounted by suitable background experiments with the sensitizer alone (data shown in Fig. 5A). The efficient formation of H2O2 with HP and visible light both reaffirm the intermediacy of 1O2 and show that UV radiation is not necessary for the Ig to perform this reduction.

Figure 5.

(A) HP sensitization assay. Time course of H2O2 formation in PBS (pH 7.4) with HP (40 μM) and visible light, in the presence (○) or absence (♦) of 31127 (horse IgG, 20 μM). (B) Initial time course of H2O2 production with HP (40 μM) and visible light, in the presence of 31127 (horse IgG, 6.7 μM) with no additive in PBS (pH 7.4) (□) or NaN3 in PBS (pH 7.4) (○, 100 mM) or in a D2O solution of PBS (pH 7.4) (⋄). (C) Protein concentration (31127, horse IgG) versus rate of H2O2 formation. (D) Oxygen concentration on the rate of H2O2 generation with 31127 (horse IgG, 6.7 μM). All points are mean values of at least duplicate experimental determinations. Error bars are the range of experimentally measured values from the mean.

Furthermore, incubation of sheep antibody 31243 in the dark at 37°C, with a chemical source of 1O2 [the endoperoxide of 3′,3′-(1,4-naphthylidene) dipropionate] leads to hydrogen peroxide formation.

The rate of formation of H2O2, by horse IgG with HP (40 μM) in visible light, is increased in the presence of D2O and reduced with the 1O2 quencher NaN3 (40 mM) (Fig. 5B) (19). The substitution of D2O for H2O is known to promote 1O2-mediated processes via an increase of approximately 10-fold in its lifetime (20).

The rate of hydrogen peroxide formation is proportional to IgG concentration between 0.5 and 20 μM but starts to curve at higher concentrations (Fig. 5C). The lifetime of 1O2 in protein solution is expected to be lower than in pure water due to the opportunity for reaction. We reason, therefore, that the observed curvature may be due to a reduction in the lifetime of 1O2 due to reaction with the antibody.

Significantly, the effect of oxygen concentration on the observed rate of H2O2 production shows a significant saturation above 200 μM of oxygen (Fig. 5D). Therefore, the mechanism of reduction may involve either one or more oxygen binding sites within the antibody molecule. By treating the raw rate data to nonlinear regression analysis and by fitting to the Michaelis–Menten equation, a Kmapp(O2) of 187 μM and a Vmaxapp of 0.4 nmol/min/mg are obtained. This antibody rate is equivalent to that observed for mitochondrial enzymes that reduce molecular oxygen in vivo.

The mechanism by which antibodies reduce 1O2 is still being determined. However, the participation of a metal-mediated redox process has been largely discounted because the activity of the antibodies remains unchanged after exhaustive dialysis in PBS containing EDTA (4 mM). This leaves the intrinsic ability of the amino acid composition of the antibodies themselves. Aromatic amino acids such as tryptophan (Trp) can be oxidized by 1O2 via electron transfer (21). In addition, disulfides are sufficiently electron rich that they can also be oxidized (22). Therefore, there is the potential that Trp residues and/or the intrachain or interchain disulfide bonds homologous to all antibodies are responsible for 1O2 reduction. To both investigate to what extent this ability of antibodies is shared by other proteins and to probe the mechanism of reduction, a panel of other proteins was studied (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Bar graph showing the measured initial rate of H2O2 formation for a panel of proteins and comparison with antibodies (data from Table 1). All points are mean values of at least duplicate experimental determinations. Error bars are the range of experimentally measured values from the mean. OVA, chick-egg ovalbumin; SOD, superoxide dismutase.

Whereas other proteins can convert 1O2 into O2•−, in contrast to antibodies it is by no means a universal property. RNase A and superoxide dismutase, which do not possess Trp residues but have several disulfide bonds, do not reduce 1O2. Similarly, the Bowman–Birk inhibitor protein (23, 24) that has seven disulfide bonds and zero Trp residues does not reduce 1O2. In contrast, chick ovalbumin, which has only 2 Trp residues (25), is one of the most efficient proteins at reducing 1O2.

