Abstract

The liver plays a central role in lipid and glucose metabolism. Two studies in this issue (Kubota et al., 2008; Dong et al., 2008) on the insulin-signaling adaptors Irs1 and Irs2 prompt a critical reappraisal of the physiology of fasting and of the integrated control of hepatic insulin action.

Unlike other receptor tyrosine kinases, insulin receptors grace the surface of target cells as preassembled heterodimers and use adaptor proteins to activate PI3K. The molecular cloning of these adaptors, named insulin receptor substrates (Irs), provided a cogent mechanistic and evolutionary explanation for the divergence of insulin signaling from oncogene and growth-factor signaling. Irs proteins carry out various functions downstream of insulin (and IGF) receptors by (1) providing a juxtamembrane localization signal for PIP3 generation, (2) amplifying the signal engendered by receptor autophosphorylation, and (3) engaging a panoply of substrates that account for the diverse actions of insulin (White, 2003).

Phenotypic differences between different Irs knockout mice ushered in the idea that Irs play distinct roles in different tissues, downstream of insulin versus IGF receptors. Irs1 knockouts are runted and mildly insulin resistant, consistent with a preferential role downstream of IGF-1 receptors; Irs2 knockouts develop peripheral insulin resistance and β cell failure, while knockouts of Irs3 or Irs4 display mild metabolic and growth phenotypes (Nandi et al., 2004). Although some phenotypic variation can be explained by differences in tissue distribution (tissues with insulin-dependent glucose uptake, for example, express Irs1 and Irs3, with little Irs2), the broader question of whether there is functional overlap or specificity in Irs1 versus Irs2 signaling was largely unsettled.

The Liver Conundrum

Nowhere was this issue more prominent than in studies of liver insulin action. Abnormalities of hepatic insulin action—of the cell-autonomous and nonautonomous varieties—play an important role in the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, and dyslipidemia.

In type 2 diabetes, hepatic insulin resistance is associated with increased glucose production (HGP) and ApoB-containing lipoprotein secretion. The former is arguably the cause of deteriorating glucose control experienced by most diabetic patients over time, regardless of therapy (Monnier et al., 2003). The latter underpins the predisposition to atherosclerosis, which ultimately will be responsible for nearly one in two deaths among diabetics (National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, 2005).

But the two abnormalities can hardly be subsumed under the common rubric of insulin resistance. For while it's increasingly clear—and strongly supported by the papers by Kubota et al. and Dong et al. in this issue (Kubota et al., 2008; Dong et al., 2008)—that an impairment of insulin receptor signaling to Foxo1 can explain insulin's inability to restrain HGP, one would predict that, if the liver were wholly insulin resistant, triglyceride (TG) synthesis and assembly into ApoB-containing lipoproteins would also be impaired. But the opposite is true in the diabetic liver.

In recent years, the idea that the diabetic liver may harbor a noxious brew of insulin resistance and excessive insulin sensitivity has gained a second wind. The concept is neither new nor limited to the liver. Several manifestations of insulin resistance—e.g., polycystic ovarian disease and acanthosis nigricans—reflect excessive rather than reduced insulin signaling. But whereas in those tissues insulin can act through IGF-1 receptors—if blood insulin levels are high enough—hepatocytes lack IGF-1 receptors, and thus the explanation for the metabolic admixture of sensitivity and resistance to insulin in liver must reside within the different branches of insulin receptor signaling.

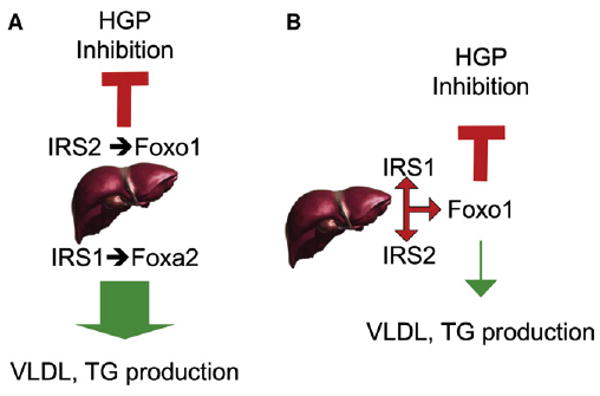

In this context, several laboratories— including ours—had proposed that different Irs proteins mediate different branches of insulin signaling. The prevailing model was that Irs1 presided over lipid metabolism, whereas Irs2 presided over HGP (Figure 1A).

Figure 1. The Changing Face of Hepatic Insulin Resistance.

(A) The prevailing model had been that liver insulin signaling occurred by way of branched pathways. One pathway, associated with Irs2 and Foxo1, was thought to preside over the inhibition of glucose production (indicated by a red “tee” symbol). The other pathway, mediated by Irs1 and Foxa2, was thought to mediate lipid synthesis and lipoprotein assembly/secretion (indicated by a thick green arrow).

(B) The work of Kubota et al. and Dong et al. supports a model in which Irs1 and Irs2 act in different conditions (fasting or feeding), but in essentially linear pathways, both effected through Foxo1. The decrease in TG levels and secretion in double Irs knockouts (denoted by the thin green line, as opposed to the thick green line in A) is consistent with a role of excessive insulin signaling, rather than insulin resistance, in the pathogenesis of the lipid abnormalities of type 2 diabetes.

The two papers in this issue (Kubota et al., 2008; Dong et al., 2008) provide a different explanation. Using conditional knockouts of liver Irs1 and Irs2, the authors demonstrate that the two proteins play overlapping roles in insulin action, with Irs1 acting in the postprandial state, and Irs2 in the fasted state. The two substrates are able to compensate for one another, indicating that specificity of insulin signaling arises downstream of Irs proteins. Their actions are funneled through transcription factor Foxo1, further establishing the latter's role as linchpin of insulin action.

Whither Hepatic Insulin Resistance?

Several observations in these papers will likely reshape our thinking on metabolic disorders. The branched pathway model of insulin signaling, in which Irs1 signals to lipid metabolism and Irs2 to glucose metabolism, is no longer tenable and should be abandoned (Figure 1b). The two proteins are effectively interchangeable in relaying specific actions of insulin, as demonstrated by the fact that individual knockouts of Irs1 or Irs2 have little or no metabolic effect, while the combined knockouts result in severe diabetes.

The Kubota paper shows that physiologically the two substrates take turns in mediating insulin action, with Irs1 acting as the housekeeping pathway and Irs2 picking up the slack during fasting and early refeeding. But what is the need for a dedicated insulin-signaling pathway during fast, a time that should reflect relative insensitivity to insulin? The most obvious explanation is to preserve insulin sensitivity in the face of changes in counterregulatory hormones during the sleep-wake cycle, nocturnal flux of FFAs from adipose tissue, pulsatile insulin secretion, or metabolic cues emanating from circadian pacemakers. Bergman and others, for example, documented the role of nocturnal flux of FFA to the liver in promoting insulin resistance, arguably by impairing insulin suppression of HGP (Bergman and Ader, 2000). But in light of the Kadowaki paper showing that insulin sensitivity is maintained by Irs2 during fast, FFAs could also provide grist for the lipogenic mill, driving VLDL and LDL secretion, and thus setting off the ill-starred combination of excessive glucose and lipid production. Another clinical syndrome that should be re-examined in light of these new findings is impaired fasting glucose (IFG), a widespread condition of unclear pathophysiology (Kim and Reaven, 2008). The reader should note that in Dong et al. (but not in Kubota et al.), fasting glucose levels inch up in Irs2 knockouts. Should we resequence the IRS2 gene in humans with IFG?

The Dog That Didn't Bark

Dong et al.'s paper shows that lipid metabolism is essentially normal (or improved) in mice lacking hepatic Irs signaling. It's premature to conclude that insulin resistance doesn't affect lipid synthesis and lipoprotein turnover, in view of opposite findings indicating that hepatic insulin receptor ablation is associated with increased VLDL and ApoB levels (Biddinger et al., 2008). More probing tests (in the form of crosses onto atherosclerosis-prone backgrounds) will have to be conducted in the double Irs knockouts to reach firmer conclusions. But, taken at face value, the lipid data in the double Irs knockout lend themselves to the interpretation that excessive insulin signaling, rather than insulin resistance, is responsible for hepatic dyslipidemia in type 2 diabetes. Given the growing calls for early insulin treatment of type 2 diabetes and the inevitable hyperinsulinemia that goes with it, this problem is of great clinical and pharmacological relevance. Should we protect the liver against excessive insulinization? And is insulin treatment partly to blame for the failure of most glucose control regimens to significantly abate the prevalence of macro-vascular complications (UK Prospective Diabetes Study Group, 1998)? As we move into cardiovascular outcome-based models to test the effects of diabetes treatments, these questions acquire new urgency.

Tangled No Longer: The Path to Glucose Production

Dong observed that most of the gene expression changes in the Irs1/Irs2 double knockout could be reversed by also knocking out transcription factor Foxo1. These data complement and expand work in Drosophila and mice that had reached similar, albeit less sweeping conclusions (Gershman et al., 2007; Matsumoto et al., 2007). A growing consensus points to Foxo1 as the essential regulator of glucose production in response to insulin. This is not to say that there is nothing left to be discovered. Among the outstanding questions are the following: the role of Foxo1 in lipid metabolism, the nature of its regulation in type 2 diabetes, and its interaction with other components of the glucogenic machinery (such as Torc2) and with cAMP-dependent regulation of glycogenolysis/gluconeogenesis.

References

- Bergman RN, Ader M. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2000;11:351–356. doi: 10.1016/s1043-2760(00)00323-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biddinger SB, Hernandez-Ono A, Rask-Madsen C, Haas JT, Aleman JO, Suzuki R, Scapa EF, Agarwal C, Carey MC, Stephanopoulos G, et al. Cell Metab. 2008;7:125–134. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong XC, Copps KD, Guo S, Li Y, Kollipara R, DePinho RA, White MF. Cell Metab. 2008;8:65–76. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.06.006. this issue. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gershman B, Puig O, Hang L, Peitzsch RM, Tatar M, Garofalo RS. Physiol Genomics. 2007;29:24–34. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00061.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SH, Reaven GM. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:347–352. doi: 10.2337/dc07-1574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubota N, Kubota T, Itoh S, Kumagai H, Kozono H, Takamoto I, Mineyama T, Ogata H, Tokuyama K, Ohsugi M, et al. Cell Metab. 2008;8:49–64. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.05.007. this issue. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto M, Pocai A, Rossetti L, Depinho RA, Accili D. Cell Metab. 2007;6:208–216. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monnier L, Lapinski H, Colette C. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:881–885. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.3.881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nandi A, Kitamura Y, Kahn CR, Accili D. Physiol Rev. 2004;84:623–647. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00032.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Bethesda, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institute of Health; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- U.K. Prospective Diabetes Study Group. Lancet. 1998;352:837–853. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White MF. Science. 2003;302:1710–1711. doi: 10.1126/science.1092952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]