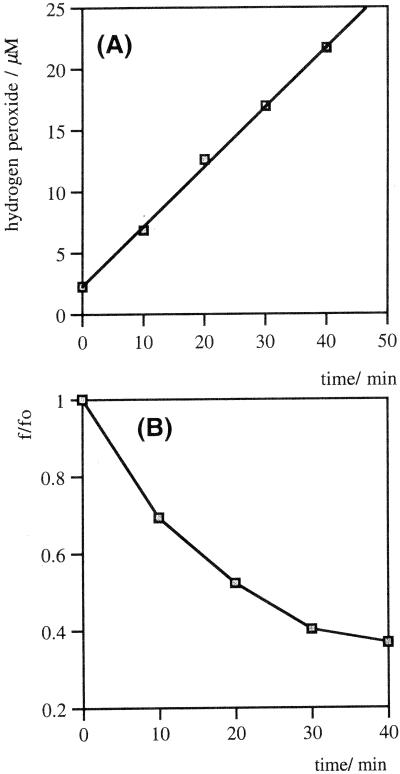

Given the loss of antibody activity upon denaturation, the location of key residues in the protein is likely to be more critical than their absolute number. Because the majority of aromatic residues in proteins are generally buried to facilitate structural stability (26), the nature of the reduction process was explored in terms of relative contribution of surface and buried residues by fluorescence-quenching experiments. Aromatic amino acids in proteins are modified by the absorption of Ultraviolet light, especially in the presence of sensitizing agents such as molecular oxygen or ozone (27–29). Trp reacts with 1O2 via a [2 + 2] cycloaddition to generate N-formylkynurenine or kynurenine, which are both known to significantly quench the emission of buried Trp residues (30). The intrinsic fluorescence of horse IgG is rapidly quenched to 30% of its original value during a 40-min irradiation, whereas hydrogen peroxide generation is linear throughout (r2 = 0.998) (Fig. 7). If the reduction of singlet oxygen is due to antibody Trp residues, then the solvent-exposed Trp seem to contribute to a lesser degree than the buried ones. This factor may help to explain why this ability is so highly conserved among antibodies. In greater than 99% of known antibodies there are two conserved Trp residues, and they are both deeply buried: Trp-36 and Trp-47 (31).

Figure 7.

(A) Rate of H2O2 formation by UV irradiation of horse IgG (6.7 μM) in PBS (pH 7.4). (B) Simultaneous fluorescence emission of the horse IgG, measured at 326 nm (excitation = 280 nm).

Conclusions

Throughout nature, organisms have defended themselves by production of relatively simple chemicals. At the level of single molecules, this mechanism has thought to be largely abandoned with the appearance in vertebrates of the immune system. It was considered that once a targeting device had evolved, the killing mechanism moved elsewhere. Our studies realign recognition with killing within the same molecule. In a certain sense this chemical immune system parallels the purely chemical defense mechanism of lower organisms, with the exception that a more sophisticated and diverse targeting element is added.

Given the constraints that an ideal killing system must use host molecules in a localized fashion while minimizing self damage, one can hardly imagine a more judicious choice than 1O2. Because one already has such a reactive molecule, it is important to ask what might be the advantage of its further conversion by the antibody. The key issue is that by conversion of the transient singlet oxygen molecule (lifetime 4 μs) into the more stable O2•−, one now has access to hydrogen peroxide and all of the toxic products it can generate. In addition, superoxide is the only molecular oxygen equivalent remaining at the end of the oxygen-scavenging cascade. Therefore, this “recycling” may serve as a crucial mechanism for potentiation of the microbicidal process. Another benefit of singlet molecular oxygen is that it is only present when the host is under assault, thereby making it an “event-triggered” substrate. Also, because there are alternative ways to defend that use accessory systems, this chemical arm of the immune system might be silent under many circumstances. This said, however, there may be many disease states where antibody and singlet oxygen find themselves juxtaposed, thereby leading to cellular and tissue damage. Given that diverse events in man lead to the production of singlet oxygen, its activation by antibodies may lead to a variety of diseases ranging from autoimmunity to repurfusion injury and atherosclerosis (32).

Finally, these findings raise questions as to how the immune system may have evolved. It is possible that it began as a single protein with killing capacity and that the diversity and recognition components evolved later. Thus, the ability of certain other proteins to perform this process, although usually at a lower rate, offers the prospect that antibodies evolved by coupling this specific property of some proteins with a diversity-generated targeting device. From an evolutionary perspective, the key issue is that this ability seems to be conserved in all antibodies.

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. D. R. Burton for the donation of the human monoclonal IgG, b12, and polyclonal IgG sample and Prof. I. A. Wilson for the donation of Fab 1D4 crystals. We also thank Prof. N. B. Gilula and Ingrid Niesman for assistance in generating the fluorescence micrograph in Fig. 4. This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grant GM 43858 (to K.D.J.), National Cancer Institute Program Project 2PO1CA27489 (to K.D.J. and R.A.L.), and The Skaggs Institute for Chemical Biology.

Abbreviation

- HP

hematoporphyrin

References

- 1.Burton D R. Trends Biochem Sci. 1990;15:64–69. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(90)90178-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arlaud G J, Colomb M G, Gagnon J. Immunol Today. 1987;8:106–111. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(87)90860-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sim R B, Reid K B. Immunol Today. 1991;12:307–311. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(91)90004-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wentworth P, Jr, Janda K D. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 1998;2:138–144. doi: 10.1016/s1367-5931(98)80046-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klebanoff S J. In: Encyclopedia of Immunology. Delves P J, Roitt I M, editors. San Diego: Academic; 1998. pp. 1713–1718. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rosen H, Klebanoff S J. J Biol Chem. 1977;252:4803–4810. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fee J A. In: International Conference on Oxygen and Oxygen-Radicals. Rodgers M A J, Powers E L, editors. San Diego, and University of Texas at Austin: Academic; 1981. pp. 205–239. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kearns D R. Chem Rev. 1971;71:395–427. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Foote C S. In: Free Radicals in Biology. Pryor W A, editor. New York: Academic; 1976. pp. 85–133. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Allen, R. C., Stjernholm, R. L., Benerito, R. R. & Steele, R. H. (1973) eds. Cormier, M. J., Hercules, D. M. & Lee, J. (Plenum, New York), pp. 498–499.

- 11.Klebanoff S J. The Phagocytic Cell in Host Resistance. Orlando, FL: National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stauff J, Sander U, Jaeschke W. In: Chemiluminescence and Bioluminescence. Williams R C, Fudenberg H H, editors. New York: Intercontinental Medical Book Corp.; 1973. pp. 131–141. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Allen R C, Yevich S J, Orth R W, Steele R H. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1974;60:909–917. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(74)90401-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhou M, Diwu Z, Panchuk-Voloshina N, Haugland R P. Anal Biochem. 1997;253:162–168. doi: 10.1006/abio.1997.2391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Petyaev I M, Hunt J V. Redox Report. 1996;2:365–372. doi: 10.1080/13510002.1996.11747076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kreitner M, Alth G, Koren H, Loew S, Ebermann R. Anal Biochem. 1993;213:63–67. doi: 10.1006/abio.1993.1386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beauchamp C, Fridovich I. Anal Biochem. 1971;44:276–287. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(71)90370-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Srinivasan V S, Podolski D, Westrick N J, Neckers D C. J Am Chem Soc. 1978;100:6513–6515. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hasty N, Merkel P B, Radlick P, Kearns D R. Tetrahedron Lett. 1972. 49–52. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Merkel P B, Nillson R, Kearns D R. J Am Chem Soc. 1972;94:1030–1031. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grossweiner L I. Curr Top Radiat Res Q. 1976;11:141–199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bent D V, Hayon E. J Am Chem Soc. 1975;87:2612–2619. doi: 10.1021/ja00843a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Voss R-H, Ermler U, Essen L-O, Wenzl G, Kim Y-M, Flecker P. Eur J Biochem. 1996;242:122–131. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.0122r.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baek J, Kim S. Plant Physiol. 1993;102:687. doi: 10.1104/pp.102.2.687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Feldhoff R, Peters T J. Biochem J. 1976;159:529–533. doi: 10.1042/bj1590529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Burley S K, Petsko G A. Science. 1985;229:23–28. doi: 10.1126/science.3892686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Foote C S. Science. 1968;162:963–970. doi: 10.1126/science.162.3857.963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Foote C S. Free Radicals Biol. 1976;2:85–133. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gollnick K. Adv Photochem. 1968;6:1–122. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mach H, Burke C J, Sanyal G, Tsai P-K, Volkin D B, Middaugh C R. In: Formulation and Delivery of Proteins and Peptides. Cleland J L, Langer R, editors. Denver, CO: American Chemical Society; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kabat E A, Wu T T, Perry H M, Gottesman K S, Foeller C. Sequences of Proteins of Immunological Interest. Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Skepper J, Pierson R, Young V, Rees J, Powell J, Navaratnam V, Cary N, Tew D, Bacon P, Wallwork J, et al. Microsc Res Tech. 1998;42:369–385. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0029(19980901)42:5<369::AID-JEMT7>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]